ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

螢山紹瑾 Keizan Jōkin (1268–1325)

常濟大師 Jōsai Daishi: Great Master Jōsai, honorific title given Keizan by the Meiji emperor in the late 19th century. Jōsai means "eternally" (jō 常) "benefitting, "saving," or "ferrying across" (sai 濟).

傳光録

(Rōmaji:) Denkō-roku

(English:) The Record of the Transmission of the Light / Conveying Illumination

(Magyar:) A fény átadása / A világot-gyújtás hagyománya

坐禅用心記 / 坐禪用心記

(Rōmaji:) Zazen yōjinki

(English:) Advice on the Practice of Zazen

(Magyar:) Mire figyeljünk zazenben / Zazen útbaigazítás

This “Advice on the Practice of Zazen” was written by Keizan Jōkin, of the Japanese Sōtō School of Zen, who is also known by the honorific title of ‘Great Founder' (Taiso) and was the founder of Sōji-ji Temple. It discusses the purpose and significance of Zazen as well as giving concrete advice for the actual practice of Zazen, and is an indispensable work for all monks of the Sōtō School.

It deals with extremely practical matters such as the importance of moderation in eating for regulating one's physical condition, and strictly admonishes against wearing extravagant or soiled clothing and indulging in such recreational activities as singing, dancing, and music. In addition, it also goes on to make clear that Zazen as practiced in the Sōtō School does not correspond to only ‘meditation' as included in the ‘Three Disciplines' of precepts, meditation and wisdom, but embraces in fact all three of these disciplines.

Keizan Jōkin 瑩山紹瑾 (1268-1325). One of the "two ancestors" of the present Soto school. A fourth generation dharma heir of Dōgen, the founder of the Soto lineage in Japan. Keizan became a monk at Eiheiji at age 13. At age 32 he received dharma transmission from Tettsū Gikai 徹通義介 (1219-1309), an heir to Dōgen's lineage who had converted Daijō Monastery (Daijōji 大乘寺) in Kaga (modern Ishikawa Prefecture) into a Chinese style Zen monastery. Keizan later succeeded Gikai as abbot of Daijōji and turned it into a major center of Soto Zen proselytizing in the region. He also founded or rebuilt a number of other monasteries that were to become instrumental in the spread of Soto Zen all around Japan: Jōjūji 淨住寺, Yōkōji 永光寺, and Sōjiji 總持寺." The great majority of Soto clergy in Japan today trace their lineages of dharma inheritance back to Keizan (and through him to Dōgen). Keizan's most influential writings include: Admonitions for Zazen (Zazen yōjin ki 坐禪用心記), Record of the Transmission of the Light (Denkōroku 傳光録), and Keizan's Rules of Purity (Keizan shingi 瑩山清規).

Keizan's Rules of Purity (Keizan shingi 瑩山清規). T 82.423c-451c. A text, originally entitled Ritual Procedures for Tōkoku Mountain Yōkō Zen Monastery in Nō Province (Nōshū tōkokuzan yōkōzenji gyōji shidai 能州洞谷山永光禪寺行事次), written by the abbot Keizan Jōkin in 1324. Keizan seems to have compiled it as a handbook of ritual events and liturgical texts for use in the single monastery named in its title. The text contains a detailed calendar of daily, monthly, and annual observances that the monks of Yōkō Zen Monastery were to engage in, and the dedications of merit (ekō 囘向) statements of purpose (sho 疏) that they were to chant on those various occasions. It thus had the basic functions of a schedule of activities and a liturgical manual, as well as laying out a few rules and ritual procedures for monastic officers. It shared those features with the Rules of Purity for the Huanzhu Hermitage (Genjūan shingi 幻住菴清規), a manual written in 1317 by the eminent Zen master Chūhō Myōhon (C. Zhongfen Mingben 中峰明本; 1263–1323). Keizan probably modeled his text on that or some other similarly organized work imported from Yuan dynasty China. In 1678, the monk Gesshū Sōko 月舟宗胡 (1618-1696) and his disciple Manzan Dōhaku 卍山道白 (1636-1715), two monks active in the movement to reform Soto Zen by "restoring the old" (fukko 復古) modes of practice originally implemented by Dōgen and Keizan, took the set of rules written for Yōkōji and published them for the first time under the title of Reverend Keizan's Rules of Purity (Keizan oshō shingi 瑩山和尚清規). From that point on the text became a standard reference work used in many Soto Zen monasteries. In its organization and contents, Keizan's Rules of Purity is the direct predecessor of the present Standard Obsevances of the Soto Zen School (Sōtōshū gyōji kihan 曹洞宗行持規範).

Tartalom |

Contents |

坐禅用心記 Zazen Yojinki 傳光錄 Denkō-roku PDF: Tiszteletreméltó Bódaidaruma (Bódhidharma) PDF: Tiszteletreméltó Yakusan Igen (Yaoshan Weiyan) Keizan Jokin (1268-1325) versei |

坐禅用心記 Zazen yōjinki

三根坐禅説 Sankon Zazen-setsu

傳光録 Denkō-roku

十種勅問奏對集 Jushū Chokubun Sōtaishū

PDF: Keizan Study Material for the 2010 National Conference of The Soto Zen Buddhist Association

PDF: Great Master Keizan Jōkin: His Life and Legacy PDF: Keizan Jōkin and His Thought PDF: Visions of Power: Imagining Medieval Japanese Buddhism (1996, 2000) |

Denkōroku: Record of the Transmission of Illumination by the Great Ancestor, Zen Master Keizan

T. Griffith Foulk (editor) © 2017 Sōtōshū Shūmuchō

https://global.sotozen-net.or.jp/eng/library/denkoroku/index.html

The first book of this two-volume set consists largely of an annotated translation of the Record of the Transmission of Illumination (Denkōroku 傳光録) by Zen Master Keizan Jōkin 瑩山紹瑾 (1264–1325), presented together with the original Japanese text on which the English translation is based. That text is the recension of the Denkōroku published in Shūten Hensan Iinkai 宗典編纂委員会, ed., Taiso Keizan Zenji senjutsu Denkōroku 太祖瑩山禅師撰述伝光録 (Tokyo: Sōtōshū Shūmuchō 曹洞宗宗務庁, 2005). The Shūmuchō edition of the Denkōroku includes some items of Front Matter from earlier published editions, which are included in the English translations. Volume 1 also contains an Introduction that addresses such matters as the life of Keizan, the contents of the Denkōroku, the provenance of that work, and the textual history of its various recensions. In addition, Volume 1 includes a Bibliography that lists many works of modern Japanese- and English-language scholarship that are relevant to the academic study of the Denkōroku.

Keizan Zenji: The Denkōroku or The Record of the Transmission of the Light, Shasta Abbey, Mount Shasta, 1993.

The Denkoroku: or The Record of the Transmission of the Light, by Keizan Zenji, translated by Rev. Hubert Nearman, Shasta Abbey Press, 2001.

Denkoroku; The Record of the Transmission of the Light by Zen Master Keizan Jokin, Translator Reverend Hubert Nearman, OBC Shasta Abbey Press, Mount Shasta, California, 2003.

Online: http://www.shastaabbey.org/teachings-publications_denkoroku.html

The following sections are available for individual download in PDF:

Denkoroku pp.i-iii

Denkoroku pp.iv-xx

Denkoroku pp.1-98

Denkoroku pp.99-225

Denkoroku pp.226-308

Transmission of Light, Zen in the Art of Enlightenment by Zen Master Keizan, Translated and introduction by Thomas Cleary, North Point Press, San Francisco, 1990; Shambala, 2002.

Francis H. Cook, The Record of Transmitting the Light, Center Publications, 1991

Denkoroku: the record of transmission of light, translated by Kosen Nishiyama (西山廣宣 Nishiyama Kōsen, 1939-), Tokyo : Japan Publication (distributor), c1994, 266 p.

The Record of Transmitting the Light: Zen Master Keizan's Denkoroku, Translated and introduction by Francis Dojun Cook, Wisdom Publications, Boston, 2003

Denkoroku: Record of the Transmission of Luminosity, Chapter 29 : Bodhidharma

translated by Anzan Hoshin roshi and Yasuda Joshu Dainen zenji

http://wwzc.org/dharma-text/denkoroku-record-transmission-luminosity-29

Great Master Keizan Jōkin: His Life and Legacy by Rev. Berwyn Watson

http://journal.obcon.org/files/2012/02/Berwyn-Keizan.pdf

+ Two modern copies

+ Two modern copies

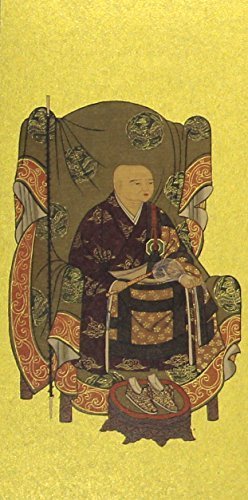

Sōjiji's founder, Keizan Jōkin.

Colored silk artwork

H89.2 x W38.6cm

Kamakura era, year Genō 1 (1319) With original sign.

Important cultural property/Treasury designated by Yokohama city

Usually, the portraits of Zen Masters are called “Chinzo”, sitting on a chair, wearing a Buddhist robe painted in an orthodox technique.

There is an original sign on the top, September 8th, year Genō 1 (1319) on the age of 52.

Historically speaking, if the date is correct, the portrait was painted when he was the abbot of Yokoji before he entered Sojiji.

There is no flaw on the drawing and it is a well-balanced artwork. The painting shows his flat forehead which is similar to the wooden statue of Yokoji and presents the features of Master Keizan.

PDF: Denkōroku

(Transmission of Light / Weitergabe des Lichts)

Cases and Verses / Fälle und Verse

(English-German Edition / englisch-deutsche Fassung)

The Sanbô-Kyôdan Society

PDF: Keizan Study Material for the 2010 National Conference of The Soto Zen Buddhist Association

http://stonecreekzencenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Keizan_Study.pdf

PDF: Keizan's Denkoroku: A Textual and Contextual Overview

by

William M. Bodiford

木造瑩山紹瑾坐像 (石川県永光寺所蔵)

木像 mokuzō; wooden effigy of Keizan

坐禅用心記 Zazen yōjinki

PDF: Instructions on How to Do Pure Meditation

Translated by Hubert Nearman

ZAZEN-YÔJINKI

Points to keep in mind when practicing zazen

Copyright © Antaiji

http://antaiji.dogen-zen.de/eng/zzyk.shtml

Zazen means to clarify the mind-ground and dwell comfortably in your actual nature. This is called revealing yourself and manifesting the original-ground.

In zazen both body and mind drop off. Zazen is far beyond the form of sitting or lying down. Free from considerations of good and evil, zazen transcends distinctions between ordinary people and sages, it goes far beyond judgements of deluded or enlightened. Zazen includes no boundary between sentient beings and buddha. Therefore put aside all affairs, and let go of all associations. Do nothing at all. The six senses produce nothing.

What is this? Its name is unknown. It cannot be called "body", it cannot be called "mind". Trying to think of it, the thought vanishes. Trying to speak of it, words die. It is like a fool, an idiot. It is as high as a mountain, deep as the ocean. Without peak or depths, its brilliance is unthinkable, it shows itself silently. Between sky and earth, only this whole body is seen.

This one is without comparison - he has completely died. Eyes clear, he stands nowhere. Where is there any dust? What can obstruct such a one?

Clear water has no back or front, space has no inside or outside. Completely clear, its own luminosity shines before form and emptiness were fabricated. Objects of mind and mind itself have no place to exist.

This has always already been so but it is still without a name. The the third patriarch, great teacher, temporarily called it "mind", and the venerable Nagarjuna once called it "body". Enlightened essence and form, giving rise to the bodies of all the Buddhas, it has no "more" or "less" about it.

This is symbolized by the full moon but it is this mind which is enlightenment itself. The luminosity of this mind shines throughout the past and brightens as the present. Nagarjuna used this subtle symbol for the samadhi of all the Buddhas but this mind is signless, non-dual, and differences between forms are only apparent.

Just mind, just body. Difference and sameness miss the point. Body arises in mind and, when the body arises, they appear to be distinguished. When one wave arises, a thousand waves follow; the moment a single mental fabrication arises, numberless things appear. So the four elements and five aggregates mesh, four limbs and five senses appear and on and on until the thirty-six body parts and the twelve-fold chain of interdependant emergence. Once fabrication arises, it develops continuity but it still only exists through the piling up of myriad dharmas.

The mind is like the ocean waters, the body like the waves. There are no waves without water and no water without waves; water and waves are not separate, motion and stillness are not different. So it is said, "A person comes and goes, lives and dies, as the imperishable body of the four elements and five aggregates."

Now, zazen is entering directly into the ocean of buddha-nature and manifesting the body of the Buddha. The pure and clear mind is actualized in the present moment; the original light shines everywhere. The water in the ocean neither increases nor decreases, and the waves never cease. Buddhas have appeared in this world for the sake of the one great matter; to show the wisdom and insight of the Buddha to all living beings and to make their entry possible. For this, there is a peaceful and pure way: zazen. This is nothing but the samadhi, in which all buddhas receive and use themselves as buddhas (jijuyu-zanmai). It is also called the king of samadhis. If you dwell in this samadhi for even a short time, the mind-ground will be directly clarified. You should know that this is the true gate of the buddha-way.

If you wish to clarify the mind-ground, you should relinquish your various types of limited knowledge and understanding. Throw away both worldly affairs and buddha-dharma. Eliminate all delusive emotions. When the true mind of the sole reality is manifest, the clouds of delusion will clear away and the moon of the mind will shine brightly.

The Buddha said, "Listening and thinking are like being outside of the gate; zazen is returning home and sitting in peace." How true this is! When we are listening and thinking, the various views have not been put to rest and the mind is still running over. Therefore other activities are like being outside of the gate. Zazen alone brings everything to rest and, flowing freely, reaches everywhere. So zazen is like returning home and sitting in peace.

The delusions of the five-obstructions all arise out of basic ignorance. Being ignorant means not clarifying youraelf. To practice zazen is to throw light on yourself. Even though the five obstructions are eliminated, if basic ignorance is not eliminated, you are not a buddha-ancestor. If you wish to eliminate basic ignorance, zazen practice of the way is the key.

An ancient master said, "When delusive thoughts cease, tranquility arises; when tranquility arises, wisdom appears; when wisdom appears, reality reveals itself." If you want to eliminate delusive thoughts, you should cease to discriminate between good and evil. Give up all affairs with which you are involved; do not occupy your mind with any concerns nor become physically engaged in any activity. This is the primary point to bear in mind. When delusive objects disappear, delusive mind falls away.

When delusive mind falls away, the unchanging reality manifests itself and we are always clearly aware. It is not extinction; it is not activity. Therefore, you should avoid engaging in any arts or crafts, medicine or fortune-telling. Needless to say, you should stay away from music and dancing, arguing and meaningless discussions, fame and personal profit. While composing poetry can be a way to purify one's mind, do not be fond of it. Give up writing and calligraphy. This is the fine precedent set by practitioners of the Way. This is essential for harmonizing the mind.

Wear neither luxurious clothing nor dirty rags. Luxurious clothing gives rise to greed and may also arouse fear of theft. Thus, they are a hindrance for a practitioner of the way. Even if someone offers them to you, it is the excellent tradition of the masters to refuse them. If you already own luxurious clothes, do not keep them. Even if these clothes are stolen, do not chase after or regret its loss. Old or dirty clothes should be washed and mended; clean them thoroughly before wearing them. If you do not clean them, they will cause you to become chilled and sick. This will be a hindrance to your practice. Although we should not be anxious about bodily life, insufficient clothing, insufficient food, and insufficient sleep are called the three insufficiencies and will cause our practice to suffer.

Do not eat anything alive, hard, or spoiled. Such impure foods will make your belly churn and cause heat and discomfort of bodymind, making your sitting difficult. Do not indulge in fine foods. It is not only bad for your body and mind, but also shows you are not yet free from greed. Eat just enough food to support your life and do not be fond of its taste. If you sit after eating too much, you will get sick. Wait for a while before sitting after eating big or small meals. Monks must be moderate in eating and hold their portions to two-thirds of what they can eat. All healthy foods, sesame, wild yams and so on, can be eaten. Essentially, you should harmonize bodymind.

When you are sitting in zazen, do not prop yourself up against a wall, meditation brace, or screen. Also, do not sit in windy places or high, exposed places as this can cause illness. Sometimes your body may feel hot or cold, rough or smooth, stiff or loose, heavy or light, or astonishingly wide-awake. Such sensations are caused by a disharmony of mind and breath. You should regulate your breathing as follows: open your mouth for a little while, letting long breaths be long and short breaths be short, and harmonize it gradually. Follow your breath for a while; when awareness comes, your breathing will be naturally harmonized. After that, breathe naturally through your nose.

Your mind may feel as though it is sinking or floating, dull or sharp, or as though you can see outside the room, inside your body, or the body of buddhas or bodhisattvas. Sometimes, you may feel as though you have wisdom and can understand the sutras or commentaries thoroughly. These unusual and strange conditions are all sicknesses that occur when the mind and breath are not in harmony. When you have this kind of sickness, settle your mind on your feet. When you feel dull, place your mind on your hairline (three inches above the center of the eyebrows) or between your eyes. When your mind is distracted, place it on the tip of your nose or on your lower abdomen, one and a half inches below the navel (tanden). Usually, place your mind on the left palm during sitting. When you sit for a long time, even though you do not try to calm your mind, it will, of its own accord, be free of distraction.

Also, although the ancient teachings are the traditional instructions for illuminating the mind, do not read, write, or listen to them too much. Running to excess scatters the mind. Generally, anything that wears out bodymind causes illness.

Do not sit where there are fires, floods, high winds, thieves; by the ocean, near bars, brothels, where widows or virgins live, or near places where courtesans play music. Do not live near kings, ministers, rich and powerful families, or people who have many desires, who seek after fame, or who like to argue meaninglessly.

Although grand Buddhist ceremonies or the building of large temples are very good things, people who devote themselves to zazen should not be involved in such activities. Do not be fond of preaching the Dharma as this leads to distraction and scattering.

Do not be delighted by large assemblies; nor covet disciples. Do not practice and study too many things. Do not sit where it is too bright or too dark, too cold or too hot; nor should you sit where idle pleasure-seekers and harlots live. Stay in a monastery where you have a good teacher and fellow practitioners. Or reside in the deep mountains or glens. A good place to practice walking meditation is where there is clear water and green mountains. A good place for purifying the mind is by a stream or under a tree. Contemplate impermanence; do not forget it. This will encourage you to seek the way.

You should spread a mat thick enough for comfortable sitting. The place for practice should be clean. Always burn incense and offer flowers to the guardians of the dharma, the buddhas and bodhisattvas, who secretly protect your practice. If you enshrine a statue of a buddha, bodhisattva, or an arhat, no demons can tempt you.

Remain always compassionate, and dedicate the limitless virtue of zazen to all living beings. Do not be arrogant; do not be proud of yourself and of your understanding of dharma. Being arrogant is the way of outsiders and ignorant people.

Vow to cut off all delusions and realize enlightenment. Just sit without doing anything. This is the essence of the practice of zazen. Always wash your eyes and feet, keep your body and mind at ease and tranquil, and maintain a proper demeanor. Throw away worldly sentiments, yet do not attach yourself to a sublime feeling of the way.

Though you should not begrudge anyone the dharma, do not preach it unless you are asked. Even if someone asks, keep silent three times; if the person still asks you from his or her heart, then teach him or her. Out of ten times you may desire to speak, remain silent for nine; as if mold were growing around your mouth. Be like a folded fan in December, or like a wind-bell hanging in the air, indifferent to the direction of the wind. This is how a person of the Way should be. Do not use the dharma to profit at the expense of others. Do not use the way as a means to make yourself important. These are the most important points to keep in mind.

Zazen is not based upon teaching, practice or realization; instead these three aspects are all contained within it. Measuring realization is based upon some notion of enlightenment - this is not the essence of zazen. Practice is based upon strenuous application - this is not the essence of zazen. Teaching is based upon freeing from evil and cultivating good - this is not the essence of zazen.

Teaching is found in Zen but it is not the usual teaching. Rather, it is a direct pointing, just expressing the way, speaking with the whole body. Such words are without sentences or clauses. Where views end and concept is exhausted, the one word pervades the ten directions without setting up so much as a single hair. This is the true teaching of the buddhas and patriarchs.

Although we speak of "practice", it is not a practice that you can do. That is to say, the body does nothing, the mouth does not recite, the mind doesn't think things over, the six senses are left to their own clarity and unaffected. So this is not the sixteen stage practice of the hearers. Nor is it the practice of understanding the twelve factors of inter-dependent emergence of those whose practice is founded upon isolation. Nor is it the six perfections within numberless activities of the bodhisattvas. It is without struggle at all so is called awakening or enlightenment. Just rest in the samadhi in which all of the buddhas receive and use themselves as buddhas (jijuyu-zanmai), wandering playfully in the four practices of peace and bliss of those open to openness. This is the profound and inconceivable practice of buddhas and patriarchs.

Although we speak of realization, this realization does not hold to itself as being "realization". This is practice of the supreme samadhi which is the knowing of unborn, unobstructed, and spontaneously arising awareness. It is the door of luminosity which opens out onto the realization of the Buddha, born through the practice of the great ease. This goes beyond the patterns of holy and profane, goes beyond confusion and wisdom. This is the realization of unsurpassed enlightenment as our own nature.

Zazen is also not based upon discipline, practice, or wisdom. These three are all contained within it.

Discipline is usually understood as ceasing wrong action and eliminating evil. In zazen the whole thing is known to be non-dual. Cast off the numberless concerns and rest free from entangling yourself in the "Buddhist way" or the "worldly way." Leave behind feelings about the path as well as your usual sentiments. When you leave behind all opposites, what can obstruct you? This is the formless discipline of the ground of mind.

Practice usually means unbroken concentration. Zazen is dropping the bodymind, leaving behind confusion and understanding. Unshakeable, without activity, it is not deluded but still like an idiot, a fool. Like a mountain, like the ocean. Without any trace of motion or stillness. This practice is no-practice because it has no object to practice and so is called great practice.

Wisdom is usually understood to be clear discernment. In zazen, all knowledge vanishes of itself. Mind and discrimination are forgotten forever. The wisdom-eye of this body has no discrimination but is clear seeing of the essence of awakening. From the beginning it is free of confusion, cuts off concept, and open and clear luminosity pervades everywhere. This wisdom is no-wisdom; because it is traceless wisdom, it is called great wisdom.

The teaching that the buddhas have presented all throughout their lifetimes are just this discipline, practice, and wisdom. In zazen there is no discipline that is not maintained, no practice that is uncultivated, no wisdom that is unrealized. Conquering the demons of confusion, attaining the way, turning the wheel of the Dharma and returning to tracelessness all arise from the power of this. Supernormal powers and inconceivable activities, emanating light and expounding the teaching- all of these are present in this zazen. Penetrating Zen is zazen.

To practice sitting, find a quiet place and lay down a thick mat. Don't let wind, smoke, rain or dew come in. Keep a clear space with enough room for your knees. Although in ancient times there were those who sat on diamond seats or on large stones for their cushions. The place where you sit should not be too bright in the daytime or too dark at night; it should be warm in winter and cool in summer. That's the key.

Drop mind, intellect and consciousness, leave memory, thinking, and observing alone. Don't try to fabricate Buddha. Don't be concerned with how well or how poorly you think you are doing; just understand that time is as precious as if you were putting out a fire on your head.

The Buddha sat straight, Bodhidharma faced the wall; both were whole-hearted and committed. Sekiso was like a gnarled dead tree. Nyojo warned against sleepy sitting and said, "Just-sitting is all you need. You don't need to make burning incense offerings, meditate upon the names of buddhas, repent, study the scriptures or do recitation rituals."

When you sit, wear the kesa (except in the first and last parts of the night when the daily schedule is not in effect). Don't be careless. The cushion should be about twelve inches thick and thirty-six in circumference. Don't put it under the thighs but only from mid-thigh to the base of the spine. This is how the buddhas and patriarchs have sat. You can sit in the full or half lotus postures. To sit in the full lotus, put the right foot on the left thigh and the left foot on the right thigh. Loosen your robes but keep them in order. Put your right hand on your left heel and your left hand on top of your right, thumbs together and close to the body at the level of the navel. Sit straight without leaning to left or right, front or back. Ears and shoulders, nose and navel should be aligned. Place the tongue on the palate and breathe through the nose. The mouth should be closed. The eyes should be open but not too wide nor too slight. Harmonizing the body in this way, breathe deeply with the mouth once or twice. Sitting steadily, sway the torso seven or eight times in decreasing movements. Sit straight and alert.

Now think of what is without thought. How can you think of it? Be beyond thinking. This is the essence of zazen. Shatter obstacles and become intimate with awakening awareness.

When you want to get up from stillness, put your hands on your knees, sway seven or eight times in increasing movements. Breathe out through the mouth, put your hands to the floor and get up lightly from the seat. Slowly walk, circling to right or left.

If dullness or sleepiness overcome your sitting, move to the body and open the eyes wider, or place attention above the hairline or between your eyebrows. If you are still not fresh, rub the eyes or the body. If that still doesn't wake you, stand up and walk, always clockwise. Once you've gone about a hundred steps you probably won't be sleepy any longer. The way to walk is to take a half step with each breath. Walk without walking, silent and unmoving.

If you still don't feel fresh after doing kinhin, wash your eyes and forehead with cold water. Or chant the "Three Pure Precepts of the Bodhisattvas". Do something; don't just fall asleep. You should be aware of the great matter of birth and death and the swiftness of impermanence. What are you doing sleeping when your eye of the way is still clouded? If dullness and sinking arise repeatedly you should chant, "Habituality is deeply rooted and so I am wrapped in dullness. When will dullness disperse? May the compassion of the buddhas and patriarchs lift this darkness and misery."

If the mind wanders, place attention at the tip of the nose and tanden and count the inhalations and exhalations. If that doesn't stop the scattering, bring up a phrase and keep it in awareness - for example: "What is it that comes thus?" or "When no thought arises, where is affliction? - Mount Sumeru!" or "What is the meaning of Bodhidharma's coming from the West? - The cypress in the garden." Sayings like this that you can't draw any flavour out of are suitable.

If scattering continues, sit and look to that point where the breath ends and the eyes close forever and where the child is not yet conceived, where not a single concept can be produced. When a sense of the two-fold emptiness of self and things appears, scattering will surely rest.

Arising from stillness, carry out activities without hesitation. This moment is the koan. When practice and realization are without complexity then the koan is this present moment. That which is before any trace arises, the scenery on the other side of time's destruction, the activity of all buddhas and patriarchs, is just this one thing.

You should just rest and cease. Be cooled, pass numberless years as this moment. Be cold ashes, a withered tree, an incense burner in an abandoned temple, a piece of unstained silk.

This is my earnest wish.

Notes on What to be Aware of in Zazen

Translated by Anzan Hoshin & Yasuda Joshu Dainen

Sitting is the way to clarify the ground of experiences and to rest at ease in your Actual Nature. This is called "the display of the Original Face" and "revealing the landscape of the basic ground".

Drop through this bodymind and you will be far beyond such forms as sitting or lying down. Beyond considerations of good or bad, transcend any divisions between usual people and sages, pass beyond the boundary between sentient beings and Buddha.

Putting aside all concerns, shed all attachments. Do nothing at all. Don't fabricate any things with the six senses.

Who is this? Its name is unknown; it cannot be called "body", it cannot be called "mind". Trying to think of it, the thought vanishes. Trying to speak of it, words die.

It is like a fool, an idiot. It is as high as a mountain, deep as the ocean. Without peak or depths, its brilliance is unthinkable, it shows itself silently. Between sky and earth, only this whole body is seen.

This one is without compare—he has completely died. Eyes clear, she stands nowhere. Where is there any dust? What can obstruct such a one?

Clear water has no back or front, space has no inside or outside. Completely clear, its own luminosity shines before form and emptiness were fabricated. Objects of mind and mind itself have no place to exist.

This has always already been so but it is still without a name. The great teacher, the Third Ancestor Sengcan temporarily called it "mind", and the Venerable Nagarjuna once called it "body". Enlightened essence and form, giving rise to the bodies of all the Buddhas, it has no "more" or "less" about it.

This is symbolized by the full moon but it is this mind which is enlightenment itself. The luminosity of this mind shines throughout the past and brightens as the present. Nagarjuna used this subtle symbol for the samadhi of all the Buddhas but this mind is signless, non-dual, and differences between forms are only apparent.

Just mind, just body. Difference and sameness miss the point. Body arises in mind and, when the body arises, they appear to be distinguished. When one wave arises, a thousand waves follow; the moment a single mental fabrication arises, numberless things appear. So the four elements and five aggregates mesh, four limbs and five senses appear and on and on until the thirty-six body parts and the twelve-fold chain of interdependant emergence. Once fabrication arises, it develops continuity but it still only exists through the piling up of myriad dharmas.

The mind is like the ocean waters, the body like the waves. There are no waves without water and no water without waves; water and waves are not separate, motion and stillness are not different. So it is said, "A person comes and goes, lives and dies, as the imperishable body of the four elements and five aggregates."

Zazen is going right into the Ocean of Awareness, manifesting the body of all Buddhas. The natural luminosity of mind suddenly reveals itself and the original light is everywhere. There is no increase or decrease in the ocean and the waves never turn back.

Thus Buddhas have arisen in this world for the one Great Matter of teaching people the wisdom and insight of Awakening and to give them true entry. For this there is the peaceful, pure practice of sitting. This is the complete practice of self-enjoyment of all the Buddhas. This is the sovereign of all samadhis. Entering this samadhi, the ground of mind is clarified at once. You should know that this is the true gate to the Way of the Buddhas.

If you want to clarify the mind-ground, give up your jumble of limited knowledge and interpretation, cut off thoughts of usualness and holiness, abandon all delusive feelings. When the true mind of reality manifests, the clouds of delusion dissipate and the moon of the mind shines bright.

The Buddha said, "Listening and thinking about it are like being shut out by a door. Zazen is like coming home and sitting at ease." This is true! Listening and thinking about it, views have not ceased and the mind is obstructed; this is why it's like being shut out by a door. True sitting puts all things to rest and yet penetrates everywhere. This sitting is like coming home and sitting at ease.

Being afflicted by the five obstructions arises from basic ignorance and ignorance arises from not understanding your own nature. Zazen is understanding your own nature. Even if you were to eliminate the five obstructions, if you haven't eliminated basic ignorance, you have not yet realized yourself as the Buddhas and Awakened Ancestors. If you want to release basic ignorance, the essential key is to sit and practice the Way.

An old master said, "When confusion ceases, clarity arises; when clarity arises, wisdom appears; and when wisdom appears, Reality displays itself."

If you want to cease your confusion, you must cease involvement in thoughts of good or bad. Stop getting caught up in unnecessary affairs. A mind "unoccupied" together with a body "free of activity" is the essential point to remember.

When delusive attachments end, the mind of delusion dies out. When delusion dies out, the Reality that was always the case manifests and you are always clearly aware of it. It is not a matter of extinction or of activity.

Avoid getting caught up in arts and crafts, prescribing medicines and fortune-telling. Stay away from songs and dancing, arguing and babbling, fame and gain. Composing poetry can be an aid in clarifying the mind but don't get caught up in it. The same is true for writing and calligraphy. This is the superior precedent for practitioners of the Way and is the best way to harmonize the mind.

Don't wear luxurious clothing or dirty rags. Luxurious clothing gives rise to greed and then the fear that someone will steal something. This is a hindrance to practitioners of the Way. Even if someone offers them to you, to refuse is the excellent tradition from ancient times. If you happen to have luxurious clothing, don't be concerned with it; if it's stolen don't bother to chase after it or regret its loss. Old dirty clothes should be washed and mended; clean them thoroughly before putting them on. If you don't take care of them you could get cold and sick and hinder your practice. Although we shouldn't be too anxious about bodily comforts, inadequate clothing, food and sleep are known as the "three insufficiencies" and will cause our practice to suffer.

Don't eat anything alive, hard, or spoiled. Such impure foods will make your belly churn and cause heat and discomfort of bodymind, making your sitting difficult. Don't indulge in rich foods. Not only is this bad for bodymind, it's just greed. You should eat to promote life so don't fuss about taste. Also, if you sit after eating too much you will feel ill. Whether the meal is large or small, wait a little while before sitting. Monks should be moderate in eating and hold their portions to two-thirds of what they can eat. All healthy foods, sesame, wild yams and so on, can be eaten. Essentially, you should harmonize bodymind.

When you are sitting in zazen, do not prop yourself up against a wall, meditation brace, or screen. Also, do not sit in windy places or high, exposed places as this can cause illness.

Sometimes when you are sitting you may feel hot or cold, discomfort or ease, stiff or loose, heavy or light, or sometimes startled. These sensations arise through disharmonies of mind and breath-energy. Harmonize your breath in this way: open your mouth slightly, allow long breaths to be long and short breaths to be short and it will harmonize naturally. Follow it for awhile until a sense of awareness arises and your breath will be natural. After this, continue to breathe through the nose.

The mind may feel as if it were sinking or floating, it may seem dull or sharp. Sometimes you can see outside the room, the insides of the body, the forms of Buddhas or Bodhisattvas. Sometimes you may believe that you have wisdom and now thoroughly understand all the sutras and commentaries. These extraordinary conditions are diseases that arise through disharmony of mind and breath. When this happens, sit placing the mind in the lap. When the mind sinks into dullness, raise attention above your hairline or before your eyes. When the mind scatters into distraction, place attention at the tip of the nose or at the tanden. After this rest attention in the left palm. Sit for a long time and do not struggle to calm the mind and it will naturally be free of distraction.

Although the ancient Teachings are a long-standing means to clarify the mind, do not read, write about, or listen to them obsessively because such excess only scatters the mind.

Generally, anything that wears out bodymind causes illness. Don't sit where there are fires, floods, or bandits, by the ocean, near bars, brothels, where widows or virgins live, or near where courtesans sing and play music. Don't live near kings, ministers, powerful or rich families, people with many desires, those who crave name and fame, or those who like to argue meaninglessly. Although large Buddhist ceremonials and the construction of large temples might be good things, one who is committed to practice should not get involved.

Don't be fond of preaching the Dharma as this leads to distraction and scattering. Don't be delighted by huge assemblies or run after disciples. Don't try to study and practice many different things.

Do not sit where it is too bright or too dark, too cold or too hot. Do not sit where pleasure-seekers or whores live. Go and stay in a monastery where there is a true teacher. Go deep into the mountains and valleys. Practice kinhin by clear waters and verdant mountains. Clear the mind by a stream or under a tree. Observe impermanence without fail and you will keep the mind that enters the Way.

The mat should be well-padded so that you can sit comfortably. The practice place should always be kept clean. Burn incense and offer flowers to the Dharma Protectors, the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas and your practice will be protected. Put a statue of a Buddha, Bodhisattva or arhat on the altar and demons of distraction will not overwhelm you.

Remain always in Great Compassion and dedicate the limitless power of zazen to all living beings.

Do not become arrogant, conceited, or proud of your understanding of the Teachings; that is the way of those outside of the Way and of usual people. Maintain the vow to end afflictions, the vow to realise Awakening and just sit. Do nothing at all. This is the way to study Zen.

Wash your eyes and feet, keep bodymind at ease and deportment in harmony. Shed worldly sentiments and do not become attached to sublime feelings about the Way. Though you should not begrudge the Teachings, do not speak of it unless you are asked. If someone asks, keep silent three times; if still they ask from their heart, then give the Teachings. If you wish to speak ten times, keep quiet nine; it's as if moss grew over your mouth or like a fan in winter. A wind-bell hanging in the air, indifferent to the direction of the wind—this is how people of the Way are.

Do not use the Dharma for your own profit. Do not use the Way to try to make yourself important. This is the most important point to remember.

Zazen is not based upon teaching, practice or realization; instead these three aspects are all contained within it. Measuring realization is based upon some notion of enlightenment—this is not the essence of zazen. Practice is based upon strenuous application—this is not the essence of zazen. Teaching is based upon freeing from evil and cultivating good—this is not the essence of zazen.

Teaching is found in Zen but it is not the usual teaching. Rather, it is a direct pointing, just expressing the Way, speaking with the whole body. Such words are without sentences or clauses. Where views end and concept is exhausted, the one word pervades the ten directions without setting up so much as a single hair. This is the true Teaching of the Buddhas and Awakened Ancestors.

Although we speak of "practice", it is not a practice that you can do. That is to say, the body does nothing, the mouth does not recite, the mind doesn't think things over, the six senses are left to their own clarity and unaffected. So this is not the sixteen stage practice of the hearers [the path of insight or darsanamarga into the four noble truths at four different levels]. Nor is it the practice of understanding the twelve nidanas of inter-dependent emergence of those whose practice is founded upon isolation. Nor is it the six perfections within numberless activities of the Bodhisattvas. It is without struggle at all so is called Awakening or enlightenment. Just rest in the Self-enjoyment Samadhi of all the Buddhas, wandering playfully in the four practices of peace and bliss of those open to Openness. This is the profound and inconceivable practice of Buddhas and Awakened Ancestors.

Although we speak of realization, this realization does not hold to itself as being "realization". This is practice of the supreme samadhi which is the knowing of unborn, unobstructed, and spontaneously arising Awareness. It is the door of luminosity which opens out onto the realization of Those Who Come Thus, born through the practice of the great ease. This goes beyond the patterns of holy and profane, goes beyond confusion and wisdom. This is the realization of unsurpassed enlightenment as our own nature.

Zazen is also not based upon discipline, practice, or wisdom. These three are all contained within it.

Discipline is usually understood as ceasing wrong action and eliminating evil. In zazen the whole thing is known to be non-dual. Cast off the numberless concerns and rest free from entangling yourself in the "Buddhist Way" or the "worldly way." Leave behind feelings about the path as well as your usual sentiments. When you leave behind all opposites, what can obstruct you? This is the formless discipline of the ground of mind.

Practice usually means unbroken concentration. Zazen is dropping the bodymind, leaving behind confusion and understanding. Unshakeable, without activity, it is not deluded but still like an idiot, a fool. Like a mountain, like the ocean. Without any trace of motion or stillness. This practice is no-practice because it has no object to practice and so is called great practice.

Wisdom is usually understood to be clear discernment. In zazen, all knowledge vanishes of itself. Mind and discrimination are forgotten forever. The wisdom-eye of this body has no discrimination but is clear seeing of the essence of Awakening. From the beginning it is free of confusion, cuts off concept, and open and clear luminosity pervades everywhere. This wisdom is no-wisdom; because it is traceless wisdom, it is called great wisdom.

The Teaching that the Buddhas have presented all throughout their lifetimes are just this discipline, practice, and wisdom. In zazen there is no discipline that is not maintained, no practice that is uncultivated, no wisdom that is unrealized. Conquering the demons of confusion, attaining the Way, turning the wheel of the Dharma and returning to tracelessness all arise from the power of this. Siddhis and inconceivable activities, emanating luminosity and proclaiming the Teachings—all of these are present in this zazen. Penetrating Zen is zazen.

To practice sitting, find a quiet place and lay down a thick mat. Don't let wind, smoke, rain or dew come in. Keep a clear space with enough room for your knees. Although in ancient times there were those who sat on diamond seats or on large stones for their cushions. The place where you sit should not be too bright in the daytime or too dark at night; it should be warm in winter and cool in summer. That's the key.

Drop mind, intellect and consciousness, leave memory, thinking, and observing alone. Don't try to fabricate Buddha. Don't be concerned with how well or how poorly you think you are doing; just understand that time is as precious as if you were putting out a fire in your hair.

The Buddha sat straight, Bodhidharma faced the wall; both were whole-hearted and committed. Shishuang was like a gnarled dead tree. Rujing warned against sleepy sitting and said, "Just-sitting is all you need. You don't need to make burning incense offerings, meditate upon the names of Buddhas, repent, study the scriptures or do recitation rituals."

When you sit, wear the kesa (except in the first and last parts of the night when the daily schedule is not in effect). Don't be careless. The cushion should be about twelve inches thick and thirty-six in circumference. Don't put it under the thighs but only from mid-thigh to the base of the spine. This is how the Buddhas and Ancestors have sat. You can sit in the full or half lotus postures. To sit in the full lotus, put the right foot on the left thigh and the left foot on the right thigh. Loosen your robes but keep them in order. Put your right hand on your left heel and your left hand on top of your right, thumbs together and close to the body at the level of the navel. Sit straight without leaning to left or right, front or back. Ears and shoulders, nose and navel should be aligned. Place the tongue on the palate and breathe through the nose. The mouth should be closed. The eyes should be open but not too wide nor too slight. Harmonizing the body in this way, breathe deeply with the mouth once or twice. Sitting steadily, sway the torso seven or eight times in decreasing movements. Sit straight and alert.

Now think of what is without thought. How can you think of it? Be Before Thinking. This is the essence of zazen. Shatter obstacles and become intimate with Awakening Awareness.

When you want to get up from stillness, put your hands on your knees, sway seven or eight times in increasing movements. Breathe out through the mouth, put your hands to the floor and get up lightly from the seat. Slowly walk, circling to right or left.

If dullness or sleepiness overcome your sitting, move to the body and open the eyes wider, or place attention above the hairline or between your eyebrows. If you are still not fresh, rub the eyes or the body. If that still doesn't wake you, stand up and walk, always clockwise. Once you've gone about a hundred steps you probably won't be sleepy any longer. The way to walk is to take a half step with each breath. Walk without walking, silent and unmoving.

If you still don't feel fresh after doing kinhin, wash your eyes and forehead with cold water. Or chant the Three Pure Precepts of the Bodhisattvas. Do something; don't just fall asleep. You should be aware of the Great Matter of birth and death and the swiftness of impermanence. What are you doing sleeping when your eye of the Way is still clouded? If dullness and sinking arise repeatedly you should chant, "Habituality is deeply rooted and so I am wrapped in dullness. When will dullness disperse? May the compassion of the Buddhas and Ancestors lift this darkness and misery."

If the mind wanders, place attention at the tip of the nose and tanden and count the inhalations and exhalations. If that doesn't stop the scattering, bring up a phrase and keep it in awareness - for example: "What is it that comes thus?" or "When no thought arises, where is affliction? - Mount Meru!" or "What is the meaning of Bodhidharma's coming from the West? - The cypress in the garden." Sayings like this that you can't draw any flavour out of are suitable.

If scattering continues, sit and look to that point where the breath ends and the eyes close forever and where the child is not yet conceived, where not a single concept can be produced. When a sense of the two-fold emptiness of self and things appears, scattering will surely rest.

Arising from stillness, carry out activities without hesitation. This moment is the koan. When practice and realization are without complexity then the koan is this present moment. That which is before any trace arises, the scenery on the other side of time's destruction, the activity of all Buddhas and Awakened Ancestors, is just this one thing.

You should just rest and cease. Be cooled, pass numberless years as this moment. Be cold ashes, a withered tree, an incense burner in an abandoned temple, a piece of unstained silk.

This is my earnest wish.

Zazenyojinki

Points to Watch in Zazen

by Keizan Jokin

Translated by Reiho Masunaga

Chapter 8 (from the book: Soto Approach to Zen)

![]() Introduction

Introduction

Keizan, the founder of Sojiji wrote this manuscript, while he was staying at Yokoji, a temple in Ishikawa prefecture. Dogen, in Fukanzazengi gave the basic rules for zazen, but Keizan made these rules more explicit. In Zazenyojinki he goes into such details as choosing a sitting place, precautions against weather, harmony of breathing, and ways to calm the mind. Zazenyojinki even covers sitting posture, eating habits, proper clothing, inhaling and exhaling, psychological condition, and sitting rules. It thus gives the trainee a detailed set of precautions for nearly all-foreseeable problems.

Together with Fukanzazengi this work provides a base for Soto Zen practice. The trainee will find here all he needs to avoid the major pitfalls of zazen.

Manzan (Dohaku (1636-1715) published Zazenyojinki in 1680 and wrote an introduction for it. Since then the work has prompted a number of commentaries - the most famous being one by Shigetsu Ein (died 1764) called Zazenyojinki Funogo.

Text (Zazenyojinki)

Zazen clears up the human-being mind immediately and lets him dwell in his true essence. This is called showing one's natural face and expressing one's real self. It is freedom from body and mind and release from sitting and lying down.

So think neither of good nor on evil. Zazen transcends both the unenlightened and the sage, rises above the dualism of delusion and enlightenment, and crosses over the division of beings and Buddha. Through zazen we break free from all things, forsake myriad relations, do nothing, and stop the working of the six sense organs.

Who does this? We still do not know his name. We should call it neither body nor mind. If we try to imagine it, it defies imagination. If we try to describe it, it defies description. It is like the fool - and also the sage. It is high as the mountain and deep as the sea - impossible to see the top or bottom. It shines without an object, and the eyes of wisdom penetrate beyond the Body; the Body expressed itself and forms emerge. The ripple of one wave touches off 10,000 waves. The slight twitch of consciousness brings the 10,000 things bubbling up. The so-called four elements and five aggregates combine, and the four limbs and five organs immediately take form. In addition the 36 bodily possessions and the 12 mutual causes arise and circulate in successive currents. They interpenetrate with myriad things.

Our mind is like the ocean water, our body, like the waves. Just as there is not a single wave outside the ocean waters, not a drop of water exists outside waves. The water and waves are not different; action and inaction do not differ. So it is said: "Even though living and dying, going and coming, they are true men. Even though possessing the four elements and five aggregates, they have the eternal body." This zazen directly enters the ocean of the Buddha Mind and immediately manifests the Buddha Body. Then the Mind -inherently unexcelled, clear, and bright-suddenly emerges, and the supreme light shines fully at last. The ocean waters know no increase or decrease, and neither do the waves undergo change. All Buddhas appear in this world to solve its cloud. It reaches without thinking and radiates the essential teaching in silence. Sitting in both heaven and earth, we express our whole body in freedom. The great man who has sloughed off thinking is like one who has died the Great Death. No illusions distort his sight; his feet pick up no dust. No dust anywhere and nothing obstructs him.

Pure water has neither front nor back. In a clear sky there is essentially no inside and out side. Like them - transparent and clear - zazen shines brightly by itself. Form and void are undivided nor are objects and wisdom apart. They have been together from time eternal and have no name. The Third Patriarch, a great teacher, tentatively called it "Mind"; the respected Nagarjuna called it "Body." It expresses the form of the Buddha and the body of the Buddhas. This full-moon form has neither lack nor excess. Anyone self-identified with this mind is a Buddha. The light of this self, shining both now and in the past, gains shape and fulfills the samadhi of the Buddhas.

The Mind essentially is not two; the Body takes various shapes through causality. Mind-only and Body-only cannot be explained either as different or the same. The Mind changes and becomes the most crucial problems by giving all beings direct access to the Buddha's wisdom. They teach a wonderful way of calmness and detachment zazen. It is, in fact, the self-joyous meditation of the Buddhas. It is the king of meditations. Dwelling in this meditation even for a moment will clear away your delusions. This, we know, is the right gate to Buddhism.

Those who would clear up their mind must abandon complex intellection, forsake the world and Buddhism, and make the Buddha Mind appear. Then the cloud of delusion lifts and the moon of the mind shines anew.

The Buddha is supposed to have said that hearing and thinking about Buddhism is like standing outside the gate but that zazen is truly returning home and sitting down in comfort. This is true. In hearing and thinking of Buddhism, opinions prevail. The mind remains confused; it is truly like standing outside the gate. But in this zazen all things disappear; it is not conditioned by place. It is like returning home and sitting down in comfort.

The delusion of the five hindrances arises from ignorance. Ignorance stems from not knowing the self - the self, that zazen enables us to know. Even if we cut off the five hindrances, we still remain outside the sphere of the Buddhas and patriarchs unless we also free ourselves from ignorance. And the most effective way to do this is zazen. An ancient sage has said: "When delusions disappear, calmness emerges, When calmness emerges, wisdom arises. When wisdom, arises, there is true understanding.

To get rid of delusive thoughts we have to stop thinking about good and evil. We have to sever all relations, throw everything away, think of nothing, and do nothing with our body. This is the primary precaution. When delusive relations disappear, delusive thoughts disappear. When delusive thoughts disappear, there emerges the reality that gives us clear insight into all things. It is not passivity, nor is it activity.

Free yourself from all such trifles as art, technique, medicine, and fortune telling. Stay away from singing, dancing, music, noisy chatter, gossip, publicity, and Profit-seeking. Although composing verse and poetry may help quiet your mind; don't become too intrigued by them. Also abandon writing and calligraphy.

This advice represents a supreme legacy from the seekers of the way in the past. It outlines the prerequisites for bringing your mind into harmony.

Also avoid both beautiful robes, and stained clothing. A beautiful robe gives rise to desire, and there is also the danger of theft. It, there fore, hinders the truth-seeker. If someone hap pens to offer you a rich robe, turn it down. This has been the worthy tradition from long ago. If you have such a robe from before, discount its importance. And if someone steals it, don't brood over your loss.

Wear old clothes but mend any holes and wash off any stain or oil. If you don't clean off the dirt, your chances of getting sick increase, and this would obstruct training.

Lack of clothing, lack of food, and lack of sleep - these are the three lacks. They become a source of idleness. In eating, avoid anything unripe, indigestible, rotten, or unsanitary. Such food will make your stomach rumble and impair your body and mind. You will merely increase your discomfort in zazen. And don't fill up with delicacies. Such gorging not only will decrease your alertness, but also will show everyone that you still have not freed yourself from avarice. Food exists only to support life; don't cling to its taste. If you do zazen with a full stomach you create the cause of sickness. Avoid zazen immediately after breakfast or lunch; it is better to wait awhile.

Generally, monks watch the amount of food they eat. Watching their food intake means limiting the amount: eat two thirds and leave one third. In preparing for zazen, take cold Preventing medicine, sesame seed and mountain potatoes, In actually doing zazen, don't lean against walls, backs of chairs, or screens. Stay away from high places with strong winds even if the view is good. This is a fine way to get sick.

If your body is feverish or cold, dull or active hard or soft, or heavy or light, you probably aren't breathing correctly. Check your breathing, too, if your body feels overly irritable. You must make sure that you are breathing harmoniously at all times during zazen.

To harmonize breathing, use this method: open your mouth for awhile and if a long breath comes, breathe long; if a short breath comes, breathe short. Gradually harmonize your breathing and follow it naturally. When the timing becomes easy and natural, quietly shift your breathing to your nose. When breathing and mind are not coordinated, certain symptoms arise. Your mind sinks or rises, becomes vague or sharp, wanders outside the room or within the body; sees the image of the Buddha or Bodhisattvas, gives birth to corrupting thoughts, or seeks to understand the doctrines of the sutras. When you have these symptoms, it means your mind and breathing are not in harmony. If you have this trouble, shift your mind to the soles of both feet. If the mind sinks, put it on the hairline and between the eyebrows. If your mind is disturbed, rest it on the tip of the nose or on the solar plexus. In ordinary zazen, put your mind in your left palm. In prolonged sitting, even without this the mind naturally remains undisturbed. The old teaching emphasized illumination of mind, but doesn't pay too much attention to this.

Any excesses lead to a disturbed mind. Anything that puts a strain on body and mind becomes a source of illness. So don't practice zazen where there is danger of fire, flood strong winds, and robbery. Keep away from areas near the seashore, bars, and red light districts, homes of widows and young virgins, and theaters. Avoid living near kings, ministers, and high authority or near gossips and seekers after fame and profit.

Temple rituals and buildings have their worth. But if you are concentrating on zazen, avoid them. Don't get attached to sermons and instructions because they will tend to scatter and disturb your mind. Don't take pleasure in attracting crowds or gathering disciples. Shun a variety of practices and studies. Don't do zazen where it is too light or too dark, too cold or too hot, or too near pleasure-seekers and entertainers. You should practice inside the meditation hall, go to Zen masters, or take yourself to high mountains and deep valleys. Green waters and Blue Mountains - these are good places to wander. Near streams and under trees - these places calm the mind. Remember that all things are unstable. In this you member that all things are unstable. In this you may find some encouragement in your search for the way.

The mat should be spread thickly: zazen is the comfortable way. The meditation hall should be clean. If incense is always burned and flowers offered the gods protecting Buddhism and the Bodhisattvas cast their shadows and stand guard. If you put the images of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas and Arhats there, all the devils and witches are powerless.

Dwelling always in great compassion, you should offer the limitless merits of zazen to all beings. Don't let pride, egotism, and arrogance arise; they are possessions of the heretical and unenlightened. Vow to cut off desire; vow to obtain enlightenment. Just do zazen and nothing else. This is the basic requirement for zazen.

Before doing zazen, always wash your eyes and feet, and tranquilize your body and mind. Move around easily. Throw away worldly feelings, including the desire for Buddhism. Although you should not begrudge the teaching, don't preach it unless you are asked. After three requests, give the four effects (indicate, instruct, benefit, rejoice). When you feel like talking, keep quiet nine out of 10 times-like mold growing around the mouth and a fan used in December or like a bell hanging in the sky that rings naturally without reliance on the four directions of the wind.

For the trainee this is the main point to watch: possessing the teaching but not selling it cheap. Attaining enlightenment but not taking pride in it. This zazen does not attach itself one-sidedly to doctrine, training, or enlightenment. It combines all these virtues. Enlightenment ordinarily means Satori, but this is not the spirit of zazen. Training ordinarily means actual practice, but this is not the spirit of zazen. Doctrine ordinarily means stopping evil and doing good, but this is not the spirit of zazen.

Although Zen has doctrines, they differ from those of Buddhism in general. The method of direct pointing and true transmission is expressed by the whole body in zazen. In this expression, there are no clauses and sentences. Here, where mind and logic cannot reach, zazen expresses the 10 directions. And this is done without using a single word. Isn't this the true doctrine of the Buddhas and patriarchs?

Although Zen talks about training, it is the training of no-action. The body does nothing except zazen. The mouth does not utter the Dharani, the mind does not work at conceptual thinking; the six sense organs are naturally pure and have no defilement. This is not the 16 views (toward the Four Noble Truths) of the Sravaka, or the 12 causal relations of the Pratyekabuddha, or the six paramitas and other training of the Bodhisattvas. Nothing is done except zazen, and this zazen is called the Buddha's conduct. The trainee just dwells comfortably in the self-joyous meditation of the Buddhas and freely performs the four comfortable actions of the Bodhisattvas. This then is the deep and marvelous training of the Buddhas and patriarchs.

And although we talk about enlightenment, we become enlightened without enlightenment. This is the king of samadhi. This is the samadhi that gives rise to the eternal wisdom of the Buddha. It is the samadhi from which all wisdom arises. It is the samadhi that gives rise to natural wisdom. It is the clear gate that opens into the compassion of the Tathagata. It is the place that gives rise to the teaching of the great comfortable conduct (zazen) - It transcends the distinction between sage and commoner; it is beyond dualistic judgment that separates delusion and enlightenment. Isn't this the enlightenment that expresses one's original face?

Though zazen does not cling to virtue, meditation, and wisdom, it includes them. So-called virtue protects one from wrong and stops evil. But in zazen we see the total body without two-ness. We abandon all things and stop varied relations; we do not cling to Buddhism and worldly affairs; we prized religious sentiment and worldly thoughts. There is neither right and wrong nor good and evil. What is there to suppress and to stop? This is the formless virtue of Buddha nature. Usually zazen means concentrating the mind and eliminating extraneous thoughts. But in this zazen, we free ourselves from dualism of body and mind and of delusion and enlightenment. Neither the body nor mind changes, moves, acts, or worries.

Like a rock, like a stake, like a mountain, like an ocean, the two forms of movement and rest do not arise. This is meditation without the form of meditation. Because there is no form of meditation, it is called just meditation. But in this zazen we naturally destroy the obstacle of knowledge (ignorance), forget the delusive activity of the mind; our entire body becomes the eye of wisdom; there is no discrimination and recognition. We clearly see the Buddha nature and are inherently not deluded. We cut the delusive root of the mind and the light of the Buddha mind shines through suddenly.

This is wisdom without the form of wisdom. Because it is wisdom without form, it is called Great Wisdom. The teachings of the Buddha and the sermons of Sakyamuni (in his life) are all included in virtue, meditation, and wisdom. In this zazen we hold all virtue, train all meditation, and penetrate into wisdom. Suppression of demons, enlightenment, serand death all depend on this power. Superior work and illuminating sermon are all in the zazen. Interviewing the Zen master is also zazen.

If you want to do zazen, you must first find a quiet place. You should sit on a thick cushion. You should allow no smoke or wind to enter. You should keel away from rain and dew. Take care of the sitting place and keep it clean. The Buddha sat on a diamond seat, and the patriarchs sat on huge rocks, but in each case they used cushions. The sitting place should neither be too light during the day nor too dark during the night. It should be warm in winter and cool in summer. These are precautions regarding the place abandon the functioning of the mind; stop dualistic thinking, and do not plan to become a Buddha. Don't think about right and wrong. Do not waste time make efforts as though saving your burning head.

The Buddha sitting under the Bodhi tree and Bodhidharma wall gazing concentrated only on zazen and did nothing else. Sekiso (Shih-shuang Ch'ing-chu) (807-888) sat like a withered tree. Nyojo (Ju-tsing) (1163-1228) warned against taking a nap while doing zazen. Nyojo always said that you can obtain your goal for the first time by merely sitting - without burning incense, giving salutation, saying the Nembutsu, practicing austerity, chanting the sutra, or performing various duties. Generally when doing zazen you should wear a kesa; you must not leave this out. You should not sit completely on the cushion; it should be put halfway back under the spine. This is the sitting method of the Buddhas and the patriarchs. Some meditate in paryanka and others in half-paryanka. In paryanka you must put your right thigh. Wearing your robe loosely adjust your posture.

Next rest your right hand on your left foot and your left hand on your right palm. Touching your thumbs together, bring your hands close to your body. Put them close to your navel. Sit upright and do not lean either to the left or right. Neither should you lean forward nor backward. Place your navel. Keep your tongue against the palate, and breathe through your nose. Keep your lips and teeth firmly closed. You should keep your eyes open. Neither open them too wide nor narrow them too much. After you have seated your self comfortably, inhale sharply. To do this you open your mouth and breathe out once or twice.

After sitting you should move your body seven or eight times from the left to right, going from large motions to small. Then you should sit like an immovable mountain. In this position try to think the unthinkable How do you think the unthinkable? By going beyond both thinking and unthinking. This is the key to zazen. You should cut off your delusions immediately and enlighten the way suddenly.

When you want to get up from zazen, put your hands on your thighs with palms up and move your body seven or eight times from left to right with the motions getting progressively larger. Then open your mouth and inhale; put your hands on the floor; gently arise - from the cushion; and quietly walk around. Turn your body to the right and walk to the right. If you feel sleepy during zazen, you should move -your body and open your eyes widely. Concentrate your mind on the top of your head, edge of your hair, or between your eyebrows. If this doesn't make you - wide awake, stretch out your hand and rub your eyes, or massage your body. If even this does not awaken you, get up from your seat and walk around lightly. You should walk around to the right. If you walk in the way for about 100 steps, your sleepiness should go away. The method of walking is to take a breath every short step (about half of the average step); like moving without moving, it should be done quietly. If even all this does not awaken you, wash your eyes and cool your head. Or read the introduction of the precepts of the Bodhisattva. By these various means you should avoid sleep.

The most important thing is to transcend the problem of birth and death. Though this life moves swiftly, the eye for seeing the way is not open. We must realize that this is no time to sleep. If you are about to be lulled to sleep, you should make this vow: "My habitual passion from former actions is already deep-rooted; therefore I have already received the hindrance of sleep. When will I awake from the darkness? Buddhas and the patriarchs I seek escape from the suffering of my darkness through your great compassion.

If your mind is disturbed, rest it on the tip of the nose or below the navel and count your inhaled and exhaled breath. If your mind still is not calm, take a Koan and concentrate on it. For example consider these non-taste the stories: "Who is this that comes before me?" (Hui-neng); "Does a dog have Buddha nature?" (Chao-chou); Yun men's Mt Sumeru and Chao-chou's oak tree in the garden. These are available applications. If your mind is still disturbed, sit and concentrate on the moment your breath has stopped and both eyes have closed forever, or on the unborn state in your mother's womb or before one thought arises. If you do this, the two Sunyatas (non-ego) will emerge, and the disturbed mind will be put at rests.

When you arise from meditation and unconsciously take action, that action is itself a Koan. Without entering into relation, when you accomplish practice and enlightenment, the Koan manifests itself. State before the creation of heaven and earth, condition of empty kalpa, and wondrous functions and most important thing of Buddhas and patriarchs - all these are one thing, zazen.

We must quit thinking dualistically and put a stop to our delusive mind, cool our passions, transcend moment and eternity, make our mind like cold ashes and withered trees, unify meditation and wisdom like a censer in an old shrine, and purify body and mind like a single white strand. I sincerely hope that you will do all this.

Modern portrait of Keizan

KEIZAN JOKIN'S ZAZEN YOJINKI

What to be aware of in zazen, sitting meditation

Translated by Thomas Cleary

Timeless Spring : A Soto Zen anthology. Weatherhill, Tokyo-New York, 1980, pp. 112-125.

Zazen just lets people illumine the mind and rest easy in

their fundamental endowment. This is called showing the

original face and revealing the scenery of the basic ground.

Mind and body drop off, detached whether sitting or lying

down. Therefore we do not think of good or bad, and can

transcend the ordinary and the holy, pass beyond all conception

of illusion and enlightenment, leave the bounds of

sentient beings and buddhas entirely.

So, putting a stop to all concerns, casting off all attachments,

not doing anything at all, the six senses inactive -

who is this, whose name has never been known, cannot

be considered body, cannot be considered mind? When

you try to think of it, thought vanishes; when you try to

speak of it, words come to an end. Like an idiot, like an

ignoramus, high as a mountain, deep as an ocean, not

showing the peak or the invisible depths - shining without

thinking, the source is clear in silent explanation.

Occupying sky and earth, one's whole body alone is

manifest; a person of immeasurable greatness - like one

who has died utterly, whose eyes are not clouded by any-

thing, whose feet are not supported by anything - where

is there any dust? What is a barrier? The clear water never

had front or back, space will never have inside or out.

Crystal clear and naturally radiant before form and void

are separated, how can object and knowledge exist?

This has always been with us, but it has never had a

name. The third patriarch, a great teacher, temporarily

called it mind; the venerable Nagarjuna provisionally

called it body[1] - seeing the essence and form of the enlightened,

manifesting the bodies of all buddhas, this,

symbolized by the full moon, has neither lack nor excess.

It is this mind which is enlightened itself; the light of

one's own mind flashes through the past and shines

through the present. Mastering Nagarjuna's magic symbol,

achieving the concentration of all buddhas, the mind has

no sign of duality, while bodies yet differ in appearance.

Only mind, only body - their difference and sameness are

not the issue; mind changes into body, and when the body

appears they are distinguished. As soon as one wave

moves, ten thousand waves come following; the moment

mental discrimination arises, myriad things burst forth.

That is to say that the four main elements and five clusters

eventually combine, the four limbs and five senses suddenly

appear, and so on down to the thirty six parts of the

body, the twelve fold causal nexus; fabrication flows along,

developing continuity - it only exists because of the combining

of many elements.

Therefore the mind is like the ocean water, the body is

like the waves. As there are no waves without water and

no water without waves, water and waves are not separate,

motion and stillness are not different. Therefore it is

said, "The real person coming and going living and dying

- the imperishable body of the four elements and five

clusters:" [2]

Now zazen is going right into the ocean of enlightenment,

thus manifesting the body of all buddhas. The in-

nate inconceivably clear mind is suddenly revealed and the

original light finally shines everywhere. There is no increase

or decrease in the ocean, and the waves never turn

back. Therefore the enlightened ones have appeared in the

world for the one great purpose of having people realize

the knowledge and vision of enlightenment. And they had

a peaceful, impeccable subtle art, called zazen, which is

the state of absorption that is king of all states of concentration.

If you once rest in this absorption, then you directly

illumine the mind - so we realize it is the main

gate to the way of enlightenment.

Those who wish to illumine the mind should give up

various mixed-up knowledge and interpretation, cast away

both conventional and buddhist principles, cut off all delusive

sentiments, and manifest the one truly real mind -

the clouds of illusion clear up, the mind moon shines

anew. The Buddha said, "Learning and thinking are like

being outside the door; sitting in meditation is returning

home to sit in peace." How true this is! While learning

and thinking, views have not stopped and the mind is still

stuck - that is why it is like being outside the door. But

in this sitting meditation, zazen, everything is at rest and

you penetrate everywhere - thus it is like returning home

to sit in peace.

The afflictions of the five obscurations[3] all come from

ignorance, and ignorance means not understanding yourself.

Zazen is understanding yourself. Even though you

have eliminated the five obscurations, if you have not

eliminated ignorance, you are not a buddha or an ancestor.

If you want to eliminate ignorance, zazen to discern the

path is the most essential secret.

An ancient said, "When confusion ceases, tranquility

comes; when tranquility comes, wisdom appears, and

when wisdom appears reality is seen." If you want to put

an end to your illusion you must stop thinking of good

and bad and must give up all involvement in activity; the