ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

J.D. Salinger's Zen

Born: Jerome David Salinger, Manhattan, New York, 1st January, 1919, died in New Hampshire on January 28, 2010.

A paparazzo's shot of Salinger

Tartalom |

Contents |

Camille Scaysbrook

The Relationship Between the Writings of JD Salinger and Zen Buddism

Often the first thing a reader of Salinger's writings will ask him or her self after reading one of his stories is "What did that mean? What was the point behind my journey?". As one critic puts it "Salinger's mode of Zen Buddhism offers for this uneasy and unresolved conflict".

The teacher/student relationship is integral to Zen Buddhism. Often Salinger's characters will play the part of teacher, while we the student, and/or another character will recieve from them (and their author) a koan to solve and thus reach our next stage of enlightenment.

This is very much the case in "The Catcher in the Rye". While it appears in the second last chapter that Holden Caulfield has achieved his moment of enlightenment; his nirvana, in the last page-long chapter Holden tells us "that's all I'm going to tell you" and proceeds to ask the kind of questions which have plagued him throughout the book. It seems that he has returned to square one, and that is the last glimpse we recieve of him. However, we realise that the fact that Holden's quest never ends is an end in itself. Like the Buddhist cycle he has been reborn and given a new start, and we realise through this that like Holden, we have undergone a learning experience.

Examining our mind's reactions to this seeming irrelevance, we realise that with extreme subtlety, the the story has, like the Zen koan, stimulated the mind into other planes of thought to the ones we are used to, and as with the koan we are compelled to find an answer within apparent non - logic.

One of the main ways Salinger uses this student / teacher relationship to express his spirituality is to equate his characters to various real religious figures and principles, in a way updating their teachings to educate a modern audience who, like Holden, do not realise until after the journey how much they have learned.

The Similarity Between Salinger's Characters and Prominent Religious Figures

There has always been speculation on just how autobiographical Salinger's stories and characters are. The media has undertaken many exhaustive searches for the details that will conclusively prove that he is in fact Buddy Glass, Sergeant X or Holden Caulfield. In fact, a letter supposedly exists wherein J.D. Salinger admits that Holden is a portrait of himself as a young adult. However, it is also easy to find the religious figures he embraces in his spiritual life imbued in the characters he creates in his writing life. Sybil of "A Perfect Day for Bananafish" is an obvious example, her name itself meaning in ancient times a mystic or seer. But Holden Caulfield is the most intriguing, and the similarities between himself and various religious figures irrefutable.

Like Buddha, Holden recieves his flash of enlightenment after "meditating" amongst wild animals (at the Zoo). He recieves it not at a river, but in the rain, water being a baptismal symbol in many religions - he says

"My hunting hat really did give me a lot of protection, in a way, but I got soaked anyway. I didn't care, though. I felt so damn happy all of a sudden, the way old Phoebe kept going around and around."

Holden says at the conclusion of the second last chapter, as he witnesses his sister who he has worried about being exposed to the harshness of adult life and change, sitting happily on the carousel - itself a "cycle".

The Use of Techniques of Zen Buddhist Writings in Salinger's Writings

Salinger also uses the techniques of Zen Buddhist writings in his own writings. Often, as stated before, his stories are koans which the reader is beseeched to solve. But he has also been quoted as saying in relation to his writing (and before "Catcher" was published) "I'm a dash man, not a miler. I will probably never write a novel.") He is more content with short story writing - a method of writing characterised by its compactness of narration and message. And one important aspect of Zen is to "convey the message in as few words as possible". One of the Four Statements of Zen is "no dependence on words and letters", and Salinger's message always comes across in the most direct way possible and always with the feeling that the rationality of words can never wholly describe his message - as one critic puts it "When the gesture aspires to pure religious expression, language reaches into silence". The attraction of the koan (and the Japanese haiku poem, another of Salinger's fixations which is named after the great koan writer Haikun) is its compactness, its emotional detachment yet quiet passion - qualities best characterised by the term "moksha". Moshka is a state of impersonal compassion, an attempt to avoid worldliness and replace it with an effortless and continuous love. And this is the main aim of nearly all of Salinger's characters. One book puts it as "a condition of being without losing our identity, at one with the universe, and it requires... a certain harmony between our imaginitive and spiritual responsiveness to all things." This is an almost perfect description of the aims of Salinger as a writer and his characters as people. They crave a oneness and sense from the nonsense-koan that is the world, but instead are hindered by the human egos of themselves and those around them. This is the spiritual search Salinger expresses in his writing.

The Story of Sri Ramakrishna

At the age of sixteen he went to Calcutta but was disgusted by the materialistic ideals of the people of the great metropolis. He eventually became a priest in the Dakenshineswar Temple and practically without the help of any teacher obtained the vision of God.

The Story of Gautama Buddha

At the age of sixteen Gautama faced the reality of adulthood. His family was rich and he lived a life of luxury but was not satisfied by it and made a journey. For 6 years he wandered the Ganges, learning from famous religious teachers, none of which satisfied him. Meditating by the river Neranjara after years of meditation in a forest full of wild animals, he suddenly experienced unexpected and indescribable enlightenment. He realised that once a man stops trying to control his life and environment, and attempting the impossible, he feels liberated from the everlasting round of birth and death.

The Story of The Catcher in the Rye

A sixteen year old boy named Holden Caulfield (the son of wealthy parents) runs away from school to his home in New York. Wandering the city alone, he is disillusioned by the superficiality of it and its citizens. However, it is through witnessing his young sister Phoebe going round and round on a merry-go-round after a trip to the zoo that he recieves any sort of answer or joy, not from the advices of the school teachers, girl friend and other acquaintances he meets along the way.

In Defense of the ―Ringding Mukta: The Later Work of J.D. Salinger

by Danielle Kristine Herb

A thesis submitted to Oregon State University, 2015

http://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1957/56067/Thesis-Final_DH.2%20(2).pdf;sequence=1

Translation: Nine Stories

by Mateus Domingos

Loughborough University, School of the Arts, 2012

http://www.academia.edu/1778029/Translation_Nine_Stories

On January 27th, 2010, US author J.D. Salinger died. Salinger hadn't published a novel since 1963. Salinger was a part of the school of Buddhism that swept U.S arts and literature in the 1950s Upper West Side Buddhism. The focal point of the encounter with Buddhism and the likes of Salinger, John Cage and Philip Guston, in New York, is often attributed to the class of D.T. Suzuki at Columbia University between 1952-57. At the same time, on the west coast, similar, if looser, Buddhist influences were reaching the San Francisco Renaissance which involved poets such as Allen Ginsberg. The more Salinger developed his ideas of Buddhism and drew them into his characters, the more the critical reception of his work declined.

Salinger came to prominence with the publication of Catcher in the Rye in 1951. He would write recurrently about a set of characters called the Glass family. Each member having “become more and more involved with Zen” in each subsequent story. This is much more telling of Salinger's own increasing interest in Zen Buddhism though, as the stories were not written chronologically: such that in Salinger's last published work, Hapworth 16, 1924 (Salinger, 1965) the story is set during the earliest time of the Glass family, and the young Seymour Glass writes a letter containing “prescient observations concerning the nature of existence.” (Hunter, 2001) Which is often claimed to be a thin veil for authorial self-indulgence.

PDF: "Hyakujo's Geese, Amban's Doughnuts and Rilke's Carrousel: Sources East and West for Salinger's Catcher." by Dennis McCort

Comparative Literature Studies 34.3 (1997): 260-78. Rpt. in Modern Critical Interpretations : J. D. Salinger's "The Catcher in the Rye.” Ed. Harold Bloom. Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 2000. 119-34. Rpt. in Bloom's Modern Critical Interpretations: J. D. Salinger's “The Catcher in the Rye” (New Edition). Ed. Harold Bloom. New York: Bloom's Literary Criticism, 2009. 45-62.

"Zen and Nine Stories." by Bernice Goldstein and Sanford Goldstein

Renascence 22.4 (1970): 171-183. ProQuest.

“The Sound of One Hand Clapping,”

by Tom Davis

Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature 4 (1963): 41–47

Zen in the Art of J.D. Salinger

By Gerald Rosen

Berkeley: Creative Arts Book Company, 1977

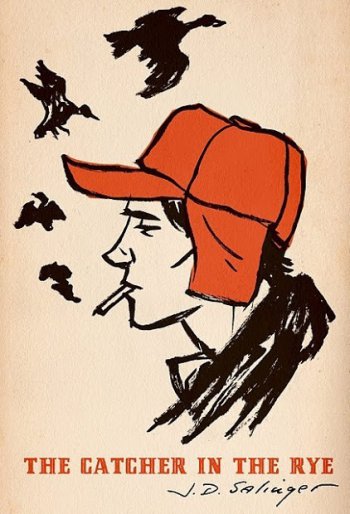

© M. S. Corley

This is not a published book cover, but an artist's homage that is far more striking and evocative than any of the “official” versions.

The artist, M. S. Corley says: ”this was for a contest to mimic old Polish book covers, so that's why I did the brushed lines.”

Will Ducks Fly Away?

The Koan of Holden Caulfield

The funny thing is, though, I was sort of thinking of something else while I shot the bull. I live in New York, and I was thinking about the lagoon in Central Park, down near Central Park South. I was wondering if it would be frozen over when I got home, and if it was, where did the ducks go. I was wondering where the ducks went when the lagoon got all icy and frozen over. I wondered if some guy came in a truck and took them away to a zoo or something. Or if they just flew away.

I'm lucky, though. I mean I could shoot the old bull to old Spencer and think about those ducks at the same time. It's funny. You don't have to think too hard when you talk to a teacher. All of a sudden, though, he interrupted me while I was shooting the bull. He was always interrupting you.

The Catcher in the Rye, Chapter 2The driver was sort of a wise guy. "I can't turn around here, Mac. This here's a one-way. I'll have to go all the way to Ninedieth Street now."

I didn't want to start an argument. "Okay," I said. Then I thought of something, all of a sudden. "Hey, listen," I said. "You know those ducks in that lagoon right near Central Park South? That little lake? By any chance, do you happen to know where they go, the ducks, when it gets all frozen over? Do you happen to know, by any chance?" I realized it was only one chance in a million.

He turned around and looked at me like I was a madman. "What're ya tryna do, bud?" he said. "Kid me?"

"No--I was just interested, that's all."

He didn't say anything more, so I didn't either. Until we came out of the park at Ninetieth Street. Then he said, "All right, buddy. Where to?"

The Catcher in the Rye, Chapter 9The cab I had was a real old one that smelled like someone'd just tossed his cookies in it. I always get those vomity kind of cabs if I go anywhere late at night. What made it worse, it was so quiet and lonesome out, even though it was Saturday night. I didn't see hardly anybody on the street. Now and then you just saw a man and a girl crossing a street, with their arms around each other's waists and all, or a bunch of hoodlumy-looking guys and their dates, all of them laughing like hyenas at something you could bet wasn't funny. New York's terrible when somebody laughs on the street very late at night. You can hear it for miles. It makes you feel so lonesome and depressed. I kept wishing I could go home and shoot the bull for a while with old Phoebe. But finally, after I was riding a while, the cab driver and I sort of struck up a conversation. His name was Horwitz. He was a much better guy than the other driver I'd had. Anyway, I thought maybe he might know about the ducks.

"Hey, Horwitz," I said. "You ever pass by the lagoon in Central Park? Down by Central Park South?"

"The what?"

"The lagoon. That little lake, like, there. Where the ducks are. You know."

"Yeah, what about it?"

"Well, you know the ducks that swim around in it? In the springtime and all? Do you happen to know where they go in the wintertime, by any chance?"

"Where who goes?"

"The ducks. Do you know, by any chance? I mean does somebody come around in a truck or something and take them away, or do they fly away by themselves--go south or something?"

Old Horwitz turned all the way around and looked at me. He was a very impatient-type guy. He wasn't a bad guy, though. "How the hell should I know?" he said. "How the hell should I know a stupid thing like that?"

"Well, don't get sore about it," I said. He was sore about it or something.

"Who's sore? Nobody's sore."

I stopped having a conversation with him, if he was going to get so damn touchy about it. But he started it up again himself. He turned all the way around again, and said, "The fish don't go no place. They stay right where they are, the fish. Right in the goddam lake."

"The fish--that's different. The fish is different. I'm talking about the ducks," I said.

"What's different about it? Nothin's different about it," Horwitz said. Everything he said, he sounded sore about something. "It's tougher for the fish, the winter and all, than it is for the ducks, for Chrissake. Use your head, for Chrissake."

I didn't say anything for about a minute. Then I said, "All right. What do they do, the fish and all, when that whole little lake's a solid block of ice, people skating on it and all?"

Old Horwitz turned around again. "What the hellaya mean what do they do?" he yelled at me. "They stay right where they are, for Chrissake."

"They can't just ignore the ice. They can't just ignore it."

"Who's ignoring it? Nobody's ignoring it!" Horwitz said. He got so damn excited and all, I was afraid he was going to drive the cab right into a lamppost or something. "They live right in the goddam ice. It's their nature, for Chrissake. They get frozen right in one position for the whole winter."

"Yeah? What do they eat, then? I mean if they're frozen solid, they can't swim around looking for food and all."

"Their bodies, for Chrissake--what'sa matter with ya? Their bodies take in nutrition and all, right through the goddam seaweed and crap that's in the ice. They got their pores open the whole time. That's their nature, for Chrissake. See what I mean?" He turned way the hell around again to look at me.

"Oh," I said. I let it drop. I was afraid he was going to crack the damn taxi up or something. Besides, he was such a touchy guy, it wasn't any pleasure discussing anything with him. "Would you care to stop off and have a drink with me somewhere?" I said.

He didn't answer me, though. I guess he was still thinking. I asked him again, though. He was a pretty good guy. Quite amusing and all.

"I ain't got no time for no liquor, bud," he said. "How the hell old are you, anyways? Why ain'tcha home in bed?"

"I'm not tired."

When I got out in front of Ernie's and paid the fare, old Horwitz brought up the fish again. He certainly had it on his mind. "Listen," he said. "If you was a fish, Mother Nature'd take care of you, wouldn't she? Right? You don't think them fish just die when it gets to be winter, do ya?"

"No, but--"

"You're goddam right they don't," Horwitz said, and drove off like a bat out of hell. He was about the touchiest guy I ever met. Everything you said made him sore.

The Catcher in the Rye, Chapter 12I didn't feel too drunk any more when I went outside, but it was getting very cold out again, and my teeth started chattering like hell. I couldn't make them stop. I walked over to Madison Avenue and started to wait around for a bus because I didn't have hardly any money left and I had to start economizing on cabs and all. But I didn't feel like getting on a damn bus. And besides, I didn't even know where I was supposed to go. So what I did, I started walking over to the park. I figured I'd go by that little lake and see what the hell the ducks were doing, see if they were around or not, I still didn't know if they were around or not. It wasn't far over to the park, and I didn't have anyplace else special to go to--I didn't even know where I was going to sleep yet--so I went. I wasn't tired or anything. I just felt blue as hell.

Then something terrible happened just as I got in the park. I dropped old Phoebe's record. It broke-into about fifty pieces. It was in a big envelope and all, but it broke anyway. I damn near cried, it made me feel so terrible, but all I did was, I took the pieces out of the envelope and put them in my coat pocket. They weren't any good for anything, but I didn't feel like just throwing them away. Then I went in the park. Boy, was it dark.

I've lived in New York all my life, and I know Central Park like the back of my hand, because I used to roller-skate there all the time and ride my bike when I was a kid, but I had the most terrific trouble finding that lagoon that night. I knew right where it was--it was right near Central Park South and all--but I still couldn't find it. I must've been drunker than I thought. I kept walking and walking, and it kept getting darker and darker and spookier and spookier. I didn't see one person the whole time I was in the park. I'm just as glad. I probably would've jumped about a mile if I had. Then, finally, I found it. What it was, it was partly frozen and partly not frozen. But I didn't see any ducks around. I walked all around the whole damn lake--I damn near fell in once, in fact--but I didn't see a single duck. I thought maybe if there were any around, they might be asleep or something near the edge of the water, near the grass and all. That's how I nearly fell in. But I couldn't find any.

The Catcher in the Rye, Chapter 20Cf. The original koan of Ch'an Master Pai Chang

Translated from 古尊宿語錄 Guzunsu yulu [Recorded Sayings of the Ancient Worthies]

by 陸寬昱 Lu K'uan Yü (Charles Luk; Lu Kuanyu, 1898-1978)

The Transmission of the Mind Outside the Teaching

Rider, London 1974, p. 50.

One day Pai Chang* walked with Ma Tsu** down the road

when they heard the cries of wild geese in the sky. Ma Tsu

asked, 'What is this sound?' Pai Chang replied, 'The cries of

wild geese.' A long while later Ma Tsu asked, 'Where have

they gone?' Pai Chang replied, 'Flown away.' Ma Tsu turned

back and twisted Pai Chang's nose. Pai Chang cried with

pain and Ma Tsu said, 'Yet you spoke of flying away.'* 百丈懷海 Baizhang Huaihai (720-814), Rōmaji: Hyakujō Ekai

** 馬祖道一 Mazu Daoyi (709-788), Rōmaji: Baso Dōitsu

“…evidently Mrs. Fedder has been haunted for days by my remark at dinner one night that I'd like to be a dead cat. She asked me at dinner last week what I intended to do after I got out of the Army. Did I intend to resume teaching at the same college? Would I go back to teaching at all? Would I consider going back on the radio, possibly as a ‘commentator' of some kind? I answered that it seemed to me that the war might go on forever, and that I was only certain that if peace ever came again I would like to be a dead cat. Mrs. Fedder thought I was cracking a joke of some kind. A sophisticated joke. She thinks I'm very sophisticated, according to Muriel. She thought my deadly-serious comment was the sort of joke one ought to acknowledge with a light, musical laugh. When she laughed, I suppose it distracted me a little, and I forgot to explain it to her. I told Muriel tonight that in Zen Buddhism a master was once asked what was the most valuable thing in the world, and the master answered that a dead cat was, because no one could put a price on it. M. was relieved, but I could see she could hardly wait to get home to assure her mother of the harmlessness of my remark.”

– Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters by J.D. Salinger

Cf. The Most Valuable Thing in the World

Source: 101 Zen Stories / transcribed by Nyogen Senzaki and Paul Reps, Philadelphia, David McKay Company, 1940Sozan*, a Chinese Zen master, was asked by a student: "What is the most valuable thing in the world?"

The master replied: "The head of a dead cat."

"Why is the head of a dead cat the most valuable thing in the world?" inquired the student.

Sozan replied: "Because no one can name its price."

* 曹山本寂 Caoshan Benji (840-901), Rōmaji: Sōzan Honjaku

We know the sound of two hands clapping. But what is the sound of one hand clapping?

--A ZEN KOAN

The epigraph to Nine Stories (1953) quoting the well-known koan of Rinzai master 白隠慧鶴 Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1769)

Carolyn Hack

Smiling children clap their hands at all of the happiness in this great big world. Without a care, their imaginations run wild. They lose themselves in colorful stories and delight in life's little things. As time goes by, however, stories end, little things become littler as people grow bigger, and innocence slowly breaks apart and disappears. The smiling child without her innocence is no longer whole, and her world will never be the same. We have known the sound of her two small, carefree hands clapping. But what is the sound of one hand clapping? What is left to be heard when an essential part of her youth is missing?

Applauding Adulthood: An Essay on Three of Salinger's Nine StoriesJ.D. Salinger presents this Zen Koan before telling any of his Nine Stories. It opens the door to a theme common to his stories, the loss of innocence. He focuses not only on the loss of innocence with youth, but also on events that have changed his characters forever. Ironically, it is often the children, seemingly the perfect models of carefree life and thought, who make this loss most evident.

"A piece of red tissue paper flapping in the wind against the base of a lamppost." (73) This is the sound of one hand clapping. This is the soft, gentle, yet poignant sound that is heard as a young boy, the narrator of "The Laughing Man," loses a part of his childhood. For months, he was so engaged in the story of the Laughing Man that it became a part of his life. It opened his imagination, let him dream of adventure and excitement. This life it encouraged within him was so active and important that it allowed him to block out the darker aspects of the story, the Laughing Man's deformities and the evil of his enemies. When the story came to an end, however, when the Laughing Man died, so did a piece of the boy's childhood. Suddenly, adventure was not enough. Evil had prevailed; deformities had been unmasked. Imagination could no longer hide the realities thrust upon him. Unfortunately, reality can overpower imagination; innocence, like stories, comes to an end. The Laughing Man's poppy-petal mask, a delicate image, is blown away, leaving only the deformed, almost gruesome, face of reality.

"'I was a nice girl,' she pleaded, 'wasn't I?'" (38) This is the sound of one hand clapping. It is louder, more urgent than the tissue in the wind. It is the sound of innocence remembered, long after it has passed. In "Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut," Eloise realizes the spark of youth that she lost with the death of Walt, a man she truly loved, with help from her young daughter, Ramona. Although Ramona is nearly blind, the eye of her imagination is wide open, and she sees Jimmy, her invisible boyfriend, quite clearly. Eloise is fond of Jimmy and Ramona's make-believe most likely because they subconsciously remind her of the time when she was happiest and still had the innocence of her youth intact, the period during which she was in love with Walt. Walt, who complemented the child within Eloise with his own carefree silliness, was the embodiment of Eloise's innocence. When he was killed, so was the child in Eloise. She did not realize this fact, however, until many years later. Her innocence had drifted away, unnoticed, until Eloise believed she had always been the adult she had come to be. It took a reliving of the experience of Walt's death through Ramona and the death of imaginary Jimmy to make her realize what had happened. When Jimmy was "run over," Ramona quickly replaced him with Mickey (whose invisibleness made him seem equal to Jimmy through Eloise's adult eyes). The anger she showed toward Ramona upon the introduction of Mickey was truly anger she felt toward herself, who replaced Walt with Lew as if it didn't matter, as if no injustice had been committed. She had replaced her inner child with an adult and had never been quite happy since. It was only when she looked at her life through Ramona's glasses that she was able to mourn the loss of Walt, her innocence, her own Jimmy, the invisible, the original, the irreplaceable.

"He...aimed the pistol, and fired a bullet." (18) This is the sound of one hand clapping -- loud, definite, and final. When innocence is lost, it is lost forever. Seymour Glass, the main character in "A Perfect Day For Bananafish," understood this, and it was too difficult for him to handle. Living through the war had stripped him of his inner child. The things he had seen and experienced were too horrible to forget. Because of this, he lost his innocence, and its presence was greatly missed. Seymour felt physically changed by this loss. At the beach, he wore a robe to cover his "tattoos," a strictly adult decoration. These tattoos couldn't be seen, but they were felt. To Seymour, they were the marks of adulthood, which he resented. Although he talked to and played with Sybil, his four-year-old friend, on the day he killed himself, the stories he told her were from the mind of an adult. The bananafish, he told her, who loved to eat bananas, fruits the same color as the little girl's bathing suit, would inevitably die because of their desire for bananas. Seymour, like the bananafish, desired the innocence, the childhood that was wrapped before him in a yellow package. He didn't want to live as an adult. If childhood came to and end, so, he decided, must adulthood. Realizing this, he fired the bullet, dying of his own desires. What's gone is gone; what's done is done.

Although innocence can never be recovered once it is lost, although the show is over when the hands stop clapping, there is still something left behind. Salinger's Nine Stories make this quite clear. The stories end after the loss of innocence has been acknowledged. The reader, then, can decide what will happen to the character, just as she is left with a choice about what to do with her own adulthood. We can choose to go out with a bang or let the wind blow us where it will. It is most important to remember that one hand remains, and a sound can still be made.

Tony Magagna

In J.D. Salinger's short story, "Teddy," the title-character, staring out of a porthole in the ship cabin he is sharing with his parents, muses aloud:

Orange Peels and Apple-Eaters: Buddism in JD Salinger's Teddy"Someone just dumped a whole garbage can of orange peels out the window....They float very nicely....That's interesting....I don't mean its interesting that they float....It's interesting that I know about them being there. If I hadn't seen them, then I wouldn't know they were there, and if I didn't know they were there, I wouldn't be able to say that they even exist....Some of them are starting to sink now. In a few minutes, the only place they'll still be floating will be inside my mind. That's quite interesting, because if you look at it a certain way, that's where they started floating in the first place." (171-72)

These observations, seemingly out of proportion to a simple can of kitchen refuse being tossed into the sea, reflect a strong Buddhist influence on Teddy's thought (and on Salinger's). The way in which Teddy describes the orange peels as appearing in front of him, and then, moments later, beginning to sink out of view - out of existence - points to the Buddhist idea of impermanence; nothing lasts forever - those things that we perceive, and even our own lives, are only temporary occurrences which will, with time, vanish. This passage also reflects the directly related Buddhist belief of non-existence, which teaches that physical existence - whether of self, or time, or even orange peels - is an illusion. Buddhists hold that the materiality of the world only exists within earthly, and therefore false, perceptions; in other words, we fool ourselves into thinking that we, and everything around us, exist in any physical sense. Thus, when Teddy remarks here that the orange peels only exist in his mind, as well as later when, upon leaving the cabin, he states, "After I go out this door, I may only exist in the minds of all my acquaintances....I may be an orange peel" (174), he is, in a Buddhist sense, quite right.

This scene is fairly brief in the context of the story, but in its reflection of Buddhist influences, it is indicative of the story as a whole. Throughout Teddy, Salinger relates several Buddhist principles and philosophies through the characters', and especially Teddy's, statements and actions. The strong influence of Buddhism is apparent even in some of Salinger's basic decisions in constructing and framing the story.

One such decision is Salinger's choice (a tendency in many of his stories) to create and relate the story of his characters without any sense of history. In Teddy, the story opens with all of the key characters aboard an oceanliner, but there is little, if any, information as to how they got there. There are references throughout the story to bits and pieces of biographical information (i.e. Teddy's father is a radio-actor, Teddy makes tapes), but in fact very little. The reader has no sense, really, of where these characters came from, or where they are going. It is as if, like Teddy's orange peels, the characters only came into existence at the point in time when the story begins, and that they will cease to exist the moment it ends. Again, like the scene with the orange peels, this strict focus on the story's present, with no sense of past or future, clearly reflects the Buddhist beliefs of impermanence and non-existence.

Another, and perhaps less abstract, Buddhist influence on Teddy (and Salinger) lies in the structure of the title-character himself. Throughout the story, Salinger portrays Teddy as a genius, a seer, a religious figure, and even a teacher of teachers; the catch is that he's only ten years old! This portrayal, coupled with the references in the story to reincarnation (188), is reflective of the Buddhist (Mahayana particularly) belief in reincarnated rinpochets, or religious figures, and is a product, perhaps, of world-events occurring around the time that Salinger wrote Teddy. During the early 1950's, much of the world's attention was focused on the newly Communist China and their struggle for control of Buddhist Tibet. The spiritual and temporal leader of Tibet at the time was the Fourteenth Dalai Lama - a teenage boy who had been recognized as the reincarnation of the great religious leader since before the age of six. Salinger would certainly have been aware of the Dalai Lama, and the Buddhist belief in child rinpochets, and likely, along with the rest of the Buddhist aspects with which he imbued this story, applied this principle to the figure of the ten-year-old Teddy. Thus, from this Buddhist perspective, it is not entirely strange that such high, especially religious, esteem is given to a young boy.

Within the events of the story itself, and through the actions of the characters, Salinger also relates a great deal of Buddhist philosophy. One such philosophy is the Buddhist tendency to refrain from any form of materialism, whether of the self or of objects. This practice relates, of course, to the beliefs, as mentioned before, of impermanence and non-existence; if objects, including the self, are not real and will only be around for a limited time, then they can have no true value that can be accumulated and flaunted. In Teddy, however, many of the characters, through their actions and affectations, are portrayed in quite the opposite fashion; they are materialistic, narcissistic, and egocentric. Brand names, evidence of material culture, pervade the story; a suitcase is not simply a suitcase, but rather a Gladstone, and Mr. McArdle's (Teddy's father) camera is not simply his camera, but his goddam Leica (172). Clothing also seems to be described in lavish detail as evidence, along with such affectations as the way characters walk and speak, of narcissism. Even the way in which Nicholson smiles is shown by Salinger as indicative of his egocentrism: His smile was not unpersonable, but it was social, or conversational, and related back, however indirectly, to his own ego (184).

Teddy, the epitome in the story of Buddhist ideals, on the other hand, is characterized in an entirely opposite fashion; he has no such materialistic or narcissistic accoutrements. He apparently, much to the chagrin of his father, has no sense of the value of material objects; he uses his father's Gladstone suitcase as a stool, and allows his younger sister to tote the camera around the ship as a plaything. His clothing also sets him in stark contrast to the other characters in their Ivy-league apparel (Nicholson) and their gaudy uniforms (the ship's crew): He was wearing extremely dirty, white ankle-sneakers, no socks, [oversized] seersucker shorts...[and] an overly laundered T shirt that had a hole the size of a dime in the right shoulder (167). Even Teddy's affectations - the way in which he acts - are of a Buddhist nature. Unlike the other characters, whose methods of walking, talking, and smiling highlight their narcissism, Teddy behaves with such concentration on whatever he is doing, that the materialism of the world around him seems to fall away. An instance of this is when the boy is reading over his journal, as if only he and the notebook existed - no sunshine, no fellow passengers, no ship (179). In such a way, with a seeming take-off of the Buddhist Heart Sutra, Salinger successfully sets Teddy apart from the rest of his fellow passengers as one who, having been greatly influenced by Buddhist philosophies, can see through the materialism and egocentrism of his environment.

Another Buddhist principle that is brought to bear in the story through Teddy, in contrast to the other characters, deals with attachment. In the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism, it is taught that life is suffering, and that suffering is caused by the desire to reach out for, and grasp onto, people, objects, experiences, emotions, etc., which, as has been illustrated, are impermanent; thus, when whatever illusion someone has become attached to ceases, that person experiences a great deal of suffering. In Teddy, the title-character observes how his parents, and seemingly everyone else around him, are so caught up in emotional attachment, but he cannot understand why: "I wish I knew why people think it's so important to be emotional....My mother and father don't think a person's human unless he thinks a lot of things are very sad or very annoying or very - very unjust' (186). Such emotional attachment, which for Teddy is incomprehensible, even leads him, in his journal, to proclaim how quite sick he is of poetry (180), because, as we learn later, "[Poets]'re always sticking their emotions in things that have no emotions" (185). In contrast to this apparently Western-world poetry, and further demonstrating Salinger's Buddhist influence, Teddy quotes two Japanese haikus as examples of non-emotional poetry; both haikus are by Basho, a famous Zen poet.

Teddy also applies this idea of emotional attachment to people's fear of death in the story. As with the entire concept of emotion, Teddy cannot understand why the people around him, including his parents and even professors of Religion and Philosophy (193), are so afraid of death and dying. After relating his own hypothetical death-scenario (which, depending on one's interpretation of the story, may be a prophecy), Teddy asks, "What would be so tragic about it, though? What's there to be afraid of, I mean? I'd just be doing what I was supposed to do (193). Teddy goes on to recognize that, of course, his parents would be quite upset if he were to die, but that's only because they have names and emotions for everything (194). This statement clearly relates back to the Buddhist belief that suffering is caused by desire and attachment - Teddy's parents would suffer if he died because they are attached to him and do not accept the Buddhist principle of impermanence.

In this previous example, Salinger, by moving from the everyday issues of materialism and emotion into the much more weighty realm of death and people's relationship towards dying, takes his Buddhist lessons in Teddy to a much higher, philosophical and religious level. These more ponderous issues, including the above speculations on death, come to bear in the story in a lengthy conversation between Teddy and Nicholson, a professor and fellow passenger on the oceanliner. In this discussion, Teddy (and thus Salinger) presents Buddhist principles in a very unique way - by packaging Buddhist belief in Judeo-Christian imagery. This perhaps reflects Salinger's own views on Buddhism; though he is clearly, and strongly influenced by Buddhist philosophy, Salinger himself is not Buddhist, but rather brings the teachings of Buddhism to bear in his Judeo-Christian heritage and environment. Another reason for this meshing of Eastern and Western philosophy could easily be that Saling! er felt, when writing Teddy, that his audience would not be terribly receptive to a simple recitation of Buddhist tenets. America in the 1950's, though becoming far more familiar with Buddhism and Eastern thought, still looked rather warily at new modes of spirituality: as Teddy says to Nicholson, "it's very hard to meditate and live a spiritual life in America. People think you're a freak if you try to (188).

No matter the reason for this syncretism of Buddhist and Judeo-Christian principles, it is quite clear that Salinger embraces such a mix in the language and imagery of Nicholson and Teddy's conversation. Nicholson continuously uses biblical language while talking to Teddy, even when referring to seemingly non-Judeo-Christian experiences. For example, Nicholson, when referring to Teddy's belief that he was an Indian seeking enlightenment in a past life, calls the fact that Teddy (as the Indian meditator) didn't reach final Illumination because he met a lady and became disinterested in meditation, a fall from Grace (188). Teddy himself speaks from within this syncretism, telling of his moment of enlightenment in terms of God, instead of Buddha-nature: "I was six when I saw that everything was God....My sister was only a very tiny child then, and she was drinking her milk, and all of a sudden I saw that she was God and the milk was God" (189). This experience in itself - realizing that all things are connected and the same - is very Buddhist, but by referring to the interconnectedness as God, Teddy is drawing together Buddhism and the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Outside of the simple Judeo-Christian language used to relate Buddhist beliefs in this conversation, by far the most significant example of a syncretism of Eastern and Western philosophy in Teddy, occurs when the title-character is explaining to Nicholson the need to get out of the finite dimensions (189) of life. This idea refers to the Buddhist principle of nonduality, which relates to the aforementioned philosophy of non-existence. Nonduality is a very complicated (at least to Westerners) way of thinking, which denies any attempt to place dimensions, both relative and specific, on objects. This mode of thought is essential to the Buddhist belief that nothing truly exists, for if we can say that an object is big and white, as opposed to small and black, then we give that object an identity which, from a Buddhist perspective, it does not have. In order to deal with how complicated it is for most Westerners to think in this fashion, and to explain why logic, the main barrier to thinking nondualistically, is the first thing you have to get rid of (190) in order to see the real world, Teddy (and Salinger) relates this very Buddhist principle through the Judeo-Christian tradition of Genesis and Original Sin. He asks Nicholson:

"You know that apple Adam ate in the Garden of Eden, referred to in the Bible?....You know what was in that apple? Logic. Logic and intellectual stuff. That was all that was in it. So - this is my point - what you have to do is vomit it up if you want to see things as they really are....The trouble is...most people don't want to see things the way they are. They don't even want to stop getting born and dying all the time....I never saw such a bunch of apple-eaters." (191)

In such a way - by drawing together the Buddhist ideals of nonduality and escaping finite dimensions in order to see true reality, with this fundamental Judeo-Christian image - Salinger, through Teddy, is able to create in the minds of his readers a distinct relationship between the two seemingly disparate religions. He is able to show that, in the same way that Buddhists believe that there is a barrier - logic - in the path to ultimate enlightenment to the true nature of reality, those of the Judeo-Christian tradition believe that when mankind's original ancestors sinned by eating the forbidden fruit, we all lost the purity of Paradise. By having Teddy relate that logic - the Buddhist barrier - came from that forbidden fruit, Salinger draws the people of both sides together in the common goal of ridding themselves of the apple's curse.

Perhaps this, then, is Salinger's true goal with Teddy. By relating Buddhist philosophies and principles in the story, and thereby awakening his readers to the dangers of materialism, egocentrism, and emotional attachment, Salinger is trying to help us escape the finite dimensions of life, and to think outside of the box. We do not have to be Buddhist, or Jewish, or Christian in order to open our minds to a new perspective. As Teddy says to Nicholson, who asks him what he would do to change the education system: I'd try to show [children] how to find out who they are, not just what their names are and things like that...I'd get them to empty out everything their parents and everybody ever told them....I'd want then to begin with all the real ways of looking at things, not just the way all the other apple-eaters look at things (195-96). Maybe, then, we are Teddy's hypothetical pupils - Salinger's real ones - meant to cough up our own piece of the apple, in order to see the orange peels.

Aiming by Deliberately Not Taking Aim

J.D. Salinger's fictional character "Seymour Glass" applied one aspect of Zen archery -- aiming by deliberately not taking aim -- to playing the children's game of marbles. Excerpt from

Seymour: An Introduction

by J.D. Salinger

The New Yorker, June 6, 1959

Boston: Little, Brown, 1963As I've said, he could be spectacularly good at certain games, too. Unpardonably so, in fact. By that I mean there is a degree of excellence in games or sports that we especially resent seeing reached by an unorthodox opponent, a categorical 'bastard' of some kind - a Formless Bastard, a Showy Bastard, or just a plain hundred-per-cent American bastard, which, of course, runs the gamut from somebody who uses cheap or inferior equipment against us with great success all the way down the line to a winning contestant who has an unnecessarily happy, good face. Only one of Seymour's crimes, when lie excelled at games, was Formlessness, but it was a major one. I'm thinking of three games especially: stoopball, curb marbles, and pocket pool. (Pool I'll have to discuss another time. It wasn't just a game with its, it was almost a protestant reformation. We shot pool before or after almost every important crisis of our young manhood.) Stoopball, for the information of rural readers, is a ball game played with the support of a flight of brownstone steps or the front of an apartment building. As we played it, a rubber ball was thrown against solve architectural granite fancywork - a popular Manhattan mixture of Greek Ionic and Roman Corinthian molding -along the facade of our apartment house, about waist-high. If the ball rebounded into the street or over to the far sidewalk and wasn't caught on the fly by someone on the opposing team, it counted as an infield hit, as in baseball; if it was caught - and this was more usual than not - the player was counted out. A home run was scored only when the ball sailed just high and hard enough to strike the wall of the building across the street without being caught on the bounce-off. In our day, quite a few balls used to reach the opposite wall on the fly, but very few fast, low, and choice enough so that they couldn't be handled on the fly. Seymour scored a home run nearly every time he was up. When other boys on the block scored one, it was generally regarded as a fluke - pleasant or unpleasant, depending on whose team you were on - but Seymour's failures to get home runs looked like. flukes. Still more singular, and rather more to the point of this discussion, lie threw the ball like no one else in the neighborhood. The rest of us, if we were normally right-handed, as he was, stood a little to the left of the ripply striking surfaces and let fly with a hard sidearm motion. Seymour faced the crucial area and threw straight down at it - a motion very like his unsightly and abominably unsuccessful overhand smash at ping-pang or tennis - and the ball zoomed back over his head, with a minimum of ducking on his part, straight for the bleachers, as it were. If you tried doing it his way (whether in private or under his positively zealous personal instruction), either you made an easy out or the (goddam) ball flew back and stung you in the face. There came a tine when no one on the block would play stoopball with him - not even myself. Very often, then, lie either spent some tine explaining the. fine points of the game to one of our sisters or turned it into an exceedingly effective game of solitaire, with the rebound from the opposite building lining back to him in such a way that he didn't have to change his footing to catch it on the trickle-in. (Yes, yes, I'm making too damned much of this, but I find the whole business irresistible, after nearly thirty years.) He was the same kind of heller at curb marbles. In curb marbles, the first player rolls or pitches his marble, his shooter, twenty or twenty-five feet along the edge of a side street where there are no cars parked, keeping his marble quite close to the curb. The second player then tries to hit it, shooting from the same starting line. It was rarely done, since almost anything could deflect a marble from going straight to its mark: the unsmooth street itself, a bad bounce against the curb, a wad of chewing gum, any one of a hundred typical New York side-street droppings - not to mention just plain, everyday lousy aim. If the second player missed with his first shot, his marble usually came to rest in a very vulnerable, close position for the first player to shoot at on his second turn. Eighty or ninety times out of a hundred, at this game, whether he shot first or last, Seymour was unbeatable. On long shots, he curved his marble at yours in a rather wide arc, like a bowling shot from the far-right side of the foul line. Here, too, his stance, his forth, was maddeningly irregular. Where everybody else on the block made his long shot with an underhand toss, Seymour dispatched his marble with a sidearm - or, rather, a sidewrist - flick, vaguely like someone scaling a flat stone over a pond. And again imitation was disastrous. To do it his way was to lose all chance of any effective control over the marble.

I think a part of my mind has been vulgarly laying for this next bit. I haven't thought of it in years and years.

One late afternoon, at that faintly soupy quarter of an hour in New York when the street lights have just been turned on and the parking lights of cars are just getting turned on - some on, some still off- I was playing curb marbles with a boy named Ira Yankauer, on the farther side of the side street just opposite the canvas canopy of our apartment house. I was eight. I was using Seymour's technique, or trying to - his side flick, his way of widely curving his marble at the other guy's - and I was losing steadily. Steadily but painlessly. For it was the time of day when New York City boys are much like Tiffin, Ohio, boys who hear a distant train whistle just as the last cow is being driven into the barn. At that magic quarter hour, if you lose marbles, you lose just marbles. Ira, too, I think, was properly time-suspended, and if so, all he could have been winning was marbles. Out of this quietness, and entirely in key with it, Seymour called to me. It came as a pleasant shock that there was a third person in the universe, and to this feeling was added the justness of its being Seymour. I turned around, totally, and I suspect Ira must have, too. The bulby bright lights had just gone on under the canopy of our house. Seymour was standing on the curb edge before it, facing us, balanced on his arches, his hands in the slash pockets of his sheep-lined coat. With the canopy lights behind him, his face was shadowed, dimmed out. He was ten. From the way he was balanced on the curb edge, from the position of his hands, from - well, the quantity x itself, I knew as well then as I know now that he was immensely conscious himself of the magic hour of the day. 'Could you try not aiming so much?' he asked me, still standing there. 'If you hit him when you aim, it'll just be luck.' He was speaking, communicating, and yet not breaking the spell. I then broke it. Quite deliberately. 'How can it be luck if I aim ?' I said back to him, not loud (despite the italics) but with rather more irritation in my voice than I was actually feeling. He didn't say anything for a moment but simply stood balanced on the curb, looking at me, I knew imperfectly, with love. 'Because it will be,' he said. 'You'll be glad if you hit his marble - Ira's marble - won't you? Won't you be glad ? And if you're glad when you hit somebody's marble, then you sort of secretly didn't expect too much to do it. So there'd have to be some luck in it, there'd have to be slightly quite a lot of ac cident in it.' He stepped down off the curb, his hands still in the slash pockets of his coat, and came over to us. But a thinking Seymour didn't cross a twilit street quickly, or surely didn't seem to. In that light, he came toward us much like a sailboat. Pride, on the other hand, is one of the fastest-moving things in this world, and before he got within five feet of us, I said hurriedly to Ira, 'It's getting dark anyway,' effectively breaking tip the game.

Hova mennek télen a kacsák?

Barna Imre: Hova mennek télen a kacsák?

http://www.europakiado.hu/Content/Media/Salinger_kisfuzet.pdf

Salinger forrása Holden Caulfield koanjához:Paj-csang Huaj-haj mondásaiból

Fordította: Terebess Gábor

Folyik a híd, Officina Nova, Budapest, 1990, 53. oldalAlighogy sétára indultak, mester és tanítványa, vadludak szálltak el a fejük felett.

– Mik ezek? – kérdezte Ma-cu.

– Vadludak – nézett föl Paj-csang.

– Merre szállnak?

– Már elszálltak!

Ma-cu megragadta és úgy megcsavarta Paj-csang orrát, hogy tanítványa felüvöltött kínjában.

– Hogy szálltak volna el?! – harsogott Ma-cu.

Paj-csang feleszmélt.

J. D. Salinger

Magasabbra a tetőt, ácsok

Fordította: Lengyel Péter

Mrs. Feddert láthatóan napokon át gyötörte egy vacsora közben tett megjegyzésem, hogy döglött macska szeretnék lenni. A múlt héten megkérdezte tőlem vacsora közben, hogy mihez szándékozom kezdeni, ha leszerelek. Ugyanabban az iskolában akarok-e tanítani továbbra is? Visszatérek-e egyáltalán a tanári pályára? Gondoltam-e arra, hogy visszamenjek a rádióhoz, esetleg valamiféle „kommentátor”-ként? Azt feleltem, hogy ahogy én látom, ez a háború örökké eltarthat, s biztos csak abban az egyben vagyok, hogy ha valaha még egyszer béke lesz, én döglött macska szeretnék lenni. Mrs. Fedder azt hitte, hogy valami viccet mondtam el. Valami túlfinomultnak tart. Halálosan komoly megjegyzésemet olyanfajta szellemességnek vélte, amelyet könnyed, dallamos kis nevetéssel szokás nyugtázni. Azt hiszem, a nevetése megzavart egy kicsit, és elfelejtettem megmagyarázni neki a dolgot. Ma este elmondtam Murielnek, hogy a Zen-buddhizmusban megkérdeztek egyszer egy mestert [Cao-san], mi a legértékesebb dolog a világon, s a mester azt válaszolta, hogy egy döglött macska, mert annak senki sem tudja megadni az árát.

„Tudod, hogyan szól két tenyér, ha csattan.

Vajon miként szól egy tenyér, ha csattan?”ZEN KOAN

J. D. Salinger: KILENC TÖRTÉNET

A kötet mottóját Bartos Tibor fordította

J. D. Salinger

Seymour: Bemutatás

Tandori Dezső fordítása

(részlet)Mint már említettem, Seymour bizonyos játékokban meglepően jó volt. Hozzá kellene tennem: néha megbocsáthatatlanul jó. Mit is akarok mondani ezzel: azt, hogy van a sportban és a játékban a tökéletességnek egy olyan foka, melytől mindig dühbe jövünk, ha azt nem igazi ellenfél produkálja, valamiféle tőrőlmetszett alak, nevezetesen egy stílustalan alak, egy felvágós alak, vagy egész egyszerűen egy százszázalékosan amerikai alak; s ebbe a felsorolásba a lehetséges ellenfelek egészszéles skálája beletartozik, kezdve azokon, akik olcsó és meglehetősen nyavalyás eszközökkel győznek ellenünk, egészen azokig, akik teljesen felesleges módon még boldogságot sugárzón, kimondottan jóképűen néznek szembe velünk. Seymour stílustalansága a különféle játékokban kétségtelenül csak egyik bűne volt; annyi azonban bizonyos, hogy az egyik fő bűne. Különösen három játékra gondolok itt: stoopball- ra, golyózásra és rexezésre. (A rexezésről majd egyszer külön kell írnom. Ez ugyanis már-már nem is játékszámbament nálunk, majdhogynem ez volt maga a reformáció. Serdülő- és kamaszkorunk majdnem minden nagyobb válsága előtt vagy után rexeztünk.) Vidéki olvasók tájékoztatására: a stoopball olyan játék, melynél okvetlenül valami nagy kőlépcsőre vagy házfalra van szükség. Úgy játszottuk, hogy egy-egy gumilabdát valamelyik ház falához, illetve homlokzatához vágtunk – a Manhattanben divatos görög-ióni vagy római-korinthoszi homlokzatokhoz –, méghozzá csípőmagasságan. Ha a labda úgy vágódott vissza az úttestre vagy a szemközti járdára, hogy közben az ellenfél csapatából senki nem tudta elcsípni, az jó pontot jelentett a labdát megjátszó csapat számára, oly módon, mint a baseballnál; ha viszont elcsípték a labdát – és általában ez volt a természetes –, a játékosnak, aki dobta, ki kellett állnia. A legértékesebbnek azonban az a dobás számított, amikor a labda éppen eléggé magasan és erősen szállt ahhoz, hogy a szemközti falra verődjön, anélkül, hogy közben leszednék. A mi időnkben sok olyan labda repült, mely elérte a szemközti falat, de csak nagyon kevésszer sikerült olyan gyorsan, alacsonyan és ügyesen dobni, hogy le ne szedhesse az ellenfél. Seymour viszont, ha játszott, majdnem minden alkalommal szerzett ilyen pontot. Ha mások szereztek, többnyire mázlinak tartották – hogy ezenfelül örvendetesnek-e, vagy sem, ez már mindig attól függött, melyik csapatba tartozott az illető –, Seymournál azonban az volt a mázli, ha nem szerzett ilyen pontot. Ami ennél még jobban idevág: úgy tudta hajítani a labdát, olyan technikával, ahogy rajta kívül senki más a környéken. Mi többiek, akik általában, ugyanúgy, mint ő, jobbkezesek voltunk, egy kicsit balra húzódtunk a falra rajzolt kockás célfelülethez képest, és karunk gyors oldalmozdulatával hajítottuk el a labdát. Seymour azonban egyenesen a célsíkkal szemben helyezkedett el dobás előtt, és egyenesen rá dobott – olyasféle mozdulattal, ami nagyon emlékeztetett pingpongbeli csúnya és teljességgel eredménytelen lecsapásaira –, és azután anélkül, hogy különösebben le kellett volna hajolnia, elzúgott a feje felett a labda, hogy úgy mondjam, a kiadó helyekre. Ha az ember megpróbálkozott vele, hogy ugyanúgy csinálja, mint ő (akár titokban, akár csakugyan az ő fanatikus személyes utasítására), vagy mindjárt kiesett az ember, vagy a nyavalyás labda úgy jött vissza, hogy egyenesen az ember képébe vágódott. Eljött az az idő, amikor senki nem akart vele stoopball- t játszani az egész környéken, én sem. És akkor nagyon gyakran azzal töltötte az idejét, hogy vagy a húgainak magyarázta a játék fogásait, vagy pedig egymaga játszott, amikor is a labda a mögötte levő falról úgy pattant vissza mindig, hogy éppen csak ki kellett nyúlnia érte, és elkapta anélkül, hogy egy tapodtat is elmozdult volna egy álltó helyéből. (Igen, igen, nagyon belemegyek itt a részletekbe, de harminc év után egyszerűen nem tudok ellenállni a dolognak.) Golyózásnál ugyanilyen elképesztő volt, amit csinált. Golyózásnál az első játékos elgurítja vagy ellöki a golyóját hat vagy hét méterre a csatornába, lehetőleg minél szorosabban a járda pereme mellett (természetesen olyan mellékutcában, ahol nem nagyon parkolnak autók). A másik azután megpróbálja eltalálni a magáéval, miközben ugyanarról a kiindulópontról lök. Ez ritkán sikerül, hiszen majdnem mindig akad valami, ami kitéríti a golyót eredeti útjából: az úttest egyenetlen felszíne, vagy ha a játékos ügyetlenül löki neki a golyót a járdaszegélynek, egy darab rágógumi, bármi a sok-sok száz elhajigált apróságból, ami New York mellékutcáit jellemzi – nem is szólva arról, hogy lehet már eleve rosszul célozni is. Ha viszont a második játékos lövése mellément, golyója általában igen kedvezőtlen helyzetbe kerül, az első játékos nagyon könnyen eltalálhatja most már az ő golyójával. Százból nyolcvan vagy kilencven esetben Seymour verhetetlennek bizonyult ebben a játékban, akár elsőnek lökött, akár másodiknak. Nagy távolságok esetében széles ívben lökte ki golyóját, olyasféleképpen, mint a bowling- nál, ha a büntetőterület külső jobb sarkáról kerül sor dobásra. Ebben a játékban is kitűnt azonban, mennyire eltér egész tartása, stílusa a szokásostól, az igazitól. Míg a környéken mindenki a kezével, az ujjai irányításával lökött „hosszút”, Seymour karjának – helyesebben, csuklójának – valami oldalmozgásával indította el a golyót, olyasféle mozdulattal, mint ahogy egy lapos követ dobunk el, mellyel azt akarjuk, hogy kacsázzon a vízen. És itt is teljesen reménytelen vállalkozás volt, ha valaki megpróbálta utánozni őt. Mihelyt az ő módszerével próbáltunk lökni, végképp elvesztettük uralmunkat a golyó felett.

Arra, ami most jön, azt hiszem, tudatom megfelelő része szabályosan – és eléggé csúnyán – lesett. Évek óta nem is gondoltam tudniillik az egészre.

Egy napon késő délután, a délutánnak abban az időszakában, amikor New Yorkban kigyulladnak az utcai lámpák, s amikor az autók lámpái is kezdenek felfényleni – egyesek már világítanak, mások még nem –, a házunkkal szemben nyíló mellékutca csendesebbik részén golyóztam egy Ira Yankauer nevezetű fiúval. Nyolcéves voltam. Seymour technikáját próbáltam alkalmazni, újra meg újra kísérleteztem vele – ezzel az oldalról kacsázva lökéssel, ahogy ő, széles ívben próbáltam rávinni golyómat ellenfelemére –, és újra meg újra veszítettem. Egyhuzamban, de különösebb szívfájdalom nélkül. Mert, mint már mondtam, ez volt a délutánnak éppen az az órája, amikor a New York-i fiúk ugyanolyanok, mint a tiffiniek, ohióiak, akik – miközben a legutolsó tehén is eltűnik az istállóajtóban – távoli vonatfüttyöt hallanak az alkonyatban. És ha valaki ebben a bűvös negyedórányi időben elveszíti a golyóit, hát elveszíti, nagy baj nem történik. Azt hiszem, Ira is ugyanígy kívül állt az időn, és ha ő nyert, ő sem nyert egyebet, mint éppen csak golyókat. És ebben a csendben, mondhatnám teljes összhangban ezzel a csenddel, egyszer csak Seymour szólított. Megijedtem, de ez nagyon kellemes fajtarémület volt, nevezetesen, hogy él még rajtam kívül egy ember a világmindenségben, s ehhez az érzéshez még csak hozzájárult az a helyeslét, hogy ez az ember pont Seymour. Megfordultam, szinte megpördültem, és azt hiszem, Ira ugyanígy. A házunkkal szemben húzódó árkádsor alatt éppen kigyulladtak a fények. Seymour pedig ott állt a járda szélén, velünk szemközt, a túlsó oldalon, az úttest szegélyén egyensúlyozott, kezét bélelt báránybőr kabátjának zsebébe dugva. Mivel a fények mind mögötte gyúltak ki, arca árnyékban volt, mintha elúszott volna az alkonyattal. Tízéves volt. Ahogy ott egyensúlyozott a járda szélén, ahogy a kezét tartotta, ahogy – nos, benne volt az egész X-tényező, és akkor is tudtam, és most is tudom, hogy ő is teljességgel tudatában volt a kivételes pillanatnak. – Nem próbálnád meg, hogy ne célozz annyira? – kérdezte tőlem, még mindig onnan a járda széléről. – Mert ha célzol és találsz, az csak véletlen. – Megszólított, de szavai nem törték meg a varázst. – Hogy lenne véletlen, ha célzok? – feleltem én (bár itt most kurzívval írom) egyáltalán nem hangosan, de azért ott rezgett valami irritáltság is a hangomban, és éreztem is. Ő egy pillanatig nem felelt, csak ott állt a járda szegélyén himbálózva, és – legalábbis úgy éreztem – szeretettel nézett. – Mivel – mondta –, ugye, örülnél, ha a golyóját, Ira golyóját, eltalálnád, vagy nem? Ugye, örülnél? És ha már örülsz, hogy eltalálsz egy golyót, hát akkor nem nagyon számíthattál rá, hogy csakugyan eltalálod. Kell mégis valami szerencse a dologhoz, kell egy kis véletlen mindenképpen. – Kezét még mindig kabátja ferde vágású zsebében tartva, lelépett a járdaszegélyről, és odajött hozzánk. Egy gondolataiba mélyedt Seymour azonban nem jöhetett át gyorsan az úttesten, az al konyatba hajló utcán, legalábbis nem úgy festett a dolog. Ebben az alkonyi fényben inkább mintha csak úgy vitorlázott volna felénk. A büszkeség azonban az egyik leghirtelenebb érzés a világon, nem tűr haladékot; így hát mielőtt Seymour még úgy két méterre lett volna tőlünk, gyorsan azt mondtam Irának: – Sötétedik – és ezzel hatásos módon véget vetettem a játéknak.

Elbert János: Salinger

Nagyvilág, 1964 / 9. szám, 1381-1386. oldal

Akik az írás mögött az irodalmat keresik, azoknak egy-egy új elbeszélés, egy-egy új könyv felfedezésén érzett örömét mindig kikezdi a kérdés: ki az író, milyen az életmű, elég hű-e a kép, amelyet róla rajzoltunk magunknak. A „Zabhegyező” megismerése után J. D. Salingerről mostanában jogosan kérdez az olvasói kíváncsiság. Vajon a negyvenöt éves, mintegy huszonöt esztendeje publikáló szerzőről eleget tudunk-e a regény és a magyarul is elolvasható nem egészen féltucatnyi novella nyomán? Nos, képünk nem szegényes, az amerikai olvasóé sem sokszorosa a mienknek. Salinger ritkán jelentkező elbeszélő, aki egész terméséből, harminckét elbeszéléséből, még a felét sem tartotta kötetbe foglalásra alkalmasnak. 1948 előtt közölt írásai hazájában is csupán régi hetilapokat is forgató irodalomtörténészek csemegéi (bár a Szovjetunióban, ahol Salinger otthoni népszerűsége mellett talán a legnagyobb sikerét aratta, még ezek közül is átmentettek egyet nemrégiben egy százezer példányos kötetbe.) A „Zabhegyező”-n kívül könyvbe foglalva mindössze 1948-tól 1953-ig közölt kilenc elbeszélését adta ki Salinger („Nine Stories”) valamint egy készülő ciklus négy darabját két kötetre osztva „Franny and Zooey” illetve „Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters” — „Seymour: An Introduction” (Magasra a tetőt, ácsok — Bevezetés Seymourról) címmel. 1959 júniusa óta Salinger egy sort sem publikált.

A népszerű író ritka jelentkezése még jobban fokozza a „Salinger-mítoszt” az amerikai irodalomban. A Salinger tollából megjelenő írások ritkasága párosul a

szerzőről megjelentetett tanulmányok sűrűségével — ahogy mondani szokták, az amerikai kritikában külön „Salinger-ipar” működik. Az amerikai irodalom-hisztéria ma már jóformán a film-hisztéria törvényeit követi, és aki a sztár-propagálásnak ebben az általános légkörében elzárkózik a népszerűsítéstől, voltaképpen még rejtelmesebb, izgalmasabb, ravaszabb „publicity”-t teremt magának. Az „amerikai irodalom Greta Garbója”, mondják Salingerről, aki egyetlen, alkalommal adott interjút: egy tizenhat éves diáklánynak, iskolai lapja számára, 1953-ban. A titokzatosság és a kíváncsiság mérkőzése szinte ontja az értesülések tömegét: a lelkes szomszédok még az író magányos vidéki házának várfalszerű kerítését is megmászták, és nagy diadallal fedezték fel a háztól nem messze, a fák között meghúzódó tetőablakos betoncellát: a szerző dolgozószobáját. A közvéleménnyel folytatott macska—egér játék egyébként valósággal szenvedélyévé vált Salingernek, aki gyér önéletrajzi jegyzeteiben sorra helyezi el a hamis nyomok csapdáit. „Westportban élek a kutyámmal” — írja együk könyvének „fülén”. A rövid mondat mindkét adata hamis, vagy méginkább: karikatúra a szabályos „művészéletet” élő kollégákról, kik az amerikai írók híres „alkotótelepét” választották lakhelyül. (Hogy az efféle csapda nem mindig marad hatástalan, azt jól mutatja a „Zabhegyező” magyar kiadása, ahol az adat belekerült az író rövidre fogott jellemzésébe.)Salinger nemcsak az interjúkat kerüli — ironikusan lenézi a műveket kísérő életrajzokat is: „Engem például nem nagyon érdekel, hogy egy regény szerzőjét mikor tartóztatták le ágyúcsempészésért az ír szabadságharcban”. Mégsem kerülhette el, hogy szorgos irodalomtörténészek ne rekonstruálják vonásig pontos biográfiáját. Jerome David Salinger 1919-ben született New York-ban, jómódú polgári családban, édesapja hús-importőr volt. Tizenöt éves korában szülei a Valley Forge Military Academy elnevezésű iskolába küldték (amelyben a hozzáértők jól felismerik a Zabhegyező „Peney”-jének modelljét). Az iskola elvégzése után édesapjával Bécsbe, majd Bydgoszczba ment, hogy beletanuljon a „lengyel sonkaszállítás’' szakmai titkaiba s — mint egyik feljegyzésében írja — hosszú hónapokig „sertéseket vagonírozott” Lengyelországba. Pedig ekkor már írt, tizenöt éves kora óta — még Valley Forge-ban kezdte: „Zseblámpa fényénél, a takaró alatt”. Amikor hazatér Lengyelországból, a Columbia egyetem novellista-szemináriumán tanul, és 1940-től kezdve a nagy amerikai magazinok közlik elbeszéléseit. 1942-től 1946-ig katona.

1944 június hatodikán, az invázió első óráiban száll partra Normandiában a negyedik gyalogos hadosztály soraiban. Harci feladata Gestapo ügynökök felkutatása, de jeepjében mindig ott az írógép: „Írok, mihelyt találok időt, meg egy üres fedezéket”. (Egyébként Ernest Hemingway haditudósító a fronton találkozott J. D. Salinger törzsőrmesterrel, és nagy megelégedéssel olvasta novelláit.) Amerikába való visszaérkezése után Salinger egy darabig New York-ban él, majd csendes vidéki „búvóhelyet” keresett, hogy befejezze első könyvét.Az író az üres órákban és üres fedezékekben már Holden Caulfield alakját, kalandjait formálta: a rövid regény tíz esztendeig íródott. Az egyik, háború alatt írt elbeszélésben már szó esett bizonyos Vincent Caulfield őrmesterről, „akinek van egy kölyök öccse a hadseregben, azt a fickót egy sereg iskolából kivágták már”, és

1945 karácsonyán már megjelent az első Caulfield fejezet egy hetilapban. 1951-ben jelent meg a regény.A „Zabhegyező”-t egyes szám első személyű elbeszélő alakjának varázsa és az első személyű elbeszélés közvetlensége, szenvedélye, vonzása teszi felejthetetlenné. Holden Caulfieldet kicsapják Pencey-ből, a tizenhat éves fiú három napig ténfereg az iskolában és New York-ban, és egy évvel később eldohogja nekünk a három nap történetét — ennyi a regény. Ténfergés és dohogás: félrevonulás és szembeszegülés, vagy több-e? — lázadás-e? Holden Caulfield undorodik mindattól, amit maga körül lát. Vajon a csömör, az undor általános közérzete diktálja-e szavait vagy pedig a látottak elítélése? Mióta a könyv megjelent, ezen vitatkozik a kritika mindenütt. Az amerikai kritika két végleges álláspontját nem nehéz körvonalazni: „dühös fiatalember”, aki tiltakozik a társadalom és az iskola konformizmusa ellen — vallja a kritikusok egyik része, a másik póluson viszont John Aldridge, a regény egyik sokat idézett támadója így fogalmaz: „Nem akar felnőni, beatnik hüvelyk-matyi, nemcsak egyszerűen visszamaradt gyerek, hanem erkölcsi kelekótya”. A Szovjetunióban, ahol immár négy éves vita folyik a könyv körül, s a regénynek megjelenése óta szinte nem csökkenő sajtója van, ugyancsak eltérőek a vélemények. A Známja kritikusa például Holden magatartását „a gyerekesség hipertrófiájával” jellemzi, Jelisztratova, az angol és amerikai irodalom kitűnő ismerője a Gorkij Világirodalmi Intézet három évvel ezelőtt rendezett vitáján viszont így beszélt a kis Caulfieldról: „Ez a fiú megveti a dollár és az autó kultuszát, szemében gyűlöletes a militarizmus és Hollywood és az önelégült üzletemberek nagyképű farizeuskodása”.

Holden Caulfield lázadó. Azóta már szállóigévé lett jelszavával ő maga úgy fogalmazza meg hadüzenetét: minden ellen van, ami „phony” — ami hamis, nem igazi (a magyar kiadás legtöbbször így fordítja: ami „megjátszott”). Ennek a lázadásnak a „szórásába” aztán belekerül a mai amerikai polgári életnek úgyszólván minden jelensége, anélkül hogy a tizenhat éves Holden elválasztaná: mennyi mindebben a tudatos felismerés a világról és mennyi a rossztól ösztönösen irtózó gyerek-tisztaság. Az író pedig nem lép ki a figura mögül, a könyv virtuóz erénye éppen az azonosulásnak ez a tökélye író és elbeszélő-hős között. Egy magányos, tiszta, érzékeny fiú tragédiáját a hamis kapcsolatokon épülő társadalomban — ezt kínálja Salinger könyve. Ennyit és nem többet. Georgij Vlagyimov, a fiatal szovjet prózaíró találóan mondja ki: „A Holden-regény érdekességét egyáltalán nem az szabja meg, hogy képes-e szerzője választ adni arra a kérdésre: lesz-e hősének elegendő ereje a harcra valaha is... Egyszerre csak, honnan, honnan nem, előterem ez a kamasz, aki ízig-vérig a körülötte levő világ szülötte, és szívettépő kiáltása nyomán egyszeriben más szemmel látjuk ezt a világot: látjuk, hogy az ember nem élhet benne, fulladozik, menekülne.”

Holden Caulfieldnek nincs „pozitív programja” ehhez a lázadáshoz. Program helyett csupán álmai vannak. De hiszen Holden — gyerek. Legféltettebb álma, legkedvesebb vágya, hogy „fogó legyen a rozsban”: megmentse a rozsban játszó gyermekeket, a még tiszta embereket a szakadék szélén. (Nem véletlen, hogy az eredeti cím — The Catcher in the Rye — is erre a helyre utal — kár, hogy a magyar kiadás egy kamaszos cím-ötletért eladja a lényeget: Holden becsületes magatartásának, tiszta törekvéseinek rajzát.)

A regény sok magyar olvasóját — s nem egy kritikusát — tévútra vitte a stílus egyik eszköze — Holden elbeszélésének nyelve. A tizenhat éves diák-kamasz nyelvi kérkedése, stílus-handabandája páncél, amely mögé elrejti a maga érzékenységét. Ez a szöveg — amerikai nyelvészek tanúsága szerint is — „durva”, „profán”, „obsz- cén”, egyik recenzense azt mondja róla, hogy „úgy tűzi gombostűhegyre a trágár szavakat, mintha ritka pillangók volnának”. Az olvasónak azonban túl kell jutnia a szokatlan szavakon való csemegézés vagy berzenkedés ál-élményén. (Szerb Antal azt írta erről a „szokatlanságról” a „Lady Chatterley kedvese” körüli hűhó kapcsán, hogy voltaképpen csak arról van szó, hogy az eddig deszkán látható szavakkal ezúttal papíron találkozunk.) Egyébként amerikai kollégisták egész serege bizonyítja, hogy Holden nyelve hiteles, autentikusan „kollégiumi”.

A kollégisták egy része elől különben éppen „blaszfémikus” szelleme és stílusa miatt elzárták a könyvet Amerikában. Nemrégiben járta be a sajtót egy fiatal tanárnő esete, aki dorgálást kapott, mert tizenhat éves növendékeinek a tizenhat éves Holdenről beszélt. Salinger azt mondta egy ízben: „nagyon sok fiatal barátom van, és nem szeretném, hogy könyvemet olyan polcra tegyék, ahol éppen ők nem érik el”. De a „Zabhegyező” általában meghódította a kollégiumokat, egy amerikai katolikus hetilap például arról értesít, hogy a jezsuita kollégiumok (!) 1959-es országos tanulmányi versenyén a diákok kilencven százaléka Salinger regényét választotta irodalmi témául. Az amerikai kritika statisztikusai a „Zabhegyező” hatalmas bestseller-sikerének (tíz évvel az első kiadás után még évi negyed millió példány fogyott belőle Amerikában) a titkát egyenesen az amerikai olvasóközönség szerkezetének megváltozásában látják: a régebbi nő-többség helyét kamasz-többség foglalta el.

Salinger nemcsak abban az értelemben apellál „fiatal barátaira”, hogy közönségét keresi bennük. Ennél sokkal többről van szó: „Legtöbbször nagyon fiatal emberekről írok” — mondja. Holden Caulfield lázadásának ábrázolása nem magányos mozzanat az író munkásságában. A gyermeki világ tisztasága a felnőtt világ romlottságával és konformizmusával szemben, a fiatal érzékenység a felnőtt érzéketlenséggel szemben — alaphelyzete Salinger sok elbeszélésének. Az „Alpári történet Esmének szeretettel” X. őrmesterét egy angol kislány tisztasága óvjá meg a lelki összeomlástól a háború vége felé, a nácizmus annyi piszkát kiteregető napokban. A Szovjetunióban nemrég „újra felfedezett” korai Salinger elbeszélés a négerüldözés egyik epizódját mondja el a tiszta gyermekszemek döbbent tekintetén keresztül. A „Ficánka bácsi Connecticutban” című novellában Eloise megfáradt, illúziótlan életével kislányának barátokat teremtő fantáziáját állítja szembe a szerző. Még folytathatnánk a sort.Az 1955-ben megjelentetett „Franny” is a megcsontosodott társadalmi hazugságok elleni fiatal tiltakozás novellája. Frannyben is éppúgy, mint Holden Caulfield-ban, ott lobog a lázadás minden ellen, ami hamis, ami nem igazi, ami megjátszott: „phony”. Csakhogy Franny már „érettebb gyerek”, mint Holden, ő már szeretne magyarázatot is találni mindarra, amit lát. És éppen azért, mert nem tud magyarázatot találni az őt körülvevő kisszerű törtetők egyetemi világának fonákságaira (akiket olyan humánus-ironikus tökéllyel megrajzolva képvisel Lane Coutell) — a mítoszhoz menekül: a „Zarándok útjá”-hoz, a „Jézus-imádsághoz”. (A művek visszhangja olykor gúnyorosan torz: a szinte remegő idegérzékenységgel, nagy lélektani gonddal, sok gondolati finomsággal megírt novella hatalmas sikerében nagy szerepe volt egy furcsa félreértésnek. Az egyetemista és középiskolás lányok levelek tömegével halmozták el Salingert: őket az izgatta, aggasztotta, vajon jól értelmezték-e az elbeszélés néhány mozzanatát — vajon a kezdődő terhesség teszi-e olyan irritáltan érzékennyé Frannyt.)

A „Franny”-t követő hosszabb Salinger elbeszélés, a „Zooey”, a történetet és diáklány hősnőjét egészen új megvilágításban állította az olvasók elé. A Yale-meccset követő hétfőn, Franny családjának New-York-i lakásán vagyunk: ide menekült a felzaklatott idegzetű lány. Nem akármilyen menedék, nem akármilyen család ez. Frannyről megtudjuk, hogy Glass-lány, vagyis annak az erős törzsi szövetségnek a tagja, amelyet Salinger éppen a „Zooey” című novellájától kezdve szervez-épít a társadalomtól megsértett hőseinek menedékeképpen. Holden Caulfield még egyszerűen a kishúgához menekült. Franny menedékét erősebbre tervezi Salinger: a Glass-család társadalom a társadalomban, biztos vár, ahova vissza lehet vonulni a „phony” társadalom rideg értetlensége elől. A Glass-család tulajdonképpen testvérek erős szövetsége (az apa nem is szerepel a történetekben, az anya is csak néhány epizódban bukkan fel), a hét testvér erős összefogásában a felnőtt világba átmentett gyermekkor él tovább. A Glass-család megrajzolása ettől kezdve Salinger munkásságának középpontjába kerül, az író ciklussá növő elbeszéléseiben egy valóságból és fantasztikumból összeszőtt „saga” körvonalai bontakoznak ki. (Amikor a „Zooey”-ban „közzéteszi” a Glass-család névsorát, egyes régebbi novellák váratlanul hozzábogozódnak a ciklushoz. Például a „Ficánka bácsi Connecticutban” Waltjáról megtudjuk, hogy valójában Walt Glass. Vagyis: a polgári élet unalmába belesüppedt Eloise-nak lett volna egy másik útja a színes, érdekes, gyerek-tiszta élet felé — ennek a szimbóluma Walt emléke.) Olyan krónikának ígérkezik ez, mint amilyet Faulkner szerkesztett a déli családok életéből, Yoknapatawpha County történetében, ám a színhely ezúttal New York. (És mint ahogy Faulkner is sokat merít rokonságának történetéből, a Glass-elbeszélésekben is ott vibrál sok önéletrajzi vonás.) Salinger „saga”-jában éppúgy, mint a Faulknerében az amerikai valóság képét valamilyen mítosz fátylán keresztül látjuk. Salingernél ennek a mítosznak központi alakja — egyszer már ő maga is megkérdi: „a szentje?” — Seymour Glass, a legidősebb testvér a hét közül. Ilyenformán az egész ciklus Salinger egyik legszebb elbeszéléséhez, az 1948-ban megjelent „Ideális nap a banánhalakra” című novellájához nyúlik vissza. Az elbeszélés Seymour öngyilkosságát írja le, megjelenésekor úgy értelmezték, hogy egy háborúból idegbajjal visszatért fiatal férfi tragikumát rajzolja, visszatérésének lehetetlenségét mutatja meg a megrázkódtatásokból semmit át nem élő társadalomba. A Glass-ciklus felépülésével a régi novella jelentése megváltozik: a Glass-fiúnak nincs helye az átlagos amerikai társadalomban — házasságának szükségszerűen öngyilkosságba kellett torkollania. A hídverés a gyerekkor tisztaságát őrző Glass-család és a romlott, konformista külső társadalom között lehetetlen. (Talán nem véletlenül kérdezte annyi olvasó, hogy Seymour és Holden Caulfield „modellje” nem azonos-e.) Ha a családba való visszahúzódás történetét elmondó „Zooey”-t is ismerjük, akkor világossá válik előttünk, hogy Franny története is a hídverés lehetetlenségének legendája.