ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

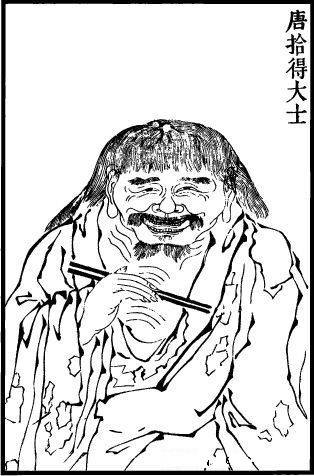

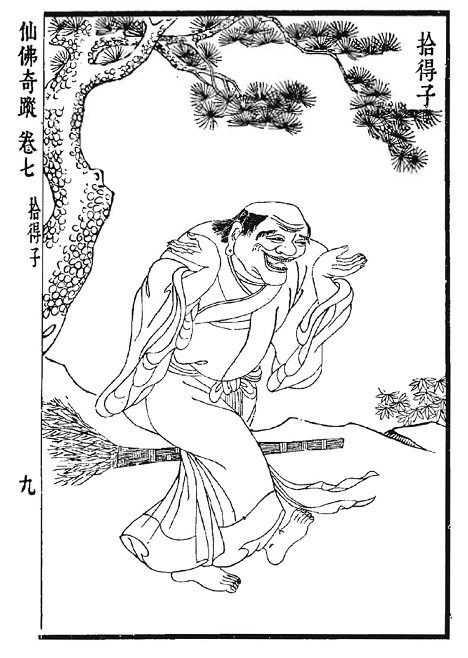

拾得 Shide (active 627-649)

(Rōmaji:) Jittoku

(English:) "Pick-up or Foundling"

(Magyar:) Si-tö, „Lelenc”

Comparative List of Shide's Poems in Chinese and English

项楚 Xiang Chu. 寒山诗注 (附拾得诗注) Cold Mountain Poems and Notes, 中华书局出版 Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing, 1997, 2000, 2010. [313 Cold Mountain Poems, 57 Pick-up Poems, 6 Big-stick Poems]

![]()

![]()

Shide in English

寒山拾得 Hanshan & Shide stonerubbing > HanshanA Dialogue Between Han-Shan and Shih-tê

Translated by Saddhaloka BhikkhuShité

Translated by R. H. BlythThe Poems of Big Stick and Pickup: From Temple Walls, Translated by Red Pine (Bill Porter). Empty Bowl, Port Townsend, 1984

PDF: Hanshan, The collected songs of Cold Mountain, Translated by Red Pine (Bill Porter). Introduction by John Blofeld. Port Townsend, Washington, Copper Canyon Press, 1983; Revised and expanded edition, 2000. Text in Chinese and English, 272 p.

The Poems of Pickup (Shih-te), pp. 265-299.

The Poetry of Shih-te

Translations by James M. HargettThe Foundling's Poems - Poems of Master Shih Te

Translated by J. P. SeatonPDF: Cold Mountain Poems: Zen Poems of Han Shan, Shih Te, and Wang Fan-chih, Tr. J.P. Seaton, Shambhala, 2009, 136 p.

James Hugh Sanford – Jerome P. Seaton. „Four Poems by Shih-te.” White Pine Journal 24-25 (1980): pp. 9-10.

The View from Cold Mountain: Poems of Han-Shan and Shih-Te, Tr. by Arthur Tobias, James Sanford and J.P. Seaton; edited by Dennis Maloney, Buffalo, N.Y.: White Pine Press, 1982, [38] p.

Cf. in:

PDF: A Drifting Boat: An Anthology of Chinese Zen Poetry edited by Jerome P. Seaton & Dennis Maloney, White Pine Press, Fredonia, New York, 1994, pp. 36-39.James Hugh Sanford – Jerome P. Seaton. Translations of two poems by Shih-te and three sets of Shih-te harmony poems. The Literaly Review. Vol. 38, No. 3 (1995), pp. 376; 335-337.

Cold Mountain Transcendental Poetry by the T'ang Zen Poet Han-shan: 100 poems translated by “Wandering Poet, M.A.” (Kindle Edition)

Han-shan and Shih-tê

Chapter XIV/26. In: The Golden Age of Zen

by John C. H. Wu

Taipei : The National War College in co-operation with The Committee on the Compilation of the Chinese Library, 1967, pp. 277-281.PDF: Wandering Saints : Chan eccentrics in the Art and Culture of Song and Yuan China by Paramita Paul

Thesis/dissertation, Proefschrift Universiteit Leiden. 2009, 310 p.The poetry of Hanshan (Cold Mountain), Shide, and Fenggan; edited by Christopher Nugent; translated by Paul Rouzer. Parallel text in Chinese and English. Boston; Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2017, 403 p.

Open access (OA): https://www.degruyter.com/viewbooktoc/product/449925PDF: The Cold Mountain Master Poetry Collection: Introduction

PDF: Record of Shide, pp. 341-351.

PDF: Shide's Poems, pp. 352-403.

—Attributed to Shide

Translation by James H. Sanford

Pacific World Journal, Third Series Number 8, Fall 2006

云林最幽栖,傍涧枕月谿。松拂盘陀石,甘泉涌凄凄。

静坐偏佳丽,虚岩曚雾迷。怡然居憩地,日斜樹影低。

In a hidden lair, in these clouded woods

I lay my head beside a moonlit stream.

Pine boughs brush the great, flat stone

sweet springs reach up, gentle, chill.

I sit, motionless, before such beauty,

lost in the misted darkness of empty hills.

I am content in this desolate spot

pine shadow, stretching before a setting sun.

Shité

Translated by R. H. Blyth

Zen and Zen Classics , Volume 2: History of Zen. The Hokuseido Press, 1964. pp. 159-160.

Hanshan is of himself Hanshan;

Shite is of himself Shite.

How can the common or garden man really know them?

(But Feng knows them through and through.)

If you want really to see them you mustn't just look at them.

When you want to find them, where will you seek for them?

I ask, "What is the relation between them?"

And hasten to answer, "They are men with the omnipotence of doing 'nothing.' "

拾得 Shide by 王問 Wang Wen (1497-1576)

THE POETRY OF SHIH-TE

Translations by James M. Hargett

Vajra Bodhi Sea, March-April-May 1975, Volume V, Series 12, Nos. 60, 61, 62 (Ten poems)

http://www.drbachinese.org/vbs/1_100/vbs60-62/poetry.html

Cf. Sunflower Splendor: Three Thousand Years of Chinese Poetry, Indiana University Press, 1990, p. 91. (Four poems)

Far, faraway, steep mountain paths,

Treacherous and narrow, ten thousand feet up;

Over boulders and bridges, lichens of green,

Whiteclouds are often seen soaring.

A cascade suspends in mid-air like a bolt of silk;

The moon's reflection falls on a deep pool, glittering.

I shall climb up the magnificent mountain peak,

to await the arrival of a solitary crane.

BIOGRAPHICAL INTRODUCTION

Shih-te is a pseudonym for an eremitic Buddhist poet who lived during the T'ang Dynasty (618-907 A.D.). He is reputed to have lived near a place called Han-shan, which is located in the southern portion of modern day Chekiang Province. His name is often associated with two Buddhist monks named Han-shan and Feng-kan with whom he was friendly, and who came from the Kuo-ch'ing Monastery.

Strictly speaking, we know very little about the life of Shih-te. Only legends have been associated with his life, and there is no preface to his collection of poems. His poems are all untitled, and contain very little biographical information.

Buddhist influence upon the poetry of Shih-te was overwhelming, and this is realized as soon as one reads a few selections of his poems. He was a follower of the Southern School of the Ch'an sect, which placed great emphasis upon individual effort. Many of the images and terminology one encounters in his poetry are drawn from Buddhist sutras or the sayings of the Southern School of Ch'an. This sect contends that the doctrine of the Buddha is present within the hearts of all men, they need only be awakened to its presence.

The majority of Shih-te's poems are either vehement denunciations of the evils of mortal men, or Buddhist sermons calling upon these unenlightened mortals to mend their evil ways and awaken to the Buddha. Most of his poems are written in the Old Style form, usually of eight lines with rhymes falling on the even numbered lines.

1.

I am aware of those foolish fellows,

Who support Sumeru with their illumed hearts. 1

Like ants gnawing on a huge tree,

How can they know their strength is so slight?

Learning to gnaw on two stalks of herbs,

Their words then become one with the Buddha.

I desperately seek to confess my sins,

Hereafter, never again to go astray.

1 Sumeru is the central peak in the Buddhist universe.

2.

My left hand clasps the Dragon Pearl, 1

My right hand clasps the Wisdom Sword. 2

First I smite an ignorant thief,

The Sacred Pearl then emits a brilliant glow,

Oh, how I grieve for those foolish fellows,

Who long for that life' of boredom.

Once they fall into the Three Evil Paths, 3

They'll sense the peril of their future course.

1 T he Dragon Pearl supposedly is one which is held beneath the chin of a dragon. A full account of this tale is related in the Chuang Tzu , chapter entitled " Lieh Yu K'ou ."

2 "The Wisdom Sword is a Buddhist term which refers to a sword which can cut away illusion.

3 That is, the hells, the realm of the hungry ghosts, and the realm of animals.

3.

You have acquired this segmented torso,

How amusing is its magnificent form.

Though the face is like a silver platter,

Within the heart it is black as lacquer.

You boil swine and butcher sheep,

Then boast by saying they are sweet as honey.

But after death when criticism falls upon you,

Do not call them false charges!

4.

Oh, to see the people in the world,

Eternally suffering upon the wayward path.

Those unable to comprehend each thought,

Their actions only lead to bitter suffering.

5.

My poems are indeed poems,

Some people call them chants,

But poems and chants are one in the same,

Readers must only examine them carefully.

But if you carefully search and inquire,

You can't discover life's easiness.

It's similar to learning proper conduct,

Surely it's an amusing affair!

6.

There are a myriad of different chants,

To quickly recite them must surely be difficult.

If you wish to be among those who know them,

You need only to come to the T'ien T'ai Mountains

There to sit among secluded grottoes,

Expounding theories, discussing the profound.

If it happens that we do not meet,

It will seem like a thousand mountains between us.

7.

Of course, Han-shan is Han-shan,

And Shih-te is Shih-te.

How can common fools recognize us?

Though Feng-kan, he surely knows us.

When worldlings wish to see us they can't,

When looking for us where can they look?

What, may I ask, is the reason for all this?

It's because we face the Tao with the power of transcendence.

8.

The steelyard reinforced with silver stars,

Its handle woven with emerald silk.

Buyers crowd up to the front,

Sellers crowd back to the rear.

Unconcerned for others' grieving hearts,

All they say is, "I'm a clever fellow."

At death, you'll depart to see the Yama, 1

Your broom, to be placed behind your back! 2

1 Yama is the king of hell.

2 A broom was used in preparing for funeral services.

9.

Often you delight in the Three Poisonous Wines, 1

Then you become confused, your senses lost.

You use money to transact imaginary affairs,

Yet these fantasies have become reality to you.

Your sufferings only lead to further sufferings,

Though you renounce them, there is no escape.

You must quickly become awakened,

But this depends on you alone!

1 These are the source of all passion and delusion. They represent in part the ideas of love, hate, and moral inertia.

10.

Carefree are those in the secular world,

Often delighting in its sensual pleasures.

When I see these fellows,

My heart bears much concern.

And why pray tell, do I grieve for them?

I think of their suffering in that world!

Hanshan & Shide, ca. 1763

by Itō Jakuchū (伊藤 若冲, 1716-1800)

The Foundling’s Poems

Poems of Master Shih Te

In: Cold Mountain Poems: Zen Poems of Han Shan, Shih Te, and Wang Fan-chih,

Translated by J.P. Seaton, Shambhala, 2009, pp. 73-85.

I

If you want to be happy,

there is no way but the hermit’s.

Flowers in the grove grow in an endless brocade;

every single season’s colors new.

Just sit beside the cliff and turn your head,

to watch the moon roll by.

And me? I ought to be at joyous ease,

but I can’t stop thinking of the others.

II

When I was young I studied books and swordsmanship

and rode off with a shout to the Capital.

There I heard the barbarians

had all been driven off already . . .

There was no place left for heroes.

So I came back to these crested peaks,

lay down to listen to the clear stream’s flow.

Young men dream of glory:

monkeys riding on the ox’s back.

III

I’ve always been Shih Te, the Foundling.

It’s not some accidental title.

Yet I’m not without a family.

Han Shan’s my brother.

Two men with hearts a lot alike.

No need for vulgar love.

If you want to know how old we are . . .

like the Yellow River, that’s unclear.

IV

You want to learn to catch a mouse?

Don’t take a pampered cat for your teacher.

If you want to learn the nature of the world,

don’t study fine bound books.

The True Jewel’s in a coarse bag.

The Buddha Nature stops at huts.

The whole herd of folks who clutch

at the outsides of things

never seem to make that connection.

V

My poems are poems,

even if some people call them sermons.

Well, poems and sermons do share one thing;

when you read them you got to be careful.

Keep at it. Get into detail.

Don’t just claim they’re easy.

If you were to live your life like that,

a lot of funny things might happen.

VI

I’m free in this cave on T’ien-t’ai:

no seeker here will ever find me.

Han Shan’s my only friend.

Chewing magic mushrooms,

underneath tall pines,

we chatter back and forth

of ancient times, and new,

sighing to think of all the others,

each on his own way to hell.

Get your heads out, there’s still time!

VII

Greed, anger, ignorance: drink deep

these poisoned wines and lie

drunk and in darkness, unknowing . . .

Make riches your dream: your dream’s

a cage of gold. Bitterness is cause of bitterness;

give it up, or dwell within that dream.

You better wake up soon, wake up

and go home.

VIII

A long way off, I see men in the dirt,

enjoying whatever it is that they find in the dirt . . .

When I look at them there in the dirt,

my heart wells full of sadness.

Why sympathize with men like these?

I can remember the taste of that dirt.

IX

Wisdom’s wine’s cold water, pure.

Drink deep, it sobers you.

Where I live, at T’ien-t’ai mountain’s side

no silly fools will ever find me.

I roam in every shady valley,

but never where the world goes.

No worry, no grief,

no shame, and no glory.

X

Since I came home to this T’ien-t’ai temple,

how many winters and springs have passed?

The mountains, the streams, they haven’t changed,

but the man’s grown older.

How many other men will stand here,

and find these mountains standing?

XI

I see a lot of silly folks

who claim their own small spine’s

Sumeru, the sacred mountain

that supports the universe.

Piss ants, gnawing away at a noble tree,

with never a doubt about their strength.

They chew up a couple of Sutras,

and pass themselves off as Masters.

Let them hurry and repent.

From now on no more foolishness.

XII

See the moon’s bright blaze of light,

a guiding lamp, above the world!

Glittering, it hangs against the void,

a blazing jewel, its brightness through the mist.

Some people say it waxes, wanes;

theirs may, but mine remains

as steady as the Mani Pearl . . .

This light knows neither day or night.

XIII

The Buddhas left their Sutras,

just because men are so hard to change.

It’s not just a matter of saintly or stupid,

each and every heart throws up a barricade,

each piles up his own mountain of karma.

How could they guess

that every single thing

they clutch so close is sorrow?

Unwilling to ponder, day and night,

as they embrace the falsehood that is flesh.

XIV

Sermons? There must be a million.

Too many to read in a hurry . . .

But if you want a friend,

just come on out to T’ien-t’ai.

Sitting deep among the crags,

we’ll talk about True Principles

and chat about Dark Mysteries.

If you don’t come to my mountain,

your view will be blocked

by all of the others.

XV

Han Shan’s Han Shan.

Me, I’m Shih Te:

How could the ignorant know us?

Old Feng Kan, he thought he knew,

but when he looked, he couldn’t see,

and where he searched, he couldn’t find us.

You want to know how that could be?

In our way’s the power of nonbeing.

XVI

I laugh at myself, old man, with no strength left,

inclined to piney peaks, in love with lonely pathways . . .

Oh well, I’ve wandered down the years to now,

free in the flow, and floated home the same,

a drifting boat.

XVII

Not going, not coming,

rooted, deep and still,

not reaching out, not reaching in,

just resting, at the center.

The single jewel, the flawless crystal drop,

in the blaze of its brilliance,

the way beyond.

XVIII

Cloudy mountains, fold on fold,

how many thousands of them?

Shady valley road runs deep,

all trace of man gone.

Green torrent’s pure clear flow,

no place more full of beauty:

and time, and time, birds sing,

my own heart’s harmony.

XIX

Now your modern day monk’s

fond of preaching of love: hard-core fool.

He starts out in search of getting free

and ends up somebody’s lackey,

morning to evening one mean hut to the next

praying and chanting for cash . . .

He makes a bundle, then drinks it up

like any other shop-boy.

XX

Far, so far, the mountain path is steep.

Thousands of feet up, the pass is dangerous and narrow.

On the stone bridge, moss and lichen . . .

from time to time, a sliver of cloud flying . . .

and cascades hanging, skeins of silk.

Image of the moon from the deep pool, shining,

once more to the top of Flowering Peak,

there waiting, still

the coming of the solitary crane.

Cold Mountain Transcendental Poetry

100 poems translated by “Wandering Poet, M.A.”

Kindle Edition

The poems attributed to Pick-up:

[10]

There are ten million scriptures

Anxious to learn you will not understand

If you want a friend and confidant

Go into Tien Tai mountains

Sit deep among the cliffs

We can discuss the ten million scriptures

But don't look for me

All you will see is a thousand mountains[16]

Pick-up is really a pick-up

It's not just a casual name

There is no close family

Cold Mountain is my brother

Our two hearts are alike

We can discuss everything together

If you ask how many years?

Since the Yellow River ran clear[23]

I laugh at myself, an old man with faded health

I'm still partial to pine cliffs, I love to play alone

I sigh for the years that are gone

Following my karma, drifting like an untied boat[32]

I wander into Cold Mountain cave

To visit someone people don't know

Cold Mountain is my friend

We chew magic mushrooms beneath the pines

We talk of current and ancient events

We see the world as stupid and crazy

Each and every one is hell bound

Will they ever be free?[37]

Tier upon tier of mountains and clouds

Beyond the trails where men tread

The pure emerald stream holds many sights

And the bird song always agrees with my heart[39]

If you discuss happiness forever

It only happens to hermits

Forest flowers shine like silk

The four seasons’ colors are always new

Leaning against the rock I sit

Gazing at the moon

Though I am happy here

I think of the miserable world down below[45]

The teachings of the old ones are like cold wine

The more you drink the clearer your mind

I live on Cold Mountain

Not even the shadow of a fool will you find here

I wander among caves and deep gorges

I don't keep up with worldly affairs

I have no worries, no concerns

I live far beyond shame and glory[48]

The higher the trail the steeper it grows

Ten thousand tiers of dangerous cliffs

The stone bridge is slippery with green moss

Cloud after cloud keeps flying by

Waterfalls hang like ribbons of silk

The moon shines down on a bright pool

I climb the highest peak once more

To wait where the lone crane flies[49]

A cold moon rises through the pines

Layer upon layer of bright clouds

Tier on tier of towering peaks

You can see a thousand miles

Pools of water crystal clear

Moonlight shining in the mirror

This precious Mountain Temple

Even the Seven Treasures cannot compare

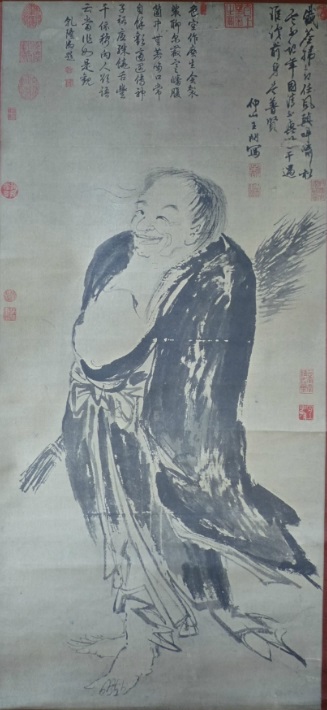

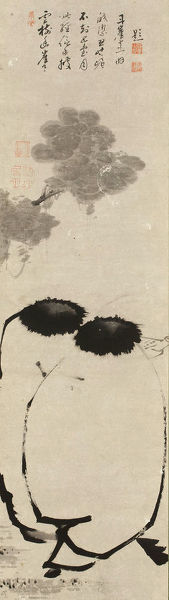

Hanshan and Shide by Liang Kai (early 13th century)

Han-shan and Shih-tê

Chapter XIV/26. In: The Golden Age of Zen

by John C. H. Wu

Taipei : The National War College in co-operation with The Committee on the Compilation of the Chinese Library, 1967, pp. 277-281.

One of the most cherished poems of the T’ang dynasty was a quatrain by Chang Chi (from latter part of the 8th century) on “A Night Mooning at Maple Bridge”:

The moon has gone down,

A crow caws through the frost.

A sorrow-ridden sleep under the shadows

Of maple trees and fishermen’s fires.

Suddenly the midnight bell of Cold Mountain Temple

Sends its echoes from beyond the city to a passing boat.

This poem is redolent of Zen. It seems as though eternity had suddenly invaded the realm of time.

The Cold Mountain Temple in the suburbs of Soochow was built in memory of Han-shan Tzu or the “Sage of Cold Mountain,” a legendary figure who is supposed to have lived in the 7th century as a hermit in the neighborhood of Kuo-ch’ing Temple on the T’ien-t’ai Mountain in Chekiang. He was not a monk, nor yet a layman; he was just himself. He found a bosom friend in the person of Shih-tê, who served in the kitchen of Kuoch’ing Temple. After every meal Han-shan would come to the kitchen to feed upon the leftovers. Then the two inseparable friends would chat and laugh. To the monks of the temple, they were just two fools. One day, as Shih-tê was sweeping the ground, an old monk said to him, “You were named Shih-te’ (literally ‘picked up’), because you were picked up by Feng-kan. But tell me what is your real family name?” Shih-te laid down his sweeper, and stood quietly with his hands crossed. When the old monk repeated his question, Shih-te took up his sweeper and went away sweeping. Han-shan struck his breast, saying, “Heaven, heaven!” Shih-te asked what he was doing. Han-shan said, “Don’t you know that when the eastern neighbor has died, the western neighbor must attend his funeral?” Then the two danced together, laughing and weeping as they went out of the temple.

At a mid-monthly renewal of vows, Shih-tê suddenly clapped his hands, saying, “You are gathered here for meditation. What about that thing?” The leader of the community angrily told him to shut up. Shih-tê said, “Please control yourself and listen to me:

The elimination of anger is true shila.

Purity of heart is true homelessness.

My self-nature and yours are one,

The fountain of all the right dharmas!”

Both Han-shan and Shih-tê were poets. I will give a sample of Shih-tê’s poetry here:

I was from the beginning a “pick up,”

It is not by accident that I am called ‘Shih-tê.'

I have no kith and kin, only Han-shan

Is my elder brother.

We are one in heart and mind:

How can we compromise with the world?

Do you wish to know our age? More than once

Have we seen the Yellow River in its pure limpidity!

Everybody knows that the Yellow River had never been limpid since the beginning of history. So the last two lines were meant to convey that they were older than the world! Another noteworthy point in this poem is that even hermits— and Hanshan and Shih-tê are among the greatest hermits of China— have need of like-minded friends for mutual encouragement and consolation. This is what keeps them so perfectly human.

From the poems of Han-shan, you will see that he is even more human than Shih-tê. There were moments when he felt intensely lonely and homesick. As he so candidly confessed:

Sitting alone I am sometimes overcome

By vague feelings of sadness and unrest.

Sometimes he thought nostalgically of his brothers:

Last year, when I heard the spring birds sing,

I thought of my brothers at home.

This year when I see the autumn chrysanthemums fade,

The same thought comes back to me.

Green waters sob in a thousand streams,

Dark clouds hang on every side.

Up to the end of my life, though I live a hundred years,

It will break my heart to think of Ch’ang-an.

This is not the voice of a man without human affection. If he preferred to live as a hermit, it was because he was driven by a mysterious impulse to find something infinitely more precious than the world could give. Here is his poem on “The Priceless Pearl.”

Formerly, I was extremely poor and miserable.

Every night I counted the treasures of others.

But today I have thought the matter over,

And decided to build a house of my own.

Digging at the ground I have found a hidden treasure—

A pearl as pure and clear as crystal!

A number of blue-eyed traders from the West

Have conspired together to buy the pearl from me.

In reply I have said to them,

“This pearl is without a price!”

His interior landscape can be glimpsed from a well-known gatha of his:

My mind is like the autumn moon, under which

The green pond appears so limpid, bright and pure.

In fact, all analogies and comparisons are inapt.

In what words can I describe it?

With such interior landscape, it is little wonder that he should be so intensely in love with nature, for nature alone could reflect the inner vision with a certain adequacy. Some of his nature poems shed a spirit of ethereal delight. For example, this:

The winter has gone and with it a dismal year.

Spring has come bringing fresh colors to all things.

Mountain flowers smile in the clear pools.

Perennial trees dance in the blue mist.

Bees and butterflies are alive with pleasure.

Birds and fishes delight me with their happiness.

Oh the wondrous joy of endless comradeship!

From dusk to dawn I could not close my eyes.

Only the man of Tao, the truly detached man, can enjoy the beauties of Nature as they are meant to be enjoyed. As to the others, they are too preoccupied with their own interests and purposes to enjoy the landscape of Nature. As an old lay woman called Dame Ch’en said, in a gatha she composed on seeing a crowd of woodcutters:

On the high slope and low plane,

You see none but woodcutters.

Everyone carries in his bosom

The idea of knife and axe;

How can he see the mountain flowers

Tinting the waters with patches of glorious red?

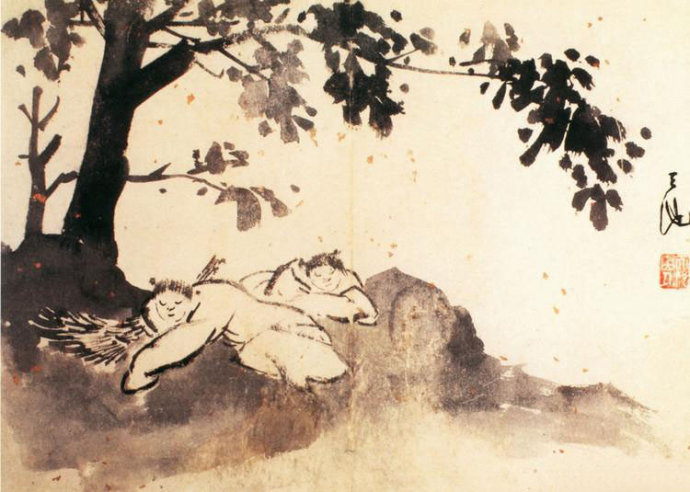

《 树下休憩图 》 "Under the Tree" by 徐渭 Xu Wei (1521-1593)

《寒山问拾得》A DIALOGUE BETWEEN HAN-SHAN AND SHIH-TÊ

From the book of the daily recitations of the Ch'an School (Ch'an men tih sung)

Translated from the Chinese by Saddhaloka Bhikkhu

Visakha Puja, Annual Publication of the Buddhist Association of Thailand, Bangkok, May 1971, pp. 64-65.

In former days Han-Shan asked Shih-tê saying: "The world is slandering me, cheating me, humiliating

me, laughing about me, treating me lightly, despising me, disliking me and swindling me. How can I

deal with this?"Shih-tê said: "Only endure it, let it be, let it have its way, avoid it, beat it, be reverent towards it, you

do not need to care for it... Wait for a few years and then have a look at it again."Han-Shan asked: "What other secret art is there to get away from it?"

Shih-tê replied: 'In the past I read the stanza of Maitreya Bodhisattva. You now listen to me. I will

recite the stanza to you: 'Old fool that I am, I wear a monk's cassock, with poor food I fill the belly. The

patched ragged garment is good enough to protect from the cold. All things follow their own conditions.

If somebody abuses this old fool, then this old fool only says 'it is well'. If anybody hits this old fool,

then this old fool will himself fall down asleep. The tears and the saliva on the face will dry by itself

and on its own.' I will also save strength and breath and he will be without defilements as well. This

kind of perfection is then the jewel within the marvel. If these tidings are known why should one

worried about not knowing the way? Man is weak and the mind is strong. Man is poor, but the way is

not poor. One ought to practise with a one-pointed mind and always act according to the way. Worldly

people love splendour, however I don't care to look at it. Fame and wealth are all void. The mind with

an 'I' is insatiable. With gold amassed in piles as big as mountains, it is difficult to buyout the limitations

due to impermanence. Tzu-Kung(1) was good in oratory. Chou-Kung(2) was endowed with the divine

reckoning. Kung-Min(3) had great wisdom in scheming. Fan-K'uai(4) rescued his lord out of difficulties.

Han-hsin's(5) efforts and toils were great and yet at the point of death it was only one swordstroke. Of

the many people of olden times and now who is there that lived for a few thousand years?This one displayed himself as a hero, that one was a brave fellow. But look, both their temples are

white. Year by year the appearance changes. Days and months are like the going to and fro of the

weaver's shuttle. Time flies like an arrow that has been shot. In no long time disease comes to encroach

upon one. With regret one grieves and laments to oneself thinking of the time when one was young and

did not take to the way of practice. But King Yama(6) does not extend the time limit set. When the

breath has come to an end just what argument is there then to take up? There's no arguing of right and

wrong, neither a discussion on family matters nor a dispute of others and me. Neither is there a brave

fellow. There is also no speech to abuse with. If one asks him it's a dumb fellow. Beat him and he

does not care either. Give him a push and the whole body will turn around. He is not afraid of being

laughed at by people nor does his face blush. Sons and daughters are sobbing, yet they do not get to see

him again. In order to contend for fame and wealth one has to take companions from the graveyard.I look at the people in the world: they are all engaged in useless things. I urge you to mend your

ways and only take to the work of practice to become a 'great man'(7) and with one swordstroke cut off

the two and jump out of the fiery pit and become a cool and pure fellow. When you awaken you will

attain to the immortal truth and the sun and the moon will be your neighbourly companions.

NOTES

1. Tzu-Kung was one of the main disciples of Confucius. His name is Tuan Mu-Tzu and he was known for his

outstanding talent of oratory.

2. Chou-Kung, that is the Duke of Chou, the son of King Wen, who was the first roles of the Chou dynasty. He

composed a commentary to the I-Ching, the Book of Changes. It is to his understanding of this book which deals with

the processes of life that the reference divine reckoning is made.

3. Kung-Ming was one of the main heroes of the period of the three kingdoms (A.D. 222-265). Known as a brilliant

tactician, strategist and planner. His name is Chu Ke-Liang and he is known to every child in China.

4. Fan-Kuai lived during the reign of Emperor Kao Tzu (A.D. 206-194) of the Han dynasty. He was originally a dog

butcher and was made a soldier by the emperor. He advanced rapidly and became threatened by a plot.

5. Han-hsin was a man of the Han dynasty too. In his youth he underwent great poverty. Later he became a

successful command or to Emperor Kao Tzu, but was executed later on being accused of treason.

6. King Yama is the King of the Underworld. Yama means twin or two in Sanskrit, because he is ruling on the one

hand with his sister and on the other hand he confers happiness or punishment by judging beings after death according

to their own deeds. He keeps records on the lives of being.

7. By a great man is meant a spiritually great man (maha-purisha).

Hanshan and Shide 寒山拾得圖

Attributed to Ma Lin 馬麟 (ca. 1180 - after 1256)

13th century, Southern Song (1127-1279)

Hanging scroll, ink on paper 91.3 x 33.6 cm

Encomium by Shiqiao Kexuan 石橋可宣 (d. ca. 1217)

Private collection

Encomium:

A thousand groves rustle in the cold of the evening wind,

Together with you, we conspire over the minutiae of all things,

Sweep the broom, sweep! Sweep the broom over and over,

The moss and the yellow leaves are suffused with the setting sun.Kexuan of Jingshan eulogises with folded hands.

千林蕭瑟晚風凉, 一事同君細較量 , 轉掃轉多多轉掃 , 青苔黃葉滿斜陽 。 徑山可宣拜賛 。

For "Hanshan & Shide" see Hanshan

Cf.

王安石 Wang An-shi (1021-1086)

Selections from

Twenty Poems in the Style of Han Shan and Shih Te

Translated by JAN W. WALLS

in: A Drifting Boat: An Anthology of Chinese Zen Poetry edited by Jerome P. Seaton & Dennis Maloney,

White Pine Press, Fredonia, New York, 1994, pp. 122-123.I.

If I were an ox or a horse

I'd rejoice over grass and beans.

If, on the other hand, I were a woman,

I'd be pleased at the sight of men.

But as long as I can be true to myself

I'll always settle for being me.

If taste and distaste keep you upset,

Surely you are being deceived:

Gentlemen, with your heads in the stars,

Don't confuse what you have with what you are!II.

I have read a million books

Seeking to learn all there is to know,

But the wise always seem to keep it to themselves,

And who would listen to the other fools!

How wonderful, to be one of the Idle Way,

Who leaps clear of each restraining clause,

Who knows that "Truth" lies deep inside the self

And never can come from someplace else.III.

Puppets are gadgets and nothing more,

None of their kind has roots to tend.

I have been behind their stage

And seen with my own eyes.

Then I discovered the audience,

All their excitement completely controlled,

Fooled by the puppets the livelong day,

Tricked into tossing their wealth away.IV.

Luck is hard to find when you're down and out,

And easy to lose once you've got it.

Pleasure is what we need after pain,

But pleasure, then, gives birth to greed.

I know neither pleasure nor pain,

I am neither enlightened nor dim.

I am not attached to Future, Past, or Now,

Nor do I try to transcend them.

JAN W. WALLS is presently completing a book of translations of the

poetry of Wang An-shih. His translations have previously appeared in

Sunflower Splendor and The Literary Review. He is the director of the

David Lam Centre for International Communications of Simon Fraser

University in Vancouver.

Comparative List of Shide's Poems

| Traditional Chinese 【 繁体 】 |

Simplified Chinese 【 简体 】 |

Official Romanization 【 拼音 】 |

English Translation by Paul Rouzer |

English Translation by Red Pine |

|

1 |

諸佛留藏經, 隻為人難化。 不唯賢與愚, 個個心構架。 造業大如山, 豈解懷憂怕。 那肯細尋思, 日夜懷奸詐。 |

诸佛留藏经, 只为人难化。 不唯贤与愚, 个个心构架。 造业大如山, 岂解怀忧怕。 那肯细寻思, 日夜怀奸诈。 |

zhū fó liú cáng jīng , zhī wéi rén nán huà 。 bù wéi xián yǔ yú , gè gè xīn gòu jià 。 zào yè dà rú shān , qǐ jiě huái yōu pà 。 nà kěn xì xún sī , rì yè huái jiān zhà 。 |

All the Buddhas have left us their scriptures Only because humans are so hard to change. Not only the worthy and the foolish— Each one of us has a deceptive heart. The karma we make is as huge as the hills, Yet we hardly know that we should worry. Never willing to look at things carefully, Day and night we embrace sin and falsehood. |

[8] Buddhas leave behind sutras because people are hard to change not just fools and scholars everyone's mind i s framed their karma high as a mountain they don't know enough to fear much less to reconsider the deceits they harbor night and day |

2 |

嗟見世間人, 個個愛吃肉。 碗碟不曾幹, 長時道不足。 昨日設個齋, 今朝宰六畜。 都緣業使牽, 非幹情所欲。 一度造天堂, 百度造地獄。 閻羅使來追, 合家盡啼哭。 爐子邊向火, 鑊子裏澡浴。 更得出頭時, 換卻汝衣服。 |

嗟见世间人, 个个爱吃肉。 碗碟不曾干, 长时道不足。 昨日设个斋, 今朝宰六畜。 都缘业使牵, 非干情所欲。 一度造天堂, 百度造地狱。 阎罗使来追, 合家尽啼哭。 炉子边向火, 镬子里澡浴。 更得出头时, 换却汝衣服。 |

jiē jiàn shì jiān rén , gè gè ài chī ròu 。 wǎn dié bù zēng gān , cháng shí dào bù zú 。 zuó rì shè gè zhāi , jīn zhāo zǎi liù xù 。 dū yuán yè shǐ qiān , fēi gān qíng suǒ yù 。 yī dù zào tiān táng , bǎi dù zào dì yù 。 yán luó shǐ lái zhuī , hé jiā jìn tí kū 。 lú zǐ biān xiàng huǒ , huò zǐ lǐ zǎo yù 。 gēng dé chū tóu shí , huàn què rǔ yī fú 。 |

I sigh to see men in the world, Each one in love with eating flesh. Their plates and bowls are never dry, Yet always they complain of dearth. Yesterday they held a feast for monks, This morning they slaughter beasts for food. All because karma drives them there— It's not what their nature desires! For every deed worthy of Heaven A hundred are worthy of Hell. Then Yama's guards will drag them off, While their families sob in mourning. They'll face the fire of furnace Hells, And they' ll bathe in their boiling pots. And just when they escape from them, They're given a new suit to wear. |

[9] Worldly people make me sigh everyone craves meat their plates and bowls are never dry they always ask for more they give a meatless feast one day then kill pigs and sheep the next they're led by their karma never by their hearts for every deed they do for Heaven they do a hundred more for Hell their whole family mourns when Yama takes them away and heats them in an oven and washes them in a cauldron until at last they emerge wearing a new set of clothes |

3 |

出家要清閑, 清閑即為貴。 如何塵外人, 卻入塵埃裏。 一向迷本心, 終朝役名利。 名利得到身, 形容已憔悴。 況復不遂者, 虛用平生誌。 可憐無事人, 未能笑得爾。 |

出家要清闲, 清闲即为贵。 如何尘外人, 却入尘埃里。 一向迷本心, 终朝役名利。 名利得到身, 形容已憔悴。 况复不遂者, 虚用平生志。 可怜无事人, 未能笑得尔。 |

chū jiā yào qīng xián , qīng xián jí wéi guì 。 rú hé chén wài rén , què rù chén āi lǐ 。 yī xiàng mí běn xīn , zhōng zhāo yì míng lì 。 míng lì dé dào shēn , xíng róng yǐ qiáo cuì 。 kuàng fù bù suì zhě , xū yòng píng shēng zhì 。 kě lián wú shì rén , wèi néng xiào dé ěr 。 |

In “leaving the home” you must be pure and calm: |

[10] People who leave home want to be free freedom is what they prize but why do those beyond the dust enter the dust once more oblivious to their own minds they work all day for profit and fame and if profit or fame should find them by then they're worn and haggard but most of the time they fail making pointless their old aim poor useless people I can't laugh at you |

4 |

養兒與娶妻, 養女求媒娉。 重重皆是業, 更殺眾生命。 聚集會親情, 總來看盤饤。 目下雖稱心, 罪簿先註定。 |

养儿与娶妻, 养女求媒娉。 重重皆是业, 更杀众生命。 聚集会亲情, 总来看盘飣。 目下虽称心, 罪簿先注定。 |

yǎng ér yǔ qǔ qī , yǎng nǚ qiú méi pīng 。 zhòng zhòng jiē shì yè , gēng shā zhòng shēng mìng 。 jù jí huì qīn qíng , zǒng lái kàn pán dìng 。 mù xià suī chēng xīn , zuì bù xiān zhù dìng 。 |

Raise a son: you find him a good wife; |

[11] A son demands a wife a daughter requires a go-between both of which mean karma and taking lives besides calling together friends and kin to come inspect the feast before your eyes it all looks fine but not in your book of crimes |

5 |

得此分段身, 可笑好形質。 面貌似銀盤, 心中黑如漆。 烹豬又宰羊, 誇道甜如蜜。 死後受波咤, 更莫稱冤屈。 |

得此分段身, 可笑好形质。 面貌似银盘, 心中黑如漆。 烹猪又宰羊, 夸道甜如蜜。 死后受波吒, 更莫称冤屈。 |

dé cǐ fēn duàn shēn , kě xiào hǎo xíng zhì 。 miàn mào sì yín pán , xīn zhōng hēi rú qī 。 pēng zhū yòu zǎi yáng , kuā dào tián rú mì 。 sǐ hòu shòu bō zhà , gēng mò chēng yuān qū 。 |

This body obtained—with its share of karma: |

[12] Take these mortal incarnations these comical-looking forms with faces like the silver moon and hearts as black as pitch cooking pigs and butchering sheep bragging about the flavor dying and going to Frozen-tongue Hell before they stop telling lies |

6 |

佛哀三界子, 總是親男女。 恐沈黑暗坑, 示儀垂化度。 盡登無上道, 俱證菩提路。 教汝癡眾生, 慧心勤覺悟。 |

佛哀三界子, 总是亲男女。 恐沈黑暗坑, 示仪垂化度。 尽登无上道, 俱证菩提路。 教汝痴众生, 慧心勤觉悟。 |

fó āi sān jiè zǐ , zǒng shì qīn nán nǚ 。 kǒng shěn hēi àn kēng , shì yí chuí huà dù 。 jìn dēng wú shàng dào , jù zhèng pú tí lù 。 jiào rǔ chī zhòng shēng , huì xīn qín jué wù 。 |

Lord Buddha laments those of the Three Realms— |

[13] Buddhas care for mortal beings as if they were their children to keep them from the dark abyss they leave signs along the way they walk down the best of paths and prove the Bodhi Road exists and tell benighted men like you to wake up to your buddha mind |

7 |

佛舍尊榮樂, 為湣諸癡子。 早願悟無生, 辦集無上事。 後來出家者, 多緣無業次。 不能得衣食, 頭鉆入於寺。 |

佛舍尊荣乐, 为愍诸痴子。 早愿悟无生, 办集无上事。 后来出家者, 多缘无业次。 不能得衣食, 头钻入于寺。 |

fó shè zūn róng lè , wéi mǐn zhū chī zǐ 。 zǎo yuàn wù wú shēng , bàn jí wú shàng shì 。 hòu lái chū jiā zhě , duō yuán wú yè cì 。 bù néng dé yī shí , tóu zuān rù yú sì 。 |

The Buddha cast aside honor, glory and pleasure, |

[14] The Buddha forsook the joys of rank because he pitied fools vowing to suffer no rebirth he performed the noblest deeds those who leave home nowadays are mostly out of work hard-pressed to earn a living they sneak inside of temples |

8 |

嗟見世間人, 永劫在迷津。 不省這個意, 修行徒苦辛。 |

嗟见世间人, 永劫在迷津。 不省这个意, 修行徒苦辛。 |

jiē jiàn shì jiān rén , yǒng jié zài mí jīn 。 bù shěng zhè gè yì , xiū xíng tú kǔ xīn 。 |

Alas, I see the people of the world: |

[15] I sigh when I see worldly people forever searching for the ford unaware of what this means their trials are in vain |

9 |

我詩也是詩, 有人喚作偈。 詩偈總一般, 讀時須子細。 緩緩細披尋, 不得生容易。 依此學修行, 大有可笑事。 |

我诗也是诗, 有人唤作偈。 诗偈总一般, 读时须子细。 缓缓细披寻, 不得生容易。 依此学修行, 大有可笑事。 |

wǒ shī yě shì shī , yǒu rén huàn zuò jì 。 shī jì zǒng yī bān , dú shí xū zǐ xì 。 huǎn huǎn xì pī xún , bù dé shēng róng yì 。 yī cǐ xué xiū xíng , dà yǒu kě xiào shì 。 |

Yes, my poems are poems— |

[16] My poems are poems alright though some call them gathas poems or gathas what's the difference readers should be careful take your time going through don't think they're so easy use them to improve yourself they'll make it much more fun |

10 |

有偈有千萬, 卒急述應難。 若要相知者, 但入天臺山。 巖中深處坐, 說理及談玄。 共我不相見, 對面似千山。 |

有偈有千万, 卒急述应难。 若要相知者, 但入天台山。 岩中深处坐, 说理及谈玄。 共我不相见, 对面似千山。 |

yǒu jì yǒu qiān wàn , zú jí shù yīng nán 。 ruò yào xiāng zhī zhě , dàn rù tiān tái shān 。 yán zhōng shēn chǔ zuò , shuō lǐ jí tán xuán 。 gòng wǒ bù xiāng jiàn , duì miàn sì qiān shān 。 |

There are millions of gāthas: |

[17] I have millions of gathas instant cures for every trouble if you need a friend try the Tientai Mountains join me deep in the cliffs we'll talk about truth and mystery you won't see me though all you'll see is mountains |

11 |

世間億萬人, 面孔不相似。 借問何因緣, 致令遣如此。 各執一般見, 互說非兼是。 但自修己身, 不要言他已。 |

世间亿万人, 面孔不相似。 借问何因缘, 致令遣如此。 各执一般见, 互说非兼是。 但自修己身, 不要言他已。 |

shì jiān yì wàn rén , miàn kǒng bù xiāng sì 。 jiè wèn hé yīn yuán , zhì líng qiǎn rú cǐ 。 gè zhí yī bān jiàn , hù shuō fēi jiān shì 。 dàn zì xiū jǐ shēn , bù yào yán tā yǐ。 |

All the billions of people in the world: |

[18] The world has billions of people and no two faces alike I wonder about the reason behind such variation and all with similar views debating who is right and wrong just correct yourself and stop maligning others |

12 |

男女為婚嫁, 俗務是常儀。 自量其事力, 何用廣張施。 取債誇人我, 論情入骨癡。 殺他雞犬命, 身死墮阿鼻。 |

男女为婚嫁, 俗务是常仪。 自量其事力, 何用广张施。 取债夸人我, 论情入骨痴。 杀他鸡犬命, 身死堕阿鼻。 |

nán nǚ wéi hūn jià , sú wù shì cháng yí 。 zì liáng qí shì lì , hé yòng guǎng zhāng shī 。 qǔ zhài kuā rén wǒ , lùn qíng rù gǔ chī 。 shā tā jī quǎn mìng , shēn sǐ duò ā bí 。 |

Men and women go off and get married, |

[19] When men and women marry custom demands a certain form each adds up their strengths but why the big display incurring debts for face dearly fools at heart taking the lives of dogs and chickens bound for the Hell of No Relief |

13 |

世上一種人, 出性常多事。 終日傍街衢, 不離諸酒肆。 為他作保見, 替他說道理。 一朝有乖張, 過咎全歸你。 |

世上一种人, 出性常多事。 终日傍街衢, 不离诸酒肆。 为他作保见, 替他说道理。 一朝有乖张, 过咎全归你。 |

shì shàng yī zhǒng rén , chū xìng cháng duō shì 。 zhōng rì bàng jiē qú , bù lí zhū jiǔ sì 。 wéi tā zuò bǎo jiàn , tì tā shuō dào lǐ 。 yī zhāo yǒu guāi zhāng , guò jiù quán guī nǐ。 |

One kind of man in the world: |

[20] There exists one type of person a meddlesome fool since birth all day at the roadside not far from a tavern give him your support speak to him of reason one day he goes too far and all his wrongs return |

14 |

我勸出家輩, 須知教法深。 專心求出離, 輒莫染貪淫。 大有俗中士, 知非不愛金。 故知君子誌, 任運聽浮沈。 |

我劝出家辈, 须知教法深。 专心求出离, 辄莫染贪淫。 大有俗中士, 知非不爱金。 故知君子志, 任运听浮沈。 |

wǒ quàn chū jiā bèi , xū zhī jiào fǎ shēn 。 zhuān xīn qiú chū lí , zhé mò rǎn tān yín 。 dà yǒu sú zhōng shì , zhī fēi bù ài jīn 。 gù zhī jūn zǐ zhì , rèn yùn tīng fú shěn 。 |

I urge those who leave the household: You must profoundly know the Teachings. Concentrate wholly on liberation, Never stain yourselves with greed or lust. There are always some laymen Who know wrong and do not cherish gold. So you should know the will of a good man: Follow fate, rise and fall with the flood. |

[21] I advise the monks I meet focus on the deeper teachings concentrate on getting free don't be destroyed by greed there are laymen by the score who know love of gold is wrong know then what a wise man seeks just let go and take what comes |

15 |

寒山住寒山, 拾得自拾得。 凡愚豈見知, 豐幹卻相識。 見時不可見, 覓時何處覓。 借問有何緣, 卻道無為力。 |

寒山住寒山, 拾得自拾得。 凡愚岂见知, 丰干却相识。 见时不可见, 觅时何处觅。 借问有何缘, 却道无为力。 |

hán shān zhù hán shān , shí dé zì shí dé 。 fán yú qǐ jiàn zhī , fēng gān què xiāng shí 。 jiàn shí bù kě jiàn , mì shí hé chǔ mì 。 jiè wèn yǒu hé yuán , què dào wú wéi lì 。 |

Cold Mountain lives on Cold Mountain; |

[22] Cold Mountain is a cold mountain and Pickup was picked up Big Stick knows our faces fools can't recognize us they don't see us when we meet when they look we aren't there if you wonder what's the reason it's the power of doing nothing |

16 |

從來是拾得, 不是偶然稱。 別無親眷屬, 寒山是我兄。 兩人心相似, 誰能徇俗情。 若問年多少, 黃河幾度清。 |

从来是拾得, 不是偶然称。 别无亲眷属, 寒山是我兄。 两人心相似, 谁能徇俗情。 若问年多少, 黄河几度清。 |

cóng lái shì shí dé , bù shì ǒu rán chēng 。 bié wú qīn juàn shǔ , hán shān shì wǒ xiōng 。 liǎng rén xīn xiāng sì , shuí néng xùn sú qíng 。 ruò wèn nián duō shǎo , huáng hé jī dù qīng 。 |

Once upon a time I was a foundling, |

[23] I was Pickup from the first no accidental name no other close relation Cold Mountain is my brother our two hearts are both alike neither can endure the herd if you want to know our ages count the times the Yellow River has cleared |

17 |

若解捉老鼠, 不在五白貓。 若能悟理性, 那由錦繡包。 真珠入席袋, 佛性止蓬茅。 一群取相漢, 用意總無交。 |

若解捉老鼠, 不在五白猫。 若能悟理性, 那由锦绣包。 真珠入席袋, 佛性止蓬茅。 一群取相汉, 用意总无交。 |

ruò jiě zhuō lǎo shǔ , bù zài wǔ bái māo 。 ruò néng wù lǐ xìng , nà yóu jǐn xiù bāo 。 zhēn zhū rù xí dài , fó xìng zhǐ péng máo 。 yī qún qǔ xiāng hàn , yòng yì zǒng wú jiāo 。 |

As for knowing how to catch a rat— |

[24] Who knows how to catch rats doesn't need five white cats and who discovers what's real doesn't need a brocade bag a pearl fits in a burlap sack buddhahood rests under thatch all you people attached to form use your minds to no avail |

18 |

運心常寬廣, 此則名為布。 輟己惠於人, 方可名為施。 後來人不知, 焉能會此義。 未設一庸僧, 早擬望富貴。 |

运心常宽广, 此则名为布。 辍己惠于人, 方可名为施。 后来人不知, 焉能会此义。 未设一庸僧, 早拟望富贵。 |

yùn xīn cháng kuān guǎng , cǐ zé míng wéi bù 。 chuò jǐ huì yú rén , fāng kě míng wéi shī 。 hòu lái rén bù zhī , yān néng huì cǐ yì 。 wèi shè yī yōng sēng , zǎo nǐ wàng fù guì 。 |

The impulse for giving should always be generous; |

[25] Keeping your mind wide-open is what we call generosity stopping your kindness to others is what benevolence means people now don't know what to make of such teachings before they're done feeding a monk they expect wealth and fame |

19 |

獼猴尚教得, 人何不憤發。 前車既落坑, 後車須改轍。 若也不知此, 恐君惡合殺。 此來是夜叉, 變即成菩薩。 |

猕猴尚教得, 人何不愤发。 前车既落坑, 后车须改辙。 若也不知此, 恐君恶合杀。 此来是夜叉, 变即成菩萨。 |

mí hóu shàng jiào dé , rén hé bù fèn fā 。 qián chē jì luò kēng , hòu chē xū gǎi zhé 。 ruò yě bù zhī cǐ , kǒng jūn è hé shā 。 cǐ lái shì yè chā , biàn jí chéng pú sà 。 |

Even a monkey can be taught, |

[26] Since monkeys can be taught why don't people begin to learn if the cart in front gets stuck why not try another track if you can't make sense of this I suspect you'll die of anger a yaksha though the other day became a bodhisattva |

20 |

自從到此天臺寺, 經今早已幾冬春。 山水不移人自老, 見卻多少後生人。 |

自从到此天台寺, 经今早已几冬春。 山水不移人自老, 见却多少后生人。 |

zì cóng dào cǐ tiān tái sì , jīng jīn zǎo yǐ jī dōng chūn 。 shān shuǐ bù yí rén zì lǎo , jiàn què duō shǎo hòu shēng rén 。 |

[45] |

[1] Since I came to Tientai Temple how many winters and springs have passed the sights haven't changed only the people all I see are youngsters |

21 |

君不見, 三界之中紛擾擾, 隻為無明不了絕。 一念不生心澄然, 無去無來不生滅。 |

君不见, 三界之中纷扰扰, 只为无明不了绝。 一念不生心澄然, 无去无来不生灭。 |

jūn bù jiàn , sān jiè zhī zhōng fēn rǎo rǎo , zhī wéi wú míng bù liǎo jué 。 yī niàn bù shēng xīn chéng rán , wú qù wú lái bù shēng miè 。 |

[20] |

[2] Doesn't anyone see the turmoil in the Three Worlds is due to endless delusion once thoughts stop the mind becomes clear nothing comes or goes neither birth nor death |

22 |

故林又斬新, 剡源溪上人。 天姥峽關嶺, 通同次海津。 灣深曲島間, 渺渺水雲雲。 借問松禪客, 日輪何處暾。 |

故林又斩新, |

gù lín yòu zhǎn xīn , yǎn yuán xī shàng rén 。 tiān mǔ xiá guān lǐng , tōng tóng cì hǎi jīn 。 wān shēn qū dǎo jiān , miǎo miǎo shuǐ yún yún 。 jiè wèn sōng chán kè , rì lún hé chǔ tūn 。 |

[21] The home forest is refreshed again For the man standing by Shan Creek's source. Tianmu Mountain: its passes, gorges, peaks Press hard upon the ocean side. In the depths of the bay, the far off isles, The vast waters lost in mist. I ask Meditation Master Song: Where is the sun that shines so dim? |

|

23 |

自笑老夫筋力敗, 偏戀松巖愛獨遊。 可嘆往年至今日, 任運還同不系舟。 |

自笑老夫筋力败, |

zì xiào lǎo fū jīn lì bài , piān liàn sōng yán ài dú yóu 。 kě tàn wǎng nián zhì jīn rì , rèn yùn huán tóng bù xì zhōu 。 |

[22] A laugh at myself, an old man with sinews powerless; But with fond affection for piney cliffs and a love of lonely rambling. What' s amazing: from former years up until today, Turning myself over to fate just like an unmoored boat. |

[27] Partial to pine cliffs and lonely trails an old man laughs at himself when he falters even now after all these years trusting the current like an unmoored boat |

24 |

一入雙溪不計春, 煉暴黃精幾許斤。 爐竈石鍋頻煮沸, 土甑久烝氣味珍。 誰來幽谷餐仙食, 獨向雲泉更勿人。 延齡壽盡招手石, 此棲終不出山門。 |

一入双溪不计春, |

yī rù shuāng xī bù jì chūn , liàn bào huáng jīng jī xǔ jīn 。 lú zào shí guō pín zhǔ fèi , tǔ zèng jiǔ zhēng qì wèi zhēn 。 shuí lái yōu gǔ cān xiān shí , dú xiàng yún quán gēng wù rén 。 yán líng shòu jìn zhāo shǒu shí , cǐ qī zhōng bù chū shān mén 。 |

[23] Once I entered Double Springs, countless years went by; There I refined and dried many a pound of Solomon's Seal. In stove and furnace, in stoneware cauldron I boiled it several times; In earthen crocks I steamed it long until vapor and taste were refined. Who comes now to my remote valley to taste this immortal food? I'm alone amid the clouds and the str eams, there's no one here at all. My long life will come to an end her e by the Beckoning Stone; Roosting here, I'll never depart the temple's mountain gate. |

|

25 |

躑躅一群羊, 沿山又入谷。 看人貪竹塞, 且遭豺狼逐。 元不出孳生, 便將充口腹。 從頭吃至尾, 饣內饣內無余肉。 |

踯躅一群羊, |

zhí zhú yī qún yáng , yán shān yòu rù gǔ 。 kàn rén tān zhú sāi , qiě zāo chái láng zhú 。 yuán bù chū zī shēng , biàn jiāng chōng kǒu fù 。 cóng tóu chī zhì wěi , shí nèi shí nèi wú yú ròu 。 |

[24] A flock of sheep is wandering about, Is following the hills and entering valleys. Their shepherd is set on his gambling games When he encounters jackals and wolves in pursuit. They wer en't raised by the wolves at all, But now they fill wolves' mouths and bellies! Devoured from their heads down to their tails, With not a leftover in sight. |

[28] A flock of timid sheep skirt the hills and keep to valleys preferring man-made pens to being chased by wolves nor do they stop multiplying until they fill someone's gut food for men from head to tail chomp chomp till nothing's left |

26 |

銀星釘稱衡, 綠絲作稱紐。 買人推向前, 賣人推向後。 不願他心怨, 唯言我好手。 死去見閻王, 背後插掃帚。 |

银星钉称衡, |

yín xīng dīng chēng héng , lǜ sī zuò chēng niǔ 。 mǎi rén tuī xiàng qián , mài rén tuī xiàng hòu 。 bù yuàn tā xīn yuàn , wéi yán wǒ hǎo shǒu 。 sǐ qù jiàn yán wáng , bèi hòu chā sǎo zhǒu 。 |

[25] Silver weights fastened from the steelyard, Green threads serve as the steelyard cord. Buyers push themselves in front, Sellers thrust themselves behind. No heed have they for the wrongs of others, Only say , “I'm pretty good at this.” After they die, they' ll see King Yama; He'll stick them with a broom-tail. |

[29] Silver stars dot the beam green silk marks the weight buyers move it forward sellers move it back never mind the other's anger just as long as you prevail when you die and meet Old Yama up your butt he'll stick a broom |

27 |

閉門私造罪, 準擬免災殃。 被他惡部童, 抄得報閻王。 縱不入鑊湯, 亦須臥鐵床。 不許雇人替, 自作自身當。 |

闭门私造罪, |

bì mén sī zào zuì , zhǔn nǐ miǎn zāi yāng 。 bèi tā è bù tóng , chāo dé bào yán wáng 。 zòng bù rù huò tāng , yì xū wò tiě chuáng 。 bù xǔ gù rén tì , zì zuò zì shēn dāng 。 |

[26] You shut the door, commit your sins in private, Intending that way to avoid calamity. But the boy who copies your evil deeds Writes it all down, reports it to Yama. Even if you don't enter the boiling cauldron, You 'll be laid out on the iron bed. You can't hire someone to take your place— Your deeds will be on your own head. |

[30] Committing crimes behind closed doors you think you won't be punished meanwhile Yama's minions prepare a full report if you escape the cauldron you'll lie on the iron rack and stand-ins aren't allowed you're the victim of your deeds |

28 |

悠悠塵裏人, 常道塵中樂。 我見塵中人, 心生多湣顧。 何哉湣此流, 念彼塵中苦。 |

悠悠尘里人, |

yōu yōu chén lǐ rén , cháng dào chén zhōng lè 。 wǒ jiàn chén zhōng rén , xīn shēng duō mǐn gù 。 hé zāi mǐn cǐ liú , niàn bǐ chén zhōng kǔ 。 |

[27] How many the people in the dust, Always talking about their dusty delights! I see these people in the dust, And so often I feel sorry for them. How can I feel sorry for people like that? I remember that there's pain in that dust as well. |

[38] People crowd by in the dust enjoying the pleasures of the dust I see them in the dust and pity fills my heart why do I pity their lot I think of their pain in the dust |

29 |

無去無來本湛然, 不居內外及中間。 一顆水精絕瑕翳, 光明透滿出人天。 |

无去无来本湛然, |

wú qù wú lái běn zhàn rán , |

[28] No goings, no comings, originally tranquil; No dw elling within or without, or at the point between. A single crystal of purity without flaw or crack; Its light penetrates and fills up the worlds of men and gods. |

[31] Not waxing or waning essentially still not inside or outside and nowhere between a single flawless crystal whose light shines through to gods and men |

30 |

少年學書劍, 叱馭到荊州。 聞伐匈奴盡, 婆娑無處遊。 歸來翠巖下, 席草玩清流。 壯士誌未騁, 獼猴騎土牛。 |

少年学书剑, |

shǎo nián xué shū jiàn , chì yù dào jīng zhōu 。 wén fá xiōng nú jìn , pó suō wú chǔ yóu 。 guī lái cuì yán xià , xí cǎo wán qīng liú 。 zhuàng shì zhì wèi chěng , mí hóu qí tǔ niú 。 |

[29] In my youth I studied books and swordsmanship; Bent on saving the state, I drove toward Jingzhou. There I heard the campaigns against the Xiongnu were done, So I lingered, aimless, no place to go. I went home again to the foot of azur e cliffs, Made grass my mat, delighted in the clear str eams. Before a man in his prime can pursue his will, He's reduced to a monkey riding a clay ox. |

[39] A young man studied letters and arms and rode off to the capital where he learned the Huns had been vanquished and all he could do was wait so to kingfisher cliffs he retired and sits in the grass by a stream while valiant men chase red cords and monkeys ride clay oxen |

31 |

三界如轉輪, 浮生若流水。 蠢蠢諸品類, 貪生不覺死。 汝看朝垂露, 能得幾時子。 |

三界如转轮, |

sān jiè rú zhuǎn lún , fú shēng ruò liú shuǐ 。 chǔn chǔn zhū pǐn lèi , tān shēng bù jué sǐ 。 rǔ kàn zhāo chuí lù , néng dé jī shí zǐ 。 |

[30] The Three Realms are like a turning wheel; This floating life like flowing water. All living beings are squirming together, Greedy for life and ignorant of death. Just look at the morning dew— How long can it last? |

[32] The Triple World is a turning wheel transient existence is a flowing stream writhing with a myriad creatures hungry for life unaware of death consider the morning dew how long does it last |

32 |

閑入天臺洞, 訪人人不知。 寒山為伴侶, 松下啖靈芝。 每談今古事, 嗟見世愚癡。 個個入地獄, 早晚出頭時。 |

闲入天台洞, |

xián rù tiān tái dòng , fǎng rén rén bù zhī 。 hán shān wéi bàn lǚ , sōng xià dàn líng zhī 。 měi tán jīn gǔ shì , jiē jiàn shì yú chī 。 gè gè rù dì yù , zǎo wǎn chū tóu shí 。 |

[31] I idly enter Tiantai grottoes To visit someone, though no one knows. Hanshan is my companion; Under the pines we dine on magic fungi. Always we chat about matters new and ancient, Sighing that the world is so foolish. One by one they enter into hell, And when will they ever get out of it? |

[33] We slip into Tientai caves we visit people unseen me and my friend Cold Mountain eat magic mushrooms under the pines we talk about the past and present and sigh at the world gone mad everyone going to Hell and going for a long long time |

33 |

古佛路淒淒, 愚人到卻迷。 隻緣前業重, 所以不能知。 欲識無為理, 心中不掛絲。 生生勤苦學, 必定睹天師。 |

古佛路凄凄, |

gǔ fó lù qī qī , yú rén dào què mí 。 zhī yuán qián yè zhòng , suǒ yǐ bù néng zhī 。 yù shí wú wéi lǐ , xīn zhōng bù guà sī 。 shēng shēng qín kǔ xué , bì dìng dǔ tiān shī 。 |

[32] The path of past Buddhas is drear and chill, Fools who come to it are lost. All because their karmic burden is heavy, They are unable to learn of it. If you want to know how to be free of karmic action, No garments may hang about your heart. From life to life study with all your might, Then you'll certainly see the Celestial Teacher. |

[34] The old buddha road is deserted fools who take it end up lost due to the depth of their karma they can't discern a thing to learn the effortless truth don't make a single distinction people who practice life after life need to see my teacher |

34 |

各有天真佛, 號之為寶王。 珠光日夜照, 玄妙卒難量。 盲人常兀兀, 那肯怕災殃。 唯貪淫泆業, 此輩實堪傷。 |

各有天真佛, |

gè yǒu tiān zhēn fó , hào zhī wéi bǎo wáng 。 zhū guāng rì yè zhào , xuán miào zú nán liáng 。 máng rén cháng wù wù , nà kěn pà zāi yāng 。 wéi tān yín yì yè , cǐ bèi shí kān shāng 。 |

[33] Each has a naturally authentic Buddha; We name it the Prince of Jewels. The light of this pearl shines day and night; Its dark mysteries impossible to measure. But the blind ar e always muddled, Unwilling to fear disaster and calamity. Only gr eedy for a karma of excess, This gang is really pitiable. |

[35] |

35 |

出家求出離, 哀念苦眾生。 助佛為揚化, 令教選路行。 何曾解救苦, 恣意亂縱橫。 一時同受溺, 俱落大深坑。 |

出家求出离, |

chū jiā qiú chū lí , āi niàn kǔ zhòng shēng 。 zhù fó wéi yáng huà , líng jiào xuǎn lù xíng 。 hé zēng jiě jiù kǔ , zī yì luàn zòng héng 。 yī shí tóng shòu nì , jù luò dà shēn kēng 。 |

[34] Those who have left their home seek escape, And think with pity of the suffering of living things. They help the Buddhas to spread the message of salvation, Causing all to choose the right path to take. But when have they ever understood how to relieve suffering? Doing as they please, wildly going in all directions. All at once they will drown together, All falling in the great deep Pit. |

[36] Those who leave home leave to be free and pity the suffering masses they proselytize for the Buddha telling others to choose a path but who can they possibly save doing whatever they please descending with everyone else into the same abyss |

36 |

常飲三毒酒, 昏昏都不知。 將錢作夢事, 夢事成鐵圍。 以苦欲舍苦, 舍苦無出期。 應須早覺悟, 覺悟自歸依。 |

常饮三毒酒, |

cháng yǐn sān dú jiǔ , hūn hūn dū bù zhī 。 jiāng qián zuò mèng shì , mèng shì chéng tiě wéi 。 yǐ kǔ yù shè kǔ , shè kǔ wú chū qī 。 yīng xū zǎo jué wù , jué wù zì guī yī 。 |

[35] Always they drink the wine of Three Poisons, Benighted, all of them unaware. Using money to pay for their dreams, Dreams that turn into an Iron Cage. With suffering they try to relieve suffering, Yet this r elief will never take place. From the start they ought to struggle to wake up— Awakening that comes from Taking Refuge. |

[37] Drunk on delusion greed and anger dazed and unaware you turn money into a dream a dream that becomes an iron jail using one pain to get rid of another you never get rid of pain unless you learn before it's too late you learn to turn to yourself |

37 |

雲山疊疊幾千重, 幽谷路深絕人蹤。 碧澗清流多勝境, 時來鳥語合人心。 |

云山叠叠几千重, |

yún shān dié dié jī qiān zhòng , yōu gǔ lù shēn jué rén zōng 。 bì jiàn qīng liú duō shèng jìng , shí lái niǎo yǔ hé rén xīn 。 |

[36] Cloudy mountains, rank upon rank, how many thousand layers! Secluded valley — the road deep, cut off from human traces. The jade stream flows clearly through a realm of many marvels; From time to time, the chattering of birds matches with my mood. |

[40] Past thousands of layers of mountains and clouds hidden remote beyond human tracks a pure stream of jade contains many sights and bird talk suddenly agrees with my thoughts |

38 |

後來出家子, 論情入骨癡。 本來求解脫, 卻見受驅馳。 終朝遊俗舍, 禮念作威儀。 博錢沽酒吃, 翻成客作兒。 |

后来出家子, |

hòu lái chū jiā zǐ , lùn qíng rù gǔ chī 。 běn lái qiú jiě tuō , què jiàn shòu qū chí 。 zhōng zhāo yóu sú shè , lǐ niàn zuò wēi yí 。 bó qián gū jiǔ chī , fān chéng kè zuò ér 。 |

[37] Monks of this latter time: To tell the truth, they're stupid to the bone. Originally they sought Liberation, But now they bustle about at the tasks they get. All day traveling to laymen's homes, Paying r espects, chanting sutras, performing rituals. They get their pay, then go drinking, Acting just like hired laborers. |

[41] Those who leave home nowadays turn out to be fools at heart at first they seek liberation then run errands instead visiting laymen all day long chanting and acting solemn earning money for wine flunkies in the end |

39 |

若論常快活, 唯有隱居人。 林花長似錦, 四季色常新。 或向巖間坐, 旋瞻見桂輪。 雖然身暢逸, 卻念世間人。 |

若论常快活, |

ruò lùn cháng kuài huó , wéi yǒu yǐn jū rén 。 lín huā cháng sì jǐn , sì jì sè cháng xīn 。 huò xiàng yán jiān zuò , xuán zhān jiàn guì lún 。 suī rán shēn chàng yì , què niàn shì jiān rén 。 |

[38] If you discuss what'll make you always happy, There 's only the life of the recluse. The trees in flower are always like brocade; In all four seasons, their colors are ever renewed. Sometimes I sit on the cliffs, Gazing long at the cinnamon moon-wheel. Although the body's free and easy, Yet I still think of people in the world. |

[42] If you wonder who stays happy only those who live apart forest flowers are like brocade every season the colors are fresh but when I sit in the cliffs and gaze at the cinnamon wheel although I feel at peace I wonder about mankind |

40 |

我見出家人, 總愛吃酒肉。 此合上天堂, 卻沈歸地獄。 念得兩卷經, 欺他道鄽俗。 豈知鄽俗士, 大有根性熟。 |

我见出家人, 总爱吃酒肉。 此合上天堂, 却沈归地狱。 念得两卷经, 欺他道鄽俗。 岂知鄽俗士, 大有根性熟。 |

wǒ jiàn chū jiā rén , zǒng ài chī jiǔ ròu 。 cǐ hé shàng tiān táng , què shěn guī dì yù 。 niàn dé liǎng juàn jīng , qī tā dào chán sú 。 qǐ zhī chán sú shì , dà yǒu gēn xìng shú 。 |

[39] I see those who have become monks: All of them love to drink wine and eat meat. Originally they acted with Heaven-bound conduct, But then sank into a path toward Hell. Chanting their two chapters of sutras, They cheat the people of the marketplace. But how could they know that among those marketplace people Are many who have roots of merit that have matured? |

[43] By and large the monks I meet love their meat and wine instead of climbing to Heaven they slip back down to Hell they chant a sutra or two to fool the laymen in town unaware the laymen in town are more perceptive than them |

41 |

我見頑鈍人, 燈心柱須彌。 蟻子嚙大樹, 焉知氣力微。 學咬兩莖菜, 言與祖師齊。 火急求懺悔, 從今輒莫迷。 |

我见顽钝人, |

wǒ jiàn wán dùn rén , dēng xīn zhù xū mí 。 yǐ zǐ niè dà shù , yān zhī qì lì wēi 。 xué yǎo liǎng jīng cài , yán yǔ zǔ shī qí 。 huǒ jí qiú chàn huǐ , cóng jīn zhé mò mí 。 |

[40] I see those foolish men, A tiny wick supporting Mt. Sumeru. Ants gnawing away at a mighty tree, Unaware how weak their power is. Training to eat their stalks of grass, Saying they're the same as their masters. You must seek to confess your sins right now! Don't always be lost as you are now. |

[3] I see someone short on sense a wick propping up Sumeru an ant gnawing on a giant tree unaware how weak he is he's learned how to bite through a stem or two and thinks he's up to the masters let him repent right now and be a fool no more |

42 |

若見月光明, 照燭四天下。 圓暉掛太虛, 瑩凈能蕭灑。 人道有虧盈, 我見無衰謝。 狀似摩尼珠, 光明無晝夜。 |

若见月光明, |

ruò jiàn yuè guāng míng , zhào zhú sì tiān xià 。 yuán huī guà tài xū , yíng jìng néng xiāo sǎ 。 rén dào yǒu kuī yíng , wǒ jiàn wú shuāi xiè 。 zhuàng sì mó ní zhū , guāng míng wú zhòu yè 。 |

[41] Have you seen the brilliance of the moon? A shining candle illuminating all the earth. Its round radiance hangs in the Great Void, Sleek and clean, as clear as this. People say it waxes and wanes, But I see that it has no fading or withering. Its form is like the mani pearl; Bright light no matter day or night |

[4] Behold the glow of the moon illumine the world's four quarters perfect light in perfect space a radiance that purifies people say it waxes and wanes but I don't see it fade just like a magic pearl it shines both night and day |

43 |

余住無方所, 盤泊無為理。 時陟涅盤山, 或玩香林寺。 尋常隻是閑, 言不幹名利。 東海變桑田, 我心誰管你。 |

馀住无方所, |

yú zhù wú fāng suǒ , pán bó wú wéi lǐ 。 shí zhì niè pán shān , huò wán xiāng lín sì 。 xún cháng zhī shì xián , yán bù gān míng lì 。 dōng hǎi biàn sāng tián , wǒ xīn shuí guǎn nǐ 。 |

[42] Where I dwell is Nowhere Place; I linger in the village of Karmic Freedom. At times I climb Nirvana Hill, Or enjoy myself in temples of fragrant trees. Typically I find nothing but leisure, My speech indiffer ent to fame and profit. As the eastern sea turns to mulberry fields, My mind, who will bother with you then? |

[5] I live in a place without limits surrounded by effortless truth sometimes I climb Nirvana Peak or play in Sandalwood Temple but most of the time I relax and speak of neither profit nor fame even if the sea became a mulberry grove it wouldn't mean much to me |

44 |

左手握驪珠, 右手執慧劍。 先破無明賊, 神珠自吐焰。 傷嗟愚癡人, 貪愛那生厭。 一墮三途間, 始覺前程險。 |

左手握骊珠, |

zuǒ shǒu wò lí zhū , yòu shǒu zhí huì jiàn 。 xiān pò wú míng zéi , shén zhū zì tǔ yàn 。 shāng jiē yú chī rén , tān ài nà shēng yàn 。 yī duò sān tú jiān , shǐ jué qián chéng xiǎn 。 |

[43a] [43b] |

[6] The Black Dragon Pearl in his left hand the Sword of Wisdom in his right he vanquished the Demon of Darkness so the Magic Pearl could shine for he was moved by fools who never weary of love and desire sinking into the Three Mires before sensing there's danger ahead |

45 |

般若酒泠泠, 飲多人易醒。 余住天臺山, 凡愚那見形。 常遊深谷洞, 終不逐時情。 無思亦無慮, 無辱也無榮。 |

般若酒泠泠, |

bān ruò jiǔ líng líng , yǐn duō rén yì xǐng 。 yú zhù tiān tái shān , fán yú nà jiàn xíng 。 cháng yóu shēn gǔ dòng , zhōng bù zhú shí qíng 。 wú sī yì wú lǜ , wú rǔ yě wú róng 。 |

[44] How clear and cold is the wine of wisdom! Those who drink deep will easily sober up. I live at Tiantai Mountain— How could I reveal myself to the foolish and common? I often ramble in deep valleys and caves, Never pursue the style of the time. No worries and no concerns, No shame and no glory either. |

[7] The wine of wisdom is so cold drinking it makes men sober where I live on Tientai fools are hard to find I prefer caves and gorges I don't keep up with the times free of sorrow and worry free of shame and glory |

46 |

平生何所憂, 此世隨緣過。 日月如逝波, 光陰石中火。 任他天地移, 我暢巖中坐。 |

平生何所忧, |

píng shēng hé suǒ yōu , cǐ shì suí yuán guò 。 rì yuè rú shì bō , guāng yīn shí zhōng huǒ 。 rèn tā tiān dì yí , wǒ chàng yán zhōng zuò 。 |

[46] What do I have to worry about in this existence? I pass through this world following my karma. Days and months pass like departing waves, Time is just a flash from a flint stone. Let Heaven and Earth change as it may, But I'll delight in sitting here on my cliff. |

|

47 |

嗟見多知漢, 終日枉用心。 岐路逞嘍羅, 欺謾一切人。 唯作地獄滓, 不修來世因。 忽爾無常到, 定知亂紛紛。 |

嗟见多知汉, |

jiē jiàn duō zhī hàn , zhōng rì wǎng yòng xīn 。 qí lù chěng lóu luó , qī mán yī qiē rén 。 wéi zuò dì yù zǐ , bù xiū lái shì yīn 。 hū ěr wú cháng dào , dìng zhī luàn fēn fēn 。 |

[47] I sigh to see those know-it-alls Who vainly employ their mind all day, Showing off their clever words at the crossroads, Cheating ever yone they meet. They only become the dregs of Hell, Don t cultivate the karma of the life to come. When Impermanence comes upon them, Certainly things will be thrown into chaos. |

[44] I sigh when I see learned men wasting their minds all day babbling away at a fork in the road deceiving whoever they can creating more ballast for Hell instead of improving their karma impermanence suddenly comes and all their learning is dust |

48 |

迢迢山徑峻, 萬仞險隘危。 石橋莓苔綠, 時見白雲飛。 瀑布懸如練, 月影落潭暉。 更登華頂上, 猶待孤鶴期。 |

迢迢山径峻, |

tiáo tiáo shān jìng jùn , wàn rèn xiǎn ài wēi 。 shí qiáo méi tái lǜ , shí jiàn bái yún fēi 。 pù bù xuán rú liàn , yuè yǐng luò tán huī 。 gēng dēng huá dǐng shàng , yóu dài gū hè qī 。 |

[48] |

[45] Up high the trail turns steep the towering pass stands sheer Stone Bridge is slick with moss clouds keep flying past a cascade hangs like silk the moon shines in the pool below I'm climbing Lotus Peak again to wait for that lone crane once more |

49 |

松月冷颼颼, 片片雲霞起。 匼匝幾重山, 縱目千萬裏。 谿潭水澄澄, 徹底鏡相似。 可貴靈臺物, 七寶莫能比。 |

松月冷飕飕, |

sōng yuè lěng sōu sōu , piàn piàn yún xiá qǐ 。 kē zā jī zhòng shān , zòng mù qiān wàn lǐ 。 xī tán shuǐ chéng chéng , chè dǐ jìng xiāng sì 。 kě guì líng tái wù , qī bǎo mò néng bǐ 。 |

[49] The pine-tree moon is windblown and chill; Shred by shred the roseate clouds rise. The many layers of hills, clustered together, Stretch to vision's limit for countless miles. The valley pool water is clear Like a mirror to its very depths. The mind is a thing to be treasured— How could a Seven-Jeweled Pagoda compare? |

[46] The pine moon looks so cold cloud after rising cloud countless rings of ridges the view extends a million miles the gorge pool looks so clear like gazing into a mirror precious creature of the spirit tower the seven jewels can't compare |

50 |

世有多解人, 愚癡學閑文。 不憂當來果, 唯知造惡因。 見佛不解禮, 睹僧倍生瞋。 五逆十惡輩, 三毒以為鄰。 死去入地獄, 未有出頭辰。 |

世有多解人, |

shì yǒu duō jiě rén , yú chī xué xián wén 。 bù yōu dāng lái guǒ , wéi zhī zào è yīn 。 jiàn fó bù jiě lǐ , dǔ sēng bèi shēng chēn 。 wǔ nì shí è bèi , sān dú yǐ wéi lín 。 sǐ qù rù dì yù , wèi yǒu chū tóu chén 。 |

[50] There are men with “great understanding” Who foolishly study idle texts. They do not worry about future results, Only know how to create evil causes. When they see the Buddha they can't pay him homage; When they view a monk they grow even more angry. The Five Perversions, the Ten Evil Acts, The Three Poisons they take as neighbors. And once they die, they enter Hell, And they'll never emerge again. |

[47] The world has its know-it-alls fools for empty prose indifferent to the harvest they sow seeds of hate seeing buddhas they don't bow meeting monks makes them mad Sin and Evil are their colleagues the Poisons live next door when they die they go to Hell and see the sun no more |

51 |

人生浮世中, 個個願富貴。 高堂車馬多, 一呼百諾至。 吞並田地宅, 準擬承後嗣。 未逾七十秋, 冰消瓦解去。 |

人生浮世中, |

rén shēng fú shì zhōng , gè gè yuàn fù guì 。 gāo táng chē mǎ duō , yī hū bǎi nuò zhì 。 tūn bìng tián dì zhái , zhǔn nǐ chéng hòu sì 。 wèi yú qī shí qiū , bīng xiāo wǎ jiě qù 。 |

[51] Human life in this floating world: Everyone wants to be rich: With lofty hall, many horses and carriages, A hundred assents to every summons. Swallowing up others' fields and homes, Planning to pass it on to descendants. But before seventy autumns have passed, The ice melts and the tiles shatter. |

|

52 |

水浸泥彈丸, 思量無道理。 浮漚夢幻身, 百年能幾幾。 不解細思惟, 將言長不死。 誅剝壘千金, 留將與妻子。 |

水浸泥弹丸, |

shuǐ jìn ní dàn wán , sī liáng wú dào lǐ 。 fú òu mèng huàn shēn , bǎi nián néng jī jī 。 bù jiě xì sī wéi , jiāng yán cháng bù sǐ 。 zhū bāo lěi qiān jīn , liú jiāng yǔ qī zǐ 。 |

[52] It's like water soaking mud clods: When you think about it, it makes no sense. Like floating froth this illusory dream body; Out of a hundred years how long can it last? You don't know how to think deeply about it— Just say that you'll live forever. You scrape together your pile of gold Merely to leave it to your wife and kids. |

[48] For a mud ball dropped in water big plans make no sense for a fragile dreamlike body a hundred years are rare unable to ponder deeply and claiming they're immortal people steal a ton of gold then leave it all behind |

53 |

雲林最幽棲, 傍澗枕月谿。 松拂盤陀石, 甘泉湧淒淒。 靜坐偏佳麗, 虛巖曚霧迷。 怡然居憩地, 日(以下缺)。 |

云林最幽栖, |

yún lín zuì yōu qī , bàng jiàn zhěn yuè xī 。 sōng fú pán tuó shí , gān quán yǒng qī qī 。 jìng zuò piān jiā lì , xū yán méng wù mí 。 yí rán jū qì dì , rì ( yǐ xià quē )。 |

[53] Cloudy forest—the most secluded place to rest; I keep to the stream, rest on the moonlit creek. Pine trees brush the level stone, Sweet springs well up in clarity. I calmly take pleasure, only favoring beauty here, Lost in the shrouding mists on this empty cliff. I joyfully take my r est in this place, The sun . . . (The rest of the text is missing) |

|

54 |

可笑是林泉, 數裏少人煙。 雲從巖嶂起, 瀑布水潺潺。 猿啼唱道曲, 虎嘯出人間。 松風清颯颯, 鳥語聲關關。 獨步繞石澗, 孤陟上峰巒。 時坐盤陀石, 偃仰攀蘿沿。 遙望城隍處, 惟聞鬧喧喧。 |

可笑是林泉, |

kě xiào shì lín quán , shù lǐ shǎo rén yān 。 yún cóng yán zhàng qǐ , pù bù shuǐ chán chán 。 yuán tí chàng dào qū , hǔ xiào chū rén jiān 。 sōng fēng qīng sà sà , niǎo yǔ shēng guān guān 。 dú bù rào shí jiàn , gū zhì shàng fēng luán 。 shí zuò pán tuó shí , yǎn yǎng pān luó yán 。 yáo wàng chéng huáng chǔ , wéi wén nào xuān xuān 。 |

[54] How delightful this forest stream— For several miles no smoke from human fires. Clouds arise from cliffs and steeps, While water murmurs in the torrent. Gibbons chatter, singing a song of the Way; Tigers roar as they come out among men. The clear pine-wind whistles and roars, And the speech of birds twitters around me. Alone, I tread round the stony creek, Solitary, climb the peaks and hills. At times I sit on the level stones; Looking skyward I ascend, clambering up vines. I gaze afar at the city walls And only hear their clamor and din. |

[49] Woods and springs make me smile no kitchen smoke for miles clouds rise up from rocky ridges cascades tumble down a gibbon's cry marks the Way a tiger's roar transcends mankind pine wind sighs so softly birds discuss singsong I walk the winding streams and climb the peaks alone sometimes I sit on a boulder or lie and gaze at trailing vines but when I see a distant town all I hear is noise |

![]()

Shide (kínaiul: 拾得; pinyin: Shídé; magyar népszerű átírás: Si-tö; japánul: Jittoku) vagyis „Lelenc” kínai buddhista költő, aki a Tang-dinasztia (618-907) idején, kb. a 9. században élt.

Si-tö a kínai irodalom , a Tang-kori líra kevésbé jelentős alakja. 54 fennmaradt verse a Tang-kor több mint kétezer költőjének majd ötvenezer versét tartalmazó gyűjtemény legvégén, afféle függelékben kapott helyet, a szerzetes-költők sorában, akik után már csak a taoista papok, a legendás halhatatlanok és szellemek versei következnek. Alakja elválaszthatatlan a remeteköltőként számon tartott Han-san személyétől, akinek fiatalabb kortársa és barátja volt. Mesterükkel, Feng-kan-nal együtt ők alkotják „A tiantai-i három szent” csoportját (Tien-taj szan seng 天台三聖). Amíg Han-san történetisége mind a mai napig kutatások tárgyát képezi, addig Si-tö alakja és műveinek elemzése kevesebb tudományos figyelmet kap, verseinek keletkezési ideje ismeretlen, azok tartalmi és formai elemzésére még nem került sor.

Élete

Si-tö életének részleteire egyrészt a verseiben találhatunk utalásokat, ezenkívül csupán egy pár legenda örökíti meg alakját. Az éltére vonatkozó legendák közül az egyiket A Tang-kor összes verse (Csüan Tang si 全唐詩) című gyűjtemény szerkesztői adták közre, az ötvennégy összegyűjtött verse elé illesztve:

拾得,貞觀中,與豐幹、寒山相次垂跡於國清寺。初豐幹禪師游松徑,徐步赤城道上,見一子,年可十歲。遂引至寺,付庫院。經三紀,令知食堂,每貯食滓於竹筒。寒山子來,負之而去。一夕,僧眾同夢山王云:「拾得打我。」旦見山王,果有杖痕。眾大駭,及閭丘太守禮拜後,同寒山子出寺,沈跡無所。後寺僧於南峰採薪,見一僧入巖,挑鎖子骨,云取拾得舍利,方知在此巖入滅,因號為拾得巖。今編詩一卷。

„Si-tö a Csen-kuan-korban (627-650) Feng-kan nal, Han-san-nal nagyjából egy időben élt a Kuo-csing-kolostorban. Annakelőtte Feng-kan csan mester a fenyves ösvényen járván lassú léptekkel, a Veres Fal útján találkozott egy tíz év körüli fiúval. Bevitte magával a kolostorba, s átadta a személyzetnek. Harminchat év után főszakács lett. Az ételmaradványokat mindig bambuszcsövekbe tette el, s mikor Han-san-ce eljött, elvitte a hátán. Egyik éjjel a szerzetesek valamennyien azt álmodták, hogy a hegy istene azt mondta: „Si-tö megvert engem.” Reggel a hegy istenén valóban botütés nyomait látták. Mind nagyon megfélemedtek. Mikor az történt, hogy Lü-csiu helytartó tisztelgett előttük, utána Han-san-ce-vel elmentek a kolostorból, nyomuk veszett. Később a kolostorbeli szerzetesek a déli hegycsúcsnál rőzsegyűjtés közben találkoztak egy szerzetessel, aki csontokat szedett össze mondván: „Si-tö ereklyéit szedem össze.” Ekkor jöttek rá, hogy ebben a szakadékban pusztult el, ezért nevezték el Si-tö szakadékának. Egy tekercs verse van.”

— Csongor Barnabás fordításaA történetből kiderül, hogy Si-tö talált gyerek, ezért aztán még az eredeti nevét sem ismerjük, hiszen a Si-tö annyit jelent csupán, hogy Lelenc. Erre egyébként maga is utal verseiben:

15. vers

寒山住寒山,拾得自拾得。

凡愚豈見知,豐幹卻相識。

見時不可見,覓時何處覓。

借問有何緣,卻道無為力。A Rideg-hegyen lakik jó Han-san,

S csak úgy találtak engem, Lelencet.

Ostobák rólunk nem tudnak semmit,

Minket egyedül Feng-kan ismert meg.

Más hiába néz, meg sem pillanthat;

Ha keresnek, sehol sem lelhetnek.

Megválaszolom kérdésed, hogy mért:

Ez biz az Út, a nem-cselekedet.

16. vers從來是拾得,不是偶然稱。

別無親眷屬,寒山是我兄。

兩人心相似,誰能徇俗情。

若問年多少,黃河幾度清。Kezdetektől fogva Lelenc vagyok,

S hogy így hívnak, dehogyis véletlen.

Családi kötelék engem nem tart,

Han-san bátyó, csak ő az egyetlen.

Két remek cimbora: egy szív s lélek,

Mi nem vagyunk nagyvilági mohók.

S ha kérded, élt időnk mennyi - tudd, hogy

Láttuk tisztának a Sárga-folyót.

Egy másik történetben Feng-kan az, aki Han-san-t és Si-tö-t Mandzsusrí és Szamantabhadra bodhiszattva, a mahájána buddhizmus két nagy istensége megtestesülésének nevezi. A későbbi hagyományban mindhárman a csan példaképek jelentős alakjainak számítanak.Si-tö költészete