ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

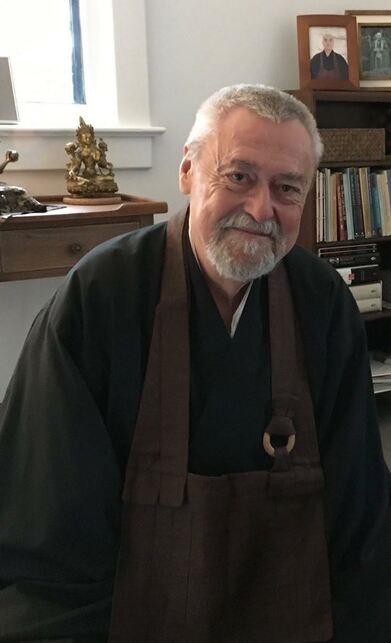

James Ishmael Ford (1948-)

Zeno Myōun rōshi

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Ishmael_Ford

http://www.jamesishmaelford.com/

http://obcconnect.forumotion.net/t537-myozen-delport

Unitarian Universalist minister named Zen master

http://www.uuworld.org/news/articles/1994.shtml

His Ordinations & Authorizations:

Shukke Tokudo (novice priest ordination), Oakland, California, 5 July, 1969, by Houn Jiyu Kennett, Roshi

Denkai/Denbo transmission (full ordination and authorization as a teacher), Mt Shasta, California, 2 May, 1971, Houn Jiyu Kennett, Roshi

Minister, Unitarian Universalist, Mequon, Wisconsin, October, 1991, by the Congregation of the Unitarian Church North

Ministerial Fellowship, Unitarian Universalist Association, 1991 (Final Fellowship in 1994)

Dharma Heritage (recognition as a senior teacher in North American Soto Zen), 2004, Clatskanie, Oregon, Soto Zen Buddhist Association. (In 2012, served as doshi or principal celebrant at the fifth Dharma Heritage ceremony)

Inka Shomei (final authorization as a koan Zen teacher), 6 August 2005, Needham, MA, by John Nanryu Ji'un-ken Tarrant, Roshi

James also holds ordinations within the independent sacramental tradition as well as several initiations within Inayat Khan Universalist Sufism.

Books

James Ishmael Ford, Zen Master Who?: A Guide to the People and Stories of Zen

Wisdom Publications, 2006

James Ishmael Ford and Melissa Myozen Blacker, The Book of Mu

Wisdom Publications, 2011

http://www.wisdompubs.org/book/book-mu

James Ishmael Ford, If You're Lucky, Your Heart Will Break: Field Notes from a Zen Life

Wisdom Publications, 2012

James Ishmael Ford, Introduction to Zen Koans: Learning the Language of Dragons

Wisdom Publications, 2018

Foreword by Joan Halifax

James Ishmael Ford, The Intimate Way of Zen: Effort, Surrender, and Awakening on the Spiritual Journey

2024

Content

Introduction

PART ONE

Before the Full Moon

1. Entering the Intimate Way (Oxherding 1)

2. Establishing a Practice

3. Vows as the Container for the Contemplative Life

4. Snakes and Ladders

5. Into the Way (Oxherding 2)

6. On Family, Home-Leaving, Resistance, and Love

7. False Friends and True

8. Coaches, Teachers, and Guides

9. Surprised by Joy (Oxherding 3)

10. The Masks of God

11. The Three Poisons

12. The Five Hindrances

13. Finding an Only True Way (Oxherding 4)

14. Doubt, Faith, and Energy

15. Vainglory

PART TWO

After the Full Moon

16. Integration of Practice and Encounter (Oxherding 5)

17. Noonday Devil

18. Wanting Something Else

19. The Distant Song (Oxherding 6)

20. Magic Lands

21. Love, the Four Abodes, and Near Enemies to Our Practice

22. Seeing the Cycles, Letting Things Be

23. View from the Mountain (Oxherding 7)

24. The Grace of the Real

25. False Gods and Better Angels

26. No Trace (Oxherding 8)

27. Theories of Mind and Body

28. Bodhidharma Sighed: Encountering the Dark Night

29. An Infinite Storm of Being (Oxherding 9)

30. Groundhog Days (Last Temptations)

31. Hearing the Cries of the World

32. Becoming the Fat Guy (Oxherding 10)

33. Mystery Piled upon Mystery

Acknowledgments

Notes

Blog

http://www.patheos.com/blogs/monkeymind/

PDF: Zen Lineage in the West

by James Ishmael Ford

Dharma Lineage

永平道元 Eihei Dōgen (1200-1253)

孤雲懐奘 Koun Ejō (1198-1280)

徹通義介 Tettsū Gikai (1219-1309)

螢山紹瑾 Keizan Jōkin (1268-1325)

明峰素哲 Meihō Sotetsu (1277-1350)

珠巌道珍 Shugan Dōchin (?-1387)

徹山旨廓 Tessan Shikaku (?-1376)

桂巌英昌 Keigan Eishō (1321-1412)

籌山了運 Chuzan Ryōun (1350-1432)

義山等仁 Gisan Tōnin (1386-1462)

紹嶽堅隆 Shōgaku Kenryū (?-1485)

幾年豊隆 Kinen Hōryū (?-1506)

提室智闡 Daishitsu Chisen (1461-1536)

虎渓正淳 Kokei Shōjun (?-1555)

雪窓祐輔 Sessō Yūho (?-1576)

海天玄聚 Kaiten Genju

州山春昌 Shūzan Shunshō (1590-1647)

超山誾越 Chōzan Gin'etsu (1581-1672)

福州光智 Fukushū Kōchi

明堂雄暾 Meidō Yūton

白峰玄滴 Hakuhō Genteki (1594-1670)

月舟宗胡 Gesshū Sōko (1618-1696)

徳翁良高 Tokuō Ryōkō (1649-1709)

芳巖祖聯 Hōgen Soren

石叟哲周 Sekisō Tesshū

隆孝楞洲 Ryukō Ryōshū

聯山祖芳 Renzan Sohō

物外志道 Motsugai Shidō

愚溪容雲 Gukei Yōun

嚇照祖道 Kakushō Sodō (1844-1931) [原田 Harada]

大雲祖岳 Daiun Sogaku (1871-1961) [原田 Harada]

白雲量衡 Hakuun Ryōkō (1885-1973) [安谷 Yasutani]

耕雲禅心 Kōun Zenshin (1907-1989) [山田匡藏 Yamada Kyōzō]

大龍貯潭暁雲 Dairyū Chōtan Gyōun (1917-2010) [Robert Baker Aitken]

南龍慈雲軒 Nanryū Ji'un-ken (1949-) [John Tarrant]

禅和妙雲 Zeno Myōun (1948-) [James Ishmael Ford]

佛山同生 Bussan Dōshō (1956-) [Dosho Port]

Fifty years a Zen Priest

by James Myoun Ford

https://www.patheos.com/blogs/monkeymind/2020/07/fifty-years-a-zen-priest.html

Fifty years ago, today, on the 5th of July 1970, I received shukke tokudo, also called unsui tokudo, ordination as a novice Soto Zen Buddhist priest in Oakland, California, from the Soto Zen priest Houn Jiyu Kennett.

In the back row from left to right Aubrey Thornton, Mark Daiji Strathern, Mokurai Edward Cherlin.

In the middle row James Etsujo (later Myoun) Ford, Joshua Jitsudo Baran and Lance Merritt.

In the front row Myozen Delport, Houn Jiyu Kennett & Steve Kozan Beck.Peggy Teresa Nancy Kennett was born in Sussex, England, in 1924. She studied medieval music at Durham University and later at Trinity College of Music in London. She was attracted to the Established church and wanted to ordain. But the misogyny of the times and with that an absolute bar on women ordaining turned her gaze in other directions.

In 1954, when she was thirty years old, she joined the London Buddhist Society led by Christmas Humphries. At first she focused her studies on Theravada Buddhism, reading everything she could as well as meeting different teachers and monastics that passed through the society. But after meeting a number of visiting scholars and teachers of the Mahayana, including D. T. Suzuki, her focus shifted to Zen.

In 1960, Koho Keido Chisan, abbot of Sojiji, one of the two principal training temples of the Soto school in Japan, visited as part of a tour of America and Europe. Peggy was put in charge of arranging the London part of his trip. He was taken with the now thirty-six year old Zen enthusiast, marking her intelligence as well as her competence. And he told her if she wanted to come to Japan, he would be happy to be her teacher.

It took two years to get her affairs in order. Then in 1962, she sailed to Japan. Interestingly, she paused in Malaysia where she was ordained a novice in the Chinese sangha by the Venerable Seck Kim Seng. There is actually a question whether this was as a novice or in fact a full Bhikshhuni ordination. Whatever, this was simply an interesting pause.

She soon arrived in Japan where she studied both with the abbot, and as her principal teacher his assistant Suigan Yogo. Yogo Roshi would eventually become the abbot of Sojiji, himself. The following year she was fully ordained and received Dharma transmission from both of her teachers. Reverend Kennett continued training and eventually was installed as abbess of a country temple, Unpukuji, in Mie prefecture.

In 1969 she obtained a charter to start a temple in London. She returned with two Western disciples, Mokurai Cherlin and Myozen Delport, stopping in California. The plan was for her to stay briefly in San Francisco to learn more about the wild success of the Shunryu Suzuki’s center. Once in California, and I imagine her thinking about London and England, where Roshi Kennett would always also be known as Peggy, and I wouldn’t be surprised the climate played a part, and, whatever, she decided to stay.

Before long she and her two senior students moved from the Zen Center into a flat on Potrero Hill. There she announced she was receiving potential students.

And I became Kennett Roshi’s first student in America. Although I feel it necessary to note that Josh Baran says it was he. However, I distinctly remember showing up on a Wednesday and he arriving the next day, on a Thursday. Some claim it was the other way around. But they’re wrong.

I’d been practicing Zen for a couple of years. I’d received basic instruction in Zen meditation from Ananda Claude Dahlenberg, a priest with Shunryu Suzuki, and I’d been sitting regularly with another of Suzuki Roshi’s priests, Mel Sojun Weitsman, at the Berkeley Zendo.

Somewhere along the line I decided I wanted to be a Zen priest. But I was young and callow and ill-educated. I’d dropped out of High School, joined the Marines, was discharged honorably enough, but early and without ever leaving California. I was working in a bookstore, smoking too much pot, and I had no sense of who I was, or what I really needed. San Francisco Zen Center, of which Berkeley was a branch at the time, didn’t really offer a path of ordination, and I certainly wouldn’t have been much of a candidate, if they had.

Kennett Roshi was happy to take me in. I spent every available moment at the little flat.

Before long she suggested my girlfriend and I move into the flat. We agreed. However, the roshi then insisted that we marry before we moved in. I felt trapped. I told my girlfriend I wanted to break up. She said she would kill herself. We married. Kennett Roshi officiated. And with that we moved into the temple.

My principal job with the nascent temple was to pay the rent. I left the bookstore in Oakland to become a shipping clerk at the San Francisco branch of Tiffany’s Jewelry Store.

Practice was intense. I began to lose everything. I’d been counting my breath. The roshi ended that. She said, just sit. Privacy was gone. I was married, but we didn’t have a private room. Time on my own or with my wife was gone. Somewhere along the line my hope ended. Then my doubt ended. Zazen. More zazen. Reading a bit. Lectures and classes. More zazen. It all drove me forward. It drove me inward. It focused everything on just sitting whenever possible.

The roshi then said she had to go to London to wind up her family affairs. She put her South African disciple Myozen Delport in charge, deciding to take Mokurai with her. If anything, the pressure of practice deepened under Myozen’s leadership. About a month later the roshi called and said she would not be returning just with Mokurai.

We rented a house across the Bay in Oakland. I found a job there driving a delivery car for a small printing house. When the roshi returned she brought a dozen people with her. Around that time we formally organized ourselves as the Zen Mission Society.

And it was there at the Oakland monastery, on the 5th of July 1970, along with five others. I was ordained an unsui, a “clouds and water” person, a novice Zen priest.

It was a tad shy of two weeks before I turned twenty-one.

Today. Fifty years later.

All I can think of is that poem by Ryokan.

Last year, a foolish monk.

This year, no change.

The Faith of a UU Buddhist

by James Ishmael Ford

I've been a Buddhist for more than thirty years. I've also been a Unitarian Universalist for

more than fifteen years. Since 1991, I've been a UU minister serving congregations in

Wisconsin and Arizona. It is from this perspective that I find myself reflecting on what it

might mean to be a Unitarian Universalist Buddhist.My mother was a fundamentalist Christian. My father was a Robert Ingersoll atheist.

Reflecting on this, I see that perhaps I was destined to become a Unitarian Universalist.

Or maybe a Buddhist. That blending of a deeply felt sense of spirituality with a fierce

devotion to reason could take one to either Unitarian Universalism or Buddhism. As it

turned out I found both.I remember a time not long after I left the Buddhist monastery that had been my home for

several years. I needed a new spiritual home where I would not be asked to deny my

previous experiences but where I could process those years of intensive monastic

training, and from where I could go forward in new directions.While I felt deep appreciation for the techniques of Zen meditation and the spiritual

perspectives I found at the core of Buddhism, I also felt a deep need to reconnect with my

Western religious roots. I visited a number of churches, but orthodox Christianity just

didn't work for me.Then one day, while arranging some old musty pamphlets at the used bookstore where I

was working, I came across a reprint of William Ellery Channing's Unitarian

Christianity, also known as the Baltimore Sermon. I remember so clearly standing at the

pamphlet rack reading through it and feeling a tingle of recognition run down my spine. I

thought, "This is a kind of Christianity that makes sense."That Sunday I attended the local UU church. I quickly saw that there had been some

movement away from Channing's faith. But I was even more excited by what I did find.

During the coffee hour following the service some members introduced themselves to me

and we talked. Eventually one of them asked what brought me to their church.I said that I was a Buddhist although I had a great respect for the Christianity of my

childhood and that I was looking for a spiritual home that would allow my continuing

quest. When I was asked what I meant by "Buddhism," I briefly outlined my belief that

the human condition is marked by disease, dissatisfaction, angst. There is some

fundamental sadness to our human condition.The Buddha examined this apparently universal human experience closely. He came to

believe this pervasive unrest occurs as a natural consequence of our human

consciousness. Looking at his analysis as a modern Westerner, I would frame what he

said in the following way: We seem to have emerged as animals that can divide the world

with our minds. Perhaps it starts with the ability to distinguish between not-me and me.

Perhaps it is even more fundamental, the on and off of our firing brain synapses.

However it comes about, this dualism is the source of human creativity and has made us

the dominant species on this planet. But this way of engaging the world also has a

peculiar side effect-we fall in love with the world that is created by our own perceptions.

We desperately want that world to be complete, permanent, and real.But as the Buddha observed, our grasping after permanency, for our loved ones and for

ourselves, is doomed. The universe and everything in it, including you and me, are in

flux. And what each of us perceives as "me" is actually a composite of many

consequences. They will fall apart at some point to reshape in new ways. Change is the

rule, and nothing is exempt.The Buddha asserted, and I've come to believe, that as we cling to what is passing as if it

is permanent, we find that pervasive angst, the terrible sadness that seems to live within

our human hearts. But there is good news-we don't have to suffer this way. The Buddha

outlined a "middle way" to insight and peace.Essentially this middle way has three parts: meditation, morality, and wisdom. Meditation

is a spiritual technology, wherein we closely examine without judgment everything,

every thought, every emotion, as it rises and as it falls. Morality is a way of harmony in

the universe and among our fellow creatures. Wisdom is what emerges out of these

practices of presence and harmony.As I spoke to those UUs so many years ago, one said, “Except for meditation, what you

describe sounds like a Unitarian Universalist perspective” and suggested that Unitarian

Universalists might be even better at “seeking ways to live in harmony” than Buddhists,

especially when they manifest this quest as a concern for social justice.My new friends went on to suggest that a Buddhist would find similar perspectives in all

the currents of contemporary Unitarian Universalism, particularly in religious humanism.

But there also seem to be commonalities between the "liberal Buddhism" I described and

the liberal Christianity, Judaism, and earth-centered faith embraced by many other UUs.

And over the years, I've come to believe they were right.This blending of Buddhism with Unitarian Universalism began with nineteenth-century

Transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Unitarian

Elizabeth Palmer Peabody translated the first Buddhist text into English. Buddhist

reflections about the nature of the world have continued in Unitarian Universalism and

have become especially dynamic in recent years.Western Buddhists of many different schools who are now seeking ways to integrate their

experiences of East and West are discovering Unitarian Universalism as a true home.

Increasingly Buddhists have been integrated into this great Western tradition as a rich

variation on our liberal religious theme.Certainly we UU Buddhists have found many treasures. Possibly the most important

offering of Unitarian Universalism is religious education for our children. UU religious

education programs are perfect for Western Buddhists who want to raise children with

some knowledge of our ancestral religions but also with a world religion perspective and,

of course, with an openness to Buddhism.Many Western Buddhists have been looking for ways to bring our perspectives into the

world in a more engaged way. My first UU friends were right. Unitarian Universalism

has long been committed to justice and social activism in ways that make sense to many

Western Buddhists. Here we found both possibilities for enriching our lives and the lives

of those we care about.And, I'm pleased to point out, we Western Buddhists also come bringing gifts. Probably

the greatest gift we bring to Unitarian Universalism is meditation. There are a host of

practices that might be useful to Unitarian Universalists. Among these are concentration

disciplines and the powerful practice of Metta, loving kindness. I believe the most

important are the practices of pure attention-Vipassana, Zen, and Dzog-chen. Each is a

variation of the original disciplines taught by the Buddha and his immediate followers.

Each has to do with simple and plain attention.Out of this paying attention, bare attention, just noticing, generations of people have

found a way through the traps of our dividing consciousness to see that we share a

common ground of being. One teacher puts it this way: We are each of us different, stars

and people, flies and dirt. But we all belong to the same family. We have a single family

name. And that name is the great silence. Sometimes it is called sunyata, emptiness.

This is an emptiness that includes all things. We are unique but we are also all of one

family. Here we find an ethic that supports Unitarian Universalist longings for moral

choice and social justice.We Western Buddhists bring a host of perspectives to Unitarian Universalism. Our

perspectives might be as scholarly as investigations of ancient texts like the Lotus Sutra

or the rigorous logic of the Therevada or as simple as faithful chanting of one of the

revered mantras from China or Tibet. We represent the full range of Asian Buddhist

possibilities, blending here in the West in new and exciting ways.As with all faith traditions encompassed in Unitarian Universalism it is impossible to

describe Unitarian Universalist Buddhism in terms of any one perspective. It is a rich and

varied thing we bring into Unitarian Universalism. And the joy for me is that, even as I

am transformed by my life as a Unitarian Universalist, I am beginning to see ways in

which Unitarian Universalism is transformed by our Buddhist presence.No one knows where this meeting of East and West in our Unitarian Universalist

congregations will lead. Certainly, only time will tell. But the journey is already

wonderful and filled with splendid possibilities.James Ishmael Ford is a Unitarian Universalist parish minister as well as a teacher in both the Soto and

Harada/Yasutani lines of Zen. He is the author of This Very Moment: A Brief Introduction to Buddhism and

Zen for Unitarian Universalists.

Holding the lotus to the rock: Reflections on the future of Zen in the West

by James Ishmael Ford

The Schools

It is still much too early to say that Zen is irrevocably established in the West. Decades, possibly centuries must pass before we will know the answer to that question. But more than thirty years have now passed since the first western Zen centers were established, and a fair amount of water has passed under that proverbial bridge. We are now witnessing the emergence of a generation of western born, and frequently entirely western trained Zen teachers. So now, in 1997, with the retirement of Robert Aitken Roshi, widely acknowledged as the dean of these western Zen teachers, this is perhaps a particularly appropriate time to begin to reflect on the great questions of whither and how of Zen in the West.

Deeply rooted or not, western Zen is well on its way to being established in Europe, and also now has active expressions in Australia and South America. In addition to which, the first tentative steps toward establishing an African Zen have now been made. But, at this point the greatest number of centers and the greatest focus of western Zen does seem to still be in North America and particularly the United States. So, the emerging Zen of Turtle Island will remain the focus of this essay.

Until recently the Japanese-derived Soto schools have been the most active in establishing centers in the Americas. At the same time the ethnic Japanese temples have not proven to have had much direct influence in the shaping of this western Soto beyond the very important act of bringing several of the more significant teachers such as Shunryu Suzuki Roshi and Hakuyu Maezumi Roshi as their temple priests. However, as these teachers attracted European descent students, they moved out of their temples and established independent centers. As with the shape of the dharma in the West in general, there remains a great divide between the ethnic Asian Buddhist communities and those with European (and, to a much smaller degree, African,) descent.

Despite its being the first Zen sect to have a presence in the West, the Rinzai school has not so far been particularly successful at taking root here. Perhaps the scandals around Eido Shimano Roshi and Walter Nowick Roshi, and the untimely death of Maurine Stuart Roshi, have particularly stricken the early Rinzai work. The principal exception to the low profile of western Rinzai, has been Joshu Sasaki Roshi, who while choosing to largely work in isolation from the larger western Zen community, has created a network that in all likelihood will survive him. This is not to write off the Rinzai tradition as a western expression. There are now also a new crop of teachers, both Japanese and of European descent, who will continue to offer the Rinzai perspective in coming years.

Koan Zen has primarily found its western expression in the Harada/Yasutani lineage, which is a lay-led Soto derived school offering a full koan curriculum. The Diamond Sangha and Hakuyu Maezumi's White Plum Sangha have worked hard to preserve and transmit this significant tradition. The Diamond Sangha has done this as a lay-led school and the White Plum within the Soto priestly tradition. Also, worth noting in this regard, is Roshi Philip Kapleau, who has transmitted an abridged form of the Harada/Yasutani koan curriculum through the various centers established by his students.

For the most part Chinese Zen (Ch'an) has been limited to ethnic Chinese communities. Western students who have an interest in Chinese Zen have had to adapt to Chinese cultural patterns, such as has been the case with the various students of the late Tripitaka Master Hsuan Hua. The result of this has been a tendency to isolate direct Ch'an influence from the larger western culture. The principle exception to this tendency has been Ch'an Master Sheng-yen, who has worked extensively with western students.

However, through the astonishing work of Zen Master Seung Sahn we are guaranteed that western Zen will not simply reflect its Japanese expressions. In fact while being a relative latecomer here, today the Chogye derived Kwan Um School of Zen is probably the widest spread of the Zen lineages in the West. Institutionally, this certainly is true. To a lesser degree this has also been true of the work of the Korean Zen Master Samu Sunim. No doubt Korean derived Zen (Son) is a clear alternative to Japanese derived Zen for any westerner wishing to explore the possibilities of Zen practice.

Also in this manner of alternatives to Japanese Zen expressions, we need to be mindful of the Order of Interbeing established by the peace activist Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh. Through the centers established by his many students this Vietnamese derived Zen (Thien) community also frequently bridges to the western Vipassana community--an emerging western Buddhist school with roots in the Theravada traditions.

Indeed, we are beginning to see a cross fertilization among most of these schools, as well as experiencing influences from other Buddhist groups, particularly that emerging western Vipassana school. While what all this will lead too is far from certain, it seems certain we are witnessing a general openness to eclecticism and syncretism among western Zen practitioners that brings with it both great possibilities for depth as well as many dangers along the way.

Who Belongs To The Western Zen Sangha?

After a great flourishing in the sixties and early seventies there appears to have been a drop off in involvement in western Zen. In part this may have to do with the changing demographics of North American culture. The so-called "Baby Boomer generation" that birthed the hippie movement, expressed a great hunger for spirituality that Zen seemed to successfully feed. The next generation to come along, the so-called "Generation X'ers," have not to date shown such a great interest in matters spiritual. Although as we approach the millennium, this well may be changing.

Another possible reason for this apparent leveling off of interest in western Zen may lie with the various institutional scandals, mostly around sexual matters, which have shaken contemporary western Zen communities. It is hard to say. But, certainly few western Zen communities and centers have made it through unscathed to this date.

Whatever the reasons for the leveling off of Zen interest, at this time most centers have been aging--where in the nineteen sixties and seventies the average age of students seems to have been in their very early twenties, now the average age seems to be the late thirties and forties, if not older. Practitioners are overwhelmingly of European descent.

Many, probably most, western Zen practitioners come from the more affluent classes. A significant majority have university training, a good number with professional degrees. At the same time there seems to be a trend toward underemployment among active Zen students. With the majority now in their mid-thirties and forties, a general preoccupation with work, professional training and advancement, child rearing and retirement, seems to be rising.Western Zen Teachers

Western Zen teachers in general combine a charismatic, almost shamanistic character, together with a serious commitment to "transmission," formal authorization within traditional lineages. For the most part they have spent years in training, often within semi-monastic situations. A number have spent some time in Japan or other East Asian countries, although few are conversant in Asian languages. The focus of their training has almost exclusively been meditation, and broader knowledge of Buddhism among these teachers is very uneven.

As with Zen students in general, questions of ordinary life, family and profession, have begun to rise. The shape of their professional lives has been varied. There are a few "super stars" who attract financial support and sometimes write well selling books, as well as lead profitable workshops. Many function in a monastic or more frequently semi-monastic state, living hand-to-mouth, as their communities barely support them. This marginal financial life is the more common reality for western Zen teachers. Here we find constant concerns over such things as health insurance, costs of educating their children (in the case of the semi-monastic), and retirement.

An interesting variation on the monastic state are the Catholic religious; monks (usually also priests) and nuns (the majority Jesuits and Maryknolls), who have devoted themselves seriously to the dharma, and who frequently have received formal authorization as Zen teachers while continuing to be supported by their Catholic Orders. These include such individuals as Patrick Hawk Roshi and Robert Kennedy Sensei.

Other western Zen Buddhist teachers have returned to school and have acquired professional status in some other occupation. Frequently this is within the mental health field--many have MSW's, or MA's and PhD's in psychology, such as John Tarrant Roshi and Zen Master George Bowman. Others are nurses, such as Zen Master Bobby Rhodes, or other health providers, such as Jan Chozen Bays Sensei who is a medical doctor. Most seek occupations that allow sufficient free time to lead the retreats that lie at the heart of Zen training. Here they frequently work professionally part-time and as Zen teachers part-time. Financial concerns continue to press them in their private and public lives.The Centers

For the most part western Zen centers have functioned primarily as "schools" or "academies." Here support for the center comes from dues and fees from retreats. The tradition of "training periods," as well as the more concentrated times of sesshin or yong myong jong jin, have lent themselves comfortably to the ebb and flow of a quasi-academic schedule. In a principle variation on this theme those groups focusing on koan study provide retreats as what have become "kensho factories." Here the emphasis is even more strongly on retreats and all leadership leads through the experience of "realization," or "insight," most usually experienced within these settings. In neither case has there been any kind of organic growth of "communities" as would be generally recognizable by westerners.

A few monasteries have also been established. However, most of these have followed the Japanese tradition of supporting "married monks," (The convention is to refer to both male and female monastics as "monks.") where men and women (and in most centers, same sex couples, as well) may pair off, but otherwise live recognizably monastic lives. Tassajara, Green Gulch, Zen Mountain Monastery and other semi-monastic centers are genuine adaptions of the institutions of their Japanese forbearers, and are fascinating contemporary experiments in finding the shape of a western Buddhist community.

The raging question for many western Zen students, however, has been how to raise their children. And from that question, how to move beyond a narrow focus on individual realization and toward something that can genuinely be called community. Indeed, the questions of community seem to be the strongest concern for many western Zen practitioners at the end of the twentieth century.

In this regard a few western Zen students (and a couple of teachers) have found the Unitarian Universalist churches particularly inviting. Now, with the formation of a Unitarian Universalist Buddhist Fellowship within the Association, the possibility of a hybrid connection looms large.

Many however, simply do not wish to reconnect with a western church, however liberal and open to Buddhist insight it may be. Certainly there are substantial problems in making a connection with an already established institution with its own standards for religious leadership. For those who do not want such connections, the Zen center becomes increasingly important as a focus for a sense of community, and by this usually understood in some sense of "church" or "synagogue." Here the problems surrounding the needs for a basically egalitarian community comes into conflict with the charismatic and more-or-less authoritarian nature of Zen teaching.

Some have attempted to completely eliminate the division between teachers and students. This sometimes leads to the separating of Zen from Buddhism. Ironically, this is less the case for the Catholic practitioners, and not at all the case for those involved in Unitarian Universalism. But, it is a growing edge of western Zen. One important western teacher inclined in this direction is Charlotte Joko Beck Sensei. At an even more extreme edge, Tony Packer has worked hard to create a completely egalitarian community, dropping even "Zen" together with ''Buddhist." How this will turn out is still very much an open question.

At this point no centers seem to have been completely successfully in addressing the question of community. Indeed, this may be the great "koan" of institutional western Zen as we look toward the twenty-first century. How do we move beyond establishments focused exclusively on individual realization or depth to institutions that allow the fullest expression of human personality and life? How do we come to a western Zen Buddhist church while remaining faithful to our individual quests for insight and depth?

Of course a fair number of us don't want any such thing. The idea of "church," whether within Unitarian Universalism, or as a new independent Buddhist activity, is repugnant for many called to the practice of Zen. Many western Zen Buddhists simply do not want any institutions beyond the bare necessity allowing teacher student relationships. Here American anarchic and libertarian tendencies meet with Taoist inclinations. This remains a strong and problematic perspective within contemporary western Zen centers.

When one looks at the history of attempts at establishing broad based western Buddhist institutions, there is little to give encouragement. For instance, the history of western Jodo Shinshu has a sobering lesson here.

The Buddhist Churches of America, established first as a Japanese ethnic enclave in North America, has almost from its foundation experienced decline. Second and third generation members seem to abandon the Buddhist Church for Methodism at an astonishing rate. Despite a recent inflow of a small number of European descendant members and ministers, they no where near match the numbers of those leaving this body. This one grand experiment in establishing a western Buddhist church seems unfortunately on its way to being a failure.

And so, there appears to be no consensus on where we should be going as western Zen Buddhists. The only shared emotion among those of us who have found our lives shaped by Zen is concern.So, Whither and How?

As western Buddhists we have several options facing us. In all probability we will try every one of them and several others into the bargain. Of course, time only will reveal which if any will bear fruit.

One option is to treat Zen practice as an amateur activity. Here I mean amateur in its highest sense, as an act of love. Both teachers and students work in other trades or professions for their livelihoods, and gather together for regular sitting and sponsor retreats as frequently as possible. This is a genuine possibility. It is also defacto what many of us are already doing. The problem here is that this does not allow the transmission of a Buddhist culture to our children or to the larger society, nor a fair way for our teachers to make a living in their chosen work.

In some ways this is our default choice. It is what is mostly happening. But, if this is our option, then we probably really should pursue connections with the Unitarians, a broad and generous people who will allow us to raise our children as identified Buddhists, while providing a frame for communal raising of children, as well as the many other necessary activities of a genuine spiritual community.

Another option is to professionalize our centers. This would mean clarifying the nature of religious leadership within our sanghas, and probably require additional training beyond mastery of the techniques of meditation for our teachers. Here we would also need to develop some form of regular public celebration or worship, such as puja, probably additionally focused on a type of sermon; as well as providing formal religious education programs for children and adults; in addition to the many other activities of contemporary religious communities.

Here we would without a doubt be establishing "churches." As there are many additional requirements for our priests, it would also require decent financial support for them as professional leaders. Of course, in every case, it is starting from scratch. There are no generally accepted seminaries for Zen priests. All current training is tutorial. And as we've already discussed this training is now focused almost exclusively on meditation. Nor is there any existing "denominational" structure to assist in the financing of buildings and the credentaling of religious professionals. This is possibly the most difficult of our possible directions.

Another option is reclaiming the monastic focus of traditional Buddhism, and generally reserving religious leadership to monks and nuns. Once again it requires the active support of a core leadership, in this case committed monastics. In some ways this is a variation on the professional priest option, although it more closely conforms to classic Buddhist models. I believe that for this to work, to attract sufficient financial and moral support, it probably would require a more stringent monasticism based in the traditional Vinaya than the semi-monastic tradition that for the most part we are currently familiar with. On the other hand enforced celibacy is a thorny issue in our times, and the sexual hypocrisy of many monks is a scandal in the waiting. We've long since learned we western Buddhists don't tend to do sex well.

Whether we end up with one of these institutional structures, create hybrids of several, or go in entirely new directions, there is little doubt that we live in, as the Chinese curse goes, interesting times. I believe we stand at a critical time in the development of a western Zen. The choices we make in the next few decades may well determine whether a western Zen actually takes deep root in our native soil and flowers. So, it is time for us to begin seriously discussing our options, and to consciously pursue the development of the dharma in the West. I have little doubt the future of Zen in the West is in our hands. It is an awesome responsibility. While I remain optimistic, I find I pray we are up to it. The happiness and welfare of many depend upon our choices and our actions in these rich and dangerous years.

A NOTE ON LIBERAL BUDDHISM

James Ishmael Ford

In his introduction to Stephen Batchelor's 1983 book Alone With Others: An Existential Approach to Buddhism , renowned western Buddhist John Blofeld described the book as "magnificent" and "inspiring." He then added how "the exposition is not intended to be exhaustive, as too much and too varied detail might mar its impact. Hence there are some important omissions such as the operation of karma and the concept of rebirth, both of which are crucial components of the Buddha Dharma."

Fourteen years later Batchelor published his reflections on karma and rebirth in his controversial broadside Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening . Blofeld had died a decade before, so we will never know with certainty what he would have thought of this analysis which was in fact a radical departure from traditional expositions of the Buddha Way. It is unlikely the old Buddhist scholar and practitioner would have been happy.

In this book Stephen asserted "The idea of rebirth is meaningful in religious Buddhism only insofar as it provides a vehicle for the key Indian metaphysical doctrine of actions and their results known as ‘karma.' While the Buddha accepted the idea of karma as he accepted that of rebirth, when questioned on the issue he tended to emphasize its psychological rather than its cosmological implications."

As he developed this argument Stephen was presenting a modern, rational and secular vision of Buddhist teachings. A detailed consideration of Stephen's particular understanding of the Dharma lies beyond the scope of this reflection. But he is one of the first to systematically present perspectives held, often unconsciously, by many, possibly most contemporary western Buddhists.

What we find here, I suggest, is the meeting of east and west, of our underlying western rational and humanistic perspectives encountering the Dharma, challenging, being challenged and ultimately synthesizing into a new Buddhism. As one begins to look closely it becomes very hard to ignore the many assumptions held by the majority of western Buddhists that are different, sometimes by shades, sometimes radically, than those held by what might be called traditional Buddhists.

Maybe this can be framed more helpfully by saying there is a new Buddhism emerging, a Buddhism quite different from the traditional Buddhisms of east and south Asia. These shifts in assumption are as substantive as were those of Nagarjuna from what was taught before him, and many of these shifts are of great value. As such, they deserve to be noticed.

The assumptions of this new Buddhism are so pervasive among western Buddhists and among popular western Buddhist writers in particular, it is actually possible to not notice. And, of course, what we don't notice about ourselves is the most dangerous part of who we are. It can be profoundly misleading when, as is often the case in western Buddhist - and especially within the western Zen communities to which I belong- the claim is that one is transmitting an a-historical path, the once and future way of awakening, unchanged from when the teachings were first delivered from the mouth of the Buddha himself.

Donald Lopez, in his preface to A Modern Buddhist Bible: Essential Readings from East and West observes the seduction for new movements seeing themselves as a return to the pure ways of the traditions and the original teachers. This has been the case for many who hold contemporary Buddhist views, seeing themselves, truthfully ourselves, as returning to an original Buddhism and its tenants. For instance our appeal to the summation of the Four Noble truths, which like many other contemporary commentators I've used as a foundational statement of what Buddhism teaches, is in fact something of an innovation--not an emphasis commonly found in the teachings of traditional Buddhists.

Bhikkhu Bodhi, a western Buddhist monk - and a critic of both Stephen's book and our contemporary Buddhist movement - summarizes several tenants of the phenomenon, which he calls "Western Buddhism." As many of these perspectives are in fact held by some Buddhists of just about all traditional schools, (including, as some suggest, the current Dalai Lama) probably Donald Lopez's "modern Buddhism" is a better term.

There is much truth in the term "modern" particularly if one doesn't confuse that term too closely with "contemporary," as this new Buddhism has roots that go back more than a century. However, I'm inclined to find people do confuse modern and contemporary, so I find the term "liberal Buddhism" most generally appropriate as a description for this emerging and pervasive perspective.

Bhikkhu Bodhi notes three particular elements marking this liberal Buddhism. One is a shift from monastic to lay life as the "principal arena of Buddhist practice." Second, there is a significantly "enhanced position of women" in this newer Buddhism. And very important, here we also find "the emergence of a grass-roots engaged Buddhism aimed at social and political transformation." However, underlying all this, the Bhikkhu suggests, and perhaps even the most significant of the shifts, is a fourth element, often missed by those who've noticed and commented on this phenomenon.

This is a pervasive secularization of the Buddha way. As it is so foundational, I think we need to start with a reflection on that least examined assumption, the trending of liberal Buddhism to secularism. Let me cite one example. Most contemporary Buddhists particularly the Buddhists of south Asia tend to embrace what I would have to call a scientific rhetoric. This perspective sees Buddhist meditation disciplines as well as the teachings in general as "scientific." Of course this is not true.

There is no sense of "falsification," a possibility that if one does the practices and does not achieve liberation, then Buddhism is proven false. Rather, the adherents of this perspective are vastly more likely to say that one has simply not done the practices correctly. And some form of falsification is necessary in any scientific endeavor. Without this we're really talking about scientism, the upholding of an image of science as an icon, sometimes as an idol, but not in any significant sense, science.

The seed of this appeal to science for justification is twofold. One is the desire to be up to date, current, modern. This particularly had appeal in the nineteenth century when Buddhists were first asserting their insights as equal to or perhaps better than those offered by western religions. But the more significant reason for this embracing of a "scientific" assertion, is that Buddhism is profoundly empirical. Buddhist insight is based within experience, and Buddhist philosophies and psychologies all flow out of reflecting on those experiences. So, while empiricism is not science, it is the mother of science, and one can see how easily the claim can be made.

While this inclination to see the Dharma in scientific perspectives births in one of the traditional Buddhist schools, it continues to pervade much of today's liberal Buddhism. Appeals to contemporary physics as "proof" of some aspect of Buddhist doctrine or another is fairly typical of liberal Buddhism. Here, I might add, we find some real shadows, a whole collection of logical fallacies, starting with that old chestnut "appeal to authority."

And the other (and in some ways, more dangerous point) is that an unconscious scientism also inclines us to the lure of reductionism. This is also, I think, the great shadow of secularism. Here Buddhism becomes a nostrum for improving self-esteem or a tennis game or getting an edge in business or war. Here we find the danger is that of Heinrich Schliemann, the amateur archeologist who when seeking Homeric Troy appears to have dug right through that level, destroying forever the city he so desperately sought.

Still, while shadowed, as with many things, this perspective is not without value. Out of this broad inclination to identify with the ideals of science, we find the willingness for liberal Buddhists to see the disciplines studied within scientific institutions. At first this was mostly in the realm of bio-feedback studies. While these undoubtedly have some value, they also tend to suggest the study of a horse through an examination of its feces. More recently there have been investigations of the relationships between meditation disciplines and various meditative states and neurophysiology. This is, I suspect, a harbinger of more serious and possibly more profitable examination of the meeting of Buddhist practice and psychology.

Continuing to explore the underlying assumptions of "liberal Buddhism" and its secular sense and how it plays out there is a profound shift toward lay practice. Here we particularly see some of the contours of western Zen, with its shift from Zen monastery to Zen center as the normative institution. Here we also encounter so much of the liberal Buddhist perspective. For instance, anyone who visits several western Zen centers finds women at every level of leadership in nearly all these institutions. And related to that, openly gay and lesbian people are almost uniformly accepted in these centers, also often in leadership positions. This is all unheard of in the east.

I think these shifts are significant and need our attention. Closely connected to this shift to centers of practice and the inclusion of women and homosexual persons in the life of western Buddhist communities is the central importance of Bodhisattva ordination. This is a significant shift in what is seen as normative ordained Buddhist leadership and it helps in the development of our contemporary western forms of liberal Buddhism.

Historically Buddhism has been led by vinaya monks, men who have taken the two hundred and fifty monastic vows associated with the order founded by Gautama Siddhartha. While there is a tradition of nuns, from the beginning women were only reluctantly allowed admission to the ordained order. This reluctance has taken shape in any number of restrictions, which has included a notorious set of additional rules where, among other things, nuns must first take their vows in their own community and then repeat the vows in front of the male order. From that point on, the most senior nun of whatever character or commonly understood wisdom is considered junior to the youngest and least insightful monk. Very telling.

While the Buddha is said to have allowed for the modification of "minor" rules, no group of monastics have ever been able to agree on what those minor rules are , and so, twenty-five hundred years later, there have still been no modifications of this gender inequity. In many places it has only gotten worse. In many Buddhist countries the vinaya order for nuns has died out, and women who wish to take up the monastic rule are not even considered proper nuns.

Many liberal Buddhists might raise reasonable objections to this state of affairs, but it is important that they not miss the point. Such observations about the limitations of vinaya ordination are not to say one cannot gain everything necessary within vinaya monastic life. And this is true for both women and men, gay and straight.

Without a doubt the traditional monastic life continues as a valuable option. This is the tradition that has fostered and carried our insights. To forget that would be to commit the sin of ingratitude. Arrogance is one of the greatest dangers on the spiritual way, and for our contemporary lay-oriented and feminist inspired Buddhism to dismiss the many gifts of the vinaya community would be a great loss not only for us but for future generations.

As suggested, alternatives to monastic ordination have revealed themselves. Through a peculiar set of historical circumstances a new form of ordination arose in Japan based upon sixteen vows, often called Bodhisattva ordination. While an institution that has its own problems, Bodhisattva ordination also opens many possibilities. Within this form of ordination, which had its origins in China but becomes fully formed in Japan, women and men, married people as well as celibates all may achieve formal ordained leadership within the Buddhist community.

Bodhisattva ordination is the product of a historical process, by fits and starts, of internal issues and, frankly, the interference of the state. And tellingly, those who have received such ordinations have a wide variety of understandings as to what it is, often dramatically contradictory. One of the most descriptive terms applied to Bodhisattva ordination has been that it is "neither monastic nor lay." This isn't completely true; this form of ordination includes people who are celibate, people who live in committed relationships, and those who are in between such options. It includes people living in monastic settings and people living lives almost identical to conventional householders.

In the west this form of ordination allows not only equal relationships among celibate monks and nuns; but also the possibility of a type of ordained Buddhist ministry to emerge. In fact the most common translation for osho , this rank of full Bodhisattva ordination in Japanese Zen Buddhism, is priest — not as intermediary between gods and humanity, but in its more technically accurate usage as "elder." Here we have a new kind of Buddhist guide, a minister among the community.

One need not embrace a liberal Buddhist perspective to accept this model of ordination. Nor is it the only possible model for an inclusive leadership. For instance the largest of the Zen schools in the west, the Kwan Um School of Zen, uses a vinaya monastic model tightly wound together with a strong emphasis on lay practice and teaching. Still, this model of Bodhisattva ordination is quintessentially an expression of the concerns and possibilities in the liberal Buddhist approach.

There should be no doubt that the contributions of women to the formation of a western and liberal Buddhism are of incalculable significance. Woman leaders and teachers, with their perspectives and insights, along with (though to a lesser degree) the perspectives of gay and lesbian thinkers are helping create an even richer vision of the Dharma than that which we have inherited from our traditional teachers.

Here we find the egalitarian promise, hinted at in the formation of the Buddhist sangha, beginning to flower. Shifting from traditionally masculine and (while I think the term somewhat problematic, it is still instructive) "patriarchal-identified approaches," and instead embracing the possibility of a variety of perspectives as articulated within much of feminist thought, we begin to see a more socially engaged Buddhism. Indeed, it is within the social aspects of liberal Buddhism that we in the west have particularly enriched the treasure that we've been given.

One of the first truly important books to rise out of the liberal Buddhist movement is Ken Jones's The New Social Face of Buddhism: A Call to Action . In traditional Buddhist schools the focus, as Stephen Batchelor implied in a somewhat different context, is essentially psychological. Classically, Buddhism is an examination of the human mind: how it works, what happens, and how to deal with it. Ken takes this foundational work of the Buddha, Nagarjuna, and all who followed, and pushes their insights. Out of that, he demonstrates the most significant aspect of a liberal Buddhism.

Early on in his book Ken offers up the image of Indra's Net, derived from the Avatamsaka Sutra , the core text of the Hua-yen school of Chinese Buddhism. Here we find the image of an infinite net that has an infinitely faceted jewel at each intersection of its infinite threads. With a single flash of light we have the whole of creation bursting forth. Within this image we find a reality where each jewel exists only as a reflection of the other jewels. And at the same time each of these individual jewels is the support of all the other jewels. None has a separate existence from all the others; each exists only within a realm of mutuality.

Ken takes this image and that of the Bodhisattva, the "enlightening-being" at the heart of the Mahayana way, and suggests there is a social ethic implicit within these images. He strives to make this insight explicit, something that characterizes much of liberal Buddhism. So we might begin to notice the assertion our egos, our sense of self is in fact a construction is also a suggestion that society itself is a construction. But rather than follow the analysis of Karl Marx or his opponents in considering this social construction, Ken draws upon the way of the Buddha and particularly the emphasis of Zen.

I believe these various threads of liberal Buddhism - rational and humanistic biases, inclusion of women and homosexual persons, emphasis on lay practice; and core understanding of the Dharma's social as psychological significance - have woven together to create something particularly powerful and useful.

Where all this will lead is an open question. The Dharma has only been sinking roots in the west for less than a hundred years. It will take generations to sort out what will be. But, if our choices are made with deliberation and care, as both liberal and more traditional forms of the Dharma root here, the possibilities for healing hurt, for opening hearts and eyes, for transforming individuals and our culture itself is as wide as the sky itself.

There is much reason for hope.