ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

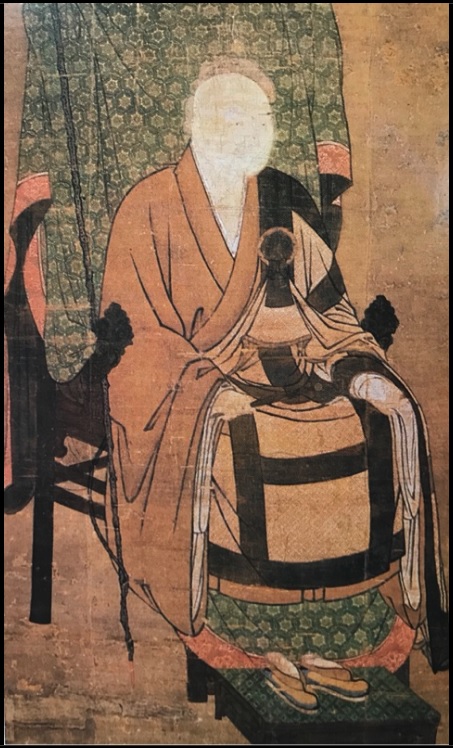

南浦紹明 Nanpo Jōmyō (1235–1308)

posthumous name Enzu Daiō Kokushi 圓通大應國師

usually simply Daiō Kokushi 大應國師

Nampo Jomyo was another who traveled to China to deepen his understanding of Zen.

He was the nephew of Enni Ben’nen and became a monk at the age of 15. Three years later, at 18, he sought out the Chinese master Rankei Doryu [Lanxi Daolong] who had come to Japan to establish Kenchoji as a Rinzai temple in Kamakura. After a time with Rankei, Jomyo went to China to continue studying with Kido Chigu [Xutang Zhiyu], Rankei’s Dharma brother.

In 1265, Jomyo achieved enlightenment and was recognized as an heir by Kido. Kido was so impressed by the young Japanese’s attainment that when the time came for him to return to his home country, Kido wrote this valedictory poem predicting the success he would find in Japan:

To knock on the door and search with care,

To walk broad streets and search the more:

Old [Kido] taught so clear and bright,

And many are the grandchildren on the eastern sea who received [this teaching].(Dumoulin, Heinrich. Zen Buddhism: A History – Japan, p. 39.)

Upon his return to Japan, Jomyo spent some time with his former teacher, Rankei, before moving to the southern island of Kyushu, where he was appointed abbot of Kotokuji and later of Sofukuji, where he taught for thirty years.

In 1304 he was invited to Kyoto by the retired Emperor, Go-Uda in order to become the abbot of Kagenji; however, the continued enmity of the Tendai hierarchy to the incursions of Zen temples into their city prevented him from staying.

His final temple was Kenchoji in Kamakura. At his investiture ceremony, he is said to have proclaimed, “My coming today is coming from no where. One year hence, my departing will be departing to no where.”

Just as he predicted, one year to the day he died. The death poem he left behind reads:

I rebuke the wind and revile the rain,

I do not know the Buddha and patriarchs;

My single activity turns in the twinkling of an eye,

Swifter even than a lightning flash.(Miura and Sasaki, Zen Dust, p. 206.)

Died on the twenty-ninth day of the twelfth month, 1309 at the age of seventy-fourIn 1307, exactly a year before his death, Nampo wrote:

This year, the twenty- ninth of the twelfth

No longer has a place to come to.The twenty- ninth of the twelfth next year

Already has no place to go.These words were taken, after his death, as proof that Nampo knew he would die in a year. And so it was: on the twenty- ninth day of the twelfth month, 1308, Nampo took up his brush, wrote the following poem, and died.

To hell with the wind!

Confound the rain!

I recognize no Buddha.

A blow like the stroke of lightning--

A world turns on its hinge.(Yoel Hoffmann, Japanese Death Poems)

Like Bukko, Jomyo was given a posthumous name, Daio, and the title, National Teacher. The most vigorous line of the Japanese Rinzai School would proceed from the Dharma descendents of Daio Kokushi.

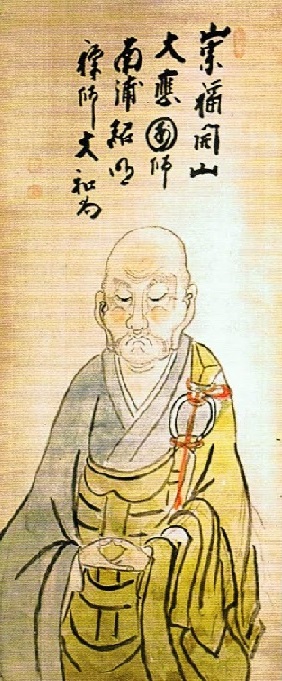

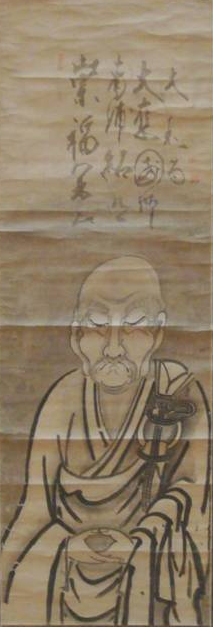

南浦紹明 Nanpo Jōmyō (大應國師 Daiō Kokushi, 1235–1308), painted by Hakuin

DAI-O KOKUSHI "ON ZEN"

Translated by D. T. Suzuki

(Manual of Zen Buddhism, 1935, p. 145)

There is a reality even prior to heaven and earth;

Indeed, it has no form, much less a name;

Eyes fail to see it; It has no voice for ears to detect;

To call it Mind or Buddha violates its nature,

For it then becomes like a visionary flower in the air;

It is not Mind, nor Buddha;

Absolutely quiet, and yet illuminating in a mysterious way,

It allows itself to be perceived only by the clear-eyed.

It is Dharma truly beyond form and sound;

It is Tao having nothing to do with words.

Wishing to entice the blind,

The Buddha has playfully let words escape his golden mouth;

Heaven and earth are ever since filled with entangling briars.

O my good worthy friends gathered here,

If you desire to listen to the thunderous voice of the Dharma,

Exhaust your words, empty your thoughts,

For then you may come to recognize this One Essence.

Says Hui the Brother, "The Buddha's Dharma

Is not to be given up to mere human sentiments."

Nampo Jōmyō's Dharma Lineage

[...]

菩提達磨 Bodhidharma, Putidamo (Bodaidaruma ?-532/5)

大祖慧可 Dazu Huike (Taiso Eka 487-593)

鑑智僧璨 Jianzhi Sengcan (Kanchi Sōsan ?-606)

大毉道信 Dayi Daoxin (Daii Dōshin 580-651)

大滿弘忍 Daman Hongren (Daiman Kōnin 601-674)

大鑑慧能 Dajian Huineng (Daikan Enō 638-713)

南嶽懷讓 Nanyue Huairang (Nangaku Ejō 677-744)

馬祖道一 Mazu Daoyi (Baso Dōitsu 709-788)

百丈懷海 Baizhang Huaihai (Hyakujō Ekai 750-814)

黃蘗希運 Huangbo Xiyun (Ōbaku Kiun ?-850)

臨濟義玄 Linji Yixuan (Rinzai Gigen ?-866)

興化存獎 Xinghua Cunjiang (Kōke Zonshō 830-888)

南院慧顒 Nanyuan Huiyong (Nan'in Egyō ?-952)

風穴延沼 Fengxue Yanzhao (Fuketsu Enshō 896-973)

首山省念 Shoushan Shengnian (Shuzan Shōnen 926-993)

汾陽善昭 Fenyang Shanzhao (Fun'yo Zenshō 947-1024)

石霜/慈明 楚圓 Shishuang/Ciming Chuyuan (Sekisō/Jimei Soen 986-1039)

楊岐方會 Yangqi Fanghui (Yōgi Hōe 992-1049)

白雲守端 Baiyun Shouduan (Hakuun Shutan 1025-1072)

五祖法演 Wuzu Fayan (Goso Hōen 1024-1104)

圜悟克勤 Yuanwu Keqin (Engo Kokugon 1063-1135)

虎丘紹隆 Huqiu Shaolong (Kukyū Jōryū 1077-1136)

應庵曇華 Yingan Tanhua (Ōan Donge 1103-1163)

密庵咸傑 Mian Xianjie (Mittan Kanketsu 1118-1186)

松源崇岳 Songyuan Chongyue (Shōgen Sūgaku 1132-1202)

運庵普巖 Yunan Puyan (Un'an Fugan 1156–1226)

虛堂智愚 Xutang Zhiyu (Kidō Chigu 1185–1269)

南浦紹明 Nampo Jōmyō (1235-1308) [大應國師 Daiō Kokushi]

Sayings of National Teacher Daio at Kofuku Zen Temple

National Teacher Daio's Letters to Meditators

Praises of Kannon by Daio

Translated by Thomas F. Cleary

In: The Original Face: An Anthology of Rinzai Zen, Grove Press, 1978. pp. 59-74.

Sayings of National Teacher Daio at Kofuku Zen Temple

Informal Talk at the Beginning of Winter

Address in the Teaching Hall

Informal Talk on New Year's Eve

Address in the Teaching Hall on the First Night of the New Year

Address in the Teaching Hall on the Anniversary of Buddha's Demise

Address in the Teaching Hall on the First Day of March

Address in the Teaching Hall

Address on the Anniversary of Buddha's Mahaparinirvana• Informal Talk at the Beginning of Winter

Everything is the original law; every day the morn-

ing sun clears the sky, in every mind there is no

separate mind, in every place the pure wind circles the

earth. If you can understand immediately in this way,

then there is no need for Shakyamuni to appear in the

world or for Bodhidharma to come from the west-

in everyone it towers like a mile-high wall, flashing a

great precious light in everyone's presence. One

thought ten thousand years, ten thousand years one

thought, eating when hungry, sleeping when tired, who

worries about the alternation of light and dark, the

change of seasons? Who talks about ice forming from

each drop of water, who says when the weather is cold

the people are cold? Even if you go on this way, this is

still ordinary behavior; how can ultimate transcendence

be revealed? [hitting with his whisk] If winter isn't cold,

wait and see after the twelfth month.An ancient worthy said, "If you want to know the

meaning of enlightened nature, you must watch the

causal relations of time and season; when the time has

arrived, the truth is manifest of itself." Now it is the

beginning of the winter season; tell me, what is the truth

that is revealed? [striking with his whisk] When one sun

rises, myriad species are born.

• Address in the Teaching Hall

A monk asked Joshu, "What is the path?"

Joshu said, "The one beyond the fence."

The monk said, "I'm not asking about that path."

Joshu said, "What path are you asking about?"

The monk said, "The great path."

Joshu said, "The great path goes to the capital."

Daio said in verse: "He points it out so clearly, face

to face without deception; the great path is straight as a

bowstring, but travelers make trouble for themselves."

• Informal Talk on New Year's Eve

Hanging high the jewel mirror, ranging myriad

images before the eyes, holding the sharp sword

sideways, cutting off all impulses beyond conception,

covering heaven and earth, passing through form and

sound, shutting down and opening up at will, killing

and giving life according to the occasion, in full

command of holding fast or letting go. This is whereby

patch-robed monks explain what cannot be practiced

and practice what cannot be explained, changing in

thousands of ways freely-even disrupting the order of

time and wiping out the elemental spirits is not beyond

their capability. But even so, tonight I forgo the first

move; when the twelfth month is over, as of old, it is up

to spring to return. Why? I want you people to take care

at all times.

• Address in the Teaching Hall on the

First Night of the New Year[describing a circle in the air with his whisk]

Lighting this lamp, all lamps immediately shine; the

dense web of myriad shapes and forms has nowhere to

hide. If under an overturned bowl, how can you blame

me? [a long silence] But tell me: what lamp is it?

• Address in the Teaching Hall on the

Anniversary of Buddha's DemiseThe single heart not dwelling in extinction point-

lessly sells off the golden body; up till now the ugliness

has been impossible to conceal-what a mess, every

year, the peach-blossom spring.

• Address in the Teaching Hall on the

First Day of MarchSpeaking of Zen, expounding the way, talking about

marvel and mystery, is all gouging wounds in healthy

flesh. Ultimately, what? "I always remember southern

China in the spring, the fragrance of the hundred

flowers as the partridges cry."

• Address in the Teaching Hall

Great Master Ummon said to his group, "Monks,

don't think falsely; mountains are mountains, rivers are

rivers."Then a monk came forward and said, "How is it

when I see that mountains are mountains and rivers are

rivers?"Ummon said, "Why is the Buddha shrine passing

through here?"The monk said, "Then I am not thinking falsely."

Ummon said, "Give me back the words."

[citing this, Daio said] So then what is easy to open

is the beginning and ending mouth; what is difficult to

maintain is the heart of the dead of winter. When that

monk heard Ummon say, "Why is the Buddha shrine

passing through here?" if he had just said, "It should be

so," he would not only have shown his own light, he

would have also seen through Ummon's standpoint.

• Address on the Anniversary of

Buddha's MahaparinirvanaThe Buddha body fills the cosmos, manifest to all

sentient beings everywhere. [raising his whisk] This a

whisk; where is the Buddha body? People, if you can set

a single eye here, you will see the solemn assembly on

Spiritual Mountain has not yet dispersed, but if you

hesitate and doubt, the ancient Buddha is long gone.

National Teacher Daio's Letters to Meditators

To Zen Man Gentei

To Kyoen, Latter Abbot of Manju Monastery

To Nun Gentai

To Bath Steward Genan

To Zen Man Kusho

To Zen Man Genchu• To Zen Man Gentei

The World Honored One raised a flower, Kasyapa

smiled-gold is not exchanged for gold, water does not

wash water; since then it has come down from genera-

tion to generation, taking in an echo from empty space,

one person communicating it to one other . Hence we

see Zen teachers doing things like going east to west,

west to east, Hoshan beating a drum, Bimo raising his

forked stick, Xuefeng rolling balls, [udi raising his

finger, three pounds of hemp, the cypress tree in the

garden, and myriad other illustrations, hundreds of

thousands of actions using it, all coming forth in the

same pattern, strung through on one thread. If one is a

genuine patch-robed monk, who would care whose

ladle handle was long or short? If you don't dump the

gourd, the vinegar becomes sharper and sharper. Just go

by your own sight; live on your own. Eminent Gentei

quickly set your eyes to see before the W orld Honored

One raised the flower; keep watching whatever you do

until this work becomes pure and refined to the point

where in one moment you merge and see the original

face, the scenery of the original ground. At that time

tawny old Buddha and the golden ascetic Kasyapa wili

both stand downwind of you. That is why it is said that

a powerful man is the ancestor of mind before heaven

and earth. Think of this, eminent Tei, think of this.

• To Kyoen, Latter Abbot of Manju Monastery

When Rinzai left Obaku long ago, Obaku said,

"Where are you going?" Rinzai said, "If not south of the

river, then north of the river." Obaku then hit him.

Rinzai grabbed the staff and slapped him. Obaku

laughed loudly, called his attendant, and said, "Bring

me the meditation brace and whisk of my late master

Hyakujo."Rinzai called to the attendant, "Bring me fire." After

all, a good son doesn't use his father's money.Obaku said, "Just take them away; later you will cut

off the tongue of everyone on earth." This old fellow

cared so for his child that he did not mind being

unseemly.Eminent Kyoen has been with us on this mountain

for four years, and his determination and mindfulness

in investigation of the way are solid and firm; in his

daily actions he is never off balance. Now he is going to

another mountain and has come to take leave of us.

Though the eminent has the ability to ask for fire, I have

no meditation brace or whisk to hand over. But tell me:

is this the same as the ancients or different? If you

should encounter someone at a crossroads in a village of

three families, don't misquote this.

• To Nun Gentai

Sister Gentai, from the capital. Her determination in

seeking the way is keen, and she often comes to inquire

further into the basis and conditions of this great

matter. One day I said to her, "At the top of the

hundred-foot pole, go forward."She said, "At the top of the hundred-foot pole, there

is no place to go."I said, "Where there is no place to step, go a

hundred thousand steps farther-only then will you be

able to walk alone in the red skies, pervading the

universe as your whole body." She agreed and smiled;

that's all. Although she has not yet gotten the gist of it,

she is not the same as ordinary folk who get stuck on

even ground.Now you want to return to your old capital and have

come with incense in your sleeve to ask for a saying . I

once made a verse of praise on the master of Ikusan in

Daryo,* so I will write that:Atop the pole, walk on by the ordinary route -

It is most painful, when taking a tumble in a valley

Earth, mountains, and rivers cannot hold you up

And space suppresses laughter, filling a donkey's cheeksI ask you, Zen nun, to bring this up and look at it time

and again; how to go forward from atop the pole?

Suddenly, when the time comes, you can go forward a

step, and space will surely swallow a laugh. Remember,

remember.*The master of Ikusan worked on a koan - "How to proceed

forward from atop the hundred-foot pole? Uh!" - for three years,

when one day, as he was crossing a valley stream on a donkey, the

bridge plank broke and he fell, whereupon he was greatly en-

lightened. Atop the pole means at the peak of meditation, or

personal detachment and liberation, or it can be used to refer to the

farthest point of any aspect of work on the way. It usually refers,

however, to the esoteric death, after which the "step forward,"

return to life, at one with the world, is the beginning of the next,

usually more difficult, phase of Zen study.

• To Bath Steward Genan

The peak experience, the final act; as soon as you try

to pursue it in thought, there are white clouds for a

thousand miles . But even if you go back upon seeing

the monastery flagpole at a distance, or head off freely

upon seeing a beckoning hand, this is still only half the

issue; it is not yet the strategic action of the whole

capability.Bath steward An has traveled and studied various

places and spent a long time in monasteries. Don't stick

to the ruts in the road of the ancients-you must travel a

living road on your own . East, west, foot up, foot down,

using it directly-only then will you know the peak

experience illumines the heavens and covers the earth,

illumines the past and flashes through the present. This

is your own place to settle and live. When I say this, I

am only using water to offer flowers, never adding

anything extra. This of this, eminent, think of this.

• To Zen Man Kusho

The cause and conditions of the one great concern of

the enlightened ones is not apart from your daily affairs;

there is no difference between here and there-it

pervades past and present, shining through the heavens

mirroring the earth. That is why it is said that every-

thing in the last myriad eons is right in the present. We

value the great spirit of a hero only in those concerned-

before any signs become distinct, before any illustration

is evident, concentrate fiercely, looking, looking, com-

ing or going, till your effort is completely ripe and in the

moment of a thought you attain union, the mind of

birth and death is destroyed and suddenly you clearly

see your original appearance, the scene of your native

land; each particular distinctly clear, you then see and

hear just as the buddhas did, know and act as the

enlightened ancestors did. Only then do you really

manage to avoid defeat in your original purpose of

leaving home and society and traveling for knowledge

and enlightenment. Zen man Kusho, work on this.

• To Zen Man Genchu

Since ancient times, the enlightened ancestors ap-

pearing in the world relied just on their own fundamen-

tal experience to reveal something of what is before us;

so we see them knocking chairs and raising whisks,

hitting the ground and brandishing sticks, beating a

drum or rolling balls, hauling dirt and stones-"A ten-

ton catapult is not shot at a rat."Even though this is so, eminent Genchu, you have

traveled all over and spent a long time in monasteries;

don't worry about such old calendar days as these I

mentioned-just go by the living road you see on your

own; going east, going west, like a hawk sailing through

the skies. In the blink of an eye you cross over to the

other side.If you are not yet capable of this, then look directly

at before the enlightened ones were present, before the

world was differentiated; twenty-four hours a day,

walking, standing, sitting, reclining, carefully, continu-

ously, closely, minutely, look, look, all the time. When

this directed effort becomes fully developed and pure,

suddenly in an instant you are united, the routine mind

is shattered and you see the fundamental countenance,

the scenery of the basic ground. Everything will be

distinctly clear; it is as if ten suns were shining. When

you get to this state, you should be even more careful

and thorough going. Why? At the last word you finally

reach the impenetrable barrier.Eminent Genchu has been with our group for a

summer and suddenly wants to go to another mountain.

Just before leaving, he asked for some words, so I wrote

this, letting the pen write what it would, to fulfill his

request.

Praises of Kannon by Daio

the sphere of perfect communion is clear everywhere

the pitcher water is alive, the willow eyes are green

there are also cold crags and early green bamboo

why are people these days in such a great hurry?the cliffs are high and deep, the waters rush and tumble

the realm of perfect communion is new in each place

face to face, the people who meet her don't recognize her

when will they ever be free from the harbor of illusion?lotus blossoms always in her hands, she stands alone magnificent

a boy comes to call

wordless, eyes resemble eyebrows

know that outside of joining the palms and bowing the head

how could this thing be explained to him?the sound of the rushing spring is cool and subtle

the colors of the mountain crags are deep but distinct

in every field the realm of perfect communion

how can Sudhana know?the dense crags jut forth precipitous

the waterfalls spew an azure loom

in each land the sphere of perfect communion

those who go right in are rarethe clouds are thin, the river endless

the universal door appears without deception

questioning the boy, he doesn't yet know it exists

he went uselessly searching in the cold of the mist and waves

in a hundred cities

南浦紹明 Nanpo Jōmyō (大應國師 Daiō Kokushi, 1235–1308), painted by Hakuin

![]()

Daio Kokushi zenről szóló verse

Fordította: Varga Imre

(Zen Benedek, Budapest, Kortárs Kiadó, 62-63. oldal)

A végső valóság égnél, földnél elébb való

Formája, sőt neve sincsen.

Nem látja szem, nem hallja fül.

Szellemnek vagy Buddhának nevezni sem az ő természete.

A név, akár ha művirág lenne csupán.

Nem szellem, nem Buddha ő,

tökéletes nyugalma sugárzik.

Csak a tiszta szem láthatja meg.

Ő a hangon és formán túli törvény.

Ő az út, s nem illetheti szó.

Buddha játékos szavait hallani nem-látók

gyűltek körébe. Azóta eget-földet ellep

a burjánzó tüskés bozót.

Nagytiszteletű és kedves barátaim, akik itt egybegyűltetek,

ha a dharma mennydörgő hangját

szeretnétek hallani,

a szavakat engedjétek el,

a tudat váljék üressé,

s ekkor megtapasztalhatjátok az egyetlen valót.

[…]

Dai-o (1235–1308): Intelmek

translated into English by D.T.Suzuki (1870–1966)

Fordította: Komár Lajos

Ki a Tan kapuján belép, első dolga legyen kifejleszteni alázatos és tisztelet-

tudó módon a szerzetességbe vetett szilárd elhatározást, amely a kivezető

ösvény a hatalmaskodás és megalázkodás tévútjairól.

Legyen alázatos, ahogy a három világ Tankirályának (Dharmaraja) fia

viselkedik; ez nem az a hercegi alázat, ahogy nemes urak előtt megaláz-

kodunk. Legyen tisztelettudó, ahogy minden érző lény atyjával teszik; ez

nem csupán a családfőt megillető tiszteletadás. Amikor a szerzetes kellő-

en alázatos és tisztelettudó, a Tan barlangjában él, a gyakorlás mámorában

tölti napjait, és a Három Kincs védőistenségeinek oltalmát élvezi, kíván-

hat-e ennél többet?

A borotvált fej és a színezett köntös a tökélyharcos jelképei; a templomi

építkezések pedig, minden más jelképpel egyetemben, a nemes buddhista

szándék kifejezései. Ezeknek semmi közük a cicomához és pompához.

Az a szerzetes, aki ily módon tisztelettudóan és tiszteletreméltóan vi-

selkedik, követői mindenfajta felajánlásaira érdemes; minden figyelmét a

Tanra szentelheti, anélkül hogy világi feladatokra fecsérelné idejét – elmé-

jét valóban a Buddhákhoz és az Atyákhoz fordítva. Amennyiben a szerze-

tes ilyen életforma mellett sem képes átkelni a születés-halál hömpölygő

folyamán, akkor ugyan mikor hálálja meg az ősök szerető gondoskodását?

Bármikor elszalaszthatjuk a szerencsénket; ezért a szerzetes mindig álljon

készen, ne henyéljen!

A Buddhák és az Ősatyák által jelzett ösvény a tanátadás ősi, rejtélyes

útja, mely felvezet a Hegyre; ezen az úton haladni egyben a tiszteletünk és

hálánk jele is. Amennyiben a szerzetes nem képes fegyelmezni magát az

úton, úgy elkülönül a tisztelettudó és tiszteletreméltó társaitól; egy szeren-

csétlen nyomorult lesz csupán. Öregségemre csupán ennyi bánkódnivaló

jutott; és Ó, szerzetesek, ez ügyben fáradságot nem kímélve segítettem

mindannyitokat, a nap bármely szakában. Így, távozásom közeledtével is,

együtt érzek veletek, és imádkozom, hogy a tisztelettudó és tiszteletreméltó

szerzetesi erényekben sosem szűkölködjetek, és azokhoz mindig méltó

módon létezzetek. Imádkozzatok, és ezeket jól véssétek eszetekbe!

Dai-o: A Zen

Valóság, nem földi, sem mennyei,

nincs alakja, sem neve,

szem nem látja, fül nem hallja,

a „Tudat” vagy „Buddha” nevek sértik természetét,

látomás, mint virág az űrben,

nem Tudat, sem Buddha,

csendes, fénylő ragyogás,

kinek nem fedi por szemét, látja csak.

Tan, nem látvány, sem hang,

Ösvény, szavak nélkül.

Hogy a vakok is lássák,

a Magasztos kinyilatkozott, s mára

mennyről s pokolról zagyva beszéd lett csupán.

Barátok, kik itt összegyűltetek

a Tan mennydörgő hangjára vágyva,

mikor nincs szó, sem gondolat,

felismeritek az Egy lényegét.

A Magasztos Tana ez, mely

minden lény üdvére van.