ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

絶海中津 Zekkai Chūshin (1336-1405)

Zekkai Chūshin (1336-1405) became Musō’s disciple at the Tenryūji

in 1348 and, like Guchū, studied under Shun’ya; he also studied with

Ryūzan Tokken (1284-1358), whom historians pair with Sesson as a

bringer of firsthand knowledge of China. In 1364 he left Kyoto to live

in Kamakura among Gidō’s followers. In 1368, the year of the

founding of the Ming, he went to China, remaining until 1376. His

pilgrimage is important especially because it took place at a time

when new missionaries were no longer coming to Japan. Zekkai

enjoyed the favor of Gidō’s shogunal patrons, the shogun Yoshimitsu

and the shogunal deputy Motouji, and later of Yoshimitsu’s

successor, Yoshimochi. Because of his facility in writing the parallel

prose used for elegant state documents, he was chosen to compose

the letter that Yoshimitsu sent in 1401 to the Yung-lo emperor (but

the letter ultimately proved to be a source of humiliation, for it was

criticized by rivals as injurious to the national dignity). On another

occasion he was sent as emissary to remonstrate with a rebellious

vassal. Zekkai, excitable and emotional, opposed his Ashikaga

masters on occasion, and several times fled them into retirement.

After Gidō’s death, Zekkai succeeded him as leader of Musō’s

school. Gido and Zekkai are called the “two jewels” of gozan

bungaku. Of all the gozan poets it is undeniably Zekkai who is the

most accomplished, whose poems are consistently sustained

compositions rather than collections of brilliant couplets. A Ming

monk wrote preface and afterword to the anthology of his writings,

and among the men who praised them for the purity of their Chinese

was Sung Ching-lien (1310-81, also called Sung Lien). The seeds of

the decline of gozan bungaku can be seen in Zekkai’s work. His

subject matter is entirely secular; long verses are architectonically

constructed of learned allusions. His willingness to put his literary

talents to the service of the government portends a time when gozan

monks will abandon religion to become clerks.

All of his poems in the present selection were written in China.

Poems of the five mountains: an introduction to the literature of the Zen monasteries

by Marian Ury. — Rev. 2nd ed.

(Michigan monograph series in Japanese studies ; no. 10)

1992, Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan

An Old Temple

Which way did it face? this ancient temple gate,

Wisteria vines deep on all four walls.

Flowers near the eaves lie crushed after the rains;

Wild birds sing for the visitor alone;

Grass engulfs the seat of the World-Honored One,

And from its base has melted the patron’s gold.

These broken tablets show no years or months —

Hard to tell whether they’re from T’ang or Sung.

Ascending a High Building after Rain

Passing showers have filled the sky and washed the new autumn;

With my friend hand-in-hand I climb the tower above the river,

Wishing a remembrance of Chung-hsüan’s ancient regret —

In the broken mist and scattered trees, my unendurable sorrow.Chung-hsüan was the tz’u, “style,” of Wang Ts’an (AD. 177-217), whose famous

Teng-lou fu (“Essay in Rhyme on Ascending the Tower”) expressed his

homesickness for Ch’ang-an.

Mist on the River

The single band of the river’s flow steeps heaven in coolness,

Distant and nearby peaks have merged in the autumn mist;

It seems with green gauze they’d bar men’s view —

The queens of the water, too modest to show their lovely selves.The “queens of the water” are the two daughters of the legendary emperor Yao

who became consorts of his successor Shun and drowned themselves after the

latter’s death. They were popularly venerated as goddesses of the Hsiang River.

Recording My Longings at the Beginning of Autumn

At the first cries of wild geese from borderland, evening dew thickens:

The wayfarer feels yet again how the years have gone by —

Once a summons to An-chi was entrusted to a crane;

Though centuries pass, Hsü Fu’s boat has not returned.

In southern mountains the purple-beans lie wasted in the long rains;

By northern lakes the red lotuses have shed their blooms in the clear autumn.

Fond you may be of tours, but they make a man age:

Chi-tzu, cease your aversion for your five-acre field!Line 1: Dew so heavy and extensive that the fields appear white characterizes the

north Chinese autumn.Lines 3-4: An-chi Sheng was a Taoist magician who claimed to have the secret

of immortality. The First Emperor of the Ch’in talked with him for three days and

nights, but he refused to divulge it and departed, telling the emperor to send for

him in the islands of the immortals in the eastern sea. The emperor despatched

Hsü Fu with 3,000 youths and maidens to bear him a letter (an imperial summons

to a Taoist adept, called a “crane-letter”) and bring back the herbs of immortality.

The legend is that Hsu Fu went to Japan, where he yet remains.Line 8: Chi-tzu was the tz’u of Su Ch’in, the minister who forged the so-called

vertical alliance of six states during the Warring States period. He had once been

poor, scorned even by his relatives for traveling in search of employment, but after

attaining power he returned to his village and said: “If you would have me be

wealthy with a five-acre field near the capital, what do you think of my possessing

the ministerial seals of six states?”

Rhyme Describing the Three Mountains,

Composed in Response to the Imperial CommandBefore Kumano’s peak is Hsü Fu’s shrine,

The mountains are rich with herbs grown lush after rain,

And now upon the sea the billowing waves are calm:

Kind winds a myriad miles will speed him home.During his visit to China, Zekkai was called before Emperor T’ai-tsu of the Ming

and questioned about his homeland — in particular, about the site in Kumano

where Hsü Fu was said to be buried. Zekkai responded with a poem in which the

calm sea is made to symbolize the tranquility of T’ai-tsu’s reign, so benign that Hsü

Fu will at long last return to China with his precious cargo. The “Three Mountains”

of the title are, of course, Japan (see p. 45).

Zekkai's Dharma Lineage

[...]菩提達磨 Bodhidharma, Putidamo (Bodaidaruma ?-532/5)

大祖慧可 Dazu Huike (Taiso Eka 487-593)

鑑智僧璨 Jianzhi Sengcan (Kanchi Sōsan ?-606)

大毉道信 Dayi Daoxin (Daii Dōshin 580-651)

大滿弘忍 Daman Hongren (Daiman Kōnin 601-674)

大鑑慧能 Dajian Huineng (Daikan Enō 638-713)

南嶽懷讓 Nanyue Huairang (Nangaku Ejō 677-744)

馬祖道一 Mazu Daoyi (Baso Dōitsu 709-788)

百丈懷海 Baizhang Huaihai (Hyakujō Ekai 750-814)

黃蘗希運 Huangbo Xiyun (Ōbaku Kiun ?-850)

臨濟義玄 Linji Yixuan (Rinzai Gigen ?-866)

興化存獎 Xinghua Cunjiang (Kōke Zonshō 830-888)

南院慧顒 Nanyuan Huiyong (Nan'in Egyō ?-952)

風穴延沼 Fengxue Yanzhao (Fuketsu Enshō 896-973)

首山省念 Shoushan Shengnian (Shuzan Shōnen 926-993)

汾陽善昭 Fenyang Shanzhao (Fun'yo Zenshō 947-1024)

石霜/慈明 楚圓 Shishuang/Ciming Chuyuan (Sekisō/Jimei Soen 986-1039)

楊岐方會 Yangqi Fanghui (Yōgi Hōe 992-1049)

白雲守端 Baiyun Shouduan (Hakuun Shutan 1025-1072)

五祖法演 Wuzu Fayan (Goso Hōen 1024-1104)

圜悟克勤 Yuanwu Keqin (Engo Kokugon 1063-1135)

虎丘紹隆 Huqiu Shaolong (Kukyū Jōryū 1077-1136)

應庵曇華 Yingan Tanhua (Ōan Donge 1103-1163)

密庵咸傑 Mian Xianjie (Mittan Kanketsu 1118-1186)

破庵祖先 Poan Zuxian (Hoan Sosen 1136–1211)

無準師範 Wuzhun Shifan (Bujun Shipan 1177–1249)

無學祖元 Wuxue Zuyuan (Mugaku Sogen 1226-1286)

高峰顯日 Kōhō Kennichi (1241–1316)

夢窓疎石 Musō Soseki (1275-1351) [夢窓国師 Musō Kokushi]

絶海中津 Zekkai Chūshin (1336-1405)

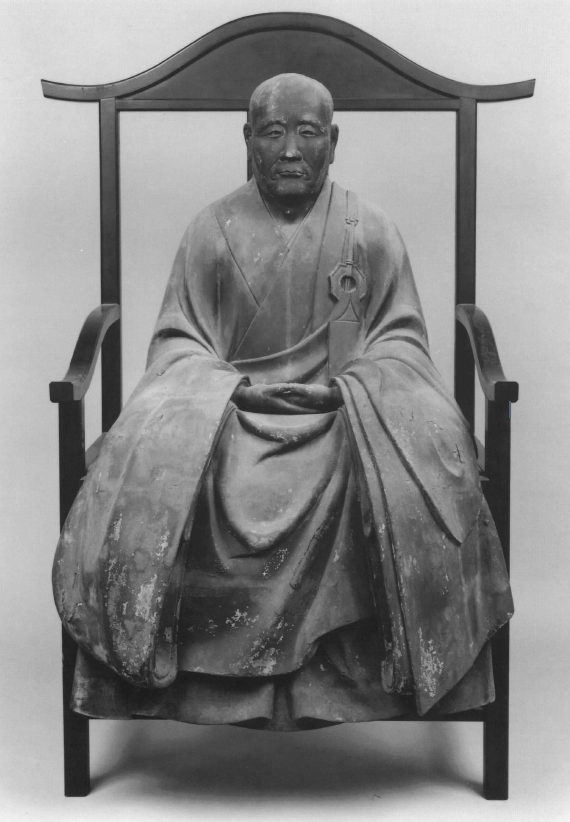

Portrait Statue of the Japanese Zen Master Zekkai Chūshin (1336-1405)

Anonymous. Early 15th century.

Wood with remains of pigment.

H. 65.2 cm.

Jisai'in, Tenryuji, Kyoto. ōūThe portrait statue at Jisai'in of Tenryuiji

depicts the illustrious Zen master Zekkai

Chūshin, considered - together with his

friend Gidō Shūshin (1325-1388) - to be

the most prominent representative of

gozan literature. The two monks are often

called "The Shining Double Jewels",

sbheki, of the gozan bungaku movement.

The sculpture is made of Japanese

cypress, hinoki, of which several blocks

were joined together in the yosegi technique.

The eyes are inlaid with rock-crystal,

gyokugan kannyū. Only traces of the

original pigmentation are left. Most likely,

the sculpture was carved soon after the

death of the master, at the beginning of

the fifteenth century. The face of the

sculpture emanates the determined,

uncompromising character of this proud

man, who could be dismissive and gruff,

sometimes even daring to resist instructions

by official authorities. At times,

Zekkai Chūshin led the life of a scholar

and poet recluse away from the capital,

disappointed at the political disorder, his

disagreement with the Ashikaga Shogun

Yoshimitsu (1358-1408, reigned 1367-

1394), and the unworthy factional quarrels

among the disciples of his teacher Musō

Soseki (1275-1351). Toward the end of

the fourteenth century, however, he took

an active and decisive part in metropolitan

Zen in his capacity as soroku, "Registrar

General of Monks", to whom all monasteries

and the clergy of the extensive gozan

network were subject.

The anonymous sculptor has rendered

Zekkai Chu-shin seated in the conventional

posture with his legs crossed and his

hands in his lap in the "seal of meditation",

zenjb'in. The master's head is large and

oval. Deep creases in the cheeks and at

the corners of the mouth characterize the

sagging facial skin of the old, bald-headed

prelate. Smaller, horizontal lines show the

furrows in his high forehead. The forceful

chin and the determined mouth are especially

striking as individual traits. It would

seem that Zekkai Chu-shin was crosseyed.

Over the monk's robe, he wears a

kesa on a cord knotted to an octagonal

ring. The robe hangs over his knees in

deep diagonal and V-shaped folds, in contrast

to the smooth surface-planes of the

robe on the torso and on the long sleeves.

The statue, originally at Shokei'in, a cloister

founded by Zekkai Chu-shin, was sold,

along with the building, to the city of Kobe.

In 1941, the portrait was brought to

Jisai'in at Tenryuijiin Kyoto, together with

the printing blocks of the Shbkenkb, the

two-volume anthology of the master, containing

163 poems and 38 prose pieces.

Two years later, the sculpture underwent

careful restoration work.Zen - masters of meditation in images and writings

by Helmut Brinker [1939–2012]; Hiroshi Kanazawa [金沢 比呂司 1937-]

Museum Rietberg; Artibus Asiae, Zürich, 1996, 244 p.

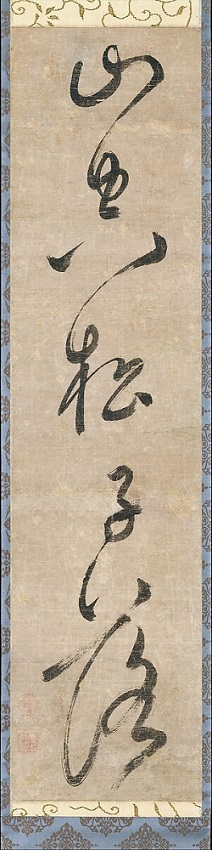

「山空松子落」 “The Mountain is Empty; A Pinecone Falls” 87.6 x 21.7 cm

This single column of cursive script by Zekkai Chūshin quotes a longer poem by the Tang-dynasty poet Wei Yingwu (737–790) that captures the experience of deep solitude in the mountains. Zekkai first studied Zen as a teenager at Tenryūji, a major monastery in western Kyoto that Musō Soseki (whose work hangs nearby) had established just a few years earlier; he then joined Musō at nearby Saihōji. In his thirties he journeyed to China, where he studied Zen at storied monasteries in Hangzhou such as Wanshousi and Lingyinsi. He returned to Japan a decade later and briefly practiced in seclusion before accepting abbotships at several major monasteries in Kyoto. Recognized as one of Musō’s most influential disciples, he is also celebrated for his achievements in poetry.

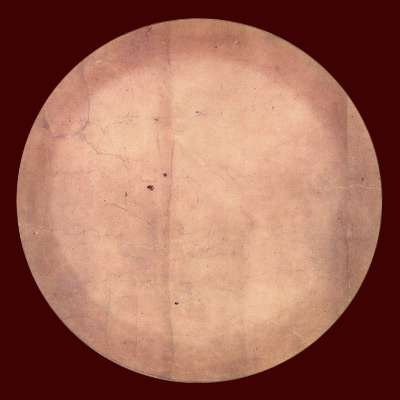

The Ten Oxherding Pictures

Traditionally attributed to 天章周文 Tenshō Shūbun (1414-1463)

Ten round paintings mounted in one handscroll, 32.8 x 186.7 cm.

Shokokuji, Kyoto

PDF: Zen painting & calligraphy by Fontein, Jan

Boston : Museum of Fine Arts, 1971

pp. 113-118.

The Ch'an, unlike many other Buddhist sects, did not consider Enlightenment the final result of a gradual development whose every phase could be analyzed and differentiated. Rather, Enlightenment was viewed as an instantaneous revelation not preceded by preliminary stages in which the Truth was revealed step by step. According to Sung accounts, the ancient masters of the T'ang period achieved Enlightenment with a minimum of guidance. In later times, however, when the study of koan had become a standard method of re-creating the circumstances for attaining that ineffable experience, it gradually became evident that there are recognizable degrees in man's ability to grasp the essence of Ch'an truth. In addition, the Ch'an adepts realized that there are definite degrees of Enlightenment itself, and that the final, absolute awakening is preceded by preliminary stages.

In guiding their pupils, Ch'an masters relied on parables, examples, and symbols. One way of facilitating the process of "seeing into one's own nature to become a Buddha" was by studying a tenfold parable known as The Ten Oxherding Songs that explained, allegorically, the different possible degrees of understanding of the Ch'an doctrine. The Ch'an monk- and lay-authors who set down the parable in written form found a precedent in the doctrine of The Five Ranks developed by Tung-shan Liang-chieh (807-869). This philosophical system was symbolically represented by circles with segments ranging from black to pure white. In commentaries, the dialectics of The Five Ranks were expressed in terms of lords and vassals. Although The Five Ranks and The Ten Oxherding Songs are not related philosophically, their use of parables and of abstract symbols in black and white are very similar.

In choosing the ox and its herdsman for their parables, the authors of the Ten Oxherding Songs followed an ancient Buddhist tradition which can be traced back all the way to India. A Hina- yana sutra on the Herding of Cattle describes eleven ways of tending cows and compares these with the different duties of a Buddhist monk. In Tibet, where the word glan can mean both cow and elephant, representations of the mahout and his mount elaborately illustrate a tenfold allegorical story of a comparable genre by Blo-bzan don-yod (lBth-iyth century).

The "Recorded Sayings" of the great Ch'an masters abound with references to cows and oxen. The koan of Po-chuang Huai-hai (720-814) is well known. It likens the search for Buddha- hood to the paradox of looking for an ox while riding on it, and the attainment of this goal to riding home on it. This koan and similar stories must have provided the inspiration for the Ten Oxherding Songs.

The earliest of these songs were written in China during the middle of the eleventh century, and the vogue for composing them lasted more than a hundred years. At least a dozen sets of Oxherding Songs seem to have been written.

The woodblock prints that illustrated the books in which the songs initially were printed served as a source of inspiration for artists in other media. The songs by the Northern Sung official Yang Chieh, an amateur painter of the "untrammelled" class, provided the inspiration for a huge representation of the parable carved from the living rock at Mount Pao-ting in Szechwan. This is, in all probability, the only Ch'an stone sculpture on a monumental scale.

The earliest songs, which were written by Ch'ing-chu (ca. 1050), have been incompletely preserved. However, there is a complete set composed by the Ch'an master P'u-ming —not to be confused with the monk-painter Hsiieh- chuang who had the same sobriquet— which is almost contemporary with that of Ch'ing-chu. One of the interesting features of P'u-ming's set is that the ox's color changes gradually through the ten stages from pitch-black to snow-white. This feature obviously was borrowed from The Five Ranks.

Of the several sets of Chinese illustrations of the theme, only two seem to have gained widespread popularity. In China, the version of P'u-ming was the most popular and^continued to be reprinted for several centuries after his death. In Japan, on the other hand, it was the version written and illustrated by Kuo-an (ca. 1150) that was especially admired. Kuo-an's text, where the actual process of attaining Enlightenment is divided into eight stages, inclined towards the doctrine of "sudden” Enlightenment, whereas P'u-ming's represents the ideas of the so-called "gradual" school of thought, which found many adherents among the Chinese.

Japanese monks brought back copies of Kuo-an's book, which was republished in a number of different editions. One of the earliest may date from about 1325. During the next hundred years as many as five different editions appeared, which indicates the widespread popularity of the theme. One edition bears a date corresponding to 1419. Painted versions, such as this handscroll, seem to be rare and this is the oldest extant example. The Hoshun'in at the Daitokuji has an example dating from the first half of the seventeenth century.

The set illustrated here was handed down to the present time in the Shokokuji, the temple where the famous painter Shūbun lived during the second quarter of the fifteenth century. For this reason, it is not surprising that the hand-scroll came to be associated with his name. However there is no evidence to support an attribution to him.

The same temple has a set of mounted inscriptions from the hand of Zekkai Chūshin (see cat. no. 38) that consists of the complete text of Kuo-an's Ten Oxherding Songs. In 1395 when Zekkai Chūshin was asked to explain the tenets of Ch'an Buddhism to the Shogun Ashikaga Yoshi-mitsu, he used Kuo-an's Ten Oxherding Songs as a textbook for the lessons. His set of inscriptions is thought to have been written for that important occasion. They have no connection with the set of paintings.

Each section of the Ten Oxherding Songs consists of an explanatory prose paragraph followed by four lines in verse in which the same ideas are once more expressed. For the sake of brevity, only the prose paragraphs have been translated here, but several complete English translations exist (see References).

1) Looking for the Ox

To begin with, we never really lost him, so what is the use of chasing him and looking-for him? The herdsman turned his back on himself and so became estranged from his ox. It moved away into clouds of dust and was lost.

The herdsman's home and mountains recede into the far distance; the mountain paths and roads suddenly become confused. The desire to catch the ox and the fear of losing him burn like fire; doubts assail him about the right course to take.

2) Seeing the Footprints of the Ox

By relying on the sutras and explaining their meaning, he carefully studies the doctrine and begins to understand the first signs. He realizes that all vessels [of the Law] are made of one metal and that the Ten Thousand Things are composed of the same substance as he himself. But he does not yet distinguish between right and wrong doctrines, between truth and falsehood. He has not yet entered that gate. He has discovered the footprints of the ox, but that discovery is, as yet, only tentative.

3) Seeing the Ox

Following the sound [of the mooing of the ox] he enters the gate. He sees what is inside and gets a clear understanding of its nature. His six senses are composed and there is no confusion. This manifests itself in his actions. It is like salt in seawater or glue in paint [invisible, indivisible, yet omnipresent]. He has only to lift his eyebrows and look up to realize that there is nothing here different from himself.

4) Catching the Ox

The ox has been hiding in the wilderness for a long time, but the herdsman finally discovers him near a ditch. He is difficult to catch, however, for the beautiful wilderness still attracts him, and he still keeps longing for the fragrant grasses. His obstinate heart still asserts itself; his unruly nature is still alive. If the herdsman wants to make him submissive, he certainly will have to use the whip.

5) Herding the Ox

As soon as one idea arises, other thoughts are bound to follow. Through Enlightenment all these thoughts turn into truth, but when there is delusion they all turn into falsehood. These thoughts do not come from our environment, but only from within our own heart. One must keep a firm hold on the nose-cord and not waver.

6) Returning Home on the Back of the Ox The battle is over. There is no longer any question of finding or losing the ox. Singing a woodcutter's pastoral song and playing a rustic children's melody on his flute, the herdsman sits sideways on the ox's back. His eyes gaze at the clouds above. When called he will not turn around, when pulled he will not halt.

7) The Ox Forgotten, the Man Remains There is but one Dharma, and the ox represents its guiding principle. It illustrates the difference between the hare net [and the hare] and elucidates the distinction between the fish trap [and the fish]. [This experience] is like gold being extracted from ore or like the moon coming out of the clouds: one cold ray of light, or an awe-inspiring sound from beyond the aeons of time.

8) Both Man and Ox Forgotten

All desire has been eliminated; religious thoughts have all become void. There is no use to linger on where the Buddha resides; where no Buddha exists one must quickly pass by.

One is no longer attached to either, and even a thousand eyes will find it difficult to detect it. The Hundred Birds bringing flowers in their beaks are nothing more than a farce on real sanctity.

9) Returning to the Fundamental, Back to the Source

Clear and pure from the beginning, without even a speck of dust, he observes the growth and decay of forms, remaining in the immutable attitude of non-activity. He does not identify himself with transitory transformations, so why should he continue the pretense of self-disciplining? The water is blue, the mountains are green. Sitting by himself he observes the ebb and flow, the rhythm of the Universe.

10) Entering the City with Hands Hanging Down

The Brushwood Gate is firmly closed, and the thousand sages are unaware of his presence.

He hides his innermost thoughts, and has turned his back on the well-trod path of the saints of antiquity. Picking up his gourd, he goes to the city; carrying his staff, he returns home. Visiting wineshops and fish stalls, his transforming presence brings Buddhahood to them all.

Even a cursory comparison between the painted handscroll and the woodblock illustrations of a printed edition of Kuo-an's text reveal the painter's close dependence on one of the printed prototypes. As the woodblock illustrations in the different editions of the book differ only in minor details, it does not seem possible, however, to establish which edition served as the artist's model. Adopting the same round format, the artist faithfully followed the basic compositional formulae of each of the ten pictures. The sharp lines in the herdsman's costume and the trees, as well as the elaborate structure of rock formations, are stylistic features derived directly from the woodblock illustrations.

The meaning of the first seven illustrations is evident; the eighth, an empty circle, is a fitting symbol of the Absolute. Ever since the days of Nan-yueh Huai-jang (677-744), the nature of Enlightened Consciousness had been expressed by this symbol. It was most fitting, therefore, that the entire set of pictures should be given this profoundly symbolic circular shape. The purity of the ninth stage is illustrated by representations of the Three Pure Ones: a rock, plum blossoms, and bamboo (see cat. no. 38).

The meaning of the tenth picture is somewhat obscure, especially because of the uncertain interpretation of the words that literally mean "with hands hanging down." Suzuki has translated them as "with bliss-bestowing hands," and this interpretation has been adopted by other translators. While arms hanging limply are supposed to signify respect, the gesture did not acquire this connotation until Ming times. Older texts suggest that it originally stood for something closer to the opposite of its later meaning, that it indicated independence, defiance, sometimes even rudeness. It would seem that this is what was meant here: Pu-tai has achieved a stage of Enlightenment where even entering wineshops and fish stalls cannot defile him, and behind the rude remarks he makes lies hidden wisdom. By paying homage to Pu-tai and following his examples, the herdsman reaches his final destination.

References:

D.T. Suzuki, Essays in Zen Buddhism, ist ser. (London, 1927), pp. 347-366; Shibayama Zenkei, jugyuzu (Tokyo, 1954); idem, Zen Oxherding Pictures (1967); M. H. Trevor, The Ox and his Herdsman (Tokyo, 1969); Shodo Zenshu, vol. 20 (Tokyo, i960), pis. 93-97; Goto Art Museum [Exhibition Catalogue], no. 23 (1963), nos. 2, 2A, 7-10.

The Ten Oxherding Pictures

Jūgyūzu

The first sets of "Ten Oxherding Pictures",

jūgyūzu, seem to have originated in China

around the middle of the eleventh century.

During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries,

a set of the theme with paintings

and text, going back to the Chan master

Guo'an Shiyuan (active around 1150), was

widely circulated in Japan and existed in

several handwritten and painted versions,

as well as in printed editions. In that work,

the steps on the steep road toward enlightenment

are presented in the following

similes:1. Looking for the Ox

2. Seeing the Footprints of the Ox

3. Seeing the Ox

4. Catching the Ox

5. Herding the Ox

6. Returning Home on the Back of the Ox

7. The Ox Forgotten, the Man Remains

8. Both Man and Ox Forgotten

9. Returning to the Fundamental, Back to the Source

10. Entering the City with Hands Hanging DownThese ten stages of the herdboy handling

the foolish ox were frequently illustrated in

hanging scrolls and handscrolls. The

round format was often preferred, since

the circle as a geometric figure without

beginning or end includes the elimination

of all opposites into absolute unity, i.e., the

"true void", shinkū. It points to the deep

"insight into one's own essential nature"

and symbolizes the fundamental character

- devoid of shape and colour - of all living

beings, simply but significantly alluded

to in Zen painting by the empty ground.

Thus, the eighth stage, "Both Man and Ox

Forgotten", i.e., all differences and opposites

have been dissolved in ultimate clarity,

is represented here, too, by an empty

circle. The return to the initially clear and

pure source of the true teaching is symbolized

in the ninth stage by the "Three

Pure Ones", bamboo, plum, and rock.

Finally, the enlightened adept goes among

the people, relaxed - "with hands hanging

down" - and far above worldly concerns,

cheerfully and without any want.

The work at Shōkokuji is the oldest extant

Japanese jūgyūzu. It is attributed by tradition

to Shūbun, who was active as official

painter, goyō eshi, of the Muromachi

Bakufu government during the first half of

the fifteenth century. However, judging

from the rigid spatial composition and the

somewhat formalized details, the handscroll

seems to date rather from the end of

the fifteenth century.

The "Oxherding" parable seems to have

been of special importance at Shōkokuji:

already toward the end of the fourteenth

century, the outstanding gozan poet-monk

Zekkai Chūshin (1336-1405) wrote a set of

poems for an "Oxherding" cycle which is

still extant at the monastery in ten hanging

scrolls.Zen - masters of meditation in images and writings

by Helmut Brinker [1939–2012]; Hiroshi Kanazawa [金沢 比呂司 1937-]

Museum Rietberg; Artibus Asiae, Zürich, 1996, 234 p.

![]()

https://www.persee.fr/doc/dhjap_0000-0000_1995_dic_20_1_956_t1_0133_0000_2