ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

玄楼奥龍 Genrō Ōryū (1720–1813)

Portrait of Genrō by Fūgai (龍満寺 Ryūman-ji, Hyōgo Prefecture)

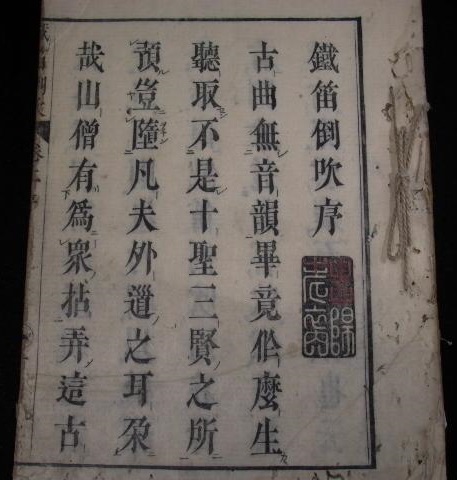

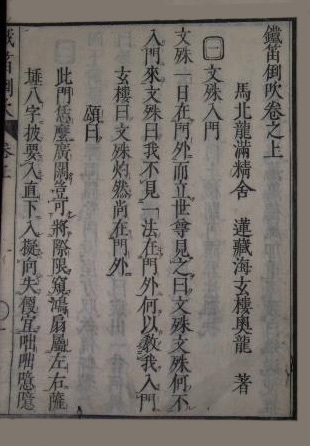

鐵笛倒吹

(Rōmaji:) Tetteki tōsui

(English:) The Iron Flute (“Blowing the [Solid-]Iron Flute Upside-Down”)

(Magyar:) Vasfurulya* / Visszáján-fújt vasfuvola**

*©Hetényi Ernő **©Terebess Gábor

Tartalom |

Contents |

A Vasfurulya verseiből (10 vers-kommentár) PDF: Vasfurulya (100 koan) > PDF (színes scan) Visszáján-fújt vasfuvola (17 koan) PDF: Vasfurulya (94 koan) Vasfurulya [E-könyv] (100 koan) |

The Iron Flute |

![]()

Tetteki tōsui 鐵笛倒吹 is found in Zoku Sōtōshū zensho 續曹洞宗全書. Edited by Zoku Sōtōshū zensho kankōkai. 10 vols. Tokyo: Sōtōshū shūmuchō, 1974–1977. [Vol.: Juko 頌古 = Verses for Ancient Koans.] The original title means “The iron flute blown upside down.”

This kōan collection had been first compiled in 1783 by Genrō Ōryū, who added his commentary to each kōan in poetry and prose. Later (1788), Genrō's chief disciple, Fūgai Honkō added his own “capping phrases”

(jakugo 著語)to the text.

Dharma lineage of Genrō & Fūgai:

永平道元 Eihei Dōgen (1200-1253)

孤雲懐奘 Koun Ejō (1198-1280)

徹通義介 Tettsū Gikai (1219-1309 )

螢山紹瑾 Keizan Jōkin (1268-1325)

峨山韶碩 Gasan Jōseki (1275-1366)

太源宗真 Taigen Sōshin (?-1371)

梅山聞本 Baizan Monpon (?-1417)

恕仲天誾 Jochū Tengin (1365-1437)

喜山性讃 Kisan Shōsan (1377-1442)

茂林芝繁 Morin Shihan (1393-1487)

崇芝性岱 Sūshi Shōtai (1414-1496)

賢仲繁喆 Kenchū Hantetsu (1438-1512)

大樹宗光 Daiju Sōkō

琴峰壽泉 Kimpō Jusen

鐵叟棲鈍 Tetsusō Seidon

舟谷長春 Shūkoku Chōshun

傑山鐵英 Ketsuzan Tetsuei

報資宗恩 Hōshi Sōon

五峰海音 Gohō Kai'on

天桂傳尊 Tenkei Denson (1648-1735)

像山問厚 Shōzan Monkō (?-1776)

二見石了 Niken Sekiryō

玄楼奥龍 Genrō Ōryū (1720–1813)

風外本高 Fūgai Honkō (1779-1847)

Senzaki Nyogen (千崎如幻 1876–1958) chose this text as an introduction to Zen Buddhism for his American students, inserting explanations and removing most of the original comments by Genrō and Fūgai:

The Iron Flute : 100 Zen Kōan with commentary by Genrō, Fūgai and Nyogen. Translated and edited by Nyogen Senzaki and Ruth Strout McCandless; illustrated by Toriichi Murashima; C. E. Tuttle, Ruthland, Vt. & Tokyo, 1961, 175 pages

Genro: Die hundert Zen-Koans der Eisernen Flöte. Hrsg von Nyogen Senzaki und Ruth Strout McCandless; Kommentar von den Zen-Meistern Genro, Fugai und Nyogen Senzaki; [Ubertr. von Ella Erhard]. Origo Verlag, Zürich, 1964, 1973. 174 S.

「鐵笛倒吹講話」 上・下 1920-1921 (東川寺蔵書)

by the 66th abbot of Eihei-ji: 日置黙仙 Hioki Mokusen (1847-1920)

PDF: The Iron Flute

Translated by Nyogen Senzaki and Ruth Strout McCandless

Foreword

THE TRANSLASTION of Tetteki Tōsui, or The Iron Flute, was begun

in June 1939 by Nyogen Senzaki, who used the stories with their

commentaries as lectures for his own students. He preferred to

dictate the story and commentary to a student, who would then

loan the manuscript to other students to copy for their own use.

When I met Mr. Senzaki, I began to collect and compile the

scattered manuscripts, and soon after was at work with him on new

translations.

Nyogen Senzaki left California in 1942, but continued to send

me translations and comments to “ polish.” On his return in 1945,

his students gathered around him, and he read his lectures. Toward

the end of this series, he considered his students well acquainted

with Zen ways, and altered the style of his translations. He now

supplied very little comment of his own, but used Genrō’s and

Fūgai’s more freely. An occasional comment by one of Nyogen’s

own group also appears in the later kōan.

Zen is a path of discipline and development unique in religion

or philosophy. A person unfamiliar with its tenets may find the

dialogues recorded here obscure, if not downright confusing. It may

even seem that every step of the way is deliberately blocked by the

teacher in an effort to conceal rather than reveal the teachings—often

even at the cost of physical pain on the part of the disciple. Since it

is impossible here to go into the history of Zen, or to clarify its

aims or methods, a bibliography has been added for the interested

reader who wishes more background.

Except for the more commonly known Japanese names of

Buddhist sects, Chinese and Japanese proper names, respectively,

have been given in their original readings. Since, however, a

number of Zen works in English have used Japanese readings for

Chinese names, an appendix has been added for the convenience of

the interested reader giving both the Japanese and Chinese names

with the original characters. Japanese names are rendered Western

style, surname last.

RUTH STROUT MCCANDLESSPreface

THE ORIGINAL of the present work was written and published in

1783 by Genrō, a Zen master of the Sōtō school in Japan. Each

story is a kōan on which the author makes his comment and writes

a poem. Fūgai, Genrō’s successor, added his remarks, sentence by

sentence, to his teacher’s book. I will translate the stories or main

subjects, including in most cases Genrō’s comments and Fūgai’s

remarks as reference. Occasionally a poem will be translated to

encourage study. Since many of Genrō’s and Fūgai’s comments

refer to old stories and customs unknown in the Occident, I shall

explain them in my commentary.

With the exception of a few stories from India, the background

is China during the T‘ang (a.d. 620–906) and Sung (930–1278)

dynasties, the Golden Age of Zen.

Tetteki Tōsui is the name of the original text. Tetteki means

“iron flute.” Usually a flute is made of bamboo with a mouthpiece

and several sideholes for the fingers, but this flute is a solid iron

rod with neither mouthpiece nor finger holes. Tōsui means “ to

blow it upside down.” The ordinary musician who wanders among

the lines of the grand staff will never be able to handle this Zen

instrument, but one who plays the stringless harp can also play

this flute with no mouthpiece.The moon floats above the pines,

And the night veranda is cold

As the ancient, clear sound comes from your finger tips.

The old melody usually makes the listeners weep,

But Zen music is beyond sentiment.

Do not play again unless the Great Sound of Lao-tsu accompanies you.HSÜEH-TOU (980–1052)

Chinese Zen MasterLao-tsu said, “Great utensils take a long time to make. Great

characters never were built in a few years. Great sound is the sound

which transcends ordinary sound.”

Now you know why the book was named Tetteki Tōsui, or

“Blowing Upside Down the Solid Iron Flute.” It is a book of the

“sound of one hand.” It is the daily life of Zen.

NYOGEN SENZAKI

The Iron Flute

selected commentary added by Genrō Ōryū, and Fūgai Honkō (Senzaki Nyogen's comments have been omitted)

1. Manjushri Enters the Gate

One day Manjushri stood outside the gate when Buddha called to him. “Manjushri, Manjushri, why do you not enter?”

“I do not see a thing outside the gate. Why should I enter?” Manjushri answered.

2. Opening Speech of Lo-shan

Lord Min-wang built a monastery for Lo-shan and asked him to make the first speech in the lecture hall. As master of the institution, Lo-shan sat on a chair, but spoke no word except, “Farewell,” before returning to his own room. Lord Min-wang approached him saying, “Even Buddha’s teaching at Gradharkuta Mountain must have been the same as yours of today.” Lo-shan answered, “I thought you were a stranger to the teaching, but now I discover you know something of Zen.”

3. Nan-ch‘üan’s Stone Buddha

Upasaka Liu-kêng said to Nan-ch‘üan, “In my house there is a stone which sits up or lies down. I intend to carve it as a Buddha. Can I do it?” Nan-ch‘üan answered, “Yes, you can.” Upasaka Liu-kêng asked again, “Can I not do it?” Nan-ch‘üan answered, “No, you cannot do it.”

GENRŌ: I see one stone which the layman carried to the monastery.

I also see another stone which Nan-ch‘üan kept in his

meditation hall. All the hammers in China cannot crush

these two stones.

4. Pai-ling’s Attainment

Pai-ling and Upasaka P‘ang-yün were studying under Ma-tsu, the successor of Nan-yüeh. One day as they met on the road, Pai-ling remarked, “Our grandfather of Zen said, ‘If one asserts that it is something, one misses it altogether.’ I wonder if he ever showed it to anyone.” Upasaka P‘ang-yün answered, “Yes, he did.” “To whom?” asked the monk. The layman then pointed his finger to himself and said, “To this fellow.”

“Your attainment,” said Pai-ling, “is so beautiful and so profound even Manjushri and Subhuti cannot praise you adequately.”

Then the layman said to the monk, “I wonder if there is anyone who knows what our grandfather in Zen meant.” The monk did not reply, but put on his straw hat and walked away. “Watch your step,” Upasaka P‘ang-yün called to him, but Pai-ling walked on without turning his head.GENRŌ:

A cloud rests at the mouth of the cave

Doing nothing all day.

The moonlight penetrates the waves throughout the night,

But leaves no trace in the water.

5. Shao-shan’s Phrase

A monk once asked Shao-shan, “Is there any phrase which is neither right nor wrong?” Shao-shan answered, “A piece of white cloud does not show any ugliness.”

GENRŌ:

Not right, not wrong.

I gave you a phrase;

Keep it for thirty years,

But show it to no one.

6. T‘ou-tzu’s Dinner

A certain Buddhist family in the capital invited T‘ou-tzu to dinner. The head of the family set a tray full of grass in front of the monk. T‘ou-tzu put his fists on his forehead and raised his thumbs like horns. He was then brought the regular dinner. Later a monk asked T‘ou-tzu to explain the reason of his strange action. “Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva,” answered T‘ou-tzu.

7. Yün-mên’s Feast in the Joss House

One day as Yün-mên gave a lecture to his monks, he asked them, “Do you want to be acquainted with the old patriarchs?” Before anyone could answer, he pointed his cane above the monks, saying, “The old patriarchs are jumping on your heads.” Then he asked, “Do you wish to see the eyes of the old patriarchs?” He pointed to the ground beneath the monks’ feet and answered himself, “They are all under your feet.” After a moment’s pause he spoke as though to himself, “I made a feast in the joss house, but the hungry gods are never satisfied.”

GENRŌ: We have only the blue sky above our heads. Where are the

old patriarchs? We have only the good earth beneath our feet.

Where are the eyes of the old patriarchs? Yün-mên’s feast

was a mere shadow, no wonder the gods could not appease

their hunger. Do you want to know how I make a feast in the

joss house? I shut the door and lie down on the floor, stretch

my arms and legs and take a nap. Why? Because there is a

saying, “A cup brim-full cannot hold any more tea. The

good earth never produced a hungry man.”

8. Yün-chü’s Instruction

Yün-chü, a Sōtō master of Chinese Zen, had many disciples. One monk, who came from Korea, said to him, “I have realized something within me which I cannot describe at all.” “Why is that so?” asked Yün-chü, “it cannot be difficult.” “Then you must do it for me,” the monk replied. Yün-chü said, “Korea! Korea!” and closed the dialogue. Later a teacher of the ōryū school of Zen criticized the incident, “Yün-chü could not understand the monk at all. There was a great sea between them, even though they lived in the same monastery.”

GENRŌ: The Ōryū monk could not understand Yün-chü. There was

a great mountain between them even though they were

contemporaries.

It is not difficult to open the mouth;

It is not difficult to describe the thing.

The monk from Korea was a wandering mendicant,

Who had not returned home as yet.

9. Tz‘u-ming’s Summary

Ts‘ui-yen, thinking he had attained something of Zen, left T‘zuming’s monastery when he was still a young monk to travel all over China. Years later, when he returned to visit the monastery, his old teacher asked, “Tell me the summary of Buddhism.” Ts‘ui-yen answered, “If a cloud does not hang over the mountain, the moonlight will penetrate the waves of the lake.” T‘zu-ming looked at his former pupil in anger, “You are getting old. Your hair has turned white, and your teeth are sparse, yet you still have such an idea of Zen. How can you escape birth and death?” Tears washed Ts‘ui-yen’s face as he bent his head. After a few minutes he asked, “Please tell me the summary of Buddhism.” “If a cloud does not hang over the mountain,” the teacher replied, “the moonlight will penetrate the waves of the lake.” Before the teacher had finished speaking, Ts‘ui-yen was enlightened.

GENRŌ: Ts‘ui-yen knew how to steer his boat with the current, but

he never dreamed of the stormy course requiring him to go

against the stream.

The bellows blew high the flaming forge;

The sword was hammered on the anvil.

It was the same steel as in the beginning,

But how different was its edge!

10. Yüeh-shan Holds It

The governor of a state asked Yüeh-shan, “I understand that all Buddhists must possess Shila (precepts), Dhyana (meditation) and Prajna (wisdom). Do you keep the precepts? Do you practice meditation? Have you attained wisdom?” “This poor monk has no such junk around here,” Yüeh-shan replied. “You must have a profound teaching,” the governor said, “but I do not understand it.” “If you want to hold it,” Yüeh-shan continued, “you must climb the highest mountain and sit on the summit or dive into the deepest sea and walk on the bottom. Since you cannot enter even your own bed without a burden on your mind, how can you grasp and hold my Zen?”

GENRŌ: Yüeh-shan uses the mountain and the sea as an

illustration. If you cling to summit or bottom, you will

create delusion. How can he hold “it” on the summit or the

bottom? The highest summit must not have a top to sit on,

and the greatest depth no place to set foot. Even this

statement is not expressing the truth. What do you do then?

(He turns to the monks.) Go out and work in the garden or

chop wood.FŪGAI: Stop! Stop! Don’t try to pull an unwilling cat over the

carpet. She will scratch and make the matter worse.

11. Chao-chou Covers His Head

A monk entered Chao-chou’s room to do sanzen, and found him sitting with his head covered by his robe. The monk retreated. “Brother,” said Chao-chou, “do not say I did not receive your sanzen.”

GENRŌ:

A white cloud hangs over the summit

Of a green mountain beyond the lake.

Whoever looks and admires the scene,

Need not waste a word.

12. San-shêng Meets a Student

One day, while talking with his monks, San-shêng said, “When a student comes, I go out to meet him with no purpose of helping him.” His brother monk, Hsing-hua, heard of the remark and said, “When a student comes, I do not often go out to meet him, but if I do, I will surely help him.”

GENRŌ: One brother says, “No,” the other says, “Yes.” Thus,

they carry the business their father left them, improving it

and making it prosper.

The Yellow River runs one thousand miles to the north,

Then turns to the east and flows ceaselessly.

No matter how it bends and turns,

Its water comes from the source in Kun-lun Mountain.

13. Ch‘ien-yüan’s Paper Screen

Ch‘ien-yüan, a master, sat behind a paper screen. A monk came for sanzen, lifted the screen, and greeted the teacher, “It is strange.” The teacher gazed at the monk then said, “Do you understand?” “No, I do not understand,” the monk replied. “Before the seven Buddhas appeared in the world,” said the teacher, “it was the same as the present moment. Why do you not understand?” Later the monk mentioned the incident to Shih-shuang, a Zen teacher of the Dharma family, who praised Ch‘ien-yüan, saying, “Brother Ch‘ien-yüan is like a master archer. He never shot an arrow without hitting the mark.”

GENRŌ: Ch‘ien-yüan said enough when he gazed at the monk in

silence. Shih-shuang should have obliterated the words

spoken by Ch‘ien-yüan if he considered the good name of his

Dharma family.

Beneath the window midnight rain patters on banana leaves,

On the bank of the river late spring breezes play with the weeping willow.

The message of eternity comes here and there, nothing more, nothing less.

Speaking of seven Buddhas is preparing a rope after the burglar has run away!

14. Pai-yün’s Black and White

Pai-yün, a Zen master of the Sung dynasty, wrote a poem:

Where others dwell,

I do not dwell.

Where others go,

I do not go.

This does not mean to refuse

Association with others;

I only want to make

Black and white distinct.

15. Ta-t‘zu’s Inner Culture

Ta-t‘zu said to his monks, “Brothers, it is better to dig inwardly one foot than to spread Dharma outwardly ten feet. Your inner culture of one inch is better than your preaching of ten inches.” In order to balance and clarify this statement, Tung-shan said, “I preach what I cannot meditate, and I meditate what I cannot preach.”

16. Kuei-shan’s Time

Kuei-shan said to his monks, “Winter repeats its cold days every year. Last year was as cold as this year, and next year we will have the same cold weather. Tell me, monks, what the days of the year are repeating.” Yang-shan, the senior disciple, walked to the teacher and stood with his right hand covering the fist of his left on his breast. “I knew you could not answer my question,” Kuei-shan commented, then turned to his junior disciple, Hsiang-yen, “What do you say?” “I am sure I can answer your question,” Hsiang-yen replied. He walked to his teacher and stood with his right hand covering his left fist placed against his breast as the senior monk had done, but Kuei-shan ignored him. “I am glad the senior could not answer me,” was the teacher’s remark.

17. Ta-sui’s Turtle

A monk saw a turtle walking in the garden of Ta-sui’s monastery and asked the teacher, “All beings cover their bones with flesh and skin. Why does this being cover its flesh and skin with bones?” Ta-sui, the master, took off one of his sandals and covered the turtle with it.

GENRŌ:

Friends of my childhood

Are all well known now.

They discuss philosophy;

They write essays and criticisms.

I am getting old;

I am good for nothing.

This evening the rain is my only companion.

I burn incense and lay myself in its fragrance;

I hear the wind passing the bamboo screen at my window.

18. Lin-chi Plants a Pine Tree

One day as Lin-chi was planting a pine tree in the monastery garden, his master, Huang-po, happened along. “We have good shrubbery around the monastery, why do you add this tree?” he asked. “There are two reasons,” Lin-chi answered, “first, to beautify the monastery with this evergreen and, second, to make a shelter for monks of the next generation.” Lin-chi then tamped the ground three times with his hoe to make the tree more secure. “Your self-assertion does not agree with me,” said Huang-po. Lin-chi ignored his teacher, murmuring, “All done,” and tamped the ground three times as before. “You will cause my teaching to remain in the world,” Huang-po said.

19. Chao-chou Plans a Visit

Chao-chou was planning to visit a mountain temple, when an elder monk wrote a poem and gave it to him.

Which blue mountain is not a holy place?

Why take cane and visit Ts‘ing-liang?

If the golden lion appears in the clouds,

It is not a happy omen at all.After reading the poem, Chao-chou asked, “What is the true eye?” The monk made no answer.

20. Tê-shan Speaks of Preceding Teachers

K‘uo was attending his master, Tê-shan, one day when he said, “Old masters and sages, I suppose, have gone somewhere. Will you tell me what became of them?” “I do not know where they are,” came the reply. K‘uo was disappointed, “I was expecting an answer like a running horse, but I got one like a crawling turtle.” Tê-shan remained silent, as one defeated in an argument. The next day Tê-shan took a bath and came to the sitting room, where K‘uo served him tea. He patted the monk on the back and asked, “How is the kōan you spoke of yesterday?” “Your Zen is better today,” answered the monk. But Tê-shan said nothing, as a man defeated in an argument.

GENRŌ:

The preceding masters have hearts cold and hard as iron;

No human sentiments can judge them.

They go back and forth like a flash,

Move inwardly and outwardly like magic.

The criticisms of mankind cannot affect them.

One may climb the top of the mountain,

But he cannot search the bottom of the ocean.

Even under a true teacher one must strive hard.

Tê-shan and the monk could not dine at the same table.

21. Fên-yang’s Walking Stick

Fên-yang brought forth his walking stick and said to his monks, “Whoever understands this walking stick thoroughly can end his traveling for Zen.”

GENRŌ: All Buddhas in the past, present, and future enter

Buddhahood when they understand this walking stick. All

genealogical patriarchs reach their attainment through this

walking stick. Fên-yang’s words are correct; no one can deny

them. I must say, however, that anyone who understands the

walking stick should begin his traveling instead of ending

his journey.

A walking stick seven feet high!

Whoever understands it can swallow the universe.

One goes southward and the other eastward;

Both are within my gate.

Before they leave this gate,

They should end their journey.

Kao-t‘ing paid homage to Tê-shan across the river,

Tê-shan answered, waving his fan:

Kao-t‘ing was enlightened at that moment.

Hsüan-sha tried to climb the mountain to see his teacher,

But fell down and injured his foot;

At that moment he attained his realization,

And said “Bodhidharma did not come to China,

And his successor never went to India.”

22. Pa-ling’s Secret Transmission

A monk asked Pa-ling, “What do the words ‘secret transmission in the east and in the west’ mean?” “Are you quoting those words from the poem of the third patriarch?” Pa-ling inquired. “No,” answered the monk, “those are the words of the master Shih-t‘ou.” “It is my mistake,” Pa-ling apologized. “I am such a dotard.”

23. Hsüeh-fêng Cuts Trees

Hsüeh-fêng went to the forest to cut trees with his disciple, Chang-shêng. “Do not stop until your ax cuts the very center of the tree,” warned the teacher. “I have cut it,” the disciple replied. “The old masters transmitted the teaching to their disciples from heart to heart,” Hsüeh-fêng continued, “how about your own case?” Chang-shêng threw his ax to the ground, saying, “Transmitted.” The teacher took up his walking stick and struck his beloved disciple.

GENRŌ:

Chang-shêng had a good ax

Sharp enough to split

The trunk in two

With a single stroke.

Hsüeh-fêng used his walking stick

To sharpen the edge.

24. Nan-ch‘üan’s Buddhistic Age

Nan-ch‘üan once delayed taking his seat in the dining room. Huang-po, his disciple and chief monk, took the master’s seat instead of his own. Nan-ch‘üan came in and said, “That seat belongs to the oldest monk in this monastery. How old are you in the Buddhistic way?” “My age goes back to the time of the prehistoric Buddha,” responded Huang-po. “Then,” said Nan-ch‘üan, “you are my grandson. Move down.” Huang-po gave the seat to the master, but took the place next to it for his own.

25. Yen-t‘ou’s Water Pail

Three monks, Hsüeh-fêng, Ch‘in-shan, and Yen-t‘ou, met in the temple garden. Hsüeh-fêng saw a water pail and pointed to it. Ch‘in-shan said, “The water is clear, and the moon reflects its image.” “No, no,” said Hsüeh-fêng, “it is not water, it is not moon.” Yen-t‘ou turned over the pail.

GENRŌ:

In the garden of willows and flowers

By the tower of beautiful music

Two guests are enjoying wine,

Holding their golden cups

Under the pale light of the moon.

A nightingale starts suddenly

From the branch of a tree,

Shaking dew from the leaves.FŪGAI: Nightingale? No! It is a phoenix!

26. Hsüeh-fêng’s Punctuality

Hsüeh-fêng, the cook monk in Tung-shan’s monastery, was always punctual in serving the morning meal. One day Tung-shan asked, “What makes you keep the time so accurately?” “I watch the stars and the moon,” Hsüeh-fêng answered. “What if it rains, or is foggy, what do you then?” Tung-shan persisted, but Hsüeh-fêng remained silent.

GENRŌ: If Tung-shan asked me what I would do if it rained or

there was fog, I would answer that I watched the rain and

enjoyed the fog.FŪGAI: I beg your pardon, but I feel like cutting off your tongue

with a pair of scissors. Hsüeh-fêng has already answered.

27. Yang-shan’s Million Objects

Yang-shan asked Kuei-shan, “If a million objects come to you, what do you do?” Kuei-shan answered, “A green article is not yellow. A long thing is not short. Each object manages its own fate. Why should I interfere with them?” Yang-shan paid homage with a bow.

28. Lung-ya’s Ultimate Stage

A monk asked Lung-ya, “What did old masters attain when they entered the ultimate stage?” “They were like burglars sneaking into a vacant house,” came the reply.

GENRŌ:

He walked the blade of a sword;

He stepped on the ice of a frozen river;

He entered the vacant house;

His desire to steal ceased forever.

He returned to his own home,

Saw the beautiful rays of the morning sun,

And watched the moon and stars intimately.

He walked the streets with ease,

Enjoying the gentle breeze.

At last he opened his treasure house.

Until that moment he never dreamed

He had owned those treasures from the very beginning.

29. Yang-shan’s Greeting

At the end of a seclusion of one hundred days, Yang-shan greeted his teacher, Kuei-shan. “I did not see you around here all summer,” said Kuei-shan, “What were you doing?” “I have been cultivating a piece of land,” replied Yang-shan, “and produced a basketful of millet.” “You did not pass this summer in vain,” Kuei-shan commented. “What were you doing this summer?” inquired Yang-shan. The old monk answered, “I ate once a day at noon and slept a few hours after midnight.” “Then you did not pass this summer in vain,” Yang-shan responded and with these words stuck out his tongue. “You should have some self-respect,” Kuei-shan observed.

GENRŌ:

None of the monks wasted precious time

In the old monastery of Kuei-shan.

Each monk glorified Buddha-Dharma

Working in silence, ignoring loss and gain.

Pet birds have red strings on their legs;

They are still strings, no matter how attractive.

Monks must not be attached to their freedom.

One sticks out his tongue to escape a blow—

Given with loving-kindness—

To sever all strings of mind and body.

30. T‘ai-tsung’s Dream

Emperor T‘ai-tsung of the Sung dynasty one night dreamed of a god who appeared and advised him to arouse his yearning for supreme enlightenment. In the morning His Majesty asked the official priest, “How can I arouse yearning for supreme enlightenment?” The priest said no word.

FŪGAI: His Majesty was still dreaming when he questioned the

official priest. The servants should prepare a basin of blue

jade, a snow-white cloth, and some icy water to wash his

face. The official priest should be dismissed from his post

because he failed to assist the emperor to stay awake all the

time. When he was asked a question, he said no word,

neglected his duty, and was good for nothing.

GENRŌ: Were I the priest, I would have said, “ Your Majesty, you

should have asked that question of the god in your dream.”FŪGAI: I wonder if my teacher was ever acquainted with the god of

whom the emperor spoke. Even if he were, his advice was

too late.

31. Kuei-shan Summons Two Official Monks

Master Kuei-shan sent for the treasurer, but when the treasurer monk appeared, Kuei-shan said, “I called the treasurer, not you.” The treasurer could not say a word. The master next sent for the chief monk, but when he arrived, Kuei-shan said, “I sent for the chief monk, not you.” The chief monk could not say a word.

32. Fên-yang Punishes the Sky

A monk asked Fên-yang, “If there is no bit of cloud in the sky for ten thousand miles, what do you say about it?” “I would punish the sky with my stick,” Fên-yang replied. “Why do you blame the sky?” the monk persisted. “Because,” answered Fên-yang, “there is no rain when we should have it and there is no fair weather when we should have it.”

33. Yüeh-shan Solves a Monk’s Problem

After a lecture to the monks one morning, Yüeh-shan was approached by a monk, who said, “I have a problem. Will you solve it for me?” “I will solve it at the next lecture,” Yüeh-shan answered. That evening, when all the monks had gathered in the hall, Yüeh-shan called out loudly, “The monk who told me this morning he had a problem, come up here immediately.” As soon as the monk stepped forward to stand in front of the audience, the master left his seat and took hold of the monk roughly. “Look here, monks,” he said, “this fellow has a problem.” He then pushed the monk aside and returned to his room without giving his evening lecture.

FŪGAI: Why, my dear brother, you have such a treasure for

meditation. Without a problem, how can one meditate

intensely? Do not ask the help of a master or anyone. The

master solved your problem this morning, but you did not

realize it. This evening he gives a dramatic lecture, pouring

out all he has in his heart.

34. Hsüeh-fêng Sees His Buddha-nature

A monk said to Hsüeh-fêng, “I understand that a person in the stage of Shravaka sees his Buddha-nature as he sees the moon at night, and a person in the stage of Bodhisattva sees his Buddha-nature as he sees the sun at day. Tell me how you see your own Buddha-nature.” For answer Hsüeh-fêng gave the monk three blows with his stick. The monk went to another teacher, Yen-t‘ou, and asked the same thing. Yen-t‘ou slapped the monk three times.

35. Li-hsi’s Poem

Li-hsi,* who lived thirty years on Tzu-hu Mountain, wrote a poem:

For thirty years I have lived on Tzu-hu Mountain.

I have taken simple meals twice a day to feed my body;

I have climbed the hills and returned to my hut to exercise my body.

None of my contemporaries would recognize me.*子湖利蹤 Zihu Lizong [Tzu-hu Li-tsung] (800-880), Shiko Rishō

GENRŌ:

When inclined, he climbs the mountain;

In his leisure, white clouds are his companions;

In quietude, he has everlasting gladness.

None but Zen students can partake of such pleasure.

36. Where to Meet After Death

Tao-wu paid a visit to his sick brother monk, Yün-yen. “Where can I see you again, if you die and leave only your corpse here?” asked the visitor. “I will meet you in the place where nothing is born and nothing dies,” answered the sick monk. Tao-wu was not satisfied with the answer and said, “What you should say is that there is no place in which nothing is born and nothing dies, and that we need not see each other at all.”

GENRŌ: Tao-wu loses everything and Yün-yen gains all. The latter

said, “I will meet you,” and the former said, “We need not

see each other at all.” They need not see each other, therefore,

they meet. They meet each other because there is no need to

see each other.

True friendship transcends intimacy or alienation:

Between meeting and not meeting, there is no difference.

On the old plum tree, fully blossomed,

The southern branch owns the whole spring,

As also does the northern branch.

37. Hsüeh-fêng’s Sanctity

A monk asked Hsüeh-fêng, “How can one touch sanctity?” Hsüeh-fêng answered, “A mere innocent cannot do it.” “If he forgets himself,” the monk asked again, “can he touch sanctity?” “He may do so in so far as he is concerned,” Hsüeh-fêng replied. “Then,” continued the monk, “what happens to him?” “A bee never returns to his abandoned hive,” came the answer.

38. Going and Returning

A monk asked his master, “What do you think of a monk who goes from the monastery and never returns?” The teacher said, “He is an ungrateful ass.” The student asked again, “What do you think of a monk who goes out of the monastery, but comes back again?” The teacher said, “He remembers the benefits.”

GENRŌ: If I were asked, “What do you think of a monk who goes

from the monastery and never returns?” I would say, “He is

a fool!” And on the question, “What do you think of a monk

who goes out of the monastery only to return?” I would

answer, “He is an escaping fox.”

39. Three Calls

Chung-kuo-shih, teacher of the emperor, called to his attendant, “Ying-chên.” Ying-chên answered, “Yes.” Chung-kuo-shih, to test his pupil, repeated, “Ying-chên.” Ying-chên answered, “Yes.” Then Chung-kuo-shih called, “Ying-chên,” for the third time. Ying-chên answered, “Yes.” “I ought to apologize to you for all this calling,” said Chung-kuo-shih, “but really you should apologize to me.”

GENRŌ: The old master was kindhearted enough, and the young

pupil served him selflessly. Why the apologies? Because

human affairs are very uncertain. One should not set himself

in any mold of life if he wishes to live freely.

40. The Dry Creek

A monk asked Hsüeh-fêng, “When the old creek of Zen dries out and there is not a drop of water left, what can I see there?” Hsüeh-fêng answered, “There is the bottomless water, which you cannot see.” The monk asked again, “How can one drink that water?” Hsüeh-fêng replied, “He should not use his mouth to do it.”

This monk later went to Chao-chou and related the dialogue. Chao-chou said, “If one cannot drink the water with his mouth, he also cannot take it through his nostrils.” The monk then repeated the first question, “When the old creek of Zen dries out and there is not a drop of water, what can I see there?” Chao-chou answered, “The water will taste as bitter as quinine.” “What happens to one who drinks that water?” asked the monk. “He will lose his life,” came the reply.

When Hsüeh-fêng heard of the dialogue, he paid homage to Chao-chou saying, “Chao-chou is a living Buddha. I should not answer any questions hereafter.” From that time on he sent all newcomers to Chao-chou.

41. Tung-shan’s Tripitaka

Tung-shan, a Zen master, said, “The Tripitaka, the whole collection of Buddhist scriptures, can be expressed with this one letter.” Pai-yün, another master, illustrated the words of Tung-shan with a poem:

Each stroke of this letter is clear, but no reason accompanies it.

Buddha tried to write it, failing many a time.

Why not give the job to Mr. Wang, master of calligraphy?

His skillful hand may accomplish the requirement beautifully.

42. The Southern Mountain

Shih-shuang lived on the Southern Mountain and Kuan-ch‘i lived on the Northern Mountain. One day a monk came from the Northern Monastery to the Southern Monastery, and Shih-shuang said to him, “My Southern Monastery is not superior to the monastery in the north.” The monk did not know what to say, so kept silent. When the monk returned to Kuan-ch‘i and told him what Shih-shuang had said, Kuan-ch‘i remarked, “You should tell him I am ready to enter Nirvana most any day.”

43. The Ultimate Truth of Zen

A monk asked Hsüan-sha, “When the old masters preached Dharma wordlessly with a gavel or mosquito brush, were they expressing the ultimate truth of Zen?” Hsüan-sha answered, “No.” “Then,” continued the monk, “what were they showing?” Hsüan-sha raised his mosquito brush. The monk asked, “What is the ultimate truth of Zen?” “Wait until you attain realization,” Hsüan-sha replied.

GENRŌ: If I were Hsüan-sha, I would throw down the brush instead

of making such a lukewarm speech.FŪGAI: My teacher’s words may be good to help Hsüan-sha, but it

is a pity he had to use a butcher’s knife to carve a chicken.

44. Nan-ch‘üan Rejects Both Monk and Layman

A monk came to Nan-ch‘üan, stood in front of him, and put both hands to his breast. Nan-ch‘üan said, “You are too much of a layman.” The monk then placed his hands palm to palm. “You are too much of a monk,” said Nan-ch‘üan. The monk could not say word. When another teacher heard of this, he said to his monks, “If I were the monk, I would free my hands and walk away backward.”

GENRŌ: If I were Nan-ch‘üan, I would say to the monk, “You are

too much of a dumb-bell,” and to the master, who said he

should free his hands and walk backward, “You are too

much of a crazy man.” True emancipation has nothing to

hold to, no color to be seen, no sounds to be heard.

A free man has nothing in his hands.

He never plans anything, but reacts according to others’ actions.

Nan-ch‘üan was a skillful teacher

He loosed the noose of the monk’s own rope.

45. Yü-ti Asks Buddha

Yü-ti, the Premier, asked Master Tao-t‘ung, “What is Buddha?” The master called abruptly, “Your Excellency!” “Yes,” answered the Premier innocently. Then the master said, “What else do you search for?”

GENRŌ: His Excellency certainly bumped his head on something,

but I am not sure whether it was a real Buddha or not.

Do not search for fish in the tree top;

Do not boil bamboo when you return home.

Buddha, Buddha, and Buddha. . . .

A fool holds but a string for coins.

46. The Ideograph for Mind

An old monk wrote the Chinese ideograph for “mind” on the gate, window, and wall of his little house. Fa-yen thought it wrong and corrected it, saying, “The gate must have the letter for ‘gate’, and the window and wall each its own letter.” Hsüan-chüeh said, “The gate shows itself without a letter, so the window and wall need no sign at all.”

GENRŌ: I will write the letter “window” on the gate, the letter

“wall” on the window, and the letter “gate” on the wall.

47. Chao-chou Measures the Water

One day Chao-chou visited his brother monk’s lecture hall. He stepped up to the platform, still carrying his walking stick, and looked from east to west and from west to east. “What are you doing there?” asked the brother monk. “I am measuring the water,” answered Chao-chou. “There is no water. Not even a drop of it. How can you measure it?” questioned the monk. Chao-chou leaned his stick against the wall and went away.

48. Ti-ts‘ang’s Buddhism

One day Ti-ts‘ang received one of Pao-fu’s disciples as a guest and asked him, “How does your teacher instruct you in Buddhism?” “Our teacher,” replied the monk, “tells us to shut our eyes and see no evil thing; to cover our ears and hear no evil sound; to stop the activities of our minds and form no wrong idea.” “I do not ask you to cover your eyes,” Ti-ts‘ang said, “but you do not see a thing. I do not ask you to cover your ears, but you do not hear a sound. I do not ask you to stop your activities of mind, but you do not form any idea at all.”

GENRŌ: I do not ask you to shut your eyes. I do not ask you not to

shut your eyes. Just tell me what your eyes are. I do not ask

you to cover your ears. I do not ask you not to cover your

ears. Just tell me what your ears are. I do not ask you to stop

your activities of mind. I do not ask you not to stop your

activities of mind. Just tell me what the mind is.

49. Hsüan-sha’s Blank Paper

Hsüan-sha sent a monk to his old teacher, Hsüeh-fêng, with a letter of greeting. Hsüeh-fêng gathered his monks and opened the letter in their presence. The envelope contained nothing but three sheets of blank paper. Hsüeh-fêng showed the paper to the monks, saying, “Do you understand?” There was no answer, and Hsüeh-fêng coninued, “My prodigal son writes just what I think.” When the messenger monk returned to Hsüan-sha, he told him what had happened at Hsüeh-fêng’s monastery. “My old man is in his dotage,” said Hsüan-sha.

50. I-chung Preaches Dharma

When master I-chung had taken his seat to preach Dharma, a layman stepped from the audience and walked from east to west in front of the rostrum. A monk then demonstrated his Zen by walking from west to east. “The layman understands Zen,” said I-chung, “but the monk does not.” The layman approached I-chung saying, “I thank you for your approval,” but before the words were ended, he was struck with the master’s stick. The monk approached and said, “I implore your instruction,” and was also struck with the stick. I-chung then said, “Who is going to conclude this kōan?” No one answered. The question was repeated twice, but there was still no answer from the audience. “Then,” said the master, “I will conclude it.” He threw his stick to the floor and returned to his room.

51. Pao-fu’s Temple

One day Pao-fu said to his monks, “When one passes behind the temple, he meets Chang and Li, but he does not see anyone in front of it. Why is this? Which of the two roads is profitable to him?” A monk answered, “Something must be wrong with the sight. There is no profit without seeing.” The master scolded the monk, saying, “You stupid, the temple is always like this.” The monk said, “If it was not the temple, one should see something.” The master said, “I am talking about the temple, and nothing else.”

52. Hua-yen Return to the World of Delusion

A monk asked Hua-yen, “How does an enlightened person return to the world of delusion?” The master replied, “A broken mirror never reflects again, and the fallen flowers never go back to the old branches.”

GENRŌ: To illustrate this story, I shall quote an old Chinese

poem:

Look! The evening glow brings up

The stone wall on the lake.

A curling cloud returns to the woods

And swallows the whole village.

53. Hui-chung Expels His Disciple

Tan-hsia paid a visit to Hui-chung, who was taking a nap at the time. “Is your teacher in?” asked Tan-hsia of an attending disciple. “Yes, he is, but he does not want to see anyone,” said the monk. “You are expressing the situation profoundly,” Tan-hsia said. “Don’t mention it. Even if Buddha comes, my teacher does not want to see him.” “You are certainly a good disciple. Your teacher ought to be proud of you,” and with these words of praise, Tan-hsia left the temple. When Hui-chung awoke, Tan-yüan, the attending monk, repeated the dialogue. The teacher beat the monk with a stick and drove him from the temple.

54. Yen-t‘ou’s Two Meals

When Ch‘in-shan paid a visit to Yen-t‘ou, who was living in quiet seclusion, he asked, “Brother, are you getting two meals reguarly?” “The fourth son of the Chang family supports me, and I am very much obliged to him,” said Yen-t‘ou. “If you do not do your part well, you will be born as an ox in the next life and will have to repay him what you owed him in this life,” Ch‘in-shan cautioned. Yen-t‘ou put his two fists on his forehead, but said nothing. “If you mean horns,” said Ch‘in-shan, “you must stick out your fingers and put them on top of your head.” Before Ch‘in-shan finished speaking, Yen-t‘ou shouted, “Hey!” Ch‘in-shan did not understand what this meant. “If you know something deeper, who don’t you explain it to me?” he asked. Yen-t‘ou hissed, then said, “You have been studying Buddhism thirty years as I have and you are still wandering around. I have nothing to do with you. Just get out,” and with these words he shut the door in Ch‘in-shan's face. The fourth son of the Chang family happened to be passing and, out of pity, took Ch‘in-shan to his home nearby. “Thirty years ago we were close friends,” Ch‘in-shan remarked sorrowfully, “but now he has attained something higher than I have, he will not impart it to me.” That night Ch‘in-shan was unable to sleep and at last got up and went to Yen-t‘ou's house. “Brother, please be kind and preach the Dharma for me.” Yen-t‘ou opened the door and disclosed the teaching. The next morning the visitor returned to his home with happy attainment.

55. Mu-chou's Blockhead

When Mu-chou and a strange monk passed each other on the road, Mu-chou called, “Venerable Sir!” The monk turned. “A blockhead,” Mu-chou remarked, then each walked on again.

This anecdote was recorded by some monks, and years later Hsüeh-tou criticized it, saying, “The foolish Mu-chou was wrong. Didn’t the monk turn? Why should he have been called a blockhead?”

Later Hui-t‘ang commented on this criticism, “The foolish Hsüeh-tou was wrong. Didn’t the monk turn? Why shouldn’t he be called a blockhead?”

56. Lu-tsu Faces the Wall

When monks came for instruction in Zen or laymen came with questions, Lu-tsu would turn his back and face the wall. Nan-ch‘üan, his brother monk, criticized this method, “I tell monks to put themselves into the time before Buddha was born in the world, but few of them truly realize my Zen. Merely sitting against the wall like Brother Lu-tsu would never do the monks any good.”

GENRŌ: Do you want to meet Lu-tsu? Climb the highest mountain

to the point no human being can reach. Do you want to meet

Nan-ch‘üan? Watch a fallen leaf. Feel the approach of

autumn.

The sacred place is not remote;

No special road leads to it.

If one proceeds where a guide has pointed,

He will find only a slippery, moss-covered bridge.

57. Lin-chi's Titleless Man

Lin-chi once said to his monks, “A titleless man lives upon flesh and blood, going out or coming in through the gateways of your face. Those who have not witnessed this fact, discover it this minute!” A monk stood up and asked. “Who is a titleless man?” Lin-chi suddenly came down from his chair, seized the monk by the collar of his robe, and exclaimed, “Speak! Speak!” The monk was dumbfounded for a moment, so Lin-chi slapped him. “This titleless man is good for nothing.”

58. The Statue of Avalokiteshvara

The people of Korea once commissioned an artist in Cheh-kiang, China, to carve a life-sized wooden statue of Avalokiteshvara. The work was completed, the statue carried to Tsien-t‘ang harbor for shipment, when suddenly it seemed to be stuck fast to the beach, and no human power could move it. After negotiations between the Chinese and Koreans, it was decided to keep the statue in China. The statue then returned to its normal weight and was later enshrined at a temple in Ming-chou. A person paid homage to the statue and said, “In the sutra we read that Avalokiteshvara is the possessor of miraculous powers, and in all the lands of the ten quarters there is not a place where he does not manifest himself. Then why is it this holy statue refused to go to Korea?”

GENRŌ: Every place is the land of his manifestation, then why

should he go particularly to Korea?

One who covers his own eyes

Never sees Avalokiteshvara.

Why does he ask a foreigner

To carve a wooden statue?

The immovable statue on the beach

Is not the true Avalokiteshvara;

The enshrined statue in the temple

Is not the true Avalokiteshvara;

The empty ship returns to Korea,

But the man who opens his eyes . . .

Is he not a true Avalokiteshvara?

59. Wu-yeh's Fancies

Wu-yeh, a national teacher, said, “If one has fancies about sages or mediocrities, even though these fancies are as fine as delicate threads, they are strong enough to pull him down into the animal kingdom.”

FŪGAI: Why do you refuse the idea of sages and mediocrities?

Why are you afraid of being pulled down to lower stages? A

good actor never chooses between the roles. The poor one

always complains of his part.GENRŌ: If you want to clear both ideas of sages and mediocrities,

you must make yourselves donkeys and horses. Do not hate

enemies if you want to conquer them.

Sages and mediocrities . . .

Donkeys and horses . . .

All of them pull you down

When you hold

Even to the shadow of a single hair.

Be good, monks,

Live one life at a time

Without dualistic inertia.

Old masters know your sickness

And shed tears for you.

60. The Wooden Pillow

In Nan-ch‘üan’s monastery the cook monk was entertaining the gardener monk one day. While they were eating, they heard a bird sing. The gardener monk tapped his wooden armrest with his finger, then the bird sang again. The gardener monk repeated this action, but the bird sang no more. “Do you understand?” asked the gardener monk. “No,” answered the cook monk, “I do not understand.” The other monk struck the pillow for the third time.

GENRŌ: Birds sing naturally; the gardener monk taps the pillow

innocently. That is all. Why doesn’t the cook monk

understand? Because he has something in his mind.

61. Yün-mên's Holy Fruits

Yün-mên once lived in a temple called the “Chapel of Holy Trees.” One morning a government official called on him and asked, “Are your holy fruits well ripened now?” “None of them was ever called green by anyone,” answered Yün-mên.

GENRŌ: His Zen is not ripened. His words are lukewarm.

FŪGAI: I love that green fruit.

GENRŌ:

The rootless holy tree

Bears holy fruit.

How many are there?

One, two, three . . .

They are not red;

They are not green.

Help yourself;

They are hard as iron balls.

When the Chinese officer tried to bite

Yün-mên’s fruit of the Holy Chapel,

He lost his teeth in them.

He did not know the size was great enough

To cover heaven and earth,

And contain all sentient beings.

62. Nan-ch‘üan's Little Hut

One day, while Nan-ch‘üan was living in a little hut in the mountains, a strange monk visited him just as he was preparing to go to his work in the fields. Nan-ch‘üan welcomed him, saying, “Please make yourself at home. Cook anything you like for your lunch, then bring some of the left-over food to me along the road leading nowhere but to my work place.” Nan-ch‘üan worked hard until evening and came home very hungry. The stranger had cooked and enjoyed a good meal by himself, then thrown away all provisions and broken all utensils. Nan-ch‘üan found the monk sleeping peacefully in the empty hut, but when he stretched his own tired body beside the stranger’s, the latter got up and went away. Years later, Nan-ch‘üan told the anecdote to his disciples with the comment, “He was such a good monk, I miss him even now.”

63. Yüeh-shan's Lecture

Yüeh-shan had not delivered a lecture to his monks for some time, and at last the chief monk came to him and said, “The monks miss your lecture.” “Then ring the calling-bell,” said Yüeh-shan. When all the monks were gathered in the lecture hall, Yüeh-shan returned to his room without a word. The chief monk followed him, “You said you would give a lecture. Why don’t you do it?” “Lectures on sutras should be given by scholars of the sutras, and those on shastras by students of the shastras. Why do you bother this old monk?”

GENRŌ:

Yüeh-shan’s Zen

Is like a full moon,

Whose pale light penetrates

Thousands of miles.

Foolish ones cover their eyes

Overlooking the truth of Zen.

A bell call the monks;

The old teacher retires to his room.

What a beautiful picture of Zen!

What a profound lecture on Zen!

64. Ching-ch‘ing's Big Stick

Ching-ch‘ing asked a new monk whence he had come. The monk replied, “From Three Mountains.” Ching-ch‘ing then asked, “Where did you spend your last seclusion?” “At Five Mountains,” answered the monk. “I will give you thirty blows with the big stick,” said Ching-ch‘ing. “Why have I deserved them?” questioned the monk. “Because you left one monastery and went to another.”

65. The Most Wonderful Thing

A monk came to Pai-chang and asked, “What is the most wonderful thing in the world?” “I sit on top of this mountain,” answered Pai-chang. The monk paid homage to the teacher folding his hands palm to palm. At that moment Pai-chang hit the monk with his stick.

66. Tao-wu's Greatest Depth

Tao-wu was sitting on the high seat of meditation when a monk came and asked, “What is the greatest depth of the teaching?” Tao-wu came down from the seat to kneel on the floor saying, “You are here after traveling from afar, but I am sorry to have nothing to answer you.”

FŪGAI: Look out, brother! You are endangering yourself in the deep

sea.GENRŌ: I should say that Tao-wu certainly had the greatest depth

of his Zen.FŪGAI: I should say that my teacher knows the depth of Tao-wu’s

Zen.GENRŌ:

The great and deep sea!

No boundry in four directions!

When Tao-wu comes down

From his high seat,

There is no depth . . .

There is no water.FŪGAI:

It is beyond great and small;

It is above shallow and deep.

I fear my beloved teacher

Is in danger of drowning

Because he has a big heart

And loves all sentient beings.

67. Ch‘ien-fêng's Transmigration

Ch‘ien-fêng asked, “What kind of eyes do they have who have transmigrated in the five worlds?”

FŪGAI: What kind of eyes do those have who do not transmigrate?

GENRŌ:

The whole world is my garden.

Birds sing my song;

Winds blow as my breath;

The dancing of the monkey is mine;

The swimming fish expresses my freedom;

The evening moon is reflected

In one thousand lakes,

Yet when the mountain hides the moon,

All images will be gone

With no shadow remaining on the water.

I love each flower representing spring

And each colorful leaf of autumn.

Welcome the happy transmigration!

68. Yün-mên's Three Days

Yün-mên said to his monks one day, “There is a saying, ‘Three days can make a different person.’ What about you?” Before anyone could answer, he said quietly, “One thousand.”

FŪGAI: If I were there, I would slap Yün-mên’s cheek. Not three

days; every inhalation and exhalation may change a person.

(Then, after Yün-mên’s “One thousand.”) Yün-mên has the

same old face.GENRŌ: Yün-mên opened a bargain sale and bought himself, so

there is no loss and no gain. No one can price his “One

thousand.” I would rather say, “It is all right for his time,

but it is not all right today.” Can you not see that three days

alter a person?

69. The Government Official

Chên-ts‘ao, a government official, went upstairs with some of the members of his staff. On seeing a group of monks passing below in the road, one of the men said, “Are they traveling monks?” Chên- ts‘ao answered, “No.” “How do you know they are not traveling monks?” the staff member asked. “Let us examine them,” Chên-ts‘ao replied, then shouted. “Hey! monks!” At the sound of his voice they all looked up at the window. “There!” said Chên-ts‘ao, “didn’t I tell you so?”

GENRŌ: Chên-ts‘ao was looking southeast while his mind was

northwest.

70. Chao-chou's Dwelling Place

One day Chao-chou visited Yün-chü, who said, “Why do you not settle down in your old age?” “Where is the place for me?” asked Chao-chou. “The ruins of an old temple are here on the mountain,” Yün-chü suggested. “Then why don’t you live there?” Chao-chou asked. Yün-chü did not answer. Later Chao-chou visited Chu-yü, who asked, “Why do you not settle down in your old age?” “Where is the place for me?” questioned Chao-chou as before. “Don’t you know your own place for your old age?” Chuyü countered. Chao-chou then said, “I have practiced horseback riding for thirty years, but today I fell from a donkey.”

71. Yün-mên's Family Tradition

A monk asked Yün-mên, “What is your family tradition?” Yünmên answered, “Can you not hear the students coming to this house to learn reading and writing?”

GENRŌ: Yün-mên would not get many students in this way as

most of them came to gather attractive family traditions.FŪGAI: Probably Yün-mên has nothing to do but take the place of a

school teacher.

72. Pao-shou Turns His Back

Chao-chou visited Pao-shou, who happened to see him coming and turned his back. Chao-chou spread the mat he carried to make a bow to Pao-shou, but Pao-shou immediately stood up and returned to his room. Chao-chou picked up his mat and left.

73. Hsüeh-fêng Rejects a Monk

A monk came to Hsüeh-fêng and made a formal bow.

FŪGAI: He is using the first lesson for children.

Hsüeh-fêng hit the monk five blows with the stick.

FŪGAI: Here the kōan flares up.

At this the monk asked, “Where is my fault?”

FŪGAI: You do not know your own benefactor.

With another five blows the master shouted at the monk to get out.

FŪGAI: Too much kindness spoils a child.

GENRŌ: Hsüeh-fêng’s last shout had no value at all.

FŪGAI: Hsüeh-fêng tried to fit a square stick to a round hole.

GENRŌ:

Hsüeh-fêng’s Zen was like a grandmother’s kindness.

He marked the ship’s side for a lost sword.

It is like the old story of Lin-chi,

Who poked Ta-yü’s ribs three times.

74. The Founder of a Monastery is Selected

While Kuei-shan was studying Zen under Pai-chang, he worked as a cook for the monastery.

FŪGAI: A peaceful Zen family!

Ssu-ma T‘ou-t‘o came to the monastery to tell Pai-chang he had found a good site for a monastery on the mountain of Ta-kueishan, and wished to select a new master before the monastery was established.

FŪGAI: Who could not be the dweller?

Pai-chang asked, “How about me?”

FŪGAI: Do not joke!

Ssu-ma T‘ou-t‘o replied, “That mountain is destined to have a prosperous monastery. You are born to poverty, so, if you live there, you may have only five hundred monks.”

FŪGAI: How do you know?

“That monastery is going to have more than one thousand monks.”

FŪGAI: Is that all?

“Can you not find someone suitable among my monks?”

FŪGAI: Where is your eye to select a monk?

Ssu-ma T‘ou-t‘o continued, “I think Kuei-shan, the cook monk, will be the man.”

FŪGAI: Nonsense!

Pai-chang then called Kuei-shan to tell him he must go to establish the new monastery.

FŪGAI: Better go easy!

The chief monk happened to hear the conversation and dashed to his teacher saying, “No one can say the cook monk is better than the chief monk.”

FŪGAI: You do not know yourself.

Pai-chang then called the monks together, told them the situation, and said that anyone who gave a correct answer to his question would be a candidate.

FŪGAI: Upright judge!

Pai-chang then pointed to a water pitcher standing on the floor and asked, “Without using its name, tell me what it is.”

FŪGAI: I can see the teacher’s glaring eyes.

The chief monk said, “You cannot call it a wooden shoe.”

FŪGAI: Some chief monk!

When no one else answered, Pai-chang turned to Kuei-shan. Kuei-shan stepped forward, tipped over the pitcher with his foot, then left the room.

FŪGAI: Nothing new.

Pai-chang smiled, “The chief monk lost.”

FŪGAI: Upright judge!

Kuei-shan was made head of the new monastery, where he lived many years teaching more than one thousand monks in Zen.

FŪGAI: Not only one thousand monks, but all the Buddhas, past,

present, and future, and all the Bodhisattvas from the ten

quarters.GENRŌ: Fortunately, Pai-chang put up a pitcher as a stake so the

monk could tip it over. Suppose I point to the Southern

Mountain and say, “Do not call it the Southern Mountain,

then what do you call it?” If you say you cannot call it a

wooden shoe, you are no better than the chief monk. You

cannot tip it over as Kuei-shan did. Now, what do you do?

Anyone among you who has real Zen transcending these

opinions, answer me.FŪGAI: I will kick the teacher.

GENRŌ:

Just pick up the pitcher and measure short or long,[FŪGAI: What are you going to do with it? It has no

measure; how can you name it short or long?]Thus, transcending measurement, expose the entire contents.

[That’s what I say!]

See what one foot can do!

[Precious, incomparable foot!]

One kick and the monastery is established on Kuei-shan.

[That foot should grind emptiness to dust.]

75. A Monk in Meditation

The librarian saw a monk sitting in meditation in his library a long time.

FŪGAI: Is he not a monk?

The librarian asked, “Why do you not read the sutras?”

FŪGAI: I would like to say to the monk, “Are you not sitting in

the wrong place?” Also I would like to ask the librarian what

kind of sutra he means.The monk answered, “I do not know how to read.”

FŪGAI: A lovable illiterate!

“Why do you not ask someone who knows?” suggested the librarian.

FŪGAI: Here you have slipped.

The monk stood up, asking politely, “What is this?”

FŪGAI: Poison oak!

The librarian remained silent.

FŪGAI: Good imitation.

GENRŌ: The monk stood and the librarian remained silent.Are not

these well-written sutras?

No special light is needed to read this sutra.[FŪGAI: Fortunately, there is enough light to illumine

the darkness.]Each character is clearly illumined.

[It cannot be translated.]

Standing without touching a book,

[Why hold what you already have?]

Five thousand sutras are read in a flash.

[What of the sutra no one can read? My teacher was

tardy with this comment.]

76. Ti-ts‘ang's Peony

Ti-ts‘ang took a trip with his two elder monks, Chang-ch‘ing and Pao-fu, to see the famous painting of a peony on a screen.

FŪGAI: Monks, you should wipe the film from your eyes.

Pao-fu said, “Beautiful peony!”

FŪGAI: Do not allow your eyes to cheat you.

Chang-ch‘ing said, “Do not trust your visual organs too much.”

FŪGAI: I say, “Do not trust your auditory organs.”

Ti-ts‘ang said, “It is too bad. The picture is already spoiled.”

FŪGAI: The mouth is the cause of all trouble.

GENRŌ: Pao-fu enjoyed seeing the beautiful picture. Chang-ch‘ing

lost the opportunity of enjoying it himself because he was

minding another’s business. When Ti-ts‘ang said, “It is too

bad, the picture is already spoiled,” is he joining Pao-fu or

condemning Chang-ch‘ing?

Chao-ch‘ang skillfully painted the king of flowers.[FŪGAI: The picture needs polishing.]

Colorful brocade opens to reveal perfume within.

[A pungent fragrance is unpleasant.]

Bees and butterflies encircle the bloom with pleasure.

[Mankind also has insects attracted by flowers.]

Do the three monks discuss the real or the painted flower?

[See the sign, DO NOT TOUCH !]

77. Tung-shan's Advice

Tung-shan said to his monks, “You monks should know there is an even higher knowledge in Buddhism.”

FŪGAI: When one tries to know the higher, he falls lower.

A monk stepped forward and asked, “What is the higher Buddhism?”

FŪGAI: That monk was cheated by Buddha and the patriarchs.

Tung-shan answered, “It is not Buddha.”

FŪGAI: Selling horsemeat labeled prime beef!

GENRŌ: Tung-shan is so kind. He is like a fond grandparent who

forgets his dignity to play with the children and is heedless

of the ridicule of spectators. Followers of his teaching must

remember this and repay his kindness with gratitude.FŪGAI: When one tries to repay, he himself makes heavy debts.

GENRŌ:

Tung-shan’s Zen is decorated with virtue and meditation,[FŪGAI: It is worthless.]

Aimlessly misleading people.

[He is getting too old.]

The shadow of the bow in the glass,

[Lucky to know it is a shadow.]

Poisons the one who drinks the wine.

[One should be ashamed of himself.]

78. Yün-chü Sends Underclothing

Yün-chü, the master of a big monastery, sent underclothing to a monk living alone in a hut near the temple. He had heard that this monk sat long hours in meditation with no covering for his legs.

FŪGAI: A benefit for a skinny person. That underclothing must

have been inherited from Bodhidharma.The monk refused the gift, saying, “I was born with my own under-clothing.”

FŪGAI: Good Monk! If you have it, I will give it to you. If you do

not have it, I will take it away from you.Yün-chü sent a message asking, “What did you wear before you were born?”

FŪGAI: Yün-chü is sending new clothes.

The monk could not answer.

FŪGAI: Where are your two legs?

Later the monk died. At cremation sarira were found in the ashes and were brought to Yün-chü, who said, “Even had he left eighty-four bushels of sarira, they would not be worth the answer he failed to give me.”

FŪGAI: Government orders have no sentiment. No one can cheat a

real master.GENRŌ: I will answer Yün-chü for the monk, “ I could show you

that, but it is so large you probably have no place to put it.”FŪGAI: Good words, but not likely to be the monk’s idea.

GENRŌ:

Eighty-four bushels of sarira[FŪGAI: Bad odor!]

Cannot surpass one word that covers the universe.

[The western family sends condolences to the eastern house.]

The mother’s clothing—what a pity!

[You are ungrateful to your mother.]

It cannot cover the present unsightliness.

[Son of a millionaire stark naked.]

79. Tê-shan's Ultimate Teaching

Hsüeh-fêng asked Tê-shan, “Can I also share the ultimate teaching the old patriarchs attained?”

FŪGAI: He still has a tendency of kleptomania.

Tê-shan hit him with a stick, saying, “What are you talking about?”

FŪGAI: He is a kind old grandmother!

Hsüeh-fêng did not realize Tê-shan’s meaning, so the next day he repeated his question.

FŪGAI: Is not one head enough?

Tê-shan answered, “Zen has no words, neither does it have anything to give.”

FŪGAI: Poor statement.

Yen-t‘ou heard about the dialogue and said, “Tê-shan has an iron back-bone, but he spoils Zen with his soft words.”

FŪGAI: One plays the flute and the other dances.

GENRŌ: Tê-shan stole the sheep and Yen-t‘ou proved it. Such a

father! Such a son! A good combination.

GENRŌ:

Dragon head and snake tail![FŪGAI: What a monster!]

A toy stops a child’s crying.

[Valuable toy.]

Yen-t‘ou spoke as a bystander,

[A bystander can see.]

All for the allegiance to Dharma.

[Only a tithe was paid.]

80. Pa-chiao Does Not Teach

A monk asked Pa-chiao, “If there is a person who does not avoid birth and death and does not realize Nirvana, do you teach such a person?”

FŪGAI: What are you talking about?

Pa-chiao answered, “I do not teach him.”

FŪGAI: A good teacher does not waste words.

The monk said, “Why do you not teach him?”

FŪGAI: What are you talking about?

“This old monk knows good and bad,” Pa-chiao replied.

FŪGAI: The old fellow lost his tongue.

This dialogue between Pa-chiao and the monk was reported in other monasteries, and one day T‘ien-t‘ung said, “Pa-chiao may know good and bad, but he cannot take away a farmer’s ox or a hungry man’s food. If that monk asked me such a question, before he finished his sentence, I would hit him. Why? Because from the beginning I do not care about good and bad.”

FŪGAI: The pot calls the kettle black.

GENRŌ: Pa-chiao still uses the gradual method, whereas T‘ien-t‘ung employs the lightning flash. T‘ien-t‘ung’s method can be easily understood, but few will see Pa-chiao’s work clearly.

FŪGAI: What shall I say about your work?

GENRŌ:

There are many different drugs to cure an illness.[FŪGAI: Thieves in peace time!]

Arrest a person without using handcuffs.

[A hero in war time!]

Warcraft and medicine must be studied thoroughly.

[Paradise does not need such art.]

Orchid in spring, chrysanthemum in autumn.

[Excessively beautiful flowers cause congestion in the park.]

81. Kao-t‘ing Strikes a Monk

A monk came from Chia-shan and bowed to Kao-t‘ing.

FŪGAI: What are you doing!

Kao-t‘ing immediately struck the monk.

FŪGAI: The kōan is vivid here.

The monk said, “I came especially to you and paid homage with a bow. Why do you strike me?”

FŪGAI: What are you saying? Why do you not bow again?

Kao-t‘ing struck the monk again and drove him from the monastery.

FŪGAI: Pure gold has a golden sheen.

The monk returned to Chia-shan, his teacher, and related the incident.

FŪGAI: It is a good thing you have someone to talk with.

“Do you understand or not?” asked Chia-shan.

FŪGAI: What can you do with a dead snake?

“No, I do not understand it,” answered the monk.

FŪGAI: Good words, but not from you.

“Fortunately, you do not understand,” Chia-shan continued. “If you did, I would be dumbfounded.”

FŪGAI: Good contrast to Kao-t‘ing’s action.

GENRŌ:

The monk bows and Kao-t‘ing strikes;[FŪGAI: What would you do if the monk had not

bowed and you had not struck?]New etiquette for the monastery.

[Independent of convention.]

Not only is Chia-shan’s mouth closed,

[Double indemnity.]

The wheel of Dharma is smashed.

[Expresses gratitude.]

82. Yen-t‘ou's Ax

Tê-shan, Yen-t‘ou’s teacher, once told him, “I have two monks in this monastery who have been with me for many years. Go and examine them.”

FŪGAI: Why do you not go yourself?

Yen-t‘ou carried an ax to the little hut where the two monks were meditating.

FŪGAI: Have you wiped your eyes well?

Yen-t‘ou raised the ax, saying, “If you say a word of Zen, I will cut off your heads. If you do not say anything, I will also decapitate you.”

FŪGAI: Waves without wind.

The two monks continued their meditation, completely ignoring Yen-t‘ou.

FŪGAI: Stone Buddhas.

Yen-t‘ou threw down the ax, saying, “You are true Zen students.”

FŪGAI: He is buying and selling himself.

He then returned to Tê-shan and related the incident.

FŪGAI: A defeated general had better not discuss warfare.

“I see your side well,” Tê-shan agreed, “but, tell me, how is the other side?”

FŪGAI: Who are the others?

“Tung-shan may admit them,” replied Yen-t‘ou, “but they should not be admitted under Tê-shan.”

FŪGAI: Should one go to the country of mosquitoes because he dislikes the country of fleas?

GENRŌ: Why did Yen-t‘ou say the two monks should be in Tungshan’s

school but were not suitable for Tê-shan’s? Real

readers of the Tetteki Tōsui should meditate on this answer.FŪGAI: Why did Genrō make this remark that readers should

meditate?GENRŌ:

Two iron bars barricade the entrance,[FŪGAI: How can you open them?]

One arrow passes between them.

[That arrow is not strong enough.]

It is not necessary to discuss Tê-shan’s method;

[Very hard to glimpse it.]

After all, Tê-shan surrendered.

[Sometimes a pet dog will bite.]

83. Yang-shan Draws a Line

Kuei-shan said to his disciple, Yang-shan, “All day you and I were talking Zen . . .

FŪGAI: Both of you have tongues?

What did we accomplish after all?”

FŪGAI: Formless words.

Yang-shan drew a line in the air with his finger.

FŪGAI: Why do you take such trouble?

Kuei-shan continued, “It was a good thing you dealt with me. You might cheat anyone else.”

FŪGAI: The teacher lost the game.

GENRŌ: There are hundreds and thousands of Samadhis and

countless principles of Buddhism, but all of them are

included in Yang-shan’s line. If anyone wishes to know

something beyond those Samadhis or to sift out the best

principles, look here at what I am doing.FŪGAI: Bad imitator!

GENRŌ:

The miracles of these two monks surpass Moggallana’s.[FŪGAI: Both are hallucinations.]

All day long the sham battle rages.

[A battlefield on a pinpoint.]

What do they accomplish after all?

[No words, no thought.]

One finger pokes the hole in emptiness.

[Most awkward. When the clouds are gone, the sky is limitless.]

84. Ch‘ien-fêng's One Road

A monk asked Ch‘ien-fêng, “The one road of Nirvana leads into the ten quarters of Buddha-land. Where does it begin?” Ch‘ien-fêng raised his walking stick to draw a horizontal line in the air. “Here.”

FŪGAI: A white cloud obscures the road.

This monk later asked Yün-mên the same question.

FŪGAI: Are you lost again?

Yün-mên held up his fan and said, “This fan jumps up to the thirty- third heaven and hits the presiding deity on the nose, then comes down to the Eastern Sea and hits the holy carp. The carp becomes a dragon, which brings a flood of rain.”

FŪGAI: A chatterbox makes a storm in the blue sky.

GENRŌ: Ch‘ien-fêng’s answer provokes innocent people in vain;

Yün-mên rattles around like a dry pea in a box. If anyone

asked me this question, I would say, “ Can’t you see, you

blind fool?”FŪGAI: I would say to the monk, “ I respect you for coming such a

distance.”GENRŌ:

A hundred flowers follow the first bloom;[FŪGAI: For whom?]

They will festoon each field and garden.

[Let’s have a picnic.]

The eastern breeze blows gently everywhere;

[Don’t forget the seasonless season.]

Each branch has the perfect color of spring.

[Beautiful picture of fairyland.]

85. Hsüan-sha's Iron Boat

When Hsüan-sha was studying Zen under Hsüeh-fêng, a brother monk named Kuang said, “If you can attain something in Zen, I will make an iron boat and sail the high seas.”

FŪGAI: A logical statement.

Many years later Hsüan-sha became a Zen master, with Kuang studying under him as an attendant monk. One day Hsüan-sha said, “Have you built your iron boat?”

FŪGAI: Are you trying to sink the boat?

Kuang remained silent.

FŪGAI: The boat floats all right.

GENRŌ: If I were Kuang, I would say, “ Have you attained your Zen?”FŪGAI: Ha! Ha!

GENRŌ:

An iron boat froze on the sea.[FŪGAI: I would not like to sail that boat.]

The kōan from the past is fulfilled.

[Do not mention the past; live in the present.]

Do not say Kuang kept silent;

[What can he do?]

Uncle Hsüan-sha, have you attained?

[Ta-hui said, “ After eighteen attainments, all

attainments flourish.”]

86. Yang-shan Sits in Meditation

When Yang-shan was sitting in meditation, a monk came quietly and stood by him.

FŪGAI: Such a trick won’t work.

Yang-shan recognized the monk, so he drew a circle in the dust with the ideograph for “water” beneath it, then looked at the monk.

FŪGAI: What kind of charm is it?

The monk could not answer.

FŪGAI: A sprinter falls down.

GENRŌ: This monk committed petty larceny and could not even

escape after his deed. Yang-shan was ready at any time to

light the candle. Alas! The opportunity is gone.GENRŌ:

Letter “water” cannot quench thirst;[FŪGAI: But I see the giant billows rising.]

Nor pictured rice-cakes feed hunger.

[Here is a trayful of cakes.]

Yang-shan’s action brought no merit.

[That is true Zen.]

Why does he not give the monk the big stick?

[It will be too late. The big stick is already broken.]

87. Ch‘an-yüeh Snaps His Fingers

Ch‘an-yüeh, the monk poet, wrote a poem containing the following two verses:

When Zen students meet, they may snap their fingers at each other.

FŪGAI: Do not overlook it.

But how few know what it means.

FŪGAI: Do you know, it is the sword that cuts the tongue.

Ta-sui heard of this poem and, meeting Ch‘an-yüeh, he asked, “What is the meaning?”

FŪGAI: When the rabbit appears the hawk is off after him.

Ch‘an-yüeh did not answer.

FŪGAI: Did I not say before, he does not know!

GENRŌ: If I were Ch‘an-yüeh, I would snap my fingers at Ta-sui.FŪGAI: So far it is good, but instead, no one can understand it.

GENRŌ:

One snap of the fingers cannot be easily criticized,[FŪGAI: Cut the finger off.]

But he must not snap them until he has passed 110 castles.

[Do you want to wait for Maitreya?]

I should ask the crippled old woman who sells sandals,

[She cannot understand the feeling of other feet.]

“Why do you not walk to the capital barefoot?”

[It is difficult to wash one’s own back.]

88. Yüeh-shan's Lake

Yüeh-shan asked a newly-arrived monk, “Where have you come from?

FŪGAI: Are you enjoying the atmosphere?

The monk answered, “From the Southern Lake.”

FŪGAI: You give a glimpse of the lake view.

“Is the lake full or not?” inquired Yüeh-shan.

FŪGAI: Are you still interested in the lake?

“Not yet,” the monk replied.

FŪGAI: He glanced at the lake.

“There has been so much rain, why isn’t the lake filled?” Yüehshan asked.

FŪGAI: Yüeh-shan invited the monk to see the lake, actually.

The monk remained silent.

FŪGAI: He must have drowned.

GENRŌ: If I were the monk, I would say to Yüeh-shan, “ I will wait

until you have repaired the bottom.”FŪGAI: It was fortunate the monk remained silent.

GENRŌ:

The thread of Karma runs through all things;[FŪGAI: One can pick up anything as a kōan.]

Recognition makes it a barricade.

[If you look behind there is no barricade.]

The poor monk asked about a lake,

[Go on! Jump in and swim!]

Made an imaginary road to heaven.

[Where are you standing?]

89. Hsüeh-fêng's Wooden Ball

One day Hsüeh-fêng began a lecture to the monks gathered around the little platform by rolling down a wooden ball.

FŪGAI: A curved cucumber.

Hsüan-sha went after the ball, picked it up and replaced it on the stand.

FŪGAI: A round melon.

GENRŌ: Hsüeh-fêng began but did not end; Hsüan-sha ended but

did not begin. Both are incomplete. Now, tell me, monks,

which way is better?