ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

良寛大愚 Ryōkan Taigu (1758–1831)

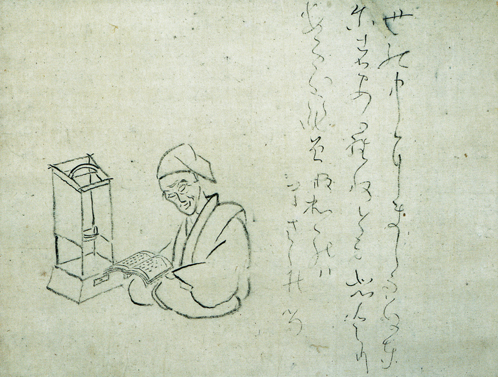

良寛筆「自画像・歌賛」

Self-portrait of Ryōkan with inscribed verse

“It is not that I do not wish to associate with men,

But living alone I have the better Way.”

世の中に | yo no naka ni | in the world

まじらぬとには | majiranu to ni ha | mixing-not that

あらねども | aranedomo | not

ひとり遊びぞ | hitori asobi zo | playing alone

我はまされる | ware ha masareru | by myself is better

Tartalom |

Contents |

Rjókan Taigu

Kovács András Ferenc

Összegyűjtött magyar versfordítások

Kiliti Joruto: Rjókan [Legendák Rjókan életéből] Rjókan: Versek és anekdoták

The Complete Haiku in 4 languages:

|

PDF: The Zen Poems of Ryokan. PDF: Great Fool: Zen Master Ryōkan: Poems, Letters, and Other Writings PDF: Sky Above, Great Wind: The Life and Poetry of Zen Master Ryokan

PDF: One Robe, One Bowl: The Zen Poetry of Ryōkan PDF: Dewdrops on a Lotus Leaf: Zen Poems of Ryōkan

PDF: The Kanshi Poems of Taigu Ryokan Poems to Saichi by Ryōkan PDF: Poems in Chinese by the Japanese Zen Monk Ryōkan PDF: Ryōkan, Zen Monk-Poet of Japan

PDF: The Geography of Freedom: Ryokan at Gogoan, Thoreau at Walden Pond PDF: Zen Master Tales PDF: Ryokan: Poems From a Man Who Preferred Solitude |

![]()

A Japanese monk of the Sôtô school of zen during the Edo period. After receiving a Confucian education (see Confucianism) in his youth, he turned aside from the path of governmental work laid out by his father and entered the Sôtô order at 18. This was a period in which, under the influence of Chinese Ts'ao-tung monks, the Sôtô school was undergoing a wave of reform, and many were advocating strict regimens of meditation and the study of Sôtô founder Dôgen's works. Ryôkan fell in with this reformist programme, and studied with several strict and uncompromising masters. In 1792, he received word that his father had travelled to Kyoto to present a work to the government denouncing political intrigue and corruption, and had then committed suicide, apparently to call attention to his protest. Ryôkan arranged the funeral and subsequent memorial services, and then set out on religious pilgrimage for several years. Only in 1804 did he settle down on Mt. Kugami, where he stayed for twelve years. He is remembered for the depth of his enlightenment that manifested in the spirit of acceptance and equality that he showed to all, from officials to prostitutes. He played with children, composed poetry in praise of nature, was renowned for his calligraphy, lived in extreme simplicity, and showed love for all living things to the extent of placing lice under his robes to keep them warm, allowing thieves to take freely from his possessions, and letting one leg protrude from his mosquito net at night to give the mosquitos food.

Buddhism Dictionary

Ryokan Interpreted by Shohaku Okumura, Independently published, 2021, p. 199.

The Zen Fool: Ryōkan, by Misao Kodama and Hikosaku Yanagashima. 2000

Ryokan: Selected Tanka and Haiku, translated from the Japanese by Sanford Goldstein, Shigeo Mizoguchi and Fujisato Kitajima, Kokodo, 2000, pp. 218.

Ryokan's Calligraphy, by Kiichi Kato; translated by Sanford Goldstein and Fujisato Kitajima, Kokodo, 1997

Three Zen Masters: Ikkyū, Hakuin, Ryōkan (Kodansha Biographies), by John Stevens. 1993

Between the Floating Mist: Poems of Ryokan, by Dennis Maloney & Hideo Shiro, Buffalo, 1992

Contents

Introduction 1

Waka: Poems in Japanese 17

Kanshi: Poems in Chinese 71

Admonitory Words 115

Statement on Begging for Food 117

PDF: Religion Solitude And Nature in The Poetry of Zen Monk Ryokan

by

Gregory Paul Yavorsky

University of British Columbia, 1980

PDF: Moon is Not the Moon: Non-Transcendence in the Poetry of Han-shan & Ryokan

by

Christopher Ryan Byme

McGill University, 2005

* * *

Yamamoto Ryōkan

(1758-1831), Haiku tr. by Michael Haldane

http://www.michaelhaldane.com/HaikuNonJapanese.htm

autumn wind -

a figure

standing alone

first winter-rain -

a nameless mountain

quaintly

in the begging-bowl

tomorrow’s rice -

evening breeze

*yūsuzumi: cooling oneself in the evening after work and the heat of the Japanese summer day.

the poignancy

of closing autumn, whom

to tell?

when everyone

wants to sleep -

reed-warblers

*gyōgyōshi’: ‘exaggerated’. It refers to the sound made by the yoshikiri (reed-warbler).

bring tidings

from Mt. Shumi,

eventide wild geese

*Mt. Shumi: at the centre of the Buddhist paradise. Ryōkan is requesting the migrating wild geese to return from the West with news of his father.

fallen

still

garden plants

* * *

Ryokan (1758-1831)

Ryokan was born in 1758, the first son in a noble family in Izumozaki in the

Echigo District. He entered the priesthood at the age of 18 and was given the

Buddhist name "Ryokan" when he was 22 years old. He kept searching

for the ultimate truths through his life. Leaning the Chinese classics and

poetry at Entsu Temple of the Soto Sect in Tamashima in the Bichu District, he

practiced hard asceticism under Priest Kokusen for 20 years. After this, he

traveled all over the country on foot and returned to his home village just

before the age of 40. He lived at the Gogoan hut in Kokujyo Temple on Mt.

Kugami, and then moved down to a thatched hut in Otoko Shrine at the foot of

the Mountain. It is said that he enjoyed writing traditional Japanese poetry,

Chinese poetry and calligraphy all through his simple, carefree and unselfish

life. He was also called "Temari-Shonin (The Priest who Plays with a

Temari ball)" and was much loved by children, since he often played with a

Temari ball (Japanese cotton-wound ball), Ohajiki (small glass counters for

playing games) together with children in the mountain village. Much of his

poetry and letters which still remain, all of which are full of his sympathy

and affection for children, describe his joyful times with children and also

reveal his high personal qualities as a man who devoted his life to meditation.

Ryokan was a Zen priest, but he never established his own temple, and lived by

alms. Instead of preaching, he enjoyed companionship and conversation with many

ordinary people. In 1831, he ended his 74-year life as an honest priest

respected and loved by all he knew.

* * *

Ryokan

is a man who has many stories told about him. He is famous for spending his days

playing “hide and seek” and traditional Japanese ball games

(“temari”) with children.

One day a bamboo shoot sprouted from below the floor of his hermitage and

grew up to the ceiling. As Ryokan used a

candle to burn a hole in the ceiling for the bamboo shoot to grow out, he

accidentally burned the hut to the ground.

Ryokan also composed poems and songs, and was skilled in calligraphy.

People tried to get him to write poems when they happened to find him, but

Ryokan would never write anything for them. This is why the writings that still

exist are so popular and expensive. I have heard that almost all of the

writings with Ryokan`s signature which appear on the market are actually

counterfeit.

This

story about Ryokan is also well known. In Ryokan's last years, a beautiful

young nun visited his hermitage frequently and they composed and exchanged love

poems with each other. When an

earthquake occurred at Echigo-Sanjo, he sent a strange letter that said

“It is good to suffer a misfortune when suffering a misfortune.”

Another famous story has to do with Ryokan as a child. He was scolded by his father, who told him

“If you make a funny face you will turn into a flounder.” Ryokan was very worried about being able to

make it to the sea in time when he turned into the fish, so he waited on a rock

on the seashore for a long time.

Ryokan

(1758-1831) lived in the same age as the haiku poet Issa Kobayashi (born in

1763), through the reigns of Bunka to Bunsei, at the end of the

The day after my life at Eihei temple ended I left for

『Kanjinjikibun』is a sentence where Rokan's beliefs are pointed out

clearly. It means “A priest must

fulfill their duty by religious austerities.”

“Religious austerities” means that a priest chants a sutra called

“kadozuke” from house to house and does an act of charity. In turn, the house contributes a small amount

of something in the house, such as rice or grain. Both parties treasure the spirit of mutual

aid that results from giving to each other. This has been a traditional form of Buddhism since Buddhism was created.

It is an important precept of Buddhism that religious austerities must be done

indiscriminately, to both rich and poor houses. 「乞食 Kotsujiki」in Buddhism and 「乞食 kojiki」use the same Chinese characters, but the meanings

are as different as Heaven and Earth. We call this lifestyle

“Jomyoshoku”(the

innocent food of a priest).

Ryokan

manifested the meaning of Buddhist precepts in his life, and not only in his

words. Because of this, everyone who

came into contact with him was educated in Buddhist ways, without even speaking

to him. A curious story about Ryokan

says that even though he did not preach or recommend good conduct when he

stayed as a guest in someone's house, the atmosphere naturally became peaceful

and the family happy. The house was also

enveloped in a sweet smell for a few days after Ryokan left.

http://onebowl.shousouji.com/english/ryokan2.html

* * *

The Way of the Holy Fool

What a monk can teach us about living, laughing, and child's play

by Larry Smith

Parabola, January/February 2002

At the crossroads this year, after begging all day

I lingered at the village temple.

Children gather round me and whisper,

'The crazy monk has come back to play.'—Taigu Ryokan

Taigu Ryokan lives on as one of Japan’s best-loved poets, the wise fool who wrote of his humble life with directness. Born in 1758, he is part of a tradition of radical Zen poets, or 'great fools,' that includes China’s Han-shan and P’ang Yun (Layman P’ang) and Japan’s Ikkyu Sojun and Hakuin Ekaku.

The eldest of seven children, Ryokan grew up near Mount Kugami in the town of Izumozaki, a community for artists and writers. His father, a scholar of Japanese literature and a renowned haiku poet, was the town’s ineffectual mayor. His mother was a quiet woman who eventually had to deal with her husband’s abandoning his position and his family and then drowning himself in the river Katsura.

In his youth, Ryokan trained under a Confucian scholar and began to study Chinese literature in the original. At 16, he had already flirted with a life of gambling and women, then surprised everyone by taking up the study of Soto Zen at the nearby Koshoji temple. (Soto and Rinzai comprise the two main schools of Japanese Zen Buddhism.) He shaved his head and took his robes and vows. At 21, he moved to the Entsuji temple in Bitchu, but eventually became disillusioned and outraged at the corrupt practices of vain and greedy temple priests and left to make his mountain hermitage.

Ryokan had no disciples and ran no temple; in the eyes of the world he was a penniless monk who spent his life in the snow country of Mount Kugami. He admired most of the teachings of Dogen, the 13th century monk who first brought Soto Zen to Japan. He was also drawn to the unconventional life and poetry of the Zen mountain poet Han-shan, who lived in China sometime during the T’ang Dynasty (618 to 907). He repeatedly refused to be honored or confined as a 'professional,' either as a Buddhist priest or as a poet. He wrote:

Who says my poems are poems?

These poems are not poems.

When you can understand this,

then we can begin to speak of poetry.

Ryokan never published a collection of verse while he was alive. His practice consisted of sitting in zazen meditation, walking in the woods, playing with children, making his daily begging rounds, reading and writing poetry, doing calligraphy, and on occasion drinking wine with friends.

Ryokan later dubbed himself Taigu, or 'Great Fool,' but this title had a special meaning. A Zen master who taught the young Ryokan described him this way: 'Ryokan looks like a fool, but his way of life is an entirely emancipated one. He lives on playing, so to say, with his destiny, liberating himself from every kind of fetter.' He went on to describe his disciple’s simple life: 'In the morning he wanders out of his hut and goes God knows where and in the evening loiters around somewhere. For fame he cares nothing. Men’s cunning ways he puts out of the question.' His freewheeling spirit had much in common with the American writer Henry David Thoreau’s. Ryokan’s life was an affirmation of alternate values and a rebuke to the hypocrisy and rigid values found in Japanese Zen monasteries and in society at large.

His 'foolishness' belongs in a Taoist-Buddhist context as an inversion of social norms. Ryokan declares the Way of the Fool in his poem 'No Mind':

With no mind, flowers lure the butterfly;

With no mind, the butterfly visits the blossoms.

Yet when flowers bloom, the butterfly comes;

When the butterfly comes, the flowers bloom.

'No mind,' or mushin, means not to cling or to strive, and when it is joined with mujo, or acceptance of life’s impermanence, we have the greatness of the fool.

To achieve this original or beginner’s mind, Ryokan sought the company of children, kept his humble begging rounds, accepted his everyday life, and recorded it all in his authentic poems. Dropping whatever he was doing, he would turn to join the children’s games of tag and blindman’s buff, hide-and-seek, and 'grass fights.' He was once caught playing marbles with a geisha and is said never to have refused a game of Go. He relished playing dead for the children, who would bury him in leaves, and he would spend the day picking flowers with them, forgetting his begging rounds.

The stories of Ryokan’s playfulness are legendary. Here’s one,

preserved after his death in

'Ryokan was playing hide-and-seek, and when it came his turn to hide, he looked around for a spot where the children wouldn’t find him. Noticing a tall haystack, he crawled inside, concealing himself completely in the hay. No matter how hard they searched, the children couldn’t find him. Soon they grew tired of playing, the sun began to set, and when they saw the smoke rising from the dinner fires, they deserted Ryokan and returned to their homes. Unaware of this, Ryokan imagined the children were still searching for him. Thinking, ‘Here they come to look for me! Now they’re going to find me,’ he waited and waited. He waited all night and was still waiting when dawn arrived. In farmhouses, in the morning the kitchen hearth is lit by burning bundles of hay, and when the farmer’s daughter came to fetch some of these, she was startled to find Ryokan hiding in the haystack. ‘Ryokan! What in the world are you doing here?’ she cried. ‘Shh!’ Ryokan warned her, ‘The children will find me.’ '

His tendency to misplace things—his walking stick, his begging bowl, books, even his underwear—was well known. Among the stories of his chronic forgetfulness is one of a visit by the famous scholar Kameda Bosai. When Bosai found Ryokan sitting zazen on the porch of his hut, he waited—several hours—for the monk to finish, and then Bosai and Ryokan happily talked poetry, philosophy, and writing until evening, when Ryokan rose to fetch them some sake from town.

Again Bosai waited several hours, then grew concerned and began to walk toward the village. When he found his host a hundred yards away, sitting under a pine tree, he exclaimed, 'Ryokan! Where have you been? I’ve been waiting for hours and was afraid something had happened to you.' Ryokan looked up. 'Bosai, you have just come in time. Look, isn’t the moon splendid tonight?' When Bosai asked about the sake, Ryokan replied, 'Oh, yes, the sake. I forgot all about it,' and headed off to town. To be distracted by life’s moments is indeed a Zen virtue, though it is often a trial for friends.

Ryokan often wrote in the Kanshi form—poems composed in classical Chinese. Taken together, his Kanshi poems are best seen as an undated journal, a record of a humble life spent living in the moment without thoughts of fame and power. In recording his experience of play, begging, observing people and nature, and accepting life’s bounty, Ryokan becomes the self-deprecating great fool in order to mentor us in an authentic life of simplicity, trust, humility, and finding the true way in everyday life

RYŌKAN'S LIFE AND CHARACTER

by John Stevens

What will remain as my legacy?

Flowers in the spring,

The hototogisu in summer,

And the crimson leaves of autumn.

Ryōkan was born some time around 1758 (the exact date of his birth is unknown) in the village of Izumozaki in Echigo province on the west coast of Japan. This area, now known as Niigata Prefecture, is rather remote even today, far removed from the commercial and cultural centers of Tokyo, Osaka, and Kyoto. It is “snow country” and bitterly cold in winter. Ryōkan's family was well established in the area, and his father, Tachibana Inan, 3 was the village headman, the local Shinto priest, and a prosperous merchant.

Ryōkan's father was a complex person with a sensitive and passionate nature. He was a haiku poet of some note, with a certain following, but also an ardent imperial supporter and opponent of the bakufu , the military government in Edo. The reason for his unhappiness with the government is not clear (perhaps in his duties as village headman he had some clashes with bakufu officials), but when his son Yoshiyuki succeeded him (Ryōkan was the oldest son but turned his inheritance over to his brothers and sisters when he became a monk), Inan left home and spent many years wandering around Japan before settling in Kyoto. He again declared his support of the emperor and, evidently feeling intolerably oppressed by the bakufu, committed suicide in 1795 by throwing himself into the Katsura River in Kyoto as a protest; he was sixty years of age. Little is known of Ryōkan's mother, but it is clear from his poems concerning her that she was a very gentle and loving person. She died in 1783, and Inan left the village forever three years later.

Ryōkan's childhood name was Eizō. He was a quiet and studious boy who often spent long hours reading the Analects of Confucius. His family was well off, and the atmosphere in his home was a literary and religious one—two brothers and one sister also entered the Buddhist priesthood. His youth was calm and sheltered, and passed uneventfully until his eighteenth year.

Ryōkan was to succeed his father as village headman when he turned eighteen. While training for the post, he found it especially trying. He was honest and conciliatory by nature and hated contention or discord of any kind, but was forced to deal with many conflicts and troublesome cases. In addition to those burdensome duties, he seems to have been undergoing some inner, spiritual crisis. Previously he had been a fun-loving young man, generous with his money and the center of attention at the local geisha parties, but he started to become withdrawn and silent in the midst of festivities.

Clearly something was troubling him, and he decided to become a Buddhist monk. In 1777 he shaved his head and entered Kōshō-ji, the local Zen temple, where he took the name Ryōkan ( ryō means good; kan signifies generosity and largeheartedness). After he had trained there for about four years, a famous Zen priest known as Kokusen came to deliver a lecture. Kokusen was the abbot of Entsū-ji temple at Tamashima in Bitchū province (present-day Okayama Prefecture). Ryōkan was greatly impressed with Kokusen and decided to become his disciple and return with him to Entsū-ji. Ryōkan was then twenty-two.

He trained under Kokusen at Entsū-ji for almost twelve years. During this time he continued his studies of waka ; Chinese poetry; linked verse, or renga ; and calligraphy, becoming skilled in all of them. He was appointed Kokusen's chief disciple and was given a document certifying his enlightenment in 1790. The following year Kokusen died and Ryōkan left Entsū-ji to begin a series of pilgrimages that would last almost five years. After learning of his father's suicide in 1795, Ryōkan went to Kyoto and held a memorial service for him. He then decided to return to his native village.

After searching for a time, he found an empty hermitage halfway up Mount Kugami, about six miles from his ancestral home. He named it Gogō-an. Gogō is half a shō , the amount of rice necessary to sustain a man for one day; an is hermitage. It is this period of Ryōkan's life—extending from his establishment of Gogō-an at the age of forty to his death thirty-four years later—that is the most remarkable.

While his hermitage was deep in the mountains, he often visited the neighboring villages to play with the children, drink sakè with the farmers, or visit his friends. He slept when he wanted to, drank freely, and frequently joined the dancing parties held in summer. He acquired his simple needs by mendicancy, and if he had anything extra he gave it away. He never preached or exhorted, but his life radiated purity and joy; he was a living sermon.

He respected everyone and bowed whenever he met anyone who labored, especially farmers. His love for children and flowers is proverbial among the Japanese. Often he spent the entire day playing with the children or picking flowers, completely forgetting his begging for that day. If anyone asked him to play the board game go or recite some of his poems, he would always comply. He was continually smiling, and everyone he visited felt as if “spring had come on a dark winter's day.”

When he was sixty he moved to a small hermitage next to Otogo Shrine, and at sixty-nine, due to ill health, he went to live with his disciple Kimura Motoemon. It was in the Kimura residence in Shimazaki that he first met his famous disciple, the nun Teishin.

Teishin was forty years Ryōkan's junior. She had been married to a physician when seventeen or eighteen, but he died several years later and she became a nun at the age of twenty-three. She was twenty-nine when she met Ryōkan, and they seem to have fallen in love almost immediately. They delighted in each other's company, composing poems and talking about literature and religion for hours. She was with him when he died on January 6, 1831. One of his last verses reads:

Life is like a dewdrop,

Empty and fleeting;

My years are gone

And now, quivering and frail,

I must fade away.

Four years later, in 1835, Teishin published a collection of Ryōkan's poems entitled Hasu no tsuyu (Dewdrops on a lotus leaf). Teishin devoted herself to Ryōkan's memory until her death in 1872.

There are many stories and anecdotes concerning Ryōkan's eccentric behavior. Following are a few of the most famous.

Kameda Hōsai, a famous scholar who lived in Edo (now Tokyo), once went to visit Ryōkan. He found the way to Ryōkan's hermitage, but when he reached it Ryōkan was sitting in zazen on the veranda. Hōsai, not wishing to disturb him, waited until he finished almost three hours later. Ryōkan was very glad to meet Hōsai, and they talked of poetry, philosophy, and literature for the rest of the day. Evening approached, and Ryōkan wanted to get some sakè so they could continue talking. He asked Hōsai to wait a few minutes and hurried out.

Hōsai waited and waited, but Ryōkan did not return. When he could stand it no longer, he went out to try to find Ryōkan. To his astonishment, he saw Ryōkan about a hundred yards from the hermitage, sitting under a pine, gazing dreamily at the full moon. “Ryōkan! Where have you been? I've been waiting for you for more than three hours! I thought something terrible had happened to you!” Hōsai shouted.

“Hōsai-san! You have come just in time. Isn't the moon splendid?”

“Yes, yes, it's wonderful. But where is the sakè?”

“The sakè? Oh, yes, the sakè. I'm so sorry, please excuse me. I forgot all about it. Forgive me. I'll go get some right away!” Ryōkan sprang up and bounded down the path, leaving Hōsai standing in amazement.

One spring afternoon, Ryōkan noticed three bamboo shoots growing under his veranda. Bamboo grows rapidly, and soon the shoots were pressing against the bottom of the veranda. Ryōkan was quite anxious, for he did not like anything to suffer, even plants. He cut three holes in the floor and then told the bamboo shoots not to worry; he would cut a hole in the roof if necessary. He was happy once again.

Ryōkan never preached to or reprimanded anyone. Once his brother asked Ryōkan to visit his house and speak to his delinquent son. Ryōkan came but did not say a word of admonition to the boy. He stayed overnight and prepared to leave the next morning. As the wayward nephew was lacing Ryōkan's straw sandals, he felt a warm drop of water. Glancing up, he saw Ryōkan looking down at him, his eyes full of tears. Ryōkan then returned home, and the nephew changed for the better.

Ryōkan loved to play hide-and-seek with the children. One day he ran to hide in the outhouse. The children knew where he was but decided to play a joke and run away without telling him. The next morning someone came into the outhouse and saw Ryōkan crouching in the corner. “What are you doing here, Ryōkan?” she said. “Shh, be quiet, please,” he whispered, “or else the children will find me.”

Once when he was walking near the village he heard a small voice cry, “Help! Help me, please!” A little boy was stuck in the topmost branches of a persimmon tree. Ryōkan helped the lad down and said he would pick some fruit for him. Ryōkan climbed the tree and picked one of the persimmons. He decided to taste it first, since unripe persimmons can be very astringent and he did not want to give one to the boy. No, it was very sweet. He picked another and it too was sweet. One after another, he stuffed the persimmons into his mouth, exclaiming, “Oh, how sweet!” He had completely forgotten about the little boy waiting hungrily below until the boy yelled, “Ryōkan! Please give me some persimmons!” Ryōkan came to his senses, laughed, and passed the delicious fruit to his small friend.

Someone told Ryōkan that if you find money on the road you will be very happy. One day, after he had received some coins during a begging trip, he decided to try it. He scattered the coins along the road and then picked them up. He did this several times but did not feel particularly happy, and he wondered what his friend had meant. He tried it a few more times and in the process lost all the money in the grass. After searching for a long time he finally found all the money he had lost. He was very happy. “Now I understand,” he thought; “to find money on the road is indeed a joy.”

Ryōkan's tomb is located in Shimazaki, and his hermitage still stands on Mount Kugami. There is a small temple on the cliff overlooking the Japan Sea where Ryōkan's boyhood home once stood, and an art museum and memorial hall dedicated to him have been erected near Izumozaki. Many people come each year to visit these sites associated with Ryōkan, one of Japan's most beloved poets.

RYŌKAN AND ZEN

Ryōkan was a monk of the Sōtō Zen sect, which was brought to Japan from China by Dōgen (1200–1253), the founder of Eihei-ji monastery in Fukui Prefecture, the largest and most famous monastery in Japan. Dōgen's teaching emphasized two main points: (1) shikantaza , themeless sitting in zazen—that is, abandoning all thoughts of good or bad, enlightenment or illusion, and just sitting; and (2) shushō ichigyō , “practice and enlightenment are one.” There is no sudden enlightenment, and enlightenment cannot be separated from one's practice. For these reasons, Sōtō Zen is usually contrasted with Rinzai Zen, with its use of kōans during zazen and its striving for kenshō , an instantaneous, profound insight into reality. Generally speaking, Rinzai Zen tends to be somewhat violent and severe, while Sōtō Zen is usually more restrained and quiet.

As a Sōtō Zen monk, Ryōkan first followed the traditional pattern of communal life in the monastery, then a period as an unsui , a pilgrim monk drifting from place to place like “clouds and water” ( unsui ) visiting other masters. Ryōkan could have become the head of a temple or taken some other position in a large monastery, but he was not interested. His severe training had made him not austere or remote but more open and kind. Therefore, he “returned to the marketplace with bliss-bestowing hands,” the state depicted in the last of the well-known Zen series of the ten oxherding pictures, and the culmination of all Buddhist practice.

Ryōkan's life at Gogō-an represents that highest stage of Zen spirituality very well. He mingled with all types of people, living Zen without preaching about it. He was detached from his detachment, free of any sort of physical or spiritual materialism; in love with nature, he was sensitive to all the myriad forms of human feeling.

With no-mind, blossoms invite the butterfly;

With no-mind, the butterfly visits the blossoms.

When the flower blooms, the butterfly comes;

When the butterfly comes, the flower blooms.

I do not “know” others,

Others do not “know” me.

Not-knowing each other we naturally follow the Way.

In this famous poem “no-mind” is mushin , the mind that abides nowhere, the mind free of contrivance. No-mind has no obstructions or inhibitions and therefore is synonymous with Zen. “Know” here means to categorize or analyze oneself and others. Throughout Ryōkan's poems we find this theme: “Don't cling! Don't strive! Abandon yourself! Look beneath your feet!”

The other Buddhist element strongly felt in Ryōkan's poems is mujō, impermanence. This world is a dream, passing away like dew.

Long ago, I often drank sakè at this house;

now only the earth

Covered with plum blossoms.

Ryōkan's Zen is replete with mushin , the mind without calculation or pretense, and mujō , the sense of the impermanence of all things.

RYŌKAN'S POEMS

Ryōkan has said:

“Who says my poems are poems?

My poems are not poems.

After you know my poems are not poems,

Then we can begin to discuss poetry!”

Ryōkan wrote in many different styles of poetry—classical Chinese, haiku, waka, folk songs, and Man'yō -style poems. The Chinese poems, or kanshi , generally contain five Chinese characters per line, although some lines have seven characters, with a minimum of four lines. Most of the poems are untitled. There are about four hundred of these Chinese poems. In both his life style and his Chinese poems Ryōkan is often compared to the famous eighth-century Chinese poet Han-shan (Kanzan), the eccentric hermit of Cold Mountain. Ryōkan often read Han-shan's poems, and the work of both men has a fresh, “country” feeling with little ornamentation.

Ryōkan frequently ignored rules of literary composition in writing his Japanese-style poems; consequently, many of his haiku (three lines of five, seven, and five syllables, respectively) and waka (five lines of five, seven, five, seven, and seven syllables, respectively) do not conform to the classical pattern. Actually, the number of haiku is quite small, the majority of his Japanese poems being free-style waka. He also composed a few folk songs and a number of Man'yō -style poems (the style used in the Man'yōshū , an eighth-century collection of ancient Japanese poetry) with many syllables. He wrote about one thousand Japanese-style poems altogether.

Most of the poems are concerned with Ryōkan's daily life—begging for his food, playing with the children, visiting the local farmers, walking through the fields and hills. He also wrote love poems to Teishin and poems on Buddhist themes.

Far from being highly crafted and refined, Ryōkan's poems are spontaneous and direct; simple and pure on the surface, they contain a profound inner feeling of mushin and mujō . His poems are very beautiful when chanted and are popular among devotees of shigin , classical poetry recitation. Ryōkan is also known as one of Japan's great calligraphers, and originals of his poems are highly valued. We see, then, that Ryōkan is esteemed both for his unconventional life and for the lyrics, content, and calligraphic form of his poetry.

Self-portrait by Ryōkan, 24 x 26 cm

あ と 世

そ に の

び は 中

ハ あ に

わ ら ま

れ ね じ

は ど ら

良 ま も ぬ

寛 さ ひ

書 れ と

る り

"It is not that

I avoid mixing

With this world;

Better for me is enjoying

Life on my own.

Brushed by Ryokan"

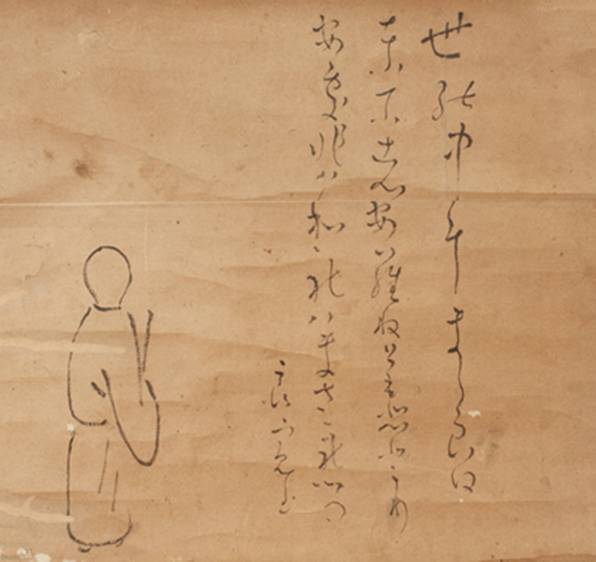

自画像

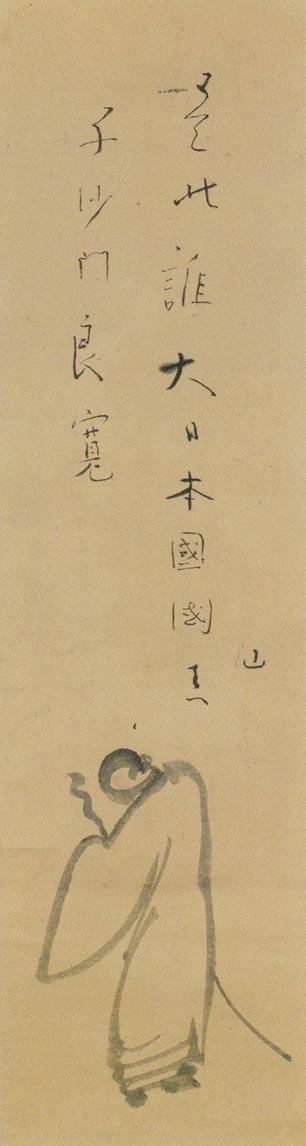

是此誰 是れは此れ誰ぞ 大日本国国仙真子(こくせんししこ) 沙門良寛

Autoportrait de Ryōkan

"Qui-suis-je? Je suis le vrai fils (le disciple) de Koku(sen) du grand pays Japon". Śramaṇa Ryōkan

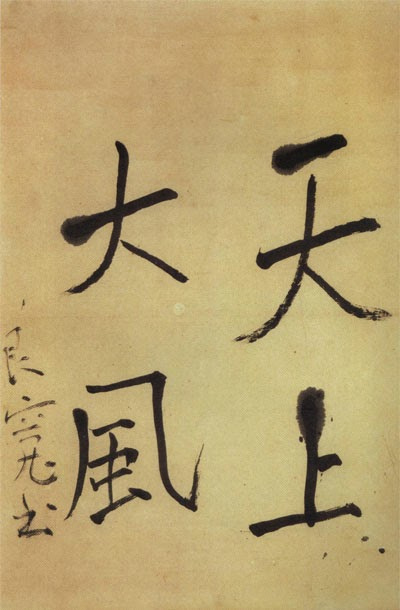

Calligraphy

【天上大風】 SKY ABOVE, GREAT WIND by Ryokan

Ryokan was happy to do calligraphy for children. It is said in Anecdotes:

When Ryokan was begging in the highway station town Tsubame, a child with a sheet of paper came to him and said, “Rev. Ryokan, please write something on this paper.” Ryokan asked, “What are you going to use it for?” “I am going to make a kite and fly it. So, please write some words to call the wind.”

Right away, Ryokan wrote four big characters, “Sky above, great wind,” and gave the calligraphy to the child.

He may have given similar pieces to other children. At least one piece has remained, becoming one of his most popular works (above). These four ideographs are written in Chinese-origin script commonly used in East Asia, known as kanji in Japanese. They are usually read from the right column, top down, to the center column, tian shan da feng in Chinese, which reads ten jo dai fu in Japanese. The left column says, “Ryokan sho” (Written by Ryokan). This calligraphy was done in a formal style.

There is no lack of technical imperfection in this piece. Ryokan started the first three characters with too much ink, causing them to bleed excessively on the rice paper at the beginning of the strokes. On the other hand, he was losing ink and strength of lines at the bottom of the two downward-sweeping strokes of the first character, sky (heaven). His hand wiggled on the vertical stroke of the second character, above , as well as on the top-to-right-hand stroke of the last character, wind. Sky is too large, and above is too small. Wind is placed overly to the left, which forced him to squeeze his signature.

In general, technically perfect and elegantly rendered pieces of calligraphy are appreciated. Most calligraphers strive to meet such standards, and in many cases their desire for excellence is exposed through the brush lines. However, calligraphers and art lovers, including me, look at this piece in awe. We immediately notice that the artist was radically unpretentious and unassuming, showing no desire whatsoever to make the brushwork “look good.” As you will see in other samples, Ryokan was a skilled calligrapher. In this piece, on the other hand, he went far beyond skills, revealing himself completely off guard. We see vast freedom in his childlike brushstrokes, which demonstrate that Ryokan was a child when he was with children.

Sky above, great wind: the life and poetry of Zen Master Ryokan

© 2012 by Kazuaki Tanahashi

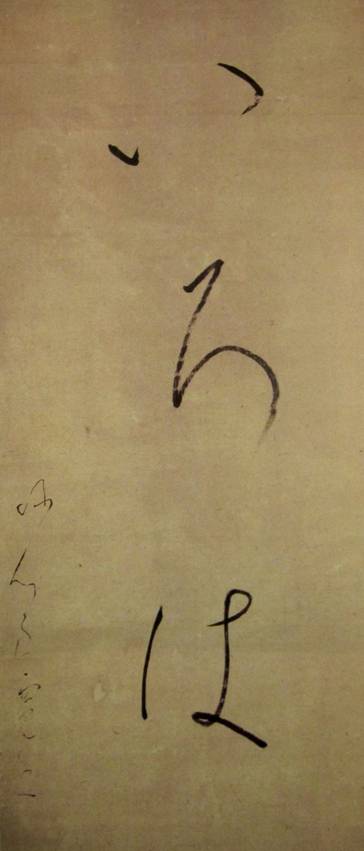

【いろは】 I-RO-HA by Ryokan

【一二三】 ONE, TWO, THREE by Ryokan

A peasant farmer once said to Ryokan, “Your writings are difficult to read. Can you write something even I can read?” Ryokan wrote “One, two, three,” and said, “I hope you can read this”

Generally, one is represented by a single horizontal line, while two and three are depicted with two and three horizontal lines. Indeed, there are no easier symbols than these in East Asian ideography. The villager who was given this calligraphy might have thought this was Ryokan's nonsense or joke. But in the Zen tradition, numbers sometimes indicate reality itself: words beyond words.

When the ideographic writing system was created in China about four thousand years ago, these numbers were drawn on soil or carved on wood or animal bones with straight geometric lines. After the brush was invented about two thousand years later, calligraphers developed the aesthetics of asymmetry within each stroke and among elements of each ideograph. This piece by Ryokan, written in a semicursive script, follows this tradition.

The first horizontal line goes up, which is common in Chinese-style calligraphy, but with atypical steepness. Following the initial press down, the brush was gradually pulled up, making its trace finer. It arched gracefully, then slightly pushed down to create a consistent width on its latter half. At the end of the line, the brush was lightly pressed down and swept off toward the next symbol.

In two, the line above is typically shorter than the line below. But in this case, the line above is excessively short—almost a dot—subtly curving up and sweeping off again. The second stroke starts pointed, forming a circular line followed by a most subtle curving-down line.

The first two strokes of three are two diagonal lines of different angles connected with a ligature. Preceded by an invisible ligature, the last line of this character is straight. On the final column he wrote: “Shaku Ryokan sho” (Written by monk Ryokan).

There is ample space between lines and characters. Ryokan created a style of calligraphy where even extra thin lines with few strokes can hold a large amount of space.

© 2012 by Kazuaki Tanahashi

【心月輪】 MIND, MOON, CIRCLE by Ryōkan,

carved on the cedar lid of a rice pot.

Courtesy of the Kera family, Niigata Prefecture.

Ryōkan's Dharma Lineage

永平道元 Eihei Dōgen (1200-1253)

孤雲懐奘 Koun Ejō (1198-1280)

徹通義介 Tettsū Gikai (1219-1309)

螢山紹瑾 Keizan Jōkin (1268-1325)

明峰素哲 Meihō Sotetsu (1277-1350)

珠巌道珍 Shugan Dōchin (?-1387)

徹山旨廓 Tessan Shikaku (?-1376)

桂巌英昌 Keigan Eishō (1321-1412)

籌山了運 Chuzan Ryōun (1350-1432)

義山等仁 Gisan Tōnin (1386-1462)

紹嶽堅隆 Shōgaku Kenryū (?-1485)

幾年豊隆 Kinen Hōryū (?-1506)

提室智闡 Daishitsu Chisen (1461-1536)

虎渓正淳 Kokei Shōjun (?-1555)

雪窓祐輔 Sessō Yūho (?-1576)

海天玄聚 Kaiten Genju (?-?)

州山春昌 Shūzan Shunshō (1590-1647)

超山誾越 Chōzan Gin'etsu (1581-1672)

福州光智 Fukushū Kōchi (?-?)

明堂雄暾 Meidō Yūton (?-?)

白峰玄滴 Hakuhō Genteki (1594-1670)

月舟宗胡 Gesshū Sōko (1618-1696)

徳翁良高 Tokuō Ryōkō (1649-1709)

高外全國 Kōgai Zenkoku (1671-1743)

大忍国仙 Dainin Kokusen (1723–1791)

良寛大愚 Ryōkan Taigu (1758–1831) [born 山本栄蔵 Yamamoto Eizō]

三輪左一 Miwa Saichi (?-1807) [disciple of Ryōkan. His premature death was deeply mourned by Ryōkan.](Miwa Saichi was a koji or layman who studied Zen with Ryōkan

until his death in the fifth month of 1807. To Ryokan, who apparently

had few other Zen students, his death was a great blow, and

he referred to it often in his poems.)Poems to Saichi by Ryōkan

Translated by Burton Watson:

When News of Saichi's Death Arrived

[283]

Ah-my koji!

studied Zen with me twenty years.

You were the one who understood—

things I couldn't pass on to others.I Dreamt of Saichi and Woke with a Feeling of Uneasiness

[292]

After twenty some years, one meeting with you,

gentle breeze, hazy moon, east of the country bridge:

we walked on and on, hand in hand, talking,

till we reached the Hachiman Shrine in your village of Yoita.

Translated by Nobuyuki Yuasa:

141.

Saichi, my friend, is truly a man worthy of my best praise.

A great pity it is, few alive know the reach of his wisdom.

Once he chanced to write for me an ode in honour of Buddha.

Never can I see it without soaking my sleeves in hot tears.142.

To SaichiTo visit my holy teacher on his deathbed, I closed my gate,

And walked many a mile, with just a flask in my aging hand.

I saw a waterfowl flying far beyond the stretch of the sea,

And around me, hills aglow in their last colours of autumn.143.

Shortly after the death of SaichiOn this dark, drizzling day, in the dreadful month of June,

Where have you gone, I wonder, leaving me lingering behind?

Hoping to cure my loneliness, I have come to your old home,

But in the greenest hills cuckoos alone raise a loud noise.144.

On dreaming of SaichiTwenty years after your death, you and I have met once more,

Beside a rustic bridge, in a breeze, beneath the misty moon.

Hand in hand, we walked along, talking loudly to each other,

Till we both came, unawares, to the village shrine at Yoita.

Translated by John Stevens

Dreaming of Saichi, My Long-Deceased Disciple

I met you again after more than twenty years,

On a rickety bridge, beneath the hazy moon, in the spring wind.

We walked on and on, arm in arm, talking and talking,

Until suddenly we were in front of Hachiman Shrine!

ADMONITORY WORDS

by Ryōkan Taigu

Translated by Burton Watson

in: Ryokan: Zen Monk - Poet of Japan, Columbia University Press, 1992, 115ff

EXCERPTS FROM Ryōkan's list of ninety Kaigo or "Admonitory

Words," which seems to have been addressed mainly to him-

self. Several versions of the list exist; I follow that recorded in

the Hachisu no tsuyu, Ōshima Kasoku, Ryōkan zenshū

(Tokyo: Shingensha, 1958), pp. 526-28. The original is in

Japanese.

Beware of:

talking a great deal

talking too fast

volunteering information when not asked

giving gratuitous advice

talking up your own accomplishments

breaking in before others have finished speaking

trying to explain to others something you don't understand yourself

starting on a new subject before you've finished with the last one

insisting on getting in the last word

making glib promises

repeating yourself, as old people will do

talking with your hands

speaking in an affectedly offhand manner

reporting in detail on affairs that have nothing to do with anything

reporting on every single thing you see or hear

making a point of using Chinese words and expressions

learning Kyoto speech and using it as though you'd known it all your life

speaking Edo dialect like a country hick

talk that smacks of the pedant

talk that smacks of the aesthete

talk that smacks of satori

talk that smacks of the tea master

According to the preface to the Sōdōshū, Ryōkan declared there were three things he disliked:

poet's poetry

calligrapher's calligraphy

chef's cooking

STATEMENT ON BEGGING FOR FOOD

by Ryōkan Taigu

Translated by Burton Watson

in: Ryokan: Zen Monk - Poet of Japan, Columbia University Press, 1992, 117ff

THE RECEIVING OF GIFTS of food is the lifeblood of the Buddhist

Order. For this reason we have our rituals for unwrapping

gruel bowls and our rules for begging food. Vimalakirti ob-

tained "pure rice" from the Buddha of Fragrance Accumulated

and offered it to the multitude that had gathered from all

around; Chunda sought permission to present Shakyamuni

with a final meal and received Shakyarnuni's sanction.1

Long ago, when Prince Siddhārtha [Shākyamuni] was

pursuing religious practices in the snowy mountains, he at

first served under the ascetic Alāra Kālāma and others,

day after day eating no more than one hemp seed and one

grain of wheat, observing the most difficult and painful aus-

terities, but they were of no help to him in finding the Way.

Then, realizing that they were not the correct method, he

abandoned them and attained Enlightenment.

The observances of one Buddha shall be the observances for

a thousand Buddhas. Thus we should understand that the

Buddhas of the Three Worlds accepted gifts of food and at-

tained Enlightenment, and that the patriarchs and teachers

down through the ages accepted food and transmitted the

lamp of the Law.

Therefore it is said, "It is permissible to receive food that is

properly offered, but it is not permissible to receive food that

is impure." And again, "To eat large quantities of food will

cause one to be drowsy and to sleep a great deal and will give

rise to indolence and sloth; but to eat too little will leave one

with no strength to practice the Way."

The Sutra of the Buddha's Dying Instructions says.2 "You

monks, you should look upon the receiving of food and drink

as you would upon the taking of medicine, not increasing or

decreasing the quantity because some of it tastes good to you

and some tastes bad." And again, "Eat at fixed times and see

that you live in cleanliness and purity. Work to free yourselves

from delusion, and do not let the desire for much food destroy

the heart of goodness within you. Be with yourselves like a

wise man who gauges the amount of labor his ox can bear and

never exhausts its strength by driving it beyond the limit."

The Vimalakirti Sutra says, "Once Kāshyapa, moved by

pity and compassion, purposely went to a poor village to beg

for food.3 But Vimalakirti berated him, saying, 'Begging for

food must be done in an equal-minded manner! Because we

are equal-minded in matters of food, so we can be equal-

minded in matters of the Dharma.' "4

The Rules for Zazen says, "Not too cold in winter, not too

hot in summer; if the room is too bright, lower the blinds; if it

is too dark, slide open the window panels. Be moderate in

food and drink and go to bed at a fixed hour."5

The "Formula on the Five Remernbrances" says,6 "First, I

consider the effort that went into producing it. Second, I con-

sider how it came into my hands. Third, I consider whether I

have been diligent or neglectful in my own practice of virtue,

and accept it accordingly. Fourth, I accept this food so that I

may heal the decay of the body. Fifth, I accept it so that I may

attain the Way."

All these writings attest to the importance of accepting gifts

of food. If one accepts no food, then the body will not function

smoothly. When the body does not function smoothly, the

mind will not function smoothly; and when the mind does not

function smoothly, it becomes difficult to practice the Way. Is

this not why the Buddha is called a Jōgojōbu or one who

"Controls Men Smoothly"?7

The men of ancient times said, "The mind of man is peril-

ous, the mind of the Way is obscure. Only through concentra-

tion and oneness can you sincerely hold fast to the mean."8

To let the fingernails grow long and the hair become like a

tangle of weeds, to go all year without bathing, now exposing

the body to the burning sun, now refusing to eat the five

grains—these are the ways of the six teachers of heretical doc-

trines.9 They are not the ways of the Buddha. And practices

that resemble these, even though they may not be the same,

one should recognize as the ways of heretical doctrines, un-

worthy to be trusted and followed.

In general, to remove oneself from the doting involved with

kin and family, to sit upright in a grass hut, to circle about be-

neath the trees, to be a friend to the voice of the brook and the

hue of the hills10—these are the practices adopted by the an-

cient sages and the model for ages to come.

I once heard an old man say that, because many of the

monks of former ages used to hide themselves away in the

deep mountains and remote valleys, they were far removed

from human settlements and constantly encountered difficul-

ties in begging for food. At times they had to gather mountain

fruits or pick wild greens in order to provide themselves with

enough to eat.

Nowadays we have our Mokujiki practitioners who, though

they reside in the communities where others live, make a

point of refusing to eat the five grains.11 What kind of practice

is this? It resembles Buddhist ways but is not really Buddhist;

it resembles the austerities of the heretical teachers but is not

really heterodox. Would we be justified in saying that such

men are parading their eccentricity and leading the populace

astray? If not, then we must suppose them to be quite mad

and intoxicated with the Buddhist Law. The people of the time

pay them great reverence, looking on them as arhats possessed

of all the six supernatural powers, and they themselves, be-

cause of the persistent reverence paid them by others, come to

believe that their own way is vastly superior. What a spec-

tacle, what a spectacle! One blind man leading a multitude of

the blind—soon they will tumble into a great pit!

When the men of old sacrificed themselves for the sake of

the Dharma, they rid themselves of all ego, never greedy for

fame or gain, seeking the Way alone. Therefore the heavenly

beings bestowed alms upon them and the dragon spirits

looked up to them. But the men of today claim they are carry-

ing out practices difficult to practice, enduring deprivations

difficult to endure, and yet all they are doing is needlessly

wearying the body given them at birth by their father and

mother. What a waste, what a waste! It is of course not right to

try to cling to life and limb at all cost. But deliberately to place

them in peril—how could that be right either? To go too far is

as bad as not going far enough.12

As a matter of fact, I know that there is nothing difficult

about endangering the body; the difficult thing is to keep it

constantly whole and well. Therefore I say, the most difficult

thing of all is to preserve continuity.13 In all due respect I write

these words for those who are practicing the Way, so that they

may consider them wisely and make their choice.

The Shramana Ryōkan

JEGYZETEK

1. According to ch. 10 of the Vimalakirti Sutra, Vimalakirti through his

magical powers obtained "pure rice," a kind of gruel made of rice cooked in

milk and butter, from the Buddha mentioned above, and fed it to a vast multi-

tude, yet the supply never ran out. Chunda, a humble blacksmith, presented a

meal to Shakyamuni and his disciples that turned out to be Shākyamuni's

last, since he grew ill and died as a consequence; however, he commended

Chunda for the spirit in which the meal was offered. The text of the "State-

ment on Begging for Food" is found in Tōgō Toyoharu, Ryōkan shishū,

pp. 421-28.2. The Fo-ch'ui pan-nieh-p'an lüeh-shuo chiao-chieh ching (Busshi hatsunehan

ryakusetsu kyōkai kyō), a brief work of doubtful origin describing the Bud-

dha's final hours and his dying instructions to his disciples; it is especially

honored in the Zen sect.3. Because by begging from the poor, he could give them an opportunity to

gain religious merit.4. Ryōkan summarizes the description of the incident from ch. 3 of the

Vimalakirti Sutra.5. There are various formulations of the rules for zazen or Zen meditation.

The quotation here resembles the rules laid down by Dōgen (1200-53), who

has come to be regarded as the founder of the Sōtō branch of the Zen sect

in Japan. Those who have done zazen in Japanese temples in winter may have

had occasion to wonder just what the Zen definition of "too cold" may be.6. A text recited by Zen practitioners before partaking of a meal.

7. One of the Jugo or Ten Epithets of the Buddha.

8. A celebrated passage from the "Pronouncement of the Great Yü," a sec-

tion of the Confucian Book of Documents.9. Six religious and philosophical leaders who lived at the time of Shākya-

muni and advocated severe ascetic practices.10. An allusion to the famous lines in Su Tung-p'o's so-called enlighten-

ment verse ("Presented to the Chief Abbot of Tung-lin Temple"):The voice of the brook is the eloquent tongue of Buddha;

the hue of the hills—is it not his pure form?11. Mokujiki or "tree-eater," as the name indicates, means one who lives

exclusively on the fruits and nuts of trees. There were several well-known Jap-

anese monks who followed this practice, the most famous being the Shingon

monk Mokujiki Ōgo (1536-1608).12. The last sentence is quoted from the Confucian Analects XI, 15.

13. Ryōkan probably means in particular the continuity of the religious

teachings handed down from the Zen masters of the past.

Cf. pp. 83-85. in:

Ryôkan, moine zen

par Michiko Ishigami-Iagolnitzer*

Paris, Éditions du CNRS, 1991, p. 294.

* 美智子石上 Michiko Ishigami (1935-2016)

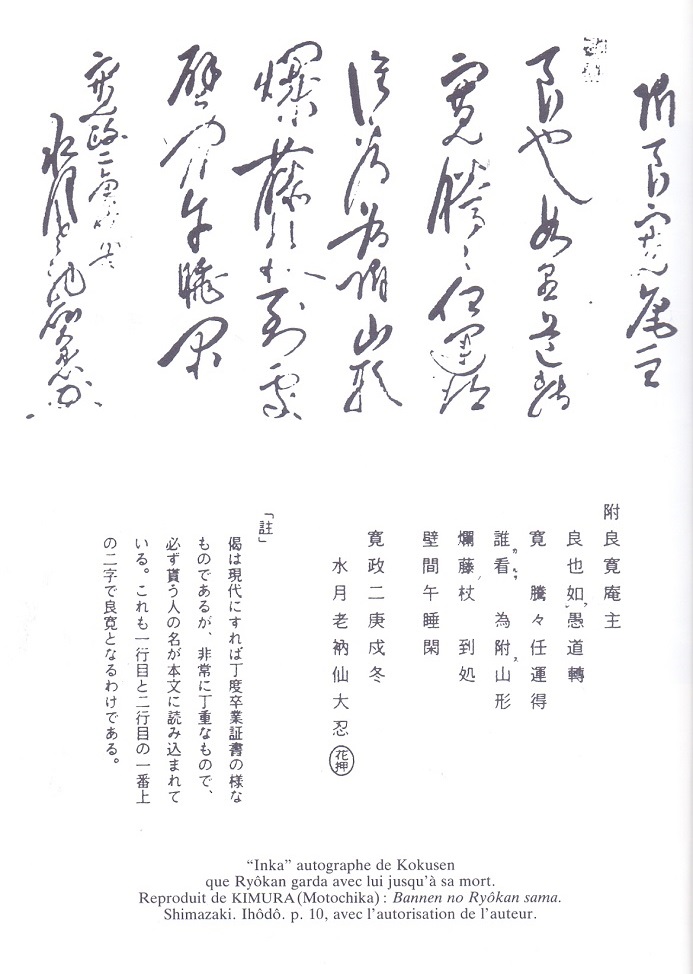

Ryo, foolish though you look, now you've found a very wide but true path, which few people can get to.

In celebration of your accomplishment, you shall have this walking stick. It looks plain but it's not.

Go, go, in peace. Now the whole world is your residence. With this stick leaning against any wall, you might have a good slumber.

(The certificate given to Ryōkan by his Buddhist master, Kokusen, in 1790.)

![]()

Rjókan: Versek és anekdoták

In: Buddha tudat, Zen buddhista tanítások. Ford., szerk. és vál. Szigeti György

Budapest, Farkas Lőrinc Imre Könyvkiadó, 1999, 126-130. oldal

Ősz

A keskeny ösvényt sűrű erdő öleli;

Merre szem ellát, a hegyek sötétbe borulnak.

Az őszi levelek már lehullottak.

Eső nem esik, a rideg köveket moha lepi.

Alig ismert úton hazatérve remetelakomba,

Frissen szedett gombát viszek kosaramban,

S a templomi forrás tiszta vizét korsómban.

Tiszta szív, tiszta világ

Az eső elállt, a felhők tovaúsznak,

S az ég kiderül.

Ha szíved tiszta, akkor a világodban minden tiszta.

Elhagyva ezt a tünékeny világot s önmagadat,

A hold s a virágok vezetnek az Úton.

A zen szerzetes élete

A napot koldulással töltöttem a városban.

Most békésen üldögélek egy szikla alatt a esti hidegben.

Egyedül, egy köpennyel és egy csészével -

Valóban a zen szerzetes élete a legjobb!

Magány

Csendesen üldögélek,

s hallgatom a lehulló faleveleket -

Egy magányos kunyhó, egy lemondó élet.

A múlt elhomályosodott,

már semmire sem emlékszem.

Kabátujjamat áztatja a könnyem.

Tél

Friss reggeli hó az oltár szentély előtt.

S a fák!

Vajon a duzzadó őszibarack-virágoktó1 fehérek?

Vagy netalántán a hótó1 fehérek?

A gyermekkel boldogan hógolyózom.

Őszi vers

Kőlépcsőzet, egy kupac csillogó, zöld moha;

A szellő a cédrus s a fenyő illatát viszi.

Az eső elállt, s az ég kezd kitisztulni.

Szólítgatom a gyermekeket, ahogy megyek a faluba,

s miután sok-sok szakét megittam,

boldogan költöm ezeket a verseket.

A holdat nem lehet ellopni

Rjókan egyszerű életet élt kicsinyke kunyhójában, a

hegy lábánál. Az egyik éjszakán egy tolvaj tört be a

kunyhóba, felforgatta, de nem talált semmit, amit ellophatott

volna.

Rjókan éppen visszatért, és elcsípte a tolvajt.

- Biztosan hosszú urat kellett megtenned, hogy láthass

engem - mondta Rjókan a csavargónak. - Nem

térhetsz vissza üres kézzel. Kérlek, fogadd el a ruhámat

ajándékba.

A tolvaj elképedt, fogta a ruhát és elsomfordált.

Rjókan, a holdban gyönyörködve, meztelenül ült:

- Szegény ember - merengett a zen mester -, bárcsak

neki adhattam volna ezt a gyönyörű holdat is!

Bújócska

Rjókan bújócskát játszott a gyermekekkel, s egy közeli

pajtában bújt el. A gyermekek rájöttek, hová bújt, s elhatározták,

hogy megviccelik. Gyorsan elfutottak,

anélkül, hogy szóltak volna neki, vége a játéknak. Másnap

reggel a földműves felesége bement a pajtába, s

meghökkenve látta a sarokban guggoló Rjókant,

- Mit csinál itt, Rjókan? - kérdezte.

- Pszt! - suttogta Rjókan. - Még megtalálnak a

gyermekek.

Hal

Egyszer Rjókan egy fiatal szerzetessel vándorolt. Megálltak

egy teaháznál, ahol étellel kínálták őket. Az ételben

hal is volt, amit a fiatal szerzetes érintetlenül meghagyott,

miként az ortodox buddhisták közt szokás,

Rjókan azonban habozás nélkül bekapta.

- Az ételben hal is van - szólt a fiatal szerzetes.

- Bizony, és milyen finom - válaszolta Rjókan mester

vigyorogva.

Jó útra térés

Rjókan egész életét a zen gyakorlásának szentelte. Egy

napon fülébe jutott, hogy unokafivére, a rokonság zúgolódása

ellenére, kéjnőre szórja a pénzét. Mivel az

unokafivér verte át Rjókan helyét a családi birtok igazgatásában,

ezért félő volt, hogy elherdálja a vagyont. A

rokonság megkérte Rjókant, hogy tegyen valamit ez

ügyben.

Rjókannak hosszú utat kellett megtennie, hogy újra

láthassa unokafivérét, akivel már hosszú évek óta nem

találkozott. Az unokafivér úgy tűnt, örült a találkozásnak,

és meghívta Riókant, hogy töltse az éjszakát az

otthonában.

Rjókan egész éjszaka meditációban ült. Mikor reggel

indulni készült, így szólt unokafivéréhez:

- Biztosan nagyon öreg vagyok már, hogy így reszket

a kezem. Segítenél bekötni a szalmapapucsomat?

Az unokafivér készségesen segített neki.

- Köszönöm. Látod? Az ember napról napra öregebb

és gyengébb lesz! Vigyázz nagyon magadra!

Rjókan elment, egy szóval sem említve a kéjnőt

vagy a rokonság zúgolódását. Az unokafivér attól a

naptól kezdve felhagyott a pazarlással.

Datolyaszilva

Egyszer Rjókan egy falu közelében sétált, amikor egy

gyermek kiáltozására lett figyelmes:

- Segítség! Segítsen, kérem!

A kisfiú egy datolyaszilvafa csúcsán csüngött. Rjókan

lesegítette, és így szólt hozzá:

- Öcskös, majd én szedek neked gyümölcsöt!

Rjókan felmászott a fára, s leszakított egy datolyaszilvát.

Beleharapott, hogy megízlelje, mert az éretlen

datolyaszilva meglehetősen fanyar ízű. „Hm, de finom!”

- hümmögött Rjókan, s lakmározni kezdett a fa

terméséből. A kisfiú türelmetlenül felkiáltott a fára:

- Rjókan, én is kérek egyet!

Rjókan, aki teljesen megfeledkezett a kisfiúról, lenézett,

s kacagva ledobott egy mézédes datolyaszilvát a

fiúnak.