ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

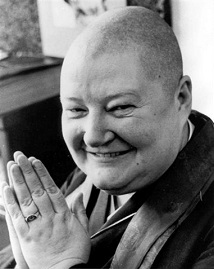

法雲慈友ケネット Hōun Jiyu-Kennett (1924-1996)

born Peggy Teresa Nancy Kennett

PDF: Serene reflection meditation

by Jiyu Kennett et al.

First published in 1974PDF: Zen is Eternal Life, 1976

(Formerly published as Selling Water by the River, 1972) by Jiyu KennettRoar of the Tigress: The Oral Teachings of Rev. Master Jiyu-Kennett: Western Woman and Zen Master

PDF: Vol. 1. and Vol. 2.PDF: The Wild, White Goose: The Diary of a Female Zen Priest

https://web.archive.org/web/20101026071524/http://www.shastaabbey.org/teachings-publications_whiteGoose.html

by Reverend Roshi P.T.N.H. Jiyu-Kennett, Shasta Abbey, Mount Shasta, California 2002

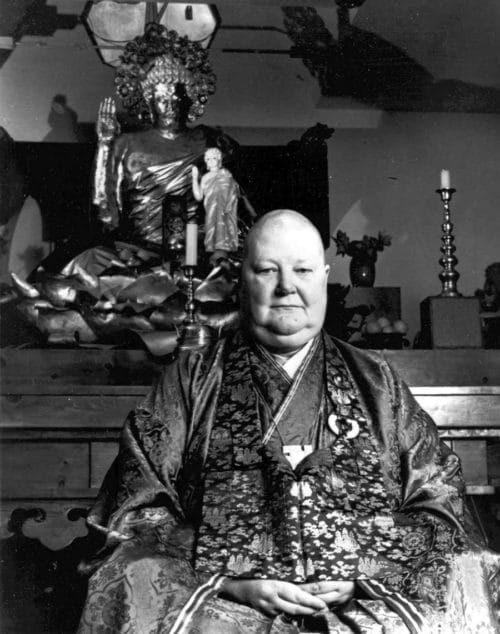

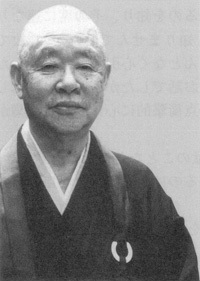

Reverend Master Jiyu-Kennett (1924-1996)

http://obcon.org/saf.html

The Order of Buddhist Contemplatives was founded in 1978 by Rev. Master P.T.N.H. Jiyu-Kennett, a Buddhist Master in the Serene Reflection Meditation (Soto Zen) tradition. Born in England in 1924, Rev. Master Jiyu-Kennett became a Buddhist in the Theravada tradition. She was later introduced to Rinzai Zen Buddhism by D.T. Suzuki in London where she held membership in, and lectured at, the London Buddhist Society. She studied at Trinity College of Music, London, where she was awarded a Fellowship and obtained the degree of Bachelor of Music from Durham University.

Rev. Master Jiyu-Kennett began her priest training in 1962, having been ordained into the Chinese Buddhist Sangha in Malaysia by the Very Reverend Seck Kim Seng, Archbishop of Malacca. She then went to Japan at the invitation of the Very Reverend Keido Chisan Koho Zenji, Chief Abbot of Dai Hon Zan Soji-ji, one of the two chief training monasteries of Soto Zen, in order to train there in that tradition. In 1963 she received the Dharma Transmission from Koho Zenji and later was certified by him as Roshi (Zen Master). She also received a First-Kyoshi and a Sei Degree, roughly equivalent to a Master and a Doctor of Divinity in Buddhism. She held several positions during her years in Japan including that of Foreign Guestmaster of Soji-ji and Abbess of her own temple in Mie Prefecture.

It had always been Koho Zenji's sincere wish that Soto Zen Buddhism be successfully transmitted to the West by a Westerner. He worked very hard to make it possible for Rev. Master Jiyu-Kennett to train in Japan and, after his death, she left Japan in order to carry out his wish. In November 1969, Rev. Master Jiyu-Kennett came to San Francisco on a lecture tour. The Zen Mission Society was founded the following year and moved to Mount Shasta for the founding of Shasta Abbey in November of

In addition to being the First Abbess of Shasta Abbey, Rev. Master Jiyu-Kennett was an instructor at the University of California and the Institute of Transpersonal Psychology, and a lecturer at universities throughout the world. She founded numerous Buddhist temples and meditation groups in Britain, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United States. Her books include Zen is Eternal Life, a manual of Zen Buddhist training; The Wild, White Goose, Volumes I and II, the diaries of her years in Japan; How to Grow a Lotus Blossom or How a Zen Buddhist Prepares for Death; The Book of Life, a treatise on karma and health, coauthored by Rev. Daizui MacPhillamy, and The Liturgy of the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives for the Laity. In recent years, she edited three new translations of Serene Reflection writings and ceremonies: The Denkoroku or The Record of the Transmission of the Light, Buddhist Writings on Meditation and Daily Practice: The Serene Reflection Meditation Tradition, and The Monastic Office. A collection of her oral teachings, edited by Rev. Daizui MacPhillamy, has been published as Roar of the Tigress, Volumes I and II.

Rev. Master Jiyu-Kennett died in November of 1996. This site is dedicated to her memory, out of gratitude for her great compassion.

***

PDF: Tibetan and Zen Buddhism in Britain : Transplantation, Development and Adaptation. By David N. Kay

London and New York: Routledge Curzon, 2004, 260 p.

The OBC's [Zen Buddhist Order of Buddhist Contemplatives] development has been turbulent. Jiyu Kennett, its female founder, reformulated Zen for the West especially in her adoption of Christian imagery and liturgy. Most problematic was Kennett's ‘third kensho', when she was overwhelmed by visions which she articulated in mystical and ‘quasi-theistic' terms. Such visions have vivid precursors in Christian mysticism, but they are anathema to mainstream Zen, and they prompted a deep rift. Kennett's close disciples had their own visions that overlapped with their teacher's, while others regarded the whole episode as a bizarre ‘collective dream'.

Her innovations according to Dharma Rain Zen Center, Portland, Oregon:

1. She brought and adapted the formality of the Japanese monastic-style of practice and form to this country.

2. She introduced and adapted the Segaki traditions to our Halloween to remember and address the ghosts of our personal and collective karma.

3. She introduced and adapted the five ceremonies of Jukai with its connection to the Buddhist liturgical cycle and the teachings of Tozan's Five Ranks and of the Sotoshu's Shushogi.

4. She emphasized the everyday life as a koan (the Genjokoan), examining the Bodhisattva precepts as koan study.

5. She developed a liturgical calendar that corresponds with our annual seasonal cycles.

6. She designed a rigorous form of postulant training for aspiring monks as a gateway to ordination.

7. She adapted meal forms and oryoki-style to western cultural practices.

Hōun Jiyu-Kennett wearing a purple robe

Dogen Zenji at first refused to receive an honorary purple robe from the Emperor. After he turned it down a second time the Emperor said, "You must receive it." So finally he accepted it. But he didn't wear it, and he wrote to the Emperor saying, "I very much appreciate your purple robe, but I do not dare wear it, because if I wore it, the birds and monkeys on this mountain would laugh at me."

[Shunryu Suzuki in Not Always So: Practicing the True Spirit of Zen, p. 27.]

In Memoriam, Houn Jiyu Kennett Roshi

January 1st, 1924 - November 6th, 1996

By Kyogen Carlson sensei

On Wednesday November 6th Jiyu Kennett Roshi died at Shasta Abbey from complications due to diabetes. Both Gyokuko and I received Dharma Transmission in the Soto Zen lineage from Kennett Roshi; mine was in 1974, Gyokuko's in 1977. Kennett Roshi received Dharma Transmission from Keido Chisan Koho Zenji, Chief Abbot of Dai Hon Zan Sojiji. She lived and studied in Japan from 1962 to 1968. During her stay there, she had an operation for a benign tumor that adhered to several internal organs, including the pancreas, which left her with a diabetic condition leading to the complications that eventually took her life. It was Kennett Roshi's wish that her teacher, Koho Zenji, be honored as the founder of temples connected with Shasta Abbey. Even after our formal separation from affiliation we honored that wish, but with her passing we will soon be installing her photograph along with his in our Founder's Shrine.

The so-called "First Generation Zen Teachers" in the West are those trained in Asian countries that brought Zen to non-Asian people in their own countries at the time it first seriously took root in the late fifties through the early seventies. Some of them, like Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, were Asians, while others were of European ancestry, such as Philip Kapleau and Robert Aitken (both of whom are still with us, happily). This group of teachers have many characteristics in common, including strong, independent personalities, a penchant for innovation, and an unfortunate tendency to die rather young. Although new teachers trained in the East continue to come to the West, this "First Generation" arrived when there were no established lineages and traditions outside the Asian immigrant communities. That has dramatically changed because of the pioneering work of this first wave of teachers, who's ranks are now thin. They should be valued as precious Dharma Treasures.

Jiyu Kennett Roshi's unique qualities included her rather extensive background in both Theravadin and Chinese Mahayana Buddhism, her classical music education, her exposure to her father's tailoring and clothes design work, and a deep love of formal monasticism, both western and eastern. She brought all of these influences into her work establishing a residential training monastery in northern California. Her father was involved with the London Buddhist Society during its formative years in the 1920s, and his interest led her to become a member in the 1950s. Her father died during World War Two, which led to a decline in the family situation. As soon as she was old enough, she enlisted in the Royal Navy. Her music training and natural talent in that direction was noticed in the testing they did, so she was assigned to the coding and decoding branch of Naval Intelligence. After the war, she attended Durham University in the north of England, graduating with a Bachelor of Music degree, with an emphasis on medieval musicology. After graduation she was a church organist for a time and had contact with several religious orders. In England, interest in Buddhism arose mostly from the experience of "the British Raj," the period of Imperial control of India and Sri Lanka. The London Buddhist Society (LBS) had connections with the Maha Bodhi Society, and when Kennett Roshi was a member there, she had considerable exposure to Theravada Buddhism and met a number of Bikkhus and Theravadin scholars. She took a course of study in Buddhism through the Young Men's Buddhist Association of Ceylon.

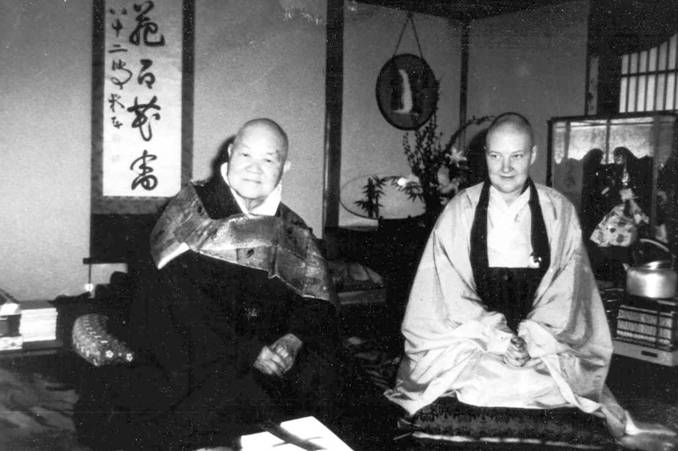

Zen and the Buddhism of the Far East was less known in England at that time, but there was a connection at the LBS with the Rinzai Zen scholar D.T. Suzuki, who used to lecture there. Chisan Koho, abbot of Sojiji in Yokohama, was a very forward looking man for that time, and particularly for his generation. He was very interested in Western culture, religion, and philosophy, and he believed that the rapid absorption of western science and technology by Asian nations would be balanced by Eastern spirituality moving west, leading to a new world culture. He wanted to make Zen available to Westerners, and in particular, he wanted a Western Dharma Heir to help bring that about.

In 1960 he arranged a world tour, visiting religious leaders and even heads of state, and was received at the White House by president Eisenhower. On that tour he visited the London Buddhist Society, and gave a talk there. Assigned to assist him during his stay was Peggy Kennett, then 36 years old. They hit it off right away, for it was arranged that she would go to Japan as soon as feasible to enter Sojiji as his disciple. All the implications of this would not be known to her for some time.

In January, 1962, Peggy Kennett arrived in Malaysia after a sea voyage through the Suez Canal, including a stop in Sri Lanka. On January 21st she was ordained into the Buddhist priesthood by Rev. Sek Kim Seng, abbot of Cheng Hoon Teng, Melaka, Malaysia. He gave her the Dharma name "T'su Yu," the Chinese pronunciation for the Sanskrit "Sumitra," or "Compassionate Friend." In Japanese, this is pronounced "Jiyu." Why she was ordained by a Chinese abbot in Malaysia is not entirely clear, but apparently some arrangements had been made by a western Buddhist priest she knew from the LBS who was living in Malaysia at that time.

In any event, Kim Seng became her mentor and sponsor, helping financially, and giving her a place to stay when she needed a respite from the rigors of her life and training in Japan. In April 1962 she arrived in Yokohama and shortly after was received by Chisan Koho as his disciple. This period of time in Japan was one of great change, and in particular the consolidation of changes that occurred right after World War Two during the occupation. Women had been given more rights and freedoms in the new constitution, but the implementation of real equality for women in Japanese society was a matter of slow, daily struggle. Two important figures in the Sotoshu at that time were Kendo Kojima and Shundo Aoyama. They were among the very first women to enter the Sotoshu University, Komuzawa, during the occupation immediately after the war. Shundo Aoyama went on to head the Aichi Semmon Niso-so, a training monastery for women and author of Zen Seeds, now available in English. Kendo Kojima continued to work for ordained women in other ways, trying to lever the Sotoshu into permitting women to rise into positions of authority. Chisan Koho was known for his support for and work on behalf of women, and Kendo Kojima visited Sojiji a number of times during this period. Chisan Koho and she were able aid their respective efforts by making reference to the work of the other, and it was into this milieu that Jiyu Kennett arrived in April of 1962.

Jiyu-Kennett at Sojiji: being the only westerner and the only nun in the all-male monastic community; she was totally excluded.

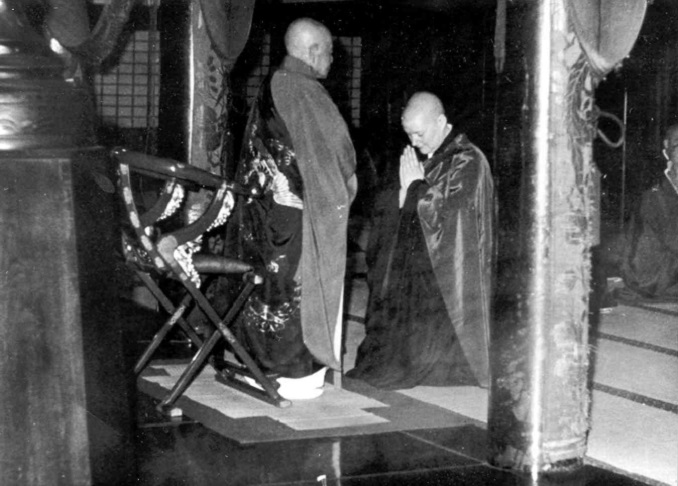

Reverend Master Jiyu-Kennett asking a question in a ceremony called shosanChisan Koho was a very influential figure as one of the three highest ranking priests in the Sotoshu hierarchy. As Kennett Roshi progressed in her training, he was able to obtain certifications for her that were unheard of for women, and for a foreign woman, it was beyond the comprehension of many Japanese Soto monks. Years later, in the late 1970s, a Japanese Soto Zen nun visited Kennett Roshi at Shasta Abbey and explained that very the last official impediment to complete parity for women in the Sotoshu had been overcome, and the precedent set by Kennett Roshi's certifications had been a very important part of that achievement. It was the first time she realized the extent of the effort Chisan Koho made on her behalf, and for all women in the Sotoshu. His influence in bringing this about also resulted in some squashed toes and bruised egos at the time. When he died in 1968, Kennett Roshi found her situation in Japan becoming very difficult. She had a hard time knowing who her friends really were as the political tide shifted against her. Later that year she left Japan and flew to San Francisco with two disciples. She used to tell us that we could never fully know what it was like for her to leave the remnants of Edwardian England to live within one of the most feudal parts of Japanese society, and then land in the Height-Ashbury at the height of the hippie movement, making a 300 year cultural time shift overnight. She stayed briefly at San Francisco Zen Center, then started temple in a small apartment in that city and founded the Zen Mission Society. The small sangha grew quickly and in just a few months they moved to a rented house near Lake Merit in Oakland. By 1971 they purchased the land near Mt. Shasta, 60 miles south of the Oregon border, and Shasta Abbey was born. Originally named Shasta Zan Chisan-ji in honor of her teacher, a name that never stuck, the Abbey became a residential training monastery and grew quickly. After a series of rather confusing name changes the Zen Mission Society became The Order of Buddhist Contemplatives, and on that it seems to have settled. For several years there, I thought of it privately as "the holy order of the changing name."

Wanting to avoid political entanglements with the Sotoshu, Kennett Roshi always steered a very independent course. She used to say "Know many, trust a few, always paddle your own canoe," and she truly did live by those words. She was quick to drop oriental ways when she thought it wouldn't affect the spirit of the practice. Chop sticks disappeared, and even the formal zendo bowl sets included knife, fork, and spoon. The elaborate robes were replaced for everyday use with robes incorporating pockets and sleeves of a more practical width, while the more formal Japanese koromo were kept for important services. She opted for brown everyday robes for senior monks, as she got tired of looking at our pale American faces over the severe, black Japanese style robes. Chanting also changed to a Gregorian derivative influenced by the Church of England liturgy with which she was familiar. She used to say that the rhythm of the English language was not well suited for the monosyllabic style developed for chanting in Chinese and Japanese. In fact, the history and development of Gregorian chant parallels very closely the chant styles that evolved for Buddhist sutras in Pali and Sanskrit. Except for the harmonies, and the eventual addition of an organ for accompanying the chants, services at Shasta Abbey would sound very similar to those Sanskrit and Pali sutras. Kennett Roshi also adopted the use of English style tea in preference to Japanese tea, prompting one observer in the early seventies to say that Zen at Shasta was becoming more Anglican than American. Perhaps she was just ahead of her time in some respects. Since those days English Breakfast and Darjeeling teas have become commonplace in American households.

In her teaching at Shasta Abbey, one of her strongest assets was a deep understanding of the power of ritual, and its ability to convey the Dharma in a nonverbal way. She also emphasized the importance of the basic Buddhist teachings she learned from Theravadin teachers, and hammered into her students that they should never confuse the Mahayana concept of hinayana with the Buddhist Theravadin tradition. She stressed Precepts as the basis of practice, using Shushogi as a standard text year after year. Ethics were of primary importance to her, even if she didn't always understand American sensibilities regarding them, and even if she often seemed unable to hold herself and her students to the same standard. Because of her association with western monasticism, she had an instinct for what it would take to create a Zen monastery in this country. It would be hard to find a Zen facility anywhere in this hemisphere that is more truly monastic than Shasta Abbey, even if it has become isolated and idiosyncratic. Strong monastic practice is noticeably and sorely lacking in the overall picture of American Zen.

Kennett Roshi developed a deep distrust of the Japanese Sotoshu based on the extremely difficult time she had there, particularly after her own teacher died. Over the years the Abbey became more insular and isolated from other lineages in this country, which in many opinions, including mine, led to an unhealthy internal environment conducive to abuses. I also believe that things were done there that were injurious to individuals and were clearly improper, but were justified in the name of the Dharma which makes it all the worse. In my opinion, unless these problems are openly acknowledged for what they were, they will continue to affect the organizational climate there, becoming a toxic part of the collective shadow, and making it unsafe to recommend to seekers of the Way. This is unfortunate, as the monastery has a lot to offer. Both Gyokuko and I feel the most profound gratitude for what we received from Kennett Roshi personally, and from the environment of practice she created at Shasta Abbey. Struggling on our own to create something here in this temple only makes it clearer to me what a difficult challenge she had trying to create a monastery from scratch. In upcoming issues of this newsletter I hope to convey something of that in my own reminiscences and those of others. I should also add that the isolation at the root of some real problems also led to wild speculation and some pretty silly misunderstandings about the practice at Shasta Abbey and Kennett Roshi's teaching. Hopefully, in the years to come, her successors at the monastery will be more open and communicative, acknowledge the human failings all teachers are prone to, and allow themselves to experience the wonderful currents of change and growth happening in Buddhist communities all over the country. This would be excellent, because American Zen would benefit in turn from contact with the unique aspects of practice developed at Shasta Abbey. It would be nice, but only time will tell.

PDF: STILL POINT

VOLUME XXII NUMBER 1 JANUARY-FEBRUARY 1997

www.dharma-rain.org/StillPoint/archives/SPjan_feb97.shtml

More in Still Point from January to October, 1997 > StillPoint Archives

Dharma Lineage

PDF: Ancestral Line

永平道元 Eihei Dōgen (1200-1253)

孤雲懐奘 Koun Ejō (1198-1280)

徹通義价 Tettsu Gikai (1219-1309)

瑩山紹瑾 Keizan Jōkin (1268-1325)

明峰素哲 Meihō Sotetsu (1277-1350)

珠巌道珍 Shugan Dōchin (?-1387)

徹山旨廓 Tessan Shikaku (?-1376)

桂巌英昌 Keigan Eishō (1321-1412)

籌山了運 Chuzan Ryōun (1350-1432)

義山等仁 Gisan Tōnin (1386-1462)

紹嶽堅隆 Shōgaku Kenryū (?-1485)

幾年豐隆 Kinen Hōryū (?-1506)

提室智闡 Daishitsu Chisen (1461-1536)

虎溪正淳 Kokei Shōjun (?-1555)

雪窗祐甫 Sessō Yūho (?-1576)

海天玄聚 Kaiten Genju

州山春昌 Shūzan Shunshō (1590-1647)

超山闡越 Chōzan Senetsu (1581-1672)

福州光智 Fukushū Kōchi

明堂雄暾 Meidō Yūton

白峰玄滴 Hakuhō Genteki (1594-1670)

月舟宗胡 Gesshū Sōkō (1618-1696)

卍山道白 Manzan Dōhaku (1635-1715)

月澗義光 Gekkan Gikō (1653-1702)

大用慧照 Daiyū Esshō

華嚴曹海 Kegon Sōkai

祥雲太瑞 Shōun Taizui

日輪當午 Nichirin Tōgō

尊應教堂 Sonnō Kyōdō

祖嶽靈道 Sogaku Reidō

大俊鞭牛 Daishun Bengyū

孤峰白岩 Kohō Hakugan

莹堂智璨 Keidō Chisan (1879-1967) [孤峰 禅師 Kohō zenji]

&

法雲慈友 Hōun Jiyu (1924-1996) [born Peggy Teresa Nancy Kennett]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Houn_Jiyu-Kennett

ˇ

Myozen Blacker, Gyokuko Carlson, Kyogen Carlson, Meian Elbert, Myoun Ford, Eko Little, Daishin Yalon

余語翠巌 Yogo Suigan (1912-1996)

PDF: The Kyojukaimon and Explanation of the Ketchimyaku

by Rev. Suigan Yogo* and Rev. Jiyu Kennett with Message from the Chief Abbot, Chisan Koho

Seal of 大本山總持寺 Daihonzan Sōjiji written

by the Vice Abbot, 岩本勝俊 Iwamoto Shōshun (1891-1979)

[mimeographed at Daihonzan Sōjiji, Tsurumi, Yokohama, ca. 1965, 15 p.]

*in 1967 he was the fuku-kan-in 副監院 = vice-secretary, or assistant director; an important administrative position with teaching responsibilities at Sōjiji

"YOGO SUIGAN-ROSHI we have been hearing about for some years as a very good teacher with a real feeling for Westerners practicing Zen. He is the Godo* roshi of the large Soto training monastery, Sojiji, in Yokohama. In a Soto monastery the Godo is head of and directly responsible for the complete practice of the monks. Yogo-roshi visited Zen Center in June, 1971, after a month's residence in Colorado as guest of the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies. His first visits to this country were encouraged by Mr. and Mrs. Armand Bartos, the parents of Jonathan Altman, an old student of Zen Center."

Wind Bell, Publication of Zen Center, San Francisco, Vol. XI. 1972, p. 29.

*godō 後堂 = rear hall roshi; a senior monk who occupies a place on the platform next to the rear door in a sangha hall and acts as an advisor to the head seat (shuso 首座)

河頭賣水 / 河頭に水を売る "Selling Water by the River"

余語 翠巌 Yogo Suigan's calligraphy

http://suifuko.jp/yogo-suigan/yogo-suigan-7/"I wish to acknowledge the very great help of Reverend Suigan Yogo in translating the writings of Keizan and most of the ceremonial as well as parts of Dogen. There is no doubt that this book could never have been written without his help and encouragement."

In: Selling Water by the River by Jiyu Kennett, New York: Pantheon, 1972, p. xi."The translations appearing in Selling Water by the River were based on pre-existing translations, and not from original texts translated by Kennett Roshi herself. (She was not very proficient in Japanese so it is highly unlikely that she would have been able to translate material that even experienced Japanese scholars find difficult). When I was in Unpuku-ji she was working from drafts made of verbal/dictated translations by Suigan Yogo which she would rephrase and rework. Shortly after I arrived at Unpuku-ji Kennett Roshi gave me a typed manuscript which had been published by Soji-ji Foreign Guest Department, with a preface by her dated July 23rd, 1967 in her capacity as foreign guest master. This manuscript titled Zen is Eternal Life, consists of what became Book I of Selling Water by the River. In the acknowledgements in the 1971 edition she lists Daisetz Suzuki and Reiho Matsunaga's translations as sources. Contrary to her acknowledgements, I did not translate the Dogen material in Selling Water by the River. I translated the "General and Special Offertories" and compiled the glossary (which has a misprint - gyoun-ryusyu instead of gyoun-ryusui). At Shasta Abbey I continued with the translation of Keizan's Denkoroku where it left off at Chapter XV - for a while with a scholar of Chinese - which was serialized in the Journal of the Zen Mission Society. In Hazelton I was working on a translation of another of Koho Zenji's books. Later in Terrace I started translating Dogen's Eihei Koroku for the zazenkai - I was happy when I eventually obtained Yuho Yokoi's translation and later that by Taigen Leighton and Shohaku Okumura!"

Myozen Delport Sun Oct 14, 2012 9:05 pm

Jeanette A. H. Delport, aka 妙禅 Myōzen (1945-)

ジャネット ミョウゼン デルポート Janetto Myōzen Derupotō

Myōzen Delport & Jiyu Kennett on the 5th of July 1970, in Oakland, California

Myōzen Delport's recollections (in 2012) about Jiyu Kennett and Suigan Yogo:

http://obcconnect.forumotion.net/t537-myozen-delport