ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

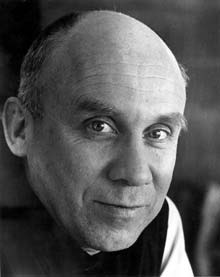

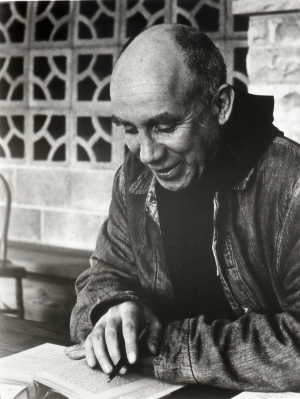

Thomas Merton (1915-1968)

Tartalom |

Contents |

|

A zen és a falánk madarak PDF: Sirató a büszke világért. Válogatott versek PDF: A csend szava. Válogatás Thomas Merton műveiből PDF: Hétlépcsős hegy |

The Zen Revival (1964) PDF: Zen and the Birds of Appetite PDF: A Christian Looks at Zen (1967) PDF: Thoughts on the East PDF: The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton Poems The Zen in Thomas Merton PDF: Merton’s Dialogue with Zen: Pioneering or Passé? PDF: Thomas Merton’s convivial encounter with Buddhism, pp. 80-86. PDF: The Wisdom of the Desert |

https://hu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Merton

Thomas Merton (1915-1968): új-zélandi és amerikai művészszülők gyermeke. Tanulmányait Franciaországban, Angliában és Amerikában végzi. 1938-ban a Columbia Egyetemen szerez bölcsészdiplomát, majd ugyanott doktorátust. Egy hindu szerzetessel történő találkozás gyökeresen megváltoztatja életét, rövidesen megkeresztelkedik, majd a papi hivatás felé fordul. 1939-ben ferences szerzetesnek jelentkezik, majd visszavonja jelentkezését. 1940-ben nagyheti lelkigyakorlatra megy az Our Lady of Gethsemani nevű kolos-torba, ugyanez év decemberében posztulánsként felvételét kéri a Szent Benedek reguláját szigorúan értelmező cisztercita rendbe. 1942-ben öltözik novíciusi habitusba, rendi neve: Louis. 1947-ben örök fogadalmat tesz. 1948-ban publikálják Hétlépcsős hegy c. művét, mely rövidesen "bestseller" lesz, többszázezer pédányban kel el. 1949-ben pappá szentelik. 1953-ban publikálják újabb siker-könyvét, a Jónás jelét. 1955-ben novícius-mester lesz. 1958-tól a világtól félrevonuló szemlélődés helyett a világ szükségletei iránt nyitott misztika felé fordul. 1961-től tanulmányozni kezdi kelet vallási felfogását. 1964-ben találkozik egy zen tudóssal, majd a kolostorban lelkigyakorlatot szervez az erőszakmentességről. 1965-ben a Gethsemani kolostor területén épült remeteségbe költözik. 1966-ban egy buddhista szerzetes látogat a kolostorba, aki mély benyomást tesz rá és a közösségre. Folyamatosan jelennek meg újabb művei és verseskötete.1968-ban Bangkokba utazik egy konferenciára a vallások közötti monasztikus életről. Indiában találkozik a Dalai Lámával, Sri Lankán buddhista kegyhelyeket látogat. December 10-én halálos áramütés éri egy zárlatos ventillátortól.

Vajon mi késztette Thomas Mertont, a jómódú polgárfiút, hogy lemondva a fogyasztói társadalom kínálta javakról a legszigorúbb, aszkétikus fegyelemben élő ciszterci rend tagja legyen? Vajon miért vágták le hajukat, öltöttek szerzetesi habitust, dolgoztak az apátság földjein, böjtöltek, aludtak szalmazsákon és imádkoztak fél éjszakákat a Marlboro, a Coca-Cola és a rock and roll Amerikájának fiataljai? Merton, szerzetesi nevén Louis testvér közel egy évtizedes hallgatás után rendi felettesei utasítására tollat fog, hogy megossza a világgal a szemlélődő hivatás rejtett kincseit. Később, már világhírű íróként ismét előlép a Gethsemani kolostor csendjéből, hogy a monasztikus hagyomány ösvényein tovább haladva megvalósítsa élete nagy álmát: kelet és nyugat szintézisét. Ebben akadályozza meg váratlan, tragikus halála.

Jelként is értelmezhetjük azt a titokzatos keretet, mely Thomas Merton életét körülöleli. Doktori tanulmányai idején, 1938-ban még ateistaként a Columbia Egyetemen találkozik egy Brahmacsárí nevű indiai szerzetessel, aki mestere kérésére jött Amerikába vallásfilozófiát tanulni. Mezítlábas bocskorban, egy szál vászonruhában hol itt, hol ott tűnik fel. Sorra szerzi a legnevesebb egyetemek diplomáit és doktori fokozatát, majd ahogy jött, olyan váratlanul eltűnik. Brahmacsárít nem téveszti meg a nyugtalan, lázadó szellemű polgárfiú. Megérzi benne azt a titokzatos hívást, mely más életre szólítja őt. Mélységes alázattal nem hinduvá akarja téríteni, hanem azt ajánlja neki, amire meglátása szerint szüksége van: olvassa Szent Ágoston Vallomások-át és Kempis Tamás Krisztus követése-t. E két könyv alapjában rengeti meg Merton elképzelését életről, hivatásról. Alig egy évre rá megkeresztelkedik, majd pár év múlva a középkori fegyelemben élő ciszterci rend novíciusa lesz. A hindu szerzetes sosem tudta meg, mit indított el barátja lelkében.

Merton életének másik végpontja a vallások megbékélésével foglalkozó 1968-as bangkoki konferencia. A ciszterci remete, a kongresszus vezéregyénisége akkor már világhírű író, akinek lelkiségi könyveit milliós példányszámban adják el. Elutazása előtt azt írja barátainak: "ázsiai tartózkodásom időtartama egyelőre bizonytalan." A tanácskozás egyik szünetében rejtélyes áramütés éri. Pár nappal korábban álmot lát, melyben a keleti szerzetesek sáfrányszínű öltözékét hordja, s arról beszél, hogy a nyugati vallások megmaradása függhet attól, miként tudják átvenni és tanításukba ötvözni kelet gazdag hagyományát.

Szerzetesi életének legkorábbi felismerései közé tartozik, melyről első sikerkönyve, a Hétlépcsős hegy lapjain ír, hogy az emberi lét legmélyén sajátos paradoxon rejlik. Amíg ezt fel nem fogja, nem lehet tartósan boldog az emberi lélek. Az ellentmondás a következő: az ember a természet rendjében létezik, ugyanakkor ebben tud legkevesebbet tenni azért, hogy megoldja létének legfontosabb problémáit. Ha csak a természetéhez, filozófiájához, erkölcsi követelményeihez igazodik, akkor a pokolban lyukad ki. A saját vágyait követő Jónás prófétát a világ minden mocskával egy cethal nyeli el, s csak Isten felé forduló, dicsőítő fohászai, igaz hite és hivatásának elfogadása hozza ki az alvilág gyomrából.

Mertonra rendkívüli hatással volt az indiai kultúra mélyen vallásos jellege, mely különösen a szemlélődésre helyez nagy hangsúlyt. Kelet kontemplatív magatartása igazából rejtély marad a nyugati gondolkodás számára. A nyugati ember a tettekre elhivatott. Expanzióra törekvő szelleme mindent meg akar ismerni, meg akar szerezni. Leköti a tudomány és a technika világa, minden kézzel fogható, mérhető számára. A természet titkainak kutatásakor már a végtelent ostromolja, de ez még mindig nem elég neki. Megismerésében is a birtoklás vágya mozgatja. A hirdetések és reklámhadjáratok nyomán egy fogyasztói szemlélet ördögi körébe kerül, mely sebesen távolítja léte igazi titkaitól. A Lét azonban visszajelez. Feszültség, frusztráció, csillapíthatatlan éhség jön a várt nyugalom helyett.

Az indiai társadalomban Mertont az ragadta meg, hogy a dolgok birtoklásánál fontosabb a lelki függetlenség, melynek első feltétele az anyagi javaktól való függetlenség. Ez esetenként a szegénység számunkra elképzelhetetlen fokán nyilvánul meg. A nyugati ember sokszor a lemondást is úgy értelmezi, hogy azért legyenek meg számára a létszükségleti cikkei, sőt annál egy kicsit több is. Emiatt kelt gyakran mosolyt a nyugati lemondott rendek életmódja keleti missziójuk során. Indiában a lelki függetlenedést leginkább a cölibátusban élő szerzetesek gyakorolják, de megható az, ahogyan a világban élő emberek is tesznek erőfeszítést ennek érdekében, például mértéktartó táplálkozás, öltözködés, szórakozás és "birtoklás" útján. Merton szerint a lelki függetlenség legfőbb célja, hogy az ember mindenekelőtt "lenni" és ne "birtokolni" akarjon. A gyakorlatban a lét akkor kerülhet a birtoklás fölé, ha az ember eltávolodik önző énjétől és személyisége alapvető kincsei felé fordul. Belső kaland című, kéziratban maradt művében így ír a szemlélődés első lépéseiről: "Az első lépés, amit meg kell tennünk, mielőtt a szemlélődésről kezdünk gondolkodni, természetes egységünk visszanyerése, darabokra hullott életünk egységbe rendezése, hogy újra megtanuljunk harmonikus emberi lényként élni. Ez annyit jelent, életünk szétzilált darabjait össze kell szednünk, hogy az én szót kiejtve valóban legyen valami, amire a névmás utal."

A szemlélődés gyümölcsei-ben folytatja: "Mielőtt fel tudnánk fogni, kik vagyunk, annak a ténynek kell tudatára ébrednünk, hogy az a személy, akinek itt és most gondoljuk magunkat, legjobb esetben is csak egy idegen, egy betolakodó. A hamis empirikus énünk olyan álarc, amely elfedi igazi énünket, önazonosságunkat, ahogy Isten szeretete és a kegyelem előtt csupaszon megállunk majd." Napjainkban a társadalmi érdekeltség horizontális teológiáját követve az emberek teljes lényükkel embertársaik vagy önmegvalósításuk irányába fordulnak. Ezen kellene változtatni azzal, hogy személyiségüket Isten felé orientálják. Ez az újfajta irányultság (vertikális teológia) a szemlélődő élet legfontosabb követelménye. A létnek társadalmi kérdésekben is elsőbbséget kellene élveznie a tett és a birtoklás előtt. E befelé tekintő lelkiséget nevezte Merton a "lét spiritualitásának". Minden igaz társa-dalmi mozgásnak ezen a valóságszemléleten kellene nyugodnia.

"Nemcsak az anyag szükségszerűségnek való alávetettsége az egyik képe a mi engedelmességünknek, de maga a szükségszerűség is képe a kegyelem természetfeletti műveletének."

(Simone Weil)"Elsőként azt kell szem előtt tartanunk Istenkeresésünkben, hogy bizonyos értelemben lényegünk legmélyén máris Isten rabjai vagyunk. Csak az keres-heti Őt, aki korábban már rátalált, s csak az találhat rá, akit Ő valamilyen formában már megtalált" írja A csendes élet című írásában. "Folytonos keresésünk kevéssé jelenti holmi aszketikus technikák gyakorlását, mint inkább teljes életünk lecsendesítését és megregulázását az önmegtagadás, az imádság és a jó cselekedetek által, hogy maga Isten, aki jobban keres minket, esz mint mi Őt, »megtalálhasson« és birtokába vehessen bennünket" folytatja az Élet és szentség lapjain. "Sohasem fogunk azonban eljutni annak felismerésére, hogy kinek a birtokában vagyunk, ha csak rá nem ébredünk saját semmi voltunkra és ürességünkre. Ehhez külső, empirikus énünket teljesen alá kell rendelnünk Isten szeretetének és így megfeledkezve önmagunkról, mint gondolatunk tárgyáról, megszabadulunk attól, ami illuzórikus és felszínes, ami igazi énünket elfedi, hogy visszanyerjük azt a hűbb és mélyebb önmagunkat, amely Isten képmása bennünk" írja ázsiai tapasztalatai nyomán születetett írásaiban. Merton szerint korunk legnagyobb veszélye, hogy életünk alapjának ezt az illuzórikus lényünket tekintjük, és hajlunk a felszínes perszonalizmusra, amely egyenlőségjelet tesz a személy és a külső vagy empirikus ego közé, majd túlzott erőfeszítéssel e hamis ént kultiválja. Ennek eredménye napjaink individualizmusa, mely végső soron álspirituális és morális köntösbe bújtatott gazdasági koncepció.

Ilyen társadalmi környezetben különösen fontos, hogy az ember megszívlelje a belső életre hívás fontosságát, mely jóval több a törvények, az erkölcsi és vallási normák, a közösség szabályainak puszta betartásánál. A belső élet személyes elkötelezettséget kíván tőlünk, önmagunk fenntartás nélküli átadását, szívünk legintimebb szférájának felszínre hozatalát és megosztását Istennel. Ugyancsak ázsiai tapasztalatai hatására élete utolsó éveiben Merton kedvelt témája volt a tudat transzformációja, mely az empirikus vagy hamis én felismerésekor és az igazi én ébredésekor kezdődik meg az individuumban. Hatására az egyén többé már nem elszigetelt egoként tud önmagáról, hanem önmagát léte alapján látja függeni Mástól. Többé nem gondol önmagára sem reflexiója alanyaként, sem tárgyként, hanem Istenben elrejtve találja magát. "Így, öntudata átalakultával maga az individuum is átformálódik. Énje már nem központja többé önmagának, a központba Isten kerül." (Az új tudatosság)

Merton a szemlélődő hivatás alappillérének a jó lelkivezetést tartotta, melynek gyakorlatát évszázadokon át megőrizte az egyház, s melyben nagy szentjei születtek: Benedek, Gergely, Bernát, Tamás, Bonaventura, Sziénai Katalin, Keresztes János, Avilai Teréz.

A vallásos életben már többéves tapasztalattal rendelkezők képesek magukat irányítani, de néha még Nekik is szükségük lehet vezetői tanácsra. Egyetlen hívő sem állíthatja, hogy soha, semmilyen lelki útbaigazításra sem szorult. Ugyanakkor "ezerből jó ha egy ember alkalmas a lelkivezetés szerepének betöltésére, melynek ismertetői a szeretet, a tudás és a megfontoltság"- idézi Keresztes Szent Jánost Louis testvér, aki rendjének novícius mestereként maga is kiváló lelki vezető hírében állt.

Meg volt győződve arról, mennyire fontos lenne viszszatérni a lelkivezető régi hagyományához. Ebben is elbűvölte kelet hagyománya. Csodálattal írt arról, milyen fontos szerepet játszik az indiai emberek vallásos életében a guru. "A guru Isten embere, az a bölcs, az a szent ember, aki szavain és saját életén keresztül tanítja, hogyan éljünk, azt tanítja, mit kell tennünk, hogy » le-gyünk«, Ázsiai útinapló-jában arról is ír, hogy az indiai emberek néha több száz kilométert megtesznek, hogy egy ilyen bölcs emberrel találkozhassanak. Néha csak a megpillantásában reménykednek, máskor kis ideig hallgatni szeretnék, vagy eligazító, bátorító szót kapni tőle. Mindez nem idegen a zsidó-keresztény hagyománytól sem. Jézust is egyénileg vagy csoportosan, mint tanítót keresték fel és kérlelték: "Mester, tudjuk, hogy igaz vagy és az Isten útját az igazsághoz ragaszkodva tanítod, ... mondd meg tehát nekünk, mi a véleményed..." (Mt 22,16), vagy "Jó Mester, mit tegyek, hogy elnyerjem az örök életet?" (Mk 10,17)

Kolostori élete kezdetén Merton oly módon helyezi a szemlélődést a társadalmi kötelezettségek elé, mintha e kettő egymást kölcsönösen kizárná. Közel egy évtizedes visszavonultság után úgy érzi, egyedüli ok a szerzetességre, hogy megtaláljuk valódi helyünket a világban, de ha azért vonulunk vissza a monasztikus életbe, hogy megszabaduljunk társadalmi kötelezettségeinktől, csak az időt vesztegetjük. Aki úgy érzi, hogy el kell me-nekülnie a világból egy kolostorba, illúzió áldozata, s ráadásul magával cipeli a világot a kolostorba. Ha meg akar szabadulni a világ illúzióitól, rövidesen fel fogja ismerni, hogy ezek éppúgy megvannak őbenne és a monasztikus életben egyaránt, mint az emberek világában. Ha azért választja a kolostor magányát, hogy egyedül lehessen, akkor egyszerűen saját maga világába zárkózik, önzése társaságában. Az igazi szemlélődő a kontempláción keresztül arra törekszik, hogy felfedezze, mi hamis és mi igaz a világból, s bár legszembetűnőbb vonása az ima és a magány, részt kell vennie a világban.

Thomas Merton számára kolostori magányos évei után az volt a legnagyobb felismerés, hogy meglelt hivatásában mennyi mindent köszönhet másoknak. Rájött, hogy ő maga is akkor válhat igazi szerzetessé, ha szereti és segíti embertársait. Bár továbbra is rámutatott a világ hibáira és perverzióira, ettől kezdve nem arra biztatta az átlagpolgárt, hogy szerzetesnek álljon. Aki orvosolni akarja a modern élet betegségeit, az a szemlélődő életet a világban is megélheti. Sőt, egyenesen hangsúlyozza, nagy szükség van szemlélődő laikusokra is, akik tevőlegesen részt vesznek a társadalom életében. A szemlélődő szerzetességről az a véleménye, hogy a monasztikus életformát nem szabad minden ember számára mércének tekinteni. Az emberek szemlélődő életre is különböző szinten kapnak meghívást, mely nagyban függ élethelyzetüktől, hivatásuktól. A szemlélődés mindenki életének szerves része kell legyen, aki a lelki és társadalmi megváltás isteni üzenetét közvetíteni akarja, aki vágyik Isten akaratának jobb megértésére. A monasztikus szerzetesség számára a magány, a félrevonulás a természetes közeg, de azt javasolja a társadalomban élő embereknek is, hogy mindenkinek legyen olyan helye, ahol senki nem háborgatja, ahová rendszeres időközökben elvonul szemlélődni, hogy amikor visszatér, és itt találkozik monasztikus és világi szemlélődő hivatás jobban szerethesse a világot.

A szemlélődés rendet, összefüggést és távlatot visz az ember életébe azáltal, hogy lelki közösséget teremt Istennel. Merton szerint minden ember születése pillanatától hamis énje rabja, és ahogy növekszik, hamis énje is erősödik, egyre makacsabbá válik, beárnyékolja igazi énjét. Az ember lelki boldogsága azon múlik, képes-e eltávolítani a hamis maszkot, és feltárni valódi azonosságát. Csak ekkor találhat igazi boldogságra és békére. A földön csak az jelenthet igazi örömet, ha sikerül kiszabadulni önzésünk börtönéből és a szeretet által egységre jutunk azzal, aki minden élet forrása és minden teremtményben benne él. Usque ad temetipsum occure Deo tuo – mondja Szent Bernát nyomán. "Ha meg akarjuk találni Istenünket, először rá kell találnunk igazi önmagunkra."

Merton vallásosságában az intézményes, a társadalmi és az intellektuális elem mellett a misztikának van legnagyobb szerepe. Nyugodtan állíthatjuk, az egyház legnagyobb misztikusai közt van a helye. Annak ellenére, hogy életművének elemzői szerint gondolatvilága és munkamódszere a tradicionális misztikus teológiában gyökerezik, melyben sosem lépi át a katolicizmus szimbólumait és struktúráit, sikerült valami egészen újat hozzátennie két évezred keresztény misztikájához. Ennek titka az, hogy képes volt meglátni más vallások misztikus tapasztalataiban azokat az ősi, egyetemes igazságokat, melyek az emberiség vallási örökségének közös kincsei. A szemlélődésre vetítve mondhatjuk azt is, hogy katolizálni akarta a kontemplációt, a katolikus szót a legtágabb, egyetemes jelentésében értve. Ugyanígy az ökumenizmust sem a hagyományos módon, csupán a keresztény vallásokra értette, hanem az egész világot átfogó, univerzális értelemben. Ehhez szolgált alapul a keleti szemlélődőkkel folytatott párbeszéde, melyet egy vallásközi párbeszéd első lépésének tekintett. Élete utolsó éveiben arról ír, hogy a szemlélődés-központú keleti hagyomány a kereszténység számára új távlatokat kínál, melytől annak lelki és fizikai túlélése múlhat. E vallási szintézis megteremtésén munkálkodva érte korai, tragikus halála.

Thomas Merton on Zen

The Zen Revival

London : Buddhist Society, 1971, [4], 20 p.

Originally published in 'Continuum' 1, Winter 1964. pp. 523-538.

PDF: Mystics and Zen Masters

New York : Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1967, 303 p.

Contents: Mystics and Zen masters -- Classic Chinese thought -- Love and Tao -- The Jesuits in China -- From pilgrimage to crusade -- Virginity and humanism in the Western fathers -- The English mystics -- Self-knowledge in Gertrude More and Augustine Baker -- Russian mystics -- Protestant monasticism -- Pleasant Hill -- Contemplation and dialogue -- Zen Buddhist monasticism -- The Zen Koan -- The other side of despair -- Buddhism and the modern world.

PDF: Zen and the Birds of Appetite

New York : New Directions, 1968. 141 p.

http://books.google.hu/books/about/Zen_and_the_Birds_of_Appetite.html?id=GPAsAQAAIAAJ&redir_esc=y

Contents [First published in...]:

The Study of Zen [Cimarron Review, Oklahoma State University, June, 1968.]

New Consciousness [R.M. Bucke Memorial Society's Newsletter-Review, Montreal, Vol. II, No. 1, April, 1967.]

A Christian Looks at Zen [Introduction to John C.H. Wu's The Golden Age of Zen. Taipei, 1967.]

D.T. Suzuki : The Man and His Work [The Eastern Buddhist, New Series, Vol. II, No. 1, Kyoto, August, 1967. pp. 3-9.]

Nishida : A Zen Philosopher

Transcendent Experience [R.M. Bucke Memorial Society's Newsletter-Review, Montreal, Vol. I, No. 2, September, 1966.]

Nirvana [Journal of Religious Thought, Howard University, Vol. XXIV, No. 1, 1967-68.]

Zen in Japanese Art [The Catholic Worker, July-August, 1967.]

Appendix : Is Buddhism Life-Denying?

Wisdom in Emptiness : A dialogue / D.T. Suzuki and Thomas Merton. [New Directions 17, 1961]

PDF: The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton

New York : New Directions Pub. Corp., 1973, 445 p.

Edited from his original notebooks by Naomi Burton, Patrick Hart & James Laughlin. Consulting editor: Amiya Chakravarty.

Merton's pilgrimage to Asia, reaching out in ecumenism to Islam, Zen, Sufism, and Buddhism, but not breaking from his Christian roots.

Thomas Merton on Zen

London : Sheldon Press, 1976. 144 p.

A selection of the author's writings published between 1961 and 1968.

PDF: Thoughts on the East

New York : New Directions Books, 1995; Kent [England] : Burns & Oates, 1996. eBook

Contents: Introduction - Thomas Merton and the monks of Asia, by George Woodcock; Thomas Merton on Taoism; on Zen; on Hinduism; on Sufism; on varieties of Buddhism;

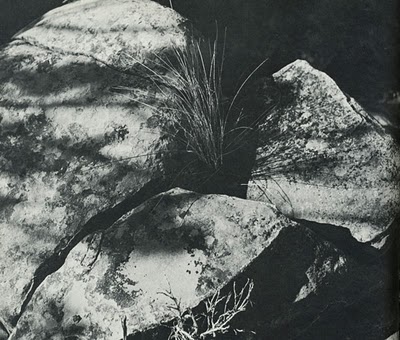

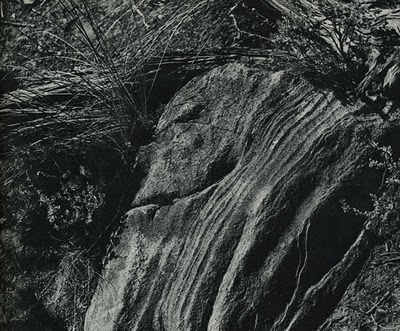

A hidden wholeness : the Zen photography of Thomas Merton

Catalog from an exhibition of photographs held at the McGrath Art Gallery, Bellarmine University, Louisville, Kentucky,

November 19th 2004 - January 5th 2005.

Includes essays by Paul M Pearson, Deba P. Patnaik, and Bonnie B. Thurston.

Edited and introduced by Paul M Pearson.

Louisville, KY. : Thomas Merton Center, 2004. 36 p.

http://www.merton.org/hiddenwholeness/exhibit.aspx

Photographs and drawings by Thomas Merton

http://fatherlouie.blogspot.hu/search?updated-min=2006-01-01T00:00:00-05:00&updated-max=2007-01-01T00:00:00-05:00&max-results=17

Thomas Merton

The Zen Revival

London : Buddhist Society, 1971,

[4], 20 p.

Originally published in 'Continuum' 1, Winter 1964. pp. 523-538.

FOREWORD

The whole world of spiritual affairs suffered a loss with the death of

Father Thomas Merton, who died in December, 1968 at the age of fifty

three. He was already well known as an English journalist when he entered

the Church of Rome, and achieved fame with his autobiographical work

"The Seven Storey Mountain", A year later he was ordained, and thereafter

lived in the Trappist monastery of Our Lady of Gethsemani in Kentucky.

He was fascinated with Zen Buddhism, and his Mystics and Zen Masters

will rank as a classic for all interested in Zen.

He was a remarkable man in that by the power of his enlightenment,

however labelled, he formed a bridge between the Church of Rome and

Zen Buddhism where alone such union can be made, at the highest level

of each. For him the limitations and imperfections of both were no longer

barriers to the light which, in pure experience, he found to be theirs in

common. His was indeed a brilliantly illumined mind.

He had known of the writings of Dr. D. T. Suzuki for a long time

and had corresponded with him. It seemed inevitable that the two would

meet, and the meeting, in June, 1964, belongs to the history of Zen

Buddhism and perhaps of the Catholic Church. Mr. Lunsford Yandell, a

friend of both men, described it in the Memorial issue of the Eastern

Buddhist as follows:

"I found Dr. Suzuki at his cheerful best. He said that on the day before

my visit Father Thomas Merton had come to see him, and he spoke

with great warmth of his unusually deep insight into Zen. He gave me an

article on Zen by Father Merton to read, published a short time before in

Continuum, saying, "There is more true understanding of Zen in this

article than anything I have eyer read by a Western writer". Mr. Yandell

adds, "Father Merton, for his part, wrote a week after Dr. Suzuki died,

"I share your deep sorrow at the loss of so great a man as Dr. Suzuki,

whom I certainly regard as one of the spiritual masters of our time".

Thanks to Mr. Yandell a copy of the article came into the hands of

the Buddhist Society, and I at once wrote to the Editor of the journal,

Continuum, in which it first appeared in Winter 1969 [1964 !]. The Editor,

Mr. J. G. Lawler, has kindly given the Society permission to reproduce it

in pamphlet form. Here, then with this minimum Foreword, is the article

itself, in which Father Merton made clear to Dr. Suzuki the depth and

quality of his understanding of Zen, not merely as a scholar but in terms

of his own enlightenment

Christmas Humphreys

Publisher to the Buddhist Society, London.

THE ZEN REVIVAL

Zen Buddhism is often dismissed as one of those "ancient cosmic religions"

which has had all the props knocked out from under it by modern science.

It is one of those which is, in Teilhard's words, "steeped in a pessimistic

and passive mysticism," and cannot adjust itself "to the precise immensities

nor to the constructive requirements of space-time." Of Zen and Neo-

Vedanta, R. C. Zaehner says in his recently published Matter and Spirit,

"they may satisfy some individuals for a short time, [but] they plainly can

never be integrated into modern society."[1] Yet true as this may be, in fact,

we must nevertheless admit that the nature of Zen is not such that its

existence and survival in the new world of technology and collectivity is

a priori excluded.

It is certainly not easy to conceive Zen as a powerful social force in the

modern world, even in the Orient. It is also quite true that the Zen craze

in the United States has about it everything that Zaehner justly dismisses as

trivial and irrelevant. But can we truly dismiss Zen as "passive mysticism"?

Is it mysticism at all? Is it a "way of salvation"? Is it individualistic?

Is it "subjective"? These are not easy questions to answer, with any amount

of exactitude, though it can be said from the start that terms like

"mysticism", "passivity", "subjectivity" and so on, especially the term

"religion" cannot be applied to Zen without very strict qualifications and

indeed they should perhaps not normally be applied to it at all.

One of the most thorough recent attempts to explain Zen by tracing its

history is the work of a Jesuit scholar who has spent years in Japan. This

book is very clear, full of new material, and, in spite of certain limitations

of perspective, it is probably the best and most comprehensive history of

Zen that has yet appeared in any western language.[2] Heinrich Dumoulin

is no novice in the study of Zen Buddhism. For over twenty-five years he

has been publishing articles in learned oriental journals on this subject,

and in 1953 an English translation of a preliminary study, of which the

present book is a full development, was published by the First Zen

Institute of America.[3] Hence it is clear, that we are dealing with a widely

recognized western authority on Zen, and with one who, besides having a

[1] Matter and Spirit: Their Convergence in Eastern Religions, Marx and Teilhard de

Chardin, New York, Harper and Row, 1963, p. 185.

[2] A History of Zen Buddhism, by Heinrich Dumoulin, S.J., trans. by Paul Peachey,

Pantheon Books, New York, 1963.

[3] The Development of Clrinese Zen, by Heinrich Dumoulin, S.J., trans. by Ruth Fuller

Sasaki, New York, First Zen Institute of America, 1953.

profound insight into Japanese religion and culture, is a Christian scholar

and theologian. This book makes it possible for the average Christian

student to advance, with a certain amount of security and confidence, into

a very mysterious realm.

Buddhism is generally tagged in the West as "selfish", even though the

professed aim of the discipline from the very start is to attack and overcome

that attachment to individual survival which is believed to be the

source of every woe. The truth is that the deep paradoxes and ambiguities

of Buddhism have led most Westerners to treat it as a mixture of incomprehensible

myths, superstitions and self-hypnotic rites, all without

serious importance.

The first Jesuits in Japan made no such mistakes. Like St. Francis

Xavier, they had a very healthy respect amd curiosity for the thought and

spirituality of "the bonzes":

"I have spoken with several learned bonzes, especially with one who is held

in high esteem here by everyone, as much for his knowledge, conduct and

dignity as for his great age of eighty years. His name is Ninshitsu, which in

Japanese signifies "Heart of Truth". He is among them as a bishop, and

if his name is appropriate, he is indeed a blessed man. . . It is a marvel

how good a friend this man is to me." [A History of Zen Buddhism, pp. 199-200.]

Though Japanese religion was then in a state of decline, the Jesuits quickly

found that the Zen temples were still, in spite of serious abuses, the

centres of a very real spiritual life. It is true that the many-sided manifestations

of Buddhist life and thought were not always easy to grasp or

entirely congenial. Nor was it possible to expect men trained in scholastic

theology and Aristotelian logic to take kindly to the outrageous paradoxes

of Zen which is aggressively opposed to all forms of logical analysis.

A genuine dialogue between the Jesuits and the Zen masters was no

simple matter, especially on the highest level which Fr. Dumoulin does

not hesitate to qualify as "mystical".

On the cultural level, however, the encounter was relatively easy. The

Jesuits were entirely charmed with the subtlety, the refinement, the perfection

of taste and the good order that reigned even more in the Zen

temples than everywhere else around them. Hence they did not hesitate

to exercise their characteristic flair for adaptation, and to model the outward

forms and ceremonies of their community life in Japan on those of

the Zen monks. Indeed, it was altogether logical for them to do so, since

they were not blinded by the illusion of so many other missionaries who

tended to identify the accidental outward forms of European culture with

essentials of Christian piety. St. Francis Xavier, who seems to have been entirely

free from illusion in this respect, did not hesitate to say of the Japanese

in general: "In their culture, their social usage and their mores, they

surpass the Spaniards so greatly that one must be ashamed to say

so."

The famous Jesuit Visitator of the Oriental province, Valignano, strongly

urged the missionaries to associate with the Zen monks. This meant

participation in the quasi-religious "tea Ceremony", in which the Jesuits

not only took a keen interest, but which they practiced with a relatively

consummate artistry, sharing with their Zen friends a real appreciation of

its spiritual implications. One Jesuit has left us a moving account of his

impressions in a sixteenth-century Portuguese manuscript, an excerpt

of which has been published for the first time by Fr. Dumoulin:

"This art of tea is a kind of religion of solitude. It was established by the

originators in order to promote good habits and moderation in all things

among those who dedicate themselves to it. In this way they imitate the

Zen philosophers in their meditation as do the philosophers of the other

schools of Indian wisdom. Much rather they hold the things of this world

in low esteem, they break away from them and deaden their passions

through specific exercises and enigmatic metaphorical devices which

at the outset serve as guides. They give themselves to contemplation of

natural things. Of themselves they arrive at the knowledge of the original

cause in that they come to see things themselves. In the consideration of

their mind they eliminate that which is evil and imperfect until they come

to grasp the natural perfection and the being of the First Cause.

Therefore these philosophers customarily do not dispute or argue

with others, rather allowing each person to consider things for himself,

in order that he may draw understanding from the ground of his own being.

For this reason they do not instruct even their own disciples. The teachers

of this school are also imbued with a determined and decisive spirit without

indolence or negligence, without luke-warmness or effeminacy. They decline

the abundance of things for their personal use as superfluous and unnecessary.

They regard sparsity and moderation in all things as the most

important matter and as being beneficial to the hermit...This they combine

with the greatest equanimity and tranquillity of mind and outer modesty

... after the manner of the Stoics who thought that the consummate

person neither possesses nor feels any passion.

The adherents of cha-no-yu claim to be followers of these solitary

philosophers. Therefore all teachers of this art even though they be

unbelievers otherwise, are members of the Zen school or become such,

even if their ancestors belonged to some other persuasion. Though they

imitate this Zen ceremony, they observe neither superstition nor cult,

nor any other special religious ritual, since they adopt none of these things

from it. Rather they copy only their cenobitic solitude and separation

from the activities of life in the world, as also their resolution and readiness

of mind, eschewing laxity or indolence, pomp or effeminacy. Also in their

contemplation of natural things, these practitioners imitate Zen, not

indeed with regard to tbe goal of the knowledge of being and the perfection

of original being, but rather only in that they see in those things the outer

tangible and natural forms which move the mind and incite to solitude

and tranquillity and detachment from the noise and proud stirring of the

world." [A History of Zen Buddhism, pp. 214-215.]

There are several instances of Zen Masters who became Christians in the

early days of the Japanese mission, along with some of the "Tea-Masters"

who were not always members of the Zen sect. But the relations between

the Jesuits and the Zen monks did not always remain friendly. There was

a certain amount of ambivalence and misunderstanding. In fact, when the

great persecution of Japanese Christians began, some of the Zen abbots

were among the most zealous in instigating it. The reasons for this were

extremely complex and we do not need to go into them here.

What, exactly, is Zen? If we read the laconic and sometimes rather

violent stories of the Zen Masters, we find that this is a dangerously

loaded question: dangerous above all because the Zen tradition absolutely

refuses to tolerate any abstract or theoretical answer. In fact, it must be

said at the outset that philosophically or dogmatically speaking, the

question probably has no satisfactory answer. The word Zen comes from

the Chinese Ch'an which designates a certain type of meditation, and is

based on the Sanskrit word dhyana. Zen is therefore not a religion, not

a philosophy, not a system of thought, not a doctrine, not an ascesis.

In calling it a kind of "natural mysticism" Fr. Dumoulin is bravely

submitting to the demands of western thought which is avid, at any price,

for essences. But I think he would not find too many eastern minds who

would fully agree with him on this point, even though he is, in fact,

giving Zen the highest praise he feels a Christian theologian can accord it.

The truth is, Zen does not even lay claim to be "mystical" and the most

widely-read authority on the subject, Daisetz Suzuki, has expended no

little effort in trying to deny the fact that Zen is "mysticism". This,

however, is more a matter of semantics than anything else.

The Zen insight cannot be communicated in any kind of doctrinal

formula or even in any precise phenomenological description. This is

probably what Suzuki means when he says it is "not mystical": that it

does not present clear and definitely recognizable characteristics capable

of being set down in words. True, the genuineness of the Zen illumination

is certainly recognizable, but only by one who has attained the insight

himself. And here of course we run into the first of the abominable pitfalls

that meet anyone who tries to write of Zen. For to suggest that it is "an

experience" which a "subject" is capable of "having" is to use terms that

contradict all the implications of Zen.

Hence it is quite false to imagine that Zen is a sort of individualistic,

subjective purity in which the monk seeks to rest and find spiritual

refreshment. It is not a subtle form of spiritual means of self-gratification, a

repose in the depths of our own silence. Nor is it by any means a simple

withdrawal from the outer world of matter to an inner world of spirit. The

first and most elementary fact about Zen is its abhorrence of this dualistic

division between matter and spirit. Any criticism of Zen that presupposes

such a division in Zen is, therefore, pure nonsense.

Like all forms of Buddhism, Zen seeks an "enlightenment" which

results from the resolution of all subject-object relationships and oppositions

in a pure void. But to call this void a mere negation is to reestablish the

oppositions which are resolved in it. This explains the peculiar insistence

of the Zen Masters on "neither affirming nor denying." Hence it is impossible

to attain satori (enlightenment) merely by quietistic inaction or

the suppression of thought. Yet at the same time "enlightenment" is not

an experience or activity of a thinking and self-conscious subject. Still

less is it a vision of Buddha, or an experience of an I-Thou relationship

with a Supreme Being considered as object of knowledge and perception.

However, Zen does not deny the existence of a Supreme Being. It neither

affirms nor denies, it simply is. One might say that Zen is the awareness of

pure being beyond subject and object.

But the peculiarity of this awareness is that it is not reflexive, not self-conscious,

not philosophical, not theological. It is in some sense entirely

beyond the scope of psychological observation and metaphysical reflection.

For want of a better term we may call it "purely spiritual." In order to

preserve this purely spiritual quality the Zen Masters staunchly refuse to

rationalize or verbalize the Zen experience. They relentlessly destroy all

figments of the mind or imagination that pretend to convey its meaning.

They even go so far as to say: "If you meet the Buddha, kill him!" They

refuse to answer speculative or metaphysical questions except with words

that seem utterly trivial and which are designed to dismiss the question

itself as irrelevant.

When asked - "If all phenomena return to the One, where does the One

return to?" the Zen Master Joshu simply said - "When I lived in Seiju I

made a robe out of hemp that weighed ten pounds." This is a useful and

salutary mondo (saying) for the western reader to remember. It will guard

him against the almost irresistible temptation to think of Zen in neoplatonic

terms. Zen is not a system of pantheistic monism. It is not a

system of any kind. It refuses to make any statements at all about the

metaphysical structure of being and existence. Rather it points to being

itself without indulging in speculation.

Fr. Dumoulin does not attempt to explain Zen, or analyze it. He treats it

with a respectful and historic objectivity. He tells us where it came from,

how it developed and what the various schools were. Though Suzuki and

the other writers on Zen are generally careful to identify the Zen Masters

whom they quote, and to try to situate them in their context, a simple yet

complete historical outline has long been badly needed. Fr. Dumoulin

gives us the whole picture. After some early chapters on Indian Buddhism

with necessary information on Mahayana Sutras (without which Zen is

not fully understandable) he speaks of the introduction of Zen to China

by the semi-legendary Bodhidharrna, a contemporary of St. Benedict in the

west. In point of fact, Zen was not suddenly "introduced" to China by any

one man. It is a product of the gradual combination of Mahayana

Buddhism with Chinese Taoism which was later transported to Japan and

further refined there. Though Bodhidharrna is regarded as the first in a

line of Chinese Zen Patriarchs who have "directly transmitted" the enlightenment

experience of the Buddha without written media or verbal

formulas, the way for Zen was certainly prepared before him. The four

line verse (gatha) attributed to Bodhidharrna, and purporting to contain a

summary or his "doctrine", was actually composed later during the Tang

Dynasty, when Zen reached its highest perfection in China. The verse

reads:

A special tradition outside the scriptures (i.e., sutras);

No dependence upon words and letters;

Direct pointing at the soul of man;

Seeing into one's own nature and the attainment of Buddhahood.

It is clear from this that Zen insists on concrete practice rather than on

study or intellectual meditation; as a way of attaining enlightenment. The

key phrase of this verse is: "direct pointing at the soul of man," and this

is practically repeated in the synonymous phrase that follows: "seeing

into one's own nature." The commonly accepted translation "seeing into

the soul of man" is however rather unfortunate. It suggests clear and formal

opposition between body-soul, spirit and matter, which is not to be found

in Zen, or at least not in the way that such terms might suggest to us.

This, in fact, rather disconcerted St. Francis Xavier when he conversed with

his friend the Zen Master, Ninshitsu. The good old man did not seem to

know whether or not he had "a soul". In fact, to him the concept of "a

soul" as a sort of object that "one" could be considered as "having"

and even "saving" was completely unfamiliar. He sought salvation, indeed,

but this search could only be expressed in utterly different terms.

In other texts of Bodhidharma's verse the word here given as soul is

"mind" (H'sin). But "mind" (H'sin) is more than a psychological concept.

Nor is it equivalent to the scholastic idea of the soul as "form of the body".

Yet it is certainly considered as a principle of being. Suzuki says that

"mind" in this sense is "an ultimate reality which is aware of itself and

is not the seat of our empirical consciousness."[4] This "mind" for the Zen

Masters is not the intellectual faculty as such but rather what the Rhenish

mystics called the "ground" of our soul or of our being, a "ground"

which is not only entitative but enlightened and aware, because it is in

immediate contact with God. The New Testament term that might possibly

correspond to it, though of course with many differences, is St. Paul's

"spirit" or "pneuma".

It must be admitted that a great deal of study remains to be done to

clarify the basic concepts of Buddhism which have usually been translated

by western terms that have quite different implications. We have

habitually taken western metaphysical concepts as equivalent to Buddhist

terms which are not metaphysical but religious or spiritual, that is to say,

expressions not of abstract speculation but of spiritual experience. As a

result we have read our abstract western divisions into an oriental experience

that has nothing whatever to do with them, and we have also

presumed that Oriental contemplation corresponded in every way with

Western philosophical modes of contemplation and spirituality. Hence

the mystifying use of terms like "individualism", "subjectivism", "pantheism",

etc., one on top of the other, in our discussion of something like

[4] Essays in Zen Buddhism, Series III, p. 23, London, 1958.

Zen. Actually these terms are worse than useless. They serve only to

make Zen utterly inaccessible to us.

The Zen insight, as Bodhidharrna indicates, consists in a direct grasp of

"mind" or one's "original nature". And this direct grasp implies rejection

of all conceptual media or methods, so that one arrives at mind by

"having no mind" (wu h'sin): in fact by "being" mind instead of "having"

it. Zen enlightenment is an insight into pure being in all its actual presence

and immediacy. It is a fully alert and super conscious act of being which

transcends time and space. Such is the attainment of the "Buddha mind"

or "Buddhahood". (Compare the Christian expressions, "having the mind

of Christ", being "of one Spirit with Christ"; "He who is united to the

Lord is one Spirit"; though the Buddhist idea takes no account of any

"supernatural order" in our sense.) It is the awareness of full spiritual

reality, the emptiness and absence of all limited or particularized realities.

Hence it is not accurate to say that the Zen insight is a realization of our

own individual spiritual nature, or (as Zaehner would say) of our "pre-biological

unity".

One might ask if our habitual failure to distinguish hetween "empirical

ego" and the "person" has not lead us to oversimplify and falsify our

whole interpretation of Buddhism. There are in Zen certain suggestions

or a higher and more spiritual personalism than one might at first sight

expect. Zen insight is at once a liberation from the limitations of the

individual ego, and a discovery of one's "original nature" and "true face"

in "Mind" which is no longer restricted to the empirical self, but is in all

and above all. Zen insight is less our awareness, than being's awareness of

itself. This is not a submersion or a loss of self in "nature" or "the One". It

is not a withdrawal into one's spiritual essence and a denial of matter and

of the world. On the contrary it is a recognition that the whole world is

aware of itself in me, and that "I" am no longer limited to my individual

and empirical self, still less to a disembodied soul, but that my "identity" is

to be sought not in that separation from all that is, but in oneness with all

that is. This identity is not the denial of my own personal reality but its

highest affirmation. It is a discovery of genuine identity in and with the One,

and this is expressed in the paradox of Zen, from which the concept of

Person in the highest sense is unfortunately absent.

The most critical moment in the history of Chinese Zen is evidently the

split between the Northern and Southern schools in the seventh century.

This extremely complex affair nevertheless has one feature which is

important for the real understanding of Zen: the events which led to the

choosing of the Sixth "Patriarch", Hui Neng. When the time came for Hung-

Jen, the fifth patriarch, to transmit his role and dignity to a successor,

he asked each of his monks to compose a verse which would give evidence

of Zen insight. Presumably the one whose verse was most adequate would

be worthy to succeed Hung-Jen, as Patriarch, because he would be the one

whose Zen enlightenment was most authentic. Foremost among the disciples

of the old man was Shen-hsiu, He was a senior in the community,

outstanding for his experience, and his succession was taken as a foregone

conclusion. He composed a verse which ran as follows:

The body is the Bodhi-tree [under which Buddha was enlightened]

The mind is like a clear mirror standing,

Take care to wipe it all the time

Allow no grain of dust to cling to it.

Anyone familiar with routine descriptions of the contemplative experience

east or west, will recognize this approach: It is, as a matter of fact, very close

to neo-platonism. It suggests (probably more in the translation than in the

original) the familiar Greek division between mind and matter, and it

situates enlightenment in a state of immaterial purity and in the absence

of concepts. It indicates a program of purification and recollection, a

"liberation" of the soul from the terrestrial and temporal condition

imposed on it by the body and the five senses.

As a matter of fact, this is the kind of thing that the western

reader would be perfectly ready to accept as Zen. But it is rejected with

impassioned scorn by the Zen Masters. Another member of that monastic

community, who was not even a monk, but an illiterate working in the kitchen,

reacted against the inadequacy of the verse, and posted another

verse of his own, which he (and his followers in the "Southern School"

of Zen) felt to be more satisfactory. In fact this untrained peasant, Hui

Neng, was preferred to Shen-hsiu and succeeded Hung-Jen as the sixth

patriarch. Here is the verse:

The Bodhi is-not like a tree,

The clear mirror is nowhere standing.[5]

Fundamentally not one thing exists:

Where then is a grain of dust to cling?[5] The exact meaning or the Chinese is apparently, "the clear mirror is without stand".

In other words, the duality, body-soul, is treated as irrelevant to Zen enlightenment.

Here the western reader is likely to be both disconcerted and misled. He

will seize upon the phrase "not one thing exists" in order to account for

his anxieties: but if he thinks this is a statement of fundamental principle,

a declaration of pantheism, he is wrong. As Suzuki says, "When the

Sutras declare all things to be empty, unborn and beyond causation, the

declaration is not the result of metaphysical reasoning; it is a most penetrating

Buddhist experience".[6] As usual, he avoids the use of the word

"mystical" but statements about the "nothingness" of beings and of

"oneness" in Buddhism are to be interpreted just like the figurative terms

of western mystics describing their experience of God: the language is

not metaphysical but poetic and phenomenological. The Zen insight is a

direct grasp of being, but not a formulation of the nature of being. Nor

can the Zen insight be described in psychological terms, and to think of it

as a subjective experience "attainable" by some kind of process of mental

purification is to doom oneself to error and absurdity. This error came to

be described as "mirror-wiping Zen", since it imagines that the mind is

like a mirror which "one" (who?) has to keep clean. To illustrate this,

here is another well-known Zen story:[7]

A Master saw a disciple who was very zealous in meditation.

The Master said: "Virtuous one, what is your aim in practicing Zazen

[meditation]?"

The disciple said: "My aim is to become a Buddha".

Then the Master picked up a tile and began to polish it on a stone in

front or the hermitage.

The disciple said: "What is the Master doing?"

The Master said: "I am polishing this tile to make it a mirror".

The disciple said: "How can you make a mirror by polishing a tile?"

The Master replied: "How can you make a Buddha by practicing Zazen?"

The capital importance of this story is that it shows; once for all, what

Zen is not. It is not a technique of introversion by which one seeks to

exclude matter and the external world, to eliminate distracting thoughts,

and to concentrate on the purity of one's own spiritual essence, whether

or not this essence be regarded as a mirror of the divinity. Zen is not a

mysticism of withdrawal. The way to enlightenment by withdrawal is

definitely closed to it. What remains, then, is to seek insight elsewhere.

But where? One of the common misunderstandings or Zen is to interpret

[6] Essays in Zen, Series III, p. 25.

[7] Development of Chinese Zen, p, 51, Dumoulin, translation. by Ruth Puller Sasaki.

stories like this to mean that sonic of the Zen Maslers attached no importance

to meditation, or thought that no preliminary discipline was required:

enlightenment would come suddenly all by itself. Dumoulin himself

seems to have misinterpreted Hui Neng's doctrine of "sudden enlightenment"

in this way, for he says: "The elimination of all preliminary stages

and the renunciation of all preparatory exercises is the typical Chinese

element in the Zen of Hui Neng".

It is true that Hui Neng did revolutionize Buddhist spirituality by

discounting the practice of formal and prolonged meditation, referred to

as zazen ("sitting in meditation"). Yet it would he utterly misleading to

think that the "renunciation of preparatory exercises" means "no preparation"

or the rejection of formal zazen means "no meditation". This way

of interpreting Hui Neng accounts for the common error that his spirituality,

and that of Zen in general, is "quietistic". Hui Neng was no quietist;

on the contrary, he was reacting against a quietistic type of spirituality.

But his reaction was not activistic either. It was a break through into

something quite original and new. He refused to separate meditation as

a means (dhyana) from enlightenment as an end (prajna). For him, the two

were really inseparable, and the Zen discipline consisted in seeking to

realize this wholeness and unity of prajna and dhyana in all one's acts,

however external, however commonplace, however trivial. For Hui Neng

all life was Zen. Zen could not be found merely by turning away from

life to become absorbed in meditation. Zen is the very awareness of life

living itself in us. When in his verse about the "mirror" Hui Neng

rejected the "mirror wiping" concept of meditation, he was therefore

not rejecting meditation itself, but what he helieved to be a totally wrong

attitude to meditation. We may sum up the "wrong" attitude in the

following terms.

First, it begins with a central-consciousness, an awareness of an empirical

self, an "I" which, with all the good intentions in the world, sets out to

"achieve liberation" or "enlightenment". This is the familiar empirical

ego which is aware of itself, observes itself, remembers itself, and seeks

ways to preserve and perpetuate its self-awareness. This "I" seeks to affirm

itself in its actions, thoughts. and contemplation. In stripping off the

exterior and sensible trappings of superficial experience, the ego seeks to

realize its own inner spiritual nature.

Second, the emperical and self-conscious self then views its own thought

as a kind of object or possession, and in so doing accounts for this thought

by situating it in a separate, isolated "part of itself", a mind, which it

compares to a "mirror". This is also considered as a "possession". "I have a mind".

Thus the mind is regarded not as something I am, but something I own. It then

becomes necessary for me to sit quietly and calmly, recollecting my faculties and

reaching down to experience "my mind".

Third, the empirical self then resolves to purify the mirror of the mind

by removing thoughts from it. When the mirror of the mind is clear of all

thought (so it imagines) the ego will be "liberated". It will affirm itself

freely without thoughts. Why does it aim at this bizarre attainment?

Because it has read in the sutras that enlightenment is a state of "emptiness",

and "suchness". It is an awareness of an inner and transcendental

mind. Presumably if all thoughts of material and contingent things are

kept out of the mirror, then the mirror will be filled with the pure spiritual

light of the Buddha mind, which is a kind of "emptiness". At best, this

contemplation is an ascent from the external and empirical consciousness

of individuality to a higher and more general consciousness of one's

spiritual nature. The lower self is then dissolved in the consciousness of

a nature which transcends the external self.

What has happened is that this clinging and possessive ego-consciousness,

seeking to affirm itself in "liberation", 'craftily tries to outwit reality by

rejecting the thoughts it "possesses" and emptying the mirror of the

mind which it also "possesses". Thus "the mind" will be in "emptiness"

and "poverty". But in reality, "emptiness" itself is regarded as a possession,

and an "attainment". So the ego-consciousness renounces its spiritual

autonomy in order to sink into its spiritual, pre-biologcal nature. But

since this nature is regarded as one's possession, the "spiritualized" ego

thus is able to affirm itself all the more perfectly, and to enjoy its own

narcissism under the guise of "emptiness" and "contemplation".

Now as Hui Neng points out, I think quite rightly from any point of

view, this elaborate mental fabrication is a naive and pointless artifice.

Indeed, it is not only useless, but deceitful and pernicious, since it induces

an illusion that the empirical ego has transcended the conditions of

matter and of egotistical self-hood by sitting in meditation, excluding all

external impressions and resting in the purity of its own mind.

It is quite true to say that the "sun rises" and the "sun sets" according

to our empirical, every-day experience. But such terminology is no longer

adequate for the professional concerns of a space man. So too, the Zen

Masters realized that though the mind is certainly a reality, to speak of

mind as a mirror which is "owned" by the ego and which must be kept

pure by the exclusion of all thoughts was, from the point of view of

Zen understanding, sheer nonsense. Such language does not come anywhere

near giving a proper notion of what true insight is. Hui Neng

therefore described it in other terms, in which, of course, he had been

anticipated by many centuries in the Mahayana Sutras, particularly the

Diamond Sutra. For Hui Neng the central reality in meditation or indeed

in life itself is not the empirical ego, but that ultimate reality which is at

once pure being and pure awareness which we referred to above as "mind"

(h'sin). Because he contrasts it with the "conscious" empirical self, Hui

Neng calls this "ultimate mind" the "Unconscious" (wu nien). (This is

equivalent to the sanskrit Prajna, or wisdom).

It must be said here that the "Unconscious" of Hui Neng is totally different

from the unconscious as it is conceived by modern psychoanalysis. To

confuse these two ideas would be a fatal error. As Bodhidharma said,

the "Unconscious" (prajna) is a principle of being and light secretly at

work in our conscious mind making it aware of transcendent reality. But

this true awareness is not a matter of the empirical ego standing back and

"having ideas", "possessing knowledge" or even "attaining to insight"

(Satori). Here we are dealing not with a Cartesian awareness of a thinking

self but with the vastly different realm of prajna-wisdorn. Hence what

matters now is for the conscious to realize itself as identified with and

illuminated by the Unconscious, in such a way that there is no longer

any division or separation between the two. It is not that the empirical

mind is "absorbed in" Prajna, but simply that Prajna is, and nothing else

has any relevance except as its manifestation.

Indeed it is not the empirical self which "possesses" prajna-wisdorn, or

owns "an unconscious" as one might have a cellar in one's house. In

reality the conscious belongs to the transcendental Unconscious, is

possessed by it and carries out its work, or it should do so. Its destiny is

to manifest in itself the light of that Being in which it subsists, as a Christian

philosopher might say. It becomes one, as we would say, with God's

own light, and St. John's expression, the "Light which enlightens every

man coming into this world", (John 1:9) seems to correspond fairly

closely to the idea of Prajna and of Hui Neng's "Unconscious".

This then is what Hui Neng means by saying that "mirror wiping" is

useless. There is no mirror to be wiped. What we call "our" mind is only

a feeble and flickering reflection of Prajna - the formless and limitless

light. We cannot be enlightened by cutting the reflection off from the

original light and giving it an absolutely autonomous existence which it

cannot possibly have. Another Zen Master said, characteristically, that

there is no enlightenment to be attained and no subject to attain it. "No

one has ever attained it in the past or will ever attain it in the future for

it is beyond attainability. Thus there is nothing to be thought of except

the Unconscious itself. This is called true thought".[8] Therefore

Bodhidharma said, "All the attainments of the Buddhas are really

non-attainments".[9]

As long as the empirical ego stands back and imagines itself to be

illuminated by any light whatever, whether its own or beyond itself, and

strives to see things in its "own mind" as in a mirror, it simply affirms

itself as distinct from a source outside itself to which it must attain,

because it is "separate" and distant. But in actual fact, Hui Neng says,

there is no attainment, and therefore to busy oneself about seeking a

"way" to attainment is pure self-deception. Zen is not "attained" by a

self-conscious mirror-wiping meditation, but by self-forgetfulness in the

existential present of life here and now.

This reminds us of St. John of the Cross and his teaching that the

"Spiritual Way" is falsely conceived if it is thought to be a mere denial

of flesh, sense and vision in order to arrive at higher spiritual experience.

On the contrary, the "dark night of sense" which sets the house of flesh

at rest is at best a serious beginning. The true dark night is that of the

spirit, where the "subject" of all higher forms of vision and intelligence

is itself darkened and left in emptiness: not as a mirror, pure of all impressions,

but as a void without knowledge and without any natural capacity

to know the supernatural. It is an error to think that St. John of the

Cross teaches denial of the body and the senses as a way to reach a higher

and more secret mystical knowledge. On the contrary he teaches that the

light of God shines in an emptiness where there is no natural subject to

receive it. To this emptiness there is in reality no definite way. "To enter

upon the way is to leave the way", for the way itself is emptiness.

We are plagued today with the heritage of that Cartesian self-awareness,

which assumes that the empirical ego is the starting point of an infallible

intellectual progress to truth and spirit, more and more refined, abstract

and immaterial. Now this state of affairs can never be remedied by the

empirical ego merely going through gestures of purification and concentration,

suppressing thought, creating a void in itself, sinking into its

own essential purity, and so on. This is only another way of affirming

itself as an independent, autonomous possessor now of thought, now of

[8] Essays in Zen, Series III, p. 42. (p. 41).

[9] Ibid., p. 30.

non-thought, now of science, now of contemplation; now of ideas, now

of emptiness. The "emptiness" which the empirical ego strives to produce

in itself by "wiping the mirror" clean of all thoughts is then nothing

but a trick. At best it is bogus mysticism, and at worst, schizophrenia.

In any case it is pure illusion, and it makes true enlightenment impossible.

This is precisely what Zaehner stigmatizes as "individualism" and "passive

mysticism" in its most refined and dangerous sense.

As Hui Neng saw, it really makes no difference whatever if external

objects are present in the "mirror" or consciousness. There is no need to

exclude or suppress them. Enlightenment does not consist in being

without them. True emptiness in the realization or the underlying Prajna

wisdom of the Unconscious is attained when the light of Prajna (the

Greek Fathers would say of the "Logos", Zaehner would say "Spirit"

or Pneuma), breaks through our empirical consciousness, and floods with

its intelligibility not only our whole being but also all the things that we

see and know around us. We are thus transformed in the Prajna light, we

"become" that light which in fact we "are". We see the light in everything.

In such a situation, the presence of external objects and concepts in our

mind is irrelevant, for our knowledge of them is no longer obtained by

thinking about them as objects. We know them in a vastly different way,

as we know ourselves not in ourselves, not in our own mind, but in

Prajna, or as a Christian would say, in God.

This state or "enlightenment", then, has nothing to do with the exclusion

of external or material reality, and when it denies the "existence" of the

empirical self and of external objects, this denial is not the denial of their

reality (which is neither affirmed nor denied) but of their relevance insofar

as they are isolated in their own forms. They have become irrelevant

because the subject-object relationship that existed when the empirical

self regarded them and cherished its thoughts about them, has now been

transcended in the "void". But this void is by no means a mere negation.

It would be more helpful for western minds to call it a pure affirmation

of the fullness of positive being, though Buddhists would prefer to adhere

to their principle, neither affirming nor negating. The void (or the Unconscious)

may be said to have two aspects. First, it simply is what it is.

Second, it is realized, that is, it is aware of itself and, to speak improperly,

this awareness (prajna) is "in us", or better, we are "in it". Here of course

the mirror of "mind" is not our mind but the void itself, the Unconscious

as manifest and conscious in us. Hui Neng describes it in the following

terms:

When the light or Prajna penetrates the ground nature of consciousness

[in this translation Suzuki is obviously thinking of Eckhart] it illuminates

inside and outside: everything grows transparent and one recognizes

one's inmost mind. To recognize the inmost mind is emancipation . . .

this means the realization of the Unconscious (wu nien). What is the

unconscious? It is to see things as they are and not to become attached

to anything . . . To be unconscious means to be innocent of the workings

of a relative (empirical) mind . . . When there is no abiding of thought

anywhere on anything - this is being unbound. This not abiding anywhere

is the root of our life.[10]

Prajna therefore is not attained when one reaches a deeper interior

center in one's self (Suzuki's translation, "one's inmost mind", might be

misleading here). It does not consist in "abiding" in a secret mystical

point in one's own being, but in abiding nowhere in particular, neither in

self or out of self. it does not consist in self-realization as an affirmation

of one's own limited being, or as fruition of one's inner spiritual essence,

but on the contrary it is liberated from any need of self-affirmation and

self-realization whatever. In a word, Prajna is not self-realization, but

realization pure and simple, beyond subject and object. In such realization,

evidently "emptiness" is no longer opposed to "fullness", but emptiness

and fullness are One. Zero equals infinity.[11]

Another Zen Master was asked how this enlightenment could be attained.

He answered: "Only by seeing into nothingness".

The disciple: "Nothingness: but is this not something to see? [i.e. docs

it not become an object - the empty mirror, unstained by "thought?"]

The Master: "Though there is the act of seeing, the object is not to be

designated as something

The disciple: "If this is not to be designated as "something" [object]

what is the seeing'?"

[10] Suzuki, Op, Cit., pp. 34, 35.

[11] Compare the doctrine of Nicholas uf Cusa : since the infinite is all, it has no opposite

and no contrary. It is at once the maximum and minimum, and is the perfect coincidence

of all contraries. Hence it explodes the Aristotelian principle of contradiction.

Nicholas of Cusa, like the Zen Masters, affirms and denies the same thing at the same

time, when speaking of the infinite. For him, admission of the coincidence of opposites

is the "starting point of the ascension to mystical theology". A remark of Gilson's

shows how perfectly Nicholas of Cusa agrees with Hui Neng. "Nicholas exhorted

his readers to enter the thickness of a reality whose very essence, since it is permeated

with the presence of the infinite [i.e., "the Unconscious"] is the coincidence of opposites".

History of Christian Philosophy in the Middle Ages, p, 536.

Master: "To see into where there is no something [object]; this is true

seeing, this is eternal seeing".[12]

Where there is a "something", a limited or defined object, there is less

than Act, therefore not "fullness". Once again, "emptiness" of all limited

forms is the fullness of the One: but the One must never be regarded as a

limited or isolated form. To avoid this misconception, the Zen Masters

speak always of emptiness.

It is impossible to get a real grasp of Zen if one does not understand

the distinction between the two concepts of "mind" propounded by the

Southern School of Hui Neng and the Northern School of Shen Hsiu.

This resolves itself into a real grasp of the difference between the two

verses ascribed (at least by posterity) to the two contestants for the title

of Sixth Patriarch; and this is a point where Fr. Dumoulin seems to be

open to criticism. But if he is deficient in his understanding of such a

crucial matter, his whole thesis about the mystical character of Zen will

tend to be weakened.

It seems to me that Fr. Dumoulin does, in fact, miss the point of Hui

Neng. And it is possible to surmise that he does so out of an unconscious

anxiety to bring Zen a little closer to conventional Western ideas of

contemplation, so that the Zen experience can be more clearly demon-

strated to be something akin to supernatural mysticism, that is, to an

"I-Thou" experience of God. This of course is a very difficult task,

because it seems to involve one, again, in the subject-object relationship

which is discarded by the Zen experience of void. But is it after all necessary

to cling to this one viewpoint? Is Martin Buber's formula absolutely the

only one that validly describes true mystical experience? Is a personal

encounter with a personal God limited to an experience of God as "object"

of knowledge and love on the part of a clearly defined, individual and

empirical subject? Or does not the empirical self vanish in certain forms

of Christian mysticism? It is my opinion that even the contemplation of

the void as described by Hui Neng has definite affinities with well-known

records of Christian mystic experience, but space does not permit us to

quote texts here. Here is how Fr. Dumoulin describes the "void" and

"unconsciousness" of Hui Neng:

The resolving of all opposites in the Void is the basic metaphysical

doctrine of the Diamond Sutra on which Hui Neng founds his teachings.

[12] Suzuki, Op. Cit., p. 38.

The absence of thoughts which is achieved in the practice of contemplation

by the suppression of all concepts is regarded as the primal state of mind

whose mirror light clings to no concept . . . The absence of all concepts

indicates that the mind adheres to no object but rather engages in pure

mirror activity. This absolute knowing constitutes the unlimited activity

of inexhaustible motion in the motionlessness of the mind . . . All objects

are cleared away by contemplation of the void, and personal consciousness

is overcome.[13]

There are, it is true, elements superficially resembling Hui Neng in

these sentences, but in their substance, especially in the passages I have

italicized, they are in reality a contradiction of Hui Neng. They are much

rather an expression of the mirror wiping Zen of Shen-hsui, The "absence

of thoughts is achieved" - by whom? What achievement? All concepts

are suppressed - in what? By whom? The mind engages in pure mirror-like

activity. What mind? What activity? Who? This is directly opposed

to Hui Neng's insistence that there is no special psychological state to be

"achieved", that the suppression of thoughts is irrelevant, and that the

mind is not to be isolated in itself and in its own purity.

The language which is used here does not express the Zen of Hui Neng:

these are concepts that are determined by purely western preconceptions

about the mind and about contemplation. What is talked about is indeed

"the Void", but in reality the language used can apply to the empirical

ego. Hence the description is purely and simply of the empirical ego

polishing the mirror of its own self-consciousness, and attempting, by

scraping the tile, to become a Buddha. This is exactly what Hui Neng

refuses to countenance.

In view of these limitations, when Fr. Dumoulin goes on to attribute

to Hui Neng the idea that "all distinctions are nullified, and there is no

difference between good and evil",[14] we find ourselves plunged once again

into serious misconceptions about Zen. I admit, Hui Neng says this,

but it can only be true for him when the empirical ego has vanished. For

the empirical self there is, and must be, good and evil. Only in Prajna

(we would say in God) is there no more good and evil. It is small wonder

that Fr. Dumoulin somewhere says that for Hui Neng the contemplation

of one's own nature is a "promethean exploit". Obviously, if it is the

work of the empirical ego, it can hardly be anything else.

[13] Dumoulin, History, pp. 91-92 emphasis added.

[14] Ibid.

There is of course every reason to understand why Fr. Dumoulin is

un-sympathetic to Hui Neng and indeed profoundly suspicious of him.

While Suzuki, for instance, is temperamentally disposed to defend Hui

Neng and the Rinzai school of Zen, Fr. Dumoulin is naturally inclined

toward the other celebrated Japanese Zen school: Soto. As a matter of

fact, one of the best chapters of his book is the one devoted to Dogen,

the founder of that school. But Dogen is a defender of the meditative

zazen type of Zen and he is closer to Shen-hsui than to Hui Neng.

Fr. Dumoulin's interpretation of Hui Neng certainly falls short of the

highest and most original Zen insight, and therefore it presents Zen,

once again, as a form of quietism, a passive, "mirror-wiping" technique

of self-emptying by sitting in long periods of meditation. Such meditation

attempts to "purify" the mind of all the "polluted imagery" and conceptual

baggage which it has acquired by its unfortunate association with the body.

This equates Zen with the conventional methods of Yoga and contemplation

common both in east and west, which all presuppose the separation

of spirit and matter, rather than that "recapitulation" of all things in

Christ proclaimed by St. Paul. Hence it is natural that someone like

Professor Zaehner, for all his knowledge of Indian and lranian mysticism,

can finally end by lumping all these forms of contemplation together

as if they were all equally negative, passive; quietistic or spiritualistic,

and as if they had nothing whatever to offer in an age that has discovered

the urgent need to heal the forced separation of matter and spirit by

"convergence" and unity.

Of course I am not attempting to affirm that the "emptiness" of Hui

Neng has social implications that would bring him into harmony with

Marx, Engels, and Teilhard de Chardin. On the other hand there is nothing

in him that opposes social action or human progress because his is not a

mere technique of withdrawal, negation and passivity. A well-ordered

concern with social affairs need not conflict with this kind of Zen wisdom.

A genuine understanding of Hui Neng will show that at least some of

the Zen masters were fully aware of the basic, indissoluble unity in man,

and fought against every form of mystical illusion that would break that

unity down in order to achieve an abstract or gnostic reorganization of

spirit on an immaterial plane. I do not know if the insight of Hui Neng

can influence our thinking on a large scale today; but it remains permanently

valuable for those who can see what he is saying, not only because

it is courageous, original and brilliant, but because it apprehends the

unity of Being in a simple, concrete intuition which is completely free,

not only from all forms of dualism, but also from pantheistic monism as

well. The simplicity of this Zen insight which is innocent of all theorizing,

and neither affirms nor denies anything, is outside all philosophical and

religious categories.

Thomas James Merton

1915–1968