ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

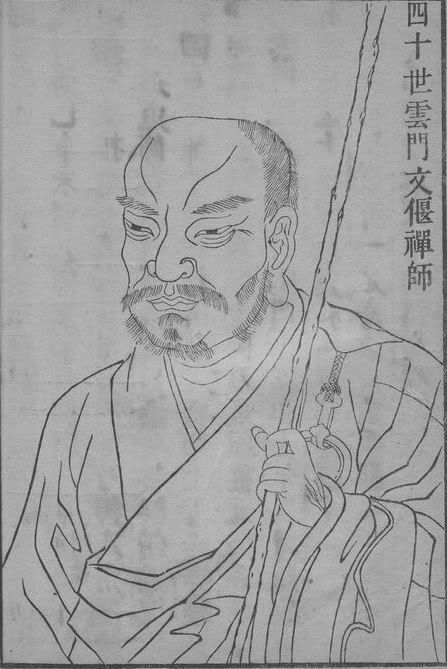

雲門文偃 Yunmen Wenyan (864–949)

雲門匡真禪師廣錄 Yunmen Kuangzhen chanshi guanglu (Yunmen lu)

(Rōmaji:) Ummon Bun'en: Ummon Ōsho kōroku; Ummon-roku

(English:) Extensive Record of Chan Master Yunmen Kuangzhen; Expanded Record of Chan Master Kuangzhen of Yunmen; The Record of Yunmen

(Magyar:) Jün-men Ven-jen: Jün-men Kuang-csen csansi kuang-lu / Feljegyzések Jün-menről

Yunmen Kuangzhen = Yunmen Wenyan

285 cases published in 1076

Tartalom |

Contents |

Jün-men összegyűjtött mondásaiból Yunmen Wenyan (862/864 - 949) |

PDF: Master Yunmen : from the record of the Chan Master "Gate of the Clouds" Zen Master Yunmen: His Life and Essential Sayings

PDF: Facets of the Life and Teaching of Chan Master Yunmen Wenyan PDF: The Making of a Chan Record: Reflections on the History of the Records of Yunmen YUN-MEN YUNMEN WENYAN Encounter Dialogues of Yunmen Wenyan Yün-men Wen-yen: Founder of the Yün-men House Restoring Yunmen Temple |

Zensho W. Kopp illusztrációja

Jün-men Ven-jen/Kuang-csen összegyűjtött mondásaiból

Fordította: Terebess Gábor

Vö.: Folyik a híd, Officina Nova, Budapest, 1990, 101-109. oldal

A csan buddhizmus Jün-men irányzatának alapítója, Ven-jen, Szucsouban született, eredeti családneve Csang volt. Szülei koldusszegények lehettek, már gyermekkorában kolostorba adták. Éles esze, kifejezőkészsége korán megmutatkozott. Elöljárói ösztönzésére eleinte a szerzetesi élet szabályait tanulmányozta, de őt egyre inkább az emberi élet végső igazságai foglalkoztatták. Ezért kereste fel első csan mesterét, a Mucsou-beli Csen Cun-szet (780?-877?), akinek megvilágosulását és nyomorék lábát köszönhette:

„Jün-men kopogtatott Mu-csou mester kapuján.

– Ki az? – szólt ki Mu-csou.

– Ven-jen.

– Mit akarsz?

– Nem vagyok tisztában magammal – mondta Jün-men –, tanácsért jöttem.

Mu-csou kitárta az ajtót, Jün-menre nézett, de azon nyomban be is csukta. Három napon át napról napra bevágta az ajtót Jün-men orra előtt. A harmadik nap, ahogy Mucsou kinyitott, Jün-mennek sikerült betolakodnia a szobába.

– Most beszélj! – ragadta meg őt Mu-csou. – Beszélj!

De Jün-men nem tudta, mit válaszoljon.

– Te semmirekellő! – lökte kifelé Mu-csou, és rácsapta a lábára az ajtót.

Jün-men feleszmélt a fájdalomtól."„Mu-csou ösztönzésére Jün-men útra kelt, hogy meglátogassa Hszüe-fenget. Amikor a kolostorhegy lábánál elterülő faluhoz ért, találkozott egy szerzetessel:

– Tisztelendő barát, megmászod ma a hegyet?

– Igen.

– Van egy üzenetem az apát úrnak, elmondanád-e néki úgy, mintha a sajátod lenne?

– El.

– Ha megérkeztél, várd meg, amíg a szerzetesek összegyűlnek a csarnokba. Amint a mester belép, állj elé, csapd össze a tenyered, és kiálts rá: „Hé, öreg! Akaszd már le a vasnyűgöt a nyakadból!"

Így is történt. Hszüe-feng a szerzetes szavaira leszállt a székéből és vállon ragadta:

– Beszélj, beszélj!

De a szerzetes nem tudta, miről beszéljen.

– Amit mondtál – taszította el őt Hszüe-feng –, nem a saját szavaid voltak.

– De igen – bizonygatta a szerzetes.

Hszüe-feng szólt a segédjének:

– Hozzatok botot, kötelet!

A szerzetes megijedt:

– Valóban nem az én szavaim voltak – vallotta be –, egy szerzetes üzente, akivel a faluban találkoztam.

Hszüe-feng a gyülekezethez fordult:

– Menjetek le a faluba, és köszöntsétek egy ötszáz főnyi közösség megvilágosult tanítómesterét. Hívjátok meg tisztelettel."Jün-men igazi mesterére Hszüe-feng személyében (822-908) talált, Fucsouban. Így az ő eszmei utódjának tekintik. Későbbi vándorlásai során eljutott Saocsouba, a Lingsu-kolostorba, ahol Zsü-min csan mester halála után 918-ban a kolostor feje lett. Idővel saját kolostort alapított a Jünmen-hegyen, ott tanított haláláig.

Még életében elnyerte a Kuang-csen csan mester nevet, halála után pedig a Hung-ming posztumusz címet.

Jün-men a késői Tang-dinasztia legnagyobb csan mestere Lin-csi mellett. Iskolája háromszáz évig virágzott, végül beleolvadt a Lin-csi irányzatba a déli Szung-dinasztia (1127-1279) vége táján. Tanításuk valóban közel áll egymáshoz, de míg Lin-csi ordít és botoz, addig Jün-men fegyvere a szó. Villámgyorsan vág vissza, senkit-semmit nem kímél-tisztel, saját magát se, Lin-csinél is hitrombolóbb, buddhagyalázóbb. Későbbi éveiben egyszavas replikáiról (ji-ce-kuan) híres. Tanítóbeszédeit is ékesszólás jellemzi, mégsem becsülte semmire a puszta szót:

„Hacsak megszólalok, nyelitek a szavaimat, mint legyek a trágyát. Aztán hárman-öten összedugjátok a fejeteket, és végnélküli vitákba bonyolódtok. Nagy kár, Testvéreim!... Az idő nem áll meg a kedvetekért. Arra sincs biztosíték, hogy belégzés után kilélegezhettek... Mi lesz, ha hirtelen halálos nyavalyába estek? Mint a forró vízbe esett rákok, míg a lábatok össze-vissza kalimpál, ugyan hogy játsszátok meg magatokat, mivel henceghettek akkor?"

Soha nem engedte meg, hogy lejegyezzék mondásait. Ami fennmaradt, segédjétől, Hsziang-lin Ceng-jüantól származik, aki suttyomban jegyzetelt papírruhájára. De az ékesszólás és a szóiszony ellentéte csöppet se zavarta Jün-ment: „Beszélhetett naphosszat, de egy szót se ejtett ki a száján. Evett és felöltözött naponta, de mintha nem ízlelt volna egy rizsszemet sem, mintha nem fedte volna magát egy selyemszállal sem." Nemcsak azzal volt tisztában, hogy ezen az úton csak kevesek követhetik – „meredek a Jünmen-hegy" – írta egy költeményében –, de az útmutatása fölöslegességével is: „ha valaki önmagára talált, a mester sem kendőzheti el előle, de ha nem talált magára, a mester nem lelheti meg helyette."

– Mi a Buddha? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

– Egy használt seggtörlő – felelt Jün-men.– Mi a buddhizmus alapeszméje?

– Ha eljő a tavasz, kizöldül a fű magától.– Mi az igaz törvény szeme fénye?

– Az egyetemesség.– Mi szárnyalja túl a buddhák és a pátriárkák tanítását?

– Egy lepény.– Milyen az iskolád szelleme?

– A tudósok kint rekedtek.– Mi az Út?

– Menj!– Mi Jün-men egyetlen útja?

– Az élmény.– Hogy meneküljünk meg születéstől, haláltól?

– Hol vagy?– Hogy szabaduljunk meg a születés és a halál kínjától? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

– Add vissza a születést és a halált! – nyújtotta a markát Jün-men.– Melyik kard vágja el a ráejtett hajszálat?

– Nyissz!– Mit tehet az ember, ha a szülei nem engedik, hogy szerzetesnek menjen?

– Sekély.

– Nem értem.

– Mély.– Ha az ember megöli apját, anyját, vezekelhet a Buddha előtt, de ha megöl Buddhát, pátriárkát, vajon ki előtt vezekelhet?

– Tényleg.

Pierre Székely Péter (1923-2001) rajza– Mit szólsz ahhoz a csodás összhanghoz, ahogy a kiscsirke belülről kopácsolja a tojáshéjat, a tyúk pedig kívülről?

– Visszhang.Jün-men húzott egy vonalat a földre, és azt mondta:

– Minden itt van.

Majd ismét húzott egy vonalat a földre, és azt mondta:

– Mindennek vége.– Mi van, ha már minden lehetőségnek befellegzett? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

– Kapd fel a Buddha Csarnokot – ajánlotta Jün-men –, aztán megbeszéljük.

– Mi köze ennek a Buddha Csarnokhoz?

– Hazudsz! – kiáltott rá Jün-men.

Pierre Székely Péter (1923-2001) rajza– Meg akarjátok ismerni a pátriárkákat? – kérdezte Jün-men a szerzeteseitől. Rájuk bökött a botjával. – A pátriárkák ott ugrálnak a fejetek tetején! És tudjátok, hol van a szemük? Lábbal tapossátok!

Jün-men így szólt a gyülekezethez:

– Nem kérdezem, mi legyen a hónap tizenötödike előtt, de azt mondjátok meg, mi legyen utána?

S minthogy a szerzetesek nem feleltek, maga válaszolt helyettük:

– Minden nap jó nap.

Lacza Márta illusztrációjaJün-men feltartotta a botját a csarnokban:

– Sárkány lett a botból, és elnyelte az egész világot. Mondjátok, hová lettek a hegyek, a folyók és maga a nagy föld?

– Világosíts meg minket, mester! – kérte Jün-ment egy szerzetes.

Jün-men tapsolt egyet és felemelte a botját:

– Fogd!

A szerzetes elvette és kettétörte.

– Még így is megérdemelsz harminc botütést – világosította fel a mester.Jün-men így szólott egyszer a szerzetesekhez:

– Mindnyájan magunkban hordozzuk a világosságot, de ha felfedjük, sötétségre változik.– Milyen irányelveket tudsz adni a végső igazság kereséséhez? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

– Nézz keletre és délre reggel, nyugatra és északra este – mondta Jün-men.

– Mi lesz, ha azt teszem?

– A keleti házban lámpást égetsz, és sötétben kuksolsz a nyugati házban.

Hakuin Ekaku (1685-1768) tusfestménye

李蕭錕 Li Xiaokun (1949-) illusztrációja

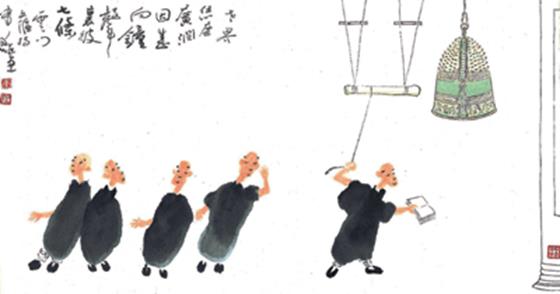

Tarnóczy Zoltán (1951-) tusrajzaJün-men azt kérdezte egyszer:

– Végtelen tág a világ, harangcsendülésre hétrészes csuhát vajon minek öltesz?

Jün-men egy fából faragott oroszlán szájába dugta a kezét, aztán segítségért kiáltott.

– Gyógyszer az egész világ – fordult Jün-men tanítványaihoz –, de ki a beteg?

Majd maga felelt helyettük:

– Karold fel, ami értéktelen, s menten értékessé válik.

Pierre Székely Péter (1923-2001) litográfiája– Bár tüzet mondunk – mondta Jün-men –, mégse égetjük meg a szánkat.

Réber László (1920-2001) rajzaJün-men megkérdezte egy szerzetestől, honnan jött.

– Csianghszi tartományból.

– Motyognak még álmukban az öreg mesterek?

A szerzetes nem válaszolt.

– „Dörömbölj a tér ürességén, és hangot hallasz. Kopogj egy deszkán, és nem ütsz zajt” – idézett Jün-men egy régi buddhista szövegmagyarázatot. Azzal elővette a botját és suhintott vele egyet a levegőbe: – Jaj, de fáj! – mondta. Aztán megkocogtatta a fapadot: – Hallotok valamit?

– Igen – válaszolt egy szerzetes.

– Ó, de műveletlen vagy! – állapította meg a mester.

A gyermek Buddha. Kína, Ming-dinasztia. 13 cm.

Pierre Székely Péter (1923-2001) rajza

Nicolas Burrows linómetszeteSzületése után Buddha egyik kezével az égre mutatott, másikkal a földre, hetet lépett előre, szétnézett a négy égtáj felé és kijelentette: „Ég fölött, ég alatt egyedül én vagyok tiszteletre méltó!”

– Ha ott lettem volna – jegyezte meg a legenda kapcsán Jün-men –, egy csapással agyonverem, és ebekkel zabáltatom fel a húsát.

李蕭錕 Li Xiaokun (1949-) tusfestménye

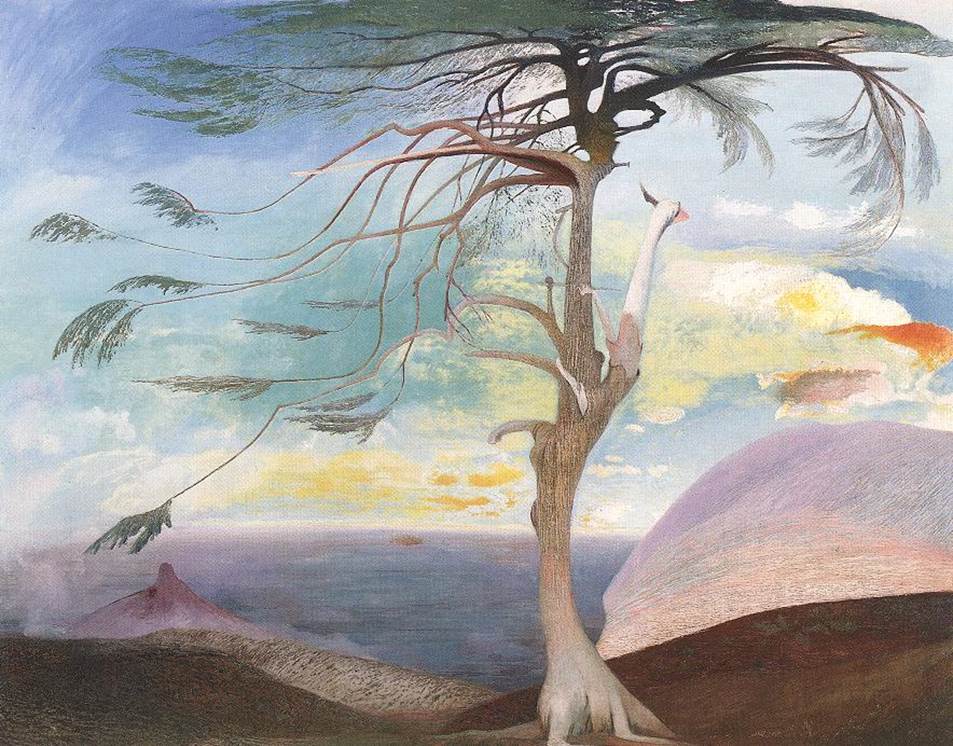

Csontváry Kosztka Tivadar (1853-1919): Magányos cédrus, 1907. Olaj, vászon, 194 x 248 cm. Janus Pannonius Múzeum, Pécs.– Elaggott a fa, hullatja levelét? – kérdezte egy szerzetes Jün-mentől.

– Őszi szélben látszik a törzse – mondta a mester.

Yunmen Wenyan (862/864 - 949)

Fordította: Hadházi Zsolt

http://zen.gportal.hu/gindex.php?pg=4792614&nid=5018592

A tanító elmondott egy történetet:

- A világ tiszteltje, miután megszületett, felemelt kezével az égre mutatott, a másikkal a földre, tett hét lépést, a négy égtáj felé nézett, majd így szólt: „A menny fölött és alatt egyedül én vagyok Tiszteletreméltó.”

Ezután a tanító ezt mondta:

- Ha akkor ott lettem volna, leverem a botommal és húsát éhes kutyák elé vetem, hogy béke uralkodjon az egész világon.

A csarnokban a tanító így szólt:

- Mindnyájatoknak megvan a saját fénye, de mikor ránéztek, homályos. Mi a saját fényetek?

(Minthogy senki nem válaszolt) folytatta:

- A konyha, a raktár és a három kapu.

Majd ezt is mondta:

- Jobb semmivel sem törődni, mint a jóval.

A csarnokban a tanító felemelte botját és ezt mondta:

- A világi emberek azt mondják, hogy van. A két jármű követői azt mondják, hogy nincs. A teljesen megvilágosodottak azt mondják, hogy káprázat. A bódhiszattvák felismerik, hogy természete üres. Az (igaz) szerzetes botot mond amikor botot lát, sétál amikor sétál, ül amikor ül, anélkül, hogy felkavarná (tudatát).

Egy szerzetes megkérdezte a tanítót:

- Mi a Buddhadharma mély értelme?

- Mikor jön a tavasz, a fű magától zöld – válaszolta a tanító.

- Mi az én énem? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

- Aki vándorol és csodálja a hegyeket és folyókat – mondta a tanító.

- Mi a tisztelendő tanító énje?

- Szerencsére a felügyelő eltávozáson van.

- Mi az, mikor az ember szájával mindent lenyel?

- A hasadban vagyok.

- Miért van a tisztelendő tanító a hasamban?

- Add vissza a szavaimat!

- Mi az út?

- Menj!

- Nem értem, kérlek taníts!

- A tisztelendő barát maga kéne megvizsgálja, hogy tisztába jöjjön. Miért kellene (más) véleménye?

- Hogyan hagyjunk fel születéssel és halállal?

A tantó széttárta karjait és ezt mondta:

- Állítsd vissza születésemet és halálomat.

- Micsoda Yunmen kardja? – kérdezte egy szerzetes.

- Pátriárka. – válaszolt a tanító.

- Mi van a rejtettben?

- Átjáró.

- Mi az a kard, mely elvágja a lehulló hajszálat?

- Csont – mondta, majd hozzátette -, hús.

- Mi a helyes Dharma szem?

- Egyetemesség.

- Mi a vizsgálódó képesség?

- Visszhang.

- Mi Yunmen egyetlen útja?

- Közvetlenség.

- Mikor valaki megöli apját és anyját, megbánhatja tettét és fogadalmat tehet javulására a buddhák előtt. De mikor megöli a buddhákat és pátriárkákat, ki előtt tegyen bűnbánatot és fogadalmat a javulásra?

- Felfedetett.

- Mi az, mikor valaki átdöfi a falat, hogy fényt nyerjen?

- Lehetőség.

- A három test közül melyik tanítja a Dharmát?

- Lényeg.

- Egy ős mondta, „A megvilágosodás után minden karmikus akadály üres. Előtte minden karmikus adósságot meg kell fizetni.” A második pátriárka megvilágosodott volt, vagy sem?

- Tévedhetetlenség.

A csarnokban a tanító így beszélt:

- Mikor a fény nem átható, kétfajta betegség létezik. Az első, mikor mindenhol hiányzik a tisztaság és a dolgok jelen vannak előtted. A másik, mikor bár a fény áthatja mindennek ürességét, mégis ott van valaminek a hasonlósága, és ez is azért van, mert a fény nem teljesen átható. A Dharmakájának szintúgy kétféle betegsége van. Az első, mikor valaki eléri a Dharmakáját nem tudja elhagyni a dolgok valóságának fogalmát, ezért megőrzi az én képzetét, így megreked a határvonalán. A másik az, mikor még ha valaki áthatotta is a Dharmakáját, még mindig megragadja és vágyódik a túlvilágra.

![]()

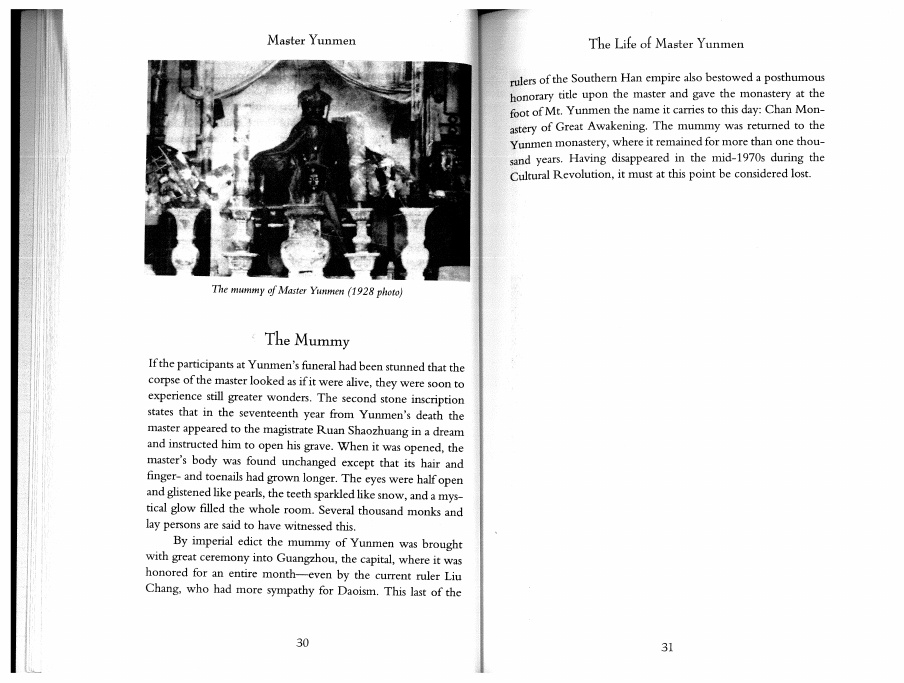

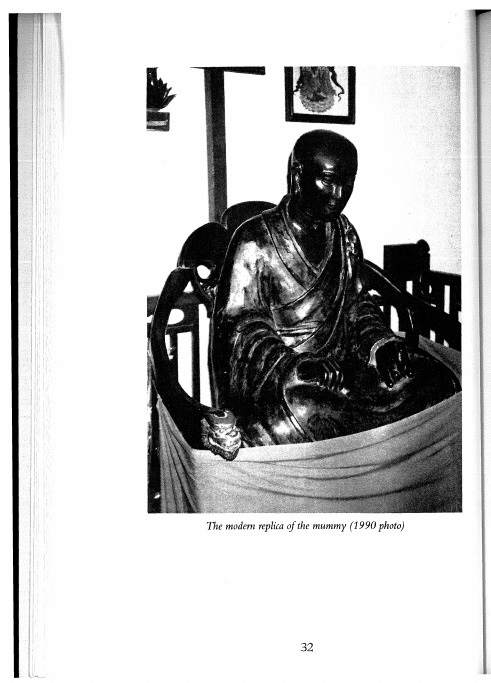

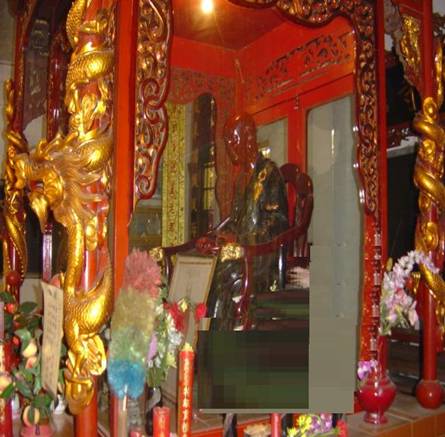

The Mummy of Master Yunmen

by Urs App

文偃祖師金身 A wooden replica of Master Yunmen's mummy, Yunmen Monastery, Southern China, 2006.

http://www.senwanture.com/religion/religion-fo%20dgiau-eun%20mem%20zon.htm

Urs App (1949-):

Facets of the Life and Teaching of Chan Master Yunmen Wenyan (864-949)

A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board, 1989

Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International, 342 p.

http://universitymedia.org/downloads/App_Yunmen_Dissertation_1989.pdf

The Making of a Chan Record: Reflections on the History of the Records of Yunmen 雲門廣錄

禅文化研究所紀要 Zen bunka kenkyūjo kiyō (Annual Report from the Institute of Zen Studies) No. 17 (May 1991): pp. 1–90.

http://universitymedia.org/downloads/App_Making_of_Chan_Record_1991.pdf

Master Yunmen : from the record of the Chan Master "Gate of the Clouds"

translated, edited, and with an introduction by Urs App

New York : Kodansha International, 1994. 252 p.

https://cloudflare-ipfs.com/ipfs/bafykbzacectxukqsqdbhz4uxjxk32mrvpqowlznb6m5u5je4zc2lrensbw4mu?filename=Urs%20App%20%28Editor%29%20-%20Master%20Yunmen_%20From%20the%20Record%20of%20the%20Chan%20Master%20_Gate%20of%20the%20Clouds_%20%28incomplete%29-Kodansha%20America%20%281994%29.pdfZen Master Yunmen: His Life and Essential Sayings

by Urs App

Shambala, 2018

https://www.shambhala.com/authors/a-f/urs-app/zen-master-yunmen-15023.htmlZen-Worte vom Wolkentor-Berg. Darlegungen und Gespräche des Zen-Meisters Yunmen Wenyan (864–949). Bern / München: Barth, 1994

![]()

Yün-men Wen-yen: Founder of the Yün-men House

by John C. H. Wu

Chapter XII

In: The Golden Age of Zen

Taipei : The National War College in co-operation with The Committee on the Compilation of the Chinese Library, 1967, pp. 212-228.

Ch’an masters, like other men, may be divided into two types. Some are slow-breathers, others are fast-breathers. Of the founders of the Five Houses of Ch’an, Kuei-shan, Tung-shan and Fa-yen belong to the slow-breathers, while Lin-chi and Yünmen, belong to the fast-breathers. Of these two, Lin-chi breathes fast enough, but Yün-men breathes faster still. Lin-chi’s way is like the Blitzkrieg. He kills his foes in the heat of the battle. He utters shouts under fire. When the lion roars, all other animals take cover. No one can encounter him without his head being chopped off by him. It makes no difference whether you are a Buddha, a Bodhisattva or a Patriarch, Lin-chi will not spare you if he should chance to encounter you. So long as you bear a title or occupy any position, Lin-chi will send out his True Man of No Title to kill you off in the split second. So terrible is Lin-chi! But more terrible is Yün-men!

Lin-chi only kills those whom he happens to encounter. Yinmen’s massacre is universal. He does away with all people even before they are born. To him the “True Man of No Title” is already the second moon, therefore a phantom not worth the trouble of killing. Yün-men seldom if ever resorts to shouts or beatings. Like a sorcerer he kills by cursing. His tongue is inconceivably venomous, and, what makes the case worse, he is the most eloquent of the Ch’an masters.

Yün-men is a radical iconoclast. In one of his sermons to his assembly, he related the legend that the Buddha, immediately after his birth, with one hand pointing to heaven and the other pointing to earth, walked around in seven steps, looked at the four quarters, and declared, “Above heaven and below heaven, I alone am the Honored One.” After relating the story, Yün-men said, “If I were a witness of this scene, I would have knocked him to death at a single stroke, and given his flesh to dogs for food. This would have been some contribution to the peace and harmony of the world.”

Vimalakirti fared no better with him. One day, beating the drum, he announced, “Vimalakirti’s realm of wonderful joy is shattered to pieces. Bowl in hand, he is now heading toward a city in Hunan to beg for some gruel and rice to eat.”

It seems as though Yün-men had no respect for any person. He once quoted these words: “He who hears the Tao in the morning can afford to die in the evening.” Everybody knows that it was Confucius who had uttered these words. But Yün-men did not even mention his name, but merely commented airily, “If even a worldly man could have felt like that, how much more must we monks feel about the one thing necessary to us?”

Nor was Yün-men more polite with himself than with others. For instance, he said to his assembly, “Even if I could utter a wise word by the hearing of which you attain an immediate enlightenment, it would still be like throwing ordure on your heads.” This is to say that even if the master had done all that could have been expected of him, and even if his words had been instrumental to their awakening, still the end can never justify the means. To Yün-men, any speech, however legitimate from the worldly point of view, is out of place in regard to the Eternal Tao. He seems to be obsessed with the primary insight of Lao Tzu: “The Tao that could be expressed in words is not the Eternal Tao.” As Yün-men was interested in nothing else than the Eternal Tao, what use could he have for mere words? That is why whenever he had to make a conference he always apologizes for his speaking at all. The beginning of his very first sermon as the Abbot of Ling-shu Monastery is typical:

Do not say that I am deceiving you today by means of words. The fact is that I am put under the necessity of speaking before you and thereby sowing seeds of confusion in your minds. If a true seer should see what I am doing, what a laughing-stock I would be in his eyes! But now there is no escape from it.

The great paradox about Yün-men is that, on the one hand, he had an extraordinary gift of eloquence, while on the other hand he had a phobia for the word, as if every word were an intruder into the sacred ground of the inexpressible Tao. What a tension this must have created in his mind! Fortunately, he hit upon a happy solution of this tension with another paradox. The man who has realized his self can “stand unharmed in the midst of flames.” So “even if he talks all day, in reality nothing cleaves to his lips and teeth, for he has actually not spoken a single word. Likewise, although he wears his clothes and takes his meals every day, actually he has not touched a single grain of rice nor put on a single thread of silk.”

The keenness of his mind reached an agonizing degree. He seemed to be sensitive to every motion of his own mind and his self-knowledge enabled him to discern the thoughts and feelings of others. From the same source of sensitivity have sprung many a piercing insight into the secrets of spiritual life. For instance, he said, “Each of us carries a light within him, but when it is looked at it is turned into darkness.” Here is a profound insight whose authenticity is beyond question.

Yün-men was conscious that his way was the narrow way. He appealed only to the highly intelligent. His House has been characterized by all students of Ch’an as steep and abrupt. He himself wrote a poem descriptive of the style of his Ch’an:

Steep is the Mountain of Yün-men, rising straight upward, Leaving the white clouds down below!

Its streams, dashing and eddying about, allow No fish to linger around.

The moment you step into my door, I already know What kind of ideas you’ve brought with you.

What’s the use of raising again the dust Long settled in an old track?Such, then, is the style and aura of the man, into whose life and teachings we are going to peep, with an undaunted spirit! We are told that one day Yün-men put his hands into the mouth of a wooden lion and cried at the top of his voice, “Help, help! I am bitten to death.” Now we are going to put our hands into Yün-men’s mouth, but there is no reason for fear. Even if we should meet with the same terrible experience of being bitten by a lion, we could still survive as he did.

Yün-men Wen-yen (d. 949) was born into a Chang family in Chia-hsin of Chekiang. Most probably, his family was in the pinch of extreme poverty, and he was placed when a mere boy by his parents in the hands of the Vinaya master Chih-ch’eng of the K’ung-wang Temple as a novice. He was noted for his exceptional intelligence, especially for his natural gift of eloquence. As soon as he was of age, he had his head shaved and was duly ordained. He continued to wait upon his master for a few more years, during which period he delved deeply into the Vinaya branch of Buddhist scriptures. All this learning, however, did not satisfy his deeper needs. He felt that it did not throw any light on the most vital problem of his own self. Hence he went to see the Ch’an master Mu-chou, the disciple of Huang-po, hoping for the necessary instructions. But as soon as Mu-chou saw him, he slammed the door in his face. When he knocked at the door, Mu-chou asked from inside, “Who are you?” After he had told him his name, Mu-chou asked, “What do you want?” Yün-men replied, “I am not yet enlightened on the vital problem of my own self, and I have come to beg for your instructions.” Mu-chou opened the door but, after a quick look at him, shut it again. In the following two days, Yün-men knocked and met with the same experience. On the third day, as soon as the master opened the door, Yün-men squeezed in. The master grabbed him, saying, “Speak! Speak!” As Yün-men fumbled for something to say, the master pushed him out, saying “A Ch’intime relic of a drill!” and shut the door so quickly that it hurt one of Yün-men’s feet. This initiated him into Ch’an. At Muchou’s recommendation, he went to see Hsüeh-feng (822-908).

As he arrived at the village below the mountain where Hsüeh-feng was, he met a monk and asked him, “Is Your Reverence going up the mountain today?” As the monk said that he was going up, Yün-men asked him whether he would be willing to bring a timely message to the Abbot but present it as his own. The monk having consented to do so, Yün-men said, “After your arrival at the monastery up there, as soon as you see the Abbot entering the hall and the assembly gathered together, go forward at once, clasp your hands, and, standing erect before him, say: ‘O poor old man! why does he not take off the chain from his neck?!’” The monk did exactly as he had been told to do; but Hsüeh-feng sensed immediately that those words were not his own. Coming down from his seat, he grabbed him firmly, saying, “Speak! Speak!” As the poor monk knew not what to say, Hsüeh-feng pushed him away and said, “Those words are not yours.” At first he still insisted that they were his own words. But the relentless master called for his attendants to come with ropes and sticks. Frightened out of his wits, the monk confessed, “They are not my words. It was a monk from Chekiang I met at the village who taught me to speak thus.” Then the Abbot said to his community, “Go, all of you, to the village below to greet the one destined to be the spiritual guide of five hundred persons, and invite him to come.”

The next day, Yün-men came up to the monastery. On seeing him, the Abbot said, “How could you arrive at your present state?” Yün-men said nothing but just lowered his head. Right from that moment, he saw eye-to-eye with the master. He stayed several years with Hsüeh-feng, under whose guidance he delved more and more deeply into the profundities of Ch’an, until the master transmitted to him the Dharma seal.

Yün-men then journeyed forth to visit the luminaries of different quarters, leaving profound impressions everywhere. Finally he went to Ling-shu, where the master Chih-sheng was Abbot. Now, Chih-sheng had been the Abbot of Ling-shu for twenty years, but, for a reason known to himself, he kept the assembly leader’s seat vacant all this time, although from time to time he did speak, rather mysteriously, of someone destined to be his assembly leader. On the day when Yün-men was to arrive, the Abbot suddenly ordered his monks to strike the bell and go out of the outermost gate of the monastery to welcome the assembly leader. The whole community went out, and, lo and behold, there arrived Yün-men!

After the demise of Chih-sheng, the Prince of Kuang ordered Yün-men to be the Abbot of Ling-shu. At his inauguration, the Prince came in person to attend the meeting, saying, “Your humble disciple begs for your instruction.” “Before your eyes,” said the new Abbot, “lies no other road.” To Yünmen there is only one road, not many roads. But what is the one road he had in mind? In the answer to this crucial question lies the touchstone of all his philosophy.

Once Yün-men quoted a saying from Ma-tsu: “All words belong to the school of Nagarjuna, with ‘this one ’ as the host.” He then remarked, “An excellent saying! Only nobody asks me about it.” At that moment a monk came forward and asked, “What is the school of Nagarjuna?” This called the Abbot’s ire upon him, “In India, there are ninety-six schools, and you belong to the lowest!” In Ma-tsu’s saying, the important point is obviously “this one,” while the school of Nagarjuna is merely a window dressing. Ma-tsu could have mentioned any other school without changing the living meaning of the sentence. But the foolish monk took the accidental for the essential, and left out the essential entirely. For Yün-men, as for Ma-tsu, the one thing necessary is the realization of “this one” who is none other than everybody’s own self. This is not only the one goal but also the one road, for the simple reason that there is no road to lead to the self outside of itself.

“This one” who is your true Self is complete in itself and “lacking in nothing.” Time and time again, Yün-men asked his assembly, “Are you lacking in anything?” Time and time again, he reminded them that only one thing is essential, that all other things are of no concern to them, that in this vital matter they must rely on themselves, for no one else can take their place. All his sermons were like the signs of a dumb person trying to hint at what is in his mind. The following discourse is as typical as any:

My duty compels me to attempt the impossible. Even in telling you to look directly into yourself and to be unconcerned about other things, I am already burying the real thing under verbiage. If you proceed from thence and set out in quest of words and sentences, cudgeling your brains over their logical meanings, working out a thousand possibilities and ten thousand subtle distinctions, and creating endless questions and debates, all that you will gain thereby is a glib tongue, while at the same time you will be getting farther and farther away from the Tao, with no rest to your wandering. If this thing could really be found in words, are there not enough words in the Three Vehicles and the twelve divisions of scriptures? Why should there be a special transmission outside the scripture? And if you could get at it by studying the various interpretations and learned commentaries on such terms as “potentiality” and “intelligence,” then how is it that the saints of the ten stages who could expound the Dharma as resourcefully as the clouds and rain, should still have incurred the reproach that they only saw the self-nature vaguely as through a veil of gauze. From this we can know that to follow the intentions and vagaries of your mind is to be separated from your self as far as the earth from the sky. But if you have really found your true self, then you can pass through fire without being burned, speak a whole day without really moving your lips and teeth and without having really uttered a single word, wear your clothes and take your meal every day without really touching a single grain of rice or a single thread of silk. Even this talk is but a decoration on the door of our house. The important thing is your experiential realization of this state...”

Yün-men has been noted in the Ch’an circles for his “oneword barrier.” However, this is merely one of his tactics in rousing the dormant potentiality of his disciples, and should not be regarded as an essential element of his vision. Some students of Ch’an have thought that his one-worded answers have no rational bearing whatever on the questions. They tend to make a cult of rationality. I believe that this is a wrong approach, as wrong as to make a cult of irrationality. The truth is that Yünmen, like all great masters of Ch’an, had moved beyond the rational and irrational. His answers were his spontaneous reactions to the questions. They were at least occasioned by them, and in this sense and to this extent they did have a bearing on the questions. Not only were they occasioned by the questions, but also they were each directed to the questioner, whose spiritual state and needs the master had sensed intuitively from the very question he had raised. If, therefore, they had no logical bearing on the questions, at least they had a vital bearing on the persons asking those questions.

Here I will present a cluster of Yün-men’s one-worded answers together with the questions that had called them forth. I shall refrain from any more comments, leaving the reader to shift for himself.

1. Question: “What is the right Dharma Eye?”

Answer: All-comprehensive!

2. Question: How do you look at the wonderful coincidence between the chick tapping inside its shell and the hen’s pecking from outside?

Answer: Echo.

3. Question: What is the one road of Yün-men?

Answer: Personal-experience!

4. Question: One who is guilty of patricide can repent and vow to amend his life before Buddha. But if he has killed the Buddha and the Patriarchs, before whom can he repent and make the promise to amend?

Answer: Exposed!

5. Question: What is Tao?

Answer: Go!

6. Question: Where our late Teacher (Ling-shu) remained silent when a question was put him, how shall we enter it in the epitaph?

Answer: Teacher!

There is no particular magic in the “one-word barrier of Yün-men.” One word or many words, there is always the barrier for you to break through. It is just one of his ways of evoking the Incommunicable.

As another means of his teaching, Yün-men used his staff as a pointer to “this one” or the true self, who is identical with the Absolute. We must always keep this in mind in reading some of his utterances which on their surface may sound like the braggings of a magician waving his wand. Let me give some instances. One day, Yün-men held up his staff before his assembly and declared, “This staff has transformed itself into a dragon, and has swallowed up the whole cosmos. Where then have the mountains, rivers and the immense earth come from?” On another occasion, holding up his staff, he sang aloud, “Lo and behold! the old fellow Shakya has come here!” On still another occasion, he abruptly asked his audience, “Do you want to make the acquaintance of the Patriarchs?” Pointing at them with his staff, he announced, “The Patriarchs are capering on your heads! Do you want to know where their eyes are? Their eyes are under your feet!”

Once he asked a deacon, “What did the ancients wish to indicate by raising and lowering a dust-whisk?” The deacon replied, “To reveal the self before the raising and after the lowering.” This evoked from him a hearty approval, which he so rarely gave.

Sometimes, he dispensed with his staff and pointed to the self more directly, as where he said, “Buddhas innumerable as specks of dust are all in your tongue. The scriptures of the Tripitaka are all under your heels.” This insight is, according to Yün-men, only one of the entrances to the self. The self being beyond space and time, it is nowhere and yet it is manifested everywhere and in all things. Therefore, to try to find him only in the innermost recesses of your mind is to miss him. On this point, Yün-men saw eye-to-eye with his great contemporary Ts’ao-shan. He once asked Ts’ao-shan, “What is the best way of being intimate with this man?” The latter replied, “Don’t seek intimacy with him esoterically and in the innermost recesses of your mind.” Yün-men asked again, “What follows if we don’t?” Tsao-shan answered, “Then we are truly intimate with him.” Yün-men exclaimed, “How true! How true!”

It makes no difference whether he was influenced by Ts’aoshan. What is certain is that Yün-men’s final vision transcended the esoteric and the exoteric, the inner and the outer. He came to see the Absolute in all things and in all places. “Within the cosmic order, amidst the universe, there is a mysterious gem hidden in the depth of a visible mountain.” Yün-men used these words of Seng-chao to hint at the Immanence of the Absolute. But immediately he added, “it (the mysterious gem) carries a lantern into the Buddha hall, and puts the three entrance doors of the monastery on the lantern. What is It doing?” Having no answer from the assembly, he gave the answer himself, “Its mind veers according to the course of things.” After a moment of silence, he added, “As the clouds arise, thunder starts.”

Now, that there is an invisible gem in the midst of the phenomenal world is comparatively easy to comprehend. But what could he mean when he said that the invisible gem is carrying a lantern into the Buddha hall and putting the three doors of the monastery on the top of the lantern? This phenomenal absurdity was obviously meant to lift the minds of his hearers to the transcendence of the Absolute.

The answer that he gave to his own question evokes still another aspect of the Absolute—how It functions in the phenomenal world. The lantern symbolizes the spirit of Ch’an. The three entrance doors stand perhaps for the three Vehicles (the Shravaka, the Pratyeka-Buddha, and the Bodhisattva). Putting them together on the lantern is reducing and uniting them into the One Vehicle as spoken of by the Sixth Patriarch. At first the three Vehicles had each arisen to answer the needs of men. Likewise the One Vehicle has arisen to meet the needs of new men. This is what Yün-men meant when he said that the Absolute, when applying Its mind to the phenomenal world, veers according to the course of things, and Its operation here is as spontaneous as Its operation in the natural world: “As clouds arise, thunder starts.”

This leads us to the famous “Three propositions of the House of Yün-men.” Although these three propositions were first formulated and brought together as a continuous series by Yün-men’s disciple Teh-shan Yüan-mi (who, flourished in the latter part of the 10th century), the ideas were implicit in the teachings of the master. The three propositions are:

1. Permeating and covering the whole cosmic order.

2. Cutting off once for all the flow of all streams.

3. Following the waves and keeping up with the currents.

All these three refer ultimately to the Absolute. They represent Its three aspects as we view It, forming, as it were, a dialectical series. Looking at its immanent aspect, we find that It permeates and covers the whole of the cosmos and all its parts. In Its transcendent aspect, It is infinitely higher than the cosmos, alone and peerless, in no way approachable by any being in the world. This is what is suggested by the phrase “Cutting off once for all the flow of all streams.” But in the end we see the great return. For, in Its functioning in the world, It follows the waves and keeps abreast of the currents of the time.

In the sayings of Yün-men, we can find apt illustrations of each of the three phases. For instance, he quoted his late master Hsüeh-feng’s saying: “All the Buddhas of the past, present and future are turning the great wheel of the Dharma over the blazing fire.” Then he commented on it, saying, “Rather the blazing fire is expounding the Dharma to all the Buddhas of the three times, and they are standing on the ground and listening.” He saw the Absolute in the fire, in the grain of sand, and even in the smallest speck of dust. He saw it near and far, in himself and in the yonder Pole Star. This illustrates the first proposition.

Yün-men was once invited to a vegetarian feast held in the palace. A court official asked him, “Is the fruit of Ling-shu ripe yet?” Yün-men asked back, “In what years, according to your view, could it ever be said to be unripe?” This was one of the most delightful repartees for which he was famous. But did it answer the officer’s question? Apparently, what the officer wished to know was how his work as the Abbot of Ling-shu (which is the Chinese for the “holy tree”) was progressing, whether the “holy tree” had produced any ripe fruit in the form of enlightened disciples. But instead of answering the question, the Abbot used it as a springboard to leap from time to eternity by equating the fruit of the holy tree with the eternal Tao or, perhaps, with “this one.” Only in the realm of time can you speak of progress, of birth, growth, ripening and decay, which are entirely inapplicable to the realm of the Absolute. This was Yün-men’s way of lifting the mind of the questioner from the phenomenal to the supra-phenomenal, and it is a clear instance of “cutting off once for all the flow of all streams.” Another interesting instance is where he was asked by a monk who had just finished the summer retreat how he should answer if anybody should ask him about his prospects ahead. The Abbot’s reply was, “Let everyone step backwards!” Instead of thinking of forging ahead in the phenomenal world, the Abbot wanted him to return where there is no progress, where “the pure wave cannot be reached by any route.”

Yün-men’s mind seemed to be particularly in its element in dealing with this transcendental aspect of the Absolute. One of the most beautiful and pregnant of his utterances was his lightning-like answer to the question: “What happens when the tree has withered and its leaves dropped?” All that he uttered was a phrase of four words: T’i lu chin-feng! (“Body bared to golden wind”). The phrase carries a dual meaning. On the natural plane, it means, of course, that the trunk of the tree is exposed nakedly to the breath of autumn. On the spiritual plane, it suggests that the Dharmakaya or the true self in its purity is now in its natural element—eternity. The phrase is clear like a crystal, evoking the autumn sky without a speck of cloud, which in turn lifts our hearts to the empyrean of pure light.

It would be interesting to compare this cameo-like phrase with Tung-shan’s

"The withered tree flowers into a new spring far, far beyond the realm of Time."

What different types of landscapes they present to us! In Tung-shan we find the cordial warmth of a mild spring day. In Yün-men we find the refreshing coolness and transparent limpidity of a moonlit night in autumn. Yet both of them were spiritual giants, with their minds soaring beyond the orbits. Heaven, therefore, must be a house of many mansions to be the home of so many different types of excellence.

Now, an outstanding trait of Ch’an common to all the Five Houses is the idea that in the life of the spirit you will never reach a point where it is no longer possible for you to take another step upward. Even if you had climbed to the crest of a mountain, you must still go upward by coming down to the plains. Even if you had reached the other shore, you still must advance farther by returning to this shore to live the life of a man who is truly a man. You must shed off whatever esoteric habits you may have acquired previously, and become all things to all men. After having cut off the flow of all streams, you are now to keep yourself in constant flux and be perfectly at home in it.

The striking thing about Yün-men is that in soaring to the transcendent sphere he shoots like a rocket straight up without making any circles like the eagle, and yet when he comes down to the earth, he wants us to veer with the wind and to follow all the waves, tides, currents, eddies, swingings back and forth of the river of life. For this is how the Eternal Tao functions in the world.

When he was asked, “What is Tao?” Yün-men uttered just one word, “Go!” This word is so pregnant in meanings, that it is impossible to pin him down to a definite connotation. But in the context of his whole teaching, it would not be too far off the mark to say that one connotation he had in mind is, “Go your way free and unencumbered, doing everything as befitting your state without being attached to particular methods or to the results of your doing. Do your work and pass on.”

He was deeply convinced that “true Emptiness does not destroy the existential realities,” and that “the Formless, is one with the world of forms.” He assured a prominent lay disciple of his that there is no difference between the lay and the cleric in the matter of self-realization, quoting a passage from the Lotus Sutra in support of his conviction that all activities by way of ministering unto the existential needs of oneself and others are in no way incompatible with the nature of Reality. Of course, different states of life entail different duties, and everyone must put his feet solidly on the ground and walk steadily in the path of duty. This is much better than to indulge in wild fancies and empty speculation. To the enlightened man, “Heaven is heaven, earth is earth, mountain is mountain, river is river, monk is monk and layman is layman.” He discouraged all theoretical and epistemological inquiries as a waste of one’s precious time. The important thing is to be one’s sself.

Once you have become your self, you are freed from all the inhibitions and fears bred by the ignorance and cravings of your ego. Then you will be happy when you work, happy when you play, happy to live and happy to die. When a monk asked the master, “Who is my self?” he answered, “The one who roams freely in the mountains and takes his delight in the streams.” This might not be descriptive of the state of the questioner, but certainly revealed the beautiful inner landscape of Yün-men himself. In fact, one of his happiest utterances was: “Every day is a good day!”

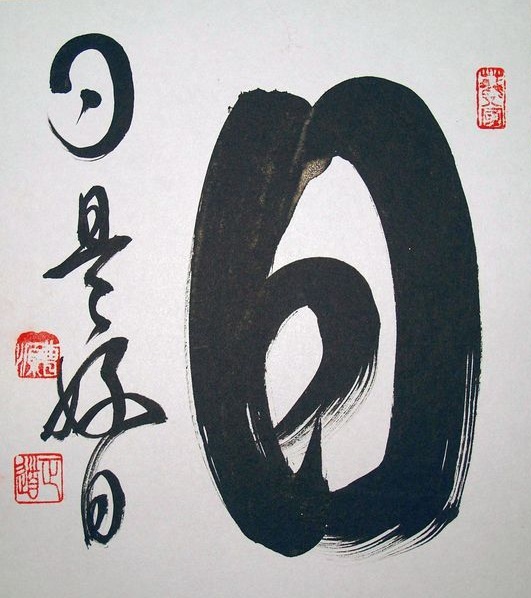

"Everyday is a good day." Japanese Zen Calligraphy by 原田正道 Harada Shōdō

Encounter of Yun-men Wen-yen and Fa-yen Wen-i

by 賢江祥啓 Kenkō Shōkei (aka Kei-Shoki) (1473-1523)

Freer and Sackler Galleries

Encounter Dialogues of Yunmen Wenyan

compiled by Satyavayu of Touching Earth Sangha

DOC: Treasury of the Forest of Ancestors

Master Yunmen Wenyan was born and raised in Jianxing, a town between Shanghai and Hangzhou on China’s eastern coast. On reaching adolescence, he decided to enter the monkhood, and became a novice at the local temple. He focused on studying the codes of monastic discipline (vinaya) with his first teacher, Zhicheng, and eventually received full ordination at a temple near Suzhou. Afterwards he returned to serve as Zhicheng’s attendant, continuing his vinaya studies and beginning to lecture on them.

At some point in his mid-twenties, Wenyan decided to investigate Zen teaching, and he traveled seventy miles upriver from Hangzhou to the town of Muzhou to seek out the aged and reclusive master called “Elder Chen”. This master, also known as Muzhou Daoming, had been a prominent disciple of Master Huangbo, but after a career as monastic abbot he had since left the monkhood and supported himself by making sandals. Now quite old and living a reclusive life in a one-room hermitage, Master Chen refused to see Wenyan despite the young monk's repeated attempts at having a meeting. But Wenyan was persistent and again knocked on his door.

Master Chen said, “Who is it?”

Wenyan replied, “It’s me, Wenyan.”

The master opened the door but blocked the entrance and said, “Why do you keep coming?”

Wenyan said, “I’m not yet clear about myself.”

The master said, “That's completely useless trash!,” pushed Wenyan away, and slammed the door shut.

At this, Wenyan had a deep realization.

Wenyan stayed on to practice and study with Master Chen for several years, and was deeply influenced by his simple style of living and direct, dramatic expression. Eventually Master Chen sent Wenyan to study with the renowned Master Xuefeng Yicun for further training. There at the monastery at Snow Peak, Wenyan spent a number of years sharpening his insight and honing his conduct with Master Xuefeng, before finally leaving on pilgrimage in his late thirties. He then visited a number of teachers, particularly seeking out several prominent disciples of Master Dongshan Liangjie, including Caoshan Benji, Sushan Guangren, Tiantong Xianqi, and Yuezhou Qianfeng.

When Wenyan was fourty-seven he made a pilgrimage to Cao Creek, the teaching site of the legendary Master Huineng, in far southern China. In the nearby city of Shaozhou, Wenyan met a master named Rumin who was abbot of Inspiration Planting (Lingshu) Monastery. The two became close friends, and Wenyan became the head monk at this monastery. Seven years later, just before Rumin passed away, the abbot wrote a letter to his supporter, the regional ruler Liu Yan (who had begun to declare himself Emperor Gaozu) requesting that Wenyan be approved as the new abbot of Lingshu. Gaozu approved, and soon became an avid supporter of Wenyan, inviting him to the court of the newly independant “Southern Han” empire in Guangzhou for honors.

Thus Wenyan began his teaching career as abbot of Lingshu Monastery. But after four years at this post he decided that the frequent receiving and entertaining of visitors at this socially prominent monastery was too distracting for him and his students. Having received permission from Gaozu, Wenyan sought and found a more secluded place nearby for a training center, and, on the ruler's orders, construction was begun on a new monastery at Cloud Gate (Yunmen) Mountain.. In a few years the new center was built, and here Wenyan, now called Master Yunmen, lived and taught for the remainder of his life.

Only three years after Master Yunmen's death, the first compilation of the teaching dialogues of the Zen tradition, The Ancestor's Hall Collection, was first created, and the more extensive and influential collection, The Jingde Era Transmission of the Lamp, was composed some fifty years later. The relative close proximity in time of these records to the life of Master Yunmen meant that a large selection of his teaching words were available, were likely relatively accurate, and were fresh in the minds of the Zen community. The fact that he was associated with the lineage of Master Xuefeng, a wide family that also included the authors of these collections, helped ensure that his teachings had a prominent place in the records. But it must have been the brevity, forcefulness, and startling unusualness of his expression that led to their immense popularity, celebrated more than the teachings of his contemporaries, and to the fact that there are more sayings attributed to Master Yunmen in the records of the Zen tradition than any other master.

One day a student asked Master Yunmen Wenyan, “What is the teaching of the Buddha’s whole lifetime?”

The master said, “Speaking in tune with the particular occasion.”

Someone once asked Master Yunmen, “Since ancient times, the old worthies have transmitted mind by mind. Today I ask you, master: What method do you use?”

The master said, “When there’s a question, there’s an answer.”

The questioner continued, “In this case, it isn’t a wasted method.”

The master said, “No question, no answer.”

Once the Southern Han Emperor Gaozu summoned Master Yunmen to the capital for an audience. The Emperor asked, “What is Zen all about?”

Master Yunmen said, “Your Majesty has the question, and your servant the monk has the answer.”

The Emperor inquired, “What answer?”

The master replied, “I request Your Majesty to reflect upon the words your servant just uttered.”

One day someone asked Master Yunmen, “When you make offerings to the arhats, do they come?”

The master said, “If you don’t ask, I don’t answer.”

The questioner continued, “Please master, tell me!”

The master said, “Join your hands in greeting in front of the main gate, and offer incense in the Buddha hall.”

Once someone asked Master Yunmen, “What’s my central concern?”

The master said, “I have sincerely accepted your question.”

Another time someone asked Yunmen, “What is most urgent for me?”

The master said, “The very you who is afraid that he doesn't know.”

Someone once asked Master Yunmen, “Though this is constantly my most pressing concern, I cannot find any way in. Please, master, show me a way in.”

The master said, “Just in you present concern there is a way in.”

Once Master Yunmen said to the assembly, “In the lands of all ten directions there is nothing but the teaching of the 'One Vehicle'. Tell me, is your self inside or outside the one vehicle?”

On behalf of a silent audience he said, “Come in!”

Then he added, “There you are!”

Another time someone said, “Please master, show me a way in!”

Master Yunmen said, “Slurping gruel, eating rice.”

Once Master Yunmen said, “You, just you, who everyday take your bowl and eat rice - what do you call ‘rice’? Where is there a single grain of rice?”

Master Yunmen once brought up this story:

“Master Xuefeng said, 'There are many who sit by a rice bucket starving to death, and many who sit by a river dying of thirst.' Master Xuansha commented, 'There are many sitting inside a rice bucket starving to death, and many submerged in water still dying of thirst.'”

Then Master Yunmen said, “The whole body is rice, the whole body is water!”

Once at a donated meal Master Yunmen asked the monks, “Forget about all the phrases that you’ve learned in the monasteries and tell me: how does my food taste?”

On behalf of the silent monks he said, “There’s too little salt and vinegar on the vegetables.”

One day Master Yunmen said to the assembly: “People learning the teaching of awakening are innumerable like the grains of sand in the Ganges River. Come on, stand out and make a statement from the tops of the hundred blades of grass.”

No one in the assembly responded.

On behalf of the silent assembly, the master said, “All inseparable.”

Once someone asked Master Yunmen, “What is the eye of the genuine teaching?”

The master said, “Everywhere!”

Another time someone asked, “What is the eye of the genuine teaching?”

Master Yunmen said, “The steam of rice gruel.”

Once someone asked Master Yunmen, “How should one act during every hour of the day such that the ancestors are not betrayed?”

The master said, “Give up your effort.”

The questioner asked, “How should I give up my effort?”

The master said, “Give up the words you just uttered.”

Someone once asked Master Yunmen, “What does ‘sitting correctly and contemplating true reality’ mean?”

The master said, “A coin lost in the river is found in the river.”

One day someone asked Master Yunmen, “What is the place from which all the awakened ones come?”

The master said, “Where the east mountains walk on the river.”

Another time someone asked, “What is the place from which all the awakened ones come?”

Master Yunmen said, “Next question, please.”

Once a monk asked Master Yunmen, “What is 'each-and-every-particle samadhi'?”

The master said, “Rice in the bowl; water in the bucket.”

One day someone asked Master Yunmen, “What is Zen?”

The Master replied, “That’s it!”

The questioner went on, “What is the Way?”

The master said, “Okay!”

Another time someone asked Master Yunmen, “What is Zen?”

The master said, “Is it alright if we get rid of this word?”

Once a monk asked Master Yunmen, “When one doe not give rise to a single thought, is there any mistake?”

The master said, “Mt. Sumeru.”

Master Yunmen was once asked by a monk, “Birth-and-death is here; how should I cope with it?”

The master said, “Where is it?”

Someone asked Master Yunmen, “I am definitely on the wrong track. Please, master, give some instruction.”

The master said, “What are you talking about?”

One day someone asked Master Yunmen, “What is the Buddha’s body?”

The master said, “A piece of dried shit.”

A monk once asked, “What is that which goes beyond the 'Truth-body'?”

Master Yunmen said, “It’s easy to talk about ‘going beyond.’ But what do you mean by 'Truth- body’?”

The monk said, “Please, master, consider my question.”

The master said, “I'm considering. But first - what can you say about the Truth-body?”

The monk said, “It’s just this.”

The master said, “That’s just something you’ve heard hanging out on the long bench in the monk’s hall. Let me ask you: can the Truth-body eat rice?”

The monk was speechless.

Once a monk asked Master Yunmen, “Will you say something that goes beyond the awakened ones and ancestral sages?”

The master said, “Sesame cake.”

When Master Yunmen saw a monk reading a scripture with the characters “dragon treasury” on it, he asked the monk, “What is it that comes out of the dragon's treasury?”

The monk had no answer.

The master said, “Ask me, I'll tell you.”

So the monk asked, and the master replied, “What comes out is a dead frog.”

One behalf of the baffled monk he said, “A fart.”

Again he said, “Steam-buns and stream-cakes.”

Once someone asked the master, “What is it like when one sees that the three realms are nothing but mind, and the myriad things are merely one's cognition?”

Master Yunmen replied, “Hiding in one's tongue.”

One day someone said to Master Yunmen, “I'm not questioning you about the core of the Buddhist doctrine, but I'd like to know what stands at the center of our own tradition.”

The master replied, “Well, you've posed your question; now quickly bow three times.”

Another time someone asked, “Master, would you please tell me what the central meaning of our tradition is?”

Master Yunmen said, “In the South there's Master Xuefeng; in the North, Master Zhaozhou.”

Once Master Yunmen said, “Do you want to know the founding masters?”

Pointing with his staff, he said, “They are jumping around on your heads! Do you want to know their eyeball? It's right under your feet!”

Then he added, “This is offering tea and food to ghosts and spirits. Nevertheless, these ghosts and spirits aren't satisfied.”

Master Yunmen was once asked, “What was Bodhidharma's purpose in coming from India?”

The master replied, “You must be hungry after such a long trip; there's gruel and rice on the long bench.”

Once someone asked Master Yunmen, “What is that which is transmitted separately from the standard teachings of the three vehicles?”

The master said, “If you don't ask me I won't answer. But if you do, I go to India in the morning and return to China in the evening.”

Once Master Yunmen went up to the Teaching Hall for a talk and said, “The world is so wide and vast; why do we put on the seven-strip robe at the sound of the bell?”

A novice once asked Master Yunmen, “It's said that one should not leave home without one's parent's consent. How would one then be able to leave home?”

The master said, “Shallow.”

The novice said, “I don't understand.”

The master said, “Deep.”

Someone once said to Master Yunmen, “Ever since I came to your Teaching seat, I just don't understand. Please give me your instruction.”

The master said, “May I lop off your head?”

Someone once asked, “If someone killed their own father and mother, they could repent in front of the Buddha. Where can you repent if you kill the Buddha and ancestors?”

Master Yunmen replied, “Clear.”

Master Yunmen once quoted a saying from the Zen poem “Faith in Mind”: “When mind does not arise, the myriad things have no fault.” Then the master said, “That's all he understood!”

Then he raised his staff and added, “Is anything amiss in the whole universe?”

Master Yunmen once held up his staff and said to the assembly, “This staff has turned into a dragon and swallowed the whole universe. The mountains, the rivers, the earth – where are they to be found?”

Someone once asked, “What is it like when everything is swallowed up in one gulp?”

Master Yunmen said, “Then I'm in your belly.”

Master Yunmen once cited Master Xuefeng's words: “The whole world is you. Yet you keep thinking that there is something else.”

Then Yunmen said, “Haven't you read in the Shurangama Sutra where it says, 'sentient beings are all upside-down; they delude themselves and chase after things'?” He added, “If they could handle things, they would be the same as the awakened ones.”

Master Yunmen once spoke to the community quoting the words of Master Danxia Tianran who said: “Every person is in the midst of the radiant light. Yet when they try to look at it, it's not seen – it seems dark and obscure.”

The master then asked, “Where is the radiant light?”

No one responded.

Master Yunmen answered on their behalf saying, “The kitchen storeroom, the main gate.”

Then he added, “I'd rather have nothing.”

At another talk Master Yunmen brought up the words of Master Sengzhao: “Within there is a jewel. It is hidden inside the human body.”

Then the master said, “It picks up the lantern in the Buddha Hall, then puts the temple's main gate on top of it. How about that?”

When no one responded, he said, “If you chase after things, your intentions are carried away.”

One day Master Yunmen brought up this story about one of his teachers:

“A monk once asked Master Yuezhou Qianfeng, 'The honored ones of the ten directions all had a single gateway to ultimate liberation. Where is this gateway?' Then Master Yuezhou drew a line in the ground with his staff and said, 'Here.'”

Master Yunmen then held up his fan and offered this comment: “This fan jumps to the uppermost heaven and hits the god Indra; when it strikes the carp of the Eastern Sea, the rain pours down in torrents. Do you understand?”

Later someone brought up the same story and asked the master, “The Honored Ones of the ten directions all had a single gateway to ultimate liberation. What is this gateway?”

Master Yunmen said, “I can't tell.”

The questioner asked, “Master, why can't you tell?”

The master said, “If you, just you, present the problem, then I can.”

Once Master Yunmen said, “I'll give you medicine according to your disease.” Then he said, “The whole world is medicine. Where are you, yourself?”

One day during a talk Master Yunmen seized his staff, banged it on the seat, and said, “All sounds are the Awakened One's voice, and all forms are the Awakened One's shape. Yet when you hold your bowl and eat your food, you hold a 'bowl-view'; when you walk you hold a 'walk-view'; and when you sit, you hold a 'sit view.' The whole bunch of you behaves this way!”

Then the master took his staff and drove them all away.

Another time Master Yunmen said, “When a patch-robed monk sees this staff, he just calls it a staff; when he walks, he just walks; and when he sits, he just sits. In all this he cannot be stirred.”

Once when Master Yunmen was giving a talk he mentioned three kinds of people: “The first awakens when hearing a talk, the second awakens when called, and the third turns around and leaves when hearing that anything is brought up. Tell me, what does turning around and going away mean?”

Answering for the assembly, he said, “The third also deserves thirty blows.”

Instructing the community, Master Yunmen said, “It is mentioned once, but then is not talked about anymore. How about that which is mentioned once?”

Answering for the silent assembly, the master said, “Though the capital Chang'an is pleasant, I wouldn't want to live there.”

One day in a talk Master Yunmen said, “I'm not asking you about before the fifteenth day (the full moon); try to say something about after the fifteenth day.”

The master answered on behalf of the assembly, “Every day is a good day.”

Once Master Yunmen questioned the community, saying, “It's been eleven days since you all entered the summer practice period. Well, have you gained an entry yet? What do you say?”

On behalf of the silent monks the master replied, “Tomorrow is the twelfth.”

Once a monk asked Master Yunmen, “Fall is beginning and the summer training period is at its end. If in the future someone were to suddenly question me, how exactly should I respond?”

The master said, “The assembly is adjourned. All of you get out of here!”

The monk asked, “What did I do wrong?”

The master said, “Give me back the money for ninety days' worth of food.”

Once Master Yunmen said, “I don't want to hear about before today, nor about after today. Tell me something just about today.”

On behalf of the silent assembly, the master said, “Now's the time!”

One day Master Yunmen said, “I'm not asking you about the ultimate truth of the teaching of Awakening. But is there someone here who knows about conventional truth?”

In place of the assembly he answered, “If I say there is such a thing I'll be in trouble with the Venerable Yunmen.”

Once Master Yunmen said, “I entangle myself in words with you every day; I can't go on till the night. Come on, ask me a question right here and now!'

In place of his listeners the master said, “I'm just afraid that Venerable Yunmen won't answer.”

One day, having entered the Teaching Hall for a formal talk, Master Yunmen sat in silence for a long time. Then he said, “This seriously compromises me,” and he got down from his seat and walked out.

Once, when Master Yunmen had finished a talk, he stood up, banged his staff on his chair, and said, “With so many creeping vine-words up to now, what place will I be banished to? Sharp ones understand, but many are being completely fooled by me.”

Then he said, “Putting frost on top of snow.”

One day Master Yunmen said, “What is a statement that doesn't fool people?”

In place of his listeners he said, “Don't tell me that this was one that did!'

One day in the Teaching Hall, after a long silence, Master Yunmen said, “I'm making a terrible fool of myself.” Then he got down from his seat.

On his way out, speaking for the assembly, he said, “Aha...not just us!”

Once Master Yunmen said to a monk, “The whole universe is a house. How about the master of the house?”

The monk had no answer.

The master said, “Ask me, I'll tell you.”

The monk asked , and the master said, “He has passed away.”

Then the master added, “How many people has he deceived?”

Someone once asked Master Yunmen, “How is it when the tree withers and the leaves fall?”

The master said, “The whole body exposed in the golden autumn wind.”

One day someone asked Master Yunmen, “What is the meaning of the teaching?”

The master said, “The answer is not finished yet.”

![]()

YUN-MEN

Translated by Thomas Cleary

In: The five houses of Zen, 1997

Yun-men was one of the most brilliant and abstruse of all the classical masters. His talks include numerous examples of quotations and variations of existing Zen lore, and meditation on Zen stories and sayings was clearly one of the methods of his school. Tradition has it, nevertheless, that Yun-men forbade his followers to record his own words, so that they could not memorize sayings at the expense of direct experience of reality. The record we nonetheless have of Yun-men, more extensive than that of other original masters of the Five Houses, is said to have been surreptitiously written down by a longtime disciple on a robe made of paper. Such robes were sometimes worn by monks as an exercise in remembrance of the perishability of things. This anthology presents several of Yun-men's lectures, in which he gives orientation for Zen studies in relatively straightforward terms.

Sayings

THE OPPORTUNITY to preach the Way is certainly hard to handle; even if you accord with it in a single saying, this is still fragmentation. If you go on at random, that is even more useless.

Now then, there are divisions within the vehicles of the Teaching: the precepts are for moral studies, the scriptures are for learning concentration, and the treatises are for learning wisdom. The Three Baskets, Five Vehicles, Five Times, and Eight Teachings each have their goal. But even if you directly understand the complete immediate teaching of the One Vehicle, which is so hard to understand, this is still far from Zen realization.

In Zen, even if you present your state in a phrase, this is still uselessly bothering to tarry in thought. Zen methods, with their interactive techniques, have countless variations and differences; if you try to get ahead, your mistake lies in pursuing the expressions of others.

What about the perennial concern? Can you call this complete, can you call it immediate? Can you call it mundane or transcendental? Better not misconstrue this! When you hear me speaking this way, do not immediately turn to where there is neither completeness nor immediateness to figure and calculate.

Here, it is necessary for you to be the one to realize it; do not present sayings from a teacher, imitation sayings, or calculated sayings everywhere you go, making them out to be your own understanding.

Do not misunderstand. Right now, what is the matter?

Better not say I’m fooling you today. To begin with, I have no choice but to make a fuss in front of you, but if I were seen by someone with clear eyes, I’d be a laughingstock. Right now I can’t avoid it, so let me ask you all: What has ever been the matter? What do you lack?

Even if I tell you there’s nothing the matter, I’ve already buried you, and yet you must arrive at this state before you will realize it. And don’t run off at the mouth asking questions at random; as long as your own mind is unclear, you still have a lot of work to do in the future.

If your faculties and thoughts work slowly, then for now examine the methods and techniques set up by the ancients, to see what their principles are.

Do you want to attain understanding? The subjective ideas you yourself have been entertaining for measureless eons are so dense and thick that when you hear someone giving an explanation, you immediately conceive doubts and ask about the Buddha, ask about the Teaching, ask about transcendence, ask about accommodation. As you seek understanding, you become further estranged from it.

You miss it the moment you try to set your mind on it; how much more so when you talk! Would that mean that not trying to set the mind on it is right? What else is the matter? Take care!

If I were to bring up a single saying that enabled you to attain understanding immediately, this would already be scattering filth on your heads. Even if you understand the whole world all at once when a single hair is picked up, this is gouging out flesh and making a wound. Nevertheless, you must actually arrive at this state before you realize this. If you have not, then don’t try to fake it in the meantime.

What you must do is step back and figure out your own standpoint: what logic is there to it?

There really is nothing at all to give you to understand, or to give you to wonder about, because each of you has your own business. When the great function appears, it does not take any effort on your part; now you are no different from the Zen masters and buddhas. It’s just that your roots of faith are shallow and thin, while your bad habits are dense and thick.

Suddenly you get all excited and go on long journeys with your bowls and bags; why do you undergo such inconvenience? What insufficiency is there in you? You are adults; who has no lot? Even when you attain understanding individually on your own, this is still not being on top of things; so you shouldn’t accept the deceptions of others or the judgments of others.

The minute you see some old monk open his mouth, you should shut him right up. Instead you act like green flies on a pile of manure, struggling to consume it. Gathering together in groups for discussion, you bore others miserably.

The ancients would utter a saying or half a statement for particular occasions, because of the helplessness of people like you, in order to open up ways of entry for you. If you know this, put them to one side and apply a bit of your own power; haven’t you a little familiarity?

Alas, time does not wait for anyone; when you breathe out, there’s no guarantee you’ll breathe in again. What other body and mind do you have to employ at leisure somewhere else? You simply must pay attention! Take care.

Take the whole universe all at once and put it on your eyelashes.

When you hear me talk this way, you might come up excitedly and give me a slap, but relax for now and examine carefully the question of whether such a thing exists or not and what it means.

Even if you understand this, if you run into a member of a Zen school you’ll probably get your legs broken.

If you are an independent individual, when you hear someone say that an old adept is teaching somewhere, you will spit right in that person’s face for polluting your ears and eyes.

If you do not have this ability, as soon as you hear someone mention something like this, you will immediately accept it, so that you have already fallen into the secondary. Don’t you see how Master Te-shan used to haul out his staff the moment he saw monks enter his gate, and chase them out? When Master Mu-chou saw monks come through his gate, he would say, “The issue is at hand; I ought to give you a thrashing!”

How about the rest? The general run of thieving phonies eat up the spit of other people, memorizing a bunch of trash, a load of garbage, then running off at the mouth like asses wherever they go, boasting that they can pose questions on five or ten sayings. Even if you can pose questions from morning till night and give answers from night till morning, on until the end of time, will you ever even dream of seeing? Where is the empowerment for people? Whenever someone gives a feast for Zen monks, people like this also say they’ve gotten food to eat. How are they worth talking to? Someday, in the presence of death, your verbal explanations will not be accepted.

One who has attained may spend the days following the group in another’s house, but if you have not attained, don’t be a faker! It will not do to pass the time taking it easy; you should be most thoroughly attentive.

The ancients had a lot of complex ways of helping out. For example, Master Hsueh-feng said, “The whole earth is you!” Master Chia-shan said, “Find me in the hundred grasses; recognize the emperor in the bustling marketplace.” Luo-p’u said, “As soon as a single atom comes into existence, the whole earth is contained within it. There’s a lion in every hair, and this is true of the whole body.” Take these up and think them over, again and again; eventually, after a long, long time, you will naturally find a way to penetrate.

No one can do this task for you; it is up to each individual alone. The old masters who emerge in the world just act as witnesses to your understanding. If you have penetrated, a little bit of reasoning won’t confuse you; if you have really not attained yet, then even the use of expedients to stimulate you won’t work.

All of you have worn out footgear traveling around, having left your mentors and elders, your fathers and mothers. You must apply some perceptive power before you will attain realization. If you have no penetration, if you should run into someone with really effective methods who ungrudgingly devotes life to going into the mud and water to help others, someone who is worth associating with and who disrupts complacency, then hang up your bowls and bags for ten or twenty years to attain penetration.

Don’t worry that you might not succeed, because even if you don’t get it in the present life, you will still not lose your humanity in the future life. Thus you will also save energy in this quest; you will not betray your whole life in vain, nor will you betray those who supported you, your mentors and elders, your fathers and mothers.

You must be attentive. Don’t waste time traveling around the countryside, passing a winter here and a summer there, enjoying the landscape, seeking enjoyment, plenty of food, and readily available clothing and utensils. What a pain! Counting on that peck of rice, you lose six months’ provisions. What is the benefit in journeys like this? How can you digest even a single vegetable leaf, or even a grain of rice, given by credulous almsgivers?

You must see for yourself that there is no one to substitute for you, and time does not wait for anyone. One day the light of your eyes will fall to the ground; how can you prevent that from happening? Do not be like lobsters dropped in boiling water, hands and feet thrashing. There will be no room for you to be fakers talking big talk.

Don’t waste the time idly. Once you have lost humanity, you can never restore it. This is not a small matter. Do not rely on the immediate present. Even a worldly man said, “If you hear the Way in the morning, it would be all right to die that night”—then what about ascetics like us—what should we practice? You should really be diligent. Take care.

It is obvious that the times are decadent; we are at the tail end of the age of imitation. These days monks go north saying they are going to bow to Manjushri and go south saying they are going to visit Mount Heng. Those who go on journeys like this are mendicants only in name, vainly consuming the alms of the credulous.

What a pain! When you ask them a question, they are totally in the dark. They just pass the days suiting their temperament. If there are some of you who have mislearned a lot, memorizing manners of speech, seeking similar sayings wherever you go for the approval of the elder residents, slighting the high-minded, acting in ways that spiritually impoverish you, then do not say, when death comes knocking at your door, that no one told you.

If you are a beginner, you should activate your spirit and not vainly memorize sayings. A lot of falsehood is not as good as a little truth; ultimately you will only cheat yourself.

![]()

YUNMEN WENYAN

IN: Zen's Chinese heritage: the masters and their teachings

by Andy Ferguson

Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2000. pp. 283-288.

YUNMEN WENYAN (864–949) was a disciple of both Muzhou Daoming and Xuefeng Yicun. Although he first attained realization under Muzhou, he is generally recognized as a Dharma heir of Xuefeng. He came from ancient Jiaxing (located midway between the modern cities of Shanghai and Hangzhou). As a young man, he first entered monastic life under a Vinaya master named Zhicheng. After serving as that teacher’s attendant for many years, Yunmen exhausted the teachings of the Vinaya and set off to study elsewhere. Eventually, he studied with Muzhou Daoming.

The Wudeng Huiyuan provides an account of Yunmen’s enlightenment under Zen master Muzhou.

When Muzhou heard Yunmen coming he closed the door to his room. Yunmen knocked on the door.

Muzhou said, “Who is it?”

Yunmen said, “It’s me.”

Muzhou said, “What do you want?”

Yunmen said, “I’m not clear about my life. I’d like the master to give me some instruction.”

Muzhou then opened the door and, taking a look at Yunmen, closed it again.

Yunmen knocked on the door in this manner three days in a row. On the third day when Muzhou opened the door, Yunmen stuck his foot in the doorway.

Muzhou grabbed Yunmen and yelled, “Speak! Speak!”

When Yunmen began to speak, Muzhou gave him a shove and said, “Too late!”

Muzhou then slammed the door, catching and breaking Yunmen’s foot. At that moment, Yunmen experienced enlightenment.

Muzhou directed Yunmen to go see Xuefeng. When Yunmen arrived at a village at the foot of Mt. Xue, he encountered a monk.

Yunmen asked him, “Are you going back up the mountain today?”

The monk said, “Yes.”

Yunmen said, “Please take a question to ask the abbot. But you mustn’t tell him it’s from someone else.”

The monk said, “Okay.”

Yunmen said, “When you go to the temple, wait until the moment when all the monks have assembled and the abbot has ascended the Dharma seat. Then step forward, grasp your hands, and say, ‘There’s an iron cangue on this old fellow’s head. Why not remove it?’”