ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

鈴木 大拙 貞太郎 Suzuki Daisetsu Teitarō (1870-1966)

[Suzuki Daisetz Teitaro; D. T. Suzuki]

D. T. Suzuki: A zen mezején > ![]() DOC >

DOC > ![]() PDF

PDF

Eredeti címe: The Field of Zen

Originally published by The Buddhist Society, London in 1969

Fordította: Rafalszky Katalin (A Zen területe címmel)

Színjátszó Központ módszertani sorozata

Szerkeszti: Bucz Hunor

Felelős kiadó: Bálint Judit, az Ady Művelődési Központ igazgatója

Készült: Budapesten, 1982 novemberében, 60 példányban

Elektronikus kiadás: A zen mezején, Terebess Ázsia E-Tár, 2003

TARTALOM

A szerkesztő előszava

Dr. D. T. Suzuki

A The Times 1966. július 13-i számában megjelent nekrológ1. Régi emlékek

(A Buddhist Society fennállásának 40. évfordulójára - 1964 novemberében)2. Buddha és Zen

(előadás a Manchester College Oxfordban, 1953 júniusában)3. A Satori jelentése

(A Buddhista Társaságban mondott előadás, 1953 szeptemberében)4. Mondo

(A Middle Way számára. 1953 augusztusában)5. Maha Prajna és Maha Karuna

(A Buddhista Társaságban elhangzott előadás, 1958 májusában)6. A buddhizmus analitikus és szintetikus megközelítése

(A Buddhista Társaságban elhangzott előadás, 1953 júniusában)7. Hogyan lehet behatolni a valóságba

(A Buddhista Társaságban elhangzott előadás, 1954 júliusában)8. Az én és a Zen

(Előadás a Caxton Hall-ban, 1953 szeptemberében)9. Eckhart és a Zen buddhizmus

(A Middle Way számára, 1955 augusztusában)10. A Soto mesterek tanítása

(Kiadásra átadva 1958-ban)11. A Shin és a Zen összehasonlítása

(Válaszok a Zen Iskolában feltett kérdésekre - 1953 júniusában)12. A Zen buddhizmus hite

(A Buddhista Társaságban elhangzott előadás feljegyzéseiből, 1958 júniusában)13. A válasz a kérdésben van

(Feljegyzések a Buddhista Társaságban elhangzott előadásról 1953 júniusában)14. Zen meditáció

(Feljegyzések a Zen Iskolában tartott előadásról - 1958)15. Hirtelen és fokozatos megvilágosodás

(A Zen Iskolában tartott beszédből részletek - 1958 májusában)

D. T. Suzuki: Előadások a zen-buddhizmusról

Gy. Horváth László fordítása

Erich Fromm - D. T. Suzuki: Zen-buddhizmus és pszichoanalízis c. kötetből

Lankávatára szútra ![]() PDF

PDF

Migray Emőd fordítása

The Lankavatara Sutra. A Mahayana Text. Translated into English from the Sanskrit by D. T. Suzuki. 1932. c. kötetből

Thomas Merton: A zen és a falánk madarak

Erős László Antal fordítása

Thomas Merton: D. T. Suzuki, az ember és munkássága

Bölcsesség az ürességben

Thomas Merton és Daisetz T. Suzuki párbeszédeElőszó

Daisetz T. Suzuki: TUDÁS ÉS ÁRTATLANSÁG

Thomas Merton: A PARADICSOM VISSZASZERZÉSE

Daisetz T. Suzuki: ZÁRÓ MEGJEGYZÉSEK

Thomas Merton: ZÁRÓ MEGJEGYZÉSEK

Utószó

Bevezetés a zen buddhizmusba

C.G. Jung előszavával

Agócs Tamás fordítása

Polaris Könyvkiadó, 2019, 174 oldal

„Ha a tudat valamilyen oknál fogva készen áll, felrepül egy madár, megszólal egy csengő, s az ember egyszeriben visszatér az eredeti otthonába, vagyis felfedezi valódi önmagát. Kezdettől fogva semmi sem volt rejtve előttünk; minden, amit látni szerettünk volna, ott volt végig a szemünk előtt, csak mi magunk nem akartunk róla tudomást venni. A zenben ezért nincs mit magyarázni, nincs mit tanítani, nincs mit hozzáadni a tudásunkhoz. Ha nem belőlünk hajt ki, valójában semmiféle tudás nem a miénk; legfeljebb csak idegen tollakkal ékeskedünk.”

A zen semmire sem akar bennünket elemző gondolkodás útján megtanítani, s még csak olyan tantételrendszerrel sem rendelkezik, amelyet követőinek el kellene fogadniuk. E szempontból a zen, ha úgy tetszik, meglehetősen zavaros. Követőinek persze lehetnek hitelveik, de csakis önszántukból és saját érdekükben; ezt nem a zennek köszönhetik. A zenben éppen ezért nincsenek szent könyvek, sem tantételek, sem jelképes formulák, melyek által közelebb lehetne férkőzni a zen rejtett jelentéséhez. Ha valaki azt kérdezné: akkor mi a zen tanítása, azt válaszolnám, hogy semmi. Amennyiben van bármiféle tanítása, az mind az ember saját tudatából ered. Magunk tanítjuk magunkat; a zen csak utat mutat. Hacsak ez nem tanítás, a zenben egész biztosan semmi sincs, amit a zen sarkalatos tantételének vagy alapfilozófiájának lehetne nevezni.

45. oldalAmikor Sákjamuni Buddha megszületett, a hagyomány szerint egyik kezét az égnek emelte, a másikkal pedig a föld felé mutatott, miközben nagy hangon kijelentette: „Az ég fölött és az ég alatt egyedül én vagyok Tiszteletre Méltó.” Ummon, a róla elnevezett zen iskola alapítója erre az alábbi megjegyzést tette: „Ha vele lettem volna, amikor ezt mondja, bizonyosan egy csapásra agyonütöm, és a holttestét bevágom egy éhes kutya pofájába.”

48. oldalA zen érez és tapasztal, nem elvonatkoztat vagy meditál.

50. oldalEgy régi zen mester, amikor a zen mibenléte felől érdeklődtek nála, válaszként felemelte egyik ujját; egy másik belerúgott egy labdába; egy harmadik arcul ütötte kérdezőjét.

55. oldalAz utánzás rabszolgaság. Soha nem a tanítás betűjét kell követni, hanem a szellemét kell felfogni. A magasabb rendű állítások a szellemben élnek. S hol a szellem? Keressük a mindennapos tapasztalásunkban – bőven találunk ott bizonyítékot mindarra, amire szükségünk van.

90. oldalNem szabad elfelejtenünk, hogy a holdra mutató ujj mindig is ujj marad, és semmilyen körülmények között nem lehet magává a holddá változtatni. Mindig ott leselkedik ránk a veszély, ahol az ész alattomban befurakszik, és holdnak veszi a mutatóujjat.

97. oldalDe van itt egy veszélyes buktató, amit a zen tanítványnak roppant elővigyázattal el kell kerülnie. A zent soha nem szabad összetévesztenie a naturalizmussal vagy a szabadossággal; vagyis azzal, hogy saját természetes hajlamait kövesse anélkül, hogy megkérdőjelezné azok eredetét, illetve fontosságát. Nagy különbség van az emberek és az állatok cselekedetei között, mivel az állatoknak nincs sem erkölcsi, sem vallási érzékük. Nem képesek erőkifejtésre annak érdekében, hogy javítsanak az életkörülményeiken, vagy előrehaladjanak a magasabb rendű erényekhez vezető úton.

107. oldalHa nem belőlünk hajt ki, valójában semmiféle tudás nem a miénk; legfeljebb csak idegen tollakkal ékeskedünk.

116. oldalA vallási vezetők és a tekintélyes filozófusok által addig alkalmazott intellektuális jellegű magyarázatok és buzdító intelmek nem érték el a kívánt hatást, hanem épphogy egyre jobban félrevezették a tanítványokat. Különösen így volt ez akkor, amikor a buddhizmus Kínába került. A gyakorlatiasabb kínaiak tanácstalanul álltak az Indiából örökölt metafizikai absztrakciók és bonyolult jógarendszerek előtt, nem tudván, hogyan ragadják meg a Sákjamuni Buddha tanításának központi gondolatát. Ezt vette észre Bódhidharma, a Hatodik Pátriárka, Baszo és a többi kínai mester, aminek a zen kialakulása és fejlődése lett a természetes következménye.

120. oldal[The bamboo-shadows move over the stone steps

as if to sweep them, but no dust is stirred;

The moon is reflected deep in the pool, but the

water shows no trace of its penetration.]A bambuszárnyak a kőlépcsőt súrolják,

mintha felsöpörnék, a por mégse rezdül.

A hold a tó mélyén visszatükröződik,

a vízen mégse látszik behatolás nyoma.

165. oldal, Agócs Tamás fordítása angolbólVö.

禪林句集 Zenrin-kushū

A Zen-erdő összegyűjtött mondásaiból

Fordította: Terebess Gábor

竹影掃堦塵不動

月穿潭底水無痕

Chikuei kai o haratte chiri ugokazu,

Tsuki tantei o ugatte mizu ni ato nashi.Lépcsőt söpör bambusz árnya,

bár a por rendíthetetlen.

Tómélybe váj hold sugára,

bár a víztükör sértetlen.

Balogh B. Márton: Suzuki és Mihoko > ![]() PDF

PDF

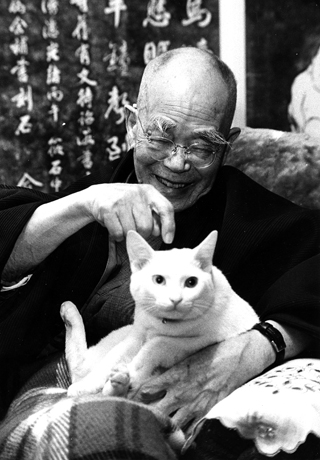

岡村美保子 Mihoko Okamura (1935-2023). 1953-tól 1966-ban bekövetkezett haláláig D.T. Suzuki személyi asszisztense volt.

2000 című folyóirat, 1991 (3.évfolyam) október, 49-54. old.

Suzuki-anekdoták

John Cage: A csend c. könyvéből

Erős László Antal fordítása

Kéziratként a fordítótól

Critics frequently cry “Dada” after attending one of my concerts or hearing one of my lectures. Others bemoan my interest in Zen. One of the liveliest lectures I ever heard was given by Nancy Wilson Ross at the Cornish School in Seattle [in 1936]. It was called Zen Buddhism and Dada . It is possible to make a connection between the two, but neither Dada nor Zen is a fixed tangible. They change; and in quite different ways in different places and times, they invigorate action. What was Dada in the 1920's is now, with the exception of the work of Marcel Duchamp, just art. What I do, I do not wished to be blamed on Zen, though without my engagement with Zen (attendance at lectures by Alan Watts and D. T. Suzuki, reading of the literature), I doubt I would have done what I have done. I am told that Alan Watts has questioned the relationship between my work and Zen. I mention this in order to free Zen from any responsibility for my actions. I shall continue making them, however. I often point out that Dada nowadays has in it a space, an emptiness, that it formally lacked. What, nowadays, America mid-twentieth century, is Zen?

A kritikusok, miután részt vettek némelyik hangversenyemen, vagy meghallgatták valamelyik előadásomat, gyakorta dadát kiáltanak. Mások a zen iránti érdeklődésemen sajnálkoznak. Az egyik legragyogóbb előadást, amelyet valaha hallottam, Nancy Wilson Ross tartotta Seattle-ben, a Cornish Schoolban. Az volt a címe, hogy A zen buddhizmus és a dada. Lehet kapcsolatot találni a kettő között, de sem a dada, sem a zen nem szilárd, megfogható valami. Változnak; és meglehetősen eltérő módokon, különféle helyeken és időpontokban cselekvést hívnak életre. Ami a dada az 1920-as években volt, az ma, Marcel Duchamp munkásságának kivételével, csupán művészet. Ami engem illet, én nem szeretném, ha a zent vetnék a szememre, bár a zen iránti elkötelezettségem (Alan Watts és D.T. Suzuki előadásain való részvétel és az irodalom elolvasása) nélkül kétlem, hogy azt csináltam volna, amit. Mondták, hogy Alan Watts megkérdőjelezte a munkásságom és a zen közötti kapcsolatot. Ezt azért említem, hogy felmentsem a zent a tetteim miatti mindenféle felelősség alól. De azért továbbra is el fogom követni tetteimet. Gyakran rámutatok, hogy a dadában manapság van egyfajta tér, egyfajta üresség, amelynek korábban híján volt. Vajon manapság, Amerikában a huszadik század közepén, micsoda a zen?

..............................

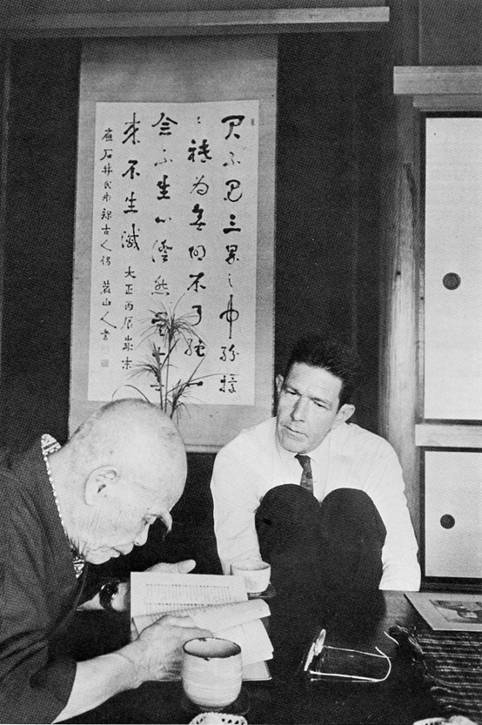

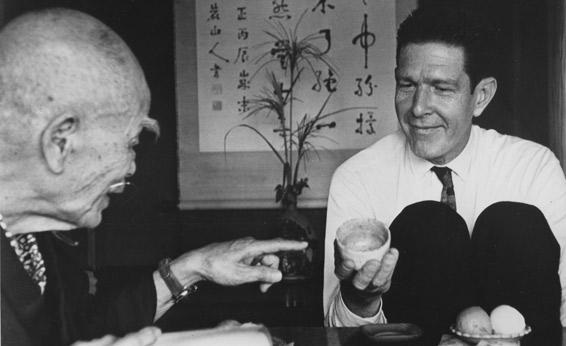

John Cage meets D.T. Suzuki in Japan, 1962.

An Indian lady invited me to dinner and said

Dr. Suzuki would be there. He was.

Before dinner I mentioned Gertrude Stein.

Dr. Suzuki had never heard of her.

I described aspects of her work, which he

said sounded very interesting.

Stimulated, I mentioned James Joyce, whose name

was also new to him. At dinner he was

unable to eat the curries that were offered,

so a few uncooked vegetables and fruits were

brought, which he enjoyed.

After dinner the talk turned to metaphysical

problems, and there were many questions,

for the hostess was a follower of a

certain Indian yogi and her guests were more

or less equally divided between allegiance to

Indian thought and to Japanese thought.

About eleven o'clock we were out on the street

walking along, and an American lady said

to Dr. Suzuki, “How is it, Dr. Suzuki?

We spend the evening asking you

questions and nothing is decided.” Dr.

Suzuki smiled and said, “That's why

I love philosophy: no one wins.”

Egy indiai hölgy meghívott vacsorára, és azt mondta, hogy Dr. Suzuki is ott lesz. Ott is volt. Vacsora előtt megemlítettem Gertrude Stein nevét. Suzuki nem hallott róla. Vázoltam munkássága bizonyos vonásait, amire azt mondta, hogy nagyon érdekesen hangzik. Felvillanyozva szóba hoztam James Joyce-t, akinek a neve megint csak új volt a számára. Vacsoránál nem tudta megenni a kínált currys ételeket, ezért néhány nyers zöldséget és gyümölcsöt hoztak, ezeket élvezettel fogyasztotta. Vacsora után a beszélgetés metafizikai problémákra terelődött, és rengeteg kérdés merült fel, mert a háziasszony egy bizonyos indiai jógi követője volt, és a vendégei többé-kevésbé azonos számban voltak az indiai és a japán gondolkodás elkötelezettjei. Tizenegy tájban kint sétáltunk az utcán, és egy amerikai hölgy azt mondta: - Hogyan van ez, dr. Suzuki? Egész álló este kérdéseket tettünk fel, és semmi nem dőlt el. - Dr. Suzuki elmosolyodott, és azt mondta: - Ezt szeretem a filozófiában: senki nem nyer.

..............................

Before studying Zen,

men are men and

mountains are mountains.

While studying Zen,

things become confused.

After studying Zen,

men are men

and mountains are mountains.

After telling

this, Dr. Suzuki

was asked,

“What is

the difference between before and

after?”

He

said,

“No difference,

only the feet are a

little bit off the ground.”

A zen tanulmányozása előtt az emberek emberek, a hegyek pedig hegyek. A zen tanulmányozása közben a dolgok összezavarodnak. A zen tanulmányozása után az emberek emberek, a hegyek pedig hegyek. Miután ezt elmondta, dr. Suzukinak feltették a kérdést: - Mi a különbség az előtte és az utána között? - Nincs semmi különbség, csak a lábak kissé elemelkednek a földtől.

..............................

One of Suzuki's books

ends

with the poetic

text of a Japanese monk

describing his attainment of

enlightenment.

The final poem says,

“Now that I'm

enlightened,

I'm just as miserable as ever.”

Suzuki egyik könyve egy japán szerzetes költői szövegével végződik, amely leírja a maga megvilágosodásának bekövetkeztét. Az utolsó vers azt mondja: - Most, hogy megvilágosultam, ugyanolyan szerencsétlen vagyok, mint bármikor előtte.

..............................

During recent years Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki has done

a great deal of lecturing at Columbia University.

First he was in the Department of Religion, then

somewhere else. Finally he settled down on the

seventh floor of Philosophy Hall. The room had

windows on two sides, a large table in the middle

with ash trays. There were chairs around the

table and next to the walls. These were always

filled with people listening, and there were

generally a few people standing near the door.

The two or three people who took the class for credit

sat in chairs around the table. The time was four

to seven. During this period most people now

and then took a little nap. Suzuki never spoke

loudly. When the weather was good the windows

were open, and the airplanes leaving La Guardia

flew directly overhead, drowning out from time to

time whatever he had to say. He never repeated

what had been said during the passage of the airplane.

Three lectures I remember in particular.

While he was giving them I couldn't for the life of me

figure out what he was saying. It was a week or

so later, while I was walking in the woods looking

for mushrooms, that it all dawned on me.

Az utóbbi években Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki nagyon sokat adott elő a Columbia Egyetemen. Először a Vallási Tanszéken volt, aztán valahol másutt. Végül a Filozófiai Intézet hetedik emeletén telepedett le. Az ablakai két irányban nyíltak, középen volt egy nagy asztal hamutartókkal. Székek álltak az asztal körül és a falaknál. Ezeket mindig elfoglalták a figyelő hallgatók, és páran rendszerint az ajtó közelében is álltak. Az a két-három ember, aki felvett tárgyként hallgatta az órát, az asztal körüli székeken ült. Az óra négytől hétig tartott. Ebben a napszakban a legtöbben szunyókáltak néha egy kicsit. Suzuki soha nem beszélt hangosan. Ha az időjárás megengedte, az ablakok nyitva voltak, és a

..............................

There was a lady

in

Suzuki's class

who said

once,

“I have great

difficulty

reading the sermons

of

Meister Eckhart,

because

of all the Christian imagery.”

Dr. Suzuki said,

“That difficulty will disappear.”

Volt egy hölgy Suzuki osztályában, aki egyszer azt mondta: - Számomra nagy nehézséget jelent Eckhart mester prédikációit olvasni a képletes keresztény beszéd miatt. Dr. Suzuki azt mondta: - Ez a nehézség el fog tűnni.

..............................

There was an international

conference of philosophers in

Hawaii on the

subject of Reality.

For

three days Daisetz Teitaro

Suzuki said nothing.

Finally the chairman turned

to him and asked,

“Dr. Suzuki,

would

you say this table

around which we are

sitting is real?”

Suzuki raised his

head and said, “Yes.”

The chairman asked in

what sense Suzuki thought

the table was real.

Suzuki said,

“In every sense.”

Volt egy Nemzetközi Filozófus Konferencia Hawaiin, a Valóság témakörében. Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki három napig nem szólt semmit. Végül az elnök fordult hozzá: - Dr. Suzuki, mondhatje-e, hogy az asztal, ami körül ülünk, valóságos?

Suzuki felemelte fejét és azt mondta: - Igen.

Az elnök megkérdezte, mégis milyen értelemben gondolta azt, hogy az asztal valóságos.

- Minden értelemben - mondta Suzuki.

Lectures on Zen Buddhism

by D. T. Suzuki

In:

Zen Buddhism and Psychoanalysis, Erich Fromm, D. T. Suzuki, and De Martino

George Allen & Unwin, London, 1960,

pp. 1-10 [out of 76].

http://letthechildrencometome.blogspot.hu/2007/06/lectures-on-zen-buddhism-by-d.html

I. EAST AND WEST

1

Many able thinkers of the West, each from his specific point of view, have dealt with this timeworn topic, "East and West," but so far as I know there have been comparatively few Far Eastern writers who have expressed their views as Easterners. This fact has led me to choose this subject as a kind of preliminary to what will follow.

Basho (1644-94), a great Japanese poet of the seventeenth

century, once composed a seventeen-syllable poem known as

haiku or hokku. It runs, when translated into English,

something like this:

When I look carefully

I see the nazuna blooming

by the hedge!

Yoku mireba

Nazuna hana saku

Kakine kana.

It is likely that Basho was walking along a country road when he noticed something rather neglected by the hedge. He then approached closer, took a good look at it, and found it was no less than a wild plant, rather insignificant and generally unnoticed by passers-by. This is a plain fact described in the

2

poem with no specifically poetic feeling expressed anywhere except perhaps in the last two syllables, which read in Japanese kana. This particle, frequently attached to a noun or an adjective or an adverb, signifies a certain feeling of admiration or praise or sorrow or joy, and can sometimes quite appropriately be rendered into English by an exclamation mark. In the present haiku the whole verse ends with this mark.

The feeling running through the seventeen, or rather fifteen, syllables with an exclamation mark at the end may not be communicable to those who are not acquainted with the Japanese language. I will try to explain it as best I can. The poet himself might not agree with my interpretation, but this does not matter very much if only we know that there is somebody at least who understands it in the way I do.

First of all, Basho was a nature poet, as most of the Oriental poets are. They love

nature so much that they feel one with nature, they feel every pulse beating through the veins of nature. Most Westerners are apt to alienate themselves from nature. They think man and nature have nothing in common except in some desirable aspects, and that nature exists only to be utilized by man. But to Eastern people nature is very close. This feeling for nature was stirred when Basho discovered an inconspicuous, almost negligible plant blooming by the old dilapidated hedge along the remote country road, so innocently, so unpretentiously, not at all desiring to be noticed by anybody. Yet when one looks at it, how tender, how full of divine glory or splendor more glorious than Solomon's it is! Its very humbleness, its unostentatious beauty, evokes one's sincere admiration. The poet can read in every petal the deepest mystery of life or being. Basho might not have been conscious of it himself, but I am sure that in his heart at the time there were vibrations of feeling somewhat akin to what Christians may call divine love, which reaches the deepest depths of cosmic life.

The ranges of the Himalayas may stir in us the feeling of sublime awe; the waves of the Pacific may suggest something of infinity. But when one's mind is poetically or mystically or religiously opened, one feels as Basho did that even in every blade of wild grass there is something really transcending all venal, base human feelings, which lifts one to a realm equal in

3

its splendor to that of the Pure Land. Magnitude in such cases has nothing to do with it. In this respect, the Japanese poet has a specific gift that detects something great in small things, transcending all quantitative measurements.

This is the East. Let me see now what the 'Nest has to offer in a similar situation. I select Tennyson. He may not be a typical Western poet to be singled out for comparison with the Far Eastern poet. But his short poem here quoted has something very closely related to Basho's. The verse is as follows:

Flower in the crannied wall,

I pluck you out of the crannies;-

Hold you here, root and all, in my hand,

Little flower-but if I could understand

What you are, root and all, and all in all,

I should know what God and man is.

There are two points I like to notice in these lines:

(1) Tennyson's plucking the flower and holding it in his hand, "root and all," and looking at it, perhaps intently. It is very likely he had a feeling somewhat akin to that of Basho who discovered a nazuna flower by the roadside hedge. But the difference between the two poets is: Basho does not pluck the flower. He just looks at it. He is absorbed in thought. He feels something in his mind, but he does not express it. He lets an exclamation mark say everything he wishes to say. For he has no words to utter; his feeling is too full, too deep, and he has no desire to conceptualize it.

As to Tennyson, he is active and analytical. He first plucks the flower from the place where it grows. He separates it from the ground where it belongs. Quite differently from the Oriental poet, he does not leave the flower alone. He must tear it away from the crannied wall, "root and all," which means that the plant must die. He does not, apparently, care for its destiny; his curiosity must be satisfied. As some medical scientists do, he would vivisect the flower. Basho does not even touch the nazuna he just looks at it, he "carefully" looks at it-that is all he does. He is altogether inactive, a good contrast to Tennyson's dynamism.

I would like to notice this point specifically here, and may

4

have occasion to refer to it again. The East is silent, while the West is eloquent. But the silence of the East does not mean just to be dumb and remain wordless or speechless. Silence in many cases is as eloquent as being wordy. The West likes verbalism. Not only that, the West transforms the word into the flesh and makes this fleshiness come out sometimes too conspicuously, or rather too grossly and voluptuously, in its arts and religion.

(2) What does Tennyson do next? Looking at the plucked flower, which is in all likelihood beginning to wither, he proposes the question within himself, "Do I understand you?" Basho is not inquisitive at all. He feels all the mystery as revealed in his humble nazuna-the mystery that goes deep into the source of all existence. He is intoxicated with this feeling and exclaims in an unutterable, inaudible cry.

Contrary to this, Tennyson goes on with his intellection:

"If [which I italicize] I could understand you, I should know what God and man is." His appeal to the understanding is characteristically \Western. Basho accepts, Tennyson resists. Tennyson's individuality stands away from the flower, from "God and man." He does not identify himself with either God or nature. He is always apart from them. His understanding is what people nowadays call "scientifically objective." Basho is thoroughly "subjective." (This is not a good word, for subject always is made to stand against object. My "subject" is what I like to call "absolute subjectivity.") Basho stands by this "absolute subjectivity" in which Basho sees the nazuna and the nazuna sees Basho. Here is ,no empathy, or sympathy, or identification for that matter.

Basho says: "look carefully" (in Japanese "yoku mireba").

The word "carefully" implies that Basho is no more an onlooker here but the flower has become conscious of itself and silently, eloquently expressive of itself. And this silent eloquence or eloquent silence on the part of the flower is humanly echoed in Basho's seventeen syllables. Whatever depth of feeling, whatever mystery of utterance, or even philosophy of "absolute subjectivity" there is, is intelligible only to those who have actually experienced all this.

In Tennyson, as far as I can see, there is in the first place no depth of feeling; he is all intellect, typical of Western mentality.

5

He is an advocate of the Logos doctrine. He must say something, he must abstract or intellectualize on his concrete experience. He must come out of the domain of feeling into that of intellect and must subject living and feeling to a series of analyses to give satisfaction to the Western spirit of inquisitiveness.

I have selected these two poets, Basho and Tennyson, as indicative of two basic characteristic approaches to reality. Basho is of the East and Tennyson of the West. As we compare them we find that each bespeaks his traditional background. According to this, the Western mind is: analytical, discriminative, differential, inductive, individualistic, intellectual, objective, scientific, generalizing, conceptual, schematic, impersonal, legalistic, organizing, power-wielding, self-assertive, disposed to impose its will upon others, etc. Against these Western traits those of the East can be characterized as follows: synthetic, totalizing, integrative, nondiscriminative, deductive, nonsystematic, dogmatic, intuitive, (rather, affective), nondiscursive, subjective, spiritually individualistic and socially groupminded,1 etc.

When these characteristics of West and East are personally symbolized, I have to go to Lao-tse (fourth century B.C.), a great thinker in ancient China. I make him represent the East, and what he calls the multitudes may stand for the West. When I say "the multitudes" there is no intention on my part to assign the West in any derogatory sense to the role of Lao-tsean multitudes as described by the old philosopher.

Lao-tse portrays himself as resembling an idiot. He looks as if he does not know anything, is not affected by anything. He is practically of no use in this utilitarianistic world. He is almost expressionless. Yet there is something in him which makes him not quite like a specimen of an ignorant simpleton. He only outwardly resembles one.

The West, in contrast to this, has a pair of sharp, penetrating eyes, deep-set in the sockets, which survey the outside world1 Christians regard the church as the medium of salvation because it is the church that symbolizes Christ who is the savior. Christians are related to God not individually but through Christ, and Christ is the church and the church is the place where they gather to worship God and pray to him through Christ for salvation. In this respect Christians are group-minded while socially they espouse individualism.

6

as do those of an eagle soaring high in the sky. (In fact, the eagle is the national symbol of a certain Western power.) And then his high nose, his thin lips, and his general facial contour -all suggest a highly developed intellectuality and a readiness to act. This readiness is comparable to that of the lion. Indeed, the lion and the eagle are the symbols of the West.

Chuang-tze of the third century B.C. has the story of konton (hun-tun)} Chaos. His friends owed many of their achievements to Chaos and wished to repay him. They consulted together and came to a conclusion. They observed that Chaos had no sense organs by which to discriminate the outside world. One day they gave him the eyes, another day the nose, and in a week they accomplished the work of transforming him into a sensitive personality like themselves. While they were congratulating themselves on their success, Chaos died.

The East is Chaos and the West is the group of those grateful, well-meaning, but undiscriminating friends.

In many ways the East no doubt appears dumb and stupid, as Eastern people are not so discriminative and demonstrative and do not show so many visible, tangible marks of intelligence. They are chaotic and apparently indifferent. But they know that without this chaotic character of intelligence, their native intelligence itself may not be of much use in living together in the human way. The fragmentary individual members cannot work harmoniously and peacefully together unless they are referred to the infinite itself, which in all actuality underlies every one of the finite members. Intelligence belongs to the head and its work is more noticeable and would accomplish much, whereas Chaos remains silent and quiet behind all the superficial turbulence. Its real significance never comes out to become recognizable by the participants.

The scientifically minded West applies its intelligence to inventing all kinds of gadgets to elevate the standard of living and save itself from what it thinks to be unnecessary labor or drudgery. It thus tries hard to "develop" the natural resources it has access to. The East, on the other hand, does not mind engaging itself in menial and manual work of all kinds, it is apparently satisfied with the "undeveloped" state of civilization. It does not like to be machine-minded, to turn itself into a slave to the machine. This love of work is perhaps character-

7

istic of the East. The story of a farmer as told by Chuang-tze is highly significant and suggestive in many senses, though the incident is supposed to have taken place more than two thousand years ago in China.

Chuang-tze was one of the greatest philosophers in ancient China. He ought to be studied more than he is at present. The Chinese people are not so speculative as the Indian, and are apt to neglect their own thinkers. While Chuang-tze is very well known as the greatest stylist among Chinese literary men, his thoughts are not appreciated as they deserve. He was a fine collector or recorder of stories that were perhaps prevalent in his day. It is, however, likely that he also invented many tales to illustrate his views of life. Here is a story, which splendidly illustrates Chuang-tze's philosophy of work, of a farmer who refused to use the shadoof to raise water from his well.

"A farmer dug a well and was using the water for irrigating his farm. He used an ordinary bucket to draw water from the well, as most primitive people do. A passer-by, seeing this, asked the farmer why he did not use a shadoof for the purpose; it is a labor-saving device and can do more work than the primitive method. The farmer said, "I know it is labor-saving and it is for this very reason that I do not use the device. What I am afraid of is that the use of such a contrivance makes one machine-minded. Machine mindedness leads one to the habit of indolence and laziness."

Western people often wonder why the Chinese people have not developed many more sciences and mechanical contrivances. This is strange, they say, when the Chinese are noted for their discoveries and inventions such as the magnet, gunpowder, the wheel, paper, and other things. The principal reason is that the Chinese and other Asiatic peoples love life as it is lived and do not wish to turn it into a means of accomplishing something else, which would divert the course of living to quite a different channel. They like work for its own sake, though, objectively speaking, work means to accomplish something. But while working they enjoy the work and are not in a hurry to finish it. Mechanical devices are far more efficient and accomplish more. But the machine is impersonal and noncreative and has no meaning.

8

Mechanization means intellection, and as the intellect is primarily utilitarian there is no spiritual estheticism or ethical spirituality in the machine. The reason that induced Chuangtze's farmer not to be machine-minded lies here. The machine hurries one to finish the work and reach the objective for which it is made. The work or labor in itself has no value except as the means. That is to say, life here loses its creativity and turns into an instrument, man is now a goods-producing mechanism. Philosophers talk about the significance of the person; as we see now in our highly industrialized and mechanized age the machine is everything and man is almost entirely reduced to thralldom. This is, I think, what Chuang-tze was afraid of. Of course, we cannot turn the wheel of industrialism back to the primitive handicraft age. But it is well for us to be mindful of the significance of the hands and also of the evils attendant on the mechanization of modern life, which emphasizes the intellect too much at the expense of life as a whole.

So much for the East. Now a few words about the West.

Denis de Rougemont in his Man's Western Quest mentions "the person and the machine" as characterizing the two prominent features of Western culture. This is significant, because the person and the machine are contradictory concepts and the West struggles hard to achieve their reconciliation. I do not know whether Westerners are doing it consciously or unconsciously. I will just refer to the way in which these two heterogeneous ideas are working on the Western mind at present. It is to be remarked that the machine contrasts with Chuang-tze's philosophy of work or labor, and the Western ideas of individual freedom and personal responsibility run counter to the Eastern ideas of absolute freedom. I will not go into details. I will only try to summarize the contradictions the West is now facing and suffering under:

(1) The person and the machine involve a contradiction, and because of this contradiction the West is going through great psychological tension, which is manifested in various directions in its modern life.

(2) The person implies individuality, personal responsibility, while the machine is the product of intellection, abstraction, generalization, totalization, group living.

(3) Objectively or intellectually or speaking in the machine-

9

minded way, personal responsibility has no sense. Responsibility is logically related to freedom, and in logic there is no freedom, for everything is controlled by rigid rules of syllogism.

(4) Furthermore, man as a biological product is governed by biological laws. Heredity is fact and no personality can change it. I am born not of my own free will. Parents give birth to me not of their free will. Planned birth has no sense as a matter of fact.

(5) Freedom is another nonsensical idea. I am living socially, in a group, which limits me in all my movements, mental as well as physical. Even when I am alone I am not at all free. I have all kinds of impulses which are not always under my control. Some impulses carry me away in spite of myself. As long as we are living in this limited world, we can never talk about being free or doing as we desire. Even this desire is something which is not our own.

(6) The person may talk about freedom, yet the machine limits him in every way, for the talk does not go any further than itself. The Western man is from the beginning constrained, restrained, inhibited. His spontaneity is not at all his, but that of the machine. The machine has no creativity; it operates only so far or so much as something that is put into it makes possible. It never acts as "the person."

(7) The person is free only when he is not a person. He is free when he denies himself and is absorbed in the whole. To be more exact, he is free when he is himself and yet not himself. Unless one thoroughly understands this apparent contradiction, he is not qualified to talk about freedom or responsibility or spontaneity. For instance, the spontaneity Westerners, especially some analysts, speak about is no more and no less than childish or animal spontaneity, and not the spontaneity of the fully mature person.

(8) The machine, behaviorism, the conditioned reflex, Communism, artificial insemination, automation generally, vivisection, the H-bomb-they are, each and all, most intimately related, and form close-welded solid links of a logical chain.

(9) The West strives to square a circle. The East tries to equate a circle to the square. To Zen the circle is a circle, and the square is a square, and at the same time the square is a circle and the circle a square.

10

(10)Freedom is a subjective term and cannot be interpreted objectively. When we try, we are surely involved inextricably in contradictions. Therefore, I say that to talk about freedom in this objective world of limitations all around us is nonsense.

(11) In the West, "yes" is "yes" and "no" is "no"; "yes" can never be "no" or vice versa. The East makes "yes" slide over to "no" and "no" to "yes"; there is no hard and fast division between "yes" and "no." It is in the nature of life that it is so. It is only in logic that the division is ineradicable. Logic is human-made to assist in utilitarianistic activities.

(12) When the West comes to realize this fact, it invents such concepts known in physics as complementarity or the principle of uncertainty when it cannot explain away certain physical phenomena. However well it may succeed in creating concept after concept, it cannot circumvent facts of existence.

(13) Religion does not concern us here, but it may not be without interest to state the following: Christianity, which is the religion of the West, talks of Logos, Word, the flesh, and incarnation, and of tempestuous temporality. The religions of the East strive for excarnation, silence, absorption, eternal peace. To Zen incarnation is excarnation; silence roars like thunder; the Word is no-Word, the flesh is no-flesh; here-now equals emptiness (silnyatii) and infinity.

II. THE UNCONSCIOUS IN ZEN BUDDHISM

What I mean by "the unconscious" and what psychoanalysts mean by it may be different, and I have to explain my position. First, how do I approach the question of the unconscious? If such a term could be used, I would say that my "unconscious" is "metascientific" or "antescientific." You are all scientists and I am a Zen-man and my approach is "antescientific" -or even "antiscientific" sometimes, I am afraid. "Antescientific" may not be an appropriate term, but it seems to express what I wish it to mean. "Metascientific" may not be bad, either, for the Zen position develops after science or intellectualization has occupied for some time the whole field of human study; and Zen demands that before we give ourselves up unconditionally to the scientific sway over the whole field of human [...]

D. T. Suzuki, “Suzuki Zen,” and the American Reception of Zen Buddhism

by Carl T. Jackson

In: American Buddhism as a Way of Life, State University of New York Press, Albany, 2010, pp- 39-56.

Perhaps no single individual has had greater infl uence on the introduction

of an Asian religious tradition in America than Daisetz Teitaro

Suzuki, the Japanese Buddhist scholar whose very long life spanned

the period from the early years of Japan’s Meiji Restoration through

the American counterculture of the 1960s. Almost single-handedly, he

made Zen Buddhism, previously unknown to Americans, a focus of

interest. For prominent intellectuals, religionists, and creative artists as

diverse as Alan Watts, Erich Fromm, Thomas Merton, and John Cage,

as well as numerous American Zen enthusiasts, the Japanese scholar

was accepted as the fi nal authority on the Zen experience. Hailed in

1956 by historian Lynn White as a seminal intellectual fi gure whose

impact on future generations in the West would be remembered as

a watershed event, Suzuki has more recently come under sharp criticisms.

Scholars such as Bernard Faure and Robert Sharf charge that

in his desire to reach a Western audience, the Japanese writer greatly

altered Zen’s teachings, creating a Westernized “Suzuki Zen” that has

misrepresented the traditional Zen message.1 In the present essay an

attempt will be made to evaluate Suzuki’s career, presentation of Zen

to Americans, and the arguments of his critics. Special attention will

be focused upon the formative years he spent in America between

l897 and 1908, which, I suggest, exercised a decisive infl uence on his

success as a transmitter of Zen to the West.

Born in 1870, only three years after the Meiji Restoration

committed Japan to modernization, Teitaro Suzuki grew up in an

impoverished samurai family in Kanazawa on the western coast of

Japan. Suzuki’s father died when the boy was only six, leaving his

widow and fi ve children in dire economic circumstances. Despite

mounting diffi culties, young Suzuki continued his education until he

was seventeen, when the family’s fi nancial problems forced him to

drop out of school. Fortunately, his studies had given him suffi cient

acquaintance with English that he was able to fi nd employment as

an English teacher, a crucial linguistic acquisition in view of his

subsequent career as an interpreter of Zen to the West. However,

his mastery of the language must have remained very limited: He

recalled many years later that the English he had taught as a young

man “was very strange—so strange that later when I fi rst went

to America nobody understood anything I said.”2 Thanks to the

fi nancial backing of a brother, he was able to continue his education

at Waseda University and Tokyo’s Imperial University. In view of his

later international reputation as a scholar, it seems surprising that he

never completed his college studies; his only degree was an honorary

doctorate bestowed upon him at the age of sixty-three by Kyoto’s

Otani University.

Suzuki’s fi rst exposure to Zen Buddhism began quite early, as

his family observed Zen practices. Troubled by the early death of his

father and the family’s fi nancial problems, at one point he sought out

the priest of a small Rinzai Zen temple in his home city of Kanazawa.

Apparently the experience proved disappointing. “Like many Zen

priests in country temples in those days,” Suzuki would later recall,

“he did not know very much.”3 Soon after his move to Tokyo to continue

his studies at the Imperial University, he made the thirty-mile

trip to Kamakura, where he became a follower of Kosen Imagita, the

abbot of the important Rinzai Zen temple Engakuji; and, following

Kosen’s death, became a disciple of Kosen’s replacement, Shaku Soen

(also known in the West as Soyen Shaku and Shaku Soyen), who

would become a major infl uence on Suzuki’s life.4 During the later

nineteenth century Buddhism was going through a very diffi cult time

in Japan, assailed by sharp attacks on all sides while being forced to

accept the Meiji government’s expropriation of its income-producing

properties as the nation moved toward modernization. Caught

between Shintoists and nationalists on one side and Western-oriented

reformers on the other, Buddhist leaders responded by attempting

to redefi ne the Buddha’s message as a “new Buddhism,” emphasizing

a more universal, more scientifi c approach.5 Soen played a leadAmerican

ing role in the creation of this “new Buddhism,” participating in an

1890 conference of Buddhist leaders in Japan that sought to unify

the tradition’s different groups, which culminated in the compilation

of a document entitled “The Essentials of Buddhist Teachings—All

Sects.” As a disciple of Soen, Suzuki was clearly infl uenced by the

more cosmopolitan, universal conception of Buddhism embraced by

his teacher.

Though his writings would come to be regarded by most Americans

as the defi nitive statement of Zen Buddhism, it should be noted

that Suzuki remained a Buddhist layman always, never completing

the formal training necessary to become a Zen priest. He did pursue

Zen enlightenment for several years under the guidance of Soen and

claimed in his 1964 memoir that, just before his departure for America

in 1897, he had fi nally achieved a breakthrough.6 At this time Soen

gave his young disciple the name Daisetz, usually translated as “Great

Simplicity.” (Suzuki would later inform Western admirers that, in

fact, his name should be rendered as “Great Stupidity.”)

Meanwhile, developments in faraway America were about to

intrude, which would dramatically transform Suzuki’s life. The precipitating

event was the World Parliament of Religions, held in conjunction

with the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, where representatives

of the world’s major religions were invited to present their teachings.

An unprecedented gathering, the Parliament attracted a number of

Asian religious spokesmen, including the charismatic Swami Vivekananda,

who spoke for Hinduism at the congress, and the Singhalese

Anagarika Dharmapala, who championed Buddhism. Suzuki’s

spiritual mentor, Soen Shaku, attended as a member of the Japanese

Buddhist delegation, and his paper “The Law of Cause and Effect,

as Taught by Buddha” was read to the assembled audience.7 During

the Parliament’s sessions Soen became acquainted with Paul Carus,

the German American philosopher and editor of The Open Court, who

had developed an interest in Buddhism. They became friends. When

Carus subsequently prepared a compilation of the Buddha’s major

teachings, The Gospel of Buddhism, he sent a copy of the book to Soen

in Japan, who instructed his disciple to prepare a Japanese translation.

Carus then set out to translate the Tao Te Ching and asked

Soen to suggest someone who could assist him with the translations.

In response, Soen recommended Suzuki. Soen revealed to the Open

Court editor that his young protégé had been so “greatly inspired”

by Carus’s works that he strongly desired “to go abroad” to study

under Carus’s “personal guidance.”8 As a result, in 1897 at the age

of twenty-seven, Suzuki made the long journey to La Salle, Illinois,

then a small mining town outside Chicago, where he would remain

for the next eleven years.

If Soen Shaku served as Suzuki’s spiritual guide, Paul Carus

became his intellectual mentor, who in some ways infl uenced Suzuki’s

future career and writings even more profoundly than his Japanese

teacher. With a PhD from a German university, Carus had impressive

credentials to introduce his Japanese assistant to the profundities of

Western philosophy. In addition to his fairly extensive writings on

Buddhism and Asian thought, Carus served as editor of The Open

Court and The Monist, important philosophical journals at the turn of

the century. As Carus’s assistant, Suzuki performed a wide variety

of tasks, though he devoted most of his time to assisting Carus with

his Asian translations and carrying out editorial tasks connected

with the publication of The Open Court and The Monist. As a result

of these duties, his mastery of English rapidly improved—a fl uency

that would prove crucial in his future career as an interpreter of Zen

to the West.9

One of the two men’s earliest collaborations was a translation of

the Tao Te Ching. Suzuki laboriously translated word-for-word from

Chinese into English, which Carus then put into his own words, after

comparing his assistant’s version with available European translations.

In 1906 they prepared translations of two other Daoist works,

published as T’ai-Shang Kan-Ying P’ien and Yin Chin Wen, and then

undertook a translation of the Analects of Confucius. During these

years in La Salle Suzuki also translated a number of Carus’s other

writings into Japanese, including a pamphlet on Chinese philosophy

and several Buddhist short stories.10 Happily, Suzuki found time for

his own research and writing as well. Over his eleven years as Carus’s

assistant, the young Japanese published his fi rst scholarly reviews

and articles in English, including brief pieces on Confucius and Buddhism

in The Open Court and more extended essays on Asvaghosa, the

fi rst Buddhist Council, and early Chinese philosophy in The Monist.11

Finally, during these crucial formative years Suzuki also published

his fi rst two scholarly books in English, a translation of Asvaghosa’s

Discourse on the Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana (1900) and his

pioneering Outlines of Mahayana Buddhism (1907).

Suzuki’s extended sojourn in America was critical in shaping

his future career as a Zen transmitter to the West in several ways.

First and perhaps most important, it gave him the necessary skills—a

familiarity with Western philosophic conceptions, command of English,

and editorial experience—needed to reach Western readers. His

publication of some thirty books in English, which sold widely among

Western readers, emphasize how well he learned from the American

apprenticeship. Second, the eleven years under Carus’s tutelage

greatly furthered his education as a future scholar. With the rise of

research universities in the later nineteenth century, aspiring scholars

were forced to spend years in graduate school honing their research

and writing skills. Suzuki, who stopped short of a bachelor’s degree,

acquired the basic skills under Carus’s direction at the offi ce of the

Open Court Publishing Company. Trained in one of Germany’s ranking

universities and holding a doctorate in philosophy, Carus was

superbly equipped to initiate the young Japanese into the complexities

of Western scholarship and philosophical analysis.

The evidence of Carus’s infl uence on Suzuki may be detected

in the close similarities between the two men’s approach to scholarship.

Like Carus, Suzuki combined scholarship and advocacy, with

both men going well beyond disinterested analysis in their promotion

of personal philosophic and religious positions. Suzuki’s emphasis

on Buddhism’s compatibility with modern science closely paralleled

Carus’s insistence on the compatibility of science and religion. And it

is surely no coincidence that when Suzuki subsequently founded the

Eastern Buddhist as a vehicle for the promotion of Buddhist scholarship,

its format and contents mirrored that of The Open Court and The

Monist. Like Carus’s journals, the Eastern Buddhist offered its readers

popular as well as scholarly articles and emphasized both English

translations and philosophical expositions of Asian religious works.12

Without the extended apprenticeship under Carus, Suzuki might still

have made his mark as a Buddhist scholar; but it seems unlikely that

he would have become one of the twentieth century’s most infl uential

proponents of Asian thought.

Suzuki left America to return to Japan in 1908 at the age of thirtyeight,

where he would remain for the next forty years with the exception

of occasional trips abroad. During his return to Japan, he stopped

off in Europe for several months to copy Buddhist manuscripts at

the Bibliotheque Nationale and for two months at the Swedenborg

Society in London, where he undertook a Japanese translation of the

Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg’s Heaven and Hell. Though usually

passed over, Swedenborgianism obviously exerted considerable

attraction for Suzuki at this time, another indication perhaps of the

impact of his years with Carus. He seems to have become aware

of Swedenborg while assisting Carus through contact with Albert

Edmunds, a Swedenborgian and Buddhist scholar who frequently

contributed to The Open Court and The Monist. As is well known,

the Swedish philosopher’s thought was an important infl uence on

a number of nineteenth-century American thinkers, including Ralph

Waldo Emerson and the elder Henry James, father of psychologist

William James. At the Swedenborg Society’s invitation, Suzuki

returned to England a second time in 1912 to translate three other

Swedenborgian works into Japanese—The Divine Love and the Divine

Wisdom, The New Jerusalem, and The Divine Providence—and he subsequently

published an introduction to the Swedish mystic’s thought,

Swedenborugu, for Japanese readers. Perhaps because he subsequently

realized that many of his American and European readers would be

uneasy about Swedenborgianism, Suzuki almost never mentioned the

Swedish philosopher again in later years.13

Suzuki’s life and career may be usefully divided into three periods:

the years from 1870 to 1908, the time of preparation and his

American apprenticeship; the period from 1909 to 1949, which he

spent largely in Japan teaching and engaged in scholarship; and the

fi nal years from 1950 to 1966, when he resumed contact with the

West and achieved international fame. After his return to Japan in

1909, Suzuki fi lled a series of teaching positions before accepting a

1921 appointment as professor of Buddhist philosophy at Otani University,

where he would spend much of the remainder of his life. He

never allowed his teaching duties to divert him from scholarship, and

indeed, in the decades after his return to his homeland, published

volume after volume on Buddhism, Zen, and traditional Japanese

culture. With his wife Beatrice Erskine Lane, he also founded and

co-edited The Eastern Buddhist in 1921. The landmark volumes that

would establish his reputation and fame in the West now appeared

in rapid succession: the fi rst volume of his Essays in Zen Buddhism

(1927), his Studies in the Lankavatara Sutra (1930), and the second and

third volumes of the Essays in Zen Buddhism (1933 and 1934), followed

by The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk (1934), An Introduction to Zen

Buddhism (1934), the Manual of Zen Buddhism (1935), and Zen Buddhism

and Its Infl uence on Japanese Culture (1938). Composed in English,

these volumes once again demonstrated his acquired fl uency in the

language. The works became bibles to eager American Zen students

after World War II.14

During the interwar years Suzuki for the most part lived the

quiet life of a scholar. Thanks to his books and rising international

reputation, he played host to a steady stream of Western visitors interested

in Buddhism, including Charles Eliot, James Bissett Pratt, L.

Adams Beck, Dwight Goddard, Kenneth Saunders, and Ruth Fuller.

In 1936 he returned to the West for the fi rst time in over two decades

to participate in a World Congress of Faiths organized by Sir Francis

Younghusband in London. During this visit, Suzuki met and entered

into a lifelong friendship with Christmas Humphreys, who became

one of the West’s most active promoters of Buddhism.15 While abroad

the Japanese scholar lectured at universities in Great Britain and the

United States before returning home to Japan in 1937, as the dark

clouds of World War II were rising. Though his books were attracting

increasing attention in the West, the numbing events of World War II

would delay Suzuki’s wider Western impact until after 1945.

The coming of World War II and the ascendancy of militarism

in Japan placed Suzuki in a precarious position. The fact that he

had spent over a decade in the United States, married an American

woman, and published extensively in a Western language, undoubtedly

raised the suspicions of Japan’s militarists. At a time of extreme

nationalist feeling when all things Western were frowned upon, it

is not surprising that his publications in English largely ceased after

1938, to be replaced by a fl ood of Japanese publications. Led by Brian

Victoria, some recent scholars have raised disturbing questions

concerning the degree to which Suzuki, as well as members of the

so-called Kyoto School led by Suzuki’s close friend and philosopher

Nishida Kitarø, supported the Japanese war effort during World War

II. Critics note that Suzuki’s spiritual mentor Soen Shaku had hailed

Japanese victories in the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars; that,

beginning in 1935, Suzuki’s writings increasingly emphasized nihonjinron,

the innate spirituality and distinctiveness of Japanese culture;

and that during the war years and after Suzuki never denounced

Japan’s attacks on its neighbors. Meanwhile, in such writings as Zen

Buddhism and Its Infl uence on Japanese Culture, published in 1938, he

emphasized the close connection between Zen and the warrior ethic

of Bushido, which critics have pointed to as the basis for “war Zen”

or “soldier Zen.” Suzuki wrote: “The soldierly quality, with its mysticism

and aloofness from world affairs, appeals to the will-power. Zen

in this respect walks hand in hand with the spirit of Bushido.”16

While critics such as Victoria have clearly raised important

questions about Suzuki’s position, defenders have stepped forward

to counter the charges. Drawing upon materials not included in the

Japanese scholar’s Complete Works, Kirita Kiyohide argues that Suzuki

never accepted the concept of an absolute state and early in his career

questioned the role of the imperial family in magazine articles and

personal correspondence. According to Kirita, Suzuki clearly disapproved

of the recklessness and parochialism of the militarists and

always remained isolated from Japanese politics, with no connection

to the militarists. Moreover, in the years after the war he had urged

his Japanese compatriots to reject state Shintoism and worship of the

state. Revisiting the issue in 2001 with a focus on the ethical implications

of the Buddhist response to the war, Christopher Ives argues that

the critics have not and cannot demonstrate a real linkage between

writings emphasizing what he calls the “Zen-bushido connection” and

the actions of Japanese soldiers and kamikaze pilots in the actual war

zone. Ives concludes that the fl owering of Japanese militarism before

and during the war years had complex, multiple roots.17

What conclusion may be drawn? At the very least it seems clear

that Suzuki chose to go along with, or at least not to resist, his nation’s

war efforts. This hardly seems surprising for the time: Most intellectuals

in Western as well as Asian societies—with some notable exceptions—

supported the war aims of their respective governments. The

tendency to link his views to those of the Kyoto School philosophers

seems overextended; though a close friend of Nishida’s, he cannot be

held responsible for his friend’s or the other members of the Kyoto

School’s views. And the fact that he emphasized the Zen-Bushido

connection in some passages of his scholarly writings hardly qualifi es

him as a fl ag-waving militarist or a major contributor to the Japanese

war effort. At most, his scholarly writings would have provided very

limited encouragement to the Japanese military, who would rarely

have read his works. In retrospect, one might wish that Suzuki had

resisted the militarists; instead, he chose to wait out the war, retreating

to his study to concentrate upon scholarship and writing.

It could be argued that Suzuki’s return to the United States in

1951 as a lecturer on Buddhist philosophy at Columbia University

ignited the American Zen boom of the 1950s and 1960s. Amazingly,

the venerable Japanese author was already eighty-one when he

began his lectures at Columbia. Stimulated by the Beat movement’s

celebration of Zen—led by Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and Gary

Snyder—young people across the country began to turn to Zen Buddhism

and to Suzuki’s books as never before. Overnight, the Japanese

octogenarian found himself a celebrity who was constantly sought

out by curiosity-seekers as well as by prominent writers, theologians,

and psychologists. Born fi ve years after the close of the American

Civil War, astonishingly, Suzuki became something of a spiritual hero

to many young people in the 1950s and 1960s. Winthrop Sargeant’s

admiring profi le in The New Yorker in 1957 suggests Suzuki’s iconic

status. Describing the unique impression made by the Japanese

scholar, who regularly lectured on Friday afternoons at Columbia,

Sargeant wrote:

Despite his great antiquity—he is eighty-seven—he has the

slim, restless fi gure of a man a quarter of his age. He is

clean-shaven, his hair is closely clipped, and he is almost

invariably dressed in the neat American sports jacket and

slacks that might be worn by any Columbia undergraduate.

The only thing about him that suggests philosophical

grandeur is a pair of ferocious eyebrows, which project

from his forehead like the eyebrows of the angry demons

who guard the entrances of Buddhist temples in Japan.18

Over the following years Suzuki attracted a distinguished audience

to his Columbia lectures, where he continued to teach until 1957.

At one time or another his listeners included neo-Freudian psychologists

Erich Fromm and Karen Horney, modernist composer John

Cage, and philosopher Huston Smith, among others. Philip Kapleau,

who subsequently underwent Zen training at a temple in Japan and

became one of America’s best-known, native-born teachers of Zen,

also attended. While Suzuki’s lectures charmed those able to attend

his classes, most enthusiasts had to rely on his books for acquaintance

with Zen. Opportunely, the 1950s paperback revolution occurred at

just the right time, making his books available to a popular audience

at very low cost. Though he also wrote extensively on Mahayana

and Shin Buddhism, the works that captured the American public’s

imagination were unquestionably the books on Zen. Serious students

perused the three-volume Essays in Zen Buddhism, but most readers

undoubtedly preferred his more popular expositions such as An

Introduction to Zen Buddhism, a concise summary of barely one hundred

pages. Other works that attracted a wide audience included his

Manual of Zen Buddhism and Zen and Japanese Culture. Many readers

(including the author) gained their fi rst exposure to Suzuki’s writings

through such popular anthologies as William Barrett’s Zen Buddhism

(1956) and Bernard Phillips’s The Essentials of Zen (1962), which offered

selections from the Japanese Zennist’s vast body of writings.19

If Suzuki presented the essentials of Zen Buddhism with an

authority and lucidity unmatched by any other scholar in his time,

it is clear that he also brought his own special understanding and

interpretation to the task, which later commentators began to refer

to as “Suzuki Zen.” Several elements may be said to distinguish his

presentation of Zen. First off, the emphasis throughout his writings

refl ected his Rinzai Zen background and preferences. Reading Suzuki,

one might never have realized that, historically, Zen in Japan included

not only the Rinzai school but also Soto and Obaku Zen. Rinzai’s

emphasis upon the role of riddles or koans and the sudden achievement

of spiritual enlightenment or satori contrast sharply with Soto

Zen’s emphasis upon prolonged sitting or zazen and the belief that

illumination develops gradually. Thanks to Suzuki’s infl uence, Zen

for most Americans was Rinzai Zen. The Rinzai emphasis on nonsensical

answers and paradox obviously appealed to many Westerners

in the post-World War II era who were also drawn to existentialism

and Freudianism. (If the Rinzai tradition dominated American Zen in

the 1950s and 1960s, in recent decades Soto Zen has achieved a growing

American acceptance, led by such Japanese teachers as Shunryu

Suzuki, founder of the San Francisco Zen Center, and Hakuyu Taizan

Maezumi, who founded the Zen Center of Los Angeles.)

Secondly, in his presentation of Zen, Suzuki emphasized inner

experience rather than rituals, doctrines, or institutional practices.

Writing in An Introduction to Zen Buddhism, Suzuki insisted that “Personal

experience, therefore, is everything in Zen. No ideas are intelligible

to those who have no backing of experience.” In this respect, he

distanced himself from the institutionalized practices of Zen temples

in Japan. Ultimately, he viewed the inner Zen experience as universal,

as the spirit or essence underpinning all religions. “Zen professes

itself to be the spirit of Buddhism, but in fact it is the spirit of all

religions and philosophies,” he wrote.20 When he did bother to notice

Zen’s institutional form, he criticized its narrowness and sectarianism.

By downplaying the rituals of institutional Zen while stressing Zen’s

emphasis on experience and its universality, he obviously widened

Zen’s appeal for Americans.

Thirdly, as presented in Suzuki’s writings, Zen offered an activist

viewpoint that called for engagement with the world, again an

emphasis largely missing in the traditional Zen of Japan. He found

the rationale for such an interpretation in the Zen monastery rule “No

work, no eating,” noting that the daily life of a Zen monk required

a continuous round of cleaning, cooking, and farming. At one point

he even referred to the Zen ideal as a “gospel of work.”21 On another

occasion he went so far as to describe the Zen approach as a “radical

empiricism,” an interesting choice of words that linked the ancient

Japanese tradition to the modern philosophical positions of American

pragmatists William James and John Dewey. If the ultimate Zen

goal remained individual realization, “Suzuki Zen” did not ignore the

responsibility for social action. Writing in 1951, the Japanese scholar

suggested that Zen was as “socially-minded” as “any other religion,”

though its spirit had been “manifested differently.” He proclaimed

that the Zen monastery was not meant “to be a hiding place from

the worries of the world.”22

Finally, despite his insistence on Zen’s irrationality and nonlogical

nature, “Suzuki Zen” presented the Zen experience as a coherent

and all-embracing perspective on reality—in effect, as a philosophy. I

say this while recognizing that throughout his writings he again and

again asserted that Zen Buddhism was neither a philosophy nor a

religion and while acknowledging his repeated objections to all efforts

to present the Zen experience as an intellectual system. However,

even as he denounced philosophizing as a futile exercise, his books

present a philosophic interpretation of Zen. (There is an obvious

analogy to Freud: though the founder of psychoanalysis emphasized

the role of the irrational throughout his writings, he was surely no

irrationalist.) As a Zen Buddhist, Suzuki must have appreciated the

paradox involved. In writing so many books attempting to explain

Zen, he obviously violated one of Zen’s most fundamental assumptions;

and, indeed, he sometimes described his numerous publications

as “my sins.” Though steadfastly denying that he was a philosopher,

his writings on Zen clearly offer a philosophic presentation of Zen.23

Knowing his background, one should not be surprised by this philosophic

bent. After all, his American mentor had been trained as a

philosopher, while his close friend Nishida Kitarø ranks as Japan’s

greatest twentieth-century philosopher. Signifi cantly, many of Suzuki’s

articles appeared in important philosophical journals such as The

Open Court, The Monist, and Philosophy East and West.

The fi nal years of Suzuki’s life from 1950 until his death in 1966

were years of astonishing activity and widening international fame. In

addition to his high-profi le lectures at Columbia University, he became

a regular participant at the Eranos Conferences in Ascona, Switzerland,

which brought together some of the world’s most eminent scholars,

theologians, and psychologists. He also took part in the Third

and Fourth East-West Philosophers’ Conferences held in Hawai’i in

1959 and 1964 and in a 1957 conference on Zen and psychoanalysis

organized by Erich Fromm in Cuernavaca, Mexico. In his eighties, he

continued to publish new works almost yearly, including his Studies

in Zen (1955), Zen and Japanese Buddhism (1958), Mysticism: Christian

and Buddhist (1957), and Zen Buddhism and Psychoanalysis (1960), the

latter two revealing his desire to link Buddhist tradition and Western

thought. Though perhaps a surprising choice for an elderly Japanese

man in his eighties, during these later years New York City became

his home away from home. Curiously for such a noisy and bustling

center, one of the city’s attractions was that it provided a quiet refuge

where he could do his work; in Japan he was constantly besieged by

a stream of visitors.

A full examination of Suzuki’s amazingly prolifi c career as a

writer and scholar would require many more pages than are available

here. However, three generalizations concerning his Zen writings

and their role as a source of the modern West’s understanding of Zen

stand out. First, though almost automatically identifi ed with Zen, it is

striking that he did not really begin to focus on Zen Buddhism until

the 1927 appearance of the fi rst volume of his Essays in Zen Buddhism,

when he was already fi fty-seven years old. (He did publish a brief,

unnoticed piece on Zen in the 1906–1907 volume of the Journal of the

Pali Text Society.) In the West at least the tendency has been to ignore

his extensive non-Zen writings. In fact, nearly all of his early publications,

including numerous contributions in The Open Court and The

Monist and his fi rst scholarly book, Outlines of Mahayana Buddhism,

focused upon Mahayana Buddhism and Buddhism generally—not on

Zen Buddhism. It may be that in his desire to reach a wider Western

audience he found it best in the beginning to emphasize Buddhism’s

broad message rather than its sectarian differences. In later years

he paid increasing attention to Jodo Shinshu or Shin Buddhism, an

interest encouraged by his long association with Otani University, a

Jodo Shinshu institution.24 To put it differently, early and late Suzuki

focused much attention on both Mahayana and Shin Buddhism; Zen

Buddhism was never his sole interest.

Secondly, despite his Western reputation as a great scholar

whose publications offer the authoritative presentation of Zen Buddhism,

his writings clearly reveal a spirit of advocacy. Infl uenced by

his teacher Shaku Soen as well as Meiji-era Buddhist thinking, he

came to his studies of Buddhism not as a disinterested scholar, but

as a believing Buddhist committed to the defense and exposition of

the Buddha’s way as a spiritual choice. Though he certainly deserves

his reputation as a great scholar whose translations and scholarly

publications continue to provide illumination, we a must always

remember that the ultimate goal of his scholarship was not knowledge

for knowledge’s sake, but the presentation of Buddhism and Zen

Buddhism as religious choices. This stance may, of course, be viewed

as positive, depending upon one’s perspective. If his personal Buddhist

commitments may be cited by critics as a distorting infl uence,

the fact that he was a practicing Buddhist would only have increased

the authority of his writings for others.

Thirdly, it is clear that much of Suzuki’s success in the West

stemmed from his ability to simplify Zen for a general audience. In

the best sense of the word, he was a popularizer. In his writings he

regularly passed over complexities, eliminated technical terms, and

offered well-chosen stories to make his points. By largely ignoring

the differences in the historical forms of Buddhism while emphasizing

its core teaching, he made it much easier for Westerners to

understand and embrace the Buddhist message. And by blurring

the differences between Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism and

between the Ch’an Buddhism of China and the Zen Buddhism of

Japan, he also made Buddhism seem much more unifi ed and more

universal than the facts justified.

In concluding, we may turn fi nally to the contemporary scholarly

evaluation of Suzuki’s published works on Zen Buddhism. Hailed

by a generation of Western readers as the world’s greatest authority,

what are contemporary scholars saying? The answer seems to be that,

while his works are still frequently cited, his interpretation of Zen has

come under severe attack. While the intensity of this criticism has

greatly increased in recent years, it should be noted that the questioning

goes back at least to the 1950s. One of the earliest critics, Chinese

historian Hu Shih charged in 1953 that by ignoring Zen’s historical

roots, Suzuki was greatly distorting its lineage and teachings. Objecting

to Suzuki’s contention in the second volume of his Essays in Zen

Buddhism that Zen was “above space-time relations” and “even above

historical facts,” Hu Shih insisted on the importance of recognizing

Zen’s roots in the Ch’an Buddhism of China. Obviously stung by Hu

Shih’s attack, Suzuki responded with uncharacteristic harshness that

Zen needed to be “understood from the inside” rather than from the

outside as in Hu Shih’s approach.25 In the 1960s other critics, led by

R. J. Zwi Werblowsky and Ernst Benz, complained that Suzuki’s writings

were diluting and psychologizing Zen’s teachings, encouraging

a widespread misunderstanding among Westerners.26

The criticisms have greatly increased since the 1980s as a revisionist

view has become dominant. The emerging consensus seems to be

that the Zen Buddhism that D. T. Suzuki presented in his many books

represents a modern, Western-infl uenced Zen that broke sharply with

the traditional Zen of Japan. Presenting arguments too complex to

summarize here, the two leaders in this reevaluation, Bernard Faure

and Robert Sharf, have produced meticulously documented critiques

that argue that the Japanese Zennist has, in effect, reconceptualized

Zen, greatly distorting its traditional teachings. In his Chan Insights and

Oversights, Faure suggests that, like his close friend Nishida Kitarø,

Suzuki had both adopted and reversed Western Orientalist assumptions.

In their description of Zen they had effectively “inverted” the

image created by earlier Christian missionaries, replacing the hostile

Christian view by an idealized image of Japanese culture and Zen.

Insisting that the importance of Suzuki’s work has been greatly exaggerated,

Faure attacks Suzuki’s Rinzai sectarianism, his tendency to

emphasize mysticism as a common foundation for Zen and Christianity,

and his nativist tendencies. Faure concludes that Suzuki’s interpretation

was very much colored by his isolation from his own people

and marginality in Japanese culture. Leaving Japan for the United

States as a young man, his thought revealed “his confrontation with

Western values,” including Christianity, psychoanalysis, and existentialism—

all of which had profoundly distorted his Zen view.27

In his important essay, “The Zen of Japanese Nationalism,” published

in the History of Religions in the same year as Faure’s Chan

Buddhism, Robert Sharf added his voice to those critical of Suzuki’s

reinterpretation of Zen. Beginning with the infl uence of Meiji-era

Buddhism, Sharf documents the degree to which Suzuki’s view of

Zen was transformed by his personal experiences. The most important

infl uences were his early years in the United States, the infl uence

of the Western conception of “direct” experience through William

James, and his attraction to nativist and nihonjinron ideas of Japanese

“innate spirituality.” Like Faure, Sharf concludes that the common

feature of “virtually all” Japanese writers responsible for the modern

Western interest in Zen, and certainly Suzuki, was their “relatively

marginal status within the Japanese Zen establishment.”28

Perhaps the criticisms have now gone far enough, with a need