ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

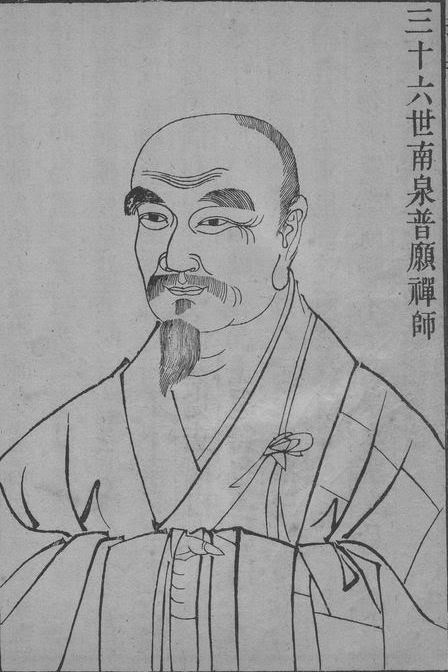

南泉普願 Nanquan Puyuan (王老師 Wang laoshi) (748-835)

南泉普願禪師語要 Nanquan Puyuan chanshi yuyao; 南泉語要 Nanquan yuyao

(Rōmaji:) Nansen Fugen (Ō rōshi): Nansen Fugen zenji goyō

(English:) Essential sayings of Chan Master Nanquan Puyuan

(Magyar:) Nan-csüan Pu-jüan (Vang mester) mondásai

Chizhou Nanquan Puyuan Chanshi yuyao 池州南泉普願禪師語要 (Essential words of Chan Master Nanquan Puyuan of Chizhou), 1 fascicle (x 68: #1315). Also known as Chizhou Nanquan Puyuan heshang yuyao 池州南泉 普願和尚語要. The collected sermons and instructions of the Chan master Nanquan Puyuan 南泉普願 (748–835), an eminent heir of Mazu Daoyi 馬 祖道一 (709–788) and teacher of Zhaozhou Congshen 趙州從諗 (778–897). Published in the Shaoxing era 紹興 (1131–1162), with a postscript by Yuanwu Keqin 圜悟克勤 (1063–1135).

Tartalom |

Contents |

| Nan-csüan Pu-jüan mondásaiból Fordította: Terebess Gábor |

Encounter Dialogues of Nanquan Puyuan PDF: Killing Cats and Other Imaginary Happenings: Milieus and Features of Chan Exegesis |

Nan-csüan Pu-jüan (Vang mester) összegyűjtött mondásaiból

Fordította: Terebess Gábor

Vö.: Folyik a híd, Officina Nova, Budapest, 1990, 29-40. oldal

Nan-csüan csan mester Csengcsouban született. Eredeti családneve Vang volt, ezért emlegette magát gyakran úgy, mint „az öreg Vang mester". Már kilencéves korában tarra borotválták a fejét, de csak harminc évesen tette le a teljes szerzetesi fogadalmat a Szung-hegyen. Buddhista tanulmányai a szerzetesi rendszabályoktól és Buddha tanítóbeszédeitől a szövegmagyarázatokig és filozófiai értekezésekig terjedtek. Széles ismeretei alapossággal és odaadással párosultak. Végül is „kopogtatott Ma-cu csan mester kapuján, megvilágosult és elfelejtett mindent, amit addig tanult".795-ben, 47 éves korában remetekunyhót épített magának a Nancsüan-hegyen, Csicsouban, és nem jött le a hegyről harminc évig. 828-ban Hszüancseng tartományi kormányzója, Lu Keng (764-834) hallott a mesterről, és maga is tanítványként járult elé. Ettől kezdve sereglettek köré a tanítványok.

„Leáldoznak a csillagok és elhomályosulnak a lámpafények, ne mondjátok, hogy egyedül én vagyok az, akinek jönnie és mennie kell" – szólt tanítványaihoz egy nap, 835 elején, és örökre lehunyta szemét. Nyolcvanhetedik évében járt.

Réber László illusztációja

Egyszer a három tanítvány, Nan-csüan, Hszi-tang és Paj-csang elkísérte Ma-cu mestert egy holdfényes sétára.

– Mit gondoltok – kérdezte Ma-cu –, mire lehetne legjobban kihasználni ezt az időt?

– A szövegek tanulmányozására – szólalt meg elsőnek Hszi-tang.

– Kiváló alkalom az elmélkedésre – javasolta Paj-csang.

Ilyen válaszok hallatán Nan-csüan megfordult, és faképnél hagyta őket.

– A szövegeket meghagyom Hszi-tangnak – mondotta a mester –, Paj-csang pedig valóban tehetséges elmélkedő. De Nan-csüan lépett túl a hívságokon.

Huang-po a kolostor kapujában búcsúzott Nan-csüan mestertől, a kezében tartotta bambusz esőkalapját.

– Nagy melák ember vagy, nem túl kicsi neked ez a kalap? – kérdezte Nan-csüan.

– Ha kicsi is, elfér alatta az egész világ.

– No és én, az öreg Vang mester?

Huang-po feltette kalapját és útnak indult.

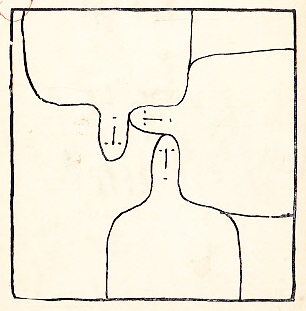

Zensho W. Kopp illusztrációja

– Milyen lelkiállapotod van a nap tizenkét órája alatt? – kérdezte egy szerzetes Nan-csüantól.

– Miért nem az öreg Vang mestert kérdezed? – tanácsolta Nan-csüan.

– Épp most kérdeztem.

– És adott valamit, ami a lelkiállapotod legyen?

– Az öreg Vang mester áruba bocsátja magát – fordult egyszer Nan-csüan a gyülekezethez. – Ki veszi meg?

– Én megveszem – lépett elő egy szerzetes.

– De ne legyek se drága, se olcsó – szabta meg a mester. – Nos, mennyit érek?

A szerzetes hallgatott.

A mester látogatóba készült a szomszéd faluba. Éjszaka a helybéli földisten megjelent a falu elöljárójának, és jelezte a mester másnapi érkezését. Elő is készítettek mindent a fogadására.

– Honnan tudtad előre, hogy jövök? – lepődött meg a mester.

– Megmondta a földisten álmomban – felelte a falusi elöljáró.

– Erőtlen az öreg Vang mester minden igyekvése, ha istenek és démonok kifürkészhetik szándékait – állapította meg Nan-csüan.

Egy szerzetes mindjárt a mester védelmére kelt:

– Tisztelendőséged máris oly nagyszerű erényekkel bír, miért fürkésznék istenek és démonok?

– Áldozz ételt a földisten oltárán! – zavarta el a szerzetest Nan-csüan.

– Mit csinálunk ma? – kérdezte a kolostor intézőjét Nan-csüan.

– Malomkereket forgatunk.

– A malomkereket forgathatod – hagyta rá Nancsüan –, csak a tengelyre vigyázz, nehogy megmozduljon.

– Mi az Út? – kérdezte Csao-csou.

– A mindennapi gondolkodás – válaszolta Nan-csüan.

– Hogyan térhetünk rá?

– Ha tudatosan akarsz rátérni, máris tévúton jársz.

– De akkor hogy tudhatok róla?

– Az Útnak nincs köze se tudáshoz, se nemtudáshoz – mondotta Nan-csüan. – A tudás káprázat, a nemtudás zűrzavar. Ha valóban tudatosság nélkül éred el az Utat, mintha mérhetetlen ürességbe jutnál, nem lesz előtted se akadály, se határ. Hogy lehetne akkor állítani vagy tagadni?

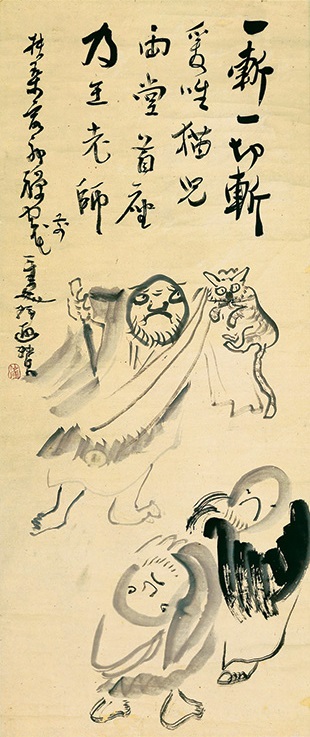

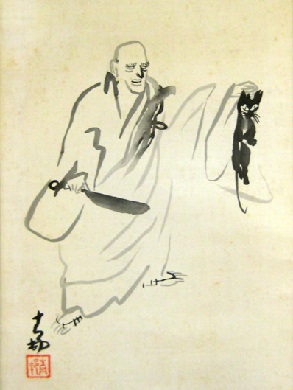

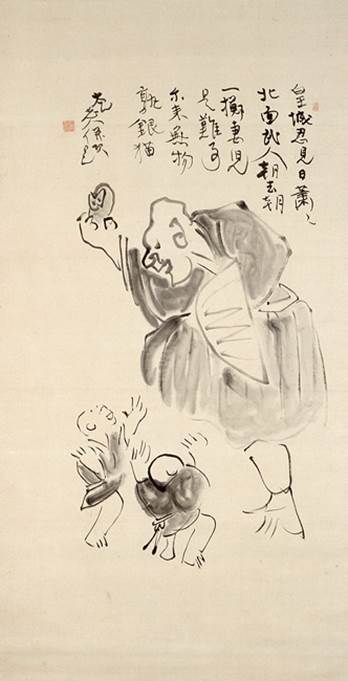

仙厓義梵

Sengai Gibon (1750-1837) tusfestménye

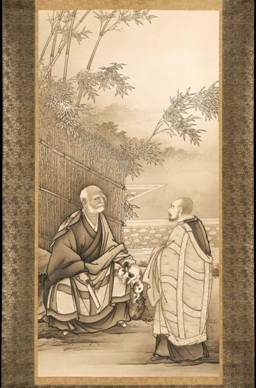

長谷川等伯 Hasegawa Tōhaku (1539-1610)

曾我蕭白

Soga Shōhaku (1730–1781) --- 橋本雅邦 Hashimoto Gahō (1835–1908)

--- 前田青邨 Maeda Seison (1885-1977)

---

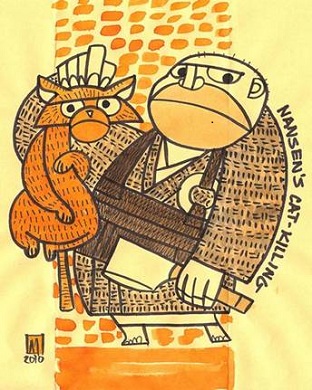

Mark T. Morse (1973-) illusztrációi

Az illusztráció tapéta-vágat. Art Deco Cats in Gold: Wallpaper design by pinkowlet (Dana Duncan, Pasadena)

Réber László illusztációja

Tarnóczy Zoltán illusztációja

Egyszer a Nyugati és a Keleti Csarnok szerzetesei veszekedtek egy kismacskán. Nan-csüan mester felvette a macskát és elibük tartotta:

– Szóljatok érte egy szót, vagy megölöm!

A szerzetesek zavartan hallgattak, mire Nan-csüan kettévágta a macskát.

Estefelé megérkezett Csao-csou, és Nan-csüan elmesélte neki, mi történt. Csao-csou levette egyik szalmabocskorát, a feje tetejére rakta és indult kifelé.

– Ha itt lettél volna – sóhajtott Nan-csüan –, megmented azt a macskát.

Nan-csüan ruhát mosott.

– A mester még mindig ezt csinálja? – hüledezett egy szerzetes.

– Miért, mit csináljak vele? – emelte fel a ruhát Nan-csüan.

Egy szerzetes a csészéjét mosogatta. Nan-csüan mellé lépett és váratlanul kitépte a kezéből. A szerzetes megütközve állt ott, üres kézzel.

– Most a csésze az én kezemben van – szögezte le Nan-csüan. – Mit érsz vele, ha méltatlankodsz?

Egyszer Nan-csüan kisétált a veteményeskertbe, látott egy szorgoskodó szerzetest, és megdobta egy darab téglával. Amint a szerzetes hátranézett, a mester felemelte az egyik lábát. A szerzetes nem szólt semmit, de követte a mestert a csarnokba.

– Az imént megdobtál egy darab téglával – kezdte a kérdezősködést. – Ez valami intelem volt?

– No és a lábemelés? – kérdezte a mester.

A szerzetesnek torkán akadt a szó.

Tarnóczy Zoltán illusztációja

Egyszer Nan-csüan füvet sarlózott a mezőn. Arra járt egy vándor szerzetes, és azt kérdezte tőle, melyik út vezet a Nan-csüan kolostorba.

Nan-csüan fölegyenesedett, és odatartotta sarlóját a szerzetes orra alá:

– Harminc pénzt fizettem érte – mondta.

– De én a Nan-csüanba vezető útról kérdeztelek!

– Bizony jól vág! – mondta Nan-csüan.

Tarnóczy Zoltán illusztációja

Nan-csüan remetelakába betévedt egy szerzetes.

– Felmegyek a hegyre dolgozni – mondta Nan-csüan –, főzd csak meg az ebédet, egyél, aztán hozd fel a részem.

A szerzetes megebédelt, széttört-zúzott mindent a remetelakban, és lefeküdt aludni.

Nan-csüan megelégelte a várakozást és hazaindult. Amikor meglátta az alvó szerzetest, szó nélkül leheveredett az ágy túloldalára, és ő maga is elaludt. A szerzetes felkelt és otthagyta.

Nan-csüan évek múltán is emlékezett az esetre:

– Azelőtt egy remetelakban éltem – mesélte tanítványainak –, és egyszer meglátogatott egy agyafúrt szerzetes. Színét se láttam többé.

Lacza Márta illusztációja

Lu Keng [vagy Lu Hszüan kormányzó, 764-834], Hszüancseng kormányzója tanácsot kért Nan-csüantól:

– Egy kő lakik a házamban, és mást se tesz, csak ül vagy fekszik. Lehet Buddhát faragni belőle?

– Lehet.

– Tényleg nem lehetetlen?

– Most már az – mondta a mester. – Lehetetlen.

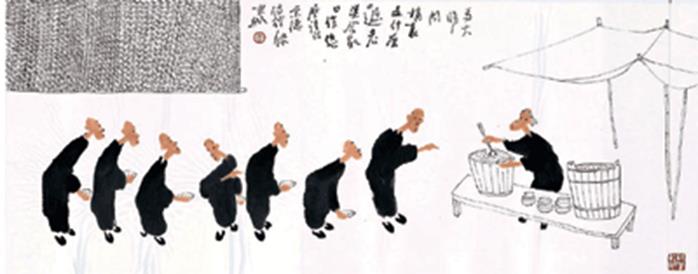

李蕭錕 Li Xiaokun (1949-) illusztrációja

– Csao, a Törvény tanítója szerint az Ég, a Föld és mi magunk egyazon gyökérből eredünk. Nemde különös? – tűnődött Lu Keng kormányzó.

Nan-csüan a bazsarózsákra mutatott a kertben és azt mondta neki:

– Mostanában az emberek mintha csak álmukban látnák ezeket a rózsákat.

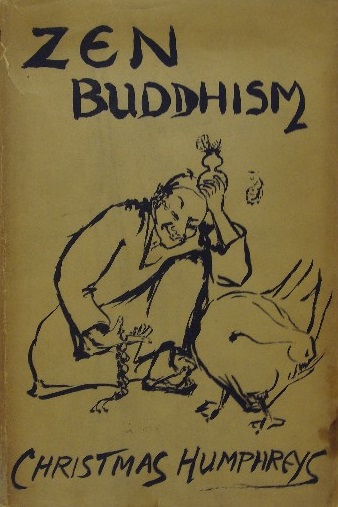

Hasuko (Mrs. Christmas Humphreys) rajza (1949)

Tarnóczy Zoltán illusztációja (1973)

Pápai Gábor rajza (1994)

Pierre Székely Péter (1923-2001) illusztációja

Terebess Pál: AI-generált kép (2023)

Egy napon Lu Keng kormányzó a következő történetet mesélte Nan-csüannak:

– Egyszer egy ember a fejébe vette, hogy palackban fog libát nevelni. Telt az idő, és a liba akkorára nőtt, hogy nem fért ki többé a palack száján. Az ember nem akarta, hogy a libának bántódása essék, de a palackot is sajnálta széttörni. Mit tennél a helyében, mester?

– Kormányzó! – szólította őt Nan-csüan.

– Tessék.

– Kinn van!

Lu kormányzó búcsúzkodott, hazakészült hszüancsengi hivatalába.

– Kormányzó! – állította meg Nan-csüan. – Hogyan kormányzod a népet, ha visszatérsz a székvárosba – Bölcsességgel.

– Ha ez igaz – sóhajtott a mester –, megkeserüli a nép.

– Hol van az orrlyukunk, mielőtt megszületünk? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

– Hol van az orrlyukunk, miután megszülettünk? – kérdezett vissza Nan-csüan.

Ma-ku [Ma-jü Pao-csö, 720?-?] meglátogatta Csang-csinget [Csang-csing Huaj-jün, 756-815]. Háromszor körbejárta a székén ülő mestert, egyszer figyelmeztetőn megcsörgette karikás koldusbotját, aztán megállt előtte és kihúzta magát.

– Igazad van – mondta Csang-csing.

Ma-ku meglátogatta Nan-csüant. Háromszor körbejárta a székén ülő mestert, egyszer figyelmeztetőn megcsörgette karikás koldusbotját, aztán megállt előtte és kihúzta magát.

– Nincs igazad – mondta Nan-csüan.

– Csang-csing azt mondta, hogy igazam van – berzenkedett Ma-ku –, te miért mondod azt, hogy nincsen?

– Csang-csingnek igaza is volt, neked nincs igazad!

Réber László illusztációja

A mester halála közeledtén, a szerzetesfelügyelő megkérdezte tőle:

– Hová mégy a halál után?

– Lemegyek a hegyről vízibivalynak – felelte Nan-csüan.

– Oda is követhetlek?

– Ha mindenáron követni akarsz, legalább hozz egy harapás szénát magaddal.

Encounter Dialogues of Nanquan Puyuan

compiled by Satyavayu of Touching Earth Sangha

DOC: Treasury of the Forest of Ancestors

Master Nanquan Puyuan was from the city of Xinzheng in southern Henan. His family name was Wang, and later, as a master, he sometimes called himself, “Old Teacher Wang.” He was already a seasoned monk, well-versed in the various philosophies and scriptures of Buddhism, when he traveled to Hongzhou to study with Master Ma. Puyuan's insight and confidence was already apparent during his training at Mazu's monastery:

One day while Puyuan was serving rice gruel to the community, Master Ma asked, “What's in the wooden bucket?”

“The old man should keep his mouth shut and not say such words,” replied Puyuan.

Illustration by 李蕭錕 Li Xiaokun (1949-)

While practicing with Master Ma, Puyuan took some time to visit other teachers as well. Once he started out on a journey to visit the aging master Nanyang Huizhong in the capital of Chang'an, together with his fellow monks Zhichang and Baoche. Just after leaving the monastery, Puyuan stopped and drew a circle on the road. He then said to his companions, “What can you say? If you give a good response, we'll be on our way. Otherwise, maybe we shouldn't go.”

Zhichang sat down inside the circle. Baoche made a curtsy. Puyuan said, “Let's not go.”

Eventually the group did make the trip to see Master Nanyang. When Puyuan entered the master's room for an audience, the master asked him, “Where are you from?”

Puyuan said, “From Hongzhou.”

The master asked, “Do you come with the truth of Master Ma, or not?”

Puyuan said, “Just this is it.”

The master said, “But is there something behind your back?”

Puyuan immediately turned around and walked out.

Once Puyuan visited a master called “Priest Nirvana” (Niepan Heshang, probably Master Baizhang Weizheng, an older disciple of Master Ma). Priest Nirvana asked Puyuan, “Is there any teaching that hasn't already been spoken by the ancient sages?”

Puyuan said, “It's not mind, it's not Buddha, it's not a thing.”

Nirvana said, “Is that all?”

Puyuan said, “I'm like this. What about you?”

Nirvana said, “”I'm not a teacher. How should I know if there's a teaching that has or hasn't been spoken?”

Puyuan said, “I don't understand.”

Nirvana said, “I've said enough for you.

After the passing of Master Ma and a subsequent period of traveling, Puyuan entered the mountains for solitary retreat. He settled on a mountain called South Spring (Nanquan) in the area of Chizou (in modern Anhui Province). Here he built a thatched hut and remained alone for many years focusing on meditation. Eventually some monks began to visit seeking his guidance, including the monk Congshen, who would become his senior student. Finally, a prominent government official named Lu Gong came to study with Puyuan, and he invited the master to move to a local monastery and become the abbot, in order to teach more extensively. Puyuan accepted the offer.

Official Lu once requested of Master Nanquan Puyuan “I ask the master to expound the teaching for the sake of the community.”

Master Nanquan said, “What do you want this old man to talk about?”

Lu said, “Master, don't you have some expedient method for entering the Way?”

Nanquan said, “What are those in the community lacking?”

Lu said, “What will you do about those in the four modes of birth and the six realms?”

Nanquan said, “This old monk doesn't teach them.”

Once Master Nanquan addressed the community, “Master Ma was known to say, 'This very mind itself is Buddha.' Old teacher Wang doesn't talk like this. I say - it's not mind, it's not Buddha, it's not a thing. Is saying it like this a mistake or not?”

Nanquan's senior disciple Congshen made prostrations and left.

Another time Nanquan said, “Mind is not Buddha. Wisdom is not the Way.”

A monk asked, “All past ancestors, including the great teacher from Jiangxi (Mazu), have taught that 'mind is Buddha' and 'ordinary mind is the Way.' Now you, master, say that mind is not Buddha, and wisdom is not the Way. I am uncertain about this – I ask the master to compassionately offer an explanation.”

Nanquan replied in a loud voice, “If you're a buddha, how could you still have doubts and have to ask this old monk for explanations? What kind of buddha stumbles along the way, holding doubts like that? I am not a buddha, and I haven't seen the ancestors. Since it is you talking about ancestors, you can go seek them by yourself.”

The monk then asked, “Since your reverence explains it like that, what kind of practical advice can you offer a student like me?”

Nanquan said, “Just now lift empty space with your palm.”

The monk said, “Empty space has no movable form. How can I lift it?”

Nanquan siad, “When you say it has no movable form, that is already movement. Does empty space say, 'I have no movable form'? This is all just your particular conception.”

The monk asked, “Since mind is Buddha is not correct, is it that mind becomes Buddha?”

Nanquan said, “'Mind is Buddha' and 'mind becomes Buddha' are just ideas created by your thinking...Do not conceive of mind and do not conceive of Buddha. Whatever you conceive of, it becomes an object of attachment...Because of that the great teacher from Jiangxi said, 'It is not mind, it is not Buddha, it is not a thing.' He wanted to teach you of later generations how to act. Nowadays, students put on religious robes and walk around contemplating things that are of no concern to them. Have you attained anything that way?”

The monk asked, “What does the master mean by 'Mind is not Buddha, wisdom is not the Way?'”

Nanquan said, “Don't conceptualize 'mind is not Buddha, wisdom is not the Way.' I have no mind to bring up – What are you going to attach to?

The monk said, “If there is nothing at all, then how is it different than empty space?”

Nanquan said, “Since it is not a thing, how can you compare it to empty space? And why bring up sameness and difference?”

Concerning “Mind is not Buddha, wisdom is not the Way”

Dogen said:

Great assembly, do you want to clearly understand this point?

The way for students is not to go to bed before your teacher. (EK5-381)

Two ink paintings by 村瀬太乙 Murase Taiitsu (1803-1881)

Moving west

Signed: Taiitsu nanajükyuö (79) heidai, 太乙七十九翁併題

Seals: Taiitsu Röjin sanzetsu & Hakusetsu, 大一老人三絶, 白雪

Date: 1881, the fourth day of the first month

125.7 x 46.8

西行

皇城忍看日蕭々

北面武人朝去朝

一擲妻児是難事

爾来無物孰銀猫

Moving west

It’s sad to see the Imperial palace daily more desolate,

Each dawn sees more samurai moving to the north

Leaving one’s wife and children is truly a hardship.

Since that time there is nothing but this silver cat.

Nanchuan saw the monks of the temple of Nanchu fighting over a

cat. Seizing the cat, he told the monks: ‘If any of you can say a word

of Zen, the cat will be spared.’ No one answered and Nanchuan cut

the cat in two. When the teacher Zhaozho returned to the monastery,

Nanchuan told him what had happened. Zhaozho took off his

sandals, put them on his head, and walked out. Nanchuan said: ‘If

you had been there, you would have saved the cat.’

Like children, the monks were quarreling over a cat. It would kill the

cat. The situation in Japan at the end of the Edo period might be

compared with this Zen koan. Imperialists (south) and the bakufu

(north) fighting each other. Despite the outcome of the conflict, it

would mean the end of the old capital.

Stephen L. Addiss, A Japanese Eccentric: The Three Arts of 村瀬太乙 Murase Taiitsu (1803-1881), New Orleans Museum of Art, 1979.

*

One day at Nanquan's monastery the monks of the eastern and western halls were arguing over a cat. The master saw this and immediately grabbed a knife, picked up the cat, and said, “Someone say a true word and you'll save the cat. Otherwise I'll cut it in two!”

The monks were silent. The master then made the gesture of cutting the cat, and walked away.

Later the senior monk Congshen returned from errands outside the monastery and went to see the master. The master told him the story of the cat. Congshen responded by taking off his straw sandals and placing them on his head (as a gesture of mourning). Then he walked out of the room. As he left, the master said, “If you had been there you would have saved the cat.”

Dogen said:

Nanquan knew how to cut into two, but he didn't know how to cut into one...

If I had been Nanquan, when the students couldn't answer, I would have

released the cat saying that the students had already spoken. (Zuimonki 2–4)

Dogen also said:

His monks were refined, with voices like thunder. (EK9–76)

Once Master Nanquan said to the community, “All the awakened ones of past, present, and future don't know what it is. Cats and cows know what it is.”

Once the monk Xiyun came to stay at Nanquan's monastery. He had already studied with Master Baizhang Huaihai, and was given the respect of an elder monk. One day at the noon meal as Master Nanquan entered the hall with his bowls, Xiyun, sitting in the head monk's seat, didn't stand up to receive him. Nanquan said, “Your reverence, how long have you been teaching the way?”

Xiyun replied, “Since before the era of Bhismaraja Buddha.”

Nanquan said, “Then you're still the grandson of Old Teacher Wang! Get out of here!”

Another time Master Nanquan said to Xiyun, “There is a kingdom of gold and silver houses. Who do you suppose lives there?”

Xiyun said, “Sounds like the dwelling place of the sages.”

The master then said, “There is another person. Do you know in what country he lives?”

Xiyun folded his hands and stood still.

The master said, “You can't answer. Why don't you ask me?”

Xiyun said, “There is another person. Where does he live?”

The master said, “Oh, what a pity this is.”

Once at the start of a work period Master Nanquan asked Xiyun, “Where are you going?”

Xiyun said, “I'm going to gather some greens.”

The master asked, “What will you cut them with?”

Xiyun held up a knife.

The master said, “You understand how to be the guest, but you still don't understand how to be the host.”

When Master Nanquan was finally slowing down with age, his senior disciple Congshen once asked him, “Where will the one who knows eventually go?”

The master said, “This person will go down the mountain to a donor's house and become a water buffalo.”

Congshen said, “I'm grateful for that.”

The master said, “Last night at midnight the moon came in through the window.”.

.