ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

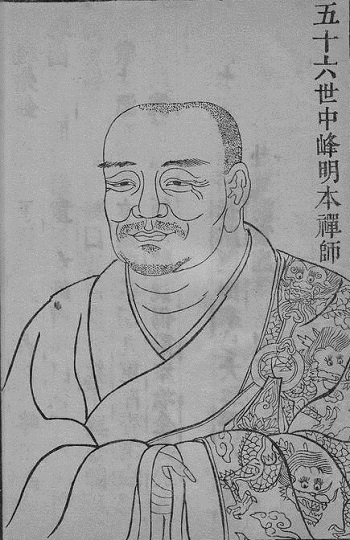

中峰明本 Zhongfeng Mingben (1263-1323)

(Rōmaji:) Chūhō Myōhon

![]()

Mingben's stūpa on Mount Tianmu

PDF: Natasha Lynne Heller, Illusory abiding: The life and work of Zhongfeng Mingben (1263–1323)

Harvard University, 2005

My dissertation examines the figure of Zhongfeng Mingben, one of the most eminent Chan monks of the Yuan dynasty. While Mingben never left southeast China, he attracted followers from throughout China and from abroad. These followers were not only Buddhist monks but also elite lay men and women. Mingben refused to head large monasteries, but instead traveled and lived in the small cloistered communities that he founded in the Jiangnan region. Thus he was a figure of both religious and cultural importance but also one who stood outside the monastic mainstream. Mingben's approach to the study of Chan rejected reliance on the textual tradition and instead demanded rigorous, long-term attention to the cultivation of mind. This underlying religiosity was central to all his pursuits, in both Buddhist and literati realms. My study is divided into three parts. The first two chapters consider the context and construction of Mingben's life. Chapters three and four analyze his contributions to Chan through his teachings and through the monastic code he authored. Chapters five through seven consider Mingben in relation to his literati followers, with special attention to his use of cultural forms to convey his core teachings.

A groundbreaking monograph on Yuan dynasty Buddhism, Illusory Abiding offers a cultural history of Buddhism through a case study of the eminent Chan master Zhongfeng Mingben. Natasha Heller demonstrates that Mingben, and other monks of his stature, developed a range of cultural competencies through which they navigated social and intellectual relationships. They mastered repertoires internal to their tradition—for example, guidelines for monastic life—as well as those that allowed them to interact with broader elite audiences, such as the ability to compose verses on plum blossoms. These cultural exchanges took place within local, religious, and social networks—and at the same time, they comprised some of the very forces that formed these networks in the first place. This monograph contributes to a more robust account of Chinese Buddhism in late imperial China, and demonstrates the importance of situating monks as actors within broader sociocultural fields of practice and exchange.

Heller, N. (2014). Illusory Abiding: The Cultural Construction of the Chan Monk Zhongfeng Mingben (Harvard East Asian Monographs) (Illustrated ed.). Harvard University Asia Center.

Zhongfeng Mingben and the Case of the Disappearing Laywomen

by Natasha Heller

Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal (2013, 26: 67-88)

PDF: "The Chan Master as Illusionist: Zhongfeng Mingben's Huanzhu Jiaxun"

by Natasha Heller

Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Volume 69, Number 2, December 2009

http://www.academia.edu/2851616/The_Chan_Master_as_Illusionist_Zhongfeng_Mingbens_Huanzhu_Jiaxun

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jas/summary/v069/69.2.heller.html

To examine the metaphor of illusion in Chinese Buddhism, Natasha Heller focuses on “Huanzhu jiaxun” 幻住家訓 (The family instructions of “Illusory Abiding”) by the Chan monk Zhongfeng Mengben 中峰明本 (1263–1323). Considering Mingben's usage of the term “illusory” (huan ) in relation to its history in non-Buddhist and Buddhist sources, she examines how he addressed the use of language, with special reference to the Chan concept of “observing the key phrase” (kanhua). Mingben remained within the established philosophical discourse on illusion but, Heller argues, shifted away from metaphors related to the concept; instead he emphasized the character huan to suggest an alternative to intellectual analysis of words. He thereby advanced the discussion of kanhua Chan while affirming the ultimate illusoriness of such practice.

"7: Between Zhongfeng Mingben and Zhao Mengfu: Chan Letters in Their Manuscript Context"

by Natasha Heller, Buddhist Manuscript Cultures III, New York: Routledge, 2009, pp. 109–123.

PDF: Zhongfeng Mingben’s Illusory Man

Translated by William Dufficy

Introduction and footnotes by ewk

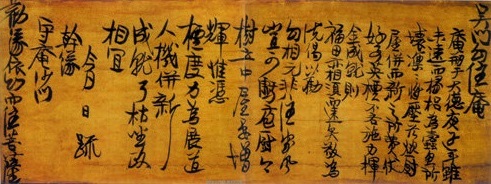

中峰明本书法(柳叶体) Zhongfeng Mingben's Calligraphy

A Master of His Own: The Calligraphy of the Chan Abbot Zhongfeng Mingben (1262-1323)

by Uta Laurer (1961-)

(Studien zur Ostasiatischen Schriftkunst, 5.) 164 pp, 43 plates. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2002.

http://books.google.hu/books?id=fvVIrEt9DHYC&printsec=frontcover&hl=hu&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Contents

- Terminology 11

- Table of the Eight Standard Strokes of Chinese Characters 12

- I Traditions and Prerequisites of Chan Calligraphy

- 1. The Tradition of the Scholar Officials 13

- 2. Buddhist Tradition apart from Chan 20

- 3. Chan Calligraphers 28

- 4 Aesthetic Concepts in Chan Calligraphy 32

- 5. Aesthetic Concepts in Scholar Official Calligraphy 40

- 6. Some Common Points between Chan and Scholar Official

- Calligraphy 46

- II Biographical and Historical Framework

- 1. The Biography of Zhongfeng Mingben 49

- 2. Zhao Mengfu and other Literati 58

- 2.1. Zhao Mengfu 59

- 2.2. Xianyu Shu 64

- 2.3. Deng Wenyuan 67

- 2.4. Feng Zizhen 69

- 2.5. Yu Ji 71

- 2.6. Zhang Yu 72

- 2.7. Yang Weizhen 74

- 2.8. Kangli Naonao 76

- 2.9. Rao Jie 78

- 3. Zhongfeng Mingben's Buddhist Connections 79

- 3.1. Qu Tingfa 79

- 3.2. Yuan Jian 80

- 3.3. King Ch'ung-son 80

- 3.4. Chushi Fanqi 81

- 3.5. Yi'an 81

- 3.6. Jueji Yongzhong 82

- 3.7. Ka'ō Sōnen 84

- 3.8. Tesshfi Tokusai 85

- 3.9. Enkei Soyū 86

- 3.10. Muin Genkai 86

- 3.11. Gyōkai Honjō 86

- III The Oeuvre of Zhongfeng Mingben

- 1. Discussion of the Works 88

- 2. The Willow-leaf Style 89

- 3. Calligraphic Works 92

- 3.1. Portraits of Zhongfeng Mingben with Self-inscription 92

- 3.I.1. The Kōgenji Portrait 93

- 3.1.2. The Yabumoto Portrait 100

- 3.1.3. The Senbutsuji Portrait 105

- 3.1.4. The Hōunji Portrait 107

- 3.1.5. The Marui Portrait 109

- 3.1.6. Some Observations on the Spread of Zhongfeng 111

- Mingben's Image and Calligraphy

- 3.II. Inscriptions and Colophons to other Paintings 114

- 3.II. 1. Bodhidharma Crossing the Yangzi River 114

- 3.11.2 Guanyin Paintings 116

- 3.III. Sermons 119

- 3.III. 1. Sermon for Enkei Soyū 119

- 3.IV. Letters 120

- 3.IV.1. Letter to Shōkai Dōgen 120

- 3.IV.2. Subscription to Rebuild the Huanzhu Temple at Wumen 121

- 3.IV.3. Letter to Lord Otomo Sadamune 122

- 3.IV.4. Letter to Baoshi zhe 124

- 3.IV.5. Letter to Monk Sai 125

- 3.V. Sobriquets 127

- 3.V.1. Sobriquet for Huian 127

- Diamond Sutra by Zhao Mengfu with Colophon by Zhongfeng Mingben 128

- Developments in Zhongfeng Mingben's Calligraphy 130

- IV Conclusions

- 1. Zhongfeng Mingben's Pivotal Role between Literati and Chan Calligraphy 132

- 2. The Impact of Zhongfeng Mingben's Calligraphy in Japan 134

- Appendix

- Autobiography of Zhongfeng Mingben, Written when he was 60 Years old 138

- Bibliography 146.

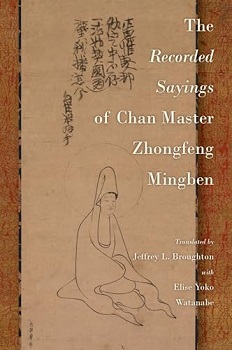

PDF: The Recorded Sayings of Chan Master Zhongfeng Mingben

by Jeffrey L. Broughton with Elise Yoko Watanabe

Oxford University Press, 2023

Contents

Abbreviations ix

Introduction 1

Linji Chan in the South During the Mongol Yuan Dynasty: Zhongfeng Mingben and Yuansou Xingduan 1

Autobiography and Huatou Chan 7

The Format and Underlying Theme of Zhongfeng’s Autobiography 10

The Confining Bureaucratic Chan Style of Mt. Tianmu Versus the Unencumbered Chan Style of a Vagabond Budai (布袋) 14

Two Chan Records for Zhongfeng Mingben: Zhongfeng Extensive Record and Zhongfeng Record B 17

Understanding the Phantasmal (zhi huan 知幻) 23

Detaching from the Phantasmal (li huan 離幻): The Huatou 27

Zhongfeng’s Great Matter of Samsara (shengsi dashi 生死大事) 30

Zhongfeng: “I Am Not Awakened” 32

Entanglement of Huatou Chan and Pure Land Nianfo (Nembutsu): Zhongfeng and Tianru 35

Zhongfeng and the “Nanzhao” (Yunnan) Pilgrim Xuanjian (玄鍳; d.u.) 38

Zhongfeng and Japanese Zen 43

Zhongfeng, Tianru, and Ming- Dynasty Linji Chan 55

Translation 1: Selections from Instructions to the Assembly in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 63

Translation 2: Selections from Dharma Talks in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 71

Translation 3: Night Conversations in a Mountain Hermitage in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 83

Translation 4: House Instructions for Dwelling- in- the- Phantasmal Hermitage in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 168

Translation 5: In Imitation of Hanshan’s Poems in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 179

Translation 6: Song of Dwelling- in- the- Phantasmal Hermitage in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 212

Translation 7: Cross- Legged Sitting Chan Admonitions (with Preface) in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 214

Translation 8: Ten Poems on Living on a Boat in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 216

Translation 9: Ten Poems on Living in Town in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 220

Translation 10: Selections from Zhongfeng Dharma Talks in Zhongfeng Record B 225

Translation 11: Instructions to the Assembly from Zhongfeng Talks in Zhongfeng Record B 245

Chinese Text for Translation 1: Selections from Instructions to the Assembly in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 247

Chinese Text for Translation 2: Selections from Dharma Talks in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 250

Chinese Text for Translation 3: Night Conversations in a Mountain Hermitage in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 254

Chinese Text for Translation 4: House Instructions for Dwelling-in-the-Phantasmal Hermitage in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 280

Chinese Text for Translation 5: In Imitation of Hanshan’s Poems in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 284

Chinese Text for Translation 6: Song of Dwelling- in- the- Phantasmal Hermitage in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 294

Chinese Text for Translation 7: Cross- Legged Sitting Chan Admonitions (with Preface) in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 295

Chinese Text for Translation 8: Ten Poems on Living on a Boat in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 296

Chinese Text for Translation 9: Ten Poems on Living in Town in Zhongfeng Extensive Record 298

Chinese Text for Translation 10: Selections from Zhongfeng Dharma Talks in Zhongfeng Record B 300

Chinese Text for Translation 11: Instructions to the Assembly from Zhongfeng Talks in Zhongfeng Record B 309

Bibliography 311

Index 315

PDF: The Definition of a Koan

by Chung-feng Ming-pen

Translated by Ruth Fuller Sasaki

In: Miura, Issho and Ruth Fuller Sasaki. Zen Dust: The History of the Koan and Koan Study in Rinzai (Lin-chi) Zen. Kyoto: The First Zen Institute of America, 1966.

Mingben's Portraits

By Inko and Injun (active mid-14th century),

dated 1353.

Wood with remains of pigment.

H. 82.5 cm.

Seiunji, Yamanashi Prefecture.

Important Cultural Property, Juy6 Bunkazai.

Zhongfeng Mingben was one of the most

important and influential masters of meditation.

In China as well as in Japan, he

was highly regarded not only in Zen circles,

but also among Emperors, scholars,

poets, and artists. Among his admirers

and closest friends were the celebrated

poet Feng Zizhen (1257-after 1327) and

the great painter, calligrapher, and Han/in

scholar Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322).The well-preserved portrait statue at

Seiunji, carved out of several blocks of

Japanese cypress, hinoki, is characterized

by the marked sculptural contrast between

the smooth, sensitively modelled

face with its bright inlaid rock-crystal eyes,

gyokugan kannyu, and the agitated, powerfully

molded folds of the garment. In

several aspects, the statue is a remarkable

work of Japanese sculpture: it is of

outstanding artistic quality, a striking portrait

of the important Chinese Chan master

with all his characteristic qualities; at

the same time, it is dated and signed;

moreover, it must have been carved after

painted portraits, sketches, or reliable

eyewitness reports, for the artists never

met their model in person. Finally, the portrait

is testament to the almost limitless,

enduring popularity and reverence enjoyed

by Zhongfeng Mingben among Japan's

medieval Zen circles.Most likely the sculpture was commissioned

by the Zen abbot Gōkai Honjō

(died 1352). Together with several other

Japanese pilgrim monks, among them

Enkei Soyū (1285-1344) and Mu'in Genkai

(before 1310-1358), Gōkai Honjō had

been in China from 1318 until 1326, where

he studied under Zhongfeng Mingben.

Emulating his revered meditation master,

in 1348 Gōkai Honjō built a monastery in a

secluded valley of the old province Kai on

a mountain that he named Tenmokuzan

(Chin. Tianmushan). He called his new

Zen institution "Monastery to Live in the

Clouds", Seiunji, expressing his wish to be

living undisturbed in solitary reclusion.

Perhaps, Gokai Honjo intended to consecrate

a portrait statue in his new residence

at the occasion of the thirtieth anniversary

of the great Chinese master's death,

which was also his ninetieth birthday, for

the sculpture was completed on the ninth

day of the fourth month in 1353.This information is given in a red inscription

inside the neck of the separately

carved head. The two sculptors are identified

by their ecclesiastical ranks and

names: Hokkyō, "Dharma Bridge", Injun

and Hōgen, "Dharma Eye", Inkō. The

statue is thus the joint work of the two

Buddhist sculptors or busshi, who are

also responsible for the Sakyamuni statue

at the same monastery. Other statues

extant by Inkō are an image of the

Bodhisattva Fugen dated to 1347 at

Hozoji in Tochigi Prefecture, and a Hōkan

Amida figure of 1349 at Zendōji in

Fukuoka.Gokai Honjō did not live to inaugurate the

Zhongfeng Mingben statue at Seiunji himself.

He died on the 27th day of the seventh

month of 1352, nine months prior to

the completion of the work. A portrait

sculpture at Seiunji also dated 1353 is a

memorial to the founding abbot. While still

alive, Gōkai Honjō probably supplied the

two Japanese sculptors with reliable

material concerning the famous Chinese

master of meditation, perhaps even a

chinzō he may have received from Mingben

himself. Otherwise, the artists could

hardly have known such details as

Mingben's missing small finger of his left

hand, burned off as a Buddha sacrifice.Zen - masters of meditation in images and writings

by Helmut Brinker [1939–2012]; Hiroshi Kanazawa [金沢 比呂司 1937-]

Museum Rietberg; Artibus Asiae, Zürich, 1996, p. 242.

Portrait of the Chinese Chan Master Zhongfeng Mingben (1263-1323) in Meditation under a Pine Tree

Anonymous. Inscription by Guangyan (14th century?).

Hanging scroll. Ink and light colours on silk.

123.5 x 51.2 cm.

Shôkoku-ji, Jishô-in, Kyoto

This portrait of Zhongfeng Mingben is

unsigned and without any seals of the

artist. It shows the corpulent Chan abbot

seated with crossed legs on a rock, the

hands in his lap in the "seal of meditation",

zenjo'in. Mingben's robe is wide open at

the chest, as in other portraits of him. The

rock is covered with a precious textile, and

his shoes are placed on a smaller rock in

front of him. The ground is uneven and

partly covered with grass. On the right

side, a magnificent pine tree and two

bamboo stalks lean over the master like a

canopy. It seems as if the Chinese Chan

master had selected and prepared an

ideal place for meditation in the calm of

nature.

An inscription in the upper right corner of

the scroll probably was added later by an

unidentified monk called Guangyan, one

of Mingben's numerous disciples:Old Huanweng [Zhongfeng Mingben] here loved pines and bamboo.

He received and maintained [Bodhidharma's tradition of] Shaolin[si].

To continue roughly his true school, no matter how far-reaching,

His heirs will have to shoulder responsibility.

[But] who knows [Mingiben Zhongfeng from Tianmu[shan]?

His follower Guangyan reverently [wrote] this eulogy.Evidently, this unorthodox open-air portrait

of Zhongfeng Mingben reminded

Guangyan of the great founding patriarch

Bodhidharma whose celebrated episode

of nine-year uninterrupted cliff contemplation

took place at Shaolinsi. The second

line of the poem mentions the monastery

on Mt. Song north of Dengfeng in presentday

Henan Province, founded in 496 by

Emperor Xiaowen (reigned 471-499) of

the Northern Wei Dynasty. A simple

shrine, Mianbi'an or "Facing-the-Wall Hermitage",

to the northwest of the monastery

preserves the memory of the origin of

Chan Buddhism in China.

The discrepancy in style between the figure

and the landscape seems to indicate

that two painters collaborated on the

composition. While the rocks and grasses,

the pine and the bamboo are painted with

vigour and fantasy, the somewhat stiff figure

- rendered with even "iron wire lines",

tiexian miao (Jap. tessenbyb) - is painted

in slavish adherence to the preliminary

drawing that is partially visible.

Such joint works, hezuo, were quite common

among literati circles of the Yuan

Dynasty. The pine tree and the bamboo in

this portrait bear a striking resemblance to

the style of Li Shixing (1283-1328) and,

even more so, of his father, Li Kan (1245-

1320). The latter was greatly admired by

Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322) as is vouched

for by his colophons and eulogies on Li's

bamboo paintings. On the other hand,

Zhao was a close friend of Zhongfeng

Mingben, as witnessed by six extant letters

of Zhao to Mingben dating to ca. 131 1.

Moreover, there exists in Taipei a copy by

the Qing Dynasty painter Pan Gongshou

(1741-1794) of a painting showing Mingben

as portrayed by Zhao Mengfu in 1309.

Most likely, this was not the only likeness

Zhao made of his abbot friend. It is thus

not far-fetched to suggest that such a

work or a sketch by Zhao Mengfu might

have served as the model for the portrait

at Jishb'in. The anonymous artist might

have faithfully copied his model, meticulously

clinging to every line. To some

degree this would also explain the stiffness

of the brushwork.

If one is to accept the collaboration of two

artists and perhaps even the active participation

of Zhao Mengfu and Li Kan, or

members of their circle, several questions

remain unanswered. Since Zhongfeng

Mingben survived both artists by a few

years, the painting must have been done

during his lifetime. In that case, however,

the sitter should - according to orthodox

rules of Chan portraiture - look toward the

right. But this highly unconventional Mingben

portrait was probably not intended to

be presented to a disciple confirming his

advanced stage of spiritual perception or

his legitimate place in the master's line of

succession. It was perhaps simply done

to demonstrate the Chan abbot's love for

nature. Mingben preferred to lead the life

of a religious recluse among bamboo,

rocks, and old trees, unhampered by the

organized hierarchy of his school in major

busy meditation centres. The portrait may

have been done for the abbot's or the

painters' own amusement. One may see it

as an enchanting, complex mirror image

of the character of an unconventional hermit

monk, maybe even as a token of close

friendship between congenial personalities

of the Yuan Dynasty.Zen - masters of meditation in images and writings

by Helmut Brinker [1939–2012]; Hiroshi Kanazawa [金沢 比呂司 1937-]

Museum Rietberg; Artibus Asiae, Zürich, 1996, p. 252.

Portrait of Zhongfeng Mingben 中峰明本像,

121.9cm × 54.4cm,

early 14th century 14 世 纪初,

Kyōto 京都, Senbutsu-ji Temple 選仏寺

Zhongfeng Mingben was the youngest of seven children of the Sun family in Qiantang in

today's Zhejiang Province.366H e is said to have been exceptionally serious-minded

157

already as a small boy, to have had a preference for the "lotus seat" position, to have

sung Buddhist hymns, and - to the astonishment of the neighbours - to have celebrated

Buddhist rituals as children's games. When Mingben was nine years old his mother died,

and the highly gifted child left school. Some years later he began to subject himself to

rigorous ascetic exercises in addition to the daily routine of a Buddhist lay follower, such

as the reciting of holy texts. Often he would climb Mt. Lingdong to meditate alone in the

seclusion of nature. Because he wanted to remain awake even at night during his spiritual

exercises at home, he kept walking around; when he felt drowsy, he would hit his

head on the pillars of the house.

At the age of fourteen, Mingben sacrificed - following shining examples of the past - a

part of his body to the Buddha by burning off the small finger of his left hand. Earlier the

second patriarch Huike had severed and sacrificed his arm, and the customs of "burning

off a finger", ranzhi, and of inflicting fire scars on the body, shaoba, especially on the

chest with sticks of incense, have been practiced by fervent Buddhist monks for centuries

to the present day.367 Self-mutilation and self-immolation were considered a higher

level of religious enthusiasm and devotion. There are frequent references in early

Buddhist texts to bodily sacrifices of the Tathagata himself. Stūpas and monasteries were

built to commemorate these noble deeds. The learned medieval Buddhist biographer

Zanning (919-1001) commented in his introduction to section 7 entitled "Discarding the

Body" of his Song gaoseng zhuan with the following verse on this concept of physical

self-destruction:To give away the thing that is difficult to part with,

Is the best offering among the alms.

Let this impure and sinful body,

Turn into something like a diamond.368

At about the age of twenty, Mingben met the severe master of meditation Gaofeng

Yuanmiao (1238-1295) who lived in the inaccessible "Death Pass", Siguan, on top of Mt.

Tianmu in modern Zhejiang Province. To his great surprise, the eminent prelate - reputed

to be highly dismissive - was immediately willing to accept him as novice. But Mingben's

father would not consent and the young man had to content himself with studying as a

lay brother under the Chan teacher for three years. In 1287, Mingben finally received tonsure

from Gaofeng Yuanmiao in the "lion's den", the Shizizhengzongsi, "Monastery of the

True School on the Lion's Rock", thanks to the support of the pious lady Yang Miaoxi who

donated the monk's robes and other paraphernalia. She became such an ardent admirer

of the young Chan monk that at home she worshiped some strands of Mingben's hair

shaved off at tonsure. After some time the hair allegedly produced lustrous five-coloured

?arira and these are said to have rapidly increased in number. Eleven years after

Mingben's death, in the winter of 1334, a stupa was built at the "Cloud Abode", the

Yunju'an near Hangzhou, to house the Chan master's miraculous hair together with the

venerated relics that had grown from it.Two years after receiving the tonsure, Zhongfeng Mingben had already attained enlightenment.

In order to celebrate and to certify this attainment Gaofeng Yuanmiao gave him

a portrait of himself with the following eulogy:My face is inconceivable,

Even Buddhas and patriarchs cannot have a glimpse,

I allow this no-good son alone

To have a peep at half of my nose.369Mingben remained in the monastery until 1295, serving in a number of various monastic

offices. But he felt increasingly constricted and limited by the obligations of monastic life.

When his master felt death approaching he asked Zhongfeng Mingben to assume the

leadership of the newly-erected "Monastery of the Great Enlightenment", Dajuesi, built on

"Lotus Blossom Peak", Lianhuafeng, of western Mt. Tianmu with the help of a wealthy

patron. Mingben, however, declined and suggested another disciple as successor. After

the funeral of his master, he left Tianmushan and began a free, restless life of roaming

about more suited to his eccentric, individualistic character and his craving for personal

independence. Mingben wanted to be a true mendicant. From 1298 onwards, he erected

a number of hermitages which he often called Huanzhu'an, "IllusoryA bode". Repeatedly,

he rejected honourable calls to direct renowned Chan institutions. In 1304, he settled

near the grave of his teacher Gaofeng Yuanmiao, and a year later, urged by the authorities

and his ever-increasing flock of disciples, Mingben accepted the abbacy of his old

home monastery on Mt. Tianmu. In 1309, he retired to a house boat in Yizhen, Jiangsu

Province. He was recalled to Tianmushan in the following year, but in 1311 he eschewed

all clerical obligations again and withdrew to a boat on Wujiang, a river flowing into the

"Great Lake", Taihu. Subsequently, he tried to live incognito in various places, avoiding

official summonings.Despite high courtly honours and titles, and despite a large number of devoted disciples

who kept tracking him down, shunning no difficulties or dangers in their efforts to receive

religious instruction from the master, Zhongfeng Mingben could not be persuaded to live

in a monastery for any extended time until an advanced age. Repeatedly, he spurned

prestigious appointments and even an audience with the Emperor. At the bottom of his

heart, he was an individualist and a hermit. Again and again, he vanished into small, idyllic

hermitages and returned only sporadically to his home monastery as well as to a

Huanzhu'an on western Mt. Tianmu built for him in 1317 by a lay adherent called Jiang

Jun. Not until the age of fifty-five did Mingben reconcile himself to the fact that he had to

take on the burden of an abbacy: in 1318, he started shaving his head again in accordance

with monastic custom (Fig. 113). This change of his outer appearance may also

have had something to do with the monastic behaviourc odex Huanzhuq ingguit, he

"PureR ules fromt he Huanzhu[an]w" rittend own in the previousy ear and meant not so

much as generally binding order rules, but rather as a practical manual for his own circle

of disciples. He died in 1323 at the relatively early age of sixty.

In his doctrine and the practical education of his disciples, Zhongfeng Mingben emphasized

the central significance of the huatou (Jap. watō), the concentration on the "word

head", the critical phrase and essential core of a gong'an or kdan. For Zen practitioners

in his line gong'an as regular part of instruction came to represent the true essence of

meditative vocation. The master himself called gong'an a "senseless and tasteless

phrase", wuyiwei huatou, which was made up to stop the adept's excessive intellectual

approach and to artificiallyc reate the "great doubt", dayi. He left behind a number of sermons,

individual didactic sayings, commentaries to Buddhist texts, essays, poems, letters,

and painting inscriptions compiled by a disciple in the Zhongfeng Heshang guanglu

as well as a three-part supplementary volume.Zen - masters of meditation in images and writings

by Helmut Brinker [1939–2012]; Hiroshi Kanazawa [金沢 比呂司 1937-]

Museum Rietberg; Artibus Asiae, Zürich, 1996, pp. 157-159.

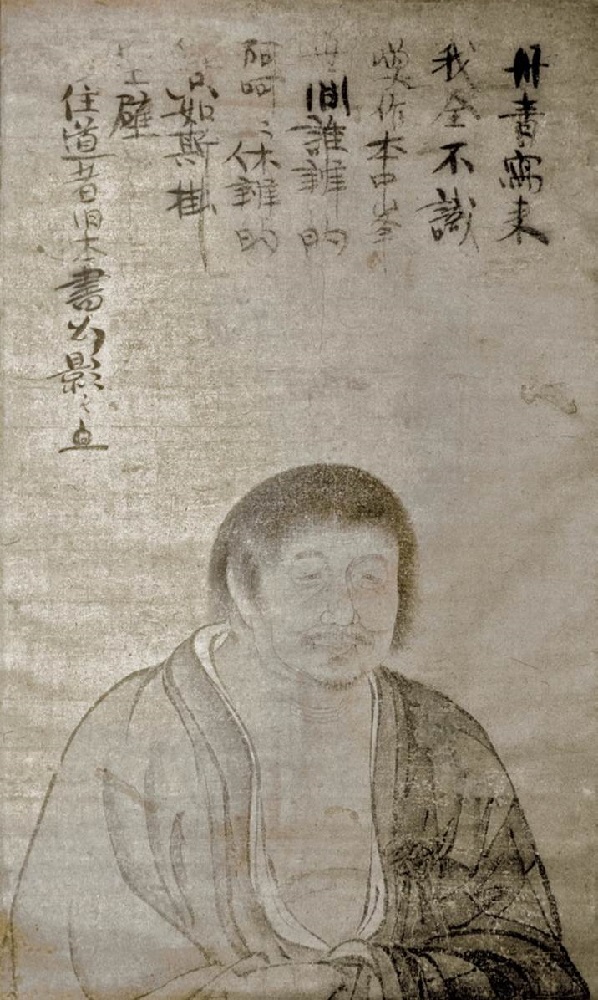

Portrait of the Chinese Chan Master Zhongfeng Mingben (1263-1323)

Anonymous. Inscription by Zhongfeng Mingben.

Hanging scroll. Ink and colours on silk.

125.2 x 51.9 cm.

Senbutsuji, Kyoto.

Important Cultural Property, Jūyō Bunkazai.

Many literary sources and extant portraits

characterize Zhongfeng Mingben as a

highly unconventional, original personality.

Among Japanese pilgrim monks he was

one of the most popular Zen teachers and

a number of his portraits made their way

to Japan as early as the beginning of the

fourteenth century. Thus, the Zen monk

Enkei Soyū (1285-1344) returned to

Japan in 1315 from a nine-year stay in

China, bringing with him an image of his

master signed by the otherwise unknown

portraitist Yi'an. In 1325, Enkei built the

Kōgenji in his native province of Tanba,

and the monastery still owns the magnificent

portrait of the important Chan master.

The main difference between the early

and later portraits of the master is that in

the former he is not shown with a shaven

head. His dark hair hangs into his forehead,

over the ears, and down his short

neck. He seems to have adopted this

unconventional and not very clerical haircut

from his master Gaofeng Yuanmiao

(1238-1295). Only from 1318 on, when

Zhongfeng Mingben gave up his role as

itinerant hermit-monk and accepted the

honourable post of a Chan abbot, did he

shave his head in accordance with the

order's rules.This is how Zhongfeng Mingben is shown

in the portrait at Senbutsuji in Kyōto. As it

is inscribed by the portrayed abbot, it

probably dates to between 1318 and

1323. In its composition with the master

turned slightly to the right, the painting is

in accordance with the conventional type

of Zen portrait painted during the lifetime

of the prelate. In such images, the master

appears in the dignified regalia of his office,

seated in the abbot's chair, yizixiang

(Jap. isuz6), "image in the chair". The corpulent

abbot is seated with crossed legs

in meditation pose, his robe falling down

over his knees. In front of the chair, his

shoes are standing on a footstool with

short, ornamented feet. His brown monk's

robe hangs loosely around his round

shoulders, comfortably open from the

chest to his stomach. At the seam of the

collar and the sleeves, a white under-garment

is visible. A black ring over Mingben's

heart, fastened with a white cord

over the shoulders, holds his stole, kesa.

On the left, a long priest's staff, bang (Jap.

bō), with red ends leans against the ornamental

cloth covering the back rest of the

abbot's chair. In his hands, the abbot

holds a whisk, fuzi (Jap. hossu), another

symbol of his rank as abbot. Originallyt, he

fly whisk was intended to chase away

molesting insects during meditation; metaphorically,

however, it came to signify the

sweeping away of all doubts, worldly

thoughts, and desires; the symbol for

purity of heart, for the removing of "dust

from the mirror of the mind", as the patriarchs

put it. At his left hand, the mutilated

little finger is clearly visible: as young, passionate

follower of the Buddhist creed, he

had burned it off, to present it as a sacrifice

to Buddha. Zhongfeng Mingben's

round, full face with the small, narrow eyes

emanates benevolent understanding, his

overall posture composed authority.The linear vocabulary of this portrait, typical

of one aspect of figure painting during

the Yuan Dynasty, is fundamentally different

from the modulated, swelling and

ebbing calligraphic line of the Song Dynasty.

The evenly flowing, thin "iron wire

lines", tiexian miao (Jap. tessenbyō), of the

garment are partly accompanied by light

shadings adding modulation to the folds.The inscription by Zhongfeng Mingben is

partly illegible due to fire damage, and it is

not to be found in his "Recorded Sayings".

The date and the recipient of the portrait

are therefore not known. However, some

conjectures can be made. Originally, the

scroll was at Genjū'an of Nanzenji in

Kyoto, where Mu'in Genkai (before 1310-

1358), a former disciple of the portrayed

abbot, was appointed 21 st abbot in 1349.

In 1326, three years after the death of his

master on Mt. Tianmu near Hangzhou,

Mu'in Genkai had returned to Japan,

together with a group of monks among

whom was Qingzhuo Zhengcheng (1274-

1339). Therefore it is not impossible that

Mu'in Genkai, the future Nanzenji abbot,

carried the portrait of Zhongfeng Mingben

in his luggage.A document accompanying of the work

explains why the scroll had to be newly

mounted in 1538: the scroll had been

stored in the library of Nanzenji, where

there had been a fire shortly before 1538.

On the day after the accident, a monk had

found the rolled-up scroll in the ashes.

Miraculously, only the outer layers of the

scroll, i.e., the inscription in the upper,

"outer" part, were damaged; the lower,

"inner" parts, however, with the actual

portrait, were left undamaged.Zen - masters of meditation in images and writings

by Helmut Brinker [1939–2012]; Hiroshi Kanazawa [金沢 比呂司 1937-]

Museum Rietberg; Artibus Asiae, Zürich, 1996, p. 250.

![]()

Ming-pen

In:

Buddha tudat, Zen buddhista tanítások. Ford., szerk. és vál. Szigeti György, Budapest, Farkas Lőrinc Imre Könyvkiadó, 1999, 103. oldal

Démonok birodalma

A zen a tudat tiszta földjének tanítása. Ha meg akarod

érteni az élet-halálról szóló mély értelmű tanítást, ak-

kor be kell látnod, hogy a kétség vagy a zavarodottság

egyetlen gondolata nyomban a démonok birodalmába

taszít téged.

Csak higgy magadban!

Csak higgy magadban!

A tudat valójában tiszta

A tudat valójában tiszta és nyugodt, alapvetően rnen-

tes minden szennyeződéstől.

Meditáció

Ha meditációd közben gondolatok kavarognak a fejed-

ben, és az elképzeléseid összezavarnak, akkor ne foglal-

kozz velük egyáltalán, függedenül attól, hogy azok jók

vagy rosszak, igazak vagy hamisak.