ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

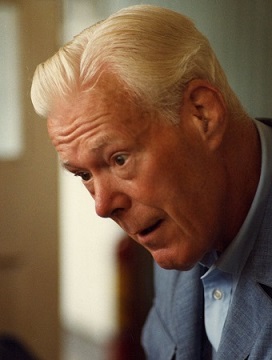

Trevor Leggett (1914-2000)

Leggett, Trevor, Samurai Zen: The Warrior Koans (London: Routledge, rev. ed., 2003, orig. publ. as The Warrior Koans: Early Zen in Japan by Routledge Arkana, 1985). Based on collections from 13 th century Japan, featuring anecdotes of Zen men and women of the Kamakura “samurai Zen” culture. An important window onto one aspect of Rinzai Zen's formative period in Japan. The revised edition of his book adds an 8-page introduction. See also Leggett's more expansive historical study including the contemporary period, Three Ages of Zen: Samurai, Feudal and Modern (Boston/Tokyo: Tuttle, 1993). See Leggett's two volume “Zen Reader” series: A First Zen Reader (Boston: Tuttle, 1960/1980) has excellent selections on the theory and practice of Zen—including translations of two lecture series by two famous masters of the modern era: Takashina Rosen, primate of the Soto Zen sect and president of the Japan Buddhist Assoc., and, representing the bulk of the book, Amakuki Sessan of the Rinzai sect commenting back in the 1930s on Hakuin's “Song of Zazen.” The Tiger's Cave and Translations of Other Zen Writings (Tuttle, 1995), originally published as A Second Zen Reader (Tuttle, 1989), a good sequel to his first book, is filled with translations of short works on various neglected aspects of Zen. Trevor Leggett (1914-2000), the first foreigner to attain 6 th Dan senior teaching level in Judo, taught most of the top British trainees in judo; he headed the Japanese Service of the UK's BBC for 24 years (retiring in 1970) and was a consultant for the segment on Zen for the BBC's television series on world religions, “The Long Search” (1978). Leggett's other interesting books on Zen include Zen and the Ways (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978; reprint Tuttle, 1987), with translations of rare scrolls on Zen and the “ways” or arts of tea, the sword, archery, etc.; Encounters in Yoga & Zen (Routledge, 1993), reflecting not only his Zen studies but also his studies with Hari Prasad Sastri and Leggett's finding and translation from Sanskrit a rare work of sage Sankara on The Yoga Sutras; Fingers & Moons: A Collection of Zen Stories and Incidents (Buddhist Publ. Group, 1988/2011); and his final work, written a year before his passing, The Old Zen Master: Inspirations for Awakening (Buddhist Publ. Group, 2009), another collection of short stories, anecdotes, and personal reflections on Zen and other spiritual traditions related to Self-awakening.

© Copyright 2018 by Timothy Conway

https://buddhismnow.com/category/trevor-leggett/

https://tlayt.org/home/

Trevor Leggett, 1938

A Brief CV

Source: http://www.leggett.co.uk/

Trevor Leggett's teacher of Yoga and its philosophy was the late Dr. Hari Prasad Shastri, pandit and jnani of India. Dr Shastri was commissioned by his own teacher to spread the ancient Yoga abroad, which he did in China, Japan and lastly for twenty seven years in Britain until his death in 1956. The Yoga is based on the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita but is to be spread on non-sectarian and universal lines. It has a clear-cut philosophy and training method.

Trevor Leggett was his pupil for eighteen years and was one of those entrusted with the continuation of Dr. Shastri's mission. All Leggett's books on spiritual subjects are dedicated to his teacher.

Trevor Leggett had lived in India and Japan and knew Sanskrit and Japanese. From 1946 for 24 years head of the BBC Japanese Service broadcasting in Japanese to Japan twice a day. He was a translator and author of some thirty books mostly on Eastern and Far Eastern yoga and Zen, with some cross-cultural studies. Three of them in Japanese. He also held the rank of 6th Dan in Judo from Kodokan, Tokyo and 5th Dan in Shogi, Japanese chess.

In 1984 he was awarded the Third Degree of the Order of the Sacred Treasure, by the Emperor of Japan, in recognition of his services to cross-cultural relations between East and West, through broadcasting, translations and other books, and through active introduction of aspects of Japanese culture to the West. There are eight degrees of this Order, from the First down, and this is the Third Grade, which is in practice the highest a private individual can get.

A FIRST ZEN READER (PDF)

Charles E. Tuttle, Tokyo, 1960Contents

The Original Face by Daito Kokushi

A Tongue-tip Taste of Zen by Takashina Rosen, Primate of the Soto Sect in Japan

Hakuin's 'Song of Meditation' commentary by Amakuki Sessan [天岫接三 Amakuki Sessan (1878-1961)], of the Rinzai Sect, pp. 65-199.

坐禅和讚 Zazen Wasan by 白隠慧鶴 Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1769)

Translated as "The Song of Meditation"

in Trevor Leggett, A First Zen Reader, Charles E. Tuttle, Tokyo, 1960, pp. 67-68.

The Two Poems by Oka Kyugaku [丘球学 Oka Kyūgaku (1877-1953)],

in Trevor Leggett, A First Zen Reader, Charles E. Tuttle, Tokyo, 1960, pp. 201-205.Bodhidharma and the Emperor from the Rinzai and Soto Koan anthologies

A Note On The Ways by Trevor Leggett

ZEN AND THE WAYS (PDF)

Zen and the Ways, London: Routledge and K. Paul, 1978; Charles E. Tuttle Co., Inc. 1987Expressions of Zen inspiration in everyday activities such as writing or serving tea, and in knightly arts such as fencing, came to be highly regarded in Japanese tradition, evolving into spiritual training called "Ways." This volume includes translations of some rare texts on Zen and the Ways.

E.g. 坐禅論 Zazen-ron by 大覚禅師 Daikaku Zenji (1213-1278). Translated as "On meditation".

THE WARRIOR KOANS (PDF)

Arcana, an imprint of Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, 1985SAMURAI ZEN (PDF)

Routledge, London - New York, 2003今井福山 Imai Fukuzan

湘南葛藤録 Shōnan kattōroku

100 kōans, compiled by 無隠 Muin of 禅興寺 Zenkō-ji (Kamakura) in 1545; reedited by 今井福山 Imai Fukuzan (1925)

Translated by Trevor LeggettThe Warrior Koans & Samurai Zen brings together 100 of the rare riddles which represent the core spiritual discipline of Japan's ancient Samurai tradition. Dating from thirteenth-century records of Japan's Kamakura temples, and traditionally guarded with a reverent secrecy, they reflect the earliest manifestation of pure Zen in Japan. Created by Zen Masters for their warrior pupils, the Japanese Koans use incidents from everyday life - a broken tea-cup, a water-jar, a cloth - to bring the warrior pupils of the Samurai to the Zen realization. Their aim is to enable a widening of consciouness beyond the illusions of the limited self, and a joyful inspiration in life - a state that has been compared to being free under a blue sky after imprisonment.

A SECOND ZEN READER (PDF)

The Tiger's Cave and Translations of Other Zen Writings

Charles E. Tuttle, Tokyo, 1988Contents

Introduction

PART ONE

On the Heart Sutra a commentary by Abbot Obora [大洞良雲 Ōbora Ryōun (1874-1969)] of the Soto Zen sect (contemporary)

1 The Immutable Scripture

2 The Circle of Life

3 Awakening to the Character of our Individuality

4 The True Character of the Human Self

5 Transcendence

6 The Experience of Emptiness

7 The Bodhisattva Spirit

8 The Experience of Nirvana

9 The Power of Prajna

PART TWO

Yasenkanna (method of physical and spiritual rejuvenation) - an autobiographical narrative by Zen Master Hakuin (18th century)

1 Introductory Note by the Translator

2 The Preface, by Cold Starveling, a disciple in Poverty Temple

3 Yasenkanna, by Hakuin夜船閑話 Yasenkanna by 白隠慧鶴 Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1769)

Translated as "Yasenkanna (method of physical and spiritual rejuvenation) - an autobiographical narrative by Zen Master Hakuin"

PART THREE

The Tiger's Cave and other pieces

1 The Tiger's Cave

2 The Lotus in the Mire

3 Poems by Zen Master Mamiya [Cf. 101 Zen Stories, 42. The Dead Man's Answer]

[間宮英宗 Mamiya Eijū (1871-1945)]

Sometimes there is the opportunity

But not the capital;

Sometimes there is the capital

But not the opportunity;

Rarely, very rarely, come at the same time

Opportunity and capital both—

But then I am not there myself.

Oh this world!*

A gentleman came to see me

With talk of a remarkable investment.

‘Sir, I am a penniless priest;

All I can give is the treasure of satori

Which ends sufferings for ever. . . .’

But he had left,

But he had left.*

On a lotus leaf sits a frog,

His hands folded, his mind still,

In meditation.

Look out, look out!

Behind him a hungry snake,

Searching for food, is putting out its tongue.

Does he know? Does he not know? The frog

Sits in meditation with closed eyes.

Look out, look out!4 The Dance of the Sennin Immortals Maxims of Saigo

PART FOUR

Zen by Takashina Rosen [高階瓏仙 Takashina Rōsen (1876-1968)], Primate of the Soto Zen sect

1 The Sermon of No Words (PDF) pp. 177-180.

2 Stillness in action (PDF) pp. 181-182.

PART FIVE

From a Commentary on Rinzai-roku classic, by Omori Sogen [大森曹玄 Ōmori Sōgen (1904-1994)], Zen master, fencing master, and master of the brush (contemporary)

Encounters in Yoga and Zen: meetings of cloth and stone (PDF)

Charles E. Tuttle Publishing Co., Inc. 1993This unique book contains a fascinating selection of traditional

Japanese and Indian stories used by teachers in the Eastern

spiritual schools to assist students in their training. Just as flint

and steel are used to make fire, so these stories can be used to

create sparks in the reader’s mind which can, with care and

attention, be nurtured into the strong light of realization.

The author, who has spent many years training in both yoga

and Zen, has collected the stories from a variety of sources:

conversations with teachers, reminiscences in temple magazines

of teachers of the past, folk tales used to make a training point,

and personal training experiences. The aim of these stories is to

find realization and inspiration in daily life. They are ordinary,

but their traditional presentation will catch the hearts of readers

and reveal something of the inner lines of the currents of life.

The Dragon Mask: And Other Judo Stories in the Zen Tradition

THREE AGES OF ZEN: Samurai, Feudal and Modern

Charles E. Tuttle, Tokyo, 1993, 192 p.Synopsis

This unusual book consists of three translations by the author:

(1) Samurai Zen: a selection of the training interviews of Japanese samurai of the 13th century, when they faced the crisis of Kublai Khan's attempted invasions;

(2) Feudal Zen: practised by the samurai officials who ran the country during the 250 years of internal peace under the Tokugawa Government from 1600-1868;

(3) Modern Zen: Zen in war and peace in one life. The autobiography of a Zen priest who was a prisoner-of-war in terrible conditions in Russia, during which he had nevertheless an enlightenment experience. But as he explains, he still had to resume his Zen training with Master Gyodo after being repatriated.Contents

Part I

Warrior Zen

Imai Fukuzan's Introduction

Selected Koan riddles from translation of Shonan-katto-roku (Record of Koans given at Kamakura)Part II

Feudal Zen

Introduction

The Spur [Translation of Master Torei's 'The Good Steed']Part III

Modern Zen

Introduction

Translation of the autobiography of the late Master Tsuji Somei's 'Treading the Way of Zen'

東嶺圓慈・東嶺円慈・東嶺延慈 Tōrei Enji (1721–1792)PART TWO: Feudal Zen

Translator's Introduction

The Spur by Tōrei EnjiTranslator's Introduction

THE SPUR IS AN ESSAY FOR SAMURAI, WRITTEN BY TOREI, A disciple of Hakuin in eighteenth-century Japan. He wrote this essay in 1755, and it is addressed to a samurai who has faith. So it is in Japanese, and not in Chinese as it might well have been if intended for monks. Torei got it approved by Hakuin, and it was then published.

During the two and a half centuries of peace which Japan enjoyed up to the attack by Western powers in 1854, the samurai had become the administrators of the country. They were not just warriors, though they still had to wear two swords. The Chinese character for the very word "samurai," which is used by Torei, also means "scholar." It is the second element in the compound haku-shi , an academic distinction corresponding to a doctorate. Typical is the comment in a classic of 1830 called Introduction to Budo, which points out that though the samurai must have a basis of firm, strong character, one who relies on sheer force in his undertakings is bound to make a mess of them. He is like a peasant‐ farmer pushed into the role of samurai. There has to be learning and culture besides courage and will, it concludes.

The full title of this work is The Spur for the Good Horse. A fundamental point in the presentation by Torei is that we already have a good horse. It is not a question of creating one: it is a good horse already. But for some reason, that morning it is feeling a bit dull, or a bit obstinate, or it doesn't grasp what it is supposed to do. And then, just a touch of the spur, and—swish—away it goes. A good horse needs only a touch to recall it to itself. The example is meant as a loose parallel to the Buddha‐ nature in man. It is so to say a good horse, but somehow it seems to have become dull or darkened or obstinate or destructively minded. So it needs a touch of the spur, and then—swish—it shows itself as it truly is.

A word which Torei uses, normally translated "dye," originally meant something like a smear or grease. But it became confused with another character which looks very similar, and which means the paths of hell. In hell there is a path where you are climbing over sharp swords, and you never come to the end of them, and there is another hell of flames, and so on. So the character can refer to these, but originally it is something like grease, and this sense is characteristic of the text. The mind gets greasy, gets smeared. One teacher commenting on the point gave a kitchen illustration: "You have got to pick up something very hot and move it from here to there. Now if your hand is perfectly clean and dry, and you pick it up and put it down quickly and cleanly, you won't get burned. But if there is any grease or smear on your fingers, any stickiness, then you'll probably get badly burned because you won't be able to just pick it up and let go. There will be a little bit of clinging, and you'll get burned!"

A central point in Torei's exposition is the necessity of purity. It means cleaning off the grease of clinging attachment, or equally clinging hatred, or miry dullness. (Hatred is clinging; we cannot hate people unless we are interested in them.) First of all we must get rid of sticky attachment. It does not mean never taking up things and putting them down: it means not to clutch at them, not to say "I must have that," or "Don't leave me." Because however much we cling, they all simply pass away. While the karma is favorable, they look solid enough and we feel we can hang on to them; but it soon changes, and we suddenly find they were never there at all.

* * *

The teaching of the main text is summed up in a few sentences at the beginning: all that is seen, heard, felt, understood, is hon-shin. This word means literally heart-essence, explained here with consciousness-only texts. When we see a mountain, we see hon-shin in the form of a mountain; when we hear a bird singing, we hear hon-shin in the form of bird-song. When we lie down on a straw mat, we lie down on hon-shin in the form of a mat.

Then Torei shows how Zen completes the Confucianism, which was the official doctrine for samurai at the time. He points out (as did some Confucians) that it is easy to intone phrases like filial piety, loyalty, and human-heartedness. But most people cannot in fact control their desires and fears, so they fall into evil ways, not stopping at murder of relatives. Zen will enable them to control themselves and follow their principles. If the heart is uncontrolled, then though they look, they do not see, though they listen, they do not hear, and though they eat, they do not taste. One with an uncontrolled heart is like a novice archer who has learned the technique of shooting, but not how to focus on a target. He shoots at random and is entirely destructive. Again he is like a gardener who likes flowers and fruit but does not cultivate the root, because he does not know the connection. The true noble Confucianism can be fully practiced when the heart-essence has been attained.

In the same cheerfully eclectic Japanese manner he praises the Way of the Gods (Shinto), Emperor-worship, and the shrine cults in general (though not quite all; some elements of Left Tantrism had crept in). Without realization of the heart-essence, these may drop away into formal rituals.

The traditional history of Zen was important because Zen was being revived in Japan by Hakuin. The Rinzai branch of it had almost died out. All forms of Buddhism had to be authenticated by showing an unbroken transmission from the Buddha-teaching of India, the Holy Land, through the patriarch-transmission of China. Zen teachers were well aware that some of the most revered traditions do not appear in early records. See for instance the koan-story of the Buddha's twirling a flower before the assembly, as set out in No. 65 of the Warrior Koans (see page 64). Nevertheless they maintained the forms and recited them regularly.

He explains at length how warriors have practiced Zen at times of crisis, and their example inspired others. If some practice hard, all will go well. In the end, the instruction to a samurai and to a Buddhist nun is the same: practice meditation in rest and in action, till the Buddha-heart stands clear in you. It is urgent repetition of truth, with a view to dispelling illusion by sheer insistence. The method, practiced all over the Far East, consists of repeating central truths, with slight variations or even in the original words, again and again. It is effective when the words are repeated verbally with great force, or even when read slowly with strong conviction. The main Buddhist terms are in sonorous Chinese monosyllables; a samurai would have had to read them aloud, slowly, in order to understand them, as there is no redundancy in the written characters. (They correspond to the internationally recognized mathematical symbols, 2, 8, =, %, and so on, which have no one accepted pronunciation, and have to be read carefully.) But reading a translation into an alphabetic script full of redundancies, the eye tends to race over the text, which soon appears merely repetitious and boring. This could be avoided by tape recording the main text with slow enunciation, and then listening to it with concentration.

There are other forms of Kufu; vivid visualization of some of the striking illustrations given in the main text could be one of them.

There is a brief note near the end which echoes one of Hakuin's own writings called The Koan (riddle) of Illness: these have been given as directions for when one is ill. But when he is not ill, let him remember not to waste his time either.

The Spur by Tōrei Enji

Translated by Trevor LeggettIN WHAT ZEN CALLS THE ASCENT FROM THE STATE OF THE ordinary vulgar man to the state of Buddha, there are five requirements. First is the principle that they have the same nature. Second is the teaching that they are dyed different colors. Third is the necessity for furious effort. Fourth is the principle of continuity of training. Fifth is the principle of returning to the origin. These five are taught as the main elements of the path.

The true nature with which people are endowed, and the fundamental nature of the Buddhas of the three worlds, are not two. They are equal in their virtue and majesty; the same light and glory are there. The wisdom and wonderful powers are the same. It is like the radiance of the sun illuminating mountains and rivers and the whole wide earth, lighting up the despised manure just as much as gold and jewels. But a blind man may stand pathetically in that very light, without seeing it or knowing anything about it.

Though the fundamental nature of all the Buddhas and of living beings is the same and not distinct, their minds are looking in quite different directions. The Buddha faces inward and makes the heart-essence (hon-shin) shine forth. The ordinary man faces outward, and is concerned with the ten thousand things.

For what he likes, he develops strong desire; for what he does not like, he develops hatred; when his thinking becomes rigid, he is stupefied. Bewildered by one of these Three Poisons, he turns into a clutching ghost, or a fighting demon ablaze with fury, or an animal. When they are equally mixed in him, he falls into hell, where he suffers in so many ways. These are called the Four Evil States, and they are dreadful. If despite his greed and anger and dullness, he does control himself at least to some extent, he becomes human. Life after life he holds on in the human form. Then, although still not having cut off greed and anger and delusion altogether, the self-control being incomplete, he is born—selfish as he still is—in some paradise. There are six of these so-called Heavens of Desire. Then when the fundamental nature of the Three Poisons has been annihilated, meditation and wisdom manifest in him; but his meditation is on Love, and residual traces of anger and apathy remain. So he is born somewhere in the Eighteen Worlds-with-form. Even when the meditation on Love reaches its limit, the knowledge-vision of the Buddha has not yet opened in him. He is now born in one of the Four Worlds‐ without-form, where dwell the Truth-Hearers and the Buddhas-for-themselves-alone. All the states first described—the four bad ones, the human, and the heavenly ones—when taken together comprise the Six Paths of the World-Process. If we now add to them the Truth-Hearers, Buddhas-for-themselves-alone, bodhisattvas, and the Buddhas, it comes to a total of ten.

Generally speaking, out of the Six Paths, pleasures might seem to be experienced in the human world or in a heavenly one, but in fact it is all pain. How is this? It is because these worlds are based on hearts deeply sunk in agonies of greed, anger, and dullness, and experienced by them as such. So if passions are not lessened, there is no escape from the Six Worlds of Suffering. If they are not escaped, there can never be real peace and happiness.If one wants to get out of the worlds of suffering, first of all one has to realize how they are all the time passing away. What is born, inevitably dies. Youth cannot be depended on, power is precarious, wealth and honor crumble away. High status requires constant vigilance to preserve it. The longest life hardly gets beyond eighty years. Since therefore it is all melting away, there is nothing enjoyable about it. The badly off suffer from not having things; the well-off suffer from having them. The high suffer from being highly placed, and the despised suffer from being lowly placed. There is suffering connected with clothes and food, suffering with the family, suffering from wealth and possessions, suffering from official rank.

So long as the nature is not freed from passions, and the path of seeking release has not been found, then even supposing there were some king and his ministers, glorious like a god among living sages, it would all be insubstantial like a lightning flash or a dewdrop under the morning sun—gone in a moment.

When karma happens to be favorable, these things appear solid enough, but as the favorable karma dissipates, it turns out that there was never anything there at all. By favor of the karma of our parents we have got this body, and by favor of the earth, the skin and flesh and sinew and bone grow. By favor of water, the blood and body fluids come, and by favor of fire, warmth, harmony, softness, and order come to be. By favor of winds, vitality, breath, movement, and change come about. If these four favorable karmas suddenly become exhausted, then breathing ceases, the body is cold, and there is nothing to be called "I." At that time this body is no true "I." It was only ever a rented accommodation.

However clingingly attached to this temporary abode, one cannot expect it to last forever. To realize the Four Noble Truths, that all this is passing, painful, empty, and without a self, and to seek the way of bodhi-intelligence, is what we call the Dharma of Hearing the Noble Truths.

If you would grasp the nature of the universal body of all the Buddhas, first you must be clear about, and then you must enlighten, the root of ignorance in you. How is it to be made clear? You must search after your true nature. How to search? In the eye, seeing of colors; in the ear, hearing of sounds; in the body, feeling distinctions of heat and cold; in the consciousness, feelings of wrong and right: all these must be seen clearly as they are. This seeing and hearing and knowing is at the root of the practice. The ordinary man sees colors and is deluded by colors, hears voices and is deluded by voices, feels heat and cold and is deluded by heat and cold, knows right and wrong and is deluded by right and wrong. This is what is meant by the saying: "The ordinary man looks outward."

The training of a bodhisattva is: when looking at some color, to ask himself what it is that is being seen; when hearing some sound, to ask himself what it is that is being heard; when feeling hot or cold, to ask himself what it is that is being felt; when distinguishing wrong from right, to ask himself what it is that is being known. This is called the "facing inward of the Buddhas." Practicing it is different from facing in the direction in which the ordinary man looks. At first, though facing the same way as the Buddha, the Buddha power and wisdom are not manifest in him. But still, he is a baby bodhisattva, and he must realize that he has come into that company. If he always keeps to his great vow to the Buddhas, praying to the spiritual lights and being loyal to the teacher, then one day the Great Thing comes about, and he is set free in the ocean of Own- good is Others' good.

When you get up in the morning, however much business there may be waiting, first affirm this one thought, first turn to this meditation on seeing and hearing. After that, engage in the activities of the day. When going to have a meal or a drink, first of all you must try to bring this one thought to the fore, and make a meditation on it. When you go to wash your hands, first you should try to bring this thought uppermost in your mind and meditate on it. When last thing at night you are going to lie down, sit for a little bit on the bedclothes and try to bring this thought to the fore and meditate; then lie down to sleep. This is practicing the true path of Buddhas and bodhisattvas. Whip up your enthusiasm for it by realizing how if you fail to grasp your true nature as one with the nature of Buddha, you will be lost in the wheel of continual rebirth, circling endlessly in the Four Births and Six Worlds.

From the beginning, you must learn to put your whole heart into this basic meditation, going ahead with each thought and practicing on each occasion as it comes up. Keep up the right line of the meditation: when you walk, practice while walking; when you sit still, practice while sitting; when talking to people, practice while talking. When there is no talking and things are quiet, then you can meditate more intensely. When you look at things, ask yourself what it is that you see; when you hear things, ask yourself what it is that you hear. When things get very rushed so that you easily get swept away by them, ask yourself what this is, that you should get swept away by it. And even if you do get swept away, don't give up your meditation. If you get ill, use the pain as the seed-subject for your meditation.

In every circumstance, the meditation must go forward in a straight line, however much business there may be. It is not allowable that the meditation should be vivid and clear only when the surroundings are familiar and quiet. Unless the meditation is bright and clear at all times, it cannot be said to have power. If there is an outbreak of armed strife in a country which has to be stopped, at the critical time it is a question of taking the field, confronting the dangers, and fighting fearlessly without ever thinking of turning back—that is the way to victory. The meditation-fight is the same. It is just when you are caught up in situations where your thoughts are disturbed, that there is a chance to win a decisive victory.

Be aware of this heart of yours. See that it does not weaken, and go forward. In fact when things are quiet, it corresponds to the time when warriors are safe within the castle, when they must train themselves in tactics and strategy. They practice with courage and sincerity. When the country is disturbed by armed uprisings, they know that this is the time to go out to the field of battle and decide the issue. You must meditate with just such a strong resolve. You may not have the power of the Buddhas yet, but you are one of those who are on the Way of all the Buddhas.

It is a fact that little enlightenment obstructs great enlightenment. If you give up any little enlightenment you may have, and do not clutch it to yourself, then you are sure to get great enlightenment. If you stick at the little enlightenment and will not give it up, you are sure to miss the great enlightenment. It is like someone who sticks to little profits, and so misses the big ones. But if he does not hang on to little profits, he will surely be able to get big ones. When the little profits are not clung to, but invested bit by bit, it does end in a big profit. Similarly, if you stick to the little profit of little enlightenment, so that the whole life is a succession of experiences of little enlightenments, you will never be able to reach the great freedom, the great release. If you don't find the way to the great freedom through great enlightenment, your individual applications (ji) will not accord with the great principle (ri) , and you will fall into the wrong views of outsiders- away- from- Buddhism. It is terrible. But if, when you have a little enlightenment, you take that as a seed and go forward steadily, further and further with your practice, then the great profit of all the Buddhas becomes fully manifest. You will naturally pass through the barrier- riddles (kansho) set by the patriarchs. Now indeed, individual application and universal principle are in accord, action and understanding are not separate. You attain the state of great release, the great freedom. It is for this that stress is laid on maintaining the practice.

Now when you have penetrated into the truth wholly, all the powers of the Way are brought to fulfilment, all beings everywhere are blessed whenever any opening presents itself. Though you may indeed preach and teach, really there is nothing lacking: "I" and the others all attain the shore of the fourfold Nirvana.

Through the great operation of the great vow, beings and worlds benefit themselves as well as others, and you must resolve never to turn away from it in the future. In the present meantime, there may be mistakes and lapses; legs are weak and the path slippery. If you don't get up when you've fallen down, surely you'll be destroyed. You will die where you've fallen. But if, though falling, you pull yourself up, and falling again, pull yourself up again, and so go ahead further and further, finally you do reach the goal. The sutra says: "If you have broken a commandment, make your repentance before the Buddha at once: then go forward along the Way."

* * *

Intensifying the meditation practice in the way described, when the practice becomes clear and mature, you finally return to his nature, one with that of all the Buddhas. This is what they call Becoming Buddha. When it is said in Zen, See the Nature to Be Buddha, this is what is meant. At the beginning, owing to the one delusion, the True Nature (Hon-shin) which should face inward, is made to circle outwardly in the Six Paths: of hell, clutching ghosts, animals, demons, men, and heavens, rising and sinking like the rim of a chariot wheel through thousands of lives in millions of world-cycles, interminably. The bones of birth after birth would pile up higher than mountain peaks, and the life-blood would overflow the great ocean. So teaches the Buddha. Now having achieved human birth, hard to attain, and having come across his holy doctrine, rarely to be found, and of that doctrine to be able to hear the wonderful truth called the Mahayana, such is to be reckoned the most fortunate of beings. If you fail to take it up or openly reject it, that must be reckoned the greatest of sins. Once lost, it is as difficult to regain the human birth as it would be for a thread lowered from the highest heaven to enter the eye of a needle on the bottom of the ocean.

And the circling in the Six Paths is not just a question of reincarnation. In one single day here people are rising and sinking in it. When the heart is right and avoids wrong, that is a man. When others oppose him and hatred for them arises, that is a furious demon. When one has sticking attachment for what one likes, he becomes a clutching ghost. When the heart gets stuck in thinking of material things, he is an animal. If, even though he does think deeply, attachment is strong, if the flames of anger do not cease, and he seeks to injure others, then he is in hell. All this is losing the path of humanity and sowing seeds of the Three Poisons. Then again there may be a time when the heart is peaceful, not thinking about material things, and there is inner purity; now, though in a human body, his heart is truly said to be sporting in heaven. But in general, people do not realize how they are circling in the Six Paths in a single day. In fact those who attain to human-heartedness are few, what to say of sporting in heaven? Most are sporting in the Three Poisons of animal materialism, ghost hankering, and demon hatred. If they change at all, it is mostly to fall into the paths of hell, tormenting others and destroying everything. See the paths in which we are reincarnating in the course of just one day!

At first, the heart is on the wrong paths two-thirds of the time, with the human being barely holding on to one‐ third. Then again hell comes up in it. So it is that living an ordinary life, it is difficult to get away from those wrong paths. But if in the course of the day there arises some resolve at practice, of the Four Principles of the Truth-Hearers, or the doctrine of Twelve Links of Dependence of the Lone Buddhas, or the Six Perfections of the Bodhisattva Way, then in that heart, seeds of the Three Poisons will be destroyed. He who strives to intensify his practice, finally attains realization; even before he does so, since the poisons in the heart have ceased, he will pass beyond temporary joys of human and heavenly worlds, and ascend to the higher state. Truth-hearers and Solitaries are already noble, what to say of one on the path of the bodhisattva? That path is already so difficult to attain, what to say of the dharma of the Buddha Way? The Zen realization of Seeing the Nature is the very crown of all Buddhahood. He who has his heart set on this is already a baby Buddha. Thought after thought, he steps out toward the gate of peerless merit, along the way of holy perfection. Wonderful is the merit even of reading about such perfection, what to say of practicing it? Even to get another to read it aloud will save one from disaster of fire, so what shall we say of one who practices it himself? The Buddhas bless him, the bodhisattvas stretch out their hands to him, the gods in their heavens applaud him. At a glimpse of his shadow, demons and evil spirits are routed. Spirits imprisoned in the depths, by contact with him realize the opportunity of release. This is called the highest, noblest, and very first dharma. Step by step it must be faithfully followed out.

辻双明 Tsuji Sōmei (1903-1991)

PART THREE: Modern Zen

Translator's Introduction

Treading the Way of Zen: The Autobiography of Tsuji SōmeiTranslator's Introduction

TSUJI SOMEI IS A PRESENT-DAY ROSHI WHO TRAINED UNDER Furukawa Gyodo [Furukawa Gyodo Taiko, 1872-1961], one of the great figures in Zen of the first half of the twentieth century, who taught at Engakuji, in Kamakura, thirty miles from Tokyo. These extracts are translated from his autobiography, and have been selected (with Tsuji Roshi's permission) to focus on the Zen training.

Mr. Tsuji married early and got a job as an accountant with a big oil company. He became interested in possible political solutions to social problems. His wife contracted tuberculosis and died early, leaving him with the children to look after. He later married again.

Treading the Way of Zen

The Autobiography of Tsuji Somei

Translated by Trevor LeggettMY FIRST VISIT TO A MONASTERY TO PRACTICE ZEN WAS IN the summer of 1925, when I was twenty-two and in my first year at the Tokyo University of Commerce [now the prestigious Hitotsubashi University—Tr.] I was one of a student group at the university who practiced Zen meditation, and every year our group joined similar ones from other universities to go to Engakuji in Kamakura for a week's intensive instruction and training.

Furukawa Gyodo Roshi was then the abbot of the monastery, and at my first interview with him, he asked: "Why have you come here?"

I replied: "Because I can't sleep well."

He commented: "That's because you bother yourself over idle thoughts even when you're in bed," and laughed.

I still recall this little scene vividly.

Sitting in the meditation posture for hours and hours, day and night, proved a hard task indeed: the pain in my legs was almost unbearable. Still, after the practice ended, I could sleep unusually well, and when I woke up the next day I thought to myself: "Last night I slept like a log." In itself this was trivial, but the pleasure of this first sound sleep in many nights increased the pull to Zen.

During that first week I was impressed at the sight of the young monks working. To see them sweeping the extensive grounds with bamboo-twig brooms, in perfect silence and with full attention, put me in mind of the intensity of fencers practicing, and I felt a sort of reverence for them. It was also striking to see them walking rapidly, with their hands clasped over the breast and looking straight ahead.

In the early morning we followed them in ladling a little cold water with a dipper, from the large common basin into the hollow of one hand, to wash the face. Again, when the slippers were taken off before entering the meditation hall, they had to be set down perfectly aligned, with the toes pointing outward so that the owner could smoothly slip the feet into them when leaving.

While keeping up my studies of social problems, I did not drop my interest in religion. Sometimes I went to Kamakura to have an interview with Master Gyodo, and I also attended lectures by other Zen masters in Tokyo itself. In those days I could make nothing of them, or even of those by Master Gyodo, and had a private impression of the croaking of frogs. But I was deeply impressed by his character and, when something important came up, I often went to him for advice.

I remember that once I was puzzling over the inconsistency between my profession as an accountant in a commercial firm and my religious aspirations; I had nearly decided to enter some other career. I went to the Roshi and told him what I was proposing to do. He listened in silence to all that I had to say, and then curtly remarked: "This is just your vanity." It was like a great blow with a staff, crushing my deeply considered decision. Afterward I gradually came to realize that he was right.

One day I found myself in the guest room for an interview with the Roshi along with one other visitor, an elderly man. There was no difference at all in the Master's attitude to him, and to the obscure young man that I was. Later on I asked who the old man had been, and discovered that he was a millionaire named Machida, who used to invite Master Gyodo to take monthly Zen sessions at his mansion. I was deeply impressed by the perfect equality with which the Roshi had treated the two of us.

For a hundred days after my wife's death I chanted sutras, and repeated the invocation for a considerable time morning and evening. My three little children often kept company with me during these practices. Often at night I lay in bed with my arms stretched out to each side so that my children could hold my hands while falling asleep.

Meanwhile, I had begun to realize that one might engage in reform movements, political, economic, or social, but if one had not transcended his ego, one would be found to be acting for fame or power in the end, though claiming to be devoted to nation or society. I saw that it was a matter of paramount importance in life for any man to investigate what was his own true nature, and to get completely rid of his petty ego.

About that time I met one of my former classmates at the university, who had been practicing Zen under the guidance of Abbot Ashikaga Shogan. A lay disciple's name, Hakutei, had been conferred on him by his teacher after he had the experience of "seeing the true nature." He remarked to me: "Before I had seen into the true nature of my being, I used to practice meditation like mad." Stirred by these words, I began to practice meditation not only at home but also in the electric train on my way to work. At the office I would avail myself of any spare time to sit and meditate behind a screen of account books. At the lunch break, I went into the reception room for the same purpose.

From the first of November that year, there was an intensive meditation week at Engakuji. I went to it with do-or-die resolution to see my inmost nature at any cost, though I had only been able to get three days leave from the company. I was then thirty-five years old. For the first three days I sat with the monks in the meditation hall. My mind was wholly absorbed in the endeavor to keep in the right frame of mind all the time. Once at a meal I forgot to pick up the chopsticks, and another time during the single-file walking (kinhin) which is part of the meditation, I was so abstracted that I stumbled and fell. The meditations began at three in the morning, and ended at ten at night, but when the day's sitting had come to an end, I felt as if all the hours had passed in a moment. As I look back to my experiences at the time, I find I was in the state technically called "infinite darkness."

At the end of my three days, I had still not attained to seeing the inmost nature. Filled with disappointment, I left the temple. In the electric train on the way back, however, I suddenly experienced an extraordinary inner change. I saw light issuing from the forehead of all my fellow passengers; as I looked, I saw light coming from every object.

After a walk of a quarter of a mile from the station, I got back, and felt an ecstasy welling up within me. I was dancing about the room, literally not knowing how my arms moved, or where my steps trod, as the saying is. Overwhelmed by the strangeness of what was happening, I went back at once to Engakuji and asked for special permission to see the Master. This was not granted, however, because it was so late, so I went to the lay disciples' quarters and sat up meditating the rest of the night. The next morning when I related my experience to the Master, he replied: "While you feel ecstatic, you have not yet gotten there." Then he recited in a low voice a passage from the Record of Rinzai: "The mind adapts itself to all situations, and its manner of adaptation is most subtle. If you realize your nature in the very process of flowing, you will neither rejoice nor grieve." Then he added: "If you can understand this saying, you will have seen into your nature."

When I arrived at the company the next day, the head of my section greeted me jocularly with the remark: "Well, Mr. Tsuji, you certainly seem to have had some good news from somewhere, to have such a shining forehead."

* * *

From this time I kept up the meditation with the utmost intensity. Almost every day I went to Kamakura, passing the nights alternately at home and at Engakuji.

One day after our interview, my teacher Gyodo Roshi said to me: "You come here so often to see me. But are your children well cared for? Even the best medicine should be taken in moderation."

I replied, "But Master, shouldn't iron be struck while it's hot?"

At this, the Roshi looked as though he had swallowed something down, but did not say a word.

Now the newspapers were piling up on my big desk sometimes for weeks together, unread. Though I was in the business world, I begrudged the time for reading them and devoted it to meditation instead. My income did not allow for much margin, and on the trips to Engakuji I used to take some packets of food with me to eat on the way, with a bottle of plain water in the bag as well. As it was now late autumn and then winter, the meal was always cold. Still, I was finding it very tasty and the thought came to me how, when the mind is completely one-pointed, even plain boiled rice and cold water become delicious.There is a Zen saying: "The heart magnanimous, like an emperor," and I found that my inner state was of itself becoming somehow wide and full, and the greatness of the Zen path was borne in on me more and more. I resolved that I would do everything I could to preserve this great traditional path of the East.About this time I was reading almost no Zen books except the Record of Rinzai, and Master Hakuin's Tea‐ kettle classic. In this latter I came across a verse quoted from the great Chinese layman of the Tang dynasty called Master Fu:

Empty-handed, holding a plow:

Walking, riding a water buffalo:

When the man crosses the bridge,

The bridge flows and the water does not.Hakuin said that if one could see right through into this verse, he would see his own true nature.

One morning in November that year, when on the way from Engakuji to work at my company I was walking on the platform of Tokyo station, suddenly the realization of "Walking, riding a water-buffalo" came to me. It was like a flash: "This is it!" While writing at the office, the realization of "Empty-handed, holding a plow" came too. Then in the bus on the way home, I penetrated the last phrases of Master Fu's verse. This was a case of coming to the realization of a Zen koan before having it set formally by the master.

Still, it was some time before my master would sanction my attempts at the koan which he had actually set me. In his interview room (which was called the Poisonous Wolf Cave), he used to urge me to go deeper into it, saying: "Now is the time when you must store up the energy to last you through your entire spiritual career." Looking back, I am grateful indeed for the unyielding firmness of the Master's training.

One day toward the end of November, I was in the interview room presenting my understanding of the koan: "Why is it called Mount Sumeru?" As the teacher spoke, a cry burst from me with the realization throughout my whole being that my true nature was no nature, that the limited and relative self is in fact unlimited and absolute. It was a realization of infinite self in direct experience. It was knowing nothingness to the limit of negation. At that moment of that day, in the Poisonous Wolf Cave, I felt I had been reborn.

From that time onward, when koans were set, I often found solutions to them bubbling up spontaneously within me, to pass me through.

In January of the next year, the teacher gave me the lay name So-mei (The Bright One), and the full Buddhist name Daiki-in So-an So-mei (The Dark-bright Pair in the Hall of Great Power). I later discovered that these two names refer to the Dark-bright Pair in the verse by I'Ts'un at the end of Case 51 of The Blue Cliff Record.

One morning I was going up the slope in the grounds of Engakuji to have an interview with Master Gyodo. It was about dawn. I happened to meet him by the little lake called Myoko (Delicate Scent), which is just below the rise on which the Master's interview room stood.

"Where are you going?" he asked.

"I was hoping to have an interview about my koan," I replied.

"Then I'll hear your answer here," he told me.

So standing on my side of the lake in the faint light, I submitted my solution.

After the interview, he said: "Let us walk together."

Walking behind him, I followed him down the gradual slope toward the temple gate. As soon as we reached the road in front of the temple, he returned by another way.

This was before the time for the regular interviews for the monks living in the monastery, and so early that as yet none of the rays of the sun streaked the sky. The Master wore a pair of wooden clogs, on high supports, and went briskly and calmly along the rugged stony road despite the dark. Seeing him going so fast in the awkward footgear, along a road where even a young man in broad daylight would have to walk with care, I had an inkling of the spiritual energy that had come to my teacher through Zen. He was then about sixty-four.

* * *

In December 1936, the year when I had "seen the nature" (kensho), I moved from my home in Ogikubo in the suburbs of Tokyo to a place in the street in front of Engakuji. This was so that I could have more opportunities for evening interviews with Master Furukawa, even though living in Tokyo, I had been able to get to the temple for the regular interviews in the morning. They began at four a.m. in June and July, but when it came to December and January they would be held a little after six o'clock. So it was not impossible for me to get down to Kamakura, have an interview, and then be back for work in Tokyo. I used to get up quietly and steal out so as not to disturb the family, and could arrive in Kamakura, climb the dark road up the hill, and be on time.

The evening interviews were a little past seven p.m. in June and July, but in the winter months they began just after five o'clock, and as my office duties came to an end at that time I could not possibly manage the interviews during this part of the year. This was a matter of great regret to me.

At Engakuji there were also week-long special intensive meditation periods (sesshin) held four times during the winter months, and four times during the summer. I tried to attend these as often as I could, but my office duties interfered. Also, there was always the possibility that I could be transferred by the company to a branch office in Osaka or Shimonoseki at any time.

I was now devoted to Zen as a noble ideal and resolved to follow it right through. I also wanted to change my present profession for some other which would afford more time and opportunities for Zen. It happened that at the end of 1937, Professor Masao Hisataka (then at Yokohama College and later at Hitotsubashi University), who was a friend of mine, visited our office to inquire about the prospects of employment there next year for some of the promising students of his college. I took the opportunity of talking to him about my own enthusiasm for Zen and my desire for a change of profession which would give me more scope to pursue it.

Early in March the next year, he sent me a card saying that the principal of his college would like to see me, if I would kindly visit him. When I met him he offered me a professorship—I was to teach accounting and bookkeeping.

Apart from my professional qualification, this was what I had been doing at the Kokura Oil Company for the past nine years, during which time I had been promoted from a clerk to a deputy secretary, now receiving a sizeable income plus the regular half-yearly bonuses. But as the new position would provide only perhaps a third of what I had been getting, I put the matter to my wife and explained the circumstances to her. We agreed that we should have to change our style of living completely. As far as spiritual life was concerned, however, I could enjoy a much more congenial and enriched life. Apart from the joy of being able to participate in the morning and evening interviews every day now as well as in the special meditation periods much more regularly, I found teaching more congenial. It was a pleasure to do the preparatory work for the lecture and to teach and talk to students. We often had friendly talks in small restaurants near the college, and some of them used to come to see me at home.

On the surface, teaching is much easier than office work, but in fact I began to feel that I was carrying a heavy burden on my back all the time. It turned out that actually I had less time free from duties than when I had been working in an office. Only during the vacations did I have plenty of free time to spend just as I liked. It is indeed the holidays that are the great advantage of the teaching profession.

One summer vacation I passed about forty days almost entirely away from home. I lodged in the Lay‐ Disciples' Hall in Engakuji, and often sat in meditation in the Founder's Shrine at the Obai-in sub-temple, which is in the Engakuji complex. I gave up shaving, and grew a long beard. One night I decided to sit up all night in meditation in the Lay-Disciples' Hall. As time went on, I became overwhelmed by drowsiness, and finally I lay down where I was, resting my head on one arm. I was suddenly awakened by something dropping on my forehead. To my drowsy perceptions, it seemed to be something quite big. Once fully awake, I realized that it was a large centipede creeping over my neck. I swept it away with my hand. There are many such things in the temple precincts.

At this time of my life, I often slept only three or four hours a night. I suppose that even a few hours will suffice if the sleep becomes deep as the result of the coming-to‐ one of the mind through the practice of Zen meditation.

In the Hakuin tradition, the occasion when the master grants interviews to a disciple, which take place in his living quarters, is called shitsu-nai (inside the room). At the interview, the disciple confronts his master man-to‐ man, presenting his answer to the koan riddle for the master's judgment and engaging in question-and-answer with him. The interview is also termed hossen, or spiritual warfare. It is the most important and solemn occasion in Zen training. Masters' particular ways of training and their spiritual attainments are manifested through their words and actions "inside the room."

There was a calmness, as of the depths of the ocean, about Master Gyodo "inside the room," and also something of what in Zen is called the sheerness of a silver cliff or an iron wall. He hardly ever resorted to slapping or yelling. But sometimes when he rejected my answer to a koan with the words, "That won't do," I felt as if I had indeed been slapped in the face, or thundered at with the usual Katzu! shout.

In the interview room with Master Gyodo it was quiet, but there was a feeling of severity and something terrifying.One winter I caught cold, and a rheumatic knee condition which I had from childhood flared up, so that I could not bend my left knee at all. If I had to squat down, I stuck out my left leg straight in front, and went down on the bent right knee. I had to use a stick when going from home to the interviews at the temple. But when I came before the teacher to make my prostration, the knee could suddenly bend. It was quite extraordinary. When I left to make my way back home, on the other hand, the knee again could not bend.

Another thing that happened to me was a persistent fit of hiccups, which lasted about a week. There was a popular idea that to go on hiccupping for more than a certain number of days would result in death, and I did all the things that are supposed to cure hiccups, but all was in vain. Yet during the interview with the Master, and for some time afterward, the hiccups used to cease. And then they would come back again. This seems perhaps a small matter, but I can never forget it.

At an interview, the Master and I would sit on the ground, face to face, with only perhaps five or six inches between our knees. Although we were so close, sometimes he spoke in such a low voice I could not make out what he was saying. But when I would be walking quietly back along the corridor to the room where the other monks were waiting to strike the bell in their turn to have an interview, his voice seemed as it were to get stronger and stronger in me so that I could easily understand what had been said to me. This too is one of my special memories of the interviews in the Poisonous Wolf Cave.

I was in the special category of what is called tsuzan, so that I could often ask for naizan, which means an interview outside the normal fixed times. To someone in a situation like myself, Master Gyodo would cheerfully give interviews.

At the end of the year in which I had "seen the nature," I asked for one of these interviews, though it was New Year's Eve. Although the next day was the great festival day of New Year, I turned up as usual in the evening and asked for the interview. But the Master's attendant refused me, just saying: "New Year... " Only then did I think: "Why, yes, it's New Year... "; but then the thought came too: "Did not the ancients warn us that change is upon us: time does not wait on man"?

Perhaps I was at that time really steeped in Zen, as the saying goes.

There are some other things I shall always remember about him. Once he caught a cold which led to a high fever. His throat was painful, and his voice terribly hoarse. We were very worried, but he wrapped several lengths of cloth around his throat, and gave the sermons at the sesshin in a sort of strangled voice. After the session was over, I presented myself to pay my respects and asked after him; he just said: "Oh, today I brushed some Chinese calligraphy, so it's all right again."

When he was in good health, his voice was vibrant and very clear. In fact when I first took to going to hear him, it was not so much the content of the address as the attraction of his voice that drew me. At the public ceremonies, he would pass in front of us listeners to make the three bows before the Buddha, and his posture as he passed, and his tread as he went up to the shrine to light a stick of incense, had for me a sort of indescribable magic about them.Usually he used to walk around the temple complex before dawn each morning, but apart from that, he did not leave his private quarters much, so that even in the grounds he was not often to be met. I was once standing in front of the laymen's hall when he came out from his own quarters walking toward the temple gate. I bowed my head and the Roshi brought his palms together in the traditional salutation, pursuing his way without the slightest check. I had the feeling of the Zen saying: "Walk like the wind." At that time he was, I suppose, about sixty-seven or sixty-eight.Another typical incident was this: I was to see him about something, and presented myself at the back door of his quarters, before the sliding door of his attendant's room. I announced myself, and heard the Roshi's own voice: "What do you want?" When I slid open the door, I saw him bent right down, having his head shaved by the attendant monk. In that very awkward position, and accosted unexpectedly, his voice still seemed to come from the depths of his being, and I got an idea of what must have been the thousand temperings and polishings of his training over the long years.

* * *

Here are a few things from those days with Master Gyodo which still often come to my mind:

• Zen is something about which someone who doesn't really know can still manage to write without giving himself away. But if you hear him speak just a couple of words, you know his inner state exactly.

• For Seeing the Nature, it has to be fierce as a lion, but after that realization, the practice has to go slow like an elephant.

• If you get through the first barrier (the first koan) without much trouble, you get stuck afterward and can't get on. It's as if you'd thrust your hand into a glue pot.

• However much you go to Zen interviews, and however many koans you notch up, if you don't get to the great peace ....

• Going simply by the number of koans you pass— well, however many they may be, it's no good unless you come to the samadhi of no-thought. In the samadhi of no‐ thought, there's no soul, there's no body, there are no objects of the senses, much less any koan!

• For Going the Rounds (visiting a number of teachers in turn for interviews) you have got to have an eye that can see a teacher.

• You have to be able to enter freely and come out of the world of the absolute (infinite non-distinction) or the world of the relative (limited distinction) at will.

• You may go the rounds, but unless you learn the strong points of each teacher, you will get nothing out of it. If you are simply looking for weak points in teachers, however much you may go round it will be no good.

• I can't understand what they call reputation in the world. There are people who, when you go and see them, are completely different from what you have heard about them.

• Whatever koan it may be, it comes down to the absolute, or the relative, or an unobstructed harmony of absolute and relative.

• When one has attained realization (satori) the prac tice has to be taken to the point where even the first syllable, sa, meaning "distinguishing," has ceased to exist.

• (Of a certain teacher.) He is supposed to be a teacher, but I find something peculiar about him; and somehow even what he writes has got a smell about it.

• If someone goes right through the training, he goes back to his original temperament. With one who likes rice-wine, it's rice-wine; with one who likes women, it's women—that's the sort of thing.Note by Tsuji Roshi: This remark by Master Gyodo did not mean assenting to sexual practices and other desires: the one who has gone right through the training has come to the state of the true no-I (mu-ga) and no‐ Minding (mu-shin). The Master is pointing here to the heart of heavenly truth, the great life of nature. I feel that this was what was meant by Confucius when he said: "At seventy years of age, I could follow the desires of my heart, and they never transgressed the moral rules."

• A man who does things without "hidden virtue" (on-doku) will surely have no good end to his life.

• So-and-so Roshi used to say he wanted to test teachers, and went round to a number of training halls, boasting of "taking away their announcement bells" and so on. But this sort of thing has no hidden virtue about it, and so his last years were not good.

• In Case 19 of the Mumonkan collection of koans, called "The Ordinary is the Way," Mumon has a comment: "Even when Joshu had realized, he had to start on a further thirty years of practice." I asked about this thirty years, and Master Gyodo said: "Thirty years means the lifetime, practice is the whole life long."

In his sermons, when the subject of the Sixth Patriarch Eno came up, Master Gyodo seemed to burn with enthusiasm as he spoke of how the patriarch had a first enlightenment on hearing a phrase from the Diamond Sutra, that the mind should move without making a home anywhere, had gone to Mount Obai to be under Master Konin, and there was treated not as a priest but as a lay pilgrim and set to pounding rice, and how he was recognized through the poem: "The bodhi (wisdom) is not a tree, nor has the mirror any stand: from the very beginning not a single thing—on what could the dust alight?" Then how he was chosen as successor out of the hundreds of disciples, and entrusted with the Transmission by the Fifth Patriarch, who helped him to leave Obai secretly under cover of darkness to escape the jealousy and spite of some other disciples.

• There is a Zen phrase: "In the cold, the hair stands on end." When the Master used to speak of these dramatic events in the history of Chinese Zen, I experienced this literally. The impact of his words was so tremendous that I felt my hair standing on end.

• Around about this time my favorite reading was the lives of Shido Bunan and Shoju Rojin, teacher of Hakuin. Occasionally Master Gyodo used to say something to the effect that perhaps things were going to become something like they were in the times of Bunan and Shoju. He said that though they were priests, in fact they had much of the attitude of laymen (koji), and that possibly in the future, for a time, the dharma might be propagated by these laymen.* * *

Around then I also came to study enthusiastically the lives of the historic National Teachers Daito and Muso, and I went all the way to Shogenji at Ibuka in Mino province where Muso used to live, and to the Kazan temple in Kyoto, to pay reverence to the tomb of Gudo, who had been a teacher of Shido Bunan.

In 1940 Master Gyodo retired from being head of the Engakuji sect, and went back to the Tenchian hermitage at Kuboyama in the district of Yokohama. At that time his room was at the back of the temple, and on his desk was a goldfish bowl, which someone had brought him. It was set on a light stand made of bamboo cross-pieces. One day, after the Zen interview, I was talking to the teacher when a bee flew into the room, seemed to dance around happily, and then went into the hollow of one of the bamboo pieces of the goldfish bowl stand. Another time when I was there just the same thing happened: I saw a bee fly in and go into the bamboo tube. I got the impression that the Master—so strict and forbidding to pupils—was to this bee a kindly playmate. In this side of the Roshi's character I saw an affinity with Master Ikkyu (some four hundred years before), who had a pet sparrow which he called his attendant. When the sparrow died, he gave him a posthumous Buddhist name, Sonrin, and wrote a death poem for him.

The Master had once told me himself how, when he was still in charge of Jochiji, in his forties, he had been lying asleep with almost nothing on and a large venomous centipede had crawled across his chest. He had not brushed it off and killed it but let it go on its way. When I saw how the bee seemed to be playing in the Master's room, I recalled that story about the centipede.

It is fair to say that up to the time of my call-up into the army in June 1941, I spent almost all the spare time allowed by my professional work in Zen interviews and study. There were times of tension and times of relaxation, but throughout I was treading the path of Zen. In addition to some koans from outside the standard collections, I had in my interviews in the Poisonous Wolfs Cave gone through the whole hundred of the Hekiganshu and got up to number 37 of the Mumonkan classic.When I received the red-colored conscription papers, I went at once to see the Roshi at Tenchian hermitage at Kuboyama, and told him the position. Saying "Oh, really?" he got up from his seat and went into an interior room. He soon came back with two sheets of colored paper about a foot square, on which he had brushed:

No life-and-death for this one

Indomitable courageThe first comes from a phrase of the founder of Myoshinji in Kyoto, the great Kanzan, one of whose names was Egen: "No life-and-death for this Egen."

These two sheets of paper with their brushed characters were always with me during my army service, and later when we were all imprisoned in Russia.

When I was called up, I was engaged on the 38th koan in the Mumonkan, which is Ho-en's "Cow Passing the Empty Window." When I said farewell to Master Gyodo I asked him, "How would it be if I try writing my solution to you?" "Interview by letter?" he said doubtfully, putting his head a little to one side. "Well, you could try it," he then agreed. I did in fact write from where I was stationed two or three times, to have the Zen interview on paper as it were, but after that I gave it up altogether.

I was assigned to an anti-aircraft unit and we were immediately sent to the barracks at Shimamatsu in Hokkaido. We were engaged in the defense of the air above Otaru City. In May 1943 we were ordered to two of the northernmost islands of the Kurile chain. The small mountains rising in the middle of the islands were covered with snow year round. From one of them, Kabuto-yama, on a fine day I could get a distant view of the snow-white peninsula of Kamchatka, and realized how far north I had come.

On these North Kurile islands there are many days of dense fog in summer, and raging snowstorms in winter. The fog is famous for its peculiar humidity, which sometimes made our clothes as wet as if they had been soaked in water. The snowstorms were so violent that they claimed several victims each winter. When one was raging, it required extraordinary care to traverse even the ten-odd yards which separated one of the barrack buildings from the next one. In addition to all this, the islands are subject to hurricanes, which not seldom attain a wind-speed of over 120 miles an hour.

The islands are quite barren, yielding no grains and hardly any vegetables. Food and other necessities of life had to be supplied to us by sea from Japan proper. Thus there were no actual inhabitants of the islands who lived there all the time.

All these circumstances combined to induce in one a feeling of deep desolation, as of being (like so many characters in Japanese history) exiled to a remote island surrounded by the ocean. Of course the arrival of a supply ship was a tremendous event. But these ships were from time to time sunk by enemy submarines. Raids by the American Air Force were very frequent. Soon after our arrival the barrack of a platoon of the searchlight battalion was hit by a bomb, killing not only its leader but the commander of the battalion and the men of a company who happened to be on the spot.

In this grim situation, however, it was still possible for me to study and meditate, by day and by night, whenever it was that I could get the time off from my duties. As for reading, I spent many days on Shimazaki's Before Dawn and Goethe's Faust. I borrowed the Lotus Sutra, translated from the Chinese, from an officer in the paymasters department, and read it over twice with great spiritual benefit. If the Record of Rinzai is comparable to a serene gem, the Lotus Sutra is a magnificent temple decorated with innumerable precious stones. I was also stirred by the proselytizing spirit pervading this sacred book.

After I had read it for the second time, I happened to hear that a man in a certain company had a copy of the Chinese version, and when I next went to that company, following the regimental commander on an inspection tour, I took the opportunity to borrow the book. I copied selections from the twenty-eight chapters of it, in tiny characters in a pocket book; a few of the chapters I copied out in their entirety. I also wrote those passages which impressed me most as the essence of the Lotus Sutra on some small sheets of paper.

Our arrival in the North Kuriles took place immediately after the annihilation of the Yamazaki garrison on Attu in the Aleutian islands in May 1943. After that, the tide of war had been steadily turning against Japan, and it was expected that there might be American landings on our islands any day. We were given preparatory exercises for a final battle in which all were to die in action, with no one surrendering. The exercises in hand‐ to-hand fighting, officers with swords and men with bayonets, were repeated again and again.

Surrounded by such an atmosphere of grim desperation, I read and meditated as before, but also took up daily sword practice with a wooden practice sword or my real one. Before being called up, I had a little instruction in an ancient tradition called batto-jutsu, the art of drawing a sword and striking with a single rapid movement. This is one of the sources of the developed Japanese art of the sword, and I took up the practice again. Among the books I had brought with me was Miyamoto Musashi's Five Rings, which I now studied with profit.After reading the chapter on "How to Use the Feet and How to Walk," I happened to pass a dried-up river‐ bed full of boulders. Going down to the bed I drew my sword and struck out in all directions against imaginary opponents, at the same time having to keep my balance and freedom of movement among the stones. This experiment brought home to me the real value of Musashi's teachings.In the chapter on "Sight in the Knightly Arts," it is said:

Of pure awareness and the physical eye, it is very important in the knightly arts that all-seeing, imperturbable awareness should be the stronger of the two, so that one should be able to see the distant like the near, and the near like the distant. It is most important in the knightly arts to know your opponent's sword, without looking at it at all. You must try hard to learn how to do so.... It is also important to see either side without moving your pupils to the side at all. If you are taken up with the world, you cannot expect to learn the secret in a short time. Take to heart what I have written here, and always practice fixing the gaze in this way, so that it does not waver. This has to be wrestled with again and again. This is in the Book of Water.

The last section, called "Emptiness," has this:

may be sure that you have attained the spiritual state of true 'Emptiness.'

You should diligently cultivate the spirit and the mind, as well as awareness and the physical eye, every day and every hour. When you have made them cloudless and free from all delusions, then you may be sure that you have attained the spiritual state of true 'Emptiness.'

From this it is clear how much importance Musashi attached to the point about awareness and the physical eye. This having taken a firm hold of my mind, I exercised myself in it with my sword every day, in a little wood of alders (dwarfed by the cold), and against the background of the mountains clad with perpetual snow. On the 16th of July, 1944, when I was training myself in awareness and physical eye along these lines, with the bare sword before me, I realized the real meaning of the phrase: "Cold stands the sword against the sky," and I saw that I had never really understood it.

At the same time I had a realization of knowing from the inside the first koan of the Hekiganshu (Blue Cliff Record): "Vastness, no holiness!", and the comment in the Gateless Gate (No. 19): "When you attain the way of no doubts at all, it is an abode of vastness like infinite space," and Shido Bunan's state of "Nothing to Defend," and again the poem which the fencer Yamaoka Tesshu composed on his enlightenment: "One morning the floor and walls were all pulverized and I saw the round dewdrops shining as ever." (The passage in Bunan's work The Heart As It Is runs: "Someone asked me about Mahayana, and I said, 'Keeping oneself upright, to have nothing to defend, that is Mahayana.' Then he asked about the highest Way, and I said, 'Doing just as one likes, to have nothing to defend, that is the great thing. And that is why there are very few such in the world. "')

I returned straightaway to my room and went right through the hundred koans of the Blue Cliff and the first thirty-seven of the Gateless Gate, one after another. I had already passed through each of them in the interview room with Master Gyodo, but now I felt that I had penetrated into their very marrow.

I came to see how significant was the "Vastness, no holiness!" koan at the very beginning of the Blue Cliff. Vastness. Great Emptiness. Empty Space. Nothing to Defend, express the Dropping off Body-mind, Body‐ mind dropped-off state which is the essence of Zen, and the marrow of all the classical koans.

I felt I had realized the state of which it is said "to pass one is to pass all" and "cutting through all the old koans." Since the time of first seeing the nature in November 1936, some eight long years had gone by up to this moment, with great changes in the situation of Japan and of course my own personal situation too. But this day was one of the most unforgettable of my whole life.

Years later, when in a priest's robe I was practicing the austerity of a mendicant in the streets of Kyoto, I looked in at the museum and chanced upon the admonition of National Master Daito, in which he says, "The Great Teacher Bodhidharma came from India across the turbulent waves, and saw first the Liang lord (the emperor Lang Wutei) to whom he declared 'Vastness, No Holiness!' The thousand miles and ten thousand miles were like one bar of iron. After that he went to Shaolin, and there was the test of his four disciples who grasped skin, flesh, bone, and marrow respectively. All was nothing more than 'Vastness, No Holiness!'..."

Reading this closely, I felt it was a confirmation of my experience in the Kuriles in July 1944.Back in Japan after being a prisoner in Russia, I one day spoke of this realization in the Kuriles to Master Gyodo, who listened in silence. Then he just said: "However good a thing may be, it will not do to get caught up in it." Gyodo Roshi always admonished us strictly: "Don't get caught up in anything at all. Go beyond everything!"

* * *

I heard the Emperor's broadcast on Horomushiro island announcing the cessation of hostilities, and toward the end of August 1945 we were taken prisoner by the Soviet Army. We were put together with other units in large warehouses near the airstrip, and in this very anxious and restrictive situation we each had to get on with our lives as best we could. I used to go into the trees every day and chant the Kannon Sutra and the Essence of the Lotus Sutra which I had compiled in a loud voice. Then one day I was asked by the regimental commander to give a talk on zazen (contemplation) to an audience of nearly all the officers, after which, gradually, they began to sit together most evenings for a short time before going to sleep. However, this did not last long, as in November we were put onto a Russian ship. We hoped we were going to be repatriated to Japan, but our hopes were dashed when the ship made for a Russian port.