ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

関山慧玄 / 關山慧玄 Kanzan Egen

(無相大師 Musō Daishi, 1277–1360)

The sole Rinzai lineage to flourish to the present day is the so-called Ōtōkan lineage ( 応灯関 / 應燈 關 ) of Nanpo Jōmyō 南浦紹明 (1235ー1308), usually known as Daiō Kokushi 大應國師; his student Shūhō Myōchō 宗峰妙超 (1282-1337), usually known as Daitō Kokushi 大燈國師; and Shūhō's student Kanzan Egen 關山慧玄 (1277–1360). The term Ōtōkan comes from the “ō” of Daiō, the “tō ” of Daitō, and the “kan” of Kanzan). This lineage has largely shaped Rinzai Zen practice in Japan, and, through the eighteenth-century master Hakuin Ekaku, includes every Rinzai Zen master in Japan today.

KANZAN EGEN

Richard Bryan McDaniel: Zen Masters of Japan. The Second Step East. Rutland, Vermont: Tuttle Publishing, 2013.

Under Shuho’s tutelage, the cloistered emperor, Hanazono, became a sincere devotee of Zen. He converted a portion of one his country estates into a temple where he intended to pursue his practice. He had hoped Shuho would take charge of this new temple, but the master was in poor health. Instead Shuho recommended that the Emperor appoint Kanzan Egen, a monk who was then living in a mountain hermitage. Respecting his teacher’s advice, Hanazono brought Kanzan to Kyoto and put him in charge of the temple, which he called Myoshinji.

In contrast to most of the temples in Kyoto—which vied with one another in their opulence—and despite the fact that it had been specifically designed for an emperor, Myoshinji was very modest. Kanzan himself had few aspirations and lived with great simplicity. The monks at Myoshinji raised their own food in the temple gardens. To some, the temple would have seemed shoddy—the buildings were allowed to age without being repaired and the roof, at times, leaked. But sincere Zen students recognized the purity of the practice under Kanzan’s direction.

Kanzan had begun his Buddhist training in Kamakura, then spent a short time with Shuho’s master, Nampo Jomyo. It was Nampo who gave Kanzan his Buddhist name, Egen. Shortly after they met, Nampo died, and Kanzan returned to his home province, where he lived for a while as a hermit. Twenty years passed before he chanced to learn that Nampo’s heir, Shuho, was teaching at Daitokuji. Although he was now over fifty years old, Kanzan sought to become Shuho’s disciple regardless of the fact that Shuho was younger than he.

Shuho assigned Kanzan the same koan that had brought him to enlightenment, Ummon’s “Kan!” Kanzan worked with the koan for two years before resolving it. When at last he did so, Shuho was so pleased with his attainment that he wrote a poem to commemorate the event:

Where the road is barred and difficult to pass through,

Cold could eternally girdle the green mountain peaks.

Though Ummon’s single “Kan” has concealed its activity

The true eye discerns [it] far beyond the myriad mountains.(Dumoulin, Heinrich. Zen Buddhism: A History – Japan, p. 325.)

The document, known as “Kanzan’s Inka,” remains a Japanese treasure in part because of the quality of Shuho’s calligraphy.

As his teacher had advised him, Shuho likewise advised Kanzan not to begin teaching at once but rather to allow time for his understanding to deepen. So Kanzan retreated to the village of Ibuka in a distant mountain region where for the next eight years he worked as a farm laborer during the day and spent his evenings in meditation seated on a stone ledge that jutted from the edge of a high cliff. He lived in this manner until the Emperor Hanazono summoned him to Kyoto to become the abbot of Myoshinji.

Although he was now in his sixties, Kanzan continued to live as frugally at Myoshinji as he had in the mountains. The temple was small and could only accommodate a few monks. The disciples Kanzan did accept were subjected to an exacting training. Comforts were few; robes were mended rather than replaced; the temple was drafty and the roof leaked.

The koan Kanzan most frequently assigned was: “There is no birth-and-death around Kanzan.” His teaching manner was similar to that of the Chinese Tang masters—he made free use of his staff and shouting. Not many could withstand the rigors of the training, and there were frequent defections. But those who stayed became the basis of one of the strongest lines in Japanese Rinzai. And among those who did remain with Kanzan was the cloistered Emperor Hanazono.

Kanzan lived to be 83 years old. On the day of his death, he told his disciples, “I ask only this of you. Dedicate yourselves to the Great Matter!” Then he donned his travel clothes and went to stand quietly by a pond near the monastery’s front gate. In this manner, he died. His disciples, continuing to respect his austerity and anonymity, did not carry out the usual ceremonies, nor was a tomb constructed for his remains.

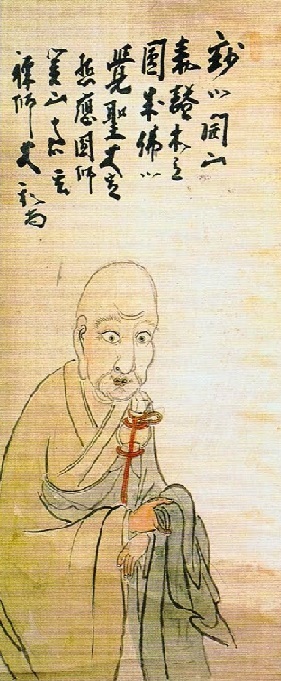

【Muso Daishi Kanzan Egen】 無相大師 関山慧玄

Portrait painted by Hakuin

Kanzan's Dharma Lineage

[...]

菩提達磨 Bodhidharma, Putidamo (Bodaidaruma ?-532/5)

大祖慧可 Dazu Huike (Taiso Eka 487-593)

鑑智僧璨 Jianzhi Sengcan (Kanchi Sōsan ?-606)

大毉道信 Dayi Daoxin (Daii Dōshin 580-651)

大滿弘忍 Daman Hongren (Daiman Kōnin 601-674)

大鑑慧能 Dajian Huineng (Daikan Enō 638-713)

南嶽懷讓 Nanyue Huairang (Nangaku Ejō 677-744)

馬祖道一 Mazu Daoyi (Baso Dōitsu 709-788)

百丈懷海 Baizhang Huaihai (Hyakujō Ekai 750-814)

黃蘗希運 Huangbo Xiyun (Ōbaku Kiun ?-850)

臨濟義玄 Linji Yixuan (Rinzai Gigen ?-866)

興化存獎 Xinghua Cunjiang (Kōke Zonshō 830-888)

南院慧顒 Nanyuan Huiyong (Nan'in Egyō ?-952)

風穴延沼 Fengxue Yanzhao (Fuketsu Enshō 896-973)

首山省念 Shoushan Shengnian (Shuzan Shōnen 926-993)

汾陽善昭 Fenyang Shanzhao (Fun'yo Zenshō 947-1024)

石霜/慈明 楚圓 Shishuang/Ciming Chuyuan (Sekisō/Jimei Soen 986-1039)

楊岐方會 Yangqi Fanghui (Yōgi Hōe 992-1049)

白雲守端 Baiyun Shouduan (Hakuun Shutan 1025-1072)

五祖法演 Wuzu Fayan (Goso Hōen 1024-1104)

圜悟克勤 Yuanwu Keqin (Engo Kokugon 1063-1135)

虎丘紹隆 Huqiu Shaolong (Kukyū Jōryū 1077-1136)

應庵曇華 Yingan Tanhua (Ōan Donge 1103-1163)

密庵咸傑 Mian Xianjie (Mittan Kanketsu 1118-1186)

松源崇岳 Songyuan Chongyue (Shōgen Sūgaku 1132-1202)

運庵普巖 Yunan Puyan (Un'an Fugan 1156–1226)

虛堂智愚 Xutang Zhiyu (Kidō Chigu 1185–1269)

南浦紹明 Nampo Jōmyō (1235-1308) [大應國師 Daiō Kokushi]

宗峰妙超 Shūhō Myōchō (1282-1337) [大燈國師 Daitō Kokushi

關山慧玄 Kanzan Egen (1277-1360) [無相大師 Musō Daishi]

Kanzan Egen 関山慧玄 (Musō Daishi 無相大師)

http://www.myoshinji.or.jp/english/zen/

According to the Shōbōzan Rokuso Den 正法山六祖伝 (Biographies of Myōshin-ji's First Six Patriarchs), Kanzan Egen was born in Shinano (present-day Nagano Prefecture), on January 7, 1277. Following his ordination at Kenchō-ji in Kamakura he met the master Nanpo Jōmyō, who was abbot of Kencho-ji at that time. It was from Nanpo that he received his Buddhist name, Egen 慧玄. After Nanpo's death he studied under Shūhō Myōchō, the founder of Daitoku-ji. Kanzan completed his training under Daitō and was recognized as his successor.

Kanzan subsequently withdrew to the mountains of Ibuka in Minō (present-day Gifu Prefecture) to engage in post-enlightenment training. When the cloistered emperor Hanazono established Myōshin-ji, Kanzan was summoned to Kyoto to serve as the temple's founding abbot. There he devoted himself to training his disciples and became known for his ascetic lifestyle and austere training methods. It is said that on December 12, 1360, just after his final words to his successor Juō Sōhitsu 授翁宗弼 (1296-1380), he passed away dressed in pilgrimage clothes, standing under a tree in front of the Fūsuisen 風水泉 (Wind and Water Spring) in the Myōshin-ji precincts. Several “Kokushi” (National Teacher) titles were bestowed upon him; the best-known is the title Musō Daishi, given to him by Emperor Meiji (1852-1912).

■ Kou, sono moto wo tsutomeyo 請う、其の本を務めよ (I beseech you, examine the source!)

Kanzan left no collection of recorded sayings. Of his few remaining teachings, the following three are the best known:

“Egen ga shari ni shōji nashi” 慧玄が這裏に生死なし (There is no birth-and-death in my place)

This was Kanzan's retort to a monk who said he had come to see the master regarding the great matter of birth-and-death.

“Hakujushi no wa ni zokuki ari” 柏樹子の話に賊機あり (The koan “Zhaozhou's Juniper Tree” functions like a thief)

The koan referred to here is: “A monk asked Zhaozhou Congshen (J. Jōshū Jushin, 778-897), ‘What is the meaning of Bodhidharma's coming from the West?' Zhaozhou answered, ‘The juniper tree in front of the garden.'” The phrase “Functions like a thief” means that this koan robs one of all discursive thoughts.

“Honnu Enjō Butsu” 本有円成仏 (Inherently Perfect Buddha)

One of the central tenets of Kanzan's Zen teaching was the concept of the honnu enjō butsu 本有円成仏, the Inherently Perfect Buddha that is our original nature. Kanzan used this concept as a koan to help his students to awakening: “If we all are inherently perfect buddhas, why then have we become ignorant, deluded sentient beings?”

Among the few anecdotes involving Kanzan that remain, one tells of how the eminent Zen master Musō Soseki 夢窓疎石 (1275-1351) was on his way one day to lecture at the Imperial Palace when his palanquin passed in front of Myōshin-ji. There he saw Kanzan in the garden silently sweeping fallen leaves into a pile. Impressed by Kanzan's quiet humility, Musō commented, “All my disciples may leave me for Kanzan.”

Kanzan's approach to Zen practice is summed up in a statement found in the “Musō Daishi Yuikai 無相大師遺誡 (Final Admonitions of Musō Daishi): “Kō, sono moto o tsutomeyō” (I beseech you, examine the source!). Ordinarily the mind is occupied exclusively with the torrent of thoughts that ceaselessly pours through it, but these thoughts are, finally, just superficial busy-ness and noise. To realize our own true nature—our innate Buddhahood—we must contemplate the still, aware mind out of which thoughts flow. Enlightenment does not come from the outside, but is realized when we turn our light inward and illuminate the mind's source.

Kanzan's exhortation to “examine the source” continues to guide Zen practice at Myōshin-ji today.

![]()

Kanzan (1277–1360): Intelmek

translated into English by D.T.Suzuki (1870–1966)

Fordította: Komár Lajos

Történt pedig a Shogen–időszakban (1259), hogy Ősatyánk, a tiszteletre-

méltó Dai-o átkelt a nagy viharos tengeren, és Sung-ba ment zen-tanul-

mányait folytatni. A kiváló zen mester, Hsu-t’ang (Kido) keze alatt Ching-tz’u

(Jinzu)-ban Dai-o nagy igyekezettel a zen megvalósításának szentelte magát,

mígnem végül Ching-shan (Kinzan)-ban minden titok tudója lett.

Éppen ezért mestere úgy dicsérte, hogy „még egyszer átkelt az ösvényen”,

és megjósolta, hogy „nagyszámú szellemi örököse lesz”. Ősatyánk érdeme

tehát: a Yang-ch’i (Yogi) iskola vonalát meghonosította országunkban.

Tiszteletreméltó tanítóm, Daito beál t Dai-o-hoz, aki a főváros nyugati

részében székelt; szoros, mester-tanítvány kapcsolatban voltak a Kyotó-

beli Manju-ban, és a Kamakura-beli Kencho-ban is. Az így töltött hosszú

esztendők alatt Daito egyszer sem aludt ágyban. (Példája a régi értékek

fontosságára hívja fel figyelmünket.) Amikor mesterré vált, Dai-o átadta

neki szellemi örökségét, és megparancsolta, hogy a következő húsz esz-

tendőt csendes elvonulásban töltse: így képezze magát tovább. Élete a bi-

zonyíték, hogy ama húsz év alatt Daito valóban mestere szellemi örököse

lett. Érdemei közé tartozik, hogy ismét felélesztette a hanyatló Zen-t; va-

lamint intelmei minden követőjének szellemi táplálékot nyújtottak, és a

Zen iránti hűséget eredményezték.

Őszentsége, a néhai Hanazono császár kérésére alapítottam ezt a kolos-

tort, egykori, szeretett mesterem iránti tiszteletből, aki jól megemésztette

az ételt az ő fiókái számára. Ti, követőim, egy nap talán elfeledtek engem,

de ha Dai-o és Daito tanításait elfeleditek, úgy nem vagytok utódaim.

Imádkozom, hogy megragadjátok a jelenségek eredetét. Po-yun (Hakuun)

le volt nyűgözve Pai-chang (Hyakjo) érdemeitől, ahogy Hu-ch’iu (Kokyu) is

magasztalta Po-yun (Hakuun) érdemeit. Ilyen példák állnak előttünk.

Akkor cselekedtek helyesen, ha nem az ágak és levelek között keresgéltek

[hanem amikor a gyökeret ragadjátok meg].