ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

一休宗純 Ikkyū Sōjun (1394-1481)

Death Poem

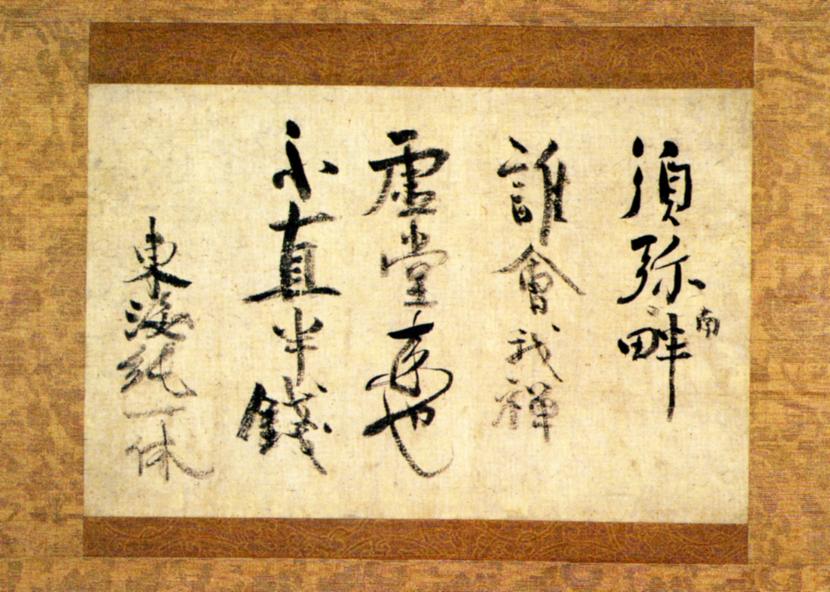

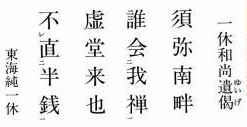

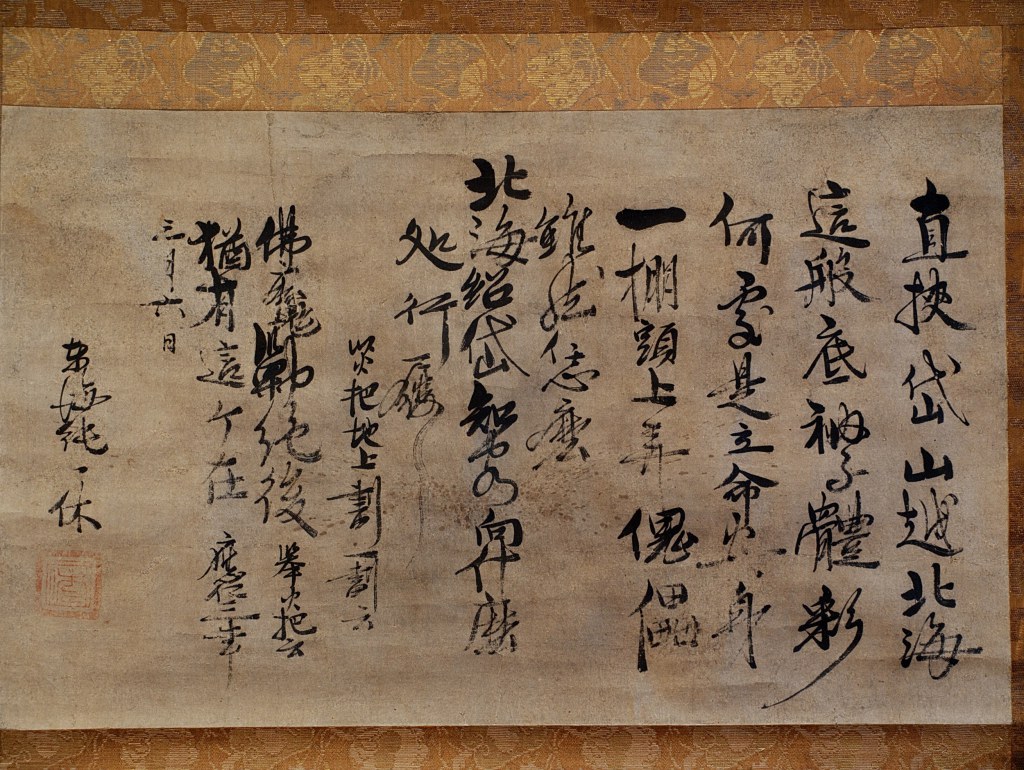

Ikkyū's death poem survives in his own hand at 眞珠庵 Shinjū-an, 大徳寺 Daitoku-ji

In all the world

Who understands my Zen?

Even if Hsü-t'ang* were to come,

He wouldn't be worth half a copper.Translated by James H. Sanford

DEATH POEM

by James H. Sanford

In: Zen-man Ikkyū, (Harvard Studies in World Religions; no. 2), Scholars Press, Chico, CA. 1981, pp. 190-192.

It was the custom for a declining Zen master to author

a final poem as a legacy to his followers. Such a death

poem might be written a good deal in advance of the man's

demise, or it might be written from his deathbed. In either

case, the poem was taken to be an especially meaningful expression

of the monk's entire lifetime.

There are at least three poems that are commonly

presented as Ikkyū's death poem. The first of these is:

Dimly, dimly, thirty years,

Weakly, weakly, thirty years;

Dimly, weakly, sixty years.

In the end I take a crap as offering to Brahma.

This is resonably good Zen "theology" and would certainly

not be an unlikely self-statement from Ikkyū, but it

really seems a bit shallow as a summation of his entire

life. Furthermore, it appears to date from his sixtieth

year and is written in Japanese, whereas the normal

Ōtōkan death poems were always in Chinese.

A second poem is also a bit too shallow and found

only in a Japanese version:

The loan was taken a month ago, yesterday.

Repayment is this month, today.

I return four of the five I borrowed,

I still hang on to Original Emptiness.

The third poem survives in Ikkyū's own hand:

In all the world

Who understands my Zen?

Even if Hsü-t'ang* were to come,

He wouldn't be worth half a copper.**

There can be little doubt that this was Ikkyū's actual

death poem and that it dates from his final days and

quite possibly his final hours. First of all, the poem is

written in Chinese in the four lines of four characters

style that was the standard format for death poems of the

Hsü-t'ang/Daiō lineage. Beyond this, the text echoes quite

closely the content of the death poems of the earlier

masters of Ikkyū's line--poems in which three themes

emerge repeatedly--an explicit recognition of impending

death, a resigned but somehow despairing sense of

aloneness before this final event, and the expressed fear

that whatever the religious insights the writer has

attained, they are almost certain to be lost to later

generations. Ikkyū's poem stresses the last of these

themes, but the other two are also there just below the

surface. The closing two lines make up a quite defensible

Zen statement, but their surprising harshness is, of

course, typically Ikkyū.

Aside from this internal literary evidence, and the

fact that it is clearly written in his hand, the scroll

itself virtually bespeaks Ikkyū in that he has initially

omitted the third character of the first line and then

later scrawled it into the margin between the second

character and the misplaced fourth character. Few

things could be more characteristic of Ikkyū than

this iconoclastic refusal to "pretty things up".

On the reverse side of the scroll is the signature

Sōan, the date 1641, and the explanation of the scroll's

transmission. According to this inscription, the scroll

was originally placed in the hands of Ikkyū's disciple,

Bokushitsu, who passed it on to a monk called Shūgaku who

gave it to one Gyokuhō Sōrin. Sōrin in his turn put it

in the hands of the Shinjū-an hermitage for further

safekeeping.

* 虚堂智愚 Xutang Zhiyu (1185-1269) [Jap. Kidō Chigu]

**Other English versions:

South of Mt. Sumeru,

Who meets my Zen?

Even if Hsü-t'ang* comes

He's not worth half a penny.Translated by Sonja Arntzen

[1]

In this vast universe,

Who understood my Zen?

Even if Hsü-t'ang* himself came back

He would not be worth half a penny![2] Death Verse

In this vast realm

Who understands my Zen?

Even if Master Kidō* shows up,

He is not worth a cent!Translated by John Stevens

South of Mount Sumeru

Who understands my Zen?

Call Master Kido* over--

He's not worth a cent.Translated by Lucien Stryk & Takashi Ikemoto

In all the kingdom southward

From the center of the earth

Where is he who understands my Zen?

Should the master Kido* himself appear

He wouldn't be worth a worn-out cent.Translated by Yoel Hoffmann

The kingdom described in Ikkyu's poem is the continent southward from Mount Shumi (Skt., Sumeru), a mythical peak which, according to ancient Indian tradition, stands at the center of the world. The four kingdoms extending from the mountain's four sides are supposed to contain all of humanity. The Southern continent includes India, China, and Japan, the countries where Buddha's doctrine had been spread. The question "Where is he who understands my Zen?" is not to be taken as a boast. Where Zen ceases to be a doctrine and becomes reality, each individual stands alone, and no one can take his place. This being so, even the Chinese Zen master Kido Chigu (Hsü-tang Chih-yü, 1185-1269), whom Ikkyu considered his spiritual father, could neither add to nor detract from what Ikkyu was at that moment-- an old man of eighty- eight years about to die.

Many of Ikkyu's writings deal with death. One of them ends with the following words: "And now, at the hour of my death, my bowels move-- an offering raised to the Lord of Worlds." The frankness of the statement is characteristic of his style, but it ought not to be taken as profane. The image of a dying man who can no longer control his body and who defecates in his bed is no less "sacred" than that of a believer who brings flowers as an offering to his god; all is accepted with equanimity by the Lord of Worlds, the god Bonten (Skt., Brahmadeva).

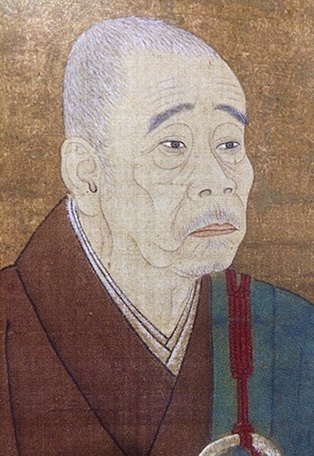

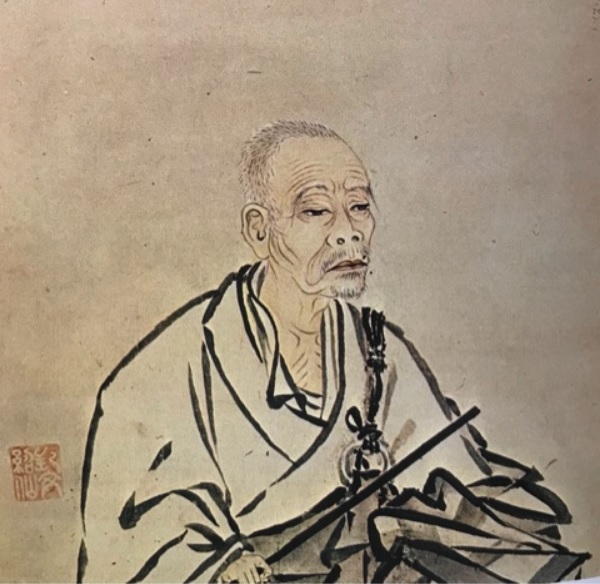

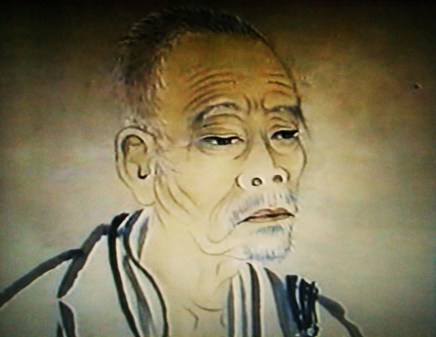

Ikkyū's "Final Portrait" by

曽我蛇足

Soga Jasoku III (紹仙

Shōsen), c. 1481;

at 眞珠庵 Shinjū-an, 大徳寺 Daitoku-ji, Kyoto

Tartalom |

Contents |

Ikkjú, névváltozat: Ikkjú Szódzsun (japánul: 一休宗純, Hepburn-átírással: Ikkyū Sōjun) (1394–1481), a rinzai szektához tartozó zen buddhista szerzetes, költő, a japán teaszertartás egyik megteremtője. Gy. Horváth László. Japán kulturális lexikon. Corvina. 1999 John Stevens: Ikkjú Szódzsun Kiliti Joruto: Ikkjú [Legendák Ikkjú életéből] Bakonyi Berta: Másotok sincs... Oravecz Imre: Szerzetes a bordélyban

Terebess Gábor: Ikkjú dókáiból, búcsúverse PDF: Csontváz–dalocskák

狂雲集 Kyōunshū = Kerge Felhő összegyűjtött versei 道歌 Dōka = Tanköltemények

PDF: La saveur du zen: poèmes et sermons d'Ikkyû et de ses disciples |

道歌 Dōka

狂雲集 Kyōunshū / Crazy Cloud Anthology

仏鬼軍 Bukkigun

阿弥陀裸物語 Amida hadaka monogatari

自戒集 Jikaishū 摩訶般若波羅蜜多心経解 Maka hannya haramitta shingyō kai Ikkyu: Zen Eccentric PDF: Zen Radicals, Rebels and Reformers |

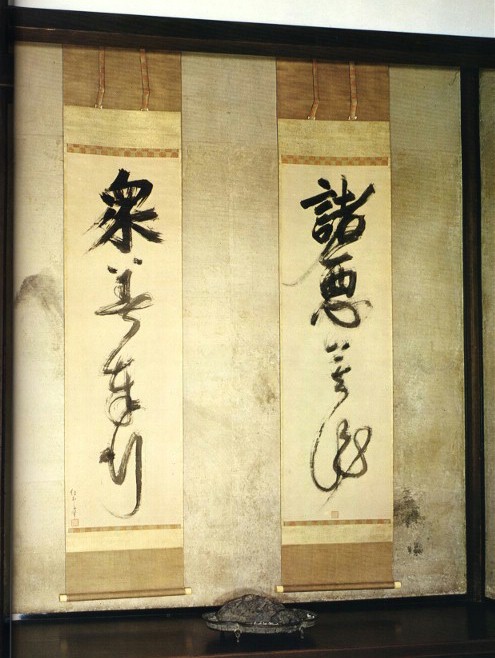

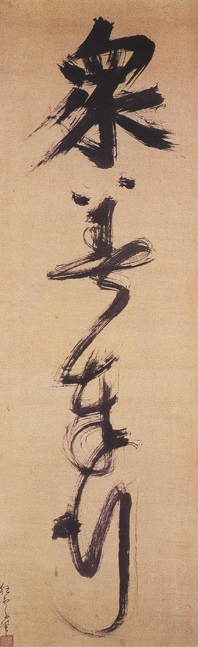

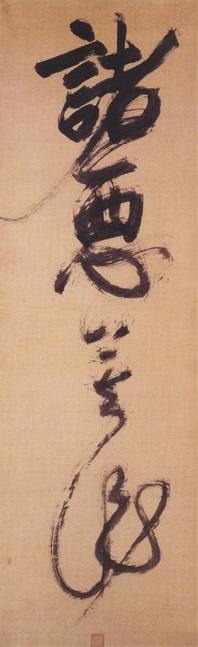

Calligraphy in Ikkyū's hand

Paired calligraphic scrolls in Ikkyū's hand

諸悪莫作 衆善奉行 (七仏通戒偈 Admonition of the Seven Buddhas; first two lines)

Shoaku makusa, shūzen bugyō "Abjure all evil [right], practice all good [left]"

at 眞珠庵 Shinjū-an, 大徳寺 Daitoku-ji, Kyoto

There is a famous epigram that supposedly expresses a quintessential doctrine shared by Sakyamuni and the six Buddhas who are said to have preceded him. This "Admonition of the Seven Buddhas" is rendered in four lines of verse:

Sabba pāpassa akaranam

Kusalassa upasampadā

Sacitta pariyodapanam

Etam Buddhāna sāsanam.

The calligrapher, the famous Rinzai priest Ikkyû, brings the couplet into a visual performance by beginning at the top of each line with a (relatively) straightforward shin style rendering. As the line is written down the scroll, though, the script style changes to gyô and finally sô style. Changes in script style exhibited like this, in a single line of calligraphy, perform for us, each time we see them, the writing itself, by making visually apparent the movement of the writer. In the kanji at the bottom of each scroll you see areas of white left untouched as the brush, now partly emptied of its ink, speeds through the requisite stroke. These areas within the stroke are called "flying white." To produce them on mulberry paper or silk like this requires speed and resolution in creating the stroke in question. It manifests a preconscious bodily understanding of how the kanji is to be written, and in peformance itself, offers not time for reflection, much less hesitation. The spontaneity captured here is something much prized in Japanese art.

Ikkyū's Calligraphy http://zenartexperience.wordpress.com/category/ikkyu

This monk has passed through the narrowest mountain paths to reach the northernmost seas,

and also has the experience of crawling through the lowest valleys.

If you want to find a safe place to pass your life,

Sit on the top shelf like a puppet!

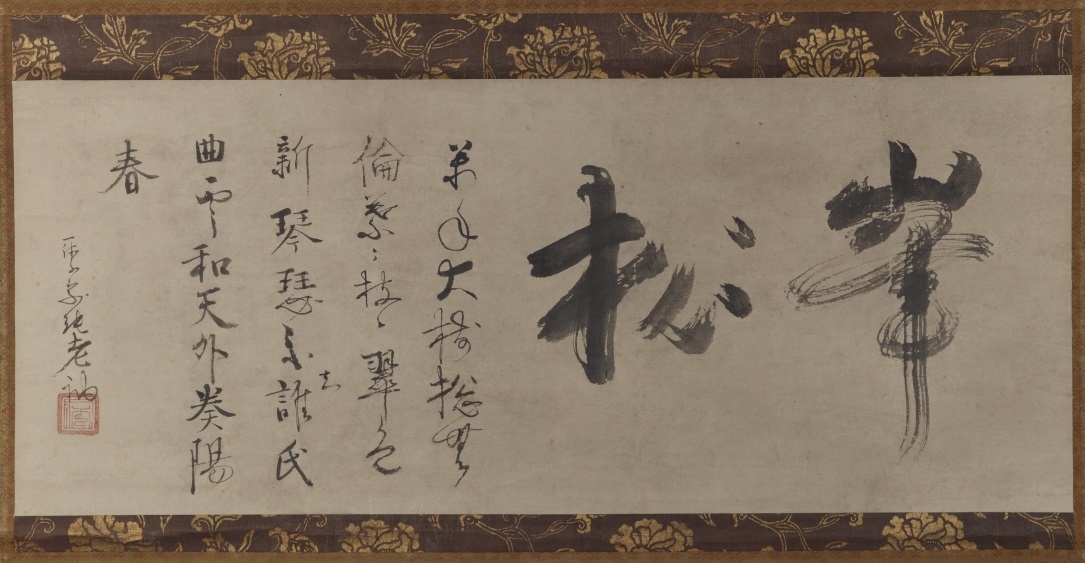

一休宗純墨跡_七言絶句_峯 松

Chinese Style Quatrain in Seven Word Phrases “Pine Tree on a Peak”

Tokyo National Museum

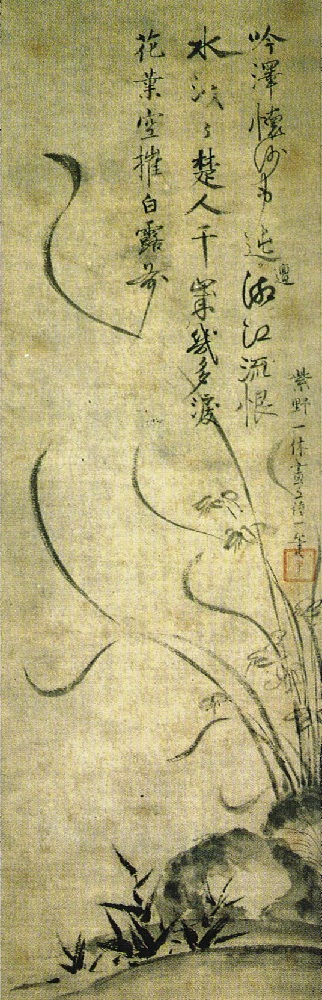

"Orchids," a pair, painting and calligraphy by Ikkyū

Umezawa Collection, Tokyo