SZÓTÓ ZEN SŌTŌ ZEN

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

Etiquette - Manners in the Zendô

Soto Zen Etiquette in Manga-style

Bonze Days in Manga-style

Illustrations of life in a Rinzai Zen monastery by Satō Zenchū (1883–1935)

雲水日記 Unsui nikki by 佐藤義英 Satō Giei (1921-1967), 東福寺 Tōfuku-ji, Kyoto, 1939/1940 > b/w

PDF: Unsui: A Diary of Zen Monastic Life

Drawings by Giei Satô, text by Eshin Nishimura, edited and with introduction by Bardwell L Smith

University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1973PDF: Journal d'un apprenti moine zen

de Giei Satô, traduit par Roger Mennesson

Ed. Philippe Picquier, Arles, 2012

Hanley, Theresa. Inquiry Report on Zen Buddhist Funeral Rituals

Brands of Zen: Kitō jiin in Contemporary Japanese Sōtō Zen Buddhism

Dissertation by Tim Graf

Universität Heidelberg, 2017

Manners in the Zendô

This is a brief guide to etiquette in the zendô. Through experience we develop familiarity with the forms of practice. Don't get caught up in worrying about what happens next or what you should do. When in doubt, go with the flow of other students

On entering the zendô have hands in gassho, step in left foot first, bow into the zendô, and with hands still in gasshô, proceed to a seat. Turn facing into the room, bow, remove shoes (placing them on the floor directly under the tan) and sit. When entering the zendo as part of a group, such as returning from kinhin, the Jikijitsu bows for the group.

ZAZEN starts on the striking of three bells. Refrain from voluntary movement or sounds during zazen. Zazen ends with a single bell. Kinhin or rest kinhin is signaled by striking the wooden clappers either once or twice.

Kinhin is the interval between zazen periods. At the sound of a single clapper strike, bow, put on your shoes, and stand with hands in gassho. At the sound of the next clapper strike, bow, and with hands in sassho leave the zendô. Walk as a group and in step. At the sound of the single clapper strike, place hands in gasshô. With hands in gasshô, enter the zendô without bowing, proceed to your seat, and at the sound of the single bell, bow and sit. During walking kinhin students may use the rest rooms or leave the Zen center. On leaving the kinhin line, step out of line and bow towards the person behind you. On returning to the kinhin line, enter at your "place" in the line, bowing towards the person you step in front of as you re-enter the line.

Rest Kinhin is signaled by two strikes of the clapper. Rest kinhin occurs as a brief interlude to formal zazen and as an alternative to walking kinhin.

A rest kinhin preparatory to zazen or chanting may be used to adjust posture. During a rest kinhin between periods, continue sitting in zazen posture, stand with hands in sassho, or sit on the edge of the tan, hands forming a mudra.

Rest kinhin ends with a single clap. If standing or sitting on the edge of the tan, stand with hands in gasshô at the single strike of the clapper, bow at the single bell, and be seated. If seated in zazen posture, no motion is required.

Chanting in the mornings starts with the striking of the large gong, during which the sutra book is retrieved from under the zabutan. The regular morning chanting begins with the Heart Sutra and goes to the end of the sutra book. For closing services in the evenings, retrieve the sutra book when the Jikijitsu begins striking the small bell after offering incense. Only the Kozen Daito is chanted in the evenings.

Great Bows occur after chanting. On the striking of one bell followed by two bells in quick succession, bow with hands in gasshô. As the roll-down sound of the bell progresses, place a support cushion on the floor in front of you and stand in gasshô. After the roll-down, at the striking of the single bell, perform a full prostration, forehead touching the support cushion on the floor, and hands, palms upturned, raised above the ears, parallel to the ground. Hands are held elevated while the bell sound reverberates. At the silencing of the bell, stand quickly, hands in gasshô. Two bells signal the third and last prostration. Upon standing, retrieve the support cushion, arrange the seating area, and stand in gasshô as the bell is slowly struck three times. Bow with the group on the third bell.

Tea (sarei) is served morning and evening. At morning service, when the bell is struck once in response to two clapper strikes, bow and retrieve a tea cup and napkin, placing the napkin on the front of the zabutan. For the evening period, retrieve a tea cup and napkin when the Jikijitsu announces “sarei.” Hold the tea cup in one hand and signal by raising the other hand when sufficient tea has been poured. Take some tea at the first serving; on the second serving tea may be declined by bowing. Do not put the cup and napkin away until the second serving has been offered.

On leaving the zendô at the end of a sitting, neaten your zabutan and fluff the zafu. Bow into the room and leave directly, hands in sassho. Leave no traces. The sitting area should be ready for the next student. If tea was served, take your tea cup and napkin to the shoji room to be washed.

On entering or leaving during rest kinhins, or before a zazen period starts, bow to the shoji.

Questions? Feel free to ask any of the zendo officers or more experienced students about etiquette and practice before or after formal practice periods. During formal practice, you can consult the Shoji during kinhin periods.

Kinhin

http://www.meditationpathways.com/kinhin.htm

Going straight like the vertical thread in a piece of cloth

Reverend Issho Fujita, was born April 18, 1954 in Niihama City, Ehima, Japan. After becoming inspired by the practice of Shikantaza, in the tradition of Kodo Sawaki and Kosho Uchiyama, he left his graduate school studies in child psychology, and entered Antaiji Temple, where at age 29, he became ordained into zen priesthood. Eleven years ago he came to America, to assume responsibilities at Valley Zendo , in Charlemont Massachusetts, where he resides, with his wife, Naomi, and their two daughters, Saki and Masumi. In the following pictorial essay, Reverend Fujita explains some of the important aspects of walking meditation in relation to his sitting practice of Shikantaza.

According to the Soto tradition, we do Kinhin practice between sitting sessions as taught by Zen master Dogen, as he learned from his Chinese teacher Ju-Ching. "Ju-Ching often walked back and forth between the east and the west in the Ta-kuang-ming-tsang Hall to demonstrate this to Dogen." (Hokyo-ki annotated translation) It's always done as a continuation of sitting meditation. It gives you a way to refresh the mind and body, without interrupting the stillness of sitting practice. We sit for fifty minutes, then do Kinhin for ten minutes-sitting walking, sitting. People who practice this, believe that the Buddha walked this way. In some of the scriptures there's a description of the Buddha walking slowly, and mindfully, in the woods after sitting. What we cultivate in sitting, we apply in walking, through motion. The sitting meditation continues, in another form. Sometimes it's said that zazen is walking. We can also apply this to more complicated practices such as cooking, sweeping, or cleaning. Whatever it is that we are doing, it's done with the quality of zazen. "Just" (Shikan) is a key word, as in Shikantaza, we "'just sit", in Kinhin we "'just walk." Being one with what we are doing, we walk for the sake of walking. We don't focus on any particular object.

The walking includes many things, such as the sensation of your feet touching the floor, spatial orientation, along with awareness of your posture. We cannot sit forever. It's a bridge between sitting still, and moving in daily activity, and helps bring meditation into everyday life. Kinhin looks like it's between walking, and standing still. We walk very, very slow, within the speed of the breath. In breath, out breath. We listen to the breathing, and move the body according to this rhythm, breathing naturally.

Ju-ching taught with compassion: when you get up from the sitting posture and walk, you must practice the method of one breath per half a step. This means: as you move your foot, let it not exceed half a step, and be sure to pace yourself to the length of one breath. (Hokyo-ki annotated)

Ju-Ching said: 'If you wish to rise from the sitting posture and walk (in meditation) do not walk in circles, but in a straight line. If you wish to turn around after twenty or thirty steps make sure to turn right not left. When you move your feet, move the right foot first, then the left.' (Hokyo-ki annotated translation)

The hand position has a similar value as in sitting. You need to remain alert so you can maintain this form with the hands. The left hand is a soft fist with the right hand open on top. When sitting, the left is on top of the right, the as you come up, you turn over with the hands up, softly your chest. Some people have a small space, but it's very close to the body. So you don't have to change the relation between your right and left hand. As in sitting the thumbs are very softly touching. The eye position is also similar as when sitting, with the eye half open and looking down, at a forty-five degree angle. The upright position is key for both sitting and walking. The eyes are with the shoulders, and the nose with the navel. The lower body slowly moves forward.

As in sitting, when you walk there is no boundary. You open up, and are not trapped in your own body or agenda. You are walking together with the air, the floor, the room, and the whole world. As you walk you are naturally discovering this. It is not a result of your effort, but a natural bi- product of just walking. It's not something you try to create or manufacture, it's a gift from the Dharma. If it's to have meaning, it needs to be a gift from the practice, rather than trying to manufacture it. According to Dogen when people sit everybody sits, when people do Kinhin, everybody does Kinhin.

When arising from the cushion you bow twice, turning clockwise, to the right, with the right shoulder toward the center of the room. It's a ninety degree turn from the wall position. We make the hand position, take a couple of breaths, and then start with one breath, with one step, because the breath is slow. If you are standing still, your breath is relaxed and slow. We breathe and move as if the air is reaching the soles of our feet. The body is empty, like bamboo. We walk slow with grace and a dignity. Lifting the foot slightly, we touch the heel first, and then shift the weight to the tip of the foot while breathing out. The foot gradually touches the floor, and then pushes into the floor firmly. For a short moment you are standing still, because the out breath is continuous for a short while. When the inhale begins, you then move the other foot. With ringing of the bell, the feet are brought to a parallel position, we then bow. We keep walking back to the cushion, bow twice, and sit. This bow is known as gassho.

*

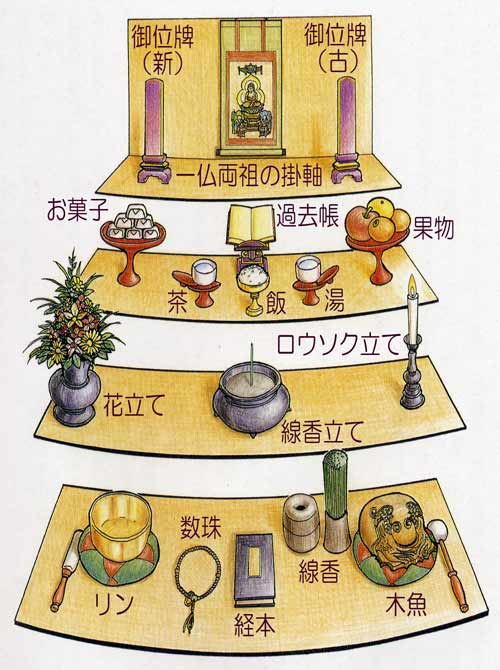

Butsudan お仏壇のおまつりの仕方