ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

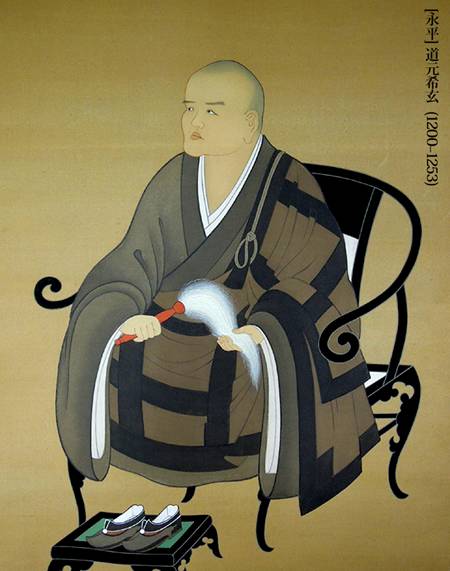

[永平] 道元希玄 [Eihei] Dōgen Kigen (1200–1253)

Tartalom |

Contents |

Végh József: PDF: Dógen Zen mester magyarul elérhető írásai Hrabovszky Dóra: Fukan-zazen-gi A zazen dicsérete Az ülő meditáció szabályai (Sóbógenzó zazengi) A zazen ösvénye A szívében a megvilágosodás szellemével élő lény (bódhiszattva) négy irányadó tevékenysége Életünk kérdése (Gendzsókóan 現成公案) PDF: Az Út Gyakorlásában Követendő pontok |

真字正法眼蔵 [Mana/Shinji] Shōbōgenzō 仮字正法眼蔵 [Kana/Kaji] Shōbōgenzō 普勧坐禅儀 Fukan zazengi 学道用心集 Gakudō-yōjinshū Advice on Studying the Way 永平清規 Eihei shingi Eihei Rules of Purity 永平廣錄 Eihei kōroku Dōgen's Extensive Record 宝慶記 Hōkyō-ki Memoirs of the Hōkyō Period 傘松道詠 Sanshō dōei Verses on the Way from Sanshō Peak

孤雲懷奘 Kōun Ejō (1198-1280) 修證義 Shushō-gi, compiled in 1890 Kōshō-ji PDF: The Life of Dōgen Zenji |

正法眼藏

Shōbōgenzō

Chapters

of the Shôbôgenzô

Translated by Thomas Cleary

From the 75-fascicle redaction1. 現成公案 Genjô kôan

2. 摩訶般若波羅蜜 Maka hannya haramitsu

22. 全機 Zenki

48. Hosshô

2.

Makahannyaharamitsu

Great

Transcendent Wisdom

by Eihei Dogen

Translated by Thomas

Cleary

The subject of this

essay, mahaprajnaparamita in Sanskrit, is the general title and essential theme

of one of the major groups of Buddhist scriptures, and is one of the most important

issues in Buddhism. Sanskrit maha, meaning "great," conveys the notion

of universality. Prajna, often translated as "wisdom," might be rendered

as inteuse knowledge; it is commonly described as knowledge of the true nature

of things, as being "empty" or lacking absolute, independent existence.

Paramita means "reached the other shore" or "reached the ultimate,"

and connotes transcendence of mundane limitations, the "other shore"

referring to liberation of the mind.

Thus "great transcendent wisdom;' as wc read it here, means transcendence by universal intense knowledge. The Treatise on Great Transcendent Wisdom, a classic work on this teaching, says, "All things are subject to causes and conditions, none are independent. . . . All are born from causes and conditions, and because of this they have no intrinsic nature of their own. Because of having no intrinsic nature, they are ultimately empty. Not clinging to them because they are ultimately empty is called transcendent wisdom."

From this it can be seen that knowledge of "emptiness" is knowledge of conditionality: emptiness, being the aabsence of independence or own being of conditional things, is not apart frcom the conditiomal. This includes all things, whether concrete or abstract, even the items of the Buddhist teachings. Hence transcendent wisdom is that whereby the world, including even the doctrines and means of Buddhism, is transcended, so that there is no clinging to anything. According to Buddhist philosophy, clinging is a prirne source of delusion, whether that clinging be to "profane" or "sacred" things. Therefore realization of the relativity, or nonabsoluteness, of all things is at the core of freedom and enlightenment as proposed by Mahayana Buddhism.

However, if it is because of relativity, or conditionality, that all things are "empty," it is equally true that by the very same conditionality they do exist dependently. The tendency to misinterpret "emptiness" nihilistically, whether by intellectual misunderstanding or by mistaking concentration states for insight, is well known and often mentioned in Buddhist texts, especially texts of the Zen schools, where, perhaps due in part to overemphasis on concentration, it seems to have been a not uncommon problem. A thorough reading of Dogen's Shobogenzo will reveal that correcting or preventing the tendency toward nihilistic interpretation of emptiness is a major concern of Dogen's teaching. In this essay, Dogen identifies phenomema themselves with transcendent wisdom, emphasizing that within so-called nothing or emptiness all things are found, including the facilities, or means, of the Buddhist teachings.

The image Dogen uses for the realization of wisdom is that of space. As Dogen says, "Learning wisdom is space, space is learning wisdom." As a common Zen metaphor for the open mind, space may be said to contain all things without being affected by them. The spacelike mind thus is to be distinguished from the mind which is, as it were, in space, the former being the nongrasping, nonrejecting openness traditionally preached by Zen, the latter being a concentration state, often practiced by those who seek tranquility and detachrnent alone. Dogen here presents the "middle way" in which the emptiness and existence of all things are simultaneously realized, the centerpoint, the balance, of Mahayana Buddhism.

Much of the essay consists of extracts from Buddhist scripture, and a number of technical terms are brought up. It is not imperative to know exactly what these terms refer to in order to understand the essence of the message, for they refer to Buddhist doctrines, practices, and descriptions as part of the totality of phenomena which all exist yet are empty, are empty yet exist. For the sake of conveniencc, definitions are provided in a glossary appended to the essay.

Great Transcendent Wisdom

The time when the Independent Seer practices profound transcendent wisdom is the whole body's clear vision that the five clusters are all empty. The five clusters are physical form, scnsations, perceptions, conditionings, and consciousness. They are five layers of wisdom. Clear vision is wisdom.

In expounding and manifesting this fundamental message, we would say form is empty, emptiness is form, form is form, emptiness is empty. It is the hundred grasses, it is myriad forms.

Twelve layers of wisdom are the twelve sense-media. There is also eighteen-layer wisdom- eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, intellect, form, sound, smell, taste, touch, phenomena, as well as the consciousness of the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and intellect. There is also four layered wisdom, wich is suffering, its accumulation, its extinction, and the path to its extinction. Also there is six-layered wisdom, which is charity, morality, forbearance, vigor, meditation, and wisdom. There is also one-layer wisdom, which is manifest in the immediate present, which is uncxcelled complete perfect enlightentnent. There are also three layers of wisdom, which are past, present, and future. There are also six layers of wisdom, which are earth, water, fire, air, space, and consciousness. Also, four-layered wisdom is constantly being carried out- it is walking, standing, sitting, and reclining.

In the assembly of Shakyamuni Buddha was a monk who thought to himself, "I should pay obeisance to most profound transcenclent wisdom. Though there is no corigination or extinction of phencnnena herein, yet there are available facilitics of bodies of precepts, meditation, wisdom, liberation, and knowledge and insight of liberntion. Also there are available facilities of the fruit of the stream-enterer, the fruit of the once-returner, the fruit of the norrreturner, and the fruit of the saint. Also, thcre are available facilities of self-enlightenment and enlightening beings. Also there is the available facility of unexcelled true enlightenrnent. Also there are the available facilities of the Buddha, Teaching, and Community. Alsn there are the available facilities of the turning of the wheel of the sublime teaching and liberating living beings." The Buddha, knowing what he was thinking, said to the monk, "It is so, it is so. Most profound transcendent wisdom is extremely subtle and hard to fathom."

As for the present monk's thinking to himself, where all phenomena are respected, wisdom which still has no origirration or extinction is paying obeisance. Precisely at the time of their obeisance, accordingly wisdom With available facilities has become manifest: that is what is referred to as precepts, meditation, wisdom, and so on, up to the liberation of living beings. This is called nothing. The facilities of nothing are available in this way. This is transcendent wisdom which is most profound, extremely subtle, and hard to fathom.

The king of gods asked the honorable Subhuti, "O Great Worthy, if great bodhisattvas want to learn most profound transcendent wisdom, how should they learn it?" Subhuti answered, "If great bodhisattvas want to learn most profound transcendent wisdom, they should learn it like space."

So learning wisdom is space, space is learning wisdom.

The king of gods also said to the Buddha, "World Honored One, if good men and women accept and hold this most profound transcendent wisdom you have explained, repeat it, reflect upon it in truth, and expound it to others, how should I offer protection?" Then Subhuti said to the king of gods, "Do you see that there is something to protect?" The king said, "No, I do not see that there is anything to protect." Subhuti said, "If good men and women live according to most profound transcendent wisdom as they are taught, that is protection. If good men and women abide in most profound transcendent wisdom as taught here, and never depart from it, no humans or nonhumans can find any way to harm them. If you want to protect the bodhisattvas who live in most profound transcendent wisdom as taught, this is no different from wanting to protect space."

We should know that receiving, holding, repeating, and reflecting reasonably are none other than protecting wisdom. Wanting to protect is receiving and holding and repeating and so on.

My late teacher said, "The whole body is like a mouth hung in space; without question of east, west, south, or north winds, it equally tells others of wisdom. Drop after drop freezes." This is the speaking of wisdom of the lineage of Buddhas and Zen adepts. It is whole body wisdom whole other wisdom, whole self wisdom, whole east west south north wisdom.

Shakyamuni Buddha said, "Shariputra, living beings should abide in this transcendent wisdom as Buddhas do. They shomld make offerings, pay obeisance, and contemplate transcendent wisdom just as they make offerings and pay obeisance to the Blessed Buddha. Why? Because transcendent wisdom is not different from the Blessed Buddha, the Blessed Buddha is not different from transcendent wisdom. Transcendent wisdom is Buddha, Buddha is transcendent wisdom. Why? It is because all those who realize thusness, worthies, truly enlightened ones, appear due to transcendent wisdom. It is because all great bodhisattvas, self-enlightened pcople, saints, nonreturners, once-returners, stream-enterers, and so on, appear due to transcendent wisdom. It is because all manner of virtuous action in the world, the four meditations, four formless concentranions, and five spiritual powers all appear due to transcendent wisdom."

Therefore the Buddha, the Blessed One, is transcendent wisdom. Transcendent wisdom is all things. These "all things" are the characteristics of emptiness, unoriginated, imperishable, not defiled, not pure, not increasing, not decreasing. The rnanifestation of this transcendent wisdom is the manifestation of the Buddha. One should inquire into it, investigate it, honor and pay homage to it. This is attending and servring the Buddha, it is the Buddha of attendance and service.

1223

-----------------------

Glossary

Charity, morality, forbearance, vigor, meditation, wisdom: These are the so-called six perfections, or ways of transcendence, one of the basic formulations of Mahayana Buddhism.

Earth, water, fire, air, space, consciousness: These are the "six elements" of which the universe is composed, according to the Shingon school; these elements are said to be the cosmic Buddha. itself as well as the substance of all beings, and this is taken as a basic sense in which Buddha and sentient beings are one.

Enlightening beings: This refers to bodhisattvas, people dedicatted to enlightenment for all.

Five clusters: According to the Buddhist description, these are basic components, or classes of components, of the body-mind.

Stream-enterer, once-returner, nonreturner, saint: These arr forur stages of fruition of the way to nirvana- a stream-enterer is one who has begun to he disentangled from the world; a once-returner is one who comes back to the mundane once before attaining release; a nonreturner never comes back; a saint is one who has reached nirvana and is individually ernancipated.

Suffering, accumulation, extinction, path to extinction: These are the "four noble truths," or four main axioms, of pristine Buddhism- there is suffering, suffering has a cause, there is an end to suffering, and there is a way to end, suffering.

Twelve sense media: This refers to the sense faculties (eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind) and their respectivc fields of data (form/color, sound, odor, flavor, tactile feelings, and phenomena).

22.

Zenki

The Whole Works

by Eihei Dogen

Translated by Thomas Cleary

This essay is strongly

reminiscent of the central teaching of the philosophy of the Kegon school: interdependent

origination, and its corollaries dealing with the interpenetration of existence

and emptiness, unity and multiplicity.

The word zenki consists of two elements: zen means "whole" or total or complete; ki has many meanings, those relevant to this case including "works" in the sense of machinery, potential, impetus, pivot or vital point, and the flux of nature. Ki therefore refers to phenomena in respect to their dynamic aspect, and to the dynamic or vital point itself which underlies, and is revealed by, the active coexistence of phenomena. In Kegon terms, ki includes both senses of phenomena and principle, phenomena being interdependent things, the principle being that of interdependence itself. Zen refers to the inclusiveness and pervasiveness of ki in both senses. We translate zenki as "the whole works" to convey by the colloquial sense of this expression the notion of inclusion of the totality of existence, and by the standard sense the notion of the total dynamic underlying the manifestations of existence.

In the Zen classic Blue Cliff Record, the sixty-first case says, "If a single atom is set up, the nation flourishes; if a single atom is not set up, the nation perishes." This essay of Dogen's may be said to center around a restatement of this theme: "In life the whole works is manifest; in death the whole works is manifest," or, to render the same passage another way, "Life is the manifestation of the whole works; death too is the manifestation of the whole works."

In terms of the

existence-emptiness equation, from the point of view of existence (represented

by the terms "set up" and "life") all that is exists, while

from the point of view of emptiness ("not set up," "death")

all is empty. The concurrence of existence and emptiness is not as separate

entities, but as different aspects or perspectives on the same totality. To

borrow Kegon terms again, life as the manifestation of the whole works illustrates

ki as phenomena, while death as the manifestation of the whole works illustrates

ki as noumenon.

The passage from the Blue Cliff Record alludes to the Kegon doctrine that phenomena do not exist individually but interdependently, that the manifold depends on the unit and the unit on the manifold. A refinement of this principle in Kegon philosophy is called the mystery of principal and satellites: this means that every element in a conditional nexus can be looked upon as the hub, or "principal," whereupon all the other elements become the cooperative conditions, or "satellites"-hence all elements are at once "principal" and "satellite" to all other elements. It is the mutuality, the complementarity, of the elements which makes them functionally what they are. Dogen presents this idea by likening life to riding in a boat-one is naught without the boat, yet it is one's riding in it that makes it in effect a "boat." Furthermore, "the boat is the world-even the sky, the water, and the shore are circumstances of the boat. . . . The whole earth and all of space are workings of the boat."

The distinction of existence and emptiness, the noncontradiction and mutual interpenetration of existence and emptiness, and thereby the transcendence of existence and emptiness-these are traditional steps of Mahayana Buddhist dialectic. In this essay they are presented by Dogen in his subtle, almost covert way, evidently to induce the reader to search out these insights by personal contemplation. The ultimate vision of totality, in which the whole and the individuals foster one another-the crown of Kegon Buddhist metaphysics-is one of the fundamental themes of Dogen's philosophical writings, to be met with time and again in various guises. In this essay it is conveyed in a most succinct manner, worthy of representing Zen Buddhist philosophy.

*

The Great Path of the Buddhas, in its consummation, is passage to freedom, is actualization. That passage to freedom, in one sense, is that life passes through life to freedom, and death too passes through death to freedom. Therefore, there is leaving life and death, there is entering life and death; both are the Great Path of consummation. There is abandoning life and death, there is crossing over life and death; both are the Great Path of consummation.

Actualization is life, life is actualization. When that actualization is taking place, it is without exception the complete actualization of life, it is the complete actualization of death. This pivotal working can cause life and cause death. At the precise moment of the actualization of this working, it is not necessarily great, not necessarily small, not all-pervasive, not limited, not extensive, not brief.

The present life is in this working, this working is in the present life. Life is not coming, not going, not present, not becoming. Nevertheless, life is the manifestation of the whole works, death is the manifestation of the whole works. Know that among the infinite things in oneself, there is life and there is death. One should calmly think: is this present life, along with the myriad things concomitant with life, together with life or not? There is nothing at all, not so much as one time or one phenomenon, that is not together with life. Even be it a single thing, a single mind, none is not together with life.

Life is like when one rides in a boat: though in this boat one works the sail, the rudder, and the pole, the boat carries one, and one is naught without the boat. Riding in the boat, one even causes the boat to be a boat. One should meditate on this precise point. At this very moment, the boat is the world-even the sky, the water, and the shore all have become circumstances of the boat, unlike circumstances which are not the boat. For this reason life is our causing to live; it is life's causing us to be ourselves. When riding in a boat, the mind and body, object and subject, are all workings of the boat; the whole earth and all of space are both workings of the boat. We that are life, life that is we, are the same way.

Zen Master Engo Kokugon said, "In life the whole works appears; in death the whole works appears." One should thoroughly investigate and understand this saying. What thorough investigation means is that the principle of in life the whole works appears has nothing to do with beginning and end; though it is the whole earth and all space, not only does it not block the appearance of the whole works in life, it doesn't block the appearance of the whole works in death either. When the whole works appears in death, though it is the whole earth and all space, not only does it not block the appearance of the whole works in death, it doesn't block the appearance of the whole works in life either. For this reason, life doesn't obstruct death, death doesn't obstruct life. The whole earth and all space are in life and in death too. However, it is not fulfilling the potential of one whole earth and one whole space in life and fulfilling their potential in death too. Though they are not one, they are not different; though they are not different, they are not identical; though they are not identical, they are not multiple. Therefore, in life there are myriad phenomena of the appearance of the whole works, and in death too there are myriad phenomena of the appearance of the whole works. There is also the manifestation of the whole works in what is neither life nor death.

In the manifestation of the whole works there is life and there is death. Therefore, the whole works of life and death must be like a man bending and straightening his arm. Herein there are so many spiritual powers and lights which are manifest. At the moment of manifestation, because it is completely activated by manifestation, one sees and understands that there is no manifestation before manifestation. However, prior to this manifestation is previous manifestation of the whole works. Although there is previous manifestation of the whole works, it is does not block the present manifestation of the whole works. For this reason, such a vision and understanding vigorously appears.

1242

48. Hossô

The Nature of Things

by Eihei Dogen

Translated by Thomas Cleary

In meditation study, whether following scripture or following a teacher, one becomes enlightened alone without a teacher. Becoming enlightened alone without a teacher is the activity of the nature of things. Even though one be born knowing, one should seek a teacher to inquire about the Path. Even in the case of knowledge of the birthless1 one should definitely direct effort to mastering the Path. Which individuals are not born knowing? Even up to enlightenment, the fruit of buddhahood, it is a matter of following scriptures and teachers. Know that encountering a scripture or a teacher and attaining absorption in the nature of things is called the born knowing that attains absorption in the nature of things on encountering absorption in the nature of things. This is attaining knowledge of past lives, attaining the three superknowledges,2 realizing unexcelled enlightenment, encountering inborn knowledge and learning inborn knowledge, encountering teacherless knowledge and spontaneous knowledge and correctly conveying teacherless knowledge and spontaneous knowledge.

*

If one were not born knowing, even though might encounter scriptures and teachers one could not hear of the nature of things, one could not witness the nature of things. The Great Path is not the principle of like someone drinking water knows for himself whether it's warm or cool. All Buddhas as well as all bodhisattvas and all living beings clarify the Great Path of the nature of all things by the power of inborn knowledge. To clarify the Great Path of the nature of things following scriptures or teachers is called clarifying the nature of things by oneself. Scriptures are the nature of things, are oneself. Teachers are the nature of things, are oneself. The nature of things is the teacher, the nature of things is oneself. Because the nature of things is oneself, it is not the self misconceived by heretics and demons. In the nature of things there are no heretics or demons - it is only eating breakfast, eating lunch, having a snack. Even so, those who claim to have studied for a long time, for twenty or thirty years, pass their whole life in a daze when they read or hear talk of the nature of things. Those who claim to have fulfilled Zen study and assume the rank of teacher, while they hear the voice of the nature of things and see the forms of the nature of things, yet their body and mind, objective and subjective experience, always just rise and fall in the pit of confusion. What this is like is wrongly thinking that the nature of things will appear when the whole world we perceive is obliterated, that the nature of things is not the present totality of phenomena. The principle of the nature of things cannot be like this. This totality of phenomena and the nature of things are far beyond any question of sameness or difference, beyond talk of distinction or identity. It is not past, present, or future, not annihilation or eternity, not form, sensation, conception, conditioning, or consciousness - therefore it is the nature of things.

Zen Master Baso said, "All living beings, for infinite eons, have never left absorption in the nature of things: they are always within absorption in the nature of things, wearing clothes, eating, conversing - the functions of the six sense organs, and all activities, all are the nature of things.'

The nature of things spoken of by Baso is the nature of things spoken of by the nature of things. It learns from the same source as Baso, is a fellow student of the nature of things: since hearing of it takes place, how could there not be speaking of it? 'The fact is that the nature of things rides Baso; it is people eat food, food eats people. Ever since the nature of things, it has never left absorption in the nature of things. It doesn't leave the nature of things after the nature of things, it doesn't leave the nature of things before the nature of things. The nature of things, along with infinite eons, is absorption in the nature of things; the nature of things is called infinite eons. Therefore the here of the immediate present is the nature of things; the nature of things is the here of the immediate present. Wearing clothes and eating food is the wearing clothes and eating food of absorption in the nature of things. It is the manifestation of the nature of things of food, it is the manifestation of the nature af things of eating, it is the manifestation of the nature of things of clothing, it is the manifestation of the nature of things of wearing.3 If one does not dress or eat, does not talk or answer, does not use the senses, does not act at all, it is not the nature of things, it is not entering the nature of things.

The manifestation of the Path of the immediate present was transmitted by the Buddhas, reaching Shakyamuni Buddha; correctly conveyed by the Zen adepts, it reached Baso. Buddha to Buddha, adept to adept, correctly conveyed and handed on, it has been correctly communicated in absorption in the nature of things. Buddhas and Zen adepts, not entering, enliven the nature of things.4 Though externalist scholars may have the term nature of things, it is not the nature of things spoken of by Baso. Though the power to propose that living beings who don't leave the nature of things are not the nature of things may achieve something, this is three or four new layers of the nature of things. To speak, reply, function, and act as if it were not the nature of things must be the nature of things. The days and months of infinite eons are the passage of the nature of things. The same is so of past, present, and future. If you take the limit of body and mind as the limit of body and mind and think it is far from the nature of things, this thinking still is the nature of things. If you don't consider the limit of body and mind as the limit of body and mind and think it is not the nature of things, this thought too is the nature of things. Thinking and not thinking are both the nature of things. To learn that since we have said nature (it means that) water must not flow and trees must not bloom and wither, is heretical.

Shakyamuni Buddha said, "Such characteristics, such nature." So flowers blooming and leaves falling are such nature. Yet ignorant people think that there could not be flowers blooming and leaves falling in the realm of the nature of things. For the time being one should not question another. You should model your doubt on verbal expression. Bringing it up as others have said it, you should investigate it over and over again - there will be escape from before.5 The aforementioned thoughts are not wrong thinking, they are just thoughts while not yet having understood. It is not that this thinking will be caused to disappear when one understands. Flowers blooming and leaves falling are of themselves flowers blooming and leaves falling. The thinking that is thought that there can't be flowers blooming or leaves falling in the nature of things is the nature of things. It is thought which has fallen out according to a pattern; therefore it is thought of the nature of things. The whole thinking of thinking of the nature of things is such an appearance.

Although Baso's statement all is the nature of things is truly an eighty or ninety percent statement, there are many points which Baso has not expressed. That is to say, he doesn't say the natures of all things do not leave the nature of things,6 he doesn't say the natures of all things are all the nature of things.6 He doesn't say all living beings do not leave living beings,7 he doesn't say all living beings are a little bit of the nature of things, he doesn't say all living beings are a little bit of all living beings,8 he doesn't say the natures of all things are a little bit of living beings.9 He doesn't say half a living being is half the nature of things.10 He doesn't say nonexistence of living beings is the nature of things,11 he doesn't say the nature of things is not living beings,11 he doesn't say the nature of things exudes the nature of things, he doesn't say living beings shed living beings. We only hear that living beings do not leave absorption in the nature of things - he doesn't say that the nature of things cannot leave absorption in living beings, there is no statement of absorption in the nature of things exiting and entering absorption in living beings. Needless to say, we don't hear of the attainment of buddhahood of the nature of things, we don't hear living beings realize the nature of things, we don't hear the nature of things realizes the nature of things, there is no statement of how inanimate beings don't leave the nature of things. Now one should ask Baso, what do you call "living beings"? If you call the nature of things living beings, it is what thing comes thus? If you call living beings living beings, it is if you speak of it as something, you miss it. Speak quickly, speak quickly!

1243

Notes

1. "The birthless" means emptiness, also immediate experience without comparison of before and after. This line could read "Even if one be without inborn knowledge . . . ;' but in Buddhism the term conventionally refers to knowledge of the uncreated.

2. The three superknowledges are paranormal perceptions of saints and Buddhas: knowledge of the features of birth and death of beings in the past, knowledge of the features of birth and death of beings in the future, and knowledge of extinguishing mental contaminations. In Zen all three are sometimes interpreted in reference to insight into the fundamental mind, which is in essence the same in all times and has no inherent contamination.

3. Var. lect. "Clothing is the manifestation of the nature of things, food is the manifestation of the nature of things, eating is the manifestation of the nature of things, wearing is the manifestation of the nature of things."

4. Here "not entering" means that the nature of things is not something external to be entered; rather it is something omnipresent to be lived.

5. This passage seems to point to koan practice, specifically the use of kosoku koan or ancient model koan, Zen sayings or stories used to focus awareness in certain ways. "There will be escape from before" refers to the shedding of former views or states of mind.

6. The (individual) natures of things are not apart from the (universal) nature of things, because individual natures are relative, hence empty of absolute identity - this emptiness itself is the universal nature of things.

7. Living beings qua living beings - that is, in terms of relative identity or conditional existence-are always such, by definition.

8. "All living beings" as seen from one point of view (such as that of human perception) are a small part of "all living beings" as seen or experienced from all possible points of reference. This is reminiscent of the Kegon teaching of the infinite interreflection of interdependent existences, and the Tendai teaching of all realms of being mutually containing one another. According to the Tendai doctrine, the totality of living beings is defined in terms of ten realms or universes, but as each contains the potential of all the others, this makes one hundred realms. The Kegon doctrine takes this further and says that each of the latent or potential realms in each realm also contains the latent potential of every other realm, so they are, in terms of their endless interrelation, multiplied and remultiplied infinitely.

9. In terms of the doctrine of the interdependence of everything in the cosmos, as exemplified by the Kegon teaching, all things are a part of the existence of each and every thing and being.

10. Essence (emptiness of absolute identity) and characteristics (existence of relative identity) may be likened to two "halves" of the totality of all existence and the nature of things.

11. "Nonexistence of living beings" as emptiness of an absolute nature of "living beings" is the nature of things qua emptiness.