ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

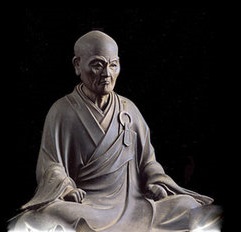

鈴木正三 Suzuki Shōsan (1579-1655)

![]()

Suzuki Shōsan on Christianity, 1642

Suzuki Shosan was a Japanese samurai, and originator of what came to be known as “Ferocious Zen,” which advocated action and courage rather than contemplation. He wrote this attack on Christian teachings in 1642, shortly after Christianity had been banned in Japan as part of the effort to remove all foreign influences.

According to the Kirishitan teachings, the Great Buddha named Deus is the Lord of Heaven and Earth and is the One Buddha, self-sufficient in all things. He is the Creator of Heaven and Earth and of the myriad phenomena. This Buddha made his entry into the world one thousand six hundred years ago in South Barbary , saving all sentient beings. His name is Jesus Christus. That other lands do not know him, worshipping instead the worthless Amida and Shaka, is the depth of stupidity. Thus they claim, as I have heard.

To counter, I reply: If Deus is the Lord of Heaven and Earth, and if he created the terrestrial domain and the myriad phenomena, then why has this Deus until now left abandoned a boundless number of countries without making an appearance? Ever since heaven and earth were opened up, the Buddhas of the Three Worlds in alternating appearance have endeavored to save all sentient beings, for how many thousands and tens of thousands of years! But meanwhile, in the end Deus has not appeared in countries other than South Barbary; and what proof is there that he did make an appearance of late, in South Barbary alone? If Deus were truly the Lord of Heaven and Earth, then it has been great inattention on his part to permit mere attendant Buddhas to take over country upon country which he personally created, and allow them to spread their Law and endeavor to save all sentient beings, from the opening up of heaven and earth down to the present day. In truth, this Deus is a foolscap Buddha!

And then there is the story that Jesus Christus upon making his appearance was suspended upon a cross by unenlightened fools of this lower world. Is one to call this the Lord of Heaven and Earth? Is anything more bereft of reason? This Kirishitan sect will not recognize the existence of the One Buddha of Original Illumination and Thusness. They have falsely misappropriated one Buddha to venerate, and have come to this country to spread perniciousness and deviltry. They shall not escape Heaven's punishment for this offence! But many are the unenlightened who fail to see through their clumsy claims, who revere their teachings and even cast away their lives for them. Is this not a disgrace upon our country? Notorious even in foreign lands, lamentable indeed!

PDF: Guiding the Blind Along the Middle Way:

A Parallel Reading of Suzuki Shōsan's Mōanjō and The Doctrine of the Mean

by Anton Luis C. Sevilla

Journal of Buddhist Ethics

PDF: Suzuki Shōsan (1579-1655): Method of Buddhist Practice Based on Ki

by Michiko KATO

PDF: Suzuki Shōsan, Wayfarer

by Winston L. King

The Eastern Buddhist. New series 12/1, pp. 83-103.

PDF: Selections from Suzuki Shōsan

tr. by Winston L. King

The Eastern Buddhist. New series,12/2, pp. 117-143.

鈴木正三 Suzuki Shōsan (1579-1655)

Portrait by ©Goto Asuka

PDF: Selected Writings of Suzuki Shosan

by Suzuki Shosan

Translated by Royall Tyler

(Cornell University East Asia Papers, Number 13)

China-Japan Program, Cornell University, 1977, 280 p.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction 1

Ninin Bikuni (Two Nuns) 9

Mōanjō (A Safe Staff for the Blind) 31

Banmin Tokuyō (Right Action for All) 53

Selections from Roankyō (Sayings) Recorded by Echū 75

Kaijō monogatari (On the Sea) A Tale about Shōsan by Echū 199

Footnotes 248PDF: Suzuki Shōsan: Death Energy

Introduction by James W. Heisig

Translation by Royall Tyler

in Japanese Philosophy: a sourcebook

edited by James W. Heisig, Thomas P. Kasulis, John C. Maraldo

University of Hawai‘i Press, Honolulu, 2011. pp. 183-189.

Warrior of Zen: The Diamond-Hard Wisdom Mind of Suzuki Shosan

by Arthur Braverman

Kodansha Globe, 1994

Suzuki Shosan is among the most dramatic personalities on the history of Zen.

A samurai who served under the Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu in the seventeenth

century, he became a Zen monk at age 41 and evolved a highly original

teaching style imbued with the warrior spirit. The warrior's life, Shosan

believed, was particularly suited to Zen study because it demand vitality,

courage, and "death energy," the readiness to confront death at any moment.

Emphasizing dynamic activity over quiet contemplation, Shosan urged

students to realize enlightenment in the midst of their daily tasks, whether

tilling fields, selling wares, or confronting an enemy in the heart of battle.Suzuki Shosan (1467-1568)

Excerpted from Warrior Zen – The Diamond-hard Wisdom Mind of Suzuki Shosan edited by Arthur BravermanOne day the Master said to the assembly: “Nowadays, methods of applying the Buddhist practice are very poor. As a result, everyone says that Buddhism is of no use in the secular world. This is not so. The main point of what I refer to as ‘Society's Three Jewels' is Buddhism's usefulness to society. Were it not, I would be wrong to call it that. In order to make people aware of its meritorious function, I wrote the Meritorious Use of the Three Holy Treasures.

In connection with this, the Master said: “Buddhist practice means subjugation of the six rebellious delusions. This cannot be done with a weak mind. With a firm Dharma-kaya mind, you send forth the soldier of pure faith. And with the sword of the original void, you sever delusions, self-attachment, and greed, wholeheartedly making advances throughout the day.

"Provided you dwell in this diamond mind, applying it even in sleep, it will ripen thoroughly. You will no longer discriminate between inner and outer, and you will fully rout the karmic-generated knowledge-ridden demon soldier. Suddenly you will wake from your dream, destroying the citadel of reality. You will cut down the enemy, birth and death, and residing in the capital of wisdom, protect the peace. This diamond mind is the jewel that functions when a warrior displays valor.

“A second point is that Buddhist practice firmly upholds the precepts and does not act contrary to the teachings of the Buddhas and the patriarchs. It controls the tendency to twist things and corrupt them; therefore, the mind becomes virtuous. Clearly understanding the true Way and the false and transcending the true, you make special use of a meaning beyond discrimination, saving all beings uprightly and with compassion. This Mind, the jewel that makes use of the laws of the realm, practices justice and reason, yet transcends them, clearly distinguishing the true Way from the false. Simply entrust yourself to the manifestations of this Mind and all its actions will be in accordance with the law.

“Third, in Buddhist practice you divorce yourself from personal views and refuse to distinguish between self and others, while making use of the six harmonies. Arriving at the true Mind, you repay the four favors from above and save ordinary beings in the three realms of existence below.

“I wrote about this mind and called it, ‘the mind that makes correct use of the five relationships' because people were saying that Buddhism did not include these relationships. Can you say that a Buddhism that discards the personal self attains a non-discriminating mind, repays the four favors from above, and saves all ordinary beings from below fails to include the five Confucian relationships? All ordinary people, moreover, are considered to be the children of the Buddha. Confucianism, on the other hand, stops at the five relationships.

“As the fourth point in Buddhist practice, you discard the mind that analyzes knowledge, free yourself from attachment to objects, and, arriving at a mind of selflessness, let things happen as they will without any personal intention to be free. This mind is the jewel used by all performing artists. Artists skilled in their trade should know this. Strategists in the art of combat, in particular, should be keenly aware of it.

“The fifth point in Buddhist practice is the destruction of evil passions. Here, the luxury-seeking mind, the flattery-seeking mind, greed, and the fame-and-profit-seeking mind all disappear. I wrote about this mind and called it ‘the jewel used to pass through this life' because people today mistakenly think that Buddhism is of no use to society.

“Buddhism destroys all evil passions. Insofar as evil thoughts disappear, you will continue unobstructed on your journey through this world. People are carelessly extravagant. Thinking they deserve more, they become greedy and destroy themselves. Wherever they go, they find it difficult to survive.

The Master spoke again: “Although I've written about these five stages, it means nothing. I wrote about them because I will die soon, and I wanted to have people understand these teachings thoroughly. But they cannot be applied in this way all at once. It takes many lifetimes of continual practice before you can understand them and make a true vow to apply them in your life. Don't think you will make full use of them in one lifetime or even two. Even though I have thoroughly understood these teachings and clearly grasped the seed, I'm still not able to use it freely. You may discover gold, but if you don't actually take it from the ground, you can't make any use of it.”

Shosan's deepest wishes regarding practice

“The Buddha is infinite grace and perfection. If you practice without aiming at infinite grace, you are not a disciple of the Buddha. Now, without the ripening of your fearless mind, you won't be able to make use of this infinite grace. Infinite grace can be used to the degree that your fearless mind has matured. That's why I hope you will practice with this aim in mind. Using this infinite grace involves detaching yourself from ego.”

--------------------

From the beginning it's best to do zazen in the midst of strife and confusion...

...What use can there be for a zazen requiring a quiet place? However appealing Buddhist teachings may be, the samurai should throw out anything he can't use when the moment for his battle cry arrives. So he never needs anything but the mind of the Nio at all times....

The Nio are the two guardian deities who stand on either side of the temple gate. Each carries a thunderbolt-like weapon that, according to esoteric Buddhism, symbolizes the diamond-hard wisdom mind.

Suzuki Shosan (1467-1568), former warrior turned monk, seized upon the vital energy symbolized by these two ferocious-looking deities; he emphasized it to students, and demonstrated in his person the need to cultivate it in all activities.

Because of its uniqueness, Shosan became associated exclusively with his Nio zazen as though it were the whole of his teaching. But Nio zazen was only one side of this very complex and distinctive Zen master and cannot be understood unless seen as an integral part of Shosan's life and teaching, as we read in the following passages:

Eradication of the "I" is the true Dharma

One day a lay person asked: "I'm told that there are mistaken practitioners and true practitioners. How can we distinguish one from the other?"

The Master responded: "When the 'I' is eradicated, that is the true Dharma. Practitioners of wisdom establish a ‘wise I.' Practitioners of compassion establish a ‘compassionate I.' Practitioners of meditation establish ‘zazen I.' Practitioners of a particular viewpoint establish an ‘I' with that viewpoint. Ordinary people tend to elevate themselves. One is always trying to elevate oneself above others. No matter how humble a person's position, if he upholds the truth, I will step aside for him."

The determination manifest in Buddhist images

This is called attending to everything within your practice.

If you don't train yourself with the determination manifest in Buddhist images, your practice will be no use to you. I've heard that the main image in Unsen is the Four-Faced Bodhisattva. It is an expression of one's complete energy being applied in all directions. The Eleven Headed Kannon manifests this same mind. The quiet repose of the Tathagata also embodies this vital energy, complete in every way. Generally when we move in a particular direction, our vital energy focuses solely in that direction, leaving other directions unattended.

Suzuki Shosan (1467-1568)

Shosan likes to impress upon his students the difficulty and rarity of complete enlightenment. It is with this purpose in mind that he seems to use the symbolism of the many-headed Buddhas and bodhisattvas. They see in all directions while ordinary people see only in one or two or, as Shosan says about himself, three directions. This is another example of Shosan warning his students of the danger of making too much of a small insight.

Suzuki Shosan is among the most dramatic personalities in the history of Zen. A samurai who served under the Shogan in the 17th century, he became a Zen monk at age 41 and evolved a highly original teaching style imbued with the warrior spirit. The warrior's life, Shosan believed, was particularly suited to Zen study because it demanded vitality, courage, and "death energy," the readiness to confront death at any moment. Emphasizing dynamic activity over quiet contemplation, Shosan urged students to realize enlightenment in the midst of their daily tasks.

Death Was His Koan: The Samurai-Zen of Suzuki Shosan

by Winston L. King

Berkeley: Asian Humanities Press, 1986, 395 p.

Winston L. King was ninety-three when he died on February 15, 2000, at his home in Madison, Wisconsin. Diagnosed with cancer over a year ago, he continued many of his usual activities -- reading widely, maintaining a voluminous correspondence, visiting with friends, and walking daily. Winston was one of those remarkable scholar-teachers of an older generation who never ceased to develop new intellectual and research interests. With degrees from Asbury College (A.B., 1929), Andover Newton Theological Seminary (1936), and Harvard (S.T.M., 1938; Ph.D., 1940), his career included pastorates in New England (1930-1943, 1945-1949), Dean of the Chapel and professor of Grinnell College (1949-1963), professor of the history of religions atVanderbilt University (1964-1973), and after his retirement fromVanderbilt, an appointment as professor of philosophy at Colorado State University.

Winston's two-year appointment with the Ford Foundation as the advisor to the International Institute for Buddhistic Studies in Rangoon (Yangon), Burma (Myanmar), from 1958 to 1960 proved to be a major turning point in his life and established his reputation as a significant interpreter of Theravada Buddhism in Southeast [End Page vi] Asia. Three important monographs resulted from Winston's stay in Burma: Buddhism and Christianity: Some Bridges of Understanding (1963), In the Hope of Nibbana: An Essay on Theravada Buddhist Ethics (1964), and AThousand Lives Away (1964). The last volume was the most widely regarded of the three, but each was at the forefront of later developments in the fields of Buddhist-Christian studies, Buddhist ethics, and modern studies in Southeast Buddhism.

Winston was already well grounded in a broad comparative study of religion, as demonstrated by his Introduction to Religion (Harper,1954), before his sojourn in Burma. In the first chapter of that textbook, he set forth an understanding of religion as "unity-in-diversity and diversity-in-unity" that informed his sensibilities as a historian of religions -- especially Buddhism -- throughout his life. He saw being a person of faith as an advantage rather than a disadvantage in the study of religion, anticipating his subsequent work in Buddhist-Christian studies.Winston believed that the adherent of a particular faith is better able "to penetrate to the centrally important features of another religion" that might be opaque to the "nonreligionist." His analogical observation, "Being in love he will know how to understand something of another's being in the same situation" grew out of the deep mutual devotion between Winston and Jocelyn, his beloved wife of more than sixty-six years.

Winston's special interest in Japanese Buddhism began to take shape in the latter part of his career with a Fulbright Lecturership in Kyoto in 1965-1966. Subsequently, he was to return to Japan to continue his study of Buddhism and Japanese language at sixty years of age. Several articles and two major monographs followed: Death Was His Koan: The Samurai-Zen of Suzuki Shosan (1986) and Zen and the Way of the Sword (1993).

Throughout his career, Winston maintained a strong interest in the practice of faith, giving both personal and scholarly attention to Buddhist meditation in particular. While he was in Burma, he spent ten days at the International Meditation Center founded by U Ba Khin. An account of his experience appeared in the Journal of Religion (1961). In Buddhism and Christianity, he compared Christian prayer and Buddhist meditation; later he was to compare Theravada and Zen meditational methods and goals (History of Religions, 1970) and explore the yogic methodological background to Buddhist insight meditation ( Theravada Meditation: The Buddhist Transformation ofYoga, 1980).

Winston's empathetic approach to religious understanding, his scholarly breadth and productivity, and his humane, personal integrity set a standard to be emulated by those who follow him. We celebrate his life and his scholarship.

Donald K. Swearer

Cf.

今井福山 Imai Fukuzan

湘南葛藤録 Shōnan kattōroku

100 kōans, compiled by 無隠 Muin of 禅興寺 Zenkō-ji (Kamakura) in 1545; reedited by 今井福山 Imai Fukuzan (1925)

PDF: The warrior kōans

Translated by Trevor Leggett (1914-2000)

Cf.

The Religion of the Samurai

A Study of Zen Philosophy and Discipline in China and Japan

by Kaiten Nukariya

[1913]

![]()

Cf.

STEVENS, John:

Jamaoka Tessu : A ”kard nélküli iskola” megalapítójának élete

Ford. Tóth Andrea. Budapest : Szenzár Kiadó, 2005. Japán kardvívó mesterei.

(The Sword of No-Sword : Life of the Master Warrior Tesshu). 225 p.

Yamaoka Tesshū (山岡 鉄舟) kiemelkedő alakja volt annak a viharos időszaknak, amelyben egy új Japán született. A közéletben Tessu Szaigo Takamorival tárgyalt, és előkészítette a sógunátus utáni békés hatalomváltást. Az Út egyéni követőjeként negyvenöt évesen mély megvilágosodást ért el, és felismerte a kardvívás, a zen és a kalligráfia belső alapelveit. Ettől fogva Tessu olyan volt, mint Mijamoto Muszasi: "... úgy telik az életem, hogy nem egy meghatározott Utat követek". (Az öt elem könyve)

Tessu is kiemelkedően sokoldalú és termékeny mesterré vált: egyedülálló kardvívó, aki a Kardnélküli Iskolát megalapította; a Tekiszui hagyomány szerinti bölcs és könyörületes zen tanító; páratlan kalligráfus, aki ecsetével fejezte ki az ég és a föld összes tanítását. Még ma is, több mint egy évszázaddal a halála után, ecsettel készült műveiben érzékelhetjük Tessu hihetetlen életerejét. Ha helyesen értelmezzük kalligráfiáit, teljesen szembetűnő az a nagy átváltozás, ami Tessu megvilágosodásával együtt járt és az az egyre mélyülő éleslátás, ami életének utolsó nyolc évében tapasztalható.

TARTALOMJEGYZÉK

Előszó

Bevezetés

A szerző megjegyzése

I. Tessu élete és kora

II. A kardnélküli vívás

III. A nagy megvilágosodás

IV. A felszálló sárkány

V. A három su

VI. Tessu írásai

Cf.

Szugavara Makoto

Japán kardvívó mesterei

Szenzár Kiadó, 248 oldal

A kengó olyan személy volt, akinek kardvívó tehetségét elismerte a nép - nem léteztek tárgyilagos ismertetőjegyek arra, hogy valaki méltó legyen a kengó elnevezés elnyerésére. Ehhez a megszólításhoz az kellett, hogy egy nevezetes kardforgató legyőzésével szerezzenek maguknak hírnevet. Az elismerés elnyerésének különböző módjai léteztek, de valójában az összes kengó valamikor az országot járta, hogy párbajok során tökéletesítse vívótehetségét.

Azok, akik utazásaik során tökéletes magabiztosságra tettek szert a harci tudás terén, megalapították saját iskolájukat. A kengók számos tanítványukkal együtt dódzsókat hoztak létre, hogy ott oktathassák az újonnan alapított iskola tudását. Felesleges mondanunk, hogy minden új iskola megalapítója maga választotta ki utódját. Az Edo-korszak végére (1867) több mint hétszáz ilyen harcművészeti iskola létezett.

Ebből arra következtethetünk, hogy a Tokugava-sógunátus alatt rengeteg kardforgató mester élt Japánban. Közülük választottam ki most néhányat - Cukahara Bokuden, a Jagjúk, Jamaoka Tessu stb. - akikről viszonylag jelentős történelmi anyagot találtam, és amennyire csak lehetett, ezek alapján írtam meg életük történetét.

TARTALOMJEGYZÉK

Japán elöljáróságai - Előszó

I. Cukahara Bokuden

II. Kamiizumi Nobucuna

III. Jagjú Munejosi

IV. Jagjú Munenori

V. Jagjú Micujosi

VI. Itó Ittószai Kagehisza

VII. Ono Tadaaki

VIII. Az utolsó nagy kardvívók

Utószó: A kard útja a modern világban (John Stevens)

Irodalomjegyzék