ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

[永平] 道元希玄 [Eihei] Dōgen Kigen

(1200-1253)

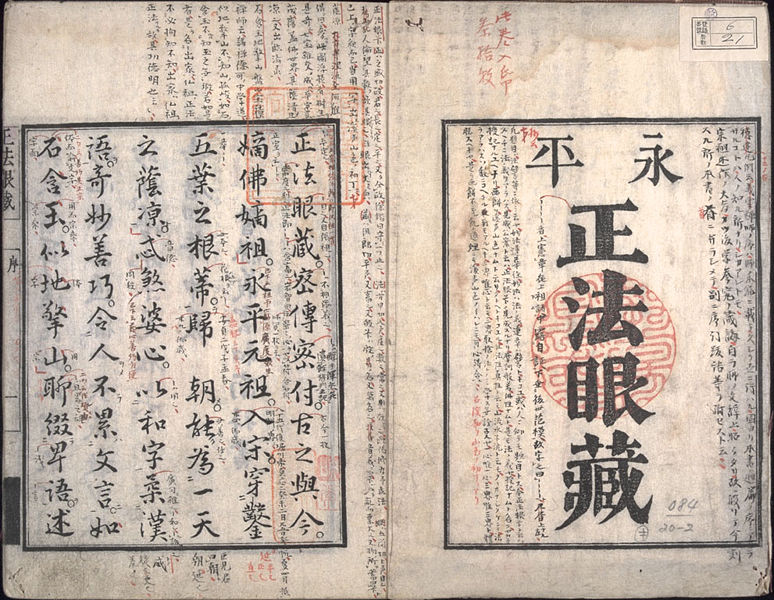

Title page of an 1811 edition of Dōgen's Shōbōgenzō

Tartalom |

Contents |

Végh József: PDF: Dógen Zen mester magyarul elérhető írásai Hrabovszky Dóra: Fukan-zazen-gi A zazen dicsérete Az ülő meditáció szabályai (Sóbógenzó zazengi) A zazen ösvénye A szívében a megvilágosodás szellemével élő lény (bódhiszattva) négy irányadó tevékenysége Életünk kérdése (Gendzsókóan 現成公案) PDF: Az Út Gyakorlásában Követendő pontok |

真字正法眼蔵 [Mana/Shinji] Shōbōgenzō 仮字正法眼蔵 [Kana/Kaji] Shōbōgenzō 普勧坐禅儀 Fukan zazengi 学道用心集 Gakudō-yōjinshū Advice on Studying the Way 永平清規 Eihei shingi Eihei Rules of Purity 永平廣錄 Eihei kōroku Dōgen's Extensive Record 宝慶記 Hōkyō-ki Memoirs of the Hōkyō Period 傘松道詠 Sanshō dōei Verses on the Way from Sanshō Peak

孤雲懷奘 Kōun Ejō (1198-1280) 修證義 Shushō-gi, compiled in 1890 Kōshō-ji PDF: The Life of Dōgen Zenji |

現成公案 Genjô kôan

> Translated by Robert Aitken and Kazuaki Tanahashi

> Translated by Kosen Nishiyama and John Stevens

> Translated by Thomas Cleary

> Lecture by Shohaku Okumura

> Translated by Reiho Masunaga

> Dōgen and the Five Ranks by Dale Verkuilen (PDF)

PDF: Dogen's Genjo Koan: Three Commentaries

Contains three separate translations and several commentaries by a wide variety of Zen masters. Nishiari Bokusan, Shohaku Okamura, Shunryu Suzuki, Kosho Uchiyama. Sojun Mel Weitsman, Kazuaki Tanahashi, and Dairyu Michael Wenger all have contributed to our presentation of this remarkable work.

Eight English Translations of Genjokoan:

http://www.gnusystems.ca/GenjoKoans.htm

Each translation has been divided into the same 12 parts; links to the corresponding parts of the other translations are found to the right of each section. A few obvious typos in the source texts have been silently corrected by the compiler (April 2006). See the original sources for introductions, notes and commentary. See also Shohaku Okumura's Realizing Genjokoan: The key to Dogen's Shobogenzo (Boston: Wisdom, 2010) – the best translation with commentary i have seen. —Gary Fuhrman, March 2011

tr. Robert Aitken and Kazuaki Tanahashi. Revised at San Francisco Zen Center, and later at Berkeley Zen Center; published (2000) in Tanahashi, Enlightenment Unfolds (Boston: Shambhala), 35-9. Earlier version in Tanahashi 1985 ( Moon in a Dewdrop ), 69-73, also Tanahashi and Schneider 1994 ( Essential Zen ).

As all things are buddha-dharma, there are delusion, realization, practice, birth and death, buddhas and sentient beings. As myriad things are without an abiding self, there is no delusion, no realization, no buddha, no sentient being, no birth and death. The buddha way, in essence, is leaping clear of abundance and lack; thus there are birth and death, delusion and realization, sentient beings and buddhas. Yet in attachment blossoms fall, and in aversion weeds spread. |

[1] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

To carry the self forward and illuminate myriad things is delusion. That myriad things come forth and illuminate the self is awakening. |

[2] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When you see forms or hear sounds, fully engaging body-and-mind, you intuit dharma intimately. Unlike things and their reflections in the mirror, and unlike the moon and its reflection in the water, when one side is illumined, the other side is dark. |

[3] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

To study the buddha way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be actualized by myriad things. When actualized by myriad things, your body and mind as well as the bodies and minds of others drop away. No trace of realization remains, and this no-trace continues endlessly. When you first seek dharma, you imagine you are far away from its environs. At the moment when dharma is correctly transmitted, you are immediately your original self. |

[4] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When you ride in a boat and watch the shore, you might assume that the shore is moving. But when you keep your eyes closely on the boat, you can see that the boat moves. Similarly, if you examine myriad things with a confused body and mind you might suppose that your mind and nature are permanent. When you practice intimately and return to where you are, it will be clear that nothing at all has unchanging self. |

[5] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Firewood becomes ash, and it does not become firewood again. Yet, do not suppose that the ash is after and the firewood before. You should understand that firewood abides in the phenomenal expression of firewood, which fully includes before and after and is independent of before and after. Ash abides in the phenomenal expression of ash, which fully includes before and after. Just as firewood does not become firewood again after it is ash, you do not return to birth after death. |

[6] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Enlightenment is like the moon reflected on the water. The moon does not get wet, nor is the water broken. Although its light is wide and great, the moon is reflected even in a puddle an inch wide. The whole moon and the entire sky are reflected in dewdrops on the grass, or even in one drop of water. |

[7] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When dharma does not fill your whole body and mind, you think it is already sufficient. When dharma fills your body and mind, you understand that something is missing. For example, when you sail out in a boat to the middle of an ocean where no land is in sight, and view the four directions, the ocean looks circular, and does not look any other way. But the ocean is neither round nor square; its features are infinite in variety. It is like a palace. It is like a jewel. It only looks circular as far as you can see at that time. All things are like this. |

[8] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

A fish swims in the ocean, and no matter how far it swims there is no end to the water. A bird flies in the sky, and no matter how far it flies there is no end to the air. However, the fish and the bird have never left their elements. When their activity is large their field is large. When their need is small their field is small. Thus, each of them totally covers its full range, and each of them totally experiences its realm. If the bird leaves the air it will die at once. If the fish leaves the water it will die at once. |

[9] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Now if a bird or a fish tries to reach the end of its element before moving in it, this bird or this fish will not find its way or its place. When you find your place where you are, practice occurs, actualizing the fundamental point. When you find your way at this moment, practice occurs, actualizing the fundamental point; for the place, the way, is neither large nor small, neither yours nor others'*. The place, the way, has not carried over from the past, and it is not merely arising now. |

[10] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Accordingly, in the practice-enlightenment of the buddha way, to attain one thing is to penetrate one thing; to meet one practice is to sustain one practice. |

[11] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Mayu, Zen master Baoche, was fanning himself. A monk approached and said, “Master, the nature of wind is permanent and there is no place it does not reach. Why, then, do you fan yourself?” |

[12] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

tr. Norman Waddell and Masao Abe (2002), in The Heart of Dōgen's Shōbōgenzō (Albany: SUNY Press), 39-45.

When all things are the Buddha Dharma, there is illusion and enlightenment, practice, birth, death, Buddhas, and sentient beings. When all things are without self, there is no illusion or enlightenment, no birth or death, no Buddhas or sentient beings. The Buddha Way is originally beyond any fullness and lack, and for that reason, there is birth and death, illusion and enlightenment, sentient beings and Buddhas. Yet for all that, flowers fall amid our regret and yearning, and hated weeds grow apace. |

[1] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Practice that confirms things by taking the self to them is illusion: for things to come forward and practice and confirm the self is enlightenment. Those who greatly enlighten illusion are Buddhas. Those greatly deluded amid enlightenment are sentient beings. Some people continue to realize enlightenment beyond enlightenment. Some proceed amid their illusion deeper into further illusion. |

[2] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Seeing forms and hearing sounds with body and mind as one, they make them intimately their own and fully know them. But it is not like a reflection in a mirror, it is not like the moon on the water. When they realize one side, the other side is in darkness. |

[3] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

To learn the Buddha Way is to learn one's self. To learn one's self is to forget one's self. To forget one's self is to be confirmed by all dharmas. To be confirmed by all dharmas is to cast off one's body and mind and the bodies and minds of others as well. All trace of enlightenment disappears, and this traceless enlightenment continues on without end. The moment you begin seeking the Dharma, you move far from its environs. The moment the Dharma is been [ sic ] rightly transmitted to you, you become the Person of your original part. |

[4] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When a man is in a boat at sea and looks back at the shoreline, it may seem to him as though the shore is moving. But when he fixes his gaze closely on the boat, he realizes it is the boat that is moving. In like manner, when a person tries to discern and affirm things with a confused notion of his body and mind, he makes the mistake of thinking his own mind, his own nature, is permanent and unchanging. If he turns back within himself, making all his daily deeds immediately and directly his own, the reason all things have no selfhood becomes clear to him. |

[5] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Once firewood turns to ash, the ash cannot revert to being firewood. But you should not take the view that it is ashes afterward and firewood before. You should realize that although firewood is at the dharma-stage of firewood, and that this is possessed of before and after, the firewood is at the same time independent, completely cut off from before, completely cut off from after. Ashes are in the dharma-stage of ashes, which also has a before and after. Just as firewood does not revert to wood once it has turned to ashes, human beings do not return to life after they have died. Buddhists do not speak of life becoming death. They speak of being “unborn.” Since it is a confirmed Buddhist teaching that death does not become life, Buddhists speak of being “undying.” Life is a stage of time, and death is a stage of time. It is like winter and spring. Buddhists do not suppose that winter passes into spring or speak of spring passing into summer. |

[6] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

The attainment of enlightenment is like the moon reflected on the water. The moon does not get wet, and the surface of the water is not broken. For all the breadth and vastness of its light, the moon comes to rest in a small patch of water. The whole moon and the sky in its entirety come to rest in a single dewdrop on a grass tip—a mere pinpoint of water. Enlightenment does not destroy man any more than the moon makes a hole on the surface of the water. Man does not obstruct enlightenment any more than the drop of dew obstructs the moon or the heavens. The depth of the one will be the measure of the other's height. As for the time—the quickness or slowness—of enlightenment's coming, you must carefully scrutinize the quantity of the water, survey the extent of the moon and the sky. |

[7] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When you have still not fully realized the Dharma in body and mind you think it sufficient. When the Dharma fills body and mind, you feel some lack. It is like boarding a boat and sailing into a broad and shoreless sea. You see nothing as you gaze about you but a wide circle of sea. Yet the great ocean is not circular. It is not square. It has other, inexhaustible virtues. It is like a glittering palace. It is like a necklace of precious jewels. Yet it appears for the moment to the range of your eyes simply as an encircling sea. It is the same with all things. The dusty world and the Buddha Way beyond may assume many different aspects, but we can see and understand them only to the extent that our eye is cultivated through practice. If we are to grasp the true and particular natures of all things, we must know that in addition to apparent circularity or angularity, there are inexhaustibly great virtues in the mountains and seas. We must realize that this inexhaustible store is present not only all around us, it is present right beneath out feet and within a single drop of water. |

[8] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Fish swim the water and however much they swim, there is no end to the water. Birds fly the skies, and however much they fly, there is no end to the skies. Yet fish never once leave the water, birds never forsake the sky. When their need is great, there is great activity. When their need is small, there is small activity. In this way, none ever fails to exert itself to the full, and nowhere does any fail to move and turn freely. If a bird leaves the sky, it will soon die. If a fish leaves the water, it at once perishes. We should grasp that water means life [for the fish], and the sky means life [for the bird]. It must be that the bird means life [for the sky], and the fish means life [for the water]; that life is the bird, life is the fish. We could continue in this way even further, because practice and realization [ sic ], and for all that is possessed of life, it is the same. |

[9] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Even were there a bird or fish that desired to proceed further on after coming to the end of the sky or the water, it could make no way, could find no place, in either element. When that place is attained, when that way is achieved, all of one's everyday activities are immediately manifesting reality. Inasmuch as this way, this place, is neither large nor small, self nor other, does not exist from before, does not come into being now for the first time, it is just as it is. |

[10] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Because it is as it is, if a person practices and realizes the Buddha Way, when he attains one dharma he penetrates completely that one dharma; when he encounters one practice, he practices that one practice. Since here is where the place exists, and since the Way opens out in all directions, the reason we are unable to know its total knowable limits is simply because our knowing lives together and practices together with the full penetration of the Buddha Dharma. |

[11] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

As Zen master Pao-ch'e of Mount Ma-yü was fanning himself, a monk came up and said, “The nature of the wind is constancy. There is no place it does not reach. Why use a fan?” Pao-ch'e answered, “You only know the nature of the wind is constancy. You haven't yet grasped the meaning of its reaching every place.” “What is the meaning of its reaching every place?” asked the monk. The master only fanned himself. The monk bowed deeply. |

[12] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

tr. Paul Jaffe (1996), in Yasutani, Flowers Fall (Boston: Shambhala), 101-107.

When all dharmas are buddha-dharma, there are delusion and enlightenment, practice, birth, death, buddhas, and sentient beings. When the myriad dharmas are all without self, there is no delusion, no realization, no buddhas, no sentient beings, no birth, and no death. Since originally the buddha way goes beyond abundance and scarcity, there are birth and death, delusion and realization, sentient beings and buddhas. |

[1] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Carrying the self forward to confirm [the existence of] the myriad dharmas is delusion. The myriad dharmas advancing and confirming [the existence of] the self is realization. |

[2] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

In mustering the whole body and mind and seeing forms, in mustering the whole body and mind and hearing sounds, they are intimately perceived; but it is not like the reflection in a mirror, nor like the moon in the water. When one side is realized the other side is dark. |

[3] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

To study the Buddha way is to study oneself. To study oneself is to forget oneself. To forget oneself is to be enlightened by the myriad dharmas. To be enlightened by the myriad dharmas is to bring about the dropping away of body and mind of both oneself and others. The traces of enlightenment come to an end, and this traceless enlightenment is continued endlessly. When a person starts to search out the dharma, he separates himself far from the dharma. When the dharma has already been rightly transmitted in oneself, just then one is one's original self. |

[4] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

If a person, when he is riding along in a boat, looks around and sees the shore, he mistakenly thinks that the bank is moving. But if he looks directly at the boat, he discovers that it is the boat that is moving along. Likewise, with confused thoughts about body and mind, holding to discrimination of the myriad dharmas, one mistakenly thinks his own mind and nature are permanent. If, intimately engaged in daily activities, one returns to right here, the principle that the myriad dharmas have no self is clear. |

[5] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Firewood becomes ash. It does not turn into firewood again. But we should not hold to the view that the ash is after and the firewood is before. Know that firewood abides in its dharma position as firewood and has its past and future. Though it has its past and future, it cuts off past and future. Ash is in its dharma position as ash and has its past and future. Just as this firewood, after it has become ash, does not turn into firewood again, so a person, after death, does not take rebirth. Therefore, we do not say that life becomes death. This is the established way of the Buddha-dharma. For this reason it is called unborn. Death does not become life. This is the established buddha-turning of the dharma wheel. For this reason it is called undying. Life is its own time. Death is its own time. For example, it is like winter and spring. We don't think that winter becomes spring. We don't say that spring becomes summer. |

[6] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

A person getting enlightened is like the moon reflecting in the water. The moon does not get wet, the water is not disturbed. Though it is a great expanse of light, it reflects in a little bit of water; the whole moon and the whole sky reflect even in the dew on the grass; they reflect even in a single drop of water. Enlightenment not disturbing the person is like the moon not piercing the water. A person not obstructing enlightenment is like the dewdrop not obstructing the heavens. The depth is the measure of the height. As for the length or brevity of the time [of the reflection], one ought to examine whether the water is large or small and discern whether the sky and moon are wide or narrow. |

[7] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

If the dharma has not yet fully come into one's body and mind, one thinks it is already sufficient. On the other hand, if the dharma fills one's body and mind, there is a sense of insufficiency. It is like going out in a boat in the middle of an ocean with no mountains. Looking in the four directions one only sees a circle; no distinguishing forms are seen. Nevertheless, this great ocean is neither a circle nor has directions. The wondrous features of this ocean that remain beyond our vision are inexhaustible. It is like a palace; it is like a jeweled necklace. It is just that, as far as my vision reaches for the time being, it appears to be a circle. The myriad dharmas are also just like that. Though they include all forms within and beyond the dusty world, clear seeing and understanding only reach as far as the power of our penetrating insight. |

[8] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When fish swim in the water, no matter how much they swim the water does not come to an end. When birds fly in the sky, no matter how much they fly, the sky does not come to an end. However, though fish and birds have never been apart from the water and the air, when the need is great the function is great; when the need is small the function is small. Likewise, it is not that at every moment they are not acting fully, not that they do not turn and move freely everywhere, but if a bird leaves the air, immediately it dies; if a fish leaves the water, immediately it dies. We should realize that because of water there is life. We should realize that because of air there is life. Because there are birds there is life; because there are fish there is life. Life is the bird and life is the fish. Besides this we could proceed further. It is just the same with practice and enlightenment and the lives of people. |

[9] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

So, if there were a bird or fish that wanted to go through the sky or the water only after thoroughly investigating its limits, he would not attain his way nor find his place in the water or in the sky. If one attains this place, these daily activities manifest absolute reality. If one attains this Way, these daily activities are manifest absolute reality. This Way, this place, is neither large nor small, neither self nor other, has neither existed previously nor is just now manifesting, and thus it is just as it is. |

[10] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Therefore, for a person who practices and realizes the Buddha way, to attain one dharma is to penetrate one dharma; to encounter one activity is to practice one activity. |

[11] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

As Zen master Pao-ch'e of Mount Ma-ku was fanning himself, a monk came and said, “The nature of wind is permanently abiding and there is no place it does not reach. Why, master, do you still use a fan?” The master said, “You only know that the nature of wind is permanently abiding, but you do not yet know the true meaning of ‘there is no place it does not reach.'” The monk said, “What is the true meaning of ‘there is no place it does not reach'?” The master just fanned himself. The monk bowed deeply. |

[12] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

tr. Gudo Wafu Nishijima, from “Understanding the Shobogenzo ”, © Windbell Publications 1992 ( www.thezensite.com )

When all things and phenomena exist as Buddhist teachings, then there are delusion and realization, practice and experience, life and death, buddhas and ordinary people. When millions of things and phenomena are all separate from ourselves, there are no delusion and no enlightenment, no buddhas and no ordinary people, no life and no death. Buddhism is originally transcendent over abundance and scarcity, and so [in reality] there is life and death, there is delusion and realization, there are people and buddhas. |

[1] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Driving ourselves to practice and experience millions of things and phenomena is delusion. When millions of things and phenomena actively practice and experience ourselves, that is realization. Those who totally realize delusion are buddhas. Those who are totally deluded about realization are ordinary people. There are people who attain further realization on the basis of realization. There are people who increase their delusion in the midst of delusion. When buddhas are really buddhas, they do not need to recognize themselves as buddhas. Nevertheless, they experience the state of buddha, and they go on experiencing the state of buddha. |

[2] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Even if we use our whole body and mind to look at forms, and even if we use our whole body and mind to listen to sounds, perceiving them directly, [our human perception] can never be like the reflection of an image in a mirror, or like the water and the moon. When we affirm one side, we are blind to the other side. |

[3] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

To learn Buddhism is to learn ourselves. To learn ourselves is to forget ourselves. To forget ourselves is to be experienced by millions of things and phenomena. To be experienced by millions of things and phenomena is to let our own body and mind, and the body and mind of the external world, fall away. [Then] we can forget the [mental] trace of realization, and show the [real] signs of forgotten realization continually, moment by moment. When a person first seeks the Dharma, he is far removed from the borders of Dharma. But as soon as the Dharma is authentically transmitted to the person himself, he is a human being in his own true place. |

[4] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When a man is sailing along in a boat and he moves his eyes to the shore, he misapprehends that the shore is moving. But if he keeps his eyes on the boat, he can recognize that it is the boat that is moving forward. [Similarly,] when we observe millions of things and phenomena with a disturbed body and mind, we mistakenly think that our own mind or our own spirit may be permanent. But if we familiarize ourselves with our actual conduct and come back to this concrete place, it becomes clear that the millions of things and phenomena are different from ourselves. |

[5] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Firewood becomes ash; it can never go back to being firewood. Nevertheless, we should not take the view that ash is its future and firewood is its past. We should recognize that firewood occupies its place in the Universe as firewood, and it has its past moment and its future moment. And although we can say that it has its past and its future, the past moment and the future moment are cut off. Ash exists in its place in the Universe as ash, and it has its past moment and its future moment. Just as firewood can never again be firewood after becoming ash, human beings cannot live again after their death. So it is a rule in Buddhism not to say that life turns into death. This is why we speak of “no appearance.” And it is Buddhist teaching as established in the preaching of Gautama Buddha that death does not turn into life. This is why we speak of “no disappearance.” Life is an instantaneous situation, and death is also an instantaneous situation. It is the same, for example, with winter and spring. We do not think that winter becomes spring, and we do not say that spring becomes summer. |

[6] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

A person getting realization is like the moon reflected in water: the moon does not get wet, and the water is not broken. Though the light [of the moon] is wide and great, it can be reflected in a foot or an inch of water. The whole moon and the whole sky can be reflected in a dew-drop on a blade of grass or in a single drop of rain. Realization does not reshape a man, just as the moon does not pierce the water. A man does not hinder realization, just as a dew-drop does not hinder the sky and moon. The depth [of realization] may be the same as the concrete height [of the moon]. [To understand] its duration, we should examine large and small bodies of water, and notice the different widths of the sky and moon [when reflected in water]. |

[7] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When the Dharma has not completely filled our body and mind, we feel that the Dharma is abundantly present in us. When the Dharma fills our body and mind, we feel as if something is missing. For example, sailing out into the ocean, beyond sight of the mountains, when we look around in the four directions, [the ocean] appears only to be round; it does not appear to have any other form at all. Nevertheless, the great ocean is not round and it is not square, and there are so many other characteristics of the ocean that they could never be counted. [To fishes] it is like a palace and [to gods in heaven] it is like a necklace of pearls. But as far as our human eyes can see, it only appears to be round. The same applies to everything in the world. The secular world and the Buddhist world include a great many situations, but we can view them and understand them only as far as our eyes of Buddhist study allow. So if we want to know the way things naturally are, we should remember that the oceans and mountains have innumerably many characteristics besides the appearance of squareness or roundness, and we should remember that there are [other] worlds in [all] four directions. This applies not only to the periphery; we should remember that the same applies to this place here and now, and to a single drop of water. |

[8] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When fish swim in water, though they keep swimming, there is no end to the water. When birds fly in the sky, though they keep flying, there is no end to the sky. At the same time, fish and birds have never left the water or the sky. The more [water or sky] they use, the more useful it is; the less [water or sky] they need, the less useful it is. Acting like this, each one realizes its limitations at every moment and each one somersaults [in complete freedom] at every place; but if a bird leaves the sky it will die at once, and if a fish leaves the water it will die at once. So we can conclude that water is life and the sky is life; at the same time, birds are life, and fish are life; it may be that life is birds and life is fish. There may be other expressions that go even further. The existence of practice and experience, the existence of their age itself and life itself can also be [explained] like this. |

[9] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

However, a bird or fish that tried to understand the water or the sky completely, before swimming or flying, could never find its way or find its place in the water or the sky. But when we find this place here and now, it naturally follows that our actual behavior realizes the Universe. And when we find a concrete way here and now, it naturally follows that our actual behavior realizes the Universe. This way and this place exist as reality because they are not great or small, because they are not related to ourselves or to the external world, and because they do not exist already and they do appear in the present. |

[10] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Similarly, if someone is practicing and experiencing Buddhism, when he receives one teaching, he just realizes that one teaching, and when he meets one [opportunity to] act, he just performs that one action. This is the state in which the place exists and the way is realized, and this is why we cannot clearly recognize where [the place and the way] are—because such recognition and the perfect realization of Buddhism appear together and are experienced together. Do not think that what you have attained will inevitably enter your own consciousness and be recognized by your intellect. The experience of the ultimate state is realized at once, but a mystical something does not always manifest itself. Realization is not always definite. |

[11] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Master Ho-tetsu of Mt. Mayoku was using a fan. At that time, a monk came in and asked him, “[It is said that] the nature of air is to be ever-present, and there is no place that air cannot reach. Why then does the Master use a fan?” |

[12] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

tr. Francis H. Cook (1989), in Sounds of Valley Streams (Albany: SUNY Press), 65-9.

When all things are just what they are [apart from discrimination], delusion and enlightenment exist, religious practice exists, birth exists, death exists, Buddhas exist, and ordinary beings exist. When the myriad things are without self, there is no delusion, no enlightenment, no Buddhas, no ordinary beings, no birth, no extinction. Since the Buddha Way from the beginning transcends fullness and deficiency, there is birth and extinction, delusion and enlightenment, beings and Buddhas. However, though this is the way it is, it is only this: flowers scatter in our longing, and weeds spring up in our loathing. |

[1] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Conveying the self to the myriad things to authenticate them is delusion; the myriad things advancing to authenticate the self is enlightenment. It is Buddhas who greatly enlighten delusion; it is ordinary beings who are greatly deluded within enlightenment. Moreover, there are those who are enlightened within enlightenment and those who are deluded within delusion. When Buddhas are truly Buddhas, there is no need for the self to understand that it is Buddha. Yet we are Buddhas and we come to authenticate this Buddha. |

[2] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Mustering the [whole] mind-body and seeing forms, mustering the [whole] mind-body and hearing forms, we understand them intimately, but it is not like shapes being reflected in a mirror or like the moon being reflected in water. When one side is enlightened, the other side is dark. |

[3] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

To study the Buddha Way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be authenticated by the myriad things. To be authenticated by the myriad things is to drop off the mind-body of oneself and others. There is [also] remaining content with the traces of enlightenment, and one must eternally emerge from this resting. When persons first turn to the Dharma, they separate themselves from its boundary. [But] when the Dharma is already internally transmitted, one is immediately the Original Man. |

[4] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

A person rides in a boat, looks at the shore, and mistakenly thinks that the shore is moving. If one looks carefully at the boat, one sees that it is the boat that is moving. In like manner, if a person is confused about the mind-body and discriminates the myriad things, there is the error of thinking that one's own mind or self is eternal. If one becomes intimate with practice and returns within [to the true self], the principle of the absence of self in all things is made clear. |

[5] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Firewood becomes ashes and cannot become firewood again. However, you should not think of ashes as the subsequent and firewood as the prior [of the same thing]. You should understand that firewood abides in its own state as firewood, and has [its own] prior and subsequent. Although it has [its own] prior and subsequent, it is cut off from prior and subsequent. Ashes are in their own state as ashes and have a prior and subsequent. Just as firewood does not become firewood again after turning to ash, so a person does not return to life again after death. Thus, it is the fixed teaching of the Buddha Dharma that life does not become death, and therefore we call it “nonlife.” It is the fixed sermon of the Buddha that death does not become life, and therefore we call it “nondeath.” Life is situated in one time and death is situated in one time. For instance, it is like winter and spring. We do not think that winter becomes spring or that spring becomes summer. |

[6] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

A person's becoming enlightened is like the reflection of the moon in water. The moon does not get wet nor is the water ruffled. Though the moonlight is vast and far-reaching, it is reflected in a few drops of water. The entire moon and heavens are reflected in even a drop of dew on the grass, or in a drop of water. Our not being obstructed by enlightenment is like the water's not being obstructed by the moon. Our not obstructing enlightenment is like the nonobstruction of the moonlight by a dewdrop. The depth [of the water] is equal to the height [of the moon]. As for the length or brevity [of the reflection], you should investigate the water's vastness or smallness and the brightness or dimness of the moon. |

[7] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When the Dharma does not yet completely fill the mind-body, we think that it is already sufficient. When the Dharma fills us, on the other hand, we think that it is not enough. For instance, when we are riding in a boat out of sight of land and we look around, we see only a circle [of ocean], and no other characteristics are visible. However, the great ocean is neither circular nor square, and its other characteristics are inexhaustible. It looks like a palace [to fish] or a jewel ornament [to beings in the sky]. It just looks round to our eyes when we briefly encounter it. The myriad things are the same. Although things in this world or beyond this world contain many aspects, we are capable of grasping only what we can through the power of vision, which comes from practice. In order to perceive these may aspects, you must understand that besides being round or square, oceans and rivers have many other characteristics and that there are many worlds in other directions. It is not like this just nearby; it is like this right beneath your feet and even in a drop of water. |

[8] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When a fish swims in water, there is no end of the water no matter how far it swims. When a bird flies in the sky, fly though it may, there is no end to the sky. However, no fish or bird has ever left water or sky since the beginning. It is just that when there is a great need, the use is great, and when there is a small need, the use is small. In this way, no creature ever fails to realize its own completeness; wherever it is, it functions freely. But if a bird leaves the sky, it will immediately die, and if a fish leaves the water, it will immediately die. You must understand that the water is life and the air is life. The bird is life and the fish is life. Life is the fish and life is the bird. Besides these [ideas], you can probably think of others. There are such matters as practice-authentication and long and short lives. |

[9] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

However, if a bird or fish tries to proceed farther after reaching the limit of air or water, it cannot find a path or a place. If you find this place, then following this daily life is itself the manifesting absolute reality. The path and the place are neither large nor small. They are neither self nor other, and they neither exist from the beginning nor originate right now. Therefore, they are just what they are. |

[10] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Being just what they are, if one practice-authenticates the Buddha Way, then when one understands one thing, one penetrates one thing; when one takes up one practice, one cultivates one practice. Because the place is right here and the path is thoroughly grasped, the reason you do not know the entirety of what is to be known is that this knowing and the total penetration of the Buddha Dharma arise together and practice together. Do not think that when you have found this place that it will become personal knowledge or that it can be known conceptually. Even though the authenticating penetration manifests immediately, that which exists most intimately does not necessarily manifest. Why should it become evident? |

[11] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Priest Pao-ch'e of Mt. Ma-ku was fanning himself. A monk came by and asked, “The wind's nature is eternal and omnipresent. Why, reverend sir, are you still fanning yourself?” The master replied, “You only know that the wind's nature is eternal, but you do not know the reason why it exists everywhere.” The monk asked, “Why does it exist everywhere?” The master just fanned himself. The monk made a bow of respect. |

[12] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

tr. Thomas Cleary (1986), published 2005 in Classics of Buddhism and Zen V.2 (Boston: Shambhala), 275-80.

When all things are Buddha-teachings, then there is delusion and enlightenment, there is cultivation of practice, there is birth, there is death, there are Buddhas, there are sentient beings. When myriad things are all not self, there is no delusion, no enlightenment, no Buddhas, no sentient beings, no birth, no death. Because the Buddha Way originally sprang forth from abundance and paucity, there is birth and death, delusion and enlightenment, sentient beings and Buddhas. Moreover, though this is so, flowers fall when we cling to them, and weeds only grow when we dislike them. |

[1] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Acting on and witnessing myriad things with the burden of oneself is “delusion.” Acting on and witnessing oneself in the advent of myriad things is enlightenment. Great enlightenment about delusion is Buddhas; great delusion about enlightenment is sentient beings. There are also those who attain enlightenment on top of enlightenment, and there are those who are further deluded in the midst of delusion. When the Buddhas are indeed the Buddhas, there is no need to be self-conscious of being Buddhas; nevertheless it is realizing buddhahood—Buddhas go on realizing. |

[2] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

In seeing forms with the whole body-mind, hearing sound with the whole body-mind, though one intimately understands, it isn't like reflecting images in a mirror, it's not like water and the moon—when you witness one side, one side is obscure. |

[3] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Studying the Buddha Way is studying oneself. Studying oneself is forgetting oneself. Forgetting oneself is being enlightened by all things. Being enlightened by all things is causing the body-mind of oneself and the body-mind of others to be shed. There is ceasing the traces of enlightenment, which causes one to forever leave the traces of enlightenment which is cessation. When people first seek the Teaching, they are far from the bounds of the Teaching. Once the Teaching is properly conveyed in oneself, already one is the original human being. |

[4] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When someone rides in a boat, as he looks at the shore he has the illusion that the shore is moving. When he looks at the boat under him, he realizes the boat is moving. In the same way, when one takes things for granted with confused ideas of body-mind, one has the illusion that one's own mind and own nature are permanent; but if one pays close attention to one's own actions, the truth that things are not self will be clear. |

[5] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Kindling becomes ash, and cannot become kindling again. However, we should not see the ash as after and the kindling as before. Know that kindling abides in the normative state of kindling, and though it has a before and after, the realms of before and after are disconnected. Ash, in the normative state of ash, has before and after. Just as that kindling, after having become ash, does not again become kindling, so after dying a person does not become alive again. This being the case, not saying that life becomes death is an established custom in Buddhism—therefore it is called unborn. That death does not become life is an established teaching of the Buddha; therefore we say imperishable. Life is an individual temporal state, death is an individual temporal state. It is like winter and spring—we don't think winter becomes spring, we don't say spring becomes summer. |

[6] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

People's attaining enlightenment is like the moon reflected in water. The moon does not get wet, the water isn't broken. Though it is a vast expansive light, it rests in a little bit of water—even the whole moon, the whole sky, rests in a dewdrop on the grass, rests in even a single droplet of water. That enlightenment does not shatter people is like the moon not piercing the water. People's not obstructing enlightenment is like the drop of dew not obstructing the moon in the sky. The depth is proportionate to the height. As for the length and brevity of time, examining the great and small bodies of water, you should discern the breadth and narrowness of the moon in the sky. |

[7] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Before one has studied the Teaching fully in body and mind, one feels one is already sufficient in the Teaching. If the body and mind are replete with the Teaching, in one respect one senses insufficiency. For example, when one rides a boat out onto the ocean where there are no mountains and looks around, it only appears round, and one can see no other, different characteristics. However, this ocean is not round, nor is it square—the remaining qualities of the ocean are inexhaustible. It is like a palace, it is like ornaments, yet as far as our eyes can see, it only seems round. It is the same with all things—in the realms of matter, beyond conceptualization, they include many aspects, but we see and comprehend only what the power of our eye of contemplative study reaches. If we inquire into the “family ways” of myriad things, the qualities of seas and mountains, beyond seeming square or round, are endlessly numerous. We should realize there exist worlds everywhere. It's not only thus in out of the way places—know that even a single drop right before us is also thus. |

[8] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

As a fish travels through water, there is no bound to the water no matter how far it goes; as a bird flies through the sky, there's no bound to the sky no matter how far it flies. While this is so, the fish and birds have never been apart from the water and the sky—it's just that when the need is large the use is large, and when the requirement is small the use is small. In this way, though the bounds are unfailingly reached everywhere and tread upon in every single place, the bird would instantly die if it left the sky and the fish would instantly die if it left the water. Obviously, water is life; obviously the sky is life. There is bird being life. There is fish being life. There is life being bird, there is life being fish. There must be progress beyond this—there is cultivation and realization, the existence of the living one being like this. |

[9] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Under these circumstances, if there were birds or fish who attempted to traverse the waters or the sky after having found the limits of the water or sky, they wouldn't find a path in the water or the sky—they won't find any place. When one finds this place, this action accordingly manifests as the issue at hand; when one finds this path, this action accordingly manifests as the issue at hand. This path, this place, is not big or small, not self or other, not preexistent, not now appearing—therefore it exists in this way. |

[10] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

In this way, if someone cultivates and realizes the Buddha Way, it is attaining a principle, mastering the principle; it is encountering a practice, cultivating the practice. In this there is a place where the path has been accomplished, hence the unknowability of the known boundary is born together and studies along with the thorough investigation of the Buddha Teaching of this knowing—therefore it is thus. Don't get the idea that the attainment necessarily becomes one's own knowledge and view, that it would be known by discursive knowledge. Though realizational comprehension already takes place, implicit being is not necessarily obvious—why necessarily is there obvious becoming? |

[11] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Zen Master Hotetsu of Mt. Mayoku was using a fan. A monk asked him about this: “The nature of wind is eternal and all-pervasive—why then do you use a fan?” The master said, “You only know the nature of wind is eternal, but do not yet know the principle of its omnipresence.” The monk asked, “What is the principle of its omnipresence?” The master just fanned. The monk bowed. |

[12] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

tr. Kosen Nishiyama and John Stevens (1975) ( www.thezensite.com )

When all things are the Buddha-dharma, there is enlightenment, illusion, practice, life, death, Buddhas, and sentient beings. When all things are seen not to have any substance, there is no illusion or enlightenment, no Buddhas or sentient beings, no birth, or destruction. Originally the Buddhist Way transcends itself and any idea of abundance or lack—still there is birth and destruction, illusion and enlightenment, sentient beings and Buddhas. Yet people hate to see flowers fall and do not like weeds to grow. |

[1] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

It is an illusion to try to carry out our practice and enlightenment through ourselves, but to have practice and enlightenment through phenomena, that is enlightenment. To have great enlightenment about illusion is to be a Buddha. To have great illusion about enlightenment is to be a sentient being. Further, some are continually enlightened beyond enlightenment but some add more and more illusion. |

[2] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Through body and mind we can comprehend the form and sound of things. They work together as one. However, it is not like the reflection of shadow in a mirror, or the moon reflected in the water. If you look at only one side, the other is dark. |

[3] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

To learn the Buddhist way is to learn about oneself. To learn about oneself is to forget oneself. To forget oneself is to perceive oneself as all things. To realize this is to cast off the body and mind of self and others. When you have reached this stage you will be detached even from enlightenment but will practice it continually without thinking about it. When people seek the Dharma [outside themselves] they are immediately far removed from its true location. When the Dharma has been received through the right transmission, one's real self immediately appears. |

[4] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

If you are in a boat, and you only look at the riverbank, you will think that the riverbank is moving; but if you look at the boat, you will discover that the boat itself is actually moving. Similarly, if you try to understand the nature of phenomena only through your own confused perception you will mistakenly think that your nature is eternal. Furthermore, if you have the right practice and return to your origin then you will see that all things have no permanent self. |

[5] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Once firewood is reduced to ashes, it cannot return to firewood; but we should not think of ashes as the potential state of firewood or vice-versa. Ash is completely ash and firewood is firewood. They have their own past, future, and independent existence. |

[6] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When human beings attain enlightenment, it is like the moon reflected in the water. The moon appears in the water but does not get wet nor is the water disturbed by the moon. Furthermore the light of the moon covers the earth and yet it can be contained in small pool of water, a tiny dewdrop, or even one minuscule drop of water. |

[7] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When the True Law is not totally attained, both physically and mentally, there is a tendency to think that we posses the complete Law and our work is finished. If the Dharma is completely present, there is a realization of one's insufficiencies. |

[8] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Fish in the ocean find the water endless and birds think the sky is without limits. However, neither fish nor birds have been separated from their element. When their need is great, their utilization is great, when their need is small, the utilization is small. They fully utilize every aspect to its utmost—freely, limitlessly. However, we should know that if birds are separated from their own element they will die. We should know that water is life for fish and the sky is life for birds. In the sky, birds are life; and in the water, fish are life. Many more conclusions can be drawn like this. There is practice and enlightenment [like the above relationships of sky and birds, fish and water]. |

[9] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

However, after the clarification of water and sky, we can see that if there are birds or fish that try to enter the sky or water, they cannot find either a way or a place. If we understand this point, there is actualization of enlightenment in our daily life. If we attain this Way, all our actions are the actualization of enlightenment. This Way, this place, is not great or small, self or others, neither past or present—it exists just as it is. |

[10] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Like this, if we practice and realize the Buddhist way we can master and penetrate each dharma; and we can confront and master any one practice. There is a place where we can penetrate the Way and find the extent of knowable perceptions. This happens because our knowledge co-exists simultaneously with the ultimate fulfillment of the Buddhist Dharma. |

[11] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

One day, when Zen Master Hotestsu of Mt. Mayoku was fanning himself, a monk approached and asked, “The nature of wind never changes and blows everywhere, so why are you using a fan?” |

[12] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

tr. Reiho Masunaga ( www.thezensite.com )

When all things are Buddhism, delusion and enlightenment exist, training exists, life and death exist, Buddhas exist, all-beings exist. When all things belong to the not-self, there are no* delusion, no enlightenment, no all beings, no birth and decay. Because the Buddha's way transcends the relative and absolute, birth and decay exist, * delusion and enlightenment exist, all-beings and Buddhas exist. And despite this, flowers fall while we treasure their bloom; weeds flourish while we wish them dead. * [Note: in the source file, this no is placed before delusion in the third sentence rather than the second.] |

[1] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

To train and enlighten all things from the self is delusion; to train and enlighten the self from all things is enlightenment. Those who enlighten their delusion are Buddhas; those deluded in enlightenment are all-beings. Again there are those who are enlightened on enlightenment and those deluded within delusion. When Buddhas are really Buddhas, we need not know our identity with the Buddhas. But we are enlightened Buddhas and express the Buddha in daily life. |

[2] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When we see objects and hear voices with all our body and mind—and grasp them intimately—it is not a phenomenon like a mirror reflecting form or like a moon reflected on water. When we understand one side, the other side remains in darkness. |

[3] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

To study Buddhism is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be enlightened by all things. To be enlightened by all things is to be free from attachment to the body and mind of one's self and of others. It means wiping out even attachment to Satori. Wiping out attachment to Satori, we must enter actual society. When man first recognizes the true law, he unequivocally frees himself from the border of truth. He who awakens the true law in himself immediately becomes the original man. |

[4] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

If in riding a boat you look toward the shore, you erroneously think that the shore is moving. But upon looking carefully at the ship, you see that it is the ship that is actually moving. Similarly, seeing all things through a misconception of your body and mind gives rise to the mistake that this mind and substance are eternal. If you live truly and return to the source, it is clear that all things have no substance. |

[5] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Burning logs become ashes—and cannot return again to logs. Therefore you should not view ashes as after and logs as before. You must understand that a burning log—as a burning log—has before and after. But although it has past and future, it is cut off from past and future. Ashes as ashes have after and before. Just as ashes do not become logs again after becoming ashes, man does not live again after death. So not to say that life becomes death is a natural standpoint of Buddhism. So this is called no-life. |

[6] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When a man gains enlightenment, it is like the moon reflecting on water: the moon does not become wet, nor is the water ruffled. Even though the moon gives immense and far-reaching light, it is reflected in a puddle of water. The full moon and the entire sky are reflected in a dewdrop on the grass. Just as enlightenment does not hinder man, the moon does not hinder the water. |

[7] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When the true law is not fully absorbed by our body and mind, we think that it is sufficient. But if the right law is fully enfolded by our body and mind, we feel that something is missing. For example, when you take a boat to sea, where mountains are out of sight, and look around, you see only roundness; you cannot see anything else. But this great ocean is neither round nor square. Its other characteristics are countless. Some see it as a palace, other as an ornament. We only see it as round for the time being—within the field of our vision: this is the way we see all things. Though various things are contained in this world of enlightenment, we can see and understand only as far as the vision of a Zen trainee. To know the essence of all things, you should realize that in addition to appearance as a square or circle, there are many other characteristics of ocean and mountain and that there are many worlds. It is not a matter of environment: you must understand that a drop contains the ocean and that the right law is directly beneath your feet. |

[8] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

When fish go through water, there is no end to the water no matter how far they go. When birds fly in the sky, there is no end to the sky no matter how far they fly. But neither fish nor birds have been separated from the water or sky—from the very beginning. It is only this: when a great need arises, a great use arises; when there is little need, there is little use. Therefore, they realize full function in each thing and free ability according to each place. |

[9] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

But if after going through water, fish try to go farther, or if after going through the sky, birds try to go farther—they cannot find a way or a resting place in water or sky. |

[10] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Because the way and place are like this, if, in practicing Buddhism, you pick up one thing, you penetrate one thing; if you complete one practice, you penetrate one practice. When deeply expressing this place and way, we do not realize it clearly because this activity is simultaneous with and interfused with the study of Buddhism. |

[11] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

Zen master Pao-ch'ih was fanning himself one summer day when a passing priest asked: “The nature of wind is stationary, and it is universally present. Why do you then use your fan, sir?” The Zen master replied: “Though you know the nature of wind is stationary, you do not know why it is universally present.” The priest asked, “Why then is the wind universally present?” The master only fanned himself, and the priest saluted him. Enlightenment through true experience and the vital way of right transmission are like this. Those who deny the need for fanning because the nature of wind is stationary and because the wind is sensed without the use of a fan understand neither the eternal presence of the wind nor its nature. Because the nature of wind is eternally present, the wind of Buddhism turns the earth to gold and ripens the rivers to ghee. |

[12] TA / WA / Jaffe / Nishijima / Cook / Cleary / NS / Masunaga |

1a. GENJO KOAN

Actualizing the Fundamental Point

by Eihei Dogen

Translated by Robert Aitken and Kazuaki Tanahashi

Revised at San Francisco Zen Center

As all things are buddha-dharma, there is delusion and realization, practice, and birth and death, and there are buddhas and sentient beings.

As the myriad things are without an abiding self, there is no delusion, no realization, no buddha, no sentient being, no birth and death.

The buddha way is, basically, leaping clear of the many of the one; thus there are birth and death, delusion and realization, sentient beings and buddhas.

Yet in attachment blossoms fall, and in aversion weeds spread.

To carry yourself forward and experience myriad things is delusion. That myriad things come forth and experience themselves is awakening.

Those who have great realization of delusion are buddhas; those who are greatly deluded about realization are sentient beings. Further, there are those who continue realizing beyond realization, who are in delusion throughout delusion.

When buddhas are truly buddhas they do not necessarily notice that they are buddhas. However, they are actualized buddhas, who go on actualizing buddhas.

When you see forms or hear sounds fully engaging body-and-mind, you grasp things directly. Unlike things and their reflections in the mirror, and unlike the moon and its reflection in the water, when one side is illumined the other side is dark.

To study the buddha way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be actualized by myriad things. When actualized by myriad things, your body and mind as well as the bodies and minds of others drop away. No trace of realization remains, and this no-trace continues endlessly.

When you first seek dharma, you imagine you are far away from its environs. But dharma is already correctly transmitted; you are immediately your original self. When you ride in a boat and watch the shore, you might assume that the shore is moving. But when you keep your eyes closely on the boat, you can see that the boat moves. Similarly, if you examine myriad things with a confused body and mind you might suppose that your mind and nature are permanent. When you practice intimately and return to where you are, it will be clear that nothing at all has unchanging self.

Firewood becomes ash, and it does not become firewood again. Yet, do not suppose that the ash is future and the firewood past. You should understand that firewood abides in the phenomenal expression of firewood, which fully includes past and future and is independent of past and future. Ash abides in the phenomenal expression of ash, which fully includes future and past. Just as firewood does not become firewood again after it is ash, you do not return to birth after death.

This being so, it is an established way in buddha-dharma to deny that birth turns into death. Accordingly, birth is understood as no-birth. It is an unshakable teaching in Buddha's discourse that death does not turn into birth. Accordingly, death is understood as no-death.

Birth is an expression complete this moment. Death is an expression complete this moment. They are like winter and spring. You do not call winter the beginning of spring, nor summer the end of spring.

Enlightenment is like the moon reflected on the water. The moon does not get wet, nor is the water broken. Although its light is wide and great, the moon is reflected even in a puddle an inch wide. The whole moon and the entire sky are reflected in dewdrops on the grass, or even in one drop of water.

Enlightenment does not divide you, just as the moon does not break the water. You cannot hinder enlightenment, just as a drop of water does not hinder the moon in the sky.

The depth of the drop is the height of the moon. Each reflection, however long of short its duration, manifests the vastness of the dewdrop, and realizes the limitlessness of the moonlight in the sky.

When dharma does not fill your whole body and mind, you think it is already sufficient. When dharma fills your body and mind, you understand that something is missing.

For example, when you sail out in a boat to the middle of an ocean where no land is in sight, and view the four directions, the ocean looks circular, and does not look any other way. But the ocean is neither round or square; its features are infinite in variety. It is like a palace. It is like a jewel. It only look circular as far as you can see at that time. All things are like this.

Though there are many features in the dusty world and the world beyond conditions, you see and understand only what your eye of practice can reach. In order to learn the nature of the myriad things, you must know that although they may look round or square, the other features of oceans and mountains are infinite in variety; whole worlds are there. It is so not only around you, but also directly beneath your feet, or in a drop of water.

A fish swims in the ocean, and no matter how far it swims there is no end to the water. A bird flies in the sky, and no matter how far it flies there is no end to the air. However, the fish and the bird have never left their elements. When their activity is large their field is large. When their need is small their field is small. Thus, each of them totally covers its full range, and each of them totally experiences its realm. If the bird leaves the air it will die at once. If the fish leaves the water it will die at once.

Know that water is life and air is life. The bird is life and the fish is life. Life must be the bird and life must be the fish.

It is possible to illustrate this with more analogies. Practice, enlightenment, and people are like this.

Now if a bird or a fish tries to reach the end of its element before moving in it, this bird or this fish will not find its way or its place. When you find your place where you are, practice occurs, actualizing the fundamental point. When you find you way at this moment, practice occurs, actualizing the fundamental point; for the place, the way, is neither large nor small, neither yours nor others'. The place, the way, has not carried over from the past and it is not merely arising now.

Accordingly, in the practice-enlightenment of the buddha way, meeting one thing is mastering it--doing one practice is practicing completely. Here is the place; here the way unfolds. The boundary of realization is not distinct, for the realization comes forth simultaneously with the mastery of buddha-dharma.

Do not suppose that what you realize becomes your knowledge and is grasped by your consciousness. Although actualized immediately, the inconceivable may not be apparent. Its appearance is beyond your knowledge. Zen master Baoche of Mt. Mayu was fanning himself. A monk approached and said, "Master, the nature of wind is permanent and there is no place it does not reach. When, then, do you fan yourself?"

"Although you understand that the nature of the wind is permanent," Baoche replied, "you do not understand the meaning of its reaching everywhere."

"What is the meaning of its reaching everywhere?" asked the monk again. The master just kept fanning himself. The monk bowed deeply.

The actualization of the buddha-dharma, the vital path of its correct transmission, is like this. If you say that you do not need to fan yourself because the nature of wind is permanent and you can have wind without fanning, you will understand neither permanence nor the nature of wind. The nature of wind is permanent; because of that, the wind of the buddha's house brings for the gold of the earth and makes fragrant the cream of the long river.

Written in mid-autumn, the first year of Tempuku 1233, and given to my lay student Koshu Yo of Kyushu Island. {Revised in} the fourth year of Kencho {I252}.

1b. Genjokoan

The Actualization of Enlightenment

by Eihei Dogen

Written in mid-autumn, 1233

Translated by Kosen Nishiyama and John Stevens (1975)

When all things are the Buddha-dharma, there is enlightenment, illusion, practice, life, death, Buddhas, and sentient beings. When all things are seen not to have any substance, there is no illusion or enlightenment, no Buddhas or sentient beings, no birth, or destruction. Originally the Buddhist Way transcends itself and any idea of abundance or lack--still there is birth and destruction, illusion and enlightenment, sentient beings and Buddhas. Yet people hate to see flowers fall and do not like weeds to grow.

It is an illusion to try to carry out our practice and enlightenment through ourselves, but to have practice and enlightenment through phenomena, that is enlightenment. To have great enlightenment about illusion is to be a Buddha. To have great illusion about enlightenment is to be a sentient being. Further, some are continually enlightened beyond enlightenment but some add more and more illusion.

When Buddhas become Buddhas, it is not necessary for them to be aware they are Buddhas. However, they are still enlightened Buddhas and continually realize Buddha. Through body and mind we can comprehend the form and sound of things. They work together as one. However, if it not like the reflection of shadow in a mirror, or the moon reflected in the water. If you look at only one side, the other is dark.

To learn the Buddhist way is to learn about oneself. To learn about oneself is to forget oneself. To forget oneself is to perceive oneself as all things. To realize this is to cast off the body and mind of self and others. When you have reached this stage you will be detached even from enlightenment but will practice it continually without thinking about it.

When people seek the Dharma [outside themselves] they are immediately far removed from its true location. When the Dharma has been received through the right transmission, one's real self immediately appears.

If you are in a boat, and you only look at the riverbank, you will think that the riverbank is moving; but if you look at the boat, you will discover that the boat itself is actually moving. Similarly, if you try to understand the nature of phenomena only through your own confused perception you will mistakenly think that your nature is eternal. Furthermore, if you have the right practice and return to your origin then you will see that all things have no permanent self.

Once firewood is reduced to ashes, it cannot return to firewood; but we should not think of ashes as the potential stare of firewood or vice-versa. Ash is completely ash and firewood is firewood. They have their own past, future, and independent existence.

Similarly, when human beings die, they cannot return to life; but in Buddhist teaching we never say that life changes into death. This is an established teaching of the Buddhist Dharma. We call it "non-becoming." Likewise, death cannot change into life. This is another principle of Buddha's Law. This is called "non-destruction". Life and death have absolute existence, like the relationship of winter and spring. But do not think of winter changing into spring or spring to summer.

When human beings attain enlightenment, it is like the moon reflected in the water. The moon appears in the water but does not get wet nor is the water disturbed by the moon. Furthermore the light of the moon covers the earth and yet it can be contained in small pool of water, a tiny dewdrop, or even one minuscule drop of water.

Just as the moon does not trouble the water in any way, do not think enlightenment causes people difficulty. Do not consider enlightenment an obstacle in your life. The depths of the dewdrop cannot contain the heights of the moon and the sky.

When the True Law is not totally attained, both physically and mentally, there is a tendency to think that we posses the complete Law and our work is finished. If the Dharma is completely present, there is a realization of ones insufficiencies.

For example, if you take a boat to the middle of the ocean, beyond the sight of any mountains, and look in all four directions, the ocean appear round. However, the ocean is not round, and its virtue is limitless. It is like a palace and an adornment of precious jewels. But to us, the ocean seems to be one large circle of water.

So we see this can be said of all things. Depending on the viewpoint we see things in different ways. Correct perception depends upon the amount of ones study and practice. In order to understand various types of viewpoints we must study the numerous aspects and virtues of mountains and oceans, rather than just circles. We should know that it is not only so all around us but also within us--even in a single drop of water.

Fish in the ocean find the water endless and birds think the sky is without limits. However, neither fish nor birds have been separated from their element. When their need is great, their utilization is great, when their need is small, the utilization is small. They fully utilize every aspect to its utmost--freely, limitlessly. However, we should know that if birds are separated from their own element they will die. We should know hat water is life for fish and the sky is life for birds. In the sky, birds are life; and in the water, fish are life. Many more conclusions can be drawn like this. There is practice and enlightenment [like the above relationships of sky and birds, fish and water]. However, after the clarification of water and sky, we can see that if there are birds or fish, that try to enter the sky or water, they cannot find either a way or a place. If we understand this point, there is actualization of enlightenment in our daily life. If we attain this this Way, all our actions are the actualization of enlightenment. This Way, this place, is not great or small, self or others, neither past or present--it exists just as it is.

Like this, if we practice and realize the Buddhist way we can master and penetrate each dharma;and we can confront and master any one practice. There is a place where we can penetrate the Way and find the extent of knowable perceptions. This happens because our knowledge co-exists simultaneously with the ultimate fulfillment of the Buddhist Dharma.

After this fulfillment becomes the basis of our perception, do not think that our perception is necessarily understood by the intellect. Although enlightenment is actualized quickly, it is not always totally manifested [it is too profound an inexhaustible for our limited intellect].

One day, when Zen Master Hotestsu of Mt. Mayoku was fanning himself, a monk approached and asked, "The nature of wind never changes and blows everywhere so why are you using a fan."

The master replied, "Although you know the nature of wind never changes you do not know the meaning of blowing everywhere". The monk then said, "Well, what does it mean?" Hotetsu did not speak but only continue to fan himself. Finally the monk understood and bowed deeply before him.

The experience, the realization, and the living, right transmission of the Buddhist Dharma is like this. To say it is not necessary to use a fan because the ntarue of the wind never changes and there will be wind even without one means that he does not know the real meaning of "never changes" or the wind's nature. Just as the wind's nature never changes, the wind of Buddhism makes the earth golden and cause the rivers to flow with sweet, fermented milk.

This was written in mid-autumn, 1233, and given to the lay disciple Yo-ko-shu of Kyushu.

1c. Genjokoan

The Issue at Hand

by Eihei Dogen

Translated by Thomas Cleary