ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

隱元隆琦 Yinyuan Longqi (1592-1673)

(Rōmaji:) 隠元隆琦 Ingen Ryūki, aka 大光普照國師 Daikō Fushō Kokushi

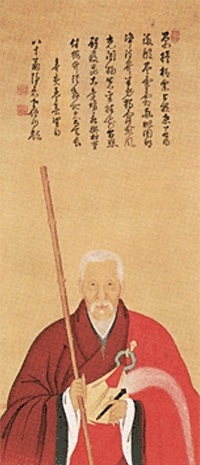

喜多道矩 (長兵衛) Kita Dōku (Chōbei) (active ca. 1657-63), Portrait of Yinyuan Longqi.

Central scroll of a triptych with Muan Xingtao (1611-84) and Jifei Ruyi (1616-71). Self-eulogydated 1668 (fourth month). Seal: “Chō.”

From a set of three hanging scrolls, ink and colours on paper, each 112.5 x 44.9 cm. Kobe City Museum.

Ingen Ryūki, the founder of the Obaku Zen school; 1592-1673. Born in Fuchien Province (福建省 Fukkensho, Fujiansheng), he practiced Zen on Mt. Huang-po 黄檗 (Obaku), attained satori at the age of forty-seven and came to Nagasaki in 1654. Under the imperial patronage, he built a temple in Uji, South East of Kyoto, and named it Manpukuji 万福寺; this temple became the head temple of the Obaku school 黄檗宗.

Yinyuan Longqi. (J. Ingen Ryūki 隠元隆琦) (1592–1673). Chinese CHAN master

and founding patriarch of the Japanese ŌBAKUSHŪ. Yinyuan was a native of

Fuzhou, in present-day Fujian province. He began his training as a monk in his

early twenties on PUTUOSHAN and was formally ordained several years later

at Wanfusi on Mt. Huangbo. Yinyuan continued his training under the Chan

master MIYUN YUANWU and, while serving under the Chan master FEIYIN

TONGRONG at Wanfusi Yinyuan, was formally recognized as an heir to

Feiyin’s lineage in 1633. Seven years later, in 1640, Yinyuan found himself at the

monastery of Fuyansi in Zhejiang province and at Longquansi in Fujian province

in 1645. The next year, in 1646, he returned to Mt. Huangbo and revitalized the

community at Wanfusi. In 1654, at the invitation of Yiran Xingrong (1601–1668),

the abbot of the Chinese temple of Kōfukuji in Nagasaki, Yinyuan decided to

leave China to escape the succession wars and political turmoil that ha

accompanied the fall of the Chinese Ming dynasty. He was to be accompanied

by some thirty monks and artisans. Due to political issues, however, Yinyuan was

only allowed to enter Japan a year later in 1655. That same year, largely through

the efforts of the Japanese monk Ryōkei Shōsen (1602–1670), the abbot of

MYŌSHINJI, Yinyuan was allowed to stay at Ryōkei’s home temple of Fumonji

under virtual house arrest. The next year when Yinyuan expressed his wishes to

return to China, Ryōkei arranged a visit to Edo and an audience with the young

shōgun. At the end of 1658, Yinyuan made the trip to Edo and won the patronage

of the shōgun and his ministers. With their support, Yinyuan began the

construction of MANPUKUJIs in Uji in 1661. The site came to be known as Mt.

Ōbaku, the Japanese pronunciation of his mountain home of Huangbo, and served

as the center for the introduction of Ming-dynasty Chan into Japan. Yinyuan’s

teachings, especially those concerning monastic rules, catalyzed institutional and

doctrinal reform among the entrenched Japanese ZEN communities. In 1664,

Yinyuan left his head disciple MU’AN XINGTAO in charge of all administrative

matters involving the monastery and retired to his hermitage on the compounds

of Manpukuji. Nine years later Emperor Gomizunoo (r. 1611–1629) bestowed

upon him the title state preceptor (J. kokushi, C. guoshi) Daikō Fushō (Great

Radiance, Universal Illumination). He died shortly thereafter. Yinyuan brought

many texts and precious art objects with him from China, and composed

numerous texts himself such as the Huangbo yulu, Hongjie fayi, Fushō kokushi

kōroku, Ōbaku oshō fusō goroku, Ingen hōgo, and Ōbaku shingi.

The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism (2014)

PDF: Leaving for the Rising Sun: The Historical Background of Yinyuan Longqi's Migration to Japan in 1654

by Jiang Wu

Asia Major (Third Series) vol. 17, part 2 (2004): 89-120.

PDF: Building a Dharma Transmission Monastery in Seventeenth - Century China : The Case of Mount Huangbo

by Jiang Wu

Journal of East Asian History 31 (June 2006): 29-52.

PDF: "Taikun's Zen Master from China: Yinyuan, the Tokugawa Bakufu, and the Founding of Manpukuji in 1661"

by Jiang Wu

Journal of East Asian History 38 (2014)

PDF: Leaving for the Rising Sun: Chinese Zen Master Yinyuan Longqi and the Authenticity Crisis in Early Modern East Asia

by Jiang Wu

New York: Oxford University Press, 2015, xiv + 355 pp.

Yinyuan Longqi’s Dharma Lineage

[...]

菩提達磨 Bodhidharma, Putidamo (Bodaidaruma ?-532/5)

大祖慧可 Dazu Huike (Taiso Eka 487-593)

鑑智僧璨 Jianzhi Sengcan (Kanchi Sōsan ?-606)

大毉道信 Dayi Daoxin (Daii Dōshin 580-651)

大滿弘忍 Daman Hongren (Daiman Kōnin 601-674)

大鑑慧能 Dajian Huineng (Daikan Enō 638-713)

南嶽懷讓 Nanyue Huairang (Nangaku Ejō 677-744)

馬祖道一 Mazu Daoyi (Baso Dōitsu 709-788)

百丈懷海 Baizhang Huaihai (Hyakujō Ekai 750-814)

黃蘗希運 Huangbo Xiyun (Ōbaku Kiun ?-850)

臨濟義玄 Linji Yixuan (Rinzai Gigen ?-866)

興化存獎 Xinghua Cunjiang (Kōke Zonshō 830-888)

南院慧顒 Nanyuan Huiyong (Nan'in Egyō ?-952)

風穴延沼 Fengxue Yanzhao (Fuketsu Enshō 896-973)

首山省念 Shoushan Shengnian (Shuzan Shōnen 926-993)

汾陽善昭 Fenyang Shanzhao (Fun'yo Zenshō 947-1024)

石霜/慈明 楚圓 Shishuang/Ciming Chuyuan (Sekisō/Jimei Soen 986-1039)

楊岐方會 Yangqi Fanghui (Yōgi Hōe 992-1049)

白雲守端 Baiyun Shouduan (Hakuun Shutan 1025-1072)

五祖法演 Wuzu Fayan (Goso Hōen 1024-1104)

圜悟克勤 Yuanwu Keqin (Engo Kokugon 1063-1135)

虎丘紹隆 Huqiu Shaolong (Kukyū Jōryū 1077-1136)

應庵曇華 Yingan Tanhua (Ōan Donge 1103-1163)

密庵咸傑 Mian Xianjie (Mittan Kanketsu 1118-1186)

破庵祖先 Poan Zuxian (Hoan Sosen 1136–1211)

無準師範 Wuzhun Shifan (Bujun Shipan 1177–1249)

雪巖祖欽 Xueyan Zuqin (Seggan Sokin (1215–1287)

高峰原妙 Gaofeng Yuanmiao (Kōhō Gemmyō 1238-1295)

中峯明本 Zhongfeng Mingben (Chūhō Myōhon 1263–1323)

千巖元長 Qianyan Yuanzhang (Sengan Genchō 1284–1357)

萬峰時蔚 Wanfeng Shiwei (Manhō Jijō 1303–1381)

寶藏普持 Baozhang Puchi (Hōzō Fuji ?-?)

虗白慧旵 Xubai Huichan (Kihaku Egaku 1372–1441)

海舟普慈 Haizhou Puci (Kaishū Eiji 1355-1450)

寶峰明瑄 Baofeng Mingxuan (Hōbō Myōken ?-1472)

天奇本瑞 Tianqi Benrui (Tenki Honzui ?-1508)

無聞正聰 Wuwen Mingcong (Mubun Shōsō (?-1543)

月心德寶 Xiaoyan Debao (Getsushin Tokuhō 1512–1581)

幻有正傳 Huanyou Zhengchuan (Genyū Shōden 1549-1614)

蜜雲円悟 Miyun Yuanwu (Mitsu'un Engo 1566-1642)

費隠通容 Feiyin Tongrong (Hi'in Tsuyo 1593-1661)

隠元隆琦 Yinyuan Longqi (Ingen Ryuki 1592-1673)

INGEN RYUKI

Richard Bryan McDaniel: Zen Masters of Japan. The Second Step East. Rutland, Vermont: Tuttle Publishing, 2013.

Munan's asceticism was one response to the spiritual malaise into which the Rinzai School had fallen, as was Suzuki Shosan's secular Nio-Zen. Another response was the Obaku School.

Because of the isolationist policies of the current Shogunate, there were few foreigners in the Japanese isles. Chinese businessmen, however, had been allowed to set up a small community in Nagasaki. There, in circumstances similar to those that would bring Shunryu Suzuki to San Francisco in the 1950s, these merchants sent messages back to China asking that Chinese priests be sent to minister to them. They were not looking for spiritual direction; they wanted Buddhist clerics who would offer rites with which they were familiar, rituals to petition the gods to protect their ships and cargo, rituals to mark the transitions points in life—births, marriages, funerals, and anniversary rites.

The first group of Chinese missionaries, which arrived in 1620, included Dosha Chogen (Daozhe Chaoyuan), who would become one of Bankei Yotaku's teachers. Dosha was a strong teacher and gathered a number of disciples, but Dosha was eclipsed by a second Chinese teacher, Ingen Ryuki (Yinyuan Longqi), who came to Nagasaki at the invitation of the local authorities. Ingen was already a well-known teacher in China, and a rivalry broke out between his followers and those of Dosha, which eventually resulted in Dosha returning to China.

Ingen was fleeing the turmoil then occurring in China after the collapse of the Ming Dynasty, and he welcomed the opportunity to travel to Japan. He brought with him some twenty disciples and a group of artisans skilled in the architectural techniques then current in China.

Ingen's fame preceded him, and he received a warm welcome in Nagasaki. As a foreigner, there were restrictions placed on his movements, but he managed to find friends who intervened on his behalf. He soon acquired a large number of Japanese disciples. Because Ingen could trace his Dharma lineage directly back to the founder of the Rinzai School, Rinzai Gigen (Linji Yixuan, cf. Zen Masters of China, Chapter Fifteen), some of these Japanese followers hoped that Ingen would be appointed abbot of Myoshinji.

Other members of the Rinzai community, including Gudo Toshoku, were not comfortable with the suggested appointment. They objected to what they considered the “foreign flavor” of Ingen's Zen. Although the Japanese Rinzai School had been based on Tang and Song Dynasty models, those traditions had been modified over time and were now thoroughly assimilated into Japanese culture. The Ming Dynasty Zen of Ingen and his followers seemed peculiar. The chants were unfamiliar and set to Chinese melodies which sounded odd to the Japanese ear. The imagery of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas was unusual. But the most off-putting element was the inclusion of Pure Land practices, in particular the recitation of the nembutsu, which many Japanese Rinzai priests still considered out of keeping with their practice, but which Ingen and his followers refused to curtail.

As a result, Ingen's appointment to Myoshinji was successfully blocked. Ingen's first inclination was to return to China, but his followers encouraged him to remain and arranged for a temple to be built for him on the hills of Uji, outside of Kyoto. Ingen called the hill Obaku (Huangbo) after the Chinese site where his former monastery had been located. The temple was named Manpukuji. The artisans who had formed part of Ingen's entourage when he arrived in Japan were able to construct a building in Chinese Ming Style.

Ingen considered Manpukuji a Rinzai temple, but the Rinzai establishment did not. The result was that it inadvertently became the main temple of a third and new Zen school—known as the Obaku School from the temple's location. The temple differed in a number of respects from Japanese temples, not only in physical form but in practices as well. Ingen's monastic rules followed Chinese protocols rather than Japanese. Even the way the monks ate differed. Instead of using the nested orioki bowls Japanese monks were provided with, the meals at Manpukuji were served from a single bowl around which monks gathered and into which they dipped their chopsticks communally.

The new sect had some initial success, drawing prospective students away from Rinzai schools like Myoshinji, which only irritated the Japanese hierarchy further. Some of these students may have been drawn to Manpukuji because of its exotic atmosphere, but others were seeking spiritual guidance which they were no longer certain they could find in the Rinzai or Soto traditions.

The new school expanded quickly. By the time of Ingen's death, he had established twenty-four Obaku temples in Japan.

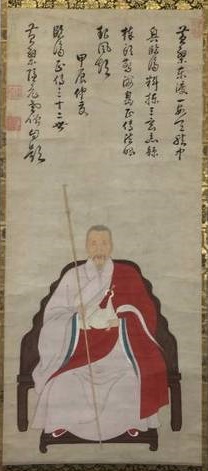

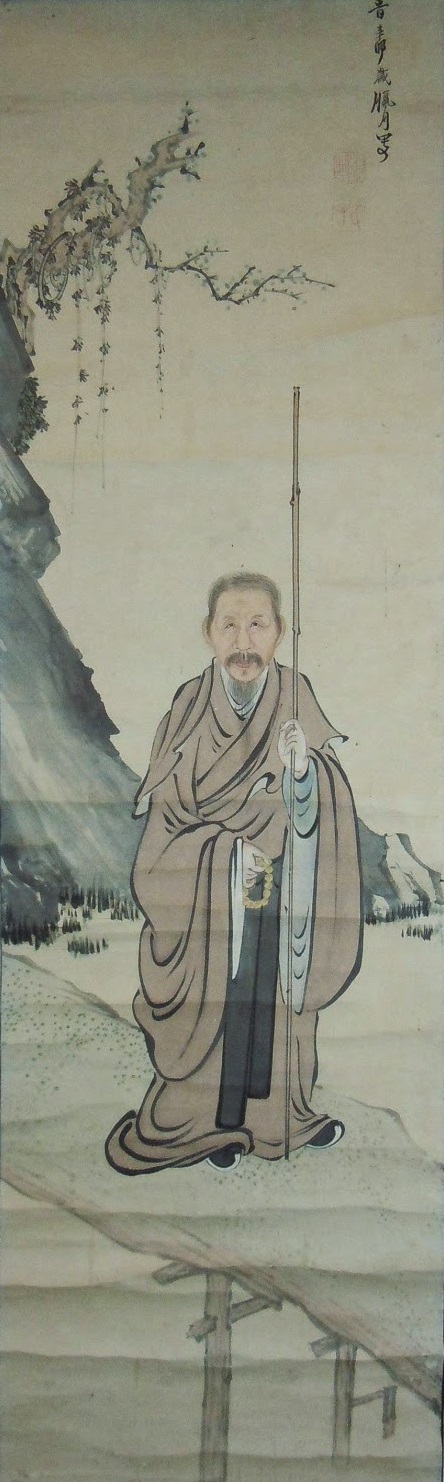

Portraits of Yinyuan Longqi

喜多元規 Kita Genki (active ca. 1664-1709), Portrait of Yinyuan Longqi at Eighty.

Self-eulogy dated 1671 (first month, fifteenth day). Artist's seal: “Genki.”

Hanging scroll, ink and colours on paper, 138.4 x 60.2 cm. Shōindō, Manpukuji, Kyoto Pref.

隐元禅師画像

http://jd.cang.com/2222150.html

喜多元規 Kita Genki (active ca. 1664-1709), Portrait of Yinyuan Longqi.

長崎・東明山興福寺 Nagasaki, Tōmeizan Kōfuku-ji (an Ōbaku Zen Buddhist temple established in 1624)

I came across an interesting portrait of Yinyuan in an auction page. It was painted in the year Xinmao 辛卯 (either 1651 or 1711). The style is so different from the portraits by the Kita family and looks more like the literati painting style. One source said that it was painted by another Chinese monk Donggao Xinyue 东皋心越, for whom van Gulik 高羅佩 published a book in 1944. (See 明末义僧东皋禅师集刊.) But Xinyue died in 1696 and in 1651 he was only 13 as Tanaka Chisei 田中智誠 osho pointed out. Tanaka osho also confirms that Xinyue did paint Yinyuan's portrait in 1680 but it was a copy from a previous painting.

If this was indeed painted in 1651 before Yinyuan left China in 1654, this is going to be a significant discovery.

Posted by Jiang Wu

http://leavingfortherisingsun.blogspot.hu/2015/03/attention-art-historians-who-painted.html

木像 Mokuzō (wooden effigy) of Yinyuan Longqi

Portrait of Buddhist Monks of Obaku Sect, 1600s, Cleveland Museum of Art

仏祖諸師の肖像画|紅葉の寺 法輪山覚苑寺<下関市>

Obaku Patriarchal Portraits

http://www.kakuonji.com/busso.html

釈迦牟尼仏 Shākyamuni Buddha |

摩訶迦葉尊者 Mahākāshyapa |

阿難尊者 Ānanda |

菩提達磨大師 Bodhidharma (?-532/5) |

|

弘忍大師 Hongren (601-674) |

慧能大師 Huineng (638–713) |

南岳懐譲禅師 Nanyue Huairang (677-744) |

馬祖道一禅師 Mazu Daoyi (709-788) |

百丈懐海禅師 Baizhang Huaihai (720-814) |

黄檗希運禅師 Huangbo Xiyun (?-850?) |

臨済義玄禅師 Linji Yixuan (?-866) |

|

|

||

悦山道宗禅師 Yueshan Daozong (1629-1709) |

祖春元回禅師 Zuchun Yuanhui (1657-1724) |