ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

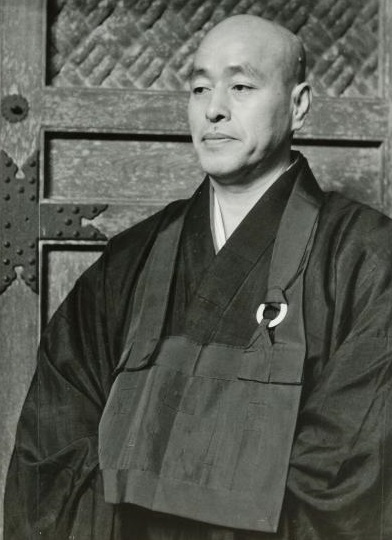

横井覚道 Yokoi Kakudō (1922-1974)

![]()

1) Katagiri's friend and third teacher, cf. 片桐 (慈海) 大忍 Katagiri (Jikai) Dainin (1928-1990)

2) Friend of 野圦 (白山) 孝純 Noiri (Hakusan) Kōjun (1914-2007); Noiri Roshi and Yokoi Roshi had the same master: 岸澤 (眠芳) 惟安 Kishizawa (Minpō) Ian (1865-1955)

3) He was the master of Brian Daizen Victoria (1939-)

Zen at War

by Brian (Daizen) A. Victoria.

New York & Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1997."In the spring of 1970 I was called into the room of Zen Master Niwa Rempō [丹羽 (瑞岳) 廉芳 Niwa (Zuigaku) Rempō] (1905-1993), then the chief abbot of Eiheiji Betsuin temple in Tokyo. He informed me that since I was a Sōtō Zen priest and a graduate student in Buddhist Studies at Sōtō Zen sect-affiliated Komazawa University, it was not appropriate for me to be active in the anti-Vietnam war movement in Japan. While he acknowledged that my protests were both nonviolent and legal, he stated that "Zen priests don't get involved in politics?' And then he added, "If you fail to heed my words, you will be deprived of your priestly status?'

Although I did not stop my antiwar activities, I was not ousted from this sect. In fact, I went on to become a fully ordained priest, which I remain to this day. This was very much due to the understanding and protection extended to me by my late master, the Venerable Yokoi Kakudō, a professor of Buddhist Studies at Komazawa as well as a Sōtō Zen master. Niwa Rempō went on to become the seventy-seventh chief abbot of Eiheiji, one of the Sōtō Zen sect's two head monasteries. We never met again." (Foreword, p. ix.)"My late master, Yokoi Kakudō, he was born in 1922 and died in 1974. Note that he died of cancer at a relatively young age. I regularly visited him in the hospital and was present at his death, together with his other disciples." (a letter from Brian Victoria to Gábor Terebess, March 27, 2025)

Zen Master Who?: A Guide to the People and Stories of Zen

by James Ishmael Ford

Wisdom Publications, 2006"Dainin Katagiri (1928-1990) encountered his third teacher, Kakudo Yokoi at Komazawa University, who introduced him to Tomoe, the woman he would marry." (p. 134.)

Yokoi Kakudō, “Fundamental Understanding of Sōtō Zen Buddhism.”

Komazawa daigaku bukkyō gakubu kenkyū kiyō 駒沢大学仏教学部研究紀要 [Bulletin of the Faculty of Buddhist Studies, Komazawa University] 31 (3/73), pp. 1-6.

Translation of Fumiko & Carl Bielefeldt

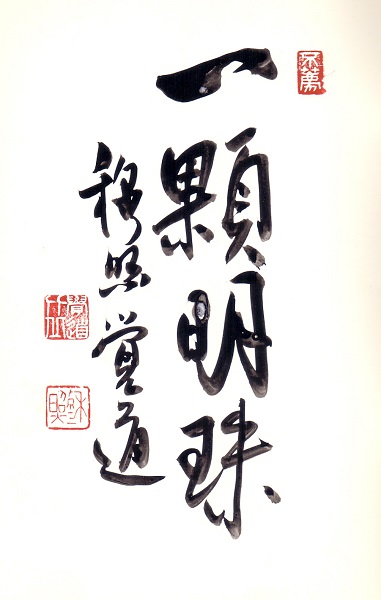

【一顆明珠】 Ikka myōju “One Bright Pearl ”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ikka_my%C5%8Dju

Calligraphy by 横井覚道 Yokoi Kakudō (written for Gabor Terebess in the early 1970s)

An Introduction to Buddhism and Zen

by Yokoi Kakudō

Translated by Ryugen Ogasawara, Ryojun Victoria

Tokyo, Zen Institute, Komazawa University, 1972. 48 p. [with the original Japanese text, pp. 29-48.]

FOREWORD

Recently I was requested by Komazawa University to make a

study tour abroad. As I planned to visit the United States

during my travels, I notified a priest friend living there of my

plans. He wrote back asking me to give lectures on Buddhism

and guidance in Zen at his temple because of the great interest

in these subjects on the part of Americans. He particularly

requested that I center my lectures on the So to school of Zen

Buddhism which is not, as yet, as well known in the West a

Rinzai Zen.

The following booklet is an attempt to answer his request. I

have included sections not only on Buddhism in general and

Soto Zen in particular, including its founder in Japan, Dogen,

and his chief work the Shobogenzo; but I have also attempted

to give a short explanation of the relationship of Zen

Buddhism to Japanese culture in general. The material

included in this booklet is based on previously published texts

in Japanese which are re-published here in their original form

as well as in English translation.

Due to lack of preparatory time there are undoubtedly many

mistakes in this text. I would be deeply appreciative if my

readers would point them out to me so that they can be

corrected in future editions. Finally, I would like to express

my appreciation to Ryugen Ogasawara and Ryojun Victoria,

who helped in the English translation, as well as Shoryu

Ishizuki and Tokiko Tanaka, who also rendered generous

assistance. It is my sincerest hope that this booklet may be r

some small assistance to English-speaking peoples in their

understanding of Buddhism and Zen, and enable them,

however slightly, to near the final emancipation of Nirvana.in Gassho,

Kakudo Yokoi

pp. 19-28:

ZEN

The Origin of Zen and its Development

Zen is one of the important aspects of Buddhism. It is also the

method for realizing that perfect state known as enlightenment.

The word "Zen" itself is the Japanese pronounciation

of a Chinese character which itself was the

phonetic equivalent in Chinese of the original Sanscrit word

dhyana, or jhana as it is pronounced in Pali. When translating

the meaning, instead of simply the sound, of these Indian

expressions the Chinese used Chinese characters meaning

"quiet thinking", "deepen one's thinking" and "forsaking

evil". Even in ancient Indian religious classics, such as the

Upanisadas, mention can be found of the practice of Zen.

This accounts for the fact that losing oneself in meditation

while seated under a tree is a practice carried on not only by

Buddhists but by Hindus and Jains as welL

It was the historical Buddha, Gautama Siddhartha, however,

who used Zen meditation as the way to awaken to the unity of

his mind and body, free himself from desire, and realize

enlightenment. Gautama taught that right meditation was the

most important aspect of the eight-fold noble path leading to

enlightenment. Misunderstanding this teaching, however, there

gradually developed among the community of monks, or

Samgha, a tendency to practice zazen for the realization of

one's own personal enlightenment.

With the emergence of Mahayana Buddhism around the l st

century A.D. this tendency was severely criticized, and the

practice of Zen became understood as a practice which was

undertaken for the benefit of others. In this way Zen became

established as one of the six paramitas, i.e. methods for

crossing over from this shore of birth and death to the other

shore of enlightenment. Thus Zen changed from a selfcentered,

self-righteous practice to one undertaken from

altruistic motives as an active religious expression. This type of

Zen was carried to China where, combining with traditional

Chinese thought, if formed the unique Zen Sect as it is known

today.

Something of Zen thought had already been introduced to

China as early as the Eastern Han Dynasty (A.D. 25 to 220);

however, it was not until the famous Indian Zen priest

Bodhidharma began preaching in China in the beginning of the

Northern Wei Dynasty (A.D. 386-533) that Zen became a

distinct entity in that country. Zen as taught by Bodhidharma

is said to be expressed in the words Gvoju-hekikan] i.e.

meditation. Such meditation is said to benefit oneself and

others; and beginning with Bodhidharma passing on his'

teaching to his foremost Chinese disciple Hui-k'o (487-593) it

was passed on for six generations from master to disciple, the

sixth master, or Patriarch, being Hui-neng (638- 713).

Four of Bodhidharma's most famous expressions are: (1) no

dependence upon the words and letters of the scriptures (2)

transmission of the doctrines without dependence upon

scriptures or other writings (3) direct pointing to one's mind

and seeing into one's own nature and (4) the realization that

one is no different from a Buddha. These most clearly

express the unique character of Zen. Another Chinese priest,

Tsung-mi (780-840) divided Zen into five types: (1) heretical

Zen (2) laymen's Zen (3) Hinayana Zen (4) Mahayana Zen and

(5) the Buddha's Zen. He stated that the Zen of Bodhidharma

and his successors was that of the fifth type, i.e. the Buddha's

Zen, and that this Zen differed from that taught by either the

Tendai Sect or other Buddhist masters.

In Japan the Rinzai Zen Sect was first introduced by the

Japanese priest Eisai at the beginning of the 12th century.

Following him, Dogen (1200-1253), founder of the Soto Zen

Sect, completed the systematic exposition of Zen thought.

Both in China and Japan Zen has exerted a great influence on

the arts, on philosophy, and on thought in general. In China

this influence was particularly strong on the paintings of the

Sung (960-1279) and Yuan (1280-1368) Dynasties, as well as

on New Confucianist philosophy. In Japan the tea-ceremony,

the architecture of the homes. of feudal warriors, and Noh

dramas also bear witness to the influence of Zen thought.The Meaning of Zazen

Zazen begins with assuming the correct posture and regulating

one's breathing. Since our human mind can not be easily

controlled, we sit in meditation in order to control it. When

we sit in meditation correctly under the guidance of a Zen

master, our delusions cease and we can enter into a calm state

of mind without clinging to anything. This state of mind is

equal to that of a Buddha. It can and indeed must be

manifested in our human body and mind while we are leading

our ordinary daily life.

One usually sits in either a full or half-lotus position, with eyes

half open so as to prevent sleepiness and irrelevant thoughts.

Zazen is understood as being the concrete actualization of

meditation; and, as such, it has been practiced by various

Indian religions since ancient times.

This form of Zen became prevalent after Bodhidharma arrived

in China. It became more and more predominant in the later

Northern and Southern Sung Dynasties. One school of meditation,

Soto-Zen, gradually came to be known as Mokusho-

Zen, i.e. silent meditation without any thinking. In Rinzai-Zen,

on the other hand, students are given an object of meditation,

known as koan, by their Zen masters. Thus the method of

meditation in Rinzai-Zen is known as Kanna-Zen, i.e. seeking

enlightenment through the use of koan?

The Japanese Zen master Dogen tried to revive the original

zazen as practiced by the Buddha and Bodhidharma. He

advocated the need of true zazen known as shikan-taza" and

wrote the Fukan-zazen-gi (A Recommendation for the practice

of Zazen). The Rinzai Zen master in Japan, Hakuin, developed

Rinzai-zen and added some new interpretations. He also wrote

a short verse called Zazen-wasan (A Hymn in Praise of Zazen).

As may be seen from Dogen's exhortation for shikan-taza,

the practice of zazen forms the core of Zen training. This is in

sharp contrast to other Japanese priests such as Honen

(1133-1212), founder of the Jodo Sect, who advocated

complete dedication to the practice of nembutsu, i.e. invoking

the name of Amida-Buddha in order to be reborn in his Pure

Land. It should be remembered, however, that zazen is not

just simply a way to realize enlightenment or become a

Buddha. Rather it is a method wherein one completely denies

discriminative thinking, finding fulfillment in one's unity with

the universe.The Zazen Posture

In the practice of zazen one should first of all have a desire to

follow the way of the Buddha and aspire to save all sentient

beings. Next one should have sufficient rest and food and be

dressed comfortably, taking care that one's clothing is neat

and clean. As for a place, a quiet spot is desirable.

Before assuming the sitting position one should bow with

hands pressed palm to palm in the gassho position. Then,

laying out a fairly soft mat or pad some three feet square,

place a small circular cushion measuring abou t one foot in

diameter on it to sit on. You may either sit in the full-lotus

posture, placing the foot of the right leg on the thigh of the

left and the foot of the left leg on the thigh of the right (or the

reverse) or you may use the half-lotus posture which is done

by putting the foot of the left leg on the thigh of the right.

The next step is to rest the right hand in the lap, palm upward,

and place the left hand, palm upward, on top of the right

palm. The tips of the thumbs should lightly touch each other.

After straightening the spinal column, control your breathing

while keeping your eyes half opened, looking at a

spot approximately three feet in front of you. After having

completed your sitting you once more bow with hands in the

gassho position and leave your place of meditation with hands

placed firmly on your chest, the left fist covered with the right

palm.1

Gyoju-hekikan: Buddha attained his enlightenment while sitting in

meditation under a bodhi tree, marking the beginning of Buddhism.

Later on, the method of practicing meditation changed gradually,

particularly that of Mahayana Buddhism. In this school meditation was

practiced with using various spiritual words as objects of meditation.

These words were thought to express the Buddha or the Truth.

Bodhidharma, however, sat in meditation facing the wall; an act which

seems to be on its face quite unimportant and useless. Yet, by emphasizing

"realizing one's True Self", as did Bodhidharma, his meditative

practice could be said to be a revival of the original Buddha's meditation.

Thus Dogen's meditation, as expressed in his words of shikan-taza, may

also be said to be the same as that of the original Buddha; for it, too,

finds its basis in Bodhidharma's meditation.2

Koan: the word koan has two meanings. In a broad sense it means

the ultimate truth of the Dharma, Buddhist teachings. In a narrow sense,

it means the principles, attitudes and deeds of Zen masters. In Rinzai

Zen, these anecdotes concerning past Zen masters are used as objects of

meditation. For example, "What is the sound of one hand clapping?"

In Soto Zen, however, koan are not used as objects of meditation,

although their use as reference sources by Zen trainees is allowed.

Dogen himself taught that koan were not simply limited to anecdotes of

past Zen masters; but, in fact, all phenomena in the universe including

our very existence itself may be considered as koan.3

Shikan-taza: literally "just sitting in meditation without thinking

of any particular subject". This form of zazen as practiced

in Soto-Zen is different from that practiced in Rinzai-Zen in which one

u.ses a koan (see Note"), consciously wishing to attain enlightenment

during meditation.

In Soto-Zen, then, it is believed that zazen itself is the object and

enlightenment is in the very midst of zazen. There is no distinction

between zazen and enlightenment, satori. Thus, in the practice of

zazen, the true dharma and its embodiment are expressed.ZEN MASTER DOGEN

Dogen (1200-1253) was the founder of the Soto Zen sect in

Japan. He was born in Kyoto to noble parents, his father being

Koga Michichika, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, and his

mother the daughter of Fujiwara Motofusa, the Prime Minister.

He lost both of his parents at an early age, however, and

began his formal study of Buddhism at the age of thirteen.

After receiving the precepts and shaving his head in the

initiation ceremony for a Buddhist monk the following spring,

he became a disciple of Koen, chief abbot of the Tendai Sect.

During his subsequent training he experienced the following

doubt: "Why, if all sentient beings innately possess

the Buddha-nature, is it necessary for the Buddhas of the past,

present and future to undergo such long and rigorous

training?" Searching for an answer, Dogen visited Koin of

Onjoji temple who, in turn, advised him to visit Eisai of

Kenninji temple. His doubt being partially cleared up by Eisai

he continued to train under him and, upon his death, his

foremost disciple Myozen.

At the age of twenty-four Dogen accompanied Myozen on a

pilgrimage to China where they visited numerous Buddhist

monasteries and temples. He was particularly impressed by

Chief Abbot Ju-ching of the T'ien-t'ung-ssu monastery. After

having trained under him for a total period of four years,

during which time he realized full enlightenment, Dogen

returned to Japan in 1227. Following his return Dogen began

propagating Buddhism as well as writing various treatises

concerning it in the vicinity of Kyoto, Japan's capital then.

A few years later he had a temple named Koshoji constructed,

and he became its first chief priest.

In 1243, after moving to a more mountainous area near the Sea

of Japan, Dogen had the monastery of Eiheiji constructed in

what is now Fukui Prefecture. Four years later he was

requested to come to the new capital city of Kamakura by

Hojo Tokiyori, then the military ruler of all Japan. In

Kamakura he continued to propagate Buddhism and conferred

the bodhisattva precepts on Tokiyori. In 1250, after having

returned to Eiheiji, he was presented with a purple robe by

Emperor Go-saga; however, Dogen refused to wear it or be in

any way associated with the power system of his day.

Dogen is well-known for having written the Shobogenzo (see

under Shobogenzo), a religious philosophical work unexcelled

in Japan. He also wrote other treatises on Buddhism including

one on the practice of zazen, the Fukanzazengi, and one on

the regulations to be followed in a Zen monastery, the

Eihei-shingi. A collection of Dogen's sayings and lectures in ten

chapters, the Eihei-koroku, is also well-known in Japan.ZEN MASTER KEIZAN

Born in the latter part of the Kamakura period Zen Master

Keizan (1267 - 1325) was destined to become the founder of

Sojiji, one of the two head temples of the Soto Zen denomination,

Soto-shu. He was born in Fukui Prefecture on Japan's

western coast. At the age of thirteen he entered the Buddhist

priesthood as a disciple of Koun Ejo, Dogen's successor and

second chief priest of Eiheiji. Upon Ejo's death Keizan studied

under Tettsu Gikai, the third chief priest of the temple, subsequently

devoting himself to establishing numerous temples,

such as Jomanji in Tokushima Prefecture, and Eikoji, Kokoji,

and Jojuji in Ishikawa Prefecture. Eventually he became the

chief priest of Daijoji in Ishikawa Prefecture, where he devoted

himself to teaching for ten years. In 1321 he was requested by

Joken-risshi to become the chief priest of Shogakuji in

Ishikawa Prefecture. Keizan renamed the temple Shogaku-zan

Sojiji. Later Emperor Go-daigo made the temple an Imperial

prayer temple. Since then Sojiji, together with Eiheiji, has

been regarded as a head temple of the Soto-shu.

Keizan's writings include the Denko-roku, Keizan-shingi,

Zazen-yoj in-k i, Sankon-zazen-setsu, etc.SHOBOGENZO

The Shobogenzo (A Treasury of the Eye, i.e. of the opened

Mind's Eye, of the True Dharma) was written by the founder

of the Soto Zen Sect in Japan, Dogen. Within it are contained

ninety-five different discourses on Buddhism which were

written in the twenty-three year period between 1231-1253.

The discourses were originally presented as sermons to

Dogen's disciples while he was in residence at either the

Anyoin, Koshoji, or Eiheiji temples. In written form the

discourses are recorded either in pure Japanese or in a

combination of Japanese and Chinese.

The Shobogenzo represents Dogen's attempt to transmit the

essence of Buddhism as it is understood in the Zen Sect. This

essence finds its basis in such practices as "learning the true

meaning of human life through study under a Zen master" and

"deepening one's true humanity through the practice of zazen".

The discourses encompass not only the fundamental teachings

of Buddhism but they also deal with uniting these teachings

with one's daily actions as well. Furthermore, the discourses

are not written from a narrow sectarian point of view but

rather from a perspective which transcends sectarianism and

makes a unique contribution to our understanding of life.

In the chapter entitled, Genjo-Koan (The Manifestation of

the Koan) Dogen wrote, "To study Buddhism is to study

one's Self. To study one's Self is to forget one's Self'. These

two sentences may be said to most directly express the essence

of this work. There have been many commentaries written on

the Shobogenzo, the most important of which have been put

together in the ten volume Shobogenzo Chukaizensho (A

Collection of Commentaries on the Shobogenzo). Another

work by the same name but written by a different author, the

Chinese priest Ta-hui (1089-1163) of the Rinzai Zen Sect, is

also in existence. It consists of six chapters.