ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

夢窓疎石 Musō Soseki (1275-1351)

夢窓国師 Musō Kokushi ("national Zen teacher")

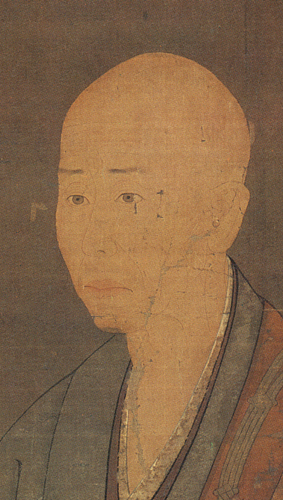

Half-Figure Portrait of Musō Soseki

by

無等周位

Mutō Shūi (active first half 14th century)

Inscription by Musō Soseki, ca. 1349/1350

Hanging scroll, ink and colours on silk, 119.4 × 63.9 cm

Myōchi'in, Tenryū-ji, Kyoto

Important Cultural Property

The distinguished Zen prelate Musō

Soseki is depicted here in a half-figure

portrait which he inscribed probably a few

years before his death. Half-figure portraits,

hanshinzi, painted during the lifetime

of the subject are relatively rare.

Medieval Japanese Zen artists reserved

the half-length format rather for the depiction

of patriarchs and founder figures

in ideal portraits long after the death of

the subject. Often, such portraits were

grouped together in voluminous sets.

The painting of Musō Soseki at Myōchi'in

of Tenryuji is the only extant painting by

the highly gifted painter-monk Mutō Shūi,

a pupil of the portrayed Zen master. His

signature along the lower right edge

reads: "By the brush of Mutō Shūi". Reliable

sources tell us that he painted his

master several times. The Mukyoku Oshō

den cites the colophon by Musō Soseki on

such a portrait by Mutō Shui which the

second Tenryiji abbot Mukyoku Shigen

(1282-1359) had commissioned in 1349,

at a time when his teacher and predecessor

was living at Saihōji. According to the

Tenryū Kaisan Kokushi shinsōki by Chūhō

Eni (1354-1413), Mutō Shūi had already

painted a portrait of his master in 1341,

also bearing a dated inscription by Muso

Soseki. This portrait was owned by the

Muso disciple Kyūō Fukan (1322-1410).

From other early sources we know of wall

painting cycles which Mutō Shūi painted

for monasteries in Kyōto. He seems to

have been one of the first Zen Buddhist

painter-monks who could sustain complex

atelier activities beside his clerical

duties.

Unusual for a Zen portrait, painted after

the living model around 1349/50, is that

Musō Soseki in three-quarter profile looks

toward the left, so that his five-line colophon,

adjusted against the direction of his

eyes, runs from left to right. The inscription

reads:

The lower parts [of the body from hips]

to heels cannot expound a theme.

Thus, there appears in the "Gate of

Erection and Change" kenkemon, [only

the upper] half of the body, hanshin.

Muso Soseki accuses himself.

Kenkemon is the gate to Zen accessible

by provisional methods and instruction.

They are tentative, sometimes unconventional

ways to guide unenlightened people,

to "erect" and to "change" them. The

colophon sounds almost like an apology

for the fact that the portrait is not a conventional

full-figure one; and that artist

and model preferred a half-figure portrait

which concentrates on the essential, the

facial features, while less important parts,

such as richly decorated robes, were

omitted.

Indeed, Mutō Shūi succeeded in capturing

the tolerant character and the progressive

spiritual attitude in the solemn

face of his illustrious master. This impressive

rendering is testament to the artist's

intense relationship with his model, his

sensitive perceptive grasp, and his talent

for conveying to the viewer the individuality

of the portrayed master by an interpretative

counterfeit. Sparse, fine lines and

delicate colours indicate the essential

details. A few ink lines describe the fall of

the steel-grey monk's robe. The seams of

the broad, rust-red strips of the kesa are

contrasted from the brown ground of the

stole by light washes. Such extremely

economical means give the figure volume

and convincingly render the textiles' specific

surface quality. The sophisticated

combination of subdued colours and few,

rhythmically coordinated lines show Mutō

Shūi's artistic genius. In its unobtrusive

overall effect, the work represents the

general style of Zen Buddhist portraiture in

Japan around the middle of the fourteenth

century, as it developed on the basis of

Song painting.

Zen - masters of meditation in images and writings

by Helmut Brinker [1939–2012]; Hiroshi Kanazawa [金沢 比呂司 1937-]

Museum Rietberg; Artibus Asiae, Zürich, 1996, 258 p.

Musō Soseki. (夢窓疎石) (1275–1351). Japanese ZEN master in the

RINZAISHŪ. A native of Ise, he became a monk at a young age and studied the

teachings of the TENDAISHŪ. Musō’s interests later shifted toward Zen and he

became the student of the Zen master KŌHŌ KENNICHI. After receiving

dharma transmission from Kōhō, Musō led an itinerant life, moving from one

monastery to the next. In 1325, he received a decree from Emperor Godaigo (r.

1318–1339) to assume the abbotship of the powerful monastery of NANZENJI in

Kyōto. The following year, he went to Kamakura, where he served as abbot of

the influential monasteries of Jōchiji, Zuisenji, and ENGAKUJI. Later, he

returned to Nanzenji at the request of the emperor. In 1333, Emperor Godaigo

triumphantly returned to Kyōto and gave Musō the monastery Rinsenji and the

title of state preceptor (kokushi; C. GUOSHI). After the emperor’s death in 1339,

Musō established the new monastery of TENRYŪJI with the help of the shōgun

Ashikakga Takauji (1305–1358) and became its founding abbot (J. kaisan; C.

KAISHAN). In this manner, Musō came to serve as abbot of many of the topranking

monasteries of the GOZAN system. His disciples came to dominate the

medieval Zen community and played important roles in the rise of gozan culture.

His teachings are recorded in the Musōroku, Musō hōgo, and MUCHŪ MONDŌ.

Musō 's Dharma Lineage

[...]

菩提達磨 Bodhidharma, Putidamo (Bodaidaruma ?-532/5)

大祖慧可 Dazu Huike (Taiso Eka 487-593)

鑑智僧璨 Jianzhi Sengcan (Kanchi Sōsan ?-606)

大毉道信 Dayi Daoxin (Daii Dōshin 580-651)

大滿弘忍 Daman Hongren (Daiman Kōnin 601-674)

大鑑慧能 Dajian Huineng (Daikan Enō 638-713)

南嶽懷讓 Nanyue Huairang (Nangaku Ejō 677-744)

馬祖道一 Mazu Daoyi (Baso Dōitsu 709-788)

百丈懷海 Baizhang Huaihai (Hyakujō Ekai 750-814)

黃蘗希運 Huangbo Xiyun (Ōbaku Kiun ?-850)

臨濟義玄 Linji Yixuan (Rinzai Gigen ?-866)

興化存獎 Xinghua Cunjiang (Kōke Zonshō 830-888)

南院慧顒 Nanyuan Huiyong (Nan'in Egyō ?-952)

風穴延沼 Fengxue Yanzhao (Fuketsu Enshō 896-973)

首山省念 Shoushan Shengnian (Shuzan Shōnen 926-993)

汾陽善昭 Fenyang Shanzhao (Fun'yo Zenshō 947-1024)

石霜/慈明 楚圓 Shishuang/Ciming Chuyuan (Sekisō/Jimei Soen 986-1039)

楊岐方會 Yangqi Fanghui (Yōgi Hōe 992-1049)

白雲守端 Baiyun Shouduan (Hakuun Shutan 1025-1072)

五祖法演 Wuzu Fayan (Goso Hōen 1024-1104)

圜悟克勤 Yuanwu Keqin (Engo Kokugon 1063-1135)

虎丘紹隆 Huqiu Shaolong (Kukyū Jōryū 1077-1136)

應庵曇華 Yingan Tanhua (Ōan Donge 1103-1163)

密庵咸傑 Mian Xianjie (Mittan Kanketsu 1118-1186)

破庵祖先 Poan Zuxian (Hoan Sosen 1136–1211)

無準師範 Wuzhun Shifan (Bujun Shipan 1177–1249)

無學祖元 Wuxue Zuyuan (Mugaku Sogen 1226-1286)

高峰顯日 Kōhō Kennichi (1241–1316)

夢窓疎石 Musō Soseki (1275-1351) [夢窓国師 Musō Kokushi]

黙庵周諭 Mokuan Shūyu (1318-1373)

夢中問答集 Muchū mondō-shū

PDF: Dream Conversations on Buddhism and Zen

Translated by Thomas ClearyPDF: Muso Kokushi's Dialogues in a Dream

Selections, Translated by Kenneth L. Kraft

The Eastern Buddhist, 14 (1981) 1, 75-93PDF: Dialogues in a Dream

Translated by Thomas Yūhō Kirchner

Tenryu-ji Institute for Philosophy and Religion, Kyoto, Japan, 2010, 256 pagesDialogues in a Dream is the first complete English translation of the Muchū Mondō, the best-known work of the eminent Japanese Zen master Musō Soseki (1275–1351). In ninety-three chapters Musō answers questions put to him by the shogun Ashikaga Tadayoshi (1306–1352) on a diverse range of topics, including esoteric rituals, Zen gardens, and ultimate enlightenment.

"Sermon at the Dedication of Tenryū-ji Dharma Hall'' (from 夢窓国師語錄 Musō Kokushi goroku)

by William Bodiford

in Sources of Japanese Tradition: Volume 1: From Earliest Times to 1600

ed. by Wm. Theodore de de Bary

pp. 328-330.The following sermon was delivered at the dedication of the Dharma Preaching Hall when Musō became the founding abbot of Tenryū-ji monastery, founded in memory of Go-Daigo. The dedication coincided with the anniversary of the Buddha’s birthday. Musō used this occasion to remind his audience that the truth preached by the Buddha, the truth proclaimed by the Zen ancestors, and the truth taught by Musō were all the very same truth. Thus, Sha¯kyamuni’s message of salvation is not ancient history but must be realized in this present moment at this very spot.

(In the tenth month of the second year of the Rekiō period [1339] a court decree ordered the conversion of the detached palace of Kameyama tennō [emperor] into a monastery dedicated to the memory of Go-Daigo tennō and also nominated Musō to be its founding abbot. In the fourth year of Kōei [1345], fourth month, eighth day, the Dharma Preaching Hall was opened for the first time, with their lordships Shogun Ashikaga Takauji and Vice-Shogun Tadayoshi in attendance. Musō first performed the ceremony celebrating the Buddha’s birth and then proceeded to say:)

The appearance in this world of all Buddhas, past, present, and future, is solely for the purpose of preaching the dharma that saves living beings. The Buddha used the arts of oratory and eight types of eloquence as the standards for his preaching the dharma, and the Deer Park and Vulture Peak both served as his halls of salvation. Our lineage of the Zen ancestors stresses the method of individual instruction directed toward the essential endowment, thus distinguishing itself from doctrinal schools. But examination of our aims reveals that we too focus solely on transmitting the dharma that saves the deluded. Thus all the ancestors, from the twenty-eight in India through the first six in China, each signaled his succession to the lineage with a dharma-transmission verse. The Great Master Bodhidharma said, ‘‘I came to China in order to transmit the dharma that saves deluded people.’’ So it is clear that Huike’s cutting off his arm in the snow and the conferring of the robe at midnight upon Huineng were both meant to signify the transmission of the marvelous dharma. In all kinds of circumstances, whether under a tree, upon a rock, in the darkness of a cave, or deep in a glen, there is no place where the dharma banner has not been erected and no place where the Mind Seal has not been transmitted to whoever possessed the spiritual capacity. Ever since Baizhang Huaihai founded the first Zen cloister, China and Japan have seen numerous grand Zen monasteries erected. All of them, whether large or small, have included a Dharma Preaching Hall for proclaiming the message of salvation. . . .

As for this mountain monk appearing before you today on this platform, I have nothing special to offer as my own interpretation of the dharma. I merely join with my true master, Shākyamuni Buddha, and with all others throughout infinite empty space, all Buddhas, bodhisattvas, holy ones, assembled clerics, patrons, and officials, the very eaves and columns of this hall, lanterns, and posts, as well as all the people, animals, plants, and seeds in the boundless ocean of existence to turn in unison the great Dharma Wheel. At this very moment, what is happening?

(Musō raised his staff high into the air.)

Look! Look!Shākyamuni is here right now on top of my staff. He takes seven steps, points to heaven and to earth, announcing to all of you:

Today I am born again here with the completion of this new Dharma Preaching Hall. All the holy ones are assembled here; people and gods mingle together. Every single person here is precious in himself, and everything here—plaques, paintings, square eaves and round pillars— every single thing is preaching the dharma. Wonderful, wonderful it is, that the true dharma lives and never dies. At Vulture Peak, indeed, this dharma was transmitted to the right man!

It is thus that Lord Shākyamuni, the most venerable, instructs us here. It is the teaching that comes down to men in response to their needs. But perhaps, gentlemen, you wish to kn o w the state of things before Shākyamuni ever entered his mother's womb.

(Musō tapped his staff on the floor.)

Listen, Listen![TD 80, no. 2555; 460c–461a; WB]

"Reflections on the Enmity Between Go-Daigo and the Shogun, Ashikaga Takauji'' (from 夢窓国師語錄 Musō Kokushi goroku)

by William Bodiford

in Sources of Japanese Tradition: Volume 1: From Earliest Times to 1600

ed. by Wm. Theodore de de Bary

pp. 330-332.This extract is from a sermon delivered by Musō upon resuming the office of abbot of Tenryū-ji in 1351, in which he reflects on the reasons for dedicating this monastery to the memory of Go-Daigo and analyzes the causes of the rupture between the latter and Ashikaga Takauji, his erstwhile supporter. He attributes the break to jealousy, which blinded Go-Daigo and estranged him from his obedient servant. Musō’s frank censure of the deceased sovereign shows both how low the prestige of the imperial house had fallen and how little awed by it was this Zen prelate, who considered it a purely human institution and not divine.

In the realm of True Purity, there is no such thing as self or other. How much less can friend or foe be found there! But the slightest confusion of mind brings innumerable differences and complications. Peace and disorder in the world, the distinction between friend and foe in human relationships, follow upon one another as illusion begets delusion. A person of spiritual luminosity will immediately recognize false thought and eliminate it, but the shallow-minded person will be enslaved by his own delusion so that he cannot put an end to it. In such cases one’s true friend may seem a foe and one’s implacable enemy may appear a friend. Enmity and friendship have no permanent character; both of them are illusions.

During the disorders of the Genkō period [1331–1334] the shogun, acting promptly on the court’s order, swiftly subdued the foes [the Hōjō regents] of the state, as a result of which he rose higher in court rank day by day and his growing prestige brought a change in the attitude of others toward him. Ere long, slander and defamation sprang up with the violence of a tiger, and this unavoidably drew upon him the royal displeasure. Consider now the reasons for this turn of events. It was because he performed a meritorious task with such dispatch and to the entire satisfaction of his sovereign. There is an old saying that intimacy invites enmity. That is what it was. Thereupon, the auspicious clouds of goodwill were scattered to the winds, and the august dragon [Go-Daigo] had to take refuge in the mountains to the south, where the music of the court was no longer heard and whence his royal phoenix palanquin could never again return to the northern court.

With a great sigh the military leader [Takauji] lamented, ‘‘Alas, due to slander and flattery by court ministers, I am consigned to the fate of an ignominious rebel without any chance to explain my innocence.’’ Indeed his grief was no perfunctory display, but without nurturing any bitterness in his heart, he devoutly gave himself over to spiritual reflection and pious works, fervently praying for the Buddhahood of Go-Daigo and subsequently constructing [in Go-Daigo’s memory] this grand monastery for the practice of great Buddha activity. . . .

The virtuous rule of Go-Daigo tennō accorded with Heaven’s will and his holy wisdom equaled that of the ancient sage-kings of China. Therefore the royal family’s fortunes rose high as reign and military power were unified. The phoenix reign inaugurated a new period of magnificence and splendor. Barbarians beyond the four borders were submissive and all within the borders were earnest. People compared his Yao-like reign to the wind, which always blows without end. Who, then, would have thought that his Shun-like sun would appear for only a moment and then immediately disappear behind the clouds? And what are we to make of it—was it merely a random turn of events? No, the fact that Go-Daigo expended all his karmic connections to this defiled world and straightaway joined the happy assembly of the Pure Land was not because his august reign lacked luck. It was because he caused the people so much suffering and distress. As a result, from the time of his passing right up to the present there has been no peace, clergy and laity alike have been displaced, and there is no end to the complaints of the people.

What I have expounded above is all a dream within a dream. Even though it actually happened, there is no use finding fault with what is past and done— how much less with what has happened in a dream! We must realize that a Wheel-Turning Monarch (cakravartin), the highest position among humans, is itself but something cherished in a dream. Even Brahmā, the highest king of the gods, knows only the pleasure of a dream. This is why Shākyamuni forsook the option of becoming a Wheel-Turning Monarch and entered the mountains to practice austerities. What was his purpose? To teach all people that the King of Awakening [Buddha] far surpasses the highest rank of human society. Although the four social classes differ, each member of them is like every other in being a disciple of the Buddha, and should behave accordingly.

I pray therefore that our late sovereign will instantly transform his defiled capacity, escape from the bondage of delusion, bid farewell to his karma-producing consciousness, and realize luminous wisdom. May he pass beyond the distinctions of friend and foe and attain the luminous region wherein delusion and awakening are one. May he not forget that the dharma transmission of Vulture Peak lives on and extend his protection to this monastery, so that without ever leaving this spot his blessings may extend to all living beings.

This is indeed the wish of the military leader [Takauji]. He bears no grudge toward Go-Daigo but merely wishes for him to develop favorable karmic causes, which is no trifling affair. The Buddhas in their great compassion will surely respond by bestowing mysterious blessings. In this way may the warfare come to an end, all the land within the four seas enjoy true peace, and all the people rest secure from disturbances and calamities. May [Takauji’s] military success pass on to his heirs, generation after generation. Our earnest prayer is that it should wash over all opposition.

[TD 80, no. 2555; 463c–464b; WB]

PDF: Not Seeing Snow: Musō Soseki and Medieval Japanese Zen

by Molly Vallor

Not Seeing Snow: Musō Soseki and Medieval Japanese Zen offers a detailed look at a crucial yet sorely neglected figure in medieval Japan. It clarifies Musō's far-reaching significance as a Buddhist leader, waka poet, landscape designer, and political figure. In doing so, it sheds light on how elite Zen culture was formed through a complex interplay of politics, religious pedagogy and praxis, poetry, landscape design, and the concerns of institution building. The appendix contains the first complete English translation of Musō's personal waka anthology, Shōgaku Kokushishū.

夢窓疎石 MUSO SOSEKI

in: Japanese Death Poems

Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death

compiled with an Introduction and commentary by YOEL HOFFMANN

Rutland, Vermont, Charles E. Tuttle Publishing, 1986, 368 p.

Died on the thirtieth day of the ninth month, 1351 at the age of seventy-seven

Thus have I rolled my life throughout

Inside and out, reclined, upright.

What is all this?

A beating drum

A trumpet's blare

No more.

PDF: Zen Buddhist Landscapes and the ldea of Temple: Muso Kokushi and Zuisen-Ji, Kamakura, Japan

by

Norris Brock Johnson

Arch. & Comport. /Arch. & Behav., Vol. 9, no. 2, p. 213-226 (1993)

PDF: Mountain, Temple, and the Design of Movement: Thirteenth-Century Japanese Zen Buddhist Landscapes

by

Norris Brock Johnson

PDF: Sun at Midnight: Poems and Sermons by Musō Soseki

Translated W. S. Merwin & Sōiku Shigematsu

North Point Press, San Francisco, 1989

Tōki-no-Ge (Satori Poem)

Year after year

I dug in the earth

looking for the blue of heavenonly to feel

the pile of dirt

choking meuntil once in the dead of night

I tripped on a broken brick

and kicked it into the airand saw that without a thought

I had smashed the bones

of the empty sky

Musō Soseki

by Martin Collcutt

Chapter 12 in "The Origins of Japan's Medieval World: Courtiers, Clerics, Warriors, and Peasants in the Fourteen Century".

Edited by Jeffrey P. Mass,

Stanford, 1997, pp. 261-294.

A Zen Life in Nature: Musō Soseki in His Gardens

by Andrew Keir Davidson

University of Michigan, Center for Japanese Studies, Ann Arbor, Mich. 2007

夢窓疎石 : 日本庭園を極めた禅僧

"Muso Soseki: Nihon teien wo kiwameta zenso" (Translation: "Muso Soseki: The Zen Priest who Mastered the Japanese Garden")

by Masuno Shunmyō, NHK Books, 2005.

Gardens by Musō Soseki

http://www.jgarden.org/biographies.asp?ID=21

The following is a list of gardens known to have been by Musō Soseki or attributed to him. However, whatever Soseki built was destroyed during the Ōnin War, and therefore any modern version is someone else's work.

Saihō-ji, better known as Koke-dera in Kyoto - UNESCO World Heritage Site, and one of Japan's Special Places of Scenic Beauty

Tenryū-ji in Kyoto - UNESCO World Heritage Site, and one of Japan's Special Places of Scenic Beauty

Eihō-ji in Tajimi, Gifu Prefecture - One of Japan's Places of Scenic Beauty

Erin-ji, in Yamanashi Prefecture - One of Japan's Places of Scenic Beauty

Zuisen-ji in Kamakura - One of Japan's Places of Scenic Beauty

Jōchi-ji

Engaku-ji in Kamakura

Tōnanzen-in in Kyoto

Rinsen-ji in Kyoto

JIKININKI

In:

Kwaidan*: Stories and Studies of Strange Things

by Lafcadio Hearn

Boston; Houghton, Mifflin and Co.

[1904]

*(怪談, Kaidan, literally "ghost stories")

Once, when Muso Kokushi, a priest of the Zen sect, was journeying alone through the province of Mino (1), he lost his way in a mountain-district where there was nobody to direct him. For a long time he wandered about helplessly; and he was beginning to despair of finding shelter for the night, when he perceived, on the top of a hill lighted by the last rays of the sun, one of those little hermitages, called anjitsu, which are built for solitary priests. It seemed to be in ruinous condition; but he hastened to it eagerly, and found that it was inhabited by an aged priest, from whom he begged the favor of a night's lodging. This the old man harshly refused; but he directed Muso to a certain hamlet, in the valley adjoining where lodging and food could be obtained.

Muso found his way to the hamlet, which consisted of less than a dozen farm-cottages; and he was kindly received at the dwelling of the headman. Forty or fifty persons were assembled in the principal apartment, at the moment of Muso's arrival; but he was shown into a small separate room, where he was promptly supplied with food and bedding. Being very tired, he lay down to rest at an early hour; but a little before midnight he was roused from sleep by a sound of loud weeping in the next apartment. Presently the sliding-screens were gently pushed apart; and a young man, carrying a lighted lantern, entered the room, respectfully saluted him, and said:—

"Reverend Sir, it is my painful duty to tell you that I am now the responsible head of this house. Yesterday I was only the eldest son. But when you came here, tired as you were, we did not wish that you should feel embarrassed in any way: therefore we did not tell you that father had died only a few hours before. The people whom you saw in the next room are the inhabitants of this village: they all assembled here to pay their last respects to the dead; and now they are going to another village, about three miles off,—for by our custom, no one of us may remain in this village during the night after a death has taken place. We make the proper offerings and prayers;—then we go away, leaving the corpse alone. Strange things always happen in the house where a corpse has thus been left: so we think that it will be better for you to come away with us. We can find you good lodging in the other village. But perhaps, as you are a priest, you have no fear of demons or evil spirits; and, if you are not afraid of being left alone with the body, you will be very welcome to the use of this poor house. However, I must tell you that nobody, except a priest, would dare to remain here tonight."

Muso made answer:—

"For your kind intention and your generous hospitality, I and am deeply grateful. But I am sorry that you did not tell me of your father's death when I came;—for, though I was a little tired, I certainly was not so tired that I should have found difficulty in doing my duty as a priest. Had you told me, I could have performed the service before your departure. As it is, I shall perform the service after you have gone away; and I shall stay by the body until morning. I do not know what you mean by your words about the danger of staying here alone; but I am not afraid of ghosts or demons: therefore please to feel no anxiety on my account."

The young man appeared to be rejoiced by these assurances, and expressed his gratitude in fitting words. Then the other members of the family, and the folk assembled in the adjoining room, having been told of the priest's kind promises, came to thank him,—after which the master of the house said:—

"Now, reverend Sir, much as we regret to leave you alone, we must bid you farewell. By the rule of our village, none of us can stay here after midnight. We beg, kind Sir, that you will take every care of your honorable body, while we are unable to attend upon you. And if you happen to hear or see anything strange during our absence, please tell us of the matter when we return in the morning."

All then left the house, except the priest, who went to the room where the dead body was lying. The usual offerings had been set before the corpse; and a small Buddhist lamp—tomyo—was burning. The priest recited the service, and performed the funeral ceremonies,—after which he entered into meditation. So meditating he remained through several silent hours; and there was no sound in the deserted village. But, when the hush of the night was at its deepest, there noiselessly entered a Shape, vague and vast; and in the same moment Muso found himself without power to move or speak. He saw that Shape lift the corpse, as with hands, devour it, more quickly than a cat devours a rat,—beginning at the head, and eating everything: the hair and the bones and even the shroud. And the monstrous Thing, having thus consumed the body, turned to the offerings, and ate them also. Then it went away, as mysteriously as it had come.

When the villagers returned next morning, they found the priest awaiting them at the door of the headman's dwelling. All in turn saluted him; and when they had entered, and looked about the room, no one expressed any surprise at the disappearance of the dead body and the offerings. But the master of the house said to Muso:—

"Reverent Sir, you have probably seen unpleasant things during the night: all of us were anxious about you. But now we are very happy to find you alive and unharmed. Gladly we would have stayed with you, if it had been possible. But the law of our village, as I told you last evening, obliges us to quit our houses after a death has taken place, and to leave the corpse alone. Whenever this law has been broken, heretofore, some great misfortune has followed. Whenever it is obeyed, we find that the corpse and the offerings disappear during our absence. Perhaps you have seen the cause."

Then Muso told of the dim and awful Shape that had entered the death-chamber to devour the body and the offerings. No person seemed to be surprised by his narration; and the master of the house observed:—

"What you have told us, reverend Sir, agrees with what has been said about this matter from ancient time."

Muso then inquired:—

"Does not the priest on the hill sometimes perform the funeral service for your dead?"

"What priest?" the young man asked.

"The priest who yesterday evening directed me to this village," answered Muso. "I called at his anjitsu on the hill yonder. He refused me lodging, but told me the way here."

The listeners looked at each other, as in astonishment; and, after a moment of silence, the master of the house said:—

"Reverend Sir, there is no priest and there is no anjitsu on the hill. For the time of many generations there has not been any resident-priest in this neighborhood."

Muso said nothing more on the subject; for it was evident that his kind hosts supposed him to have been deluded by some goblin. But after having bidden them farewell, and obtained all necessary information as to his road, he determined to look again for the hermitage on the hill, and so to ascertain whether he had really been deceived. He found the anjitsu without any difficulty; and, this time, its aged occupant invited him to enter. When he had done so, the hermit humbly bowed down before him, exclaiming:—"Ah! I am ashamed!—I am very much ashamed!—I am exceedingly ashamed!"

"You need not be ashamed for having refused me shelter," said Muso. "You directed me to the village yonder, where I was very kindly treated; and I thank you for that favor.

"I can give no man shelter," the recluse made answer;—and it is not for the refusal that I am ashamed. I am ashamed only that you should have seen me in my real shape,—for it was I who devoured the corpse and the offerings last night before your eyes... Know, reverend Sir, that I am a jikininki, [1]—an eater of human flesh. Have pity upon me, and suffer me to confess the secret fault by which I became reduced to this condition.

"A long, long time ago, I was a priest in this desolate region. There was no other priest for many leagues around. So, in that time, the bodies of the mountain-folk who died used to be brought here,—sometimes from great distances,—in order that I might repeat over them the holy service. But I repeated the service and performed the rites only as a matter of business;—I thought only of the food and the clothes that my sacred profession enabled me to gain. And because of this selfish impiety I was reborn, immediately after my death, into the state of a jikininki. Since then I have been obliged to feed upon the corpses of the people who die in this district: every one of them I must devour in the way that you saw last night... Now, reverend Sir, let me beseech you to perform a Segaki-service [2] for me: help me by your prayers, I entreat you, so that I may be soon able to escape from this horrible state of existence"...

No sooner had the hermit uttered this petition than he disappeared; and the hermitage also disappeared at the same instant. And Muso Kokushi found himself kneeling alone in the high grass, beside an ancient and moss-grown tomb of the form called go-rin-ishi, [3] which seemed to be the tomb of a priest.

(1) The southern part of present-day Gifu Prefecture.

[1] Literally, a man-eating goblin. The Japanese narrator gives also the Sanscrit term, "Rakshasa;" but this word is quite as vague as jikininki, since there are many kinds of Rakshasas. Apparently the word jikininki signifies here one of the Baramon-Rasetsu-Gaki,—forming the twenty-sixth class of pretas enumerated in the old Buddhist books.

[2] A Segaki-service is a special Buddhist service performed on behalf of beings supposed to have entered into the condition of gaki (pretas), or hungry spirits. For a brief account of such a service, see my Japanese Miscellany.

[3] Literally, "five-circle [or five-zone] stone." A funeral monument consisting of five parts superimposed,—each of a different form,—symbolizing the five mystic elements: Ether, Air, Fire, Water, Earth.