ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

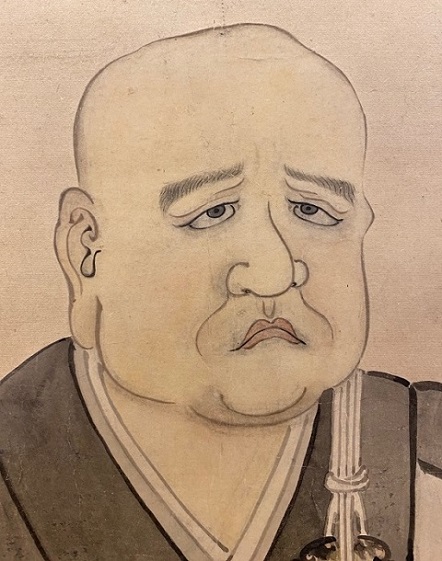

宗峰妙超 Shūhō Myōchō

(大燈国師 Daitō Kokushi, 1282–1337)

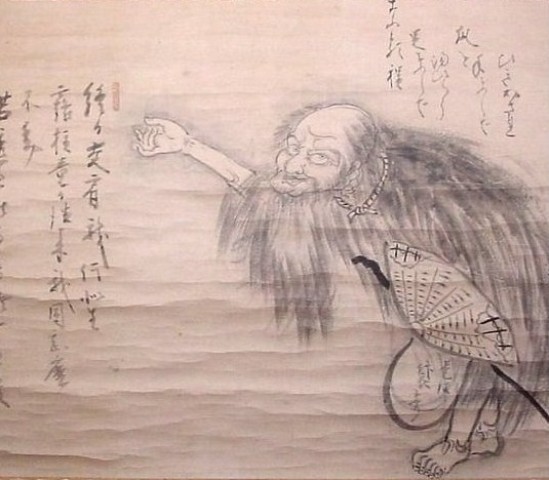

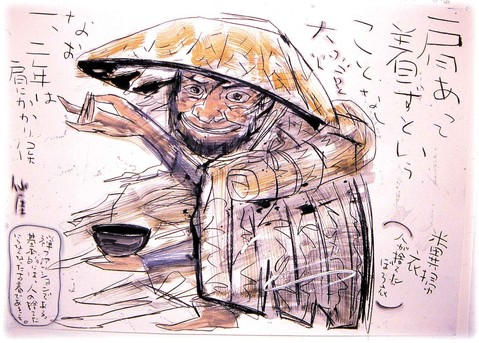

Daitō Kokushi as a Beggar [1] [2] [3] [4] by Hakuin

Daitō Kokushi as a Beggar by

高根英博 Takane Hidehiro (1952-)

![]()

The sole Rinzai lineage to flourish to the present day is the so-called Ōtōkan lineage ( 応灯関 / 應燈 關 ) of Nanpo Jōmyō 南浦紹明 (1235ー1308), usually known as Daiō Kokushi 大應國師; his student Shūhō Myōchō 宗峰妙超 (1282-1337), usually known as Daitō Kokushi 大燈國師; and Shūhō's student Kanzan Egen 關山慧玄 (1277–1360). The term Ōtōkan comes from the “ō” of Daiō, the “tō ” of Daitō, and the “kan” of Kanzan). This lineage has largely shaped Rinzai Zen practice in Japan, and, through the eighteenth-century master Hakuin Ekaku, includes every Rinzai Zen master in Japan today.

SHUHO MYOCHO [DAITO KOKUSHI]

Richard Bryan McDaniel: Zen Masters of Japan. The Second Step East. Rutland, Vermont: Tuttle Publishing, 2013.

The imperial household had little actual practical power during the Kamakura Shogunate; the Emperor’s duties amounted to slightly more than signing official documents and participating in ceremonial religious rituals; however, the Court had more than enough to keep itself occupied with internal wrangling.

A complex system of reigning and “retired” emperors had evolved, initiated by the Emperor Go-Sanjo. Emperors often came to the throne while still children and were then pressured to retire in early youth in order to ensure that they did not acquire any genuine personal power. In the Insei System developed by Go-Sanjo, the “retired” Emperor—who technically entered a monastery and became “cloistered”—was still able to exert influence over his younger successor. The system did not profit Go-Sanjo, as it happened; he died a month after becoming “cloistered.”

His son, the Emperor Shirakawa, reigned from 1073 (when he was 20 years old) until 1087, at which time he raised his own son to the throne in order to protect the boy from the machinations of Shirakawa’s younger brother who had ambitions of becoming emperor himself. Although Shirakawa became “cloistered,” he was able to wield a great deal of influence over his son. This pattern was to be followed by subsequent emperors who, after reigning for a period of time, would retire to a monastery but retain the capacity to exert control over their successors. Some retired and cloistered emperors even maintained their own armies. The situation was further complicated by the fact that, depending upon the longevity of the retired emperors, there could be more than one “Cloistered” Emperor trying to exert influence at any given time. Shirakawa, for example, lived to be 76 years old.

When the Emperor Go-Saga died in 1272, the royal family divided into two branches, both of which claimed the right to determine who sat on the chrysanthemum throne. These branches were made up of the descendants and supporters of Go-Saga’s sons, Fukakusa and Kameyama. Fukakusa’s branch of the family came to be known as the Jimyoin-to; Kameyama’s as Daikakuji-to. Fukakusa became emperor, but the Daikakuji-to did not relinquish their claims. In order to resolve the on-going squabble, the Shogunate determined that the two branches would alternately provide a successor to the throne every ten years.

In 1308, the twelve-year-old son of Emperor Fushimi of the Jimyoin-to line became the Emperor Hanazono. He reigned for ten years, abdicating the throne at age 22 in favor of his second cousin, Go-Daigo of the Daikakuji-to lineage. After abdicating, Hanazono became a “cloistered emperor” not only in name but also in fact, dedicating himself to a serious study of Buddhism.

The retired Emperor heard a rumor that a Zen master of exceptional ability had come to the city of Kyoto where, instead of establishing himself at one of the city’s temples, he had chosen to live among the derelicts and beggars residing under the Gojo Bridge. The emperor was intrigued by the tale and asked his informant if there were any way that he could identify which of the beggars was the modest Zen Master. All the informant could tell him was that it was rumored the master was particularly fond of honeydew melons.

Hanazono disguised himself as a fruit peddler and pushed a cart laden with melons to the region by the bridge. As the residents gathered around him, he held up a ripe melon and announced, “I will give this melon freely to anyone who can come up to me and claim it without using his feet.”

One of the beggars immediately challenged him, “Then give it to me without using your hands.”

It was as much the gleam in the eye of the beggar as his reply that told Hanazono that he had found the Zen teacher he was seeking. His name was Shuho Myocho. He would later come to be known as Daito [Great Light] Kokushi [National Teacher].

When Shuho was only ten years old, he became weary of the things of childhood and turned to serious studies. He sought a teacher to introduce him to the doctrines of Buddhism and began to practice meditation. He was only slightly older when he went on a pilgrimage to various monasteries and hermitages in Japan. While residing at a monastery in Kamakura, he had an initial awakening which deepened his resolve to come to full enlightenment.

Around 1304, Shuho came to Kyoto where he was accepted as a student of Nampo Jomyo (whose posthumous name—Daio Kokushi—is easily confused with Shuho’s). Nampo assigned the young man the koan known as Ummon’s “Kan!” The full koan consists of the replies of three students to a question posed by Suigan Reisan [Cuiyan Lingcan]. Suigen had been head monk under Seppo Gison [Xuefeng Yicun] at the time Ummon [Yunmen Wenyan] was also a student of Seppo [Cf. Zen Master’s of China, Chapter Nineteen]. Suigen had given the encouragement talks during a meditation retreat, and, once the sesshin was over, he asked three of the participants, “Long have I lectured you these past days. Now, tell me, has Suigan any eyebrows?”

The first monk replied, “A thief surely knows in his heart that he is a thief.”

The second monk said, “Rather than falling out from all that talking, they have grown longer!”

And Ummon simply shouted, “Kan!” [literally, “barrier” or “gate” as at a border crossing].

After concentrating on “Kan!” for ten days, Shuho came to a deep awakening. He later wrote that in penetrating the koan he came to a state of non-duality in which all opposites were reconciled; the whole of the Dharma, he declared, was clear to him. Bathed in sweat, he rushed to express his understanding to his teacher. But before he had a chance to speak, Nampo was able to tell from his deportment that he had attained enlightenment.

“I had a dream last night,” Nampo told him, “in which it seemed that the great Ummon himself had come into my room. And here today you are—a second Ummon!”

Shuho, embarrassed by the compliment, covered his ears and fled from his teacher’s chamber. But the next day he returned and presented Nampo with two poems he had written to commemorate his achievement:

Having once penetrated the cloud barrier [kan],

The living road opens out north, east, south, and west.

In the evening resting, in the morning roaming, neither host nor guest.

At every step the pure wind rises.Having penetrated the cloud barrier [kan], there is no old road,

The azure heaven and the bright sun, these are my native place.

The wheel of free activity constantly changing is difficult to reach.

Even the golden-hued monk [Kasyapa] bows respectfully and returns.(Dumoulin, Heinrich. Zen Buddhism: A History – Japan, p. 186.)

Kasyapa, or Mahakasyapa, was the monk to whom the Buddha, in the legendary Flower Sermon, had first passed on the enlightenment tradition. The story is told in the Prologue of Zen Masters of China.

Nampo recognized Shuho as his heir and expressed confidence that now his teaching would persist. He then advised the younger man to refrain from taking students for another twenty years; instead, he should use the time to continue his meditation and deepen his understanding. When Nampo died, Shuho left the monastery and spent the next twenty years residing among the indigent, beggars, and street people in Kyoto until the Emperor Hanazono found him under the bridge at Gojo.

Shuho, who in addition to being a master of meditation was also a talented poet and calligrapher, described this time of homelessness in verse:

Sitting in meditation

one sees people

crossing and re-crossing the bridge

just as they are.

Hanazono eventually became Shuho’s disciple, but first it was necessary for the two to acquire an understanding of their relative status. On one occasion, early in their acquaintance, Shuho was seated with Hanazono. Both were on the same level. Protocol would have had it that under normal circumstances the commoner would be below the Emperor, who would be seated on a raised platform. Hanazono, perhaps to draw Shoho’s attention to the honor being paid him, remarked casually, “Is it not wondrous that a Zen master should sit at the same level as an Emperor?”

“Is it not wondrous that an Emperor should sit at the same level as a Zen master,” Shuho shot back.

Hanazono donated grounds for a new temple to be called Daitokuji, and Shuho was installed as its first abbot. Both Hanazono and the reigning emperor, Go-Daigo, attended the dedication ceremony officially opening the temple. Shuho would remain at Daitokuji for the rest of his life except for a period of one hundred days during which he acted as abbot of Nampo Jomyo’s temple, Sofukuji.

Shuho taught his students to seek their “original countenance,” what the Sixth Patriarch in China had called “one’s face before one’s parents were born.”

—the original countenance that you had before you were born of your mother and father! Before you were born of your mother and father means before your mother and father were born, before heaven was separated from earth, before I took on human form. Your original countenance must be seen.

As with the classical Chinese teachers of the Tang dynasty, Shuho maintained that awakening was central to Buddhist practice. In a document called Daito’s Testament, he reminded his students, “You have come here not for food or clothing but for religion. As long as you have a mouth, you will have food; as long as you have a body, you will have clothes. Don’t concern yourself with these. Be mindful throughout your waking hours; time flies like an arrow, don’t waste it with concern over worldly matters.” He went on to tell his disciples that even if they were to become the abbots of wealthy monasteries and received the respect of the laity and nobility, even if they were rigorous in their practice of meditation and ritual activities, but they lacked awakening, they were no more than members of the “tribe of evil spirits.” Conversely, if they were poverty stricken, lived in a ramshackle hermitage, and ate only what wild food they gathered in the forests and yet they were awakened, then they would be “one who meets me face to face and repays my kindness.”

He established a daily schedule of periods of zazen, sutra recitation, and other activities that rivaled the rigors of Chinese monasteries. However, while the monks in China and India limited themselves to only two meals a day, Shuho accommodated the conditions in Japan and permitted a small evening meal that was referred to as “medicine.”

In his instructions to his students, Shuho stressed the importance of proper posture and the traditional cross-legged sitting associated with meditation. However, in his fifties he sustained an injury to his leg that prevented him from assuming these postures. When he was in his final illness, he forced his legs into the lotus posture, breaking his bone [a similar story is told of Ummon]. The injured leg bled and the pain was severe, but he sat calmly and took up a brush to compose his death poem

I have cut off buddhas and patriarchs;

The Blown Hair [Sword] is always burnished;

When the wheel of free activity turns,

The empty void gnashes its teeth.(Miura and Sasaki, Zen Dust, p. 234.)

After completing the poem, he passed away at the age of fifty-six.

DOC: Eloquent Zen: Daitō and Early Japanese Zen

by Kenneth Kraft

University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1992.

PDF with Michel Mohr book review:

Mohr, Michel (1993). "Examining the Sources of Japanese Rinzai Zen: A Review of Kenneth Kraft, Eloquent Zen: Daitō and Early Japanese Zen ." Japanese Journal of Religious Studies.

Shūhō Myōchō's Dharma Lineage

[...]

菩提達磨 Bodhidharma, Putidamo (Bodaidaruma ?-532/5)

大祖慧可 Dazu Huike (Taiso Eka 487-593)

鑑智僧璨 Jianzhi Sengcan (Kanchi Sōsan ?-606)

大毉道信 Dayi Daoxin (Daii Dōshin 580-651)

大滿弘忍 Daman Hongren (Daiman Kōnin 601-674)

大鑑慧能 Dajian Huineng (Daikan Enō 638-713)

南嶽懷讓 Nanyue Huairang (Nangaku Ejō 677-744)

馬祖道一 Mazu Daoyi (Baso Dōitsu 709-788)

百丈懷海 Baizhang Huaihai (Hyakujō Ekai 750-814)

黃蘗希運 Huangbo Xiyun (Ōbaku Kiun ?-850)

臨濟義玄 Linji Yixuan (Rinzai Gigen ?-866)

興化存獎 Xinghua Cunjiang (Kōke Zonshō 830-888)

南院慧顒 Nanyuan Huiyong (Nan'in Egyō ?-952)

風穴延沼 Fengxue Yanzhao (Fuketsu Enshō 896-973)

首山省念 Shoushan Shengnian (Shuzan Shōnen 926-993)

汾陽善昭 Fenyang Shanzhao (Fun'yo Zenshō 947-1024)

石霜/慈明 楚圓 Shishuang/Ciming Chuyuan (Sekisō/Jimei Soen 986-1039)

楊岐方會 Yangqi Fanghui (Yōgi Hōe 992-1049)

白雲守端 Baiyun Shouduan (Hakuun Shutan 1025-1072)

五祖法演 Wuzu Fayan (Goso Hōen 1024-1104)

圜悟克勤 Yuanwu Keqin (Engo Kokugon 1063-1135)

虎丘紹隆 Huqiu Shaolong (Kukyū Jōryū 1077-1136)

應庵曇華 Yingan Tanhua (Ōan Donge 1103-1163)

密庵咸傑 Mian Xianjie (Mittan Kanketsu 1118-1186)

松源崇岳 Songyuan Chongyue (Shōgen Sūgaku 1132-1202)

運庵普巖 Yunan Puyan (Un'an Fugan 1156–1226)

虛堂智愚 Xutang Zhiyu (Kidō Chigu 1185–1269)

南浦紹明 Nampo Jōmyō (1235-1308) [大應國師 Daiō Kokushi]

宗峰妙超 Shūhō Myōchō (1282-1337) [大燈國師 Daitō Kokushi

The Original Face

A SERMON BY DAITO KOKUSHI

Translated by Trevor Leggett

IN: A FIRST ZEN READER (PDF)

Charles E. Tuttle, Tokyo, 1960, pp. 19-22.

"THE ORIGINAL FACE" is a sermon delivered to the Empress Hanazono by Zen master Myocho, who is best known under the name bestowed upon him by the emperor: Daito Kokushi. Kokushi means literally "teacher of the nation." Daito (1281-1337) was one of the great lights of the Rinzai sect in Japan. He hid himself for some time, disguised as a beggar, to evade fame.

THE ORIGINAL FACE

ALL ZEN students should devote themselves at the beginning to zazen (sitting in meditation). Sitting in either the fully locked position or the half-locked position, with the eyes half-shut, see the original face which was before father or mother was born. This means to see the state before the parents were born, before heaven and earth were parted, before you received human form. What is called the original face will appear. That original face is something without colour or form, like the empty sky in whose clarity there is no form.

The original face is really nameless, but it is indicated by such terms as original face, the Lord, the Buddha nature, and the true Buddha. It is as with man, who has no name at birth, but afterwards various names are attached to him. The seventeen hundred koan or themes to which Zen students devote themselves are all only for making them see their original face. The World-honoured One sat in meditation in the snowy mountains for six years, then saw the morning star and was enlightened, and this was seeing his original face. When it is said of others of the ancients that they had a great realization, or a great breaking- through, it means they saw the original face. The Second Patriarch stood in the snow and cut off his arm to get realization; the Sixth Patriarch heard the phrase from the Diamond Sutra and was enlightened. Reiun was enlightened when he saw the peach blossoms, Kyogen on hearing the tile hit the bamboo, Rinzai when struck by Obaku, Tozan on seeing his own reflection in the water.

All this is what is called "meeting the lord and master." The body is a house, and it must have a master. It is the master of the house who is known as the original face. Experiencing heat and cold and so on, or feeling a lack, or having desires--these are all delusive thoughts and do not belong to the true master of the house. These delusive thoughts are something added. They are things which vanish with each breath. To be dragged along by them is to fall into hell, to circle in the six paths of reincarnation. By going deeper and deeper into zazen, find the source of the thoughts. A thought is something without any form or body, but owing to the conviction of those thoughts remaining even after death, man falls into hell with its many pains, or suffers in the round of this changing world.

Every time a thought arises, throw it away. Just devote yourself to sweeping away the thoughts. Sweeping away thoughts means performing zazen. When thought is put down, the original face appears. The thoughts are like clouds; when the clouds have cleared, the moon appears. That moon of eternal truth is the original face.

The heart itself is verily the Buddha. What is called "seeing one's nature" means to realize the heart Buddha. Again and again put down the thoughts, and then see the heart Buddha. It might be supposed from this that the true nature will not be visible except when sitting in meditation. That is a mistake. Yoka Daishi says: "Going too is Zen; sitting too is Zen. Speaking or silent, moving the body or still, he is at peace." This teaches that going and sitting and talking are all Zen. It is not only being in zazen and suppressing the thoughts. Whether rising or sitting, keep concentrated and watchful. All of a sudden, the original face will confront you.

![]()

Daitó Kokusi "Végső figyelmeztetései"

Fordította: Tóth Andrea

Daito (1282–1336): Intelmek"Ti, mindannyian, akik eljöttetek ehhez a hegyhez!

Ne felejtsétek el, hogy az Út miatt vagytok itt és nem

a ruházkodás vagy az élelem miatt! Ha van vállatok,

ruhában nem fogtok hiányt szenvedni; ha van szátok,

élelemben szintén nem lesz hiányotok. Arra törekedjetek

a nap minden órájában, hogy megismerjétek

a megismerhetetlent. Elejétől a végéig mindent

részletesen vizsgáljatok meg. Az idő úgy repül, akár

egy nyílvessző, tehát figyeljetek oda arra, hogy energiátokat

ne vesztegessétek el jelentéktelen dolgokra.

Legyetek figyelmesek! Legyetek figyelmesek!

Miután ennek az öreg szerzetesnek a zarándokútja

véget ér, közületek néhányan hatalmas

templomok vezetői lesztek, amelyek épülete csodálatos,

könyvtára óriási, arannyal és ezüsttel díszítettek,

és sok lelkes hívet szereztek majd magatoknak.

Mások talán a szútrák tanulmányozásának,

ezoterikus énekeknek, folytonos meditációnak és

az érzékelés szigorú megfigyelésének szentelik

életüket. Bármit is cselekedjetek, ha szellemeteket

nem a buddhák és a pátriárkák csodálatos és továbbvihetetlen

Útjának szentelitek, akkor megtagadjátok

az okságot és összeomlik a tanítás. Az

ilyen emberek ördögök és sohasem lehetnek igaz

követőim. Azok viszont, akik saját dolgaikkal foglalkoznak,

saját személyiségüket csiszolják, élhetnek

akár az ország legtávolabbi részén, ehetnek

akár nyers zöldségeket és élhetnek akár összetákolt

kunyhókban, mégis naponta találkoznak hagyományaimmal

és hálásan fogadják tanításomat.

Ki tehetné meg ezt könnyedén? Dolgozzatok keményebben!

Dolgozzatok keményebben!"

Szerzetesek, kik ebben a hegyi kolostorban éltek, emlékezzetek rá: a val-

lás miatt vagytok itt, nem pedig étel, ruha és szál ás gyanánt. Amíg éltek,

lesz mit viselnetek; amikor éhesek vagytok, lesz mit ennetek. A nap tizen-

két órájában legyetek éberek, és az Elgondolhatatlan tanulmányozásának

szenteljétek magatokat. Az idő nyílvesszőként suhan; soha ne zavartassá-

tok magatokat világi gondokkal. Mindig legyetek éberek. Miután eltávoz-

tam, talán némelyetek ( tanítóként) öt templom dolgairól fog dönteni, ben-

nük csarnokok és könyvtárszoba is lesz, mind gazdagon díszítve, nyüzsgő

tömegtől körülvéve; vagy talán szútrák olvasásával és énekek kántálásával,

hosszú elmélyedéssel lesz elfoglalva, kevés alvással, napi egyszeri étkezéssel,

koplalással töltve a hat napszakot, egyre csak az előírtak szerint.

Bármilyen buzgó módon is gyakorolnak, ha az erényt és annak következ-

ményeit figyelmen kívül hagyják, akkor nem a Buddhák és az Ősatyák

rejtélyes, nem elmondható útját járják; így az igaz val ás tökéletes bukása

jő el. Ők az ártó szellemek családjába tartoznak, és bármily sok idő is telt

el távozásom óta, akkor sem hívhatók szellemi örököseimnek. De bizto-

san akad valaki, aki, mégha az erdőben, egy rozzant fakunyhóban tengeti

is életét, vadvirágok gyökerét főzve egy törött lábú bográcsban, ha a saját

szellemi útjára fordítja minden figyelmét, a velem való mindennapi kap-

csolatában megérti majd, milyen hálás is lehet ezért. Ugyan ki nézné le az

ilyen embert? Gyakoroljatok hát szorgalmasan!

Daito utolsó verse

A Buddhák és Ősatyák vágják,

A kard legyen mindig éles!

Ahol fordul a kerék,

Ott az üresség vicsorog.