ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

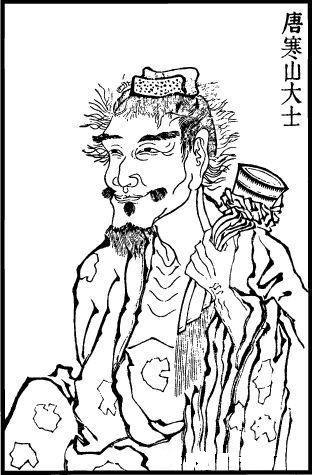

寒山 Hanshan (active 627-649)

(Rōmaji:) Kanzan

(English:) "Cold Mountain"

(Magyar:) Han-san, „Rideg-hegy”

Hanshan shi 寒山詩 (Poems of Hanshan), 2 fascicles. Full title Hanshan shi ji

寒山詩集; also known as the Sanyin ji 三隠集 (Collection of the three recluses).

A collection of the poems of the three semi-legendary hermits Hanshan 寒

山, Shide 拾得, and Fenggan 豊干, who are said to have lived at or around the

temple Guoqing si 國清寺 on Mount Tiantai 天台. It is not known exactly

when Hanshan lived; estimates of his dates range from the seventh to the

ninth centuries. He is said to have written his poems on rocks and walls

around Mount Tiantai; these were later written down by Lü Qiuyin 閭丘胤

(n.d.), the traditional editor of the collection. Fascicle 1 of the text contains

Hanshan's poetry; fascicle 2 contains poems by Shide and Fenggan. There

are several editions of the work, all having a preface by Lü Qiuyin and a

postscript dated 1189 by Zhinan 志南 (n.d.) The earliest extant edition dates

from the Song. The collection is one of the most widely read works in all of

Chan literature.

Tartalom |

Contents |

A bölcs vigyor Han-san

|

Han-shan, Cold Mountain Poems 27 Poems by Han-shan Words from Cold Mountain Three Short Poems by Han-shan Selected Han-Shan Poems for Hippie Reading Han Shan Han Shan Encounters with Cold Mountain Songs of Cold Mountain The Poetry of Han-Shan

PDF: Script and Word in Medieval Vernacular Sinitic Han-shan and Shih-tê Cold Mountain Transcendental Poetry PDF: Han-shan Reader PDF: Cold Mountain: 100 Poems by Han-shan PDF: Cold Mountain Poems PDF: The Complete Cold Mountain: Poems of the Legendary Hermit Hanshan The View from Cold Mountain: Poems of Han-Shan PDF: Moon is Not the Moon: |

Little is known of Han Shan, not even his given name. While his poetry is well known and widely available, his life is shrouded in mystery. The poet was a Zen Buddhist recluse who lived in the Tientai (T'ien-t'ai) Mountains of Danxing (Tang-hsing), China, during the Tang dynasty (618–907); his name

寒山子

Hanshanzi

[Kanzan shi]

means, literally, "The Master of Cold Mountain." Han Shan lived on Cold Mountain with his friend, Shi De (Shih-te). Known for their lighthearted manner, the two men were immortalized in later pictures showing them laughing heartily.

Han Shan's poetry was introduced to China by a Tang government official, Lu Jiuyin (Lu Chiu-Yin), who met the poet while visiting the local Buddhist temple. Han Shan wrote more than 300 poems, which he inscribed onto trees, rocks, and walls. Lu Jiuyin took it upon himself to copy these poems, along with a few poems by Shi De, and collect them in a single volume, collectively known as Hanshan poetry.

Han Shan's poetry is deeply religious. He wrote mainly on Buddhist and Taoist themes, specifically enlightenment, in simple, colloquial language, using conventional Chinese rhyming schemes within the five-character, eight-line verse form. Although his poetry was not groundbreaking, the imagery and spirit of his poems in creating what scholar Burton Watson has called "a landscape of the mind" and his ability to express Buddhist ideals have given Han Shan a place among the finest of Chinese poets.

From: Encyclopedia of World Writers: Beginnings through the 13th Century

寒山拾得 Hanshan & Shide stonerubbing

寒山拾得 Hanshan & Shide stonerubbing

The Story of Han-shan and Shih-te: The first and by far the most famous Ch'an (Zen) eccentrics are Han-shan ("Cold Mountain"; Japanese: Kanzan) and Shih-te ("Foundling"; Japanese: Jittoku). The origins of the legends of Han-shan and his inseparable companion Shih-te can be traced to a collection of about three hundred T'ang poems, known as the Collected Poems of Han-shan. According to the preface, Han-shan was a recluse and poet who lived on Mount T'ien-t'ai (Chekiang, a place renowned for its hermits, both Taoist and Buddhist). He was a friend of the monks Feng-kan and Shih-te of the Kuo-ch'ing-ssu, a monastery near his hermitage. Shih-te, who had been found as a child by Feng-kan (Japanese: Bukan), and who had been brought up in the monastery, worked in the dining hall and kitchen. He supplied his hermit friends with leftovers. Sometimes, the legend says, Han-shan would stroll for hours in the corridors of the monastery, occasionally letting out a cheerful cry, or laughing or talking to himself. When taken to task or driven away by the monks, he would stand still afterwards, laugh, clap his hands, and then disappear. Judging from his poems, which abound with references to the Tao-te-ching and Chuang-tzu, the Taoist classics, Han-shan was actually more of a Taoist recluse than a Ch'an monk.

From: Zen Painting and Calligraphy by J. Fontein and M.L. Hickman

PDF: Wandering Saints : Chan eccentrics in the Art and Culture of Song and Yuan China by Paramita Paul

Thesis/dissertation, Proefschrift Universiteit Leiden. 2009, 310 p.

PDF: A Study on Imitating Activities of Hanshan Poems by Chan Buddhist Monks in Song Dynasty by HUANG Jing-Jia

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, April 2013, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 204-212.

![]() Cold Mountain (Documentary)

Cold Mountain (Documentary)

Director: Mike Hazard & Deb Wallwork | Producer: Mike Hazard | Produced in: 2009 | 28:15

Synopsis: "Cold Mountain" is a film portrait of the Tang Dynasty Chinese poet Han Shan, a.k.a. Cold Mountain. Recorded on location in China, America and Japan, Burton Watson, Red Pine and the legendary Gary Snyder describe the poet's life and tell poems. A trickster, Han Shan wrote poems for everyone, not just the educated elite. A man free of spiritual doctrine, it is unclear whether or not he was a monk, whether he was a Buddhist or a Taoist, or both. It is not even certain he ever lived, but the poems do.

The Complete Poems

项楚 Xiang Chu. 寒山诗注 (附拾得诗注) Cold Mountain Poems and Notes, 中华书局出版 Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing, 1997, 2000, 2010. [313 Cold Mountain Poems, 57 Pick-up Poems, 6 Big-stick Poems]

Chinese text of Hanshan's poems with English vocabulary

https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=604097 Traditional

https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=626573&remap=gb Simplifiedhttps://www.poetrynook.com/poem/%E8%AF%97%E4%B8%89%E7%99%BE%E4%B8%89%E9%A6%96 Traditional / Simplified / Pinyin

Hanshan, The collected songs of Cold Mountain, Translated by Red Pine (Bill Porter). Introduction by John Blofeld. Port Townsend, Washington, Copper Canyon Press, 1983; Revised and expanded edition, 2000. Text in Chinese and English, 272 p.

http://religiondocbox.com/Buddhism/83654123-The-collected-cold-songs-of-mountain.htmlHanshan, The poetry of Han-shan, A Complete, Annotated Translation of Cold Mountain. Translation and commentary by Robert B. Henricks. Suny Series in Buddhist Studies. New York, State University of New York, 1990. 486 p.

PART 1 Poems No. 1— No. 100

PART 2 Poems No. 101— No. 200

PART 3 Poems No. 201— No. 311PDF: The poetry of Hanshan (Cold Mountain), Shide, and Fenggan; edited by Christopher Nugent; translated by Paul Rouzer. Parallel text in Chinese and English.

Boston; Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2017, 403 p.

Open access (OA): https://www.degruyter.com/viewbooktoc/product/449925PDF: The Cold Mountain Master Poetry Collection: Introduction

PDF: Preface to the Poetry Collection of the Cold Mountain Master (Hanshanzi), pp. 1-11.

PDF: Hanshan's Poems, pp. 12-335.PDF: On Cold Mountain: A Buddhist Reading of the Hanshan Poems by Paul Rouzer. University of Washington Press, 2016, 266 p.

The Complete Cold Mountain: Poems of the Legendary Hermit Hanshan, Translated by Kazuaki Tanahashi and Peter Levitt. Text in Chinese and English. Shambala, 2018, 280 p.

Extracts in DOC > PDF (1) > PDF (2)

Hanshan, Le mangeur de brumes, traduction, introduction et notes de Patrick Carré, Paris, éditions Phébus, 1985, 425 p.

http://www.acupuncture-europe.org/textes/hanshan.pdf

Selections

PDF: Cold mountain: 100 poems by the Tang poet Han-shan. Translated by Burton Watson. Grove Press, 1962, 118 p.

PDF: Han-shan Reader

PDF: Cold Mountain Poems: Zen Poems of Han Shan, Shih Te, and Wang Fan-chih, Tr. J.P. Seaton, Shambhala, 2009, 136 p.

Cold Mountain Poems: 25 Poems by Han-shan, interpreted by James Kirkup; calligraphy by Matsumoto Hiroyuki. Kyoto Editions, 1980, 25, 25 p.

[Opposite pages numbered in duplicate. Limited edition: 300 copies printed.]Guffawing in the wilderness: 13 poems by Han Shan; rendered by George Ellison. La Crosse, Wisc. : Juniper Press, 1977. xiii p. [250 copies handset & printed.]

Cold Mountain Transcendental Poetry by the T'ang Zen Poet Han-shan: 100 poems translated by Wanderling Poet, M. A. (Kindle Edition)

[The source for this English translation is 项楚 Xiang Chu. 寒山诗注 (附拾得诗注) Cold Mountain Poems and Notes]The View from Cold Mountain: Poems of Han-Shan and Shih-Te, Tr. by Arthur Tobias, James Sanford and J.P. Seaton;

edited by Dennis Maloney, Buffalo, N.Y.: White Pine Press, 1982, [38] p.PDF: WU Chi-yu 吳其昱 (1915-2011): “A Study of Han-shan”, T'oung pao, Vol. 45 (1957), pp. 392-450.

Of course there are some people who are careful of money,

But not I among them.

Because I dance too much, my garment of thin cloth is worn.

My bottle is empty, for I spurt out the wine when we sing.

Eat a full meal.

Don't tire your feet.

The day when weeds are sprouting through your skull,

You will regret what you have been. (p. 432.)The China Which is Here: Translating Classical Chinese Poetry: A thesis by Lawrence Kwan-chee Yung

at the University of Warwick, May, 1998

Chapter 8. Gary Snyder: The Mountain and the Mind, pp. 209-241.

http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/36378/1/WRAP_THESIS_Yung_1998.pdfA Study on Imitating Activities of Hanshan Poems by Chan Buddhist Monks in SONG Dynasty

http://www.davidpublishing.com/davidpublishing/Upfile/7/12/2013/2013071201173771.pdfSchafer, Edward H. and Eoyang, Eugene, trans. "[Han Shan] Four Untitled Poems"

IN Sunflower Splendor: Three Thousand Years of Chinese Poetry, Indiana University Press, 1990, p. 91.pp. 90-91.Kahn, Paul. "Han Shan in English." Renditions, No. 25, Spring, 1986, pp. 140-175. [Contains complete English bibliography.]

PDF: Stahlberg, Roberta Helmer. The poems of the Han-shan collection, unpublished Ph.D.dissertation. Ohio State University, 1977. 192 p.

https://etd.ohiolink.edu/pg_10?0::NO:10:P10_ACCESSION_NUM:osu1487064731706252Roberta Helmer (1950-2018)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roberta_HelmerHan Shan: Poems from the Cold Mountain

translated from Stephan Schuhmacher's German version with added notes by Georg Mertens

1998 (revised 2002)PDF: Anu Niemi, The making of Zen personage: Hanshan and how it is read. Studia Orientalia 95. Finnish Oriental Society, Vammala 2003, pp. 373-384.

PDF: Talking about food does not appease hunger: Phrases on hunger in Chan (Zen) Buddhist texts

Academic dissertation by Anu Niemi, University of Helsinki, Department of World Cultures, Itä Aasian tutkimus, Helsinki, 2014

Han-shan, Cold Mountain Poems

Translated by

Gary Snyder

EVERGREEN REVIEW, vol. 2, no. 6 (Autumn 1958). pp. 69-80.

COLD MOUNTAIN POEMS: Twenty-Four Poems by Han-Shan. First Edition. Portland, Oregon: Press-22, 1970, [30] p.

RIPRAP & COLD MOUNTAIN POEMS, San Francisco: Four Seasons Foundation, 1969.

pp. 31-61.

In 1953, Gary Snyder returned to the Bay Area and, at age 23, enrolled in graduate school at the University of California, Berkeley, to study Asian languages and culture. He intensified his study of Chinese and Japanese, and taking up the challenge of one of his professors, Chen Shih-hsiang, he began to work on translating a largely unknown poet by the name of Han Shan, a writer with whom the professor thought Snyder might feel a special affinity. The results were magical. As Patrick Murphy noted, "These poems are something more than translations precisely because Snyder renders them as a melding of Han Shan's Chinese Ch'an Buddhist mountain spirit trickster mentality and Snyder's own mountain wilderness meditation and labor activities." The suite of 24 poems was published in the 1958 issue of The Evergreen Review, and the career of one of America's greatest poets was launched.

In 1972, Press-22 issued a beautiful edition of these poems written out by hand in italic by Michael McPherson. We are doing a new augments edition based on the old, with a new design, a preface by Lu Ch'iu-yin, and an afterword by Mr. Snyder where he discusses how he came to this work and what it meant to his development as a writer and Buddhist.

On May 11, 2012, for the Stronach Memorial Lecture at The University of California, more than fifty years after his days there as a student, Snyder offered a public lecture reflecting on Chinese poetry, Han Shan, and his continuing work as a poet and translator. This remarkable occasion was recorded and we are including a CD of it in our edition, making this the most definitive edition of Cold Mountain Poems ever published.

—Cold Mountain Poems by Gary Snyder, Kindle Edition, Counterpoint; Har/Com edition (June 11 2013)

寒山子詩集序

作者: 閭邱允詳夫寒山子者,不知何許人也。自古老見之,皆謂貧人風狂之士,隱居天台唐興縣西七十里,號為寒巖。每於茲地,時還國清寺。寺有拾得,知食堂尋常,收貯餘殘菜滓於竹筒內,寒山若來,即負而去。或長廊徐行,叫喚快活,獨言獨笑,時贈遂促罵打趁,乃駐立撫掌,嗬嗬大笑,良久而去。且狀如貧子,形貌枯悴一言一氣,理合其意。沈而思之,隱況道情,凡所啟言,洞該元默。乃以樺皮為冠,布裘破弊,木屐履地。是故至人遯跡,同類化物。或長廊唱詠,唯言咄哉咄哉。三界輪回,或於邨墅與牧牛子而歌笑。或逆或順,自樂其性。非哲者安可識之矣?

允頃受丹邱薄宦,臨途之日,乃縈頭痛,遂召日者醫治,轉重。乃遇一禪師,名豐干,言從天台山國清寺來,特此相訪乃命救疾。師乃舒容而笑曰:「身居四大,病從幻生。若欲除之,應須淨水。」時乃持淨水上師,師乃噀之,須臾祛殄。乃謂允曰:「台州海島嵐毒,到日必須保護。」允乃問曰:「未審彼地當有何賢,堪為師仰?」師曰:「見之不識,識之不見。若欲見之,不得取相,乃可見之。寒山文殊,遯跡國清;拾得普賢,狀如貧子,又似風狂,或去或來,在國清寺庫院走使廚中著火。」言訖辭去。

允乃進途,到任台州,不忘其事。到任三日後,親往寺院,躬問禪宿,果合師言。乃令勘唐興縣,有寒山拾得是否?時縣申稱,當縣界西七十里內有一巖,巖中古老見有貧士,頻往國清寺止宿。寺庫中有一行者,名曰拾得。允乃特往禮拜。到國清寺,乃問寺眾:「此寺先有豐干禪師院在何處?並拾得、寒山子見在何處?」時僧道翹答曰:「豐干禪師院在經藏後,即今無人住得,每有一虎,時來此吼。寒山、拾得二人見在廚中。」僧引允至豐干禪師院,乃開房唯見虎跡。乃問僧寶德道翹:「禪師在日,有何行業?」僧曰:「豐干在日,唯攻舂米供養,夜乃唱歌自樂。」遂至廚中灶前,見二人向火大笑。允便禮拜,二人連聲喝允,自相把手,嗬嗬大笑叫喚。乃云:「豐干饒舌饒舌,彌陀不識,禮我何為?」僧徒奔集,遞相驚訝,何故尊官禮二貧士?時二人乃把手走出寺,乃令逐之,急走而去,即歸寒巖。允乃重問僧曰:「此二人肯止此寺否?」乃令覓房,喚歸寺安置,允乃歸郡。遂制淨衣二對香藥等,特送供養。時二人更不返寺,使乃就巖送上。而見寒山子,乃高聲唱曰:「賊賊!」退入岩穴。乃云報汝諸人,各各努力,入穴而去,其穴自合,莫可追之。其拾得跡沈無所。

乃令僧道翹尋其往日行狀,唯於竹木石壁書詩,並村墅人家廳壁上所書文句三百餘首,及拾得於土地堂壁上書言偈,並纂集成卷。但允棲心佛理,幸逢道人,乃為讚曰:

「菩薩遁跡,示同貧士。獨居寒山,自樂其志。貌悴形枯,布裘弊止。出言成章,諦實至理。凡人不測,謂風狂子。時來天台,入國清寺。徐步長廊,嗬嗬撫指。或走或立,喃喃獨語。所食廚中,殘飯菜滓。吟偈悲哀,僧俗咄捶。都不動搖,時人自恥。作用自在,凡愚難值。即出一言,頓祛塵累。是故國清,圖寫儀軌,永劫供養,長為弟子。昔居寒山,時來茲地,稽首文殊,寒山之士。南無普賢,拾得定是,聊申讚歎,願超生死。」

Preface to the Poems of Han-shan

by Lu Ch'iu-yin, Governor of T'ai Prefecture

tr. Gary SnyderNo one knows what sort of man Han-shan was. There are old people who knew him: they say he was a poor man, a crazy character. He lived alone seventy Li (23 miles) west of the T'ang-hsing district of T'ien-t'ai at a place called Cold Mountain. He often went down to the Kuo-ch'ing Temple. At the temple lived Shih'te, who ran the dining hall. He sometimes saved leftovers for Han-shan, hiding them in a bamboo tube. Han-shan would come and carry it away; walking the long veranda, calling and shouting happily, talking and laughing to himself. Once the monks followed him, caught him, and made fun of him. He stopped, clapped his hands, and laughed greatly—Ha Ha!—for a spell, then left.

He looked like a tramp. His body and face were old and beat. Yet in every word he breathed was a meaning in line with the subtle principles of things, if only you thought of it deeply. Everything he said had a feeling of Tao in it, profound and arcane secrets. His hat was made of birch bark, his clothes were ragged and worn out, and his shoes were wood. Thus men who have made it hide their tracks: unifying categories and interpenetrating things. On that long veranda calling and singing, in his words of reply Ha Ha!—the three worlds revolve. Sometimes at the villages and farms he laughed and sang with cowherds. Sometimes intractable, sometimes agreeable, his nature was happy of itself. But how could a person without wisdom recognize him?

I once received a position as a petty official at Tan-ch'iu. The day I was to depart, I had a bad headache. I called a doctor, but he couldn't cure me and it turned worse. Then I met a Buddhist Master named Feng-kan, who said he came from the Kuo-ch'ing Temple of T'ien-t'ai especially to visit me. I asked him to rescue me from my illness. He smiled and said, "The four realms are within the body; sickness comes from illusion. If you want to do away with it, you need pure water." Someone brought water to the Master, who spat it on me. In a moment the disease was rooted out. He then said, "There are miasmas in T'ai prefecture, when you get there take care of yourself." I asked him, "Are there any wise men in your area I could look on as Master?" He replied, "When you see him you don't recognize him, when you recognize him you don't see him. If you want to see him, you can't rely on appearances. Then you can see him. Han-shan is a Manjusri (one who has attained enlightenment and, in a future incarnation, will become Buddha) hiding at Kuo-sh'ing. Shih-te is a Samantabbhadra (Bodhisattva of love). They look like poor fellows and act like madmen. Sometimes they go and sometimes they come. They work in the kitchen of the Kuo-ch'ing dining hall, tending the fire." When he was done talking he left.

I proceeded on my journey to my job at T'ai-chou, not forgetting this affair. I arrived three days later, immediately went to a temple, and questioned an old monk. It seemed the Master had been truthful, so I gave orders to see if T'ang-hsing really contained a Han-shan and Shih-te. The District Magistrate reported to me: "In this district, seventy li west, is a mountain. People used to see a poor man heading from the cliffs to stay awhile at Kuo-ch'ing. At the temple dining hall is a similar man named Shih-te." I made a bow, and went to Kuo-ch'ing. I asked some people around the temple, "There used to be a Master named Feng-kan here, Where is his place? And where can Han-shan and Shih-te be seen?" A monk named T'ao-ch'iao spoke up: "Feng-kan the Master lived in back of the library. Nowadays nobody lives there; a tiger often comes and roars. Han-shan and Shih-te are in the kitchen." The monk led me to Feng-kan's yard. Then he opened the gate: all we saw was tiger tracks. I asked the monks Tao-ch'iao and Pao-te, "When Feng-kan was here, what was his job?" The monks said, :He pounded and hulled rice. At night he sang songs to amuse himself." Then we went to the kitchen, before the stoves. Two men were facing the fire, laughing loudly. I made a bow. The two shouted Ho! at me. They struck their hands together—Ha Ha!—great laughter. They shouted. Then they said, "Feng-kan—loose-tounged, loose-tounged. You don't recognize Amitabha, (the Bodhisattva of mercy) why be courteous to us?" The monks gathered round, surprise going through them. ""Why has a big official bowed to a pair of clowns?" The two men grabbed hands and ran out of the temple. I cried, "Catch them"—but they quickly ran away. Han-shan returned to Cold Mountain. I asked the monks, "Would those two men be willing to settle down at this temple?" I ordered them to find a house, and to ask Han-shan and Shih-te to return and live at the temple.

I returned to my district and had two sets of clean clothes made, got some incense and such, and sent it to the temple—but the two men didn't return. So I had it carried up to Cold Mountain. The packer saw Han-shan, who called in a loud voice, "Thief! Thief!" and retreated into a mountain cave. He shouted, "I tell you man, strive hard"—entered the cave and was gone. The cave closed of itself and they weren't able to follow. Shih-te's tracks disappeared completely..

I ordered Tao-ch'iao and the other monks to find out how they had lived, to hunt up the poems written on bamboo, wood, stones, and cliffs—and also to collect those written on the walls of people's houses. There were more than three hundred. On the wall of the Earth-shrine Shih-te had written some gatha (Buddhist verse or song). It was all brought together and made into a book.

I hold to the principle of the Buddha-mind. It is fortunate to meet with men of Tao, so I have made this eulogy.

THE COLD MOUNTAIN POEMS, tr. Gary Snyder

1

可笑寒山道, 而無車馬蹤。 聯谿難記曲, 疊嶂不知重。 泣露千般草, 吟風一樣松。 此時迷徑處, 形問影何從。The path to Han-shan's place is laughable,

A path, but no sign of cart or horse.

Converging gorges—hard to trace their twists

Jumbled cliffs—unbelievably rugged.

A thousand grasses bend with dew,

A hill of pines hums in the wind.

And now I've lost the shortcut home,

Body asking shadow, how do you keep up?2

重巖我卜居, 鳥道絕人迹。 庭際何所有, 白雲抱幽石。 住茲凡幾年, 屢見春冬易。 寄語鐘鼎家, 虛名定無益。

In a tangle of cliffs, I chose a place—

Bird paths, but no trails for me.

What's beyond the yard?

White clouds clinging to vague rocks.

Now I've lived here—how many years—

Again and again, spring and winter pass.

Go tell families with silverware and cars

"What's the use of all that noise and money?"3

山中何太冷, 自古非今年。 沓嶂恆凝雪, 幽林每吐煙。 草生芒種後, 葉落立秋前。 此有沈迷客, 窺窺不見天。

In the mountains it's cold.

Always been cold, not just this year.

Jagged scarps forever snowed in

Woods in the dark ravines spitting mist.

Grass is still sprouting at the end of June,

Leaves begin to fall in early August.

And here I am, high on mountains,

Peering and peering, but I can't even see the sky.4

驅馬度荒城, 荒城動客情。 高低舊雉堞, 大小古墳塋。 自振孤蓬影, 長凝拱木聲。 所嗟皆俗骨, 仙史更無名。

I spur my horse through the wrecked town,

The wrecked town sinks my spirit.

High, low, old parapet walls

Big, small, the aging tombs.

I waggle my shadow, all alone;

Not even the crack of a shrinking coffin is heard.

I pity all those ordinary bones,

In the books of the Immortals they are nameless.5

欲得安身處, 寒山可長保。 微風吹幽松, 近聽聲逾好。 下有斑白人, 喃喃讀黃老。 十年歸不得, 忘却來時道。

I wanted a good place to settle:

Cold Mountain would be safe.

Light wind in a hidden pine—

Listen close—the sound gets better.

Under it a gray haired man

Mumbles along reading Huang and Lao.

For ten years I havn't gone back home

I've even forgotten the way by which I came.6

人問寒山道, 寒山路不通。 夏天冰未釋, 日出霧朦朧。 似我何由屆, 與君心不同。 君心若似我, 還得到其中。

Men ask the way to Cold Mountain

Cold Mountain: there's no through trail.

In summer, ice doesn't melt

The rising sun blurs in swirling fog.

How did I make it?

My heart's not the same as yours.

If your heart was like mine

You'd get it and be right here.7

粵自居寒山, 曾經幾萬載。 任運遯林泉, 棲遲觀自在。 寒巖人不到, 白雲常靉靆。 細草作臥褥, 青天為被蓋。 快活枕石頭, 天地任變改。

I settled at Cold Mountain long ago,

Already it seems like years and years.

Freely drifting, I prowl the woods and streams

And linger watching things themselves.

Men don't get this far into the mountains,

White clouds gather and billow.

Thin grass does for a mattress,

The blue sky makes a good quilt.

Happy with a stone under head

Let heaven and earth go about their changes.8

登陟寒山道, 寒山路不窮。 谿長石磊磊, 澗闊草濛濛。 苔滑非關雨, 松鳴不假風。 誰能超世累, 共坐白雲中。

Clambering up the Cold Mountain path,

The Cold Mountain trail goes on and on:

The long gorge choked with scree and boulders,

The wide creek, the mist blurred grass.

The moss is slippery, though there's been no rain

The pine sings, but there's no wind.

Who can leap the word's ties

And sit with me among the white clouds?9

杳杳寒山道 , 落落冷澗濱。 啾啾常有鳥, 寂寂更無人。 磧磧風吹面, 紛紛雪積身。 朝朝不見日, 歲歲不知春。

Rough and dark—the Cold Mountain trail,

Sharp cobbles—the icy creek bank.

Yammering, chirping—always birds

Bleak, alone, not even a lone hiker.

Whip, whip—the wind slaps my face

Whirled and tumbled—snow piles on my back.

Morning after morning I don't see the sun

Year after year, not a sign of spring.10

一向寒山坐, 淹留三十年。 昨來訪親友, 太半入黃泉。 漸減如殘燭, 長流似逝川。 今朝對孤影, 不覺淚雙懸。

I have lived at Cold Mountain

These thirty long years.

Yesterday I called on friends and family:

More than half had gone to the Yellow Springs.

Slowly consumed, like fire down a candle;

Forever flowing, like a passing river.

Now, morning, I face my lone shadow:

Suddenly my eyes are bleared with tears.11

碧澗泉水清, 寒山月華白。 默知神自明, 觀空境逾寂。

Spring water in the green creek is clear

Moonlight on Cold Mountain is white

Silent knowledge—the spirit is enlightened of itself

Contemplate the void: this world exceeds stillness.12

出生三十年 , 當遊千萬里。 行江青草合, 入塞紅塵起。 鍊藥空求仙, 讀書兼詠史。 今日歸寒山, 枕流兼洗耳。In my first thirty years of life

I roamed hundreds and thousands of miles.

Walked by rivers through deep green grass

Entered cities of boiling red dust.

Tried drugs, but couldn't make Immortal;

Read books and wrote poems on history.

Today I'm back at Cold Mountain:

I'll sleep by the creek and purify my ears.13

鳥語情不堪, 其時臥草庵。 櫻桃紅爍爍, 楊柳正毿毿。 旭日銜青嶂, 晴雲洗淥潭。 誰知出塵俗, 馭上寒山南。

I can't stand these bird songs

Now I'll go rest in my straw shack.

The cherry flowers are scarlet

The willow shoots up feathery.

Morning sun drives over blue peaks

Bright clouds wash green ponds.

Who knows that I'm out of the dusty world

Climbing the southern slope of Cold Mountain?14

寒山多幽奇, 登者皆恆懾。 月照水澄澄, 風吹草獵獵。 凋梅雪作花, 杌木雲充葉。 觸雨轉鮮靈, 非晴不可涉。

Cold Mountain has many hidden wonders,

People who climb here are always getting scared.

When the moon shines, water sparkles clear

When the wind blows, grass swishes and rattles.

On the bare plum, flowers of snow

On the dead stump, leaves of mist.

At the touch of rain it all turns fresh and live

At the wrong season you can't ford the creeks.15

寒山有躶蟲, 身白而頭黑。 手把兩卷書, 一道將一德。 住不安釜竈, 行不齎衣祴。 常持智慧劍, 擬破煩惱賊。

There's a naked bug at Cold Mountain

With a white body and a black head.

His hand holds two book scrolls,

One the Way and one its Power.

His shack's got no pots or oven,

He goes for a long walk with his shirt and pants askew.

But he always carries the sword of wisdom:

He means to cut down sensless craving.16

寒山有一宅, 宅中無闌隔。 六門左右通, 堂中見天碧。 房房虛索索, 東壁打西壁。 其中一物無, 免被人來惜。

寒到燒輭火, 飢來煑菜喫。 不學田舍翁, 廣置牛莊宅。 盡作地獄業, 一入何曾極。 好好善思量, 思量知軌則。

Cold Mountain is a house

Without beams or walls.

The six doors left and right are open

The hall is blue sky.

The rooms all vacant and vague

The east wall beats on the west wall

At the center nothing.

Borrowers don't bother me

In the cold I build a little fire

When I'm hungry I boil up some greens.

I've got no use for the kulak

With his big barn and pasture —

He just sets up a prison for himself.

Once in he can't get out.

Think it over —

You know it might happen to you.17

一自遯寒山, 養命餐山果。 平生何所憂, 此世隨緣過。 日月如逝川, 光陰石中火。 任你天地移, 我暢巖中坐。

If I hide out at Cold Mountain

Living off mountain plants and berries—

All my lifetime, why worry?

One follows his karma through.

Days and months slip by like water,

Time is like sparks knocked off flint.

Go ahead and let the world change—

I'm happy to sit among these cliffs.18

多少天台人, 不識寒山子。 莫知真意度, 喚作閑言語。

Most T'ien-t'ai men

Don't know Han-shan

Don't know his real thought

And call it silly talk.19

一住寒山萬事休, 更無雜念挂心頭。 閑書石壁題詩句, 任運還同不繫舟。

Once at Cold Mountain, troubles cease—

No more tangled, hung up mind.

I idly scribble poems on the rock cliff,

Taking whatever comes, like a drifting boat.20

客難寒山子, 君詩無道理。 吾觀乎古人, 貧賤不為恥。 應之笑此言, 談何疏闊矣。 願君似今日, 錢是急事爾。

Some critic tried to put me down—

"Your poems lack the Basic Truth of Tao."

And I recall the old timers

Who were poor and didn't care.

I have to laugh at him,

He misses the point entirely,

Men like that

Ought to stick to making money.21

久住寒山凡幾秋, 獨吟歌曲絕無憂。 飢餐一粒伽陀藥, 心地調和倚石頭。

I've lived at Cold Mountain—how many autumns.

Alone, I hum a song—utterly without regret.

Hungry, I eat one grain of Immortal medicine

Mind solid and sharp; leaning on a stone.22

寒山頂上月輪孤, 照見晴空一物無。 可貴天然無價寶, 埋在五陰溺身軀。

On top of Cold Mountain the lone round moon

Lights the whole clear cloudless sky.

Honor this priceless natural treasure

Concealed in five shadows, sunk deep in the flesh.23

我家本住在寒山, 石巖棲息離煩緣。 泯時萬象無痕跡, 舒處周流遍大千。 光影騰輝照心地, 無有一法當現前。 方知摩尼一顆珠, 解用無方處處圓。

My home was at Cold Mountain from the start,

Rambling among the hills, far from trouble.Gone, and a million things leave no trace

Loosed, and it flows through galaxies

A fountain of light, into the very mind—

Not a thing, and yet it appears before me:

Now I know the pearl of the Buddha nature

Know its use: a boundless perfect sphere.24

時人見寒山, 各謂是風顛。 貌不起人目, 身唯布裘纏。 我語他不會, 他語我不言。 為報往來者,可來向寒山。

When men see Han-shan

They all say he's crazy

And not much to look at—

Dressed in rags and hides.

They don't get what I say

And I don't talk their language.

All I can say to those I meet:

"Try and make it to Cold Mountain."

Cold Mountain Poems and Persons

PART ONE

I made my way back to UC Berkeley driving an elderly Packard I had borrowed from my father – after working all summer on trails in the High Sierra – in September of 1955. Some of the labor on trails from that time is reflected in my first book of poems, Riprap. What happened next was a life-turning moment – my professor Dr. CHEN Shih-hsiang asked me what I wanted to focus on for his Chinese Poetics seminar. I said, “Maybe a Buddhist poet.” He said, “I have somebody just right for you: the name is Han-shan, ‘Cold Mountain’ – take it out from the East Asian Library.” It was a book in the traditional-style sewn binding, the complete poems.

For the whole fall – only two other graduate students in the whole class, one of whom was Asian – we all worked at reading, translating, and interpreting our chosen texts. We would discuss our work in the room, and Chen very helpfully steered me and critiqued what I was doing with the material. At the end of the academic semester I had gone through 24 poems and had also looked up the 27 translations by Arthur Waley that had been published in Encounter magazine a few years earlier. I had no idea of publishing my own work back then.

I showed my set of tentative translations to Alan Watts, who was a founder and teacher at the Academy of Asian Studies in San Francisco and whom I had gotten to know – more on the basis of my calligraphy (in a letter I wrote to him) than my interest in Zen. (I had studied with the master calligrapher Lloyd Reynolds and several of his key art students while at Reed, and had learned to appreciate and clumsily write Chancery Cursive.)

Watts invited me to come to a class at the Academy one evening and read my translations to his students. It got an extremely nice response from everybody including Alan. Only a few months later the critic and editor Donald Allen (who moved in the same circles) asked me about publishing them in an upcoming issue of Evergreen Review magazine. They were published in the autumn of 1958.

I moved to Japan in May 1956. From the beginning I took further lessons in modern Japanese language and began formal Rinzai Zen study. Ruth Fuller Sasaki, a Zen priest at Daitoku-ji, read my translations in manuscript and thought they were passable; Dr. IRIYA Yoshitaka of Kyoto University (who was the chair of the Rinzai-roku or Linji-lu translation group at the research center run by Mrs. Sasaki) also read and liked them. Dr. Iriya published a volume of Han-shan – Kanzan in Japanese – into both literary and colloquial language: number 5 in the Chugokushijin Zenshu series (Iwanami Shoten) in 1958. Burton Watson, also a member of the translation group (and working on his dissertation for Columbia), was acquainted with the Arthur Waley translations. He’d read mine in manuscript and said they were acceptable. He suggested several small but potent revisions.

In my Berkeley innocence I had thought nobody read this obscure text, but it turned out that Japanese literati and Buddhist scholars knew the work well. Dr. Watson drew on Dr. Iriya’s volume for his fine English language translations of a hundred poems published by Grove Press in 1962.

Many other Han-shan translations appeared in subsequent years including two different books of the complete corpus (311 poems) – one by Red Pine (Bill Porter), and the other a pedestrian but useful annotated text by Dr. Robert Henricks.

In 1964 I was back on the West Coast for a year and was employed by the English department at UC Berkeley as a replacement instructor for Thom Gunn, who was on sabbatical. Dr. Cyril Birch was teaching in the East Asian Languages Department at that time. He asked me if he could include my translations of the Han-shan poems in an anthology he was editing – a new gathering of literary Chinese poetry in English translation – and I said yes. When I asked him why (seeing as how there were a number of other choices by this time), he answered that he liked their natural and colloquial tone.

That anthology, according to Dr. CHUNG Ling, is the one that made Han-shan’s work famous, first nationwide and then, because the anthology got to Europe, worldwide.

Dr. Chung’s conclusion was that the surprising international fame of Han-shan (surprising to the Chinese literary critics and historians who never included Han-shan in the official canon) was due to the inclusion of the poems in the Birch anthology. It came out in 1965.

My literary notoriety in China, which is surprising, is to a certain extent built upon a fascination with this Han-shan story. Also I am identified by many with the Beat Generation, a phenomenon that is still revered in much of the non-English-speaking world.

Though I was friends with some of the leading American literary actors of that time I never thought of my own writings as being in their camp. “Vernacular” as the language of poetry, open to all – and any intrusions of archaic or foreign or technical language you may need, as well – has been accepted as part of valid poetic strategy for decades. I had been a mountaineer and forestry laborer as well as a bookish scholar for several years already, and simply could draw on a wide experience of events and words and observations in finding ways to represent the Han-shan imagery. I also regularly made a practice of internalizing and visualizing the taste of the whole scene – cold, wet, rocky, lonely, or whatever was called for – to the point that I could write it out with some sense of presence. This doesn’t always work by any means, but it is exciting when it does. It reaches across time and space.

PART TWO

In Standard Chinese “Cold Mountain” is pronounced “Han-shan.” In Japanese, or more properly in “Sino-Japanese” (because there are thousands of words in that language that were never borrowed from Chinese writings), it is pronounced “Kanzan.” The Zen Buddhists of China and Japan really took to this semi-mythical personage and soon enough, there were lively portraits of him and his friends.

In later centuries much of Chinese Buddhism developed into something like a single sect, each large temple complex offering the choice of halls dedicated to devotional practices, textual scholarship, or organized meditation practices. The same was true in Korea.

In Japan, where devotional Buddhism and wisdom-oriented Buddhism stayed on separate tracks, the Zen tradition managed with considerable skill to walk a path that was ragged and carefree but simultaneously meticulous and high-status. The Zen paintings mostly reflected the skill and freedom; the elaborate ceremonies and elegant manners demonstrated the attention to forms. At the heart of it all was the Zen training hall where the young monks lived in both summer heat and winter cold, a bit hungry and short on sleep, for several years. They were continually being thrown into untenable situations one after another (called “koans”). It was and still is the perfect balance of freedom and necessity. Kanzan is a kind of human icon of this life; the myth-figure who represents it is Fudo Myo-O, the funny, fierce, almost demonic character who lurks off to the side in many temples, surrounded by rocks and flames.

The Japanese Zen world made good use of the Han-shan text – it must have gotten there early – and there is a history of formal Zen lectures being given by Zen teachers over the centuries on the poems. It would be a mistake to assume there was no interest in the Zen aspects of Han-shan in China, too – though the putative author’s reputation and place in China was that of a sort of eccentric, and not much as a formal poet.

I noted earlier that my small selection of poems was picked up worldwide because of the Birch anthology. But that’s only part of the story. Like the Beat Generation (and perhaps for similar reasons), European, South African, South American, and some North American readers responded enthusiastically to those poems – men and women alike, all walks of life – because of what comes down to the deep and genuine Daoist-Buddhist message they carry.

At least for non–East Asians, they touch us not because of the invocation of a hermetic ideal or solitary asceticism, but because of the almost joyful rejection of materialism and the absolute pleasure in being in the great world “with a sky for a blanket,” aware of living a life apart from the value-assumptions of mainstream people. I have heard from readers all over the world who said how mysteriously that spoke to them even as they were following their own path in life (everybody had a job of some sort, too). There is a deep strain of non-ideological dubiousness about the large materialistic goals that are the official “dream” of developed-world people and certain others worldwide.

Plus, the invocation of the natural world is truly moving. Grasses, flowers, running water in the streams, stream beds, pines in the wind, rising clouds, rain and dew – all these phenomena that are not in fact just of the “mountain” are beautifully evoked. “I’ll sleep by the creek and wash my ears” – something we can relate to instantly upon hearing. So, many of the Han-shan poems are not narrowly prescribed images of locale, but can help us be at home on the whole planet, in any landscape.

My long-time friend Chung Ling, a scholar, translator, teacher, and writer, has been studying the Han-shan phenomenon for years. In one article she took me to task for making the Han-shan landscape feel like the chilly, high, rocky ranges of the Sierra Nevada. Her criticism sent me to researching vegetation and climate maps, and I noted that truly much of southeast China is almost subtropical. But some of the key poems mention the rocky, chllly, difficult landscape and speak of late spring snow and early winters. The Tien Tai mountains rise to almost 4,000 feet. Surely “Cold Mountain” did not just make that cold mountain up.

The Dharma name my teacher 小田雪窓 Oda Sessō (1901-1966) Rōshi eventually gave me, in Sino-Japanese 聽風 Chōfū, which would be read in Chinese as “Ting Feng” – “Listen to the wind” – is from two lines of a Han-shan poem that were among those I translated [see poem no 5]. Since the Roshi did not speak or read English, and I doubt he even knew I had done any work on the mysterious old poet, I have no idea how it was he picked out such a name (other than that Dharma-names often come from old Chinese poems). A sign I guess of some territory where our minds met. Minds meet in the mountains.

– Gary Snyder

27 Poems by Han-shan

Translated by Arthur Waley

In Encounter, September 1954, pp. 3-8

The Chinese poet Han-shan lived in the 8th and 9th centuries. He and his brothers worked a farm that they had inherited; but he fell out with them, parted from his wife and family, and wandered from place to place, reading many books and looking in vain for a patron. He finally settled as a recluse on the Cold Mountain (Han-shan) and is always known as "Han-shan." This retreat was about twenty-five miles from T'ien-t'ai, famous for its many monasteries, both Buddhist and Taoist, which Han-shan visited from time to time. In one poem he speaks of himself as being over a hundred. This may be an exaggeration ; but it is certain that he lived to a great age.

In his poems the Cold Mountain is often the name of a state of mind rather than of a locality. It is on this conception, as well as on that of the "hidden treasure," the Buddha who is to be sought not somewhere outside us, but "at home" in the heart, that the mysticism of the poems is based.

The poems, of which just over three hundred survive, have no titles.

I.

From my father and mother I inherited land enough--

And need not envy others' orchards and fields.

Creak, creak goes the sound of my wife's loom;

Back and forth my children prattle at their play.

They clap their hands to make the flowers dance ;

Then chin on palm listen to the birds' song.

Does anyone ever come to pay his respects?

Yes, there is a woodcutter who often comes this way.II.

I have thatched my rafters and made a peasant hut;

Horse and carriage seldom come to my gate--

Deep in the woods, where birds love to forgather,

By a broad stream, the home of many fish.

The mountain fruits child in hand I pluck;

My paddy fidd along with my wife I hoe.

And what have I got inside my house?

Nothing at all but one stand of books.III.

When I was young I weeded book in hand,

Sharing at first a home with my elder brothers.

Something happened, and they put the blame on me;

Even my own wife turned against me.

So I left the red dust of the world and wandered

Hither and thither, reading book after book

And looking for some one who would spare a drop of water

To keep alive the gudgeon in the carriage rut.IV.

Wretched indeed is the scholar without money;

Who else knows such hunger and cold?

Having nothing to do he takes to writing poems,

He grinds them out till his thoughts refuse to work.

For a starveling's words no one has any use;

Accept the fact and cease your doleful sighs.

Even if you wrote your verses on a macaroon

And gave them to the dog, the dog would refuse to eat.V.

Wise men, you have forsaken me;

Foolish men, I haw.' forsaken you.

Being not foolish and also not wise

Henceforward I shall hear from you no more.

When night falls I sing to the bright moon,

At break of dawn I dance among the white clouds.

Would you have me with closed lips and folded hands

Sit up straight, xvaifing for my hair to go grey?VI.

I am sometimes asked the way to the Cold Mountain;

There is no path that goes all the way.

Even in summer the ice never melts;

Far into the morning the mists gather thick.

How, you may ask, did I manage to get here?

My heart is not like your heart.

If only your heart were like mine

You too would be living where I live now.VII.

Long, long the way to the Cold Mountain;

Stony, stony the banks of the chill stream.

Twitter, twitter--always there are birds;

Lorn and lone--no human but oneself.

Slip, slap the wind blows in one's face;

Flake by flake the snow piles on one's clothes.

Day after day one never sees the sun;

Year after year knows no spring.VIII.

I make my way up the Cold Mountain path;

The way up seems never to end.

The valley so long and the ground so stony;

The stream so broad and the brush so tangled and thick.

The moss is slipperT, rain or no rain;

The pine-trees sing even when no wind blows.

Who can bring himself to transcend the bonds of the world

And sit with me among the white clouds?IX.

Pile on pile, the glories of hill and stream;

Sunset mists enclose flanks of blue.

Brushed by the storm my gauze cap is wet;

The dew damps my straw-plaited coat.

My feet shod with stout pilgrim-shoes,

My hand grasping my old holly staff

Looking again beyond the dusty world

What use have 1 for a land of empty dreams?X.

I went off quiedy to visit a wise monk,

Where misty mountains rose in myriad piles.

The Master himself showed me my way back,

Pointing to where the moon, that round lamp, hung.XI.

In old days, when I was very poor,

Night by night I counted another's treasures.

There came a time when I thought things over

And decided to set up in business on my own.

So I dug at home and came upon a buried treasure;

A ball of saphire--that and nothing less!

There came a crowd of blue-eyed traders from the West

Who had planned together to bid for it and take it away.

But I straightway answered those merchants, saying

"This is a jewel that no price could buy."XII.

Leisurely I wandered to the top of the Flowery Peak;

The day was calm and the morning sun flashed.

I looked into the dear sky on every side.

A white cloud was winging its crane's flight.XIII.

I have for dwelling the shelter of a green cliff;

For garden, a thicket that knife has never trimmed.

Over it the flesh creepers hang their coils;

Ancient rocks stand straight and tall.

The mountain fruits I leave for the monkeys to pick;

The fish of the pool vanish into the heron's beak.

Taoist writings, one volume or two,

Under the trees I read--nam, nam.XIV.

The season's change has ended a dismal year;

Spring has come and the colours of things are flesh.

Mountain flowers laugh into the green pools,

The trees on the rock dance in the blue mist.

Bees and butterflies pursue their own pleasure;

Birds and fishes are there for my delight.

Thrilled with feelings of endless comradeship

From dusk to dawn I could not dose my eyes.XV.

A place to prize is this Cold Mountain,

Whose white clouds for ever idle on their own,

Where the cry of monkeys spreads among the paths,

Where the tiger's roar transcends the world of men.

Walking alone I step from stone to stone,

Singing to myself I clutch at the creepers for support.

The wind in the pine-trees makes its shrill note;

The chatter of the birds mingles its harmony.XVI.

The people of the world when they see Han-shan

All regard him as not in his right mind.

His appearance, they say, is far from being attractive,

Tied up as he is in bits of tattered cloth.

"What we say, he cannot understand;

What he says, we do not say."

You who spend all your time in coming and going,

Why not try for once coming to the Han-shan?XVII.

Ever since the time when I hid in the Cold Mountain

I have kept alive by eating the mountain fruits.

From day to day what is there to trouble me?

This my life follows a destined course.

The days and months flow ceaseless as a stream;

Our time is brief as the flash struck on a stone.

If Heaven and Earth shift, then let them shift;

I shall still be sitting happy among the rocks.XVIII.

When the men of the world look for this path arnid the clouds

It vanishes, with not a trace where it lay.

The high peaks have many precipices;

On the widest gulleys hardly a gleam falls.

Green walls close behind and before;

White clouds gather east and west.

Do you want to know where the cloud-path lies?

The cloud-path leads from sky to sky.XIX.

Since first I meant to explore the eastern cliff

And have not done so, countless years have passed.

Yesterday I pulled myself up by the creepers,

But half way, was baffled by storm and fog.

The cleft so narrow that my clothing got caught fast;

The moss so sticky that I could not free my shoes.

So I stopped here under this red cinnamon,

To sleep for a while on a pillow of white clouds.XX.

Sitting alone I am sometimes overcome

By vague feelings of sadness and unrest.

Round the waist of the hill the clouds stretch and stretch;

At the mouth of the valley the winds sough and sigh.

A monkey comes; the trees bend and sway;

A bird goes into the wood with a shrill cry.

Time hastens the grey that wilts on my brow;

The year is over, and age is comfortless.XXI.

Last year when the spring birds were singing

At this time I thought about my brothers.

This year when chrysanthemums are fading

At this time the same thought comes back.

Green waters sob in a thousand streams,

Dark clouds lie flat on every side.

Till life ends, though I live a hundred years,

It will rend my heart to think of Ch'ang-an.XXII.

In the third month when the silkworms were still small

The girls had time to go and gather flowers,

Along the wall they played with the butterflies,

Down by the water they pelted the old frog.

Into gauze sleeves they poured the ripe plums;

With their gold hairpins they dug up bamboo-sprouts.

With all that glitter of outward loveliness

How can the Cold Mountain hope to compete?XXIII.

Last night I dreamt that I was back in my home

And saw my wife weaving at her loom.

She stayed her shutde as though thinking of something;

When she lifted it again it was as though she had no strength.

I called to her and she turned her head and looked;

She stared blankly, she did not know who I was.

Small wonder, for we parted years ago

When the hair on my temples was still its old colour.XXIV.

I have sat here facing the Cold Mountain

Without budging for twenty-nine years.

Yesterday I went to visit friends and relations;

A good half had gone to the Springs of Death.

Life like a guttering candle wears away--

A stream whose waters forever flow and flow.

Today, with only my shadow for company,

Astonished I fred two tear-drops hang.XXV.

In old days (how long ago it was!)

I remember a house that was lovelier than all the rest.

Peach and plum lined the little paths;

Orchid and iris grew by the stream below.

There walked beside it girls in satins and silks;

Within there glinted a robe of kingfisher-green.

That was how we met; I tried to call her to me,

But my tongue stuck and the words would not come.XXVI.

I sit and gaze on tiffs highest peak of all;

Wherever I look there is distance without end.

I am all alone and no one knows I am here,

A lonely moon is mirrored in the cold pool.

Down in the pool there is not really a moon;

The only moon is in the sky above.

I sing to you this one piece of song;

But in the song there is not any Zen.XXVII.

Should you look for a parable of life and death

Ice and water are the true comparisons.

Water binds and turns into ice;

Ice melts and again becomes water.

Whatever has died will certainly be born,

Whatever has come to life must needs die.

Ice and water do each other no harm;

Life and death too are both good.

“Han-shan - Words from Cold Mountain”

Translated by A. S. Kline (2006)

http://www.poetryintranslation.com/klineashanshan.htm

Introduction

Han-shan, the Master of Cold Mountain, and

his friend Shi-te, lived in the late-eighth to

early-ninth century AD, in the sacred Tien-tai

Mountains of Chekiang Province, south of the

bay of Hangchow. The two laughing friends,

holding hands, come and go, but mostly go,

dashing into the wild, careless of others reality,

secure in their own. As Han-shan himself says,

his Zen is not in the poems. Zen is in the mind.

1.

Don’t you know the poems of Han-shan?

They’re better for you than scripture-reading.

Cut them out and paste them on a screen,

Then you can gaze at them from time to time.

2.

Where’s the trail to Cold Mountain?

Cold Mountain? There’s no clear way.

Ice, in summer, is still frozen.

Bright sun shines through thick fog.

You won’t get there following me.

Your heart and mine are not the same.

If your heart was like mine,

You’d have made it, and be there!

3.

Cold Mountain’s full of strange sights.

Men who go there end by being scared.

Water glints and gleams in the moon,

Grasses sigh and sing in the wind.

The bare plum blooms again with snow,

Naked branches have clouds for leaves.

When it rains, the mountain shines –

In bad weather you’ll not make this climb.

4.

A thousand clouds, ten thousand streams,

Here I live, an idle man,

Roaming green peaks by day,

Back to sleep by cliffs at night.

One by one, springs and autumns go,

Free of heat and dust, my mind.

Sweet to know there’s nothing I need,

Silent as the autumn river’s flood.

5.

High, high, the summit peak,

Boundless the world to sight!

No one knows I am here,

Lone moon in the freezing stream.

In the stream, where’s the moon?

The moon’s always in the sky.

I write this poem: and yet,

In this poem there is no Zen.

6.

Thirty years in this world

I wandered ten thousand miles,

By rivers, buried deep in grass,

In borderlands, where red dust flies.

Tasted drugs, still not Immortal,

Read books, wrote histories.

Now I’m back at Cold Mountain,

Head in the stream, cleanse my ears.

7.

Bird-song drowns me in feeling.

Back to my shack of straw to sleep.

Cherry-branches burn with crimson flower,

Willow-boughs delicately trail.

Morning sun flares between blue peaks,

Bright clouds soak in green ponds.

Who guessed I’d leave that dusty world,

Climbing the south slope of Cold Mountain?

8.

I travelled to Cold Mountain:

Stayed here for thirty years.

Yesterday looked for family and friends.

More than half had gone to Yellow Springs.

Slow-burning, life dies like a flame,

Never resting, passes like a river.

Today I face my lone shadow.

Suddenly, the tears flow down.

9.

Alive in the mountains, not at rest,

My mind cries for passing years.

Gathering herbs to find long life,

Still I’ve not achieved Immortal.

My field’s deep, and veiled in cloud,

But the wood’s bright, the moon’s full.

Why am I here? Can’t I go?

Heart still tied to enchanted pines!

10.

If there’s something good, delight!

Seize the moment while it flies!

Though life can last a hundred years,

Who’s seen their thirty thousand days?

Just an instant then you’re gone.

Why sit whining over things?

When you’ve read the Classics through,

You’ll know quite enough of death.

11.

The peach petals would like to stay,

But moon and wind blow them on.

You won’t find those ancient men,

Those dynasties are dead and gone.

Day by day the blossoms fall,

Year by year the people go.

Where the dust blows through these heights,

There once shone a silent sea.

12.

Men who see the Master

Of Cold Mountain, say he’s mad.

A nothing face,

Body clothed in rags.

Who dare say what he says?

When he speaks we can’t understand.

Just one word to you who pass –

Take the trail to Cold Mountain!

13.

Han-shan has his critics too:

‘Your poems, there’s nothing in them!’

I think of men of ancient times,

Poor, humble, but not ashamed.

Let him laugh at me and say:

‘It’s all foolishness, your work!’

Let him go on as he is,

All his life lost making money.

14.

Cold Mountain holds a naked bug,

Its body’s white, its head is black.

In its hands a pair of scrolls,

One the Way and one its Power.

It needs no pots or stove.

Without clothes it wanders on,

But it carries Wisdom’s blade,

To cut down mindless craving.

15.

I’m on the trail to Cold Mountain.

Cold Mountain trail never ends.

Long clefts thick with rock and stones,

Wide streams buried in dense grass.

Slippery moss, but there’s been no rain,

Pine trees sigh, but there’s no wind.

Who can leap the world’s net,

Sit here in the white clouds with me?

16.

Men ask the way through the clouds,

The cloud way’s dark, without a sign.

High summits are of naked rock.

In deep valleys sun never shines.

Behind you green peaks, and in front,

To east the white clouds, and to west –

Want to know where the cloud way lies?

It’s there, in the centre of the Void!

17.

Sitting alone by folded rocks,

Mist swirling even at noon,

Here, inside my room, it’s dark.

Mind is bright, clear of sound.

Through the shining gate in dream.

Back by the stone bridge, mind returns.

Where now the things that troubled me?

Wind-blown gourd rattling in the tree.

18.

Far-off is the place I chose to live.

High hills make for silent tongues.

Gibbons screech in valley cold

My gate of grass blends with the cliff.

A roof of thatch among the pines,

I dig a pool, feed it from the stream.

No time now to think about the world,

The years go by, shredding ferns.

19.

Level after level, falls and hills,

Blue-green mist clasped by clouds.

Fog wets my flimsy cap,

Dew soaks my coat of straw.

A pilgrim’s sandals on my feet,

An old stick grasped in my hand.

Gazing down towards the land of dust,

What is that world of dreams to me?

20.

What a road the Cold Mountain road!

Not a sign of horse or cart.

Winding gorges, tricky to trace.

Massive cliffs, who knows how high?

Where the thousand grasses drip with dew,

Where the pine trees hum in the wind.

Now the path’s lost, now it’s time

For body to ask shadow: ‘Which way home?’

21.

Always it’s cold on this mountain!

Every year, and not just this.

Dense peaks, thick with snow.

Black pine-trees breathing mist.

It’s summer before the grass grows,

Not yet autumn when the leaves fall.

Full of illusions, I roam here,

Gaze and gaze, but can’t see the sky.

22.

No knowing how far it is,

This place where I spend my days.

Tangled vines move without a breeze,

Bamboo in the light shows dark.

Streams down-valley sob for whom?

Mists cling together, who knows why?

Sitting in my hut at noon,

Suddenly, I see the sun has risen.

23.

The everyday mind: that is the way.

Buried in vines and rock-bound caves,

Here it’s wild, here I am free,

Idling with the white clouds, my friends.

Tracks here never reach the world;

No-mind, so what can shift my thought?

I sit the night through on a bed of stone,

While the moon climbs Cold Mountain.

24.

I was off to the Eastern Cliff.

Planned that trip for how long?

Dragged myself up by hanging vines,

Stopped halfway, by wind and fog.

Thorn snatched my arm on narrow tracks,

Moss so deep it drowned my feet,

So I stopped, under this red pine.

Head among the clouds, I’ll sleep.

25.

Bright water shimmers like crystal,

Translucent to the furthest depth.

Mind is free of every thought

Unmoved by the myriad things.

Since it can never be stirred

It will always stay like this.

Knowing, this way, you can see,

There is no within, no without.

26.

Are you looking for a place to rest?

Cold Mountain’s good for many a day.

Wind sings here in the black pines,

Closer you are, the better it sounds.

There’s an old man sitting by a tree,

Muttering about the things of Tao.

Ten years now, it’s been so long

This one’s forgotten his way home.

27.

Cold rock, no one takes this road.

The deeper you go, the finer it is.

White clouds hang on high crags.

On Green Peak a lone gibbon’s cry.

What friends do I need?

I do what pleases me, and grow old.

Let face and body alter with the years,

I’ll hold to the bright path of mind.

Three Short Poems by Han-shan

Translated by Peter Hobson

Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 11, No. 2. (Spring, 1977)

Cf. Poems of Han Shan. Translated by Peter Hobson. Sacred Literature Series,

Walnut Creek, CA:

AltaMira Press, 2002, 160 p.

How pleasant is Kazan's path

with no track of horse or carriage,

over linked valleys

with unremembered passes and

peak upon peak

of unknowable heights,

where the dew

weeps on a thousand grasses

and the wind

moans to a single pine;

now, at the point where

I falter in the way,

my form asks my shadow

“whence came we?”

Men ask about Kanzan's path

though Kanzan says

his road is inaccessible,

summer-skies

where the ice has not melted,

and sunshine

where the mist hangs thick;

“how will you draw close

to one like me when

your heart is not as my heart?

If only your heart

were as my heart, then

you would reach the centre.

The people of our times

are trying to track down

the path of clouds, but

the cloud-path is trackless,

high mountains

with many an abyss and

broad valleys

with little enough light,

blue peaks

with neither near nor far,

white clouds

with neither East nor West;

“You wish to know

where the cloud-path lies?

It lies in utter emptiness.”

Selected Han-Shan Poems for Hippie Reading

by the Buddhist Yogi C. M. Chen

CW30_No.49

http://www.yogichen.org/cw/cw30/bk049.html

Han-Shan was the incarnation of the Mahabodhisattva Manjusri. His poems, of course, do not belong to the School of Poetic Laws but to that of Naturalism and Spiritualism. He himself also confessed that he neglected those Poetic Laws, as is said in his poem:Someone laughs at my poems,

Yet they are fine and fun!

Need no commentary,

Nor any signatory.

Not sad for no one knows,

Hardly anyone follows.

The poetic law I neglect,

Many mistakes can detect,

Yet when they meet wise men.

Inspire the whole world they can.Hence, those who want to learn the methods of poetic rules, laws, rhymes, tones and antithesis, do not pay deep appreciation to Han-Shan's poems. Because there were many well known poets in the same generation of the Tung Dynasty when Han-Shan lived, the young poets neglected Han-Shan and followed others. However, the Buddhists of China, both scholars and practitioners, do like his poems very much. When I was young I could repeat many of his poems.

Nowadays his poems are respected by Hippies in the West and many new translations have been recently published. Burton Watson has translated 100 of Han-Shan's poems, Bill Wyatts about 80, Arthur Waley 27, and Gary Snyder 24, as far as I have learned. There might be some more translations in English, French and German which I have not yet seen. Our Saint Han-Shan foretold that his poems will inspire the whole world and this seems to become true.

Hippies call him The Ancient Chinese Hippie. The problem is whether or not an Ancient Hippie is the same as a modern one. I therefore made a comparative study and from the content and purport of Han-Shan's poems, I give some advice to the modern Hippie with a hope that every modern Hippie can possess the same merits and characteristics as Han-Shan. That is why this booklet has the title it does.

The total number of Han-Shan's poems was 600 as his poem states:

Quintets are five hundred,

Septets seventy-nine,

Triplets are twenty-one

Six hundred all of mine.

They are written in caves,

They are all that I have,

One realizes altogether

Might be the Buddha's mother!But nowadays we can find only about 300 of his poems because they were written on cave walls, trees, bamboo and walls, some of which had already vanished in his lifetime.

Here I have translated about eighty poems. They are selected from the Chinese edition as a witness to my advice and hope that every Hippie will treat them as the teaching of Han-Shan himself and that some advantages of spiritual life may be found therein.

I. Drop Out

A. Han-Shan the Mahabodhisattva dropped out completely and never dropped into any community. He had two very affectionate friends. One was Feng Kan, an incarnation of the Buddha Amitabha; the other was Shih-Teh, an incarnation of Samantabhadra. Both were working in the Kuo-Ching monastery. Feng Kan was a rice-pounder and Shih-Teh was an errand-boy in the kitchen who collected the surplus food and kept it in a bamboo for Han-Shan. But they never united together as a community. Han-Shan did not even like the monastery and lived alone on a mountain.

I live in a corner out of the way

And I visit the Holy monks on highway

I often discuss the Tao with Feng Kan

(Tao means path not Taoism)

And talk with Shih-Teh, and a little while stay.

I go back and climb the cliff alone!

Not one talks with me on the path so long.

The Tao is like a stream without source,

Yet the water is in every mouth!Our modern Hippie, after dropping out of the plastic society, drops into a modern plastic society in which there are no laws, rules, leaders, but only over-freedom which creates many dangerous situations such as suicide, homicide, venereal disease, craziness, and so on, even more so than in the plastic society.

B. Han-Shan dropped out like a deer who has been wounded by a hunter and flees away, never touching any man again. Modern Hippies drop out like fish when bait is swallowed. They are easily lured by some party That is why some Chinese Hippies in California work for the Communist Party, being lured by $20 per day! Try reading this poem of Han-Shan and take the example of the deer:

In remote forest lives the deer,

Drinks water and eats grass with cheer!

Stretches out its legs when it lies down,

How blissful is this creature dear !

If it's caged in a splendid hall,

Where food is quite rich but with fear,

It will always refuse to taste,

In its pure mind it could not bear!C. Han-Shan's dropping out resulted in his poverty, but the modern Hippies still take the good food of the plastic society and use the modern things of the plastic society. Are not habits like movies and singing inherited from the plastic society? Han-Shan begged--is there any modern Hippie who is really like a beggar? Actually most Hippies are from the middle class; they have money to spend in the same manner as other members of the plastic society.

My dear Hippies, try reading the following poems. Would not tears drop from your sympathetic eyes!

New corn is not yet out,

Old corn is all at nought!

I beg from those rich men and wait,

Standing lonely outside their gate.

Husband says ask wife,

Wife says ask my husband.

Both are very stingy,

The more rich, the more bound!If you ask of its colour,

It's neither red nor yellow.

In summer it's my shirt,

In winter it's my mat.

It can be used as both.

All year long, it is thus!

Dropped out to be real hermit,

Sleep only on the summit.

Green lichen climb everywhere,

Blue creeks sound like songs here and there,

I feel happy and gay,

I remain in a quiet way!

No defilement from the world,

A pure white lotus I hold!Han Shan has a house:

No walls, no mouse!

Six doors are open,

Roof is the heaven!

Rooms have nothing at all,

East wall beats the west wall.

No family, who follows?

No furniture, who borrows?

A little fire to rid my cold,

When I'm hungry herbs are boiled.

Not like those rich farmers

Occupy many farms.

They will all go to hell soon.

Once they fall never come on!

Please think it o'er and o'er,

You will find out what's your wrong!Alas! ill and poor man!

No friend, no kinsman!

No rice in the jar, Dust is in the pan.

My hut leaks, My bed breaks,

Yet I'm not sad,

For sad makes bad!Some persons did advise me,

To accept a kind of fee!

To build good farm with walls!

Alas! I could not agree!When I live in village,

Men treat me as a sage!

When I go to city,

Men seem to have pity!

Some say my robe is short,

Others say my shirt is dirty.

With eagle's eyes look at me,

They dance! As sparrow and bee!D. Han Shan had passed through the hearing and thinking knowledges of Buddhism and was hastened by the Truth of Impermanence to drop out for the purpose of having more time to practice Buddhism diligently. But in Hippiedom, other than those few who have already become Buddhists, most Hippies never see any kind of truth in religion and are driven by the industrial tension of their nation, difficult examinations of college and the heavy responsibility of family to drop-out. They want only rest, relaxation and laziness, and they have not meditated on the idea of impermanence. When they were rebelling, they hoisted flags on which was written, "There is no cure for birth or death, but enjoy the interval." Their definition of birth and death are the actual dates of one's birth and death and the whole lifetime between those dates is the interval. But Buddhists say our life is only based upon inhalation and exhalation, when one is stopped, life is finished. One realizes that one dies every second, there is no certain or confirmed interval, so one has to utilize even a microsecond to practice the Dharma and one should not do any other worldly tasks. That is why one must drop out completely. So many hungup people scarcely drop out despite my tearful advice. If you have already dropped out, it is very rare and you must meditate on the truth of Impermanence and practice the Dharma diligently. One should not be lazy. Please read the following poems of Han-Shan carefully:

Since I came to the region of Tien-Tai,

How many winters and springs come and go.

Landscape does not change, men become old,

And so many youths died I often saw.I dwell in the mountain with crags,

Far from humans there are just birds.

What is left in the old court yard?

A stone and some white clouds to gird.

I have lived there for many years,

I saw winter and spring as a cord.

Who could describe the ruling palace?

Its vanity who will regard?Even those ancient sages

Could reach the non-death stage.

Rebirth becomes again death,

The only dust he has.Bones gather as mountain,

Tears as stream it maintains,

They left only empty names,

Transmigration is certain.See the flower under leaves.

How long can it nicely live.

Today it fears to be picked,

And tomorrow it takes leave.It is just like the Beauty,

When she is old, she seems dirty.

Compare her with the flower

Nice looking can not deceive!Riding my horse by a ruined town,

Sad for its long vanished past!

High and low walls are with grief!

Large and small are the old graves.

Drifting shadows are from silent bush,

Long moan from the graveyard ends a hush.

It's a pity too mundane is our flesh.

It should be immortal through gnostic wash!On bay horses with coral whip in hands,

Young folk galloped along Lo-young Land!

They are proud of their youth and strong health!

Which leads them to forget that age will end!

Even though white hair will grow on old men,

Rosy cheeks can by no means be defended.

Take one look at the graves of Pewmong,

Is it like the Peng-Lai, a fairy land?II. Turn On

A. Han-Shan never turned on to drugs as can be seen in his poem:

Some men do fear to be old,

But worldly things do hold.

They seek drugs for long life,

Dig up herbs either hot or cold

Many years get no effect.

Himself is the one to scold.

A hunter wearing the robe,

How Sand could be the gold!I am a monk without formal discipline.

Even for longevity drugs I'm not taking

There is not any sage still remains--

Their graves are at the foot of mountains.One of his poems may be misunderstood to mean that he had taken drugs. But in my translation below, the sentences are very clear:

I lived Cold Mountain many an Autumn,

Without sorrow, alone I sing my song.

The silent door need not shut,

Sweet spring goes itself so long.

Nectar boils in the cauldron,

Pine leaves and tea taste are strong.

Gatha Pill stops my hunger.

Mind is quiet, Bone is like stone!The Chinese transliteration of what I translate as Gatha Pill is "Chia T'o". It is from hybrid Sanskrit and can have two meanings, either translated from Gatha which means stanza, or from Agoda which means a kind of medicine. The former meaning can take the latter as its metaphor as the Agoda can cure the poison, so the stanza of Dharma (Gatha) can cure the mental poison. It was not a pill for longevity or for searching for God. In a translation of this poem by a Westerner this was mistaken as a drug, but I translate it as Gatha which means stanza, and it may be proved by the Buddha's saying in the Avatamsaka Sutra:

I am just like the Agoda, Which cures the poison!

B. Han-Shan never turned on to free love. From the following poems we know what his idea concerning women was:

The kids in the city

All well dressed in beauty

Play with birds and flowers,

And sing songs under moonlight.

Their long poems seems for good,

Their charm-dance looks are right.

Could they do this forever?

Roses will be buried in dirt!

A young girl when married to an old man,

Will not bear white hair of her husband.

Youth married old woman, in that case,

Not be pleased by her yellow face.

But how is the old man with old wife?

They have no love for each other in life,

A young man and a young girl in one door,

Behave lovingly to each other but no more!The girdle ornaments of the girl in town,

Give forth their tinkling and beautiful sound.

The parrot voice is heard in the flowers.

The fine guitar is strummed under the moon.

A lengthy song takes three months to recite.

A short dance attracts men of great amount.

Alas! It's not continuously like this,

The Lotus can not endure the monsoon.Small birds sing on the branch of rose,

Their sound is surely sweet and smooth.

The nice girl with a pearl-like face,

Looks at it and sings some sweet prose.

Plays so long still not satisfied,

She enjoys her own golden youth.

When rose falls and birds fly away,

She weeps as Autumn winds arose.Han-Shan viewed those girls as all other things as impermanent. He did not live even with his own wife. His poem quoted below can prove this:

I have dreamt that I returned home.

Saw my wife weaving at her loom.

She stopped the shuttle, seemed something desired.

She lifted it again and looked so tired.

I cried out to her,she looked at me.

No longer could she know whom I might be.

Because since our parting years went past,

My hair on my temple (body) has turned to frost.What Dharmas was Han-Shan turning on to? The poems mentioned below have been classified. My good Hippies may take them as good examples and practice the same as did Han-Shan himself or his incarnations.

C. Han-Shan turned on to the Vinayas or commandments.

It was twenty years ago I called at Kuo Ching Temple.

And all the monks laughed at me.

They said I was a foolish man.

Ah, was I really a fool?

But not a style of their sample.

I do not know my real self,

How could they know my example.

I bowed my head but did not ask,

Even ask what was their principle.

Whenever some man blamed me,

I knew that it was so simple.

Though I didn't give tooth for tooth,

Yet I enjoyed my mind ample.The speech that I had, Seemed to be so mad.

Face to face I say, So hate me they may.

Straight mind causes straight talk,

There is nothing dark.

When pass the death-creek,

I may be a little quick.

You fall into Hell.

Your Karma will tell!My eastern neighbour is an old woman,

She became so rich a few years before,

Three years back she was more poor,

Now she laughs at me as no money more.

She laughs at me as I did before,

I laugh at her, were unable to score.

If we laugh at each other without cease

We might be left in a game without peace.

Anxiety is not easy to drive away.

Somebody said this is not really the way.It was driven away yesterday,

But it's coming again on this day.

Anxiety has lingered on since last month

Will be renewed in the future and stay.

All men know that under their hats

There is no less sad than he's got.I advise all you youngsters

Quickly leave the fire quarter.

Three carriages have been prepared,

Carry you from the shelter.

Pure land is everywhere.

Once for all, all things alter!

In the space no up nor down,

To and fro there is no matter.

If you realize such a truth,

There is nowhere you can't enter!D. Han-Shan turned on to the great compassion. Although he dropped out he never hated the Hung-ups as deeply as modern Hippies do. My good Hippies, try to practice the Bodhicitta and great compassion, and do not join any rebelling movement if you desire real fellowship with Han-Shan.

When all men meet Han-Shan,

They call him mad person.