SZÓTÓ ZEN SŌTŌ ZEN

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

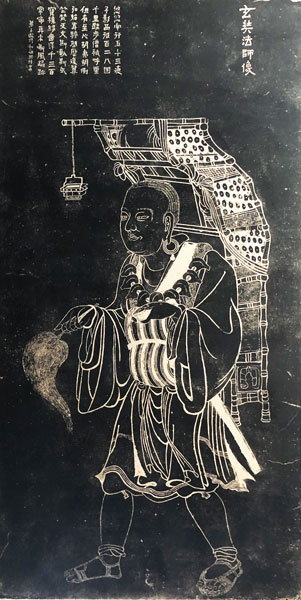

Hszüan-cang (玄奘 Xuanzang, 602–664), kőpacskolat

Mahā prajñā pāramitā hṛdaya sūtra

(Mahá pradzsnyá páramitá hridaja szútra)

![]() A szív szútra

A szív szútra

![]() The Heart Sutra

The Heart Sutra

![]() Sūtra du cœur

Sūtra du cœur

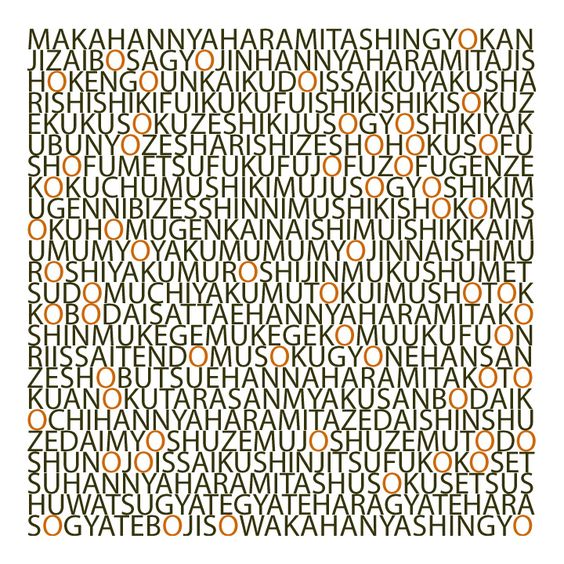

![]() 摩訶般若波羅蜜多心経 Maka hannya haramit[t]a shingyō

摩訶般若波羅蜜多心経 Maka hannya haramit[t]a shingyō

![]()

A VÉGSŐ BÖLCSESSÉG SZÍVE

(A szív szútra)

Terebess Gábor fordítása 1967, nyomtatásban: 1976, 1996

Ez a szöveg A szív szútra avagy A végső bölcsesség szíve japán olvasata és magyar fordítása Hszüan-cang (玄奘 Xuanzang, 602 körül – 664. február 5.) kínai szövegéből - a zenben ezt a verziót használják. A buddhista tanítás egyik legrövidebb, legszebb foglalata. Minden japán zen szerzetes kívülről tudja, a reggeli szertartás kezdetén és számos más alkalommal is kántálja a „fahal” dob (木魚 mokugyo) szívdobogást idéző hangjára.

Midőn Avalókitésvara bódhiszattva a végső bölcsességbe mélyedt, felismerte az öt halmaz ürességét és megvált minden szenvedéstől.

Ó, Sáriputra! Az alakzat nem más, mint üresség, az üresség nem más, mint alakzat; üresség bizony az alakzat, alakzat bizony az üresség. Így van az érzet, az észlelet, az indíték, a tudat is.

Ó, Sáriputra! Üresség a sajátja mindeneknek: nem születnek, nem enyésznek, nem szennyeződnek, nem tisztulnak, nem gyarapszanak, nem fogyatkoznak.

Nincs hát az ürességben alakzat, érzet, észlelet, indíték, tudat. Nincs szem, fül, orr, nyelv, test, elme. Nincs alak, hang, szag, íz, tapintat, eszme. Nincs világa a szemnek és így tovább, míg nincs világa a tudatnak. Nincs nem-tudás és nincs szűnte a nem-tudásnak, míg nincs öregség és halál, s nincs szűnte az öregség- és halálnak. Nincs szenvedés, eredet, megszűnés, út. Nincs tudás, sem siker, mert nincs mi sikerülhetne.

A bódhiszattva a végső bölcsességre hagyatkozik, hogy szellemét mi se gátolja; s mert gáttalan, nem szorong többé, kibontakozik fonák nézetei közül és eljut a nirvánába. A hármas idő minden buddhája a végső bölcsességre hagyatkozik, hogy elérje a teljes és tökéletes megvilágosulást. Ezért a végső bölcsesség a legszentebb ige, a legragyogóbb ige, a felülmúlhatatlan ige, a páratlan ige, amely lebírhat minden szenvedést, igazán és csalhatatlanul.

Ezért a végső bölcsesség igéje így nyilatkozik meg: „Eljött, eljött, végigjött, túl-jött, köszöntessék a megvilágosulás!”

A Kőrösi Csoma Sándor Intézet Közleményei, 1976. 1-2. szám, 78. oldal;

Terebess Kiadó szórólapja, 1996

Vö:

Hamvas Béla (ford.): Az észt meghaladó tudás (A szív-szútra, 1955), Az ősök nagy csarnoka I., Medio Kiadó, 2003, 381-382. old.Csongor Barnabás (ford.): Mahápradzsnápáramitá, azazhogy a nagy értelem segélyével a túlsó partra átjutásnak minden vágyak könyve.

In: Vu Cseng-en: Nyugati utazás avagy a Majomkirály története, Bp., Európa, 1969, 1. kötet, 289-290. old.; 1980, 1. kötet, 266-267. old.Hetényi Ernő (tibetiből ford.): A bölcsesség lényege, A Kőrösi Csoma Sándor Intézet Közleményei, 1974, 3-4. sz., 33-34. old. [A tibeti szöveg átírásban: u.o. 30-32. old.]; Maha-prajna paramita-hridaya, 5-8. oldal, in: Dhyána-sútrák - A Maháyána-buddhizmus meditáció-szútrái, Buddhista Misszió, 1984

Migray Emőd (angolból ford.) Szív szútra, Hszüan Hua [宣化 Xuanhua, 1918-1995] Tripitaka Mester magyarázatával.

Eredeti cím: Heart Sutra and Commentary, Buddhist Text Translation Society, San Francisco, 1980Dobosy Antal (ford.): A mély meghaladó bölcsesség szíve szútra © 1989, módosítva 2012-ben

Bánfalvi András (ford.): Szív szútra, Hosszabb és rövidebb változat,

F. Max Müller szanszkritból készített angol fordítása alapján. Farkas Lőrinc Imre Könyvkiadó, 2001, 5-12. old. PDFHadházi Zsolt (ford.): Szív szútra (2006)

Hadházi Zsolt (ford.): Pradnyápáramitá Szív szútra (2007)

Fődi Attila (ford.): A tökéletes bölcsesség szíve szútra © 2008-2012

Agócs Tamás (ford.): Az Önfelülmúló Megismerés Szíve (Bhagavatí Pradnyápáramitá Hridaja)

Lilávadzsra (Pressing Lajos) (ford.): A Túljutott Belátó Megértés szíve szútra

Komár Lajos (ford. Dobosy Antal fordítását felhasználva): A túlpartra juttató bölcsesség szíve szútra (2011)

Rudlof Dániel (ford.): A túlpartra vivő tökéletes bölcsesség szíve (2018)

Rudlof Dániel: A Szív-szútra eredetének kérdései

„Közel, s Távol” VIII. Az Eötvös Collegium Orientalisztika Műhely éves konferenciájának előadásaiból 2018, 67-82. oldal

http://honlap.eotvos.elte.hu/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Kozel_s_Tavol_IX.pdfAntal Péter (ford.): A meghatározhatatlan legmagasabb rendű közvetlen önmegismerés szent tudománya (2025.04.15. nyomtatóbarát)

[0848c07] 觀自在菩薩行深般若波羅蜜多時,照見五蘊皆空,度一切苦厄。

[0848c08] 「舍利子!色不異空,空不異色;色即是空,空即是色。受、想、行、識,亦復如是。

[0848c10] 「舍利子!是諸法空相,不生不滅,不垢不淨,不增不減。是故,空中無色,無受、想、行、識;無眼、耳、鼻、舌、身、意;無色、聲、香、味、觸、法;無眼界,乃至無意識界;無無明亦無無明盡,乃至無老死亦無老死盡;無苦、集、滅、道;無智,亦無得。

[0848c14] 「以無所得故,菩提薩埵依般若波羅蜜多故,心無罣礙;無罣礙故,無有恐怖,遠離顛倒夢想,究竟涅槃。三世諸佛依般若波羅蜜多故,得阿耨多羅三藐三菩提。

[0848c18] 「故知般若波羅蜜多,是大神咒,是大明咒,是無上咒,是無等等咒,能除一切苦真實不虛,故說般若波羅蜜多咒。」

[0848c22] 「揭帝 揭帝 般羅揭帝 般羅僧揭帝 菩提 僧莎訶」

T251 《 般若波羅蜜多心經 》 = Prajñāpāramitā-hṛdaya-sūtra, kínaira fordította Xuanzang 649-ben.

Irodalmi értékű magyar fordításai: Hamvas Béláé és Csongor Barnabásé.

AZ ÉSZT MEGHALADÓ TUDÁS

(A szív-szútra)

Hamvas Béla fordítása 1955, nyomtatásban: 2003

A tiszteletreméltó Avalokitésvara bódhiszattva amikor az észt meghaladó tudás gyakorlásában elmélyedt, ezt tapasztalta:

A világnak öt alkotóeleme van, és ezek természetük szerint üresek. Sáriputra, szólt, az alakok üresek itt, és úgy mondom, hogy az üresség alak. Az üresség az alaktól nem különbözik, és az alak az ürességtől nem különbözik. Ami alak, az üresség, és ami üresség, az alak.

Nem mondhatsz mást sem az érzékelésre, sem a névre, sem a megértésre, sem az ismeretre.

Minden dolog természete, Sáriputra, hogy üres, nincsen sem kezdete, sem vége, nem hibátlan, és nem nem hibátlan, nem tökéletlen és nem tökéletes. Éppen ezért, Sáriputra, ebben az ürességben nincs alak, nincs érzékelés, nincs név, nincs megértés, nincs ismeret. Nincs se szem, se fül, sem orr, se száj, se test, se lélek. Nincs sem alak, se hang, sem illat, sem íz, sem érintés, se tárgy.

Nincs itt sem ismeret, se nem tudás, sem az ismeret lerombolása, sem a nem tudás lerombolása. Nincs lehanyatlás és nincs halál, és nincs a lehanyatlás lerombolása és a halál lerombolása. Nincs itt a négy nagy igazság, nincs szenvedés, nincs szenvedés keletkezése, nincs a szenvedés megszüntetése és nincs a szenvedés megszüntetéséhez vezető út. Nincs ismeret és nincs megérkezés.

Ha valaki a bodhiszattva észt meghaladó tudása felé indul, tudatába bezárva marad. De ha a tudat fátyla eloszlott, minden félelmet levet, túl minden tévelygésen a végső megszabadulást eléri.

A múlt, a jelen és a jövő minden felébredettjében, mikor az észt meghaladó tudás felé indul, a legmagasabb tökéletes tudás világosodik meg.

Ezért kell tudni az észt meghaladó tudás nagy versét, a Nagy Tudás versét, a meghaladhatatlan verset, az összehasonlíthatatlan verset, amely minden szenvedést megszüntet. Igaz, mert nem téved, amit az észt meghaladó tudás mond:

Menj, menj, menj át a túlsó partra, köss ki a túlsó parton, Bodhi szvaha.

Az ősök nagy csarnoka I., Medio Kiadó, 2003, 381-382. oldal

Mahápradzsnápáramitá,

azazhogy a nagy értelem segélyével a túlsó partra átjutásnak minden vágyak könyve

Csongor Barnabás fordítása 1969, 1980

Avalokitesvara bodhiszattva, mélységes mély pradzsnápáramitát cselekedvén az időben, megtekéntette vala, hogy az öt szkandha, azazhogy a forma, az érzéklet, az eszmélkedés, a cselekvés s az esméret mind semmiségek volnának, mik visznek keresztül s hurcolnak végig minden szenvedésen.

Ó, Sáriputra! Nem különbözik az alak a semmiségtől, s a semmiség sem az alaktól, merthogy az alak az igaz semmiség, s a semmiség az igaz alak. S így vagyon ez ismét a gondolkozással, így vagyon ez ismét a cselekedéssel.

Ó, Sáriputra! Mivelhogy minden buddhák csak üres káprázatok, nem születvén s el nem enyészvén, szenny nélkül s tisztaság nélkül való voltukban, nem gyarapodván s nem fogyatkozván.

Ennek okáért ezen üresség közepette nincsen alak, nincsen gondolkodás, nincsen cselekedet, nincsen sem szem, sem fül, sem orr, sem nyelv, sem test, sem pediglen elme, alak nélkül való benne a hang, az illat, az ízlelet, a tapintat, az ítélet, s e látomás nélkül való világ közepette mindenek sem fény nélkül nem valóak, sem fény nélkül nem valónak nem foghatók, ez lévén az elme s értelem nélküli valóság legvégső világa. Ez pedig a legvégső, halál nélkül való világ, amelyben halál nélkül nemvalóság sincsen. Ez pediglen a szenvedés és enyészet nélkül való út, bölcsesség nélkül való, rajta semmi el nem érhető.

S minekutána véle semmi el nem érhető, a bodhiszattva pradzsnápáramitájának okából a lélek előtt akadály nem találtatik. S mivelhogy akadály nem találtatik, ezért nincsen benne semmi félelem. Eltávoztatja mind a kusza káprázatokat, s a nirvánába elvezet. A jelen, múlt s jövendő buddhák is eme pradzsnápáramitá segélyével érik el az anuttara szamjak szambodhit, azazhogy a felülmúlhatatlan bölcsességnek tökélyét. Tudvalévő ezért, hogy a pradzsnápáramitá, a legszentebb ige, s legfénylőbb ige, a felülmúlhatatlan ige, a minden rangok nélkül való ige, mely eltávoztat minden gyötrettetést, igaz valósággal, nem pedig üres hívsággal.

Mondjad ezért a pradzsnápáramitának igéjét, mondván mondjad, hogy "Gati! Gati! Palágati! Palászanghati! Bodhiszattva-a!".

Vu Cseng-en: Nyugati utazás avagy a Majomkirály története, Bp., Európa,

1969, 1. kötet, 289-290. oldal;

1980, 1. kötet, 266-267. oldal

A szív szútra

A mély meghaladó bölcsesség szíve szútra

(Mahá pradzsnyá páramitá hridaja szútra)

Dobosy Antal fordítása 1989, módosítva 2012-ben

Avalókitésvara bódhiszattva a mély meghaladó bölcsességben időzvén látja, az öt alkotórész mindegyike üres, és ezzel minden szenvedést meghalad.

Sáriputra! A forma nem különbözik az ürességtől, az üresség nem különbözik a formától. A forma valóban üresség, az üresség valóban forma. Így ilyen az érzés, az érzékelés, az akarat és a tudatosság is.

Sáriputra! Minden jelenségnek üresség a természete. Nem keletkeznek, és nem szűnnek meg, nem tiszták, és nem szennyezettek, nem növekszenek, és nem csökkennek.

Ezért az ürességben nincs forma, érzés, érzékelés, akarat és tudatosság. Nincs szem, fül, orr, nyelv, test és értelem, nincs szín, hang, szag, íz, tapintás és tudati folyamat, nincs birodalma az érzékszerveknek és a tudatosságnak. Nincs nem tudás, és nincs annak megszűnése, nincs öregség és halál, és nincs ezek megszűnése sem. Nincs szenvedés, nincs annak oka, nincs annak megszűnése, és nincs útja a megszüntetésnek. Nincs megvalósítás, és nincs megérkezés, mivel nincs, amit el kellene érni.

A bódhiszattvának a meghaladó bölcsesség által akadálytól mentes a tudata. Mivel nincs akadály, nincs félelem sem, így meghaladva minden illúziót a megszabadulást eléri.

A három világ összes buddhái a meghaladó bölcsesség által valósítják meg a tökéletes és felülmúlhatatlan felébredettséget.

Ezért ismerd fel a meghaladó bölcsességet, a nagy szent eszmét, a nagy tudás eszméjét, a felülmúlhatatlan eszmét, a hasonlíthatatlan eszmét, azt, ami véget vet minden szenvedésnek, a bölcsességet, ami valóságos és nem hamis.

Ezért hangoztasd a meghaladó bölcsesség eszméjét, amely így szól:

gaté, gaté, páragaté, páraszamgaté, bódhi szváhá

gaté, gaté, páragaté, páraszamgaté, bódhi szváhá

gaté, gaté, páragaté, páraszamgaté, bódhi szváhá

http://www.zen.hu/szivszutra.html

A Szív Szútra

A túlpartra juttató bölcsesség szíve szútra

(Prajna paramita hridaya sutra)

translated from Sanskrit into Chinese by Hsuan-Tsang (602–664), into English by Red Pine (1943–)

Dobosy Antal fordítását felhasználva átdolgozta Komár Lajos

A nemes (arya) Kegyesen Alátekintő (Avalokiteshvara) tökélyharcos (bodhisattva) a mély, túlpartra juttató (paramita) bölcsesség (prajna) gyakorlásában áttekintette az öt alkotórészt (skandha), és látta, hogy azok ön-léte (svabhava) üres (sunya).

– Itt, Sáriputra! Az alakzat (rupa) üresség (sunyata) , az üresség (shunyata) alakzat (rupa). Az alakzat (rupa) nem különbözik az ürességtől (sunyata), az üresség (sunyata) nem különbözik az alakzattól (rupa). Minden alakzat (rupa) üresség (sunyata), minden üresség (sunyata) alakzat (rupa). Így ilyen az érzés (vedana), az érzékelés (sanjna), az akarat (sanskara), és a tudatosság (vijnana) is.

– Itt, Sáriputra! Minden jelenségnek (dharma) üresség (sunyata) a természete. Nem keletkeznek, és nem szűnnek meg, nem tiszták, és nem szennyezettek, nem tökéletesek, és nem tökéletlenek.

– Ennélfogva, Sáriputra, az ürességben (sunyata) nincs alakzat (rupa), érzés (vedana), érzékelés (sanjna), akarat (sanskara) és tudatosság (vijnana) sem. Nincs szem (caksur), fül (srota), orr (ghrana), nyelv (jihva), test (kaya) és értelem (manas) sem. Nincs alak (rupa), hang (sabda), szag (gandha), íz (rasa), tapintás (sprastavya) és gondolat (dharma) sem. Nincs egyik sem, a szemtől (caksur) az ismeretig (mano-vijnana). Nincs nem-tudás (avidya) és annak megszűnése, nincs öregség (jara) és halál (marana), és nincs ezek megszűnése sem. Nincs szenvedés (duhkha): nincs annak oka (samudaya), nincs annak megszűnése (nirodha), és nincs annak útja (marga) sem. Nincs tudomás (jnana), nincs megvalósítás (prapti), sem nem-megvalósítás (aprapti) .

– Ennélfogva, Sáriputra, megvalósítás (prapti) nélkül a Tökélyharcos (bodhisattva) menedéket vesz a túlpartra juttató bölcsességben (prajna paramita): akadálytól mentes (avarana) tudattal (citta) létezik. Mivel akadálytól mentes (avarana) a tudata (citta), rettenthetetlen, és meghaladva minden tévképzetet, eléri az ellobbanást (nirvana).

A múlt, a jelen és a jövő minden Megvilágosodottja (buddha) menedéket vesz a túlpartra juttató bölcsességben (prajna paramita), és a tökéletes (samyak), felülmúlhatatlan (anuttara) felébredettséget (sambodhi) eléri.

Ezért ismerd meg a nagy, túlpartra jutató bölcsesség (prajna paramita) igéjét (mantra), a Nagy Tudomás (maha-vidya) igéjét (mantra), a felülmúlhatatlan (anuttara) igét (mantra), a hasonlíthatatlan igét (mantra), ami véget vet minden szenvedésnek (duhkha), ami az igazság (satya), nem pedig hazugság.

A túlpartra juttató bölcsesség (prajna paramita) igéje (mantra) így hangzik: Elment (gate), átment (gate), teljesen túljutott (paragate), a túlsó partra átjutott (parasamgate), immáron felébredett (bodhi svaha).

gaté, gaté, páragaté, páraszamgaté, bódhi szváhá

gaté, gaté, páragaté, páraszamgaté, bódhi szváhá

gaté, gaté, páragaté, páraszamgaté, bódhi szváhá

Komár Lajos: Mahájána szútrák 1., A Tan Kapuja Buddhista Főiskola jegyzete, 2011

Heart Sutra in Chinese and Pinyin

xin_jing_pinyin.pdf

漢訳 般若心経の全文(玄奘三蔵訳)

仏説摩訶般若波羅蜜多心経

観自在菩薩 行深般若波羅蜜多時 照見五蘊皆空

度一切苦厄 舎利子 色不異空 空不異色 色即是空

空即是色 受想行識亦復如是 舎利子 是諸法空相

不生不滅 不垢不浄 不増不減 是故空中

無色 無受想行識 無眼耳鼻舌身意 無色声香味触法

無眼界 乃至無意識界 無無明亦 無無明尽 乃至無老死

亦無老死尽 無苦集滅道 無智亦無得 以無所得故

菩提薩タ 依般若波羅蜜多故

心無 礙 無ケイ 礙故 無有恐怖 遠離一切顛倒夢想 究竟涅槃

三世諸仏 依般若波羅蜜多故 得阿耨多羅三藐三菩提 故知般若波羅蜜多

是大神呪 是大明呪 是無上呪 是無等等呪

能除一切苦 真実不虚 故説般若波羅蜜多呪 即説呪日

羯諦 羯諦 波羅羯諦 波羅僧羯諦 菩提薩婆訶

般若心経

Chinese Translations

Links to CBETA version of the Taishō Tripiṭaka.Short Text

T250 《 摩訶般若波羅蜜大明呪經 》 = Mahāprajñāpāramitā-mahāvidyā-sūtra, attrib. Kumarajīva ca. 400 CE. [date and authorship are apocryphal].

T251 《 般若波羅蜜多心經 》 = Prajñāpāramitā-hṛdaya-sūtra, attrib. Xuanzang, 649 CE. [date and authorship are apocryphal], most of the Mahāyāna Buddhists in the world use this version.

T256 《 唐梵飜對字音般若波羅蜜多心經 》 Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya Sūtra: Tang Dynasty Sanskrit Translation with Correct Characters [Representing] Sounds. See also British Library manuscript (Or.8210/S.5648).

Long Text

T252 《 普遍智藏般若波羅蜜多心經 》 translated by 法月 Fǎyuè (Skt. *Dharmacandra?), ca. 741 CE.

T253 《 般若波羅蜜多心經 》 translated by Prajñā, ca. 788 CE.

T254 《 般若波羅蜜多心經 》 translated by Prajñācakra, 861 CE.

T255 《 般若波羅蜜多心經 》 translated from the Tibetan by Fǎchéng 法成, 856 CE, text found at 燉煌 Dūnhuáng.

T257 《 佛說聖佛母般若波羅蜜多經 》 translated by Dānapāla, 1005 CE.

Heart of Great Perfect Wisdom Sutra

Mahā Prajñāpāramitā Heart Sūtra

translated by Tripitaka Dharma Master 玄奘 Xuanzang, c.602-664 (Taisho Tripitaka 251)

translated from the Chinese version of Xuanzang by Sōtō Zen Text Project

摩訶般若波羅蜜多心經

觀自在菩薩。Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva,

行深般若波羅蜜多時。when deeply practicing prajñā pāramitā,

照見五蘊皆空。clearly saw that all five aggregates are empty

度一切苦厄。and thus relieved all suffering.

舍利子。色不異空。Shāriputra, form does not differ from emptiness,

空不異色。emptiness does not differ from form.

色即是空。空即是色。Form itself is emptiness, emptiness itself form.

受想行識 Sensations, perceptions, formations, and consciousness

亦復如是。are also like this.

舍利子。是諸法空相。Shāriputra, all dharmas are marked by emptiness;

不生不滅。they neither arise nor cease,

不垢不淨不增不減。are neither defiled nor pure, neither increase nor decrease.

是故空中。無色。Therefore, given emptiness, there is no form,

無受想行識。no sensation, no perception, no formation, no consciousness;

無眼耳鼻舌身意。no eyes, no ears, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind;

無色聲香味觸法。no sight, no sound, no smell, no taste, no touch, no object of mind;

無眼界。乃至無意識界。no realm of sight … no realm of mind consciousness.

無無明。亦無無明盡。There is neither ignorance nor extinction of ignorance…

乃至無老死。neither old age and death,

亦無老死盡。nor extinction of old age and death;

無苦集滅道。no suffering, no cause, no cessation, no path;

無智亦無得。no knowledge and no attainment.

以無所得故。菩提薩埵。With nothing to attain, a bodhisattva

依般若波羅蜜多故。relies on prajñā pāramitā, and thus

心無罣礙。the mind is without hindrance.

無罣礙故。無有恐怖。Without hindrance, there is no fear.

遠離顛倒夢想。究竟涅槃。Far beyond all inverted views, one realizes nirvana.

三世諸佛。All buddhas of past, present, and future

依般若波羅蜜多故。rely on prajñā pāramitā and thereby

得阿耨多羅三藐三菩提。attain unsurpassed, complete, perfect enlightenment.

故知般若波羅蜜多。Therefore, know the prajñā pāramitā

是大神咒。as the great miraculous mantra,

是大明咒是無上咒。the great bright mantra, the supreme mantra,

是無等等咒。能除一切苦。the incomparable mantra, which removes all suffering

真實不虛故。and is true, not false.

說般若波羅蜜多咒 Therefore we proclaim the prajñā pāramitā mantra,

即說咒曰 the mantra that says:

揭帝 揭帝 般羅揭帝 ”Gate Gate Pāragate

般羅僧揭帝 菩提 僧莎訶 Pārasamgate Bodhi Svāhā.”

般若波羅蜜多心經 (Prajñā Pāramitā Heart Sūtra)

Sōtō chant:

Ma-ka han-nya ha-ra-mit-ta shin-gyō

Symbols:

◎ strike large bowl-bell (üstgong)

● strike small bowl-bell (csészegong)

Kan-ji-zai bo-satsu, gyō jin han-nya ha-ra-mit-ta ji,

shō-ken ◎ go-on kai kū, do is-sai ku-yaku.

Sha-ri-shi, shiki fu-i kū, kū fu-i shiki, shiki soku-ze kū,

kū soku-ze shiki, ju-sō-gyō-shiki, yaku-bu nyo-ze.

Sha-ri-shi, ze-sho-hō kū-sō, fu-shō fu-metsu, fu-ku fu-jō,

fu-zō fu-gen, ze-ko kū-chū, mu-shiki mu-ju-sō-gyō-shiki.

Mu-gen-ni-bi-zes-shin-ni, mu-shiki-shō-kō-mi-soku-hō,

mu-gen-kai nai-shi mu-i-shiki-kai.

Mu-mu-myō yaku mu-mu-myō-jin, nai-shi mu-rō-shi,

yaku mu-rō-shi-jin, mu-ku-shū-metsu-dō,

mu-chi yaku mu-toku, i mu-sho-tok[u] ko.

Bo-dai-sat-ta, e han-nya ha-ra-mit-ta ◎ ko, shin mu-kei-ge,

mu-kei-ge ko, mu-u-ku-fu, on-ri is-sai ten-dō mu-sō,

ku-gyō ne-han, san-ze sho-butsu,

e han-nya ha-ra-mit-ta ◎ ko, toku a-noku-ta-ra

sam-myaku-sam-bo-dai.

Ko chi han-nya ha-ra-mit-ta, ze dai-jin-shu,

ze dai-myō-shu, ze mu-jō-shu, ze mu-tō-dō-shu,

nō jo is-sai ku, shin-jitsu fu-ko,

ko setsu han-nya ha-ra-mit-ta shu soku, setsu shu watsu

gya-tei gya-tei, ● ha-ra-gya-tei, hara-sō-gya-tei,

● bo-ji so-waka.

Han-nya shin-gyō.

Rinzai chant:

Ma-ka han-nya ha-ra-mi-ta shin-gyō

Kan-ji-zai bosa, gyō jin han-nya ha-ra-mi-ta ji,

shō-ken ◎ go-on kai kū, do is-sai ku-yaku.

Sha-ri-shi, shiki fu-i kū, kū fu-i shiki, shiki soku-ze kū,

kū soku-ze shiki, ju-sō-gyō-shiki, yaku-bu nyoze.

Sha-ri-shi, ze-sho-hō kū-sō, fu-shō fu-metsu, fu-ku fu-jō,

fu-zō fu-gen, ze-ko kū-chū, mu-shiki mu-jusō-gyō-shiki.

Mu-gen-ni-bi-zes-shin-ni, mu-shiki-shō-kō-mi-soku-hō,

mu-gen-kai nai-shi mu-i-shiki-kai.

Mu-mu-myō yaku mu-mu-myō-jin, nai-shi mu-rō-shi,

yaku mu-rō-shi-jin, mu-ku-shū-metsu-dō,

mu-chi yaku mu-toku, i mu-sho-tok[u] ko.

Bo-dai-sat-ta, e han-nya ha-ra-mi-ta ◎ ko, shin mu-kei-ge,

mu-kei-ge ko, mu-u-ku-fu, on-ri [is-sai] ten-dō mu-sō,

ku-gyō ne-han, san-ze sho-butsu,

e han-nya ha-ra-mi-ta ◎ ko, toku a-noku-ta-ra

san-myaku-san-bo-dai.

Ko chi han-nya ha-ra-mi-ta, ze dai-jin-shu,

ze dai-myō-shu, ze mu-jō-shu, ze mu-tō-dō-shu,

nō jo is-sai ku, shin-jitsu fu-ko,

ko setsu han-nya ha-ra-mi-ta shu soku, setsu shu watsu

gya-tei gya-tei, ● ha-ra-gya-tei, ha-ra-sō-gya-tei,

● bo-ji so-wa-ka.

Han-nya shin-gyō.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ccy708RQ1DA&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8qLgTLWfsLg&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OXAwlr7246I&feature=related

Heart Sutra

(Hannya shingyō 般若心経)

Full title: Heart of Great Perfect Wisdom Sutra

(Maka hannya haramitta shingyō 摩訶般若波羅蜜多心経)

Symbols:

◎ strike large bowl-bell

● strike small bowl-bell

Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, when deeply practicing

prajna paramita, clearly saw ◎ that all five aggregates are

empty and thus relieved all suffering. Shariputra, form

does not differ from emptiness, emptiness does not

differ from form. Form itself is emptiness, emptiness

itself form. Sensations, perceptions, formations, and

consciousness are also like this. Shariputra, all dharmas

are marked by emptiness; they neither arise nor cease,

are neither defiled nor pure, neither increase nor

decrease. Therefore, given emptiness, there is no form,

no sensation, no perception, no formation, no

consciousness; no eyes, no ears, no nose, no tongue, no

body, no mind; no sight, no sound, no smell, no taste, no

touch, no object of mind; no realm of sight... no realm

of mind consciousness. There is neither ignorance nor

extinction of ignorance... neither old age and death, nor

extinction of old age and death; no suffering, no cause,

no cessation, no path; no knowledge and no attainment.

With nothing to attain, a bodhisattva relies on prajna

parami ta, ◎ and thus the mind is without hindrance.

Without hindrance, there is no fear. Far beyond all

inverted views, one realizes nirvana. All buddhas of past,

present, and future rely on prajna paramita ◎ and

thereby attain unsurpassed, complete, perfect

enlightenment. Therefore, know the prajna paramita as

the great miraculous mantra, the great bright mantra,

the supreme mantra, the incomparable mantra, which

removes all suffering and is true, not false. Therefore

we proclaim the prajna paramita mantra, the mantra that

says: "Gate Gate ● Paragate Parasamgate ● Bodhi

Svaha.”

The Prajna Paramita Sutra

Translated by Shunryu Suzuki

http://www.cuke.com/Cucumber%20Project/other/heart-sutra/heart-sutra-card-4.htm

The following chant of the Prajna Paramita Sutra, translated by Shunryu Suzuki,

was chanted by Allen Ginsberg in the CD-ROM Haight-Ashbury in the Sixties:

http://www.rockument.com/Haight/Prajna.html

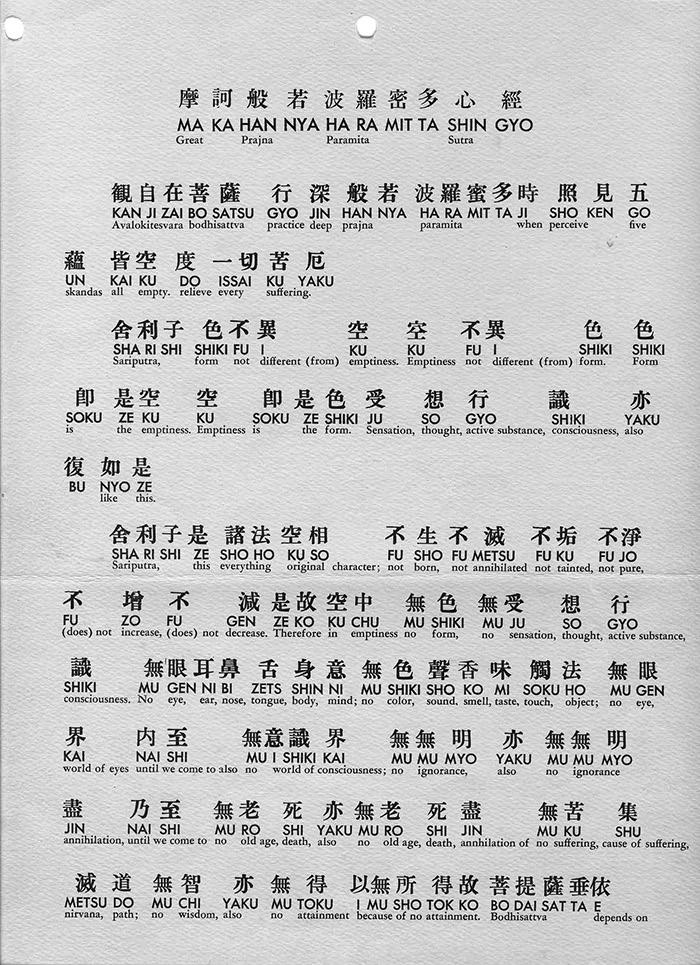

MA KA HAN NYA HA RA MIT TA SHIN GYO

Great Prajna Paramita Sutra

KAN JI ZAI BO SATSU GYO JIN HAN NYA HA RA MIT TA JI SHO KEN GO

Avalokitesvara bodhisattva practice deep prajna paramita when perceive five

UN KAI KU DO ISSAI KU YAKU

skandas all empty. relieve every suffering.

SHA RI SHI SHIKI FU I KU KU FU I SHIKI SHIKI

Sariputra, form not different (from) emptiness. Emptiness not different (from) form. Form

SOKU ZE KU KU SOKU ZE SHIKE JU SO GYO SHIKI YAKU

is the emptiness. Emptiness is the form. Sensation, thought, active substance, consciousness, also

BU NYO ZE

like this.

SHA RI SHI ZE SHO HO KU SO FU SHO FU METSU FU KU FU JO

Sariputra, this everything original character; not born, not annihilated not tainted, not pure,

FU ZO FU GEN ZE KO KU CHU MU SHIKI MU JU SO GYO

(does) not increase, (does) not decrease. Therefore in emptiness no form, no sensation, thought, active substance,

SHIKI MU GEN NI BI ZETS SHIN NI MU SHIKI SHO KO MI SOKU HO MU GEN

consciousness. No eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, mind; no color, sound, smell, taste, touch, object; no eye,

KAI NAI SHI MU I SHIKI KAI MU MU MYO YAKU MU MU MYO

world of eyes until we come to also no world of consciousness; no ignorance, also no ignorance

JIN NAI SHI MU RO SHI YAKU MU RO SHI JIN MU KU SHU

annihilation, until we come to no old age, death, also no old age, death, also no old age, death, annhilation of no suffering, cause of suffering,

METSU DO MU CHI YAKU MU TOKU I MU SHO TOK KO BO DAI SAT TA E

nirvana, path; no wisdom, also no attainment because of no attainment. Bodhisattva depends on

HAN NYA HA RA MIT TA KO SHIN MU KE GE MU KE GE KO MU U KU FU ON RI

prajna paramita because mind no obstacle. Because of no obstacle no exist fear; go beyond

I SSAI TEN DO MU SO KU GYO NE HAN SAN ZE SHO BUTSU E HAN

all (topsy-turvey views) attain Nirvana. Past, present and future every Buddha depend on prajna

NYA HA RA MIT TA KO TOKU A NOKU TA RA SAN MYAKU SAN BO DAI

paramita therefore attain supreme, perfect, enlightenment.

KO CHI HAN NYA HA RA MIT TA ZE DAI JIN SHU ZE DAI MYO SHU

Therefore I know Prajna paramita (is) the great holy mantram, the great untainted mantram,

ZE MU JO SHU ZE MU TO DO SHU NO JO IS SAI KU SHIN JITSU FU KO

the supreme mantram, the incomparable mantram. Is capable of assuaging all suffering. True not false.

KO SETSU HAN NYA HA PA MIT TA SHU SOKU SETSU SHU WATSU

Therefore he proclaimed Prajna paramita mantram and proclaimed mantram says

GYA TE GYA TE HA RA GYA TE HA RA SO GYA TE BO DHI SO WA KA

gone, gone, to the other shore gone, reach (go) enlightenment accomplish.

HAN NYA SHIN GYO

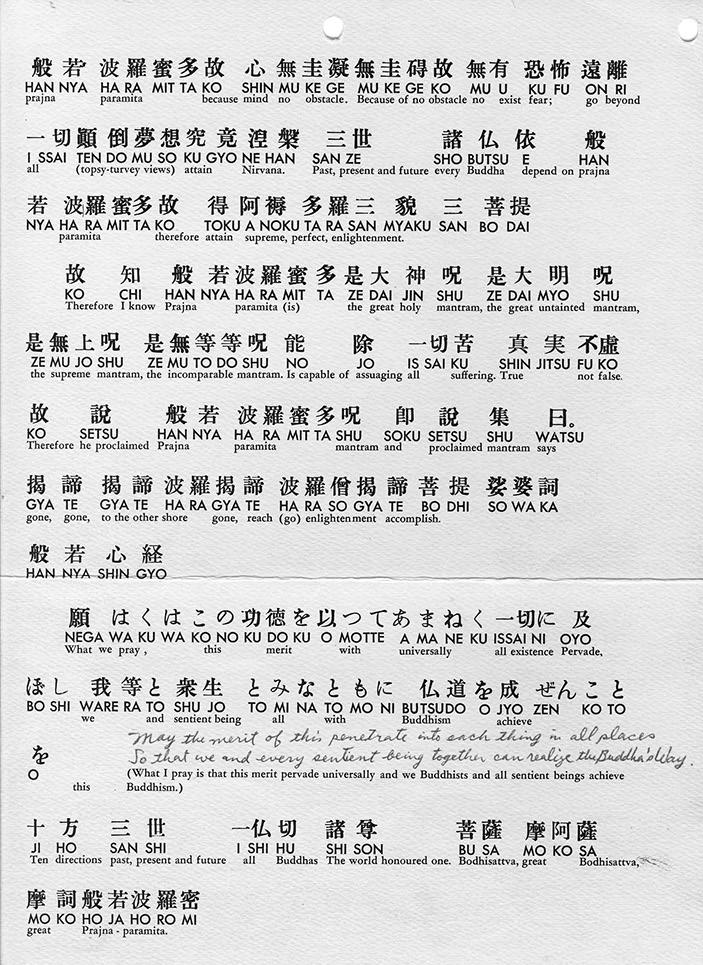

NEGA WA KU WA KO NO KU DO KU O MOTTE A MA NE KU ISSAI NI OYO

What we pray, this merit with universally all existence Pervade,

BO SHI WARE RA TO SHU JO TO MI NA TO MO NI BUTSUDO O JYO ZEN KO TO

we and sentient being all with Buddhism achieve this (What I pray is that this merit pervade universally and we Buddhists and all sentient beings achieve Buddhism.)

JI HO SAN SHI I SHI HU SHI SON BU SA MO KO SA

Ten directions past, present and future all Buddhas The world honoured one. Bodhisattva, great Bodhisattva,

MO KO HO JA HO RO MI

great Prajna-paramita.

摩訶般若波羅蜜大明呪經

Sūtra of the Great Illumination Mantra of Mahā-Prajñā-Pāramitā

Translated from Sanskrit into Chinese in the Later Qin Dynasty

by the Tripiṭaka Master Kumārajīva (鳩摩羅什, 344–413) from Kucha

English translation by Rulu (如露)

http://www.sutrasmantras.info/sutra15.html

As Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva went deep into prajñā-pāramitā, he saw in his illumination the emptiness of the five aggregates, [the realization of] which delivers one from all suffering and tribulations.

“Śāriputra, because form is empty, it does not have the appearance of decay. Because sensory reception is empty, it does not have the appearance of sensory experience. Because perception is empty, it does not have the appearance of cognition. Because mental processing is empty, it does not have the appearance of formation. Because consciousness is empty, it does not have the appearance of awareness.

“Why? Because, Śāriputra, form is no different from emptiness; emptiness is no different from form. In effect, form is emptiness and emptiness is form. The same is true for sensory reception, perception, mental processing, and consciousness. Śāriputra, dharmas, with empty appearances, have neither birth nor death, neither impurity nor purity, neither increase nor decrease. Emptiness, the true reality, is not of the past, present, or future.

“Therefore, in emptiness there is no form, nor sensory reception, perception, mental processing, or consciousness; no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, or mental faculty, nor sights, sounds, scents, flavors, tactile sensations, or mental objects; no spheres, from eye sphere to mental consciousness sphere. There is neither ignorance nor ending of ignorance, neither old age and death nor ending of old age and death. There is no suffering, accumulation [of afflictions], cessation [of suffering], or the path. There is neither wisdom-knowledge nor attainment because there is nothing to attain.

“Bodhisattvas, because they rely on prajñā-pāramitā, have no hindrances in their minds. Without hindrance, they have no fear. Staying far from inverted dreaming and thinking, they will ultimately attain nirvāṇa. Buddhas of the past, present, and future, because they rely on prajñā-pāramitā, all attain anuttara-samyak-saṁbodhi.

“Hence, we know that the Prajñā-Pāramitā [Mantra] is the great illumination mantra, the unsurpassed illumination mantra, the unequaled illumination mantra, which can remove all suffering. It is true, not false. Hence the Prajñā-Pāramitā Mantra is pronounced. Then the mantra goes:

gate gate pāragate pāra-saṁgate bodhi svāhā ||”

— Sūtra of the Great Illumination Mantra of Mahā-Prajñā-Pāramitā

Translated from the digital Chinese Canon (T08n0250)

Shorter Prajñāpāramitā Hṛdaya Sūtra

Bore Boluomiduo Xinjing (般若波羅蜜多心經)

Translated from Taishō Tripiṭaka volume 8, number 251

When Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva was practicing the profound Prajñāpāramitā, he illuminated the Five Skandhas and saw that they were all empty, and crossed over all suffering and affliction.

“Śāriputra, form is not different from emptiness, and emptiness is not different from form. Form itself is emptiness, and emptiness itself is form. Sensation, conception, synthesis, and discrimination are also such as this. Śāriputra, all dharmas are empty — they are neither created nor destroyed, neither defiled nor pure, and they neither increase nor diminish. This is because in emptiness there is no form, sensation, conception, synthesis, or discrimination. There are no eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, or thoughts. There are no forms, sounds, scents, tastes, sensations, or dharmas. There is no field of vision and there is no realm of thoughts. There is no ignorance nor elimination of ignorance, even up to and including no old age and death, nor elimination of old age and death. There is no suffering, its accumulation, its elimination, or a path. There is no understanding and no attaining.

“Because there is no attainment, bodhisattvas rely on Prajñāpāramitā, and their minds have no obstructions. Since there are no obstructions, they have no fears. Because they are detached from backwards dream-thinking, their final result is Nirvāṇa. Because all buddhas of the past, present, and future rely on Prajñāpāramitā, they attain Anuttarā Samyaksaṃbodhi. Therefore, know that Prajñāpāramitā is a great spiritual mantra, a great brilliant mantra, an unsurpassed mantra, and an unequalled mantra. The Prajñāpāramitā Mantra is spoken because it can truly remove all afflictions. The mantra is spoken thusly:

gate gate pāragate pārasaṃgate bodhi svāhā

The Heart Sūtra: The Womb of the Buddhas

Red Pine translation

The Heart Sutra: the Womb of Buddhas. Washington: Shoemaker & Hoard, 2004.

The noble Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva,

while practicing the deep practice of Prajnaparamita,

looked upon the five skandhas

and seeing they were empty of self-existence,

said, “Here, Shariputra,

form is emptiness, emptiness is form;

emptiness is not separate from form, form is not separate from emptiness;

whatever is form is emptiness, whatever is emptiness is form.

The same holds for sensation and perception, memory and consciousness.

Here, Shariputra, all dharmas are defined by emptiness

not birth or destruction, purity or defilement, completeness or deficiency.

Therefore, Shariputra, in emptiness there is no form,

no sensation, no perception, no memory and no consciousness;

no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body and no mind;

no shape, no sound, no smell, no taste, no feeling and no thought;

no element of perception, from eye to conceptual consciousness;

no causal link, from ignorance to old age and death,

and no end of causal link, from ignorance to old age and death;

no suffering, no source, no relief, no path;

no knowledge, no attainment and no non-attainment.

Therefore, Shariputra, without attainment,

bodhisattvas take refuge in Prajnaparamita

and live without walls of the mind.

Without walls of the mind and thus without fears,

they see through delusions and finally nirvana.

All buddhas past, present and future

also take refuge in Prajnaparamita

and realize unexcelled, perfect enlightenment.

You should therefore know the great mantra of Prajnaparamita,

the mantra of great magic,

the unexcelled mantra,

the mantra equal to the unequalled,

which heals all suffering and is true, not false,

the mantra in Prajnaparamita spoken thus:

“Gate, gate, paragate, parasangate, bodhi svaha.”

Sūtra on the Heart of Realizing Wisdom Beyond Wisdom

Translated by Kazuaki Tanahashi

Avalokiteshvara, who helps all to awaken,

moves in the deep course of

realizing wisdom beyond wisdom,

sees that all five streams of

body, heart, and mind are without boundary,

and frees all from anguish.O Shariputra,

[who listens to the teachings of the Buddha],

form is not separate from boundlessness;

boundlessness is not separate from form.

Form is boundlessness; boundlessness is form.

The same is true of feelings, perceptions, inclinations, and

discernment.O Shariputra,

boundlessness is the nature of all things.

Boundlessness neither arises nor perishes,

neither stains nor purifies,

neither increases nor decreases.

Boundlessness is not limited by form,

nor by feelings, perceptions, inclinations, or discernment.

It is free of the eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mind;

free of sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, and any object of mind;

free of sensory realms, including the realm of the mind.

It is free of ignorance and the end of ignorance.

Boundlessness is free of old age and death,

and free of the end of old age and death.

It is free of suffering, arising, cessation, and path,

and free of wisdom and attainment.Being free of attainment, those who help all to awaken

abide in the realization of wisdom beyond wisdom

and live with an unhindered mind.

Without hindrance, the mind has no fear.

Free from confusion, those who lead all to liberation

embody profound serenity.

All those in the past, present, and future,

who realize wisdom beyond wisdom,

manifest unsurpassable and thorough awakening.Know that realizing wisdom beyond wisdom

is no other than this wondrous mantra,

luminous, unequaled, and supreme.

It relieves all suffering.

It is genuine and not illusory.So set forth this mantra of realizing wisdom beyond wisdom.

Set forth this mantra that says:GATÉ, GATÉ, PARAGATÉ, PARASAMGATÉ, BODHI! SVAHĀ!

The Great Wisdom Perfection Heart Sutra

Translated by Norman Waddell

The Bodhisattva Free and Unrestricted Seeing practices the deep wisdom paramita. At that time he

clearly sees all five skandhas are empty and is delivered from all distress and suffering.“Shariputra, form is no other than emptiness, emptiness no other than form. Form is emptiness,

emptiness is form. And it is the same for sensation, perception, conception, and consciousness.

Shariputra, all things are empty appearances. They are not born, not destroyed, not stained, not pure;

they do not increase or decrease. Therefore, in emptiness there is no form, no sensation, no

perception, no conception, no consciousness; no eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, mind; no form, sound,

scent, taste, touch, dharmas; no realm of seeing, and so on to no realm of consciousness; no ignorance,

no end of ignorance, and so on to no old age and death, and no ending of old age and death; no pain,

karma, extinction, Way; no wisdom, no attaining. As he has nothing to attain, he is a Bodhisattva.

Because he depends upon the wisdom paramita, his mind is unhindered; as his mind is unhindered, he

knows no fear, is far beyond all delusive thought, and reaches final nirvana. Because all Buddhas of

past, present, and future depend upon the wisdom paramita, they attain highest enlightenment. Know

therefore that the wisdom paramita is the great mantra, the great and glorious mantra, the highest

mantra, the supreme mantra, which is capable of removing all suffering. It is true. It is not false.

Therefore, I preach the wisdom paramita mantra, preach this mantra and say:

GATE GATE PARAGATE PARASAMGATE BODHI SVAHA!”

The Maha Prajna Paramita Hrdaya Heart Sutra

Translation by Stephen Addiss with thanks to Stanley Lombardo

Avalokitesvara, the Bodhisattva of all-seeing and all-hearing, practicing deep prajna paramita, perceives the five skandhas in their self-nature to be empty.

O Sariputra, form is emptiness, emptiness is form; form is nothing but emptiness, emptiness is nothing but form; that which is form is emptiness, and that which is emptiness is form. The same is true for sensation, perception, volition, and consciousness.

O Sariputra, all things are by nature empty. They are not born, they are not extinguished; they are not tainted, they are not pure; they do not increase, they do not decrease. Within emptiness there is no form, and therefore no sensation, perception, volition, or consciousness; no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, or mind; no form, sound, scent, taste, touch, or thought.

It extends from no vision to no discernment, from no ignorance to no end to ignorance, and from no old age and death to no extinction of old age and death. There is no suffering, origination, annihilation, or path; there is no cognition, no attainment, and no realization.

Because there is no attainment in the mind of the Bodhisattva who dwells in prajna paramita there are no obstacles and therefore no fear or delusion. Nirvana is attained: all Buddhas of the past, present, and future, through prajna paramita, reach the highest all-embracing enlightenment.

Therefore know that prajna paramita holds the great Mantra, the Mantra of great clarity, the unequaled Mantra that allays all pain through truth without falsehood. This is the Mantra proclaimed in prajna paramita, saying:

Gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi svaha

Gone, gone, gone beyond, gone altogether beyond, Awake! All hail!

Prajñāpāramitā-Hṛdayam

The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom

edited by Edward Conze, translated by Ānandajoti Bhikkhu

PDF

Oṁ! Namo Bhagavatyai Ārya-Prajñāpāramitāyai!

Hail! Reverence to the Gracious and Noble Perfection of WisdomĀrya-Avalokiteśvaro Bodhisattvo,

The Noble Buddha-to-be Avalokiteśvara,gambhīrāṁ prajñāpāramitā caryāṁ caramāṇo,

while dwelling deep in the practice of the perfection of wisdom,vyavalokayati sma panca-skandhāṁs

beheld these five constituent groups (of mind and body)tāṁś ca svabhāvaśūnyān paśyati sma.

and saw them empty of self-nature.Iha, Śāriputra, rūpaṁ śūnyatā, śūnyataiva rūpaṁ;

Here, Śāriputra, form is emptiness, emptiness is surely form;rūpān na pṛthak śūnyatā, śunyatāyā na pṛthag rūpaṁ;

emptiness is not different from form, form is not different from emptiness;yad rūpaṁ, sā śūnyatā; ya śūnyatā, tad rūpaṁ;

whatever form there is, that is emptiness; whatever emptiness there is, that is form.evam eva vedanā-saṁjñā-saṁskāra-vijñānaṁ.

the same for feelings, perceptions, volitional processes and consciousness.Iha, Śāriputra, sarva-dharmāḥ śūnyatā-lakṣaṇā,

Here, Śāriputra, all things have the characteristic of emptiness,anutpannā, aniruddhā; amalā, avimalā; anūnā, aparipūrṇāḥ.

no arising, no ceasing; no purity, no impurity; no deficiency, no completeness.Tasmāc Śāriputra, śūnyatāyāṁ

Therefore, Śāriputra, in emptinessna rūpaṁ, na vedanā, na saṁjñā, na saṁskārāḥ, na vijñānam;

there is no form, no feeling, no perception, no volitional processes, no consciousness;na cakṣuḥ-śrotra-ghrāna-jihvā-kāya-manāṁsi;

there are no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body or mind;na rūpa-śabda-gandha-rasa-spraṣṭavya-dharmāḥ;

no forms, sounds, smells, tastes, touches, thoughts;na cakṣūr-dhātur yāvan na manovijñāna-dhātuḥ;

no eye-element (and so on) up to no mind-consciousness element;na avidyā, na avidyā-kṣayo yāvan na jarā-maraṇam, na jarā-maraṇa-kṣayo;

no ignorance, no destruction of ignorance (and so on) up to no old age and death, no destruction of old age and death;na duḥkha-samudaya-nirodha-mārgā;

no suffering, arising, cessation, path;na jñānam, na prāptir na aprāptiḥ.

no knowledge, no attainment, no non-attainment.Tasmāc Śāriputra, aprāptitvād Bodhisattvasya

Therefore, Śāriputra, because of the Buddha-to-be's non-attainmentsPrajñāpāramitām āśritya, viharaty acittāvaraṇaḥ,

he relies on the Perfection of Wisdom, and dwells with his mind unobstructed,cittāvaraṇa-nāstitvād atrastro,

having an unobstructed mind he does not tremble,viparyāsa-atikrānto, niṣṭhā-Nirvāṇa-prāptaḥ.

overcoming opposition, he attains the state of Nirvāṇa.Tryadhva-vyavasthitāḥ sarva-Buddhāḥ

All the Buddhas abiding in the three timesPrajñāpāramitām āśritya

through relying on the Perfection of Wisdomanuttarāṁ Samyaksambodhim abhisambuddhāḥ.

fully awaken to the unsurpassed Perfect and Complete Awakening.Tasmāj jñātavyam Prajñāpāramitā mahā-mantro,

Therefore one should know the Perfection of Wisdom is a great mantra,mahā-vidyā mantro, 'nuttara-mantro, samasama-mantraḥ,

a great scientific mantra, an unsurpassed mantra, an unmatched mantra,sarva duḥkha praśamanaḥ, satyam, amithyatvāt.

the subduer of all suffering, the truth, not falsehood.Prajñāpāramitāyām ukto mantraḥ tad-yathā:

In the Perfection of Wisdom the mantra has been uttered in this way:gate, gate, pāragate, pārasaṁgate, Bodhi, svāhā!

gone, gone, gone beyond, gone completely beyond, Awakening, blessings!Iti Prajñāpāramitā-Hṛdayam Samāptam

Thus the Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom is Complete

Linnart Mäll

Heart Sutra of Transcending Awareness

In: "Studies in the Astasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā and other Essays", Centre for Oriental Studies, University of Tartu, Greif, 2003; Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2005, pp. 96-101.

Edward Conze has said that a Mahāyāna sūtra can be completely understood only after working on it for thirty years. I would say that I do not agree with Conze. I think that even thirty years is not enough: Conze's later works do show that he has deepened his understanding. However, I need to cite Conze when I try to justify myself to my friends who accuse me of translating and publishing anything else except the Prajnāpāramitā texts, i.e. the treatises that I have been studying the longest. Still, their reproach is not completely justified since there are some things that I have published, e.g. the Estonian translation of the Vajracchedikā Prajnāpāramitā or the "Diamond Sūtra".

It is true, however, that I would now translate it in a slightly different way, and in ten years time, probably in another way. Whatever Conze says, I feel that the Mahāyāna sūtras can never be completely understood. Why? One of the reasons is that they already contain an inherent incomprehensibility; there is something there that directly provokes the reader to repeatedly pose new questions to the text. The Astasāhasrikā Prajnāpāramitā even admonishes the reader just like a real live teacher after a cascade of logical mazes and paradoxes: are you sure you are not puzzled or startled or doubtful or depressed or confused? If you are, do not read further! Contemplate, and only when you think it makes sense, then continue reading.

The Mahāyāna sūtras were first written down (I stress this word since although these sūtras are also based on the pan-buddhist oral tradition, awareness of the meaning of a written text is important in this case) in the 4th century after Buddha or the 1st century ВС. There is sufficient reason to think that the above-mentioned Astasāhasrikā Prajnāpāramitā certainly was one of the first if not the very first of the Mahāyāna sūtras. In any case, the earliest Mahāyāna sūtras are these whose titles contain the word prajnāpāramitā ('transcending awareness'). Approximately thirty of these were written over several centuries. Furthermore, the Prajnāpāramitā laid a foundation for hundreds of other Mahāyāna sūtras. If there were no Prajhāpāramitā, there would be no "Lotus Sūtra" (Saddharmapundarika), "Golden Light Sūtra" (Suvarnaprabhāsa), "Flower Garland Sūtra" (Avatamsaka) and many other sūtras.

The Prajnāpāramitā texts emerged at the time when Buddhist circles were arguing about whether "Buddha's word" was finally fixed after many canonical volumes (the Tripitakas in Sanskrit and the Tipitaka in Pāli) had been written. The majority answered: Yes, it is fixed finally and forever. However, some people found that what the Buddha has said and taught was not meant as the eternal dogmatic truth. The Buddha's purpose was to create in his students the ultimate state of mind that he had attained, rather than to proclaim abstract truths. Therefore the tradition cannot be aimed at maintaining and forwarding the so-called pure original text. You can only communicate what has been verified by the emergence of the similar state of mind in another person. But the teacher can only create a certain state of mind in his student if he takes into account the latter's individual traits. Therefore the Buddha must have given specific (rather than abstractly general) teachings to particular individuals and they in turn to their students who also were specific individuals, and so on. The authors of the Prajnāpāramitā saw the development of Buddhism in the first centuries of its history as follows (the scheme is simplified since I only mention one disciple in each generation, although even the first Teacher, Gautama Buddha, Šākyamuni, had many).

The Buddha tried to awaken the ultimate state of mind in disciple A. To do this, he gave the teaching a, the text of which was determined by his own state of mind and the disciple's predisposition. The disciple A became the teacher A and tried to awaken the ultimate state of mind in disciple B. Of course, he had to bear in mind the latter's special traits. Therefore he could not mechanically cite what he heard from the Buddha even if he remembered it word by word but had to adjust it for the disciple. As a result the teaching a was modified and became the teaching ab. The disciple В became the teacher В who had the disciple C, the teaching was transformed into abc , etc, etc.

The above scheme explains much about the development of Buddhism. It also explains why in the 1st century ВС when texts were first written down, there emerged quite a lot of canons belonging to different schools. It also explains why the Buddha who taught in the 6th and 5th century ВС (rather than the teacher А, В, C, etc.) is still seen as the main author of the texts placed in all these canons. The whole process that lasted for several centuries can be considered as a general text-generating mechanism started up by the Buddha. Indeed, all the schools agree that the first sūtra in the history of Buddhism was the Dharmacakrapravartana, which can be translated as "Starting up the Wheel of Dharma", and considering that dharma or the teaching primarily means a text, the title of the sūtra can quite unambiguously be translated as "Starting up the Text-generating Mechanism". This sounds somewhat modern but we should not forget that at a scientific meta-level the attempt to understand the inner essence of cultures through terminology that we can understand, is not only permissible but also necessary.

The majority of Buddhists, however, saw the development of Buddhism in a rather different way. They believed that the Buddha's "original" text was communicated from generation to generation in its "pure" form until it was finally written down. For them it was set in concrete and nothing could be added to it. All very wonderful but for the fact that this majority was divided into different schools with their own written canons which did not quite match the others. According to the Prajnāpāramitā scheme, this was supposed to happen, but the purist majority started arguing amongst themselves by using the touchingly primitive scheme also known in other religions: ""We" are right and all others, i.e. "they" are wrong." This must be the reason why the proponents of the Prajnāpāramitā started calling the majority "Hīnayāna", i.e. the 'Small Vehicle' that can only carry a small group. They named their own universal, pluralist and tolerant tradition "Mahāyāna" or the 'Great Vehicle'. It could be supposed that the schools of majority would still be arguing about them being right and the others being wrong if most of them had not simply ceased to exist. Only one of them - Theravāda - has survived due to the happy coincidence of many circumstances. Mahāyāna has become a truly worldwide religion, probably the only one in which numerous schools and traditions do not want to perish the others but accept others next to them, or inside them or even themselves inside others.

As I already said, Mahāyāna started from the Prajnāpāramitā. The first sūtras of this tradition were written in the 1st century ВС when the canons of Hīnayāna schools were also fixed in writing. However, the Prajnāpāramitā, unlike Hīnayāna, did not finish the production of texts at the level of sūtras. On the contrary, the Prajnāpāramitā sūtras declare that more sūtras will appear in the future. History has shown that the predictions of the authors of the Prajnāpāramitā have come true: the emergence of canonical Mahāyāna literature is largely dated as the period from the 1st century ВС to the 5th century AD.

It seems paradoxical that we do not know the authors of the Mahāyāna sūtras, although the process of their creation lasted for more than five centuries. They all start with the standard introduction: "Thus have I heard. Once Bhagavat stayed..." Moreover, many sentences in the sūtras are ascribed to Bhagavat (i.e. the Buddha) himself and even if he does not speak he sits next to the speakers either in a state of concentration (samādhi) or otherwise, encouraging the discussions of disciples by his presence. Could the sūtras be falsified, as proponents of Hīnayāna often accused Mahāyāna? Most probably not even from the point of view of modern textual critics, if we consider the idea of the "text-generating mechanism". The Wheel of Dharma was started up by the Buddha (Bhagavat) and later the mechanism simply continued working. Moreover, the initial sentence of the sūtras -"Thus have I heard" - can be interpreted as some kind of reservation: the Buddha's words are conveyed by another person.

Still, as I already said, this other or, rather, others (since there apparently were quite many of them) should not be seen as the authors of the Mahāyāna sūtras. The author is still the Buddha and the text-generating mechanism he started up. Interestingly enough, the Mahāyāna sūtras are in a way quite similar and this similarity justifies the above-mentioned. They are similar in terms of vocabulary and style and, most importantly, regarding their intellectual power and persuasiveness. In this respect they certainly differ from the works of Buddhists who lived in the same period and wrote under their own names. The writings of Nāgārjuna, Asanga, Vasubandhu, Ašvaghosa and others might have been more persuasive in terms of their logical structure, and their language might have been better but they lacked the special fluidity that the Mahāyāna sūtras possess.

The "Heart Sūtra" is one of the shortest Prajnāpāramitā texts. If you are not familiar with other sūtras, it might seem rather incomprehensible. However, it should still be read as one of the first, since the questions that it raises, or the semi-clarity that it induces, may urge a thinking reader to seek answers. Some of the answers can definitely be found in the Bodhicaryāvatāra by Šāntideva and even more answers in the Astasāhasrikā Prajnāpāramitā.

The scene of the activities of the sūtra is Rājagrha, one of the most important cities at the time of the Buddha. The Buddha must have stopped there quite often. This time the Buddha is surrounded by disciples: bhiksus (mendicant monks) and bodhisattvas (both monks and laymen who think not only about their own liberation but also about the liberation of all sentient beings). All bodhisattvas are characterized by compassion. The bodhisattva Avalokitešvara is the embodiment of compassion par excellence. It is not likely that he had a definite prototype in "real" life. Most probably, he was a generalized figure that emerged in the process of text-generation.

Avalokitešvara is asked questions by Šāriputra, a bhiksu who is well known from Hīnayāna texts and is apparently a historical person. However, it is important that the most intelligent Hīnayāna bhiksu here only asks questions. The bodhisattva Avalokitešvara (he also has another epithet, mahāsattva, meaning 'great being') is the one who teaches. What is he saying? He is saying that all dharmas are empty. But what are dharmas? In the most general sense, dharma is the text-generating mechanism that has already been discussed, the one that creates the ultimate state of mind. Dharma also is the ultimate state of mind itself and the text that is created by the ultimate state of mind. But in this sūtra, dharma does not mean so much a text as a whole, but rather a element of text or a minimum text or, in other words, the most significant terms used in Buddhist texts. The number of dharmas is different in different schools (70 to 140) but some of them coincide in all schools. I am not quoting the list of dharmas here. More important is that "all dharmas are marked by emptiness" (sarvadharmāh šūnyatālaksanāh).

What does it mean? It does not mean, as it is often believed, that dharmas do not exist and that they are illusory deceptive images. In fact, 'emptiness' (šūnyatā) means that dharmas or text-generating mechanisms, in this case basic Buddhist terms contain an infinite number of opportunities to fill them with different content. It means that, for example, the word rūpa ('form') is not a defined and forever fixed concept but, in the process of inner text-generating (mental activity), it can be filled with one or another or third or hundredth or thousandth meaning. In other words, in the whole process of thinking we should make sure that defined concepts are not too limited: although Buddhists have defined all basic terms and treat the definitions with great respect, all definitions are temporary, and relevant for one or another specific state of mind. This by no means implies that Buddhism avoids mental activity. On the contrary, taking šūnyatā into account enabled it to use extremely sophisticated logic. In this case, words, concepts, ideas or sentences are not prisons but provide a chance to implement what is really human (animals who, as Buddhists believe, lack abstract thinking, are obviously incapable of attaining ultimate states of mind).

Thus, "all dharmas are empty". Only a person whose mind is not defiled (acittāvarana) and whose consciousness is clear can fully understand it. This state of mind can be attained by reading the Prajnāpāramitā texts since one should rely on the "Transcending Awareness of bodhisattvas". 'Transcending Awareness' is the equivalent of prajnāpāramitā in English. It means the awareness that helps to overcome the ocean of samsāra. There is no reason to translate prajnāpāramitā as 'intuition', which, unfortunately, was done too often in earlier times. This would imply a connotation disparaging mental activity.

The Heart Sutra

prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya

Primary Resources for Studying the Heart Sutra

by

Jayarava Attwood

http://jayarava.blogspot.hu/p/prajnaparamita.html

Heart Murmurs: Some Problems with Conze's Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya

by Jayarava Attwood

Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies. 8. 2015: 28-48.

Horiuzi Palm-leaf Manuscript Heart Sutra (法隆寺 Hōryū-ji)

facsimile by "Autotype, London" - Buddhist Texts from Japan. (Anecdota Oxoniensia, Aryan series), 1881.

PDF: Prajñāpāramitā Hṛdaya Sūtra – Sanskrit / Chinese (Xuanzang) / English

Compiled by Shi Huifeng 釋慧峰 (aka M. B. Orsborn)PDF: Buddhist Wisdom Books

The Diamond Sutra & The Heart Sutra

Translated and explained by Edward ConzePrajna Paramita Hrydaya Sutra

Commentary — T'an HsuPDF: The Heart Sutra

Translated by Lu K'uan Yü [Charles Luk]DOC: The Heart Sutra

Commentary — by Seung SahnPDF: The Heart of Prajna Paramita Sutra with Annotation

Translated by the Chung Tai Translation Committee, June 2002.

From the Chinese translation by Tripitaka Master Xuan Zang, 7th CenturyPDF: Heart Sutra: A Comprehensive Guide to the Classic of Mahayana Buddhism

by Kazuaki TanahashiPDF: The Heart Sutra: A Chinese Apocryphal Text?

by Jan Nattier

The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Vol. 15, No. 2, 1992.PDF: Prajñaparamita Mantra (The Perfection of Wisdom Mantra)

PDF: Reading by heart: translated Buddhism and the pictorial Heart Sutras of Early Modern Japan

by Charlotte EubanksPDF: The Insight that Brings Us to the Other Shore

Translated by Thich Nhat Hanh (2014)PDF: The Heart of Understanding

Commentary — Thich Nhat Hanh

Sûtra du Coeur de la perfection de sagesse

La version chinoise la plus connue est la traduction de Xuanzang en 649 ap. J.-C. Il est le premier à lui donner le titre de Sūtra du Cœur. Selon la biographie rédigée par son disciple Huili (慧立), Xuanzang aurait appris le soutra auprès d'un malade au Sichuan en remerciement d'un bienfait et il l'aurait souvent récité durant son voyage vers l'ouest.

Traduction française sur le chinois : Jérôme Ducor

Lorsque le Bodhisattva Avalokiteçvara pratique la profonde prajñâ-pâramitâ [perfection de sagesse], il voit clairement que les cinq agrégats sont tous vides, et il dépasse toutes les souffrances.

- Shariputra! La forme n'est pas différente du vide, le vide n'est pas différent de la forme. La forme, c'est le vide; le vide, c'est la forme. Il en va aussi de même des sensations, des perceptions, des constructions et des consciences.

Shariputra! Tous ces éléments caractérisés par le vide ne naissent ni ne disparaissent, ne sont ni souillés ni pures, ne s'accroissent ni ne décroissent.

C'est pourquoi, dans le vide, il n'y a pas de forme, de sensation, de perception, de construction ni de conscience.

Il n'y a pas d'oeil, d'oreille, de nez, de langue, de corps ni de mental.

Il n'y a pas de forme, de son, de parfum, de goût, de toucher ni d'éléments.

Il n'y a pas de domaine de la vision, etc., ni de domaine de la conscience mentale.

Il n'y a pas ignorance ni suppression de l'ignorance, etc., pas de vieillesse-et-mort ni suppression de la vieillesse-et-mort.

Il n'y a pas de souffrance, d'origine, d'extinction ni de chemin.

Il n'y a ni connaissance ni acquisition.

Parce qu'il n'y a rien à être acquis, le bodhisattva s'appuyant sur la prajñâ-pâramitâ n'a pas d'empêchement en son mental.

Parce qu'il n'a pas d'empêchement, il n'a pas de crainte : séparé de toutes les méprises et pensées illusoires, il parvient au nirvâna .

Les buddha des trois temps obtiennent l' anuttara-samyak-sambodhi [parfait éveil insurpassable] en se fondant sur la prajñâ-pâramitâ .

Sache donc que la prajñâ-pâramitâ est la grande formule sublime! C'est la formule de la grande science. C'est la formule insurpassable. C'est la formule égalant l'inégalable. Elle supprime toutes les souffrances. Elle est authentique et non pas vaine. C'est pourquoi, j'expose la formule de la prajñâ-pâramitâ , formule qui s'expose ainsi :

Gate gate pâragate pâra samgate bodhi svâhâ

[Allé, allé, allé au-delà, allé entièrement au delà : Salut à l'Éveil!].

Le "Sūtra du cœur"

traduction de Catherine Despeux

Alors que l'être d'éveil Qui-contemple-les-choses-telles-quelles (chinois Guan Zizai, sanskrit Avalokiteśvara) s'adonnait à la profonde pratique de la perfection de sapience, il contempla et vit à la lumière de la sapience que les cinq agrégats sont vides. Il s'affranchit ainsi de toutes les souffrances.

Śāriputra, la forme est vacuité, la vacuité est forme : la vacuité n'est autre que la forme, et la forme n'est autre que la vacuité. Il en est de même pour la sensation, la pensée, la volition et la faculté de connaissance.« Śāriputra, toutes choses ont pour attribut essentiel la vacuité : elles ne sont ni produites, ni détruites, ni souillées ni purifiées, n'augmentent ni ne diminuent. En conséquence, Sāriputra, dans la vacuité il n'y a pas de forme, pas de sensation, pas de représentation, pas de volition ni de faculté de connaissance ; il n'y a pas d'œil, d'oreille, de nez, de langue, de corps, ni de mental ; il n'y a pas de forme, de son, d'odeur, de saveur, de tangible ni d'objet mental ; il n'y a pas de sphère visuelle, et ainsi de suite jusqu'à : il n'y a pas de sphère de la faculté de connaissance.

Il n'y a pas d'ignorance ni de fin à l'ignorance, et ainsi de suite jusqu'à : il n'y a pas de vieillissement et de mort ni de fin du vieillissement et de la mort ; Il n'y a ni souffrance, ni origine de la souffrance, ni fin à la souffrance ni voie menant à l'extinction de la souffrance ; il n'y a ni sapience, ni obtention, ni objet d'obtention. Comme il n'est rien à obtenir, l'être d'éveil, prenant appui sur la perfection de sapience, a l'esprit sans obstruction ; étant sans obstruction, il est libre de toute peur, et se dégage de toutes les distorsions de l'esprit et des pensées illusoires pour accomplir de manière ultime la grande extinction.

Les Eveillés des trois temps ayant pris pour support la perfection de sapience ont obtenu l'éveil parfait, complet et insurpassable. On sait ainsi que la perfection de sapience est un mantra divin, une grande dhāranī , le mantra suprême et inégalable, qui peut chasser toutes les souffrances, qui est réel et non illusoire.

Voici la formule : " Gate gatepāragate pārasamgate bodhi svāhā ". »