ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

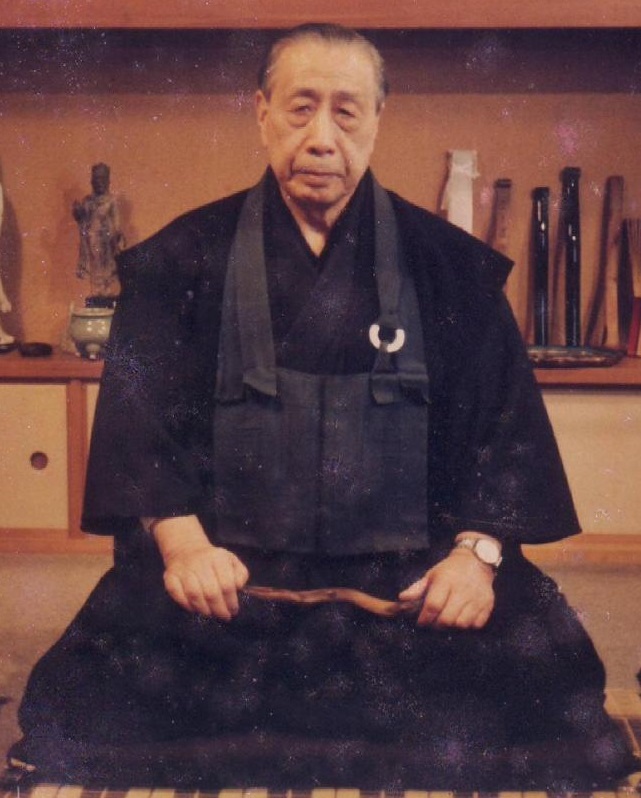

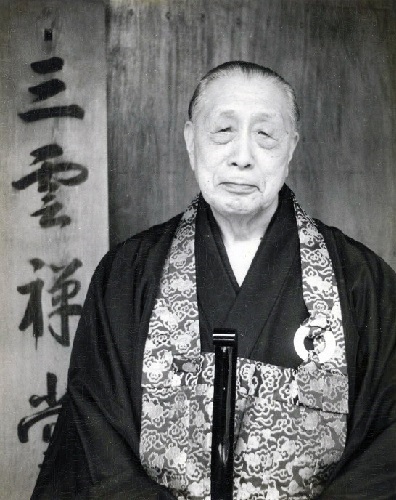

山田耕雲 Yamada Kōun (1907-1989)

Dharma name: 耕雲禅心 Kōun Zenshin

born 山田匡藏 Yamada Kyōzō

The Sanbô Kyôdan is a Zen-Buddhist Religious Foundation (shûkyô-hôjin) started by YASUTANI Haku'un Roshi on 8 January 1954.

The second abbot of the Sanbô Kyôdan, YAMADA Kôun Roshi, was born in Nihonmatsu City, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan, on 18 March 1907. He started Zazen in Manchuria in 1943 under the guidance of KÔNO Sôkan Roshi. Upon returning to Honshu, Japan, in 1945 he devoted himself to zazen practice under ASAHINA Sôgen Roshi of the Engakuji in Kamakura as well as under HANAMOTO Kanzui Roshi of the Mokusenji in Ôfuna. However, he never became a monk and continued to work in the business world; his major position was president of the Tokyo Kembikyôin Medical Center.

YAMADA Roshi received the Buddhist precept from HARADA Sogaku Roshi in 1950; through this connection he came into contact with YASUTANI Roshi, HARADA Roshi's disciple, whom YAMADA Roshi invited in 1953 to launch the Zen group called "Kamakura Haku'un-kai" and to begin a monthly zazenkai in Kamakura. In the same year he experienced an unusually deep enlightenment, which led him to the Dharma succession in 1960. In 1967 he was appointed Zen Master (shôshike) of the Sanbô Kyôdan. Three years later he became the president of the Kyôdan.

PDF: In Memoriam: Yamada Kōun Rōshi (1907-1989)

by Ruben L. F. Habito

Buddhist-Christian Studies, Vol. 10 (1990), pp. 231-237.

山田耕雲 Yamada Kōun Zenshin (1907-1989) or Koun Yamada

with his wife, Mrs. Kazue Yamada

The San'un Zendo as the Central Dôjô

In 1970, Kôun Roshi, together with his wife Dr. Kazue YAMADA, built the San'un Zendo in his family compound. ("San'un" means "three clouds," representing the three Zen masters in the same lineage: "HARADA Daiun [big cloud]," "YASUTANI Haku'un [white cloud]," and "YAMADA Kôun [plowing cloud]"). Subsequently the San'un Zendo became the central dôjô [place of practice] of the Sanbô Kyôdan. Here, YAMADA Kôun Roshi guided both Japanese and non-Japanese students in the zazenkai (zazen gathering at the weekend, held twice a month) as well as in the sesshin (zazen gathering for several days, held several times a year).

Especially after Father Hugo M. ENOMIYA-LASSALLE became an earnest student of YAMADA Roshi, many Christian priests, nuns and pastors started to seek the guidance of YAMADA Roshi.

By the time of his passing on 13 September 1989 as many as 24 Japanese and 21 non-Japanese disciples had finished the formal course of Zen training.

Books

Hekiganroku - Die Niederschrift vom blauen Fels

Die klassische Koansammlung mit neuen Teishos - 2 Bände

Yamada Kôun / Lengsfeld, Peter (Hg.)

Kösel-Verlag GmbH & Co., München, 2002PDF: The Gateless Gate: The Classic Book of Zen Koans

Translated with commentary by Kōun Yamada

Wisdom Publications, Boston, 2004 > text onlyPDF: Zen: the Authentic Gate

by Kōun Yamada

Periodical

Dharma Lineage

永平道元 Eihei Dōgen (1200-1253)

孤雲懐奘 Koun Ejō (1198-1280)

徹通義介 Tettsū Gikai (1219-1309)

螢山紹瑾 Keizan Jōkin (1268-1325)

明峰素哲 Meihō Sotetsu (1277-1350)

珠巌道珍 Shugan Dōchin (?-1387)

徹山旨廓 Tessan Shikaku (?-1376)

桂巌英昌 Keigan Eishō (1321-1412)

籌山了運 Chuzan Ryōun (1350-1432)

義山等仁 Gisan Tōnin (1386-1462)

紹嶽堅隆 Shōgaku Kenryū (?-1485)

幾年豊隆 Kinen Hōryū (?-1506)

提室智闡 Daishitsu Chisen (1461-1536)

虎渓正淳 Kokei Shōjun (?-1555)

雪窓祐輔 Sessō Yūho (?-1576)

海天玄聚 Kaiten Genju

州山春昌 Shūzan Shunshō (1590-1647)

超山誾越 Chōzan Gin'etsu (1581-1672)

福州光智 Fukushū Kōchi

明堂雄暾 Meidō Yūton

白峰玄滴 Hakuhō Genteki (1594-1670)

月舟宗胡 Gesshū Sōko (1618-1696)

徳翁良高 Tokuō Ryōkō (1649-1709)

芳巖祖聯 Hōgen Soren

石叟哲周 Sekisō Tesshū

隆孝楞洲 Ryukō Ryōshū

聯山祖芳 Renzan Sohō

物外志道 Motsugai Shidō

愚溪容雲 Gukei Yōun

嚇照祖道 Kakushō Sodō (1844-1931) [原田 Harada]

大雲祖岳 Daiun Sogaku (1871-1961) [原田 Harada]

白雲量衡 Hakuun Ryōkō (1885-1973) [安谷 Yasutani]

耕雲禅心 Kōun Zenshin (1907-1989) [born 山田匡藏 Yamada Kyōzō]

Enlightenment Experience by Mr. K. Y., a Japanese Executive, Age 47

The Three Pillars of Zen, edited by Philip Kapleau offered a detailed description of the type of Zen that Yamada Roshi taught. It included introductory lectures on Zen practice by Yasutani Haku’un and transcriptions of private interviews (dokusan) with practitioners. Yamada was Yasutani’s successor as spiritual leader of the Sanbō Kyōdan (now Sanbō Zen). Most interesting, however, were the “Contemporary Enlightenment Experiences” toward the back of the book. The first account was by “Mr. K. Y., a Japanese Executive, Age 47”

Mr. K. Y. was Mr. Kyōzō Yamada: Yamada Roshi.

NOVEMBER 27, 1953:

Dear Nakagawa-roshi:

Thank you for the happy day I spent at your monastery.

You remember the discussion which arose about Self-realization centering around that American. At that time I hardly imagined that in a few days I would be reporting to you my own experience.

The day after I called on you I was riding home on the train with my wife. I was reading a book on Zen by Son-o, who, you may recall, was a master of Soto Zen living in Sendai during the Genroku period [1688–1703]. As the train was nearing Ofuna station I ran across this line: “I came to realize clearly that Mind is no other than mountains and rivers and the great wide earth, the sun and the moon and the stars.”14

I had read this before, but this time it impressed itself upon me so vividly that I was startled. I said to myself: “After seven or eight years of zazen I have finally perceived the essence of this statement,” and couldn’t suppress the tears that began to well up. Somewhat ashamed to find myself crying among the crowd, I averted my face and dabbed at my eyes with my handkerchief.

Meanwhile the train had arrived at Kamakura station and my wife and I got off. On the way home I said to her: “In my present exhilarated frame of mind I could rise to the greatest heights.” Laughingly she replied: “Then where would I be?” All the while I kept repeating that quotation to myself.

It so happened that that day my younger brother and his wife were staying at my home, and I told them about my visit to your monastery and about that American who had come to Japan again only to attain enlightenment. In short, I told them all the stories you had told me, and it was after eleven-thirty before I went to bed.

At midnight I abruptly awakened. At first my mind was foggy, then suddenly that quotation flashed into my consciousness: “I came to realize clearly that Mind is no other than mountains, rivers, and the great wide earth, the sun and the moon and the stars.” And I repeated it. Then all at once I was struck as though by lightning, and the next instant heaven and earth crumbled and disappeared. Instantaneously, like surging waves, a tremendous delight welled up in me, a veritable hurricane of delight, as I laughed loudly and wildly. “Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha! There’s no reasoning here, no reasoning at all! Ha, ha, ha!” The empty sky split in two, then opened its enormous mouth and began to laugh uproariously: “Ha, ha, ha!” Later one of the members of my family told me that my laughter had sounded inhuman.

I was now lying on my back. Suddenly I sat up and struck the bed15 with all my might and beat the floor with my feet, as if trying to smash it, all the while laughing riotously. My wife and youngest son, sleeping near me, were now awake and frightened. Covering my mouth with her hand, my wife exclaimed: “What’s the matter with you? What’s the matter with you?” But I wasn’t aware of this until told about it afterwards. My son told me later he thought I had gone mad.

“I’ve come to enlightenment! Shakyamuni and the patriarchs haven’t deceived me! They haven’t deceived me!”16 I remember crying out. When I calmed down I apologized to the rest of the family, who had come downstairs frightened by the commotion.

Prostrating myself before the photograph of Kannon you had given me, the Diamond sutra, and my volume of the book written by Yasutani-roshi, I lit a stick of incense and did zazen until it was consumed half an hour later, though it seemed only two or three minutes had elapsed.

Even now my skin is quivering as I write.

That morning I went to see Yasutani-roshi and tried to describe to him my experience of the sudden disintegration of heaven and earth. “I am overjoyed, I am overjoyed!” I kept repeating, striking my thigh with vigor. Tears came which I couldn’t stop. I tried to relate to him the experience of that night, but my mouth trembled and words wouldn’t form themselves. In the end I just put my face in his lap. Patting me on the back he said: “Well, well, it is rare indeed to experience to such a wonderful degree. It is termed ‘Attainment of the emptiness of Mind.’ You are to be congratulated!”

“Thanks to you,” I murmured, and again wept for joy. Repeatedly I told him: “I must continue to apply myself energetically to zazen.” He was kind enough to give me detailed advice on how to pursue my practice in the future, after which he again whispered in my ear, “My congratulations!” and escorted me to the foot of the mountain by flashlight.

Although twenty-four hours have elapsed, I still feel the aftermath of that earthquake. My entire body is still shaking. I spent all of today laughing and weeping by myself.

I am writing to report my experience in the hope that it will be of value to your monks, and because Yasutani-roshi urged me to.

Please remember me to that American. Tell him that even I, who am unworthy and lacking in spirit, can grasp such a wonderful experience when time matures. I would like to talk with you at length about many things, but will have to wait for another time.P.S. That American was asking us whether it is possible for him to attain enlightenment in one week of sesshin. Tell him this for me: don’t say days, weeks, years, or even lifetimes. Don’t say millions or billions of kalpa. Tell him to vow to attain enlightenment though it take the infinite, the boundless, the incalculable future.

MIDNIGHT OF THE 28TH: [These diary entries were made during the next two days.] Awoke thinking it 3 or 4 A.M., but clock said it was only 12:30.

Am totally at peace at peace at peace.

Feel numb throughout body, yet hands and feet jumped for joy for almost half an hour.

Am supremely free free free free free.

Should I be so happy?

There is no common person.17

The big clock chimes—not the clock but Mind chimes. The universe itself chimes. There is neither Mind nor universe. Dong, dong, dong!

I’ve totally disappeared. Buddha is!

“Transcending the law of cause and effect, controlled by the law of cause and effect”18—such thoughts have gone from my mind.

Oh, you are! You laughed, didn’t you? This laughter is the sound of your plunging into the world.

The substance of Mind—this is now luminously clear to me My concentration in zazen has sharpened and deepened.MIDNIGHT OF THE 29TH: I am at peace at peace at peace. Is this tremendous freedom of mine the Great Cessation19 described by the ancients? Whoever might question it would surely have to admit that this freedom is extraordinary. If it isn’t absolute freedom or the Great Cessation, what is it?

4 A.M. OF THE 29TH: Ding, dong! The clock chimed. This alone is! This alone is! There’s no reasoning here.

Surely the world has changed [with awakening]. But in what way?

The ancients said the enlightened mind is comparable to a fish swimming. That’s exactly how it is—there’s no stagnation. I feel no hindrance. Everything flows smoothly, freely. Everything goes naturally. This limitless freedom is beyond all expression. What a wonderful world!

Dogen, the great teacher of Buddhism, said: “Zen is the wide, all-encompassing gate of compassion.”

I am grateful, so grateful.

14

A quotation from Dogen’s Shobogenzo, originally found in Zenrui No. 10, an

early Chinese Zen work.

15

This is not a Western but a traditional Japanese “bed,” which consists of a

quilted mattress two or three inches thick spread over the regular tatami

mats.

16

This is a traditional way of saying that the enlightenment taught by the

Buddhas and Dharma Ancestors is now an actual fact of one’s own

experience.

17

That is, Buddhahood is latent in everyone.

YAMADA KOUN ROSHI

(Obituary, 1989)

by Robert Aitken Roshi

Koun Yamada, Roshi, of the Sanun Zendo and the leader of the Sanbo Kyodan School of Zen Buddhism, died at his home in Kamakura on September 11 after a long illness. He was 82.

Yamada Roshi was born Kyozo Yamada in northern Japan. He was graduated from high school in Tokyo, and from the Tokyo Imperial University, majoring in German law. His roommate in high school was Soen Nakagawa, later Roshi of Ryutaku Monastery and an important figure in the early years of Western Zen. They became lifetime friends.

After graduation the young Kyozo Yamada was employed in the insurance business in Tokyo. He married, and shortly before the war moved with his family to Manchuria. There he met Soen Nakagawa again, who was by this time a monk, attending his teacher Gempo Yamamoto Roshi of Ryutaku Monastery and abbot pro-tem of the Manchurian branch of Myoshin Monastery of Kyoto.

In the course of discussions with his old friend, Kyozo Yamada was persuaded to take up the practice of zazen. On his return to Japan after the war with his family, he began Zen practice with Asahina Sogen Roshi, Roshi of Enkaju Monastery in North Kamakura, the temple where D. T. Suzuki and Nyogen Senzaki had trained 40 years earlier. He did Jukai with Asahina Roshi, and received the dharma name Zenshin (“Zen Mind”).

He was not able to have the daily dokusan he sought with Asahina Roshi, however, so took up practice with Tanzen Hamamoto, a Roshi in the city of Ofuna, just north of Kamakura. He practiced with Hamamoto Roshi for two years, seeing him every morning, on his way from Kamakura to Tokyo to work. He then got together with a friend and sought to establish a lay Zen group in Kamakura, but Hamamoto Roshi was not able to give the time that leading such a group would entail.

It was then that he met the Roshi Haku’un Yasutani who agreed to serve as teacher of such a group. Members then met in a rented temple in Kamakura for several years. He had begun work in koan study with Asahina Roshi and continued with Hamamoto Roshi, but it was with Yasutani Roshi that he had his great kensho, described in The Three Pillars of Zen. He continued his koan study with Yasutani Roshi, and was acknowledged his successor, receiving the teacher name Koun Ken (“House of Cultivating Clouds”).

Ultimately Yamada Roshi retired from business, and accepted a position as Chairman of the Board of Directors of Kenbikyoin, a large clinic in Tokyo, where his wife was medical director. He held this position until his death. In 1969, Yasutani Roshi retired, and with his wife Yamada Roshi set about establishing the Sanun Zendo (Zendo of the Three Clouds), named for the roshis Dai’un (Great Cloud) Harada, Haku’un (White Cloud), and himself. He then gave himself to the teaching of Zen during evenings, weekends, and frequent sesshins, serving several hundred students, including large numbers of Europeans and Americans. All this while maintaining a full schedule of work at the Clinic, with a daily commute of well over two hours.

With Yasutani Roshi’s retirement, the Diamond Sangha was left without a visiting teacher, and Yamada Roshi agreed to take his place. He made annual trips to lead sesshins at Koko An and at the Maui Zendo from 1971 until 1984, when Robert Aitken received transmission. As Aitken Roshi’s 20 teacher, and as head teacher of the Diamond Sangha for 13 years, Yamada Roshi is largely responsible for the vitality and direction of the Diamond Sangha today.

Yamada Roshi is survived by his wife, Dr. Kazue Yamada, and by three children and several grandchildren.

Translation of Yamada Koun Roshi's Teisho

on the Hekiganroku (Blue Cliff Record)

| Foreword of the Editor | Preface of the Author |

Translation of Yamada Koun Roshi's Teisho

on the Shoyoroku (Book of Equanimity)

| Foreword of the Editor | List of Financial Contributors |