ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

荷澤神會 Heze Shenhui (670-762)

![]()

Shenhui in frame 50 of the 1170s 梵像卷 Fanxiang juan (Roll of Buddhist Images)

The Collection of National Palace Museum, Taipei

神會和尚遺集 Shenhui heshang yi ji

(Rōmaji:) Kataku Jinne: Jinne oshō ishū

(Français:) Entretiens du maître de dhyâna Chen-houei du Ho-tsö

(Magyar:) Sen-huj hosang ji csi / Ho-cö Sen-huj csan mester beszélgetései

Tartalom |

Contents |

| Beszéd a hirtelen megvilágosodásról Fordította: Hadházi Zsolt |

Biography of the Chan Master Shi Shenhui Biography Ch'an (Zen) Buddhism in China: Its history and method The Development of Zen Buddhism in China The Sermon of Shen-hui The Recorded Conversations of Shen-hui Debates in China and Tibet by Gary L. Ray (2005) DOC: Shen-hui and the Teaching of Sudden Enlightenment in Early Ch'an Buddhism PDF: Zen evangelist: Shenhui, sudden enlightenment, and the southern school of Chan Buddhism PDF: New Japanese Studies in Early Ch’an History PDF: The Problem of Practice in Shen-hui’s Teaching of Sudden Enlightenment PDF: Southwestern Chan: Lineage in Texts and Art of the Dali Kingdom (937–1253) See more at: |

PDF: Southwestern Chan: Lineage in Texts and Art of the Dali Kingdom (937–1253)

by Megan Bryson

Pacific World: Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies, Third Series, Number 18, 2016

Special Issue: Essays in Honor of John McRae, pp. 67-96.

Shenhui, his master and his disciples (from the right to the left):

Frames 54 < 53 < 52 < 51 < 50 < 49

54. Faguang Heshang 法光和尚 < 53. the monk Chuntuo Dashi 純陁大師 < 52. the layman Xianzhe (Worthy) Mai Chuncuo 賢者買純嵯 < 51. Heshang (monk) Zhang Weizhong 和尚張惟忠, a monk from Chengdu whom Song records connected to both the famous Heze 菏澤 Shenhui and Jingzhong 淨眾 Shenhui (720–794) of Sichuan < 50. Heze Shenhui 荷澤神會 < 49. Dajian Huineng with Shenhui

These appear to be Buddhist figures from the Dali region who would have

lived during the Nanzhao kingdom, but the only information about them

comes from Ming sources. Except for frame 52, where the kneeling disciple

Chuntuo holds the dharma robe while Mai Chuncuo sits in a chair,

these images do not include the robe as a sign of transmission.

梵像卷 Fanxiang juan (Roll of Buddhist Images) of the 1170s

The Collection of National Palace Museum, Taipei

Heze Shenhui is the founder of the Hezezong (荷泽宗) branch of Zen, which was active until the end of the Tang dynasty. Hu Shi consider him as the real initiator of Zen to replace Huineng. Shen hui learned the five classics when he was young,end then became interested in the thinking of Laozi and Zhuangzi, at last he converted Buddhism. He was called Hezedashi (菏泽大师), and was the writer of Xianzongji (显宗记).

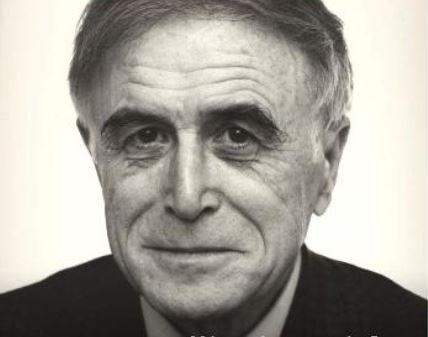

Jacques Gernet (1921-2018)

Jacques Gernet: Entretiens du maître de dhyâna Chen-houei du Ho-tsö (668-760), Hanoi, EFEO (Publications de l'école française d'Extrême-Orient, v. 31). 1949, [réimpr. 1974]. x, 126 p.

Jacques Gernet: Complément aux Entretiens du maître de dhyâna Chen-houei par Jacques Gernet, BEFEO, XLIV, 2. Hanoi, 1954. pp. 453-466.

http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/befeo_0336-1519_1951_num_44_2_5180

http://www.youscribe.com/catalogue/presse-et-revues/savoirs/complement-aux-entretiens-du-maitre-de-dhyana-chen-houei-668-760-957919

Jacques Gernet: "Biographie du Maître Chen-houei de Ho-tso," Journal Asiatique, 239 (1951), pp. 29-60.

Walter Liebenthal (1886-1982)

“The Sermon of Shen-hui,”

Asia Major, New Series, III (1953), part II, pp. 132-55.

https://www2.ihp.sinica.edu.tw/file/1672vpIQiDw.pdf

胡适 / 胡適 Hu Shi (1891-1962)

Shénhuì héshàng yíjí [Collection of Extant Works of Shenhui] 神會和尚遺集, ed. Hú Shì 胡適 (Shanghai: Shanghai yadong tushuguan, 1930)

Full title: Húshì jiào Dūnhuáng Táng xiěběn Shénhuì héshàng yíjí 胡適校敦煌唐寫本神會和尚遺集; in 1925 Húshì travelled to London and Paris and examined the Dūnhuáng manuscripts there; among the Pelliot manuscripts he discovered three new texts connected to the monk Shénhuì which he critically edited. Especially Húshì's introduction Hézé dà-shī Shénhuì zhuàn 荷澤大師神會傳 shed new light on the influence of this monk on the early Chán school. The book edits the following texts and text-fragments: (a) Shénhuì yǔ-lù dìyī cán-juàn 神會語錄第一殘卷 [First Text Fragment of the Recorded Sayings of Shénhuì; Pelliot 3047 (first part); the second part which consists of questions and answers is probably a record of the criticism on the Northern School of Chán which was initiated by Shénhuì during his stay at the Kāiyuán monastery in the beginning of the 8th century; (b) Shénhuì yǔ-lù dì-èr cán-juàn 神會語錄第二殘卷 (PELLIOT 3047); (c) Pútídámó nán-zōng dìng shì-fēi lùn bìng xù 菩提達摩南宗定是非論並序; (d) Shénhuì yǔ-lù dì-sān cán-juàn 神會語錄第三殘卷 (PELLIOT 3488); (e) Dùn-wù wú-shēng bō-rě sòng cán juàn (STEIN 468); appendix: Hézé Shénhuì dà-shī yǔ 荷澤神會大師語 (from the entry on Shénhuì in JDCDL); for a translation of the texts see Gernet 1949; there is a reprint of Húshì's book which was published in 1968 at Zhōngyāng yánjiū yuàn Húshì jìniàn guǎnkān 中央研究院胡適紀念館刊 under the same title (with the addition fù Húshì xiānshēng wǎnnián de yánjiū 附胡適先生晚年的研究); information based on ZENSEKI KAIDAI: 450, no. 29, 30

Hu Shih 胡適

神會和尚遺集 〈 附胡先生晚年的研究 〉 Shen-hui Ho-shang i-chi: fu Hu Hsien-sheng wan-nien te yen-chiu [The extant works of Master Shen-hui].

Ma Chün-wu, ed. Taipei: Hu Shih chi-nien kuan.Hu Shih. Shen-hui ho-shang i-chi, rev. and enlarged. Taipei: Hu Shih Chi-nien Kuan, 1970.

Hu Shih. "Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism in China: Its history and method"

Philosophy East and West, Vol. 3, No. 1 (April, 1953), pp. 3-24.

Hu Shih. "The Development of Zen Buddhism in China"

The Chinese Social and Political Science Review. January 1932. Vol. 15. No. 4. pp. 475–505.

Reprinted in: English Writings of Hu Shih, Chinese Philosophy and Intellectual History (Volume 2), Springer, 2013, pp. 103-121.There are two ways of telling a story. According to the traditional version, the origin and development of Zen Buddhism in China can be very easily and simply told. We are told that this school was founded by Bodhidharma who arrived at Canton in 520 or 526, and, having failed to persuade the Emperor Wu-ti of Liang to accept the esoteric way of thinking, went to North China where he founded the school of Ch'an or Zen ( 禅 ). Before his death, he appointed his pupil Hui-k'o ( 慧可 ) as his successor and gave him a robe and a bowl as insignia of apostolic succession. According to this tradition, Bodhidharma was the 28th Patriarch of the Buddhist Church in India and became the first Patriarch in China. Hui-k'o, the second Patriarch, was succeeded by Seng-ts'an ( 僧璨 ). After two more generations, two great disciples of the fifth Patriarch Hung-jen ( 弘忍 ), Shen-hsiu ( 神秀 ) and Hui-neng ( 慧能 ), differed in their interpretation of the doctrines of the school and a split issued. Shen-hsiu became the founder of the Northern or Orthodox School, while Hui-neng, an illiterate monk in Canton, claimed himself the successor to the Patriarchate of the school of Bodhidharma. This Southern School soon became very popular and Hui-neng has been recognized in history as the Sixth Patriarch from whose disciples have descended all the later schools of Zen Buddhism.

陳榮捷 Chan Wing-tsit (1901-1994)

'The Recorded Conversations of Shen-hui', translated by Chan, Wing-tsit.

A Source Book of Chinese Philosophy, New York, Columbia University Press, 1963, pp. 440-444.THE RECORDED CONVERSATIONS OF SHEN-HUI 60

The priest (Shen-hui) said, "There are mundane mysteries and also

supramundane mysteries. When a commoner suddenly becomes a sovereign,

for example, it is mundane mystery. If in the first stage of one's

spiritual progress which consists of ten beliefs," in one's initial resolve

to seek perfect wisdom, an instant of thought corresponds with truth,

one will immediately achieve Buddhahood. This is supramundane mystery.

It is in accord with principle. What is there to wonder about? This

clarifies the mystery of sudden enlightenment." (p. 100)The priest said, "The resolve [to seek perfect wisdom] may be sudden

or gradual, and delusion and enlightenment may be slow or rapid. Delusion

may continue for infinitely long periods, but enlightenment takes

but a moment. This principle is difficult to understand. Let me first give

an analogy and then clarify the principle, and then you may perhaps

understand through this example. Suppose there are individual

strands of light green silk each consisting of numerous threads. If they

are twisted to become a rope and are placed on a board, one cut with

a sharp sword will sever all threads at the same time. Although the

60 These are from the "Recorded Sayings" in the Shen-hui Ho-shang i-chi (Surviving

Works of Priest Shen-hui), ed. by Hu Shih, Shanghai, 1930. For a French

translation, see Bibliography.61 There are 52 grades, divided into six stages, toward Buddhahood. The first

stage consists of ten grades, namely, faith, unforgetfulness, serious effort, wisdom,

calmness, non-retrogression, protection of the Law, the mind to reflect the light

of the Buddha, discipline, and free will. Ordinarily one has to go through all six

stages before achieving Buddhahood.number of silk threads is large, it cannot stand the sword. It is the same

with one who resolves to seek perfect wisdom. If he meets a truly good

friend who by the use of [various]" convenient means shows him True

Thusness directly, and if he uses the diamond wisdom (which by its reality

overcomes all illusory knowledge) to cut off all affiictions in the

various stages, he will be completely enlightened, and will realize by

himself that the nature of dharmas is originally empty and void. As his

wisdom has become sharp and clear, he can penetrate everything and

everywhere without obstacle. At this moment of realization, all causes

[that give rise to attachment to external objects] will perish, and erroneous

thoughts as numerous as sand in the Ganges will suddenly vanish

altogether. Unlimited number of merits will be complete at the appropriate

time. Once the diamond wisdom issues forth, why can't [Buddhahood]

be achieved?" (pp. 120-121)Teacher of the Law Chih-te'" asked, "Zen Master, you teach living

beings to seek only sudden enlightenment. Why not follow the gradual

cultivation of Hinayana? One can never ascend a nine-story tower

without going up the steps gradually."Answer: "I am afraid the tower you talk about ascending is not a

nine-story tower but a square tomb consisting of a pile of earth. If it

is really a nine-story tower, it would mean the principle of sudden enlightenment.

If one directs one's thought to sudden enlightenment as if

one ascends a nine-story tower with the necessity of going through the

steps gradually, one is not aiming right but sets up the principle of

gradual enlightenment instead. Sudden enlightenment means satisfying

both principle (Ii) and wisdom. The principle of sudden enlightenment

means to understand without going through gradual steps, for understanding

is natural. Sudden enlightenment means that one's own mind

is empty and void from the very beginning. It means that the mind has

no attachment. It means to enlighten one's mind while leaving dharmas

as they are and to be absolutely empty in the mind. It means to understand

all dharmas. It means not to be attached to Emptiness when one

hears about it and at the same time not to be attached to the absence of

Emptiness. It means not to be attached to the self when one hears about

it and at the same time not to be attached to the absence of the self. It

means entering Nirvana without renouncing life and death. Therefore

the scripture says, '[Living beings] have spontaneous wisdom and wisdom

without teacher.t= He who issues from principle approaches the

Way rapidly, whereas he who cultivates externally approaches slowly.62 One word here is missing in the text.

63 Nothing is known of him.

64 Saddharmapundarika sutra (Scripture of the Lotus of the Good Law), ch. 3,

TSD, 9: 13. See Soothill, trans., The Lotus of the Wonderful Law, p. 93.People are surprised and skeptical when they hear that there is supramundane

mystery. There are sudden mysteries in the world. Do you

believe it?"Comment. Note the equal emphasis on wisdom and principle. The

rational element of principle, which occupies an important place

in Hua-yen and later in Neo-Confucianism, also has an important

role in Zen. Intuition does not preclude intellectual understanding.Question: "What do you mean?"

Answer: "For example, Duke Chou (d. 1094 B.C.)65 and Fu Yiieh'"

were originally a fisherman and a mason, respectively. 'The choice laid

in the minds of the rulers.':" Consequently, they rose as simple folks and

suddenly ascended to the position of a prime minister. Is this not a

wonderful thing in the mundane world? As to wonderful things in the

mundane world, when living beings whose minds are clearly full of greed,

attachment, and ignorance, meet a truly good friend and in one instant

of thought correspond [with truth], they will immediately achieve Buddhahood.

Is this not a wonderful thing in the mundane world?"Furthermore, [the scripturej'" says, 'All living beings achieve Buddhahood

as they see their own nature.' Also, Nagakanya, daughter of the

Dragon King, achieved Buddhahood at the very moment she resolved

to seek perfect wisdom." Again, in order to enable living beings to

penetrate the knowledge and perception of the Buddha but not to allow

sudden enlightenment, the Tathagata everywhere spoke of the Five

Vehicles (leading to their corresponding destinations for human beings,

deities, ordinary disciples, the self-enlightened ones, and bodhisattvas). 70

Now that the scriptures do not speak of the Five Vehicles but merely

talk about penetrating the knowledge and perception of the Buddha, in

the strict sense they only show the method of sudden enlightenment. It

is to harbor only one thought that corresponds with truth but surely not

to go through gradual steps. By corresponding is meant the understanding

of the absence of thought, the understanding of self-nature, and

being absolutely empty in the mind. Because the mind is absolutely

65 He assisted his brother, King Wu (r. 1121-1116 B.C.) in founding the Chou

dynasty and later became prime minister during the reign of King Wu's son. He

used to fish.66 Fu Yiieh was helping people build dykes when the sovereign Wu-ting (r.

1339-1281 B.C.) heard of him and later appointed him prime minister.67 This is a quotation from Analects, 20: 1.

68 Hu Shih (Shen-hui Ho-shang i-chi, p. 131) thinks that what follows is probably

a quotation from some scripture.69 Referring to the story in Saddharmapundarika sutra, ch. 12, TSD, 9:35. See

Soothill, p. 174.70 For the last three vehicles, see above, ch. 25, n.14. For bodhisattvas, see n.74.

empty, that is Tathagata Meditation. The Wei-mo-chieh [so-shuo] ching

says, "I contemplate my own body in the sense of real character. I contemplate

the Buddha in the same way. I see the Tathagata as neither

coming before, nor going afterward, and not remaining at present."?"

Because it does not remain (no attachment), it is Tathagata Meditation."

(pp. 130-132)Question: "Why is ignorance" the same as spontaneity (tzu-jan)?"

Answer: "Because ignorance and Buddha-nature come into existence

spontaneously. Ignorance had Buddha-nature as the basis and Buddhanature

has ignorance as the basis. Since one is basis for the other, when

one exists, the other exists also. With enlightenment, it is Buddha-nature.

Without enlightenment, it is ignorance. The Nieh-p'an ching (Nirvana

Scripture) says, 'It is like gold and mineral. They come into existence

at the same time. After a master founder has smelted and refined the

material, gold and the mineral will presently be differentiated. The more

refined, the purer the gold will become, and with further smelting, the

residual mineral will become dust."> The gold is analogous to Buddhanature,

whereas mineral is analogous to afHictions resulting from passions.

Afflictions and Buddha-nature exist simultaneously. If the

Buddhas, bodhisattvas.t- and truly good friends teach us so we may

resolve to cultivate perfect wisdom, we shall immediately achieve

emancipation. "Question: "If ignorance is spontaneity, is that not identical with the

spontaneity of heretics?"Answer: "It is identical with the spontaneity of the Taoists, but the

interpretations are different."Question: "How different?"

Answer: "In Buddhism both Buddha-nature and ignorance are spontaneous.

Why? Because all dharmas depend on the power of Buddhanature.

Therefore all dharmas belong to spontaneity. But in the spontaneity

of Taoism, 'Tao produced the One. The One produced the two.

The two produced the three. And the three produced the ten thousand

things.':" From the One down, all the rest are spontaneous. Because of

this the interpretations are different." (pp. 98-99)The assistant to the governor said, "All palace monks serving the

emperor speak of causation instead of spontaneity, whereas Taoist71 Wei-mo-chieh ching, sec. 12, TSD, 14:554.

72 Avidyii, particularly ignorance of facts and principles about dharmas.

73 Paraphrasing a passage in Nirvana siitra, ch. 26, TSD, 12:788.

74 Bodhisattvas are beings who are enlightened and are ready to become Buddhas

but because of their compassion they remain in the world to save all sentient

beings.75 Lao Tzu, ch. 42.

priests over the world only speak of spontaneity and do not speak of

causation."Answer: "It is due to their stupid mistake that monks set up causation

but not spontaneity, and it is due to their [stupid] mistake that Taoist

priests only set up spontaneity but not causation."The assistant to the governor asked: "We can understand the causation

of the monks, but what is their spontaneity? We can understand

the spontaneity of the Taoists, but what is their causation?"Answer: "The spontaneity of the monks is the self-nature of living

beings. Moreover, the scripture says, "Living beings [have] spontaneous

wisdom and wisdom without teacher.' This is called spontaneity. But in

the case of causation of the Taoists, Tao can produce the One, the One

can produce the two, the two can produce the three, and the three produce

all things. All are produced because of Tao. If there were no Tao,

nothing will be produced. Thus all things belong to causation." (pp.

143-144)

Gary L. Ray (2005)

The Northern School of Ch'an has made remarkable contributions to Buddhism from its origin in China to its spread to Japan and Central Asia. Although it is no longer a living tradition, it has made an immense contribution to Buddhist thought. This paper will briefly evaluate the origin of the Northern School in China, it's fight with the Southern School of Ch'an and its subsequent diffusion to the only other country in which it spread, Tibet. In Tibet we will briefly explore the Ch'an foundation prior to Northern Ch'an's arrival, Northern Ch'an's initial success, and Northern Ch'an's subsequent debate against the Indian Buddhists at bSam Yas. We will conclude with an evaluation of Northern Ch'an's contribution to Tibetan and Central Asian Buddhism.

A discussion of Northern Ch'an in Tibet would be impossible without an analysis of it's birth and development in China. The historical accounts of Ch'an in China demonstrate an unusual, and vitally important period of Buddhist philosophical maturation. This period resulted from a single idea from the 5th Chinese Ch'an Patriarch, Hung-jen, and was followed by what could be called the "Golden Age" of Ch'an development. To adequately discuss this we need to first explain how Hung-jen planted this seed, followed by his creative successors who expanded on his teachings. Then we need to discuss Shen-hui, the man who attempted to re-write history by fabricating stories and attempting to re-create the lineage itself. Finally, the aftermath of this attack and the ushering in of the new age of Ch'an will give us a greater perspective of how Northern Ch'an spread to Tibet and how it interacted with Tibetan Buddhism.

Ch'an developed slowly in its first 100 years in China. According to the official Ch'an lineage proposed by both the Northern and Southern schools: Bodhidharma taught Hui-k'o, Hui-k'o taught Seng-ts'ang and Seng-ts'ang taught Tao-hsin. Ch'an began to blossom creatively with the creation of a new style of teaching, created by Tao-hsin and carried on by his successors. This style of monastic Ch'an continues to the present day and is summed up in a list of rules known as the "pure regulations".

The "pure regulations" include four major points of practice that set the Ch'an community apart from other sects of Buddhism. These points include:

1. Scriptures were to be studied for their deeper spiritual meaning and not to be taken literally.

2. Ch'an was a spiritual practice for everyone.

3. Activity of any kind is meditation.

4. The community is independent -- creating its own resources, such as growing food.

Although some scholars debate whether the "pure regulations" originated in this period, these trends become very noticeable in the Ch'an stories and documents of the 6th and 7th century.

With Ch'an practice codified and carried out, and the emergence of the unified and stable T'ang dynasty, the next generations of students were given a platform on which to base their own ideas and teachings.

During the period of Tao-hsin's lifetime, the argument about sudden versus gradual enlightenment emerged. Although Tao-hsin was a proponent of gradual enlightenment, later generations continued to debate and new schools began to emerge based on doctrinal differences. Tao-hsin's position is summed up in his work Five Gates of Tao-hsin:

Let it be known: Buddha is the mind. Outside of the mind there is no Buddha. In short, this includes the following five things:

First: The ground of the mind is essentially one with the Buddha.

Second: The movement of the mind brings forth the treasure of the Dharma. The mind moves yet is ever quiet; it becomes turbid and yet remains such as it is.

Third: The mind is awake and never ceasing; the awakened mind is always present; the Dharma of awakened mind is without specific form.

Fourth: The body is always empty and quiet; both within and without, it is one and the same; the body is located in the Dharma world, yet is unfettered.

Fifth: Maintaining unity without going astray -- dwelling at once in movement and rest, one can see the Buddha nature clearly and enter the gate of samadhi.

Tao-hsin had two students of prominence: Fa-jung, who started what is now known as the Oxhead School and his successor Hung-jen.

Reports of Hung-jen, the fifth Chinese patriarch of Ch'an, show a history similar to the first four patriarchs. He left home early to become a monk, sat for long periods of time in meditation, discarded the sutras, realized enlightenment, and died at an advanced age after transmitting his teachings to a single successor.

Hung-jen marks the beginning of a new period of Ch'an, one characterized by strong master-disciple relationships and the expanding of spiritual practice beyond the Indian dhyana meditations. Hung-jen's spiritual practice was based on the Indian teaching of "gradual enlightenment," taught by his predecessor, Tao-hsin.

In this period of expansion of Ch'an practice, Hung-jen had as many as eleven students who he confirmed as mastering the teachings. Even more incredible than this, three of these students, Shen-hsiu, Hui-neng and Chih-hsien started their own schools based on variations of Hung-jen's teachings.

However, according to some Ch'an documents, the tradition of choosing a dharma heir continued, and Hung-jen's heir was a brilliant student named Fa-ju. However, Fa-ju was never included in the list of patriarchs, and at the time, a formal theory of a patriarchal lineage had not been established. Despite the succession of Fa-ju, the official heir to Hung-jen, according to the reliable Confucian scholar Ch'ang Yueh (667-730), is Shen- hsiu.

Before we look at Shen-hsiu, we should first look at the teacher who modern day Zen schools consider the sixth patriarch, Hui-neng. It is almost impossible to separate fact from fiction in the case of Hui-neng. Very little is known about him and nearly everything that is known comes from the Platform Sutra, a work that has been historically invalidated in recent years. We do know that Hui-neng was a younger contemporary to Shen-hsiu who led the typical mundane life of the Ch'an teacher as was discussed in the section on Hung-jen. As for Hui-neng's actual teachings, it is believed that they were no different from those of Shen-hsiu. In fact, as John McRae discovered in his research: "Ch'eng-kuan of the Hua-yen school, for example, was unable to see any significant difference between the teachings of Northern (Shen-hsiu's) and Southern (Hui-neng's) Ch'an." For example, the arguments over sudden versus gradual enlightenment were not Hui-neng's ideas, but are thought to have been created by one of Hui-neng's successors, Shen-hui, who will be discussed later.

Shen-hsiu was a very famous, highly educated teacher who attempted, like Hui-neng, to emulate the teachings of his late master. Shen-hsiu moved to Lo-yang, the capitol, in 701. He was accepted by the Emperor and Empress and even tailored his teachings to fit their needs. Shen-hsiu named his school the "East Mountain Teaching" in honor of his teacher Hung-jen, who taught on what was known as the East Mountain.

Up to this time, there was no reference to Northern or Southern schools and there was little or no conflict between methods of spiritual practice. This harmonious period between the time of Hung-jen and the deaths of Shen-hsiu and Hui-neng was the most creative period of Ch'an. However, this broad range of creativity inevitably resulted in conflict. As Heinrich Dumoulin points out: "The rich diversity of spiritual and intellectual elements that flowed together during this early period of Zen Buddhism were the harbinger of conflicts to appear in the following two or three generations." These conflicts began with the dubious claims of a monk named Shen-hui.

It is with Shen-hui and his successors that the colorful legends of Ch'an are created and developed. Before Shen-hui, there had been no Northern and Southern schools, gradual or sudden enlightenment, or even a conflict over lineage.

Shen-hui was a monk from Nan-yang who was determined to start his own school of Ch'an. He was born in 684 and in his early 20's studied with Hui-neng for about seven years, until Hui-neng's death in 713. In 732, Shen-hui held a conference in Hua-t'ai at the Ta-yun Temple. Here he planned his attack against the school of Shen-hsiu which included referring to Shen-hsiu's school as the Northern School, substituting Shen-hsiu for Hui-neng in the lineage, attacking Shen-hsiu's school on doctrinal points and once his attack was successful, declaring himself Hui-neng's successor.

Shen-hui's first line of attack was to create a broader difference between the schools of Hui-neng and Shen-hsiu. He did this by labeling Shen-hsiu's teachings "The Northern School", an attack that implied that Shen-hsiu's school was based on inferior teachings. Before this attack, as was mentioned earlier, Shen-hsiu referred to his school as "The East Mountain Teaching". Shen- hsiu's disciples later referred to their school as the "Southern School". This controversy over what is the Northern School and what is the Southern School is based both on geography (the "Northern School" was in the North) and the Chinese saying nan-tun pei-chien, meaning "suddenness of the South, gradualness of the North".

At the time in China, sudden enlightenment was considered the true teaching, and everyone identified their school with the practice of sudden enlightenment. Therefore, for Shen-hui to label Shen-hsiu's school "The Northern School" is an insult, implying that Shen-hsiu's school had inferior teachings. It would be similar to referring to Theravadan Buddhism as Hinayana. Heinrich Dumoulin writes: "According to the mainstream of later Zen, not only is sudden enlightenment incomparably superior to gradual enlightenment but it represents true Zen -- indeed, it is the very touchstone of authentic Zen." Of course, Shen Hui was not the first to argue over sudden versus gradual enlightenment. The fifth century teachers Hsieh Ling-yun (385-433), Seng-chao (374-414) and Tao-sheng (360-434) argued the same position, sometimes even using Taoist terminology and sources.

Shen-hui's substitution of Hui-neng as the real dharma heir involves a series of fabricated stories and teachings, including re-writing the lineage, and attempting to prove that Hung-jen intended for Hui-neng to be his successor.

Shen-hui first makes his point by saying that from the time of Bodhidharma, each master has given his robes to his successor. This line of succession continues all the way down to Hung-jen, who, according to Shen-hui, gave his robes to Hui-neng. Shen-hui wrote:

The robe is proof of the Dharma, and the Dharma is the

doctrine (confirmed by the possession) of the robe. Both

Dharma and robe are passed on through each other. There

is no other transmission. Without the robe, the Dharma

cannot be spread, and without the Dharma, the robe cannot

be obtained.Up to this point, the idea of a singular line of succession did not exist. In fact, when Shen-hui first told this story at the conference in Hua-t'ai, a representative from Shen-hsiu's lineage expressed puzzlement: "Confused, Ch'ung-yuan asked why there could be only one succession in each generation and whether the transmission of the Dharma was dependent on the transmission of the robe." As most lies tend to be, this one required additional supporting lies to make it stand on its own.

To legitimize these fabricated stories, Shen-hui created another story to complement them. In this story, Shen-hui creates a fictional dialogue that he uses in his teachings: "During his lifetime the Ch'an Master Shen-hsiu stated that the robe, symbolic of the Dharma, as transferred in the sixth generation, was at Shao- chou (near Hui-neng's temple)."

The most important fabricated story is probably the dialogue that takes place between Shen-hsiu and the Empress Wu. Philip Yampolsky describes this story from one of Shen-hui's texts called Nan-yang ho-shang wen-ta tsa-cheng i:

...when the Empress Wu invited Shen-hsiu to court, in the

year 700 or 701, this learned priest is alleged to have

said that in Shao-chou there was a great master [Hui-

neng], who had in secret inherited the Dharma of the

Fifth Patriarch.This story appears in almost every account of Ch'an in this period, including the Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch which will be discussed later.

Shen-hui then attacks "The Northern School" on doctrinal differences. Again, these attacks are fabricated. Shen-hui claims, as was mentioned in his labeling of Shen-hsiu's teachings, "the Northern School", that the Northern School practices gradual enlightenment. To back up this claim, he uses several fabricated dialogues similar to the ones he used in his robe claims. The most famous one is a dialogue between Master Yuan and Shen-hui about two of Shen-hsiu's successors, P'u-chi and Hsiang-mo:

The Master Yuan said: "P'u-chi chan shih of Sung-

yueh and Hsiang-mo of Tung-shan, these two priests of

great virtue, teach men to "concentrate the mind to enter

dhyana, to settle the mind to see purity, to stimulate

the mind to illuminate the external, to control the mind

to demonstrate the internal." On this they base their

teaching. Why, when you talk about Ch'an, don't you

teach men these things? What is sitting in meditation

(tso-ch'an)?"

The priest [Shen-hui] said: "If I taught people to

do these things, it would be a hindrance to attaining

enlightenment. The sitting (tso) I'm talking about means

not to give rise to thoughts. The meditation (ch'an) I'm

talking about is to see the original nature."This assault was Shen-hui's best shot against the Northern School. As Philip Yampolsky writes: "This attack was clever and effective; it may, however, have been quite unjustified." The Northern School also taught a form of sudden enlightenment. It's teachings were a sophisticated blend of practices derived from the Heart Sutra, the Lankavatara Sutra and the teachings of Hua-Yen. As Philip Yampolsky points out, it may have been closer to the teachings of Hung-jen than what Shen-hui promoted.

These descriptions of Shen-hui's attacks might sound as if there was a pitched battle between the Northern School and the Southern School. This was not the case. The "Northern School" as it is known today, ignored Shen-hui. There is not a single reference to Shen-hui in any Northern School text. As John McRae points out, "This failure to rebut Shen-hui's criticism is indicative of the fictitious nature of the entity `Northern School.'" Even if these attacks failed, however, it gave Shen- hui's school much needed attention. If it had not been for Shen- hui's attack, which drew attention to the school of Hui-neng, Hui- neng's school probably would have drifted into obscurity.

The down side to this for Shen-hui, was that his outspoken attacks attracted the attention of the imperial censor, Lu I, who was in favor of the Northern School. After an interview with Emperor Hsuan-tsung in 753, government officials were convinced that Shen-hui was a dangerous person, and therefore banished him from the capitol, Lo-yang.

Shen-hui was sent to various places during his exile, all of which were strongholds of Northern School teachings. He used this situation to his advantage, preaching and gaining increasing influence through his attacks. The government which banished Shen- hui was driven into exile in 756, when a rebel army took the capital cities in the An Lu-Shan Rebellion. Forced to defend themselves from this attack, the government began fund-raising efforts to support their armies, which included setting up ordination platforms to sell certificates of ordination. Shen-hui was brought back from exile to help in these efforts. In return for his service, the government promised him a position of authority and power. Heinrich Dumoulin responds to this by saying:

It seems ironic that one who so relentlessly criticized

masters of the Northern School for carelessly assuming

honorific titles and so betraying the true spirit of

Bodhidharma should spend his old age basking in the grace

of the powers that be.Shen Hui's school, fostered by the government, became the predominant school of Ch'an. By being so close to the imperial court, Northern Ch'an had become the "fashionable" religion of the day. However, it was during this period that China was invaded by Tibet and lost the city of Tun-Huang, creating a new interest in Ch'an from the Tibetan court. Northern Ch'an, although appearing on the scene in Tibet later than other schools, had a major influence in the Tibetan Buddhist panorama.

The first spread of Ch'an to Tibet came in 761 (dates vary) when the King K'ri-sron-lde-bstan sent a party to I-chou to receive Ch'an teachings. According to the chronicle, Statements of the Sba Family, the party received teachings and three Chinese texts from the Korean Ch'an master, Reverend Kim (Chin ho-shang), supposedly known as the most famous Ch'an master in China, who they met in Szechwan. Unfortunately Reverend Kim died later that same year. A second party was sent to China in 763, led by another member of the Sba family, Gsal-snan. There is debate about who Gsal-snan encountered when visiting I-chou. Some scholars thought that Gsal- snan met with Reverend Kim, but with strong evidence of Kim's death in 761, they now believe he met with Pao-t'ang Wu-chu (714-774), head of the Pao-t'ang Monastery, and a possible successor to Reverend Kim. Nevertheless, the teachings of Reverend Kim and Wu-chu laid the foundation for the Northern schools arrival.

While the Northern school was in the midst of decline following the attacks of Shen-hui, a Ch'an master named Hva-shang Mahayana took advantage of the political situation and travelled to Tibetan-occupied Tun-huang (781 or 787). Tun-huang was a significant hub in the spread of Buddhism between China, Tibet, Central Asia and India, and Tibet had recently wrestled it away from Chinese forces. For example, Buddhist scholar Luis Gomez calls Tun-huang "the crossroads of Buddhism on the Sino-Tibetan Central Asian frontier." For Hva-shang Mahayana, a new door had been opened for the spread of (Northern) Ch'an Buddhism.

Hva Shan was a third generation heir to Shen-hsiu, having been taught by several of Shen-hsiu's students. Although it is not clear what exactly Hva Shan Mahayana did in Tun-huang, we do know, according to the Tun-huang text Settling the Correct Principle of Suddenly Awakening to the Great Vehicle (Tun-wu ta-ch'eng cheng-li chueh), that the King K'ri-sron-lde-bstan invited him to Lhasa. This invitation was not an unusual occurrence, considering that Ch'an had been in Tibet for years before Hva Shan's arrival and that the king had been interested in learning about different Buddhist schools.

Mahayana gained a fairly large following of student in his short stay in Lhasa, mostly because of his close ties to Ch'an master Tao-t'ang who was already well established as a teacher. This however, was probably the final blow against the Indian Buddhists who, threatened by the Chinese Buddhist influence, brought political repercussions against the Chinese masters. Indian Buddhist teachers were concerned with the incredible popularity of Chinese Buddhism and its winning over of Tibetans.

Power, wealth and international relations were at stake in the vying for political patronage. According to R.A. Stein, "Its [Chinese Buddhism] popularity worried the Indian teachers, who had chiefly preached simple rules of moral conduct and the principle that good or bad actions are rewarded in future life." Similar to the position in China of Shen-hsiu silently being attacked with unfounded claims by Shen-hui, Hva Shan Mahayana probably did not recognize the Indian threat or the possible long-term repercussions of this brewing conflict.

Concerned with perpetuation of proper religious doctrine as well as other possible political motives. King K'ri-sron-lde-btsan was son of Sron-btsan-sgam-po who was the first patron of Buddhism in Tibet. Following in his fathers tradition of Buddhist patronage and the supervision of Tibet's "spiritual" welfare, he decided to stage a debate at the bSam yas Monastery to determine which doctrine should be officially patronized.

Far from being overly concerned with "correct" religious practice, it appears that the king had his own political agenda in mind. In his article on the debate, Joseph Roccasalvo quotes Paul Demieville's belief:

That a sinophobic party had existed at the court of

Tibet, and that it had backed the Buddhists of India,

less suspicious of political compromises, nothing [is]

more likely, especially since the rapport between China

and Tibet was particularly strained at the end of the

eighth century. Across all her history, since her

origins up to our present day, Tibet has been tossed

between China and India; its politics have always tended

to safeguard national independence by playing these

powers, one against the other...This belief that politics played an important role in the events surrounding the debate is a popular and sound theory, also held by Giuseppe Tucci. Tucci also brings the issue of growth of the monastic community as a reason for the debate. As the Buddhist community, grew, the government grew less powerful due to the increased economic power of the monasteries. The debate played the role of protecting the state and limiting the power and wealth of the Buddhist community by disqualifying the loser from royal patronage and huge donations.

The details of the actual debate is open for much scholarly analysis -- especially opinions regarding the number of debates as well as the content. Buddhist scholars such as Tucci question the idea that a debate took place, while others such as Tanaka and Robertson and Ueyama believes that multiple debates were held. The remaining scholars are placed somewhere in the middle, acknowledging the existence of the debate but accepting the predominant theory that only one debate took place. I tend to side with Tanaka and Robertson with the number of debates. The content and outcome of the debate(s) is more complicated.

Excluding the political motives for the debate, the main doctrinal conflict was between the gradual enlightenment position of the Indian school and the sudden enlightenment position of the Ch'an school. Hva Shan Mahayana took on the role of ston-mun-pa, or "representative" of the Ch'an school, while the fairly unknown Indian master, Kamalasila, represented the Indian school. It has also been noted that K'ri-sron-lde-btsan did not play a significant role in the debate, probably because of his lack of "doctrinal preparation."

The doctrines of sudden versus gradual enlightenment were not a new debate, as we have seen from the Northern Ch'an's experiences in China. Joseph Roccasalvo quotes Helmut Hoffman's analysis of the two opposing positions:

The most important matters of doctrine in which Hva-shang

differed from his Indian rival were (1) the attainment of

Buddhaship does not take place slowly as a result of a

protracted and onerous moral struggle for understanding,

but suddenly and intuitively -- an idea which is

characteristic of the Chinese Ch'an and of the Japanese

Zen sect which derives from it; (2) meritorious actions

whether of word or deed, and, indeed, any spiritual

striving, is evil; on the contrary one must relieve one's

mind of all deliberate thought and abandon oneself to

complete inactivity.Kamalasila's position was that enlightenment was a gradual process that required moral purification through proper practice. Enlightenment was not guaranteed to the individual in the present lifetime, but was to be continued throughout a series of many lifetimes until one was purified. This purification process was accomplished by the complicated practice of Yogacara meditation techniques. The idea that enlightenment could not only come in one lifetime, but came only after a practitioner could "abandon oneself to complete inactivity," was "heretical" to Indian teachers like Kamalasila. Jeffrey Broughton explains how the Indian school would have perceived the teachings of Northern Ch'an:

Under such conditions it is unlikely that the Indian

pandits would have had much patience for the ston mun's

"gazing-at-mind," a Ch'an meditation with antecedents in

the East Mountain Dharma Gate and their earliest Northern

Ch'an teachings, and "no-examining." For them, "no-

examining" only came after effortful examining or

analysis.The outcome of the debate is unclear. Chinese sources claim Mahayana the winner, while Tibetan sources claim Kamalasila as the victor. A Tibetan source cited by Tucci from rNying-ma rDzogs- chen literature also claim the Ch'an school the winner, however Tanaka and Robertson refute this source on the basis of its historical inauthenticity. Regardless of who won the debate, it is clear that Indian Buddhism became the predominant practice in Tibet following the councils.

The debate was characterized by prejudice and misunderstanding on both sides. In addition to the political barriers and concerns, there was also a significant language barrier. Neither side spoke each others language, and Tibetan was probably used as a middle ground in the debate. Both sides probably understood the other position from previous information gained from "hearsay," and as Jeffrey Broughton points out, "...even hearsay had to pass through a formidable language barrier." I would argue that although the Northern Ch'an school might not have had a firm grasp of specifics of Indian doctrine, it should have had a strong understanding of the gradual approach from having to defend itself from Southern School attacks in China.

The aftermath of the debate is as complicated as the debate itself. There were many bizarre stories surrounding the results of the debate. One interesting legend is that Ch'an practitioners, extremely upset at the defeat of Mahayana, "sent four Chinese thugs who disposed of the defenseless Kamalasila by `squeezing his kidneys.'" This idea that Ch'an was defeated in complete disgrace and forced to leave Tibet is more myth than reality. Hva Shan Mahayana was not devastated by his defeat as some Tibetan sources would have us believe, nor was he forced to leave Tibet. He was content in his teaching and understanding, especially in strong belief that "gradual enlightenment is a metaphysical impossibility." Similar to Shen-hsiu's position with the Southern School, Mahayana did not realize the long term results of the debate. Mahayana later wrote several memorials to the king, one of which says:

Never have I, Mahayana, been lacking, when one of my

disciples whom I am teaching comes to interrogate me

concerning my views and interpretations. Never do I fail

to teach him the field of merits which is giving (dana),

and to get him to take a vow of abandon...his body, his

head, his eyes, and every necessity except the eighteen

things the Great Vehicle permits.The fate of the Chinese Ch'an schools following the debate is very confused. According to R.A. Stein, the Chinese were kicked out of Tibet "in no gentle fashion." In reality, it is much more complicated. Ch'an continued in Tibet for many years following the debate at bSam yas. In fact, the attention given to the Northern School peaked the interests of Tibetans even more, thus perpetuating the practice of Ch'an and Chinese approaches for many years afterwards, but without the political and social trappings that Ch'an had been accustomed to.

Also, it is believed that the popularity of Ch'an resulted in its spread beyond the borders of Tibet into Central Asia. John McRae is a strong proponent of the idea that the influence of Northern Ch'an was not restricted to Tibet. For example, Northern Ch'an texts were translated into many Central Asian languages, including Hsi-hsia and Uighur.

Northern Ch'an also may have played an important role in influencing Tibetan philosophy outside of the Ch'an tradition. According to Tucci, Ch'an may have played an influential role in shaping rDzog-Chen philosophy. However, he bases his claims on sections of the BLon-po and bKa'thang sde-lnga, a rNying-ma/rDzogs- chen document from the 14th Century. However, Tanaka and Robertson question the historical authenticity of this document also. Tanaka and Robertson argue that "...the Bsam-gtan by gNubs-chen Sangs- rgyas ye-shes (772-892), a major Rdzogs-chen figure, shows clearly that Ch'an and Rdzogs-chen must be considered doctrinally distinct traditions." Samten Gyaltsen Karmay agrees with this interpretation. He writes:

One might get the impression that this work [the sBas

pa'i rgum chung] contains certain ideas that are parallel

to those of the school of the simultaneous path (cig car

'jug pa'i lugs). However, it would perhaps be too naive

to assume that once mention is made of mi rtgo pa, it is

"influenced by the Ch'an school".... On the other hand,

there are certain elements which have no parallel in the

Ch'an school. It is undeniable that mi rtgo pa is taken

as the central dogma of the Ch'an school, but it has

always been the most important aspect of Buddhist

contemplation in general.Even if Ch'an did not directly influence rDzogs-chen thought, its philosophy was at least preserved in Tibetan documents as an example of improper practice, thus at least preserving the philosophy as a negative example.

It is ironic that Northern Ch'an could lose two separate debates regarding the issue of sudden or gradual enlightenment. Northern Ch'an lost its position in China after Shen-hui claimed that they practiced the "dreaded" gradual enlightenment approach. Then, in Tibet, Northern Ch'an faced the same fate after being accused of the "dreaded" sudden enlightenment approach. It seems that the suddenness or gradualness of enlightenment had very little to do with either of these debates. They were both lost due to the inability of the Northern School, represented by two different teachers, to realize and correctly interpret the political climate and potential outcome surrounding these doctrinal debates. Each debate is characterized by a poor evaluation of political support and an unhealthy proximity to government officials and state patronage.

The integrity, sincerity and intelligence of the individuals involved has never been an issue. Joseph Roccasalvo points out about Hva Shan Mahayana,

...we have encountered a man of deep interiority, whose

"passion" for the truth and whose respect for

transcendence have led him to ever more subtle levels of

expression and paradox, but who knows down deep (like

Gotama before him) that the real truth "is only

transmitted and conferred by silence."Unfortunately, the politics of religion usually have very little to do with sincerity and truth. Arguably, the most important teaching to come from the Northern School, and passed to later teachers in China and Japan, was the avoidance of centers of political power. The founder of the Soto school in Japan, Do-gen Kigen, was warned by his Chinese teacher Ju-ching:

You should not live in cities or other places of human

habitation. Rather, staying clear of kings and

ministers, make your home in deep mountains and remote

valleys, transmitting the essence of Zen Buddhism

forever, if even only to a single true Bodhiseeker.

Works Cited

Dumoulin, Heinrich. Zen Buddhism: A History, Vol 1. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1988.

Gimello, Robert M. and Peter N. Gregory, Ed. Jeffrey Broughton. "Early Ch'an Schools in Tibet." Studies in Ch'an and Hua-yen, Studies in East Asian Buddhism, no. 1. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1983.

Goodman, Steven D. and Ronald M. Davidson, Ed. Kenneth K. Tanaka and Raymond E. Robertson. "A Ch'an Text from Tun-huang: Implications for Ch'an Influence on Tibetan Buddhism." Tibetan Buddhism: Reason and Revelation. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992.

Gregory, Peter N., Ed. John R. McRae. "Shen-hui and the Teaching of Sudden Enlightenment in Early Ch'an Buddhism." Sudden and Gradual. Studies in East Asian Buddhism, no. 5. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1987.

Gregory, Peter N., Ed. R.A. Stein. "Sudden Illumination or Simultaneous Comprehension: Remarks on Chinese and Tibetan Terminology." Sudden and Gradual. Studies in East Asian Buddhism, no. 5. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1987.

Karmay, Samten Gyaltsen. The Great Perfection (rDzogs Chen). Leiden, THE NETHERLANDS: E.J. Brill, 1988.

Lai, Whalen and Lewis R. Lancaster, Ed. Luis O. Gomez. "Indian Materials on the Doctrine of Sudden Enlightenment." Early Ch'an in China and Tibet. Berkeley Buddhist Studies Series, no. 5. Berkeley: Asian Humanities Press, 1983.

McRae, John R. The Northern School and the Formation of Early Ch'an Buddhism. Studies in East Asian Buddhism, no. 3. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1986.

Roccasalvo, Joseph F. "The Debate at bSam yas: A Study in Religious Contrast and Correspondence." Philosophy East and West. December, 1980.

Samuel, Geoffrey, Trans. Giuseppe Tucci. The Religions of Tibet. Berkeley: The University of California Press, 1988. Stein, R.A. Tibetan Civilization. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1972.

Yampolsky, Philip B., Trans. The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch. New York: Columbia University Press, 1967. Yokoi, Yuho. Zen Master Dogen. New York: Weatherhill, 1987.

Ishida, Hoyu. “The Problem of Practice in Shen-hui's Teaching of Sudden Enlightenment” in Academic Reports of the University Center for Intercultural Education, the University of Shiga Prefecture, No. 1, December 1996.

Robert Zeuschner, “An Analysis of the Philosophical Criticisms of Northern Ch'an Buddhism,”

PhD dissertation, University of Hawaii, 1977.

Zeuschner tackles the longstanding charges by propagandist Shenhui of the “Southern School” of Chan Buddhism that the so-called “Northern School” of Shenxiu, et al., was quietist, dualistic, and teaching an inferior path of gradual enlightenment. Zeuschner shows how Shenhui and his Southern School were attached to “Absolute level” discourse (paramartha-satya) and the strict prajna-wisdom approach, whereas Shenxiu and his colleagues were more willing to use both Absolute-truth teachings and also pragmatic, compassionate, relative-truth teachings (samvrti-satya) as a form of upaya, skillful means, to help liberate fellow sentient beings. Zeuschner's dissertation, worth reading for anyone still confused on this point, is archived at

http://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/handle/10125/10044/uhm_phd_7801060_r.pdf?sequence=2

The

Hsien Tsung Chi (An Early Ch'an (Zen) Buddhist Text)

by Robert B. Zeuschner,

Journal of Chinese Philosophy, V. 3 (1976) pp. 253-268.

http://ccbs.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-JOCP/jc26898.htm

The 顯宗記 Hsien Tsung Chi [Illuminating the Essential Doctrine] is one of the most philosophically important of the writings of the Ch'an master Ho-tse Shen-hui (670-762), a disciple of the Sixth Patriarch Hui-neng.

Matthew J.Wilhite

A Review of Fathering Your Father: The Zen of Fabrication in Tang Buddhism. By Alan Cole. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009

http://blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/files/2011/02/JBE-Wilhite.pdf

Notes by Ruth Fuller Sasaki:

神會和尚遺集 SHEN-HUI HO-SHANG I-CHI (Japanese, Jinne osho ishu), MS. fragments of the T'ang version from the Tun-huang caves, published by Hu Shih (Shanghai: Oriental Book Company, 1930), 220 pages. Recorded discourses and conversations of Ho-tse Shen-hui (Japanese, Kataku Jinne) (668-760), a disciple of the Sixth Patriarch, who made himself famous through his successful defense of the school of "sudden awakening (tun-wu)," considered to have been founded by his master, against that of "gradual awakening (chien-wu)," or the school of Northern Zen, founded by Shen-hsiu (Japanese, Shinshu), a fellow disciple of Hui-neng under the Fifth Patriarch, Hung-jen (Japanese, Gunin).

荷澤大師顯宗記 HO-TSE TA-SHIH HSIEN-TSUNG CHI (Japanese, Kataku daishi kenshu ki), in the Ching-te ch'uan-teng lu, chuan 30, Taisho, No. 2076 (Vol. LI, pp. 458c.25-459b.6). A short work by Ho-tse Shen-hui. The Tun-huang version of this text forms chuan 4 of the Shen-hui ho-shang i-chi (IV, above), where it bears the title Tun-wu wu-shen po-jo sung 頓悟無生般若頌 (Japanese, Tongo musho hannya ju). For the French translation of this version, see Gernet, op. cit., pp. 106-110.

"Elucidating the Doctrine," translated by Wing-tsit Chan, in Sources of Chinese Tradition, pp. 396-400. Though the translator has based his work on the Ching-te ch'uan-teng lu text, he has emended this at certain points in the light of the Tun-huang version.

南陽和上頓教解脫禪門直了性壇語 NAN-YANG HO-SHANG TUN-CHIAO CHIEH-T'O CH'AN-MEN CHIH-LIAO-HSING T'AN-YU (Japanese, Nanyo osho tongyo gedatsu zemmon jikiryosho dango), Tun-huang MS. (Pelliot) 2045. A discourse of Ho-tse Shen-hui (see above, IV) in which he recommends the "sudden school" (Tun-chiao) of Zen over that of the "gradual school" (chien-chiao), to which he is vigorously opposed.

Biography of the Chan Master Shi Shenhui 釋神會

Translated by Rev. Thich Hang Dat

(T no. 2061,50:756c07-757a14)

http://www.thichhangdat.com/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/Biographies_of_Chan_Masters.84231542.pdf

The biography of Chan Master Shi Shenhui 釋神會 (670-762) of Heze

荷澤 temple, in Luo Jing 洛京77 during Tang 唐 dynasty

Shi Shenhui‟s last name was Gao 高, and he was of the Xiangyang 襄陽 people.78

He had upright character and learned brightly and vigorously since his youth. He

followed his teacher to learn the five texts [of Confucianism]79 and had ability to

understand them deeply and profoundly. Next, he searched for the magical talismans of

Zhuangzi 莊子 (369-286 BC) and Laozi 老子(c. 500 BC). He evaluated the History of

Late Han (25-220 CE)80 and understood the teaching of Buddha. Because he paid

attention to the teaching of Śākya [Buddhism], he did not have intention to be official. He

said farewell to his parents and went to Guochang 國昌 temple in his prefecture to leave

home life under Dharma master Haoyuan 顥元. He recited many sutras easily as turning

the palm [everything went well for him]. He did not like to expound the whole vinaya. He

heard the model of Chan master Huineng 慧能 at holy Caoxi 曹溪 of Lingbiao 嶺表,

who raised the magnificent Buddhadharma that the [Buddhist] scholars hurriedly went to

learn. He followed Sudhana‟s81 example of going south to seek the teaching. He went

77 Namely, it was the Luoyang 洛陽 capital.

78 Xiangyang district of Xiangfan city 襄樊市, Hubei 湖北.

79 The Five Classics of Confucianism are the Book of Songs (Shi jing 詩經), the Book of History (Shu jing

書經), the Classic of Rites (Liji 禮記), the Book of Changes (Yi jing 易經), and the Spring and Autumn

annals (Chun qiu 春秋).

80 Hou Han Shu 後漢書.

81 Ch. Shancai 善財 (Good Wealth) was a youth from India who was seeking enlightenment. At the behest

of Mañjuśrī, Sudhana takes a pilgrimage on his quest for enlightenment and studies under fifty-three "good

with worn out garments and bound feet; he considered thousand miles as within a short

step.82

When just seeing Shenhui, Huineng asked, “Where did you come from?” Shenhui

replied, “I came from nowhere.” Huineng asked, “Why don‟t you return [to that place]?”

Shenhui replied, “There is not a single place to return to.” Huineng said, “You are

extremely incomprehensible.” Shenhui said, “My body‟s predestined affinity is on the

road [path of enlightenment].” Huineng said, “Because you yourself have not reached [to

enlightened stage] yet.” Shenhui replied, “Although now I have reached it, I do not hold

it.”

Shenhui stayed at Caoxi for many years, and later on he went out everywhere to

search for famous holy places. During the eighth year of Kaiyuan 開元 reign (713-741),

he followed imperial order to join and live in the Longxing 龍興 temple of Nanyang

南陽 prefecture.83 He continuously and broadly propagated the bright sound [profound

doctrine] of Chan Dharma [teaching] in Luoyang 洛陽.84 At first, the two capitals85 were

Shenxiu 神秀‟s teaching places. If he [Shenhui] did not explain to the public that his

teacher, Huineng, was transmitted the Dharma robe and bowl [as a symbol for mind to

mind transmission] by Hongren to be the formal Six Patriarch, then Shenxiu would claim

that position [of Six Patriarch] for himself.86 Since Shenhui had seen [awakened] his

mind under the teaching‟s style of Huineng, he wanted to sweep away that gradual

friends." He was the main protagonist in the next-to-last and longest chapter (39) of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra

(Ch. Hua yan jing 華嚴經).

82 The meaning is that he did neither concern his health nor the difficulty in searching for good teacher.

83 Nanyang prefecture level city in Henan.

84 Luoyang prefecture level city in Henan, an old capital from pre-Han times.

85 Changan 長安 and Luoyang 洛陽.

86 I translate it from the sentence, “If the fish does not calm the water, then the little tuna relies on the pond

and act as the dragon.”

teaching. So, the judgmental distinction of two schools of North and South was initiated

since then. Because he went to Puji‟s87 place [to argue], later on he was in trouble.

During Tianbao 天寶 reign (743), because Imperial Censor88 Luyi 盧弈 schemed with

Puji, they [Luyi and Puji] presented the letter that falsely accused Shenhui of gathering

the doubtful and harmful apprentice people. Emperor Tang Xuanzong 唐玄宗 (685-762)

summoned Shenhui to go to the capital. At that time, he responded to the emperor with

language and principals cleverly and satisfactorily at Tangchi 湯池. An imperial order

moved him to go to Junbu 均部.89 Two years later, an imperial order changed his

residence to live at the Prajñā 般若 institution of Kaiyuan 開元 temple in Jingzhou

荊州.90

Fourteen years later, the rebellion of An Lushan 安祿山 (703-757) of Fanyang

范陽 took arm going toward the capital. There was disorder [and confusion] within the

two capitals. The emperor escaped to Bashu 巴蜀.91 Deputy Marshal Guo Ziyi 郭子儀

commanded the army to suppress the rebellion. However, because the army supplies were

depleted,92 Deputy Marshal Guo Ziyi used the expedient scheme of the Vice Director of

the Right of the Department of State Affairs93 Peimian 裴冕. He set up the precept

platform within the government great repository to transmit the monastic disciplines for

87普寂(651-739).

88 Yushi 御史.

89 It is Junzhou 均州 province.

90 Jingzhou prefecture level city on Changjiang in Hubei 湖北.

91 Sichuan was originally the province of Qin dynasty 秦朝 (221-206 B.C) and Han dynasty 漢朝(206 B.C-

220 A.D).

92 I translate its meaning literately from the sentence “Feiwan souran 飛輓索然” as the flying and changing

direction [of food] which cause [the food] being dry.

93 Yu pushe 右僕射.

monks. The monks paid taxes [duties] by string of coins which was called the money of

perfume water. They collected these monies to support the army‟s necessaries.

Initially, when the capital Luoyang was captured, Shenhui quickly escaped to the

wilderness. At that time, Luyi 盧弈 was assassinated by his enemy. The group [of

officials and monks] discussed and then requested Shenhui to preside at that precept

platform. At that time, [most of] the Buddhist and Taoist monasteries and temples were

burned down to ashes [because of war]. Therefore, they expediently created [constructed]

a temporary institution [temple] which used hard resources [of grasses] to build the

temple and an altar platform within it. The collected monies were used for military

expenditure. During Tang Daizong 唐代宗 reign (726-779), Guo Ziyi 郭子儀 recaptured

the two capitals which received considerable support and effort of Shenhui. Emperor

Tang Suzong 唐肅宗 (711-762) summoned Shenhui to go to the inner imperial court to

receive the offering; [the emperor] ordered the great [talent] craftsmen and workers

working together to build a Chan hall within his Heze 荷澤 temple. Shenhui expounded

Huineng‟s lineage Chan teaching style and development prominently which caused

Shenxiu‟s teaching to become lonesome [disappear].

During the first year of Shangyuan 上元 reign (760), Shenhui enjoined and said

farewell to his disciples. He shunned his seat, gaze the emptiness, bowed and returned to

the [his] abbot‟s room, and passed away on that night. He lived for ninety-three years. On

the thirteenth day of the Jianwu 建午 month,94 his pagoda was moved to Baoying 寶應

temple at Luoyang 洛陽. The emperor gave imperial posthumous name of “Zhenzong

Dashi 真宗大師” [Great Master True Ancestor], and his pagoda was named as “Prajñā

般若” [Wisdom].

94 The fifth month.

Biography

http://www.speedylook.com/Shenhui.html

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shenhui

Shen-Hui was the founder of its branch Heze or Ho-tse (荷澤), active until the end of the Dynastie Tang, from where its title of Maître of Heze (荷澤大師). Its posthumous name, decreed by the Suzong emperor, is Zhenzong Dashi (真宗大師), Maître of the true doctrines. According to the sources, it would have had at its death 73 or 83 years. The dates given for its birth vary between 668 and 686, those proposed for its death between 748 and 762. Some consider that he is the true initiator of the movement Subitiste in the place of Huineng of which he proclaimed successor.

Recommending the exclusive teaching of the sudden illumination, it was during its southernmost stay drawn aside of the dominant branch of Chan, Dongshan (東山), founded by Daoxin and Hongren and then represented by Puji, successor of Shenxiu . In 734 (or 732), the day of the Festival of the lanterns, it organized with the monastery of Dayun (大雲寺) with Huatai (滑台) in Henan a large gathering called Kumbhamelâ (無遮大會), on the occasion of which it discussed against a Dongshan Master. It is there that it publicly blamed for the first time the value and the legitimacy of Dongshan, applicant whom this school taught only the method gradual, lower, and whom his line did not kill directly from Bodhidharma, Hongren having indicated Huineng and not Shenxiu like successor. He will lay down his written doctrines between 745 and 753 in the Essentiel of the doctrines (顯宗記), on which the image of Chan of the South " is founded; subitiste" against Chan of North " gradualiste". The specialists in second half of the 20th century since called somewhat this vision into question, and consider that the thought of Huineng was attached to that of the Dongshan school, which taught at the same time the methods sudden and gradual. Shenhui would be the true promoter of the integral subitism.

Towards the end of the 8th century, the school of the South had replaced that of North, Dongshan, like forms dominant of Chan. In 796 , some thirty years after the death of Shenhui, the Dezong emperor ordered to the crown prince to convene an assembly of Chan Masters to designate the seventh patriarch officially: it will be him. Its nomination is confirmed by the Éloge with the seventh patriarch (七祖贊) and a stele with the monastery of Shenlong (神龍寺). Huineng thus became at the same time the sixth official patriarch.

33/6. Huineng (638–713)

34/7. Heze Shenhui (670–762)

35/8. Weizhou Ji

35/8. Jingzhou Huijue

35/8. Taiyuan Guangyao

35/8. Fuzhou Lang

35/8. Xiangzhou Jiyun

35/8. Dayuan

35/8. Moheyan

35/8. Jingzhu Puping

35/8. Heyang Huaikong

35/8. Jingzhou Yan

35/8. Fucha Wuming

35/8. Hengguan

35/8. Luzhou Hongji

35/8. Xiangzhou Fayi

35/8. Fahai

35/8. Xiazhou Jingzong

35/8. Fengxiang Jietuo

35/8. Huijian

35/8. Huanglong Weizhong (705–782)

35/8. Xiangzhou Zizhou (bd)

35/8. Wutai Wuming (722-793)

35/8. Cizhou Faru (723–811) (Zhiru)36/9. Yizhou Nanyin (bd) (Jingnan Weizhong)

37/10. Shenzhao (Zhaogong)

37/10. Yizhou Ruyi

37/10. Jianyuan Xuanya

37/10. Suizhou Daoyuan (bd)38/11. Guifeng Zongmi (780–841)

39/12. Chuanao

Hu Shih

Ch'an (Zen) Buddhism in China: Its history and method

Philosophy East and West, Vol. 3, No. 1 (April, 1953), pp. 3-24.

http://www.thezensite.com/ZenEssays/HistoricalZen/Chan_in_China.html

Is Ch'an (Zen) Beyond Our Understanding? For more than a quarter of a century, my learned friend. Dr. Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, formerly of the Otani University, Kyoto, Japan, has been interpreting and introducing Zen Buddhism to the Western world. Through his untiring effort and through his many books on Zen, he has succeeded in winning an audience and a number of followers, notably in England. As a, friend and as a historian of Chinese thought, I have followed Suzuki's work with keen interest. But I have never concealed from him my disappointment in his method of approach. My greatest disappointment has been that, according to Suzuki and his disciples, Zen is illogical, irrational, and, therefore, beyond our intellectual understanding. In his book Living by Zen Suzuki tells us:

It is this denial of the capability of the human intelligence to understand and evaluate Zen that I emphatically refuse to accept. Is the so-called Ch'an or Zen really so illogical and irrational that it is "altogether beyond the ken of human understanding" and that our rational or rationalistic way of thinking is of no use "in evaluating the truth and untruth of Zen"? SHEN-HUI AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF CHINESE CH'AN The story will begin with the year A.D. 700, when the Empress Wu 武后 (who reigned as "Emperor" from 690 to 705 ) invited an old Ch'an monk of the La^nkaa School 楞伽宗 [5] to pay her a visit at the capital city of Changan. The monk was Shen-hsiu 神秀, who was then already over ninety years old and had long been famous for his dhyaana (meditation) practice and ascetic life at his hilly retreat in the Wutang Mountains 武當山 in modern Hupei. The imperial invitation was so earnest and insistent that the aged monk finally accepted.