ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

佚斎樗山 Issai Chozan (1659-1741)

Pen name of 丹羽十郎右衛門忠明 Niwa Jūrōzaemon Tadaaki

aka 佚斎樗山子 Issai Chozanshi, Chozan Shissai, Niwa Chozan

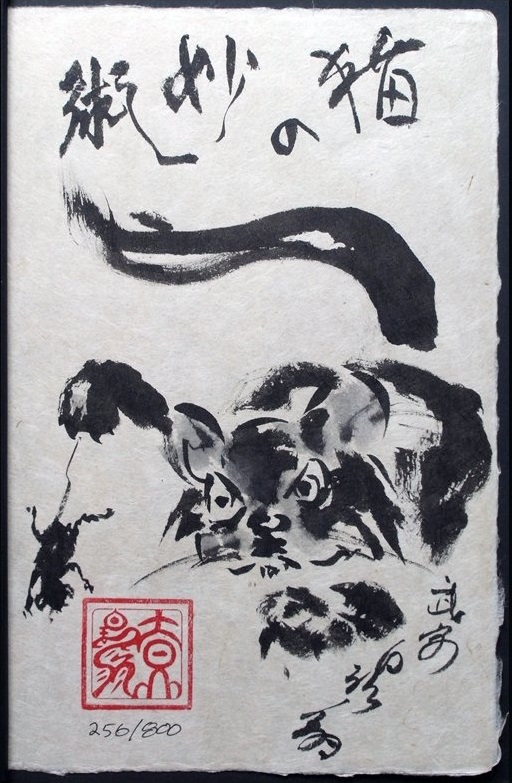

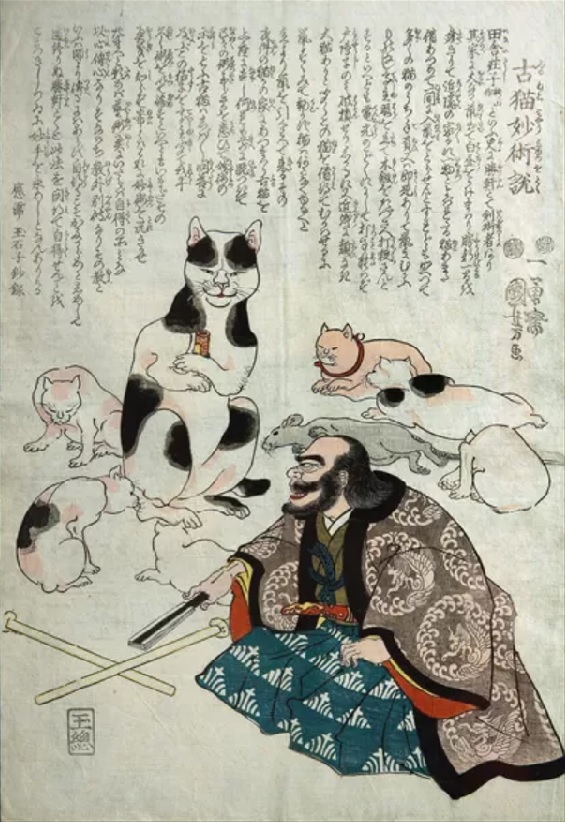

猫の妙術 Neko no myōjutsu

(English:) The Cat's Eerie Skill / The Cat's Uncanny Skill /

The Mysterious Technique of the Cat

(Magyar:) A csodálatos macska / A macska fantasztikus tudománya

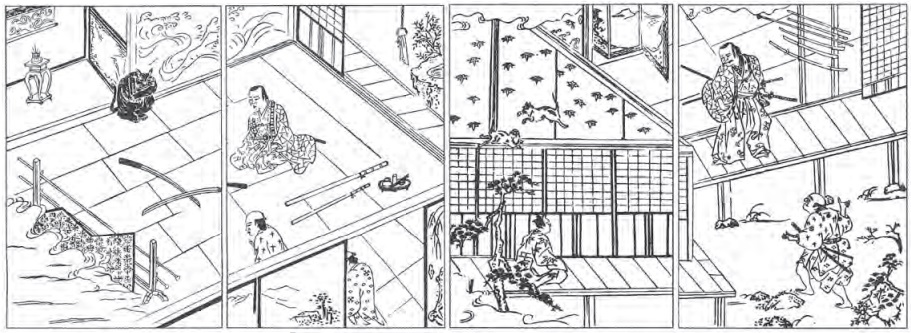

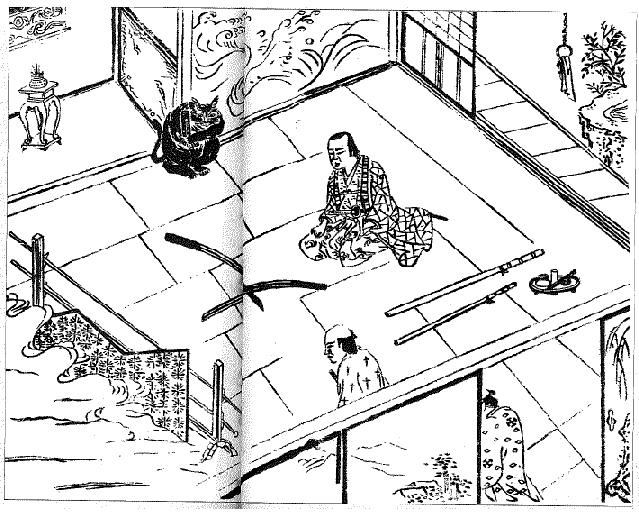

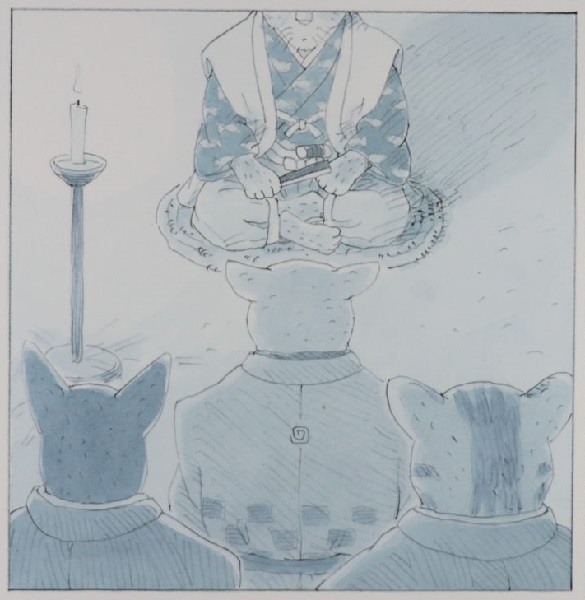

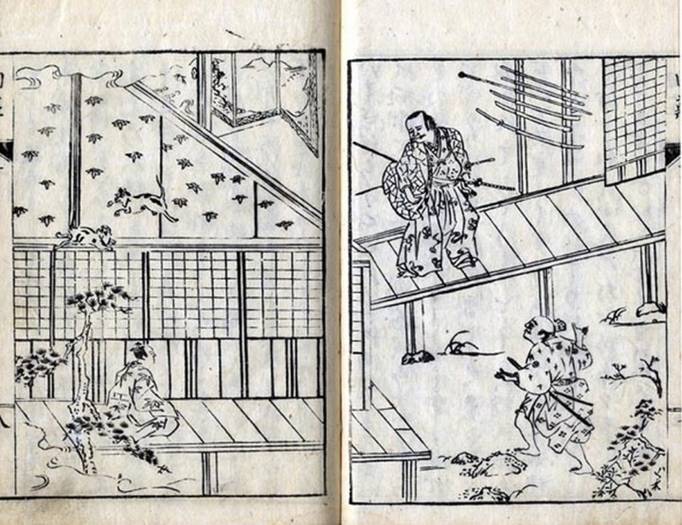

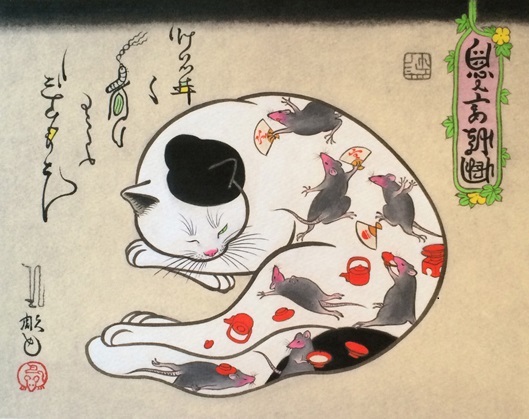

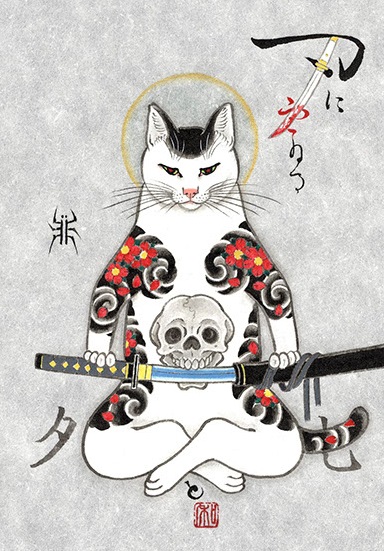

Illustrations from the 田舎荘子 Inaka sōji

written by the samurai Niwa Jūrōzaemon Tadaaki (pen name Issai Chozanshi, 1659-1741) in 1727

Tartalom |

Contents |

A csodálatos macska PDF: A macska fantasztikus tudománya

Macskás könyvek: PDF: Kawamura Genki: Ha a macskák eltűnnének a világból PDF: Egy macska Párizsban PDF: Az Igazi Macska PDF: Macska tulajdonosok kézikönyve PDF: Miért csinálja...? A macska |

The Marvelous Cat PDF: The Swordsman and the Cat The Mysterious Technique of the Cat

Mysterious Technique of the Cat Secret of Kendo and “The Cat's Eerie Skill” The Cat's Eerie Skill Tattooed Cat Designs PDF: The monastery cat in crosscultural perspective. PDF: Zen and Confucius in the Art of Swordsmanship PDF: Zen for cats PDF: The Zen Cat PDF: The Zen of Cat PDF: The Philosopher Cat and her first book The Cat and the Tao

Zen und Schwert in der Kunst des Kampfes. Die wundersame Technik der Katze

L'Art du Chat merveilleux Histoire de l'art merveilleux d'un chat PDF: Merveilleux chat et autres récits Zen PDF: Zen pour chats

PDF: L'arte del gatto meraviglioso |

Ito Tenzaa Chuya zen-mester tanítása

A csodálatos macska

Németből fordította: Hetényi Ernő (1912-1999)

In: Dr. Hetényi Ernő: A buddhizmus zen-aspektusa japán szövegek tükrében, Kőrösi Csoma Sándor Buddhológiai Intézet, Buddhista Misszió, Budapest, [Házi soksz.], 1986, 38-43. oldal [Javított szöveg, online szerk.]

Forrása:

Karlfried Graf Dürckheim (1896-1988): Die wunderbare Kunst einer Katze

[Japán kardvívó iskola szájhagyománya a 17. századból; 寺本丈晴 TERAMOTO Takeharu és 桥本文雄 HASHIMOTO Fumio fordítása nyomán németre átdolgozta K. Dürckheim]

Shoken vívómester házában egy hatalmas patkány garázdálkodott. A mester, megunva az egyre jobban kellemetlenkedő állat üzelmeit, macskáját a házba vitte, és rázárta az ajtót. A patkány azonban nem ijedt meg a macskától, úgy megharapta, hogy az rémülten menekült. A házigazda erre szomszédaitól szerzett néhány bátor macskát, és ezeket zárta be a házba.

A patkány egy sarokban lapult, de mihelyt egy macska közelíteni merészelt, támadott és megfutamította ellenfelét. A patkány oly félelmetes volt, hogy a macskák másodszor már nem is merészkedtek a közelébe.

Shoken igen megharagudott, és maga fogott a patkány üldözéséhez. Az állat azonban olyan ügyesen kerülte ki a vívómester ütéseit, hogy mindig megmenekült. Ezután a házigazda ily szavakkal fordult szolgájához:

– Mondják, hogy él a környéken egy híres patkányfogó macska, menj és kerítsd elő! A szolga távozott, és nemsokára megjelent a macskával. Az állat nem látszott sem különösen okosnak, sem különösen vadnak. Shoken nem is remélt tőle eredményt. De mivel mást nem tehetett, ezt is bezárta a házába.

A macska nyugodt léptekkel indult előre, mintha semmi veszélytől sem tartana. A patkány összehúzta magát, és mozdulni sem mert. A macska lassan folytatta útját, és végül egyszerűen torkon ragadta a patkányt.

Este Shoken házában gyűlést tartottak a megvert macskák. A fő helyet az öreg győztes macskának ajánlották föl, és miután tisztelettel köszöntötték, ily szavakkal fordultak hozzá:

– Mi valamennyien jó hírnévnek örvendtünk, mesterségünket lelkiismeretesen gyakoroltunk, karmainkat gondosan élesítettük, hogy eredményesen küzdhessünk a patkányok és más ragadozók ellen. De soha nem gondoltuk volna, hogy ilyen patkány is létezik. Te vajon milyen módszert alkalmaztál? Kérünk, ne tartsd titokban tudományodat! Az öreg macska elmosolyodott, és ezt válaszolta:

– Ti, ifjú macskák, valóban derék állatok vagytok, de nem ismeritek a helyes utat. Ezért, ha valami váratlannal kerültök szembe, elvétitek a célt. No de meséljétek csak el nekem, hogyan gyakoroltatok? Egy fekete macska így válaszolt:

– Híres patkányfogó családból származom, és így magam is ezt a hivatást választottam. Két méternél magasabbra ugrom, képes vagyok kis lyukakba befurakodni. Éberen alszom, és nyomban fölpattanok, ha patkány közelít. Eddig még mindig elfogtam ellenfelemet. Ez a legutóbbi patkány azonban erősebbnek bizonyult nálam, és én csúfos vereséget szenvedtem. Szégyellem magam.

Az öreg macska válasza így hangzott:

– Gyakorlási módszered nem volt más, mint fizikai erőkifejtés. Szellemedet ez a kérdés foglalkoztatja: miként győzhetek? Ezek szerint még célhoz ragaszkodsz! Ha az öregek „technikát” tanítottak, úgy ezt azért tették, hogy ezzel az ösvény egy fajtáját ismertessék. Módszerük egyszerű volt, mégis a legmagasabb rendű igazságot tartalmazta. Az utókor azonban pusztán a technikára helyez súlyt. Eközben sok mindent kitaláltak, mint például: ha ezt vagy amazt gyakoroljuk, akkor ez vagy amaz lesz az eredmény. És végeredményben mi ez? Nem több, mint ügyeskedés. És mindenkor ez a helyzet, ha technikára és eredményre gondolunk, és közben kizárólag elménkre támaszkodunk. Szállj tehát magadba, és gyakorolj megfelelő módon!

Ezután a tigrisbundájú macska szólalt meg:

– A lovagi művészetben úgy vélem, a szellem a legfontosabb. Ezért gyakorlásaim során mindenkor ezt az erőt fejlesztettem. Szellemem, úgy érzem, acélkemény és szabad. Bírja ama erőt, amely a mennyet és földet eltölti. Ha ellenfelem szembetalálja magát ezzel az erővel, úgy megbénul, hogy a győzelem már eleve biztosított. Szinte öntudatlanul támadok, a technikával egyáltalán nem törődöm; ez utóbbi önmagától alakul. De ez a rejtélyes patkány alak nélkül közelített, és nyom nélkül távozott. Arra, hogy tulajdonképpen mi történhetett, nem találok magyarázatot.

Az öreg macska válasza így hangzott:

– Az erő, melyet gyakorlásaid során megszereztél, valóban az, mely a mennyet és a földet megtölti. De a te birtokodban mégsem volt más, mint puszta pszichikai erő, amely nem is mondható kiválónak. Már az a tény, hogy a birtokodban lévő erőnek tudatában vagy, meghiúsíthatja a győzelmet. Személyes éned részt vesz a küzdelemben. Mi történik akkor, ha az ellenfél ereje a nagyobb? Azt képzeled, hogy csupán te birtoklod az erőt, és mindenki más gyengébb nálad? A te szabad és acélos, mennyet és földet eltöltő erőd nem maga a Hatalmas Erő, hanem csupán annak tükröződése szellemedben, Szellemed csak bizonyos körülmények között töltődik fel ama erővel, Így a Hatalmas Erő, amelyről Mencius beszél, és a te erőd különböző forrásból erednek. Egy ősi közmondás szerint a sarokba szorított patkány a macskát is megmarja. Ha az ellenfél halálos csapdában van, úgy megfeledkezik életéről, bajáról; nem gondol győzelemre vagy vereségre. Ennek következtében pedig akarata acélkemény. Hogyan is volna tehát vélt szellemi erőddel legyőzhető?

Ezt követően egy idősebb, szürke macska szólalt meg:

– Valóban úgy van, ahogy mondod. Még a legnagyobb pszichikai erő is formával bíró. És a formával bíró megragadható. Én ezért már régóta a lelkemet fejlesztettem. Tehát nem azt az erőt fejlesztettem, amely a másik szellemét legyőzi. Nem is bocsátkozom küzdelembe. Ellenkezőleg: megbékélni igyekszem ellenfelemmel, szinte eggyé válok vele, és semmiképpen sem tanúsítok ellenállást. A patkány, legyen bár erős, ha támad, nem találhat esetemben semmit, amire támaszkodhatnék. De ez a legutóbbi patkány mégis túltett rajtam. Jött, ment – fölfoghatatlan módon –, mint egy istenség. Ilyesmi még nem fordult elő velem.

Az öreg macska azt felelte erre:

– Amit te megbékélésnek nevezel, nem a lényegiségből fakad, nem a Nagy Természet része. Csinált, mesterséges megbékélés, tehát csel. Tudatosan igyekszel az ellenség támadószellemét megbénítani. És éppen ezért, mert erre gondolsz – bárha csak felületesen is – az ellenfél szándékodat fölismeri. Tudd meg, hogy minden tudatos szándék akadályozza a Nagy Természet rezgéseit, és ilyenformán megakasztja a spontán mozdulat folyamatát. Ha azonban semmire sem gondolunk, akkor mozgásunkat e lényegi rezgés irányítja. Ez esetben valóban nincs megragadható formád, tehát ellenformaként sem jelentkezhet semmi. Hol van ez esetben az ellenfél, aki képes volna ellenállni? A macskák feszülten figyeltek, s az öreg macska kisvártatva folytatta előadását:

– Ne higgyétek, hogy amit tőlem hallottatok, az a legmagasabb rendű. Nem is olyan régen a szomszédos faluban élt egy kandúr. Egész nap aludt. Olyasmi, amit szellemi erőnek nevezünk, nem látszott a megjelenésén. Soha nem látta senki, hogy patkányt fogott volna. De ahol tartózkodott, sehol sem volt patkány található. És ahol csak megjelent, ahol csak feltűnt, ugyanez volt a helyzet: nyoma sem volt patkányoknak.

Egy alkalommal fölkerestem, és magyarázatot kértem. Nem válaszolt. Újra kérdeztem, de ismét csak hallgatott. Nem az volt a látszat, mintha nem akart volna válaszolni, hanem inkább úgy tűnt, mintha nem tudná, mit is feleljen. „Aki tudja, az nem szól – és aki szól, az nem tudja.” Ez a kandúr megfeledkezett önmagáról és megfeledkezett a külvilágról. „Semmivé” vált, és így elérte a szándék nélküliség legfelső fokát. Elmondhatjuk, hogy e fokon valósul meg az isteni lovagi ösvény célja: ölés nélkül győzni.

A magyar fordító elhagyta a szöveg befejező okfejtésését.

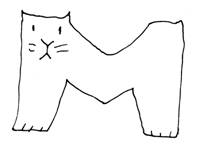

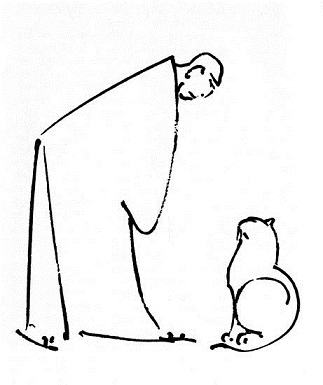

Réber László illusztrációit Terebess Gábor válogatta az alábbi kiadványokból:Matematikai logika kezdőknek 1-2. / Varga Tamás ; Budapest : Tankönyvkiadó, 1962-1969 között: 5 kiadás.

Egyperces novellák / Örkény István ; 2. bőv. kiad.; Budapest : Magvető, 1969.

Gedanken im Keller. Mini-Novellen / István Örkény ; ausgew., übers.: Vera Thies, ill.: László Réber. Berlin : Eulenspiegel, 1979, 1984, 1992.

Macskabölcső : Regény / Kurt Vonnegut ; [fordította Borbás Mária] ; [a verseket Orbán Ottó fordította] ; Budapest : Európa Kiadó, 1978.

Murphy törvénykönyve avagy Miért romlik el minden? / Arthur Bloch ; [ford. Hernádi Miklós]. Budapest : Gondolat, 1985.

Beszélgetések gyerekekkel / R. D. Laing ; [ford. Ferencz Győző]. Budapest : Helikon, 1988.

Murphy magyar törvényei, avagy Miért romlik el minden újra / J. Z. Elky [= Zelki János]. Budapest : Háttér, 1989.

PDF: A macska fantasztikus tudománya

Japánból fordította: 山地征典 Yamaji Masanori

Keletkutatás, 1994 ősz. 71-83. oldal

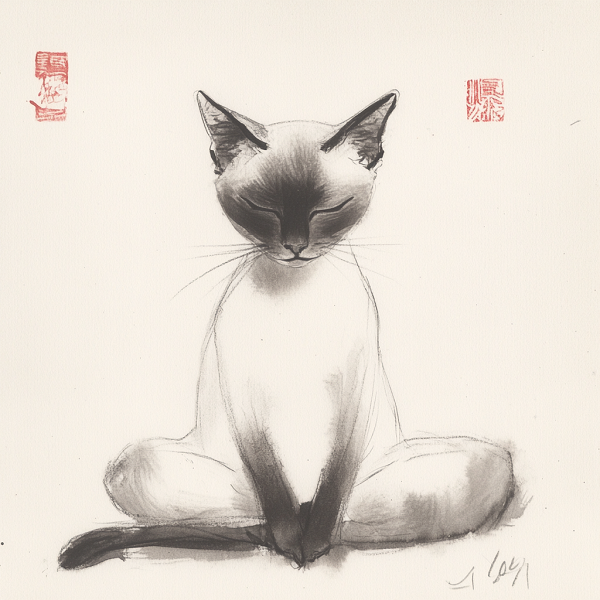

Ill.: Klaus Bertelsmann

Die wunderbare Kunst einer Katze

Von Zen-Meister Ito Tenzaa ChuyaÜbungsanweisung einer altjapanischen Fechtschule, übersetzt aus dem Japanischen von

Takeharu Teramoto und Fumio Hashimoto, bearbeitet von Karlfried Graf Dürckheim

Mit Zeichn. von Klaus Bertelsmann (geboren in 1924) Diesen Text verdanke ich meinem Lehrer im Zen, Takeharu Teramoto. Teramoto, Admiral a. D. und Professor an der

Marineakademie in Tokio, hatte als seine Übung (Gyo) das Schwertfechten. Sein Meister war der letzte Meister einer

Fechtschule, in der seit Anfang des 17. Jahrhunderts die Geschichte der 5 Katzen als geheime Übungsanweisung von

Meister zu Meister gereicht und schließlich ihm von seinem Meister überlassen wurde.

Es war einmal ein Fechtmeister namens Shoken. In seinem Hause trieb eine große Ratte ihr

Unwesen. Selbst am hellen Tage lief sie herum. Da machte der Hausherr einmal das Zimmer zu

und gab der Hauskatze Gelegenheit, die Ratte zu fangen. Die aber sprang der Katze ins Gesicht und

biss sie so, dass sie laut schreiend davonlief. So also ging es nicht. Und so brachte der Hausherr

einige Katzen herbei, die in der Nachbarschaft einen tüchtigen Ruf genossen und ließ sie in das

Zimmer hinein. Die Ratte kauerte in einer Ecke, und sowie eine Katze ihr nahte, sprang sie sie an,

biss sie und schlug sie in die Flucht. So ungestüm sah die Ratte aus, dass die Katzen alle zögerten,

sich noch einmal heranzuwagen. Da wurde der Hausherr zornig und lief selber der Ratte nach, um

sie zu töten. Sie aber entschlüpfte jedem Hieb des erfahrenen Fechtmeisters, und er konnte sie nicht

erwischen. Er schlug dabei Türen, Shojis, Karakamis u. a. entzwei. Aber die Ratte huschte durch

die Luft – schnell wie ein fahrender Blitz, entging jeder seiner Bewegungen und sprang ihm ins

Gesicht und biss ihn. In Schweiß gebadet rief er schließlich seinem Diener zu: »Man sagt, sechs bis

sieben Cho von hier sei eine Katze, die die tüchtigste in der Welt sei. Geh und hole sie her.« Der

Diener brachte die Katze. Sie schien sich nicht viel von den anderen Katzen zu unterscheiden, sah

weder besonders klug, noch besonders scharf aus. So traute der Fechtmeister ihr auch nichts

Besonderes zu, aber er machte die Tür etwas auf und ließ sie hinein. Ganz ruhig und langsam ging

die Katze hinein, so als erwarte sie gar nichts Besonderes. Aber die Ratte fuhr zusammen und

rührte sich nicht. Und die Katze ging ganz einfach und langsam auf sie zu und brachte sie im Maul

heraus.

Ill.: Klaus BertelsmannAm Abend versammelten sich in Shokens Haus die geschlagenen Katzen, baten respektvoll die

alte Katze auf den Ehrensitz, knieten vor ihr nieder und sagten bescheiden: »Wir alle gelten als

tüchtig. Wir alle haben uns auf diesem Wege geübt und uns die Klauen geschärft, um damit jede

Art von Ratten, ja sogar Wiesel und Ottern besiegen zu können. Wir hätten niemals gedacht, dass

es eine so starke Ratte geben könnte. Aber mit was für einer Kunst habt Ihr sie so leicht besiegt?

Machet doch kein Geheimnis aus Eurer Kunst und erzählt uns doch Euer Geheimnis!« Da lachte

die Alte und sprach: »Ihr jungen Katzen, Ihr seid zwar ganz tüchtig. Aber Ihr wisst im rechten Weg

nicht Bescheid. So verfehlt Ihr, wenn etwas Unerahntes Euch begegnet, den Erfolg. Doch erzählt

erst Ihr mir, wie Ihr Euch geübt habt.«Da rückte eine schwarze Katze heran und sagte: »Ich stamme aus einem Haus, das für den

Rattenfang berühmt ist. So entschloss auch ich mich zu diesem Weg. Ich kann Wandschirme von

zwei Meter Höhe überspringen. Ich kann mich durch ein winziges Loch zwängen, durch das sonst

nur eine Ratte durchkommt. Von Kind auf habe ich alle akrobatischen Künste geübt. Auch wenn

ich beim Aufwachen aus dem Schlaf noch nicht ganz da bin, eben dabei, mich wiederzufinden und

sehe da eine Ratte über den Balken laufen – schon habe ich sie. Die Ratte von heute aber war

stärker und ich habe die furchtbarste Niederlage erfahren, die ich in meinem Leben jemals zu

erleiden gehabt. Ich bin beschämt« – Da sagte die Alte: »Worin Du Dich da geübt hast, ist eben

nichts als nur Technik! (shosa – die reine physische Kunst.) Dein Geist ist aber besetzt mit der

Frage: Wie gewinnen? So haftest Du ja noch am Zielen! Wenn die Alten ‚Technik‘ lehrten, so

taten sie es, um damit eine Weise des Weges (michisuji) zu zeigen. Ihre Technik war einfach,

beschloss jedoch die höchste Wahrheit in sich. Die Nachwelt aber beschäftigt sich nur noch mit

Technik. Dabei erfand man zwar vieles, so nach dem Rezept ‚Wenn man dies und das übt, dann

kommt dies und jenes dabei heraus.‘ Was aber kommt dabei heraus? Nichts als eine

Geschicklichkeit. Unter Preisgabe des überlieferten Weges entstand so unter Aufbietung von viel

Klugheit der Wettbewerb in Technik bis zur Erschöpfung, und nun kommt man nicht weiter. Das

ist immer so, wenn man an Technik und Erfolg denkt und dabei ausschließlich die Klugheit

betätigt. Zwar ist die Klugheit eine Funktion des Geistes, wenn sie aber nicht auf dem Weg fußt und

allein auf Geschicklichkeit abzielt, dann wird sie zum Ansatz von Falschem und das Errungene

zum Übel. Also geh in Dich und übe von nun an im rechten Sinn weiter.«

Ill.: Klaus BertelsmannDarauf rückte eine große Katze mit einem Tigerfell heran und sprach: »In der Ritterkunst

kommt es, so meine ich, nur auf den Geist an. So habe ich mich daher seit jeher in dieser Kraft

geübt (ki wo neru). So ist mir, als sei mein Geist ‚stahlhart‘ und frei und geladen vor dem Geist,

der Himmel und Erde erfüllt (Menzius). Sehe ich den Feind, schon schlägt dieser allgewaltige Geist

ihn in Bann und ich gewinne den Sieg schon im voraus. Erst dann gehe ich vor! Ganz unbewusst,

so wie es die Lage erfordert. Ich richte mich nach dem ‚Klang‘ meines Gegners, banne die Ratte,

wie es mir beliebt, nach links oder nach rechts und komme jeder Wendung entgegen. Um die

Technik als solche kümmere ich mich überhaupt nicht. Die kommt von selber. Eine Ratte, die über

den Balken läuft, starre ich nur an, und schon fällt sie herunter und ist mein. Aber diese

geheimnisvolle Ratte da kommt ohne Gestalt und geht ohne Spur. Was ist das? Ich weiß es nicht.«Da sagte die Alte: »Worum du dich da bemüht hast, ist wohl das Wirken, das aus der großen

Kraft kommt, die Himmel und Erde erfüllt. Aber was du gewonnen hast, ist doch nur eine

psychische Kraft und ist nicht von dem Guten, das den Namen des Guten verdient. Allein schon die

Tatsache, dass du dir der Kraft, mit der du siegen willst, bewusst bist, wirkt dem Siege entgegen.

Dein Ich ist im Spiel. Wenn das des anderen aber stärker ist als das deine, was dann? Wenn du den

Feind mit dem Übergewicht deiner Kraft besiegen willst, stellt er dir die seine entgegen. Bildest du

dir ein, allein stark zu sein und alle anderen schwach? Wie aber soll man sich verhalten, wenn es

etwas gibt, das man beim besten Willen nicht mit dem Übergewicht der eigenen Kraft besiegen

kann – das ist die Frage! Was du da als ‚frei‘ und ‚gestählt‘ und als ‚Himmel und Erde

erfüllend‘ in dir fühlst als geistige Kraft, das ist nicht die große Kraft (ki no sho) selbst, sondern

nur ihr Abglanz in dir. Es ist dein eigener Geist, also nur der Schatten des großen Geistes. Es gibt

sich zwar so, wie die große Kraft, in Wirklichkeit aber ist es etwas völlig anderes. Der Geist, von

dem Menzius spricht, ist stark, weil er von großem Klarsinn bleibend erhellt ist. Dein Geist aber

gewinnt seine Kraft nur unter bestimmten Bedingungen. Deine Kraft und die, von der Menzius

spricht, haben verschiedenen Ursprung, und so ist auch ihr Wirken verschieden. Sie unterscheiden

sich wie der ewige Strom eines Flusses, z. B. des Yangtsekiang, und eine plötzliche Flut, die über

Nacht kommt. Was aber ist der Geist, den man bewähren soll, wenn einem etwas gegenübersteht,

das von keiner bedingten Geisteskraft (kisei) besiegt werden kann – das ist die Frage!

Ill.: Klaus BertelsmannEin Sprichwort sagt: ‚Eine Ratte in der Klemme beißt auch die Katze.‘ Ist der Feind in der

Todesklemme, ist er auf nichts angewiesen. Er vergisst sein Leben, vergisst alle Not, vergisst sich

selbst, ist frei von Sieg und Niederlage. Und darum ist ein Wille wie Stahl. Wie könnte man ihn mit

einer Geisteskraft besiegen, die man sich selbst zuschreibt?«Nun rückte eine ältere graue Katze langsam heran und sagte: »ja, wirklich, es ist wie Ihr sagt.

Die psychische Kraft hat, so stark sie auch sein mag, in sich selbst eine Form (katachi). Was aber

Form hat, so klein es auch sei, es ist fassbar. Daher habe ich seit langem meine Seele (kokoro, die

Herzkraft) geübt. Ich übe nicht die Kraft aus, die den andern geistig überwältigt (das ‚sei‘, wie die

zweite Katze). Ich schlage mich auch nicht herum (wie die erste Katze). Ich versöhne mich mit

meinem Gegenüber, lasse mich mit ihm eins werden und widersetze mich ihm überhaupt nicht. Ist

der andere stärker als ich, so gebe ich einfach nach und bin ihm gleichsam zu Willen. Meine Kunst

besteht gewissermaßen darin, die fliegenden Kieselsteine in einem losen Vorhang aufzufangen.

Eine Ratte, die mich angreifen will, mag noch so stark sein, sie findet nichts vor, worauf sie sich

stürzen, nichts, woran sie ansetzen könnte. Aber die Ratte von heute ging einfach nicht auf mein

Spiel ein. Sie kam und ging unfassbar wie Gott. Dergleichen habe ich noch nie gesehen.«Da sagte die Alte: »Was du Versöhnlichkeit nennst, kommt nicht aus dem Wesen, nicht aus der

Großen Natur. Es ist eine gemachte, künstliche Versöhnung, ein Kniff. Bewusst willst du damit

dem Angriffsgeist des Feindes entgehen. Weil du aber, und sei es auch noch so flüchtig, daran

denkst, so merkt er ja deine Absicht. Gibst du dich aber in solcher Geistesverfassung

‚versöhnlich‘, so kommt dein dem Angriff zugewandter Geist nur durcheinander, wird getrübt,

und die Präzision deiner Wahrnehmung und deines Handelns ist gestört. Was immer du mit

bewusster Absicht tust, schränkt die ursprüngliche und aus dem Verborgenen wirkende

Schwingung der Großen Natur ein, stört den Fluss ihrer spontanen Bewegung. Wo sollte da

Wirkkraft herkommen? Nur wenn man wenn du nichts machst, sondern dich mit deiner Bewegung

der Schwingung des Wesens (shizen no ka) überlässt, hast du keine greifbare Form mehr, und

nichts auf Erden kann als Gegen-Form auftreten; und dann gibt es auch keinen Feind mehr, der

widerstehen kann.«»Ich bin durchaus nicht der Meinung, dass alles, worin Ihr Euch geübt habt, zwecklos sei. Alles

und jedes kann eine Weise des Weges sein. Auch Technik und Tao können ein und dasselbe sein

und dann ist der große Geist, das ‚Waltende‘, schon in ihr mitenthalten und bekundet sich auch im

Handeln des Leibes. Die Kraft des großen Geistes (ki) dient der Person des Menschen (ishi).

Wessen ki frei ist, der kann mit unendlicher Freiheit allem in der rechten Weise begegnen. Wenn

sein Geist sich versöhnt, wird er, ohne irgendeine besondere Kraft im Kampf einzusetzen, auch

nicht an Gold oder Stein zerbrechen. Nur auf eines kommt es an: dass kein Hauch von Ich-

Bewusstsein im Spiel sei, sonst ist alles verdorben. Wenn man auch noch so flüchtig an all das

denkt, so ist es nur etwas Erkünsteltes. Es kommt nicht aus dem Wesen, nicht aus der

ursprünglichen Schwingung des Weg-Körpers (do-tai). Dann aber wird auch der Gegner einem

nicht zu Willen sein, sondern seinerseits widerstehen. Was für eine Weise oder Kunst also soll man

gebrauchen? Nur wenn du in jener Verfassung bist, die frei ist von jeglichem Ich-Bewusstsein,

wenn du handelst ohne zu handeln, ohne Absicht und Tricks, im Einklang mit der großen Natur,

bist du auf dem rechten Wege. So lasse man jegliche Absicht, übe sich in der Absichtslosigkeit und

lasse es einfach aus dem Wesen geschehen. Dieser Weg ist ohne Ende, unerschöpflich.«Und dann fügte die alte Katze noch etwas Erstaunliches hinzu: »Ihr müsst nicht glauben, dass

das, was ich euch hier sagte, das Höchste sei. Es ist nicht lange her, da lebte in meinem

Nachbardorf ein Kater. Der schlief den ganzen Tag.Irgend etwas, das nach geistiger Kraft aussah, war nicht an ihm zu bemerken. Er lag da wie ein

Stück Holz. Niemand hatte ihn je eine Ratte fangen sehen. Aber wo er war, gab es ringsherum

keine Ratten! Und wo auch immer er auftauchte oder sich niederließ, ließ keine Ratte sich sehen.

Ich suchte ihn einmal auf und fragte ihn, wie das zu verstehen sei. Er gab keine Antwort. Ich fragte

ihn noch dreimal. Er schwieg. Aber eigentlich war es nicht so, dass er nicht antworten wollte,

sondern er wusste offenbar nicht, was er antworten sollte. Aber so ist das ja: ‚Wer es weiß, der sagt

es nicht, und wer es sagt, der weiß es nicht.‘ Dieser Kater hatte sich selbst vergessen und so auch

alle Dinge im Kreis. Er war ‚nichts‘ geworden, hatte den höchsten Stand der Absichtslosigkeit

erreicht. Und hier kann man sagen, er hatte den göttlichen Ritterweg gefunden: Zu siegen ohne zu

töten. Dem stehe ich noch weit nach.«Shoken hörte dies wie im Traum, kam herbei, grüßte die alte Katze und sagte: »Nun übe ich

mich seit langem schon in der Fechtkunst, aber das Ende habe ich noch nicht erreicht. Ich habe

Eure Einsichten vernommen und glaube, den wahren Sinn meines Weges verstanden zu haben, aber

inständig bitte ich Euch, sagt mir doch noch etwas mehr über Euer Geheimnis.« Da sprach die Alte:

»Wie kann das zugehen? Ich bin nur ein Tier und die Ratte ist meine Nahrung. Wie könnte ich über

menschliche Dinge Bescheid wissen! Ich weiß nur soviel: Der Sinn der Fechtkunst liegt nicht bloß

darin, über einen Gegner zu siegen. Sie ist vielmehr eine Kunst, mit der man zu gegebener Stunde

in die große Klarheit des Lichtgrundes von Tod und Leben gelangt (Seishi wo akiraki ni suru). Ein

wahrer Ritter sollte mitten in aller technischer Übung immerzu die geistliche Übung dieses

Klarsinnes pflegen. Hierzu aber muss er vor allem die Lehre vom Seinsgrund von Leben und Tod,

von der Todesordnung (shi no ri) ergründen. Den großen Klarsinn gewinnt aber nur, wer frei ist

von allem, was ihn von diesem Weg abbringt (hen kyoku, Mitten-Ferne), besonders aber von allem

fixierenden Denken. Ist das Wesen und seine Begegnung (shin ki) sich ungestört selbst überlassen,

frei vom Ich und allen Dingen, kann es sich, wann immer es darauf ankommt, in voller Freiheit

bekunden. Wenn Euer Herz aber noch so flüchtig an etwas haftet, wird das Wesen verhaftet und zu

etwas In-sich-Stehendem gemacht. Ist es aber zu etwas In-sich-Stehendem geworden, dann ist mit

dem Ich, das in sich steht auch etwas da, das ihm widersteht. Dann stehen sich zwei gegenüber und

kämpfen gegeneinander um ihren Bestand. Ist das aber der Fall, dann werden die jedem Wandel

gewachsenen wunderbaren Funktionen des Wesens gehemmt, ist die Todesklemme dann da, dann

hat man den dem Wesen eigenen Klarsinn verloren. Wie könnte man in dieser Verfassung dem

Feind in der rechten Haltung begegne und ruhig ‚Sieg und Niederlage‘ ins Auge fassen? Selbst

wenn man den Sieg davon trüge, es ist nur ein blinder Sieg, der nichts mit dem Sinn der wahren

Fechtkunst zu tun hat.Frei sein von allen Dingen bedeutet nun nicht eine leere Leere. Das Wesen als solches hat

keine Eigennatur. Es ist an und für sich jenseits von allen Formen. Es speichert auch nichts in sich

auf. Wenn man aber, was es auch sei, und wie geringfügig es sei, auch nur flüchtig fixiert und

festhält – die große Kraft bleibt daran kleben und das aus dem Ursprung fließende Gleichgewicht

der Kräfte ist dahin. Wird das Wesen auch nur ein wenig durch etwas verhaftet, ist es in seiner

Bewegung nicht mehr frei und strömt nicht mehr ungestört in seiner Fülle hervor. Ist das

Gleichgewicht aus dem Wesen gestört, dann fließt seine Kraft, wo sie dennoch hinkommt, schnell

über; wo sie aber nicht hinkommt, reicht es nicht aus. Wo sie überfließt, bricht gleich zu viel hervor

und es gibt kein Aufhalten mehr. Wo sie nicht hinreicht, ist der wirkende Geist geschwächt und

versagt und kann sich hier wie dort, wenn es darauf ankommt, nicht der Lage entsprechend

bewähren. Was ich Freiheit von den Dingen nenne, bedeutet also nichts anderes als dies: Speichert

man nichts auf, lehnt man sich an nichts an, stellt man nichts fest, dann ist kein Stand und kein

Gegen-Stand da. Weder ein Ich noch ein Gegen-Ich. Wenn dann etwas daher kommt, so begegnet

man ihm wie unbewusst und hinterlässt keine Spur. Im ‚Eki‘ (Buch der Wandlungen) heißt es:

‚Ohne Denken, ohne Tun, ohne Bewegung, ganz still: nur so kann man das Wesen und das Gesetz

der Dinge von innen her und ganz unbewusst bekunden und endlich eins werden mit Himmel und

Erde.‘ Wer die Fechtkunst so ausübt und sie so versteht, der ist der Wahrheit des Weges nahe.«Shoken, als er dies hörte, fragte nun: »Was soll das bedeuten, dass weder ein Ich noch ein

Gegen-Ich, weder ein Subjekt noch ein Objekt, da ist?« Die Antwort der Katze: »Wenn und weil

ein Ich da ist, ist auch ein Feind da. Stellen wir uns nicht als ein Ich hin, so ist auch kein Gegner da.

Was wir also so nennen, ist nur ein anderer Name für das, was Gegensatz bedeutet. Insofern die

Dinge eine Form wahren, setzen sie auch immer eine Gegenform. Wo immer etwas als ein Etwas

feststeht, hat es aber eine Eigenform. Ist mein Wesen zu keiner Eigenform verfasst, so ist auch

keine Gegenform da. Wo kein Gegensatz ist, gibt es auch nichts, was gegen einen antritt. Das aber

heißt: Weder ein Ich noch ein Gegen-Ich ist da. Lässt man sich selbst ganz fallen und wird also frei,

von Grund auf und von allen Dingen, so befindet man sich im Einklang mit der Welt, ist eins mit

allen Dingen in der großen All-Einheit. Auch wenn des Feindes Form ausgelöscht wird, es wird

einem gar nicht bewusst. Nein, nicht dass man sich dessen überhaupt nicht inne würde, aber man

verweilt nicht dabei und der Geist bewegt sich weiterhin frei von aller Fixierung und antwortet

auch im Handeln einfach und frei aus der Mitte des Wesens.Ist der Geist von gar nichts mehr eingenommen und frei von aller Besetztheit, so ist auch die

Welt, so wie sie ist, ganz unsere Welt und mit uns eins. Dies bedeutet, man nimmt sie nun jenseits

von Gut und Böse, jenseits von Sympathie oder Antipathie. Man ist in nichts mehr befangen und

bleibt auch an nichts in ihr haften. Alle Gegensätze, die wir vor uns haben, Gewinn und Verlust,

Gut und Böse, Freud und Leid, kommen aus uns. In der ganzen Weite von Himmel und Erde ist für

uns darum nichts so erkennenswert, als nur unser eigenes Wesen. Ein alter Dichter spricht: ‚Ein

Körnchen Staub im Auge und die drei Welten sind noch zu eng. Ist uns an nichts mehr gelegen, so

ist das kleinste Bett immer noch weit.‘ Das heißt: Dringt ein Körnchen Staub uns ins Auge, so

kann es sich nicht mehr auftun. Denn es dringt etwas dort hinein, wo es helle Sicht nur dann gibt,

wenn nichts darin steckt. Dies mag uns zum Gleichnis dienen für das Sein, das leuchtend

erleuchtendes Licht ist und in sich selbst ledig von allem, was ‚etwas‘ ist. Wenn sich aber etwas

davor stellt, vernichtet die Vor-Stellung seine Tugend. Ein anderer Dichter sprach so: ‚Ist man von

Feinden umstellt, hunderttausend an der Zahl, so wird zermalmt, was man selber an Form ist. Aber

das Wesen ist und bleibt mein, so stark der Feind auch sein mag. In dieses kommt kein Feind je

herein.‘ Konfuzius sagt: ‚Auch eines einfachen Mannes Wesen kann man nicht stehlen.‘ Gerät

aber der Geist durcheinander, dann wendet sich das Wesen gegen uns selbst.«»Dies ist alles, was ich Euch sagen kann. Gehet nun wieder in Euch und forscht selbst in Euch

nach. Ein Meister kann dem Schüler immer nur die Sache mitteilen und sie zu begründen

versuchen. Die Wahrheit zu erkennen und sie sich anzueignen, das vermag immer nur ‚Ich-

Selbst‘. Dies nennt man Selbstaneignung (jitoku).Das Übermitteln erfolgt von Herz zu Herz (ishin denshin). Es ist eine Weitergabe auf

außerordentlichem Wege, jenseits von Lehre und Gelehrsamkeit (kyogai betsuden). Dies bedeutet

nicht, der Lehre der Meister zu widersprechen. Es bedeutet nur, dass auch ein Meister die Wahrheit

selbst nicht weiterzugeben vermag. Dies gilt nicht nur für Zen. Angefangen von den geistlichen

Übungen der Alten über die Kunst der Bildung der Seele bis hin zu den Künsten – immer ist die

Selbstaneignung das Kernstück, und dieses wird nur weitergegeben von Herz zu Herz, jenseits von

aller überlieferten Lehre. Der Sinn jeder ‚Lehre‘ ist nur: auf das, was jeder in sich selbst hat, ohne

es selbst schon zu wissen, hinzudeuten und es bewusst zu machen. Es gibt kein Geheimnis, das der

Meister dem Schüler ‚übergeben‘ könnte. Zu lehren ist leicht. Zu hören ist leicht. Schwer ist es

aber, dessen bewusst zu werden, was man in sich selbst hat, es zu finden und wirklich in Besitz zu

nehmen. Dies nennt man ins eigene Wesen blicken. Wesensschau (ken-sei, kensho). Widerfährt es

uns, haben wir Satori. Es ist das Große Erwachen aus dem Traum der Irrungen. Erwachen, ins

eigene Wesen blicken, Selbst-Wahr-Nehmung ist alles dasselbe.«

Zen-Master Ito Tenzaa Chuya

The Marvelous Cat

Translated by 寺本丈晴 TERAMOTO Takeharu és 桥本文雄 HASHIMOTO Fumio

PDF

Cf. PDF: The Subtle Art of a Cat

ONCE UPON A TIME there was a Master of combat called Shoken. His house was plagued by a big rat. It ran about even in broad daylight. One day Shoken shut the room door and gave the household cat an opportunity to catch the rat. But the rat flew at the cat’s face and gave it such a sharp bite that it ran off screeching. Evidently the creature couldn’t be got rid of so easily. So the master of the house collected together a number of cats that had won a fair reputation in the neighborhood and let them into the room. The rat hunched itself up in a corner. As soon as a cat approached it, it bit the cat and scared it off.

The rat looked so nasty that none of the cats dared to take it on a second time. That put Shoken into a perfect rage. He went after the rat himself, determined to kill it. But the wily beast escaped every blow and feint from the experienced Master; he just couldn’t wear it down. In his attempts to do so, he split doors, shojis, karakamis, and so forth. But the rat flashed through the air like lightning, jumped up at his face, and bit the Master. At last, running with sweat, he called out to his servants: "They say that six to seven cho from here there is the toughest and cleverest cat in the world. Bring it here!

The servant brought the cat. It didn’t look so very different from the other cats. It didn’t look particularly sharp or bright. So Shoken didn’t expect anything special from it. But he thought he would try it all the same, so he opened the door and let it into the room. The cat entered very softly and slowly as if it was expecting nothing out of the ordinary. But the rat recoiled and stayed motionless. So the cat approached it slowly and deliberately and carried it out in its mouth.

That evening the defeated cats met in Shoken’s house, respectfully accorded the old cat the place of honor, paid it homage and said humbly: "We are all supposed to be highly efficient. We have all practiced and sharpened our claws in order to defeat all kinds of rats, and even weasels and otters. We had never suspected that there could be a rat as strong as that one. But tell us, what art did you use to vanquish it so easily? Do not keep your art a secret. Let us into the mystery." The old cat laughed and said: "You young cats are indeed efficient. But you don’t know the right way to go about things. And so when something unexpected happens, you’re unsuccessful. But first tell me how you have practiced."

A black cat came out to the front and said: "I come from a line of celebrated rat catchers. I too decided to become one. I can jump over screens two meters high; I can force myself through a tiny hole that only rats can negotiate. From the time I was a kitten I have practiced all the acrobatic arts. Even when I wake up and I still haven’t quite come to, and I see a rat scampering across the balcony, I get it straightway. But that rat today was stronger and I suffered the most frightful defeat that I have ever experienced in my whole life. I have been put to shame."

Then the old cat said: "What you have practiced is only technique (shosa), sheer physical skill. But your spirit is preoccupied with the question: ’How am I going to win?’ And that problem is still consuming you when you reach the target. When the ancient Masters taught ’technique’, they did so in order to show their pupils a ’means of the way’ (michisuyi). Their technique was simple yet contained the highest truth. But posterity has been preoccupied with technique and technique alone. In that way much has been discovered according to the rule: if you do this or that, then this will happen. But what does happen? No more than dexterity-skill pure and simple. The traditional way has been abandoned; much ingenuity has been applied to an exhaustive pitting of technique against technique, until we have indeed reached the point of exhaustion. We can go no further. That always happens when people think of technique and success and put no more than ingenuity into play. Ingenuity-cleverness is however a function of the spirit, if it is not based on the Way and aims at perfect skill, then it falls victim to error and what has been achieved is lost. Think about this and practice from now on in the right spirit."

At that a big tabby-cat came forward and said: "In the art of fighting it is a matter of the spirit, and it must always be so. Therefore I have always practiced strength of spirit (ki wo neru). As far as I am concerned, my spirit always seems as hard as steel and free and charged with the presence of the Spirit that fills heaven and earth (Mencius). As soon as I can see an enemy, he is already vanquished; no sooner do I see him than he is thrall to that mighty Spirit and I have already won the battle in advance! I do so quite instinctively, as the situation demands. I move according the feel of my opponent; I take the rat from the right or the left as I wish and I anticipate my adversary’s every move. I never worry about technique as such. It happens of its own accord. If a rat runs across the balcony, I have only to stare at it for it to fall into my clutches. But the rat of which we are speaking comes without shape or form and goes without leaving any trace. What does that mean? I cannot say."

Then the old cat remarked: "What you have been concerned with is, of course, the effect of that great Power that fills heaven and earth. But what you have actually achieved is only a mental power and not that good power which serves the name of Good. The very fact that you are conscious of the power with which you intend to conquer prevents your victory. Your ego is in question. But what if your adversary’s ego is stronger than your own? When you try to overcome the enemy with the superior force of your own power, he pits his own power against yours. Do you imagine that you alone can be as strong and that all others must be weak? The real question is how to behave when there is something that in spite of all one’s willing one cannot defeat with the superior weight of one’s own power. What you experience as ’free and tempered’ and ’filling heaven and earth’ within you is not the great Power itself (ki no sho) but only its reflection in you. It is your own spirit, and therefore but a shadow of the great Spirit. It appears to be the great power, but in reality it something quite different. The spirit of which Mencius speaks is strong because it is permanently illumined by great understanding. But your spirit obtains its power only under certain conditions. Your power and that of which Mencius speaks have different origins. They are as different from one another as the eternal flow of a river, for instance the Yangtse Kiang is from a sudden downpour one night. But what is the spirit that one should rely on when face with an enemy who cannot be conquered with any mere restricted mental power (kisei)? That is the real question! There is a proverb that says: ’A rat in the trap will even bite the cat.’ The enemy is in the jaws of death he has no resources to depend on. He forgets his life: he forgets all need; he forgets himself; he is beyond victory and defeat. And thus his will tempered like steel. How could one conquer him with a spiritual power which one scribes to oneself alone?"

Then an aging gray cat came slowly forward and said: "Yes, it is indeed as you say. Mental power whatever its strength has a form (katachi) in itself. But whatever has form, however small it may be, can be grasped. Therefore I have for a long time trained my soul (kokoro, the power of the heart). I do not practice the power which overcomes others spiritually (sei), like the second cat. And I do not hit out around me (like the first cat). I reconcile myself with my opponent, get on to equal terms with him, and do not oppose him in any way. If the other is stronger than I am, then I will simply acknowledge that, and so to speak give into his will. My art is rather to gather the flying pebbles in a loose cloth. A rat tries to attack me may be as strong as you like, but it will find nothing to fly against, nothing to get to grips with. But today’s rat simply didn’t respond to my trick. It came and went as mysteriously as God Himself. I have never encountered one like it".

Then the old cat said: "What you call propitiation does not arise from being, from the Greatness of Nature. It is an artificial, botched-up reconciliation - a mere artifice. Your conscious intention is to elude the adversary’s spirit of attack. But because you are thinking about it, however fleetingly, he realizes what your plan is. If you try to conciliate him, with a spirit thus composed, then your spirit (in so far as it concentrates on the attack) will be confused, mixed up, and your sharpness of perception and action will be considerably reduced. Whatever you do with fully conscious intent restricts the original pulsation of the Greatness of Nature as it takes effect from the depths of Mystery: it upsets the flow of your spontaneous movement. How then are you to put a miraculous power into practice? Only when you think of nothing, and do nothing, and in your movement surrender yourself to the pulsation of Being (shizen no ka), will you have lost all tangible form, and be so that nothing on earth can act as a counter-form; then there is no enemy left to resist you."

"I do not believe that everything that you have practiced is pointless. Everything can be a means of the Way. Technique and Tao can be one and the same, and then the great Spirit, the "governing Spirit", is already incorporated in you and is revealed in the action of your body. The power of the great Spirit (ki) serves the human person (ishi). He who has free access to (ki) can encounter everything within infinite freedom and in the right way. If his spirit is reconciled, it will not shatter ever on gold or rock, and need exert no special power in battle. Only one thing is necessary: that no trace of egotism of I-consciousness comes into play, lest everything should be lost. If you think about all that, however fleetingly, then all will be artificial. It will not arise from Being, from the original pulsation the body of the Way (do-tai). Then the adversary will not submit to you but resist in his own behalf. What sort of a way or art is to be used? Only when you are in that disposition which is free of all conscious of self, when you act without acting, without intention and stratagem, in unison with the Greatness of Nature, are you on the right Way. Abandon all intent, practice purposelessness and let it happen simply out of Being. This way is unending, inexhaustible." And the old cat added something astounding: "You must not believe that what I have told you today is the highest of things. Not long ago a certain tom-cat was living in the next village to me. He slept the whole day long. No trace of anything resembling spiritual power was to be observed in him. He just lay there like a lump of wood. No one had ever seen him catch a rat . But wherever he was, there wasn’t a rat to be seen! And wherever he popped up or laid himself down, no rat ever appeared. One day I looked up and asked what that meant. He did not answer me. I asked him another three times. He was silent. But that doesn’t mean that he didn’t want to reply. Instead he clearly didn’t know what he should say. But that is how it is: "He who knows says nothing, and he who says it knows it not". The cat had forgotten about himself and everything roundabout him. He had become "nothing". He had reached the highest level of purposelessness. We can say that he had found the way of divine knighthood, which is to vanquish without killing. I am still a long way behind him".

Shoken heard all this as if in a dream, came by, greeted the old cat and said: "For a long time now I have been practicing the art of fighting, but I have not yet reached the end. I have absorbed your insights and I think that I have understood the true meaning of my way, but I ask you earnestly to tell me something more about your craft".

The old cat replied; "How is that possible? I am only an animal and the rat is my food. How should I know about human affairs. All I know is this: the meaning of the art of combat is not merely a matter of vanquishing one’s opponent. It is rather an art by which at a given time one enters into the great clarity of the primal light of death and life (seishi wo akiraki ni suru). In the midst of all his technical practice a true Samurai should always practice the spiritual acquisition of that clarity of mind. For that purpose however he must plumb before all else the teaching of the ground of being of life and death (shi no ri). But only he acquires great clarity of mind who is free from everything which could lead him off that way (hen kyoku). When Being and encounter with Being (shin ki) are left undisturbed, to themselves, free from the ego and from all things, then whenever it is appropriate it can declare it’s presence complete freedom. But if your heart even fleetingly attaches itself to something, then Being itself is attached and is turned into something arrested in itself . But if it becomes something arrested in itself, then there is something there that resists the I that is in itself . Then two entities face one another and fight one another for dominance."

"If that happens then the miraculous functions of being, even though used to all change, are restricted, the jaws of death gape close, and that clarity of perception proper to Being is lost. How then is it possible to meet the adversary in the right frame and peacefully contemplate "victory and defeat"? Even if you win, you win no more than blind victory that has nothing to do with the spirit of the true art of combat."

"Being free from all things does not of course mean an empty void. Being as such has no nature in itself. In and for myself it is beyond all form. It stores up nothing in itself. But if one grasps and remembers even fleetingly what it is and how fragile it is, the great Power will cling to it and it will contain the equilibrium of forces that flows from the Source. But if Being is even slightly subject to or imprisoned by something, it is no longer able to move freely and cannot pour forth in all its fullness. If the equilibrium that emanates from Being is disturbed, if its power is at all apparent it quickly overflows; but without power its balance is inadequate. Where it overflows, too much power breaks out and there is no holding it back. Where it is inadequate, the active spirit is weakened and wanting is never sufficient for the situation it is called on .

What I call freedom of things means only that if one does not lay up stores, one has nothing to rely on. Without secure provision there is no position to take up and nothing objective to have recourse to. There is neither an I nor an anti-I. When something comes along, one meets it as it were unawares, without any impact. In the I-Ching (the Book of Changes), it is written "Without thinking, without action, without movement; quite still. Only thus can one proclaim the nature and law of things from within, quite unconsciously, and at last become one with heaven and earth. Whoever practices and understands the art of combat in that sense is close to the truth of the Way".

When Shoken heard this, he asked: "What does that mean, that neither a subject nor an object, neither an nor an anti-I is there"?

The cat answered: "If and because an I is there, there is an enemy there. If we do not present ourselves as an I, then there is no opponent there. What we call opponent, adversary, enemy, is merely another name for what means opposition or counterpart. In so far as things maintain a form, they also presuppose a counter-form. But wherever something is present as a something, it has a specific form. If my being is not constituted as a specific form, then there is no counter-form there."

"When there is no counterpart, no opposition, there is nothing which can come forth to oppose me. But that means that neither an I nor an anti-I is there. If one wholly abandons self and thus becomes free, from the foundations upwards and from everything, then one will be in harmony with the world and one with all things in the great universal oneness. Even when the enemy’s form is extinguished one remains unconscious of it . That does not mean that one is wholly oblivious of it, but that one does not dwell on it, and the spirit continues free from all attachment and even in its actions responds simply and freely from the center of being. If the spirit is no longer by possessed by anything and is free from all obsession, then the world, just as it is wholly our world and one with us. That means that henceforth one apprehends it beyond good and evil, beyond sympathy or antipathy. One is no longer caught up in anything in the world. All oppositions which present themselves to us, profit and loss, good and evil, joy and suffering, have their origin us. Therefore in the whole spread of heaven and earth nothing is so worthy of discernment as our own being. "

"An ancient poet said: "A speck dust in one’s eye and even the three worlds are still too narrow". If nothing matters to us any longer and is no longer of consequence to us, then the smallest bed is too wide for us. " In other words, if a speck of dust enters our eye, the eye will not open; for we can see clearly only if there is nothing within, but now the dust has penetrated to obstruct the vision within. Similarly with being that shines forth as light and illumination, and is essentially free of everything that is "something". When however something does present itself, the very presentation destroys its essence. Another writer put it this way: "If one is surrounded by foes, by a hundred thousand enemies, one’s form is so to speak pulverized. But my being, my nature, is mine and remains my own, however strong my enemy may be . No adversary can penetrate my being my self". Confucius said: "You cannot steal the being of even a simple man". But if the spirit is confused, then being will turn against us."

"That is all that I can tell. Now return to yourselves and know yourselves. A master can only teach his pupil the lesson and try to justify it. But "I myself" have to realize the truth and take it as my own. That is called self-appropriation (jitoku). It is transferred from heart to heart (ishin denshin). It is a bestowal by extraordinary means, beyond instruction and erudition (kyogai betsuden) that does not mean that the Master’s teaching is to be contradicted. All it means is that even a Master cannot pass on the truth itself. That is not only true of Zen."

"From the spiritual exercises of the ancients on the art of forming the soul right up to the arts proper, self appropriation is always the essence of the matter, and it is always transmitted from heart to heart, apart from tradition, from all teachings which are handed down. The meaning of all "teaching" is only to show what everyone possesses in himself without already knowing it, and then to make him aware of it. There is no secret that the master can "hand over" to the pupil. Teaching is easy. Listening is easy. But it is difficult to become aware of what one has in one’s self, to mark it out and really to take possession of it. That is known as looking into one’s own being. It is self perception, the self perception of being (ken-sei, kensho). If that happens to us then we have Satori. It is the great awakening out of the dream of errors. Awakening, looking into one’s own being, perception of the self one really is - they are all one and the same thing".Takeharu Teramoto was an Admiral and Professor at the Naval Academy in Tokyo. His form of practice was sword fighting (Gyo). His own Master had been the last Master of a school of combat in which the story of five cats had been handed down from Master to Master since the beginning of the seventeenth century as a form of instruction, and had finally reached Teramoto through his own Master.

佚斎樗山 Issai Chozan (1659-1741): 「猫の妙術」 Neko no myōjutsu

The Mysterious Technique of the Cat

In: The Demon's Sermon on the Martial Arts: And Other Tales

by Issai Chozanshi

Translated by William Scott Wilson

Kodansha International, 2006

The tale “Neko no myōjutsu” written in 1727 by Niwa Jurozaemon Tadaaki (1659–1741), a samurai of the Sekiyado fief [The Sekiyado fief is located in the ancient province of Shimosa, now divided between Chiba and Ibaraki prefectures]... Little is known of this man, whose nom de plume was Issai Chozanshi, but he was clearly acquainted with swordsmanship, philosophy, and art; had made an extensive study of Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, and Shinto; and seems to have been familiar with the works of Musashi and the priest Takuan.

Issai Chozanshi (佚斎樗山子). Chozanshi was likely one of the literati, more interested in a quiet life of studying the arts and communing with like-minded friends than in being involved with politics or the great topics of the day. Surely the name he chose as his literary moniker gives us an insight into his personality. The 佚 of Issai can mean to “avoid” (as in society), to “take pleasure in” (as in studies), or to “play around” and “be content.” For the Chinese Confucian scholar Mencius, the Itsudo (佚道) was the Way of making people happy and at ease. Tellingly, too, the compound 佚遊 means to amuse yourself with your own pursuits. Thus, Issai is the artist who amuses himself and others. Chozanshi, on the other hand, may be taken as the “philosopher of Stinking Tree Mountain.” The cho (樗)—Ailanthus glandulosa—is a tree known for its twisted and unpleasant-smelling timber. In the Chuang Tzu, when a man complains that the cho in his yard is useless, ignored by carpenters and avoided by everyone, Chuang Tzu points out that this precise uselessness is why it has lived so long. He then asks his complaining neighbor, “Why don’t you plant it in the village of Nothing-at-All or in the field of Empty-of-Breadth? Knocking about, you could engage in Non-Action at its side; free and easy, you could sprawl out and sleep beneath it. It will not be cut down prematurely by axes great or small, and will be harmed by nothing. Even though it can’t be used, how will it ever be troubled or distressed?”

There was a swordsman by the name of Shoken.1 One day, a large rat turned up in his house. The rat would not leave, and took to roaming around the house, even in broad daylight. Eventually, Shoken managed to trap the rat in a room, so he could set his cat upon it. But as the cat entered the room, the rat advanced, hurled itself at the cat’s face, and sank its teeth into it. The cat let out a scream and ran away. Realizing he was up against more than he had bargained for, Shoken went around the neighborhood and borrowed a number of cats that had made names for themselves as the best of their kind. He chased them into the room where the rat was making its nest in the corner of the alcove, but when one of the cats approached, the rat once again pounced and sank its teeth into it. When the other cats saw this appalling situation, they all fled in fear.

Shoken was outraged and chased the rat about, trying to kill it with a wooden sword he carried at his side, but the rat would slip away and avoid being struck. Furthermore, although all the paper-covered sliding doors were smashed down and torn in the fracas, the rat would jump and escape into the center of the room, always moving with the speed of lightning. It seemed that sooner or later the rat was going to leap at Shoken’s face and give him a taste of its teeth. Shoken broke into a sweat and said to himself, “I’ve heard that not far from here, there is a cat that is first-rate and in fact unequalled. I’d better go borrow that one,” and thereupon sent a man off for it.

The cat was brought in and he took a look at it, but it did not appear to be particularly clever or even very active. Still, he thought, “First I’ll try putting it into the room anyway,” and so he opened the door just a little and put the cat inside. The rat cowered right where it was, and was unable to move. The cat walked over in a leisurely fashion and dragged the rat away as though it were nothing at all.

That night, all the other cats gathered at the house and, inviting the old cat to take the most honored seat, all genuflected before him and, with great respect, said, “We are all called first-rate cats. We have disciplined ourselves in our Way, and sharpen our claws to crush even weasels and otters, not to mention rats. Up to now, however, we have never encountered such a strong rat as this one. Yet you overcame him easily, perhaps by some personal technique. We humbly request that you impart your lordship’s mysterious technique to us, holding nothing back.”

The old cat laughed and said, “All you young cats work with considerable skill, but you haven’t heard about the method of the Correct Way. Thus you have met a situation contrary to your expectations and have come to grief. Nevertheless, I would first like to hear about how each of you have trained.”

An agile black cat stepped up from the midst of the group and said, “I was born into a house of mousers, and have exerted myself in that Way, leaping over seven-foot screens and squeezing myself through tiny holes, so that from the time I was a kitten there was no quick or nimble trick I could not do. Whether it was the strategy of pretending to be asleep or suddenly exploding in a blaze of energy, I never faltered, even with rats that ran along the rafters and beams. But today I have encountered a rat stronger than I could imagine, and have gotten the beating of a lifetime. This is something I never expected.”

The old cat said, “Ahh, your discipline is only a performance of skill. Thus, you still haven’t escaped from the mind that aims at something. The men of old taught performance in order to inform others of the Way, so such performances were simple and contained a profound principle within them. In these later times, performances of skill are considered specializations: various details are concocted, dexterity is inordinately refined, the ancients’ sayings are considered insufficient, and the practitioner uses his own wit and contrivances. In the end, it all comes down to a contest of performance skills; dexterity consumes itself, and for what? Those who practice refining the dexterity of men of little character, and those who specialize in wit and contrivances are all like this. Wit may be used by the mind, but it is not based in the Way. When one specializes solely in dexterity, he is at the edge of make-believe;2 and, contrary to what you might think, there are many instances of wit and contrivances becoming nothing but drawbacks. You should reflect on such matters in this way, and make great efforts.”

Next, a large brindled cat came forward and said, “To my way of thinking, we respect the ch’i3 of martial arts. Therefore, I have disciplined my ch’i over a long period of time. Now that ch’i is serene and exceedingly strong, and would seem to fill Heaven and Earth. I trample my opponent underfoot, by first defeating him and then advancing. Following the voice, responding to the echo, I control the rat and there is nothing I cannot answer to. I have no thoughts or intentions for using a performance of skill, and my performance flows out on its own. I can just stare at a rat running along the rafters and beams so that it falls off and is taken. Nevertheless, this strong rat has no form when it comes, and leaves no traces when it goes. What kind of thing is this?”

The old cat said, “Your training can only function by depending on the power of ch’i. You are still depending on yourself. This is not the highest good.4 If you are going out to defeat your opponent, he may also be coming out to defeat you. And what about when defeat turns into no defeat at all? You may disguise your intentions to crush your opponent, but your opponent may do the same. And what about when a disguise turns into no disguise at all? How can it be that only you will be strong and all your opponents weak? Thinking that your ch’i is serene, exceedingly strong, and filling Heaven and Earth, is all just considering its form. It resembles Mencius’s ‘vast and expansive’ ch’i,5 but in fact it is not. Mencius’s ch’i depends on complete clarity and so is strong and sturdy. Yours is strong and sturdy because it depends on power. Thus, their functions are not the same. They are as different as the eternal flow of the Yellow River and the force of an overnight flood. Moreover, when someone will not yield to the energy of your ch’i—what then? There are occasions when a cornered rat will bite a cat, contrary to expectations. Pressed with certain death, there is nothing for it to fall back on. It forgets about life, forgets about its desires, does not consider victory or loss as inevitable, and has no thoughts of preserving its own skin. Thus, its resolve is like iron. How could you defeat an opponent like this with the force of ch’i?”

Then a middle-aged gray cat advanced composedly, and said, “The ch’i of which you speak is fully active, but has a form. Things that have a form may be indistinct, but can be seen. I have disciplined my mind for a long time. I do not develop force, nor do I contend with things. I am in harmony with others, and run counter to nothing. When someone attempts to be tough with me, I meet him with harmony and so become his companion. My technique is like catching pebbles with a large curtain. Though you may speak of a cornered rat, there is nothing to fall back on to contend with me. Nevertheless, today’s rat could neither be overcome with force nor met with harmony; both coming and going, he was like a god. I’ve never seen anything like him up until now.”

The old cat said, “Your harmony is not natural harmony. You think, and so create harmony. Though you intend to avoid your opponent’s sharp spirit, you still retain a small bit of intention, so your opponent sees through your tactic. If you attempt to reach harmony by inserting your mind, your ch’i will be corrupted and you will be approaching negligence. When you think and then do something, you obstruct your natural perception. And if you obstruct natural perception, how can the mysterious function be given life from anywhere at all? Simply without thinking, without doing anything, move by following your natural perception and your movement will have no form.6 And when you have no form, there is nothing in Heaven and Earth that could be your opponent.

“That said, each and all of your disciplines are not without value. The meaning of the phrase ‘form and spirit are consistent,’7 is that the highest principle is contained within a performance of technique. Ch’i is what generates function throughout the body. When that ch’i is serene and everywhere, response to things will be boundless; and when you are in harmony, there will be no contending with strength. Though you are struck with metal and rock, you will not be crushed. Nevertheless, even the smallest thoughts will all become [conscious] intentions.8 This is not the spontaneity9 of the Way. Thus, when you face off with another, if your mind has not been subdued, the mentality of opposition will exist. What technique will you use then? No-Mind10 and responding naturally is the only answer.

“Still, the Way is not limited, and you should not think that what I say is the ultimate. Long ago there was a cat in my neighborhood; it slept all day and had no vitality at all. It was like a cat made out of wood.11 People never saw it catch rats, but wherever the cat was, there were no rats in the vicinity. And this was true even if it changed locations. I went over and asked why this was so, but it gave me no answer. Though I asked it four times, still four times it did not answer.12 It was not that it could not answer, but that it didn’t know what to say. This is, as you know, an example of ‘Those who know don’t speak; those who speak don’t know.’13 That cat had even forgotten that it had forgotten itself, and had returned to a state of ‘Nothingness.’14 The very spirit of the martial, it killed nothing.15 I am far and away unable even to approach that cat.”

Shoken listened to this as though in a dream. He went over to the old cat, folded his hands over his chest, bowed his head with deep respect, and said, “I have disciplined myself in the art of swordsmanship for a long time, but still have not reached the summit of that Way. Tonight, listening to each of these theories, I have attained the highest degree of my path. May I request that you point out its very deepest mysteries?”

The cat said, “No, I’m just an animal. Rats are my meals. What would I have to do with the actions of human beings? Still, there is something I heard in secret. That is that the art of swordsmanship is not exclusively in making efforts to defeat others. It is the art of dealing with the Great Transformation, and being clear on the matter of life and death. A man who would be a samurai should always maintain this kind of mentality, and should discipline himself in that art. For this reason, you should first of all penetrate the matter of life and death; make no particular adaptations to the mind; have no doubts and no vacillation; do not use your own wit, contrivances, or prejudices; harmonize mind and ch’i; rely on nothing; and be as serene as a deep pool. If you are always like this, you will be completely free to respond to any change.

“But when the smallest thing enters your mind, form will appear. And when there is form, there will be an opponent and there will be yourself. Facing each other, there will be conflict; and in a situation like this, the mysterious functions of change and metamorphosis will not occur with freedom. First, your mind will fall into thoughts of death and you will lose all clarity of spirit. How then will you stand readily and with resolve for a fight? Even if you should win, it would be what is called a blind victory, and this is not the true object of the art of swordsmanship.

“‘Nothingness’ is not what you would call empty-headedness. It is the foundation of the mind and has no form. You should never be taken by phenomena.16 Once you are the least bit taken by something, your ch’i will be drawn to it. And once your ch’i is even slightly drawn to something, it will be incapable of adaptability or openness. It will go beyond what you are facing, but not reach the place you are not facing. When it goes too far, your energy will overflow and be uncontrollable; when it can’t go far enough, it will be clogged up and useless. In neither case will it be able to respond to change. What I am calling ‘Not One Thing’ means neither being taken by nor drawn toward phenomena, that there is neither opponent nor myself,17 and that there is nothing more than following phenomena as they come, responding to them, and leaving no traces.

“The I Ching says, ‘No thoughts, no actions; being serene in non-movement; perceiving and thus becoming intimate with the particulars of Heaven and Earth.’18 If a man who studies the art of swordsmanship understands this principle, he will be close to the Way.”

Shoken asked, “What does ‘there is neither my opponent nor myself’ mean?”

The cat replied, “Because I exist, my opponent exists. If I do not exist, neither will my opponent. ‘Opponent’ is the name we give primarily to someone who stands against us. Yin and yang, water and fire, are of this sort. For the most part, something that has form will surely have something in opposition to it. However, if there is no form to my mind, there will be nothing opposing it. When there is nothing in opposition, there is no contention. This is what is meant by ‘there is neither an opponent nor myself.’ When phenomena and myself have both been forgotten, and I am deeply serene and tranquil, then I am in harmony and at one with the world. Though I crush the form of my opponent, I myself will not know it. This is not ‘not knowing,’ but rather there will be no thought here whatsoever, and I will only move in accordance with my perceptions. When the mind is deeply serene and tranquil, the world is my world. There is no right and wrong, liking and disliking, or being taken by phenomena. Everything within the boundaries of pain and pleasure or gain and loss are created by my mind. And though we say that Heaven and Earth are vast, there is nothing to seek outside of our own minds.

An ancient worthy said:19

When there is dust in the eye, the three worlds are shut out;

When the mind and heart are without a care, one’s whole life is at ease.“When even a little bit of dust or sand gets into your eye, your eye is unable to open. And it’s just like this when you put something into a bright and clear place where originally there was nothing. This is a metaphor for the mind.

“Another saying has it, ‘Surrounded by tens of thousands of the enemy, your form may be pummeled into small pieces, but this mind is still yours. Even the greatest opponent can do nothing about that.’ Confucius said, ‘Even an ordinary man cannot be robbed of his will.’20 But when you are confused, that very mind will become an assistant to your opponent.

“I’ll stop talking here. You should now simply engage in self-reflection, and seek within yourself. A teacher can only transmit a technique or enlighten you to principle, but receiving the truth of the matter is something within yourself. This is called ‘grasping it on one’s own.’ It is also called ‘transmission from mind to mind,’21 and again, ‘a special transmission beyond the scriptures.’ This is not turning one’s back on the scriptures. It is saying that a teacher cannot transmit this to you. This is not only in the study of Zen. From the ‘Law of the Mind’ of the Confucian sages down to the arts,22 ‘grasping it on one’s own’ is always a matter of ‘transmission from mind to mind.’ It is a ‘special transmission’ beyond the scriptures. The scriptures are within yourself; [those that are written down] only point out what you have not been able to see on your own.23 This is not something conferred on you by a teacher. It is easy to teach and also easy to listen to the teachings. It is only difficult to see that they are something within you, and to make them your own. This is called ‘seeing into one’s own nature.’24 Enlightenment is the perception that you have been having a wild dream. An ‘awakening’ is the same. There is no difference between them.”

1 Shoken (勝軒): Sho means “victory” or “victorious,” while ken usually means “eaves.” Nevertheless, it can also mean “dancing” or “laughter”—both good Taoist subjects—and “being good at” or “making a specialty of,” which seems most likely here. Ken is also a homonym with “sword.”

2 From Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching, 57: “When man makes a great deal of skill and cunning, off-beat ways arise more and more.” Chozan’s word “make-believe” also can mean “falsehood.” Both meanings—one directed inwardly, the other outwardly—are appropriate.

3 Ch’i: The vitality that is the very foundation of the body.

4 Tao Te Ching, 8: “The highest good is like water; it benefits the Ten Thousand Things, but does not contend with them.”

5 Mencius: “Again he asked, ‘What is this broad and expansive ch’i?’ He said, ‘It’s difficult to say. It is extremely great and strong, and because of this it nurtures and does not harm. Thus it fills the space between Heaven and Earth.’”

6 I Ching, The Commentaries: “Change does not think, it does not act [with intent]. It is serene and does not move. It perceives and thus penetrates everything under Heaven.” Note that “change” (易) can also be read as “easy.”

7 Lit., “The utensil and the Way are consistent.” The meaning is that the manifest is the utensil, and the spirit within is the Way. I Ching, The Commentaries: “With form, the ascendant is called the Way, while the descendant is called the utensil.”

8 Sakui (作意), intention, is a homonym of sakui (作為), artificiality.

9 Shizen (自然): Lit., “of-itself-so,” means both the natural world (which includes ourselves) and its internal laws. See discussion of tzu jan in the introduction.

10 Mushin (無心): The Zen Buddhist ideal—a mind without calculations, prejudices, or pre-valuing. Lit., “no mind.” It is the mind empty of all artifice, completely open to whatever enters it. It reflects the manifest world like a mirror, without the distortion of ideas of right and wrong, gain and loss, or attraction and repulsion. It is the enlightened mind.

11 This refers to the story in the Chuang Tzu of a man who trained gamecocks. He declared that any outward manifestation of energy, ferocity, or reaction to things about them indicated that the cocks were not yet trained to the highest degree. It was only when “you look at them and they resemble cocks made of wood,” that their discipline and training are complete.

12 Chuang Tzu: Nieh Ch’ueh was trying to question Wang Ni: “Four times he asked him, and four times he simply said, ‘I don’t know.’”

13 Tao Te Ching, 56: “The one who knows does not speak; the one who speaks does not know.”

14 Tao Te Ching, 14: “Continuous and consistent, it cannot be given a name. It returns again to Nothingness.” This mubutsu (無物), traditionally translated as “Nothingness” in Taoist texts, is the great source of everything in the universe. Chozan, however, seems to mix its meaning with the Zen Buddhist Mu Ichi Motsu (無一物), meaning that not one thing exists on its own, that everything is contingent on other things—Nothingness with a slightly different twist. Thus we should not, and indeed cannot, rely on anything. Rather, we should always return to the boundless source of Nothingness.

15 I Ching, The Commentaries: “The wise and sagacious men of ancient times had the very spirit of the martial and did not kill.”

16 In the Fudochishinmyoroku, the Zen priest Takuan (1573–1645) emphasized that the mind of a swordsman should not be taken (stopped or moved) by anything at all. If it were to be taken, its freeflow would be clogged up and the unfettered movement of both body and mind would be arrested.

17 In the Taiaki, also by Takuan, we read: “Presumably, as a martial artist, I do not fight for gain or loss, am not concerned with strength or weakness, and neither advance a step nor retreat a step. The enemy does not see me. I do not see the enemy. Penetrating to a place where Heaven and Earth have not yet divided, where yin and yang have not yet arrived, I quickly and necessarily gain effect.”

18 See note 7.

19 Referring to a poem by the Zen priest Muso Kokushi (1275–1351). The full verse runs:

How many times have the green mountains turned to yellow

The vigorous confusion of this world never ends.

A speck of dust gets in your eye and the Three Worlds are closed up.

But if there is nothing in your mind, all about you is broad and wide.20 Analects, 5,26: “A great army can be robbed of its general, but even a common man cannot be robbed of his will.”

21 Ishin denshin (以心伝心): A Zen Buddhist phrase meaning that the transmission of the enlightened mind does not rely upon words or texts. In The Bloodstream Sermon, Bodhidharma states, “In the arising of the Three Worlds, they all return to the One Mind. Both Buddhas in the past and Buddhas in the future transmit mind with the mind. They do not stand on words.”

22 The martial arts, etc.

23 In The Book of Five Rings, the great swordsman Miyamoto Musashi states, “In this Way especially, if you misperceive it or become lost just a little, you will fall into distortion. You will not reach the essence of the martial arts by merely looking at this book. . . . Rather, you should consider these principles as though they were discovered from your own mind, and continually make great efforts to make them a physical part of yourself.”

24 Kensho: Lit., “seeing one’s nature.” At its deepest, this is making the discovery on one’s own that the Buddha nature is within one’s own mind. In Bodhidharma’s Sermon on Awakening to One’s Nature, he states, “Pointing directly at man’s mind; see your own nature and become a Buddha. This is a special transmission beyond the scriptures, not standing on words or letters.”

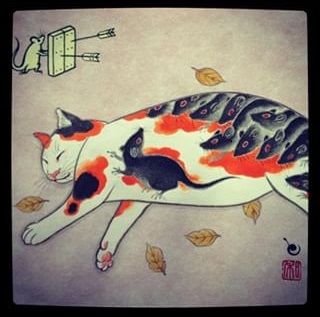

by Kwong Kuen Shan, 2004

Kwong Kuen Shan was born and brought up in Hong Kong where she studied both English and Classical Chinese. She later studied traditional Chinese painting, and developed her own style from that basis. The Philosopher Cat and her first book The Cat and the Tao are two of the results. She lived and worked in London for many years, and now lives near Abergavenny, a small market town in the Welsh borders.

The Mysterious Technique of the Cat (Manga)

in: Wilson, Sean Michael. The demon’s sermon on the martial arts: a graphic novel / from the book by Issai Chozanshi; based on the translation by William Scott Wilson; adapted by Sean Michael Wilson; illustrated by Michiru Morikawa.

Shambala, Boston & London, 2013

Illustration by 初見良昭 Hatsumi Masaaki (1931-)

Story – ‘Neko no myōjutsu' (Mysterious Technique of the Cat)

Posted by da2elni4na [Daniel Nishina]

May 4, 2010

http://da2el.wordpress.com/2010/05/04/story-neko-no-myojutsu-mysterious-technique-of-the-cat/

[I encountered this story recently and looked around, finding some varying versions of the Japanese and translations. My "tweak" translation below for the most part took out the inclusion of other translators' elaborations. Maybe my mind is, more than before, in a place to grasp all these Zen things I'm running into lately, so the elaborations seem unnecessary.]

Neko no Myōjutsu written by Issai Chozan in 1727

There was once a swordsman called Shōken. In Shōken's house, there was a large rat. The rat boldly ran around in the house in plain day, so Shōken attempted to catch it by closing off the room it was in and sending in his cat. Unfortunately, the rat ran straight at the cat, jumping on its head and biting it. The cat cried out and ran away.

Shōken had no choice but to assemble some local cats that seemed to be plenty strong, and send them into the room through a small opening. The rat was crouching in a corner, and jumped on and bit each cat that came near. Its fury was so great that the cats all cowered from the rat, making no further attempts to catch it. Seeing this, Shōken grew angry and grabbed his own wooden sword, attempting to strike down the rat himself. However, he not only swung and missed the rat every time, he had ruined his own walls and doors by the end.

Dripping sweat, he yelled out for his servant. “I heard of an amazing old cat living 6 or 7 neighborhoods over. Go and borrow it.”