A Terebess-gyűjtemény

From

the Terebess Collection

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

Sanghaji

art deco bútor/Shanghai-style Art Deco furniture

Lásd még: Sanghaji art deco plakátok

This Shanghai style writing desk is a practical design as many foreigners who lived in Shanghai were in need of larger desks. The wood is in wonderful condition but the top has a few marks from use.

------------------

Old

Shanghai furniture

can be roughly broken down into three categories, which correspond to the stages

of the city's development as well as to the style of buildings in which the

majority of the population resided. These started with the shikumen longtang,

which dominated from the mid Nineteenth Century up until about 1920, through

the yangfang longtang, or foreign-style alley houses, of the 1920s and early

'30s, and ending with the high-rise apartments of the mid '30s up to 1949. Of

course, these periods and styles overlapped significantly, and the furniture

and housing of earlier periods continued to be used and manufactured throughout

the later periods, but the standard division holds.

The shikumen longtang, or stone-gated alley houses, are an architectural form found only in Shanghai; only a few years ago, they still housed a majority of the city's residents, and they remain a Shanghai trademark, although they're rapidly disappearing. The furniture of the shikumen is the most "Chinese" of Shanghai's furniture. While general structure of shikumen furniture varies, with about half following Chinese lines and half more Western, their detailed decorations are invariably Chinese. The most common example of shikumen furniture is the rectangular stool, similar in shape and design to traditional Chinese tables and alters, but smaller, more practical, and more portable. Decorations between the legs follow traditional patterns. Rectangular stools were once ubiquitous in Shanghai, but are becoming ever less so. Also common are small, wooden chairs with square backs reminiscent of traditional Chinese chairs, but with rounded edges and beveled seats more Western in style. Vertically centered in the backrest is a column of detailed carvings depicting animals, birds, flowers, hearts, and other designs based in Chinese folk art. Other types of shikumen furniture, such as beds, tables, and cabinets, are similarly distinguished by detailed carvings drawing from the folk tradition. Beds throughout all three periods used woven matting, covered with cotton pads, which is typical of Southern China, contrasting with the heated brick kang typical in the North. With the advent of electricity, most shikumen houses were illuminated by a bulb hanging from the ceiling and covered by a white, round, flower-shaped glass shade. These shades are easily found at the Fuyou Lu and Dongtai Lu antique markets and should cost Y20.

Shanghai entered its period of modernization in the 1920s. J.B. Powell, who arrived in Shanghai in 1917, recalled in his memoirs how the city was transformed in the early 1920s by widespread plumbing, sewage, and other infrastructure essentials. Foreign-style lane townhouses -- xin shi li nong -- emerged in this period, merging the lane neighborhood and garden-and-courtyard structure of the shikumen with modern amenities. Two floors taller, with metal rather than wood fittings, and with indoor restrooms, these were the homes of middle class Chinese and the less-wealthy foreigners. The furniture of these townhouses was predominantly European classical. These subtle yet ornate pieces would have been perfectly at home in an English sitting room or French parlor of the same era. While frilly, flowery, French designs prevailed, Chinese elements could still be found in the smaller details, such as the crescent-shaped pull handles on the drawers.

Many international trends, including in the areas of art and design, tended to converge in Shanghai. The late 1930s and the 1940s were Deco decades for the city, as theaters, hotels, and apartment buildings, dominated by the inspired designs of Laszlo E. Hudec, altered Shanghai's face. Single family flats, in Art Deco buildings between four and twenty stories, provided an alternative to the multifamily lane dwellings. Paralleling the rise of the apartment buildings emerged a strain of Art Deco furniture, but like previous styles it came with uniquely Shanghainese characteristics. The majority of Shanghai's Art Deco furniture continued to use the general forms of the earlier styles, but with Deco flourishes taking the place of Chinese or classical details. My Yuyuan Lu stool, for example, is derived from a simple round, four-legged stool that is almost as much a Shanghai staple as the square stool mentioned earlier. Later incarnations added Chinese-style carvings as decoration under the seat and between the legs; examples of these are found in the site of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party. The Deco version merely curved the legs and the supports and added Art Deco "teeth" next to the legs.

Interestingly, the standard Chinese square table remained the norm for dining in Shanghai. Cramped living conditions precluded the possibility of a separate dining room for all but the most wealthy, so the longer, rectangular Western dining table never caught on. Versions of the multi-purpose square table, however, can be found in designs featuring the full range of Shanghai furnishing history.

After 1949, the

furniture industry like much else shifted focus to function over form. Shanghai

families, ever thrifty, continued to use the fancier furniture of an earlier

era, and only now with increased prosperity are they looking for replacements.

But the Shanghainese inclination to inundate their homes with cookie-cutter

Ikea imitations provides the opportunity to grace you home with a waft of the

mystery and history of Old Shanghai.

Source:

http://www.chinanow.com/english/shanghai/city/features/furnitureprint.html

---------------------------

Shanghai Modern:

Reflections on Urban Culture in China in the 1930s

by Leo Ou-fan

Lee

By 1930, Shanghai had become a bustling cosmopolitan metropolis, the fifth largest city in the world, and China’s largest harbor and treaty-port—a city that was already an international legend ("the Paris of Asia") and a world of splendored modernity set apart from the still tradition-bound countryside that was China. Much has been written about Shanghai in Western languages, and the corpus of "popular literature" that contributed to its legendary image bequeaths a dubious legacy. For aside from perpetuating the city’s glamour and mystery, it also succeeded in turning the name of the city into a debased verb in the English vocabulary: To "shanghai" is to "render insensible, as by drugs [read opium], and ship on a vessel wanting hands" or to "bring about the performance of an action by deception or force," according to Webster’s Living Dictionary. At the same time, the negative side of this popular portrait has been in a sense confirmed by Chinese leftist writers and latter-day communist scholars who likewise saw the city as a bastion of evil, of wanton debauchery and rampant imperialism marked by foreign extraterritoriality—a city of shame for all native patriots. It would not be too hard to transform this narrative into another discourse of Western imperialism and colonialism by focusing on the inhuman exploitation of the urban underclasses by the rich and powerful, both native and foreign.

Although I am naturally drawn to the "political correctness" of such a line of interpretation, I am somewhat suspicious of its totalizing intent. Mao Dun, the avowed leftist writer and an early member of the Chinese Communist Party, inscribes a "contradictory" message even on the very first page of his first novel, Midnight [Ziye], subtitled, A Romance of China, 1930. Whereas Shanghai under foreign capitalism has a monstrous appearance, the hustle and bustle of the harbor — as I think his rather purple prose seeks to convey — also exudes a boundless energy, as summed up by three words on a neon sign: light, heat, power! These three words, together with the word neon, were written originally in English in the Chinese text of Midnight, which obviously connotes another kind of "historical truth," the arrival of Western modernity whose consuming power soon frightens the protagonist’s father, a member of traditional Chinese gentry from the country, to death. In the first two chapters of the novel, in fact, Mao Dun gives prominent display of a large number of material emblems of this advancing modernity: cars ("three 1930-model Citroens"), electric lights and fans, radios, "foreign-style" mansions (yang-fang), sofas, guns (a Browning), cigars, perfume, high-heeled shoes, beauty parlors (in English), jai alai courts, "Grafton gauze," flannel suits, 1930 Parisian summer dresses, Japanese and Swedish matches, silver ashtrays, beer and soda bottles, as well as all forms of entertainment—dancing (fox-trot and tango), "roulette, bordellos, greyhound racing, romantic Turkish baths, dancing girls, film stars." Such modern conveniences and commodities of comfort and consumption were not fantasy items from a writer’s imagination; on the contrary, they were part of a new reality which Mao Dun wanted to portray and understand by inscribing it onto his fictional landscape. They are, in short, emblems of China’s passage to modernity to which Mao Dun and other urban writers of his generation reacted with a great deal of ambivalence and anxiety. After all, the English word "modern" (and the French "moderne") received its first Chinese transliteration in Shanghai itself: In popular parlance, the Chinese word modeng has the meaning of being "novel and/or fashionable," according to the authoritative Chinese dictionary, Cihai. Thus in the Chinese popular imagination, Shanghai and "modern" are natural equivalents. So the beginning point of my inquiry will have to be: What makes Shanghai modern? What made for its modern qualities in a matrix of meaning constructed by both Western and Chinese cultures?

Politically, for a century (from 1843 to 1943) Shanghai was a treaty-port of divided territories. The Chinese sections in the southern part of the city (a walled city) and in the far north (Chapei district) were cut off by the foreign concessions—the International Settlement (British and American) and the adjacent French Concession — which did not come to an end until 1943 during the Second World War, when the allied nations formally ended the concession system by agreement with China. In these "extraterritorial" zones, Chinese and foreigners lived "in mixed company" (huayang zachu) but led essentially separate lives. The two worlds were also bound together by bridges, tram and trolley routes, and other public streets and roads built by the Western powers that extended beyond the concession boundaries. The buildings in the concessions clearly marked the Western hegemonic presence: banks, hotels, churches, cinemas, coffeehouses, restaurants, deluxe apartments, and a racecourse. They served as public markers in a geographical sense, but they were also the concrete manifestations of Western material civilization in which were embedded the checkered history of almost a century of Sino-Western contact. As a result of Western presence, many of the modern facilities of Shanghai’s urban life were introduced to the concessions starting in the mid-nineteenth century: These included banks (first introduced in 1848), Western-style streets (1856), gaslight (1865), electricity (1882), telephones (1881), running water (1884), automobiles (1901), and streetcars (1908). Thus by the beginning of the twentieth century the Shanghai concessions already had the "infrastructure" of a modern city even by Western standards. By the 1930s, Shanghai was on a par with the largest cities of the world.

What made Shanghai into a cosmopolitan metropolis in cultural terms is difficult to define, for it has to do with both "substance" and "appearance" — with a whole fabric of life and style that serves to define its "modern" quality. While obviously determined by economic forces, urban culture is itself the result of a process of both production and consumption. In Shanghai’s case, the process involves the growth of both socioeconomic institutions and new forms of cultural activity and expression made possible by the appearance of new public structures and spaces for urban cultural production and consumption. Aspects of the former have been studied by many scholars, but the latter remains to be fully explored. I believe that a cultural map of Shanghai must be drawn on the basis of these new public structures and spaces, together with their implications for the everyday lives of Shanghai residents, both foreign and Chinese. In this essay, I would like first to give a somewhat descriptive narrative so that I can map out what I consider to be significant public structures and places of leisure and entertainment. This will serve as the "material" background for further interpretations of Shanghai’s urban culture and of Chinese modernity.

Urban Space and Cultural Consumption

Architecture and Urban Space "There is no city in the world today with such a variety of architectural offerings, buildings which stand out in welcome contrast to their modern counterparts." This statement implies that Shanghai itself offered a contrast of old and new, Chinese and Western. However, it does not mean that the Chinese occupied only the old sections of the city and the Westerners only the modern. The notorious regulation that barred Chinese and dogs from Western parks was finally abolished in 1928, and the parks were opened to all residents. In fact, the population in the foreign concessions was largely Chinese: more than 1,492,896 in 1933 in a total city population of 3,133,782, of which only about 70,000 were foreigners. But the contrast nevertheless existed in their rituals of life and leisure, which were governed by the ways in which they organized their daily lives. For the Chinese, the foreign concessions represented not so much "forbidden zones" as the "other" world — an "exotic" world of glitter and vice dominated by Western capitalism, as summed up in the familiar phrase shili yangchang (literally, "ten-mile-long foreign zone"), which likewise had entered into the modern Chinese vocabulary.

The central place of the shili yangchang is the Bund, a strip of embankment facing the Whampoo River at the entrance of the harbor. It is not only the entrance point from the sea but also, without doubt, the window of British colonial power. The harbor skyline was dotted with edifices of largely British colonial institutions, prominent among which were the British Consulate, the Shanghai Club (featuring "the longest bar in the world"), the Sassoon House (with its Cathay Hotel), the Customs House, and the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank. The imposing pomposity of the these buildings represent perfectly British colonial power. Most of these British edifices on the Bund were built or rebuilt in the neoclassical style prevalent in England beginning in the late-nineteenth century, which replaced the earlier Victorian Gothic and "free style" arts and crafts building and was essentially the same style that the British imposed on its colonial capitals in India and South Africa. As the dominant style in England’s own administrative buildings, neoclassical style consciously affirms its ties to imperial Rome and ancient Greece. As Thomas Metcalf has stated, "the use of classical forms to express the spirit of empire was, for the late-Victorian Englishman, at once obvious and appropriate, for classical style, with their reminders of Greece and Rome, were the architectural medium through which Europeans always apprehended Empire." However, by the 1930s, the era of Victorian glory was over: England was no longer the unchallenged master of world commerce. A new power, the United States of America, began its imperial expansion into the Pacific region, following its conquest of the Philippines. The merger of the British and U.S. concessions into one International Settlement had occurred earlier, when U.S. power had been dwarfed by the might of British imperialism. But by the 1930s, Shanghai’s International Settlement was the site of competing architectural styles: Whereas British neoclassical buildings still dominated the skyline on the Bund, new constructions in a more modern style that exemplified the new U.S. industrial power had also appeared.

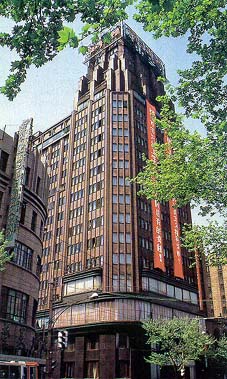

Since the late 1920s, some thirty multistoried buildings taller than the colonial edifices on the Bund had already begun to emerge as a result of the invention of modern construction materials and techniques in America. These were mainly bank buildings, hotels, apartment houses, and department stores — the tallest being the twenty-four-story Park Hotel designed by the famous Czech-Hungarian architect Ladislaus Hudec, who was associated with the American architectural firm of R. A. Curry before he opened his own offices in 1925. Hudec’s "innovative and elegant style added a real flair to Shanghai’s architecture," as evidenced by the many buildings he designed: in addition to the Park Hotel, the twenty-two-story building of the Joint Savings Society, the Moore Memorial Church, several hospitals and public buildings, and three movie theaters, including the renovated Grand Theater. The exteriors and interiors of some of these modern buildings—the Park Hotel, the Cathay Hotel/Sassoon House, and new cinemas such as the Grand Theater, the Paramount Ballroom and Theater, the Majestic Theater, and many apartment houses — were done in the prevalent Art Deco style. According to Tess Johnston, "Shanghai has the largest array of Art Deco edifices of any city in the world." The combination of the high-rise skyscraper and the Art Deco interior design style thus inscribed another new architectural imprint — that of New York City, with which Shanghai can be compared.

New York remained in many ways the prototypical metropolis for both the skyscraper skyline and the Art Deco style. Its tallest buildings — those of Rockefeller Center, the Chrysler Building, and, above all, the Empire State Building — were all constructed only a few years before Shanghai’s new high-rise buildings. Although dwarfed in height, the Shanghai skyscrapers bear a visible resemblance to those in New York. This U.S. connection was made possible by the physical presence of U.S. architects and firms. Another likely source of American input is Hollywood movies, especially musicals and comedies, in which silhouettes of skyscrapers and Art Deco interiors almost became hallmarks of stage design. The Art Deco style may be said to be the characteristic architectural style of the interwar period in Europe and America; it was an architecture of "ornament, geometry, energy, retrospection, optimism, color, texture, light and at times even symbolism." When transplanted into the American cities — New York in particular — Art Deco had become an essential part of "an architecture of soaring skyscrapers — the cathedrals of the modern age." The marriage between the two synthesizes a peculiar aesthetic exuberance that was associated with urban modernity and which embodied the spirit of "something new and different, something exciting and unorthodox, something characterized by a sense of joie de vivre that manifested itself in terms of color, height, decoration and sometimes all three."

When "translated" into Shanghai’s Western culture, the lavish ornamentalism of the Art Deco style becomes, in one sense, a new "mediation" between the neoclassicism of British imperial power, with its manifest stylistic ties to the (Roman) past, and the ebullient new spirit of American capitalism. In addition to—or increasingly in place of—colonial power, it signifies money and wealth. At the same time, the Art Deco artifice also conveys a "simulacrum" of the new urban lifestyle, a modeng fantasy of men and women living in a glittering world of fashionable clothes and fancy furniture. It is, for Chinese eyes, alluring and exotic precisely because it is so unreal. The American magazine Vanity Fair, perhaps the best representation of this image in print, was available in Shanghai’s Western bookstores and became a favorite reading matter among Shanghai’s modernist writers. One need only glance through a few issues of the magazine to discover how some of its visual styles (Art Deco, in particular) crept into the cover designs of the Chinese magazines in Shanghai, even reworked in the design of the Chinese characters themselves.

Whereas this gilded

decadent style may be a fitting representation of the "Jazz Age" of

the "Roaring Twenties" in urban America, it remained something of

a mirage for Chinese readers and filmgoers—a world of fantasy that cast a mixed

spell of wonder and oppression. The Chinese term for skyscrapers is motian dalou

—literally, the "magical big buildings that reach the skies." As a

visible sign of the rise of industrial capitalism, these skyscrapers could also

be regarded as the most intrusive addition to the Shanghai landscape, as they

not only tower over the regular residential buildings in the old section of

the city (mostly two- or three-story-high constructions) but offer a sharp contrast

to the general principles of Chinese architecture in which height was never

a crucial factor, especially in the case of houses for everyday living. No wonder

that it elicited responses of heightened emotion: In cartoons, sketches, and

films, the skyscraper is portrayed as showcasing socioeconomic inequality —

the high and the low, the rich and the poor. A cartoon of the period, titled

"Heaven and Hell," shows a skyscraper towering over the clouds, on

top of which are two figures apparently looking down on a beggarlike figure

seated next to a small thatched house. A book of aphorisms about Shanghai has

the following comment: "The neurotic thinks that in fifty years Shanghai

will sink beneath the horizon under the weight of these big, tall foreign buildings."

These reactions offered a sharp contrast to the general pride and euphoria accorded

to New Yorkers, as described in Ann Douglas’s recent book.

To the average Chinese, most of these high-rise buildings are, both literally and figuratively, beyond their reach. The big hotels largely catered to the rich and famous, and mostly foreigners. A Chinese guidebook of the time stated: "These places have no deep relationship to us Chinese . . . and besides, the upper-class atmosphere in these Western hotels is very solemn; every move and gesture seems completely regulated. So if you don’t know Western etiquette, even if you have enough money to make a fool of yourself it’s not worthwhile." This comment reveals at once a clear sense of alienation as it marks an implied boundary, drawn on class lines, between the urban spaces possessed by Westerners and Chinese. The upper-class solemnity of the Western hotels and dwellings may be disconcerting, but it does not prevent the author of the guidebook, Wang Dingjiu, from talking ecstatically about the modern cinemas and dance halls and, in its section on "buying," about shopping for new clothes, foreign shoes, European and American cosmetics, and expensive furs in the newly constructed department stores. It seems as if he were greeting a rising popular demand for consumer goods by advising his readers on how to reap the maximum benefit and derive the greatest pleasure.

Leo Ou-fan Lee teaches Chinese literature at Harvard University. His publications include Voices from the Iron House: A Study of Lu Xun (1987) and Shanghai Modern (1999).

Laszlo

Hudec (1893-1958)

Ladislaus Edward Hudec

http://www.china.org.cn/english/2001/Sep/19723.htm

The architect Laszlo Hudec: a Hungarian who worked primarily in Shanghai, China from 1918 to 1945. Hudec is one of the most prolific and important architects of the pre-revolution period in China.

Laszlo Hudec was born in 1893 in northern Hungary. As a young man, Laszlo's father, a builder, encouraged him to work in all aspects of the trade. From 1911 to 1914 Hudec studied architecture at the Budapest University. After the completion of his degree, he joined the Austro-Hungarian army, only to be caught by the Russians in 1916 and sent to prison camp in Siberia. Two years later, in 1918, Hudec was on a prisoner of war train headed for the interior of Russia from Habarowsk, a prison camp close to the Chinese border. Hudec jumped train and made his way into China eventually arriving in Shanghai.

In Shanghai, Hudec

joined the American architectural firm, R.A. Curry. By 1925, he had established

his own office and was one of the leading architects in the city. By 1941, he

had built at least 37 buildings as well as numerous private residences.

He died in California in 1958.

University of

Victoria Special Collections

The Hudec

Collection:

The Libraries'

Special Collections has recently received as a gift the papers of Laszlo Hudec.

The archive consists of approximately 550 sketches, conceptual drawings, presentation

drawings, working drawings, technical drawings (inclusive of blueprints), travel

sketches and photographs. The drawings include exterior and interior renderings

of plans and designs for projects produced in both Europe and in China. This

architectural collection consists of works by Hudec and two anonymous authors.

The work of Hudec was transcribed in English, German and Chinese. The work of

the unknown authors is transcribed in Hungarian and German. There are also 2

boxes of textual records including notes, notebooks, photo albums, documents,

letters, memos, scrapbooks, photos, legal records, rare journals, and newspapers

clippings. The body of work covers 1913-1937. Although it has not yet been properly

arranged and described, there is already a postgraduate student who is writing

her M.A. thesis on this work.

http://gateway1.uvic.ca/spcoll/Arch/Hud.html

SC132 Hudec, Laszlo

Laszlo Hudec fonds. 1913-1937. 80 cm of textual records, ca. 550 architectural

drawings, ca 100 photographs. Laszlo Hudec a Slovakian, was born in 1893 in

northern Hungary, or what is now central Czechoslovakia. When a teenager, his

father, a builder, encouraged Laszlo to work in all aspects of the trade. From

1911 to 1914 Hudec studied architecture at the Budapest University. The advent

of World War I coincided with the completion of his degree. He joined the Austro-Hungarian

army, only to be caught by the Russians in 1916 and sent to prison camp in Siberia.

Two years later, in 1918, Hudec escaped from a prisoner of war train close to

the Chinese border. Hudec made his way down from Siberia into China to eventually

arrived in Shanghai. In Shanghai Hudec joined the American architectural firm,

R. A. Curry. In the space of seven years, Hudec had several major projects under

his belt, and by 1925 he had established his own office and a place as one of

the leading architects in the city. By 1941, he had built at least 37 buildings

as well as numerous other undocumented private residences. Hudec left in 1946

for America, living in Berkeley, California, until his death in 1958. The archive

consists of approximately 550 presentation drawings, sketches, conceptual drawings,

working drawings, technical drawings (inclusive of blueprints), travel sketches

and photographs. These include exterior and interior renderings of plans and

designs for work produced in both Europe and in China. The architectural collection

consists of works by Hudec and two other unknown authors. The work of Hudec

is transcribed in English, German and Chinese characters. The work of the unknown

authors is transcribed in Hungarian and German. There are also 2 boxes of textual

records including notes, notebooks, photo albums, documents, letters, memos,

scrapbooks, photos, legal records, rare journals, and newspapers clippings.

The body of work covers 1913-1937. A temporary finding aid has been prepared

by Lenore Hietkamp of the Maltwood Museum.

http://gateway1.uvic.ca/spcoll/photo.html

Lenore Hietkamp,

"THE PARK HOTEL, SHANGHAI (1931-1934) AND ITS ARCHITECT, LASZLO HUDEC (1893-1958):

"TALLEST BUILDING IN THE FAR EAST" AS METAPHOR FOR PRE-COMMUNIST SHANGHAI."

History in Art Completed M. A. Theses (1998)

[The Park

Hotel (Guoji fandian) remained the highest building (83,8 m.) in Shanghai until

1985.]

http://myhome.naver.com/ucnet2006/Asia-China/Shanghai/WFAasi%20China-Shanghai%20Park%20Hotel-01.jpg

http://www.china.org.cn/english/2001/Sep/19723.htm

http://app1.chinadaily.com.cn/star/2002/0509/cu18-2.html

http://www.han-yuan.com/shudian/alastlook/shhai49.htm

http://www.han-yuan.com/shudian/alastlook/shhai50.htm

http://www.cts01.hss.uts.edu.au/ShanghaiSite/spath/scomm/scommstory1.html

http://www.shanghai-ed.com/tess/bundbeyond02.php