ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

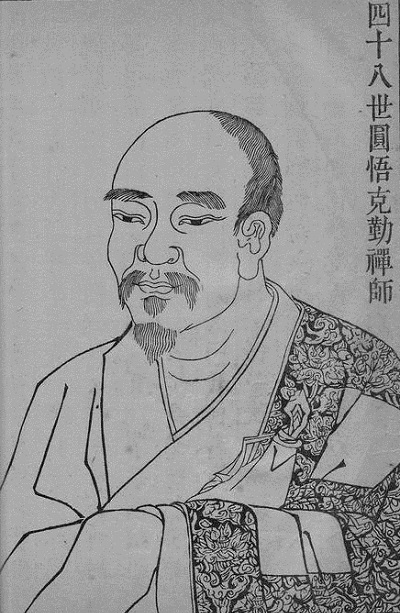

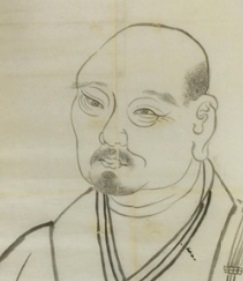

圜悟克勤 Yuanwu Keqin (1063–1135), aka 佛果克勤

Foguo Keqin

(Rōmaji:) Engo Kokugon, aka Bukka Kokugon

佛果克勤禪師心要 Foguo Keqin chanshi xinyao

(English:) Essentials of Chan Master Foguo Keqin / Chan master Foguo Keqin's essentials of mind / Essentials of Mind of [Yuanwu] Foguo Keqin

(XZJ. 120.744.18–745a1)

雪竇重顯 Xuedou Chongxian (980–1052) & 圜悟克勤 Yuanwu Keqin (1063–1135)

碧巖錄 / 碧岩錄 Biyan lu

(Rōmaji:) Setchō Jūken & Engo Kokugon: Hekigan-roku

(English:) The Blue Cliff Record / Emerald Cliff Record / Nephrite Rock Writings

(Magyar:) Hszüe-tou Csung-hszien & Jüan-vu Ko-csin: Pi-jen lu /

Kék szikla gyűjtemény / Nefrit szirt feljegyzések / A zöldkőszáli feljegyzések

Xuedou baize songgu 雪竇百則頌古 (the original version of the Biyan lu 碧巖録).

Biyan lu 碧巖錄 (The blue cliff record), 10 fascicles (t 48: #2003). Full title Foguo Yuanwu Keqin Chanshi biyan lu 佛果圜悟克勤禪師碧巖錄 . The work, one of the most important koan collections in the Linji school of Chan, was compiled by Puzhao 普照 (n.d.), edited by Guan Wudang 關無黨 (n. d.), and published in 1128. The work is based on a series of lectures delivered between 1111 and 1117 at the temple Lingquan yuan 靈泉院 on Mount Jia 夾 by the Chan master Yuanwu Keqin 圜悟克勤 (1063–1135). The subject of the lectures was the Xuedou baize songgu 雪竇百則頌古 , a collection of one hundred koans selected and commented upon by Xuedou Chongxian 雪竇 重顯 (980–1052). Each of the one hundred cases in the Biyan lu consists of a chuishi 垂示 (a short introduction by Yuanwu), benze 本則 (the original koan text interspersed with Yuanwu's terse remarks), pingchang 評唱 (a full commentary on the koan by Yuanwu), song 頌 (Xuedou's verse comments interspersed with Yuanwu's terse remarks), and another pingchang 評唱 (a full commentary by Yuanwu on Xuedou's verse comments). Aft er Yuanwu's death his disciple Dahui Zonggao 大慧宗杲 (1089–1163), believing that the text constituted a hindrance to true Chan practice, ordered it burned, and it was not reissued until 1317.

雪竇重顯 Xuedou Chongxian (980–1052) & 圜悟克勤 Yuanwu Keqin (1063–1135)

撃節録 Jijie lu

(Rōmaji:) Setchō Jūken & Engo Kokugon: Gekisetsu-roku

(English:) The Measuring Tap (Essentials of Chan Master Foguo Keqin)

(Magyar:) Hszüe-tou Csung-hszien & Jüan-vu Ko-csin: Csi-csie lu / Ütemzés

Xuedou baize niangu 雪竇百則拈古 (the original version of the Jijie lu 撃節録).

The Yuanwu-lu (Engo-roku), or the Jijie-lu (Gekisetsu-roku), Yuanwu's comments on Xuedou's Niangu, a collection of one-hundred verses (other than the Biyan-lu); Yuanwu referred to his comments as "keeping the beat" (jijie) in harmony with the rhythm of Xuedou's collection, so as to show his appreciation of those verses.

DOC: The Measuring Tap: a Chan Buddhist Classic

Translated by Thomas Cleary

Yuanwu Keqin 圜悟克勤 (1063–1135) was born in Pengzhou 彭州 in present Sichuan; his family name was Luo 駱. It is said that as a child he could memorize a thousand-character passage in a single day. He became a monk in his early teens after reading Buddhist texts at a temple and feeling a sudden affinity with the teachings. After studying the precepts and scriptures he suffered a grave illness, thus realizing the futility of attempting to resolve samsara through words. He visited several masters and was praised everywhere as a great vessel of the dharma. He finally came to Wuzu Fayan 五祖 法演 (1024?–1104) of the Yangqi line of Linji Chan. When Fayan refused to sanction his understanding Yuanwu left in anger, upon which Fayan called after him, “Remember me when you are ill with fever!” Soon afterwards, at the monastery on Mount Jin 金, he did, in fact, become gravely ill, and, upon recovery, returned to study under Fayan. After years of training he became Fayan's heir. In 1102, owing to the illness of his mother, he returned to Sichuan. There he assumed the abbacy of the temple Zhaojue si 昭覺寺 at the invitation of the prefect of Chengdu 成都. After eight years he was asked to become priest of Lingquan yuan 靈泉院 on Mount Jia 夾, and it was there that he gave his famous lectures on the Xuedou baize songgu 雪竇百則頌古, a collection of verse commentaries on koans by Xuedou Chongxian 雪竇重顯 (980–1052) of the Yunmen school. Yuanwu's lectures were later published as the Biyan lu 碧巖錄 (Blue cliff record), which became one of the most important texts for Linji school koan study. Yuanwu was very successful as a teacher, numbering among his students not only monks but also lay practicers, some of them high government officials. He was granted the title Chan Master Foguo 佛果禪師 by Emperor Huizong 徽宗 (r. 1100–1125), and by imperial command resided at several temples in the north and (following relocation of the capital to the city of Hangzhou in 1127) in the south. The title Chan Master Yuanwu 圜悟禪師, by which he has been generally known ever since, was conferred upon him by Emperor Gaozong 高宗 (r. 1127–1162). In 1130 Yuanwu returned to the temple Zhaojue si, and there, in 1135, died in the sitting posture after writing his farewell poem. The two most important of his sixteen dharma heirs were Dahui Zonggao and Huqiu Shaolong 虎丘紹隆 (1077–1136), whose line includes all Japanese Rinzai Zen masters.

Foguo Keqin Chanshi xinyao 佛果克勤禪師心要 (Essentials of Chan Master Foguo Keqin), 2 fascicles (x 69: #1357). Also known as Foguo Yuanwu Zhenjue Chanshi xinyao 佛果圜悟眞覺禪師心要 and Yuanwu Chanshi xinyao 圜 悟禪師心要. A collection of 140 short writings by the Chan master Yuanwu Keqin 圜悟克勤 (1063–1135) on the essentials of Chan, addressed to the master's lay and ordained disciples.

Yuanwu Foguo Chanshi yulu 圜悟佛果禪師語録 (Recorded sayings of Chan Master Yuanwu Foguo), 20 fascicles (t 47: #1997). Often referred to as the Foguo Yuanwu Chanshi yulu 佛果圜悟禪師語録, Yuanwu Chanshi yulu 圜悟禪師語録, or Yuanwu lu 圜悟録, the work is a compendium of the sermons, informal talks, verse, and prose of Yuanwu Keqin 圜悟克勤 (1063–1135), compiled by the master's foremost disciple, Huqiu Shaolong 虎丘紹隆 (1077–1136). It was first published in 1134, with prefaces by the government officials Geng Yanxi 耿延禧 (n.d.) and Zhang Jun 張浚 (1086–1154), both lay disciples of the master. The record contains formal sermons from the high seat 上堂 (fascicles 1–8); informal discourses 小参 (fascicles 8–13); public lectures for lay believers 普説 (fascicle 13); informal talks on practice 法語 (fascicles 14–16); prose comments on koans 拈古 (fascicles 16–18); verse comments on koans 頌古 (fascicles 18–19); and miscellaneous verses and prose writings (fascicle 20).

PDF: Yuan-wu K'o-ch'in's (1063-1135) Teaching of Ch'an Kung-an Practice:

A Transition from the Literary Study of Ch'an Kung-an to the Practical K'an-hua Ch'an

by Ding-hwa Evelyn Hsieh

Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Vol. 17. No. 1. 1994. pp. 66-95.

A Study of the Evolution of K'an-Hua Ch 'an in Sung China: Yuan-Wu K'o-Ch 'in and the Function of Kung-an in Ch 'an Pedagogy and Praxis'

by Hsieh, Ding-hwa Evelyn (1961-)

Dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 1993. 532 p.

https://philpapers.org/rec/HSIASOThe dissertation involves a study of the evolution of a meditation technique unique to Ch'an – k'an-hua Ch'an of the kung-an – as practiced in the Chinese Lin-chi school during the Sung period. By focusing on the life and thought of the Lin-chi Ch'an master Yuan-wu K'o-ch'in, I wish to provide a clearer idea of how Sung Lin-chi monks reconciled the dichotomy between Ch'an's rhetoric and meditative praxis in regard to kung-an practice.

① Chapter one of this dissertation is an introduction to why I believe this research to be important and a survey of previous scholarly views on the kung-an.

② Chapter two is a survey of Yuan-wu's life; references are drawn from various Buddhist biographical sources collected in the Taisho shinshu daizokyo and the Hsu-tsang ching, and also some non-Buddhist materials as well. Detailed information about Yuan-wu's works will also be provided there.

③ Chapter three deals with the ontology that Yuan-wu adopted to support his soteriological system. My attempt there is mainly to elucidate Yuan-wu's viewpoints toward the relationship between cultivation and enlightenment in the context of the larger Ch'an tradition, and to understand how Yuan-wu tried hard to support the idea of subitism in Ch'an praxis while repairing some soteriological deficiencies in that idea as perceived by people within and outside Ch'an.

④ Chapter four is an analysis of Yuan-wu's kung-an anthology, the Pi-yen lu. The purpose of this chapter is to explore Yuan-wu's motives for producing this kung-an text and his response to the internalcrisis engendered by the so-called wen-tzu Ch'an movement of his time.

⑤ Chapter five focuses on Yuan-wu's approach to kung-an investigation. Through examining Yuan-wu's sayings and writings, I will demonstrate that Yuan-wu played a crucial transitional role in the evolution from wen-tzu Ch'an to k'an-hua Ch'an.

⑥ Chapter six is a summary of the development of Sung k'an-hua Ch'an, which, I suggest, may be classified as "literati Buddhism," since its target lay audience was members of the Sung literati and its motives were mainly to accommodate and respond to that social and intellectual class. Thus a study of Yuan-wu's instructions on kung-an investigation and his teachings on Ch'an cultivation may further yield vital information about the mutual influence between Ch'an Buddhism and Sung Confucianism.

PDF: Unintended Baggage? Rethinking Yuanwu Keqin's View of the Role of Language in Chan Gongan Discourse

by

Steven Heine

Frontiers in History of China 8/3 (2013): 316–341.

圜悟 Yuanwu painted by 奥大節 Daisetsu Oku (1888-1970)

PDF: Zen Letters: Teachings of Yuanwu

Translated by J.C. Cleary & Thomas Cleary

Shambhala, 1994, 120 p.

Zen Letters presents the teachings of the great Chinese master Yuanwu (1063–1135) in direct person-to-person lessons, intimately revealing the inner workings of the psychology of enlightenment. These teachings are drawn from letters written by Yuanwu to various fellow teachers, disciples, and lay students—to women as well as men, to people with families and worldly careers as well as monks and nuns, to advanced adepts as well as beginning students.

Excerpted from the Letters of Yuanwu:

A Lotus in Fire

I wouldn't say that those in recent times who study the Way do not try hard, but often they just memorize Zen stories and try to pass judgment on the ancient and modern Zen masters, picking and choosing among words and phrases, creating complicated rationalizations and learning stale slogans. When will they ever be done with this? If you study Zen like this, all you will get is a collection of worn-out antiques and curios.

When you “seek the source and investigate the fundamental” in this fashion, after all you are just climbing up the pole of your own intellect and imagination. If you don't encounter an adept, if you don't have indomitable will yourself, if you have never stepped back into yourself and worked on your spirit; if you have not cast off all your former and subsequent knowledge and views of surpassing wonder, if you have not directly gotten free of all this and comprehended the causal conditions of the fundamental great matter, then that is why you are still only halfway there and are falling behind and cannot distinguish or understand clearly. If you just go on like this, then even if you struggle diligently all your life, you still won't see the fundamental source even in a dream.

This is why the man of old said, “Enlightenment is apart from verbal explanations—there has never been any attainer.”

Deshan said, “Our school has no verbal expressions and not a single thing or teaching to give to people.”

Zhaozhou said: “I don't like to hear the word buddha.”

Look at how, in verbally disavowing verbal explanations, they had already scattered dirt and messed people up. If you go on looking for mysteries and marvels in the Zen masters' blows and shouts and facial gestures and glaring looks and physical movements, you will fall even further into the wild foxes' den.

All that is important in this school is that enlightenment be clear and thorough, like the silver mountain and the iron wall, towering up solitary and steep, many miles high. Since this realization is as sudden as sparks and lightning, whether or not you try to figure it out, you immediately fall into a pit. That is why since time immemorial the adepts have guarded this one revelation, and all arrived together at the same realization.

Here, there is nowhere for you to take hold. Once you can clear up your mind, and you are able to abandon all entanglements, and you are cultivating practice relying on an enlightened spiritual friend, it would be really too bad if you weren't patient enough to get to the level where the countless difficulties cannot get near you, and to lay down your body and your mind there and investigate till you penetrate through all the way.

Over thousands of lifetimes and hundreds of eons up until now, has there ever been any discontinuity in the fundamental reality or not? Since there has been no discontinuity, what birth and death and going and coming is there for you to be in doubt about? Obviously these things belong to the province of causal conditions and have absolutely no connection to the fundamental matter.

My teacher Wuzu often said: “I have been here for five decades, and I have seen thousands and thousands of Zen followers come up to the corner of my meditation seat. They were all just seeking to become buddhas and to expound Buddhism. I have never seen a single genuine wearer of the patched robe.”

How true this is! As we observe the present time, even those who expound Buddhism are hard to find—much less any genuine people. The age is in decline and the sages are further and further distant. In the whole great land of China, the lineage of Buddha is dying out right before our eyes. We may find one person or half a person who is putting the Dharma into practice, but we would not dare to expect them to be like the great exemplars of enlightenment, the “dragons and elephants” of yore.

Nevertheless, if you simply know the procedures and aims of practical application of the Dharma and carry on correctly from beginning to end, you are already producing a lotus from within the fire.

You must put aside all the conditioning that entangles you. Then you will be able to perceive the inner content of the great enlightenment that has come down since ancient times. Be at rest wherever you are, and carry on the secret, closely continuous, intimate-level practice. The devas will have no road to strew flowers on, and demons and outsiders will not be able to find your tracks. This is what it means to truly leave home and thoroughly understand oneself.

If, after you have reached this level, circumstances arise as the result of merit that lead you to come forth and extend a hand to communicate enlightenment to others, this would not be appropriate. As Buddha said, “Just acquiesce in the truth; you surely won't be deceived.”

But even for me to speak this way is another case of a man from bandit-land seeing off a thief.

Kindling the Inexhaustible Lamp

By even speaking a phrase to you, I have already doused you with dirty water. It would be even worse for me to put a twinkle in my eye and raise my eyebrow to you, or rap a meditation seat or hold up a whisk, or demand, "What is this?" As for shouting and hitting, it's obvious that this is just a pile of bones on level ground.

There are also the type who don't know good from bad and ask questions about Buddha and Dharma and Zen and the Tao. They ask to be helped, they beg to be received, they seek knowledge and sayings and theories relating to the Buddhist teaching and to transcending the world and to accommodating the world. This is washing dirt in mud and washing mud in dirt - when will they ever manage to clear it away?

Some people hear this kind of talk and jump to conclusions, claiming, "I understand!" Fundamentally there is nothing to Buddhism - it's there in everybody. As I spend my days eating food and wearing clothes, has there ever been anything lacking?" Then they settle down in the realm of unconcerned ordinariness, far from realizing that nothing like this has ever been part of the real practice of Buddhism.

Leaving behind all leakages, day by day you get closer to the truth and more familiar with it. As you go further, you change like a panther who no longer sticks to its den - you leap out of the corral. Then you no longer doubt all the sayings of the world's enlightened teachers - you are like cast iron. This is precisely the time to apply effort and cultivate practice and nourish your realization.

After that you can kindle the inexhaustible Lamp and travel the unobstructed Path. You relinquish your body and your life to rescue living beings. You enable them to come out of their cages and eliminate their attachments and bonds. You cure them of the diseases of being attached to being enlightened, so that having emerged from the deep pit of liberation, they can become uncontrived, unencumbered, joyfully alive people of the Path.

So then, when you yourself have crossed over, you must not abandon the carrying out of your bodhisattva vows. Be mindful of saving all beings and steadfastly endure the attendant hardship and toil in order to serve as a boat on the ocean of all-knowledge. Only then will you have some accord with the Path.

Don't be a brittle pillar or a feeble lamp. Don't bat around your little clean ball of inner mystical experience. You may have understood for yourself, but what good does it do? Therefore the ancient worthies necessarily urged people to travel the one road of the bodhisattva path so they would be able to requite the unrequitable benevolence of our enlightened predecessors who communicated the Dharma to the world.

Nowadays there are many bright Zen monks in various locales who want to pass through directly. Some seek too much and want to understand easily. As soon as they know a little bit about the aim of the Path and how to proceed they immediately want to show themselves as adepts, yet they have already missed it and gone wrong. Some don't come forth even when they are pushed to do so, but they too are not yet completely enlightened.

You are a master of Buddhist teaching methods only when you can recognize junctures of times and patterns of causal conditions and manage not to miss real teaching opportunities.

"If where you stand is reality, then your actions have power."

Ever since antiquity, with excellence beyond measure, the saints and sages have experienced this Great Cause alone, as if planting great potential and capacity. Without setting up stages, they abruptly transcend to realize this essence alone. Since before the time when nothing existed, this essence has been ever still and unmoved, determining the basis of all conscious beings. It permeates all times and is beyond all thought. It is beyond holy and ordinary and transcends all knowledge and views. It has never fluctuated or wavered: it is there, pure and naked and full of life. All beings, both animate and inanimate, have it complete within them.

If you can turn fast on top of things, everything will be in your grasp. Capturing and releasing, rolling up and rolling out-all can be transformed. At all times remain peaceful and tranquil, without having anything whatsoever hanging on your mind. In action you accord with the situation and its potential, holding the means of discernment within yourself. Shifting and changing and successfully adapting, you attain Great Freedom - all things and all circumstances open up before your blade, like bamboo splitting, all "bending down with the wind."

Therefore, if where you stand is reality, then your actions have power. Turning the topmost key, achieving something that cannot be taken away in ten thousand generations, you see and hear the same way as the ancient buddhasand share the same knowledge and functioning.

Move with a Mighty Flow

When your vision penetrates through and your use of it is clear, you are spontaneously able to turn without freezing up or getting stuck amid all kinds of lightning-fast changes and complex interactions and interlocking intricacies. You do not establish any views or keep to any mental states; you move with a mighty flow, so that "when the wind moves, the grasses bend down."

When you enter into enlightenment right where you are, you penetrate to the profoundest source. You cultivate this realization till you attain freedom of mind, harboring nothing in your heart. Here there is no "understanding" to be found, much less "not understanding."

You go on like this twenty-four hours a day, unfettered, free from all bonds. Since from the first you do not keep to subject and object or self and others, how could there be any "buddhadharma?" This is the realm of no mind, no contrived activity, and no concerns. How can this be judged with mere worldly intelligence and knowledge and discrimination and learning, if the fundamental basis is lacking?

Did Bodhidharma actually bring this teaching when he came from the West? All he did was to point out the true nature that each and every person inherently possesses, to enable people to thoroughly emerge clear and pure from the orbit of delusion and not be stained and defiled by all their erroneous knowledge, consciousness, false thoughts, and judgments.

"Study must be true study." When you find a genuine teacher of the Way, they will not lead you into a den of weeds; they will cut through directly so you can meet with realization. You will be stripped of the sweaty shirt (of the ego) that is clinging to your flesh so your heart is enabled to become empty and open, without the slightest sense of ordinary and holy, and without any external seeking, so that you become profoundly clear and still, genuine, and true.

Then even the thousand sages cannot place you. You attain a state that is unified and pure and naked, and pass through to the other side of the empty room. There even the Primordial Buddha is your descendant, so how could you seek any more from others?

Ever since the ancestral teachers, all the true adepts have been like this. Take the example of the Sixth Patriarch. He was a man from a frontier area in the south who sold firewood for a living, an illiterate. When he met the Fifth Patriarch face to face, he opened his heart and openly passed through to freedom.

The saints and sages live mixed in among the ordinary people, but even so, it is necessary to use appropriate means to reveal this matter that makes no separation between the worthy and the ignorant and is already inherent in all people.

Once you merge your tracks into the stream of Zen, you spend your days silencing your mind and studying with your whole being. You realize that this Great Cause is not obtained from anyone else but is just a matter of taking up the task boldly and strongly, and making constant progress. Day by day you shed your delusions, and day by day you enhance your clarity of mind.

Your potential for enlightened perception is like fine gold that is to be refined hundreds and thousands of times. What is essential for getting out of the dusts, what is basic for helping living creatures, is that you must penetrate through freely in all directions and arrive at peace and security free from doubt and attain the stage of great potential and great function.

This work is located precisely in your own inner actions. It is just a matter of being in the midst of the interplay of the myriad causal conditions every day, in the confusion of the red dusts, amid favorable and adverse circumstances and gain and loss, appearing and disappearing in their midst, without being affected and "turned around" by them, but on the contrary, being able to transform them and "turn them around."

When you are leaping with life and water cannot wet you, this is your own measure of power. You reach an empty, solidified silence, but there is no duality between emptiness and form or silence and noise. You equalize all sorts of wondrous sayings and perilous devices and absolute perceptions; ultimately there is no gain or loss, and it is all your own to use.

When you go on "grinding and polishing" like this for a long time, you are liberated right in the midst of birth and death, and you look upon the world's useless reputation and ruinous profit as mere dust in the wind, as a dream, as a magical apparition, as an optical illusion. Set free, you pass through the world. Isn't this what it means to be a great saint who has emerged from the dusts of sensory attachments?

A Boatload of Moonlight

The early sages lived with utmost frugality, and the ancient worthies overcame hardships and lived austerely. They purified their will in this, forgetting food and sleep. They studied with total concentration and accurate focus, seeking true realization. How could they have been making plans for abundant food and fine clothes and luxurious housing and fancy medicines?

When it gets to the point where the path is not as good as in ancient times, then there is criticism that the wheel of the Dharma is not turning, and that the wheel of food is taking precedence. Because of this the Zen monasteries call their chief elders "meal-chiefs." Isn't this completely opposite from the ancient way?

Nevertheless, in the gate of changing along with conditions, we also carry out the secondary level. "On the northern mountain welcoming wayfarers from all directions, we look to the southern fields."

This fall it happens that there is a big crop. We have asked you to oversee the harvest, and now that you are about to go, you have asked for some words of instruction, so I have told you about the foregoing set of circumstances.

What is important is to respect the root and extend it to the branches. This will benefit both root and branches and also illuminate the legitimate and fundamental task of people of complete enlightenment and comprehensive mastery. If you work hard to carry this out, you will surely improve.

In general, to study the Path and seek out the Mystery, you must have a great basis in faith. You use this faith to believe in a deep sense that this matter does not lie in words or in any of the myriad experimental states. In fact, in truth, the Path is right where you stand.

Put aside the crazy and false mind that has been concocting your knowledge and understanding, and make it so that nothing whatsoever is weighing on your mind. Fully take up this matter in your perfect, wondrous, inherent nature, which is fundamentally pure and quiescent. Subject and object are both forgotten, and the road of words and thoughts is cut off. You open through and clearly see your original face. Make it so that once found, it is found forever and remains solid and unmoving.

After that you can change your step and transform your personal existence. You can say things and put forth energy without falling into the realms of delusion of form, sensation, conception, evaluation, and consciousness. Then all the phenomena of enlightenment will appear before you in regular array. You will reach the state where everything you do while walking and sitting is all Zen. You will shed the root of birth and death and forever leave behind all that covers and binds you. You will become a free and untrammeled wayfarer without concerns—why would you need to search the pages for someone else's dead words?

"There are ancestral teachers on the tips of the hundred grasses." With these words Jiashan pointed it out so people could become acquainted with it.

Kuanping said, "The great meaning is there in the fields."

Baizhang extended his hands, wanting to let people know.

If you can become round and complete as a ripe grain of rice, this is the transmission of the mind-seal. If you still long for a peaceful existence, this will make you experience the first noble truth that suffering exists. But how will you say something about coming out of the weeds?

"A boatload of bright moonlight carries it back."

Hidden Treasure

Brave-spirited wearers of the patched robe possess an outstanding extraordinary aspect. With great determination they give up conventional society. They look upon worldly status and evanescent fame as dust in the wind, as clouds floating by, as echoes in a valley.

Since they already have great faculties and great capacity from the past, they know that this level exists, and they transcend birth and death and move beyond holy and ordinary. This is the indestructible true essence that all the enlightened ones of all times witness, the wondrous mind that alone the generations of enlightened teachers have communicated.

To tread this unique path, to be a fragrant elephant or a giant, golden-winged bird, it is necessary to charge past the millions of categories and types and fly above them, to cut off the flow and brush against the heavens. How could the enlightened willingly be petty creatures, confined within distinctions of high and low and victory and defeat, trying futilely to make comparative judgments of instantaneous experience, and being utterly turned around by gain and loss?

For this reason, in olden times the people of great enlightenment did not pay attention to trivial matters and did not aspire to the shallow and easily accessible. They aroused their determination to transcend the buddhas and patriarchs. They wanted to bear the heavy responsibility that no one can fully take up, to rescue all living beings, to remove suffering and bring peace, to smash the ignorance and blindness that obstructs the Way. They wanted to break the poisoned arrows of ignorant folly and extract the thorns of arbitrary views from the eye of reality. They wanted to make the scenery of the fundamental ground clear and reveal the original face before the empty eon.

You should train your mind and value actual practice wholeheartedly, exerting all your power, not shrinking from the cold or heat. Go to the spot where you meditate; quiet your mental monkey and pacify your intellectual horse. Make yourself like a dead tree, like a withered stump.

Suddenly you penetrate through; how could it be attained from anyone else? You discover the hidden treasure, you light the lamp in the dark room, launch the boat across the center of the ford. You experience great liberation, and without producing a single thought, you immediately attain true awakening. Having passed through the gate into the inner truth, you ascend to the site of universal light. Then you sit in the impeccably pure supreme seat of the emptiness of all things.

But this is not yet the stage of effortless achievement. You must go further beyond, to where the thousand sages cannot trap you, the myriad conscious beings have no way to look up to you, the gods have no way to offer you flowers, and the demons and outsiders cannot spy on you. You must cast off knowledge and views, discard mysteries and marvels, and abandon all contrived actions. You simply eat when hungry and drink when thirsty; that's all.

At this stage you are never aware of having mind or not having mind, of gaining mindfulness or losing mindfulness. So how could you still be attached to what you have previously learned and understood, to "mysteries" and "marvels" and analysis of essential nature, to the fetters of names and forms and arbitrary opinions? How could you still be attached to views of "Buddha" and views of "Dharma" or to earth-shaking worldly knowledge and intellect? You would be tying and binding yourself, you would be counting the grains of sand in the ocean. What would there be to rely on?

All those who are truly great must strive to overcome the obstacles of delusion and ignorance. They must strive to jolt the multitudes out of their complacency and to fulfill their own fundamental intent and vows. Only if you do this are you a true person of the Path, without contrived activity and without concerns, a genuine Wayfarer of great mind and great vision and great liberation.

Transmitting Wisdom

For Buddha's pure transmission on Spirit Peak, for Bodhidharma's secret bequest on Few Houses Mountain, you must stand out beyond categories and apart from conventions and test it in the movements of the windblown dust and grasses.

With your eyes shining bright, you penetrate through obscurities and recognize what is happening on the other side of the mountain. You swallow your sound and eliminate your traces, without leaving behind anything whatsoever. Yet you can set in motion waves that go against the current and employ the ability that cuts off the flow. You are swift as a falcon that gets mistaken for a shadow as it soars into the air with its back to the deep blue sky. In the blink of an eye, it's gone. Point to it, and it comes. Press it, and it goes. It is unstoppably lofty and pure.

This is the way this true source is put into circulation, to serve as a model and standard for later generations. All those who would communicate the message of the source must be able to see through a person's false personality without blinking an eye; only then can they enter into it actively.

People with the will to reach the Truth must be fully developed and thoroughly polished to be able to go beyond conventions and transcend sects. They can only be seedlings of transcendence when at the subtle level they can see through every drop, and at the expansive level the thousand sages cannot find them.

Old Master Zufeng used to say, “Even Shakyamuni Buddha and Maitreya Buddha are servants of the Way. Ultimately, what is the Way?” How can this admit of arbitrary and confused probing? You will only get what you are aiming for if you realize the Way.

In general, a good Zen teacher will energize the indomitable spirit of the great person inside a student and cause them to move ahead into the superior stream so that they cannot be trapped or called back. As a teacher helps people respond to their potential, the process should all be clear and freeing. If the supposed teacher uses contrived concepts of “mysteries” and “marvels” and “the essence of truth,” how can this produce any genuine expedient teachings? If they put a gleam in their eye and strut around uttering apt sayings of doctrines they claim to be absolute reality, this is just one blind man leading a crowd of blind people further into confusion.

When you make contact with Truth, then it covers heaven and earth. Always nurturing it and putting it into practice, you discover an extraordinary state. Only then do you share the understanding that comes from Spirit Peak and Few Houses Mountain.

Who says that no one perceives “the priceless pearl?” I say the black dragon's pearl shines forth wherever it is.

Yuanwu Keqin's Dharma Lineage

[...]

菩提達磨 Bodhidharma, Putidamo (Bodaidaruma ?-532/5)

大祖慧可 Dazu Huike (Taiso Eka 487-593)

鑑智僧璨 Jianzhi Sengcan (Kanchi Sōsan ?-606)

大毉道信 Dayi Daoxin (Daii Dōshin 580-651)

大滿弘忍 Daman Hongren (Daiman Kōnin 601-674)

大鑑慧能 Dajian Huineng (Daikan Enō 638-713)

南嶽懷讓 Nanyue Huairang (Nangaku Ejō 677-744)

馬祖道一 Mazu Daoyi (Baso Dōitsu 709-788)

百丈懷海 Baizhang Huaihai (Hyakujō Ekai 750-814)

黃蘗希運 Huangbo Xiyun (Ōbaku Kiun ?-850)

臨濟義玄 Linji Yixuan (Rinzai Gigen ?-866)

興化存獎 Xinghua Cunjiang (Kōke Zonshō 830-888)

南院慧顒 Nanyuan Huiyong (Nan'in Egyō ?-952)

風穴延沼 Fengxue Yanzhao (Fuketsu Enshō 896-973)

首山省念 Shoushan Shengnian (Shuzan Shōnen 926-993)

汾陽善昭 Fenyang Shanzhao (Fun'yo Zenshō 947-1024)

石霜/慈明 楚圓 Shishuang/Ciming Chuyuan (Sekisō/Jimei Soen 986-1039)

楊岐方會 Yangqi Fanghui (Yōgi Hōe 992-1049)

白雲守端 Baiyun Shouduan (Hakuun Shutan 1025-1072)

五祖法演 Wuzu Fayan (Goso Hōen 1024-1104)

圜悟克勤 Yuanwu Keqin (Engo Kokugon 1063-1135)

YUAN-WU

Translated by Thomas Cleary

In: The five houses of Zen, 1997

The revival of Lin-chi Zen was brought to its greatest level of sophistication in the tenth generation by the Zen master Yuan-wu (1063–1135), whose famous Essentials of Mind also became a Zen classic. Extracts of this work are presented here.

Essentials of Mind

WHEN THE FOUNDER of Zen came to China from India, he did not set up written or spoken formulations; he only pointed directly to the human mind. Direct pointing just refers to what is inherent in everyone: the whole being appearing responsively from within the shell of ignorance, it is not different from the sages of time immemorial. That is what we call the natural, real, inherent nature, fundamentally pure, luminous and sublime, swallowing and spitting out all of space, the single solid realm alone and free of the senses and objects.

With great capacity and great wisdom, just detach from thought and cut off sentiments, utterly transcending ordinary conventions. Using your own inherent power, take it up directly right where you are, like letting go your hold over a mile-high cliff, freeing yourself and not relying on anything anymore, causing all obstruction by views and understanding to be thoroughly removed, so that you are like a dead man without breath, and reach the original ground, attaining great cessation and great rest, which the senses fundamentally do not know and which consciousness, perception, feelings, and thoughts do not reach.

After that, in the cold ashes of a dead fire, it is clear everywhere; among the stumps of dead trees everything illumines: then you merge with solitary transcendence, unapproachably high. Then there is no more need to seek mind or seek Buddha: you meet them everywhere and find they are not obtained from outside.

The hundred aspects and thousand facets of perennial enlightenment are all just this: it is mind, so there is no need to still seek mind; it is Buddha, so why trouble to seek Buddha anymore? If you make slogans of words and produce interpretations on top of objects, then you will fall into a bag of antiques and after all never find what you are looking for.

This is the realm of true reality where you forget what is on your mind and stop looking. In a wild field, not choosing, picking up whatever comes to hand, the obvious meaning of Zen is clear in the hundred grasses. Indeed, the green bamboo, the clusters of yellow flowers, fences, walls, tiles, and pebbles use the teaching of the inanimate; rivers, birds, trees, and groves expound suffering, emptiness, and selflessness. This is based on the one true reality, producing unconditional compassion, manifesting uncontrived, supremely wondrous power in the great jewel light of nirvana.

An ancient master said, “Meeting a companion on the Way, spending a life together, the whole task of study is done.” Another master said, “If I pick up a single leaf and go into the city, I move the whole of the mountain.” That is why one ancient adept was enlightened on hearing the sound of pebbles striking bamboo, while another was awakened on seeing peach trees in bloom. One Zen master attained enlightenment on seeing the flagpole of a teaching center from the other side of a river. Another spoke of the staff of the spirit. One adept illustrated Zen realization by planting a hoe in the ground; another master spoke of Zen in terms of sowing the fields. All of these instances were bringing out this indestructible true being, allowing people to visit a greatly liberated true teacher without moving a step.

Carrying out the unspoken teaching, attaining unhindered eloquence, thus they forever studied all over from all things, embracing the all-inclusive universe, detaching from both abstract and concrete definitions of buddhahood, and transcendentally realizing universal, all-pervasive Zen in the midst of all activities. Why necessarily consider holy places, teachers’ abodes, or religious organizations and forms prerequisite to personal familiarity and attainment of realization?

Once a seeker asked a great Zen teacher, “I, so-and-so, ask: what is the truth of Buddhism?” The teacher said, “You are so-and-so.” At that moment the seeker was enlightened. As it is said, “What comes from you returns to you.”

An ancient worthy, working in the fields in his youth, was breaking up clumps of earth when he saw a big clod, which he playfully smashed with a fierce blow. As it shattered, he was suddenly greatly enlightened.

After this he acted freely, becoming an unfathomable person, often manifesting wonders. An old master brought this up and said, “Mountains and rivers, indeed the whole earth was shattered by this man’s blow. Making offerings to the buddhas does not require a lot of incense.” How true these words are!

The ultimate Way is simple and easy, yet profoundly deep. From the beginning it does not set up steps—standing like a wall a mile high is called the basic fodder. Therefore ancient buddhas have been known to carry out this teaching by silence.

Still there are adepts who wouldn’t let them go at that, much less if they got into the marvelous and searched for the mysterious, spoke of mind and discoursed on nature, having sweaty shirts sticking to their flesh, unable to remove them—that would just seem all the more decrepit.

The example of the early Zen founders was exceptionally outstanding. The practical strategies of the classical masters were immediately liberating. Like dragons racing, tigers running, like the earth turning and the heavens revolving, in all circumstances they vivified people, ultimately without trailing mud and water.

As soon as they penetrated the ultimate point in truth, those since time immemorial who have realized great enlightenment have been fast as falcons, swift as hawks, riding the wind, dazzling in the sun, their backs brushing the blue sky.

Penetrate directly through to freedom and make it so that there is not the slightest obstruction at any time, twenty-four hours a day, with the realization pervading in all directions, rolling up and rolling out, capturing and releasing, not occupying even the rank of sage, much less being in the ordinary current.

Then your heart will be clear, comprehending the present and the past. Picking up a blade of grass, you can use it for the body of Buddha; taking the body of Buddha, you can use it as a blade of grass. From the first there is no superiority or inferiority, no grasping or rejection.

It is simply a matter of being alive to meet the situation: sometimes you take away the person but not the world; sometimes you take away the world but not the person; and sometimes both are taken away; and sometimes neither is taken away.

Transcending convention and sect, completely clear and free, how could you just want to trap people, to pull the wool over their eyes, to turn them around, to derail them? It is necessary to get to the reality and show them the fundamental thing in each of them, which is independent and uncontrived, which has nothing to it at all, and which is great liberation.

This is why the ancients, while in the midst of activity in the world, would first illuminate it, and as soon as there was the slightest obstruction, they would cut it off entirely. Even so they could hardly find anyone who could manage to learn this—how could they compare to these people who drag each other through the weeds, draw each other into assessments and judgments of words and deeds, make nests, and bury the sons and daughters of others?

Clearly we know that these latter people are “wetting the bed with their eyes open,” while those other, clear-eyed people would never make such slogans and conventions. With a robust and powerful spirit that astounds everyone, you should aim to truly inherit this school of Zen: with every exclamation, every stroke, every act, every objective, you face reality absolutely and annihilate all falsehood. As it is said, “Once the sharp sword has been used, you should hone it right away.”

When your insight penetrates freely and its application is clear, then when going into action in the midst of all kinds of complexity and complication, you yourself can turn freely without sticking or lingering and without setting up any views or maintaining any state, flowing freely: “When the wind blows, the grasses bend.”

When you enter enlightenment in actual practice, you penetrate to the profound source, cultivating this until you realize freedom of mind, harboring nothing in your heart. Here even understanding cannot attain it, much less not understanding.

Just be this way twenty-four hours a day, unfettered, free from bondage. From the first do not keep thoughts of subject and object, of self and senses, or even of Buddhism. This is the realm of no mind, no fabrication, no object—how could it be fathomed or measured by worldly brilliance, knowledge, intelligence, or learning, without the fundamental basis?

Did the Zen founder actually “bring” this teaching when he came to China from India? He just pointed directly to the inherent nature in every one of us, to let us get out completely, clear and clean, and not be stained by so much false knowledge and false consciousness, delusory conceptions, and judgments.

Study must be true study. A true teacher does not lead you into a nest of weeds but cuts directly through so that you meet with realization, shedding the sweaty shirt sticking to your skin, making the heart empty and open, without the slightest sense of the ordinary or the holy. Since you do not seek outside, real truth is there, resting peacefully, immutable. No one can push you away, even a thousand sages—having attained a pure, clean, and naked state, you pass through the other side of the empty eon, and even the prehistoric buddhas are your descendants. Why even speak of seeking from others?

The Zen masters were all like this, ever since the founders. Take the example of the Sixth Grand Master: he was an illiterate woodcutter in south China, but when he came and met the Fifth Grand Master, at their first meeting he opened his heart and clearly passed through to freedom.

So even though the saints and sages are mixed in with others, one should employ appropriate means to clearly point out what is inherent in everyone, regardless of their level of intelligence.

Once you merge your tracks in the stream of Zen, spend the days silencing your mind and studying with your whole being, knowing this great cause is not gotten from anyone else. It is just a matter of bearing up bravely and strongly, ever progressing, day by day shedding, day by day improving, like pure gold smelted and refined hundreds and thousands of times.

As it is essential to getting out of the dusts and it is basic to helping people, it is most necessary to be thoroughly penetrating and free in all ways, reaching to peace without doubt and realizing great potential and great action.

This work lies in one’s inner conduct: in everyday life’s varied mix of myriad circumstances, in the dusty hubbub, amidst the ups and downs and conditions, appear and disappear without being turned around by any of it. Instead, you can actively turn it around. Full of life, immune to outside influences, this is your own measure of power.

On reaching empty, frozen silence, there is no duality between noise and quiet. Even when it comes to extraordinary words, marvelous statements, unique acts, and absolute perspectives, you just level them with one measure. Ultimately they have no right or wrong, it’s all in how you use them.

When you have continued grinding and polishing yourself like this for a long time, you will be free in the midst of birth and death and look upon society’s useless honor and ruinous profit as like dust in the wind, phantoms in dreams, flowers in the sky. Passing unattached through the world, would you not then be a great saint who has left the dusts?

Whenever the Zen master known as the Bone Breaker was asked a question, he would just answer, “Bone’s broken.” This is like an iron pill, undeniably strict. If you can fully comprehend it, you will be a true lion of the Zen school.

Once a great National Teacher of Zen asked another Zen master, “How do you see all extraordinary words and marvelous expressions?” The Zen master said, “I have no fondness for them.” The National Teacher said, “This is your own business.”

When Zen study reaches this point, one is pure, clean, and dry, not susceptible to human deceptions.

YUANWU KEQIN, “FOGUO,” “SHAOJUE”

IN: Zen's Chinese heritage: the masters and their teachings

by Andy Ferguson

Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2000. pp. 459-465.

YUANWU KEQIN (1063–1135) was a disciple of Wuzu Fayan. He came from Chongzhu City in Pengzhou. A gifted youth who thoroughly studied the Confucian classics, he is said to have written one thousand words every day. During a visit to Miaoji Monastery he observed some Buddhist scriptures and was surprised by a strong feeling that he had previously possessed them. He then left home and studied under a Vinaya master named Zisheng and a scriptural teacher named Yuanming.

Foguo once became deathly ill. He realized that his scriptural study and chanting of Buddha’s name was insufficient, saying, “The true path of nirvana of all the buddhas is not found in words. I’ve used sounds to seek form, but it’s of no use for dealing with death.” After he recovered he set off to seek instruction from the Zen school.

Foguo first studied under a Zen master named Zhenjiao Sheng in Sichuan. During one of their discussions, Sheng pricked his arm and bled a few drops of blood.

Sheng showed it to Foguo and said, “This is a drop of Cao Creek.”

This startled Foguo, and only after some time he responded, saying, “Is it really?”

Foguo then left Sichuan and traveled to several teachers, including Dagui Muche and Huanglong Zuxin. Everywhere he went his teachers said that he was to be a great vessel for the Dharma. Huitang declared, “Someday, the entire Linji school will be his disciples.”

Finally, Foguo met the great teacher Wuzu. However, Foguo felt that their first meeting was a failure because Wuzu seemed aloof and unsympathetic. Foguo became angry and began to walk away. As he left, Wuzu called after him, “Wait until you become feverishly ill, then think of me!”

Foguo went to Jinshan. There he became extremely ill. Remembering Wuzu’s words, he pledged to return to study with him when he recovered.

When Wuzu saw Foguo return he laughed and told him to go to the practice hall. Foguo then took the position of Wuzu’s attendant.

An official of the exchequer named Tixing retired and returned to Sichuan, where he sought out Wuzu to learn about Zen. Wuzu said to him, “When you were young, did you read a poem by Xiaoyan or not? There were two lines that went something like, ‘Oh these trinkets mean nothing, for I only want to hear the familiar sounds of my lover.’”

Tixing said, “Yes, I read them.”

Wuzu said, “The words are well crafted.”

Just then, Foguo came in attendance. He asked, “I heard the master mention the poem by Xiaoyan. Does Tixing know it or not?”

Wuzu said, “He just knows the words.”

Foguo said, “‘I only want to hear the familiar sounds of my lover.’ If he knows the words, why doesn’t he understand it?”

Wuzu said, “Why did Bodhidharma come from the west? The cypress tree in front of the garden!”

At these words Foguo was suddenly enlightened. He went outside the cottage and saw a rooster fly to the top of a railing, beat his wings, and crow loudly. He said to himself, “Is this not the sound?”

Foguo then took incense [to light in gratitude] and went back into Wuzu’s room. There he revealed his attainment and offered this verse:

The golden duck vanishes into the gilt brocade.

With a rustic song, the drunkard returns in the woods.

A youthful love affair

Is known only by the young beauty.Wuzu then said, “The great matter of the Buddha ancestors is not sought by inferior vessels. I share your joy.”

Wuzu then informed the prominent elders of the temple, saying, “My attendant has attained the goal of Zen practice.” Because of this, Foguo was promoted to the position of head monk.

Another story of Foguo’s early experience under his teacher Wuzu Fayan is recorded in the classical Zen text, Fozu Lidai Tongzai (Complete Historical Record of the Buddha Ancestors).*

*佛祖歷代通載 (A comprehensive record of the history of the Buddhas and Patriarchs) by Nianchang 念常 (1282-1344).

When [Yuanwu’s teacher] Fayan first came to Wuzu Temple, Yuanwu was working there as temple manager. At that time a new kitchen was to be built in an area where a beautiful tree stood.

Fayan said, “Although the tree is in the way, don’t cut it down.”

Yuanwu cut down the tree anyway.

Fayan reacted furiously, and picking up his staff he chased after Yuanwu as if to strike him. Yuanwu began to run away to avoid the beating, but then suddenly experienced great enlightenment and cried out, “This is the way of Linji!”

He then grabbed the staff away from Fayan and said, “I recognize you, you old thief!”

Fayan laughed and went off.

From this time forward, Fayan allowed Yuanwu to lecture the Dharma to the other monks.

During the Chongning era (1102–6), Foguo assumed the abbacy of Zhaojue Temple ("Luminous Enlightenment"). He later moved to Xingzhou, where a famous contemporary teacher by the name of Zhang Wujin paid him a visit to discuss the doctrines of Zen and Huayan Buddhism. From this event, Foguo’s fame spread widely. Foguo then resided at Blue Cliff Temple on Mt. Jia.

There his students appended Foguo’s spoken commentaries to an earlier manuscript known as the Odes on the Hundred Cases, a collection of kōans and added verses by Xuedou Chongxian. The resulting text, called the Blue Cliff Record, has served as a preeminent volume of kōans for subsequent generations of Zen students. Gaining wide popularity during Foguo’s lifetime, the Blue Cliff Record received both praise and condemnation. To some it represented the highest standard of Zen literature. To others it represented a subversion of Zen’s tradition of pointing directly at mind and shunning the study of written words as a vehicle for liberation. Foguo’s famous Dharma heir, Dahui Zonggao, was so alarmed by the success of his teacher’s book that he attempted to destroy as many copies as possible. However, the book’s circulation was, for better or worse, beyond Dahui’s ability to stop it.

Among Foguo’s admirers was the high government official Deng Zi, who presented to Foguo the ceremonial purple robe and the name that accompanied him to posterity. Emperor Gao Zong summoned Foguo, and conferred upon him the name Zen Master Yuan Wu (“Perfect Enlightenment”).

Foguo entered the hall and addressed the monks, saying: “The eye cannot see the pervasive Buddha body. The ear cannot hear the pervasive Buddha body. Speech cannot describe the pervasive Buddha body. The mind cannot imagine the pervasive Buddha body. Even if you can behold the entire great earth, not missing a trace, then you’ve gone only half-way. And if called on to do so, how could you describe it? Within its boundaries the sun and moon are suspended—the universal clear emptiness—the endless source of spring.”

Foguo entered the hall and addressed the monks, saying, “Fifteen days before, a thousand oxen can’t drag it back. Fifteen days later, even the swift falcon can’t chase it. Just at fifteen days; the sky serene; the earth serene; equally clear; equally dark. The myriad realms are not revealed here. It can swallow and spit out the ten voids. Step forward and you step across an indescribable fragrant-water ocean. Step back and you rest upon endless miles of white clouds. Stepping neither forward nor back, there is the place where the worthies don’t speak, where this old monk doesn’t open his mouth.”

Raising his whisk he said, “Just when it’s like this, what is it?”

Foguo addressed the monks, saying, “Great waves arise on the mountain tops. Dust rises from the bottom of a well. The eyes hear a thunderclap. The ears see a great brocade. The three hundred sixty bones [of the human body] each reveal the incomparably sublime body. The tips of eighty-four thousand hairs display the chiliocosm sea of worlds of the Treasure King. But this is not the pervasive numinous function. Nor is it the manifested Dharma. If only the thousand eyes can suddenly open, then you’ll be sitting throughout the ten directions. If you could describe this in a single surpassing phrase, what would you say? To test jade it must be passed through fire. To find the pearl, don’t leave the mud.”

The following passages are taken from The Record of Foguo.*

*圓悟佛果禪師語錄 Yuanwu Foguo chanshi yulu

Foguo entered the hall.

A monk asked him, “In all of the great canon of scripture, what is the most essential teaching?”

Foguo said, “Thus I have heard.”

Then Foguo said, “This was what Ananda said. What do you say?”

Foguo entered the hall.

A monk asked him, “What is the true host?”

Foguo said, “The myriad streams return to the sea. A thousand mountains honor the essential doctrine.”

Yuanwu Keqin ascended the seat and said, “The heat of a fire cannot compare with the heat of the sun. The cold wind cannot compare with the coldness of the moon. A crane’s legs are naturally long and a duck’s legs are naturally short. A pine tree is naturally tall and straight, while brambles are crooked. Geese are white. Crows are black. Everything is manifested in this manner. When you completely comprehend this, then everywhere you go you’ll be the host. Everything you meet will be the teaching. When you carry this pole, you’ll be prepared to fight anywhere. Do you have it? Do you have it?”

Foguo entered the hall and said, “Zen is without thought or intention. Setting forth a single intention goes against the essential doctrine. The great Way ends all meritorious work. When merit is established, the essential principle is lost. Upon hearing a clear sound or some external words, do not seek some meaning within them. Rather, turn the light inward and use the essential function to pound off the manacles of the buddhas and ancestors. Where Buddha is, there is also guest and host. Where there is no Buddha, the wind roars across the earth. But when the mind’s intentions are stilled, even a great noise becomes a soothing sound. Tell me, where can such a person be found? Put on a shawl and stand outside the thousand peaks. Draw water and pour it on the plants before the five stars.”220

“All the desires of my original mind are fulfilled by the treasury that is naturally here before me. The sky is up above. Down below is the earth. To the left is the kitchen, and to the right is the monk’s hall. Before me is the Buddha hall and temple gate, and behind me is the dormitory and abbot’s quarters. So where is the treasury? Do you see it? If we stand and sit in a dignified manner, and listen and speak clearly, then brilliant light floods our eyes and there is limitless peace. All sacred and mundane affairs are extinguished and all confining views are dropped away. The Yang-tse River is nectar and the great earth is gold. If from within one’s chest a single phrase were to flow forth, what would be said? ‘Since ancient times it has streamed like white silk.’ ‘Upon the horizon are seen the blue mountains.’”

Yuanwu said to the monks, “There is a bright road that the buddhas and ancestors knew. You are facing it, and what you see and hear is not separate from it. The myriad things cannot conceal it and a thousand saints can’t embody it. It is vibrant. It can’t be carried. It is clearly exposed. It is without impediment. Even if you undergo blows from the staff like rain, and shouts like thunderclaps, you’re still no closer to the ultimate principle. What is the ultimate principle? Blind the eyes of the saints and strike me dumb! When the bell strikes at midday, look south and see the Northern Dipper!”

The master then got down and left the hall.

Yuanwu said, “The sword that kills. The sword that gives life. These are artifices of the ancients, and yet they remain pivotal for us today. Trying to understand from words is like washing a dirt clod in muddy water. But not using words to gain understanding is like trying to put a square peg in a round hole. If you don’t use some idea you’ve already missed it. But if you have any strategy whatsoever, you’re still a mountain pass away from it. It’s like the sparks from struck flint or a lightning flash. Understanding or not understanding, there’s no way to avoid losing your body and life. What do you say about this principle? A bitter gourd is bitter to the root. A sweet melon is sweet to the base!”

The master then got down and left the hall.

Late in August in the year 1135, Foguo appeared to be slightly ill. He sat upright and composed a farewell verse to the congregation. Then, putting down the brush, he passed away. His cremated remains were placed in a stupa next to Zhaojue Temple.