ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

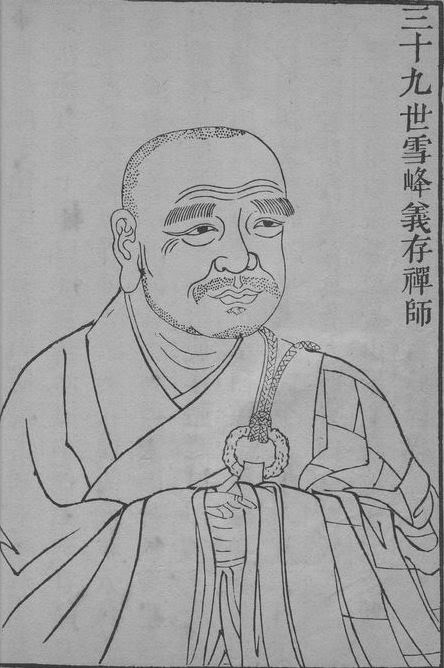

雪峰義存 Xuefeng Yicun (822-908)

師規制 Shi guizhi

(Rōmaji:) Seppō Gison: Shi kisei

(English:) Teacher's rules

(Magyar:) Hszüe-feng Ji-cun: Si kuj-cse

Tartalom |

Contents |

| Hszüe-feng Ji-cun mondásaiból Fordította: Terebess Gábor |

Encounter Dialogues of Xuefeng Yicun Outstanding masters in the Lineage of Shih-t'ou: Hsüeh-feng HSUEH-FENG XUEFENG YICUN 師規制 Shi guizhi (Compiled in 901) |

Encounter Dialogues of Xuefeng Yicun

compiled by Satyavayu of Touching Earth Sangha

DOC: Treasury of the Forest of Ancestors

Maser Xuefeng Yicun grew up in Nan'an City in the Quanzhou region (in southern Fujian Province, on the coast near Taiwan). At the age of twelve he became a novice at the local Jade Valley (Yujian) Monastery. During the Huichang era suppression of Buddhism, Yicun was forced to abandon monastic life, but as conditions improved, he resumed his studies, and began to travel widely seeking out various teachers. He received full ordination at Baocha Monastery in the far northern region of Youzhou (modern Beijing). He then turned his attention exclusively to the Zen tradition, and spent many years traveling between the various masters in the Zen heartland of Jiangxi and Hunan. First Yicun studied with the aging master Yanguan Qi’an, then visited Touzi Datong, and eventually traveled south to Cave Mountain, where he spent a considerable time with Master Dongshan Liangjie.

One day while Yicun was chopping wood, Master Dongshan came by and asked, “What are you doing?”

Yicun said, chopping out a log for a bucket.”

The master said, “How many chops with the ax does it take to complete?”

Yicun said, “One chop will do it.”

The master said, “That’s still a matter of this side. What about the other side?”

Yicun said, “It’s accomplished immediately without laying a hand on it.”

The master said, “That’s still a matter of this side. What about the other side?”

Yicun gave up.

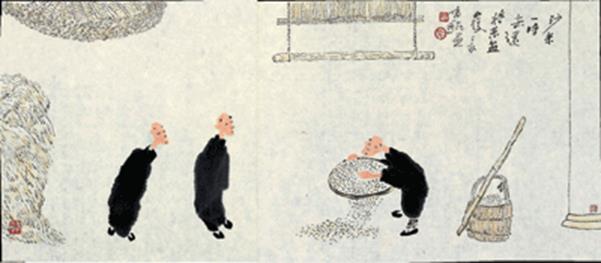

Once, when Yicun was serving as rice cook at Cave Mountain, Master Dongshan came into the kitchen while Yicun was washing the rice and asked him, “Do you remove the dirt and stones from the rice, or the rice from the dirt and stones?”

Yicun said, “I remove them both at once.”

The master said, “Then what will the monks eat?”

Yicun then overturned the rice-pot.

The master said, “Given your character, you might resonate with Master Deshan.”

When Yicun was ready to leave Cave Mountain, he went to say farewell to the master.

Master Dongshan asked him, “Where are you going?”

Yicun said, “I’m traveling through the mountains.”

The master said, “When you came here, what road did you take?”

Yicun said, “I came though Flying Monkey Peaks.”

The master said, “What road will you take now?”

Yicun said, “I’ll go through Flying Monkey Peaks as well.”

The master said, “There is someone who doesn’t go by way of Flying Monkey Peaks. Do you know this person?”

Yicun said, “I don’t know this person.”

The master said, “Why don’t you know this person?”

Yicun said, “Because this person has no face.”

The master said, “If you don’t know this person, how do you know this person doesn’t have a face?”

Yicun didn’t respond.

Eventually Yicun made his way to the community of Master Deshan Xuanjian in Wuling (near modern Changde City, Hunan). There he worked in the kitchen as he had on Cave Mountain, and he befriended the head monk Quanhuo (later of Mt. Yantou, 828-887) who was from the same region of Quanzhou. Although younger than Yicun, Quanhuo had already developed penetrating clarity in his practice, and his confidence made him an able mentor to Yicun.

One day when Yicun was cooking rice in the kitchen, the meal was running late. Stepping outside to hang a rice cloth to dry, he spotted Master Deshan coming to the meal with bowls in hand. Yicun said to the master, “The bell hasn’t been run and the drum hasn’t been struck. Where are you going with your bowls?” The master simply turned around and went back to the abbot’s room.

When Yicun saw Quanhou he told him what had happened. Quanhou said, “Old Master Deshan still doesn’t know the last word.”

The master heard about this and had Quanhou summoned to the abbot’s room. The master asked Quanhou, “Do you not approve of me?” Quanhou then explained his meaning and the master let it go.

The next day Master Deshan ascended the hall to give a talk. Afterwards Quanhou exclaimed to the whole community, “Old Master Deshan knows the last word after all!”

After practicing for awhile together at Virtue Mountain with Master Deshan, Yicun and Quanhou decided to spend some time traveling. When staying overnight in a temple on Aoshan (Turtle Mountain) in Lizhou (Hunan), they were snowed in by a blizzard and had to remain there for several days. Quanhou used the time to catch up on sleep, while Yicun diligently sat in meditation hour after hour. Disappointed with his own practice, and feeling critical of Quanhou’s sleeping, Yicun finally expressed his feelings to his friend. Quanhou chided Yicun for sitting like a clay statue, and urged him to get some sleep himself. Then Yicun confessed that his heart was not at peace, and Quanhou suggested that Yicun bring up his current understanding of Zen for him to check.

Yicun said, “I first studied with Master Yanguan and, hearing him teach on form and emptiness, I found an entrance. Then I heard Dongshan’s poem and was struck by his saying, 'Avoid seeking outside, for that’s far from the self.' Then later I asked Master Deshan if I should make distinctions between the different vehicles of the ancestors or not. He struck me and then said, “What are you talking about?” At that moment I had the experience of the bottom falling out of a bucket of water.”

Quanhou said, “Haven’t you heard that what comes in through the front gate is not the family treasure?”

After a pauseYicun said, “Then what should I do?”

Quanhou said, “If you want to spread the great teaching, it has to flow out from your own heart. Then it will completely cover heaven and earth.”

When Yicun heard these words he had a deep awakening. He made a full bow, then got up and cried out, “Today Turtle Mountain has finally fulfilled the Way! Today Turtle Mountain has finally fulfilled the Way!”

Dogen said:

Today Turtle Mountain has finally fulfilled the Way.

One demon died, another demon (appears).

After the two friends parted, Quanhou went to teach on Cliff Top (Yantou) Mountain in Ezhou (Hubei).

Yicun made his way back to his native region of Fuzhou where he continued his practice in a solitary hermitage on Lotus Mountain. As his reputation grew, and he began to attract the attention of local officials, he was made abbot of a new monastery beneath Snow Peak (Xeufeng) on Elephant Bone Mountain. This became his main teaching site, and was soon to grow into one of the largest training centers in the region.

Once Master Xuefeng Yicun asked a newly arrived monk, “Where are you from?”

The monk said, “From Spirit Light Monastery.”

Xuefeng said, “In the daytime we have sunlight, in the evening we have lamplight. What is ‘spirit light’?”

The monk didn’t answer.

Xuefeng said, “Sunlight, lamplight.”

One day a monk asked Master Xuefeng, “When you visited your masters, what was it that you attained that put an end to your search?”

Xuefeng said, “I went with empty hands and I returned with empty hands.”

Once a monk brought up a teaching of Master Dongshan: when the master had been asked which of the three bodies of the Buddha did not fall into the myriad things, he had replied, “I am always intimate with this.” The monk asked Master Xuefeng the meaning.

Xuefeng hit the monk. Then he said, “I have also been to Cave Mountain” (Dongshan).

One day a monk asked Master Xuefeng, “When one's understanding turns around, what's it like?”

The master said, “The boat monk fell in the river.”

Once a monk coming to question Master Xuefeng began to say, “The ancients had a saying...”

The master immediately lay down. After a while he got up and asked, “What were you saying?”

As the monk started to repeat the question, the master said, “Wasting your life; drowning in the waves.”

Once Xuefeng asked a monk, “Where are you going?”

The monk replied, “I’m going to do community work.”

The master said, “Go.”

Master Hongzhi comments:

Don’t move. If you move I’ll give you thirty blows.

Why is this so? For a luminous jewel without flaw,

if you carve a pattern, its virtue is lost.Dogen said:

For a luminous jewel without flaw, if polished its glow increases.

One day Master Xuefeng asked a newly arrived monk, “Where did you come from?”

The monk replied, “From across the mountains.”

The master asked, “Have you met Bodhidharma?”

The monk said, “Blue sky, bright sun.”

The master asked, “How about yourself.”

The monk said, “What more do you want?”

The master hit him.

Master Xuefeng asked another monk, “Where did you come from?”

The monk replied, “From Jiangxi.”

The master asked, “How far is Jiangxi from here?”

The monk said, “Not far.”

The master held up his whisk and said, “Is there any space for this?”

The monk said, “If there were space for that, then Jiangxi would be far away.”

The master hit him.

Once a monk asked Master Xuefeng, “How is it when the arrow is about to leave the bow?”

The master said, “When the archer is an expert, he doesn’t try to hit the target.”

The monk asked, “If all people don’t aim for the target, what will happen?”

The master said, “You’re an expert only according to your talent.”

Once a monk left Snow Peak and went to visit Master Lingyun Zhiqin, a disciple of Master Guishan, who taught in the same region of Fuzhou. The monk asked Master Lingyun, “Before the Awakened One was born, what was he?”

Lingyun lifted his whisk.

The monk asked, “What was he after he was born?”

Lingyun again lifted his whisk.

The monk then returned to Master Xuefeng on Snow Peak.

Master Xuefeng said, “You just left and you’re already back. Isn’t this too soon?”

The monk said, “Master Lingyun’s answers didn’t satisfy me.”

When the master inquired, the monk told the story. Then Master Xuefeng said, “Put the question to me.”

The monk asked, “Before the Awakened One was born, what was he?”

The master lifted his whisk.

The monk asked, “What was he after he was born?”

The master put down his whisk.

The monk bowed.

The master hit him.

One day a monk pleaded, “Master, please express what I cannot express myself.”

The Master Xuefeng said, “For the sake of the teaching, I have to save you!” Then he lifted his whisk and shook it before the monk.

Another time a monk asked Master Xuefeng, “What do you think of the idea that lifting up a fly whisk is not teaching Zen?”

The master lifted up his whisk.

On the edge of Snow Peak a monk built a hermitage and practiced there alone for several years, living simply and no longer shaving his head. He carved out a wooden ladle which he used to scoop up drinking water from the nearby stream.

One day while he was scooping up water, a monk from the monastery came by and asked him, “What is the meaning of Bodhidharma coming from India?”

The hermit said, “As the stream bed is deep, the ladle handle is long.”

The monk returned and told this to Master Xuefeng.

The master said, “This is rare and wondrous. Nevertheless, this old monk should go and check him out to be sure.”

The next day Master Xuefeng went to visit the hermit, accompanied by an attendant who carried a razor. When they found the hermit, the master said to him, “If you can say something, I won’t shave your head.”

The hermit thereupon washed his hair in the stream. Master Xuefeng then shaved his head.

Once Master Sansheng Huiran came to visit. He asked Master Xuefeng, “What does a golden-scaled fish that passes though the net eat?”

Xuefeng said, “I”ll tell you when you come out of the net.”

Sansheng said, “The teacher of hundreds of monks and you can’t say a turning word!”

Xuefeng said, “This old monk is busy with abbot’s affairs.”

Another time the two masters took a walk in the woods and saw a band of monkeys. Master Xuefeng said, “Each of these monkeys carries an ancient mirror.”

Master Sansheng said, “The vast eon has no name. How come you bring out ancient mirrors?”

Xuefeng said, “Now it has a scratch.”

Sansheng said, “Hundreds of practitioners can’t understand your talk.”

Xuefeng said, “This old monk is busy with abbot’s affairs.”

Once when Master Xuefeng and a group of students were walking to the local village to do some work, they encountered a band of monkeys on the road. The master said, “Each of these monkeys carries an ancient mirror, but they come to break off the tops of my rice plants!”

Once in a talk in the monk’s hall, Master Xuefeng said, “If the world is ten feet wide, then the ancient mirror is ten feet wide. If the world is one foot wide then the ancient mirror is one foot wide.”

His disciple Shibei then pointed to fireplace and said, “Then how wide is the fireplace?”

The master said, “As wide as the ancient mirror.”

One day Master Xuefeng ascended the hall and addressed the community saying, “On South Mountain there is a turtle-nosed (poisonous) snake. All of you here should take a careful look at it.”

The monk Wenyan then came forward, threw down a staff in front of the master, and mocked a gesture of fright.

The monk Huileng came forward and said, “Today in the hall there are many who are losing their bodies and lives.”

Later when Master Xuansha Shibei heard about it, he said, “Why do you need South Mountain?”

Master Xuefeng attracted the attention of the highest official of the surrounding province of Min, Wei Chubin, and eventually his reputation even reached the imperial court, who bestowed official honors on the master. In the waning years of the Tang Dynasty, as the central government became weaker, a military leader named Wang Chao assumed control of the Min region, and it became an essentially independent kingdom. Wang Chao was an avid supporter of Buddhism, and specifically promoted Master Xuefeng's teaching. When Wang passed away he was succeeded by his brother, Wang Shenzhi, who became a personal student of the master and assured the master's prominence.

As monks fled the political turmoil in the north of China, many gathered in the hospitable kingdom of Min, and began to share teaching stories of the Zen tradition. The first written compilation of such stories, the Ancestor's Hall Collection, originated in this region not long after Master Xuefeng's illustrious career, and the dominance of his reputation is clearly preserved. Both the author of this first collection, as well as the author of the even more influential later compilation, the Jingde Era Transmission of the Lamp, were descendants of Master Xuefeng, and the teaching dialogues of the master and his immediate disciples dominate the latter parts of these records.

Outstanding masters in the Lineage of Shih-t'ou: Hsüeh-feng

by John C. H. Wu

In: The Golden Age of Zen

Taipei : The National War College in co-operation with The Committee on the Compilation of the Chinese Library, 1967, pp. 155-158.

Hsüeh-feng's mind did not work as quickly as Yen-t'ou; but by virtue of his utter sincerity, humility, patience and selflessness, he became one of the greatest teachers in the whole history of Zen. His great quality, so rare among Zen masters, was that he was willing to allow others to say the last word and to express his whole-hearted approval and delight when it was said by another. If Yen-t'ou had a more brilliant mind, Hsüeh-feng had a greater soul. Like the patient hen, he hatched out many a brilliant disciple, including Yün-men and Hsüan-sha the spiritual grandfather of Fa-yen. Thus, two important Houses of Zen were descended from Hsüeh-feng, while Yen-t'ou did not have much of a progeny.

However, it cannot be denied that while both Hsüeh-feng and Yen-t'ou were disciples of Te-shan, the former treated the latter as his elder brother and came to his ultimate enlightenment through his help. Once, Hsüeh-feng was traveling with Yent'ou. When they arrived at the county of Ao-shan in Hunan, they were caught in a snowstorm and could not proceed. Yen-t'ou took it easy and slept away his days, while Hsüeh-feng spent his days in sitting and meditating. One day, he tried to rouse Yent'ou from sleep by shouting, “Elder brother, get up!” Yen-t'ou answered, “Why should I?” Hsüeh-feng was vexed and murmured, “In this present life why am I so unlucky to be traveling with a fellow like this, who just drags me down like a piece of luggage. And since we have arrived here, he has been doing nothing but sleeping!” Yent'ou shouted at him, saying, “Shut up and go to sleep! Every day you sit cross-legged on the bed. How like an idol in the soil-shrine of a common village! In the future you will be bedeviling the sons and daughters of good families!” Hsüeh-feng, pointing to his own breast, said, “Here within me I feel no peace. I dare not deceive myself.” Yen-t'ou said that he was very much surprised to hear him speak like this. Hsüeh-feng repeated again that he really felt an inner restlessness. Then Yent'ou asked him to relate to him his perceptions and experiences and promised to sift the genuine from the spurious. Hsüeh-feng told him how he had got an entrance into Zen at the feet of the master Hsien-kuan, how he was inspired by reading the gatha that Tung-shan had composed after his enlightenment, and finally how he asked Te-shan about the Vehicle beyond all vehicles, how Te-shan responded to his question by striking him with his rod, saying, “What are you talking about?” and, how he felt at that moment like a tub whose bottom had fallen out. At this, Yent'ou shouted, saying, “Haven't you heard that he who enters by the door is not the treasure of his own house?” Hsüeh-feng asked, “From now on what shall I do?” Yen-t'ou said, “Hereafter, if you want to spread broadcast the great teaching, let everything flow from your own bosom and let it cover and permeate the sky and the earth!” At these words, Hsüeh-feng was thoroughly awakened. After he had done his obeisance, he rose and cried ecstatically, “Elder brother! Today at Ao-shan I have truly attained the Tao!”

Hsüeh-feng later became an abbot, with a community of fifteen hundred monks under him. Once a monk asked him what he had learned from Te-shan. He replied, “I went to him emptyhanded and empty-handed I returned.” The truth is, as he pointed out, that “no one really gets anything from his master.” This reveals that Hsüeh-feng was as transcendental in his outlook as any of the great masters. On the other hand, his duties as a teacher of so many monks compelled him to accommodate himself to their needs. He had to keep the sword in the scabbard. When someone asked him “What happens if the arrow reveals its sharp head?” he said, “The brilliant archer misses his aim.” Thus, it seems that he

had taken seriously to heart the Taoist lesson of toning down the dazzling splendor of one's light. However, he knew as well as anybody that attachment to one particular method would blind the eyes of a beginner. Once a novice besought him to point out to him a definite entrance into Zen. He replied, “I would rather have my body pulverized into dust than run the risk of blinding the eyes of a single monk!”Hsüeh-feng was quick to recognize the superior qualities of another. He admitted his inferiority to the master Huang Nip'an, saying, “I live within the three worlds: you are beyond the three worlds.” He called Kuei-shan the “ancient Buddha of Kuei-shan,” and Chao-chou the “ancient Buddha of Chao-chou.” When the master San-sheng asked him, “When the golden-scaled fish had gone through the net, what food does it feed on?” Hsüeh-feng replied, after the style of old masters, “I will tell you after you have come out from the net.” San-sheng remarked, “How strange it is that the guardian of fifteen hundred men does not even recognize the point of a question!” Hsüeh-feng apologized, “This old monk is too preoccupied with his duties as an abbot.” On another occasion, as both Hsüeh-feng and San-sheng were participating in the regular manual work of the community in the field, they saw a monkey. Hsüeh-feng remarked, “Everyone has an antique mirror in him; so does this monkey.” San-sheng said, “How can the eternally nameless manifest itself as an antique mirror?” Hsüeh-feng answered, “Because flaws have grown on it.” San-sheng again charged him with not understanding the meaning of words. Hsüeh-feng again apologized for his preoccupation with his duties.

Obviously, Hsüeh-feng knew his rubrics as well as San-sheng; but when he was speaking of the “antique mirror” and the flaws gathering on it, it was for the ears of the beginners. That he knew what he was doing is clear from another incident. Once he asked a visiting monk where he came from, to which the latter answered, “From the master Fu-ch'uan.” Now “Fu-ch'uan” meant “sunken boat.” So Hsüeh-feng made a pun of his name, saying, “There is still much to do in ferrying over the sea of birth and death, why should he sink the boat so soon?” The monk, knowing not what to say, returned to report to Fu-ch'uan, who remarked, “Why didn't you answer that that one is beyond birth and death?” The monk came back to Hsüeh-feng and spoke as taught. Hsüeh-feng said, “These words are not yours.” The monk admitted that it was Fu-ch'uan who had taught him to say so. Hsüeh-feng said, “I have twenty blows of the rod for you to bring to Fu-ch'uan, reserving twenty blows for myself. This has nothing to do with you.”

Fu-ch'uan erred by leaning to the transcendent, while Hsüeh-feng erred by leaning to the immanent. But did Lao Tzu not say, “Know the bright, but cling to the dark?” Hsüeh-feng knew the other shore, but kept to this shore. Oh the trials and agonies of a teacher!

HSUEH-FENG

Translated by Thomas Cleary

In: The five houses of Zen, 1997

Hsueh-feng (822–908) was the teacher of Yun-men and of many other distinguished Zen masters of the age. Hsueh-feng attained his first Zen realization at the age of eighteen, but he did not reach complete Zen enlightenment until he was forty-five and is traditionally held up as a prime illustration of the proverb, “A good vessel takes a long time to complete.” He subsequently attracted many followers and is said to have had fifteen hundred disciples. By the time he died, he had more than fifty enlightened successors already teaching Zen.

Sayings

THE WHOLE UNIVERSE, the whole world, is you; do you think there is any other? This is why the Heroic Progress Scripture says, “People lose themselves, pursuing things; if they could turn things around, they would be the same as Buddha.”

You must perceive your essential nature before you attain enlightenment. What is perceiving essential nature? It means perceiving your own original nature.

What is its form? When you perceive your own original nature, there is no concrete object to see.

This is hard to believe in, but all buddhas achieve it.

Terms for the one mind are buddha nature, true suchness, the hidden essence, the pure spiritual body, the pedestal of awareness, the true soul, the innocent, universal mirrorlike cognition, the empty source, the ultimate truth, and pure consciousness.

The buddhas of past, present, and future, and all of their scriptural discourses, are all in your original nature, inherently complete. You do not need to seek, but you must save yourself. No one can do it for you.

Look, look at these grown-ups traveling to the ends of the earth! Wherever you go, when someone asks you what the matter is, you immediately say hello, say good-bye, raise your eyebrows, roll your eyes, step forward, and withdraw. Broadcasting this sort of bad breath, the minute you get started you enter a wild fox cave. Taking the servant for the master, you do not know pollution from purity. Deceiving yourselves in the present, at the end of your lives you will turn out to be nothing more than a bunch of wild foxes.

Do you understand? How does this produce good people? Having received the shelter of Shakyamuni Buddha, you destroy his sacred heritage. What kind of attitude is this? All over China, Buddhism is dying out right before our eyes. Don’t think this is an idle matter! As I sit here, I do not see a single individual who qualifies as an initiate in the Zen message of time immemorial. You are just a random collection, a gang ruining Buddhism. The ancients would call you people who repudiate wisdom. You will have to reject this before you can attain realization.

To attain this matter requires strength of character; don’t keep on running to me over and over again, depending on me, seeking statements and asking for sayings. For a man of the required character, that is making fools of people. Do you know good from bad? I’ll have to chase this bunch of ignoramuses away with my cane!

If you immediately realize being-so, that is best and most economical; don’t let yourself come to me for a statement. Understand? If you are a descendant of the founder of Zen, you will not eat food that another has already chewed.

What is more, you should not cramp yourself. Right now, what do you lack? The business of the responsible individual has been as clear as the bright sun in the blue sky for all time. There has never been anything at all obstructing it; so why don’t you know it?

If I were to tell you that in order to understand you would have to take half a step, to exercise the slightest bit of effort, to read a single word of scripture, or to explicitly ask questions of others, I would be deceiving and threatening you.

What is this right here and now?

Unable to get it, and also unable to step back into yourself and examine thoroughly to see for yourself, you only know to go to ignorant and muddle-headed “old teachers” to memorize sayings. What relevance is there? Do you know this is not something verbal? I tell you, if you memorize a single phrase of a saying, you’ll be a wild fox sprite for all time. Do you understand?

XUEFENG YICUN

IN: Zen's Chinese heritage: the masters and their teachings

by Andy Ferguson

Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2000. pp. 261-265.

XUEFENG YICUN (822–908) was a disciple of Deshan Xuanjian. He came from the city of Nanan in ancient Quanzhou (a place in modern Fujian Province). It’s recorded that as a toddler Xuefeng refused to eat nonvegetarian food. One day, while being carried on his mother’s back, a funeral spectacle of flags and flowers appeared. This caused a profound change in the child’s countenance. At the age of twelve he left home to live at Yujian Temple in Putian City. Later he traveled widely, eventually coming to Baocha Temple in ancient Youzhou (modern Beijing), where he was ordained. Later, he went on to Wuling (near the modern city of Changde in Hunan Province), where he studied under the great teacher Deshan, eventually becoming his Dharma heir. However, Xuefeng’s most profound realization occurred with his Dharma brother, Yantou, while they were traveling and staying at a mountain inn during a snowstorm. In the year 865, Xuefeng moved to Snow Peak on Elephant Bone Mountain in Fuzhou, where he established the Guangfu Monastery and obtained his mountain name. The monastery flourished, the congregation’s size reaching up to fifteen hundred monks.

True to the spirit of Zen, Xuefeng’s teaching did not rely on words or ideas. Instead, he emphasized self-realization and experience. The Yunmen and Fayan Zen schools, two of the traditionally recognized five houses of Zen, evolved from Xuefeng’s students.

Illustration by 李蕭錕 Li Xiaokun (1949-)Xuefeng served as a rice cook at Dong Shan.

One day as he was straining the rice, Dongshan asked him, “Do you strain the rice out from the sand, or do you strain the sand out from the rice?”

Xuefeng said “Sand and rice are both strained out at once.”

Dongshan said, “In that case, what will the monks eat?”

Xuefeng then tipped over the rice pot.

Dongshan said, “Go! Your affinity accords with Deshan!”

When Xuefeng left Dongshan, Dongshan asked him, “Where are you going?”

Xuefeng said, “I’m returning to Lingzhong [Fuzhou].”

Dongshan said, “When you left Lingzhong to come here, what road did you take?”

Xuefeng said, “I took the road through the Flying Ape Mountains.”

Dongshan said, “And what road are you taking to go back there?”

Xuefeng said, “I’m returning through the Flying Ape Mountains as well.”

Dongshan said, “There’s someone who doesn’t take the road through Flying Ape Mountains. Do you know him?”

Xuefeng said, “I don’t know him.”

Dongshan said, “Why don’t you know him?”

Xuefeng said, “Because he doesn’t have a face.”

Dongshan said, “If you don’t know him, how do you know he doesn’t have a face?”

Xuefeng was silent.

When Xuefeng was traveling with Yantou on Tortoise Mountain in Li Province, they were temporarily stuck in an inn during a snowstorm. Each day, Yantou spent the entire day sleeping. Xuefeng spent each day sitting in Zen meditation.

One day, Xuefeng called out, “Elder Brother! Elder Brother! Get up.”

Yantou said, “What is it?”

Xuefeng said, “Don’t be idle. Monks on pilgrimage have profound knowledge as their companion. This companion must accompany us at all times. But here today, all you are doing is sleeping.”

Yantou yelled back, “Just eat your fill and sleep! Sitting there in meditation all the time is like being some clay figure in a villager’s hut. In the future you’ll just spook the men and women of the village.”

Xuefeng pointed to his own chest and said, “I feel unease here. I don’t dare cheat myself [by not practicing diligently].”

Yantou said, “I always say that some day you’ll build a cottage on a lonely mountain peak and expound a great teaching. Yet you still talk like this!”

Xuefeng said, “I’m truly anxious.”

Yantou said, “If that’s really so, then reveal your understanding, and where it is correct I’ll confirm it for you. Where it’s incorrect I’ll root it out.”

Xuefeng said, “When I first went to Yanguan’s place, I heard him expound on emptiness and form. At that time I found an entrance.”

Yantou said, “For the next thirty years, don’t speak of this matter again.”

Xuefeng said, “And then I saw Dongshan’s poem that said, ‘Avoid seeking elsewhere, for that’s far from the Self, now I travel alone, everywhere I meet it, now it’s exactly me, now I’m not it.’”

Yantou said, “If that’s so, you’ll never save yourself.”

Xuefeng then said, “Later I asked Deshan, ‘Can a student understand the essence of the ancient teachings?’ He struck me and said, ‘What did you say?’ At that moment it was like the bottom falling out of a bucket of water.”

Yantou said, “Haven’t you heard it said that ‘what comes in through the front gate isn’t the family jewels’?”

Xuefeng said, “Then, in the future, what should I do?”

Yantou said, “In the future, if you want to expound a great teaching, then it must flow forth from your own breast. In the future your teaching and mine will cover heaven and earth.”

When Xuefeng heard this he experienced unsurpassed enlightenment. He then bowed and said, “Elder Brother, at last today on Tortoise Mountain I’ve attained the Way!”

After Xuefeng assumed the abbacy at Snow Peak, a monk asked him, “When the master was at Deshan’s place, what was it you attained that allowed you to stop looking further?”

Xuefeng said, “I went with empty hands and returned with empty hands.”

A monk asked Xuefeng, “Is the teaching of the ancestors the same as the scriptural teaching or not?”

Xuefeng said, “The thunder sounds and the earth shakes. Inside the room nothing is heard.”

Xuefeng also said, “Why do you go on pilgrimage?”

One day, Xuefeng went into the monks’ hall and started a fire. Then he closed and locked the front and back doors and yelled “Fire! Fire!”

Xuansha took a piece of firewood and threw it in through the window. Xuefeng then opened the door.

Xuefeng asked a monk, “Where have you come from?”

The monk said, “From Zen master Fuchuan’s place.”126

Xuefeng said, “You haven’t crossed the sea of life and death yet. So why have you overturned the boat?”

The monk was speechless. He later returned and told Zen master Fuchuan about this.

Fuchuan said, “Why didn’t you say, ‘It is not subject to life and death’?”

The monk returned to Xuefeng and repeated this phrase.

Xuefeng said, “This isn’t something you said yourself.”

The monk said, “Zen master Fuchuan said this.”

Xuefeng said, “I send twenty blows to Fuchuan and give twenty blows to myself as well for interfering in your own affairs.”

A monk asked, “What is it if my fundamentally correct eye sometimes goes astray because of my teacher?”

Xuefeng said, “You haven’t really met Bodhidharma.”

The monk said, “Where is my eye?”

Xuefeng said, “You won’t get it from your teacher.”

A monk asked Xuefeng, “All the ancient masters each said they all penetrated the meaning of the phrase, ‘In the threefold body of Buddha there is one which does not falter.’ What is the meaning of this?”

Xuefeng said, “This fellow has climbed Mt. Dong nine times.”

When the monk started to ask another question Xuefeng said, “Drag this monk out of here!”

A monk asked, “What is it when one is solitary and independent?”

Xuefeng said, “Still sick.”

A monk asked, “When one pivots, then what?”

Xuefeng said, “The Boat Monk fell in the river.”

A monk asked, “What are the words passed down by the ancients?”

Xuefeng lay down.

After a long time he got up and said, “What was your question?”

The monk asked again.

Xuefeng said, “An empty birth, a fellow drowned in the waves.”

A monk asked, “The ancients said that if you meet Bodhidharma on the road, speak to him without words. I’d like to know how one speaks this way?”

Xuefeng said, “Drink some tea.”

Zen master Xuefeng entered the hall and addressed the monks, saying “South Mountain has a turtle-nosed snake. All of you here must take a good look at it.”

Changqing came forward and said, “Today in the hall there are many who are losing their bodies and lives.”

Yunmen then threw a staff onto the ground in front of Xuefeng and affected a pose of being frightened.

A monk told Xuansha about this and Xuansha said, “Granted that Changqing understands, still I don’t agree.”

The monk said, “What do you say, Master?”

Xuansha said, “Why do you need South Mountain?”

Xuefeng asked a monk, “Where are you from?”

The monk said, “From Shenguang [‘spirit light’].”

Xuefeng asked, “During the day it’s called daylight. At night it’s called firelight. What is it that’s called spirit light?

The monk didn’t answer.

Speaking for the monk, Xuefeng said, “Daylight. Firelight.”

Xuefeng’s Dharma seat never had less than fifteen hundred monks living there. In the third month of [the year 908] Xuefeng became ill. The governor of Fuzhou sent a doctor to cure him, but Xuefeng said, “I’m not ill. There’s no need for medicine.” Xuefeng then composed a poem to convey the Dharma. On the second day of the fifth month, he went for a walk in the fields in the morning. In the evening he returned and bathed. He passed away during the night.

After Xuefeng’s death, the emperor Tang Xi Zong bestowed upon him the posthumous title “Great Teacher True Awakening.”

Xuefeng Receives his Student Xuansha 雪峰接玄沙生圖

Attributed to Muxi Fachang 牧谿法常 (13th century) Late 13th century, Yuan (1271-1368)

Encomium by Yuji Zhihui 愚極智慧 (act. 1298) Hanging scroll, ink on silk, 102 x 46 cm Kyoto National Museum, AK672 Important Cultural Property

Encomium:

Xuan Sha's teachings have no special rationale,

You pay obeisance to me, prostrating yourself and getting up,

As I pay obeisance to you.

[Signed] Jingci Foxin Zhihu. 玄沙宗旨, 別無道理, 你為禮拝, 自倒自起, 因我得禮你。 淨慈佛心,智慧。

Hszüe-feng Ji-cun összegyűjtött mondásaiból

Fordította: Terebess Gábor

Vö.: Folyik a híd, Officina Nova, Budapest, 1990, 98-101. oldal

Hszüe-feng a gyülekezet elé lépett, felemelte a légycsapóját, és azt mondta:

– Ezt csak a gyengébbek kedvéért teszem.

Egy szerzetes megkérdezte:

– És a kiválóbbakért mit teszel?

A mester újra felemelte a légycsapóját.

– De hisz ezt a gyengébbek kedvéért tetted! – figyelmeztette a szerzetes.

A mester lecsapott rá.– Hogy láthatom meg a csant? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

– Inkább ízzé-porrá töretem magam, semmint elvakítsak egy szerzetest – mondta Hszüe-feng.Hszi-san Csang a legjobb favágó volt Touce-sanban.

Amikor Hszüe-fenghez került, a mester megkérdezte tőle:

– Te vagy Csang, a híres favágó?

Csang meglendítette a karját, mintha éppen fát vágna.

Hszüe-feng bólintott.Ven-szuj [Csin-san Ven-szuj, ?-841?] , Hszüe-feng és Jen-tou [Jen-tou Csüan-huo, 828-887] együtt üldögéltek.

Ven-szuj rámutatott egy csésze vízre, és így szólt:

– A hold megjelenik a tiszta vízben.

– A hold nem jelenik meg a tiszta vízben – mondott ellent Hszüe-feng.

Jen-tou felrúgta a csészét.Hszüe-feng kint dolgozott a mezőn tanítványaival. Észrevett egy kígyót, és felkapta a botjával:

– Ide nézzetek! – kiáltott oda a szerzeteseknek, hadd lássák, amint kettévágja késével.

Hszüan-sa ott termett, felszedte a döglött kígyó két felét, és messzire maguk mögé hajította. Aztán visszament dolgozni, mintha mi se történt volna.

Mindenki megrökönyödött.

– Milyen fürge vagy! – jegyezte meg Hszüe-feng.

Réber László (1920-2001) rajza