ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjōra

丹霞天然 Danxia Tianran (739-824)

(Rōmaji:) Tanka Tennen

Tartalom |

Contents |

Tan-hszia Tien-zsan Tan-hszia Tien-zsan mondásaiból |

Danxia burning Buddha statue Tianran Roasting the Buddha The Blue Cliff Record, 76th Case Ch'an Poems Burning the Wooden Buddha Denkōroku, Chapter 47 & 48 Danxia Tianran Ch. 3. Danxia Burns a Buddha: Zen and the Art of Iconoclasm |

![]()

One of Ma-tsu's famous disciples, T'ien-jan 天然 (died 824) of Tanhsia 丹霞 (Tanka in Japanese), was spending a night at a ruined temple with a few traveling companions. The night was bitterly cold and there was no firewood. He went to the Hall of Worship, took down the wooden image of the Buddha, and made a comfortable fire. When he was reproached by his comrades for this act of sacrilege, he said: "I was only looking for the `sariira (sacred relic) of the Buddha." "How can you expect to find `sariira in a piece of wood?" said his fellow travelers. "Well," said T'ien-jan, "then, I am only burning a piece of wood after all."

Hu Shih, Philosophy East and West, Vol.. 3, No. 1 (January, 1953), pp. 3-24

Tan-hsia Tʾien-jan (Jap., Tanka Tennen; 739–834). Chinese Chʾan/Zen master, dharma-successor (has-su) of Shih-tʾou Hsi-chien, and the master of Ts'ui-wei Wu-hsueh (Jap., Suibi Mugaku).

As Master Yuan-wu reports in his commentary on example 76 of the Pi-yen-lu, Tan-hsia, whose birthplace and family are unknown, studied the Confucian classics and planned to take the civil service examination in the capital, Ch'ang-an. On the way there he met a Ch'an monk, who asked him what his goal was. “I've decided to become a functionary, said Tan-hsia. “What does the decision to become a functionary amount to compared with the decision to become a buddha?” replied the monk. “Where can I go if I want to become a buddha?” Tan-hsia then asked. The monk suggested that he seek out the great Ch'an master Ma-tsu Tao-i (Jap., Baso Doitsu), whereupon Tan-hsia unhesitatingly set out to do so. Ma-tsu soon sent him on to Shih-t'ou, under whom he trained for some years. He went on to become one of Shih-t'ou's dharma successors.

Later he returned to Ma-tsu. Having arrived in Ma-tsu's monastery he sat himself astride the neck of a statue of Manjushri. As the monks, upset by the outrageous behavior of the newcomer, reported this to Ma-tsu, the latter came to see Tan-hsia and greeted him with the words, “You are very natural, my son.” From this incident Tan-hsia's monastic name T'ien-jan (the Natural) is derived. After the death of Ma-tsu, Tan-hsia went on wandering pilgrimage and visited other great Ch'an masters of the time in order to train himself further in hossen with them. At the age of eighty-one, he settled in a hermitage on Mount Tan-hsia, from which his name is derived. Soon up to 300 students gathered there around him and built a monastery. Four years after his arrival on Mount Tan-hsia, he suddenly said one day, “I'm going on a journey once again.” He picked up his hat and his pilgrim's robe and staff. When he had put on the second of his pilgrim's sandals, he passed away before his foot again touched the ground.

There are many stories about Tan-hsia, who was a close friend of the Ch'an layman P'ang-yun, telling of his unconventional behavior. The most famous of these stories tells that once during his wandering years he spent the night in a Ch'an temple. The night being cold, he took a buddha image off the shrine, made a fire with it, and warmed himself. When the temple priest took him to task for having violated a sacred statue, Tan-hsia said, “I'll get the bones of the Buddha [for relics] out of the ashes.” “How can you expect to find Buddha's bones in wood?” asked the priest. Tan-hsia replied, “Why are you berating me then for burning the wood?!”

http://www.ese-an.org/

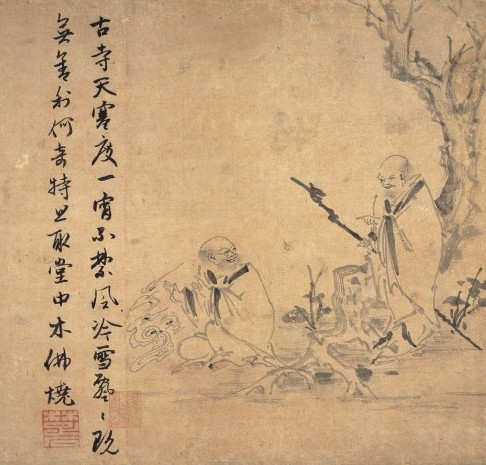

丹霞焼仏図

Danxia Tianran (739-824) burning Buddha statue

by 因陀羅 Yintuoluo (Indara)

![[转载]å¤ä½å¾è°±ï¼ä¹ä¸ï¼](danxia1.jpg)

Sketch by 黃澤 Huangze (1924)

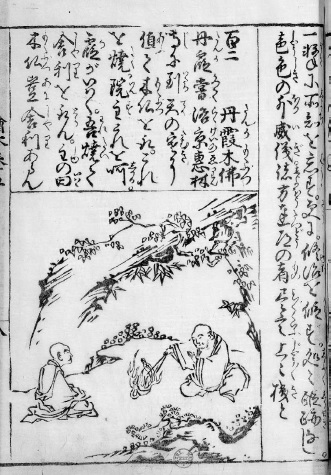

Illustration by

王振羽 Wang Zhenyu

(1968-)

“Danxia and the Wood Buddha,”

in Japanese-Chinese Expanded Precious Mirror of Painting

(Wakan zōho Ehon hōkan; 1688). Bibliotheque nationale de France

“The Monk from Danxia Burning a Wooden Image of the Buddha”

by 雲谷等顔 Unkoku Tōgan (1547–1618)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

丹霞焼仏 Tanka sho butsu

Danxia Tianran (739-824) burning Buddha statue

長沢蘆雪 Nagasawa Rosetsu (1754–1799)

late 1780s

Hanging scroll, ink and light color on paper

114.8 x 27.5 cm

丹霞燒佛圖 by 葛飾北斎 Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849)

59 x 36.6 cm

Freer Gallery of Art

https://m.blog.naver.com/huiripuzhao/221018183126

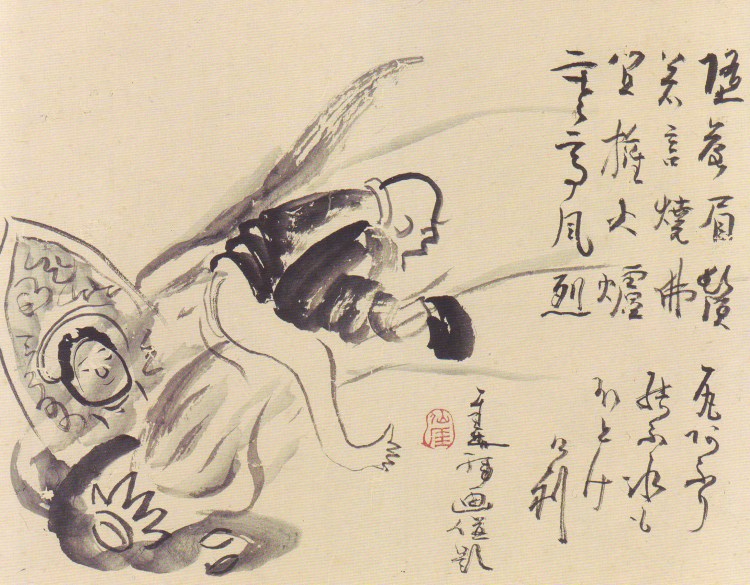

by Sengai Gibbon (1750-1837) |

|

Notes:

Having one's beard fall off was a kind of spirtual retribution.

This brush painting by Sengai is about the story of the Chan monk 天然 Tianran (739-824), a disciple of 石頭 Shitou. One frigid cold winter evening Tianran was staying at a temple in Changan. Chattering with cold he took one of the wooden Buddha images from the altar and burned it in the stove to warm his backside. When the temple director saw this he was shocked and exclaimed,

'How can you do such an onerous thing?'

Tianran replied, 'I'm collecting sarira from the Buddha image's ashes'.

'How stupid to think you can get sarira from a statue!, retorted the monk.

'Then please hand me another, it's a cold night', replied Tanxia.

See the book Sengai, The Zen Master, by Daisetz T. Suzuki, New York Graphic Society, 1971

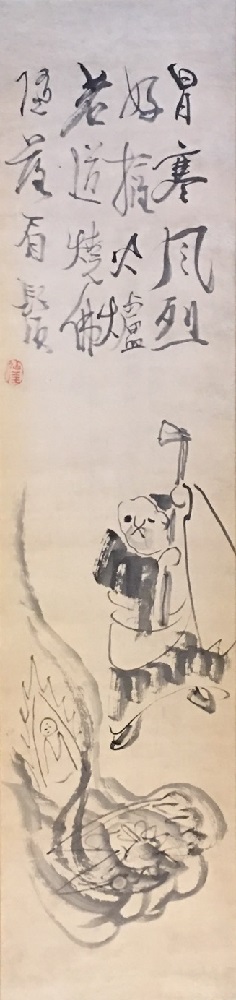

丹霞焼仏

by Sengai Gibbon (1750-1837)

115 cm × 28 cm

冒寒風烈

好擁火爐

若道燒佛

墮落眉鬚

(読み)

冒寒風烈、火炉を擁すに好(よ)し。

焼仏と道(い)ふが若(ごと)く、眉鬚堕落す。

【冒寒】冷気をつく。【風烈】風が激しく吹く。

禅僧丹霞天然(739~824)の有名な焼仏の話を描いたもので、禅画の題材に好んで用いられます。

The Blue Cliff Record

Translated by Thomas F. Cleary, Jonathan Christopher Cleary

SEVENTY-SIXTH CASE: Tan Hsia's Have You Eaten Yet?

垂示云。細如米末。冷似氷霜。畐塞乾坤。離明絕暗。低低處觀之有餘。高高處平之不足。把住放行。總在這裏許還有出身處也無。試舉看 畐(拍逼切滿也)。

POINTER

Fine as rice powder, cold as icy frost, it blocks off heaven and earth and goes beyond light and dark. Observe it where it's low and there's extra; level it off where it's high and there's not enough. Holding fast and letting go are both here, but is there a way to appear or not? To test I'm citing this old case: look!

【七六】Tanka's "Eating Rice"

Tanka asked a monk, "Where have you come from?" The monk answered, "From the foot of the mountain." Tanka asked, "Have you eaten your rice?" The monk said, "Yes I have eaten it."

Tanka said, "The one who brought rice and gave it to you to eat did he have an [enlightened] eye?" The monk said nothing. Chokei asked Hofuku, "Surely it is an act of thanksgiving [1] to bring rice and give it to the people to eat. How then is it possible not to have an [enlightened] eye?" Hofuku said, "Server and receiver are both blind." Chokei said, "Even if one has done everything, does one still remain blind, or not?" Hofuku said, "Do you call me blind?"

[1]: That is, for the guidance already received from buddhas, patriarchs and masters.

舉。丹霞問僧。甚處來(正是不可總沒來處也。要知來處也不難)僧云。山下來(著草鞋入爾肚裏過也。只是不會。言中有響諳含來。知他是黃是綠)霞 云。喫飯了也未(第一杓惡水澆。何必定盤星。要知端的)僧云。喫飯了(果然撞著箇露柱。却被旁人穿却鼻孔。元來是箇無孔鐵鎚)霞云。將飯來與汝喫底人。還 具眼麼(雖然是倚勢欺人。也是據欵結案。當時好掀倒禪床。無端作什麼)僧無語(果然走不得。這僧若是作家。向他道。與和尚眼一般)長慶問保福。將飯與人 喫。報恩有分。為什麼不具眼(也只道得一半。通身是遍身是。一刀兩段。一手擡一手搦)福云。施者受者二俱瞎漢(據令而行。一句道盡。罕遇其人)長慶云。盡 其機來。還成瞎否(識甚好惡。猶自未肯。討什麼碗)福云。道我瞎得麼(兩箇俱是草裏漢。龍頭蛇尾。當時待他道盡其機來。還成瞎否。只向他道瞎。也只道得一 半。一等是作家。為什麼前不搆村。後不迭店)。

CASE

Tan Hisa asked a monk, “Where have you come from?” [1] The monk said, “From diown the mountain.”[2] Hsia said, “Have you eaten yet or not?”[3] The monk said, “I have eaten.”[4] Hsia said, “Did the person who brought you the food to eat have eyes or not?”[5] The monk was speechless.[6]

Ch'ang Ch'ing asked Pao Fu, “To give someone food to eat is ample requital of the debt of kindness: why wouldn't he have eyes?”[7] Fu said, “Giver and receiver are both blind.”[8] Ch'ang Ch'ing said, “If they exhausted their activity, would they still turn out blind?”[9] Fu said, “Can you say that I'm blind?”[10]

NOTES

[1] It's truly impossible to have no place at all you've come from. If he wants to know where he's come from, it won't be hard.

[2] He has put on his straw sandals and walked into your belly. It's just that you don't understand. There's an echo in this words, but he keeps it to himself. Is he yellow or green?

[3] A second ladleful of foul water douses the monk. Why just the zero point of a scale? He wants to know the real truth.

[4] As it turns out, he's collided with the pillar. After all, he's had his nostrils pierced by a bystander. From the beginning it's been an iron hammer head with no handle hole.

[5] Although he is relying on his power to mystify the man, he is also wrapping up the case on the basis of the facts. At the time he deserved to have his meditation seat overturned. Why is there no reason for what he did?

[6] After all, he couldn't run. If this monk had been an adept he would have said to him, “The same as your eyes, Teacher.”

[7] He's still only said half. Is it “throughout the body” or is it “all over the body”? One cut, two pieces. One hand lifts up, one hand presses down.

[8] He acts according to the imperative. With one line he says it all. Such a man is rarely encountered.

[9] What does he know of good and evil? He still isn't settled himself: what bowl is he looking for?

[10] The two of them are both in the weeds. Fu has a dragon's head but a snake's tail. At the time when he said, “If they had exhausted their activity, would they still turn out blind?” I would have just said to him, “You're blind.” Since they're both adepts, why is it that “ahead they didn't reach the village, behind they didn't get to the shop”?

鄧州丹霞天然禪師。不知何許人。初習儒學。將入長安應舉。方宿於逆旅。忽夢白光滿室。占者曰。解空之祥。偶一禪客問曰。仁者何往。曰。選官去。禪 客曰。選官何如選佛。霞云。選佛當往何所。禪客曰。今江西馬大師出世。是選佛之場。仁者可往。遂直造江西。才見馬大師。以兩手托幞頭脚。馬師顧視云。吾非 汝師。南嶽石頭處去。遽抵南嶽。還以前意投之。石頭云。著槽廠去。師禮謝。入行者堂。隨眾作務。凡三年。石頭一日告眾云。來日剗佛殿前草。至來日。大眾各 備鍬鋤剗草。丹霞獨以盆盛水淨頭。於師前跪膝。石頭見而笑之。便與剃髮。又為說戒。丹霞掩耳而出。便往江西。再謁馬祖。未參禮。便去僧堂內。騎聖僧頸而 坐。時大眾驚愕。急報馬祖。祖躬入堂。視之曰。我子天然。霞便下禮拜曰。謝師賜法號。因名天然他古人天然。如此頴脫。所謂選官不如選佛也。傳燈錄中載其語 句。直是壁立千仞。句句有與人抽釘拔楔底手脚。似問這僧道。什麼處來。僧云。山下來。這僧却不通來處。一如具眼倒去勘主家相似。當時若不是丹霞。也難為收 拾。丹霞却云。喫飯了也未。頭邊總未見得。此是第二回勘他。僧云。喫飯了也。懵懂漢元來不會。霞云。將飯與汝喫底人。還具眼麼。僧無語。丹霞意道。與爾這 般漢飯喫。堪作什麼。這僧若是箇漢。試與他一劄。看他如何。雖然如是。丹霞也未放爾在。這僧便眼眨眨地無語。保福長慶。同在雪峯會下。常舉古人公案商量。 長慶問保福。將飯與人喫。報恩有分。為什麼不具眼。不必盡問公案中事。大綱借此語作話頭。要驗他諦當處。保福云。施者受者二俱瞎漢。快哉到這裏。只論當機 事。家裏有出身之路。長慶云。盡其機來。還成瞎否。保福云。道我瞎得麼。保福意謂。我恁麼具眼。與爾道了也。還道我瞎得麼。雖然如是。半合半開。當時若是 山僧。等他道盡其機來。還成瞎否。只向他道瞎。可惜許。保福當時。若下得這箇瞎字。免得雪竇許多葛藤。雪竇亦只用此意頌。

COMMENTARY

“Tan Hsia” was Ch'an Master T'ien Jan of Tan Hsia in Teng Province of Honan---I don't know what locality he was from. At first he studied Confucianism, intending to go to Ch'ang-an to take part in the examinations for official posts. Then unexpectedly while he was staying over at a travellers' lodge, he dreamed that a white light filled the room. A diviner said, “This is an auspicious omen of understanding emptiness.” There happened to be a Ch'an traveller there who asked him, “Good man, where are you going?” He said, “To be chosen to be an official.” The Ch'an traveller said, “How can choosing an official career compare to choosing Buddhahood?” Tan Hsia asked, “What place shold I go to to choose Buddhahood?” The Ch'an traveller said, “At the present time Grand Master Ma has appeared in the world in Kiangsi. This is the place to choose Buddhahood---you should go there, good man.”

After this Tan Hsia went directly to Kiangsi. The moment he saw Grand Master Ma he lifted up the edge of his turban (to look at Ma). Master Ma observed him and said, “I am not your Teacher---go to Shih T'ou's place in Nan Yueh.” Tan Hsia hastened to Nan Yueh where he submitted to Shih T'ou with the same idea as before (at Ma Tsu's place). Shih T'ou told him to go to the stable, and Tan Hsia bowed in thanks. He entered the workmen's hall and worked along with the congregation for three years.

One day Shih T'ou announced to the assembly, “Tomorrow we're going to clear away the weeds in front of the Buddha's shrine.” The next day everyone equipped himself with a hoe to cut down the weeds. Tan Hsia alone took a bowl, filled it with water, and washed his head; then he knelt in front of Master Shih T'ou. Shih T'ou saw this and laughed at him, then shaved his head for him. As Shih T'ou began to explain the precepts for him, Tan Hsia covered his ears and went out.

Then Tan Hsia headed for Kiangsi to call again on Ma Tsu. Before meeting with Ma Tsu to pay his respects, he went into the monks' hall and sat astride teh neck of the holy statue (of Manjusri). At the time everybody became very perturbed and hurried to report this to Ma Tsu. Tsu personally went to the hall to have a look at him and said, “My son is so natural.” Hsia immediately got down and bowed saying, “Thank you, Master, fior giving me a Dharma name.” Because of this he was called T'ien Jan (which means natural). This man of old Tan Hsia was naturally sharply outstanding like this. As it is said, “Choosing officialdom isn't as good as choosing Buddhahood.” His sayings are recorded in the Records of the Transmission of the Lamp.

His words tower up like a thousand-fathom wall. Each and every line has the ability to pull out nails and extract pegs for people, like when he asked this monk, “Where have you come from?” The monk said, “From down the mountain,” yet he didn't communicate where he had come from. It seemed that he had eyes and was going to reverse things and examine the host. If it hadn't been Tan Hsia, it would have been impossible to gather him in.

But Tan Hsia said, “Have you eaten yet or not?” At first he hadn't been able to see this monk at all, so this is the second attempt to examine him. The monk said, “I have eaten.” From the beginning this confused and ignorant fellow hadn't understood. Hsia said, “Did the person who brought you the food to eat have eyes or not?” and the monk was speechless. Tan Hsia's meaning was, “What's the use of giving food to such a fellow as you?” If this monk had been a fellow (with eyes) he would have given Tan Hsia a poke to see what he would do. Nevertheless, Tan Hsia still didn't let him go, so the monk was (left standing there) blinking stupidly and speechless.

When Pao Fu and Ch'ang Ch'ing were together in Hsueh Feng's congregation, they would often bring up the public cases of the Ancients to discuss. Ch'ang Ch'ing asked Pao Fu, “To give someone food is ample requital of kindness: why wouldn't he have eyes?” He didn't have to inquire exhaustively into the facts of the case; he could take it all in using these words to pose his question. He wanted to test Pao Fu's truth. Pao Fu said, “Giver and receiver are both blind.” How direct! Here he just discusses the immediate circumstances---inside his house Pao Fu has a way to assert himself.

When Ch'ang Ch'ing said, “If they had exhausted their activity, would they still turn out blind?” Pao Fu said, “Can you say that I'm blind?” Pao Fu meant, “I have such eyes to have said it all to you---are you still saying I'm blind?” Nevertheless, it's half closed and half open. At that ime if it had been me, when he said, “If they had exhausted their activity, would they still turn out blind?” I would have just said to him, “You're blind.” What a pity! If Pao Fu had uttered this one word “blind” at that time, he would have avoided so many of Hsueh Tou's complications. Hsueh Tou too just uses this idea to make his verse:

盡機不成瞎(只道得一半。也要驗他過。言猶在耳) 按牛頭喫草(失錢遭罪。半河南半河北。殊不知傷鋒犯手) 四七二三諸祖師(有條攀條。帶累先聖。不唯只帶累一人) 寶器持來成過咎(盡大地人換手搥胸。還我拄杖來。帶累山僧也出頭不得) 過咎深(可殺深。天下衲僧跳不出。且道深多少) 無處尋(在爾脚跟下。摸索不著) 天上人間同陸沈(天下衲僧一坑埋却。還有活底人麼。放過一著。蒼天蒼天) 廠(齒兩切馬屋無壁也) 眨(側洽切目動也)

VERSE

(Ch'ang Ch'ing) exhausts his activity, (Pao Fu) doesn't become blind---

They've only said half. Each wanted to test the other. The words are still in our ears.

(Like) holding down an ox's head to make it eat grass.

They lose their money and incur punishment. Half south of the river, half north of the river. Without realizing it, they've run afoul of the point and cut their hands.

Twenty-eight and six Patriarchs---

If you have a rule, hold on to the rule. Hsueh Tou is dragging down the former sages, he doesn't just involve one man.

Their precious vessel is brought forth, but it turns out to be an error.

Everyone on earth beats his breast (in sorrow). Give me back my staff. They've dragged me down so that I can't even show my face.

The error is profound---

Extremely profound. The world's patchrobed monks cannot leap clear of it. But tell me, how profound?

There's no place to look for it.

Though it's right beneath your feet, it can't be found.

Gods and humans sink down together on dry land.

The world's patchrobed monks are all buried in one pit. Is there anyone alive? I let my move go. Heavens! Heavens!

盡機不成瞎。長慶云。盡其機來。還成瞎否。保福云。道我瞎得麼。一似按牛頭喫草。須是等他自喫始得。那裏按他頭教喫。雪竇恁麼頌。自然見得丹霞 意。四七二三諸祖師。寶器持來成過咎。不唯只帶累長慶。乃至西天二十八祖。此土六祖。一時埋沒。釋迦老子。四十九年。說一大藏教。末後唯傳這箇寶器。永嘉 道。不是標形虛事褫。如來寶杖親蹤跡。若作保福見解。寶器持來。都成過咎。過咎深無處尋。這箇與爾說不得。但去靜坐。向他句中點檢看。既是過咎深。因什麼 却無處尋。此非小過也。將祖師大事。一齊於陸地上平沈却。所以雪竇道。天上人間同陸沈。

COMMENTARY

“(Ch'ang Ch'ing) exhausts his activity, (Pao Fu) doesn't become blind.” Ch'ang Ch'ing said, “If they exhausted their activity, would they still turn out blind?” Pao Fu said, “Can you say that I'm blind?” This was all like “Holding down an ox's head to make it eat grass.” To get it right you must wait till he eats on his own: how can you push down an ox's head and make him eat? When Hsueh Tou versifies like this, naturally we can see Tan Hsia's meaning.

“Twenty-eight and six Patriarchs---/Their precious vessel is brought forth, but it turns out to be an error.” Not only does Hsueh Tou drag down Ch'ang Ch'ing, but at the same time he buries the twenty-eight Patriarchs of India and the six Patriarchs of this country. In forty-nine years, old man Shakyamuni preached the whole great treasurehouse of the Teachings; at the end he only transmitted this precious vessel. Yung Chia said, “This is not an empty exhibition displaying form: it's the actual traces of the Tathagata's jewel staff.” If you adopt Pao Fu's view, then even if you bring forth the precious vessel, it all turns out to be an error.

“The error is profound---/There's no place to look for it.” This can't be explained for you: just go sit quietly and inquire into his lines and see. Since the error is profound, why then is there no place to look for it? This is not a small mistake: he takes the Great Affair of the Buddhas and Patriarchs and submerges it entirely on dry land. Hence Hsueh Tou says, “Gods and humans sink down together on dry land.”

Ch'an Poems

written by the Monk Tan Hsia

CW33_No.91

Translated by the Buddhist Yogi C. M. Chen

On water bottom, mud-bulls till the ground of white moon!

In the clouds, the wooden horse flies in wind very soon!

The Indian monk does not like to hold his Bhikshu bowl!

At middle night rows his boat through vast sea and passes on!

In every home, there's the moon light passing the window.

At everywhere there's birds singing in wind and willow.

You may say hither and thither there is no change,

Like throw the sword to the sky done by the Hero!

It is too subtle to be seen!

You get blood but never win!

Why none talk about it's price?

Because it's not worldly thing!

The cool moon climbs up the high peak at night!

Many miles plain-lake covered with her light!

Fishman's song startles the egret flying away,

From the reed we see only a piece of white!

In the deep palace, there's nothing to be known,

The Jade-Altar has clouds of fog to adorn !

Political talks have been done by officials,

The Dharma-king does not like to wear the crown!

Spring flowers have not blossomed but plum is out,

While pines are still green, all other trees are nought,

Thin clouds do not play the moon-shadow,

Nor slight fog hits the small branches to spout!

The cool moon climbs up the high peak at night!

Many miles plain-lake covered with her light!

Fishman's song startles the egret flying away,

From the reed we see only a piece of white!

In the deep palace, there's nothing to be known,

The Jade-Altar has clouds of fog to adorn !

Political talks have been done by officials,

The Dharma-king does not like to wear the crown!

Spring flowers have not blossomed but plum is out,

While pines are still green, all other trees are nought,

Thin clouds do not play the moon-shadow,

Nor slight fog hits the small branches to spout!

In the night moon is like magic spell.

I turn my body and beat the bell!

The loud voice flies up beyond heavens,

Why those devas still have their sleep so well!

White lotus-root in the mud is not wrong,

Red flower is hid by leaves without sun.

Wanderers don't tell the false message,

The pure wind will pass her sweet smell so long!

This shore or that shore, both miss it!

No-egoism is not in the midst!

Sun sets under the west mount,

Yet its shade remains in the East!

Pure wind moves the fishing boat to work.

Puffs up the tide touching the sky, Look!

Those fish play together with deep love.

At last they cannot free from the hook!

Long river is more clear than moon light.

It's not home, though everywhere bright!

"Oh! Dear fishman, where shall you return?"

"I still sleep close to reed at this night!"

It cannot be seen, how could you say?

Nothing is in same form, on same way!

In the mossy altar, there's none serves,

Moon light shines on tree, Phoenix doesn't stay!

Wooden man asks for the heaven land.

Jade girl seems deaf, does not comprehend.

Yet they both back home arm in arm.

Leave the mount circled by clouds without end!

In the subtle truth, there's nothing to gain.

But it is not that all is in Vain!

Moon reflects in sea, fish disappear,

YouCfishman, why throw the hook again !

Outside the fence, white clouds are so vast!

Sword can't cut, even you test,

The deep cave needs not anything to lock

To and fro freely without request!

When I'm hungry, I eat grass green.

When thirsty, I drink cool spring!

I do not plough the empty ground,

Cowboy needs not call me with sound!

On that shore I cannot pass.

I return without ask path.

In the altar there's no monk.

Just moon light comes across!

It is round and can't be told.

Let those men and women hold.

Though paints up the sky, so noble;

Still a man passing the word!

Shih-Teh seems too silly, doesn't know day or night;

Han-San seems too lazy, doesn't turn left or right.

The perfect, round voice before talk is so nice,

Beyond the cosmos the moon is very bright!

The sweet message is not so common,

The smell of moon flowers lasts so long!

At last night Chan-O appears nicely,

Turns up her eyes, yet draws the Yuan-Yang!

Dragon sings in the sea, rains come in time!

Lion roars in the mount, wind blows so fine!

Don't worry about the thorn on the path,

At our poor home. there's no guest sublime!

With horn and hair, he becomes cattle so fast!

To his eyes all ashes and woods both are dust!

Though he didn't comprehend his Guru's truth,

When his death comes by, he realizes at last!

His dignity form with wonderful light,

No one so skillful as to draw him right.

Not only Wu-Tao-Tze cannot do it,

Even Tze-Kun himself has no such might!

In winter all trees have some wrong,

But plum root has its warm alone.

See the front village after snow,

There is the flower to blossom !

Moon makes the pine shadow, some long some short,

Sun shines on lake, two skies but not apart!

The heat in heaven does not know the noon,

The full moon of August doesn't know the art!

Most are learned from other man,

They open their mouths in vain!

No one knows the whole brightness,

Buddha can't know how you can?

Though one mind, through many years can't be found,

From nude take off skin, nothing to be bound!

See the blue sky, it is like a mirror,

Many miles have no cloud but moon is round!!!

火燒木佛 BURNING THE WOODEN BUDDHA

by 文姚育明 Yao Yuming

Vajra Bodhi Sea, No 319.

http://www.drbachinese.org/vbs/publish/319/vbs319p038.htm

Dhyana Master Danxia's burning of a Buddha image to get warmth won the admiration of people in later generations. Such people think that to do away with worthies and sages, fathers and mothers, teachers and superiors, as well as all rules is to follow the way of spontaneity, to accord with Nature. Such unmitigated arrogance is truly pitiful.

When Chan Master Danxia knelt and bowed, it was to the Buddha, the self nature. When he burned the image, what he burned was wood, using the nature of fire. In saying that the mind has no discriminations, actually, there are distinctions made; it's just that mundane principles and the principles contained in the Teaching become perfectly fused when one's wisdom opens. Even if he burned all the Buddha images in all the temples and monasteries, he still could not change the fact that Shakyamuni Buddha was his Guiding Master.

By the same principle, if I attempt to destroy the faith which the Chan school proudly places in this story, then that would merely be for my own personal satisfaction. The Chan school is still the Chan school; a Buddha is still a Buddha; and I am still a common person. What if an image of a common person were be burned? At most, the person's family members would fight with you. But the story of Chan Master Danxia burning the wooden Buddha has been discussed for several hundred years. If there were nothing in it, why would people bother to keep talking about it? Only brilliant events warrant such a reaction; and even if one might wish to erase it from history, it cannot be done.

The magnificence of the Buddha is also shown in this: Even after he entered Nirvana, people could still get warmth from a wooden likeness of him.

[Editor's Note] Dhyana Master Tianran (Natural) of Tang Dynasty got the name because his nature was natural and unpretentious. Moreover, because he lived on Mount Danxia, he was reverently addressed as Dhyana Master Danxia. One day, he happened to go to Huilin Monastery in Loyang. The night became freezing, and so he took a carved wooden Buddha and burned it to get warmth. Everyone was astonished and scolded him. The Dhyana Master said, "I'm burning it to get sharira." The assembly asked, "How can you get sharira from burning wood?" The Dhyana Master said, "Since wooden Buddhas don't possess sharira, go and get another couple of images to burn!"

Buddhism came into China at the end of Han Dynasty and became popular after the Six Dynasties period. Down to Tang Dynasty, not only were there many talented sages, but enormous schools developed after the time of the Sixth Patriarch. At that time, those who followed the Teaching School attached to the attributes of teaching and failed to realize the mind is the Buddha. Therefore, the Chan School did not rely on language, but used real actions to break through people's attachments. This public record became so renowned in the Chan School that people of later generations cited it over and over, praising it as the ultimate state of no attributes and no attachments. The state was high all right, but such an act could only be done by a person like Dhyana Master Danxia, who was completely natural and sincere, perfect and without obstructions. No one could possibly imitate that example. At that time, people attached to "the existence of form" and failed to realize that the mind is the Buddha; students of later generations blindly admired and superficially imitated his behavior, attaching to "emptiness of non-obstruction" and turning it into intellectualizing about Chan. They fell into the two extremes and failed to realize the self nature, and so they still had obstructions.

As a matter of fact, if one says that what Dhyana Master Danxia did was deliberately designed to break through attachments, that's not completely true. Based on what he was, his action was more likely straightforward and natural, free of any consideration or attention. He was just doing what was necessary in that circumstance. That's why he was called Dhyana Master Tianran (Natural). He didn't get that name for no reason. As it's said in Upasika Yao's essay, " When Chan Master Danxia knelt and bowed, it was to the Buddha, the self nature. When he burned the image, what he burned was wood, using the nature of fire. Even if he burned all the Buddha images in all the temples and monasteries, he still could not change the fact that Shakyamuni Buddha was his Guiding Master." We could even say, "Even if he burned all the wooden Buddhas, he still could not change the fact that he was the master of his self nature. He was worshipping the Buddha of his self nature."

As for slander and praise of those in the world, it has nothing to do with him or with the Buddha. "The Chan school is still the Chan school, a Buddha is still a Buddha."

Denkōroku

The Record of the Transmission of the Light by Zen Master Keizan Jokin,

Translator Reverend Hubert Nearman,

OBC Shasta Abbey Press, Mount Shasta, California, 2003.

CHAPTER 47.

THE FORTY-SIXTH ANCESTOR,

MEDITATION MASTER TANKA SHIJUN.

When Tanka asked Fuyō, “What is the one phrase that all

the sages have passed on from the beginning?” Fuyō answered,

“Were you to reduce IT to a single phrase, you would really bury

the tradition of our line.” Upon hearing this, Tanka had a great

awakening to his TRUE SELF.

Tanka’s personal name was Shijun (C. Tzu-ch’un, ‘Pure and

Honest as a Child’); he was an offspring of the Ko (C. Chia)

clan in Kenshū (C. Chien-chou). When he was barely twenty he

left home to become a monk; he penetrated to the PROOF whilst

in Fuyō’s quarters. At first he resided on Snowy Peak Mountain

Mountain (J. Tankazan; C. Tan-hsia-shan).

His first inquiry was, ‘What is the one phrase that all the

sages have passed on from the beginning?’ Even though Buddha

after Buddha and Ancestor after Ancestor has changed in outer

appearance, beyond doubt something has passed on which is

without back or front, top or bottom, inside or outside, self or

other. IT, THE EMPTINESS THAT IS NOT EMPTY, is the TRUE

PLACE to which all return; there has never been anyone who has

not possessed IT fully and completely, however many students

make the mistake of thinking that originally there was nothing

at all, saying moreover that there is nothing that can be said

about IT and nothing that the mind can conceive about IT.

The ancients gave such people the name of ‘non-Buddhists

who have fallen into vacant nothingness’. Although kalpas as

numerous as the sands of the Ganges River may pass, in no way

will any such be liberated, therefore, even if you are thorough

and meticulous so that every single thing is brought to an end

and is utterly emptied, there will still be SOMETHING that cannot

be emptied. Look inwards and probe deeply into yourself; once

you succeed in catching a glimpse of IT, without fail you will be

able to come up with a phrase to express this. This is why we

speak of it as ‘the one phrase that has been passed on’.

As stated above, Fuyō commented, “Were you to reduce IT

to a single phrase, you would really bury the tradition of our

line.” Truly this ‘realm’ is not something that can be designated

by a single phrase; that would be using words incorrectly and

resembles bird tracks in the snow. Because of this, it is said,

‘A hiding-place shows no traces of its whereabouts’. When

seeing, hearing, cognizing and comprehending utterly cease,

and skin, flesh, bones and marrow are all gone, then what traces

of anything can remain? If you do not create even a smidgeon

of evidence, sure enough, IT will come to appear. IT is not

something that others will know about which is why IT is not

something that is passed on openly, however, when this ‘realm’

can be realized, it is spoken of as ‘Heart Transmitting Heart’.

This occasion is referred to as ‘the uniting of lord and retainer’

or as ‘the oneness of the absolute and the relative’.

Now tell me, what do you think the form of this ‘realm’ is?

Though a clear breeze swirls round and round, stirring up the earth,

Who can grasp hold of it and show it to you?

CHAPTER 48.

THE FORTY-SEVENTH ANCESTOR,

MEDITATION MASTER CHÜRO SEIRYÜ.

Seiryō trained under Tanka who asked him, “What is the

SELF prior to the period of cosmic emptiness?” Seiryō was just

about to respond when Tanka said, “Since you are being so

noisy, go away for a while.” One day, whilst climbing Begging

Bowl Peak (J. Hachi’uhō; C. Po-yü-feng), Seiryō suddenly

awoke to his TRUE SELF.

Seiryō (C. Ch’ing-liao, ‘Clear in Intelligence’) was his personal

name, Shinketsu (C. Chen-hsieh, ‘Truly at Rest’) was his

Buddhist name and Gokū (C. Wu-k’ung ‘The Enlightened

Void’) was his title as a meditation master. Whilst he was still in

swaddling clothes, his mother, cradling him in her arms, took

him into a temple; upon seeing a statue of Buddha, he raised his

eyebrows and blinked with delight. Everyone considered this

unusual; in his eighteenth year he lectured on the Lotus Scripture.

After being ordained he travelled to Taie Monastery

(C. Ta-tz’u) in Seito (C. Ch’eng-tu) in Szechwan Province

where he was taught the Scriptures and Commentaries, taking

note of their substantive meaning. Leaving Szechwan he proceeded

to the Yangtze and Han River area where he knocked on

Tanka Shijun’s door. When Tanka asked him, “What is the

SELF prior to the period of cosmic emptiness?” what was stated

above occurred up to the point where Seiryō suddenly awoke to

his TRUE SELF. He returned at once from Begging Bowl Peak

and stood in attendance on Tanka. Tanka gave him a slap and

said, “I would say that without doubt you know IT exists.”

Seiryō joyfully bowed before him. The next day Tanka entered

the meditation hall and said in verse,

“The sun makes the solitary peak glow green,

The moon visits the valley stream so chill;

The dark and wondrous SECRET of the Ancestors and Masters

Does not turn toward a trifling heart to find a resting place.”

He then got down from his seat. Seiryō immediately came

before him and said respectfully, “Your preaching of the

Dharma today could not deceive me in the least.” Tanka said,

“Come, try to present to me the meaning of my lecture today.”

Seiryō was still for some time. Tanka said, “Without doubt I

would say that you have glimpsed that ‘realm’.”

After Seiryō left Mount Tanka he travelled to Mount Godai

(C. Wu-t’ai), went on to the capital, sailed the River Ben

(C. Pien) and forthwith reached Long Reed Mountain (J. Chōrozan;

C. Ch’ang-lu-shan) where he had an audience with Sōshō

(C. Tsu-chao). No sooner had they talked together than they

found that they were in complete accord and Sōshō made Seiryō

his jisha; after a year had passed, they were sharing the seat

of teaching. Not long afterwards Sōshō, pleading illness,

retired as abbot and had Seiryō inherit the abbot’s seat; students

flocked to him. Around the end of 1130 he travelled to

Mount Shimei (C. Hsi-ming) and then went on to Mount Hoda

(C. Pu-t’o). He became abbot at Tenpō Monastery (C. T’ienfeng)

in Daishū (C. T’ai-chou) and at Snowy Peak Monastery

(J. Seppō; C. Hsieh-feng) in Binshū (C. Ming-chou). By

imperial edict he was made abbot at Iku’ō Monastery (C. Yü-

wang) and subsequently at Ryūshō Monastery (C. Lungshang)

in Onshū (C. Wen-chou). He was also abbot at Mount

Kei (C. Ching) in Kōshū (C. Hang-chou). Jinei (C. Tz’uning),

the emperor’s mother, requested that he establish a mountain

monastery on Mount Sūsen (C. Ch’ung-shen) at Kōnei

(C. Kao-ning).

From the time that he was in swaddling clothes he was not

one of the herd and stood apart from others; as his resolve to

study Zen meditation progressed, he intensified his efforts.

When he was asked about the SELF prior to the period of cosmic

emptiness, he tried to respond but Tanka did not give his

approval and had him leave for a while. One day, whilst climbing

to the top of Begging Bowl Peak, all ten quarters were

unobstructed and there were no barriers on any of the four sides

as well. Upon reaching the moment when the ten quarters

appeared right before his eyes, he grasped what IT was; when he

came back he stood before Tanka without saying a single word.

Tanka, realizing that Seiryō knew that IT existed, said, “Without

doubt I would say that you have glimpsed that ‘realm’,” Seiryō

then joyfully bowed before Tanka and Tanka entered the meditation

hall and acknowledged Seiryō’s awakening. Later, when

Seiryō went forth to teach, he entered the meditation hall one

day and said, “When I was given a slap by my former master all

my abilities and talents had been exhausted and, try as I may, I

was unable to open my mouth. Is there any person here now

who has not been able to experience such happiness as this? If

you would not have an iron bit between your teeth or a saddle

on your back, each of you must reach THAT which is the ideal.”

When the Ancestors and Masters actually meet face to face

they step forth into THAT which is prior to the period of cosmic

emptiness and immediately manifest the natural beauty of the

fundamental ‘realm’. If you have not yet seen this ‘realm’, then,

even though you sit without uttering a sound for ten million

years, immobile as a withered tree or like dead ashes, what use

will it be? However, when some people hear about ‘THAT which

is prior to the period of cosmic emptiness’ they mistakenly

think that it means that there is no self or other, no before or

after, no arising or extinction, no sentient beings or Buddhas,

that IT must not be called ‘one’ or ‘two’, that IT must not be discerned

as identical with themselves or be called different from

themselves. Deliberating and evaluating in this way, they judge

that if someone utters a single word he has immediately deviated

from the Dharma or imagine that if someone hatches even a

single thought he must have turned his back on the ETERNAL;

they rashly cling to images of withered trees and dead ashes

and become like corpses. Some think on occasion that there are

no disparities whatsoever between ‘HIM’ and ‘me’ so IT can be

interpreted as a ‘mountain’ or as a ‘river’ or as ‘me’ or as

‘other’. Sometimes they say, “What you call a mountain is not a

mountain and what you call a river is not a river; only this is a

mountain, only this is a river,” and so they go on, but to what

use? All this directs them onto false paths. They either become

attached to forms and appearances or fall into nihilism.

How can you possibly hope to arrive at this ‘realm’ by

means of such notions as existence or non-existence? There is

nowhere for you to poke your tongue in, no time for you to set

your thoughts and fears spinning around. IT does not depend on

heaven or earth, or on before or after. Focus on that place where

there is nowhere beneath your feet to step; without fail you will

be a bit in accord with IT. Some speak of IT as beyond any

patterns or rules, others as not conveying a breath of anything.

All this is within the boundaries of deliberate thought and

ultimately ends with their turning their backs on the TRUE SELF;

even more so do they do this if they say that IT is the moon or

snow or water or wind. All such people undoubtedly have

cataracts in their eyes or are seeing flowers falling hither and

thither in the sky. What do they mean by referring to IT as a

‘mountain’? In the final analysis they are not seeing a single

thing. What are they coming in contact with that they would

make IT out to be cold or hot? Ultimately there is not a single

thing that has been imparted to them and this is why they

become attached to trees and grass. If you completely sweep

away both ‘the ways of the world’ and ‘the Buddha’s Dharma’

at one and the same time and just look, you will ultimately not

doubt. Do not turn within or without to seek IT. Do not wish to

calm your thoughts, do not desire to make your body tranquil.

Just know IT intimately, just understand IT intimately. Cut all

ties at once and try to sit for a while. Even though it is said that

there is nowhere in the four quarters to take a step and no place

in heaven or on earth to slip in a body, you will really not need

to borrow from anyone else’s strength. When you see in this

way, then no skin, flesh, bone or marrow is allotted to you; no

birth or death, coming or going, alters you. When you have

sloughed off your skin, only the ONE REALITY remains. IT

glitters in the past and sparkles in the present. IT does not

discriminate about, or measure, time. How can IT possibly be

referred to simply as ‘that which is prior to the period of cosmic

emptiness’?

This state is not something understandable in terms of

before and after; this realm does not mirror the four cosmic

periods of creation, sustained existence, disintegration and

emptiness. Can both self and other be understood as being without

cause? When you forget about external boundaries, rid

yourself of your inner cogitations and ‘the clear blue sky still

gets a beating’, you will be purified, completely stripped naked

and rinsed clean. If you are able to see IT in detail, IT will be as

illusive as space, as subtle as emptiness; if you cannot do this

in detail, you will never reach this state. Clearing up karmic

matters of countless kalpas will actually happen in the snap

of your fingers. Without giving in to indecision or displaying

intellectual comprehension, cast your gaze upon HIS face and,

be it but for a moment, look! Without fail you will become

independent, liberated and unobstructed by evil passions, however,

trainees, by twisting your heads and hearts around, you

have already fallen into error and are engaged in contriving.

Although you may feel that this is merely the slightest of

transgressions, you must realize that when you do such things

you will not have a bit of rest for thousands of lives over

myriad kalpas. Reflect upon this carefully and try to arrive

at this ‘realm’ fully. Without depending on others, by being

completely alone you will be like the vast sky when you open

up to the TRUTH.

Now, tell me, how can I communicate even a bit of this

principle?

The old valley stream; its icy spring is hidden from all eyes;

No traveller is permitted to penetrate its ultimate depths.

Danxia Tianran (739-824)

compiled by Satyavayu of Touching Earth Sangha

http://touchingearth.info/dregs/

Master Danxia Tianran was from Dengzhou in Henan province. As a youth he was an avid scholar, and, as was expected of his class, he was headed for a career as a government official. On his way to the capital city of Chang'an to take the civil service examinations, he met a monk who greatly impressed him, and convinced him that the life of a bureaucrat was worthless compared to a life of practicing the Way. So the young man changed course and headed toward the Heng Mountains where he met Master Shitou and joined his community.

Skeptical of the need to become an official monk, he worked as a layman in the temple kitchen for the three years of his training with Master Shitou.. Finally, at the end of his time there, he agreed to receive ordination from the master, and became the monk Tianran. Then he began a long period of traveling to visit other teachers. He visited and practiced at least briefly with many of the well-known masters of his day, including Master Ma in Jiangxi, Nanyang Huizhong in Chang'an, and the Oxhead School teacher Master Daoqin on Jing Mountain in Hangzhou. He was also close friends with the traveling lay practitioner Pangyun, who shared his disdain for monastic piousness.

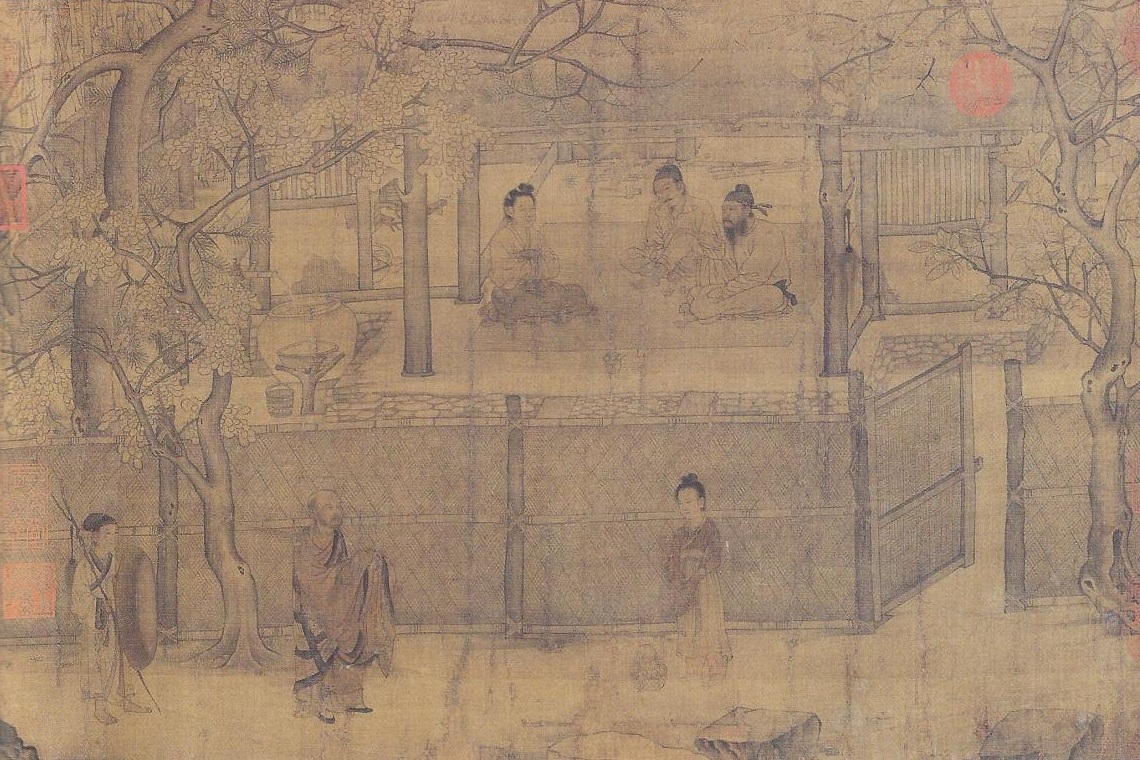

Danxia Tianran visits Layman Pang 丹霞天然問龐居士圖

Attributed to Li Gonglin 李公麟 (d. 1106), 13th or possibly early 14th century

Handscroll, ink and light clours on silk, 35.2 x 52.1 cm

Private collection, New York

Master Tianran is most famous for the following story from his travels: One cold winter day while he was staying at the Wisdom Woods Monastery in Dongjing, Tianran, finding no firewood, took a wooden statue of the Buddha and burned it in the fire to get warm. The temple director saw this, got upset, and yelled, “Why are you burning the Buddha?”

Tianran pulled some embers from the fire and said, “I'm burning this buddha to get the sacred relics.”

The director said, “How can a wooden buddha have sacred relics?”

Tainran said, “Well, if it doesn't, let's burn a couple more of them!”

Tianran eventually returned to his home region of Dengzhou in Henan and settled in a hermitage on Danxia (Red Cloud) Mountain. When he began to attract many students, a large monastery was built for him.

Once the monk Wuxue came to study with him. He asked the master, “What is the teaching of all the awakened ones?”

Master Danxia Tianran exclaimed, “Fortunately, life is fundamentally wonderful! Why do you need to take up a dust rag and broom?”

Wuxue retreated three steps.

The master said, “Wrong.”

Wuxue again came forward.

The master said, “Wrong. Wrong.”

Wuxue then lifted one foot in the air, spun around in a circle, and started to go out.

Master Tianran said, “Such an answer! It's turning your back on all the awakened ones.”

Upon hearing these words, Wuxue had a clear understanding...

* * *

All of you here must take care of this practice place. The things in this place were not made or named by you – have they not been given as offerings? When I studied with master Shitou he told me that I must personally protect these things. There is no need for further discussion.

Each of you here has a place to put your cushion and sit. Why do you suspect you need something else? Is Zen something you can explain? Is an awakened being something you can become? I don't want to hear a single word about Buddhism.

All of you look and see! Skillful practices and the boundless mind of kindness, compassion, joy, and detachment – these things aren't received from someplace else. Not an inch of these things can be grasped... Do you still want to go seeking after something? Don't go using some sacred scriptures to look for emptiness!

These days students of spirituality are busy with the latest ideas, practicing various meditations and asking about “the way.” I don't have any “way” for you to practice here, and there isn't any doctrine to be confirmed. Just eat and drink. Everyone can do that. Don't hold on to doubt. It's the same everyplace!

Just recognize that Shakyamuni Buddha was a regular old fellow. You must see for yourself. Don't spend your life trying to win some competitive trophy, blindly misleading other blind people, all of you marching right into hell, struggling in duality. I've nothing more to say. Take care!

Based on a translation by Andy Ferguson of Danxia's record in the Song Dynasty collections

Tan-hszia Tien-zsan (739-824)

Fordította: Hamvas Béla

Anthologia humana

Tan-hszia egy télen, amikor rendkívül hideg volt, a kolostor templomának fából készült Buddha-szobrát tűzre dobta, és ott melegedett. A templomszolga azt kérdezte:

- Hogyan merted Buddhámat elégetni?

Tan-hszia erre pálcájával a hamuban keresgélni kezdett.

- A halhatatlan részeket keresem itt az üszökben.

- Hogyan éghettek el a szobor halhatatlan részei?

- Ha nincsenek, akkor tűzre tehetem a többi fa Buddhát is?

Később egy barát a szobor elégetésének körülményei felől kérdezősködött. A Mester így szólt:

- Ha hideg van, a tűzhely köré ülünk és a fa lángol.

- Bűn volt vagy sem?

- Ha meleg van, a folyópartra megyünk a bambusznádasba.

Tan-hszia Tien-zsan mondásaiból

Fordította: Terebess Gábor

Folyik a híd, Officina Nova, Budapest, 1990, 80. oldal

Tarnóczy Zoltán illusztrációjaHuj-csung* éppen aludt, amikor Tan-hszia meglátogatta.

– Itthon van a mestered? – kérdezte Tan-hszia a segédet.

– Itthon, de senkit se fogad.

– Rögtön felismerted a helyzetet – dicsérte őt Tan-hszia.

– A mesterem még Buddhát se fogadná tódított a szerzetes.

– Tényleg jó tanítvány vagy! Büszke lehet rád a mestered! – dicsérte még egyszer Tan-hszia, aztán útjára indult.

Amikor Huj-csung felébredt, Tan-jüan – így hívták a segédet – elmesélte, hogy bánt el a látogatóval.

Ám a mester elverte, és kikergette a kolostorból.*Nan-jang Huj-csung (675-755) [南陽慧忠 Nanyang Huizhong; jap.: Nanyō Echū]

李蕭錕 Li Xiaokun (1949-) illusztrációjaVándoréveiben Tan-hszia egy dermesztően hideg templomban éjszakázott. Más tüzelőt nem találván, az oltár egyik fából faragott Buddha szobrával gyújtott be, hogy felmelegedjen.

A templom papja mélységesen felháborodott.

Tan-hszia piszkálgatni kezdte a parazsat:

– Bárhogy keresem, nem találom Buddha csont ereklyéit- mondta.

– Hogy találhatnál csont ereklyéket egy fa-Buddhában?

– Ha nincsenek, akkor raknék még egy szobrot a tűzre!