ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

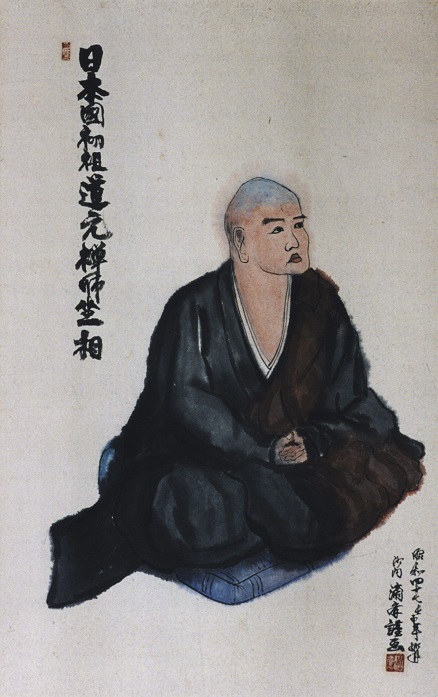

.[永平] 道元希玄 [Eihei] Dōgen Kigen (1200–1253)

Tartalom |

Contents |

Végh József: PDF: Dógen Zen mester magyarul elérhető írásai Hrabovszky Dóra: Fukan-zazen-gi A zazen dicsérete Az ülő meditáció szabályai (Sóbógenzó zazengi) A zazen ösvénye A szívében a megvilágosodás szellemével élő lény (bódhiszattva) négy irányadó tevékenysége Életünk kérdése (Gendzsókóan 現成公案) PDF: Az Út Gyakorlásában Követendő pontok |

真字正法眼蔵 [Mana/Shinji] Shōbōgenzō 仮字正法眼蔵 [Kana/Kaji] Shōbōgenzō 普勧坐禅儀 Fukan zazengi 学道用心集 Gakudō-yōjinshū Advice on Studying the Way 永平清規 Eihei shingi Eihei Rules of Purity 永平廣錄 Eihei kōroku Dōgen's Extensive Record 宝慶記 Hōkyō-ki Memoirs of the Hōkyō Period 傘松道詠 Sanshō dōei Verses on the Way from Sanshō Peak

孤雲懷奘 Kōun Ejō (1198-1280) 修證義 Shushō-gi, compiled in 1890 Kōshō-ji PDF: The Life of Dōgen Zenji |

典座 教訓 Tenzo kyōkun

Instructions for the Tenzo

Translated by Anzan Hoshin roshi and Yasuda Joshu Dainen roshi

[published in "Cooking Zen", Great Matter Publications, 1996]

> DOC

From ancient times communities of the practice of the Way of Awake Awareness have had six office holders 1 who, as disciples of the Buddha, guide the activities of Awakening 2 the community. Amongst these, the tenzo bears the responsibility of caring for the community's meals. The Zen Monastic Standards 3 states, "The tenzo functions as the one who makes offerings with reverence to the monks."

Since ancient times this office has been held by realized monks who have the mind of the Way 4 or by senior disciples who have roused the Way-seeking mind. 5 This work requires exerting the Way. 6 Those entrusted with this work but who lack the Way-seeking mind will only cause and endure hardship despite all their efforts. The Zen Monastic Standards states, "Putting the mind of the Way to work, serve carefully varied meals appropriate to each occasion and thus allow everyone to practice without hindrance." 7

In times past such great masters as Guishan Lingyou, 8 Dongshan Shouchu, 9 and others have served in this post. Although this is a matter of preparing and serving meals, the tenzo is not just "the cook." 10

When I was in Song China , during spare moments I enquired of many elder monks who had served in the various offices 11 about their experience. Their words to me were from the bone and marrow 12 of the Awakened Ancestors who, having attained the Way, have passed it through the ages. We should carefully study the Zen Monastic Standards to understand the responsibility of the tenzo and also carefully consider the words of these senior monks.

The cycle of one day and night begins following the noon meal. 13 At this time the tenzo should go to the administrator and assistant administrator 14 and procure the rice, vegetables, and other ingredients for the next day's morning 15 and noon meals. Having received these things, you must care for them as you would the pupils of your own eyes. 16 Thus Zen Master Baoning Renyong 17 said, "Care for the monastery's materials 18 as if they were your eyes." The tenzo handles all food with respect, as if it were for the emperor; both cooked and uncooked food should be cared for in this way.

Following this, all of the officers gather in the kitchen building in order to carefully consider the next day's meals with regard to flavourings, vegetables to be used, and the kind of rice-gruel. The Zen Monastic Standards states, "In deciding the morning and noon meals, the amount of food and number of dishes, the tenzo should consult the other officers. The six officers are the administrator, assistant administrator, treasurer, disciplinarian, tenzo, and head caretaker. After the menu is decided post it on boards by the abbot's residence 19 and the study hall." 20 Following this the morning gruel may be prepared.

Do not just leave washing the rice or preparing the vegetables to others but use your own hands, your own eyes, your own sincerity. Do not fragment your attention 21 but see what each moment calls for; 22 if you take care of just one thing then you will be careless of the other. Do not miss the opportunity of offering even a single drop into the ocean of merit or a grain atop the mountain of the roots of beneficial activity. 23

The Zen Monastic Standards states, "If the six flavours 24 are not in harmony and three virtues 25 are lacking, then the tenzo is not truly serving the community."

Be careful of sand when you wash the rice, be careful of the rice when you throw out the sand. Take continuous care and the three virtues will be naturally complete and the six flavours harmonious.

Xuefeng 26 once practiced as tenzo under Zen Master Dongshan. 27 Once when he was washing rice, Dongshan said, "Do you wash the sand away from the rice, or the rice away from the sand?"

Xuefeng said, "I wash them both away together."

Dongshan said, "Then what will the community eat?"

Xuefeng overturned the washing bowl.

Dongshan said, "You should go and study with someone else. Soon." 28

Senior students, from ancient times, always practiced with the mind which finds the Way and so how can we of later generations not do the same? Those of old tell us, "For the tenzo, the mind which finds the Way actualizes itself through working with rolled up sleeves." 29

You yourself should examine the rice and sand so that rice is not thrown out with sand. The Zen Monastic Standards states, "In preparing the food, the tenzo is responsible for examining it to ensure that it is clean." Do not waste grains of rice when draining off the rinsing water. In olden times a cloth bag was used as a filter when draining the rinse water. When the rice is placed in the iron cooking pot, take care of it so that rats do not fall into it or idlers just hang around poking at it.

After cooking the vegetables for the morning meal and before preparing rice and soup for the noon meal bring together the rice pots and other utensils and make sure that everything is well-ordered and clean. Put whatever goes to a high place in a high place and whatever goes to a low place in a low place so that, high and low, everything settles in the place appropriate for it. 30 Chopsticks for vegetables, ladles, and all other tools should be chosen with great care, cleaned thoroughly, and placed well.

After this, begin work on the coming day's meals. Remove any weevils, lentils, husks, sand, and pebbles carefully. While you are selecting the rice and vegetables, the tenzo's assistants should chant the sutras to the shining being of the hearth. 31 When preparing the vegetables or ingredients for the soup which have been received from the office 32 do not disparage the quantity or quality but instead handle everything with great care. Do not despair or complain about the quantity of the materials. Throughout the day and night, practice the coming and going of things as arising in the mind, the mind turning and displaying itself as things.

Put together the ingredients for the morning meal before midnight and begin cooking after midnight. 33 After the morning meal, clean the rice cooking pots and soup pots for the noon meal. The tenzo should always be present at the sink when the rice is being soaked and the water measured. Watching with clear eyes, ensure that not a single grain is wasted. Washing it well, place it in the pots, make a fire, and boil it. An old teacher said, "Regard the cooking pot as your own head, the water your own life-blood." Place the cooked rice in bamboo baskets in summer and wooden serving buckets in winter and set these out on trays. While the rice is boiling, cook the soup and vegetables.

The tenzo supervises this personally. This is true whether the tenzo works alone or has assistants to tend the fire or prepare the utensils. Recently, Zen monasteries have developed positions such as rice-cook and soup-cook 34 who work under the tenzo. The tenzo is always responsible for whatever is done. In olden times the tenzo did everything without any assistance.

In preparing food never view it from the perspective of usual mind or on the basis of feeling-tones. Taking up a blade of grass erect magnificent monasteries, 35 turn the Wheel of Reality within a grain of dust. If you only have wild grasses with which to make a broth, do not disdain them. If you have ingredients for a creamy soup do not be delighted. Where there is no attachment, there can be no aversion. Do not be careless with poor ingredients and do not depend on fine ingredients to do your work for you but work with everything with the same sincerity. If you do not do so then it is like changing your behaviour according to the status of the person you meet; this is not how a student of the Way is.

Strengthen your resolve and work whole-heartedly to surpass the monks of old and be even more thorough than those who have come before you. Do this by trying to make as fine a soup for a few cents 36 as the ancients could make a coarse broth for the same amount.

The difficulty is that present and the past are separated by a gulf as great as between sky and earth and no one now can be compared to those of ancient times. However, through complete practice of seeing the nature of things 37 you will be able to find a way. If this isn't clear to you it is because your thoughts speed about like a wild horse and feeling-tones careen about like a monkey in the trees. Let the monkey and horse step back and be seen clearly and the gap is closed naturally. 38 In this way, turn things while being turned by them. Clarify and harmonize your life without losing the single Eye which sees the context or the two eyes which recognize the details. 39

Taking up a vegetable leaf manifests the Buddha's sixteen-foot golden body; 40 take up the sixteen-foot golden body and display it as a vegetable leaf. This is the power of functioning freely as the awakening activity which benefits all beings.

Having prepared the food, put everything where it belongs. Do not miss any detail. When the drum sounds or the bells are struck, follow the assembly for morning zazen and in the evening 41 go to the Master's quarters to receive teachings. When you return to the kitchen, 42 count the number of monks present in the Monks' Hall; 43 try closing your eyes. Don't forget about the senior monks and retired elders in their own quarters or those who are sick. Take into account any new arrivals in the entry hall 44 or anyone who is on leave. Don't forget anyone. If you have any questions consult the officers, the heads of the various halls, or the head monk.

When this is done, calculate just how much food to prepare: for each grain of rice needed, supply one grain. One portion can be divided into two halves, or into thirds or fourths. If two people tend to each want a half-serving, then count this as the quantity for a single full serving. You must know the difference that adding or subtracting one serving would make to the whole.

If the assembly eats one grain of rice from Luling, 45 the tenzo is the monk Guishan. 46 In serving a grain of that rice, the tenzo sees the assembly become the ox. The ox swallows Guishan. Guishan herds the ox.

Are your measurements right or are they off? Have those you consulted been correct in their counting? Review this as best as you can and then direct the kitchen accordingly. This practice of effort after effort, day after day, should not be forgotten.

When a patron visits the monastery and makes a donation for the noon meal, discuss this with the other officers. This is the tradition of Zen monasteries. Other offerings to be distributed should also be discussed with the other officers. In this way, the responsibilities of others are not disrupted nor your own neglected.

When the meal is ready and set out on trays, at noon and morning put on the wrap robe, 47 spread your bowing mat, 48 offer incense and do nine great bows in the direction of the Monks' Hall. When this is done, send out the food.

Day and night, the work for preparing the meals must be done without wasting a moment. If you do this and everything that you do whole-heartedly, this nourishes the seeds of Awakening and brings ease and joy to the practice of the community.

Although the Buddha's Teachings have been heard for a long time in Japan , I have never heard of any one speaking or writing about how food should be prepared within the monastic community as an expression of the Teachings, let alone such details as offering nine bows before sending forth the food. As a consequence, we Japanese have taken no more consideration of how food should be prepared in a monastic context than have birds or animals. This is cause for regret, especially since there is no reason for this to be so.

When I was staying at Tiantong-jingde-si, 49 a monk named Lu from Qingyuan fu 50 held the post of tenzo. Once, following the noon meal I was walking along the eastern covered walkway towards a sub-temple called Chaoran Hut 51 when I came upon him in front of the Buddha Hall 52 drying mushrooms in the sun. He had a bamboo stick in his hand and no hat covering his head. The heat of the sun was blazing on the paving stones. It looked very painful; his back was bent like a bow and his eyebrows were as white as the feathers of a crane. I went up to the tenzo and asked, "How long have you been a monk?"

"Sixty-eight years," he said.

"Why don't you have an assistant do this for you?"

"Other people are not me."

"Venerable sir, I can see how you follow the Way 53 through your work. But still, why do this now when the sun is so hot?"

"If not now, when?"

There was nothing else to say. As I continued on my way along the eastern corridor I was moved by how important the work of the tenzo is.

In May of 1223 54 I was staying aboard the ship at Qingyuan. Once I was speaking with the captain when a monk about sixty years of age came aboard to buy mushrooms from the ships Japanese merchants. I asked him to have tea with me and asked where he was from. He was the tenzo from Ayuwang shan. 55

He said, "I come from Xishu 56 but it is now forty years since I've left there and I am now sixty-one. I have practiced in several monasteries. When the Venerable Daoquan became abbot at Guyun temple 57 of Ayuwang I went there but just idled the time away, not knowing what I was doing. 58 Fortunately, I was appointed tenzo last year when the summer Training Period ended. 59 Tomorrow is May 5th 60 but I don't have anything special offerings for the monks so I thought I'd make a nice noodle soup for them. We didn't have any mushrooms so I came here to give the monks something from the ten directions."

"When did you leave Ayuwangshan?" I asked.

"After the noon meal."

"How far is it from here?"

"Around twelve miles." 61

"When are you going back to the monastery?"

"As soon as I've bought the mushrooms."

I said, "As we have had the unexpected opportunity to meet and talk like this today, I would like you to stay a while longer and allow me to offer Zen Master tenzo a meal."

"Oh, I'm sorry, but I just can't. If I am not there to prepare tomorrow's meal it won't go well."

"But surely someone else in the monastery knows how to cook? If you're not there it can't make that much difference to everyone."

"I have been given this responsibility in my old age and it is this old man's practice. How can I leave to others what I should do myself? As well, when I left I didn't ask for permission to be gone overnight."

"Venerable sir, why put yourself to the difficulty of working as a cook in your old age? Why not just do zazen and study the koan of the ancient masters?"

The tenzo laughed for a long time and then he said, "My foreign friend, it seems you don't really understand practice or the words 62 of the ancients."

Hearing this elder monk's words I felt ashamed and surprised. I asked, "What is practice? What are words?"

The tenzo said, "Keep asking and penetrate this question and then you will be someone who understands."

But I didn't know what he was talking about and so the tenzo said, "If you don't understand then come and see me at Ayuwang shan some time. We'll talk about the meaning of words." Having said this, he stood up and said, "It'll be getting dark soon. I'd best hurry." And he left.

In July of the same year I was staying 63 at Tiantongshan when the tenzo of Ayuwang shan came to see me and said, "After the summer Training Period is over I'm going to retire as tenzo and go back to my native region. I heard from a fellow monk that you were here and so I came to see how you were making out."

I was overjoyed. I served him tea as we sat down to talk. When I brought up our discussion on the ship about words and practice, the tenzo said, "If you want to understand words you must look into what words are. If you want to practice, you must understand what practice is."

I asked, "What are words?"

The tenzo said, "One, two, three, four, five."

I asked again, "What is practice?"

"Everywhere, nothing is hidden." 64

We talked about many other things but I won't go into that now. Suffice it to say that without this tenzo's kind help I would not have had any understanding of words or of practice. When I told my late teacher Myozen 65 about this he was very pleased.

Later I found a verse that Xuedou 66 wrote for a disciple:

One, seven, three, five.

What you search for cannot be grasped.

As the night deepens,

the moon brightens over the ocean.

The black dragon's jewel

is found in every wave.

Looking for the moon,

it is here in this wave

and the next.

What the tenzo said is expressed here in Xuedou's verse as well. Then it was even clearer to me that the tenzo was truly a person of the Way.

Before I knew one, two three, four, five; now I know six, seven, eight, nine, ten. Monks, you and those to follow must understand practice and words through this and from that. Exert yourself in this way and you will practice the single true taste of Zen beyond words, 67 undivided into the poisonous five flavours. 68 Then you will be able to prepare food for the monastic community properly.

There are many old stories we can hear and present examples of monks training as tenzo. A great many teachings concern this because it is the heart of the Way.

Even if you become the Abbot of a monastery, you should have this same understanding. The Zen Monastic Standards states, "Prepare each meal with each detail kept clear so that there will be enough. Make sure that the four offerings of food, clothing, bedding, and medicine 69 are adequate just as the Generous One offered to his disciples the merit of twenty years of his lifetime. We ourselves live today within the light of that gift because the energy of even a white hair between his brows 70 is inexhaustible." It also says, "Just think about how to best serve the assembly without being hindered by thoughts of povertyy. If your mind is limitless, you enjoy limitlessness." This is how the abbot serves the assembly.

In preparing food, it is essential to be sincere and to respect each ingredient regardless of how coarse or fine it is. There is the example of the old woman who gained great merit through offering water in which she had rinsed rice to the Thus Come. 71 And of King Asoka creating roots of wholesomeness through offering half a mango to a monastery as he lay dying. 72 As a result of this he realized the deathless in his next life. Even the grandest offering to the Buddha, if insincere, is worth less than the smallest sincere offering in bringing about a connection with awakening. 73 This is how human beings should conduct themselves.

A rich buttery soup 74 is not better as such than a broth of wild herbs. 75 In handling and preparing wild herbs, do so as you would the ingredients for a rich feast, wholeheartedly, sincerely, clearly. When you serve the monastic assembly, they and you should taste only the flavour of the Ocean of Reality , the Ocean of unobscured Awake Awareness, not whether or not the soup is creamy or made only of wild herbs. In nourishing the seeds of living in the Way rich food and wild grass are not separate. There is the old saying, "The mouth of a monk is like a furnace." 76 Bear this in mind. Wild grasses can nourish the seeds of Buddha 77 and bring forth the buds of the Way. 78 Do not regard them lightly. A teacher must be able to use a blade of wild grass to benefit humans and shining beings.

Do not discriminate between the faults or virtues of the monks or whether they are senior or junior. You do not even know where you stand, so how can you put others into categories. Judging others from within the boundaries of your own opinions, how could you be anything other than wrong? Although there are differences between seniors and juniors, all are equally members of the assembly. 79 Those who had many faults yesterday may be correct and clear today. Who can judge "sacred" from "common." The Zen Monastic Standards states, "Whether foolish or wise, the fact that one trains as a monk provides for others a gift that penetrates everywhere."

If you stand beyond opinions of right and wrong, you bring forth the practice of actualizing unsurpassable Awakening. If you do not, you take a wrong step and miss what's there. 80 The bones and marrow of the ancients was just the exertion of such practice and those monks who train as tenzo in the future realize the bones and marrow of the Way only through just such exertion. The monastic rules set forth by great Master Baizhang 81 must always be maintained.

After I returned to Japan I stayed at Kennin-ji 82 for around two years. They had the office of tenzo there but it was only nominal because no one actually carried out the real activity of this training post. They did not understand it as the activity of Awake Awareness so how could they have been able to use it to express the Way? Truly, it was very sad. The tenzo there had never encountered a living one who could use the office of tenzo as the functioning of Awake Awareness and so he carelessly idled away, breaking the standards of practice.

I watched the tenzo there quite closely. He never actually worked at preparing the morning and evening meals but just ordered about some rough servants, lacking in intelligence and heart, leaving to them all the tasks whether important or not. He never checked on whether they were working well or not, as if it would be shameful to do so like peeping into the private quarters of a neighbouring woman. He just hung about in his own rooms, reading sutras or chanting when he wasn't lying down or chatting. Months would go by before he would even come close to a pot, let alone buy utensils or make out a menu. He did not understand that these activities are the exertion of Awareness. The practice of donning the wrap robe and offering nine bows before sending out the food was something he would never have even dreamed of; it just wouldn't have occurred to him. As he himself did not understand the office of tenzo, when it came time for him to teach a novice 83 how to carry out the office what understanding could be passed on? It was very regrettable. Although one might have the fortune to hold this post, if one is without the mind which uncovers the Way and fails to meet with one who has the virtue of the Way, it is like returning empty-handed after climbing a mountain of treasure or entering an ocean of jewels.

Although you might not have the mind which uncovers the Way, if you meet one manifesting the True Person 84 you can then practice and unfold the Way. Or, even if you cannot meet with one who is the display of the True Person, by yourself deeply arousing the seeking for the Way, you can begin the Way. If you lack both of these, what is the point?

In the many monasteries of the mountains of Song China that I have seen, the monks holding the various offices train in these posts for a year at a time, each of them in each moment practicing by three standards. Firstly, to benefit others benefits yourself. Second, make every effort to maintain and renew the monastic environment. Third, follow the standards set forth by the examples of excellent practitioners of past and present and come to stand with them.

You should understand that foolish people hold their practice as if it belonged to someone else, wise people practice with everyone as themselves.

An ancient teacher 85 said,

Two-thirds of your life has passed

without clarifying who you are.

Eating your life,

muddling about in this and that,

you don't even turn when called on.

Pathetic.

From this verse we can see that if you have not met a true teacher, you will just follow the lead of your tendencies. And this is pathetic. It's like the story of the foolish son who leaves his parent's home with the family treasure and then throws it away on a dung heap. 86 Do not waste your opportunity as that man did.

Considering those who in the past made good use of their training as tenzo, we can see that their virtues were equal to those of their office. The great Daigu 87 woke up while training as tenzo and Dongshan Shouchou's "Three pounds of flax," occurred while he was tenzo. 88 The only thing of value is the realization of the Way, the only time that is precious is each moment of realizing the Way.

Examples of those who long for the Way are many. There is the story of a child offering the Buddha a handful of sand as a great treasure. 89 Another is of someone who made images of the Buddha and had reverence for them and thus had great benefit follow them. 90 How much more benefit must there be in fulfilling the office of tenzo through actualizing its possibilities as have those excellent ones who have practiced before us?

When we train in any of the offices of the monastery we should do so with a joyful heart, a motherly heart, a vast heart. 91 A "joyful heart" rejoices and recognizes meaning. You should consider that were you to be born in the realm of the shining beings you would be absorbed in indulgence with the qualities of that realm so that you would not rouse the recognition of uncovering the Way and so have no opportunity to practice. And so how could you use cooking as an offering to the Three Jewels? Nothing is more excellent than the Three Jewels of the Buddha, the Teachings, and the Community of those who practice and realize the Way. Neither being the king of gods 92 nor a world ruler 93 can even compare with the Three Jewels.

The Zen Monastic Standards states, "The monastic community is the most excellent of all things because those who live thus live beyond the narrowness of social fabrications." Not only do we have the fortune of being born as human beings but also of being able to cook meals to be offered to the Three Jewels. We should rejoice and be grateful for this.

We can also reflect on how our lives would be were we to have been born in the realms of hell beings, hungry ghosts, animals, or jealous gods. 94 How difficult our lives would be in those four situations or if we had been born in any of the eight adverse conditions. 95 We would not then be able to practice together with the strength of a monastic community even should it occur to us to aspire to it, let alone be able to offer food to the Three Jewels with our own hands. Instead our bodies and minds would be bound within the limits of those circumstances, merely vessels of contraction.

This life we live is a life of rejoicing, this body a body of joy which can be used to present offerings to the Three Jewels. It arises through the merits of eons and using it thus its merit extends endlessly. I hope that you will work and cook in this way, using this body which is the fruition of thousands of lifetimes and births to create limitless benefit for numberless beings. To understand this opportunity is a joyous heart because even if you had been born a ruler of the world the merit of your actions would merely disperse like foam, like sparks.

A "motherly heart" is a heart which maintains the Three Jewels as a parent cares for a child. A parent raises a child with deep love, regardless of poverty or difficulties. Their hearts cannot be understood by another; only a parent can understand it. A parent protects their child from heat or cold before worrying about whether they themselves are hot or cold. This kind of care can only be understood by those who have given rise to it and realized only by those who practice it. This, brought to its fullest, is how you must care for water and rice, as though they were your own children.

The Great Master Sakyamuni offered to us the final twenty years of his own lifetime to protect us through these days of decline. 96 What is this other than the exertion of this "parental heart"? The Thus Come One did not do this hoping to get something out of it but sheerly out of munificence.

"Vast heart" is like a great expanse of ocean or a towering mountain. It views everything from the most inclusive and broadest perspective. This vast heart does not regard a gram as too light or five kilos as too heavy. It does not follow the sounds of spring or try to nest in a spring garden; it does not darken with the colours of autumn. See the changes of the seasons as all one movement, understand light and heavy 97 in relation to each other within a view which includes both. When you write or study the character "vast," 98 this is how you should understand its meaning.

If the tenzo at Jiashan had not thus studied the word "vast," he could not have woken up Elder Fu by laughing at him. 99 If Zen Master Guishan had not understand the word "vast," he would not have blown on dead firewood three times. 100 If the monk Dongshan had not understood the word "vast," he could not have taught the monk through his expression, "Three pounds of flax." 101

All of these and other great masters through the ages have studied the meaning of "vast" or "great" not only though the word for it but through all of the events and activities of their lives. 102 Thus they lived as a great shout of freedom through presenting the Great Matter, penetrating the Great Question, training great disciples and in this way bringing it all forth to us.

The abbot, senior officers and staff, and all monks should always maintain these three hearts or understandings.

Written in the spring of 1237 103 for those of coming generations who will practice the Way by Dogen, abbot of Kosho-(Horin-)ji.

Sleeves Tied Back

Commentaries on Dogen zenji's Tenzo kyokun

by Ven. Anzan Hoshin roshi

Vanier Zendo, October-November 1986

transcribed and edited by Ven. Jinmyo Renge osho-ajari

http://wwzc.org/dharma-text/sleeves-tied-back

These three classes were presented in 1986 by Roshi following zazen at the Vanier Zendo, the White Wind Zen Community's second centre. The classes were very informal so they should not be regarded as teisho. Anzan roshi was still working on a draft of the translation of "Tenzo kyokun: Instructions For the Tenzo" that he had done with Joshu Dainen zenji and so he used the translation published in "Moon in a Dewdrop" edited by Kazuaki Tanahashi. Had he been working from his own finished text, the classes would no doubt have been quite different. I have edited the text by inserting Roshi's translation which was published together with Dogen zenji's "Fushukuhanpo: How to Use Your Bowls" in 1996 as "Cooking Zen."

Ven. Jinmyo Renge osho-ajari

Dainen-ji, February 23, 2004

Cf.

Eihei Shingi

Instructions for the Cook (Tenzo kyôkun)

Translated by Griffith Foulk

PDF: How to Cook Your Life

From the Zen Kitchen to Enlightenment

Zen Master Dogen and Kosho Uchiyama. Translated by Thomas Wright

PDF: Dōgen's Pure Standards for the Zen Community

Translated by Taigen Dan Leighton and Shohaku Okumura

State University of New York Press, 1996

PDF: Instructions to the cook: a Zen master's lessons in living a life that matters

by Bernard Glassman and Rick Fields

Zen Master Dōgen's Monastic Regulations

Translated by by Ichimura Shohei

North American Institute of Zen and Buddhist Studies, 1993