ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

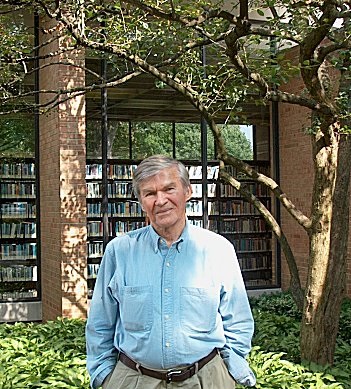

Lucien Stryk (1924-2013)

Tartalom |

Contents |

大智祖継 Daichi Sokei (1290–1366): Waka és fohász 寂室元光 Jakushitsu Genkō (1290-1367) verse |

PDF: From ‘The Rocks of Sesshu’ to Triumph of the Sparrow: The Japanese Sources of Lucien Stryk’s Early Poems ZEN POEMS pp. 3-19. ZEN POEMS OF CHINA & JAPAN: The Crane's Bill PDF: The Penguin book of Zen poetry (1981) PDF: Encounter With Zen: Writings on Poetry and Zen PDF: Collected Poems, 1953-1983 PDF: And Still Birds Sing: new & collected poems Lucien Stryk's Preface PDF: After Images [後象]: Zen poems of Takahashi Shinkichi PDF: Triumph of the Sparrow Zen Poetry: Let the Spring Breeze Enter PDF: Where We Are: Selected Poems And Zen Translations PDF: The Awakened Self: Encounters with Zen Afterword Jakushitsu (1290-1367) Daichi's Poem and Prayer Interview with Master 安田天山 Yasuda Tenzan PDF: On Love and Barley: Haiku of Basho PDF: The Dumpling Field: Haiku of Issa |

Lucien Stryk / photo © Barry Stark

http://www.niutoday.info/2013/01/29/niu-mourns-death-of-famed-poet-lucien-stryk/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucien_Stryk

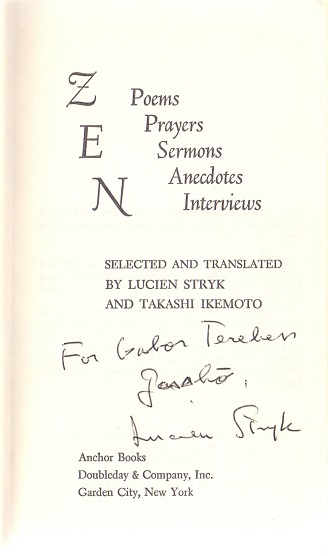

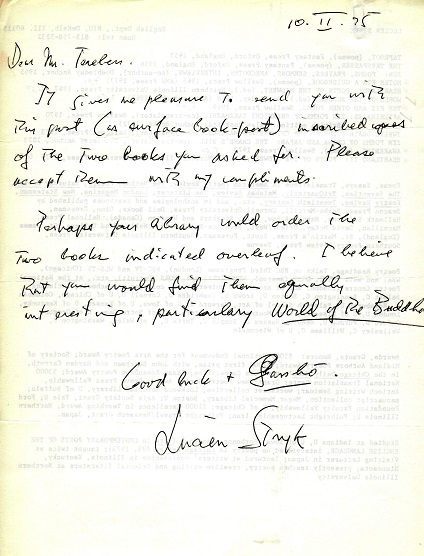

ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Ikemoto Takashi [池本喬, 1906-1980]

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, pp. 3-19, 39-98, 99-133.

Title page with handwritten dedication for Gabor Terebess

ZEN POEMS

Chapter XXIV in: World of the Buddha: An Introduction to the Buddhist Literature

edited with introduction and commentaries by Lucien Stryk

Garden City, N.Y. : Doubleday, 1968.

in: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Ikemoto Takashi [池本喬, 1906-1980]

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, pp. 3-19.

What follows is a selection of Zen Buddhist poems written by Japanese masters from the thirteenth century to the present. The poems are so suggestive in themselves that explication is rarely necessary; furthermore, the poets rarely theorized about the poems they would write from time to time, and for good reason: to them poetry was not, as so often in the West, an art to be cultivated but a means by which an attempt at the nearly inexpressible could be made. Though certain of the poems are called satori (enlightenment) and others death poems, in a sense all Zen poetry deals with momentous experience. There are, in other words, no finger exercises, and though some of the poems may seem comparatively light, there is not one that is not totally in earnest, fully inspired. Indeed when you consider the Zennist’s traditional goal, the all-or-nothing quality of his striving after illumination, this is scarcely to be wondered at. The Zen state of mind has been described as “one in which the individual identifies with an object without any sense of restraint,” as in this poem by Bunan:

The moon’s the same old moon,

The flowers exactly as they were,

Yet I’ve become the thingness

Of all the things I see!

Zen poetry is highly symbolic, and the moon here is a common symbol. It should be remembered, in relation to the use of such symbols, that Zen is a Mahayana school, and that the Zennist searches, always within himself, for the indivisible moon reflected not only on the sea but on each dew drop. To discover this, the Dharmakaya, in all things is for the Zennist to discover his own Buddha-nature. Perhaps most Zen poems, whether designated as such or not, are satori poems, which are composed immediately after an awakening and are presented to a master for approval. Daito’s poem is typical:

At last I’ve broken Unmon’s barrier!

There’s exit everywhere-east, west; north, south.

In at morning, out at evening; neither host nor guest.

My every step stirs up a little breeze.

And here is a satori poem by Eichu:

My eyes eavesdrop on their lashes!

I’m finished with the ordinary!

What use bas balter, bridle

To one who’s shaken off contrivance?

Traditionally death poems are written or dictated by Zennists right before death. The author looks back on his life and, in a few highly compressed lines, expresses his state of mind at the inevitable hour. The following are among the best known:

Fumon

Magnificent! Magnificent!

No-one knows the final word.

The ocean bed’s aflame,

Out of the void leap wooden Iambs.

Kukoku

Riding backwards this wooden horse,

I’m about to gallop through the void.

Would you seek to trace me?

Ha! Try catching the tempest in a net.

Zekkai

The void has collapsed upon the earth,

Stars, burning, shoot across Iron Mountain.

Turning a somersault, I brush past.

The void, mentioned in all three of these death poems, is the great Penetralium of Zen. The mind, it is thought, is a void in which objects are stripped of their objectivity and reduced to their essence. In the death poem which follows, by Bokuo, there is an important Zen symbol, the ox, which here serves as an object of discipline:

For seventy-two years

I’ve kept the ox well under.

Today, the plum in bloom again,

I let him wander in the snow.

Bokuo, in his calm acceptance of death, proves himself a true Zen-man. Though satori and death figure heavily in Zen poetry, most of the poems deal with nature and man’s place in it. Simply put, the Buddha-nature is by no means peculiar to man. It is discoverable in all that exists, animate or inanimate. Perhaps in this poem by Ryokan the Zen spirit is perfectly caught:

Without a jot of ambition left

I let my nature flow where it will.

There are ten days of rice in my bag

And, by the hearth, a bundle of firewood.

Who prattles of illusion or nirvana?

Forgetting the equal dusts of name and fortune,

Listening to the night rain on the roof of my hut,

I sit at ease, both legs stretched out.

DOGEN (1200-1253, Soto)

The Western Patriarch’s doctrine is transplanted!

I fish by moonlight, till on cloudy days.

Clean, clean! Not a worldly mote falls with the snow

As, cross-legged in this mountain hut, I sit the evening through.

DOGEN, WAKA

Coming, going, the waterfowl

Leaves not a trace,

Nor does it need a guide.A waka on “The mind must operate without abiding anywhere” (from the Diamond Sutra).

DOGEN

This slowly drifting cloud is pitiful;

What dreamwalkers men become.

Awakened, I hear the one true thing—

Black rain on the roof of Fukakusa Temple.

MUSO (1275-1351, Rinzai)

Many times the mountains have turned from green to yellow—

So much for the capricious earth!

Dust in your eyes, the triple world is narrow;

Nothing on the mind, your chair is wide enough.

MUSO, SATORI POEM

Vainly I dug for a perfect sky,

Piling a barrier all around.

Then one black night, lifting a heavy

Tile, I crushed the skeletal void!

DAITO (1282-1337, Rinzai), DEATH POEM

To slice through Buddhas, Patriarchs

I grip my polished sword.

One glance at my mastery,

The void bites its tusks!

GETSUDO (1285-1361, Rinzai), SATORI POEM

I moved across the Dharma-nature,

The earth was buoyant, marvelous.

That very night, whipping its iron horse,

The void galloped into Cloud Street.

DAICHI (1290-1366, Soto)

Thoughts arise endlessly,

There’s a span to every life.

One hundred years, thirty-six thousand days:

The spring through, the butterfly dreams.

JAKUSHITSU (1290-1367, Rinzai)

Refreshing, the wind against the waterfall

As the moon hangs, a lantern, on the peak

And the bamboo window glows. In old age mountains

Are more beautiful than ever. My resolve:

That these bones be purified by rocks.

CHIKUSEN (1292-1348, Soto)

He’s part of all, yet all’s transcended;

Solely for convenience he’s known as master.

Who dares say he’s found him?

In this rackety town I train disciples.

BETSUGEN (1294-1364, Rinzai)

All night long I think of life’s labyrinth—

Impossible to visit the tenants of Hades.

The authoritarian attempt to palm a horse off as deer

Was laughable. As was the thrust at

The charmed life of the dragon. Contemptible!

It’s in the dark that eyes probe earth and heaven,

In dream that the tormented seek present, past.

Enough! The mountain moon fills the window.

The lonely fall through, the garden rang with cricket song.

The authoritarian attempt … refers to the Chinese classic Shiki, in which Choko presents a horse to the Emperor, claiming it is a deer. The Emperor’s courtiers, obsequious to Choko, do not dispute his claim.

As was the thrust at … refers to Soshi (Chuantzu): Shu spent three years acquiring the skill to kill dragons, but of course this did him no good.

JUO (1296-1380, Rinzai)

Beyond the snatch of time, my daily life.

I scorn the State, unhitch the universe.

Denying cause and effect, like the noon sky,

My up-down career: Buddhas nor Patriarchs can convey it.

SHUTAKU (1308-1388, Rinzai)

For all these years, my certain Zen:

Neither I nor the world exist.

The sutras neat within the box,

My cane hooked upon the wall,

I lie at peace in moonlight

Or, hearing water plashing on the rock,

Sit up: none can purchase pleasure such as this:

Spangled across the step-moss, a million coins!*

Mind set free in the Dharma-realm,

I sit at the moon-filled window

Watching the mountains with my ears,

Hearing the stream with open eyes.

Each molecule preaches perfect law,

Each moment chants true sutra:

The most fleeting thought is timeless,

A single hair’s enough to stir the sea.

RYUSHU (1308-1388, Rinzai)

Why bother with the world?

Let others go gray, bustling east, west.

In this mountain temple, lying half-in,

Half-out, I’m removed from joy and sorrow.

SHUNOKU (1311-1388, Rinzai)

After the spring song, “Vast emptiness, no holiness,”

Comes the song of snow-wind along the Yangtze River.

Late at night I too play the noteless flute of Shorin,

Piercing the mountains with its sound, the river.

Vast emptiness, no holiness. Bodhidharma’s reply to the question put by Butei, Emperor of Ryo, “What is the primary principle of Buddhism?” (Cf. the first koan of Hekiganroku.)

Shorin. Name of the temple where Bodhidharma, on finding that Butei was not a true Zennist, sat in Zen for nine years. To reach the temple, he had to cross the Yangtze River.

TESSHU (14th century, Rinzai)

How heal the phantom body of its phantom ill,

Which started in the womb?

Unless you pluck a medicine from the Bodhi-tree,

The sense of karma will destroy you.

TSUGEN (1322-1391, Soto)

Not a mote in the light above,

Soul itself cannot offer such a view.

Though dawn’s not come, the cock is calling:

The phoenix, flower in beak, welcomes spring.

GUCHU (1323-1409, Rinzai)

Men without rank, excrement spatulas,

Come together, perfuming earth and heaven.

How well they get along in temple calm

As, minds empty, they reach for light.Excrement spatulas. To a monk’s question, “What is the Buddha?”, Unmon replied, “An excrement spatula.” (Cf. the twenty-first koan of Mumonkan.)

MUMON (1323-1390, Rinzai)

Life: a cloud crossing the peak.

Death: the moon sailing.

Oh just once admit the truth

Of noumenon, phenomenon,

And you’re a donkey-tying pole!A donkey-tying pole. Often used in Zen writing, meaning a trifle.

GIDO (1325-1388, Rinzai): INSCRIPTION OVER HIS DOOR

He who holds that nothingness

Is formless, flowers are visions,

Let him enter boldly!

REIZAN (-1411, Rinzai)

The myriad differences resolved by sitting, all doors opened.

In this still place I follow my nature, be what it may.

From the one hundred flowers I wander freely,

The soaring cliff—my hall of meditation

(With the moon emerged, my mind is motionless).

Sitting on this frosty seat, no further dream of fame.

The forest, the mountain follow their ancient ways,

And through the long spring day, not even the shadow of a bird.

MYOYU (1333-1393, Soto), SATORI POEM

Defying the power of speech, the Law Commission on Mount Vulture!

Kasyapa’s smile told the beyond-telling.

What’s there to reveal in that perfect all-suchness?

Look up! the moon-mind glows unsmirched.

HAKUGAI (1343-1414, Rinzai), SATORI POEM

Last year in a lovely temple in Hirosawa,

This year among the rocks of Nikko,

All’s the same to me:

Clapping hands, the peaks roar at the blue!

NANEI (1363-1438, Rinzai)

Splitting the void in half,

Making smithereens of earth,

I watch inching toward

The river, the cloud-drawn moon.

KODO (1370-1433, Rinzai)

Serving the Shogun in the capital,

Stained by worldly dust, I found no peace.

Now, straw hat pulled down, I follow the river:

How fresh the sight of gulls across the sand!

IKKYU (1394-1481, Rinzai)

After ten years in the red-light district,

How solitary a spell in the mountains.

I can see clouds a thousand miles away,

Hear ancient music in the pines.

VOID IN FORM

When, just as they are,

White dewdrops gather

On scarlet maple leaves,

Regard the scarlet beads!A waka on “Void in Form” (from The Heart Sutra).

FORM IN VOID

The tree is stripped,

All color, fragrance gone,

Yet already on the bough,

Uncaring spring!A waka on “Form in Void” (from The Heart Sutra).

GENKO (-1505, Soto)

Unaware of illusion or enlightenment,

From this stone I watch the mountains, hear the stream.

A three-day rain has cleansed the earth,

A roar of thunder split the sky.

Ever serene are linked phenomena,

And though the mind’s alert, it’s but an ash heap.

Chilly, bleak as the dusk I move through,

I return, a basket brimmed with peaches on my arm.

SAISHO (-1506, Rinzai): ON JOSHU’S NOTHINGNESS

Earth, mountains, rivers—hidden in this nothingness.

In this nothingness-earth, mountains, rivers revealed.

Spring flowers, winter snows:

There’s no being nor non-being, nor denial itself.

YUISHUN (-1544, Soto), SATORI POEM

Why, it’s but the motion of eyes and brows!

And here I’ve been seeking it far and wide.

Awakened at last, I find the moon

Above the pines, the river surging high.

TAKUAN (1573-1645, Rinzai), WAKA

Though night after night

The moon is stream-reflected,

Try to find where it has touched,

Point even to a shadow.A waka on “The willow is green, the rose is red.”

GUDO (1579-1661, Rinzai)

It’s not nature that upholds utility.

Look! even the rootless tree is swelled

With bloom, not red nor white, but lovely all the same.

How many can boast so fine a springtide?

KARASUMARU-MITSUHIRO (1579-1638, Rinzai)

Beware of gnawing the ideogram of nothingness:

Your teeth will crack. Swallow it whole, and you’ve a treasure

Beyond the hope of Buddha and the Mind. The east breeze

Fondles the horse’s ears: how sweet the smell of plum.

UNGO (1580-1659, Rinzai)

Whirled by the three passions, one’s eyes go blind;

Closed to the world of things, they see again.

In this way I live: straw-hatted, staff in hand,

I move illimitably, through earth, through heaven.

DAIGU (1584-1669, Rinzai)

Here none think of wealth or fame,

All talk of right and wrong is quelled:

In autumn I rake the leaf-banked stream,

In spring attend the nightingale.*

Who dares approach the lion’s

Mountain cave? Cold, robust,

A Zen-man through and through,

I let the spring breeze enter at the gate.

MANAN (1591-1654, Soto)

Unfettered at last, a traveling monk,

I pass the old Zen barrier.

Mine is a traceless stream-and-cloud life.

Of those mountains, which shall be my home?

FUGAI (17th century, Soto)

Only the Zen-man knows tranquillity:

The world-consuming flame can’t reach this valley.

Under a breezy limb, the windows of

The flesh shut firm, I dream, wake, dream.

BUNAN (1602-1676, Rinzai), WAKA

When you’re both alive and dead,

Thoroughly dead to yourself,

How superb

The smallest pleasure!

MANZAN (1635-1714, Rinzai)

One minute of sitting, one inch of Buddha.

Like lightning all thoughts come and pass.

Just once look into your mind-depths:

Nothing else has ever been.

TOKUO (1649-1709, Rinzai)

The town’s aflame with summer heat,

But Mount Koma is steeped in snow.

Such is a Zen-man’s daily life—

The lotus survives all earthly fire.

HAKUIN (1685-1768, Rinzai)

Past, present, future: unattainable,

Yet clear as the moteless sky.

Late at night the stool’s cold as iron,

But the moonlit window smells of plum.*

Priceless is one’s incantation,

Turning a red-hot iron ball to butter oil.

Heaven? Purgatory? Hell?

Snowflakes fallen on the hearth fire.*

How lacking in permanence the minds of the sentient—

They are the consummate nirvana of all Buddhas.

A wooden hen, egg in mouth, straddles the coffin.

An earthenware horse breaks like wind for satori-land.*

You no sooner attain the great void

Than body and mind are lost together.

Heaven and Hell—a straw.

The Buddha-realm, Pandemonium—shambles.

Listen a nightingale strains her voice, serenading the snow.

Look, a tortoise wearing a sword climbs the lampstand.

Should you desire the great tranquillity,

Prepare to sweat white beads.

SENGAI (1750-1837, Rinzai): ON BASHO’S “FROG”

Under the cloudy cliff, near the temple door,

Between dusky spring plants on the pond,

A frog jumps in the water, plop!

Startled, the poet drops his brush.Basho’s haiku on the frog is one of the most famous ever written. Here is Harold G. Henderson’s translation (An Introduction to Haiku, Doubleday Anchor):

Old pond—

and a frog-jump-in

water-sound.

KOSEN (1808-1893, Rinzai), SATORI POEM

A blind horse trotting up an icy ledge—

Such is the poet. Once disburdened

Of those frog-in-the-well illusions,

The sutra-store’s a lamp against the sun.

TANZAN (1819-1892, Soto)

Madness, the way they gallop off to foreign shores!

Turning to the One Mind, I find my Buddhahood,

Above self and others, beyond coming and going.

This will remain when all else is gone.

KANDO (1825-1904, Rinzai)

It’s as if our heads were on fire, the way

We apply ourselves to perfection of That.

The future but a twinkle, beat yourself,

Persist: the greatest effort’s not enough.

Cf..

World of the Buddha: an introduction to Buddhist literature

by Stryk, Lucien

Grove Press, New York, 1982. pp. 343-362.PDF: Chapter XXIV: Zen Poems

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Takashi IkemotoDogen (1200-1253, Soto)

Muso (1275-1351, Rinzai)

Daito (1282-1337, Rinzai),

Getsudo (1285-1361, Rinzai),

Daichi (1290-1366, Soto)

Jakushitsu (1290-1367, Rinzai)

Chikusen (1292-1348, Soto)

Betsugen (1294-1364, Rinzaf)

Juo (1296-1380, Rinzai)

Shutaku (1308-1388, Rinzai)

Ryushu (1308-1388, Rinzai)

Shunoku (1311-1388, Rinzai)

Tesshu (14th century, Rinzai)

Tsugen (1322-1391, Soto)

Guchu (1323-1409, Rinzai)

Mumon (1323-1390, Rinzai)

Gido (1925-1388, Rinzai):

Reizan (?-1411, Rinzai)

Myoyu (1333-1393, Soto),

Hakugai (1343-1414, Rinzai)

Nanei (1363-1438, Rinzai)

Kodo (1370-1433, Rinzai)

Ikkyu (1394-1481, Rinzai)

Genko (?-1505, Soto)

Saisho (?-1506, Rinzai)

Yuishun (?-1544, Soto)

Takuan (1573-1645, Rinzai),

Gudo (1579-1661, Rinzai)

Karasumaru-Mitsuhiro (1579-1638, Rinzai)

Ungo (1580-1659, Rinzai)

Daigu (1584-1669, Rinzai)

Manan (1591-1654, Soto)

Fugai (17th century, Soto)

Bunan (1602-1676, Rinzai)

Manzan (1635-1714, Rinzai)

Tokuo (1649-1709, Rinzai)

Hakuin (1685-1768, Rinzai)

Sengai (1750-1837, Rinzai)

Kosen (1808-1893, Rinzai)

Tanzan (1819-1892, Soto)

Kando (1825-1904, Rinzai)

Shinkichi Takahashi (1901-1987, Rinzai)

ZEN SERMONS

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Takashi Ikemoto [池本喬 1906-1980]

In: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963. pp. 39-98.

Chapter XXV in: World of the Buddha: An Introduction to the Buddhist Literature

edited with introduction and commentaries by Lucien Stryk

Garden City, N.Y. : Doubleday, 1968.

Zen Buddhist sermons are unlike those of any other religion, whatever the sect of the master—Rinzai, which stresses sudden enlightenment, Soto, which maintains that gradually perfected meditation is the same as enlightenment, or Obaku, which has more in common with Rinzai, practicing zazen (formal meditation) and employing koan (problem for meditation), though the Nembutsu (invocation of the Buddha Amida) is also engaged in by this sect. The purpose of the Zen sermon is less to guide toward what is vaguely thought to be the ethical life than to point directly at the experience of enlightenment, for it is assumed by the masters that those listening to them are morally upright, and that what they desire is an awakening which will result in a new way of viewing themselves in the world. In spite of the similarity in the masters' aims, however, their sermons are as individual as they themselves are—Bankei-Eitaku's are a good example. The historical continuity of the sermon literature is possibly due to the fact that when compared with other Buddhist schools, Zen has been able to absorb shifts and upheavals, in politics and culture, which normally bring about changes in religion and philosophy. Most of the sermons which follow, while not expounding doctrine as such, are philosophical, as is almost always true of Mahayana literature, and it may surprise the reader to find ideas advanced which are very contemporary in feeling.

Dogen: On Life and Death

Muso: Dream Dialogue

Meiho: Zazen

Ryoho: On Emptiness

Shozan: Nio-Zen

Manzan: Letter to Zissan

Takusui: Sermon

Bankei-Eitaku: The Zen of Birthlessness

DOGEN (1200-1253, Soto)

ON LIFE AND DEATH

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Takashi Ikemoto [池本喬 1906-1980]

In: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, pp. 40-41.“Since there is Buddhahood in both life and death,” says Kassan, “neither exists.” Jozan says, “Since there is no Buddhahood in life or death, one is not led astray by either.” So go the sayings of the enlightened masters, and he who wishes to free himself of the life-and-death bondage must grasp their seemingly contradictory sense.

To seek Buddhahood outside of life and death is to ride north to reach Southern Etsu or face south to glimpse the North Star. Not only are you traveling the wrong way on the road to emancipation, you are increasing the links in your karma-chain. To find release you must begin to regard life and death as identical to nirvana, neither loathing the former nor coveting the latter.

It is fallacious to think that you simply move from birth to death. Birth, from the Buddhist point of view, is a temporary point between the preceding and the succeeding; hence it can be called birthlessness. The same holds for death and deathlessness. In life there is nothing more than life, in death nothing more than death: we are being born and are dying at every moment.

Now, to conduct: in life identify yourself with life, at death with death. Abstain from yielding and craving. Life and death constitute the very being of Buddha. Thus, should you renounce life and death, you will lose; and you can expect no more if you cling to either. You must neither loathe, then, nor covet, neither think nor speak of these things. Forgetting body and mind, by placing them together in Buddha's hands and letting him lead you on, you will without design or effort gain freedom, attain Buddhahood.

There is an easy road to Buddhahood: avoid evil, do nothing about life-and-death, be merciful to all sentient things, respect superiors and sympathize with inferiors, have neither likes nor dislikes, and dismiss idle thoughts and worries. Only then will you become a Buddha.

MUSO (1275-1351. Rinzai)

DREAM DIALOGUE

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Takashi Ikemoto [池本喬 1906-1980]

In: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, pp. 51-55.A: When we see suffering we are moved to pity. Why is such sympathy rejected as mercy arising from attachment? Furthermore, if you look upon all sentient beings as nothing more than phantoms, how can you pity them?

B: Well, let's take beggars as an example. They can be divided into two classes: those who, born of beggar parents, have always been in a lowly position, and those who, born of noble parents, have later sunk in fortune. Naturally you are likely to pity the latter more. Now, the same applies to the Bodhisattva's mercy. All sentient beings are essentially Buddhas, without the marks of life and death, yet sooner or later they are deluded into thinking of life and death, they dream. The Mahayana Bodhisattva is therefore as much moved by the suffering of other sentient beings as by that of beggars of well-to-do parents. In this he is unlike the Hinayana Bodhisattva who, in considering that all beings are caught up in life and death, shows mercy arising from attachment.

A: Just as a drunkard is not aware of his state, so he who has yielded to Māra's [Devil] temptation is unaware of the fact. Thus he is unable to release himself. How can one resist Māra?

B: Fearing Māra, you are possessed by him. Nagarjuna writes, “If you have mind, you are caught in the Māra-net; without mind, you need not fear it.” An old master said, “There are none of Māra's hindrances outside the mind: no mind, no Māra.” Master Doju, you'll remember, conquered Māra by neither hearing nor seeing.

To cling to Buddhahood is to be in the Māra-realm; to forget Māra is to be in the Buddha-realm. A true Zennist is neither attached to the Buddha-realm nor fearful of Māra, then, and with fortitude, with no thought of gain, will remain in this state. Also, of course, you must make a vow before Buddha's image. The Perfect Enlightenment Sutra says, “Those living in a corrupt age must make this great vow of purification: May we attain Buddha's perfect enlightenment and, not ruled by non-Buddhists, Sravakas, and Pratyeka-Buddhas [those who gain enlightenment for their own salvation], but under good instruction, surmount obstacles one by one and enter the sanctified place of enlightenment.” Aided by this great vow, even a tyro will not be won over to devils and heretics throughout his successive lives. Supported by Buddhas and devas, all impediments removed, such a man will reach the never-receding state of tranquillity.

A: Even if he trains strictly, in accordance with the deep doctrines, it is possible that a beginner be misled. Indeed some masters discourage doctrinal studies while insisting on discipline pure and simple. How would you justify this standpoint?

B: Well, can one who has learned something about medicine cure himself of a serious illness? No. He must go to another for treatment and, without inquiring how it was compounded, take the medicine given him. The same is true of Zen discipline. If the seeker after the fundamental self, which is the aim of satori, tries to learn different doctrines and then, acting upon what he has learned, sets about training himself, he is probably doomed to ignorance. The doctrines are so numerous, life so short. At the end of his life he will see all the books and their learning as a heap of trash; dazed, he will be forced by karma along the cycle of rebirth. That is why Zen masters give you but a word or two, and these are not meant to provide a moral lesson but serve as a direct index of your fundamental self. Dull-witted students may not be able to understand the master's words at once, but if they continue to masticate them as a koan beyond the reach of intellect and sensibility, they will sooner or later rid themselves of the most persistent illusion. Suddenly it will be gone to the four winds.

A: Should one cast off worldly feelings-anger, joy, etc.— before applying himself to the examination of the Truth?

B: All humans, because they are able to profit by the Buddha's Law, are fortunate: it is the greatest rarity in the world. Nothing is less to be relied on than life, the inbreathing, the outbreathing. Knowing it for what it is, you must not yield to worldly feelings nor neglect your study of Zen. But suppose an emotion of that kind is felt Well, you must examine it minutely, just as it has risen. In this way your feelings can actually help you in your training. But the less-than-serious students must be taught differently: they must be helped in the task of alleviation, which does not mean, of course, that they should be told to eliminate all emotion before undertaking Zen discipline. The one important thing is the awakening and, once it has been attained, the ordinary man is a man of satori, however many emotions he retains.

Even when an emotion is felt, you must not give up probing. As you well know, the most religious are often forgetful of eating and sleeping, for even while doing these things they are scrutinizing themselves without obstacle. Though this is not exactly what the less religious are advised to do, they too should of course continue in self-examination. An ancient said, “While walking, examine the walking; while sitting, the sitting, etc.” The same holds true of joy and sorrow. An excellent admonition, that, and one likely to lead to an awakening.

A: There is disagreement about the importance of koan, some considering it all-important; others, paltry. What is your view of the matter?

B: It all depends on the master, the koan being but an expedient. There is no fixed rule about its use. A master once asked his pupil, “Are you in full accord with your koan?” When student and koan are as one, there is neither examined nor examiner. To one advanced as far as that, your question is meaningless. The less advanced, however, may properly do the koan exercise. The master alone, of course, can determine the outcome. Anyone without insight who simply reads the words of the old masters and then proceeds to teach his own hidebound opinions behaves in a most dangerous way.

An ancient censured just such an instructor as binding others to a Hinayanistic view of entity.

MEIHO (1277-1350, Soto)

ZAZEN

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Takashi Ikemoto [池本喬 1906-1980]

In: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, pp. 56-58.Zen-sitting is the way of perfect tranquillity: inwardly not a shadow of perception, outwardly not a shade of difference between phenomena. Identified with yourself, you no longer think, nor do you seek enlightenment of the mind or disburdenment of illusions. You are a flying bird with no mind to twitter, a mountain unconscious of the others rising around it.

Zen-sitting has nothing to do with the doctrine of “teaching, practice, and elucidation” or with the exercise of “commandments, contemplation, and wisdom.” You are like a fish with no particular design of remaining in the sea. Nor do you bother with sutras or ideas. To control and pacify the mind is the concern of lesser men: Sravakas, Pratyeka-Buddhas, and Hinayanists. Still less can you hold an idea of Buddha and Dharma. If you attempt to do so, if you train improperly, you are like one who, intending to voyage west, moves east. You must not stray.

Also you must guard yourself against the easy conceptions of good and evil: your sole concern should be to examine yourself continually, asking who is above either. You must remember too that the unsullied essence of life has nothing to do with whether one is priest or layman, man or woman. Your Buddha-nature, consummate as the full moon, is represented by your position as you sit in Zen. The exquisite Way of Buddhas is not the One or Two, being or non-being. What diversifies it is the limitations of its students, who can be divided into three classes-superior, average, inferior.

The superior student is unaware of the coming into the world of Buddhas or of the transmission of the non-transmit-table by them: he eats when hungry, sleeps when sleepy. Nor does he regard the world as himself. Neither is he attached to enlightenment or illusion. Taking things as they come, he sits in the proper manner, making no idle distinctions.

The average student discards all business and ignores the external, giving himself over to self-examination with every breath. He may probe into a koan, which he puts mentally on the tip of his nose, finding in this way that his “original face” (fundamental being) is beyond life and death, and that the Buddha-nature of all is not dependent on the discriminating intellect but is the unconscious consciousness, the incomprehensible understanding: in short, that it is clear and distinct for all ages and is alone apparent in its entirety throughout the universe.

The inferior student must disconnect himself from all that is external, thus liberating himself from the duality of good and evil. The mind, just as it is, is the origin of all Buddhas. In zazen his legs are crossed so that his Buddha-nature will not be led off by evil thoughts, his hands are linked so that they will not take up sutras or implements, his mouth is shut so that he refrains from preaching a word of dharma or uttering blasphemies, his eyes are half shut so that he does not distinguish between objects, his ears are closed to the world so that he will not hear talk of vice and virtue, his nose is as if dead so that he will not smell good or bad. Since his body has nothing on which to lean, he is indifferent to likes and dislikes. He negates neither being nor non-being. He sits like Buddha on the pedestal, and though distorted ideas may arise from him, they do so idly and are ephemeral, constituting no sin, like reflections in a mirror, leaving no trace.

The five, the eight, the two hundred and fifty commandments, the three thousand monastic regulations, the eight hundred duties of the Bodhisattva, the Buddha-nature and the Bodhisattvahood, and the Wheel of Dharma—all are comprised in Zen-sitting and emerge from it Of. all good works, zazen comes first, for the merit of only one step into it surpasses that of erecting a thousand temples. Even a moment of sitting will enable you to free yourself from life and death, and your Buddha-nature will appear of itself. Then all you do, perceive, think becomes part of the miraculous Tathata-suchness (true nature, thusness).

Let it be thus remembered that tyros and advanced students, learned and ignorant, all without exception should practice zazen.

RYOHO (1305-1384, Rinzai)

ON EMPTINESS

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Takashi Ikemoto [池本喬 1906-1980]

In: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, pp. 63-64.1. The Buddhas of all times and places preach the empty dharma with their empty bodies, so as to enable empty beings to realize equally empty Buddhahood. For this reason the Buddha declared, “Even if there is something excelling nirvana, it is an empty dream.”

If anyone in the reality of “suchness” can understand the dharma of dreamy emptiness and examine and practice it, he will through the dharma of reality conquer self and cherish mercy. In this way he will be able to invent a discipline and devices for what is called “The Way of Purity and Universal Emancipation.” If, however, he lingers in this view, he will not be able to attain the proper mental state of the Zen-man.

What is the one phrase (Ryoho lifted his staff before going on) that will lead you to the proper state? Well, say it! (Ryoho's staff came down with a thump.) Don't sleep, and you won't dream!

2. All things being empty, so is the mind. As the mind is empty, all is. My mind is not divisible: all is contained in my every thought, which appears as enlightenment to the wise, illusion to the stupid. Yet enlightenment and illusion are one. Do away with both, but don't remain “in between” either. In this way you will be emptiness itself, which, stainless and devoid of the interrelationship of things, transcends realization. In this way the true Zen priest commonly conducts himself.

SHOZAN (1579-1655, Rinzai)

NIO-ZEN

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Takashi Ikemoto [池本喬 1906-1980]

In: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, pp. 65-68.1. A man said to the master, “Of course, I never think of death.” To which the master responded, “That's all very well, but you'll not get very far in Zen, I'm afraid. As for myself, well, I train in Zen in detestation of death and in hope of deathlessness, and I am resolved to carry on in this way, from life to life, until I realize my aim. That you do not think of death shows that you are not a man of enlightenment, because you are incapable of knowing your master, whatever there is in you that uses the six sense organs.”

2. In studying Zen you should take Buddha images for models, but that of Tathagata (the Buddha in his corporeal manifestation) does not suit the beginner, because the Tathagata type of zazen is beyond him. Rather model yourself on images of Nio [Vajrapani: literally “Diamond Deity,” an indomitable guardian of Buddhism of ferocious mien] and Fudo, both of which are symbolic of discipline. This is apparent from the fact that Nios stand in temple gates, and Fudo is the first of the thirteen Buddhas. Without spirit and vigor you'll be passion's slave. Like these deities, have a dauntless mind.

Unfortunately Buddhism has declined, going from bad to worse, with the result that most are milksops, critically lacking in vigor. Only the valorous can train properly, the ignorant being mild and sanctimonious, mistaken in the belief that such is the way of Buddhist practice. Then there are the madmen who go about trumpeting their attainment of satori —a bagatelle. Myself, I'm a stranger to sanctimoniousness and satorishness, my sole aim being to conquer all with a vivacious mind. Sharing the vitality of Nio and Fudo, exterminate all of your evil karma and passions. (Here the master paused, eyes set, hands clenched, teeth gnashing.) Guard yourself closely, and nothing will be able to interfere. Only bravery will carry you through. We'll have no part of weaklings here! Be wide awake, and attain the vigor of living Zen.

3. The master once gave the following instructions to a samurai: “You had better practice zazen while busily occupied. The samurai's zazen must be the sort that will support him in the midst of battle, when he is threatened by guns and spears. After all, what use can the tranquilizing type of sitting be on the battlefield? You should foster the Nio spirit above all. All worldly arts are cultivated through Zen-sitting. The military arts especially cannot be practiced with a feeble spirit. (So saying, the master pretended to draw a sword.) Zazen must be virile, yet the warrior upholds it only in battle; no sooner does he sheathe his sword than he's off guard again. The Buddhist, on the other hand, always maintains vigor. Never is he a loser. The more he ripens in discipline, the more adept he becomes in everything, from the recitation of a text to tapping a hand drum in Noh. Perfect in all virtues, he can fit in anywhere.”

4. A priest asked the master, “Are not your works such as Fumotokusawake based on a notion of relative reality?”

“Of course,” said the master. “But you know the common man's mind is without exception one of relative reality. And how can you undergo Zen training without such a mind? Many masters nowadays lapse into notions of nothingness, leading their followers astray. They reside complacently in what they call original vacuity, which is the relative reality you speak of. Generally speaking, if you seek satori with your mind, you will leave behind the notion of being. However, if you cling with your no-mind to original vacuity, you cannot hope to succeed. Honen (1133-1212), founder of the Jodo [Pure Land] sect, for example, invoked Amitabha Buddha not with the no-mind but with the mind. And if you try to picture the Pure Land as really existing and repeat Amitabha's name, you will gain the virtue of no-mind. On the other hand, those who now pose as exponents of the primary void, and reject Zen discipline as something concerned with relative being, are merely accumulating evil karma.

5. A birdcatcher: “We have always been birdcatchers. If we give up, we'll starve. While following this trade, is it possible for me to attain Buddhahood?”

Master: “The mind falls into hell, not the body. Each time you kill a bird, grasp your mind and kill it also. In this way you can attain Buddhahood.”

6. The master cheered up an eighteen-year-old monk on the point of death by saying: “However long one lives, life goes on unchanging. You are lucky if you can discard the body, a thing of filth and suffering, even a single day earlier than others. In any case, you'll be free of life's bondage. I have lived to this old age without having seen one new thing. You may think Master Dogen a free man, but not so. He fell short of Lord Buddha's enlightenment, which is beyond the power of all of us. You know, many have failed in achieving their ends, not you alone. Even a long life can be flat, after all. The best thing is to cast the foul body aside as soon as possible. I promise to follow you soon.”

On hearing the master's words, the monk passed away in the proper frame of mind.

MANZAN (1635-1714, Soto)

LETTER TO ZISSAN

[Zissan: a monk's name, suggesting “real practice.”]

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Takashi Ikemoto [池本喬 1906-1980]

In: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, p. 69.Like training, satori must be true. If one holds that there is something to practice and realize, one is a follower of the false religion of entity based on affirmation. If, on the other hand, one asserts that there is nothing to practice or realize, one is still not above the four types of differentiation and the one hundred forms of negation: one is an adherent of the equally false religion of nothingness, founded on negation. And this is the shadowy product of the dichotomous intellect, holding no truth.

First of all, I ask you to look upon the world's riches as a dunghill, upon the most beautiful men and women as stinking corpses, upon the highest honors and reputation as an echo, upon the most malicious calumny as the cawing of a crow. Regard yourself as a fan in winter, the universe as a straw dog.

This accomplished, train wholeheartedly. Then, and then only, will you awaken. If you dare claim to have undergone real training and attained enlightenment without having gone through all this, you are nothing but a liar and are bound for hell. Bear all I have said in mind-practice truly.

TAKUSUI (沢水, 17th-18th centuries, Rinzai)

SERMON

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Takashi Ikemoto [池本喬 1906-1980]

In: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, pp. 70-71.1. If you desire the attainment of satori, ask yourself this question: Who hears sound? As described in the Surangamasamadhi, that is Avalokitesvara's faith in the hearer. Since there is such a hearer in you, all of you hear sounds. You may say that it is the ear that hears, yet the ear is but a mechanism. If it could hear by itself, then the dead could hear our prayers for them. Inside you, then, is a hearer.

Now, this is the way to apply yourself: whether or not you hear anything, keep asking who the hearer is. Doubt, scrutinize, paying no attention to fancies or ideas. Strain every nerve without expecting anything to happen, without willing satori. Doubt, doubt, doubt. If even one idea arises, your doubt is not sufficiently strong, and you must question yourself more intensely. Scrutinize the hearer in yourself, who is beyond your power or vision.

Master Bassui says, “When at wits' end and unable to think another thought, you are applying yourself properly.” Thus do not look around, but devote yourself utterly to doubting self-examination until you forget where you are or even that you live. This may lead you to feel completely at sea. Yet you must persist in the search for the hearer, sweating, like a dead man, until you are unconscious, a lump of great doubt. But look! That lump will suddenly break up and out of it will leap the angel of the awakening, the great satori consciousness. It is as if one awoke from the deepest dream, literally returned to life.

2. In Zen practice a variety of supernatural phenomena may be experienced. For example, you may see ghostly faces, demons, Buddhas, flowers, or you may feel your body becoming like that of a woman, or even purified into a state of non-existence. If this happens, your “doubt in practice” is still inadequate, for if in perfect doubt you will not have such illusions. Indeed it is only when you are not alert that you meet with them. Do not shrink from them, nor prize them. Just doubt and examine yourself all the more thoroughly.

3. Zen practitioners must accept the fact that while in meditation they are likely to suffer one or more of the three maladies: kon, san, and chin. Kon is sleepiness and san instability, both of which are too well known for comment Chin, on the other hand, is a grave malady and always leads to unhappy results. It is a state in which one is free from sleepiness and instability, and all mentalization ceases. One feels gay, immaculate; one can go on in zazen for hours on end. One has a feeling that all things are equal, neither existent nor non-existent, right nor wrong. Those possessed by chin regard it as satori—a most dangerous delusion. If you were to remain in this state, you would go far astray. At such times, in fact, you must have the greatest doubt.

BANKEI-EITAKU (1622-1693, Rinzai)

THE ZEN OF BIRTHLESSNESS

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Takashi Ikemoto [池本喬 1906-1980]

In: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, pp. 74-88.1.

How lucky you are these days! When I was young there wasn't a good master to be found. At least I couldn't uncover one. But the truth is I was rather simple when young, and made one blunder after another. And the fruitless efforts! I don't suppose 111 ever forget those days, if only because they were so painful. That's why I come here every day. I want to teach you how to avoid the blunders I made. How lucky you are these days!

I'm going to tell you about some of my mistakes, and I know you're clever enough—every one of you—to learn from what I say. If by chance one of you should be led astray by my example, the sin will be unpardonable. That must be avoided at all costs. Indeed it was only after great hesitation that I decided to tell you of my experiences. Remember then, you can learn from me without imitating.

My parents came here from the island of Shikoku, and it was right here [the province of Harima in Hyogo Prefecture] that I was born. My father was a lordless samurai and a Confucian scholar as well, but he died when I was a child and I was brought up by my mother. She was to tell me later that I was boss of all the children in the neighborhood (which led me to do a lot of mischief) and that roughly from my third year I began to loathe death, so much so in fact that when I cried all she had to do was mimic a corpse, or even say “death,” and I'd stop crying and become good.

When yet a small boy I became interested in Confucianism, which in those days was very popular. One day while reading Great Learning [a classic of Chinese philosophy] I came upon the sentence, “The path of the Great Learning lies in clarifying illustrious virtue.” This was completely beyond me, and I wondered about illustrious virtue for days on end, asking teacher after teacher, but to no avail. Finally one of them took me aside and said, “Go to a Zen priest. They know all about difficult things of this kind. All we do, day in, day out, is explain the meaning of the Chinese characters and, of course, lecture a bit. We know nothing about your ‘illustrious virtue,' I'm afraid. Go ask a Zen priest, I tell you.”

I'd have been happy to follow his advice, but there were no Zen priests around at the time. One of the chief motives for my wanting to know about illustrious virtue was that I felt duty bound to teach my mother the path of the Great Learning before she died. I kept going to hear all the Confucian and Buddhist lectures, and would return to her with the wisdom that had been imparted to me, but, alas, my questions remained unanswered.

One day I remembered a certain Zen master and went to him full of expectation. At once I asked him about illustrious virtue. He looked at me gravely and said that to understand I would have to sit in Zen meditation. Soon I would be able to grasp it. Well, I bst no time. Often I would go into the mountains and sit in Zen without taking a morsel for a week, or I would go to a rocky place and, choosing the sharpest rock, meditate for days on end, taking no food, until I toppled over. The results? Exhaustion, a shrunken stomach, and an increased desire to go on.

I returned to my village and entered a hermitage, where sleeping in an upright position and living arduously, I gave myself up to the old spiritual exercise of repeating the name of Amitabha. The results? More exhaustion, and huge painful sores on my bottom. It was impossible for me to sit in comfort, but in those days I was pretty tough. Nevertheless to ease the pain, I had to place layers of soft paper under me, which as they lost their effectiveness had constantly to be replaced. Sometimes I was forced to use cotton, so atrocious was the pain.

I knew I was overdoing it, of course, and finally I became seriously ill. Soon I was bringing up blood, lumps the size of a thumb end. One day I spat on the wall and watched fascinated as the lump of blood rolled down. I was in bad shape, I can tell you. On the advice of friends I engaged a servant to nurse me. Once for seven days running I could eat nothing but a gruel of thin rice. I felt my time was up and kept saying to myself, “No help for it. Soon I'II the without obtaining my old desire.”

Suddenly, while at the very depths, it struck me like a thunderbolt that I had never been born, and that my birthlessness could settle any and every matter. This seemed to be my satori, the awakening I had been waiting for. I realized then that because I'd been ignorant of this simple truth, I'd suffered needlessly.

I began to feel better, and my appetite returned. I called my servant over and said, “I want a big bowl of rice. Right now.” He looked puzzled, for he'd been expecting me to keel over; then he set about in a flurry to prepare the meal. In fact he made it so quickly, and in such a state, that the rice was only half-done and stiff. But I ate three bowls and, I can assure you, it didn't disagree with me. Daily my health improved, and soon I was able to accomplish the greatest desire of my life: I was able to get my mother to see the truth, the secret of birthlessness, before she died.

What I wanted now was the “certification” of my satori. My teacher of Confucianism mentioned a Zen priest by the name of Gudo in the province of Mino who would be able to say whether my experience was genuine. I went to Mino in search of him, but unfortunately he had left a few days before for Tokyo. Not wanting the journey to be a waste of time, I called on some Zen priests of Mino and asked if they would aid me. Immediately they complied by giving me their idea of true Zen. I listened carefully, then said, “Please pardon my impudence, but I want to say something. Your opinions are good as far as they go, but frankly you don't go deep enough. At any rate, I'm not satisfied.”

At this their spokesman, who had impressed me as an honest and humble man, said, “You're right, I'm afraid. All we do is merely memorize the sutras and some of the Zen writings, then repeat them like parrots to anyone who will listen. I'm afraid none of us has experienced satori, in spite of knowing that a man who has not done so will never hit the mark. We really envy you.”

I thanked them and returned home where I kept to myself most of the time and observed how teachable men were, and I weighed the manner in which I could best help them. One day I chanced to learn that a Zen master, Doja, had come to Nagasaki from China. He would be just the man to be my witness, I thought, and straightaway I went to him and told him of my awakening, which had enabled me to virtually transcend life and death. He assured me that I had experienced the real thing and ended up by congratulating me. Naturally I was very pleased, and very grateful to him.

Now it was my turn to begin helping others, and I have been doing just that ever since. That's why I come here to talk to you. It is my desire to bear witness to your satori. You must feel that you are favored. Come forward and let me know if you have had an awakening, and those of you who haven't had the experience, listen carefully to my words. It's in each of you to utterly change your life!

The birthless Buddha-mind can cut any and every knot. You see, the Buddhas of the past, present and future, and all successive patriarchs should be thought of as mere names for what has been born. From the viewpoint of birthlessness, they are of little significance. To live in a state of non-birth is to attain Buddhahood; it is to keep your whereabouts unknown not only to people but even to Buddhas and patriarchs. A blessed state. From the moment you have begun to realize this fact, you are a living Buddha, and need make no further efforts on your tatami mats.

Once you begin to understand this you will be unerring in your judgment of others. These days my eye never sizes up a man incorrectly, and each of you possesses the birthless eye. That's why we call our sect the True-eye as well as the Buddha-mind sect. You must not consider yourselves enlightened Buddhas, of course, until you are able to see into others' minds with your birthless eyes. I suppose you may think what I say doubtful, but the moment you have awakened you'll be able to penetrate the minds of others. To prepare you for this is my greatest desire.

I never lie. I could not deceive you. The doctrine of birthlessness died out long ago in China and Japan, but it's now being revived—by me. When you have fully settled in the immaculate Buddha-mind of non-birth, nothing will deceive you, no one will be able to persuade you a crow is a heron. When you've achieved the final enlightenment, you'll be sure of the truth at all times. Nothing, I repeat, no one, will be able to deceive you.

When as a young bonze I began preaching birthlessness there wasn't anyone around who could understand. They were frightened, and they must have thought me a heretic, as bad as a Roman Catholic. Not a single person dared approach me. But gradually they began to see their mistake, and today all you have to do is look around you to see how many come to me. Why, I've hardly any time for myself! Everything in its season, I guess.

In the forty years I've lived here I've instructed many like yourselves, and I've no hesitation in claiming that some of these people are as good in every way as the Zen masters themselves.

2

The mind begotten by and given to each of us by our parents is none other than the Buddha-mind, birthless and immaculate, sufficient to manage all that life throws up to us. A proof: suppose at this very instant, while you face me listening, a crow caws and a sparrow twitters somewhere behind you. Without any intention on your part of distinguishing between these sounds, you hear each distinctly. In so doing you are hearing with the birthless mind, which is yours for all eternity.

Well, we are to be in this mind from now on, and our sect will be known as the Buddha-mind sect. To consider, once again, my example of a moment ago, if any of you feel you heard the crow and the sparrow intentionally, you are deluding yourselves, for you are listening to me, not to what goes on behind you. In spite of this there are moments when you hear such sounds distinctly, when you hear with the Buddha-mind of non-birth. This nobody here can deny. All of you are living Buddhas, because the birthless mind which you possess is the beginning and the basis of all.

Now, if the Buddha-mind is birthless, it is necessarily immortal, for how can what has never been born perish? You've all encountered the phrase “birthless and imperishable” in the sutras, but until now you've not had the slightest proof of its truth. Indeed I suppose like most people you've memorized this phrase while being ignorant of birthlessness.

When I was twenty-five I realized that non-birth is all-sufficient to life, and since then, for forty years, I've been proving it to people just like you. I was the first to preach this greatest truth of life. I ask you, have any of you priests heard anyone else teach this truth before me? Of course not.

3

A certain priest once said to me, “You teach the same thing over and over again. Wouldn't it be a good idea, just for the sake of variety, to tell some of those old and interesting stories illustrative of Buddhist life?”

I may be nothing more than an old dunce, and I suppose it might help some if I did tell stories of that kind, but I've a strong hunch that such preaching poisons the mind. No, I would never carry on in so harmful a way. Indeed I make it a rule not to give even the words of Buddha himself, let alone the Zen patriarchs.

To attain the truth today all one needs is self-criticism. There's no need to talk about Buddhism and Zen. Why, there's not a single straying person among you: all of you have the Buddha-mind. If one of you thinks himself astray, let him come forward and show me in what way. I repeat: there's no such man here.

However, suppose on returning home you were to see one of your children or a servant doing something offensive, and at once you got yourself involved, went astray, turning the Buddha-mind into a demon's, so to speak. But remember, until that moment you were secure in the birthless Buddha-mind. Only at that moment, only then were you deluded.

Don't get involved! Don't get involved with anyone, whoever he happens to be; rather by ridding yourself of the need for others (which really is a form of self-love) remain in the Buddha-mind. Then you will never stray, then you will be a living Buddha for all time.

4

PRIEST: I was bora with a quick temper and, in spite of my master's constant admonitions, I haven't been able to rid myself of it I know it's a vice, but, as I said, I was born with it. Can you help me?

BANKEI: My, what an interesting thing you were born with! Tell me, is your temper quick at this very moment? If so, show me right off, and I'll cure you of it

PRIEST: But I don't have it at this moment

BANKEI: Then you weren't born with it If you were, you'd have it at all times. You lose your temper as occasion arises. Else where can this hot temper possibly be? Your mistake is one of self-love, which makes you concern yourself with others and insists that you have your own way. To say you were born a hothead is to tax your parents with something that is no fault of theirs. From them you received the Buddha-mind, nothing else.

This is equally true of other types of illusion. If you don't fabricate illusions, none will disturb you. Certainly you were born with none. Only your selfishness and deplorable mental habits bring them into being. Yet you think of them as inborn, and in everything you do, you continue to stray. To appreciate the pricelessness of the Buddha-mind, and to steer clear of illusion, is the one path to satori and Buddhahood.

It is essential that you not yield to quick temper, for to yield and then to try to cure it is to double the burden. Mark well how you stand. Indeed you're in a rather fortunate position, for once rid of hot temper, it will be easy for you to strip yourself of other illusions. Remain firmly in the self-sufficient Buddha-mind of non-birth.

My advice, then, is that you accustom yourself to remaining in a state of non-birth. Try it for thirty days, and you'll be incapable of straying from it: you'll live in the Buddha-mind for the rest of your life. Be reborn this very day! You can be if you give your ear to me, and forget as so much rubbish all your preconceptions. Indeed at my one word of exhortation, you can gain satori.

5

Hearing Bankei talk in this way, a layman from the province of Izumo said, “If your teaching is right, one should be able to feel at ease in the Buddha-mind at all times, but frankly it all seems a bit weightless.”

BANKEI: By no means! Those who make light of the Buddha-mind transform it when angry into a demon's, into a hungry ghost's when greedy, into an animal's when acting stupidly. I tell you my teaching is far from frivolous! Nothing can be so weighty as the Buddha-mind. But perhaps you feel that to remain in it is too tough a job? If so, listen and try to grasp the meaning of what I say. Stop piling up evil deeds, stop being a demon, a hungry ghost, an animal. Keep your distance from those things that transform you in that way, and you'll attain the Buddha-mind once and for all. Don't you see?

LAYMAN: I do, and I am convinced.

6

PRIEST: When you are successful in making me think of my birthlessness, I find myself feeling idle all day.

BANKEI: One in the Buddha-mind is far from idle. When you are not in it, when you sell it, so to speak, for worthless things you happen to be attached to, then you are being idle.

The priest remained silent.

BANKEI: Remain in non-birth, and you will never be idle.

7

PRIEST: Once in the Buddha-mind, I am absent-minded.

BANKEI: Well, suppose you are absent-minded as you say. If someone pricked you in the back with a gimlet, would you feel the pain?

PRIEST: Naturally!

BANKEI: Then you are not absent-minded. Feeling the pain, your mind would show itself to be alert. Follow my exhortation: remain in the Buddha-mind.

8

PRIEST: I often find myself straying from the Buddha-mind. Perhaps it's that I haven't yet seen the truth. Please help me.

BANKEI: The parent-begotten birthless mind is possessed by all, and none truly strays from it if he is aware of doing so. It is that you turn the Buddha-mind into something else. I repeat: aware of the Buddha-mind, you cannot have strayed. Understand? Even in the deepest sleep you're not away from it.

Whether here or at home, remain just as you are now, listening to my exhortation, and you'll feel firmly in the Buddha-mind. It's only when you're greedy or selfish that you feel yourself astray. Remember this: there isn't a sinful person who was born that way. Take the case of the thief. He wasn't born that way. Perhaps when a child he happened to have a sinful idea, acted upon it, and let the habit develop of itself. When apprehended and questioned he will of course speak of an inborn tendency. Nonsense! Show him he's wrong, and he will give up stealing, and in so doing he can immediately attain the everlasting Buddha-mind.

In my home town there lived a pickpocket who was so skillful he could tell at a glance how much money was being carried by someone approaching. When finally nabbed and imprisoned for a few years, he started to change his ways, and when set free he became a sculptor of Buddhist images. He died a holy death, praying to Amitabha for eternal salvation. This shows what a man who repents past conduct is capable of. I tell you no one is born to sin. It's all a question of will.

9

LAYMAN: Though I undertake Zen discipline, I often find myself lazy, weary of the whole thing, unable to advance.

BANKEI: Once in the Buddha-mind there's no need to advance, nor is it possible to recede. Once in birthlessness, to attempt to advance is to recede from the state of non-birth. A man secure in this state need not bother himself with such things: he's above them.

10

LAYMAN: They say you're able to read minds. Is that true?

BANTEI: No such thing happens in our sect. Even if one of us should possess supernatural powers, being in the birthless Buddha-mind he would not use it. I suppose you think I have such powers because I'm always commenting on your personal affairs, but really I'm no different from you. In the Buddha-mind all have the same gifts, for all puzzles are solved by it, all problems overcome. Non-birth is really a very practical doctrine. By criticizing, the master hopes to instruct: that's the long and short of it. And that's why I'm always being so personal Oh, we're very down-to-earth here!

11

PRIEST: For a long time now I've been trying to understand the story of Hyakujo and the Fox (The second koan in Mumonkan, which concerns a monk who had been transformed into a fox because of his denial of cause-and-effect, and who was enlightened by the master Hyakujo's affirmation of it.), but it's beyond me—probably because I haven't involved myself in wholehearted contemplation. Please enlighten me.

BANKEI: We shouldn't concern ourselves with such old wives' tales. The trouble is you're still ignorant of the Buddha-mind which, birthless and immaculate, unties any and every knot.

12

PRIEST (on hearing Bankei chasten the priest of the foregoing): Do you mean to say all the old Zen-men's words and questions are useless?

BANKEI: The old masters' answers were given on the spot to questions asked them, but those questions and their given answers should not concern us. Of course, I'm in no position to say what use they have, but one thing I know: once in the Buddha-mind, one need not fret over them. All your attention is given to irrelevant matters; you stray. Most dangerous!

13

The Buddha-mind in each of you is immaculate. All you've done is reflected in it, but if you bother about one such reflection, you're certain to stray. Your thoughts don't lie deep enough-they rise from the shallows of your mind.

Remember that all you see and hear is reflected in the Buddha-mind and influenced by what was previously seen and heard. Needless to say, thoughts aren't entities. So if you permit them to rise, reflect themselves, or cease altogether as they're prone to do, and if you don't worry about them, you'll never stray. In this way let one hundred, nay, one thousand thoughts arise, and it's as if not one has arisen. You will remain undisturbed.

14

PRIESTESSES OF THE VINAYA SCHOOL [a sect of Buddhism that emphasizes formal monastic rules]: Can we enter nirvana by simply observing the priestess' two hundred and fifty commandments?

BANKET. One who doesn't drink wine need not be told he shouldn't. Questions of omission or commission apply only to bad priests and priestesses. If the Vinaya sect makes a merit of obeying commandments, it's merely admitting the presence of sinful members. Stay in the Buddha-mind of non-birth, and such considerations will prove unnecessary.

15

BANKEI: The bell rings, but you hear the sound before it rings. The mind that is aware of the bell before it rings is the Buddha-mind. If however you hear the bell and then say it is a bell, you are merely naming what's been born, a thing of minor importance.

16

The only thing I tell my people is to stay in the Buddha-mind. There are no regulations, no formal discipline. Nevertheless they have agreed among themselves to sit in Zen for a period of two incense sticks [an hour or so] daily. All right, let them. But they should understand that the birthless Buddha-mind has absolutely nothing to do with sitting with an incense stick burning in front of you. If one keeps in the Buddha-mind without straying, there's no further satori to seek. Whether asleep or awake, one is a living Buddha. Zazen means only one thing-sitting tranquilly in the Buddha-mind. But really, you know, one's everyday life, in its entirety, should be thought of as a kind of sitting in Zen.

Even during one's formal sitting, one may leave one's seat to attend to something. In my temple, at least, such things are allowed. Indeed it's sometimes advisable to walk in Zen for one incense stick's burning, and sit in Zen for the other. A natural thing, after all. One can't sleep all day, so one rises. One can't talk all day, so one engages in zazen. There are no binding rules here.

Most masters these days use devices (koan, etc.) to teach, and they seem to value these devices above all else—they can't get to the truth directly. They're little more than blind fool! Another bit of their stupidity is to hold that, according to Zen, unless one has a doubt he proceeds to smash, he's good for nothing. Of course, all this forces people to have doubts. No, they never teach the importance of staying in the birthless Buddha-mind. They would make of it a lump of doubt. A very serious mistake.

ZEN ANECDOTES

Translated by Lucien Stryk & Takashi Ikemoto [池本喬 1906-1980]

In: ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews

Anchor Books, Doubleday & Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, 1963, pp. 99-133.

Cf. Chapter XXVI in: World of the Buddha: An Introduction to the Buddhist Literature

edited with introduction and commentaries by Lucien Stryk

Garden City, N.Y. : Doubleday, 1968.

Once a tyro asked a Zen master, “Master, what is the First Principle?” Without hesitation the master replied, “If I were to tell you, it would become the Second Principle.” Such anecdotes-and they are legion-are chiefly responsible for Zen Buddhism’s appeal to those not normally interested in philosophy, and the best of them share with the best jokes of a certain type a degree of compactness, point, and wisdom to be found only in the finest writing. Yet Zen anecdotes are meant to do far more than cause laughter: for the most part they are based on dramatic confrontations, during dokusan (meeting between master and disciple), whose purpose is to jerk the unenlightened disciple from a state of hebetude and make it possible for him to experience satori, see into his true being. Many of the anecdotes are very old, drawn from works like the ancient collection of stories with commentaries, Hekiganroku (Blue Cliff Record), another Chinese book, the early thirteenth-century Mu-mon-kan (Barrier Without Gate), and the late thirteenth-century Japanese work Shaseki-shu (Stone and Sand Collection). Some anecdotes are quite serious in tone, their purpose being to illustrate important Mahayana attitudes (number ten in the following selection is a good example), but for the most part they are farcical, illogical in development, and highly paradoxical Whether the purpose of a story is to amuse, shock, or edify, or do all three at the same time, like this one, which is greatly condensed, it speaks for itself: Two monks, one old, one young, came to a muddy ford where a beautiful girl was deliberating whether to cross. The elder monk grabbed her and, without a word, carried her across. As they continued on their way the younger, astonished at the sight of his companion touching a woman, kept chattering about it, until at last the elder monk exclaimed, “What! Are you still carrying that girl? I put her down as soon as we crossed the ford.”

(Addenda by Gabor Terebess)

1

When Ninagawa-Shinzaemon (蜷川 新左衛門), linked-verse poet and Zen devotee, heard that Ikkyu (一休宗純 Ikkyū Sōjun, 1394-1481, Rinzai), abbot of the famous Daitokuji in Murasakino (violet field) of Kyoto, was a remarkable master, he desired to become his disciple. He called on Ikkyu and the following dialogue took place at the temple entrance:

IKKYU: Who are you?

NINAGAWA: A devotee of Buddhism.

IKKYU: You are from?

NINAGAWA: Your region.

IKKYU: Ah. And what’s happening there these days?

NINAGAWA: The crows caw, the sparrows twitter.

IKKYU: And where do you think you are now?

NINAGAWA: In a field dyed violet.

IKKYU: Why?

NINAGAWA: Miscanthus, morning glories, safflowers, chrysanthemums, asters.

IKKYU: And after they’re gone?

NINAGAWA: It’s Miyagino (field known for its autumn flowering).

IKKYU: What happens in the field?

NINAGAWA: The stream flows through, the wind sweeps over.

Amazed at Ninagawa’s Zen-like speech, Ikkyu led him to his room and served him tea. Then he spoke the following impromptu verse:

I want to serve

You delicacies.

Alas! the Zen sect

Can offer nothing.At which the visitor replied:

The mind which treats me

To nothing is the original void—

A delicacy of delicacies.Deeply moved, the master said, “My son, you have learned much.”

2One day the Lord Mihara ordered a painter to do a picture for him, and a few weeks later the artist brought him a picture of a wild goose. As soon as his eyes fell on the painting, the lord cried out, “Wild geese fly side by side. Your picture is symbolic of revolt!”

The lord’s attendants, frightened out of their wits, sought out Motsugai (武田物外 Takeda Motsugai/Butsugai, aka 物外不遷 Butsugai Fusen 1795-1867, Soto), a formidable Zen master, who, besides being a favorite of the lord, was a man of great strength and talent. He was nicknamed Fist Bonze because he could punch a hole in a board, and he was also a good lancer and an expert horseman. But more important to the lord’s attendants, he was very wise and skilled with the pen.

Motsugai hastened to Lord Mihara and, casting but a glance at the picture, wrote the following over the painted bird:

The first wild goose!

Another and another and another

In endless succession.Lord Mihara’s good humor was restored, and both the artist and Motsugai were generously rewarded.

3Kato-Dewanokami-Yasuoki, lord of Osu in the province of Iyo, was passionate about the military arts. One day the great master Bankei (盤珪永琢 Bankei Yōtaku, 1622-1693) called on him and, as they sat face to face, the young lord grasped his spear and made as if to pierce Bankei. But the master silently flicked its head aside with his rosary and said, “No good. You’re too worked up.”

Years later Yasuoki, who had become a great spearsman, spoke of Bankei as the one who had taught him most about the art.

4Date-Jitoku (伊達自得, aka 伊達宗広 or 千広 Date Munehiro or Chihiro, 1802-1877), a fine waka poet and a retainer of Lord Tokugawa, wanted to master Zen, and with this in mind made an appointment to see Ekkei (越溪守謙 Ekkei Shuken, 1810-1884), abbot of Shokokuji in Kyoto and one widely known for his rigorous training methods. Jitoku was ambitious and went to the master full of hopes for the interview. As soon as he entered Ekkei's room, however, even before being able to utter a word, he received a blow.

He was, of course, astonished, but as it is a strict rule of Zen to do or say nothing unless asked by the master, he withdrew silently. He had never been so mortified. No one had ever dared strike him before, not even his lord. He went at once to Dokuon (荻野独園 Ogino Dokuon, 1819-1895), who was to succeed Ekkei as abbot, and told him that he planned to challenge the rude and daring master to a duel.

“Can't you see that the master was being kind to you?” said Dokuon. “Exert yourself in zazen, and you'll discover for yourself what his treatment of you means.”

For three days and nights Jitoku engaged in desperate contemplation, then, suddenly, he experienced an ecstatic awakening. This, his satori, was approved by Ekkei.

Jitoku called on Dokuon again and after thanking him for the advice said, “If it hadn't been for your wisdom, I would never have had so transfiguring an experience. As for the master, well, his blow was far from hard enough.”

5Kanzan (関山慧玄 Kanzan Egen, 1277–1360), aka 無相大師 Musō Daishi, Rinzai), the National Teacher, gave Fujiwara-Fujifusa the koan “Original Perfection.” For many days Fujifusa sat in Zen. When he finally had an intuition, he composed the following:

Once possessed of the mind that has always been,

Forever I’ll benefit men and devas both.

The benignity of the Buddha and Patriarchs can hardly be repaid.

Why should I be reborn as horse or donkey?When be called on Kanzan with the poem, this dialogue took place:

KANZAN: Where’s the mind?

FUJIFUSA: It fills the great void.

KANZAN: With what will you benefit men and devas?

FUJIFUSA: I shall saunter along the stream, or sit down to watch the gathering clouds.

KANZAN: Just how do you intend repaying the Buddha and Patriarchs?

FUJIFUSA: The sky’s over my head, the earth under my feet.

KANZAN: All right, but why shouldn’t you be reborn as horse or donkey?

At this Fujifusa got to his feet and bowed.

“Good!” Kanzan said with a loud laugh. “You’ve gained perfect satori.”

6Son-O (Sonno Sōseki) and his disciple Menzan (面山瑞方 Menzan Zuihō, 1683-1769), Soto) were eating a melon together. Suddenly the master asked, “Tell me, where does all this sweetness come from?”

“Why,” Menzan quickly swallowed and answered, “it’s a product of cause and effect.”

“Bahl That’s cold logic!”

“Well,” Menzan said, “from where then?”

“From that very ‘where’ itself, that’s where.”