ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

明菴栄西 Myōan Eisai (1141-1215)

明菴榮西 Myōan Yōsai; 千光国師 Senkō Kokushi

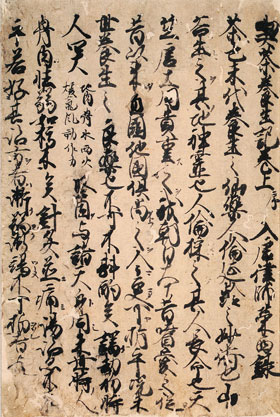

興禅護国論 Kōzen-gokoku-ron (1198)

喫茶養生記 Kissa-yōjō-ki (1211)

出家大綱 Shukke taikō

Tartalom |

Contents |

|

PDF: A Treatise on Letting Zen Flourish to Protect the State PDF: Zen as the Ideology of the Japanese State: Eisai and the Kôzen gokokuron Eisai: Propagation of Zen for the Protection of the State (Kōzen gokokuron) Eisai: Essentials for Monastics (Shukke taikō) (出家大綱) PDF: Eisai's “Zen for National Defense.” Buddhist Scriptures, Penguin Books, 2004 PDF: Eisai's Promotion of Zen for the Protection of the Country Myōan Eisai and Conceptions of Zen Morality: Eisai. The First Japanese Master PDF: Yōsai: Drink Tea and Prolong Life Yōsai and the transformation of Buddhist precepts in pre‐modern Japan |

![]()

The first Japanese monk to transmit the Rinzai teachings to Japan was the Japanese Tendai monk Myoan Yosai [Eisai] 明菴榮西 (1141–1215). Born in present Okayama Prefecture, he became a Tendai-school monk at the age of eleven and studied the esoteric teachings of that tradition. He went to the Tendai headquarters on Mt. Hiei two years later, and was ordained in 1154. In 1168 he traveled to China, where he studied the Tiantai teachings and practiced Tiantai meditation methods for six months before returning to Japan.

Twenty years later, in 1187, he once again sailed for China, hoping to make a pilgrimage to India, the home of Buddhism, in order further his goal of restoring Japanese Zen to its original ideals. When the Chinese government refused him permission to travel beyond its borders, Eisai made his way to Mount Tiantai and undertook the practice of Linji (Rinzai) Zen with the Huanglong (Oryo) 黄龍 lineage master Xuan Huaichang 虚庵懷敞 (J., Koan Esho; n.d.), under whom he studied both meditation and the vinaya.

In 1191 Eisai returned to Japan, bringing not only the Rinzai Zen teachings but also the practice of tea-drinking. He founded the monastery Shofuku-ji on the island of Kyushu, avoiding the capital of Kyoto for the time being because of opposition to the Zen teachings from the older established sects of Tendai and Shingon. Later he did go to the capital to answer charges made against him by the older schools, presenting his arguments in his chief work, the Kōzen Gokokuron (Propagation of Zen for protection of the nation). In 1199 he went to Kamakura to assume the abbacy of the temple Jufuku-ji 壽福寺, built for him by the Kamakura Shogunate. In 1202 he agreed to become abbot of the new temple Kennin-ji in Kyoto, where, until the end of his life in 1215, he taught a combination of Zen meditation with Tendai and Shingon ritual. Although Eisai's Oryo lineage did not continue long, he was important in setting the stage for the restoration of monastic discipline and the establishment of Zen meditation practice.

He introduced the cultivation of tea into Japan, and wrote a book, entitled On Drinking Tea as A Way of Nourishing Spirit (Kissa-yōjō-ki 喫茶養生記). His other works include the Discourse on the Propagation of Zen and Protection of the Stat e (Kōzen-gokoku-ron 興禅護国論), which is the first Zen work in Japan. He was given the posthumous title, Senko Kokushi 千光国師 (State Master a Thousand Rays of Light).

http://openreads.com/chapter/the-zen-experience-chapter-15-eisai-the-first-japanese-master/

Eisai by

William Bodiford

in Sources of Japanese Tradition: Volume 1: From Earliest Times to 1600

ed. by Wm. Theodore de de Bary

pp. 308-319.

Japanese Zen tradition customarily cites Eisai (aka Yōsai, 1141–1215) and Dōgen (1200–1253) as the first teachers of Song-dynasty Zen in Japan and as the founders of the Rinzai (Ch: Linji) and Sōtō (Ch: Caodong) Zen lineages, respectively. Certainly Eisai and Dōgen were important Zen pioneers who laid the foundation for subsequent developments, but their Zen teachings had little immediate impact. Even the wave of Chinese émigré Zen teachers who fled to Japan from the advancing Mongol armies and found new patrons among the military rulers of Kamakura immediately before and after the first Mongol invasion attempt of 1274 remained largely isolated from cultural currents. These Chinese monks provided the Hōjō regents and the new military government with a cosmopolitan aura otherwise lacking in the provincial town of Kamakura. But overall, the Kamakura warlords continued to sponsor established Buddhist schools and to join Pure Land and Nichiren movements as well. It was not until the second- and third-generation Japanese disciples of this first wave of Zen pioneers found new patrons among rival warlords and among members of the royal family that Zen became prominent in Japan.

Eisai was a Tendai monk who traveled to China twice (in 1168 and from 1187 to 1197). He was especially impressed by the resolute discipline of Chinese monasteries, which contrasted markedly with the moral laxity so common among Japanese clerics. Eisai believed that Zen would breathe new life into Japanese Tendai by reviving strict observance of the Buddhist precepts and the norms of monastic decorum. But Eisai’s agenda was opposed by the Tendai establishment on Mount Hiei. He also had to contend with competition from the Darumashū, a rival Zen group founded by another Tendai monk named Nōnin, who never went to China but who had received mail-order certification in a Chinese Zen lineage. The Darumashū (named after Bodhidharma) promoted ideas completely opposite from Eisai’s goals. They taught that no monastic discipline was required, since Buddha awakening could be expressed in any activity. In 1194, the court in Kyoto banned the Zen teachings of Eisai and the Darumashū. Eisai’s most important work, the Propagation of Zen for the Protection of the State (Kōzen gokokuron, 1198), is an eloquent defense of Chinese Zen training that shows how it differs from normative Japanese Tendai and Darumashū practices.

Eisai: Propagation of Zen for the Protection of the State (興禅護国論 Kōzen gokokuron)

Translated by William BodifordEisai compiled this anthology in 1198, four years after the court had prohibited the establishment of independent Zen institutions in an attempt to persuade the court not merely to lift its ban but also to promote Zen in order to revitalize Japanese Buddhism. Since Eisai’s chief adversaries at the Kyoto court were the monks of Mount Hiei monastery, which Saichō had founded, Eisai selected quotations primarily from scrip- tures and commentaries favored in the Tendai school to argue that Zen is the essence of true Buddhism. He points out that Saichō himself belonged to a Zen lineage and asserts that if Zen is illegitimate, then Saichō and the Tendai school he founded must also be illegitimate. In the following excerpts, Eisai equates Zen with the essence of mind, whose clarification is the goal of Buddhist practice. He asserts that mind is understood only by members of the special Zen lineage and emphasizes that the master-to-disciple transmission of the Zen lineage preserves the correct forms of monastic discipline as well as strict adherence to the precepts. He further attacks the Darumashū as false Zen, defends Zen ' s rejection of language, and attempts to show how Zen practice will reform wayward Japanese Buddhist monasticism.

Preface

So great is Mind! Heaven's height is immeasurable, but Mind goes above it. Earth's depth is unfathomable, but Mind extends beneath it. The light of the sun and moon cannot be outdistanced, yet Mind reaches beyond them. Galaxies are as infinite as grains of sand, yet Mind spreads outside them. Ho w great is the empty space! How primal is the ether! Still Mind encompasses all space and generates the ethereal. Because of it, Heaven and Earth treat us with their coverage and support. The sun and moon treat us with their circuits, and the four seasons treat us with their transformations. The myriad things treat us with their fecundity. Great indeed is Mind! Of necessity we assign it names: the Supreme Vehicle, the Prime Meaning, the True Aspect of Transcendental Wisdom [Prajñā], the Single Dharma Realm of T ruth, the Unsurpassed A wakened Wisdom [Bodhi], the Heroic Concentration [Shūrangama samādhi], the True Dharma Eye Matrix, the Marvelous Mind of Nirvāna. All scriptures of the Three Turnings of the Dharma Wheel and eight canons, as well as all the doctrines of the Four Shāla Trees and Five Vehicles fit neatly within it.

The Great Hero Shākyamuni's having conveyed this Mind Dharma to his disciple the golden ascetic Mahā Kāshyapa is known as the special transmission outside the scriptures. From their facing one another on Vulture Peak to Mahā Kāshyapa's smile in Cockleg Cave, the raised flower produced thousands of shoots; from this one fountainhead sprang ten thousand streams. In India the proper succession was maintained. In China the dharma generations were tightly linked. Thus has the true dharma as propagated by the Buddhas of old been handed down along with the dharma robe. Thus have the correct ritual forms of Buddhist ascetic training been made manifest. The substance of the dharma is kept whole through master-disciple relationships, and confusion over correct and incorrect monastic decorum is eliminated. In fact, after Bodhidharma, the great master who came from the West, sailed across the South Seas and planted his staff on the banks of the East River in China, the Dharma-eye Zen lineage of Fayan Wenyi was transmitted to Korea and the Ox-head Zen lineage of Niudou Farong was brought to Japan. Studying Zen, one rides all vehicles of Buddhism; practicing Zen, one attains awakening in a single lifetime. Outwardly promoting the moral discipline of the Nirvāna Scripture while inwardly embodying the wisdom and compassion of the Great Perfection of Wisdom Scripture is the essence of Zen.

In our kingdom the sovereign shines in splendor and his honor extends far and wide. Emissaries from distant fabled lands pay their respects to his court. Ministers conduct the affairs of the realm while monastics propagate the path of renunciation. Even the dharma of the Four Hindu Vedas finds use. Why then discard the five family lineages of Zen? Nonetheless, many malign this teaching, calling it the Zen of blind trance. Others doubt it, calling it the evil of clinging to emptiness. Still others consider it ill-suited to this latter age of dharma decline, saying that it is not needed in our land. Or they disparage my capacity, saying that I lack sufficient power. They belittle my spiritual ability, saying that it is impossible for me to revive what was already abandoned. Whoever attempts to uphold the Dharma Jewel in such a way destroys the Dharma Jewel. Not being me, how can they know my mind? Not only do they block the gateway through the Zen barriers, but they also defy the legacy of Saichō, the founder of Mount Hiei. Alas, how sad, how distressing. Which of us is right? Which of us is wrong?

I have compiled an anthology of the Buddhist scriptures that record the essential teachings of our lineage for consideration by today's pundits and for the benefit of posterity. This anthology is in three fascicles consisting of ten chapters, and it is entitled Propagation of Zen for the Protection of the State in accordance with the basic idea of the Sutra for Humane Kings. As my humble fictive words accord with reality, I ignore the catcalls of ministers and monastics. Remembering that the Zen of Linji benefits his later generations, I am not embarrassed by their written slanders. I merely hope that the flame of wisdom transmitted in Zen verse will not be extinguished until the arrival of Maitreya and that the fountain of Zen will flow unimpeded until the future eon of the Thousand Buddhas.

[Ichikawa, Chūsei zenke, pp. 8–9; WB]

Zen and Precepts

Question: Some criticize you, asking what makes you think this new Zen lineage will cause Buddhism to flourish forever?

Answer: Moral precepts and monastic discipline cause Buddhism to flourish forever. Moral precepts and monastic discipline are the essence of Zen. Therefore, Zen causes Buddhism to flourish forever. Zhiyi’s Calming and Contemplation states: ‘‘Worldly desires of ordinary people are denounced by all the holy ones. Evil is destroyed by pure wisdom. Pure wisdom arises from pure Zen. Pure Zen arises from pure precepts.’’

[Ichikawa, Chūsei zenke, pp. 35–36; WB]

The Darumashū

Question: Some people say that the Zen teaching of ‘‘not relying on words and letters’’ means the evil of clinging to emptiness and the practice of blind trance. If so, then Tendai opposes it. In Zhi-yi’s Calming and Contemplation, where it explains contemplation of the inconceivable object, it says: ‘‘This cannot be known by the Zen teachers of blind trance or the dharma masters of scriptural chanting.’’ In Zhiyi’s Profound Meaning of the Lotus Scripture it says: ‘‘If those who contemplate Mind think that their own mind is it, equate themselves with the Buddha, and ignore the scriptures, then they fall into the error of arrogance. It is like holding a torch so as to burn oneself.’’ Likewise, Zhanran’s commentary on this passage says: ‘‘Grasping the torch of blind trance burns the hand of cavalier meditator.’’ How do you respond to these criticisms of not relying on words and letters?

Answer: This Zen lineage despises teachers of blind trance and hates people who practice the evil of clinging to emptiness. They are as repugnant as corpses sunk to the bottom of the ocean. We solely rely on the Perfect Teaching, cultivating the perfect and the sudden. Outwardly we observe the precepts to eliminate vice, inwardly we employ compassion to benefit others. This is called the Zen teaching. This is called the Buddha dharma. Those who practice blind Zen and cling to evil not only lack our teaching but are thieves of the dharma. Yongming Yanshou’s Zen Mirror Record says: ‘‘Principle truly responds to conditions. No practice obstructs principle. Practice rests on principle. No practice exists without principle. Those people who do not enter the Perfect Teaching but disparage others as being beneath them and regard themselves as spiritually advanced have not only lost the practice but completely lack principle. One must merely awaken to the essence of the One Mind free from all obstructions, in which principle and practice fuse together naturally, in which the worldly and the ultimate merge completely. If one clings to practice and mistakes principle, then one sinks into eons of samsāra. If one awakens to principle but neglects practice, then one lacks perfect realization. How can principle and practice not be products of the mind? How could essence and appearance not correspond? If one enters the Zen Mirror and suddenly awakens to the True Mind, then even the words ‘principle’ or ‘practice’ do not exist, much less the clinging to principle or practice. But after attaining the fundamental, one must not abandon perfect cultivation. How can those practitioners of the Zen of blind trance even know of the Six Identities between Buddha and Humans? How can the crazed chanters of the scripture even be aware of the One Mind?’’ . . .

Question: But what about those who mistakenly refer to the Zen lineage as the Dharumashū? They teach: ‘‘There is nothing to practice, nothing to cultivate. Originally afflictions (klesha) do not exist. From the beginning, afflictions are bodhi. Therefore, moral precepts and monastic rituals are of no use. One should merely eat and sleep as needed. Why must anyone labor to recall the Buddha (nembutsu), to worship relics, or to observe dietary restrictions?’’ What about their teaching?

Answer: There is no evil that such people will not do. They are the ones the scriptures denounce as nihilists. One must not talk with such people nor even sit with them. One must avoid them by a thousand yojana [about 8,500 miles].

[Ichikawa, Chūsei zenke, pp. 39–41; WB]

Language

‘‘Scriptures,’’ or ‘‘Zen’’ are merely names. ‘‘Investigate,’’ or ‘‘study’’ likewise are merely provisional designations. ‘‘Self,’’ ‘‘other,’’ ‘‘living beings,’’ ‘‘bodhi,’’ ‘‘nirvāna,’’ and so forth are just words, without any real existence. Similarly, because the dharma preached by the Buddha is just such words, in reality nothing was preached.

For this reason Zen lies beyond the details of words and letters, outside mental conditions, in the inconceivable, in what ultimately cannot be grasped. ‘‘So-called Buddha dharma consists of the dharma that cannot be preached.’’ So-called Zen is exactly the same. If anyone says the Buddha’s Zen exists in words, letters, or speech, then that person slanders the Buddha and slanders the dharma. For this reason our ancestral teachers did not rely on words and letters, pointed directly at the human mind, saw nature, and became Buddhas. Such is Zen practice. Whoever clings to words loses the dharma, whoever clings to appearances becomes topsy-turvy. Fundamentally inactive, without a thing to grasp, is seeing the Buddha dharma. The Buddha dharma consists of merely walking, standing, sitting, and lying down. Adding even a single fine hair to it is impossible. Subtracting even a single fine hair from it is impossible. Once one attains this understanding, then expend not even the least effort. With even the slightest attempt at being clever, one has already missed it. Therefore, activity gives rise to samsāra while quietude leaves one in a drunken stupor, and avoiding both activity and quietude displays ignorance of Buddha nature. If one does none of the above, then what? This point lies outside clarification of doctrine. It cannot be fathomed through words. Look ahead and see! Get up and go! Once the arrow leaves the bow, there is no art that can bring it back. Even the thousand Buddhas could not grab it. As long as it has not hit the ground, no matter how much one might rue the crooked shot, one merely seizes air. Even if one tried until the last days of one’s life, there is no grasping it.

[Ichikawa, Chūsei zenke, pp. 62–63; WB]

Ten Facilities for Zen Monasticism

Facilities for Zen Monasticism consist of ten items, which I describe in accordance with the Pure Rules for Zen Cloisters and other Chinese standards.

First, the monastery: Monasteries can be large or small, but all should conform to the layout of the Buddha’s Jetavana Vihāra (Gion Shōja) in India. Along the four sides there are walls without side gates. There is only one main gate, which the gatekeeper shuts at dusk and opens at dawn. Nuns, women, and inauspicious people must not be allowed to stay the night. The decline of the Buddha dharma always results from women.

Second, ordinations: The distinction between Hinayāna precepts and Mahāyāna precepts exists only in the hearts of men. Because one must merely embody sentiments of great compassion for the benefit of others, Zen does not choose between Mahāyāna or Hinayāna precepts but merely focuses on living a pure life.

Third, observing the precepts: After ordination, if one violates the precepts, it would be the same as obtaining a precious jewel only in order to smash it. Therefore one must strictly observe the two hundred fifty bhiksu [monk] precepts, as well as the bodhisattva’s three groups of pure precepts, ten major precepts, and forty-eight minor precepts. Twice each month during the uposatha ceremony, these precepts must be reviewed as explained in the precept scriptures. Anyone who violates the precepts must be kicked out. Such a one can be likened to a corpse cast into the ocean.

Fourth, academic study: Learning that spans the entire Buddhist canon and conduct that accords with the Mahāyāna and Hinayāna precepts as well as proper monastic decorum constitute being a field of merit for gods and men. Inwardly embodying the great compassion of the bodhisattvas constitutes being a benevolent father to all living beings. In this way we become a valued jewel to the sovereign and a good physician to the country. To these goals we must aspire.

Fifth, ritual conduct: monastics observe dietary restrictions, practice chastity, and obey the Buddha’s words. The schedule for each night and day are as follows: At dusk all monks assemble in the Buddha Hall to offer incense and worship. At evening they practice sitting Zen (zazen). During the third watch of the night (about 2:00 a.m.) they sleep. During the fourth watch they sleep. At the fifth watch they practice sitting Zen. At cockcrow they assemble in the Buddha Hall to offer incense and worship. At dawn they eat morning gruel. At the hour of the dragon (about 8:00 a.m.) they chant scriptures, study, or attend elder monks. At midmorning they practice sitting Zen. At noon they eat their daily meal. Afterwards they bathe or wash. During midafternoon they practice sitting Zen. Late afternoons are free time. The four periods of sitting Zen must be diligently practiced. Each moment of sitting Zen repays one’s debts to the state; each act commemorates the sovereign’s long life. These rituals truly cause the imperial reign to long prosper and the dharma flame to shine forever.Sixth, monastic decorum: Old and young must always wear full robes. When they encounter one another, they must first place the palms of their hands together and then bow their heads to the ground in harmonious expressions of respect. Also, all meals, all walking exercises, all sitting Zen, all academic study, all chanting, and all sleeping must be performed as a group. Even if a hundred thousand monks are together inside one hall, each of them must observe correct monastic decorum. If someone is absent, the group leader (inō) must investigate and must not forgive even the slightest transgression.

Seventh, robes: Both inner and outer wear should conform to Chinese designs. These imply circumspection. One must be prudent in all affairs.

Eighth, disciples: Those who embody morality and wisdom without lapse should be admitted to the assembly. They must possess both mental and physical ability.

Ninth, economic income: As they say, ‘‘Do not cultivate the fields, since sitting Zen leaves no time for it; Do not hoard treasures, since the Buddha’s words alone suffice.’’ Aside from one cooked meal each day, eliminate all other needs. The dharma of monks consists of being satisfied with as little as possible.

Tenth, summer and winter retreats: The summer retreat begins on the fifteenth day of the fourth moon and ends on the fifteenth day of the seventh moon. The winter retreat begins on the fifteenth day of the tenth moon and ends on the fifteenth day of the first moon. Both of these two retreats were established by the Buddhas. Do not doubt it. In our land these retreats have not been practiced for a long time. In the great land of Song-dynasty China, however, not a single monk fails to participate in the two retreats. From the standpoint of the Buddha dharma, the Japanese practice of calculating one’s monastic seniority in terms of the retreats without actually participating in them is laughable.

[Ichikawa, Chūsei zenke, pp. 80–83; WB]

Eisai: Essentials for Monastics (出家大綱 Shukke taikō)

Translated by William BodifordUnlike Propagation of Zen for the Protection of the State, which was directed toward a wide audience of court officials and ecclesiastical officials, Eisai wrote this treatise for his own followers as a guide to the proper lifestyle for Buddhist monks and nuns. In it, he confesses that before his trip to China he had, like most other Japanese monks, ignored the Buddhist prohibitions against eating meat and drinking alcohol. Eisai’s vigorous advocacy for observing the Buddhist precepts is remarkable not just because it goes against the currents of Japanese Buddhist history but also because it stresses such elementary points (e.g., the distinctions between Buddhist robes and secular clothing) that the reader is left with the impression that clerics of Eisai’s time completely lacked any firsthand knowledge of traditional Buddhist monastic norms. The opening section gives an overview of the treatise.

The Buddha dharma is the boat that ferries one across the sea of death, the chariot that traverses the roads of delusion, the good medicine that cures our eternal afflictions, the torch that illuminates our long night. The depth of its merit cannot be fathomed. Now that the degenerate and evil age has finally arrived, our ability to know suffering must develop. Now that we have entered the beginning of the latter five hundred years, the number of people who study precepts must increase. The Great Perfection of Wisdom Scripture’s prophecy that it will be propagated in northeastern lands during the latter age must refer to today’s Japan. Likewise, how could the Nirvana Scripture’s goal of promoting moral discipline during the latter age have been intended for any other time? The same applies to the Lotus Scripture’s four peaceful practices for the evil age and to the Calming and Contemplation’s encouragement of samadhi. What is essential for this age is merely to follow the Buddha’s own words, namely, ‘‘promoting moral discipline by preaching the permanent.’’

The life essence of the Buddha dharma is moral purity. You must compre- hend this life essence. The five-thousand scrolls of scriptures are called the Buddha dharma. How can you chant them without practicing what they teach? The sixty scrolls of Zhiyi’s commentaries are known as the Tendai Perfect Doctrine. How can you discuss them without following their principles? You must know that Buddha dharma consists of the Buddha’s wondrous decorum. Only a person who knows the Buddha dharma’s meaning, who understands its prin- ciples, and who practices its decorum can be called a Buddhist.

In this treatise I outline the practice of Buddhist decorum in order to save people during this latter age. The Buddhist canon of discourses, discipline, and treatises resembles a contract. They record the principles of the threefold study (meditation, morality, and wisdom) of the Buddha dharma. For example, contracts for estates (shōen) are preserved in a ledger to show how much profit can be derived from planting, weeding, and harvesting a piece of land. Similarly, chanting the discourses, discipline, and treatises and practicing their teachings show you how to rectify body and mind and how to follow the Buddha’s footsteps.

The Seven Past Buddhas’ Precept Verse says: ‘‘Refrain from all evil; Perform every manner of good; Purify your own mind; This is the teaching of all Buddhas.’’ All the doctrines preached by the Buddha throughout his teaching career are summed up in this one verse. How can you rely on the Buddha’s teaching to leave your home as a renunciant monk, yet not follow the Buddha’s admo- nition? The time to uphold the precepts has arrived. How can you imagine that observing the precepts is tiresome? Isn’t the wheel of suffering around your neck more bothersome? When impermanence strikes you in the face, don’t be caught lackadaisically napping.

When I, Eisai, was in Great China, I studied the holy scriptures, recorded the main points of the discipline, and then returned to Japan. Once here, I knew that the time was ripe and that people’s spiritual capacities were ready for me to promote the precepts. When so many monks responded to my encour- agement, I experienced joy a thousand times over. Since my twenty-first year until my fiftieth year, I have trained as a Buddhist monk in Japan and in China for a full thirty years. During that time I never before experienced any miracles. Now, however, I have the miracle of all of you following me. Based on the notes that I took in China, I have written this treatise on precepts for the latter age. Anyone who wishes to attain moral purity should follow its exhortations. The essentials for monastics are written herein.

Maintaining moral purity consists of two main types of practices. The first concerns robes and meals. The second concerns practice and decorum. First, robes cover the body while meals nourish the body. Second, practice means observing the Buddhist precepts while decorum means proper etiquette. Each of these consists of two types. There are secular robes and dharma robes. There are invitations to banquets and begging for food. There are bhiksu precepts and bodhisattva precepts. There are secular forms of etiquette and the universal norms of the Way...

[from the 1789 woodblock edition]

PDF: A Treatise on Letting Zen Flourish to Protect the State

by Myōan Eisai (1141-1215)

Translated by Gishin Tokiwa

In: Zen Texts, BDK Tripitaka Translation Series, 2005, pp. 43ff.

Eisai's Dharma Lineage

|

28/1. Bodaidaruma |

29/2. Taiso Eka |

|

30/3. Kanchi Sōsan |

|

31/4. Daii Dōshin |

|

32/5. Daiman Kōnin |

|

33/6. Daikan Enō |

|

34/7. Nangaku Ejō |

|

35/8. Baso Dōitsu |

|

36/9. Hyakujō Ekai |

|

37/10. Ōbaku Kiun |

|

38/11. Rinzai Gigen |

|

39/12. Kōke Zonshō |

|

40/13. Nan'in Egyō |

|

41/14. Fūketsu Enshō |

|

42/15. Shuzan Shōnen |

|

43/16. Funyō Zenshō |

|

45/18. Ōryū Enan |

|

46/19. Kaidō Soshin |

|

47/20. Reigen Isei |

|

48/21. Chōrei Shutaku |

|

49/22. Muji Kaijin |

|

50/23. Mannen Donkan |

51/24. Setsuan Jūkin |

52/25. Koan Eshō |

53/26/1. Myōan Eisai |

「喫茶養生記」 Kissa Yōjōki - the Book of Tea

1)

In 1191, the famous Zen priest Eisai (栄西; 1141-1215) brought back tea seeds to Kyoto. Some of the tea seeds were given to the priest Myoe Shonin, and became the basis for Uji tea. The oldest tea specialty book in Japan, Kissa Yōjōki (喫茶養生記; How to stay healthy by drinking tea) was written by Eisai. The two-volume book was written in 1211 after his second and last visit to China. The first sentence states, "Tea is the ultimate mental and medical remedy and has the ability to make one's life more full and complete". The preface describes how drinking tea can have a positive effect on the five vital organs, especially the heart. It discusses tea's medicinal qualities which include easing the effects of alcohol, acting as a stimulant, curing blotchiness, quenching thirst, eliminating indigestion, curing beriberi, preventing fatigue, and improving urinary and brain function. Part One also explains the shapes of tea plants, tea flowers and tea leaves and covers how to grow tea plants and process tea leaves. In Part Two, the book discusses the specific dosage and method required for individual physical ailments.

Eisai was also instrumental in introducing tea consumption to the warrior class, which rose to political prominence after the Heian Period. Eisai learned that the shogun Minamoto no Sanetomo had a habit of drinking too much every night. In 1214, Eisai presented a book he had written to the general, lauding the health benefits of tea drinking. After that, the custom of tea drinking became popular among the Samurai.

2)

The Kissa Yōjōki 「喫茶養生記」 or “Tea drinking Good for the Health” of Eisai Zenji, the famous Buddhist scholar and architect who went to China in 1187, is the first work on Tea written in Japan. It is small pamphlet of some twenty printed pages devoted to the virtues of Tea and of Mulberry Infusion which he strongly recommends for the Five Disease, viz. the water-drinking disease, the want of appetite disease, paralysis, boils and beri-beri . There are two MSS of it, one dated 1211 and the other 1214. It was in this latter yare that Eisai is said to have cured the Sogun Sanemoto of some malady by means of Tea, and as a result it became a fashionable remedy. Other medicines, he observes, cure only one kind of disease, but Tea is a remedy for all disorders. As the Sung poet says, “The Pest-god gets out of his chariot to salute the Tea tree.” 「皇帝が馬車を降りて茶の木におじぎをする」。 Eisai quotes the Sonsho Darani Kyo as declaring that of the Five Viscera, the Liver likes acid taste, the Lungs pungent, the Heart bitter, the Spleen sweet and the Kidneys salt. Now the Heart is the chief of the Five Viscera, as Bitter is the chief of the Five Tastes. And since Tea is the chief of bitter tastes naturally it is best for the Heart.

PDF: Yōsai: Drink Tea and Prolong Life

by Paul Varley

in: Sources of Japanese Tradition, Volume 1, pp. 393-395.

Drinking Tea for Health (Kissa-yōjōki 喫茶養生記, 1211 or 1214) by Eisai 栄西

The First Japanese Book about the drinking tea. In Chinese, with Classical Japanese, Modern Japanese translations.

https://www.scribd.com/doc/229536679/Eisai-Kissa-Hojoki

Eisai: The Monk that Propagated Tea Culture in Japan

By Ricardo Caicedo

http://www.myjapanesegreentea.com/eisaiMyouan Eisai (Myōan Eisai, 明菴栄西) is best known for bringing the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism to Japan.

He also played a prominent role in Japanese tea history because he wrote the Kissayojoki (喫茶養生記), a book about tea.

A closer look at Eisai’s life

He was born on April 20th of 1141 in what is now Okayama prefecture. His father was a Shinto priest.

At the age of eleven he studied the Tendai school of Buddhism in Anyouji temple. When he was 14 he became ordained at Mount Hiei, near Kyoto.

As a side note, the Tendai school was founded by Saicho, another Buddhist monk. He was one of the first to bring tea seeds to Japan, according to written accounts.

When Eisai was 28 (year 1168), he travelled to Mount Tiantai (Tendai in Japanese) in China to further his studies. Since this was where his school of Buddhism originated, it was the best place to go.

In his six month’s stay, he learned that Zen teachings had become widespread in Chinese Buddhism. He also obtained 60 volumes of scriptures and offered them to the head priest of his school.

This was no small feat for such a young man, and so this gives us an impression of Eisai’s skill.

His second trip to China wouldn’t happen until 1187, when he was 47 years old. He wanted to visit India, the motherland of Buddha.

However, once in China the local government didn’t give him permission to cross the border, so he decided to study there once more.

Eisai spent four years as a disciple of Xuan Huaichang (虚庵懷敞), who was a master of the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism.

He received the certification of Zen teacher (the first one given to a Japanese monk in China), and returned to Japan in 1191.

Eisai and tea

Eisai didn’t only bring the teachings of Rinzai Zen to Japan. He also brought tea seeds with him.

He first planted tea seeds in Mount Sefuri, on the border of Fukuoka and Saga prefectures. He thought that this place looked similar to Mount Tiantai, so it was a suitable place for the tea plants to grow.

In addition, he gave tea seeds to Myoue Shounin (明恵上人), a monk from Kousanji temple (高山寺) in Toganoo (栂尾), Kyoto. Myoue planted the seeds near the temple, and this was the beginning of tea in the region of Uji.

There’s a written account from 1214 where Shogun Minamoto was suffering from a hangover, and Eisai gave him tea and also his book: Kissayojoki. By then, Eisai was 74 years old.

The book talked about the health benefits of tea, how to cultivate it, and how to prepare it, among other things.

This led to the reintroduction of tea culture in Japan, because this time the lower classes began to drink it. Until then, tea was reserved for nobles and monks only.

Eisai died close to a year later and was buried in Kenninji, the temple that he founded back in 1202. He is now known as the father of Japanese tea culture.

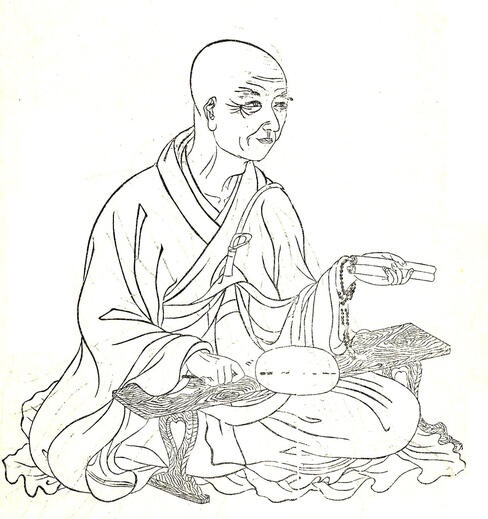

明恵上人 Myōe Shōnin (1173-1232)

Myōe 明恵 by Tani Buncho (谷文晁 1763-1841) et al. 1800-1804. Woodblock print.Myoue Shounin: The Beginning of Tea in Uji

By Ricardo Caicedo

http://www.myjapanesegreentea.com/myoue-shouninMyoue Shounin (Myōe Shōnin, 明恵上人) was a Japanese Buddhist monk that lived from 1173-1232.

“Shounin” is a title, which can be translated as “high priest”.

Myoue is remembered for popularizing the Kegon school of Buddhism (華厳宗), and for keeping a journal of his dreams for over 40 years.

In addition, he also played a role in the history of Japanese tea, as we will see next.

The story of Myoue

Myoue was born in January 8th of 1173, in what is now Wakayama prefecture.

Both of his parents died in 1180 while he was still a child. First it was his mother due to an illness, and several months later his father passed away in a battle.

An aunt took care of him, and later on when he was 9 years old he started his Buddhist studies.

His first teacher was his uncle Joukaku, who was a Shingon Buddhist priest. When Myoue was 16, he became the pupil of Mongaku, who was also Joukaku's teacher.

Myoue then traveled to Toudaiji temple in Nara, where he learned the Kegon school of Buddhism under Shousen's guidance.

Furthermore, he also learned about Zen from Eisai. They became friends from there on.

In 1206 Myoue was given the Kousanji (高山寺) temple in Toganoo (栂尾), Kyoto, by Emperor Go-Toba. Myoue had the task of reviving the Kegon school of Buddhism, which he did.

It was there in Kousanji where Myoue was given tea seeds as a gift from Eisai, who had brought them from China.

Myoue not only planted the tea seeds near the temple. He became a regular tea drinker and encouraged other monks to do the same, because tea helps to avoid falling asleep while meditating.

This was how tea begun to spread around Kyoto, especially in the region of Uji. In fact, tea from Toganoo became known as honcha (本茶), meaning “real tea”. All other tea cultivated somewhere else was referred to as hicha (非茶), “false tea”.

As time passed by, it was the tea from Uji that took the title of honcha. It's the most prestigious tea growing region in Japan.

At Kousanji temple the tea field remains, and it is still harvested every year in mid May.

Every 8th of November, there is a memorial ceremony where the tea industry association of Uji brings shincha to the temple.

Watching the Moon Go Down

Translated by Burton WatsonSet now,

and I too will go

below the rim of the hill—

so night after night

let us keep company* * *

Bright bright!

bright bright bright!

bright bright!

bright bright bright!

bright bright, the moon!

EISAI:

THE FIRST JAPANESE MASTER

In: The Zen Experience by Thomas Hoover

Copyright ©1980

There is a twelfth-century story that the first Japanese monk who

journeyed to China to study Ch'an returned home to find a

summons from the Japanese court. There, in a meeting

reminiscent of the Chinese sovereign Wu and the Indian

Bodhidharma some seven hundred years before, Japan's

emperor commanded him to describe the teachings of this

strange new cult. The bemused monk (remembered by the name

Kakua) replied with nothing more than a melody on his flute,

leaving the court flabbergasted.1 But what more ideal expression

of China's wordless doctrine?

As in the China entered by Bodhidharma, medieval Japan

already knew the teachings of Buddhism. In fact, the Japanese

ruling classes had been Buddhist for half a millennium before

Ch'an officially came to their attention. However, contacts with

China were suspended midway during this time, leaving

Japanese Buddhists out of touch with the many changes in

China—the most significant being Ch'an's rise to the dominant

Buddhist sect.2 Consequently the Japanese had heard almost

nothing about this sect when contacts resumed in the twelfth

century. To their amazement they discovered that Chinese

Buddhism had become Ch'an. The story of Ch'an's transplant in

Japan is also the story of its preservation, since it was destined to

wither away in China.

Perhaps we should review briefly how traditional Buddhism

got to Japan in the first place. During the sixth century, about the

time of Bodhidharma, a statue of the Buddha and some sutras

were transmitted to Japan as a gift/bribe from a Korean monarch

seeking military aid. He claimed Buddhism was very powerful

although difficult to understand. Not all Japanese, however, were

overjoyed with the appearance of a new faith. The least pleased

were those employed by the existing religion, the Japanese cult of

Shinto, and they successfully discredited Buddhism for several

decades. But a number of court intrigues were underway at the

time, and one faction got the idea that Buddhism would be helpful

in undermining the Shinto-based ruling clique. Eventually this new

faction triumphed, and by the middle of the seventh century, the

Japanese were constructing Buddhist temples and pagodas.3

Other imports connected with these early mainland contacts

were Chinese writing and the Chinese style of government. The

Japanese even recreated the T'ang capital of Ch'ang-an,

consecrated at the beginning of the eighth century as Nara, their

first real city. The growing Buddhist establishment soon

overwhelmed Nara with a host of sects and temples, culminating

in 752 with the unveiling of a bronze meditating Buddha larger

than any statue in the world.

Japan was now awash in thirdhand Buddhism, as Chinese

missionaries patronizingly expounded Sanskrit scriptures they

themselves only vaguely understood. Buddhism's reputation for

powerful magic soon demoralized the simple religion of Shinto,

with its unpretentious shrines and rites, and this benign nature

reverence was increasingly pushed into the background. The

impact of Buddhism became so overwhelming that the alarmed

emperor finally abandoned Nara entirely to the Buddhists, and at

the close of the eighth century set up a new capital in central

Japan, known today as Kyoto.

The emperor also decided to discredit the Nara Buddhists on

their own terms, sending to China for new, competing sects. Back

came emissaries with two new schools, which soon assumed

dominance of Japanese Buddhism. The first of these was Tendai,

named after the Chinese T'ien-t'ai school. Its teachings centered

on the Lotus Sutra, which taught that the human Buddha

personified a universal spirit, evidence of the oneness permeating

all things. The Tendai school was installed on Mt. Hiei, in the

outskirts of Kyoto, giving birth to an establishment eventually to

number several thousand buildings. The monks on Mt. Hiei

became the authority on Buddhist matters in Japan for several

centuries thereafter, and later they also began meddling in affairs

of state, sometimes even resorting to arms. Tendai was, and

perhaps to some degree still is, a faith for the fortunate few. It did

not stress an idealized hereafter, since it served a class—the idle

aristocracy—perfectly comfortable in the present world. In any

case, it became the major Japanese Buddhist sect during the

Heian era (794-1185), a time of aristocratic rule.

The other important, and also aristocratic, version of

Buddhism preceding Zen was called Shingon, from the Chinese

school Chen-yen, a magical-mystery sect thriving on secrecy and

esoteric symbolism. It appealed less to the intellect than did

Tendai and more to the taste for entertainment among the bored

aristocrats. Although Shingon monasteries often were situated in

remote mountainous areas, the intrigue of their engaging

ceremonies (featuring efflorescent iconography, chants, and

complex liturgies) and their evocative mandalas (geometrical

paintings full of symbolism) made this sect a theatrical success.

This so-called Esoteric Buddhism of Shingon grew so popular that

the sober Tendai sect was obliged to start adding ritualistic

complexity into its own practices.4

The Japanese government broke off relations with China less

than a hundred years after the founding of Kyoto, around the

middle of the ninth century. From then until the mid-twelfth

century mainland contacts virtually ceased, and consequently

both Japanese culture and Japanese Buddhism gradually evolved

away from their Chinese models. The Japanese aristocracy

became obsessed with aesthetics, finery, and refined lovemaking

accompanied by poetry, perfumes, and flowers.5 They distilled

the vigorous T'ang culture to a refined essence, rather like

extracting a delicate liqueur from a stout potion.

The Buddhist church also grew decadent, even as it grew

ever more powerful and ominous. The priesthood became the

appointment of last resort for otherwise unemployable courtiers,

and indeed Buddhism finally degenerated largely into an

entertainment for the ruling class, whose members were amused

and diverted by its rites. This carefree aristocracy also allowed

increasing amounts of wealth and land to slip into the hands of

corrupt religious establishments. For their own part, the Buddhists

began forming armies of monks to protect their new wealth, and

they eventually went on to engage in inter-temple wars and

threaten the civil government.

During this time, the Japanese aristocracy preserved its

privileged position through the unwise policy of using an emerging

military class to maintain order. These professional soldiers seem

to have arisen from the aristocacy itself. Japanese emperors had

a large number of women at their disposal, through whom they

scattered a host of progeny, not all of which could be maintained

idle in Kyoto. A number of these were sent to the provinces,

where they were to govern untamed outlying areas. This

continued until one day the court in Kyoto awoke to find that

Japan was in fact controlled by these rural clans and their

mounted warriors, the samurai.6

In the middle of the twelfth century, the samurai effectively

seized Japan, and their strongman invented for himself the title of

shogun, proceeding to institute what became almost eight

centuries of unbroken warrior rule. The age of the common man

had arrived, and one of the shogun's first acts was to transfer the

government away from aristocratic Kyoto, whose sophisticated

society made him uncomfortable, to a warrior camp called

Kamakura, near the site of modern Tokyo. The rule of Japan

passed from perfumed, poetry-writing aesthetes to fierce, often

illiterate swordsmen.

Coincident with this coup, the decadence and irrelevance of

traditional Buddhism had begun to weigh heavily upon a new

group of spiritual reformers. Before long Tendai and Shingon

were challenged by new faiths recognizing the existence and

spiritual needs of the common people. One form this reformation

took was the appearance of new sects providing spiritual comfort

to the masses and the possibility of eternal salvation through

some simple act, usually the repetition of a sacred chant. One,

and later two, such sects (Jodo and Jodo Shin) focused on the

Buddhist figure Amida, whose Paradise or "Pure Land" in the

hereafter was open to all those calling upon his name (by

chanting a sort of Buddhist "Hail Mary" called the nembutsu,

"Praise to Amida Buddha"). Another simplified sect preached a

fundamentalist return to the Lotus Sutra and was led by a

firebrand named Nichiren, who also created a chant for his largely

illiterate followers. A formula guaranteeing Paradise had particular

appeal to the samurai, whose day-to-day existence was

dangerous and uncertain. The scandalized Tendai monks

vigorously opposed this home-grown populist movement,

occasionally even burning down temples to discourage its growth.

But the Pure Land and Nichiren sects continued to flourish, since

the common people finally had a Buddhism all their own.

There were others, however, who believed that the

aristocratic sects could be reformed from within—by importing

them afresh from China, from the source. These reformers hoped

that Buddhism in China had maintained its integrity and discipline

during the several centuries of separation. And by fortunate

coincidence, Japanese contacts with the mainland were being

reopened, making it again allowable to undertake the perilous sea

voyage to China. But when the first twelfth-century Japanese

pilgrims reached the mainland, they were stunned to find that

traditional Buddhism had been almost completely supplanted by

Ch'an. Consequently, the Japanese pilgrims returning from China

perforce returned with Zen, since little else remained. However,

Zen was not originally brought back to replace traditional

Buddhism, but rather as a stimulant to restore the rigor that had

drained out of monastic life, including formal meditation and

respect or discipline.7

Credit for the introduction of Lin-chi Zen (called Rinzai) in

Japan is traditionally given to the aristocratic priest and traveler

Myoan Eisai (1141-1215).8 He began his career as a young monk

in the Tendai complex near Kyoto, but in the summer of 1168 he

accompanied a Shingon priest on a trip to China, largely to

sightsee and to visit the home of the T'ien-t'ai sect as a pilgrim.

However, the T'ien-t'ai school must have been a mere shadow of

its former self by this time, and naturally enough Eisai became

familiar with Ch'an. But he was hardly a firebrand for Zen, for

when he returned to Japan he continued practice of traditional

Buddhism.

Some twenty years later, in 1187, Eisai again journeyed to

China, this time planning a pilgrimage on to India and the

Buddhist holy places. But the Chinese refused him permission to

travel beyond their borders, leaving Eisai no choice but to study

there. He finally attached himself to an aging Ch'an monk on Mt.

T'ien-t'ai and managed to receive the seal of enlightenment

before returning to Japan in 1191, quite probably the first

Japanese ever certified by a Chinese Ch'an master. He was not,

however, totally committed to Zen. His Ch'an teacher was also

occupied with other Buddhist schools, and what Eisai brought

back was a Buddhist cocktail blended from several different

traditions.9 But he did proceed to build a temple to the Huang-lung

(Japanese Oryo) branch of the Lin-chi sect on the southernmost

Japanese island, Kyushu (the location nearest China), in the

provincial town of Hakata. Almost as important, he also brought

back the tea plant (whose brew was used in China to keep drowsy

monks awake during meditation), thereby instituting the long

marriage of Zen and tea.

Although his provincial temple went unchallenged, later

attempts to introduce this new sect into Kyoto, the stronghold of

traditional Buddhism, met fierce resistance from the

establishment, particularly Tendai. But Eisai contended that Zen

was a useful sect and that the government would reap practical

benefits from its protection. His spirited defense of Zen, entitled

"Propagation of Zen for the Protection of the Country," argued that

its encouragement would be good for Japanese Buddhism and

therefore good for Japan.10

As in India, so in China its teaching has attracted followers and

disciples in great numbers. It propagates the Truth as the ancient

Buddha did, with the robe of authentic transmission passing from

one man to the next. In the matter of religious discipline, it

practices the genuine method of the sages of old. Thus the Truth

it teaches, both in substance and appearance, perfects the

relationships of master and disciple. In its rules of action and

discipline, there is no confusion of right and wrong. . . . Studying

it, one discovers the key to all forms of Buddhism; practicing it,

one's life is brought to fulfillment in the attainment of

enlightenment. Outwardly it favors discipline over doctrine,

inwardly it brings the Highest Inner Wisdom. This is what the Zen

sect stands for.11

He also pointed out how un-Japanese it would be to deny Zen a

hearing: Japan has been open-minded in the past, why should

she reject a new faith now?

In our country the [emperor] shines in splendor and the influence

of his virtuous wisdom spreads far and wide. Emissaries from the

distant lands of South and Central Asia pay their respects to his

court. Lay ministers conduct the affairs of government; priests and

monks spread abroad religious truth. Even the truths of the Four

Hindu Vedas are not neglected. Why then reject the five schools

of Zen Buddhism?12

Eisai was the classic tactician, knowing well when to fight and

when to retire, and he decided in 1199 on a diversionary retreat to

Kamakura, leaving behind the hostile, competitive atmosphere of

aristocratic Kyoto. Through his political connections, he managed

to get installed as head of a new temple in Kamakura, beginning

Zen's long association with the Japanese warrior class.

Eisai seems to have done well in Kamakura, for not long after

he arrived, the current strongman gave him financing for a Zen

temple in Kyoto, named Kennin-ji and completed in 1205. Eisai

returned the favor by assisting in the repair of temples ravaged by

the recent wars. It was reportedly for a later, hard-drinking ruler

that Eisai composed his second classic work, "Drink Tea and

Prolong Life," which championed the medicinal properties of this

exotic Chinese beverage, declaring it a restorative that tuned up

the body and strengthened the heart.

In the great country of China they drink tea, as a result of which

there is no heart trouble and people live long lives. Our country is

full of sickly-looking, skinny persons, and this is simply because

we do not drink tea. Whenever one is in poor spirits, one should

drink tea. This will put the heart in order and dispel all illness.

When the heart is vigorous, then even if the other organs are

ailing, no great pain will be felt. . . . The heart is the sovereign of

the five organs, tea is the chief of the bitter foods, and bitter is the

chief of the tastes. For this reason the heart loves bitter things,

and when it is doing well all the other organs are properly

regulated. . . . When, however, the whole body feels weak,

devitalized, and depressed, it is a sign that the heart is ailing.

Drink lots of tea, and one's energy and spirits will be restored to

full strength.13

This first Zen teacher was certainly no Lin-chi. He was merely

a Tendai priest who imported Lin-chi's sect from China hoping to

bring discipline to his school; he established an ecumenical

monastery at which both Zen and esoteric Tendai practices were

taught; he consorted with leaders whose place was owed to a

military coup d'etat; and he appeared to advocate Zen on

transparently practical, sometimes almost political, grounds. He

compromised with the existing cults to the end, even refusing to

lend aid to other, more pure-minded advocates of Ch'an who had

risen in Kyoto in the meantime.14 But Eisai was a colorful figure

whom history has chosen to remember as the founder of Zen in

Japan, as well as (perhaps equally important) the father of the cult

of tea.

Eisai ended his days as abbot of the Kyoto temple of Kennin-ji

and leader of a small Zen community that was careful not to

quarrel with the powers of Tendai and Shingon, which also had

altars in the temple. Eisai's "Zen" began in Japan as a minor

infusion of Buddhism's original discipline, but through an

accommodation with the warrior establishment, he accidentally

planted the seeds of Ch'an in fertile soil. Gradually the number of

Zen practitioners grew, as more and more of the samurai

recognized in Zen a practical philosophy that accorded well with

their needs. As Paul Varley has explained: "Zen . . . stresses

cultivation of the intuitive faculties and places a high premium on

discipline and self-control. It rejects rational decision-making as

artificial and delusory, and insists that action must come from

emotion. As such, Zen proved particularly congenial to the

medieval samurai, who lived with violence and imminent death

and who sought to develop such things as 'spontaneity of conduct'

and a 'tranquility of heart' to meet the rigours of his profession.

Under the influence of Zen, later samurai theorists especially

asserted that the true warrior must be constantly prepared to

make the ultimate sacrifice of his life in the service of his lord—

without a moment's reflection or conscious consideration."15

It can only be ironic that what began in China as a school of

meditation, then became an iconoclastic movement using koans

to beat down the analytical faculties finally emerged (in an

amalgam with other teachings) in Japan as a psychological

mainstay for the soldiers of a military dictatorship. There was,

however, another Japanese school of Zen that introduced its

practice in a form more closely resembling original Ch'an. This

was the movement started by Dogen, whose life we may now

examine.1. This anecdote is in Martin Charles Collcutt, "The Zen Monastic

Institution in Medieval Japan" (Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard

University, 1975).

2. Although there were various attempts to introduce Ch'an into

Japan prior to the twelfth century, nothing ever seemed to

stick. Dumoulin (History of Zen Buddhism, pp. 138-39)

summarized these efforts as follows: "The first certain

information we possess regarding Zen in Japan goes back to

the early period of her history. The outstanding Japanese

Buddhist monk during that age, Dosho, was attracted to Zen

through the influence of his Chinese teacher, Hsuan-tsang,

under whom he studied the Yogacara philosophy (653). . . .

Dosho thus came into immediate contact with the tradition of

Bodhidharma and brought the Zen of the patriarchs to Japan.

He built the first meditation hall, at a temple in Nara. . . .

"A century later, for the first time in history, a Chinese Zen

master came to Japan. This was Tao-hsuan, who belonged to

the northern sect of Chinese Zen in the third generation after

Shen-hsiu. Responding to an invitation from Japanese

Buddhist monks, he took up residence in Nara and

contributed to the growth of Japanese culture during the

Tempyo period (729-749). . . . The contemplative element in

the Tendai tradition, which held an important place from the

beginning, was strengthened in both China and Japan by

repeated contacts with Zen.

"A further step in the spread of Zen occurred in the following

century when I-k'ung, a Chinese master of the Lin-chi sect,

visited Japan. He came at the invitation of the Empress

Tachibana Kachiko, wife of the Emperor Saga, during the

early part of the Showa era (834-848), to teach Zen, first at

the imperial court and later at the Danrinji temple in Kyoto,

which the empress had built for him. However, these first

efforts in the systematic propagation of Zen according to the

Chinese pattern did not meet with lasting success. I-k'ung

was unable to launch a vigorous movement. Disappointed, he

returned to China, and for three centuries Zen was inactive in

Japan."

Another opportunity for the Japanese to learn about Ch'an

was missed by the famous Japanese pilgrim Ennin, who was

in China to witness the Great Persecution of 845, but who

paid almost no attention to Ch'an, which he regarded as the

obsession of unruly ne'er-do-wells.

3. A number of books provide information concerning early

Japanese history and the circumstances surrounding the

introduction of Buddhism to Japan. General historical works of

particular relevance include: John Whitney Hall, Japan, from

Prehistory to Modern Times (New York: Delacorte, 1970);

Mikiso Hane, Japan, A Historical Survey (New York:

Scribner's, 1972); Edwin O. Reischauer, Japan: Past and

Present, 3rd ed. (New York: Knopf, 1964); and George B.

Sansom, A History of Japan, 3 vols. (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford

University Press, 1958-63).

Studies of early Japanese Buddhism may be found in:

Masaharu Anesaki, History of Japanese Religion (London:

Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1930: reissue, Rutland, Vt.:

Tuttle, 1963); William K. Bunce, Religions in Japan (Rutland,

Vt.: Tuttle, 1955); Ch'en, Buddhism in China; Eliot, Japanese

Buddhism; Shinsho Hanayama, A History of Japanese

Buddhism (Tokyo: Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai, 1966); and E. Dale

Saunders, Buddhism in Japan (Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press, 1964).

4. In fact, the popularity of esoteric rituals was such that they

were an important part of early Zen practice in Japan.

5. This world is well described by Ivan Morris in The World of the

Shining Prince: Court Life in Ancient Japan (New York: Knopf,

1964). A discussion of the relation of this aesthetic life to the

formation of Japanese Zen may be found in Thomas Hoover,

Zen Culture (New York: Random House, 1977; paperback

edition, New York: Vintage, 1978).

6. One of the most readable accounts of the rise of the Japanese

military class may be found in Paul Varley, Samurai (New

York: Delacorte, 1970; paperback edition, New York: Dell,

1972).

7. This theory is advanced eloquently in Collcutt, "Zen Monastic

Institution in Medieval Japan." In later years the Ch'an sect in

China itself actually entered a phase of decadence, with the

inclusion of esoteric rites and an ecumenical movement that

advocated the chanting of the nembutsu by Ch'anists—some

of whom claimed there was great similarity between the

psychological aspects of this mechanical chant and those of

the koan.

8. Accounts of Eisai's life may be found in Dumoulin, History of

Zen Buddhism; and in Collcutt, "Zen Monastic Institution in

Medieval Japan."

9. See Collcutt, "Zen Monastic Institution in Medieval Japan."

10. See Saunders, Buddhism in Japan, p. 221.

11. Translated in Wm. Theodore de Bary, ed. Sources of

Japanese Tradition, Vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University

Press, 1958), pp. 236-37.

12. Ibid., p. 237.

13. De Bary, Sources of Japanese Tradition, pp. 239-40.

14. Again the best discussion of this intrigue is provided by

Collcutt, "Zen Monastic Institution in Medieval Japan."

15. Varley, Samurai, p. 45.

Idézet Eiszai röpiratából „A teaivás gyógyító hatása”

(Miklós Pál: A Zen és a mûvészet, Magvető Kiadó, Budapest, 1978)

"A tea a legcsodásabb orvosság egészségünk ápolására; ez a hosszú élet elixírje. Domboldalakon sarjad, mintegy a föld leheleteként. Akik szedik és használják, magas kort remélhetnek. India is, Kína is nagyra tartja, s az elmúlt időkben a mi országunk is kedvet kapott már egyszer a teához. Most is, mint akkor, ritka jó tulajdonságokkal bír, bízvást terjeszthetjük hát élvezetét.

A régi időkben, azt mondják, az emberek az Éggel egy kort értek meg, mostanság azonban az ember fokozatosan lehanyatlott és elgyöngült, vagyis testének négy alkotórésze és öt szerve elfajzott. Ennek okáért megesik az is, hogy ha a tûszúrásos és moxaégetéses kezeléshez folyamodnak, végzetes lesz az eredmény, és meleg tavaszokon teljesen hatástalan a kezelés. Olyannyira, hogy akik alávetik magukat ezeknek a gyógyászati eljárásoknak, szakadatlan gyöngülnek, mígnem a halál elviszi őket, és ettől a félelem nem óv meg. Ha pedig ezeket a hagyományos gyógykezeléseket ma is változatlanul tovább alkalmazzák a betegekre, bajosan remélhetnek valami enyhülést.

Mindazon dolgok közül, amelyeket az Ég teremtett, az ember a legnemesebb. Megőrizni életünket, megtenni minden lehetségest az osztályrészünkül jutott arasznyi létért okos és helyénvaló. Az élet megőrzésének az alapja egészségünk ápolása; az egészség titka pedig az öt szerv jó mûködésében rejlik. Az öt szerv uralkodója a szív, márpedig a szív erősítésének a legkitûnőbb módja a teaivás. Ha a szív gyönge, az összes többi szerv megsínyli azt. Immáron több mint kétszer ezer esztendeje, hogy a hírneves orvos, Dzsiva, Indiában eltávozott az élők sorából, s a mostani elfajzott időkben senki sincs már, aki akkurátusan meg tudná határozni a vér keringését. Több mint háromszor ezer esztendeje, hogy a kínai orvos, Sen-nung, eltûnt a földről, s ma senki sincs, aki helyesen tudná előírni az orvosságokat. Minthogy senki sincs, akitől tanácsot lehetne kérni efféle dolgokban, betegség, kór, nyavalya és pusztulás egymást követik végtelen sorban. Ha pedig a gyógyászati módban hibát vétünk, például moxaégetésnél, abból nagy ártalom származhatik. Valaki azt mondotta nékem, hogy az orvosságokat ma úgy használják, hogy gyakorta megkárosítják a szívet, mert a főzetek nem felelnek meg a betegségeknek. A moxaégetés sokszor idő előtt halált hoz, mert a lüktetés ellentétben van a moxával. Úgy vélem tehát, tanácsos lenne felülvizsgálni ezeket a gyógymódokat aszerint, ahogyan én megismertem őket Kínában. Két fő megközelítést mutatok be a manapság elterjedt betegségek megismerésére, azt remélve, hogy másoknak is hasznára lehetek majd.

Első : az Öt Szerv Mûködésének Összhangja.

A Pokol Meghódítása címen ismert titkos könyv szerint a máj a savas táplálékot kedveli, a tüdő a csípőset, a szív a keserût, a lép az édeset, a vese pedig a sósat. ... Így hát az öt szerv mindegyikének megvan a saját ízbeli kedvence. Ha közülük valamelyiket túlzott előnyben részesítjük, a megfelelő szerv túlságosan megerősödik, elnyomja a többit, s így betegség okozója lesz. Manapság savanyút, csípőset, édeset és sósat nagy mennyiségben eszünk, de keserû ételt nem. Csakhogy, ha a szív megbetegszik, azt minden szerv és érzék megsínyli. Mármost (keserût) enni lehet, de hányingerünk támad, s abba kell hagyni az evést. Ha azonban teát iszunk, a szív meg fog erősödni, és mentes lesz a betegségektől. Jó tudni, hogy ha a szívnek valami baja van, a bőr színe megfakul, ami annak a jele, hogy az élet fogyóban van. Csodálkozom, hogy a japánok nem törődnek azzal, hogy keserû táplálékot is fogyasszanak. Kína nagy országában teát isznak, aminek következtében nincsenek szívbetegségek, és a nép hosszú életû. A mi országunk tele van bágyadt, sovány emberekkel, s ennek egyszerûen az az oka, hogy nem isznak teát. Ez rendbe hozza a szívet, és elûzi a kórt. Ha a szív élénk, akkor, még ha a többi szervek nincsenek is jól, nem lesz részünk nagy fájdalomban...

...A szív az öt szerv uralkodója, a tea a keserû táplálékok feje, az ízek feje pedig a keserû. Ennek okáért a szív kedveli a keserû dolgokat, márpedig ha a szív jól mûködik, az összes szervek helyesen vannak szabályozva..."