ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

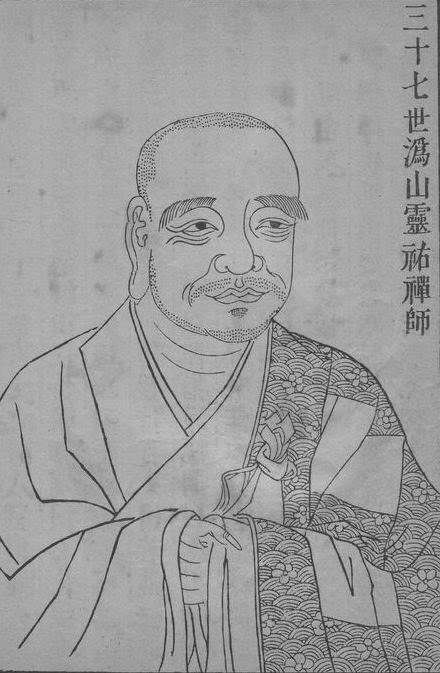

溈山靈祐 Guishan Lingyou (771-853)

aka 大潙靈祐 Dawei Lingyou;

潙山靈祐 Weishan Lingyou

溈山靈祐禪師語錄 Guishan Lingyou chanshi yulu

*who, with his disciple 仰山慧寂 Yang-shan Hui-chi (Japanese, Kyozan Ejaku) (814-890), founded the 溈仰宗 Kuei-yang Tsung (Japanese, Igyo-shu), a school soon absorbed into the Lin-chi Tsung (Japanese, Rinzai-shu).

(Rōmaji:) Isan Reiyū zenji goroku

(English:) The recorded conversations of Zen master Lingyou of Guishan

(Magyar:) Kuj-san Ling-ju zen mester összegyűjtött mondásai

Taisho No. 1989 (Vol. XLVII, pp. 577a-582a.6)

溈山警策 Guishan jingce

(Rōmaji:) Isan kyōsaku

(English:) Guishan's admonitions

Jacques Gernet:

Les entretiens du Maître Ling-yeou du Kouei-chan (771-853)

Bulletin de l'Ecole Française d'Extrême-Orient, XLV (1951), No. 1, 65-70.

http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/befeo_0336-1519_1951_num_45_1_5510

The translation of eight episodes chosen from here and there in the text and comprising about one-sixth of the original Chinese, with notes and explanatory remarks in Gernet's scholarly style.

Les procédés de discussion dans la secte bouddhiste du dhyāna sont étranges. Mais ce n'est pas sans raison. Ils visent à donner une révélation brusque et inattendue de la nature propre. A ce titre, ils nous éclairent sur les moyens (upāya) employés; les actes, même les plus profanes et les plus ordinaires, sont la matière même de la méditation, car tout ramène chez le vrai Saint à l'absolu. Mais ils montrent encore, et peut-être avec plus d'évidence que la poésie, que les modes d'expression en Chine sont radicalement différents des nôtres.

Nous avons traduit ci-dessous quelques kong-ngan [1], sujets de méditation pour ceux qui cherchent le Chemin, en essayant, peut-être à tort, de les interpréter, car la vérité ultime est inexprimable. « Efforcez-vous !», disent les maîtres de dhyāna à leurs disciples sans leur ménager les peines de l'esprit ou du corps. Les coups de bâton et les réflexions ardues mènent également à l'illumination. L'obscurité est finalement source de lumière.

On nous excusera de ne pas avoir tout traduit de ces entretiens du maître Ling-yeou [2] : seuls les initiés sont autorisés à pénétrer les mystères. Mais les courts passages que nous avons cru élucider nous ont paru assez caractéristiques pour mériter une traduction.

[1] Certains kong-ngan se retrouvent plusieurs fois dans des versions assez différentes pour le fonds et pour la forme selon les textes. Une étude de ces thèmes de méditation montrerait peut- être comment le dhyàna en Chine a tendu, au cours de son évolution, à devenir un exercice artificiel où la subtilité des allusions a fini par supplanter la mystique et l'enthousiasme des premiers temps.

[2] Taishô issaikyô, n° 1989. Une biographie du maître de dhyāna Ling-yeou se trouve au Song kао seng tchouan, T. 2061, xi, 777 b-c 11. Ling-yeou était d'une famille de Tch'ang-k'i, ville au sud de l'actuel Hia-p'ou-hien au Fou-kien. Entré en religion à 14 ans, il eut pour maître un nommé Fa-tch'ang. Il étudia le Petit et le Grand Véhicule au Long-hing-sseu de Hang-tcheou (actuel Hang-hien au Tchô-kiang). A 22 ans, il vient se joindre aux disciples du maître Houai-hai de la montagne Po-tchang, à Siu-wou dans le Kiang-si. Un nommé Sseu-ma, venu du Hou-nan, révèle au maître du Po-tchang l'existence du mont Kouei, «lieu convenable à un grand Saint» (Le mont Kouei n'est pas mentionné dans le Tchong kouo ti ming ta ts'eu tien, mais doit vraisemblablement son nom à la rivière Kouei qui a sa source près de Yi-yang-hien au Hou-nan). Houai-hai décide que Ling-yeou s'y établira (il semble que les maîtres de dhyāna aient eu l'habitude de fixer à leurs successeurs le lieu de leur résidence). Peu à peu, ce désert habité seulement par de troupes de singes, se peuple de disciples attirés par l'enseignement de Ling-yeou. Le maître y demeure jusqu'à sa mort, le 20 février 853, à l'âge de 82 ans.

Yun-yen [1] étant venu au Kouei-chan, le maître lui dit : «J'ai appris que le Vénérable Yun-yen jouait avec un lion au Yo-chan [2]. Est-ce vrai? — Oui, dit Yun- yen. — Jouiez-vous constamment avec lui ou y avait-il des moments où vous le laissiez tranquille? — Selon mon désir, je jouais avec lui ou le laissais tranquille. — Lorsque vous le laissiez tranquille, où était-il? — Je le laissais, je le laissais, et voilà tout ! [3]»

* * *

Le supplément de l'édition de Kyoto du Tripitaka contient une série de poèmes intitulés Che nieou ťou song [4]. Chacun d'eux est une suite de quatrains en vers de sept mots qui représentent le dressage d'un bœuf par un pâtre. Hou Wen-houan des Ming nous dit (p. 461a chang) que le pâtre, c'est l'homme et le bœuf, c'est l'esprit: «les dix tableaux sur le bœuf sont une des comparaisons utilisées par la secte du dhyâna pour exercer les esprits et les faire parvenir au Chemin ». Le bœuf est d'abord dompté avec peine, mais il s'accoutume peu à peu à son maître et bientôt n'a plus besoin de laisse ni de fouet. Enfin, le pâtre et la bête s'oublient mutuellement : « Le bœuf blanc reste toujours au milieu des nuages blancs. L'homme lui-même est sans esprit (wou sin), le bœuf aussi. La lune traverse les nuages blancs et l'ombre des nuages est blanche. Nuages blancs, lune brillante sans effort vont de l'est à l'ouest». Le bœuf disparaît ensuite. C'est le rayonnement solitaire (tou tchao) : «Le bœuf n'est plus en aucun lieu. Le pâtre est tranquille. Un nuage solitaire flotte entre les cimes vertes. » Le lion de Yun-yen ressemble fort au bœuf que représente la série des Che nieou t'ou song. On peut remarquer d'autre part que le thème du Vénérable apprivoisant les bêtes féroces par la puissance de sa sainteté est très fréquent dans les biographies de moines bouddhistes.

* * *

A la cueillette du thé, le maître dit à Yang-chan [5] : «Tout le jour à cueillir le thé, je n'entends que votre voix, je ne vois pas votre corps.» Yang-chan secoua l'arbre. «Vous n'avez, reprit le maître, que l'activité, vous n'avez pas la substance.

[1] Cf. T. 2061, xi, 775 b 8-14. Le maître T'an-cheng du monastère Yun-yen était originaire de Kien-tch'ang (dans la préfecture de Tchong-ling dont le siège se trouvait à 60 li au nord-est de Tsin-hien-hien au Kiang-si). Il fut pendant dix-neuf ans au service du maître Houai-hai du Po-tchang et mourut en 829.

[2] La montagne Yo se trouvait dans la préfecture de Li (actuel Li-hien, au Hou-nan).

[3] T. 1989, p. 577 c 19-22.

[4] Suppl. de Kyoto, Bi, xviii, 5, p. 459-470. Ces poèmes ont été recueillis les uns par Che-yuan des Song, les autres par Hou Wen-houan, d'autres enfin par un auteur inconnu. Cf. Inventaire du Fonds chinois de la Bibliothèque de l'EFE0, n° 1063-5. Dans ses Notes sinologiques (BEFEO, 1904, p. 75), E. Chavannes mentionne un Nieou-sin-sseu , au nord du Ngo-mei-chan au Sseu-tch'ouan et traduit «Temple du Cœur de bœuf». (Cf. k. I du Wou tch'ouan-lou) Il est probable que l'expression nieou sin est une allusion à la représentation de l'esprit sous la forme d'un bœuf telle qu'on la trouve dans les Che nieou ťou song et qu'il faut comprendre «temple de l'esprit conçu sous la forme d'un bœuf». La question se pose de savoir à quand remonte cette figuration et d'où elle vient. Il est vrai qu'il existe un Fang nieou king, traduit par Kumârajïva, où l'on trouve une comparaison entre la conduite d'un pâtre et celle du bhiksu (T. 123 ou Edition de Tôkyô, xii, 4. Versions parallèles dans l'Ekottarāgama et dans le Samyuktāgama), mais il se pourrait bien que ce thème de l'apprivoisement d'une bête sauvage fût d'origine taoïste et non pas bouddhique.

[5] Cf. T. 2061, xii, 783 a, 27-b, 16. Le maître de dhyâna Houei-tsi, connu aussi sous le nom de Yang-chan, était originaire de Tchen-tch'ang (actuel Nan-hiong-hien au Kouang-tong). Ses parents hésitant à le laisser entrer en religion, il se coupa l'annulaire et l'auriculaire de la main gauche. «Puissé-je, dit-il, répondre ainsi à la peine que vous vous êtes donnée pour moi.»

— Je ne sais, dit Yang-chan, ce qu'il en est pour vous, Maître.» Le maître resta un long moment sans répondre. «Vous n'avez, dit alors Yang-chan, que la substance, vous n'avez pas l'activité. — Je vous donnerai, dit Ling-yeou, trente coups de bâton [1].»

Le corps de Yang-chan symbolise ici la substance de l'absolu (tathatā), sa voix l'activité (prayojana) de l'absolu en tant que prédication. Le vrai Saint possède l'une et l'autre. Penché sur son arbre, le maître demande au disciple ce qu'il entend par activité, mais lorsque Yang-chan secoue l'arbre pour toute réponse, ce n'est encore là qu'une manifestation d'activité. Cette réponse ne convient pas. Au contraire, le silence de Ling-yeou fait dire au disciple que son maître ne possède que la substance de l'absolu.

* * *

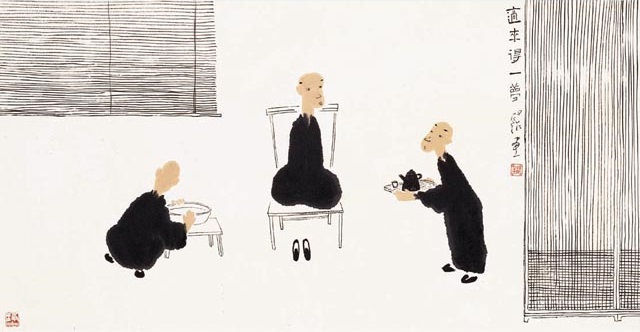

Ling-yeou dormait et Yang-chan vint pour le saluer. Le maître se tourna alors vers le mur. «Pourquoi faites-vous cela?» demanda Yang-chan. Le maître se leva et dit : «Je viens de faire un rêve. Voyez un peu pour moi ce qu'il en est.» Yang-chan prit alors un baquet d'eau et le donna au maître pour qu'il se lavât le visage. Peu de temps après, Hiang-yen [2] vint aussi saluer le maître, «Je viens de faire un rêve, dit Ling-yeou. Expliquez-moi ce qu'il en est.» Alors Hiang-yen fît chauffer une tasse de thé [3] et l'apporta, «Ces deux disciples, dit le Maître, ont une vue qui dépasse celle de Çāriputra [4]!»

Tous les phénomènes, tous les dharma conditionnés (samskrta) ne sont que des apparitions de rêve. C'est au moment où l'on a rejeté tout le causal et toute notion que l'on voit sa nature propre. Le baquet d'eau et la tasse de thé sont ici les symboles ďune purification intérieure et extérieure.

* * *

Che-chouang [5] vint au Kouei-chan pour être intendant du riz (mi-t'eou). Un jour qu'il passait des grains au crible, le maître lui dit : «Il ne faut pas disperser les dons des maîtres d'aumône (dānapati). — Je ne les disperse pas, répondit Che-chouang. Le maître ramassa à terre un grain : «Tu dis que tu ne les disperses pas, mais qu'est ceci?» Che-chouang n'eut rien à répondre. «Ne fais pas fi de ce grain, reprit le maître, car des centaines de milliers de grains peuvent naître de ce grain unique. — Oui, dit Che-chouang, des centaines de milliers de grains peuvent en naître,

A 16 ans, il fut disciple du maître de dhyâna T'ong, au Nan-houa-sseu et, à 18 ans, celui de Tan-yuan. Par la suite, il demeura, pendant treize ou quatorze ans, auprès de Ling-yeou, au Kouei-chan.

[1] Taishô, n° 1989, p. 678 b, 8-12.

[2] Cf. Taishô, n° 2061, XIII, 785 a, 26 b, 5. Hiang-yen, autre nom Tche-hien, était de Ts'ing-tcheou (à 60 li de Nan-p'ing-hien au Fou-kien). Le Song kao seng tchouan ne fait que reproduire en les abrégeant les données du n° 1989 du Taishô.

[3] façon de préparer le thé à l'époque des T'ang et des Song (Ts'eu-hai).

[4] Taishô, n° 1989, p. 579 b, 29-c 5.

(5) Cf. Taishô, n° 2061, xii, 780 a, 14. K'ing-tchou, maître de la montagne Che-chouang, dans la commanderie de Tch'ang-cha (moitié est du Hou-nan), fut à 12 ans disciple de Chao-louan, à 22 ans il reçut l'ordination au pic de Song (Ho-nan) et, après avoir étudié le vinaya à Lo-yang, il alla au pic du Sud (Heng-chan au Hou-nan) et pénétra au mont Kouei (résidence de Ling-yeou). Il se fixa par la suite au mont Che-chouang où il mourut en 888 à l'âge de 81 ans.

mais je ne sais pas d'où naît ce grain.» Le maître retourna à sa cellule en riant très fort [1].

La substance des choses est insaisissable (anupalabhya) et non née (anutpanna).

* * *

Un moine demanda : «Qu'est-ce que le Chemin? — C'est l'absence d'esprit (wou-sin), dit le maître. — Je ne comprends pas. — Pour comprendre, le mieux, c'est de saisir l'incompréhensible. — Qu'est-ce que l'incompréhensible? — Ce n'est que vous-même et non les autres.» Le maître reprit : «Gens de maintenant, saisissez et incorporez-vous tout de suite l'incompréhensible. C'est cela justement qu'est votre propre esprit, c'est cela justement qu'est le Buddha qui est en vous. Si vous acquérez de l'extérieur une connaissance ou une vue et que vous en fassiez le Chemin de dhyāna, cela n'aura aucun rapport [avec la vérité innée en vous]. Cela s'appelle amener les immondices au-dedans et non pas les chasser au dehors. C'est salir le champ de votre esprit [2]. C'est pourquoi je dis que ce n'est pas là le Chemin [3].»

* * *

Un moine avait demandé à Ling-yeou quelle était l'intention du patriarche Bodhidharma en venant en Orient. Le maître leva verticalement son plumeau. Par la suite, ce moine rencontra le tch'ang-che [4] Wang qui lui demanda quels avaient été les propos du [maître du] Kouei-chan les jours derniers. Le moine lui rapporta l'entretien précédent, «Quelle est, demanda Wang, votre façon de discuter à vous, frères de là-bas? — On a recours au sensible pour faire voir l'esprit foncier. On s'attache aux choses concrètes pour mettre en lumière le principe absolu. — Ce n'est pas cette méthode [qui convient], dit le tch'ang-che. Retournez vite, supérieur. C'est le mieux. Je me permets d'envoyer une lettre à votre maître.» Le moine prit la lettre et s'en retourna la présenter à Ling-yeou. Le maître l'ouvrit et vit le dessin d'un cercle où était inscrit le caractère du soleil. «Qui sait, dit-il, s'il n'y a pas, à plus de mille li d'ici, un homme qui connaisse mes pensées les plus profondes [5]?» Yang-chan, qui se tenait à ses côtés, dit alors : «Quand cela serait, cet homme n'est tout de même qu'un profane. — Qu'avez-vous encore [à dire]? dit Ling-yeou». Yang-chan dessina alors un cercle, y inscrivit le caractère «soleil» et effaça le tout avec son pied. Le maître se mit à rire violemment [6].

Le cercle dessiné représente la vacuité et la quiétude parfaites de l'esprit. Le soleil est l'image de la sapience (prajnā) qui illumine tous les mondes de ses rayons. En effaçant le dessin qu'il a reproduit, Yang-chan nie que dans l'absolu il y ait place même pour une représentation aussi simple.

[1] Taishô, n° 1989, p. 678 a, 20-25.

[2] On trouve plus fréquemment l'expression, terre de l'esprit. Cf. le T'an king [Taishô, n° 2007 et 2008), ouvrage du VIII. siècle qui relate des prédications du maître Houei-neng, sixième patriarche de l'école du dhyâna.

[3] Taishô, n° 1989, p. 581 b, 21-26.

[4] Fonctionnaire constamment à la disposition d'un prince. Cf. R. des Rotours, Traité des fonctionnaires et de l'armée, Leiden, 1947.

[5] allusion à un passage du chapitre v du Lie-tseu : «Quand Po-ya touchait son luth et qu'il fixait sa pensée sur de hautes montagnes, Tchong Tseu-k'i disait : «Quelles altitudes majestueuses ! C'est le T'ai-chan !» S'il fixait sa pensée sur le courant d'un fleuve, son ami disait : «Quels «flots abondants ! C'est le Kiang ou le Ho !» Quand Tchong Tseu-k'i mourut, Po-ya brisa les cordes de son luth parce que personne ne pouvait désormais comprendre le sens de sa musique.»

[6] Taishô n° 1989, p. 579 c, 9-18.

* * *

Un jour, Ling-yeou était debout auprès de son maître. «Qui est-ce ? demanda Po-tchang [1]. — C'est moi. — Cherche dans le fourneau s'il y a des braises», dit le maître. Ling-yeou chercha et répondit qu'il n'y en avait pas. Po-tchang se leva lui-même et en cherchant au fond il en trouva un peu. «Tu dis qu'il n'y a pas de braises, dit-il en montrant celles qu'il avait trouvées à Ling-yeou, mais qu'est ceci?» Ling-yeou eut alors une illumination et salua en s'excusant.

Les cendres qui recouvrent le feu sont comme les passions (kleça) qui nous empêchent de voir notre nature foncière.

Ling-yeou exposa ce qu'il avait compris. «Cette compréhension, dit Po-tchang, n'est qu'à l'image d'une route qui bifurque pour peu de temps, «Qui veut connaître, dit le sûtra, le sens de la nature de Buddha doit considérer les circonstances et les conditions». Lorsque les circonstances arrivent, on est alors comme un égaré qui soudain comprend, comme un oublieux qui soudain se souvient. Il faut discerner en soi ce qui est propre à soi-même et non chercher à l'obtenir des autres. Aussi, le patriarche disait-il : «Avoir été illuminé, c'est comme ne pas l'avoir été.»

[Dans l'absolu] il n'y a ni esprit ni dharma. Il n'y a qu'absence d'erreur. Profanes et Saints ont un même esprit. L'esprit foncier est de lui-même présent et parfait en nous dès l'origine. Puisque tu as ainsi été illuminé, garde-toi avec soin.»

L'illumination est d'un caractère temporaire, fragile et inconsistant. Il faut donc rester sans cesse sur ses gardes et se tenir aux brefs éclairs d'intelligence que l'on a.

* * *

«J'ai entendu dire, dit le maître à Hiang-yen, que du temps où vous étiez chez l'ancien maître du Po-tchang, à une question vous donniez dix réponses, à dix questions cent réponses. Telles sont votre intelligence et votre pénétration! Mais votre opinion et vos pensées sur la racine des renaissances et des morts et sur ce qu'il y a avant même la conception, quelles sont-elles? Dites-nous donc un mot à ce sujet». A cette question, Hiang-yen fut aussitôt troublé et retourna à sa cellule pour y prendre les écrits qu'il lisait ordinairement. Il chercha depuis le début une phrase qu'il pût répondre, mais en vain. «Faire le dessin d'une galette, dit-il en soupirant, cela ne peut satisfaire la faim!» et il pria le maître à plusieurs reprises de lui dire le mot qui trancherait [cette énigme]. «Si je vous le dis, répondit le maître, vous m'insulterez ensuite. Ce que je vous dirais me serait particulier et de toute façon inadéquat à votre propre cas». Hiang-yen prit alors les écrits qu'il avait autrefois l'habitude de lire et les brûla en disant : «De toute cette vie, en vérité je n'ai pas étudié la loi bouddhique. Faisons-nous pour longtemps moine de soupe et de riz (c'est-à-dire menons une vie de moine inutile et stupide) pour éviter d'asservir notre esprit [2]». Il prit congé du maître et se rendit tout droit à Nan-yang [3],

[1] Cf. Taishô, n° 2061, x, 770 c, 14-771 a, 6. Houai-hai, plus connu sous le nom de maître du Po-tchang, était originaire du Fou-kien. Il fut élève de Ta-tsi à Nan-k'ang (au sud-ouest de Kan-hien au Kiang-si). Il résida ensuite au mont Po-tchang dans la sous- préfecture de Sin-wou (actuel Fong-sin-hien, Kiang-si). Houai-hai est le fondateur d'une discipline spéciale au dhyāna : «C'est à partir de Houai-hai que l'école du dhyāna eut des règles de discipline indépendantes» (p. 771 a, 3-4). Houai-hai mourut le 10 février 814, à l'âge de 94 ans. En 821, Mou-tsong lui octroya le nom posthume de maître de dhyāna Ta-tche.

[2] Cette поtiоп est taoïste.

[3] Dans le sud du Ho-nan.

où il vit les souvenirs qu'y avait laissés le maître de royaume Tchong [1] et il se fixa à cet endroit. Un jour qu'il sarclait les mauvaises herbes et les arbustes, il jeta par hasard une brique. Sous le choc, un bambou résonna et soudain Hiang-yen fut illuminé.

Voilà un bel exemple du processus de l'illumination. La question du maître détermine un changement total dans le genre de vie de Hiang-yen. La réponse ne peut être obtenue par un raisonnement logique : il faut cultiver son inconscient. L'illumination est subite, totale, imprévisible : un mot, un cri ou un simple bruit suffisent à la provoquer.

Il revint alors au Kouei-chan. Après s'être lavé et avoir brûlé de l'encens, il salua de loin le maître : «Votre bonté, dit-il, dépasse celle d'un père et d'une mère. Si, sur le moment, vous aviez tranché pour moi cette énigme, comment l'événement présent se serait-il produit?» Il eut alors cette stance :

«Un heurt et j'oubliais mon savoir, dès lors, je n'eus plus besoin des pratiques.

Dans mes démarches, je glorifiai la voie ancienne [des Buddha]. Je ne tomberai plus dans des pièges qui me laisseront muet [2]

En nul lieu je ne laisserai de traces [3]. Hors du son et du sensible, (je me tiendrai) dans les quatre attitudes. [4]

Tous ceux qui, partout, ont pénétré le Chemin, diront que je suis un homme supérieur.»

Ayant entendu ces mots, le maître dit à Yang-chan : «Ce disciple a vraiment pénétré le Chemin! — Ces vers, répondit Yang-chan, sont [peut-être] la création artificielle d'une pensée réfléchie. Attendez que j'aie vu moi-même ce qu'il en est.» Yang-chan rencontra par la suite Hiang-yen et lui dit : «Notre maître a fait votre éloge parce que vous avez eu l'illumination, cette affaire de tant d'importance. Expliquez-moi un peu cela pour voir.» Hiang-yen récita de nouveau sa stance, «Ces vers, dit Yang-chan, sont l'effet d'une pensée attachée encore aux anciennes imprégnations (vasanâ). Si vous avez eu l'illumination correcte, dites encore quelques mots pour voir.» Hiang-yen composa alors cette nouvelle stance :

«L'aппéе passée, ma pauvreté n'était pas encore véritable, c'est seulement de cette année qu'elle est pauvreté.

L'année passée, dans ma pauvreté, j'avais encore l'espace de la pointe d'une alêne, cette année, dans ma pauvreté, je n'ai même plus cet espace.»

«Voilà, dit Yang-chan, le dhyāna du Tathāgata [5] !» [6]

[1] On ne sait pas qui est ce maître de royaume Tchong.

[2]

[3] C'est-à-dire je m'ébattrai dans ce monde librement.

[4] Cf. Vimalakïrti, Taishô, n° 475, k. chang, 5З9 c, 21 : «C'est le fait de manifester des actes profanes sans quitter la loi qui est accroupissement dans le calme . . . Accéder au nirvana sans trancher les passions, voilà qui est accroupissement dans le calme.»

[5] Cf. Chen-houei ho-chang yi-tsi, éd. Hou Che, Chang-hai, 19З0, p. 145 : «Cette phrase : «Lorsque l'être et le non-être sont expulsés l'un et l'autre, le Chemin du milieu disparaît également» s'applique à l'absence de pensée. L'absence de pensée, c'est la pensée instantanée (atemporelle), la pensée instantanée, c'est l'omniscience, c'est la très profonde prajnâpâramitâ et la très profonde prajnâpâramitâ, c'est le dhyâna du Tathâgata.»

[6] Taishô, n° 1989, p. 580 b, 8-29.

![]()

KUEI-SHAN LING-YU (771-853)

Great Action and Great Potentiality

(From The Transmission of the Lamp, Chüan 9)

Original Teachings of Ch'an Buddhism. Translated by Chang Chung-yuan. New York: Random House, 1969. pp. 200-208.

CH'AN Master Kuei-5shan Ling-yu of T'an-chou6 was a native

of Chang-ch'i in Fu-chou.7 His original surname was Chao.

When he was fifteen he left his parents and became a monk.

In the Chien-shan Monastery in his native town, he studied under

the Vinaya master Fa-ch'ang and had his head shaved. Later he

was ordained at the Lung-hsing Monastery in Hang-chou,8 where

he devoted himself to the study of the sutras and vinayas of both

the Mahayana and the Hinayana. At the age of twenty-three he

traveled to Kiangsi, where he visited Master Po-chang Huai-hai. As

soon as the master saw his visitor he gave him permission to study

in the temple, and thereafter Kuei-shan became Po-chang's leading

disciple.

One day Kuei-shan was attending Master Po-chang, who asked

him:

"Who are you?"

"I am Ling-yu."

"Will you poke the fire pot and find out whether there is some

burning charcoal in it?" said Po-chang.

Kuei-shan did so, and then said, "There is no burning charcoal."

Master Po-chang rose from his seat. Poking deep into the fire pot,

he extracted a small glowing piece of charcoal which he showed to

Kuei-shan, saying, "Is this not a burning piece?"

At this, Kuei-shan was awakened. Thereupon he made a profound

bow and told Po-chang what had happened. However, Pochang

explained:

"The method that I used just now was only for this occasion. It

is not the usual approach. The Sutra says, 'To behold the Buddha-nature

one must wait for the right moment and the right conditions.

When the time comes, one is awakened as from a dream. It is as if

one's memory recalls something long forgotten. One realizes that

what is obtained is one's own and not from outside one's self.' Thus

an ancient patriarch said, 'After enlightenment one is still the same

as one was before. There is no mind and there is no Dharma.'9 One

is simply free from unreality and delusion. The mind of the ordinary

man is the same as that of the sage because the Original Mind is

perfect and complete in itself. When you have attained this recognition,

hold on to what you have achieved."

During this period, Dhuta10 Ssu-ma came from Hunan to see

Master Po-chang. The Master asked whether it was possible for him

to go to Mount Kuei. The Dhuta answered that Mount Kuei was

extremely steep, but that despite this one thousand five hundred

devotees could gather there. However, the Dhuta said that it would

not be a good preaching place for Master Po-chang. The Master

asked why he said that. The Dhuta pointed out that Master Po-chang

was a gaunt man of ascetic habits, while Kuei was a mountain

of flesh, warm and sensuous, and that if he should go there, he could

expect fewer than a thousand disciples. Po-chang asked him

whether he thought that among his students there might be one

suitable to act as abbot on the mountain. Dhuta Ssu-ma told him he

would like to see all his disciples one by one. Po-chang thereupon

sent for the head monk. The Dhuta ordered him to cough deeply

once and pace several steps, and afterward announced that this

monk was not qualified for the post. Po-chang sent for Ling-yu,

who was the business supervisor of the temple. As soon as he saw

him the Dhuta announced, "Here we have the right man to be the

Master of Mount Kuei!''

The same night Po-chang called Ling-yu to his chamber and

told him, "Mount Kuei will be a splendid place to carry forth the

teaching of our school and to extend enlightenment to the generation

to come."

When the head monk, Hua-lin, heard of this decision he complained

to Po-chang, pointing out that he was the head monk and

deserved the appointment. How could Ling-yu rightfully be appointed

abbot of Mount Kuei? Po-chang said to him:

"If you can make an outstanding response in front of the assembly,

you shall receive the appointment." Po-chang then pointed

to a pitcher and said to him, "Do not call this a pitcher. What, instead,

should you call it?" Hua-lin answered, "It cannot be called

a wooden wedge." Master Po-chang did not accept this, and turned

to Ling-yu, demanding his answer. Ling-yu kicked the pitcher and

knocked it over. Master Po-chang laughed and said, "Our head

monk has lost his bid for Mount Kuei." Ling-yu subsequently was

sent to be abbot of Mount Kuei.

Painting by 狩野元信 Kanō Motonobu (1476–1559)Mount Kuei had formerly been an inaccessible region. The

rocks were steep and high, and no one lived there. Only monkeys

could be found for companions and only chestnuts were available

as food. When people at the foot of the mountain heard that Master

Ling-yu was living there they assembled to build a monastery for

him. Through General Li Ching-jang's recommendation the Royal

Court granted the title Tung-ching to the monastery. Often the

Prime Minister, Pei Hsiu, came to the Master to ask questions

about the meaning of Ch'an, and from this period onward devotees

from all over the country journeyed to Mount Kuei.

One day Master Kuei-shan Ling-yu came into the assembly

and said:

"The mind of one who understands Ch'an is plain and straightforward

without pretense. It has neither front nor back and is without

deceit or delusion. Every hour of the day, what one hears and

sees are ordinary things and ordinary actions. Nothing is distorted.

One does not need to shut one's eyes and ears to be non-attached to

things. In the early days many sages stressed the follies and dangers

of impurity. When delusion, perverted views, and bad thinking

habits are eliminated, the mind is as clear and tranquil as the

autumn stream. It is pure and quiescent, placid and free from

attachment. Therefore he who is like this is called a Ch'annist, a

man of non-attachment to things."

During an assembly period a monk asked whether the man who

has achieved sudden enlightenment still requires self-cultivation.

The Master answered, "If he should be truly enlightened, achieving

his original nature and realizing himself, then the question of self-cultivation

or non-cultivation is beside the point. Through concentration11

a devotee may gain thoughtless thought. Thereby he is

suddenly enlightened and realizes his original nature. However,

there is still a basic delusion12 without beginning and without end,

which cannot be entirely eliminated. Therefore the elimination of

the manifestation of karma, which causes the remaining delusion to

come to the surface, should be taught. This is cultivation. There is

no other way of cultivation. When one hears the Truth one penetrates

immediately to the Ultimate Reality, the realization of which

is profound and wondrous. The mind is illuminated naturally and

perfectly, free from confusion. On the other hand, in the present-

day world there are numerous theories being expounded about

Buddhism. These theories are advocated by those who wish to earn

a seat in the temple and wear an abbot's robe to justify their work.

But reality itself cannot be stained by even a speck of dust, and no

action can distort the truth. When the approach to enlightenment

is like the swift thrust of a sword to the center of things, then both

worldliness and holiness are completely eliminated and Absolute

Reality is revealed. Thus the One and the Many are identified.

This is the Suchness of Buddha."

Yang-shan asked, "What was the meaning of Bodhidharma

coming from the West?"

The Master answered, "A fine large lantern."

"Is it not 'this'? "

"What is 'this'? "

"A fine large lantern," Yang-shan said.

"You do not really know."

One day the Master said to the assembly, "There are many

people who experience the great moment, but few who can perform

the great function." Yang-shan went with this statement to the

abbot of the temple at the foot of the mountain and asked him its

meaning. The abbot said, "Try to repeat your question to me." As

Yang-shan began to do so, the abbot kicked him and knocked him

down. When Yang-shan returned and repeated this to the Master,

Kuei-shan laughed heartily.

The Master was sitting in the Dharma Hall when the treasurer

monk of the temple beat upon the "wooden fish,"13 and the assistant

cook threw away the fire tongs, clapped, and laughed loudly.

The Master said, "In our temple, too, we have people like this. Call

them here so that I can ask them what they are doing." The assistant

cook explained, "I did not eat gruel and I was hungry. So I am

very happy." The Master nodded his head.

Once when all the monks were out picking tea leaves the Master

said to Yang-shan, "All day as we were picking tea leaves I have

heard your voice, but I have not seen you yourself. Show me your

original self." Yang-shan thereupon shook the tea tree.

The Master said, "You have attained only the function, not

the substance." Yang-shan remarked, "I do not know how you

yourself would answer the question." The Master was silent for a

time. Yang-shan commented, "You, Master, have attained only the

substance, not the function." Master Kuei-shan responded, "I

absolve you from twenty blows!"

When the Master came to the assembly, a monk stepped forward

and said to him, "Please, Master, give us the Dharma." "Have

I not taught you thoroughly already?" asked the Master, and the

monk bowed.

The Master told Yang-shan, "You should speak immediately.

Do not enter the realm of illusion."

Yang-shan replied, "My faith in reality is not even established."

The Master said, "Have you had faith and been unable to establish

it, or is it because you never had faith that you could not

establish it?"

Yang-shan said, "What I believe in is Hui-chi. Why should I

have faith in anyone else?"

The Master replied, "If this is the case, you have attained

arhatship."14

Yang-shan answered, "I have not even seen the Buddha."

The Master asked Yang-shan, "In the forty volumes of the

Nirvana Sutra, how many words were spoken by Buddha and how

many by devils?"

Yang-shan answered, "They are all devils' words."

Master Kuei-shan said, "From now on, no one can do anything

to you."

Yang-shan said, "I, Hui-chi, have simply seen the truth in this

one instant. How should I apply it to my daily conduct?" The

Master replied, "It is important that you see things correctly. I do

not talk about your daily conduct."

Once when Yang-shan was washing his clothes, he lifted them

up and asked the Master, "At this very moment, what are you

doing?" The Master answered, "At this moment I am doing

nothing." Yang-shan said, "Master! You have substance, but no

function." The Master was silent for a while, then picked up the

clothes and asked Yang-shan, "At this very moment, what are you

doing?" Yang-shan replied, "At this moment, Master, do you still

see 'this'?" The Master said, "You have function, but no substance."

One day the Master suddenly spoke to Yang-shan, "Last spring

you made an incomplete statement. Can you complete it now?"

Yang-shan answered, "At this very moment? One should not make

a clay image in a moment." The Master said, "A retained prisoner

improves in judgment."

One day the Master called "for the manager of the temple, who

came. The Master said, "I called for the manager of the temple.

Why should you come here?" The manager made no answer.

Thereupon the Master sent an attendant to summon the head

monk. When the head monk appeared the Master said, " I called

for the head monk. Why should you come here?'' The head monk,

too, made no answer.

The Master asked a newly arrived monk what his name was.

The monk said, "Yüeh-lun [Full Moon]." The Master then drew a

circle in the air with his hand. "How do you compare with this?" he

asked. The monk replied, "Master, if you ask me in such a way, a

great many people will not agree with you." Then the Master said,

"As for me, this is my way. What is yours?" The monk said, "Do

you still see Yüeh-lun?" The Master answered, "You can say it

your way, but there are a great many people here who do not agree

with you."

The Master asked Yün-yen, "I have heard that you were with

Master Yüeh-shan for a long time. Am I correct?" Yün-yen said he

was right, and the Master continued, "What is the most distinctive

aspect of Yüeh-shan's character?" Yün-yen answered, "Nirvana

comes later." The Master pressed, "What do you mean, nirvana

comes later?" Yün-yen replied, "Sprinkled water drops cannot reach

it." In turn Yün-yen asked the Master, "What is the most distinctive

feature of Po-chang's character?" The Master answered, "He

is majestic and dignified, radiant and luminous. His is the soundlessness

before sound and the colorlessness after the pigment has faded

away. He is like an iron bull. When a mosquito lands upon him it

can find no place to sting."

The Master was about to pass a pitcher to Yang-shan, who had

put out his hands to receive it. But he suddenly withdrew the

pitcher, saying, "What is this pitcher?" Yang-shan replied, "What

have you discovered from it, Master?" The Master said, "If you

challenge me in this way, why do you study with me?" Yang-shan

explained, "Even though I challenge, it is still my duty to carry

water for you in the pitcher." The Master then passed the pitcher

to him.

During a stroll with Yang-shan, the Master pointed to a cypress

tree and asked, "What is this in front of you?" Yang-shan answered,

"As for this, it is just a cypress tree." The Master then pointed back

to an old farmer and said, "This old man will one day have five

hundred disciples."

The Master said to Yang-shan, "Where have you been?" Yangshan

answered, "At the farm." The Master said, "Are the rice

plants ready for the harvest?" Yang-shan replied, "They are ready."

The Master asked, "Do they appear to you to be green, or yellow, or

neither green nor yellow?" Yang-shan answered, "Master, what is

behind you?" The Master said, "Do you see it?" Then Yang-shan

picked up an ear of grain and said, "Are you not asking about this?"

The Master replied, "This way follows the Goose-King in choosing

milk."15

One winter the Master asked Yang-shan whether it was the

weather that was cold or whether it was man who felt cold. Yangshan

replied, "We are all here!" "Why don't you answer directly?"

asked the Master. Then Yang-shan said, "My answer just now cannot

be considered indirect. How about you?" The Master said, "If

it is direct, it flows with the current."

A monk came to bow in front of the Master, who made a gesture

of getting up. The monk said, "Please, Master, do not get up!" The

Master said, "I have not yet sat down." "I have not yet bowed,"

retorted the monk. The Master replied, "Why should you be ill-mannered?"

The monk made no answer.

Two Ch'an followers came from the assembly of Master Shih-shuang

to the monastery of Master Kuei-shan, where they complained

that no one there understood Ch'an. Later on everyone in

the temple was ordered to bring firewood. Yang-shan encountered

the two visitors as they were resting. He picked up a piece of firewood

and asked, "Can you make a correct statement about this?"

Neither made an answer. Yang-shan said, "Then you had better not

say that no one here understands Ch'an." After going back inside

the monastery, Yang-shan reported to Master Kuei-shan, "I observed

the two Ch'an followers here from Shih-shuang." The Master

asked, "Where did you come upon them?" Yang-shan reported

the encounter, and thereupon the Master said, "Hui-chi is now being

observed by me."

When the Master was in bed Yang-shan came to speak to him,

but the Master turned his face to the wall. Yang-shan said, "How

can you do this?" The Master rose and said, "A moment ago I had

a dream. Won't you try to interpret it for me?" Thereupon Yang-shan

brought in a basin of water for the Master to wash his face. A

little later Hsiang-yen also appeared to speak to the Master. The

Master repeated, "I just had a dream. Yang-shan interpreted it.

Now it is your turn." Hsiang-yen then brought in a cup of tea. The

Master said, "The insight of both of you excels that of Sariputra."16

Once a monk said, "If one cannot be the straw hat on top of

Mount Kuei, how can one reach the village that is free from forced

labor? What is this straw hat of Mount Kuei?" The Master thereupon

stamped his foot.

The Master came to the assembly and said, "After I have passed

away I shall become a water buffalo at the foot of the mountain.

On the left side of the buffalo's chest five characters, Kuei-shan-Monk-

Ling-yu, will be inscribed. At that time you may call me the

monk of Kuei-shan, but at the same time I shall also be the water

buffalo. When you call me water buffalo, I am also the monk of

Kuei-shan. What is my correct name?"

The Master propagated the teachings of Ch'an for more than

forty years. Numerous followers achieved self-realization, and forty-one

disciples penetrated to the final profundity of his teaching. On

the ninth day of the first month of the seventh year [853] of Tachung

of the T'ang Dynasty, the Master washed his face and rinsed

his mouth and then seated himself and, smiling, passed away. This

was sixty-four years after he was ordained. He was eighty-three years

old. He was buried on Mount Kuei where he had taught. His posthumous

name, received from the Royal Court, was Great Perfection,

and his pagoda was called Purity and Quiescence.NOTES

5. The Chinese character Kuei is a phonetic contraction of ku and wei,

according to the most recent and best edited dictionary of Chinese, published

by the Chung-hua Book Company in Shanghai in 1947. Kuei is

indicated as a similar contraction of the original Chinese words by R. H.

Mathews in his well-known Chinese-English Dictionary. However, in both

the K'ang-hsi Dictionary and the Chung-hua Dictionary, which are very

commonly used by the Chinese people in the present day, the pronunciation

is given as chui, which suggests a phonetic contraction of chü and wei.

Ancient dictionaries, such as Kuang-yün by Lu Fa-yen (completed in 601)

and Chi-yün by Tin Tu (completed 1039), record the pronunciation as

chui, which was certainly the common pronunciation before the Sung

Dynasty.

6. Now Changsha, capital of Hunan Province.

7· Foochow, now the capital of Fukien Province.

8. Hangchow, now the capital of Chekiang Province, on the Western

Lake and near the Chien-fang River.

9· In the available Ch'an literature we find these lines as part of a

gatha by the Fifth Patriarch in India. See The Lamp, Chiian 1.

10. A dhuta was a Buddhist monk who traveled, begging his meals, as

part of the purification from material desires.

11. In Ta-chih-tu Lun we read: "The beginner concentrates on yuan

chung (centers of concentration), such as the space between the eyebrows,

the middle of the forehead, or the tip of the nose." The word yuan here

means concentration. In common usage it carries the meaning of causation.

Ta-chih-tu Lun (Mahaprajnaparamitopadesa) is a one-hundred-fascicle

commentary on the Mahaprajnaparamita Sutra, attributed to Nagarjuna,

and translated by Kumarajiva.

12. Vasana, or force of habit, in the Alayavijnana doctrine. In

Mahayana Buddhism, delusion is threefold: (1) active at present, (2)

innate, (3) through force of habit. One may eliminate the first and second,

but the third delusion tends to remain. Those who achieve only Sravakas -

- being merely hearers - cannot rid themselves of it. Those who achieve

Pratyaksa-Buddha, or the middle conveyance, may in part rid themselves

of it. But only Buddha can eliminate all of it.

13. A block of wood with the inside hollowed out. It is beaten with a

stick to announce meals or to accompany the chanting of the sutras, and

is said to keep the monks' minds awake as a fish in water is always awake.

14. An arhat is an enlightened, saintly man, the highest type or saint in

Hinayana, as the Bodhisattva is in Mahayana.

15. The Goose-King symbolizes the Bodhisattva, who drinks the milk

and leaves the water contained in the same vessel. See Chinese Dictionary of

Buddhism, p. 460.

16. One of the ten finest disciples of Buddha, whose wisdom is considered

the greatest of all.

KUEI-SHAN

Translated by Thomas Cleary

In: The five houses of Zen, 1997

Admonitions of Kuei-shan, one of the earliest Zen writings. During the Sung dynasty (960–1278), this work was incorporated into a popular primer of Buddhism and subsequently was made the object of much study and commentary. Orally transmitted sayings of Kuei-shan and his successor Yang-shan appear in many classical anthologies of Zen works, and numerous dialogues between them are used as examples in major collections of teaching stories.

Admonitions

AS LONG AS YOU are subject to a life bound by force of habit, you are not free from the burden of the body. The physical being given you by your parents has come into existence through the interdependence of many conditions; while the basic elements thus sustain you, they are always at odds with one another.

Impermanence, aging, and illness do not give people a set time. One may be alive in the morning, then dead at night, changing worlds in an instant. We are like the spring frost, like the morning dew, suddenly gone. How can a tree growing on a cliff or a vine hanging into a well last forever? Time is passing every moment; how can you be complacent and waste it, seeing that the afterlife is but a breath away?

Inwardly strive to develop the capacity of mindfulness; outwardly spread the virtue of uncontentiousness. Shed the world of dust to seek emancipation.

Over the ages you have followed objects, never once turning back to look within. Time slips away; months and years are wasted.

The Buddha first defined precepts to begin to remove the veils of ignorance. With standards and refinements of conduct pure as ice and snow, the precepts rein and concentrate the minds of beginners in respect to what to stop, what to uphold, what to do, and what not to do. Their details reform every kind of crudity and decadence.

How can you understand the supreme vehicle of complete meaning without having paid heed to moral principles? Beware of spending a lifetime in vain; later regrets are useless.

If you have never taken the principles of the teachings to heart, you have no basis for awakening to the hidden path. As you advance in years and grow old, your vanity will not allow you to associate with worthy companions; you know only arrogance and complacency.

Dawdling in the human world eventually produces dullness and coarseness. Unawares, you become weak and senile; encountering events, you face a wall. When younger people ask you questions, you have nothing to say that will guide them. And even if you have something to say, it has nothing to do with the scriptures. Yet when you are treated without respect, you immediately denounce the impoliteness of the younger generation. Angry thoughts flare up, and your words afflict everyone.

One day you will lie in sickness, flat on your back with myriad pains oppressing you. Thinking and pondering from morning to night, your heart will be full of fear and dread. The road ahead is vague, boundless; you do not know where you will go.

Here you will finally know to repent of your errors, but what is the use of trying to dig a well when you’re already thirsty? You will regret not having prepared earlier, now that it is late and your faults are so many.

When it is time to go, you shake apart, terrified and trembling. The cage broken, the sparrow flies. Consciousness follows what you have done, like a man burdened with debts, dragged away first by the strongest. The threads of mind, frayed and diffused, tend to fall to whatever is most pressing.

The murderous demon of impermanence does not stop moment to moment. Life cannot be extended; time is unreliable. No one in any realm of being can escape this. Subjection to physical existence has gone on in this way for untold ages.

Our regret is that we were all born in an era of imitation. The age of saints is distant, and Buddhism is decadent. Most people are lazy.

If you pass your whole life half asleep, what can you rely on?

If you only want to sit still with folded hands and do not value even a moment of time, if you do not work diligently at your tasks, then you have no basis for accomplishment. How can you pass a whole life in vain?

When you speak, let it concern the scriptures; in discussion, follow your study of the ancients. Be upright and noble of demeanor, with a lofty and serene spirit.

On a long journey, it is essential to go with good companions; purify your eyes and ears again and again. When you stay somewhere, choose your company; listen to what you have not heard time and again. This is the basis of the saying, “It was my parents who bore me; it was my companions who raised me.”

Companionship with the good is like walking through dew and mist; although they do not drench your clothing, in time it becomes imbued with moisture. Familiarity with evil increases false knowledge and views, creating evil day and night. You experience consequences right away, and after death you sink. Once you have lost human life, you will not return ever again, even in ten thousand eons. True words may offend the ear, but do they not impress the heart? If you cleanse the mind and cultivate virtue, conceal your tracks and hide your name, preserve the fundamental and purify the spirit, then the clamor will cease.

If you want to study the Way by intensive meditation and make a sudden leap beyond expedient teachings, let your mind merge with the hidden harbor; investigate its subtleties, determine its most profound depths, and realize its true source.

When you suddenly awaken to the true basis, this is the stairway leading out of materialism. This shatters the twenty-five domains of being in the three realms of existence. Know that everything, inside and outside, is all unreal. Arising from transformations of mind, all things are merely provisional names; don’t set your mind on them. As long as feelings do not stick to things, how can things hinder people? Leaving them to the all-pervasive flow of reality, do not cut them off, yet do not continue them either. When you hear sound and see form, all is normal; whether in the relative world or in the transcendental absolute, appropriate function is not lacking.

If there are people of middling ability who are as yet unable to transcend all at once, let them concentrate upon the teaching, closely investigating the scriptures and scrupulously looking into the inner meaning.

Have you not heard it said, “The vine that clings to the pine climbs to the heights; only based on the most excellent foundation may there be widespread weal”? Carefully cultivate frugality and self-control. Do not vainly be remiss, and do not go too far. Then in all worlds and every life there will be sublime cause and effect.

Cease conceptualization; forget about objects; do not be a partner to the dusts. When the mind is empty, objects are quiescent. Assert mastery; do not follow human sentimentality. The entanglements of the results of actions are impossible to avoid. When the voice is gentle, the echo corresponds; when the figure is upright, the shadow is straight. Cause and effect are perfectly clear; have you no concern?

This illusory body,

this house of dreams:

appearances in emptiness.

There has never been a beginning;

how could an end be determined?

Appearing here, disappearing there,

rising and sinking,

worn and exhausted,

never able to escape the cycle,

when will there ever be rest?

Lusting for the world,

body-mind and the causal nexus

compound the substance of life.

From birth to old age,

nothing is gained;

subjection to delusion comes

from fundamental ignorance.

Take heed that time is passing;

we cannot count on a moment.

If you go through this life in vain,

the coming world will be obstructed.

Going from illusion to illusion

is all due to indulgent senses;

they come and go through mundane routines,

crawling through the triplex world.

Call on enlightened teachers without delay;

approach those of lofty virtue.

Analyze and understand body and mind;

clear away the brambles.

The world is inherently evanescent, empty;

how can conditions oppress you?

Plumb the essence of truth,

with enlightenment as your guide.

Let go of mind and objects both;

do not recall, or recollect.

With the senses free of care,

activity and rest are peaceful, quiet;

with the unified mind unaroused,

myriad things all rest.

KUEI-SHAN AND YANG-SHAN

Translated by Thomas Cleary

In: The five houses of Zen, 1997

Sayings and Dialogues

KUEI-SHAN SAID, “The mind of a Wayfarer is plain and direct, without artificiality. There is no rejection and no attachment, no deceptive wandering mind. At all times seeing and hearing are normal. There are no further details. One does not, furthermore, close the eyes or shut the ears; as long as feelings do not stick to things, that will do.

“Sages since time immemorial have only explained the problems of pollution. If one does not have all that false consciousness, emotional and intellectual opinionatedness, and conceptual habituation, one is clear as autumn water, pure and uncontrived, placid and uninhibited. Such people are called Wayfarers, or free people.”

Kuei-shan was asked, “Is there any further cultivation for people who have suddenly awakened?”

Kuei-shan replied, “If they awaken truly, realizing the fundamental, they know instinctively when it happens. The question of cultivation or not is two-sided. Suppose beginners have conditionally attained a moment of sudden awakening to inherent truth, but there are still longstanding habit energies that cannot as yet be cleared all at once. They must be taught to clear away streams of consciousness manifesting habitual activity. That is cultivation, but there cannot be a particular doctrine to have them practice or devote themselves to.

“Having entered into the principle through hearing, as the principle heard is profound and subtle, the mind is naturally completely clear and does not dwell in the realm of confusion. Even if there are hundreds and thousands of subtleties to criticize or commend the times, you must gain stability, gird your loins, and know how to make a living on your own before you can realize them.

“In essence, the noumenal ground of reality does not admit of a single particle, but the methodology of myriad practices does not abandon anything. If you penetrate directly, then the sense of the ordinary and the sacred disappears, concretely revealing the true constant, where principle and fact are not separate. This is the buddhahood of being-as-is.”

Kuei-shan asked Yun-yen, “What is the seat of enlightenment?”

Yun-yen said, “Freedom from artificiality.”

Yun-yen then asked Kuei-shan the same question. Kuei-shan replied, “The vanity of all things.”

Kuei-shan asked Yang-shan, “Of the forty scrolls of the Nirvana Scripture, how many are Buddha’s talk, and how many are the devil’s talk?”

Yang-shan replied, “They’re all devil talk.”

Kuei-shan said, “Hereafter no one will be able to do anything to you.”

Yang-shan asked, “As a temporary event, where do I focus my action?”

Kuei-shan said, “I just want your perception to be correct; I don’t tell you how to act.”

Kuei-shan passed a water pitcher to Yang-shan. As Yang-shan was about to take it, Kuei-shan withdrew it and said, “What is it?”

Yang-shan responded, “What do you see?”

Kuei-shan said, “If you put it that way, why then seek from me?”

Yang-shan said, “That is so, yet as a matter of humanity and righteousness, it is also my own business to pour some water for you.”

Kuei-shan then handed Yang-shan the pitcher.

Kuei-shan asked Yang-shan, “How do you understand origin, abiding, change, and extinction?”

Yang-shan said, “At the time of the arising of a thought, I do not see that there is origin, abiding, change, or extinction.”

Kuei-shan retorted, “How can you dismiss phenomena?”

Yang-shan rejoined, “What did you just ask about?”

Kuei-shan said, “Origin, abiding, change, and extinction.”

Yang-shan concluded, “Then what do you call dismissing phenomena?”

Kuei-shan asked Yang-shan, “How do you understand the immaculate mind?”

Yang-shan replied, “Mountains, rivers, and plains; sun, moon, and stars.”

Kuei-shan said, “You only get the phenomena.”

Yang-shan rejoined, “What did you just ask about?”

Kuei-shan said, “The immaculate mind.”

Yang-shan asked, “Is it appropriate to call it phenomena?”

Kuei-shan said, “You’re right.”

Yang-shan asked Kuei-shan, “When hundreds and thousands of objects come upon us all at once, then what?”

Kuei-shan replied, “Green is not yellow, long is not short. Everything is in its place. It’s none of my business.”

A seeker asked Kuei-shan, “What is the Way?”

Kuei-shan replied, “No mind is the Way.”

The seeker complained, “I don’t understand.”

Kuei-shan said, “You should get an understanding of what doesn’t understand.”

The seeker asked, “What is that which does not understand?”

Kuei-shan said, “It’s just you, no one else!” Then he went on to say, “Let people of the present time just realize directly that which does not understand. This is your mind; this is your Buddha. If you gain some external knowledge or understanding and consider it the Way of Zen, you are out of touch for the time being. This is called hauling waste in, not hauling waste out; it pollutes your mental field. That is why I say it is not the Way.” Yang-shan asked Kuei-shan, “What is the abode of the real Buddha?”

Kuei-shan said, “Using the subtlety of thinking without thought, think back to the infinity of the flames of awareness. When thinking comes to an end, return to the source, where essence and form are eternal and phenomenon and noumenon are nondual. The real Buddha is being-as-is.”

Yang-shan said in a lecture, “You should each look into yourself rather than memorize what I say. For beginningless eons you have been turning away from light and plunging into darkness, so illusions are deeply rooted and can hardly be extirpated all at once. That is why we use temporarily set-up, expedient techniques to remove your coarse consciousness. This is like using yellow leaves to stop a child’s crying by pretending they are gold; it is not actually true, is it?”

Yang-shan said in a lecture, “If there is a call for it, there is a transaction; no call, no transaction. If I spoke of the source of Zen, I wouldn’t find a single associate, let alone a group of five hundred to seven hundred followers. If I talk of one thing and another, then they struggle forward to take it in. It is like fooling children with an empty fist; there’s nothing really there.

“I am now talking to you clearly about matters pertaining to sagehood, but do not focus your minds on them. Just turn to the ocean of your own essence and work in accord with reality. You do not need spiritual powers, because these are ramifications of sagehood, and for now you need to know your mind and arrive at its source.

“Just get the root, don’t worry about the branches—they’ll naturally be there someday. If you haven’t gotten the root, you cannot acquire the branches even if you study, using your intellect and emotions. Have you not seen how Master Kuei-shan said, ‘When the mentalities of the ordinary mortal and the saint have ended, being reveals true normalcy, where fact and principle are not separate; this is the buddhahood of being-as-is’?”

Encounter Dialogues of Guishan Lingyu

compiled by Satyavayu of Touching Earth Sangha

DOC: Treasury of the Forest of Ancestors

Master Guishan Lingyu came from Fuzhou, in modern Fujian Province on the eastern seaboard of China. At the age of fifteen he left home to become a novice at a nearby temple. In his later teens he traveled to Hangzhou to receive full ordination at Dragon Rising Monastery, and there he stayed on to study scriptures and discipline for a few years. At the age of twenty-two, having become interested in finding a Zen teacher, Lingyu set out for the Hongzhou area in Jiangxi where the famous Master Ma had taught.

When Lingyu visited the Writing Pool Monastery on Stone Gate Mountain, where Master Ma had been buried six years before, he met the master Huaihai (who was the current teacher there) and became one of his first disciples. When Huaihai moved to Baizhang Mountain, Lingyu moved with him, and continued his studies with the master for more than ten years. For much of this time Lingyu served as head of the monastic kitchen.

Once Master Baizhang Huaihai asked Lingyu to see if there were any burning coals left in the fireplace. Lingyu, without checking it, said that the fire was completely out. The master then picked up the tongs, and, searching through the ashes, pulled out a glowing ember and showed it to his disciple, saying, “What's this?” Lingyu then experienced a deep realization of the meaning of practice, and bowed to the master.

The next day, Lingyu accompanied Master Baizhang to do work on the mountain. The master asked, “Did you bring fire?”

Lingyu said, “I brought it.”

The master asked, “Where is it?”

Lingyu then picked up a stick, blew on it twice, and handed it to Baizhang.

The master approved.

After many years with Master Baizhang, Lingyu eventually left for solitary travel, heading west into Hunan. He settled in the Tanzhou region on Gui (or Dagui) Mountain, a sparsely inhabited area described as having steep cliffs, and where there were only monkeys for companions and wild chestnuts for food. Lingyu lived in a hermitage on the mountain for several years before his reputation slowly spread to the nearby villages, and from there to the regional government. Eventually a monastery was built for him called Harmonious Celebration (Tongqing), and he began his formal teaching.

One day Master Guishan Lingyu entered the hall and sat on the teaching seat. A monk came forward and said, “Master, please expound the teaching for the community.”

Guishan said, “ I have already expounded it exhaustively for you.”

The monk bowed.

Once a monk asked Master Guishan, “What is the way?”

Guishan said, “No-mind is the way.”

The monk said, “I don't understand.”

Guishan said, “It's good to understand not-understanding.”

The monk asked, “What is not-understanding?”

Guishan said, “It's just that you are not anyone else.”

One day Master Guishan called for the monastery director. When the director came, Guishan said, “I called the director. What are you doing here?

The director said nothing.

Guishan then asked his attendant to get the head monk. When the head monk came, Guishan said, “I called for the head monk. What are you doing here?

The head monk said nothing.

Once the monk Huiji asked Master Guishan, “When the hundreds and thousands of objects arrive all together, how is it?”

Guisahn siad, “Blue is not yellow; long is not short. All phenomena abide in their own positions, and don't cause me any concern.”

Huiji bowed.

One day Master Guishan addressed the community saying, “There are many who have great capacity, but few who manifest great function.”

Huiji went to visit a hermit who lived near the monastery and told him the master's words. Then he asked, “How do you understand the meaning?”

The hermit said, “Say it again and we'll see.”

When Huiji began to speak, the hermit gave him a kick and knocked him over.

Later Huiji returned to the monastery and told Guishan what happened. The master laughed.

Once when the community was out on the hillside picking tea leaves, the master said to Huiji, “All day today I've heard your voice, but I've not seen you yourself. Show me yourself.”

Huiji shook a tea bush.

The master said, “You attained it's function, but you haven't realized it's essence.”

Huiji asked, “What would the master say?”

Guishan was silent.

Huiji said, “You, master, have attained it's essence, but haven't realized it's function.”

The master said, “I spare you thirty blows of my staff.”

One day Guishan said to Huiji, “I have a lay student who gave me three rolls of silk to buy a temple bell in order to spread happiness to all people.”

Huiji asked, “What did you give him in return?”

Guishan hit the sitting platform three times and said, “This was my offering.”

Huiji asked “How will that benefit him?”

Guishan again hit the platform three times and said, “Why don't you like this?”

Huiji said, “It's not that I dislike it, it's just that that gift belong to everyone.”

Guishan said, “Since you know it belongs to everyone, why did you want me to repay him?”

Huiji said, “I just wondered how you understand that even as it belongs to everyone, you could still make it a gift.

Guishan said, “Don't you see? The great master Bodhidharma, coming from India, also brought a gift. We are always receiving gifts from others.”

Once after sitting Guishan pointed at their straw sandals and said to Huiji, “All hours of the day we receive people's support. Don't betray them.”

Huiji said, “Long ago in Sudatta's garden, the Buddha taught just this.”

Guishan said, “That's not enough, say more.”

Huiji said, “When it's cold, to wear socks for others is not prohibited.”

During the Huichang persecution of Buddhism (841-846) Master Guishan was forced into hiding as a layman and his monastery was partially destroyed. When a more favorable regime returned to power, the influential minister Pei Xiu, recently having become a student of Guishan's spiritual brother Huangpo Xiyun, became a supporter of Master Guishan as well, and helped rebuild his temple. Around this time, Master Guishan wrote an essay about practice and discipline that has come to be known as “Guishan's Admonitions” (Guishan Jingce) and is among the most reliable surviving sources of the teaching of the Tang Dynasty Zen masters (see Part Two – Discourses). Master Guishan's reputation continued to grow, and he attracted numerous officials, as well as monks and nuns, to his monastery seeking advice and teaching.

The government official Commander Lu once came to visit the monastery at Guishan. On a tour of the monk's hall, he asked the master, “Among these monks, who are the meal servers and who are the meditators?”

The master said, “There are no meal servers and no meditators.”

Lu asked, “Then what are they doing here/'

The master said, “Officer, you will have to find that out for yourself.”

One day a twelve year old young woman, the thirteenth daughter of the Zheng family, came to study with Master Guishan, together with an older nun. When they entered the master's room, the elder nun made a full bow and stood up. The master asked, “Where do you live?”

The nun said, “Near the Nantai River.”

The master shouted, then told her to leave. Turning to Zheng, the master asked, “Where does that woman behind you live?”

Zheng relaxed her posture, walked close to the master, and stood there with her hands joined.

The master repeated the question.

Zheng said, “Master, I have already told you.”

The master told her to leave as well.

One day Huiji went to see Master Guishan while the master was lying in bed. When Huiji came in the master sat up and said, “I just had a dream. Will you try to interpret it for me?”

Huiji got up, fetched a basin and a towel, filled the basin with water, and brought it to the master. Guishan washed his face, and arranged himself for sitting.

Just then the monk Zhixian came to see the master. Guishan said, “Huiji has just been demonstrating spiritual power by interpreting my dream. Now you give it a try.”

Zhixian immediately went out, made a cup of tea, and brought it back in to the master.

Guishan said, “The spiritual power and wisdom of you two surpass even Sariputra and Maudgalyayana.”

Once Master Guishan addressed the community saying, “After I have passed away I will become a water buffalo at the foot of this mountain. On the left side of the buffalo will be written the characters 'Gui-mountain-monk-Ling-Yu.' You might say it's the monk of Guishan, but it will still be a water buffalo. You might say it's a water buffalo, but it will also be this monk of Guishan. What will you call me?”

Huiji came forward, made a deep bow, and walked away.

Do not say that I'll depart tomorrow

because even today I still arrive...

I am the frog swimming happily in the clear pond,

and I am also the grass snake who, approaching in silence,

feeds itself on the frog.

I am the child in Uganda, all skin and bones...

and I am the arms merchant, selling deadly weapons to Uganda.

I am the twelve-year-old girl, refugee on a small boat,

who throws herself into the ocean after being raped by a sea pirate,

and I am the pirate, my heart not yet capable of seeing and loving...

Please call me by my true names,

so I can hear all my cries and laughs at once,

so that I can see that my joy and pain are one.

Please call me by my true names,

so I can wake up,

and so the door of my heart can be left open,

the door of compassion.

- Thich Nhat Hahn

If you want to practice Zen and study the Way, then you should immediately go beyond the expedient teachings. You should harmonize your mind with the path (before you), explore the sublime wonders (around you), make a final resolution (to enter) the ultimate understanding, and awaken to the source of truth. (To accomplish this) you should extensively ask for instruction from those who have insight, and should stay close to virtuous friends. The sublime wonder of this teaching is difficult to discover - one must pay very careful attention. If you suddenly awaken to the clear origin then defilements are left behind. The various realms and forms of existence; past, present, and future, are all shattered. You then know that no phenomena, internal or external, are real. Arising from mind’s transmutations, they are all provisional designations. There is no need to anchor the mind anywhere. When feelings simply do not attach to objects, then how can anything become a hindrance? Let the nature of phenomena flow freely without trying to destroy or maintain anything. The sounds you hear and the forms you see all remain ordinary. Wherever you are, you freely respond to circumstances without any mistake.

The mind of a person of the Way is plain and straightforward without pretense. There is no front or back; there is no deceit or delusion. Every hour of the day, you remain aware of ordinary things and ordinary actions. Nothing is distorted. You do not need to shut your eyes or ears to remain unattached to things. The sages of the past warned of the dangers of polluting conceptions - when delusion, biased views, and unwholesome thinking habits are abandoned, the mind is as clear and tranquil as the autumn stream...

When you hear the truth you penetrate immediately to the ultimate reality, the realization of which is profound and wondrous. Mind is illuminated naturally and perfectly, free from confusion. On the other hand, there are innumerable theories about spirituality advocated by those seeking reputation and praise. But reality itself cannot be stained by even a speck of dust; no action can distort the truth. When your approach to awakening is like the swift thrust of a sword to the center, then both worldliness and sacredness are completely cut off, and absolute reality is uncovered. Thus the one and the many are revealed as identical. This is the “suchness” of awakening.

A monk asked master Guishan - Does a person who has experienced sudden awakening still need to cultivate (a practice)?

The master said - When you truly awaken, entering into the fundamental and realizing the nature of self and other, then cultivation and non-cultivation are just dualistic opposing ideas.

Right now, even if the conditions for the initial inspiration arrive, even if within a single thought you awaken to your own true reality, there are still habitual tendencies that have accumulated over endless ages that cannot be dispersed in a single instant. You should certainly be taught to gradually let go of unwholesome tendencies and mental habits. That is cultivation. There is no other cultivation that needs to be taught.

Based on translations by Mario Poceski of Guishan's Admonitions (Guishan Jingce,c.850) and Ch’ang Chun-yuan and Mario Poceski of Guishan’s records in the Jingde Era Transmission of the Lamp (Jingde Chuan Deng Lu, 1004).

Dhyana Master Wei-shan Ling-yu

by Tripitaka Master Hsuan Hua

Translated by Heng Ch'ien

Vajra Bodhi Sea: http://www.drbachinese.org/vbs/1_100/vbs10/10_1.html

Tonight I will speak about the Thirty-seventh Patriarch, Dhyana Master Ling Yu. In the Chinese lineage he is the Tenth Patriarch, and in our own school, the Wei Yang Sect, he is the first.

His life was different from that of ordinary people. When he was a young child, he played "bowing to the Buddha". He led other small children in bowing to the Buddha, and imitated the manner of bhiksus in reciting sutras. Most people referred to him as the "little master". At that time he had not yet left home.

One day, while playing in his front yard, making temples and bowing to the Buddha, an auspicious cloud of miraculous energy manifested above his head in empty space, floating and swirling about. It did not disperse but revolved and swirled above him; from within this cloud could be heard the sound of heavenly music, music played in empty space. Moreover, an appearance like that of the true body of the Buddha could be seen within the cloud--there, and then not there. It was like Ch'en Using Kuo, in Fresno, who one day saw Kuan Yin Bodhisattva. He went to get his camera to take a picture, but when he returned, there was nothing there. He is the son of Lu My Cha; his roots are not bad.

When this auspicious cloud of miraculous energy manifested in empty space, not only did Dhyana Master Ling Yu see it, but many men, women, elders, and children also say it. It neither moved nor scattered. Just then, from one knows not where, came an elder. He looked as if he had come from the mountaintops; he also looked like a person from Yun Nan. He said, "This magical state, this auspicious cloud of miraculous energy, has been made manifest by all the Buddhas of the ten directions, and the multitude of sages. This child is a genuine son of the Buddha. In the future he will surely cause the Buddha's teachings to shine greatly." The child's parents also heard this and considered it extremely strange. After the elder finished speaking, he flicked his fingers four times at the cloud of energy and disappeared. People then thought that the "little master" would some day certainly be a great master.

Dhyana Master Ling Yu was from Fu Chien, Ch'ang Hsi, and his family name was Chiao. After the event described above, he did not involve himself in other matters, but returned to Fu Chou, his home, and there bowed to Vinaya Master Fa Heng as his Master. He began cultivating bitter practices, and was extremely vigorous every day. He was not afraid of hard work, and in fact did twice the amount of work done by the other sramanera and bhiksus. It can even be said that his work could not be done by three other people.

He cultivated bitter practices there for three or four years, after which he cut off his hair and left home. At that time he was twenty years old. When he was twenty-three he went to receive the precepts, after which he went to Hang Chou, where there was a great good knowing advisor with whom he studied the Vinaya. After studying the Vinaya he departed for Kuo Ch'ing Temple on T'ien T'ai Mountain. When he was halfway there he met Great Master Han Shan, who, in his wild way, said to him,

"A thousand mountains, ten thousand waters;

Encountering the pool, stop there.

Obtain the priceless jewel,

Bestow it on posterity."

Dhyana Master Ling Yu did not understand what this meant. As he continued walking he thought to himself, "A thousand mountains, ten thousand waters; encountering the pool, stop there. Obtain the priceless jewel, bestow it on posterity." When he became fatigued he sat in meditation and thought of these four lines: What principle is there in this a thousand mountains, ten thousand waters; encountering the pool, stop there. Obtain the priceless jewel, bestow it on posterity. He walked a while, then stopped, sat down, and reflected upon these words until he arrived at Kuo Ch'ing Temple. Upon his arrival he met another strange character, Shih Te. He told Shih Te about the person he had met, what he had been told, and that he didn't understand what it meant.

Shih Te said, "You don't understand? Gradually you will. Now you should cultivate 'do the work'." So he investigated dhyana and practiced concentration. He had special conditions with Shih Te, and they were together every day.

After a while he heard that Dhyana Master Pai Chang was at Ta Hsiung Mountain in Hung Chou, propagating the true pulse of Ts'ao Hsi (The Sixth Patriarch's Bodhimandala), and so he went to sit beneath his dharma seat. When he arrived he was treated especially well by Dhyana Master Pai Chang who ordered him to be the kitchen manager. The kitchen manager tells the cook what food should be made each day. For example, if there are twenty people, he gives the cook twenty servings of rice; if there are thirty people, he gives him thirty servings. He tells the cook whether there will be people coming or not, whether there will be many people or few. The kitchen manager watches over other jobs, the holders of which must abide by his management: the cook is called the food-head, and the tea maker is called the tea-head. There are times when the tea-head goes on strike, and the kitchen manager assumes the job of tea-head. If the food-head does not get up in the morning, the kitchen manager helps prepare the food. If the fire-head is lazy, the kitchen manager must help light the fires. In tending the fires, the fire-head lights and stirs the fires. One day, when stirring a fire, Dhyana Master Ling Yu opened enlightenment and said, "Originally it's just this way."

Dhyana Master Pai Chang knew that he had opened enlightenment, called for him, and said, "Ta Wei Mountain in Hunan is an extremely fine place. A Bodhimandala should be built there. I am unable to go because my dharma conditions are in Chiang His, so you should go there and propagate the Buddhadharma. Go to Ta Wei Mountain, build a temple, and continue to transmit the Dhyana School without allowing it to be cut off. Save those of posterity."