白隠慧鶴 Hakuin

Ekaku (1686-1769)

« back

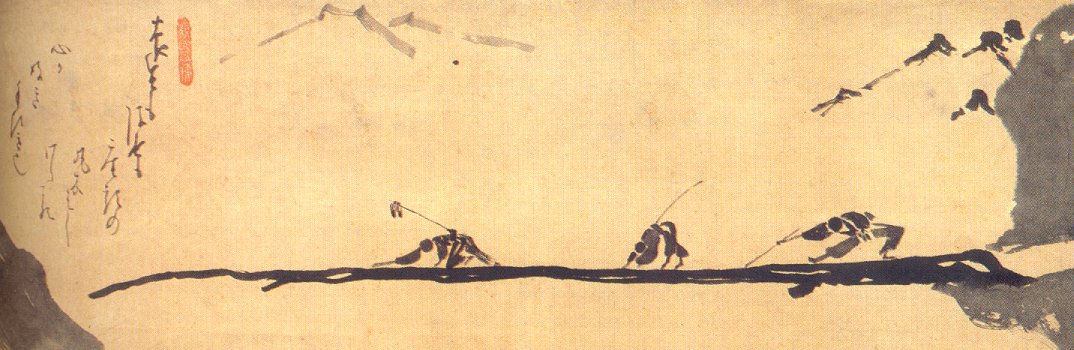

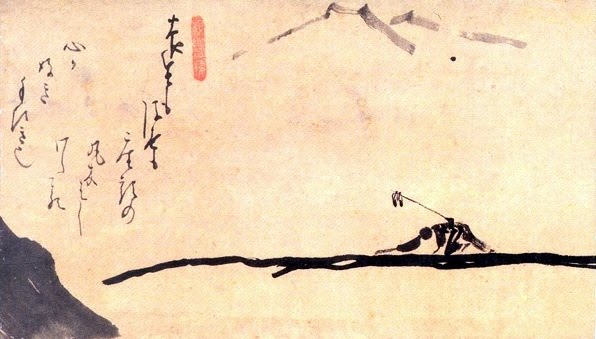

Blind

Men Crossing a Bridge

Ink on paper, (19.2 x 67 centimeters), Chikusei Collection

![]() Vakok a hídon

Vakok a hídon

Babits Mihály verse Hakuin festményére

Terebess Gábor haikuja

Hakuin Ekaku (1685–1768) has often been called the most important Zen master of the past five hundred years. Among other things, he invented the koan “What is the Sound of One Hand?” Hakuin was also the most significant Zen artist of this period, creating several thousand works of painting and calligraphy. While traditional Zen subjects had generally been limited to Zen figures, landscapes, and occasionally symbolic plants such as orchids or bamboo, Hakuin exploded the range of subject matter to include a wide range of new themes. One of these is “Blind Men Crossing the Bridge”—trying to cross a dangerous log bridge can be seen as a visual representation of crossing over to enlightenment. This is a familiar metaphor in Buddhism, such as the chant at the end of the Heart Sutra: Gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi svaha (Gone, gone, gone beyond, gone to the other shore, all hail).

In his commentary on the Heart Sutra, Hakuin wrote, “The Chinese means ‘reach the other shore.’ But where is that? Take one more step! Is there a soul on earth who belongs on ‘this shore’? How sad to stand mistaken on a wavelashed quay!”

Hakuin painted the theme of blind men crossing a log bridge at least eight times, with the landscape elements reduced to a minimum. Curiously, one painting has nine blind men, one has five, three have three, two have two, and one has only the sketch outline of a single figure; this once again demonstrates how Hakuin continued to change and experiment in his art.

In this depiction of three blind men, the shores are simply depicted on the right and left edges of the painting, mountains float in space above, and on the right a few strokes of ink suggest pine trees pointing toward the figures on the bridge. The blind men are suggested only by very simple short dashes and dots of the brush, yet they seem fully alive.

The blind men start from the right and seem to be struggling harder and harder to cross the bridge. The first holds his sandals in his hands as he reaches out with his staff, the second puts his staff in his belt and reaches out with his fingers, and the third crawls forward with his sandals tethered at the end of his staff for balance. To make the situation more difficult, the bridge does not quite reach the other shore. Will they all make it across?

The subject of blind men was not new to Buddhism, but previously had often been presented in a more negative way. For example, here is a “capping phrase” (which could be applied to a koan) from traditional Zen:

One blind man tugs many blind men;

Pulling each other into the fire-pit.

In the Mumonkan collection, koan #46 has a verse by Wu-men (Jp: Mumon) that is more complex in its analogies.

The eye in the forehead is darkened,

The pointer on the scale misleads us;

Throwing away body and spirit,

The blind are leading the blind.

Although the first two lines seem negative, is “throwing away body and spirit” a possible Zen activity? If so, the blind leading the blind may have some positive connotations. In this depiction of blind men on a bridge, Hakuin added his own doka (Buddhist waka) poem in the upper left, using the traditional Japanese five-line form of 5-7-5-7-7 syllables:

yôjô mo

ukiyo mo zatô no

maruki bashi

wataru kokoro wa

yoki tebiki nari

Both the health of our bodies

and the fleeting world outside us

are like the blind men’s

round log bridge—a mind/heart

that can cross over is the best guide

The idea of a perilous bridge maintained its importance to Hakuin through the years. In his sermon “Awakening from Day-Dreaming,” he writes, “The bridge which takes us across our floating world is dangerous for the feet which walk over it.” Yet words alone cannot be as powerful as when combined with a painting; in Hakuin’s portrayals of blind men trying to cross a log bridge, he created images that can resonate with us all.

Stephen Addiss

Babits Mihály: Vakok a hídon

Nyugat, 1913. 5. számA Csöndnek

folyóján

pár deszka-

darab.

Mi zajból van e csönd? Zubog zúg a hab.Támolygva

tolongnak

a hídon

vakok

kis görnyedt, japános, naiv alakok.A lelkük

a testbõl

ki sem lát

soha.

A deszkát belepte iszamlós moha.

Se korlát

se hídrács

legörbülve

mind

Padlóig

derékban

letörpülve

mind

lenn útat magának kezével tapint

üres szemgolyójuk

szanaszét tekint

faruk meg feltolva

a zord égnek int.

Mind bukdos

botorkál

gyámoltalanul

És olykor

kezével

a semmibe nyul

És olykor

tört lécen

hintázni tanul.És néha

fülükbe

jön egy

csobbanás:

És néha

szemükbe

csap egy

loccsanás:

a Csöndbe taszítja le társát a társ.S mi zajból

van e Csönd?

Zubognak a

habok.

A Csöndnek kis hídján tolongnak a

vakok.Egy bús fűz hullatja ágak záporát.

Széles hold kacagja, mint gúnyos barát

szegény kis támolygó vakoknak farát.

Babits Mihály: Vakok a hídon - Elmondja: Orbán György

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=grNn2PPoa2M

Híd vezet világtalant

Terebess Gábor haikuja

egy szál rönkhídon

vakok kelnek át – látni

már a túlpartot