ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

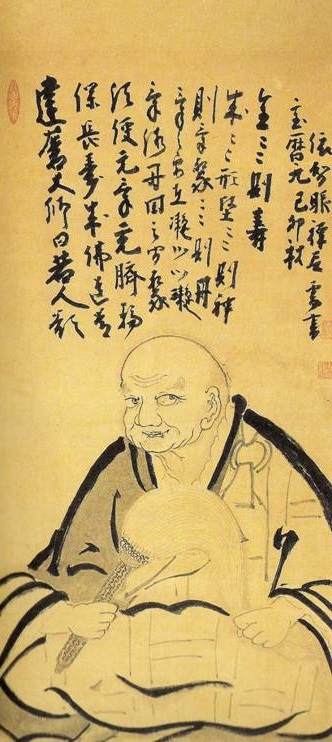

Self-portrait

白隠慧鶴 Hakuin

Ekaku (1686-1769)

Selected Writings II.

Tartalom |

Contents |

白隱禪師坐禪和讚

PDF: Vadborostyán - Hakuin zen mester önéletrajza Babits Mihály: Vakok a hídon Terebess Gábor haikui Hakuin festményeire: Bincsik Mónika

|

The Ryu'un-ji Collection 坐禅和讚 Zazen wasan 夜船閑話 遠羅天釜

PDF: Embossed Tea Kettle PDF: Night Boat Conversation 息耕錄開筵普說 Sokkō-roku Kaien-fusetsu

Itsumadegusa 壁生草

PDF: Zen Words for the Heart PDF: Beating the Cloth Drum PDF: Hakuin’s Precious mirror cave: a Zen miscellany 荊叢毒蘂 Keisō dokuzui PDF: Secrets of the Blue Cliff Record - Zen Comments by Hakuin PDF: Every End Exposed: Keiso dokuzui: The Five, Ranks of The Apparent and the Real: Nirvana Is Openly Shown to Our Eyes Dokugo Shingyo: Acid Comments on the Heart Sutra A Talk on the Platform Sutra of Hui-neng Tunnelling into the Secret Depths PDF: Hakuin on Kensho: The Four Ways of Knowing

Explication of the Four Knowledges of Buddhahood Hakuin School of Zen Buddhism PDF: The tools of one-handed Zen: PDF: Hakuin PDF: Zen Master Tales

|

Keiso

dokuzui

The Five, Ranks of The Apparent and the Real:

The Orally Transmitted Secret Teachings

of the [Monk] Who Lived on Mount To

http://www.kaihan.com/fives.htm#2

We do not know by whom the Jeweled-mirror Samadhi was composed. From Sekito Osho, Yakusan Osho, and Ungan Osho, it was transmitted from master to master and handed down within the secret room. Never have [its teachings] been willingly disclosed until now. After it had been transmitted to Tozan Osho, he made clear the gradations of the Five Ranks within it, and composed a verse for each rank, in order to bring out the main principle of Buddhism. Surely the Five Ranks is a torch on the midnight road, a ferry boat at the riverside when one has lost one's way!

But alas! The Zen gardens of recent times are desolate and barren. "Directly-pointing-to-the-ultimate" Zen is regarded as nothing but benightedness and foolishness; and that supreme treasure of the Mahayana, the Jeweled Mirror Samadhi's Five Ranks of the Apparent and the Real, is considered to be only the old and broken vessel of an antiquated house. No one pays any attention to it. [Today's students] are like blind men who have thrown away their staffs, calling them useless baggage. Of themselves they stumble and fall into the mud of heterodox views and cannot get out until death overtakes them. They never know that the Five Ranks is the ship that carries them across the poisonous sea surrounding the rank o f the Real, the precious wheel that demolishes the impregnable prison-house of the two voids. They do not know the important road of progressive practice; they are not versed in the secret meaning within this teaching. Therefore they sink into the stagnant water of sravaka-hood or pratyeka-buddhahood. They fall into the black pit of withered sprouts and decayed seeds. Even the hand of Buddha would find it difficult to save them.

That into which I was initiated forty years ago in the room of Shoju I shall now dispense as the alms giving of Dharma. When I find a superior person who is studying the true and profound teaching and has experienced the Great Death, I shall give this secret transmission to him, since it was not designed for men of medium and lesser ability. Take heed and do not treat it lightly!

How vast is the expanse of the sea of the doctrine, how manifold are the gates of the teaching! Among these, to be sure, are a number of doctrines and orally transmitted secret teachings, yet never have I seen anything to equal the perversion of the Five Ranks, the carping criticism, the tortuous explanations, the adding of branch to branch, the piling up of entanglement upon entanglement. The truth is that the teachers who are guilty of this do not know for what principle the Five Ranks was instituted. Hence they confuse and bewilder their students to the point that even a Sariputra or an Ananda would find it difficult to judge correctly.

Or, could it be that our patriarchs delivered themselves of these absurdi ties in order to harass their posterity unnecessarily? For a long time I wondered about this. But, when I came to enter the room of Shoju, the rhinoceros of my previous doubt suddenly fell down dead... Do not look with suspicion upon the Five Ranks, saying that it is not the directly transmitted oral teaching of the Tozan line. You should know that it was only after he had completed his investigation of Tozan's Verses that Shoju gave his acknowledgment to the Five Ranks

After I had entered Shoju's room and received transmission from him, I was quite was satisfied. But, though I was satisfied, I still regretted that all teachers had not yet clearly explained the meaning of " the reciprocal interpenetration of the Apparent and the Real." They seemed to have discarded the words "reciprocal interpenetration," and to pay no attention whatsoever to them. Thereupon the rhinoceros of doubt once more raised its head.

In the summer of the first year of the Kan'en era (1748-1751), in the midst of my meditation, suddenly the mystery of "the reciprocal interpenetration of the Apparent and the Real " became perfectly clear. It was just like looking at the palm of my own hand. The rhinoceros of doubt instantly fell down dead, and I could scarcely bear the joy of it. Though I wished to hand it on to others, I was ashamed to squeeze out my old woman's stinking milk and soil the monk's mouths with it.

All of you who wish to plumb this deep source must make the investigation in secret with your entire body. My own toil has extended over these thirty years. Do not take this to be an easy task! Even if you should happen to break up the family and scatter the household, do not consider this enough. You must vow to pass through seven, or eight, or even nine thickets of brambles. And, when you have passed through the thickets of brambles, still do not consider this to be enough. Vow to investigate the secret teachings of the Five Ranks to the end.

For the past eight or nine years or more, I have been trying to incite all of you who boil your daily gruel over the same fire with me to study this great matter thoroughly, but more often than not you have taken it to be the doctrine of another house, and remained indifferent to it. Only a few among you have attained understanding of it. How deeply this grieves me! Have you never heard: " The Gates of Dharma are manifold; I vow to enter them all?" How much the more should this be true for the main principle of Buddhism and the essential road of sanzen!

Shoju Rojin has said: "In order to provide a means wher eby students might directly experience the Four Wisdom's, the patriarchs, in their compassion and with their skill in devising expedients, first instituted the Five Ranks." What are the so-called Four Wisdom's? They are the Great Perfect Mirror Wisdom, the Universal Nature Wisdom, the Marvelous Observing Wisdom, and the Perfecting-of-Action Wisdom.

Followers of the Way, even though you may have pursued your studies in the Threefold Learning continuously through many kalpas, if you have not directly experienced the Four Wisdoms, you are not permitted to call yourselves true sons of Buddha.

Followers of the way, if your investigation has been correct and complete, at the moment you smash open the dark cave of the eighth or Alaya consciousness, the precious light of the Great Perfect Mirror Wisdom instantly shines forth. But, strange to say, the light of the Great Perfect Mirror Wisdom is black like lacquer. This is what is called the rank of " The Apparent within the Real."

Having attained the Great Perfect Mirror Wisdom, you now enter the rank of "The Real within the Apparent." When you have accomplished your long practice of the jeweled-mirror Samadhi, you directly realize the Universal Nature Wisdom and for the first time enter the state of the unobstructed inter-penetration of Noumenon and phenomena.

But the disciple must not be satisfied here. He himself must enter into intimate acquaintance with the rank of " The Coming from within the Real." After that, by depending upon the rank of " The Arrival at Mutual Integration," he will completely prove the Marvelous Observing Wisdom and the Perfecting-of-Action Wisdom. At last he reaches the rank of " Unity Attained," and, after all, comes back to sit among the coals and ashes."

Do you know why? Pure gold that has gone through a thousand smeltings does not become ore a second time. My only fear is that a little gain will suffice you. How priceless is the merit gained through the step-by-step practice of the Five Ranks of the Apparent and the Real! By this practice you not only attain the Four Wisdoms, but you personally prove that the Three Bodies also are wholly embraced within your own body. Have you not read in the Daijo shogongyo ron: "When the eight consciousnesses are inverted, the Four Wisdoms are produced; when the Four Wisdoms are bound together, the Three Bodies are perfected?" Therefore Sokei Daishi composed this verse:

"Your own nature is provided

With the Three Bodies;

When its brightness is manifested,

The Four Wisdoms are attained."

He also said: "The pure Dharmakaya is your nature; the perfect Sambhogakaya is your wisdom; the myriad Nirmanakayas are your activities."

TOZAN RYOKAI'S VERSES ON THE FIVE RANKS

The Apparent within the Real:

In the third watch of the night

Before the moon appears,

No wonder when we meet

There is no recognition!

Still cherished in my heart

Is the beauty of earlier days.

The rank of "The Apparent within the Real" denotes the rank of the Absolute, the rank in which one experiences the Great Death, shouts "KA!" sees Tao, and enters into the Principle. When the true practitioner, filled with power from his secret study, meritorious achievements, and hidden practices, suddenly bursts through into this rank, " the empty sky vanishes and the iron mountain crumbles." "Above, there is not a tile to cover his head; below, there is not an inch of ground for him to stand on." The delusive passions are non-existent, enlightenment is non-existent, Samsara is non-existent, Nirvana is non-existent. This is the state of total empty solidity, without sound and without odor, like a bottomless clear pool. It is as if every fleck of cloud had been wiped from the vast sky.

Too often the disciple, considering that his attainment of this rank is the end of the Great Matter and his discernment of the Buddha-way complete, clings to it to the death and will not let go of it. Such as this is called it stagnant water " Zen; such a man is called " an evil spirit who keeps watch over the corpse in the coffin." Even though he remains absorbed in this state for thirty or forty years, he will never get out of the cave of the self-complacency and inferior fruits of pratyeka-buddhahood. Therefore it is said: "He whose activity does not leave this rank sinks into the poisonous sea." He is the man whom Buddha called " the fool who gets his realization in the rank of the Real."

Therefore, though as long as he remains in this hiding place of quietude, passivity and vacantness, inside and outside are transparent and his understanding perfectly clear, the moment the bright insight [he has thus far gained through his practice] comes into contact with differentiation's defiling conditions of turmoil and confusion, agitation and vexation, love and hate, he will find himself utterly helpless before them, and all the miseries of existence will press in upon him. It was in order to save him from this serious illness that the rank of " The Real within the Apparent " was established as an expedient.

The Real within the Apparent:

A sleepy-eyed grandam

Encounters herself in an old mirror.

Clearly she sees a face,

But it doesn't resemble her at all.

Too bad, with a muddled head,

She tries to recognize her reflection!

If the disciple had remained in the rank of "The Apparent within the Real," his judgment would always have been vacillating and his view prejudiced. Therefore, the bodhisattva of superior capacity invariably leads his daily life in the realm of the [six] dusts, the realm of all kinds of ever-changing differentiation. All the myriad phenomena before his eyes-the old and the young, the honorable and the base, halls and pavilions, verandahs and corridors, plants and trees, mountains and rivers-he regards as his own original, true, and pure aspect. It is just like looking into a bright mirror and seeing his own face in it. If he continues for a long time to observe everything everywhere with this radiant insight, all appearances of themselves become the jeweled mirror of his own house, and he becomes the jeweled mirror of their houses as well. Eihei has said: "The experiencing of the manifold dharmas through using oneself is delusion; the experiencing of oneself through the coming of the manifold dharmas is satori." This is just what I have been saying. This is the state of " mind and body discarded, discarded mind and body." It is like two mirrors mutually reflecting one another without even the shadow of an image between. Mind and the objects of mind are one and the same; things and oneself are not two. " A white horse enters the reed flowers snow is piled up in a silver bowl."

This is what is known as the jeweled-mirror Samadhi. This is what the Nirvana Sutra is speaking about when i t says: " The Tathagata sees the Buddha-nature with his own eyes." When you have entered this samadhi, " though you push the great white ox, he does not go away"; the Universal Nature Wisdom manifests itself before your very eyes. This is what is meant by the expressions, "There exists only one Vehicle," "the Middle Path," " the True Form," " the Supreme Truth."

But, if the student, having reached this state, were to be satisfied with it, then, as before, he would be living in the deep pit of " fixation in a lesser rank of bodhisattvahood." Why is this so? Because he is neither conversant with the deportment of the bodhisattva, nor does he understand the causal conditions for a Buddha-land. Although he has a clear understanding of the Universal and True Wisdom, he cannot cause to shine forth the Marvelous Wisdom that comprehends the unobstructed interpenetration of the manifold dharmas. The patriarchs, in order to save him from this calamity, have provided the rank of "The Coming from within the Real."

The Coming from within the Real:

Within nothingness there is a path

Leading away from the dusts of the world.

Even if you observe the taboo

On the present emperor's name,

You will surpass that eloquent one of yore

Who silenced every tongue.

In this rank, the Mahayana bodhisattva does not remain in the state of attainment that he has realized, but from the midst of the sea of effortlessness he lets his great uncaused compassion shine forth. Standing upon the four pure and great Universal Vows, he lashes forward the Dharma-wheel of " seeking Bodhi above and saving sentient beings below." This is the so-called "coming-from within the going-to, the going-to within the coming-from." Moreover, he must know the moment of [the meeting of] the paired opposites, brightness and darkness. Therefore the rank of " The Arrival at Mutual Integration " has been set up.

The Arrival at Mutual Integration:

When two blades cross points,

There's no need to withdraw.

The master swordsman

Is like the lotus blooming in the fire.

Such a man has in and of himself

A heaven-soaring spirit.

In this rank, the bodhisattva of indomitable spirit turns the Dharma-wheel of the non-duality of brightness and darkness. He stands in the midst of the filth of the world, "his head covered with dust and his face streaked with dirt." He moves through the confusion of sound and sensual pleasure, buffeted this way and buffeted that. He is like the fire-blooming lotus, that, on encountering the f lames, becomes still brighter in color and purer in fragrance. " He enters the market place with empty hands," yet others receive benefit from him. This is what is called to be on the road, yet not to have left the house; to have left the house, yet not to be on the road." Is he an ordinary man? Is he a sage? The evil ones and the heretics cannot discern him. Even the buddhas and the patriarchs cannot lay their hands upon him. Were anyone to try to indicate his mind, [it would be no more there than] the horns of a rabbit or the hairs of a tortoise that have gone beyond the farthest mountain.

Still, he must not consider this state to be his final resting-place. Therefore it is said, "Such a man has in and of himself a heaven-soaring spirit." What must he do in the end? He must know that there is one more rank, the rank of " Unity Attained."

Unity Attained:

Who dares to equal him

Who falls into neither being nor non-being!

All men want to leave

The current of ordinary life,

But he, after all, comes back

To sit among the coals and ashes.

The Master's verse-comment says:

How many times has Tokuun, the idle old gimlet,

Not come down from the Marvelous Peak!

He hires foolish wise men to bring snow,

And he and they together fill up the well.

The student who wishes to pass through Tozan's rank of " Unity Attained " should first study this verse.

It is of the utmost importance to study and pass through the Five Ranks, to attain penetrating insight into them, and to be totally without fixation or hesitation. But, though your own personal study of the Five Ranks comes to an end, the Buddha-way stretches endlessly and there are no tarrying places on it. The Gates of Dharma are manifold.

Zen

Master Hakuin's

Letter in Answer to an Old Nun of the Hokke [Nichiren] Sect

The 25th day of the Eleventh Month of Enkyo 4

(C.E. 1747)

http://campross.crosswinds.net/library/Hakuin.html

This fall when I gave my lectures on the Lotus Sutra I said that outside the mind there was no Lotus Sutra and outside the Lotus Sutra there was no mind. Thinking what you heard to be strange, you have written to ask me to explain to you the principle I expounded and to tell you of any other pertinent matters. In this letter I shall deal largely with the import of what I said, and ask you to read and reread what I write, in the hope that it will prove to be to your satisfaction.

I do indeed always say: Outside the mind there is no Lotus Sutra and outside the Lotus Sutra there is no mind. Outside the ten stages of existence there is no mind and outside the ten stages of existence there is no Lotus Sutra. This is the ultimate and absolute principle. It is not limited to me, but all the Tathagata of the three periods, and all learned sages everywhere, when they have reached the ultimate understanding, have all preached the same way. The essential purport of the text of the Lotus Sutra speaks gloriously to this effect. There are eighty-four thousand other gates to Buddhism, but they are all provisional teachings and cannot be regarded as other than expediencies. When this ultimate is reached, all sentient beings and all Tathagata of the three periods, mountains, rivers, the great earth, and the Lotus Sutra itself, all bespeak the Dharma principle that all things are a non-dual unity representing the true appearance of all things. This is the fundamental principle of Buddhism. We have indeed the 5,418 texts of the Tripitaka, that detail the limitless mysterious meaning spoken by Shakyamuni Buddha. We have the sudden, gradual, esoteric, and indeterminate methods. But their ultimate principle is reduced to the 8 volumes of the Lotus Sutra. The ultimate meaning of the 64,360-odd written characters of the Lotus Sutra is reduced to the 5 characters in its title: Myoho-renge-kyo. These 5 characters are reduced to the 2 characters Myoho [Wondrous Law] and the 2 characters Myoho return to the one word mind. If one asks to where this one word, mind, returns: "The horned rabbit and the furry turtle cross to nowhere mountain." What is the ultimate meaning? "If you wish to know the mind of one who laments in the midst of spring, it is at the time when the needle is stopped and words cannot be spoken."

This One Mind, derived from the two characters Myoho mentioned above, when spread out includes all the Dharma worlds of the ten directions, and when contracted returns to the no-thought and no-mind of the self-nature. Therefore such things as "outside the mind no thing exists," "in the three worlds there is One Mind alone," and "the true appearance of all things," have been preached. Reaching this ultimate place is called the Lotus Sutra, or the Buddha of Infinite Light; in Zen it is called the Original Face, in Shingon the Sun Disc of the Inherent Nature of the Letter A, in Ritsu the Basic, Intangible Form of the Precepts. Everyone must realize that these are all different names for the One Mind.

One may ask: "What proof is there that the five characters Myoho renge kyo point to the fountainhead of the one mind?" These five characters, just as they are, immediately serve as proof that can readily be substantiated. Why? Myoho renge kyo is a title that sings the praises of the mysterious virtues of the One Mind. It is composed of words that point to and reveal the inherent character of this One Mind, with which all men are innately endowed.

To be more speficic, look at calligraphy and painting. Or better, when someone says that so-and-so has a genius for peforming on the biwa or the koto, if we ask just where that genius lies, nobody, no matter how eloquent or gifted of tongue he may be, will ever be able to explain it in words. We cannot teach this uninherited talent to the child that we cherish. But when this mysterious spot is touched upon, it operates unconsiously, emerging from some unknown place. The mysterious nature of the mind with which all people are endowed is like this.

You may laugh or gossip when you read this letter, but is this not a strange thing, endless as a thread from a reel, that reveals its activity without a trace of error in any one you meet? But if you ask what thing is this that acts freely in this way, and look inward to seek it there, you will find that it has neither voice nor smell. Furthermore, it is empty and without traces, and if you think it is something like wood or stone, being free and unattached, it will change endless times. If you say it is in existence it will not be there; if you say it is in non-existence it will not be there either. This place, where words and speech are cut off, this free and untrammeled place, is provisionally called the Wondrous Law (Myoho). The Lotus (renge), while its roots lie in the mud, is in no way soiled by the mud, nor does it lose the wonderful scent and odor with which it is blessed. When the time comes for it to bloom it sets forth beautiful blossoms. The Wondrous Law of the Buddha mind is neither sullied nor does it decrease within sentient beings and it is neither made pure nor does it increase within a Buddha. In the Buddha, in the common man, among all sentient beings it is in no way different. To be sullied by the mud of the five desires is to be just like the lotus root lying covered by the mud.

Later in the Himalaya the Buddha discovered the nature of the mind that is endowed from the outset. He called in his noble voice: "How marvelous! All sentient beings are endowed with the wisdom and the virtuous characteristics of the Tathagata. He preached the sudden and the gradual teaching and the partial and complete doctrines of the various sutras, and became himself the great teacher of the three worlds. When he is venerated by Brahma and Sakra, it is as though the lotus had emerged from the mud and opened its full beauty. Just as the lotus's color and fragrance inhere in it as it lies in the mud, as it emerges, and as it blooms above the surface, so when the Buddha spoke of the Dharma being as numerous as the sands in the Ganges, he referred to nothing that was brought in from the outside. In terms of the common man, he spoke of the appearance of the Buddha-nature itself, with which all are without a doubt endowed; in terms of sentient beings, once the vow to become a Buddha has been made, the Wondrous Law of the One Mind does not increase nor lessen one bit. It is just the same as the lotus: at the time that it lies amidst the mud and after its blossoms are scattered in the summer, it does not undergo any fundamental change whatsoever. Thus he provisionally likened the lotus plant to the Wondrous Law of the One Mind. Is this not irrefutable proof that the Buddha mind, with which all people are endowed, was called the Lotus Sutra of the Wondrous Law?

The word kyo [sutra] means "constant," in the same sense as the eternal, unchanging Buddha-nature. This kyo teaches that the eternal, unchanging Buddha-nature does not increase in a Buddha nor decrease in a sentient being. It is of the same root as heaven and earth and is one substance with all things, and has not changed one iota since before the last kalpa began, nor will it change after it has ended. Moreover, Myoho [Wondrous Law] is the substance of the Buddha mind. The Lotus Sutra was composed as a way of praising this Wondrous Law of the Buddha mind, and so it is nothing more than another name for the One Mind. It is one reality with two names, just as mochi and kachin are two names for the same thing, a rice-cake.

Moreover, the True Reality that is the Lotus Sutra cannot be seized by the hands nor seen by the eye. How then is one to receive and hold to it? What then should one say to the practitioner of the Lotus Sutra who wishes to take it to himself? There are three types of capacity. The practitioner of inferior capacity is captivated by the yellow scroll with its red handles and copies, recites, and makes explanations of it. The practitioner of average capacity, illuminates his own mind and so receives and holds to the Sutra. The person of superior capacity penetrates this Sutra with his [Dharma] eye, just as though he were viewing the surface of his own mind. That is why the Nirvana Sutra says: "The Tathagata sees the Buddha-nature within his eye." The practitioner of the Lotus Sutra, if he is engaged in the true practice of the ultimate of Mahayana, will not find it an easy thing to do. What is simple is very much so; what is difficult is very, very difficult indeed.

We have seen before the passage in the Lotus Sutra that reads: "To hold to this Sutra is difficult. If someone holds to it even for a short while, I will feel great joy and the many Buddhas likewise." Thus, the practice of holding to this Sutra is of the utmost importance. Chih-i of the Tendai school has said: "Without taking the book in your hands, always recite this Sutra. Without uttering words from your mouth, recite all the texts everywhere. Even when the Buddha does not preach always listen to the sound of the Law. Without engaging the mind in thinking, always illumine the Dharmakaya." This describes the true recitation of this Sutra. Should someone ask: "What sort of a sutra is this that one recites without taking the work up in one's hands?" can one not say in return, "Isn't this the Wondrous Law of your own mind?" If someone asks: "What does 'without engaging the mind in thinking, always illumine the Dharmakaya' mean?" can one not say in return, "Isn't this the True Lotus?" This is known as the Sutra without words. If one just grasps the yellow roll with its red handles and holds to the belief that this is the Lotus Sutra, one is like someone who licks a piece of paper extolling the virtues of some medicine, expecting that this will serve to cure a disease. What a great mistake this is!

Should a person wish to hold this Sutra, he must throughout all the hours of the day and night without the slightest doubt in his mind, carry on the real practice of true meditation on the total form of all things, thinking neither good nor of evil. In this respect Han-shan, who was an avatar of Manjusri, has said in a verse: "If you wish to attain the road to enlightenment, let no thread hang in your mind." True practice of this sort is the ancient and changeless great center, the place from which all the Tathagatas of the three periods and all the wise men and great priests attained to great enlightenment. This is the direct road to [experiencing the state in which] "no-thought is produced, before and after are cut off, and with sudden enlightenment you attain to Buddhahood." Although the Tathagata said, "This Sutra is difficult to hold to," is this not really the ultimate principle? The true place to which the sages of all three religions have attained is, to a large measure, the same. Although the degrees of efficacy is based on the depth and the quality of the perseverance in practice, the content of the first step is the same. The Confucians call this place the Ultimate Good, the Undeveloped Mean. Taoists call it Nothingness or Nature. Among Shintoists it is known as Takamagahara. The Tendai school calls it "the Great Matter of the cessation and meditation on the three thousand worlds in one instant of thought." In Shingon it is called "the contemplation of the Inherent Nature of the Letter A."

The Patriarchs of the various schools encourage sitting in meditation and, although they advocate the recitation of the sutras, isn't this recitation merely a device to make us reach the state where the mind is unperturbed, pure, and without distractions? The founder of Eihei-ji has said: "If one practices and holds to it for one day, it is worthy of veneration; if one fails to hold to and practice it for a hundred years, these are a hundred years of regret." It is enough to make one shed tears at the regrettable and wretched state of understanding in which, while possessing the difficult-to-obtain body of a man, a person does not cultivate in himself the determination to practice. Instead, like a dog or a cat or some beast that has no understanding at all, he allows his whole life, one so difficult to encounter, to rot carelessly away, and returns to his old abode in the three worlds of suffering, without having learned a thing. To say "a difficult thing is very, very difficult," leaves no doubt on our part. But what does this "an easy thing is very easy indeed" mean? Should a person release his hold on the Sutra and attempt lightly to maintain the dignities of walking, standing, sitting, and reclining, he must make a vow seeking once to verify for himself the True Face of the Lotus. Once a person sees this True Face of the Lotus, then coughing, swallowing, waving the arms, activity and quietude, words and actions, all plants, trees, tiles, stones, the sentient and the non-sentient, all manifest the Sutra of the Wondrous Law, and throughout all the hours of the day, harmonize deeply with the Sutra. What need is there to hold to any other thing? If you try to hold to the Lotus Sutra without seeing once the True Lotus, you will be like a man who holds a bowl of water in his hands and night and day tries to keep from spilling it or letting it move, but still expects to gain sustenence from it. Even if he should succeed in holding it in this way for his whole life, he wouldn't be able to sustain himself or keep himself from dying of thirst. His hopes to benefit himself and others by the practice of the vow will be cut off midway. What possible use does this serve?

For the person who once sees the True Lotus and holds to the Sutra, it is as if he had poured this one bowl of water into rivers and lakes everywhere. At once it merges with the thirty-six thousand riplets and its beneficence joins with the waters, so that if all the creatures that leap, run, fly, or crawl came to drink at the same time, it would never be exhausted.

The person who has not seen the True Lotus is like the man who holds the bowl of water. Not only can he be of no benefit to others, but neither can he bring benefit to himself. The person who once sees the True Lotus is like the man who pours the bowl of water into all the rivers and lakes. Unconsciously he leaps into the great sea of Nirvana of the various Buddhas, harmonizes deeply with the true Dharma body and the precepts, meditation, and wisdom of the many Buddhas, at once shatters the dark cave of the alaya-consciousness, and releases the Illumination of the Great Perfect Mirror. Passing over numberless kalpas, he practices the almsgiving of the Dharma with no limitations whatsoever. The breadth and greatness of the virtue of the one view of the Lotus is quite without bounds. Rather than read all the works in the Tripitaka, see the True Lotus once. Rather than make a million statues of the Buddha, see the True Lotus once. Rather than adhering to the view that holding a yellow scroll with its red handles is [the practice of] the Lotus Sutra, see the True Lotus once. Rather than recite the Lotus Sutra a billion times, see the True Lotus once with your own Dharma eye. This is truly a lofty statement of complete truth and indestructibility.

How can one penetrate to the True Face of the Lotus? To do this one must raise the great ball of doubt. What is being pointed out when we speak of the True Face of the Lotus? It is the Wondrous Law of the One Mind, with which you yourself are endowed from the outset. It is nothing more than to see into your own mind. And what is this "own mind?" Don't look for something white or something red, but by all means see it at once. Courageousely and firmly establish your aspiration, raise up the great vow, and night and day investigate it to the end. For investigating the mind there are many methods. If you are a practitioner of the Lotus Sutra who ignores the teachings of other schools, then you must transcend the practice of the Lotus Samadhi. The practice of the Lotus Samadhi is from today on to determine, despite happiness and pain, sadness and joy, whether asleep or awake, standing or reclining, to intone without interuption the title of the Sutra alone: Reverence to the Lotus of the Wondrous Law Namu Myoho Renge Kyo. Whether you use this title as a staff or as a source of strength, you must recite it with the fervent wish to see without fail the True Face of the Lotus. Make each inhalation and exhalation of your breath the title of the Sutra. Recite it without ceasing with intense devotion. If you recite it without flagging, it will not be long before the mind-nature will truly be set as firmly as a large rock. Dimly you will gain an awareness of a state in which the One Mind is without disturbance. At this time, do not discard this awareness, but continue your constant recitation. Then you will awaken to the Great Matter of true meditation, and all the ordinary consciousnesses and emotions will not operate. It will be as if you had entered into the Diamond Spere, as if you were seated within a lapis lazuli vase, and, without any discriminating thought at all, suddenly you will be no different from one who has died the Great Death. After you have returned to life, unconsciouslessly the pure and uninvolved true principle of undistracted meditation will appear before you. You will see right before you, in the place where you stand, the True Face of the Lotus, and at once you body and mind will drop off. The true, unlimited, eternal, perfected Tathagata will manifest himself clearly before your eyes and never depart, though you should attempt to drive him away. This is the time that the Tendai school refers to as "plunging into the treasure abode, where the Dharma-nature is undisturbed, yet constantly illuminating." In Shingon it is to be illumined by the Sun Disc of the Inherent Nature of the Letter A. In the Ritsu it is the harmonize with the unparalleled Diamond-Treasure Precepts of the Many Buddhas. In the Pure Land School it is to fulfill one's vow for rebirth in Paradise, to see before one's eyes the marvelous birds and trees of Paradise and to keep constantly in mind the wondrous ornamentation of the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha.

Opening the True Eye that sees that his very world is itself the brillance of Nirvana, one reaches the state where all plants, trees, and lands have without the slightest doubt attained to Buddhahood. What is there among the good fruits of the worlds of men and devas that can be compared to this? This is the basic vow that accounts for the appearance in this world of the many Buddhas of the three periods. One recitation of the title of this Sutra has no less virtue than a single Zen koan. The purport of all this has been uttered by all the learned sages of all the directions of the three periods and the eighty thousand gods of Japan. If what I say were even slightly incorrect, why should I risk committing a crime by writing it all in a long-winded letter? There is absolutely no doubt about it. If in one's practice one is not remiss, the mind-ground known in Zen as "clenching the left hand and biting the middle finger," will gradually become clear.

Nowadays one occassionally hears people say: "There is no point in studying koans under a teacher. What do you do after finishing your study of the koans? [Once you have reached the stage of the] direct pointing to 'this very mind is Buddha,' you neither regret when a thought arises nor feel joy when a thought is stopped. The mountain villager's unpainted bowl is best, for it represents the original nature as it was at the time that the bowl was made. If you don't lacquer the bowl, there will be nothing to chip and wear away." People who talk in this way are like blind turtles that pointlessly enter an empty valley every day and are satisfied with this. This is the view of the Indian heretics of the naturalistic school. If things like this were called the pivot of the progress toward the Buddha mind, even the guardian gods of the remotest village would clap their hands and burst out in laughter.

Why is this so? Aren't such people similar to the imbecile who thinks he see the spirits that Ch'ang-sha talks about? When the Surangama Sutra cautions against recognizing a robber and making him your son and talks of the eventual inability to know the substance of original purity, it is referring to people of this type. They are totally unaware of the fact that the Tathagata did not acknowledge proficiency in meditation even for those sages who had gained the four grades of sainthood, had reached the state of non-retrogression, had penetrated the principles of the self and the dharmas, were endowed with magical gifts, and had gained great fame everywhere. That is why the Sutra says: "Even the great arhats among my disciples cannot understand the meaning. It is only the group of bodhisattvas who are able to comprehend it." It is speaking of those who, without even possessing the accomplishment of seeing into their own natures, recklessly call themselves worthy of veneration. What sort of mental state is this?

At any rate, nothing surpasses the casting aside of all the myriad circumstances and devoting oneself to recitation. But do not adhere to the one-sided view that the title of the Sutra alone will be of benefit. This applies as well to the Shingon and Pure Land schools. The followes of the Pure Land, by the power of the concentrated recitation of the Buddha's name, resolving to see once the Pure Land of their own minds and the wondrous form of Amida Buddha in their own bodies, give rise to a valiant great aspiration, and devote themselves ceaselessly to the recitation of the name, as fervently as though they were dousing flames on their own heads. Is there any reason that they should not see the form of the Buddha, who is spoken of as not being far off, the trees of the seven treasures, and the pond of the eight virtues? The followers of Shingon, by the mysterious power of the dharani resolving to see without fail the great Sun Disc of the Inherent Nature of the Letter A, give rise to a great aspiration to persevere, just as in Zen one koan is taken up and concentrated upon. Is there any reason that they should not polish and bring out the true form of the Diamond indestructible that Koya Daishi has described as "[attaining enlightenment] without being reborn in a new body"?

But should any one of these people, thinking he has saved up merit, talk about waiting until after he dies, he will find that his ignorance and carelessness have resulted in a situation almost without hope. Do not lament about how far away it is. Is there anything nearer than to see your own eyeballs with your own eyeballs? Do not be afraid about how deep a thing is. If you try to see and hear it at the bottom of a deep chasm or in the depths of the sea, then you may well fear how deep a thing is. Is there anything nearer than to see your own mind with your own mind, to use your own nostrils to smell your own nose? Although the world is in a degenerate age, the Law itself is not degenerate. If you take the world as degenerate and cast it away without looking back, you will be like someone who enters into a treasure mountain, yet suffers from hunger and cold. Do not fear that because this is a degenerate age [enlightenment] cannot be accomplised. In the past the Abbot of the Eshin-in, more recently Sokuo of Akazawa and Engu of Yamashiro, and the sick girl of Osaka, each by the power of the calling of the name, fulfilled the vow described above. Honen Shonin also had this aspiration deeply, but because he had no religious guide, he said that the state of his mind was as though his wings were too short for so long a flight.

Perhaps it is a mark of this degenerate age that recently bad customs have arisen and monks and laymen are both so accustomed to seeing and hearing of them that they say that to want to see the Buddha Mind of the Wondrous Law today is like having the apsirations of an eel that wants to climb a tree. Yet to spend one's whole life in darkness certainly represents a miserable state of mind.

Supposing several sons of a farmer have inherited from him a large amount of land. Among the sons is one who is weak and unworthy, but whose words are clever and shrewd. He says: "In these days it is beyond the ability of people of our humble status to imitate our ancestors of old, to angage in agriculture and farming, and to attempt to raise a large family. It would be just like a duck, in imitation of a hawk, positioning its wings as though it were about to attack and bring down a crane. Or like a lame turtle, in imitation of a carp, stretching out its neck as though it were about to ascend a waterfall. Ridiculous! If we continue in this way, we'll end up having to drink water from a sickle. This is quite unthinkable! Just figure it out for yourselves! Worn out people such as we [must tend] this farm, that stretches like a vast field filled with luxuriantly growing weeds. We cut the fields and after they are cut, we cultivate. We irrigate, hoe, sow the seeds, transplant the seedlings, weed the paddies, cut and dry the plants, remove the rice, and polish off the rice bran. Then we must braid the rope and weave matting and make bales. When we can sit back and look at the results, we are struck by the tremendous difficulties of the work. It is indeed an old story. The results are worth nothing at all. There is a much better way to pass through this world, taking your ease with your hands in your sleeves. Wherever a person's feet take him, he can spend three days here or five days there."

Someone objected, saying: "If we have shoulders, don't we need clothes to hang on them? If we have a mouth, don't we need food to put in it?"

To this he replied: "I have heard that a certain lord of a certain province is a man of great humanity. They say he gives stipends to such as we. This is were we really ought to go. With things as good as that, we would have nothing to lament about. It's all a great mistake to move one's hands and feet to earn a living through one's own efforts. There is nothing to worry about. It's best just to put on a humble appearance from the beginning and make no effort to work. Do not look as if you wanted to pile up money."

Throwing away the two or three old garments they have and putting on clothes of straw matting, people like this say: "We are impoverished and inferior beings, lost, with no place to stay and no one to tell our troubles to. Out of pity, please help us." Wandering about crying in this way, because of the compassion that exists in the world, it is not impossible for a person to be fed. People are taught such things and rejoice without a trace of doubt, believing all this to be true. Thus they become poverty stricken, although they were not so from birth, and end up spending their lives in this way.

Such people are known as destroyers and wasters of their own selves. The Master Lin-chi berated them as "spoiled people of inferior capacity." They are like fish in water who lament the fact that because of their natures they are unable to see the water, or like birds flying through the air who regret the fact that to see the air is an unattainable desire. They are unaware that of all the lands everywhere, there is none that does not contain True Reality, nor is there any human being anywhere who is not endowed with this Wondrous Law. It is a pity that while living amidst the Wondrous Law of the One Mind and the Pure Land of Tranquil Light, they cling to the prejudice that in this life they are part of the ordinary world and that as sentient beings they are as such deluded. Mistakenly they believe that after death they will enter hell, and so they lament the endless torment in store for them. They discard the Buddha Mind of the Wondrous Law that wells up before the eyes and the Dharma-nature of True Reality that is always pure, feeling that these are things to which they cannot possibly attain, things for which they cannot possibly hope. Thus they cast aside their desires as unobtainable, and look for the pointless concepts of deluded consciousness, and end up spending their lives in vain. What is most regrettable is that, although we have this Lotus of the Wondrous Law, incomparable in all the three worlds, a scripture of the most exquisite quality, yet, because there is no one who practices its teachings properly, it is stuffed away on library shelves along with a lot of ordinary books, and rots away from disuse. Thus people mistake the impure world for the Pure Land and concern themselves with the three evil paths and the six modes of existence. Is there anything more lamentable?

Someone has asked: "What specifically does this teaching point to? Is it the four peaceful contentments? Is it the conduct of the five types of Master of the Law?"

In answer I say: "Not at all. It is the 'eye' of the Sutra, that is described in the text of the chapter on Expediencies in these words: 'the reason the Buddha appeared in this world was [to show] the way to open up the wisdom of the Buddha.'"

Although the numerous Tathagatas who have appeared successively in the world have expounded Laws as numerous as the sands in the Ganges, they have all appeared solely for the purpose of opening up the Buddha's wisdom to all sentient beings. No matter what Law you practice, if you don't seek to open up the Buddha's wisdom, you will never be able to come into accord with the vow of the many Buddhas. The opening up of the Buddha's wisdom is to make clear the Wondrous Law of the One Mind. There is nothing more regrettable in this degenerate world than to discard tidings of this Wondrous Law of the One Mind and to just go along as one pleases. When unexpectedly we meet something that seems to be this Wondrous Law, we find that nowadays everyone has made it into an intellectual teaching, scarcely worth talking about. No one gives heed to the saying in the Maha-Vairocana Sutra: "Know your own mind as it really is." Not following the teaching of the Lotus Sutra and not knowing where the Wondrous Law is, people rush about madly, saying vague things like: "It's in the West," or "It's in the East," and spend their days declaring that this or that is the Buddha Way. Their behavior can be likened to that of the people in the following story.

Supposing that there were a very rich man, who, after undergoing many hardship, finally managed to bring under cultivation vast tracts of land. Supposing that he were to say to his sons: "You cultivate this land and become rick men like me." He then distributes to his various sons, without regard to the capacities of each, his excess lands. His sons, however, do not follow their father's teaching, but scatter to various provinces. Some stand beside the doors of people's houses and beg their food. Some say: "We are mirror polishers," and walk about polishing tiles. Others scuttle about chasing away the birds that feed on grain. Some say: "We are millionaire's sons," and although looking like beggers and outcasts themselves, they recklessly make light of others. Some turn over the leaves of their account books every day, but do not even know what the fields look like. Others say: "As long as we have our acocunt books we have nothing to fear," and selfishly practice their evil ways. Some say: "We know the conduct becoming to a millionaire," but they starve and thirst while practicing the forms of this proper conduct. There are some who do not even know where the fields are, but keep screaming about them day and night. Others are a bit aware of the vast extent of acreage and, becoming greatly boastful, degenerate into a life of sex, wine, and meat-eating. There is not one son among them who carries out the intention of his millionaire father.

The fields stand for the Wondrous Law of the One Mind. The account books are the sacred scriptures. "To stand before people's houses and beg," means to acknowledge the Great Matter of the opening up of the wisdom of the Buddha, the process of learning for oneself whether the water is cold or hot by experiencing in one's own body pain and suffering, and then, because this is a degenerate age, to accept the teachings of others, to hear and learn things that are not the substance, and to consider this to be enlightenment. Is this not like the prodigal son in the Lotus Sutra?

In the Mahayana sutras even the four grades of sainthood of an arhat are condemned as representing ordinary men of the two vehicles. If this [enlightenment] is such an absurd and uncomplicated thing as people say, why then did the Buddha confine himself in the Himalaya for six years until his skin stuck to his bones and he was so emaciated and exhausted that he looked like a tile made to stand by winding string around it? He was unaware that the reeds had pierced his lap and reached to his elbows; so absorbed was he in his painful introspection that he was not conscious of the lightning striking down horses and cattle before his very eyes. Imagine what a thing it was for the first time he opened up the wisdom of a Buddha!

The Buddha Way from ancient times has been one of vast difficulties. Is it something that should be made easy now? Is it something like radishes, potatoes, or chestnuts that are hard at first but get soft when cooked? If what is easy today is good, then what was difficult in the past must be bad. What was difficult in the past was the painful introspection, and this was a very painful introspection indeed. With the smallest bit of development and progress, suddenly the state of sage, Buddha, or Patriarch was reached. When that place, when this time was transcended and [understanding] touched upon even to the slightest degree, then lightning flashed and the stars leapt in the sky. The surpassing easiness of today is surpassing indeed, yet when you look into it, it is no more than a painting of a wise monk. With the smallest bit of development and progress, you are still as before, like a fish stuck in a trap, like a lame turtle fallen into an earthen jar. This time and that place are not transcended, and, as you press on, you are like a blind ass walking on ice.

Which will it be, the easiness of the present-day practice or the difficulty of that of the past? No matter how much you insist that this is after all a degenerate ago, to speak in such terms is useless. Even the men of old knew that later the teaching of Zen and the true form [of the Lotus] were destined to perish. Let it be known that to seek the Wondrous Mind on soiled paper or to assign the True Law to verbal discussions is indeed a pathetic thing. If everything could be accomplished through the use of written words and talk, then Shen-kuang would not have had to cut off his arm, Hsuan-sha would not have have injured his foot, Hosshin's head would not have swollen, and Hatto would not have shed tears. No matter what other people do, you must determine that "come what may, I will without fail intone the title [of the Lotus Sutra] day and night and see for myself the form of the Lotus." Then, if you intone it faithfully, without having to enter the Himalaya or to bear the suffering of having your head swell, the real essential Lotus of the Wondrous Law of your own nature will open in all its beauty. The essential point is to resolve not to give in while you have yet to see the Wondrous Lotus of your own mind. Then there will be nothing so venerable as this thing to which you have devoted all your hopes. When the Tathagata, the World-honored One, had still to see the Wondrous Law of his one mind, he was no different from any ordinary mortal, endlessly sunk in the rounds of birth an death, and he himself was constantly dying and being reborn. Later in the Himalaya he awoke to the Wondrous Law of his own mind and for the first time achieved True Enlightenment.

The polishing of

a tile is to think that as long as one recognizes the non-differentiation of

the alaya-consciousness and is not deluded into thinking that this represents

the original face, then what is left is a Buddha mind that is like a mirror.

People are taught merely that everything is reflected in the mirror just as

it is; the crow is black, the crane white, the willow green, and flower red,

and they are told to strive constantly to polish [the mirror] so that not a

speck of dust can collect. This wiping away of deluded thoughts night and day

is the same as polishing a tile or chasing away birds that feed on millet. This

is known as seeking for the spirit. It permits no chance for the luminescence

to be produced that make clear the mountains, rivers, and the great earth. Practice

of this sort was fairly frequent even during the T'ang dynasty. Nan-yueh's polishing

of a tile before Ma-tsu's hut was for the purpose of conveying this meaning

to Ma-tsu.

Thus Ch'ang-sha has said in a verse:

The failure of the student to understand the truth,

Comes from his prior acceptance of spirits.

The basis of birth and death from endless kalpas in the past;

This the fool thinks of as the original man.

It is for this reason that Patriarchs such as Tz'u-ming, Chen-ching, Hsi-keng, and Ta-hui were indescribably kind in gritting their teeth and attempting to drive out such concepts. There is no point in bringing up the views of all the other Masters on this subject. There is no Buddha or Patriarch in the three periods and ten directions who has not seen into his own nature. This is the eternal, unchanging center of the teaching. To see into your own nature is to see for yourself the True Face of the Lotus. If you do not have this desire, but that that all varieties of things are the Buddhadharma, you will be like a band of children that rushes to board a large boat that has no captain. They do not know where they wish to go nor what the harbor of their destination is. Crying, "Let's row over here." or "Let's row over there," they pull the oars any which way--yesterday they drifted following the tide to the east, today they drift following the tide to the west--and in the end they are hopelessly lost at sea. Then suddenly a captain who knows the way appears in the boat and, setting his compass, takes the rudder and within the day reaches the harbor of his destination.

The captain is the great aspiration to see into one's own nature. The compass is the teaching of the True Law. The rudder is the determination and conduct throughout one's life. How is one to row into the harbor of the Wondrous Law? Ordinary practitioners seek the Buddha, seek the Patriarchs, seek Nirvana, or seek the Pure Land. They are accustomed always to rowing to the outside. Therefore, the more they seek the further away from their goal they are.

The practitioner of the true Wondrous Law is not like this. Purusing the investigation of what sort of thing is his own innate Wondrous Law is, he seeks neither the Buddha nor the Patriarchs. He does not say that the Wondrous Law is inside or that it is outside. No matter where it is, no matter what color it is, he will not let things be until he has finally seen it once. All day long, everywhere, without interruption, strenuously, bravely, he forces his spirit on. Refusing to leave what he has resolved to accomplish unfinished, asleep, awake, while standing, while reclining, he does not cast it aside. Night and day he examines things; at times he goes over things again. Constantly, he proceeds, asking, "What is this thing, what is this thing? Who am I?" This is called the way of "the lion that bites the man." To proceed asking only, "What is the Wondrous Law of the Mind?" is called the way of "a fine dog chasing a clod of dirt." Just under all circumstances cast aside all things, become without thought and without mind and intone: "Namu Myoho Renge Kyo, Namu Myoho Renge Kyo, Reverence to the Lotus of the Wondrous Law." If you think that this old monk has any Dharma principle better than this to write of, you are terribly mistaken. Namu Myoho Renge Kyo, "Reverence to the Lotus of the Wondrous Law."

Written by the old monk under the Sala tree.

25th day of the eleventh month of Enkyo 4 [= Dec. 26, 1747]

Although this long, tedious letter may be difficult to read, please show it to others at your hermitage. I have written it in the hope that it will also serve as the almsgiving of the Dharma. I wish that you will without fail see the Ultimate Principle, the Wondrous Law of your own mind. With the wish that you will continue to intone ceaselessly the title: Namu Myoho Renge Kyo, "Reverence to the Lotus of the Wondrous Law."

Supplement: Kambun text appended to letter

After I had written the draft of this letter I read it over carefully. At that time a monk who had long been a friend of mine was sitting beside me. He read what I had written and when he came to the part about the True Face of the Lotus, he let out a long sigh and said, "Master, are you handing out a yellow leaf to keep the child from crying?"

The color drained from my face and I replied: "What are you talking about? Are you saying that what I have written is only worth a red leaf? This is real gold, not a red leaf. I wrote it to bring out the basic meaning of the Lotus Sutra. By calling it a read leaf aren't you slandering the Sutra? Crimes that slander the True Law are beyond the bounds of repentance. What part of what I have written makes you call it a red leaf?"

The monk bowed his head and answered: "Recently the various students from far and near who live at the temple have embraced a heroic resolution. They blithely sit, forgetting their own emaciated condition, and carry on their practice at the risk of their own bodies. Renting an old house or sneaking into an abandoned shrine, for fifteen years they have found sweet the bitter milk of the Master's poison, and are loath to disperse. But this year a tidal wave has swept over the fields and gardens and rice grains have not formed. The farmers, to support their wives and children, wish in secret that they might move to some other areas. I am deeply distressed and have lost all hope. There will not be a monk's staff left hanging at the Kokurin Monastery. The garden of Zen could not be any more desolate.

"Recently a monk said to me: 'Apart from those common, unstable men who seek fine food and clothing and long for noise and bustle, not one of the superior men who have been studying earnestly for so long a time, seeking understanding and a breakthrough to enlightenment, has left. Their perseverence and excellence is ten times what it was last month. In groups of five or ten they stay, some by the shore, some under the trees, without eating and without sleeping for five or ten days on end. All of them say: "This is like the association for the Buddhadharma held in olden days in evil years of famine."

"'They are as thin as men in mourning for their deceased mothers, as weak as persons afflicted with a dread disease. Their cold and hunger, the suffering that besets them, would cause spirits to shed tears, and demons to join their palms together in respect.

"'Today monasteries everywhere are equipped with lofty temple buildings and sumptuous quarters for the monks. The two wheels turn at the same time and the four offerings are piled up. What sort of mind is it then that does not pay attention to such things? Living in a place where hunger, cold, and poverty abound, all that enters their ears are the evil words and abuse of the Master; all that passes their mouths is chaff of millet and wheat, and there is not one thing that in their hearts they feel is good. Yet these monks are not here because they have no other place to go. They are all superior monks, fully qualified to be in monasteries, but each of them devotes himself assiduously to the search for his own enlightenment, and pays no attention to anything else.' When I hear things like this I am greatly impressed and feel that it is fortunate indeed that this is a time when many people will gain the Buddhadharma.

"You must proclaim the need to take up the forging irons of progress toward enlightenment and look for superior monks who have really studied and gained a true awakening. If you approach people with the secondary meaning and use methods with a different import, you will be doing people a great harm. They will be blocked by the others gates to enlightenment, and in the end you will not be able to produce even the least significant kind of person. Thirty years ago I suffered the painful polishing accorded by my Master, and after undergoing numerous hardships, attained understanding of the innate Buddha-nature, penetrated the True Face of the Lotus, gained the true understanding without the slightest doubt of the mysterious principles of the three thousand worlds in one instant of thought and the innermost meaning of the perfect unity of the three truths. My Master himself acknowledged that I had gained an understanding of the True Face of the Lotus, and I thought in private to myself that as far as I was concerned, everything in the world had been determined.

"When recently I listened to your lectures on the Pi-yen lu, however, it was just as if I were a farmer standing far away down the steps, listening to lectures being delivered by various gentlemen of high rank at the Secretariat. I was like a man with bad vision who strains his eyes to see the scenery of Hsiao-shui, like a deaf man who cocks his ears to hear the music emanating from Tung-t'ing Lake. With this, my strength drained away; the sweat of remorse poured from my armpits, and tears of pain filled by breast. It was as though all the painful practice I had been through had not done the slightest bit of good. In the beginning I thought that the powers I had attained were on the same level as yours. But now I realize that to hold doubts about you is like a sheep pointing at a fine steed and saying: 'This is my father,' or like a lame turtle indicating a heavenly dragon and saying: 'This is my Master.'

"I was depressed and irritated because I felt privately that you were making me the butt of deception. Just now I read what you had written about the True Face of the Lotus, and I was aroused to envy and so said: 'This is a yellow leaf for a crying child.' You can understand my reaction, I hope. The various monks in the temples all lament in the same way, saying that you point to the place to which they have attained by arduous labors, and call it 'the Zen of a corpse in a coffin.'"

I replied: "This is quite true. Ah! Keep going with your practice! Do you see that old pine tree towering above the hills and valleys? Its branches pierce the highest heaven; its roots reach through to the bowels of the earth. Above, the hanging moss reaches for a hundred feet; below, the fungus that grows only after the tree has lived a thousand years clings to the roots. Its strength is that of the flood-dragon that grasps the mists and seeks to rise to the heights of the sky. Below is a pine tree one inch high just putting forth a shoot of needles. One can pluck it out with the fingers, snap it off with the nails.

"If I point to these two trees and ask someone what they are, the answer will invariably be: "They are both pine trees. It all depends on the amount of time that they have been growing." But don't say: 'It's a matter of the passage of time.' If you guard the materials used for making a coffin and end up by living in a demon's home, even if you pile them up to the year X, of what possible use will they ever be?"

Once there were two children of Mr. Chang. The elder brother was named Chang Wu and the younger Chang Lu. One day they bundled up some provisions and set out on a long journey. While on the way they happened to find a bar of gold, and they danced for joy at the discovery. But later their ways parted and some thirty years passed in which each of the brothers did not know whether the other was dead or alive. Lu, wondering about his brother, sought him in all directions, and finally having discovered his borther's whereabouts, journeyed there from afar to pay him a visit. When Lu came finally to his brother's place, he was amazed at its opulence: the water wheels groaned as they turned and carts filled with grain came rumbling past. Oxen and horses filled the stables, flocks of geese crowded the ditches. The sound of bamboo flutes and pipes floated from the house and voices were raised in song. Elegant guests came in and out.

Lu, shaking with fear, was unable to cross the threshhold. Bowing to the ground with terror and trembling, he offered his name card. Two boys handsome in appearance and elegant in bearing came to greet him. Chang Lu followed them in, walking with extreme diffidence. The magnificence of the walls and the beauty of the buildings were such that K'ang I and Shih Nu would have felt at home in them. Chang Lu's spirits faltered and his legs trembled and he did not know where to sit down. After a short while Chang Wu, attended by his concubines and female servants, appeared from beneath an embroidered canopy. The resplendent costuming of the women who attended on his brother astounded Chang Lu; the embroidered damasks overwelmed his eyes. A golden incense burner poured forth the fragrance of a thousand flowers; jade ornaments gave off hundreds of delicate sounds. A crimson embroidered cap adorned Chang Wu's head; from his shoulders a purple gown hung. He seated himself on a luxurious green cushion and leaned his arm on a sandalwood table. He glared with the haughty eyes of a tiger; he held his shoulders arrogantly in the pose of a kite.

Chang Lu took one look and could not help but lower his eyes to the ground. His body seemed to shrink and his tears flowed without cease. We was quite unable to raise his head and look his brother straight in the face.

Deliberately Chang Wu began to speak: "My brother, why were you so long in coming? How is it that you appear in such distressed circumstances?"

Chang Lu, wiping away his tears, asked then timidly: "My brother, to what lord are you indebted? From whom have you received patronage that you are so great and wealthy now?"

Chang Wu answered: "I am not the minister to any man, nor have I received the largess of a patron. I am just someone who a long time ago found some money."

Chang Lu said: "How many boxes of gold did you find? Was it as much as can be piled into a large wagon or loaded onto a giant ship? Was it money that fell from heaven or a treasure buried beneath the earth? Who was the person who forgot about all this wealth?"

"Not at all. It was the money that thirty years ago you and I found together upon the highway," replied his brother.

Chang Lu responded: "How strange! With only one bar of gold you were able to attain all these riches?" Then suddenly Chang Lu became greatly troubled. "Are you perhaps a member of an evil gang, a partner in crime with the thieves Tao Chih and Chuang Ch'iao? If so, I'd better leave in a hurry so that I'll be able to escape the fate that is sure to fall on the nine families of relatives. If I stay here, I'll just be inviting my own death."

Chang Wu laughed heartily: "What happened to the money you picked up thirty years ago? Did you gamble it away? Squander it on wine and women?"

Chang Lu replied: "I see, I see. My disreputable appearance must seem very strange to you. Please ask the others to leave the room. I have something I want to say to you in private." Chang Wu glanced up and then asked all his women to leave. Chang Lu cautiously drew nearer: "Do I look like someone who loses his money gambling or concerns himself with the women of the gay quarters? I am not poor because I lost the money, but rather trying to protect it has worn me out. Didn't you tell me long ago: 'Guard the money well. Don't squander it recklessly'? I am not the one who would go against the instructions of his brother."

As soon as Chang Lu had found the money, he wrapped it in a tenfold cloth and guarded it with the utmost care, as though he were protecting the jewel of Pien Ho or the precious Night-illuminating Jewel. He carried it with him wherever he went. For thirty years he had not relaxed, and had remained sleepless, fearing that he was constantly under the threat of death from thieves and assassins. He dreaded it if people inquired of his health, turned away from all his friends, and avoided association with anyone. He became a man of abject poverty, wearing on his shoulders a disreputable gown, patched in a hundred places, and on his head a tattered cap. People paid him absolutely no attention, never giving him a second thought, and this, in turn, he found a blessing. Fearing that he might exhaust his money, he took no wife, remaining always single. He hid himself in places where he need have nothing to do with other men, seeking out abandoned houses and dilapidated mausoleums to sleep in. He never stayed at an inn and was content with the most miserable of food. He begged beside the gates of people's houses, and if he was forced to stand for an appreciable length of time, he might on occassion sing for his food.

Then saying: "The gold is right here," he looked about several times to make sure that no one else was there to see him, and then he loosened his filthy, torn gown and fishing about in the folds finally drew out a packet wrapped around ten times in cloth. He undid it, and looking all around again, he took out the gold and showed it to his brother. "Where is the money that you picked up?" he asked. "Bring it out and let's see it for old time's sake."

Chang Wu laughingly replied: "Not long after you and I parted some thirty years ago I lost the gold."

Chang Lu paled and stared intently at his brother's face. Reflecting pensively he remarked: "You lost the money while I guarded it. Yet, though you lost it, you have become wealthy, and I who guarded mine am miserably poor." He opened his eyes wide and struck his forehead and gnashed his teeth and gnawed on his lips and could not help feeling deeply depressed. After a while he said: "If it is bad to guard something and starve from poverty and good to discard something and revel in riches, then, even though I am late about it, shouldn't I also throw the gold away? Please tell me how to discard it."

Chang Wu laughed uproariously and said: "The gold that you picked up was worth less than a yellow leaf. Not only did it fail to benefit you, but on the contrary, it impoverished you and did harm to your heart and entrails. Had you wrapped up a red leaf, it would have weighed nothing as you went on your rounds, nor would you have been afflicted by poverty; instead you might have spent your time in a simple cottage, caring for a wife and children, and might have slept comfortably, with your head high on a pillow. What you guarded was the road that led away from these things; what I threw away was the road that led to them.

"After I left you those thirty years ago, I went to Yang-chou. To me my gold was lighter than a yellow leaf, and I bought with it a great amount of salt. As soon as I sold the salt, with the profit I bought silk floss. As soon as I sold the silk floss, with the profit I bought hemp. As soon as I sold the hemp, with the profit I bought grain, fruit, fish, and meat. I sent people throughout the country to gather the treasures of mountain and sea, the beauties of land and water. Bringing all these things together, I opened several large stores with some three hundred employees. People stormed my doors with money in their hands and there was no variety of food that I did not sell. My possessions and wealth became enormous; T'ao Chu-kung's riches were small by comparison, I Tun's possessions would amount to nothing beside mine. My storehouses and granaries stand eave-to-eave in rows. I possess fifteen thousand acres of fertile land. I have purchased several score of mountains clothed with cypress and pine and groves of catalpa and cedar, and have set myself up in the establishment. This is the road I trod by casting away the gold, that I regarded as lightly as one does a red leaf."

Chang Lu stood up, bowed, and said: "Blessings on you, my brother. I hope that you continue in the best of health. Your casting away, while only seeming like casting away, actually turned out to be devoting your efforts to guarding. My guarding, which only seemed to be guarding, was actually devoting my efforts to throwing away. Guarding and throwing away bring different results indeed. One knows for a certainty that when it comes into the hands of a wise man, a yellow leaf is true gold; when it falls into the hands of a stupid person, true gold is only a yellow leaf. Oh, how I regret the thirty years of pain I have caused myself, the energies I have exhausted without a particle of gain!" His voice was choked with painful sobs.

Studying Zen under a teacher is just like this story. What you obtain at first is the nature with which man is innately endowed. It is the true face of the unique One Vehicle of the Lotus. What I have obtained is this very same nature, innate from the outset, this one and only true face of the One Vehicle of the Lotus. This is called seeing into one's own nature. This nature does not change in the slightest degree from the time one first starts in the Way until complete intuitive wisdom is perfected. It is like the metal refined by the Great Metal-maker. Therefore it has been said: "At the time that one first conceives the desire to study Buddhism, enlightenment has already been attained." In the teaching schools this is the first of the ten stages. But even more so, it is also the very last barrier. Who can tell how far in the distance the garden of the Patriarchs lies?

At times one hears people, from the vantage of a one-sided view, say: "The place that I stand facing now is the mysterious, unproduced pre-beginning where the Buddha and the Patriarchs have yet to arise. Here there is absolutely no birth, no death, no Nirvana, no passions, no enlightenment. All the scriptures are but paper fit only to wipe off excrement, the bodhisattvas and the arhats are but corrupted corpses. Studying Zen under a teacher is an empty delusion. The koans are but a film that clouds the eye. Here there is nothing; there there is nothing. I do not seek the Buddhas. I do not seek the Patriarchs. In starvation and sleeplessness what is there lacking?"

Even the Buddhas and the Patriarchs cannot cure an understanding such as this. Every day these people seek a place of peace and quiet; today they end up like dead dogs and tomorrow it will be the same thing. Even if they continue in this way for endless kalpas, they will still be nothing more than dead dogs. Of what possible use are such people! The Tathagata has compared them to scabrous foxes. Anguilimalya has scorned them as having the intelligence of earthworms. Vimalakirti has placed them in the category of those who would scorch buds and cause seeds to rot. Ch'ang-sha has called them people who cannot move from the top of a hundred-foot pole. Lin-chi has described them as being in a deep, dismal, black pit. These are people who do not separate from the so-called device and rank, and thus fall into the sea of poison. Sticking to a one-sided view, and spending their time time polishing and perfecting purity, they end up having spent their whole lives in error. They are like that Chang Lu who, embracing his bar of gold, spent his whole life exhausted and persecuted. Tz'u-ming, Huang-lung, Chen-ching, Hui-t'ang, Hsi-keng, and Ta-hui devoted all their energies to eradicating this attitude, but they could not save people like these.

When I was seven or eight years old my mother took me to a temple for the first time and we listened to a sermon on the hells as described in the Mo-ho chih-kuan. The priest dwelt eloquently on the torments of the Hells of Wailing, Searing Heat, Incessant Suffering, and the Red Lotus. So vivid was the priest's description that it sent shivers down the spines of both monks and laymen and made their hair stand on end in terror. Returning home, I took stock of the deeds of my short life and felt that there was but little hope for me. I did not know which way to turn and I was gooseflesh all over. In secret I took up the chapter on Kannon from the Lotus Sutra and the dharani on Great Compassion and recited them day and night.

One day when I was taking a bath with my mother, she asked that the water be made hotter and had the maid add wood to the fire. Gradually my skin began to prickle with the heat and the iron bath-cauldron began to rumble. Suddenly I recalled the descriptions of the hells that I had heard and I let out a cry of terror that resounded through the neighborhood.