ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

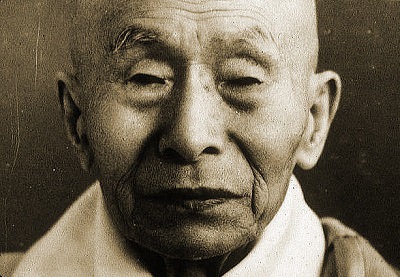

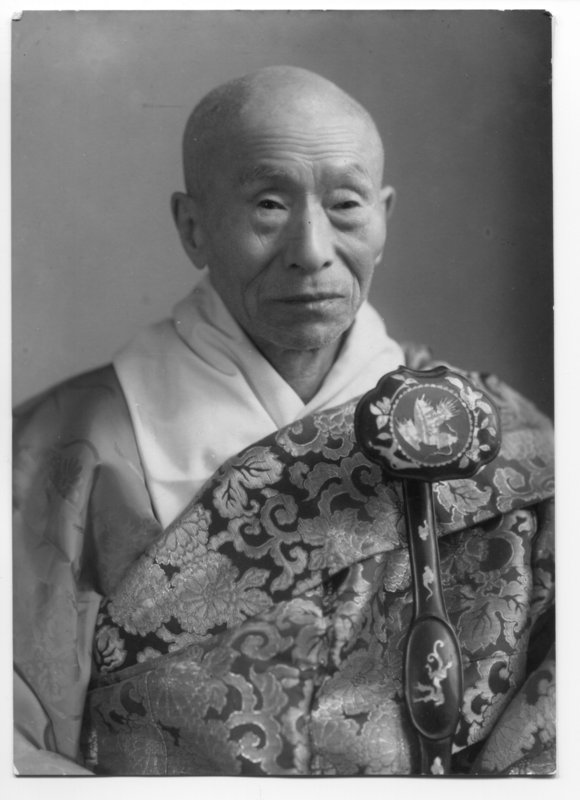

原田(大雲)祖岳 Harada (Daiun) Sogaku

(1871-1961)

HARADA Daiun Sogaku (13 Oct 1871-12 Dec 1961)

[Dharma heir of the Sōtō master

原田祖道嚇照

Harada Sodō

Kakushō

(1844-1931) and a Dharma heir of the Rinzai master

高源室毒湛匝三 Kōgen-shitsu Dokutan Sōsan (1840-1917)

(a.k.a 毒湛豐田 Dokutan Toyota), 31st teacher within Soto generation since Dōgen Kigen (1200-1253), and 8th teacher within Rinzai generation since Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1769)]

Daiun Sogaku Harada Roshi:

http://www.zencentrum.nl/html/publicaties/daiunsogaku/zenleven1.php

http://www.zencentrum.nl/html/publicaties/daiunsogaku/zenleven2.php

My life in Zen temples is a long, continuing story. To calculate the years, I was first taken into a temple when I was seven years old, and I am now eighty-six. Last fall in Tokyo I saw an authority in the field of phrenology who said that I will be fine until age ninety, so it does not appear that my time is up yet.

Originally, I was supposed to live to be fifty-five years old, or so I was told as a youth by a previous generation of fortune-tellers. Despite that forecast, my life span has stretched up to the present, and I attribute this to my having come to believe in the inevitable working of cause and effect and thus, to the extent that I could, in practicing accordingly. Above all, I believe that my living so long is a fruit of doing zazen.

"There is no one, only karma." Karmic inevitability is a great, eternal, immortal and ironclad law, and neither gods nor buddhas nor demons can tamper with it. Therefore, by watching the health, physically, by maintaining a calm lifestyle, spiritually, and by actively aiming to plant the seeds of virtue, one can steadily extend one's lifespan.

I was a rather weak child to begin with, and on top of that, very little attention was paid to nutrition in Zen temples of old. The usual fare consisted of boiled barley and rice with radishes and miso soup with greens. The occasional tofu, fried tofu or pressed devil's tongue was a real treat. As a result of this diet, from childhood through youth, the skin over my whole body was dry, and in cold weather I was plagued by chapped, cracking skin.

During my years in the training hall at Shogenji in Ibuka, Mino, the annual December round of begging for radishes was a trying time. We collected the radishes from outlying villages and, by twos, carried the heavy loads back to the temple on our shoulders. The ruptures on the soles of my feet would bleed, so that I had to proceed on tiptoes. Upon returning to the temple, all the monks would bathe to warm up before sleeping, but with my feet burning so painfully, I could not go into the bath.

This kind of thing, however, does not really fall into the category of tales of hardship for a Zen monk. For the Zen monk, the greatest pain lies in bringing to light the Great Matter.

The founder of our sect, Dogen Zenji, said, "To learn the Buddha Way is to learn one's own self." But that self is not this illusive five-plus feet of flesh. The universe, infinite in space and time, is nothing but the self. The self is nothing but the universe. This is the true self which could never be touched by the likes of a nuclear explosion. This is your true face before you were born. Correct Buddhist practice is to believe and understand this, to train, to awaken and to personify it. Such practice is not, by the way, limited to Zen.

And yet, I heard something very strange on the radio the other night. It was from a young man participating in one of those quiz shows that are so popular these days. This young man gave as his profession, "Buddhist priest." At this, the moderator commented that the training must be very difficult, to which the young man calmly replied, "No, I don't do any training." The moderator was reduced to mute amazement.

This particular priest happened to come from another sect, but I just want to say that these days the Zen priesthood, as well, abounds with such types. Actually, we might even say they form the majority.

In this age of housing problems, priests live in spacious temples built for them by our ancestors, and all they have to do is read a few sutras, perform funerals, and keep up the graveyards. They even go so far as to carry on domestic lives with their wives and children, just like ordinary laymen. Moreover, with the government confiscation of farmlands after the war, temples lost the rice fields which had been a source of revenue. Consequently, many priests have taken on such sideline jobs as teaching school and serving as municipal officials, and they do not give hard training even so much as a glance.

Furthermore, even the universities which are supposed to be training religious persons are not requiring the students to practice. As a result, the number of monks in training halls like mine is ever decreasing. On the other hand, the number of young lay aspirants is, oddly enough, on the increase.

Not only ordained priests, but young people in general, if they are serious, are seeking truth and are troubled with doubts and questions about life. They begin to ponder questions like these: Why are we born? In what way should we live? What happens after death?

I, too, was troubled by such questions in my youth, and at the heart of that distress was the question of birth and death. Dogen Zenji wrote in the opening of his Shushogi, "The thorough clarification of the meaning of birth and death - this is the most important problem of all for Buddhists."

I mercilessly agonized over this until I could stand it no longer! Finally, I sat down and wrote long letters to three Buddhist leaders of that day: Dr. Sensho Murakami, a foremost Buddhist scholar; Shaku Soen Zenji, a great zazen master; and Unsho Risshi, a Shingon sect master highly honored for his imminent virtue. I asked for a rock bottom answer to the cluestion of life and death: When a human being dies, does he vanish like the clouds and mist, or is there a life after death?

Each of these gentlemen quickly responded to the rough-mannered questions of this young, obscure monk from the hinterlands, and I still feel thankful for that today. To begin, from Dr. Murakami came the dubious reply:

Buddhism teaches that there is no permanent self. If there is no permanent self, there should be no birth and death. However, perhaps there is life and death for those who recognize in themselves an ego.

A severe scolding came from Unsho Risshi:

Can a disciple of the Buddha be questioning such a thing? Is it not clearly stated right there in the teachings whether you look at the doctrinal aspect or in any of the sutras? But if you still do not understand it, come to my hall for training.

And from Shaku Soen Roshi came the instruction:

What? A Buddhist who does not know about the continuity of life? If you experience kensho (satori, or enlightenment), you can clear up that little problem before you sit down to breakfast. Both koan, "What is the sound of one hand clapping?" and, Kaku Osho of Roya said, 'If all things are innately pure, then how is it that the mountains, rivers, and the great earth suddenly arise?'" are good. If you clearly penetrate either of these koan, your problem will promptly be settled.

It may be discourteous to mention what I thought after considering these three replies, but I did not think that Dr. Murakami really understood Buddhist tenets. It will simply not do to say that because Buddhism teaches egolessness, there is no birth and no death. As for Unsho Risshi, what he said was reasonable enough, but because it seemed that his understanding might not go beyond theory, I could not bring myself to go to his temple for training. This left only Shaku Soen Roshi to depend on, and his reply was the most edifying of the three. I firmly resolved that I would have to undergo earnest training and come to enlightenment.

So it was that I went for training to the Rinzai sect monastery: Shogenji, which I mentioned before, and I was able to hear "the sound of one hand clapping." That is to say that upon attaining kensho, I really had deep peace of mind for the first time.

As anyone who has had the experience knows, a very special joy accompanies that first kensho, and in that joy I went off to myseIf and danced a little jig. But after a month or two, even that experience became doubtful, and I plunged into a deeper anguish than ever. Once again I threw myself into practice. Memories of things like sitting in the snow and doing zazen stark naked in a bamboo grove swarming with mosquitos come from this period. My second kensho experience may sound a little distasteful. One morning while I was on a long begging trip, an old woman happened to urinate in the toilet beside a farmhouse gate as I passed. When I saw the frothing urine I had satori.

I had gone to Ibuka when I was twenty years old, and I stayed there for three years, training under both Daigi Osho and Toju Osho. Then, I entered the university of a Buddhist sect to study Buddhist theory. After greduating, I was twice appointed to conduct university research, which I carried on for six years. During that time, I practiced under Jitsuyu Watanabe, Tenkai Hoshimi, Tatsujun Adachi, Sotan Oka, and Kodo Akino, all teachers of the sect, but, to tell the truth, none of them quite sufficed. Then, finally, I went to Kogen-shitsu Dokutan Rodaishi of Nanzenji and practiced under him for three years.

Dokutan Roshi was an outstanding training master, endowed with both the power of Buddha-truth and with moral excellence. I am truly fortunate to have been able to practice under such a highly respected teacher.

As I always tell those practicing under me, Dokutan Roshi trained to this extent despite a weak constitution from childhood. He always spoke very softly, but when this roshi would scold me, in a voice one could just barely catch, a cold shiver of sweat would break out of my armpits. I had been hauled roughly over the coals by other masters before and remained relatively cool, but while Dokutan Roshi's words were similar or equal, his strength of character added force. I learned from him that strength of character alone can move men.

Well, during this time, I had kensho two, three more times, and, at last, I worked out the problem of birth and death. Tranquil in my heart. I could fall into sleep with a loud snore. But to reach this point took twenty years of training. Of course, this does not mean that I graduated. I am still in practice, and while I am an old man who has lived eighty-six years, on the path I am just a two-year-old child, still wet behind the ears, a most humbling state.

In my youth, I formulated a rough schedule for my life. I would devote myself to practice and study until I turned forty. Then from forty to sixty, I would work for others, giving religious instruction. From sixty on, I would continue to make every effort within my power. However, when the scheduled age of forty came around, it looked as though I had no alternative but to accept a teaching post in the university I had been attending. I taught at Komazawa University for twelve years - until I realized that it was far more important to train Zen monks than to follow the teaching profession. So I started Hosshinji Monastery, and I have been there ever since; that makes thirty-six or seven years up to now.

Even looking at the ancient teachers, those most noble and worthy of veneration are those whose mind spheres were tempered over long years of training. For example, Joshu (a famous Chinese Zen monk 778-897) had his first major awakening at the age of eighteen, followed by eighteen major experiences of satori and countless smaller ones. He left home at age sixty, and he burst the bottom out of the bucket with his last koan, "Ordinary mind is the Way," at around age eighty. He lived to be one hundred and twenty-three years old. Therefore, Joshu stands out in his great attainment even among the many patriarchs of our recorded sayings, a master among masters.

"To learn the Buddha Way is to learn one's own self." We previously quoted these words of the founder of Eiheiji, who continues, "To learn oneself is to forget oneself." The training required to forget this self is not an easy undertaking. Suppose one somehow manages to attain kensho and to awaken from the dream of duality - delusion and enlightenment ordinary man and saint, self and other, host and guest, birth and death, right and wrong, gain and loss - and to discern that heaven and earth and the self are one. Still, the grime of tendencies carried over from the beginningless past does not wash off easily. And then if one has satori, the stain of that very satori readily adheres, and the practice required to remove it is a big job indeed. To this end, the old masters used 'The Four Conditions,' 'The Five Ranks,' and 'The Ten Oxherding Pictures' to examine in careful detail depths and stages of practice.

It is said that with a clear kensho experience, delusive views of truth are smashed suddenly, in one blow, like the cracking of a rock. Delusive thought, however, is delusion which is bound to convention and habit, and cutting through it is, thus, like cutting through the lotus stem with its obstinately persistent threads.

It is for this reason that the patriarchs devoted themselves to still further practice for twenty, fifty years after attaining satori. Even in recent times here in our country, both Daito Kokushi and Kojiki Tosui led lives of begging, and Kanzan Kokushi concealed himself deep in the mountains of Ibuka to live a farmer's life, all for no other reason than to forge themselves, after satori, like well-tempered steel.

Sekito Zenji sternly cautions in his 'Sandokai,' "Although it stands to reason, it is not satori." This being the case, while people in Zen rashly go around writing and mouthing such expressions as, "Everyday is a good day," and "Pure wind, bright moon," to actually put all of this into practice is not so easy.

In this age of speed in all matters, who needs this troublesome training anyway? Do the Buddhas and the patriarchs themselves not say that all beings are essentially endowed with Buddha nature? This and other heresies are put forth in so-called Dharma talks by so-called teachers whose own eyes are not opened. How much more frightening is this recklessness of our times than even the atomic bomb which is so feared by the world?

So as it stands now, I am a feeble old man, who has long since passed his proposed age of retirement, still trying to throw my weight around, at least in an effort to help open the eyes of those Americans who have come all the way over here to practice. I am most enthusiastic to see a correct transmission of Zen cross the waters.

Mr. Kapleau, who is now at my training hall, was here some years ago as a court reporter for the Tokyo Trials. Now, just like the monks, he dines on rice gruel, hauls buckets of night soil, and practices both zazen and meditation in action, while grappling with the koan "Mu." He attends the week-long sesshin (zazen retreats) which are held six times a year, keeping vigil through the night: mu - mu - mu - mu. While all of this effort is truly laudable, unfortunately he has not yet had satori.

It is a great pity, as you can see, that the foreigners cannot easily sit without pain in their legs. Looking at them, we cannot be thankful enough that we Orientals, who are fortunate enough to be raised in Buddhist countries can easily cross our legs in zazen.

Before concluding, I want to mention a few more words regarding the Americans in practice. there were four here, including one woman but three have returned to their native country, leaving only Mr. Kapleau. It looks as as if Mr. Philip, who was here before, will soon be coming back, however. All four were, for the most part, prompted to begin zazen practice as a result of hearing lectures by Dr. Daisetsu Suzuki at Colombia University. That is to say, they know that the marrow of Zen definitely cannot be reached through concepts, percention or faith. As Dr. Suzuki told them, in order to experience 'spiritual self knowledge,' it is necessary to undergo formal training under a true master.

Mr. Philip, who is an instructor of Western philosophy at an American university, did zazen practice with me last year while he was here as an exchange professor at Nara Women's College. It seems that he originally traveled twice to India, as the birthplace of Buddhism, in search of a true teacher. He told me that he finally found one whose Dharma eye was open, but because this person had never brought another to awakening, Mr. Philip thought the situation futile. Thus, he came to Japan.

In any case, these Americans who are coming here to practice are truly precious for the sake of the great Dharma. On their behalf, I will take extra good care of this body and pray that I may live to an even riper old age.

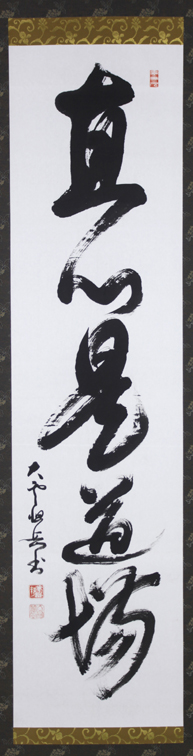

Text: The straightforward mind is the training place. Painted by Harada Daiun Sogaku.

Temple: The Soto sect. Zen master of Hosshin-ji, Obama. Chigen-ji, Miyazu. The ex-professor of Soto-shu College.

Data: Pen name: Kakusho-ken. Dharma transmission from Kodo Harada. He practiced Zen under Sotan Oka, Kodo Akino, Tenkai Satomi, Tatsujun Adachi and also in Rinza sect, Taigi Sokin, Toju Reiso in Shogen-ji, Dokutan Sosan in Nanzen-ji monastery. He was a professor at Soto-shu Daigakurin in 1911. He became the 27th abbot of Hosshin-ji in 1922.

Paper Dimension /cm: 132*33 Whole Dimension /cm: 197.2*45.5

About the Harada-Yasutani School of Zen:

http://www.ciolek.com/WWWVLPages/ZenPages/HaradaYasutani.html

Dharma lineage

永平道元 Eihei Dōgen (1200-1253)

孤雲懐奘 Koun Ejō (1198-1280)

徹通義介 Tettsū Gikai (1219-1309)

螢山紹瑾 Keizan Jōkin (1268-1325)

明峰素哲 Meihō Sotetsu (1277-1350)

珠巌道珍 Shugan Dōchin (?-1387)

徹山旨廓 Tessan Shikaku (?-1376)

桂巌英昌 Keigan Eishō (1321-1412)

籌山了運 Chuzan Ryōun (1350-1432)

義山等仁 Gisan Tōnin (1386-1462)

紹嶽堅隆 Shōgaku Kenryū (?-1485)

幾年豊隆 Kinen Hōryū (?-1506)

提室智闡 Daishitsu Chisen (1461-1536)

虎渓正淳 Kokei Shōjun (?-1555)

雪窓祐輔 Sessō Yūho (?-1576)

海天玄聚 Kaiten Genju

州山春昌 Shūzan Shunshō (1590-1647)

超山誾越 Chōzan Gin'etsu (1581-1672)

福州光智 Fukushū Kōchi

明堂雄暾 Meidō Yūton

白峰玄滴 Hakuhō Genteki (1594-1670)

月舟宗胡 Gesshū Sōko (1618-1696)

徳翁良高 Tokuō Ryōkō (1649-1709)

芳巖祖聯 Hōgen Soren

石叟哲周 Sekisō Tesshū

隆孝楞洲 Ryukō Ryōshū

聯山祖芳 Renzan Sohō

物外志道 Motsugai Shidō

愚溪容雲 Gukei Yōun

嚇照祖道 Kakushō Sodō (1844-1931) [原田 Harada]

大雲祖岳 Daiun Sogaku (1871-1961) [原田 Harada]

白雲量衡 Hakuun Ryōkō (1885-1973) [安谷 Yasutani]

Harada-Yasutani (also known as The Sanbo Kyodan or "Three Treasures") school of Zen was established in Japan by D.S Harada Roshi and his student and close collaborator H.R.Yasutani Roshi. The school, one of the most energetic and iconoclastic Buddhist organisations in the post-war Japan, combines elements of Japanese Soto (esp. teachings of Dogen Kigen and his Dharma grandson, Keizan Jokin) and Rinzai (esp. teachings of Hakuin Ekaku) traditions while its 'graduates' constitute the lion share of all Zen teachers currently active in USA, Germany, Switzerland, Philippines and Australia.

Harada's Rinzai Lineage

Harada always remained in the Sōtō Lineage; but he also received transmission in the Rinzai Lineage from Dokutan Sōsan:白隱慧鶴 Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1769)

卓洲胡僊 Takujū Kosen (1760-1833)

妙喜宗績 Myōki Sōseki (1774-1848)

迦陵瑞迦 Karyō Zuika (1790-1859)

潭海玄昌 Tankai Genshō (1811-1898)

毒湛匝三 Dokutan Sōsan (1840-1917) [高源室 Kōgen-shitsu; 豐田 Toyoda]

大雲祖岳 Daiun Sogaku (1871-1961) [原田 Harada]

To be noted

原田正道 Harada Shōdō (1940-) Dharma lineage is different, he had a Rinzai master: 山田無文 Yamada Mumon (1900-1988)

PDF: About Hosshinji

![]()

原田大雲祖岳御老師 (1871/10/13~1961/12/12)

| 1871/10/13 | 福井県小浜市にて出生 |

| 1883/4/8 | 同市仏国寺の原田祖道老師について得度 |

| 1895/3/4 | 祖道老師に伝法相続 |

| 1901/7 | 駒澤大学卒業 |

| その間、曹洞宗の秋野孝道老師、臨済宗伊深正眼寺の雲霧軒大義老師 京都南禅寺の高源室毒湛老師等に師事。 |

|

| 1911~1921 | 曹洞宗大学林教授、その間、岩手県盛岡・報恩寺等に歴任 |

| 1921/1 | 小浜市発心寺に晋住 東京東照寺開山 |

| 1961/12/12 | 発心寺赫照軒にて遷化 |

曹洞宗の戒律継承者である原田祖道赫照(1844-1931)は永平道元 (1200-1253)から31代目の曹洞宗の老師であり、毒湛(1840-1917)は白隠慧鶴(1686-1769)から8代目の臨済宗の老師である。 原田・安谷の禅仏教宗教法人(三宝教団又は“三宝”で良く知られている)は、原田老師と彼の弟子であり最も側近の協力者である安谷白雲 により日本で設立され、日本の戦後で最も活動的で、偶像崇拝しない仏教宗教法人のひとつであり、曹洞宗(特に永平道元と彼から四代目の弟子の螢山紹瑾の教え)、臨済宗(特に白隠慧鶴の教え)の、伝承による夫々の要点を結合させた。一方その嗣法者は、ドイツ、スイス、オーストラリアで活動している。 |