ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen

főoldal

« vissza a Terebess

Online nyitólapjára

丹羽 (瑞岳) 廉芳

Niwa (Zuigaku) Rempō (1905-1993)

![]()

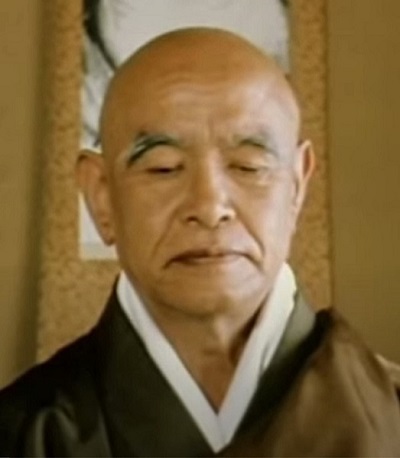

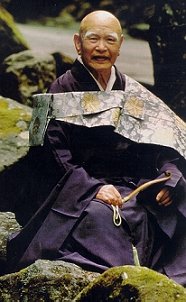

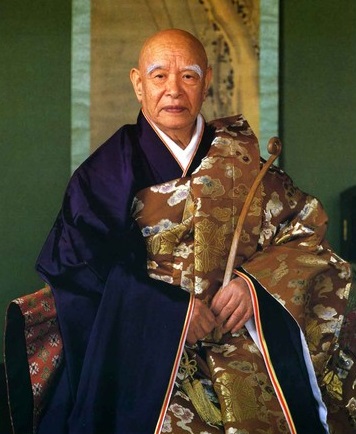

In these portrait photos Niwa zenji wears an ōkuwara (大掛絡), a sort of big rakusu, another version of the kesa, hanging over his left shoulder.

PROFILE & TALK BY REMPO NIWA ZENJI

https://www.treeleaf.org/forums/showthread.php?10520-site-about-the-abbots-of-Eiheiji

By all accounts, Nishijima Roshi's Teacher, Zuigaku Rempo Niwa Zenji, was a sweet, tender and caring man. Niwa Zenji was the Seventy-Seventh Abbot of Eiheiji Monastery, the temple of Dogen Zenji. (In fact, the honorific “Zenji” is granted in the Soto School to those few who have been the Abbots of Eiheiji or Sojiji, the two senior monasteries of Soto Zen in Japan). Niwa Zenji subsequently served as the Chief Abbot of the Soto School (Kancho), the official head of the sect, and was granted by the Japanese Emperor the honorific title “Jikô Enkai Zenji” (“Great Zen Master of Compassionate Light, Ocean of Plenitude”; 慈光圓海禅師). A Grand Master of “Baika” Buddhist hymn singing and a recognized master of calligraphy, many of his brushed works appear under pen names such as 老梅 Rōbai (“the old plum tree”), 梅庵 Baian (“the plum tree hermitage”), 雪梅 Setsubai (“Snow Plum”) and others.

Niwa Zenji was born on February 23rd, 1905, the sixth of ten children of Kataro (father) and Mura (mother) Shionoya in Uryuno Village, Kimizawa County, Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan. In 1916, by his own request at only the tender age of 12, a “Homeleaving” Priest Ordination was performed by his uncle, Niwa Butsuan Roshi (丹羽佛庵老師) of the Tokei-in Temple (洞慶院) in Shizuoka. Niwa Zenji would remain a priest for the next 77 years, until his death. He recounted the story in his memoirs:At the age of twelve, my grandfather's 7th Annual Memorial Service was conducted by Rev. Kagashima Sojun of the Jotokuin and the priest who would eventually become my master, Rev. Niwa Butsuan. My Master, Butsuan, was the second son of my grandfather Kishiro, and so my father Kataro's first younger brother. Butsuan had received Homeleaving Ordination under Rev. Niwa Bukkan of the Ryuunin, the Dragon Cloud Temple, in what is now Shimizu City in Shizuoka, and Butsuan was then the Head Priest of the Tokei-in Temple in Shizuoka.

I recall that the purple color of the Kesa robe my Master wore at the Memorial Service was wonderful, and enchanted me and made me truly want to wear such a Kesa. I thought, “I want to become a Buddhist Priest too!” That evening, when all my relatives were gathered around the cooking hearth, I came right out and said so. My father agreed, saying, "I see. Because there are so many children, Ren, shall we ask Uncle's temple to do this for us?" But my mother, Mura, spoke against it, pleading, “Even before this boy had entered primary school, he already was helping me in gathering mulberries for the silkworms, making Udon noodles, carrying rice to the miller. We have ten children, but I just can't be apart from this one.”

But in the end, after being persuaded by my relatives, my mother reluctantly agreed.

My Master, Butsuan, welcomed it and declared, “This is to be celebrated, even our Founder Dogen Zenji was only 14 years old when he was Ordained!” In my childish heart, I thought, “Wow, I am going to become a monk at about the same age as Dogen!”, and I still remember how excited I was as if it were just yesterday.

Following that day, I got my wicker bags together, and I set out the next afternoon for Shizuoka. It was 1916, April 8th, and I was in the 6th grade of elementary school.~ From Niwa Rempo's Book, 「The Plum Flower Opens – My Life Until Now 梅華開-わが半生」 ~

Upon Ordination, he received the monk's name Zuigaku Rempô, meaning “Auspicious Mountain-Peak, Pure Fragrance” and in 1926, at age 22, received Dharma Transmission from Niwa Butsuan Roshi. Soon after, he began study at Tokyo Imperial University (now The University of Tokyo) majoring in Indian Philosophy, and following graduation, returned to Toukei-in Temple to serve as the Kansu (監寺) temple supervisor. In October 1933, at age 29, he completed his time in the Monk's Hall at Eiheiji, and returned to the Tokei-in.

The Tôkei-in is considered the root temple of our Lineage through Niwa Zenji, Butsuan Roshi and earlier Ancestors. It has been a Zen temple of the Soto school since the 15th Century, and is located in the beautiful green hills near to the town of Shizuoka (180 km to the west of Tokyo) on Mt. Kuzumi. In fact, Niwa Zenji's connection to Tokei-in continued throughout his life, right until his eventual death in one of its pavillions. In April 1936, at age 32, Niwa Zenji was officially appointed as Lecturing Instructor for Soto Zen Doctrine (宗乗担当講師) accompanying the opening of the Monk's Training Hall at Tokei-in. The opening of the Training Hall was an important event for the temple. Although officially ranked as a “Daijuu Zenrin,” one of the “ten great monasteries” of Soto Zen in Japan, and a “Senmon Sodo,” a temple specifically designated for the training of novice priests, the number of Priests in residence has never been great and the size of the temple always modest. Its fortunes have waxed and waned through history as well, and Niwa Zenji worked very hard during his life for its revival and present health. The opening of the Monk's Training Hall was an important step in that revival.

Niwa Zenji's name only became “Niwa” some years after he first became a priest. In December 1939, at age 35, Zenji was registered in his uncle and Master's Niwa family registry, as an adopted child, changing his family surname from “Shionoya” to “Niwa.” He explained:Following in the footsteps of my Master, my surname was changed from Shionoya to Niwa in December, 1939. Eshu (慧宗), my younger brother apprentice, left for the war, saying “If I die in the war, I would like to come home bearing the Niwa name”. Our Master said, “Since you [Eshu] are my latest apprentice, it does not make sense for me to include you alone as a Niwa. First, I will register Ren, and then include Eshu under Ren's registry”. In this way, the Master registered us. Eshu was made the grandson.

Looking at it from the standpoint of our Master, he was getting on in years, and even if Eshu returned from the war unhurt, the Master thought that he himself might already no longer be living. So, I think at that time he felt grandmotherly concern that I be there in the future to look after things.

However, Eshu did not return alive.

He ended up being sacrificed in a meaningless war.In his memoirs, Niwa Zenji recounts other hardships encountered during the war, including Tokei-in's housing great numbers of school children as refugees during the worst days of the American bombing.

In 1960, at age 56, Niwa Zenji was appointed the Director (Kan-In) of the Eiheiji Betsuin Training Temple, Eiheiji Monastery's branch in Tokyo, where he would remain for many years. It was there that he would eventually Ordain Gudo Nishijima. Nishijima Roshi, who was a family and working man, recalled how Niwa Zenji was willing to encourage and nurture Soto Zen Priests who would combine priesthood with lives primarily out in the world.By the time I was 16 years old, I had already begun to have much interest in Master Dogen's Buddhist thought, especially in Shobogenzo, which I would then go on to study for many decades. Eventually, I began to translate Master Dogen's Shobogenzo from the old Japanese language into modern Japanese. This was finally published as "Gendaigoyaku Shobogenzo” or “Shobogenzo in Modern Japanese," and at that same time, I began a series of lectures on Shobogenzo at several places including the Young Men's Buddhist Association of Tokyo Imperial University [now Tokyo University] and elsewhere.

At that time I made up my mind to become a Buddhist monk in the Soto Sect but, unfortunately, as a working man supporting a wife and child, I did not feel I could abandon them to undertake monk's training for long years. I hoped to find a way to combine priesthood with my other responsibilities. Furthermore, I felt very keenly that Master Dogen's Teaching should be available to people out in the world, and not only to those leading a monastic life. Therefore, it was necessary for me to find a Buddhist Master who would permit me to become a Buddhist monk under such circumstances. Fortunately, I recalled the name of Abbot Rempo Niwa, who happened to have graduated years earlier from the same school as me, the Shizuoka Governmental High School, and I asked to visit.

I visited the Master at the Tokyo Branch of Eiheiji, and I asked to become a Buddhist monk by him. I explained my situation and my hope to unify priesthood with family, work and a beneficial life in the world. Upon hearing my story, I was joyously permitted to become a monk by him. When he listened to my proposal and wish for becoming a Buddhist monk, I noticed that he shed a little bit of tears in his eyes, and he had to wipe them. So I felt that it might also be a joyful fact for him to have me as his monk, and that he understood very well. I received Shukke Tokudo Ordination in December, 1973, next Hossen Shiki and then Dharma Transmission in 1977. From that time, Master Niwa was very kind and always careful for me not to meet any kind of difficulty in my secular job and responsibilities while continuing my Buddhist activities.

After having the ceremony to become a Buddhist monk formally, I began to teach people Zazen and Shobogenzo, even in the Tokyo Eiheiji Branch too. And because it was held every Thursday afternoon, I finished my job a little earlier than usual, and went to the temple wearing a common business suit as an ordinary salaried man. Therefore, taking off my coat, and wearing the Kashaya [Buddhist Kesa robe] over a white dress shirt, I gave my Buddhist lecture in the temple. However, some Buddhist monks in the temple thought that it was very inadequate for a Buddhist monk to hold a Buddhist lecture wearing a Kashaya over a western white dress shirt, and so they asked Master Niwa to stop such an informal style in the temple. To this Master Rempo Niwa said, "It is not so bad, because he seems to be like an Indian monk," and so I could continue my Buddhist lecture in the temple without changing my style.

Eventually I began to lead Sesshin in the temple at the end of Summer, and at that time, of course, I wore the formal black clothes of the Buddhist monk. Also, at The Buddhist Association of Tokyo University, and so forth, I used the formal Buddhist clothes as a monk without fail. Then I began to lead Sesshin in Master Rempo Niwa's temple called Tokei-in. I led Sesshin at Tokei-in six times a year, for Japanese participants sometimes and for foreign participants in English sometimes. Our relationship continued even after Master Niwa became the 77th Abbot of Eihei-ji from April 1985 to September 1993, right until his death.

I was taught so much by the Abbot Rempo Niwa about how I shall live as a human being. The Abbot Rempo Niwa was a very sensitive and generous person. … When I visited him in his private room, he sometimes served me a cup of green tea that he himself prepared. At that time, even when he did not teach me especially with words, I was able to gain so much knowledge simply by watching his behavior. He showed me at that time so many teachings.On June 25, 1976, at age 72, Niwa Zenji was elected Assistant Abbot of Eiheiji Head Monastery, and in January 1985, at the age of 81, he became the 77th Abbot of Eiheiji. In that role, and concerned for the internationalization of Soto Zen abroad, Niwa Zenji made overseas trips to China, Europe, America and elsewhere, and oversaw the founding of an International Division at Eiheiji. Niwa Zenji gave Dharma Transmission to Master Nishijima with knowledge and encouragement of his work in Japan with both Japanese and foreigners and, among his other Dharma Heirs, bestowed Dharma Transmission on students of Taizen Deshimaru, the Teacher so influential in the propagation of Soto Teachings in Europe. On February 22, 1992, Niwa Zenji was elected the Chief Abbot of the Soto Sect, and thus formal head of the Sect.

On September 7, 1993, Niwa Zenji passed away in the Abbot's Residence known as the Plum Viewing Pavillion at the Tokei-in Temple in Shizuoka. He was 89 years old.

ON ZEN PRACTICE

(Adapted from a 1977 interview on the NHK TV series “The Religion Hour”)

The Buddha Way is to probe and see through this self, and the basis for doing so is to Practice through this human body which our self possesses. Thus, it is most vital to make effort oneself in the manner of Shakyamuni Buddha. … In the Genjo Koan, Master Dogen speaks of “To learn the self”:

To learn Buddhism is to learn ourself. To learn ourself is to forget ourself. To forget ourself is to be experienced by millions of things and phenomena. To be experienced by millions of things and phenomena is to let our own body and mind, and the body and mind of the external world, fall away. Then we can forget the mental trace of realization, and show the real signs of forgotten realization continually, moment by moment.

What is this word “self” of that phrase “to learn Buddhism is to learn ourself?” This “self” means our ordinary way of seeing things, our small self in our usual thinking. However, if we probe a little deeper beyond the “self” of our ordinary thinking, there is to be found a higher degree of self that presents a limitless interpenetration of wisdom and benevolence. If we are speaking of the ordinary self, we may come to think of just our small, deluded self as our self. But in reality, the self is noble, and if we polish it, limitless light will shine forth therefrom. Master Dogen looked at each individual in such way.

***

Master Dogen taught that we beings who are living life, all the many beings and not just human beings, have such nobility beyond what can be spoken. But that fact is hidden because of the many attachments, desires and other blindnesses whereby we are limited to seeing just a small, ugly little “me.” However, just within reach is something great, something just ahead beyond even measure of great or small, which is the self.

… If we polish the self with such purpose, the original light will shine. This is the Buddhist Way; this is our rescue.

***

Dogen's words in the Genjo Koan, “to forget ourself”, mean to explore through Practice just what is this self – and that Practice is Zazen. By Zazen, this self just naturally ……… [silence]. And to forget in such a way means to enter the world that leaps beyond good and bad. For example, forgetting even that our “self” has the bottomless nobility that I first mentioned, and also forgetting how we fall into the clouds of greed, desire, anger and like folly, one thus leaps beyond both good and bad, which is the meaning of “to forget ourself.”

***

Dogen's Teacher, Nyojo Zenji, spoke of the sense of small self as “jinga,” personhood. The small self is known by a view of “personhood” or “individual selfhood,” and with this view something otherwise noble is made small and suffers. When we leave behind and transcend that small selfhood, we find what is real according to Nyojo Zenji.

The words of the Genjo Koan, “to be experienced by millions of things and phenomena” then means to leave behind this small self, and to find what I first spoke of, namely that there is a polishing which brings out an interpenetrating, bottomless light of wisdom and benevolence. This is just Bodhi (enlightenment, being awakened to the true nature of things), and we find such for ourself right here and thereupon finally let such go. At that moment of letting go there is “being experienced by millions of things and phenomena.” In other words, in so forgetting the self, we and the universe become one. The Universe is Reality, and Reality and our self become one. And so, there is not separation of self and other, this and that. There is you, there is me. Self is and other is. Yet this is no separation between self and other, and to attain such a pure and expansive heart is “to be experienced by millions of things and phenomena.”

***

In Shakyamuni's Teachings there is found the words “Turning the self, Turning the Dharma.” “Turning the self” means that one's little self turns the Dharma, and that when one's sense of self is strong, the Dharma is weak. On the other hand, when the Dharma turns the self, then the Dharma is strong and the little self is weak. By this strength, heaven and earth become full of one or the other. By this weakness, there is not left room for even one hair. So, when the little self turns the Dharma, the self is strong and the Dharma is weak. Heaven and earth become full of small self views such that, in that instant, the world is flooded with [greed, anger, ignorance and such] evil, and even a hair's worth of good cannot remain. But when the Dharma turns the self, and the Dharma is strong while the self is weak, then the world of “being experienced by millions of things and phenomena” is truly a pure and wonderful world that becomes true for anyone, and manifests the Way. That is how I understand. …

Through the generations from Shakyamuni Buddha to Master Bodhidharma and onward, the Ancestors have spoken of “the Samadhi of One Practice.” Through Zazen, we balance and settle the body while facing the wall, our form of sitting. When we have taken the posture of Zazen, the Dharma turns the self. Zazen is just such Practice. In actuality, with this body, when with the whole body one sits Zazen, the world instantaneously is Dharma and the self turns, and the world becomes a Great Purity whereby no difficulties remain. Because body and mind are one, when the body is made straight and true, the heart responds accordingly and becomes the straightness of Great Purity. Thus, when one person sits one minute of Zazen, the whole world changes to Great Purity.

***

People in the world cannot Practice unless they have a Karmic affinity to do so. Those who cannot Practice are lost in confusion and suffering. It is then a question of what such people should do. There is cause and effect, the cause and the result, such that in making evil and doing

bad things one will fall, but making and doing good one will rise. This is the truth of the universe. Each individual's acts of good and bad certainly bear fruit. But because we keep moving forward [in life], when we invite such lost people together to sit Zazen, we can get them heading instead in a good direction. Doing this is the religious heart. This is what I feel is the heart we should carry.

***

We encounter a world of Great Purity free of dust and impurities, and we can encounter all the 10,000 things [all the phenomena of the universe] in this way. … It is a world free of measure and judgments. … For example, if we sit Zazen for one minute, thus there is one minute of Buddha, which is Satori. Satori leads to Satori leads to Satori. It is not just a one time Satori, but the entirety is Satori. What we call “Satori” is the realization spoken of in Master Dogen's teaching “Practice and Realization are One.” It is much like saying that if we take a single bowl of rice, that one bowl of rice alone can fill our stomach and is everything. This is the Satori of rice. ... When we offer Gassho, that is making a Buddha with Gassho, the Satori of Gassho. When we prostrate we make a Buddha, the bow is all, all becomes one. … This is realization, for Satori is not some special sudden moment when light pours forth brightly, something one seeks and acquires suddenly after years of sitting. Not at all. …

***

In Master Dogen's Gakudo Yojinshu, he states, “In the buddha way, one should always enter and experience enlightenment through Practice. … one should know that arousing Practice in the midst of delusion, one attains enlightenment even before recognizing so.” This “Practice in the midst of delusion” means while right amid confusion. As Practice advances, this confusion is the place for a Bodhisattva's merciful and compassionate heart, the kind heart of Buddha, the loving heart of a mother in caring for a child. This is confusion and to be bathed in confusion. A mother may feel that she must do this thing for her beautiful child, or that to help her child, but we might say that each others' mutual bodies are also in a kind of separation and confusion. This skin, flesh, bones and marrow, the whole body, may be called by the name of confusion.

But that confusion, when one is sitting Zazen with the entire body, is Practice amid confusion. Then, this “attains realization before even recognizing so” is as Master Dogen said in another writing, Gyobutsu YuIgi, “Keep in mind that Buddhas, being within the Buddha's Way, do not wait for enlightenment.” Because the many Buddhas do not wait for enlightenment, enlightenment is not something in need of waiting for. Already, right now, each intimate act from morning until night whether walking, standing, sitting or reclining, doing just this to help all the people of this world, wishing to do that other thing, just each individual act is already Satori. One is already in Satori even before experiencing Satori. … Continuing action by action, there is no gap, no missing space.

***

To give rise to good mind, to arouse beginner's mind, thereupon to arouse resolve, and then to really take action, are all coming about by Practice. The Buddha Way is actually realized by our making effort, putting all to work with this human body, whereby the Buddha Way first comes to be truly lived.

[Even though we are Originally Enlightened], without actual conduct and cultivation such does not manifest. But to the extent we actually practice this with the limbs and whole body, the skin, flesh, bones and marrow actually embody this and such becomes ours. Otherwise, it is not truly ours and we cannot truly live it. Thus we must Practice.

***

Practice and Realization are One. During the fifty-four years of Master Dogen's life, in writing, washing his face morning and night, all the various actions, sitting, standing, walking, and reclining, drinking tea and eating meals, every such action one-by-one without exception was Practice-Realization. To Practice is Enlightenment, this was Dogen's signature Teaching. He dedicated himself so all through his life as a gift to us. It is just like the compassion felt toward a small grandchild by the loving heart of grandmotherly mind. Master Koun Ejo, the successor to Master Dogen who assisted his Teacher for some twenty years, after his death built a small hut next to his master's grave and continued for some fifty years until his own death … with a sincere and earnest heart, a gentle, loyal mind … to honor and serve his master without once stepping away. However, another student, Master Tettsû Gikai, would supplicate Dogen during his life like a cajoling child pleading to receive Transmission of the Dharma, asking to please be given that noble essence. However, despite this request, because there was yet a lack of a loving, grandmotherly mind in Gikai, in the end he did not receive Dogen's permission before Dogen died [and had to wait for many years]. Truly, when we engage in Practice, unless we lose our small self, we will not be vessels of the truth.

***

Zazen and all our daily actions [study, working, eating and cleaning] naturally come together as whole. If we make sincere effort, it will necessarily be experienced by anyone. What one sows in Practice is what one reaps. This is Karma. The good and bad Karmic actions we do are also what we necessarily come to receive. There is a saying, “What I sow, another does not reap; what another sows, I do not reap. But what I sow, I reap.” Truly, the way this works is very precise, and it is not difficult to grasp.

Each individual, if in each moment he regulates his walking, standing, sitting or reclining, can open the world of the Dharma.

***

To “arouse Bodhi mind” is something that manifests naturally in ourselves. Master Dogen rearranged a bit the words “arousing Bodhi mind” so that it became “Bodhi mind arises.” For a long time, if you just do one thing wholeheartedly and effusively, such will necessarily come pouring out. It is mutual and it is natural. When a child we have put to bed sleeps enough, by himself his eyes will naturally open and he will awake all smiles. But if we suddenly wake him up for some reason, he will cry and complain. So, Master Dogen said “arousing Bodhi mind” becomes “Bodhi mind arises.” Master Dogen said in Shobogenzo Zazenshin, “the first zazen is the first sitting Buddha.” Even if the legs hurt or the body hurts, the first time we sit Zazen, the very first time we sit, is also the very first making of a sitting Buddha. This is what is taught in Shobogenzo Zazenshin. It shows how much our arousing Bodhi mind is noble. If we have the will and put it into Practice, we undertake actual practice and implementation. In other words, if we so engage in Practice-Enlightenment, we naturally make such our own. We must keep endeavoring for the long haul. In our Buddhist words, “Life after life and world after world, we are born again, we die again.” What is thus transmitted forever is, as Master Dogen states in Genjo Koan, “Then we can forget the mental trace of realization, and show the real signs of forgotten realization continually, moment by moment.” To keep going so for the very very long term is to have such a heart.

***

What is this forgetting “traces of enlightenment” that Master Dogen speaks of?

Everyone seems to be aiming for this thing called “Satori,” wondering what kind of incredible, fantastic happening it is, everyone appears to be running after what they consider this rare and wonderful thing. But Satori is just the enlightenment of Practice-Enlightenment, an enlightenment whereby, if one eats just a single bowl of rice, then the belly fills up with one bowl's worth, and then that circulates and fills up one's whole body. To go further and forget even that fact is “forgetting traces of enlightenment.” If we receive one bowl, we just smile and that is enough. That is “traces of enlightenment.” Then we forget and no thing remains even to name. If we sit for one minute, such is one minute of Buddha, and there is just nothing more. … So, “Then we can forget the mental trace of realization, and show the real signs of forgotten realization continually, moment by moment.”

***

I left home to be Ordained at the age of 12 years old. … In those days, Kishizawa Ian Roshi delivered some lectures on the Shobogenzo, and so came for a Shobogenzo Study Group to Shizuoka Prefecture. At that time, my senior brother trainee priest said, because it happened to be just the very next day right after my Ordination, “Rempo, please come bring some tea and sweets to Roshi's place.” When I asked him, “How should I offer sweets to the Roshi, what should I say?” my brother monk said, “Please do take one.” At that point I don't remember if I kneeled down or bent down or stood up while serving, but I remember saying to the Roshi, “Please do take one.” And I put out a Japanese sweet beancurd pastry. Smiling and looking at my face, the Roshi said, “Eh, you will only give me one?” He laughed. I was really surprised, so I sprang up and ran away. After that, the Roshi was very kind to me for the next fifty years, but after he died what I still remember is, “Eh, you will only give me one?” You see, “One thing is all phenomena,” all is one. This means that one is all. This is a noble teaching in fact, and for us our every action, each move of the hand or move of the foot, is truly the noble path of the Buddha way. It is taught that our entire self is there.

***

When it is said "Body-Mind are One," this means that the human body in its entirety is the mind. And the mind in its entirety is the human body as well. This is the very fundamental point of the Teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha. We sum it up with the single phrase "Body-Mind are One," and do not divide them into two things. It is a non-Buddhist teaching to divide them into two. It becomes a different teaching. Thus, when the body is straight and true, the mind becomes straight and true. The doorway to the teachings is founded on this "Body-Mind are One," a teaching continuing right to us for 2500 years until today. Body is mind. It is something quite deeper than the ordinary view of world and society.

Abbot Renpo Niwa

by Nishijima Gudo Wafu

I have had two reverend Masters who taught me directly. One is Master Kodo Sawaki, and the other is Master Renpo Niwa.

The other Master, by whom I was so much instructed, was Master Renpo Niwa. Owing to the fact that he later became the Abbot of Eiheiji Temple, I would like to call him the Abbot of Eiheiji, following a traditional habit that is observed sometimes.

By the time I was 16 years old, I had begun to have much interest in Master Dogen's Buddhist thoughts, especially in Shobogenzo, and so I have studied it for so many years.

After studying Master Dogen's Shobogenzo for many years, I began to translate it from the old Japanese language into the modern Japanese, including the original Japanese text, comments on vocabulary, and the translation in modern Japanese. After accomplishing the translation I began to publish "Gendaigoyaku Shobogenzo, or Shobogenzo in modern Japanese." At that same time I wanted to begin my lectures of Shobogenzo at several places. Therefore first I asked Doctor Akira Hirakawa, who was the Chairman of The Youngmen Buddhist Association of Tokyo Imperial University, and I was permitted to have a lecture on every Saturday in the afternoon. And at that time I made my mind to become a Buddhist monk in Soto Sect.

Therefore it was necessary for me to find a Buddhist Master, who would permit me to become a Buddhist monk. And fortunately I have found the name of Abbot Renpo Niwa in the graduated students-list of Shizuoka Governamental High School.I visited the Master at the Tokyo Branch of Eiheiji, and I asked to become a Buddhist monk by him, and I was happily permitted to become a monk by him. And when he listened to my proposal of becoming a Buddhist monk, I noticed that he shed a little bit of tears in his eyes, and he wiped them. So I felt that it might be a joyful fact for him to have me as his monk, who was a graduate of the same high school 14 years younger than he. At that time I already had become the chief of a section in the Japan Security Finance Co., and so he was very kind and careful for me not to meet any kind of difficulty in my secular job.

After having the ceremony to become a Buddhist monk formally, I began to teach people Zazen and Shobogenzo, even in the Tokyo Eiheiji Branch too. And because it was held every Thursday afternoon, I finished my job a little earlier than usual, and went to the temple wearing a common suit as an usual salaried man. Therefore taking off my coat, and wearing the Kashaya over a white dress shirt, I gave my Buddhist lecture in the temple. But Buddhist monks in the temple thought that it was much inadequate for a Buddhist monk to have a Buddhist lecture wearing a Kashaya on the western white dress shirt, and so they asked the Master to stop such an informal style in the temple. To this Master Renpo Niwa said, "It is not so bad, because he seems to be like an Indian monk," and so I could continue my Buddhist lecture in the temple without changing my style.

Then I began lead Sesshin in the temple at the end of Summer, and at that time, of course, I wore the formal black clothes of the Buddhist monk. Also, at The Buddhist Association of Tokyo University, and so forth, I used the formal Buddhist clothes as a monk without fail.

Then I began to lead Sesshin in Master Renpo Niwa's temple called Tokei-in. I lead Sesshin at Tokei-in 6 times a year, for my Japanese audience once, for a foreign audience in English once, and for Employees of Ida Companies four times a year.

Master Renpo Niwa was born at Shuzenji in Shizuoka Prefecture as the third son of Katoda Shioya, in February of 1905. His father was a schoolmaster of several schools, and had sons and daughters totalled 10. And Mura, his mother, worked hard as a farmer for further support of their family. Master Niwa told me that he was a rather tender boy, and enjoyed to play with girls. But when observing the very smart style of a Budhist monk who commuted to Shuzenji temple, he found himself wanting to become a Buddhist monk. So when he was 11 years old, he asked his family if he could become a Buddhist monk, and he was permitted.

And fortunately because his uncle Master Butsu-an Niwa was the Master of Tokei-in in Shizuoka City, and so Master Renpo Niwa became a son-in-law of Master Butsu-an, therefore Master Renpo Niwa commuted from Tokei-in to a primary school. But because he selected Nirayama Middle school near Shuzenji, and so he commuted to the middle school from his home, but because he entered into the Shizuoka High School, therefore he commuted to the high school from Tokei-in again.

When Master Renpo Niwa was going to enter into a University, Master Butsu-an asked Master Renpo to select a law division in the University. However, because Master Renpo strongly hoped to study Buddhism in the University, he insisted his own strong hope, and Master Butsu-an permited Master Renpo to enter into the division of Buddhism. I guess that at that time, even in the Soto Sect, there might have been so many lawful problems occurring, and so Master Butsu-an wanted to get a good assistant for himself in the Soto Sect. But I heard that Master Butsu-an easily permitted Master Renpo to select the Indian Philosophical Division.

Master Renpo Niwa entered the division of Indian Philosophy in Tokyo Imperial University, and during the first summer vacation, he visited Eihei-ji as a Buddhist monk officially for one month. After graduating from Tokyo University, he became the head official in Tokei-in, and then visiting Antaiji in Kyoto for commuting to Otani University, and then he entered into Eihei-ji. Then he became the Master of Ichjoji and Ryu-un-in in Shizuoka, and he succeeded the Master of Tokei-in in November of 1955. He became the Master of the Tokyo Branch of Eihei-ji in 1960, and then he worked as the 77th Abbot of Eihei-ji from April 1985 to September 1993.

I was taught so much by the Abbot Renpo Niwa about how I shall live as a human being. The Abbot Renpo Niwa was a very delicate and generous person, and he didn't have any possibility to become emotional. I have heard a story of him like this. One night, many young monks of Eihei-ji Tokyo Branch went out to drink alcohol, and they didn't come back throughout the night. At that time Master Rempo Niwa got up early in the morning, and when the monks came back from outside, and he was standing at the entrance of the temple. Meeting them there he said, "I guess you are very tired from working so hard without any sleep at all during the night." Just saying so, he quietly returned to his private room. Therefore the monks were so surprised, and I heard that since then they stopped going out so late to drink alcohol.When I visited him in his private room accidentally, he sometimes served me a cup of green tea that he himself prepared. And at that time, even though he did not teach me especially with words, I was able to gain so much knowledge simply by watching his behavior.He showed me at that time that there were so many teachings in his behavior.

When the 76th Abbot Egyoku Hata was so seriously sick in his own temple, I was in Master Niwa's room for a private talk accidentally. At that time Master Niwa was calling up the Abbot's temple, and asking whether it is necessary for Master Niwa to visit the Abbot for consolation. But the information from the Abbot's temple was that "The Abbot's condition has become much better, and he is now practicing rehabilitation, and so please do not worry about such a problem." But Master Renpo said that he had received exact information of Abbot Hata, that his situations were so serious, concretly from a person, who was sitting in the Abbot's room at that time, and so situations were never so peaceful. And listening to such a situation, I could notice clearly that everyone could never tell a lie at every moment throughout his or her life. And at the same time I noticed that a person, who has become powerful in human societies, must to be careful of information.http://gudoblog-e.blogspot.com/2006/08/dogen-sangha-4-two-reverend-masters.html

San Francisco, December 12, 1971: Funeral ceremony of Shunryu Suzuki roshi conducted by

Rempo Niwa, who came from Japan, Dainin Katagiri, and Daigyo Moriyama, the priest at Sokoji.

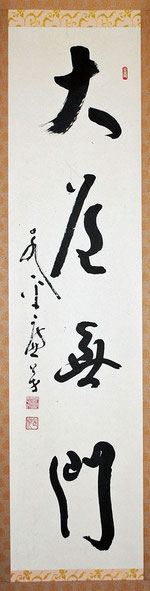

Calligraphies by Rempo Niwa Zenji

大道無門 Great Way Gateless

無礙 No Obstacles

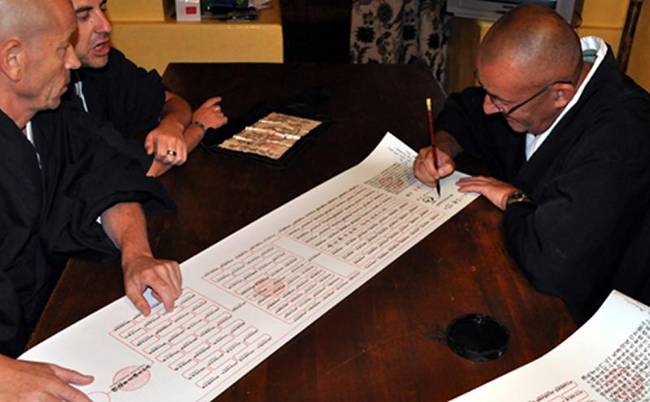

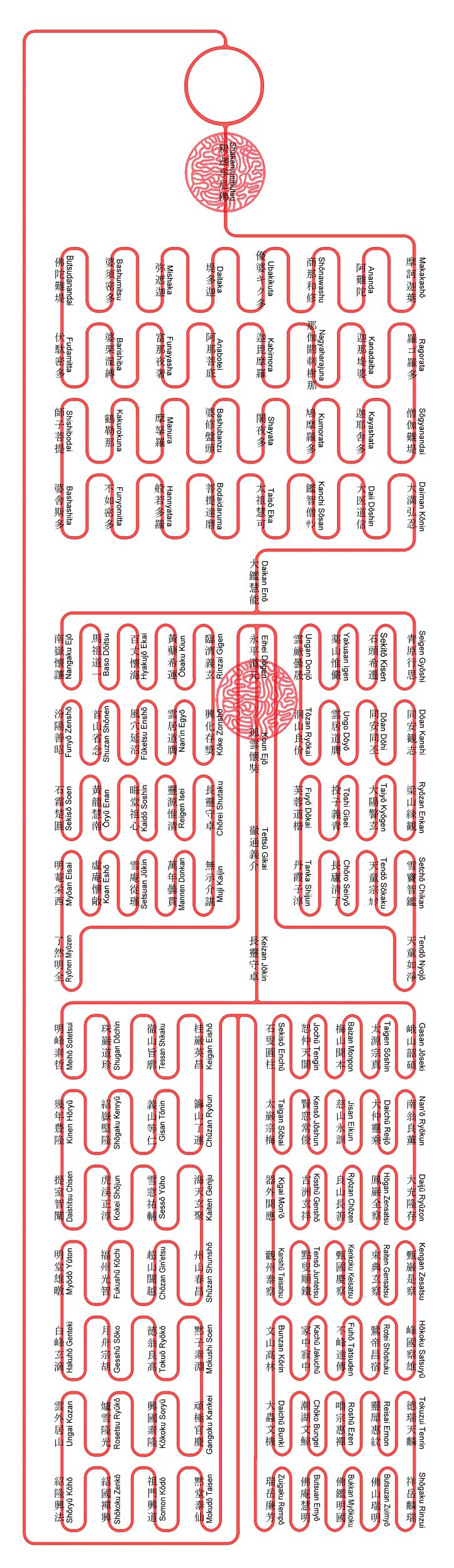

佛祖正傳菩薩大戒血脈

Busso shōden bosatsu daikai kechimyaku

Veine de sang de bodhisattva grands préceptes authentiquement transmis par des bouddhas et des ancêtres

The Bloodline of the Buddha’s and Ancestors’ Transmission of the Great Bodhisattva Precepts

1. 永平道元 Eihei Dōgen (1200-1253) Le zen japonais de l'école sôtô commence avec lui. Né en 1200 au sein de la plus haute aristocratie japonaise, Dôgen entra adolescent comme novice au Mont Hiei, le monastère de l'école tendai. Il se rendit par la suite auprès du maître Ryônen Myôzen (1184-1225) au Kenninji où il s'initia au zen. Avec Myôzen, il se rendit en Chine en 1224. Il y demeura trois ans et reçut la transmission du maître Rujing (1163-1228, jap. Nyojô). À son retour, il demeura près de Kyôto où il fit construire le premier monastère spécifiquement zen au Japon, le Kôshôji. En 1243, il partit avec ses disciples dans la province d'Echizen (l'actuelle préfecture de Fukui) où il fit construire le monastère du Daibutsuji rebaptisé par la suite en Eiheiji. Il mourut en 1253.

2. 孤雲懐奘 Koun Ejō (1198-1280) Du clan Fujiwara. Ejô appartenait à l'école zen de Dainichi Nônin (dite Daruma-shû) lorsqu'il rejoignit Dôgen dans son monastère de Kôshôji en 1234. Son plus fidèle disciple, il fut appointé comme chef des moines du Kôshôji en 1236 et assista Dôgen dans la compilation de son Shôbôgenzô. Il lui succéda comme second abbé d'Eiheiji. Les dernières années de sa vie furent marquées par le conflit qui perdura entre Gikai, son successeur, et ses autres condisciples. Après avoir abandonné sa charge d'abbé, il dut finalement la reprendre après le départ quelque peu forcé de Gikai. Il est l'auteur du "Samâdhi de la réserve lumineuse" (Kômyôzô zammai, 1278). On lui doit également un "Recueil des choses entendues à propos du Shôbôgenzô" (Shôbôgenzô Zuimonki), une compilation d'impromptus de Dôgen, composée à la fin des années 1230, toujours considérée comme une introduction "lisible" à la pensée du maître.

3. 徹通義介 Tettsū Gikai (1219-1309) D'une branche du clan Fujiwara établie dans la province d'Echizen et l'un des disciples d'Ekan de l'école Daruma-shû. Lorsque l'école fut persécutée, Ekan et plusieurs de ses disciples, dont Gikai, rejoignirent la communauté du Kôshôji. À Eiheiji, il occupa les fonctions de cuisinier (jap. tenzo) ; il y reçut la transmission d'Ekan en 1251. Après la mort de Dôgen, Ejô lui conféra sa propre transmission en 1255. Gikai voyagea ensuite quelques années et se rendit peut-être en Chine. À son retour à Eiheiji, il édifia de nouveaux bâtiments et introduisit de nouveaux rituels. En 1267, il succéda à Ejô comme troisième abbé mais un conflit surgit avec ses anciens condisciples. Finalement il dut partir après cinq ans passés à la tête d'Eiheiji. Il s'établit alors une vingtaine d'années, avec sa mère, dans un ermitage non loin d'Eiheiji. Il convertit par la suite un monastère shingon, en un monastère zen, le Daijôji, qui fut officiellement ouvert en 1293.

4. 螢山紹瑾 Keizan Jōkin (1268-1325) En 1271, il reçut la tonsure de Gikai, puis il devint quelque temps son assistant personnel à Eiheiji. Mais ce n'est qu'après diverses pérégrinations, à l'âge de trente-deux ans, qu'il le rejoignit finalement au Daijôji. En 1295, il reçut sa transmission et la robe (jap. kesa) de Dôgen déjà remise par Ejô à Gikai. Trois ans après, il lui succéda comme abbé du Daijôji. Puis il ouvrit le monastère de Yôkôji, dans la péninsule de Noto, auparavant un temple shingon, où il s'installa en 1317. Ce monastère restera le monastère principal des disciples immédiats de Keizan. Il ouvrit par la suite le monastère de Sôjiji, un ancien monastère de l'école Ritsu dans la province de Sagami (dans l'actuelle préfecture de Kanagawa) qui connut une longue destinée. Sôjiji fut officiellement inauguré en 1324. Keizan est l'auteur de plusieurs ouvrages, notamment "Les trois sortes de méditation" (Sankon zazen setsu), "Le recueil des points à observer dans la méditation" (Zazen yôjinki), "Le recueil de la transmission de la lumière" (Denkôroku), une série de sermons dans le style des recueils de la lampe chinois, ainsi que "Les Règles pures du Tôkokuji" plus connues sous le titre des "Règles pures de Keizan" (Keizan shingi).

5. 峨山韶碩 Gasan Jōseki (1275-1366) Il appartenait à une famille Minamoto et était originaire de la province de Noto (préfecture d'Ishikawa). Il commença ses études bouddhiques au sein de l'école tendai puis, après une rencontre avec Keizan à Kyôto, il rejoignit ce dernier au monastère de Daijôji où il devint l'un de ses principaux disciples. Il fut le second abbé de Sôjiji qu'il dirigea pendant une quarantaine d'années et fut brièvement le quatrième abbé de Yôkôji. Gasan fut le premier maître au Japon à étudier la dialectique des cinq degrés (jap. goi) du maître chinois Dongshan Liangjie (jap. Tôzan Ryôkai, 807-869), fondateur éponyme de l'école sôtô. Des six principaux disciples de Keizan, seuls Meihô Sotetsu (1277-1350) et Gasan Jôseki jouèrent un rôle déterminant dans le développement ultérieur de l'école. Gasan eut vingt-cinq successeurs dont cinq qu'il qualifiait de particulièrement "avisés".

Gasan pratiqua encore longuement. Lorsque le temps fut mûr, Keizan l'envoya chez d'autres maîtres, notamment auprès de Kyôô Unryô, un maître rinzai. À son retour, Keizan l'encouragea : "- Maintenant tu peux enfin être un bourgeon dans la lignée sôtô". Ce qui ne fut pas du goût de Gasan qui partit en se couvrant les oreilles. Cela se passait comme ça en ce temps-là !

6. 太源宗真 Taigen Sōshin (?-1371) Il était originaire de la province de Kaga (dans l'actuelle préfecture d'Ishikawa). Après avoir reçu l'ordination dans un temple qui reste indéterminé, il se rendit à Sôjiji où il étudia sous la direction de Gasan. Il reçut sa transmission zen la 5e année de l'ère Jôwa (1349). Immédiatement après la mort de Gasan, il devint le 3e abbé de Sôjiji puis fut, à la fin de sa vie, le 13e abbé de Yôkôji. Il fonda également le monastère de Butsudaji (dans la province de Kaga). Il mourut le 20-11 de la 4e année de l'ère Oan (1371). Son enseignement s'inspirait, comme Gasan, de la dialectique des cinq degrés.

7. 梅山聞本 Baizan Monpon (?-1417) L'une des plus importantes figures de l'école sôtô à la fin du XIVe siècle. Il était de la province de Mino (dans l'actuelle préfecture de Gifu) et prit les vœux au Genjiji, un monastère de l'école vinaya. Il étudia le zen à Sôjiji et succéda à Taigen Sôshin. En 1382, il devint l'abbé-fondateur (jap. kaisan) d'un monastère dans la province d'Echizen (dans l'actuelle préfecture de Fukui), en fait un ancien temple, qu'il rebaptisa en Ryûtakuji. Il fonda également le temple de Kongôji et fut l'abbé de Butsudaji. Baisan fut élu en 1390 onzième abbé de Sôjiji et il instaura dans ce monastère, avec les héritiers de Gasan, un système de rotation abbatiale. Les abbés furent alors choisis alternativement dans les principales lignées issues de Gasan. Il mourut le 7-9 de la 24e année de l'ère Ôei [1417]. L'époque est propice aux anecdotes miraculeuses. L'une d'elles veut que Baisan se soit une fois réfugié dans une maisonnée pour y passer la nuit. La maisonnée, perdue dans la campagne, était alors déserte. Mais le maître des lieux revint au milieu de la nuit, ivre mort. Il prit le moine pour un voleur, dégaina son sabre et trancha vif l'intrus. Le lendemain matin, il se réveilla pris de remord quand il vit, à sa grande surprise, Baisan calmement assis en méditation. Il s'écria : "Comment est-ce possible ?" mais Baisan ne répondit pas, se contentant de sortir de ses manches une petite statuette de Kannon qu'il portait toujours avec lui. La statuette était tranchée en deux. L'homme se prosterna et devint – évidemment – le disciple de Baisan. Baisan avait une particulière dévotion pour la méditation. Dans le code monastique qu'il rédigea en 1415 pour son monastère de Ryûtakuji, il enjoignait ses moines de méditer vingt-quatre heures sur vingt-quatre s'ils n'avaient rien d'autre à faire !

8. 恕仲天誾 Jochū Tengin (1365-1437) Il était de la province de Shinano (dans l'actuelle préfecture de Nagano) et son nom de famille était Mino. Il étudia avec le maître Rinzai Daisetsu Sonô dont il reçut l'ordination puis avec Baisan Mompon dont il reçut la transmission. Par la suite, il se rendit dans la province d'Omi (dans l'actuelle préfecture de Shiga) où il construisit un ermitage du nom de Tôshun'an qu'il rebaptisa immédiatement en Tôju'in. Un seigneur de la province de Tôtômi (dans l'actuelle préfecture de Shizuoka) du nom de Yamauchi le pria ensuite de faire construire un temple dans lequel il pourrait prier. En 1401, Tengin abandonna toutes ses activités et se mit en quête d'un terrain propice. Il trouva le lieu guidé, selon la légende, par le bodhisattva Kannon. Il fit construire un temple qu'il baptisa Teikyô'in puis rapidement Daitô'in qui fut inauguré en 1411. Il fit de son maître, Baisan Mompon, le fondateur honoraire du temple, lui-même devenant officiellement le second abbé. Le shogun Ashikaga Yoshimochi offrit les terres alentours. Une fois le monastère construit, le kami de la montagne vint nuitamment dans les appartements de Tengin afin de recevoir les préceptes zen. Ce dernier l'ordonna et pour le remercier le kami lui promit de créer une source d'eau minérale, non loin de là. Le lendemain matin, il y eut un léger tremblement de terre et la source jaillit du flanc de la montagne. La source coule toujours... En 1430, Tengin prit la charge du Ryûka'in dans la province d'Echizen (dans l'actuelle préfecture de Fukui) fondé par son maître où il séjourna trois ans, puis il revint au Tôju'in. Il mourut le 5-11 de la 12e année de l'ère Eikyô (1440) à l'âge de 75 ans. Avant de mourir, Tengin demanda à ses disciples que ses funérailles restent simples et, qu'à la place des cérémonies, ils s'assoient tous en méditation. Sur les 17.549 temples actuels de l'école sôtô, plus de 3.200 font remonter leur lignée à Jochû Tengin.

9. 石叟圓柱 Sekisō Enchū (?-1455) Second abbé de Tôkei'in. En 1452, par l'entremise de son frère, vassal de Fukushima Iga no Kami, ce dernier confia à Sekisô des terres qui se trouvait près d'un ancien temple shingon du nom de Kikei'an, près de l'actuelle ville de Shizuoka, qu'il rebaptisa en Tôkei'in. Il fit de son défunt maître Jochû Tengin l'abbé-fondateur (jap. kaisan) du temple, lui-même prenant officiellement la place de second abbé.

10. 太巌宗梅 Taigan Sōbai (?-1502) Troisième abbé de Tôkei'in, en fait le premier abbé en fonction. Il édifia l'ensemble des bâtiments à la demande de Sekisô Enchû, son maître. Trois de ses disciples se succédèrent à la tête de Tôkei'in : Kensô Jôshun, Gyôshi Shôjun et Efu Keimon qui furent respectivement les quatrième, cinquième et sixième abbés. La charge abbatiale fut ensuite assumée à tour de rôle et jusqu'en 1872, par chacune des lignées issues de ces trois abbés selon le système de rotation en usage dans l'école sôtô.

11. 賢窓常俊 Kensō Jōshun (?-1507) Quatrième abbé de Tôkei'in. Il assuma la charge d'abbé de Tôkeiin et de Sôshinji. Il fonda le temple de Shinju'in dans l'ancienne province de Suruga (actuelle préfecture de Shizuoka). Il eut deux principaux disciples Toshun et Jisan.

12. 慈山永訓 Jisan Eikun Second abbé de Shinju'in. Abbé-fondateur du Gofuzan Eimeiji (actuellement Raigakuji dans la préfecture de Nagano).

13. 大仲靈乘 Daichū Reijō Troisième abbé du Shinju'in. Abbé-fondateur du Myôonji (actuelle préfecture de Nagano), fondé en 1530. Sa pierre tombale se trouve au Myôonji.

14. 南翁良薫 Nan'ō Ryōkun Abbé de Shinju'in

15. 大充隆存 Daijū Ryūzon Abbé de Shinju'in

16. 鳳巌全察 Hōgan Zensatsu Abbé de Shinju'in

17. 良山長善 Ryōzan Chōzen Abbé de Shinju'in

18. 吉洲玄祥 Kisshū Genshō Abbé de Shinju'in

19. 器外聞應 Kigai Mon'ō Abbé de Shinju'in

20. 觀州泰察 Kanshū Taisatsu Abbé de Shinju'in. Il était du temple d'Eimeiji. Il se rendit au Shinju'un et en 1592 fut invité à prendre la direction d'un ancien temple de l'école Shingon, le Fuzô'in, dans l'ancienne province de Suruga (l'actuelle préfecture de Shizuoka) qu'il rebaptisa en Bukkokuzan Hôzôji. Il en devint le nouvel abbé-fondateur (jap. kaisan). Le Hôzôji était un temple subordonné (jap. matsuji) du Shinju'in.

21. 點叟順鐵 Tensō Juntetsu Second abbé de Hôzôji

22. 甄國慶察 Kenkoku Keisatsu Troisième abbé de Hôzôji

23. 來典玄察 Raiten Gensatsu Quatrième abbé de Hôzôji

24. 甄巌是察 Kengan Zesatsu Cinquième abbé de Hôzôji

25. 峰國察雄 Hōkoku Satsuyū Sixième abbé de Hôzôji

26. 鷺帝昌宿 Rotei Shōshuku Septième abbé de Hôzôji

27. 不峰達傳 Fuhō Tatsuden Huitième abbé de Hôzôji

28. 家中寂中 Kachū Jakuchū Neuvième abbé de Hôzôji

29. 文山高林 Bunzan Kōrin Dixième abbé de Hôzôji

30. 大蟲文機 Daichū Bunki Onzième abbé de Hôzôji.

31. 潮湖文鯨 Chōko Bungei Douzième abbé de Hôzôji.

32. 嚕宗惠襌 Roshū Ezen Treizième abbé de Hôzôji.

33. 靈犀惠紋 Reisai Emon Quatorzième abbé de Hôzôji.

34. 徳瑞天麟 Tokuzui Tenrin Quinzième abbé de Hôzôji.

35. 祥岳麟瑞 Shōgaku Rinzui Seizième abbé de Hôzôji.

36. 佛山瑞明 Butsuzan Zuimyō (増田 Masuda) Dix-septième abbé de Hôzôji et quatrième supérieur du temple de Tôkei'in (dans le nouveau système de numérotation post-Meiji).

37. 佛鑑明國 Bukkan Myōkoku (1862-1904; 丹羽 Niwa) Troisième supérieur de Tôkei'in.

38. 佛庵慧明 Butsuan Emyō (1880-1955; 丹羽 Niwa) Cinquième supérieur de Tokei'in.

39. 瑞岳廉芳 Zuigaku Rempō (1905-1993; 丹羽 Niwa) Il succéda à Butsuan Emyô Niwa comme supérieur du temple de Tokei'in. Après avoir assumé le poste de vice-abbé, il devint en 1985 le 77e abbé du monastère d'Eiheiji, l'un des deux principaux temples de l'école sôtô. Il reçut alors le titre impérial de Jikô Enkai zenji ("Maître zen Lumière de Compassion, Océan de Plénitude"). Il est décédé en septembre 1993. Tetsuzan Gendô Niwa lui a succédé en 1986 comme supérieur de Tokei'in. Ses calligraphies sont réputées. Il les signait de divers noms de plume : Robai ("Le vieux prunier"), Baian ("L'ermitage au prunier") ou Baishian. |

1. 永平道元 Eihei Dōgen (1200-1253) The Zen of the Japanese Sôtô school begins from him. Born in 1200 into the highest Japanese aristocracy, Dôgen entered adolescence as a novice priest at Mount Hiei, the principal monastery of the Tendai school. He left to study with Master Ryônen Myôzen (1184-1225) at Kenninji, where he was initiated into Zen. With Myôzen, he traveled to China in 1224. Remaining there for three years, he accepted transmission from Master Rujing (1163-1228, jap. Nyojô). On his return, he first remained close to Kyoto, where he established the initially specifically Zen monastery in Japan, Kôshôji. In 1243, Dogen left Kyoto with his disciples for the province of Echizen (the current Fukui Prefecture) where he build the monastery of Daibutsuji, renamed thereafter Eiheiji, and still one of the two head temples of Japanese Sôtô Zen Buddhism. He is the author of any number of works important to the Sôtô school and the Zen world, including the Shôbôgenzô(“Dharma Treasury of the True Eye.”) Dogen died in 1253. 2. 孤雲懐奘 Koun Ejō (1198-1280) A member of the Fujiwara clan. Ejô belonged to the Zen school of Dainichi Nônin (known as the Daruma-shû) prior to eventually joining Dôgen at his monastery of Kôshôji in 1234. A faithful disciple, Ejo was appointed as chief monk of Kôshôji in 1236, and assisted Dôgen in the compilation of his Shôbôgenzô. Ejo succeeded Dogen as second abbot of Eiheiji. The last years of his life were marked, however, by what is known as the “Third Generation Controversy,” which arose between Gikai, his successor, and other members of the school. After having given up his role as abbot, Ejo had to finally take it up again after the rather forced departure as abbot of Gikai. Ejo is the author of the “Samâdhi of the Treasury of the Radiant Light” (Kômyôzô Zanmai, 1278). We also owe to him the “Record of Things Heard from the Shôbôgenzô” (Shôbôgenzô Zuimonki), a compilation of extemporaneous talks by Dôgen, composed at the end of the years 1230, and always regarded as a “readable” introduction to the thought of the Master. 3. 徹通義介 Tettsū Gikai (1219-1309) Born to a branch of the Fujiwara clan in the province of Echizen, Gikai was originally one of the disciples of Ekan of the Daruma-shû school. When that school was persecuted, Ekan and several of his disciples, including Gikai, joined Dogen's community at Kôshôji. Later, at Eiheiji, he occupied the key monastic role of temple cook (jap. tenzo), and there received transmission from Ekan in 1251. After the death of Dôgen, Ejô conferred his own transmission on Gikai in 1255. Gikai may have then traveled for a few years, including to China. On his return to Eiheiji, he erected new buildings and introduced new rituals. In 1267, Gikai succeeded Ejô as third abbot, but a conflict emerged with his fellows concerning his duel lineage. Finally, Gikai was forced to depart after five years spent as the head of Eiheiji. He lived many years thereafter with his mother, in a hermitage not far from Eiheiji. Later, he converted a monastery of the Shingon school into a Zen monastery, Daijôji, which was officially opened in 1293. 4. 螢山紹瑾 Keizan Jōkin (1268-1325) In 1271, Keizan accepted the tonsure from Gikai, then became for some time his personal attendant at Eiheiji. But it is only at the end of various travels, at the age of thirty-two, that Keizan finally joined Gikai at Daijôji. In 1295, Keizan received the transmission and the robe (jap. kesa) of Dôgen previously presented by Ejô to Gikai. Three years after, Keizan succeeded Gikai as abbot of Daijôji. Thereafter, he established the monastery of Yôkôji on the Noto peninsula, where he settled in 1317. This monastery would remain the principal monastery of the immediate disciples of Keizan. He also established the monastery of Sôjiji in 1324, which would later go on to become, with Dogen's Eiheiji, one of the two head temples of the Soto school. Keizan is the author of several works, in particular, The Three Kinds of Zen Practitioner” (Sankon Zazen Setsu), “Points to be Observed in Zazen” (Zazen Yôjinki), “The Collection of the Transmission of the Light” (Denkôroku), a series of sermons in the style of the collections of the Chinese lamp, such as “The Pure Rules of Tôkokuji,” better known under the title “The Pure Rules of Keizan” (Keizan Shingi). 5. 峨山韶碩 Gasan Jōseki (1275-1366) A son of the Minamoto family, with origins in the province of Noto (the present Ishikawa Prefecture). Gasan began his Buddhist studies within the Tendai school then, after a meeting with Keizan in Kyoto, joined with Keizan at the monastery of Daijôji, where he became one of Keizan's principal disciples. He was later the second abbot of Sôjiji, which he directed over a period of forty years, and was briefly the fourth abbot of Yôkôji. Gasan was the first master in Japan to make study of the dialectical system of the “Five Degrees” (jap. goi) of Chinese Master Dongshan Liangjie (jap. Tôzan Ryôkai, 807-869), founder and namesake of the Sôtô school. Of the six principal disciples of Keizan, only Meihô Sotetsu (1277-1350) and Gasan Jôseki have played a part in determining the later development of the school. Gasan had twenty-five successors, including five that he described as particularly “sensible.” Gasan went on to practice most intently. When the time was ripe, Keizan sent him to study with other Masters, in particular with Kyôô Unryô, a Rinzai Master. On Gasan's return, he replied to Keizan, “We must inherit this mind that is as beautiful as the moon.” Keizan Zenji heard that reply and recognized Gasan Zenji as his successor,“Now you can finally be a bud in the Sôtô line.” 6. 太源宗真 Taigen Sōshin (?-1371) Born in the province of Kaga (in the present prefecture of Ishikawa). After having received ordination at a temple which remains unspecified, he went on to Sôjiji, where he studied under the direction of Gasan. Taigen accepted Zen transmission from Gasan in the 5th year of the Jôwa era (1349). Immediately after the death of Gasan, Taigen became the 3rd abbot of Sôjiji then, at the end of his life, the 13th abbot of Yôkôji. He also founded the monastery of Butsudaji (in the province of Kaga). Taigen died in the 4th year of the Oan era (1371). His teaching was inspired, like Gasan, by the dialectic of the “Five Degrees.” 7. 梅山聞本 Baizan Monpon (?-1417) One of the most important figures of the Sôtô school at the end of the 14th century. A native of Mino Province (in the current prefecture of Gifu) , Baisan took the priestly vows at Genjiji, a monastery of the Vinaya school of Buddhism. He later studied Zen at Sôjiji and succeeded as heir to Taigen Sôshin. In 1382, Baisan became the abbot-founder (jap. kaisan) of a monastery in the province of Echizen (in the current prefecture of Fukui), in fact an old temple which he renamed Ryûtakuji. He also founded the temple of Kongôji and was the abbot of Butsudaji. Baisan was appointed in 1390 as the eleventh abbot of Sôjiji, and founded in this monastery, with the heirs to Gasan, a system of abbacy rotation. Under this system, abbots of Sojiji were to be alternatively selected from among the principal lines originating from Gasan. Baisan died in the 24th year of the Oei era [1417]. 8. 恕仲天誾 Jochū Tengin (1365-1437) A native of the province of Shinano (in the current prefecture of Nagano), his family surname was Mino. Tengin studied with the Rinzai Master Daisetsu Sonô, from whom he accepted ordination, then later with Baisan Mompon from whom he received transmission. Thereafter, Tengin went on to the province of Omi (in the current prefecture of Shiga) where he built a hermitage of the name Tôshun'in, that he soon renamed Tôju'an. A lord of the province of Tôtômi (in the current prefecture of Shizuoka) named Yamauchi then requested him to build a temple at which the lord could make prayers. In 1401, Tengin gave up all his other activities and went in search of a favorable location. He found the place guided, according to legend, by the Bodhisattva Kannon. There, he built a temple that he later named Daitô'in, inaugurated in 1411. Tengin made his own Master, Baisan Mompon, the honorary founder of the temple, with Tengin himself becoming officially the second abbot. The shogun Ashikaga Yoshimochi offered neighboring lands in donation. 9. 石叟圓柱 Sekisō Enchū (?-1455) Second abbot of Tôkei'in. In 1452, via his brother, a vassal of Fukushima Iga No Kami, this last entrusted to Sekisô lands which were close to an old temple of Shingon Buddhism named Kikei'an, close to the current town of Shizuoka. Sekisô renamed this the Tôkei'in and dedicated it to Zen. He named his late Master, Jochû Tengin, the abbot-founder (jap. kaisan) of the temple, with himself officially becoming its second abbot. 10. 太巌宗梅 Taigan Sōbai (?-1502) Third abbot of Tôkei'in, who built the entirety of its buildings at the request of his Master. Three of his disciples followed one another as head of Tôkei'in: Kensô Jôshun, Gyôshi Shôjun and Efu Keimon, who were respectively the fourth, fifth and sixth abbots. The abbacy was then assumed in turns until 1872, by each line originating from these three abbots, following the system of rotation in use in the Sôtô school. 11. 賢窓常俊 Kensō Jōshun (?-1507) Fourth abbot of Tôkei'in. He assumed the position of abbot of Tôkei'in and Sôshinji. He also established the temple of Shinju'in in the old province of Suruga (the current prefecture of Shizuoka), and had two principal disciples, Toshun and Jisan. 12. 慈山永訓 Jisan Eikun Second abbot of Shinju'in. Abbot-founder of Gofuzan Yômeiji (in the current prefecture of Nagano)

13. 大仲靈乘 Daichū Reijō Third abbot of Shinju'in. Abbot-founder in 1530 of Myôonji (in the current prefecture of Nagano), his tomb stone is found there. 14. 南翁良薫 Nan'ō Ryōkun Abbot of Shinju'in 15. 大充隆存 Daijū Ryūzon Abbot of Shinju'in 16. 鳳巌全察 Hōgan Zensatsu Abbot of Shinju'in 17. 良山長善 Ryōzan Chōzen Abbot of Shinju'in 18. 吉洲玄祥 Kisshū Genshō Abbot of Shinju'in 19. 器外聞應 Kigai Mon'ō Abbot of Shinju'in 20. 觀州泰察 Kanshū Taisatsu Abbot of Shinju'in. Originally from the temple of Eimeiji (in the prefecture of Nagano), he went on to Shinju'in and, in 1592, was invited to take the direction of an old temple of the Shingon school, Fuzô'in, in the old province of Suruga (the current prefecture of Shizuoka) which he renamed Bukkokuzan Hôzôji. He became the abbot-founder (jap kaisan). Hôzôji was made a subordinate temple (jap. matsuji) of Shinju'in. 21. 點叟順鐵 Tensō Juntetsu Second abbot of Hôzôji 22. 甄國慶察 Kenkoku Keisatsu Third abbot of Hôzôji 23. 來典玄察 Raiten Gensatsu Fourth abbot of Hôzôji 24. 甄巌是察 Kengan Zesatsu Fifth abbot of Hôzôji 25. 峰國察雄 Hōkoku Satsuyū Sixth abbot of Hôzôji 26. 鷺帝昌宿 Rotei Shōshuku Seventh abbot of Hôzôji 27. 不峰達傳 Fuhō Tatsuden Eighth abbot of Hôzôji 28. 家中寂中 Kachū Jakuchū Ninth abbot of Hôzôji 29. 文山高林 Bunzan Kōrin Tenth abbot of Hôzôji 30. 大蟲文機 Daichū Bunki Eleventh abbot of Hôzôji. 31. 潮湖文鯨 Chōko Bungei Twelfth abbot of Hôzôji. 32. 嚕宗惠襌 Roshū Ezen Thirteenth abbot of Hôzôji. 33. 靈犀惠紋 Reisai Emon Fourteenth abbot of Hôzôji. 34. 徳瑞天麟 Tokuzui Tenrin Fifteenth abbot of Hôzôji. 35. 祥岳麟瑞 Shōgaku Rinzui Sixteenth abbot of Hôzôji. 36. 佛山瑞明 Butsuzan Zuimyō (増田 Masuda) 37. 佛鑑明國 Bukkan Myōkoku (1862-1904; 丹羽 Niwa) 38. 佛庵慧明 Butsuan Emyō (1880-1955; 丹羽 Niwa) Fifth superior of Tokei'in. 39. 瑞岳廉芳 Zuigaku Rempō (1905-1993; 丹羽 Niwa) He succeeded Butsuan Emyô Niwa as superior of the Tokei'in. After having assumed the station of vice-abbot, he became in 1985 the 77th abbot of the Eiheiji monastery, one of the two principal temples of the Sôtô school. He then received the imperial title of Jikô Enkai Zenji (“Great Zen Master of Compassion, Ocean of Plenitude”). He died in September 1993 Tetsuzan Gendô Niwa succeeded him in 1986 as the abbot of Tokei'in. |

![]()

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niwa_Zenji

Zuigaku Rempō Niwa Zenji (Shizuoka, 1905-1993) est un maître zen japonais.

En vertu du système de transmission familiale des temples introduit par la réforme de l'époque Meiji, il se fit moine assez tôt, après ses études au lycée de Shizuoka. Selon le système inauguré au xviiie siècle par Menzan, il reçut la transmission du Dharma (shiho) trois ans après avoir pris les préceptes. Il fut pour cela adopté par le supérieur du temple Tokei-in, de Shizuoka, selon un système complexe de rotation entre plusieurs temples de la localité, occasion à laquelle il prit le nom héréditaire de Niwa.

À 50 ans, il fut nommé supérieur de la branche de Tokyo du temple Eihei-ji. Fervent pratiquant de zazen, il y fit reconstruire le zendo (salle de méditation) afin que les jeunes en formation (pour la plupart fils de chefs de temple) puissent revenir à cette pratique essentielle.

Il devint ensuite le supérieur du Eihei-ji, dans les montagnes du Fukui (mer du Japon). Ainsi qu'à Tokyo, il y pratiquait zazen tous les matins avec les moines, selon les enseignements du fondateur du lieu, maître Dōgen.

Il a été le maître de Gudo Nishijima et de Moriyama Daigyo.

Au premier rang, de gauche à droite: Thibaut, Rech, Niwa zenji, Zeisler

Taisen Deshimaru sensei décède le 30 avril 1982 à Tokyo, d’un cancer du pancréas, sans avoir donné de transmission officielle (shiho). Après sa mort trois de ses plus proches disciples ont été certifiés maîtres (en 1984) dans la tradition du zen Sōtō, par Niwa Zenji, sans jamais avoir connu :

Roland Rech (1944-), nom de dharma:

泰山雄能

Taisan Yūnō (AZI – Association Zen Internationale)

Étienne Zeisler (1946-1990), nom de dharma: 仙空黙照 Senkū Mokushō

Stéphane Thibaut (1950-), nom de dharma: 泰元興仙 Taigen Kōsen

(Association du Vrai Zen de maître Deshimaru; Kōsen sangha)

Wikipédia français sur Deshimaru: En 1965, avant de mourir, Kôdô Sawaki lui donne l'ordination de moine. En 1974 (Showa 49) Deshimaru reçut le shihō (嗣法) officiel de Yamada Zenji, [鷲峰霊林 Juhō Reirin (山田 Yamada 1889–1979)], un fervent partisan de l'armée impériale japonaise, abbé de Eihei-ji [副貫首 fuku-kanshu = vice-abbé]. A titre anecdotique, il lui fallut se faire réordonner par Yamada, car les documents d'enregistrement de son ordination par Sawaki avaient été perdus. En 1985, Niwa Zenji, abbé de ce même temple, lui conféra à titre posthume la dignité de zenji.

Dans le Zen, la tradition veut qu'un disciple dont le maître est décédé sans transmettre le Dharma doive se chercher un nouveau maître. Lorsque cette formalité est rendue difficile par une circonstance ou une autre, il est fréquent qu'un supérieur de temple important comme le Eihei-ji fasse entrer dans son lignage ceux qui se trouvent dans ce cas, et c'est ainsi que Zuigaku Rempō a été amené à donner sa transmission à trois disciples de 弟子丸 (黙堂) 泰仙 Deshimaru (Mokudō) Taisen (1914-1982), à la mort de ce dernier.

Zenji (littéralement, « maître zen ») est un titre honorifique accordé aux supérieurs du temple Eihei (Eihei-ji), siège principal de l'école Sōtō, fondé au xiiie siècle par maître Dôgen.

La politesse veut, en principe, qu'on ne donne plus leur nom laïc aux moines bouddhistes après leur décès, mais seulement leur nom religieux.

Transmission du dharma par Stéphane Thibaut (Taigen Kōsen)

Ketsumyaku, certificat d'affiliation à la lignée des grands Maîtres et des Bouddhas du temps passé, remis au moine lors de l'ordination

http://www.zen-deshimaru.com/fr/zen/lignee-des-patriarches-du-bouddhisme-zen

![]()

The zen lineage chart of Roland Rech (Taisan Yūnō),

inherited the dharma of both Deshimaru Mokudō Taisen & Niwa Zuigaku Rempō.

Edited by Gábor Terebess.

http://lademeuresl.free.fr/maitres.htm

"Zenji" car il fut le précédent supérieur du temple de Maître Dogen, Eiheiji. C'est la plus haute position de l'école Soto Zen. Il est mort le 7 septembre 1993.

Niwa Zenji est né dans un temple de haut rang, lié a l'aristocratie. Il devint moine tres tôt, puis Maître et fut nommé a 50 ans supérieur de la branche de Tokyo du temple Eiheiji. Il y fit reconstruire un nouveau zendo (salle de méditation) car lui meme pratiquait beaucoup le zazen et il souhaitait que les religieux venus faire leurs années de formation pratiquent également de façon plus intensive.

Puis il devint le supérieur du temple de Eiheiji auquel il imprima un nouvel élan, venant chaque matin pratiquer avec les moines, redonnant a ce lieu le gout du Dharma de Maître Dogen. Il devint aussi un grand soutien pour les groupes de zen a l'étranger: ainsi, comme il est de tradition pour les Zenji de faire entrer dans leurs lignages ceux qui pour une raison ou pour une autre n'ont plus de Maître, il donna sa transmission a plusieurs disciples de Maître Deshimaru, à la mort de ce dernier.

Il aida Maître Moriyama à commencer Zuigakuin, puis il aida également la disciple de ce dernier, Joshin Sensei, a fonder la Demeure sans limites. Nous avons tous, pratiquants en Europe, une grande dette de gratitude envers lui!

« En 1988, je suis allé au temple de Eiheiji avec un groupe de pratiquants européens. L'abbé était un moine respecté du nom de Niwa Renpô Zenji âgé de plus de 80 ans. Il venait de subir une lourde opération chirurgicale et se reposait dans ses appartements. Après quelques jours, nous fûmes autorisés à venir brièvement le saluer. Niwa Zenji parla à ses assistants d'une voix douce et à peine audible. Il voulait se prosterner devant nous. Deux personnes furent nécessaires pour l'aider à se baisser jusqu'à ce que son front puisse toucher terre et à se relever. Et ceci par trois fois. Puis il repartit lentement, sans avoir rien dit. Ce fut un immense choc. Le chef suprême de l'école Sôtô Zen s'était prosterné devant de simples pratiquants de passage. Mais il avait puisé dans la bienveillance et la tendresse et toutes les attentes, toutes les convenances s'étaient brisées d'un coup. Cet homme avait pu nous introduire à l'inconcevable. […] »

Eric Romelluère, « Le message du Bouddha »

![]()

http://h-kishi.sakura.ne.jp/kokoro-541.htm

https://eiheizen.jimdo.com/%E6%B0%B8%E5%B9%B3%E5%AF%BA77%E4%B8%96-%E4%B8%B9%E7%BE%BD%E5%BB%89%E8%8A%B3%E7%A6%85%E5%B8%AB/