SZÓTÓ ZEN SŌTŌ ZEN

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

Sōtō Zen Etiquette Manga-style

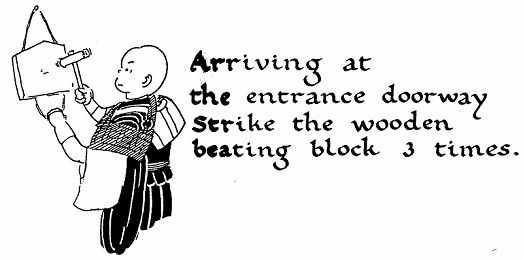

The following are copies of a manga style unsui manual from Hosshinji. One of the Japanese monks did these illustrations. Like all Japanese manga, you read them from the top right to the bottom left. First, when you arrive at the monastery entrance, you hit the wooden board ("moppan").

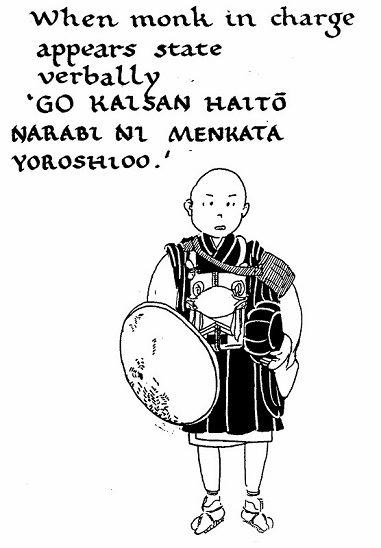

Interesting that as often in Japan, you do not state your real intention up front, but attach it to something else, which turns out completely irrelevant to the real issue. What the monk says is literally: "I would like to pay respects to the founder of the monastery, and also, please give me permission to train at the seminary"

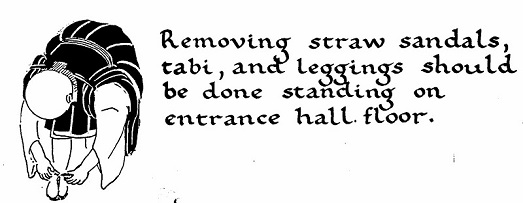

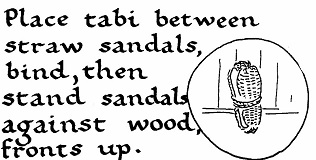

What follows depends a lot on the monastery and seniour monks you are dealing with. In Eiheiji, they might let you wait in the snow the whole day. In Hosshinji, it was not so bad. Eventually, they ask you to enter. as anywhere in Japan, before you enetr you have to take off your foot wear:

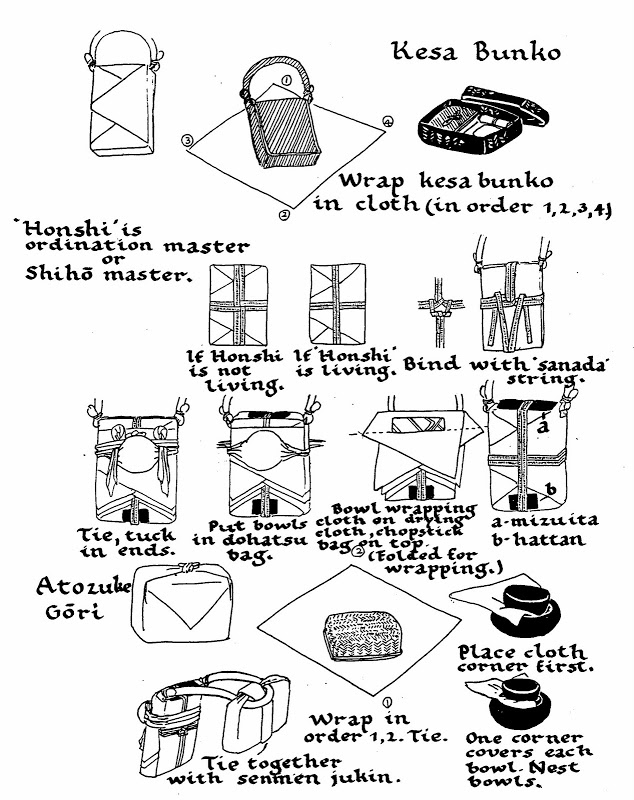

You are still not officially accepted into the monastery of course. Usually you are heading to the tanga-ryô for a week or so, where you practice either solitarily or with the other new comers that arrived during the same week. The following picture describes how you pack the kesa-bunko that travelling monks used to transport their robes and bowls in. It is not used in Japan anymore, except on the occasion of a monk formally entering or leaving a seminary (read pictures from right to left):

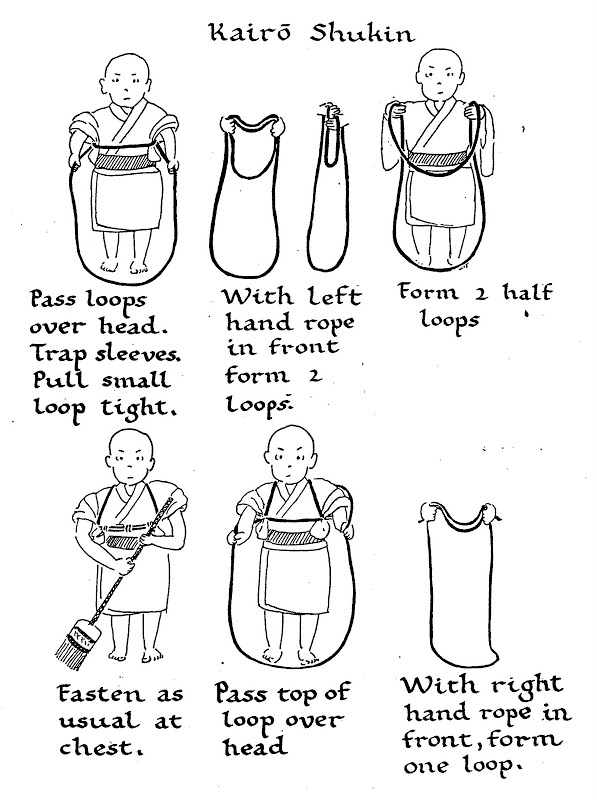

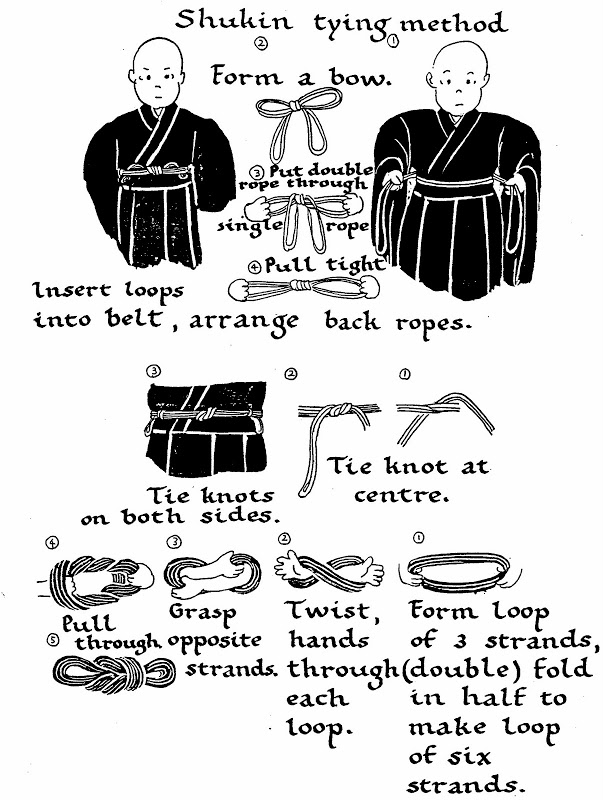

The next couple of days, you spend mostly doing zazen in your room, or being yelled at by the senior monks that want to test your determination. You also take part in the temple cleaning in the morning, but during this test period you do not wear your work clothes (samu-e) as would be usual, but rather tie up you kimono with the shukin-belt. This is done only during the tanga-ryô period now, but I guess they did temple work (samu) in this fashion as well, before the samu-e where invented (they are not so old, that is why they do not have them in China or Korea).

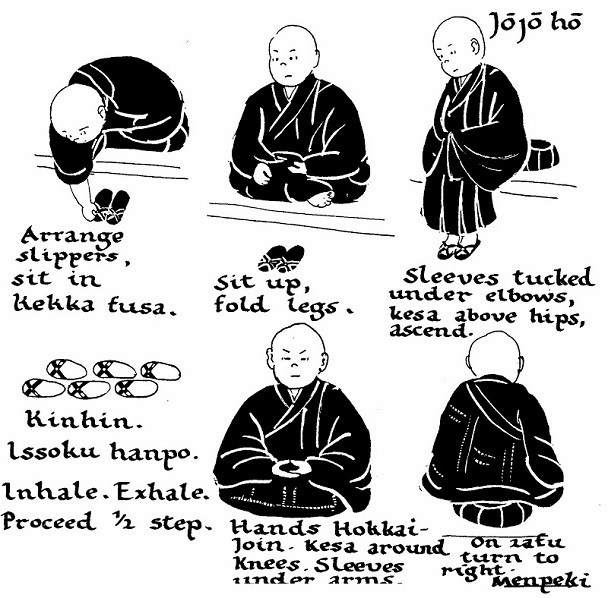

After a week or so, you will hopefully be accepted and join the senior monks in the meditaion hall (where you also sleep). This is how you get up to the platform where a plate with your name on it hangs, and how to do kinhin (walking meditation):

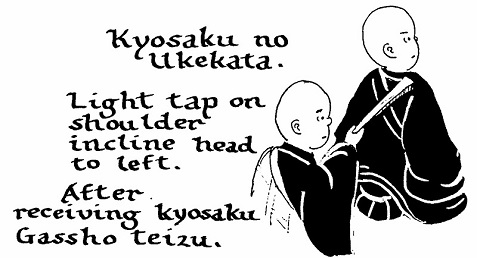

Sooner or later, one of the senior monks will come on patrol with the wake up stick:

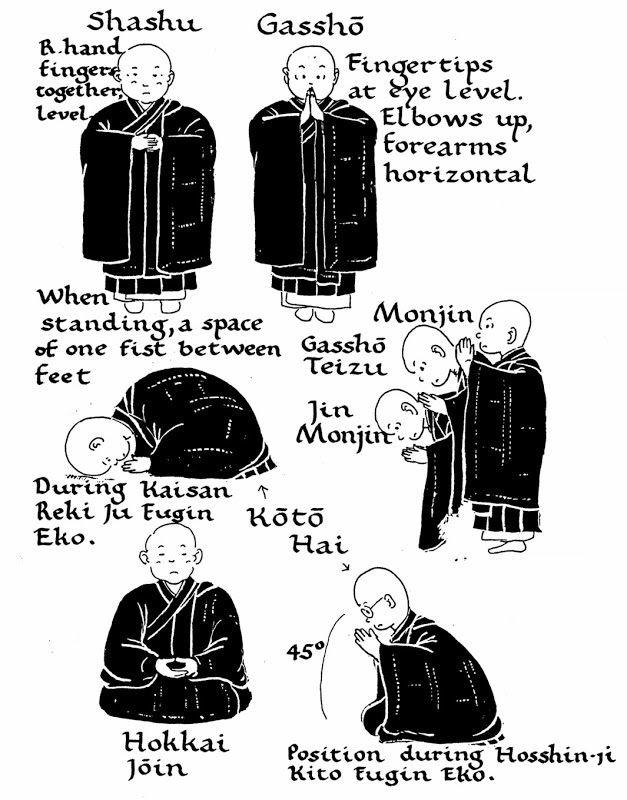

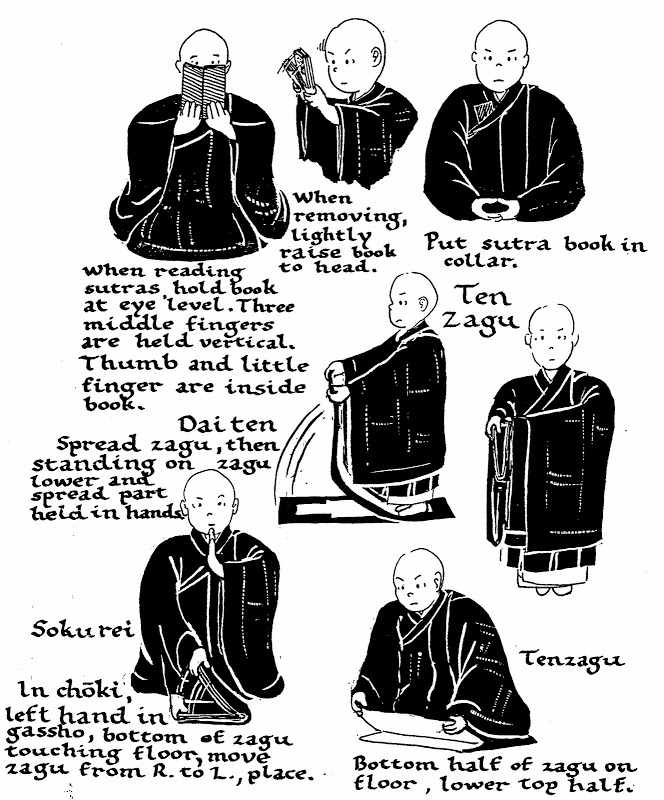

Of course, time in the monastery will not only be spent in zazen, but also bowing and prostrating:

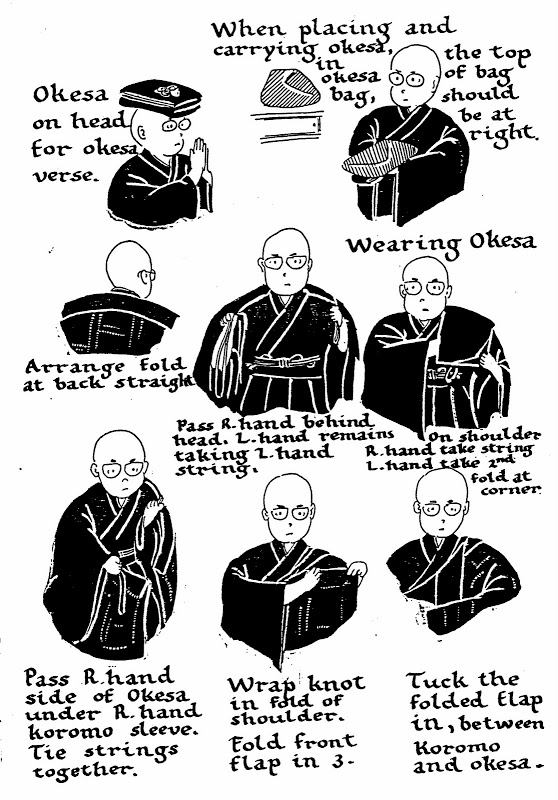

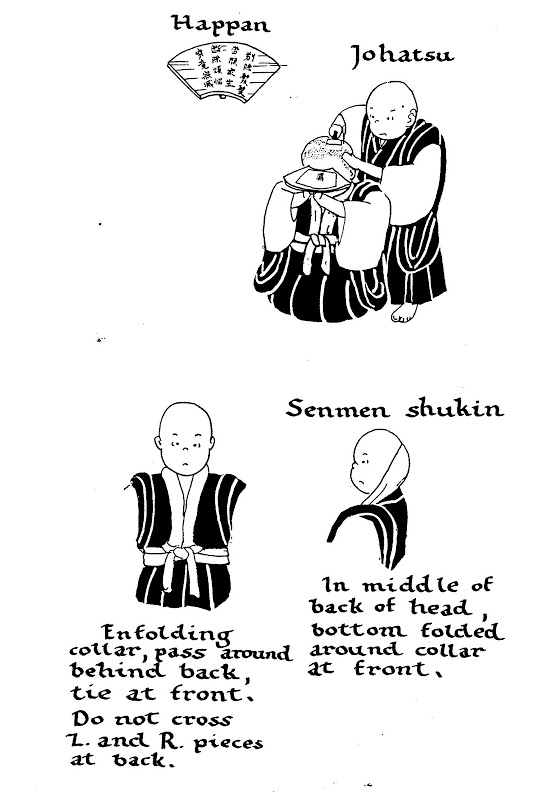

How do you put on those robes in the first place? Hard to describe in words, not so easy with pictures either, still here is the attempt to show you how to put on the shukin-belt and the o-kesa.

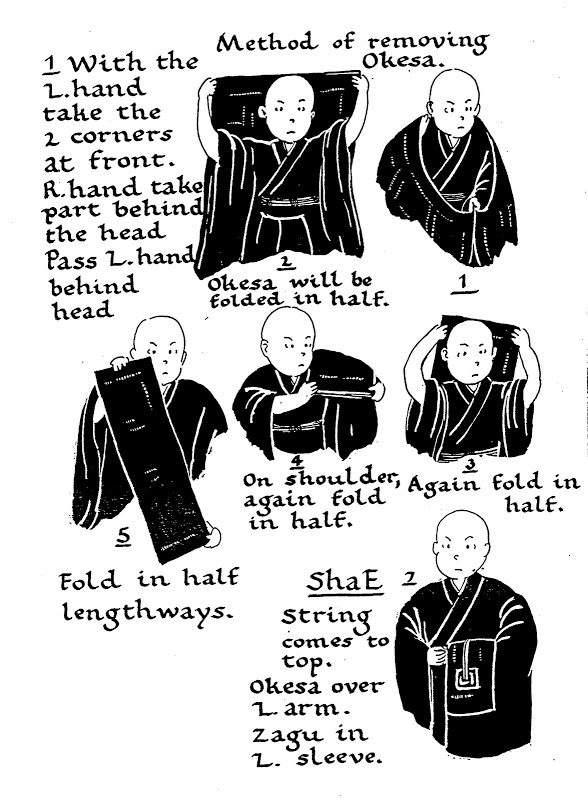

Now you also want to know how to take them off again. ShaE is the way you carry the kesa when you are not wearing it:

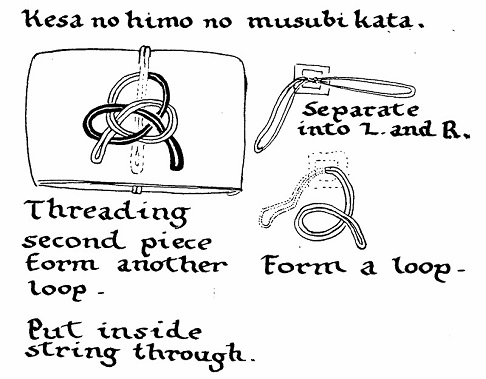

The following does not work for the so-called nyohô-e, the traditional hand sewn o-kesa that is worn in the Sawaki traditon. If you have one of the more wide spread, standard Soto kesas, you tie up the ends:

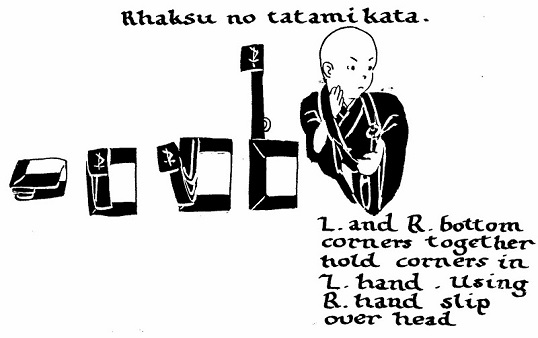

A little less complicated than the o-kesa is taking off the bib-style mini-kesa, called rakusu (not "rhaksu"!):

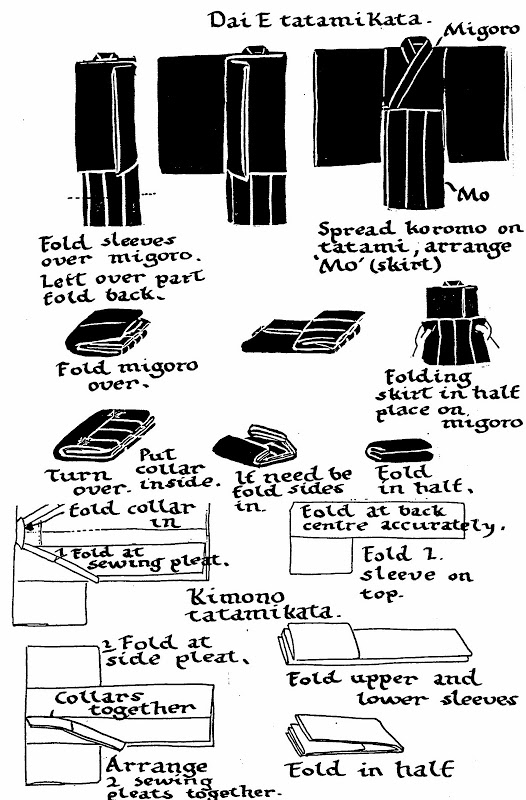

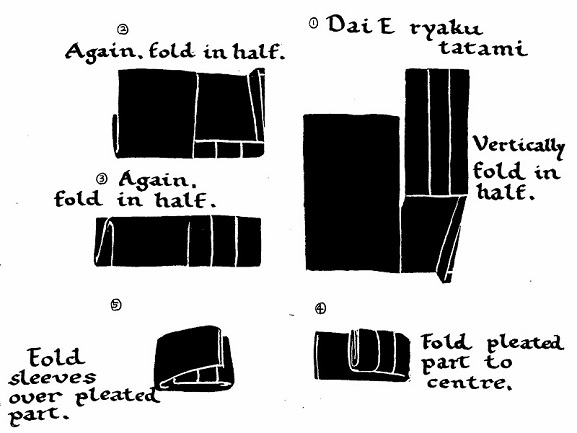

Next, how to fold the big black robe (koromo, also called dai-e) and the kimono when you store it away:

When you are in a hurry, here is an easier way to fold the dai-e:

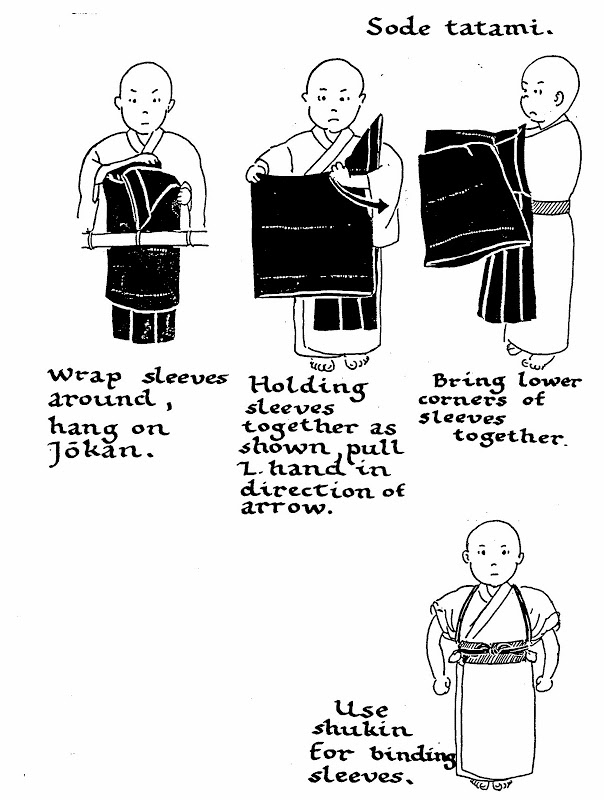

And what do you do if you want to go to the toilet during kinhin? First you take off the o-kesa, hang it on a bamboo called jôkan in front of the toilet area, next comes the robe:

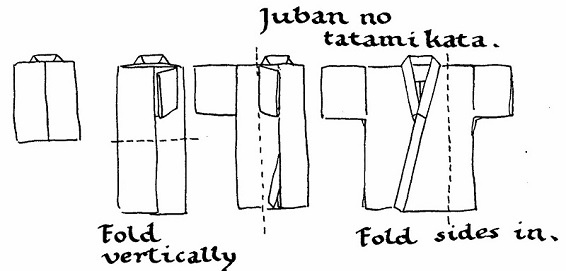

Below the kesa, dai-e and kimono you wear a traditional Japanese under garment called juban. If you can fold gthe other stuff, this one should pose no problems:

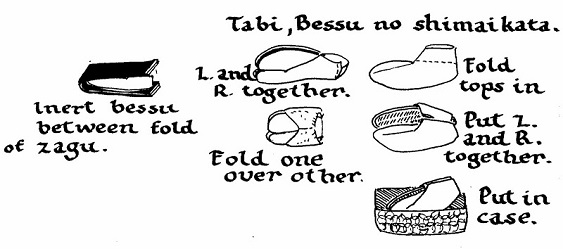

And don't forget the tabi socks, bessu and zagu:

On each day that ends with a "4" or "9" (the so called "shi-ku-nichi"), i.e. every five days, monks shave each other's heads. For this, you have to roll up your robe's sleeves.

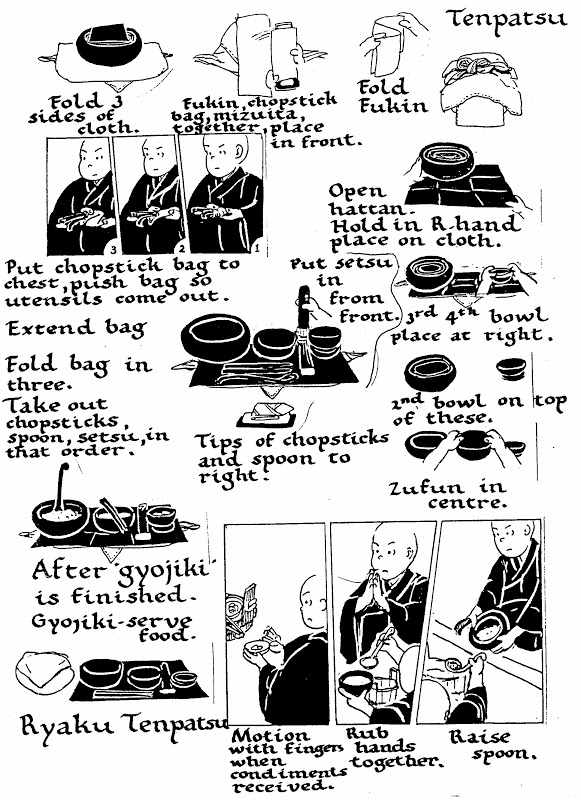

This last illustration might be intersting for lay people as well, as the way to eat with the ôyrôki-bowls (called tenpatsu) is practiced in most Japanese monasteries, and also many centres in the West, also by lay people. in Antaiji, we practice the "Ryaku Tenpatsu" style you can see in the last (bottom left) picture, kneeling in front of low tables. That is also the way we ate most of the time in Hosshinji, the rest of the picture applies only during sesshin at Hossinji (at Antaiji, we eat Ryaku Tenpatsu-style during sesshin as well):

Source: https://web.archive.org/web/20120126051644/http://antaiji.dogen-zen.de/eng/201201.shtml