ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

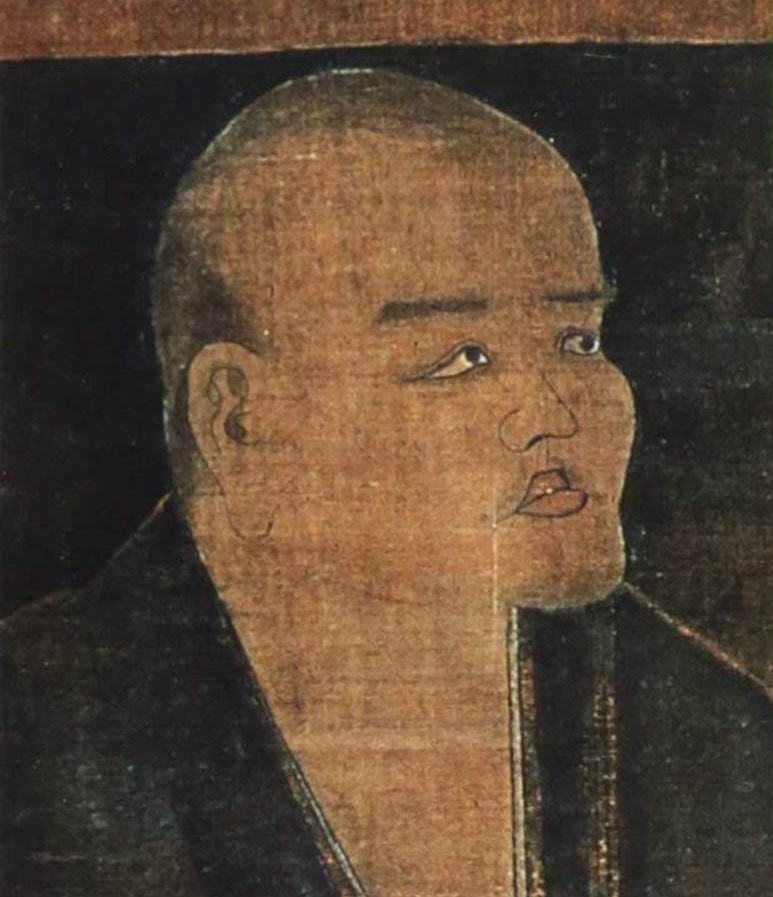

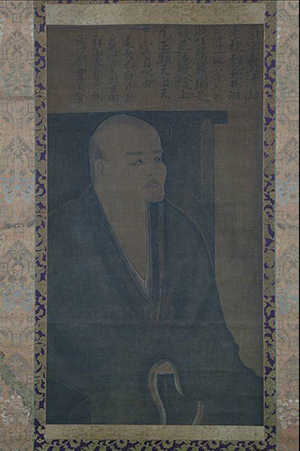

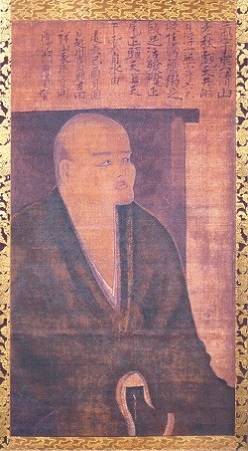

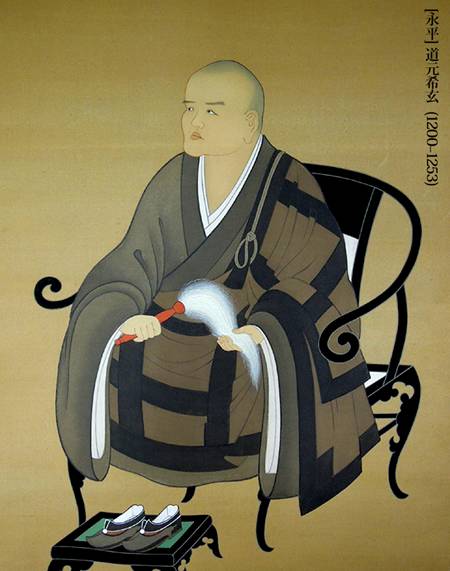

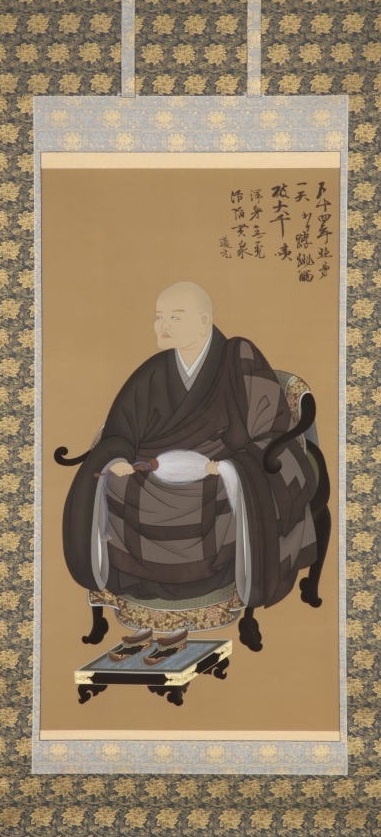

[永平] 道元希玄 [Eihei] Dōgen Kigen (1200-1253)

道元禅師観月図

Viewing the Moon, Dōgen's Self-portrait

Holdbanéző önarckép

(1249)

Tartalom |

Contents |

Végh József: PDF: Dógen Zen mester magyarul elérhető írásai Hrabovszky Dóra: Fukan-zazen-gi A zazen dicsérete Az ülő meditáció szabályai (Sóbógenzó zazengi) A zazen ösvénye A szívében a megvilágosodás szellemével élő lény (bódhiszattva) négy irányadó tevékenysége Életünk kérdése (Gendzsókóan 現成公案) PDF: Az Út Gyakorlásában Követendő pontok |

真字正法眼蔵 [Mana/Shinji] Shōbōgenzō 仮字正法眼蔵 [Kana/Kaji] Shōbōgenzō 普勧坐禅儀 Fukan zazengi 学道用心集 Gakudō-yōjinshū Advice on Studying the Way 永平清規 Eihei shingi Eihei Rules of Purity 永平廣錄 Eihei kōroku Dōgen's Extensive Record 宝慶記 Hōkyō-ki Memoirs of the Hōkyō Period 傘松道詠 Sanshō dōei Verses on the Way from Sanshō Peak

孤雲懷奘 Kōun Ejō (1198-1280) 修證義 Shushō-gi, compiled in 1890 Kōshō-ji PDF: The Life of Dōgen Zenji

|

"Pluck out the Buddha eye

and sit in its hollow!"

„Vájd ki Buddha félszemét

és ülj a szemgödrébe!"

Dôgen

(Terebess Gábor fordítása)

![]()

Végh József:

PDF: Dógen zen mester élete és művei, 34-35. oldal

Dógen Hókjódzsi kolostorban őrzött önarcképe

A kor szokása szerint, szerzetesei kérésére 1249-ben, a nyolcadik hónap teliholdjára tekintve, készített magáról egy képet, amelyre a következő szango stílusú kínai verset írta:

Üde kedv szegi ezt az őszt

És ezt a vén hegyi embert.

Szamárként mered az ég mennyezetére,

Ahol a fehéren ragyogó hold lebeg.

Semmi sem közelít,

De ki sincs zárva semmi.

Levessel, rizzsel tele,

Derűvel hagyom magam lenni.

Eleven bizsergés a szamárfejemtől a farkamig,

Ég fölöttem, ég alattam,

Én a felhő, víz a bölcsőm.*

Általánosabban fogalmazva, nem személyre, hanem az őszi tájra figyelve így is olvasható ugyanaz a vers:

A hegyoldalt kopasz fák állják tele,

Ezen a csípős tiszta őszi éjjelen,

A telihold úszik a háztetők fölé:

Nem függ semmitől,

És nem tartozik sehová,

Szabad, mint a teli rizses csésze gőze,

Önkéntelen, mint az úszkáló és csobbanó hal,

Mint a gomolygó felhők, és folyó vizek.

![]()

*Tanahashi Kazuaki: Moon in a Dewdrop: Writings of Zen Master Dōgen, North Point Press, Berkeley, 1985, on the cover page:

Fresh, clear spirit covers old mountain man this autumn.

Donkey stares at the sky ceiling; glowing white moon floats.

Nothing approaches. Nothing else included.

Buoyant, I let myself go -- filled with gruel, filled with rice.

Lively flapping from head to tail,

Sky above, sky beneath, cloud self, water origin.

*The Zen Poetry of Dōgen. Verses from the Mountain of Eternal Peace by Steven Heine. Tuttle Shokai Ltd., Charles E Tuttle. 1997, (C15=EK 10.3b):

Accompanying a self-portrait created while viewing the

harvest moon on the eighth month/fifteenth day {harvest

moon}, 1249The mountain filled with leafless trees

Crisp and clear on this autumn night;

The full moon floating gently above the cluster of roofs,

Having nothing to depend on,

And not clinging to any place;

Free, like steam rising from a full bowl of rice,

Effortless, as a fish swimming and splashing back and forth,

Like drifting clouds or flowing water.

Dogen's Harvest Moon Poem and Self-Portrait

by Hyatt Carter

On an auspicious evening in the year 1249, after taking time to observe the harvest moon, Dogen was inspired to write a poem to celebrate the occasion:

Misty autumn, the night crisp and clean on this old mountain;

I see water in the well, reflecting sky, a bright moon floating.

One does not depend . . . six cannot contain.

Letting go, I am lightened, lifted up, buoyant with rice and gruel—

Aloft and lively, like a carp leaping free, flapping from head to tail,

Sky above, sky below, light as a cloud that comes from water. 1

Here is Dogen's original Chinese text 2 —

氣宇爽清山老秋、

覷天井皓月浮。

一無寄六不收。

任騰騰粥足飯足、

活 鱍鱍正尾正頭 、

天上天下雲自水由。

The poem later found a permanent place as an inscription on a self-portrait that Dogen painted at about the same time:

The self-portrait has been preserved and is housed in a special building, along with other temple treasures, at Hōkyō-ji (宝慶寺), a Soto Zen monastery near Ono City in Fukui Prefecture.

If you look closely at the first Chinese character in the upper right corner of the painting, you will see that it is 氣, the first character in the poem as transcribed above. The poem is arrayed in vertical columns in the painting, running from right to left, whereas I have laid it out in horizontal rows.

As an effort to enhance your appreciation, and understanding, of this fine poem, I have put together a line-by-line commentary.

Line 1:

Dogen had a great and enduring love for the mountains. Eihei (永平), which translates as “eternal peace,” was the name he gave to the monastery he built and the mountain whereon he built it. Many times, in his sermons to his monks, he refers to himself a mountain monk (山僧). Therefore, “mountain” in the first line can refer to the actual mountain where Dogen observed the harvest moon, to Dogen himself, or both.

Eihei-ji (永平寺), the monastery that Dogen built and founded in 1244, is still there today on Dogen’s mountain of eternal peace.

Line 2:

As a metaphor for enlightenment, the moon reflected in water was a recurring image in Dogen’s writings. One of my favorite examples is his waka on impermanence:

無常

世の中は

何にたとへん,

水鳥の,

はしふる露に

やとる月影。

Impermanence

To what shall I

Liken the world?

Moonlight, reflected

In dewdrops,

Shaken from a crane’s bill.3

A Zen question: Is Dogen watching the moon in the water or . . . is the moon watching Dogen?

Line 3:

When Dogen says, “six cannot contain,” he is making an allusion to a koan that involves the famous Zen master, Yunmen (雲門). The main case of this Zen story goes like this:

A monk asked Yunmen, “What is the Dharmakaya?”

Men said, “Six cannot contain.”4

Original Chinese:

僧問雲門。如何是法身。

門云。六不收。

The Dharmakaya (法身), or Dharma-Body, is the true nature of things. The “six” may refer to what in Chinese thought is known as the six elements (earth, water, fire, wind, space, and consciousness) or the six senses (seeing, hearing, tasting, smelling, touching, and consciousness).

Shakyamuni Buddha said: “The true Dharmakaya is like the empty sky, and it manifests itself . . . like the moon on water.”

Line 4

The first character, 任, as a verb, means to “trust,” “allow,” or “let,” and with the theme of lightness or levity that commences in this line and is continued to the end of the poem, “letting go” seems le mot juste. And “letting go” (or nonattachment or non-abiding) is a central teaching in Zen Buddhism. One of Dogen’s most pivotal ideas, perhaps second only to genjokoan, is what he calls shinjin datsuraku, the “dropping off of body and mind,” which he aligns with enlightenment.

騰, the character that is repeated in the fourth line, by itself means “to jump” or “to gallop,” which seems fitting since the component in the lower right, 馬, is the character for “horse,” and horses are known to gallop. Repeated, 騰騰, the two characters together mean “to rise,” “to soar,” or “to ascend.” One of the reasons I chose the word “lightened” is that it is only two letters away from “enlightened.” Dogen liked to play with words and so do I.

Rice and gruel are staples in the Zen diet and Dogen spoke often of the metaphysics of eating. The spirit of Zen permeates or imbues all activities.

Line 5

“Aloft and lively, like a carp leaping free . . .”

This is my translation of the phrase “活鱍鱍 . . . ,” pronounced kappatsupatsu in Japanese. I could not find the character 鱍 in any of my Chinese dictionaries but, fortunately, a search online turned up this entry:

“‘Brisk and lively’ (kappatsupatsuchi 活鱍鱍地)5 is a loose translation of a Chinese idiom expressing the quick, powerful movements of a fish, especially of the carp as it leaps from the water . . .”6

Line 6

One of the more poetic terms, in Japanese, for a Zen monk is unsui. The two characters that make up this term are— 雲水 —and they mean “clouds and water,” describing the freedom of the Zen monk.

At least one of the meanings of clouds and water in the last line is that it is a reference to Dogen himself, that old mountain monk of the first line who, as unsui, also enjoyed the freedom “to drift like a cloud and flow like water.”7

If we turn once again to Dogen’s self-portrait, a close inspection reveals that four columns of Chinese characters follow the poem. This is a colophon giving some particulars (such as when and where) about the composition. Here is the colophon, in columns as in the painting:

闢 祥 日 建

沙 山 越 長

門 永 州 己

希 平 吉 酉

玄 寺 田 月

自 開 郡 圓

贊 吉

田

Translated, it reads:

Kenchō era, the year 1249, day of the full moon, at Eiheiji temple on Kichijo mountain, in Yoshida-gun, the province of Echizen, Zen monk Kigen’s verse of praise.8

Kigen? Glad you asked.

Dogen was known variously as Eihei Dogen (永平道元), Dogen Zenji (道元禅師), and Dogen Kigen (道元希玄).

Dogen (道元) means “Source of the Way,” Eihei (永平) means “Eternal Peace,” Zenji (禅師) means “Zen Master,” and Kigen (希玄) means “rare and profound.”

Rarely is eternal peace so profoundly mastered as by Dogen.

Notes

1. My translation.

2. So far as I know, this is the first time Dogen’s poem, in digital form, has been presented online. I did several online searches, using different character combinations, but there were no hits.

To generate the Chinese text, I used Adobe Photoshop to make a high-resolution picture of Dogen’s Self-Portrait. I could then “zoom in” on individual characters at high magnifications and this facilitated recognition even though, as you can see, some of the characters are rather indistinct.

3. English translation by Steven Heine.

Waka (和歌) is a form of Japanese poetry with 5 lines and a total of 31 syllables in a 5-7-5-7-7 pattern.

4. The koan is number 47 in the famous koan collection known as The Blue Cliff Record (Hekiganroku 碧巖錄).

5. The character 地, at the end of the phrase 活鱍鱍地, has an adverb-forming function, like English -ly.

6. This is from the Supplemental Notes to Carl Bielefeldt’s translation of “Zanmai o zanmai,” chapter 72 in Dogen’s 95-Shobogenzo.

“Brisk and lively,” as Dogen uses it here, refers to zazen, or seated meditation. To place it in context, here’s the passage, as translated by Bielefeldt:

まさにしるべし、坐の盡界と餘の盡界と、はるかにことなり。

We should realize that there is a vast difference between all realms of sitting and all other realms.

. . . . . . .

正當坐時、その坐、それいかん。

At the very moment we are sitting, what about that sitting?

翻筋斗なるか、活鱍鱍地なるか、思量か、不思量か、作か、無作か。

Is it a flip? Is it “brisk and lively”? Is it thinking? Is it not thinking? Is it making? Is it without making?

坐裏に坐すや、身心裏にすや、坐裏身心裏等を脱落して坐すや。

Are we sitting within sitting? Are we sitting within body and mind? Are we sitting having sloughed off “within sitting,” “within body and mind,” and so on?

恁麼の千端萬端の參究あるべきなり。

We should investigate one thousand points, ten thousand points, such as these.

身の結跏趺坐すべし、心の結跏趺坐すべし、身心脱落の結跏趺坐すべし。

We should do the sitting with legs crossed of the body; we should do the sitting with legs crossed of the mind; we should do the sitting with legs crossed of the body and mind sloughed off.

7. Another poetic expression, used by Taoists and Buddhists, that conveys the spirit of lightness and levity, is . . . “riding the wind.” 御風8. My translation. HyC

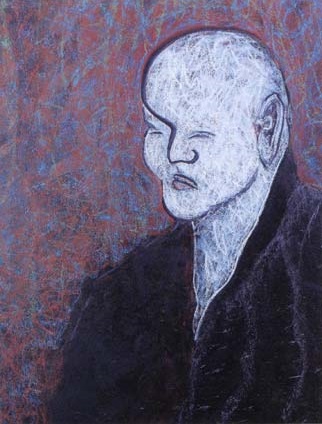

Contemporary interpretations:

Dogen peint par

Reikai Vendetti (alias Jean-Claude Gaumer)

Dogen. Illustration by 棚橋一晃 Tanahashi Kazuaki

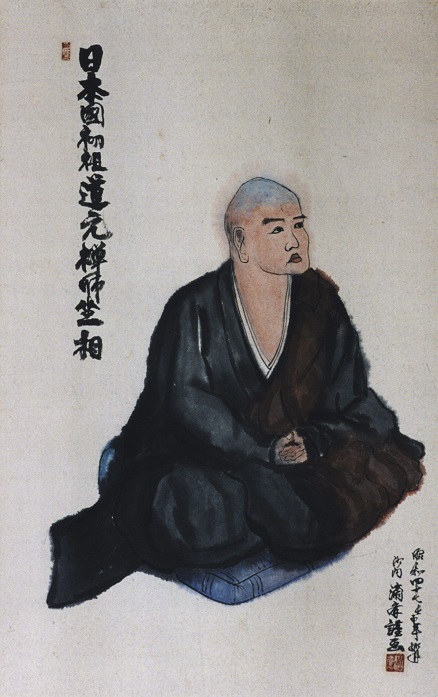

Dogen by

伊野孝行 Ino Takayuki (1971-)

AI-generated image by Pál Terebess (2023)

*