ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

豐幹 Fenggan (active 627-649)

(Rōmaji:) Bukan

(English:) "Big Stick"

(Magyar:) Feng-kan

Tartalom |

Contents |

Feng-kan |

Fenggan Meditation Master Tiantai Feng'gan Record of Meditation Master Fenggan Japanese Paintings of |

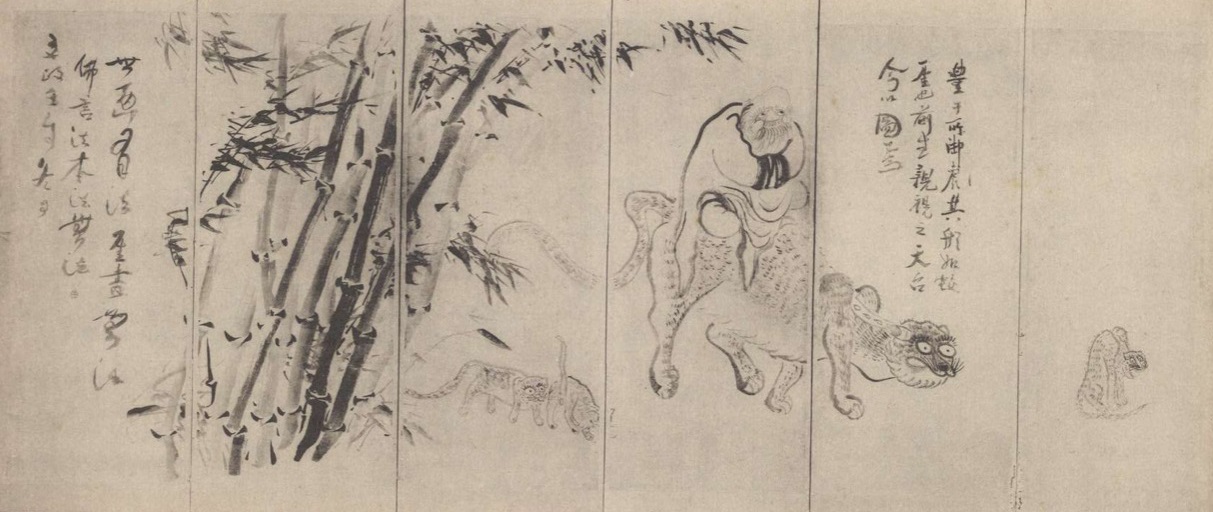

![]()

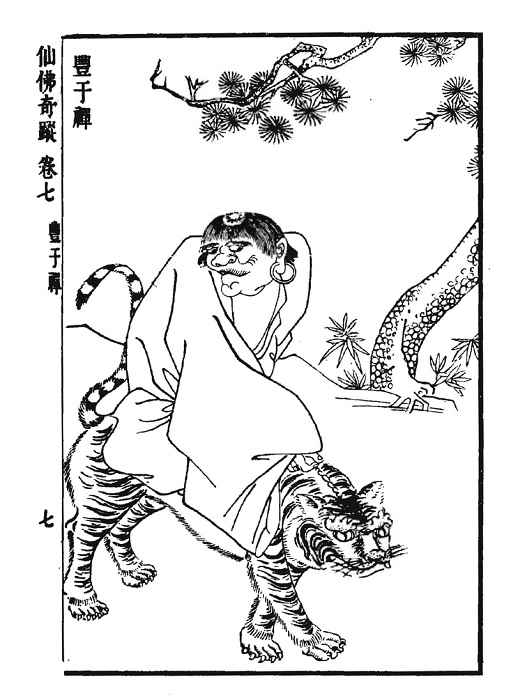

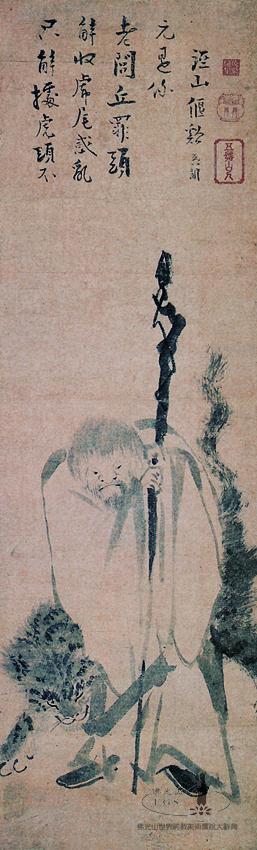

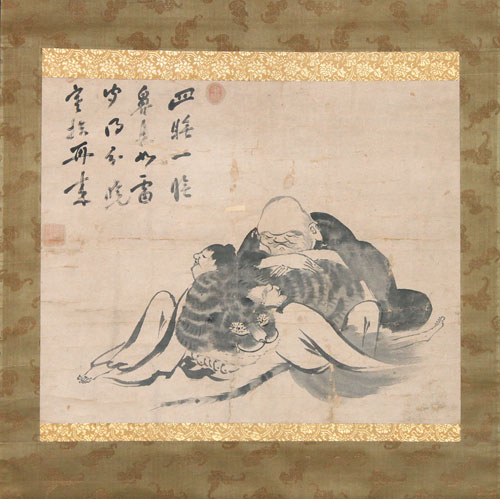

Fenggan and Tiger 豐杆與老虎圖

by Li Que 李確 (13th century) Before 1263, Southern Song (1127-1279)

Hanging scroll, ink on paper, 104.8 x 32.1 cm

Encomium by Yanxi Guangwen 偃溪廣聞 (1189-1263)

Myoshinji, 妙心寺 Kyoto

Important Cultural Property

Encomium:

Only explaining how to grasp the tiger's head,

Not explaining how to grab the tiger's tail,

Befuddling old Lü Qiu,

The guilty party was you!

Yanxi Guangwen of Jing Shan

只解據虎頭 , 不解取虎尾 , 或亂老閭丘 , 罪頭元是儞 。 徑山 ; 谿黃聞 。

Fenggan

From Wikipedia

Poems translated by Red Pine

Fenggan (simplified Chinese: 丰干; traditional Chinese: 豐干; pinyin: Fēnggān; Wade–Giles: Fengkan; literally: "Big Stick", fl. 9th century) was a Chinese Zen monk-poet lived in the Tang Dynasty,

associated with Hanshan and Shide in the famed "Tiantai Trio" (天台三聖).

Legendarily, Feng appeared one day at Guoqing Temple (located by the East China Sea, in the Tiantai mountain range), a 6-foot-tall (1.8 m) monk with an unshaven head, riding a tiger. From then on, he took up residence in the temple behind the library, where he would hull rice and chant sutras.

The few accounts of him record that he became close friends to Hanshan, and was the one who found the orphaned Shide, named him, and brought him to the temple. From these and other anecdotes, it appears that Feng was the oldest of the three.

The circumstances of his death are as murky as his life: the stories in which Feng is any more than a name or foil for Hanshan cease after he healed a local prefect. It has been conjectured that Hanshan's Poem 50 refers to his death:

Show me the person who doesn't die

death remains impartial

I recall a towering man

who is now a pile of dust

the World Below knows no dawn

plants enjoy another spring

but those who visit this sorrowful place

the pine wind slays with grief

Very few of Feng's poems survive, but the ones which do are very revealing; the third of the four confirms Feng's relationships with the other members of the Tientai Trio:

3

寒山特相访,

拾得常往来。

论心话明月,

太虚廓无碍。

法界即无边,

一法普遍该。Whenever Cold Mountain stops to visit

or Pick-Up pays his usual call

we talk about the mind the moon

or wide open space

reality has no limits

so anything real includes it all

The first of the poems appears to confirm the stories of how he was an itinerant monk prior to stopping at Kuoching Temple (and even then he would depart at least once for a pilgrimage to Mount Wutai):

1

馀自来天台,

凡经几万回。

一身如云水,

悠悠任去来。

逍遥绝无闹,

忘机隆佛道。

世途岐路心,

众生多烦恼。I have been to Tientai

maybe a million times

like a cloud or river

drifting back and forth

Roaming free of trouble

trusting the Buddha's spacious path

while the world's forked mind

only brings men pain

The fourth poem is especially important, since it unmistakably references the challenge the Fifth Patriarch of Zen set his would-be successors ~713 C. E. making it impossible for Feng (and by extension Hanshan and Shide) to predate the 720's, thereby eliminating many other dating possibilities:

4

本来无一物,

亦无尘可拂。

若能了达此,

不用坐兀兀。Actually there isn't a thing

much less any dust to wipe away

Who can master this

doesn't need to sit there stiff

(The exchange referenced was between two potential successors Shenxiu and Huineng. Shenxiu to demonstrate his mastery of Zen wrote the following poem: The body is the Bodhi Tree \ the mind like a clear mirror. \ Always wipe it clean, \ don't let it gather dust. Huineng retorted with Bodhi isn't a tree, \ what's clear isn't a mirror. \ Actually, there isn't a thing- \ where do you get this dust?)

It is difficult to judge Feng's poetic oeuvre with only four works to judge by, and only one really poetic. But it appears that his poetry's formal structures were fairly conventional, and in ideas, from a strictly Buddhist perspective; Hanshan, in contrast, often played with rhymes and tones and structure, and very often dropped in Taoist references, to the point where his actual religious orientation is in some doubt. See for example Feng's second poem, which expresses strictly Buddhist ideas:

2

兀兀沈浪海,

漂漂轮三界。

可惜一灵物,

无始被境埋。

电光瞥然起,

生死纷尘埃。Sinking like a rock in the Sea,

drifting through the Three Worlds

poor ethereal creature

forever immersed in scenes

until a flash of lightning shows

that life and death are dust in space

(The 'Three Worlds' refer to either those of the past, present, and future; or alternatively, those of form, formlessness, and becoming.)

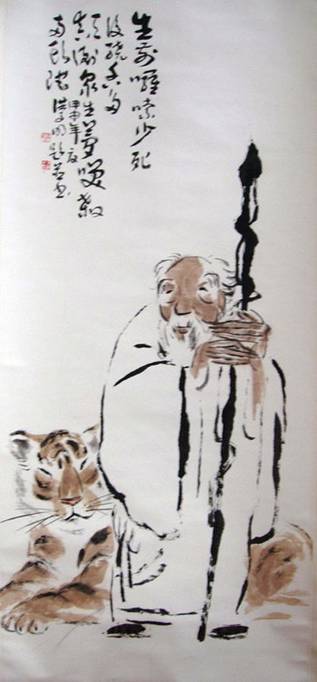

丰干和尚 Fenggan heshang by 洪子明 Hong Ziming (born in 1953)

27.7 Meditation Master Tiantai Feng'gan

天台豐干禪師者 (Bukan / Hōkan)

T 433b11

In. Records of the Transmission of the Lamp: Volume 7: Biographies and Extended Discourses. (Books 27-28), Translated by Randolph S. Whitfield, Kindle Edition, 2019

It is not known where Meditation master Feng'gan hailed from, but that he lived in Guoqing Temple on Mount Tiantai, had his head shaven, including his eyebrows and that he wore a thick long robe. When people would sometimes ask him about the principles of Buddhism, he would merely reply, ‘Time to follow.' Once, singing a hymn of praise to the Dao, he entered the pine gates of the temple astride a tiger. All the monks were amazed.

In the home temple (Guoqing) were two ascetics, Hanshan and Shide. These two were in charge of the kitchen stove; at the end of the day they would exchange a few words, but those listening in surreptitiously could not fathom their import; everybody at the time thought they were crazy men. Only the master was their intimate.

One day Hanshan asked, ‘When the ancient mirror is not polished, how can it shine?'

‘A jade cold-water pot has no reflecting consciousness; (影像 yingxiang) monkeys and apes grope for the moon in the water,' answered the master.

‘This is not shining, may the master please say something more.'

‘The ten thousand virtues are not brought along, so what is there for me to teach?' said the master.

Han and Shi both made obeisance.

Not long afterwards the master was wandering alone on a ritual visit in the Wutai Mountains, when he came across an old greybeard. The master asked him, ‘Surely this is not Mañjuśrī?'

‘Is it possible that there are two Mañjuśris?' answered the greybeard. The master then paid reverence – and before he had risen, greybeard had suddenly vanished.

(Textual comment: A śramana brought this up with Zhaozhou; Zhaozhou then answered for Feng'gan, ‘Mañjuśrī, Mañjuśrī!') Later, returning to Mount Tiantai, the master revealed his cessation.

At first, when His Lordship Luqiu (One character of his name is omitted since it violates the taboo on Emperor Taizu's personal name – Yin 胤) was to leave for Danqiu (Zhejiang, Linhai) to take up the post of prefectural governor, and was about to board the imperial highway, (冰壺 bing hu) he suddenly suffered head pains which the physicians were unable to cure. The master came to visit and said to him, ‘This poor wayfarer comes from Mount Tiantai to pay a courtesy call on His Lordship.' Luqiu related his sickness to the master, who then had a clean basin brought, filled with water, and spluttered it out over him whilst uttering incantations (咒水噴之 zhou shui pen zhi). In a moment Luqiu rose, quite recovered. Luqiu found this strange and asked for indications as to whether this was a good omen or not. ‘After arriving to take up your post, remember to pay respects to Mañjuśrī and Samantabhadra,' replied master Feng'gan.

‘Where are these two bodhisattvas to be found?'

‘The cook and the dishwasher are called Hanshan and Shide,' said the master.

The prefect then departed and soon afterwards arrived at the mountain temple [Guoqing]. There he asked, ‘Is there a meditation master Feng'gan in this temple? And who are the pair Hanshan and Shide?'

The monk Daoqiao, present at the time, answered, ‘Feng'gan was in the old temple behind the library, but there is nobody there these days and all is quiet. As for Han and Shi, they can be seen working in the temple kitchen.' Luqiu went round to the master's place [behind the library] but could only see traces of a tiger. Again he asked Daoqian, ‘What was Feng'gan up to here?'

‘Just hulling grain to feed the monks,' replied Daoqiao. Luqiu then entered the temple kitchen looking for Han and Shi; this is related in the next entry: 27.8 Tiantai Hanshan (Kanzan).

Record of Meditation Master Fenggan1

Translated by Paul Rouzer

The poetry of Hanshan (Cold Mountain), Shide, and Fenggan

Boston; Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2017, pp. 336-340.

No one has determined the ancestry of the Buddhist practitioner

Fenggan. According to the view of elders in the area, he resided at the

Guoqing Temple in the Tiantai Mountains. He cut his hair level with his

eyebrows, and wrapped himself in a woolly robe. Whenever monks or

laypeople made inquiries of him, he'd just say “It all depends.” He was

haggard in appearance, but dignified and imposing, seven feet in height.

His only task was to grind grain for offerings. At night he would bar

the door to his room, then sing and chant to amuse himself. The people

of the district knew him well, and took him to be mad. But sometimes he

would utter something quite out of the ordinary. One day he showed up

riding a tiger along the path through the pine trees and into the temple

grounds. He circled about the temple galleries singing; everyone was ter-

rified, but they all admired his moral authority.

In the past, he cured me of an illness when I was in the capital; but

when I arrived at my office at Cinnabar Hill [the Tiantai district], I could

find no trace of him. He was a worthy who had hidden himself, manifest-

ing himself magically in the region of eastern Ou. 2

There were only some lines written on the walls of his room: 3

1 This note is supposedly written by Lüqiu Yin, the purported author of the Preface.

2 Ou 甌 is an early name for the coastal area of Zhejiang where the Tiantai Mountains are located.

3 The Song Edition prints the first poem in a format separate from the second poem. The first poem is twenty lines long, divided by stanza divisions indicated by rhyme change. The second poem is a short quatrain in gātha style.

Fenggan #1

Ever since I came to Tiantai

Myriads of cycles have gone by.

My single form is like cloud and water,

And through the vastness I go where I please.

Free and easy, with no annoyances,

I forget concerns while enlarging the Buddha's path.

The roads of the world, the crossroads-mind—

Sentient beings have so many annoyances:Stupefied, lost in the wave-tossed sea,

Drifting along on the Three Realms' wheel.

What a pity that this numinous thing1

Since before time has been buried in sensory realms.

A lightning flash like the blink of an eye;

Life and death a scattering of dust.

Hanshan visits me especially,

And Shide comes on rare occasions.

We discuss the mind, speak of the bright moon;

An empty void, broad, without obstruction.

The dharmadhātu has no borders—

One Dharma that encompasses all things.2

Fenggan #2

Originally there is not a single thing

Nor any dust to be brushed off.

If you are able to penetrate this completely,

Then no use to sit there like a lump .31 The Buddha Nature.

2 Dharmadhātu (“realm of reality”) refers to various planes of existence, including the Six Courses.

3 A flash of true understanding is superior to empty meditation.

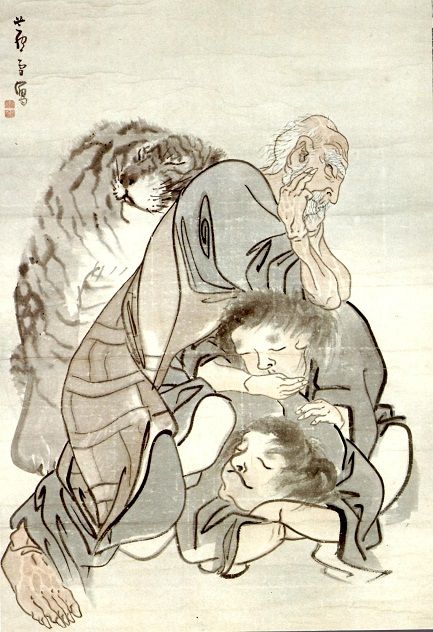

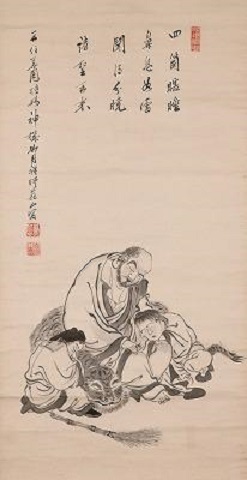

by 黙庵霊淵 Mokuan Reien (?-1345):

四睡図 Shisui (The Four Sleepers = Bukan, Kanzan, Jittoku, and the Tiger)

73.4 × 32.4 cm

Maeda Ikutokukai (前田育徳会), Tokyo

The painting bears a seal of the artist and a colophon reading as follows:

老豊干抱虎睡拾得寒山打作一處

做場大夢當風流依々老樹寒巌底

Old Feng-kan embraces his tiger and sleeps,

All huddled together with Shih-te and Han-shan

They dream their big dream, which lingers on,

While a frail old tree clings to the bottom of the cold precipice.

Shao-mu of the Hsiang-fu [temple] salutes with folded hands.

(Tr. by J. Fontein and M.L. Hickman)

Old Bukan hugging his tiger asleep

huddling together with Kanzan and Jittoku

had a dream, as though experienced the highpoint of life

lingering is the old tree clinging to the bottom of a cold rock

(Tr. by Leo Shing Chi Yip)

Kanzan Jittoku 寒山・拾得

Ch: Hanshan Shide. Semi-legendary Tang dynasty, Zen 禅 (Ch: Chan) eccentrics who were frequently depicted in Chinese and Japanese ink painting. Kanzan 寒山 (Ch: Hanshan; lit. cold mountain) is thought to have lived as a poet-recluse near Mt. Tiantai (Jp:Tendai 天台 ) in Zhejiang 浙江 . Jittoku 拾得 (Ch: Shide; lit. foundling) was so named because he was found by the Zen master Bukan 豊干 (Ch: Fenggan) and raised in the Tiantai temple Guoqingsi 国清寺, where he worked in the kitchen and gave leftover food to his friend Kanzan. The little that is known of their biographies is provided in the preface to a collection of Kanzan's poetry, Cold Mountain KANZANSHI SHISHUU 寒山子詩集 (Ch: Hanshanzishiji) and the KEITOKU DENTOUROKU 景徳伝灯録 (Ch: Jingde Chuancenglu) compiled in 1004. Kanzan Jittoku were regarded later as incarnations of the bodhisattvas Monju 文殊 (Sk: Manjusri and Fugen 普賢 (Sk: Samantabhadra), respectively. They are usually depicted with ragged clothing, long, tangled hair, and grimacing or laughing wildly. Kanzan frequently holds a scroll, presumably of his poetry although several painting inscriptions claim it is devoid of writing, while Jittoku holds a broom, indicating his position as a scullion. Along with Bukan and his pet tiger, they make up the shisui 四睡 (four sleepers).

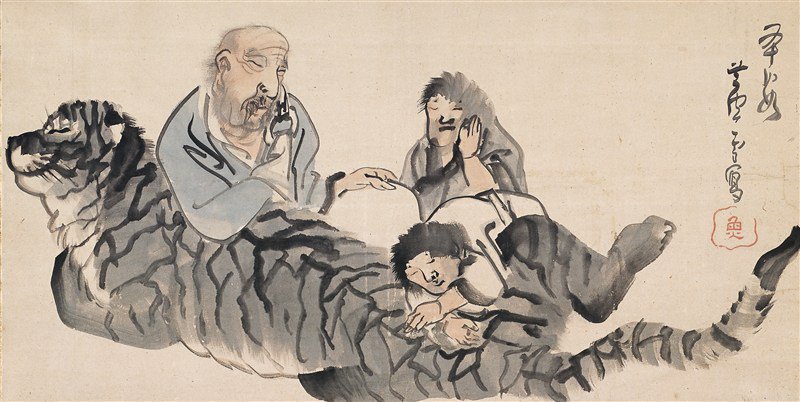

by 狩野元信 Kanō Motonobu (1476-1559)

《 四睡図 》 Shisui

(The Four Sleepers = Bukan, Kanzan, Jittoku, and the Tiger)

by 上野若元 Ueno Jakugen (1668-1744):

豊干寒山拾得図 Bukan, Kanzan, Jittoku, and the Tiger

by 狩野探幽 Kanō Tan'yū (1602-1674):

Kano Tan'yû (1602-1674), Fenggan mit dem Tiger und Drachen zwischen Wolken, Detail. Tokugawa-Zeit, datiert 1662.

Hängerollen-Triptychon, Tusche und leichte Farben auf Seide, Bildfläche je 104,5 x 54,5 cm. Museum für Asiatische Kunst. Foto: Jürgen Liepe

by 白隠慧鶴 Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1769):

豐干 Fenggan (Bukan and his Tiger)

by Suiō Genro 遂翁元盧 (1717–1789)

《四睡図》 Shisui (The Four Sleepers = Bukan, Kanzan, Jittoku, and the Tiger)

by 長沢芦雪 Nagasawa Rosetsu (1754–1799):

《四睡図》 Shisui (The Four Sleepers = Bukan, Kanzan, Jittoku, and the Tiger)

《四睡図》 Shisui (The Four Sleepers = Bukan, Kanzan, Jittoku, and the Tiger)

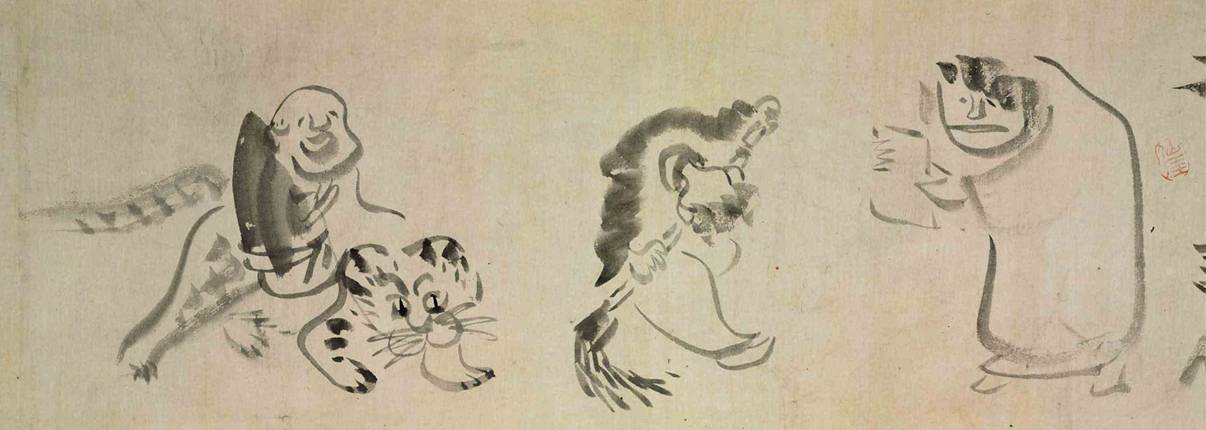

by 仙厓義梵 Sengai Gibon (1750-1837):

豐幹 Fenggan (Bukan)

by 蘇山玄喬 Sōzan Genkyō (1798-1868)

《四睡図》 Shisui (The Four Sleepers = Bukan, Kanzan, Jittoku, and the Tiger)

Ancient Chinese Sources

http://cidian.foyuan.net/list135/98/

丰干[《神僧 传》卷第六]

释丰干师者。本居天台国清寺。剪发齐眉布裘拥质。身量可七尺余。人或借问。止对曰。随时二字而已。更无他语。乐独舂谷。役同城旦。应副斋炊。尝乘虎直入松门。众僧惊惧口唱唱道歌。与拾得寒山子二人相得欢甚。丰干出云游。适闾丘胤出守台州欲之官。俄病头风召名医莫差。丰干偶至其家。自谓善疗此疾。闾丘闻而见之。师持净水噀之须臾祛殄。因是大加敬焉。问所从来。曰天台国清。曰彼有贤达否。曰寒山文殊拾得普贤。当就见之。闾丘至任。三日后即到寺。问曰。此寺曾有丰干禅师否。曰有。院在何所。寒山拾得复是何人。时僧道翘对曰。丰干旧院即经藏后。 今 阒无人止有虎豹。时来此哮吼耳。寒山拾得二人见在僧厨执役。闾丘入干房唯见虎迹纵横。又问干在此有何行业。曰唯事舂谷供僧粥食。夜则唱歌讽诵不辍。如是再三嗟叹。乃入厨见二人拜之。二人起走曰。丰干饶舌弥陀不识。礼我何为。遂携手出松门。更不复入寺焉。丰干后不知所终 。

丰干禅 师《释氏通鉴》

时丰干禅师。寒山拾得。相次垂迹于国清寺。丰干先泊于大藏西北隅庵居。因游松径。见一子。可年十岁。问之无家无姓。师引归寺库收养。号为拾得。后有一贫士。从寒巖而来。遂号为寒山子。三人相得欢甚。丰干 出云游。适 闾丘胤出守台州。欲之官。俄病头风。召名医莫瘥。丰干偶至其家。自谓善疗此疾。闾丘闻而见之。师持净水噀之。须臾祛殄。因是大加敬焉。问所从来。曰天台国清。曰彼有贤达否。曰寒山文殊。拾得普贤。当就见之。闾丘至任。三日后亲到寺。访丰干遗迹。谒二大士。寺僧引至厨间。丘拜之。二士起走曰。丰干饶舌。弥陀不识。礼我何为。遽返寒巖。次日闾丘送衣药供养。寒山见使至。喝曰贼贼。退入巖穴云。报汝诸人。各各努力。与拾得入穴。而其穴自合。寒拾有诗。散题山林间。寺僧乃集之成集。见传于世(本传 )

丰干禅 师《释氏资鉴》

天台国清寺。丰干禅 师。不知何许人。先于大藏后西北隅卓庵。因游松径。见一童子。可年十岁。问之无家无姓。师引归寺。付库司使令。号拾得。又有一士。从寒巖来。号曰寒山子。三人相会。语笑欢甚。莫测圣凡。因闾丘胤出守台州。中途俄患头风。丰干出游。偶遇之。师持净水噀之。须臾袪殄因是闾丘加拜敬。问所从来。曰天台国清丘曰。彼有贤达否。曰寒山文殊。拾得普贤。见之不识。识之不见。丘至任三日后。亲到寺。访丰干遗迹。谒二大士。僧引至厨。丘见便拜。二人起走。笑曰。丰干饶舌。弥陀不识。礼我何为。遽往寒巖。次日闾丘亲送衣药。二人见至。唱曰。贼贼。退身入巖穴云。报汝一人。各各努力其穴自合。寒拾有诗。散题山林村落。巖屋壁间。皆警世之语。闾丘遍采成集。作序偈赞传于世(弘明 )

丰干寒山拾得示 现天台《佛祖纲目》

丰干。不知何 许人。唐贞元初。居天台国清寺。剪发齐眉。衣布裘。人或问佛理。止答随时二字。尝唱道。乘虎出入。众僧惊畏。无谁语。有寒山子拾得者。亦不知其氏族。时谓风狂子。独与干相亲。寒居止唐兴县西七十里寒巖。以是得名。拾因干至赤城道侧。闻儿啼声。问之云。孤弃于此。乃名拾得。携至寺付库院后。库僧灵熠。令知食堂香灯。忽登座。与佛像对盘而餐。复于圣僧前。呼曰小果声闻。熠告尊宿等。易令厨内涤器。常日斋毕。澄滤残食菜滓。以筒盛之。寒来即负之而去。寒容貌枯瘁。布襦零落。以桦皮为冠。曳大木屐。时至寺。或廊下徐行。或厨内执爨。或 混 处童牧。或时叫噪。望空嫚骂。或云。咄哉咄哉。三界轮回僧。以杖逼逐。即抚掌大笑。一日问干。古镜不磨如何照烛。曰冰壶无影像。猿猴探水月。曰此是不照烛也。更请师道。曰万德不将来。教我道什么。寒拾俱作礼。干谓寒曰。汝与我游五台。即我同流。若不与我去。即非我同流曰我不去。干曰。汝不是我同流。寒问干。汝去五台作什么。曰我去礼文殊。曰汝不是我同流。干寻独入五台。逢一老翁。问莫是文殊否。曰岂有二文殊。及作礼。忽不见。后回天台而化。寒因众僧炙茄。以茄串打僧背一下。僧回首。寒持茄串云。是什么。僧云。这风颠汉。寒示傍僧曰。你道这个师僧费却多少盐医。赵州到天台。行见牛迹。寒曰。上座还识牛么。此是五百罗汉游山。州曰。既是罗汉。为什么作牛去。寒曰。苍天苍天。州呵呵大笑。寒曰。笑作什么。州曰。苍天苍天。寒曰。这小厮儿。却有大人之作。拾扫地。寺主问。姓个什么。住在何处。拾置帚叉手而立。主罔测。寒捶胸曰。苍天苍天。拾问。汝作什么。寒曰。岂不见道。东家人死。西家助哀。因作舞。笑哭而出。又于庄舍牧牛。歌咏叫天曰。我有一珠。埋在阴中。无人别者。众僧说戒。拾驱牛至。倚门抚掌微笑曰。悠悠哉聚头作相这个如何。僧怒呵云。下人风狂。破我说戒。拾笑曰。无嗔即 是戒。心 净即出家。我性与汝合。一切法无差。驱牛出。乃呼前世僧名。牛即应声而过。复曰。前生不持戒。人面而畜心。汝今遭此咎。怨恨于何人。佛力虽然大。汝辜于佛恩。护伽蓝神。僧厨下食。每每为乌所耗。拾杖抶之曰。汝食不能护。安能护伽蓝乎。神附梦于合寺僧曰。拾得打我。诘旦说梦。一一无差。视神像。果有所损。惊异。牒申郡县。郡谓。贤士遁迹菩萨应身。号拾得贤士。初闾丘胤。将牧丹丘。头疾。医莫能愈。遇一禅师。名丰干。言自天台来。谒使君。告之病。干曰。身居四大。病从幻生。若欲除之。应须净水。索器咒水噀之。立愈。胤异之。乞言示此去 安危之兆。干曰。 记谒文殊普贤。此二菩萨。见之不识。识之不见。若欲见之。不得取相。国清寺执爨涤器寒山拾得是也。胤到任三日。至国清问。此寺有丰干禅师否。寒山拾得复是何人。僧道翘对曰。丰干旧址。在经藏后。今阒无人矣。寒山拾得。尚处僧厨。胤入干房。止见虎迹。复问。在此作何行业。翘曰。惟事负舂供僧。閑则讽咏。入厨。寻访寒拾。见于灶前向火。抚掌大笑。胤致拜。二人连声呵叱。把手复大笑曰。丰干饶舌。丰干饶舌。弥陀不识。礼我何为。僧徒奔集。递相惊讶。何故尊官礼二贫士。时二人乃把手走出寺。胤令逐之。急走而去。即归寒巖。胤乃重问 僧曰。此二人肯止此寺否。乃令 觅访唤。归寺安置。胤遂归郡。制净衣二对。及香药等。持送供养。时二人更不返寺。使乃就巖送上。见寒山子高声喝曰。贼贼。遂入巖石缝中。且曰。报汝诸人。各各努力。石缝自合。莫可追之。其拾得迹沉无所。后有僧。采薪南峰。距寺东南二里。遇一梵僧持锡入巖。挑锁子骨曰。取拾得舍利。乃知入灭于此。因号巖为拾得。胤令道翘。寻访遗迹。于林间叶上。得寒山所书辞颂。及村墅人家三百余首。拾亦有诗数十首。题土地堂石壁间。纂集成卷 。

大宋天台·《四睡戏题》南宋·林希逸 1193~1271

http://www.ttwhg.com/appnewsShow.asp?dataID=710

![]()

Feng-kan (egyszerűsített kínai: 丰干; hagyományos kínai: 豐干; pinyin: Fēnggān; magyar népszerű: Feng-kan; japánul: Bukan; kb. 9. század) a Tang-dinasztia második felében élt csan-buddhista szerzetes, költő. Han-san és Si-tö mestere, ők együtt alkotják „a tientaj-i három szent” (Tientaj szan-seng 天台三聖) csoportját.

Életével kapcsolatban semmilyen hitelt érdemlő forrással nem rendelkezünk. Annyit lehet tudni róla, hogy a remete-költő Han-san barátja volt, illetve ő talált rá Si-tö re (Lelenc), akit aztán magával vitt a kolostorba. Feltehetően hármuk közül ő lehetett a legidősebb, Si-tö és Han-san is úgy hivatkoznak rá, mint mesterükre. A Tang-kor összes verse (Csüan Tang si 全唐詩) című antológiában versei előtt a következő rövid életrajza olvasható:

豐幹禪師,居天臺山國清寺。晝則舂米供僧,夜則扃房吟詠。一日騎虎松徑來,入國清巡廊唱道,眾皆驚怖。嘗於京輦為閭丘太守救疾,閭丘之任臺州,便至國清問豐幹禪院所在,雲在經藏後,無人住得。每有一虎,時來此吼。閭丘至師院,開房惟見虎跡。今存房中壁上詩二首。

„Feng-kan csan mester a Tientaj hegyen, a Kuo-csing kolostorban nappal közönséges, rizsen élő szerzetes volt, éjjel pedig bereteszelt ajtaja mögött dúdolgatott. Egy nap tigrisen lovagolva fenyvesek ösvényén érkezett Kuo-csingbe, végigjárva a sétányokat prédikált. Mindenki nagyon megijedt. Egyszer a fővárosban, az udvarban kigyógyította Lü-csiu helytartót betegségéből. Mikor Lü-csiut kinevezték Tajcsouba, meglátogatta a Kuo-csing kolostort, s érdeklődött, merre van Feng-kan csan mester lakása? Mondták, hogy a szútrák raktára mögött, nem embernek való helyen. Mindig van egy tigris, mely időnként arra jár és bömböl. Lü-csiu megérkezvén oda benyitott, de csak tigrisnyomokat látott. A szobában a falon máig fennmaradt két verse.”

(Csongor Barnabás fordítása)

Már az életrajzból is kiderül, 「壁上詩二首」 mindössze két verse maradt fenn. Az első egyfajta önéletrajz, amelyben nem csak két társáról tesz említést, de minden mondatából átsüt a csan-buddhizmus szellemisége:

餘自來天臺,凡經幾萬回。一身如雲水,悠悠任去來。

逍遙絕無鬧,忘機隆佛道。世途岐路心,眾生多煩惱。

兀兀沈浪海,漂漂輪三界。可惜一靈物,無始被境埋。

電光瞥然起,生死紛塵埃。寒山特相訪,拾得常往來。

論心話明月,太虛廓無礙。法界即無邊,一法普遍該。Egymagam jöttem a Tientaj hegyre,

Vagy tízezernyi utat megtettem.

Egész éltem, mint fellegek s vizek:

Jövök és megyek a végtelenben.

Kötelmek nélkül nem nyüzsgök soha,

Megbékélten járom Buddha útját,

Míg görbe, világi útra vágyók

Seregét bosszúsan gondok nyúzzák.

Kábán süllyednek hullám-tengerbe,

Három világban forognak egyre.

Be szánalmasak e "szellem lények",

Határolt mindnek léte, végzete.

Fényesség szemhunyás alatt támad,

Élet s halál mégis porral fedett.

Csak Han-sannal látogatjuk egymást,

S gyakorta Si-tö is felkereshet.

Beszélünk szívről, szólunk a Holdról,

A hatalmas Űrről: mily végtelen.

A Dharmadhátunak sincs határa,

Az egyetlen Tan mindenhol éljen!

(Tokaji Zsolt fordítása)

A második, egy négy soros költemény, amely az úgy nevezett 5 szótagos „csonkavers” (csüe-csü) formában született, a csan-buddhizmus egyik legismertebb költeményére, Huj-neng, a hatodik pátriárka versére hajaz:

本來無一物,亦無塵可拂。若能了達此,不用坐兀兀。

Valójában nem létezik semmi,

Nincs por sem, mit le kéne seperni.

Ha képes lennél fölfogni mindezt:

Mért ücsörögnél mélán merengni?

(Tokaji Zsolt fordítása)

Ta-csien Huj-neng (638–713) verse így szól:

A megvilágosulásnak nincsen fája,

A tükörnek is üres az állványa.

A buddha-természet tiszta mindenkor,

Vajon hová rakódjon a por?

(Terebess Gábor fordítása)

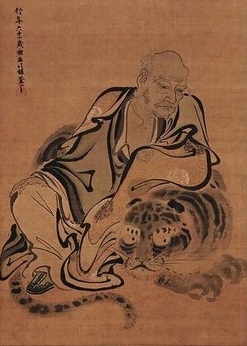

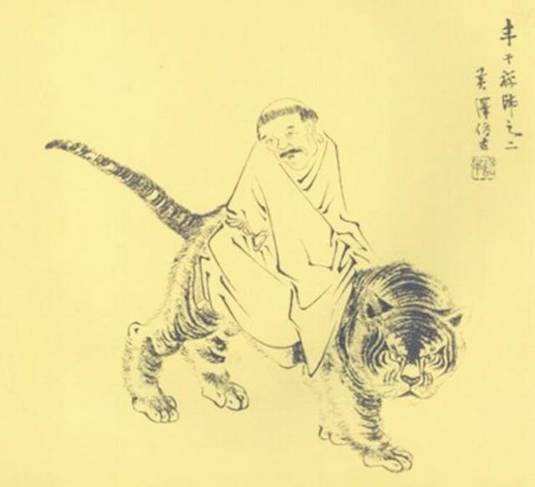

豐幹禪師 Fenggan chan master. Sketches by 黃澤 Huangze (1924)

![]()

Gedichte vom Kalten Berg

Übers. von Stephan Schuhmacher

Arbor Verlag 2001

Wie viele Myriaden Kreisläufe habe ich wohl durchlaufen,

Seit ich einst hier zu Tiantai kam?

Mein Körper ist wie Wolken und Wasser

Zu endlosem Kommen und Gehen bestimmt.

Wandernd in Muße, mit vollkommener Gelassenheit,

In Frieden mit der Welt - erhaben ist der Buddha-Weg.

Der Welt Geschäfte führn deinen Sinn auf Irrwege -

Wie tief verstrickt sind alle Lebewesen in Sinnliche Begierde!

Gluck-Gluck! versinken sie im Ozean der Ausschweifung,

Haltlos getrieben, kreisen sie durch die Drei Welten.

O welch ein Jammer, dass ihr eines Wahres Wesen

Seit undenklicher Zeit vom Wahn begraben liegt!

Plötzliches Gleißen eines Blitzstrahls lässt erkennen:

Leben und Tod sind nichts als wirbelnder Staub.

Manchmal macht sich Hanshan auf und kommt mich besuchen,

Und auch Shide der kommt und geht, wie`s ihm gefällt.

Erörtern wir den Menschengeist, dann sprechen wir vom hellen Mond,

Der Weltenraum - offene Weite ohne Hindernis.

Die Dharma-Welt hat keine Grenzen,

Allüberall herrscht das Eine Gesetz.

Übers. von Volker Doormann

Ich bin vielleicht eine Millionen Mal

nach Tientai gekommen

wie eine Wolke oder ein Fluss

hin und herströmt,

umherwandernd ohne Sorgen,

vertrauend dem weiten Pfad des Buddhas,

während der gespaltene Verstand der Welt

den Menschen nur Schmerzen bringt.

Versinkend wie ein Felsen im Meer,

getrieben durch die drei Welten,

arme ätherische Wesen,

für immer verstrickt in Kulissen,

bis ein heller Blitz Dir zeigt:.

Leben und Tod ist nur Staub im All.

Wann immer Han-Shan mich besucht

oder Shih-te einen Besuch macht,

sprechen wir über den Verstand,

oder den weiten Raum.

Wirklichkeit hat keine Grenzen;

Alles Wirkliche enthält alles.