ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

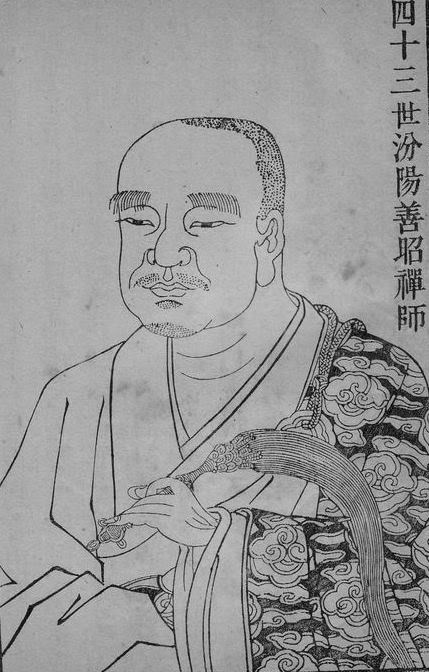

汾陽善昭 Fenyang Shanzhao (942-1024)

行脚歌 Xingjiao ge

(Rōmaji:) Fun'yō Zenshō: Angyaka

(English:) Song of Angya

(Magyar:) Fen-jang San-csao: Hszingcsiao ko / Zarándokének

汾陽無德禪師語錄 Fenyang Wude chanshi yulu

(Rōmaji:) Funyō Mutoku zenshi goroku

(English:) Records of Sayings of Chan Master Fenyang Wude

Tartalom |

Contents |

Az Öt Állapot Fen-jang San-csao mondásaiból |

Song of Angya Song of Right and Wrong Poem in Praise of Coming from the West PDF: The Recorded Sayings of Chan Master Fenyang Wude (Fenyang Shanzhao) |

行腳歌

http://www.cbeta.org/result/normal/T47/1992_003.htm

發志辭親。意欲何能。投佛出家。異俗專心。

慕法為僧。既得尸羅具備。又能法服霑身父母。

不供甘旨王侯。不侍不臣。潔白修持。

如冰似玉。不名不利。去垢去塵。受人天之瞻敬。

承釋梵之恭勤。忖德業量來處。將何報答為門戶。

專精何行即能消。唯有參尋別無路。

苦身心歷山水。白眉作伴為參禮。冒雪衝霜不避寒。

渡水穿雲伏龍鬼。銕錫飛銅瓶滿。

不問世間長與短。叢林道侶要商量。四句百非一齊翦。

探玄機明道眼。入室設針須鍛鍊。

驅邪顯正自應知。勿使身心有散亂。道難行塵易漫。

頭頭物物須明見。區區役役走東西。

今古看來忙無限。我今行勤自辨。莫教失卻來時伴。

舉足動步要分明。切忌被他虛使喚。

入叢林行大道。不著世間虛浩浩。堅求至理不辭勞。

剪去繁華休作造。百衲衣雲水襖。

萬事無心離煩惱。千般巧妙不施功。直出輪迴生死道。

勸同袍求正見。莫似愚夫頻改變。

投[山/品]立雪猛身心。方得法王常照現。請益勤恭敬速。

不避寒喧常不足。只緣心地未安然。

不羨榮華不怕辱。直教見性不從他。自家解唱還鄉曲。

度平生實安樂。蕩蕩縱橫無依托。

四方八面應機緣。萬象森羅任寬廓。報四恩拔三有。

問答隨機易開口。五湖四海乍相逢。

一擊雷音師子吼。悠悠自在樂騰騰。大地乾坤無過咎。

分明報爾水雲僧。記取面南看北斗。讚曰。

五湖四海歷叢林。萬里千山不易尋。

親覲祖宗明見性。莫將薺苨作人蔘。

Fenyang Shanzhao's Dharma Lineage

[...]

菩提達磨 Bodhidharma, Putidamo (Bodaidaruma ?-532/5)

大祖慧可 Dazu Huike (Taiso Eka 487-593)

鑑智僧璨 Jianzhi Sengcan (Kanchi Sōsan ?-606)

大毉道信 Dayi Daoxin (Daii Dōshin 580-651)

大滿弘忍 Daman Hongren (Daiman Kōnin 601-674)

大鑑慧能 Dajian Huineng (Daikan Enō 638-713)

南嶽懷讓 Nanyue Huairang (Nangaku Ejō 677-744)

馬祖道一 Mazu Daoyi (Baso Dōitsu 709-788)

百丈懷海 Baizhang Huaihai (Hyakujō Ekai 750-814)

黃蘗希運 Huangbo Xiyun (Ōbaku Kiun ?-850)

臨濟義玄 Linji Yixuan (Rinzai Gigen ?-866)

興化存獎 Xinghua Cunjiang (Kōke Zonshō 830-888)

南院慧顒 Nanyuan Huiyong (Nan'in Egyō ?-952)

風穴延沼 Fengxue Yanzhao (Fuketsu Enshō 896-973)

首山省念 Shoushan Shengnian (Shuzan Shōnen 926-993)

汾陽善昭 Fenyang Shanzhao (Fun'yo Zenshō 947-1024)

![]()

"Song of Angya"

by Fun'yō Zenshō, a notable Chinese zen master of the early Sung, as published in the chapter on "Initiation" as a Zen monk,

in D.T. Suzuki's The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk, pp. 5-6.

Determined to leave his parents, what does he want to accomplish?

He is a Buddhist, a homeless monk now, and no more a man of the world;

His mind is ever intent on the mastery of the Dharma.

His conduct is to be as transparent as ice or crystal,

He is not to seek fame and wealth,

He is to rid himself of defilements of all sorts.

He has no other way open to him but to go about and inquire;

Let him be trained in mind and body by walking over the mountains and fording the rivers;

Let him befriend wise men in the Dharma and pay them respect wherever he may accost them;

Let him brave the snow, tread on the frosty roads, not minding the severity of the weather;

Let him cross the waves and penetrate the clouds, chasing away dragons and evil spirits.

His iron staff accompanies him wherever he travels and his copper pitcher is well filled,

Let him not then be annoyed with the longs and shorts of worldly affairs,

His friends are those in the monastery with whom he may weigh the Dharma,

Trimming off once for all the four propositions and one hundred negotiations.

Beware of being led astray by others to no purpose whatever;

Now that you are in the monastery your business is to walk the great path,

and not to get attached to the world, but to be empty of all trivialities;

Holding fast on to the ultimate truth do not refuse hard working in any form;

Cutting yourself away from noise and crowds, stop all your toiling and craving.

Thinking of the one who threw himself down the precipice, and the one who stood all night in the snow, gather up all your fortitude,

So that you may keep the glory of your Dharma-king manifested all the time;

Be ever studious in the pursuit of the Truth, be ever reverential toward the Elders;

You are asked to stand the cold and the heat and privations,

Because you have not yet come to the abode of peace;

Cherish no envious thoughts for wordly prosperity, be not depressed just because you are slighted

But endeavor to see directly into your own nature, not depending on others.

Over the five lakes and the four seas you pilgrim from monastery to monastery;

To walk thousands of miles over hundreds of mountains is indeed no easy task;

May you finally intimiately interview the master in the Dharma and be led to see into your own nature,

When you will no more take weeds for the medicinal plants.

是非歌

Song of Right and Wrong

from

汾陽無德禪師語錄 Fenyang Wude chanshi yulu

Records of Sayings of Chan Master Fenyang Wude (1004)

Translated by John Balcom

In: After Many Autumns: A Collection of Chinese Buddhist Literature

edited by John Gill, Susan Tidwell,

Buddha's Light Publishing, 2011

One who leaves home to learn the Way should know:

In the monastic assembly be sure not to violate the order.

Be kind and respectful to those who explain the truth and are virtuous.

Do not associate with fools who gossip.

Hear one speak well of you and your mind is joyful;

Hear one speak ill of you and hate him to death.

Good and evil both come from the mind,

Seek the course of reason in between.

Worldly people are more lacking in wisdom,

They do not attempt to understand or think, and gossip arises.

A great, wise person looks at it

And does not get involved.

Zilu was scolded when he encountered a fisherman.1

Confucius once felt shame for forgetting to wear his shoes.

The first thing recorded about Sariputra

Was how he was personally fooled by a fool.2

The Tathagata looks at all sentient beings with his eyes of compassion,

He knows the past and present, and clearly sees the truth.

These dynasties—Zhou, Qin, Han, and Wei,

Each of these countries was destroyed for the same reason.3

For many kalpas, gossip has been the cause of hell,

When you hear or speak of right and wrong, examine the details.

I hear it spoken, my mind does not arise—

This is gossip. It stops at me.

Still, there are some empty words that cannot be polished;

To ask for what reason the patriarch came from the west.

If you wish for clarity, to be able to distinguish the roots from the branches,

Understand the true basis of gossip.

More people come to speak gossip,

But now I already recognize you.

Notes

1: Reference to Zhuangzi, where Confucius scolds his disciple Zilu for not recognizing a humble fisherman as a sage.

2: Reference to a past life of Sariputra, a great disciple of the Buddha. As a monk he encounters a man who says his mother is dying, and that only medicine made from a monk’s eyeball can cure her. Sariputra plucks out his eye, but the man says that only the right eyeball will do. Having removed his left, the monk then removes the other eye. The man smells the eye, says it is too smelly to be medicine, and crushes it.

3: The end of each dynasty was accelerated by some form of infighting.

西來意頌詩

Poem in Praise of Coming from the West

Translated by John Balcom

Cypress trees grow up from the land in the courtyard .

There is no need for ox or plow to till this peak.

This is the right way to teach the one thousand roads from the west.1

The dense, dark woods all have eyes.

1: Many methods for teaching the Dharma. “West” is a reference to India, and one thousand to the multiplicity of teachings.

![]()

Fen-jang San-csao mondásaiból

Terebess Gábor fordítása

– Ha ezer mérföldön belül egy fia felhő se lenne, mit tennél? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

– Megbotoznám az eget – mondta Fen-jang.

– Miért épp az eget kárhoztatnád?

– Mert sose akkor esik az eső és sose akkor süt a nap, amikor kellene.

Az Öt Állapot

Five States by Fen Yang (947–1024)

Fordította: Komár Lajos

A valóság közepéből kiáradó:

a gyémántkirály drágaköves kardja

odasuhint az égnek, akár a tudati villám.

Akadálytalanul beragyogja a világot, mint a kristály:

tiszta ragyogása szeplőtlen.A jelenség a valóságban:

a lendületes szónok mennydörgő beszéde

szikrát hány, villámot szór.

Buta, korlátolt ember módjára figyeled,

s habozásod messzire taszít onnét.A valóság a jelenségben:

látod a kerékforgató királyt; uralod

a parancsolót, annak hét kincsét, ezernyi utódát.

Mindenki melléd szegődik az úton, és

te még mindig egy aranytükröt keresgélsz.Mindkettőben felbukkanó:

a hároméves aranyoroszlán

szája nyitva, fogai élesek.

Mennydörgő üvöltése

megrémiszti a gonosz szellemeket.Egyszerre észlelni mindkettőt:

az uralkodói hatalom erőlködés nélküli:

ne akard a fabikát sétáltatni.

A valódi bika keresztülvág a tűzön:

íme, a Tankirály csodálatos hatalma.A valóság közepéből kiáradó: a lótuszvirág kiszáradt földön virágzik,

arany kelyhe és ezüst szára megmártózik a türkiz harmatcseppekben.

A jeles szerzetes nem üldögél a főnix talapzatán.A jelenség a valóságban: ragyog az éjféli hold, a nap kénytelen üdvözölni a hajnalt.

A valóság a jelenségben: a hajszálból hatalmas fa cseperedik, a vízcsepp folyóvá duzzad.

Mindkettőben felbukkanó: a lényeg nem a mennyből vagy a földről származik;

a hősiesség sem az évszakok váltakozása szerint van. Akkor honnan fakad?Egyszerre észlelni mindkettőt: a türkiz asszony odadobja a vetélőt a pörgő szövőszéken;

a kőember megüti dobját: bumm, bumm.