ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

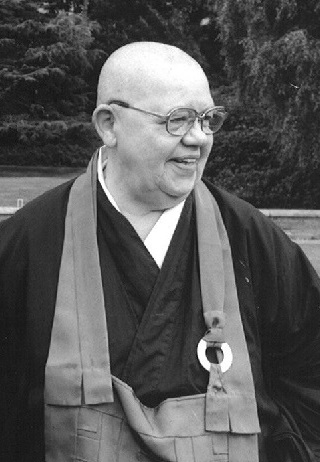

Myokyo-ni

妙教尼 Myōkyō-ni, born Irmgard Schloegl (1921-2007)

![]()

Ven. Myokyo-ni, Irmgard Schloegl (1921–2007), was trained at Daitokuji monastery in Japan, where for twelve years she worked under two successive masters, Oda Sesso Roshi and Sojun Kannun Roshi. In 1977 she founded the Zen Centre in London. She was ordained in 1984 as the Ven. Myokyo-ni by Soko Morinaga Roshi and became abbess of the Zen Centre's two training temples, Shobo-an and Fairlight, over which she presided until her death in 2007. Ven. Myokyo-ni translated many important Zen classics from the Chinese and Japanese into English, as The Zen Teaching of Rinzai and The Discourse on The Inexhaustible Lamp of the Zen School (with Yoko Okuda). She also wrote many instructive books on Zen training—among them, The Zen Way and Gentling the Bull.

Official portrait of Daiyu Myokyo Zenji* by Roberta Mansell.

Copyright of The Zen Centre.

*Daiyu (meaning 'Great Oak') was added to Ven. Myokyo-ni's name posthumously so that she is now formally known as Daiyu Myokyo Zenji.

The Venerable Myokyo-ni

Leading Buddhist nun who was head of London's Zen Centre

by Simon Blomfield

The Guardian, Monday 23 April 2007

The Rinzai Zen Buddhist nun, the Venerable Myokyo-ni, who has died aged 86, was head of London's Zen Centre. A pioneer of Buddhist practice in the west, she was a formidable presence in the British Buddhist world. Born Irmgard Schloegl, in Leitersdorf, Austria, she took a PhD in physical sciences at Graz University. She came to Britain in 1950 as a lecturer in mineralogy at Imperial College, London, and soon after joined the Buddhist Society. Schloegl enrolled in the society's Zen class led by the judge, Christmas Humphreys QC, who had founded the society in 1924. His teaching was characterised by enthusiasm and intellectual excitement rather than lengthy periods of meditation.

In 1960, Schloegl went to Japan and trained at Daitokuji monastery, Kyoto, for 12 years, making her part of the first generation of westerners to undertake intensive Zen training in Japan. Founded in 1319, Daitokuji is the head training monastery of a subsect of the Rinzai school of Japanese Zen. Its practice included intensive zazen (sitting meditation), contemplation of koans, and strict adherence to monastic forms. Others who underwent such training have written graphic accounts of its rigours - sitting on the shins all day till they vomited, beatings for minuscule infractions - but Schloegl was reticent about passing on her experiences. Her path in negotiating monastery life may have been eased by studying with Ruth Fuller Sasaki, an American woman who was already accepted as a Zen priest and ran a training temple for foreigners within Daitokuji.

In 1966 Schloegl returned to England for nine months and started a zazen group at the Buddhist Society, which continued until she returned permanently in 1972. Once she was back in London, she lived as a lay woman, and stayed at Humphreys's St John's Wood house, leading classes there and at the Buddhist Society.

In 1979 the group was formed into the Zen Centre and when Humphreys died in 1983 he bequeathed his house to the centre. It was eventually inaugurated as Shobo-an, Hermitage of the True Dharma, and it served as the centre's main administrative location and training temple. All Zen activities at the Buddhist Society then came under Schloegl's direction and a group of her students assumed a dominant role in the society's affairs. (Fairlight, a second training temple near Luton opened in 1996 and she lived there from 2002.)

On July 22 1984, Schloegl was ordained at a ceremony conducted by Soko Morinaga Roshi, head monk during her time at Daitokuji, who gave her a monastic name. Myokyo, meaning "mirror of the subtle", was the name he had previously given her in Japan, while "ni" means "nun".

Myokyo-ni wrote several books that describe Zen practice in a straightforward way, and she translated from Chinese a key text, The Zen Teaching of Rinzaiby by Lin Ji, the school's founder.

While Myokyo-ni's teaching was very different from that of Humphreys she agreed with him on the need to understand the basics of Buddhist teaching before embarking on Zen; and like Humphreys she stressed that Zen was part of Buddhism, as all schools were true to the same principles: "Many schools; one way."

Before her trip to Japan she had undergone Jungian analysis, and she spoke of Buddhist practice as a means to the transformation of the psyche and the aspiration of the heart towards wholeness and compassion (without losing sight of "the shadow").

In keeping the traditions she had encountered at Daitokuji, Myokyo-ni was strict with her students, saying: "[The hardships] are there to quell the fires within us." Some students took to this regime and a band were loyal to her over many years, a number becoming monks and nuns. Others balked at her approach, finding it overbearing.

But all who knew Myokyo-ni encountered her strength of character - sometimes fiercely insightful, sometimes deeply compassionate. Especially in dokusan, the formal interviews between student and master that can be occasions for direct encounter, she could embody an uncannily powerful presence.

· The Venerable Myokyo-ni (Irmgard Schloegl), Zen Buddhist teacher, born January 29 1921; died March 29 2007

The Story of Daiyu Myokyo Zenji

"Upon the Death of Venerable Myokyo-ni," Zen Traces, June 2007

http://www.thezengateway.com/latest-news/the-story-of-daiyu-myokyo-zenji-pt1

Venerable Myokyo-ni used to joke that she was really three hundred years old!

She described the rural area of Austria where she originated as being happily stuck in that time period. Some may have seen this as a stubborn refusal to ‘move with the times’; however perhaps it was rather a restraining hand on our fascination with everything new.

These days when the word ‘new’ has become synonymous with ‘improved’ we are apt to roll our eyes at anything traditional. And yet we have a feeling that having thrown away our past something important has been lost.

This ‘old’ or perhaps collective wisdom of past experience that is by nature our common lot was precisely the subject matter of so many of the stories and sayings that Ven. Myokyo-ni would recount so vividly in her teisho or at the dining room table. Who does not recall such ‘Austrian sayings’ as “He is no good rider who has not kissed the dust” or “A healthy man has a thousand wishes a really sick man has only one.”

Always her own anecdotes were seamlessly matched up with whatever aspect of the Buddha’s teaching she was trying to explain. This ability to match the content of a teaching over 2,500 years old with the rough and tumble of a modern day European life showed just how those teachings are still as relevant here today.

Even something as simple as learning to ride a bike contained a level of profundity. She spoke of her experience on the rather pot-holed and stony roads of the surrounding area of her childhood. How she would stem herself against that big stone in the middle of the road some distance ahead only to find herself drawn like a magnet towards it and hitting it. Once she had gained in confidence and the fear was quieted, then not only did she no longer hit such stones but found she was unable to do so deliberately. This story she would finish by quoting a familiar psychological law that “Whatever we push away, we give power over ourselves.”

On another occasion she fell and broke her leg. Up until that time she had had an intense reaction against the thought of broken bones. So strong was this aversion to the imagined pain that even the thought of it made her nauseous. When it finally happened she reported her first thought was not horror but a surprised realisation that “It doesn’t hurt!” The shock had inured her to the pain initially but what it brought home was the way our imagination, when fired up, can be so misleading.

To our tendency to cram as much into our lives making them more busy and even more busy she would describe a typical Sunday from her own childhood. How it was not uncommon to see on a sunny day families outside for the afternoon sitting in the shade hands in lap, not talking just sitting looking on. Such periods of quiet were not imposed or artificial but quite natural.

Although it is a common complaint that we have little peace in our lives, we seem to ensure that as much as possible such periods of quiet spaciousness are not able to arise. Is it really so that the only way to produce it is to use floatation tanks?

Venerable Myokyo-ni was a keen horse-woman and maintained an abiding interest throughout her life.

She said she was taught by a very traditional and strict teacher who did not put on any airs and graces and made no compromises when it came to training riders. This was so even if it meant some potential ‘customers’ were put off.

On the subject Ven. Myokyo-ni talked about how part of the training involved walking the horse into the four corners of an arena. There would be several riders doing this and the teacher stood in the middle with a long whip.

The horse did not always like to go right into the corner but that was the exercise and so the rider had to ensure that it did. So for one, two and three corners it would go, but at the fourth the rider, feeling tired, might not be too bothered and the horse gets away with cutting the corner.

Now back to the first corner again and with the teacher looking at the rider the horse goes in the same with two and three but the fourth?

Well the horse knows it got away with it the last time so it certainly isn’t going to do it this time. The teacher sees it and the whip cracks just behind the rider jolting them both into the corner again. This is an important lesson in working with those energies personified in Zen as the Bull to ensure consistency in the discipline.

Ven. Myokyo-ni made the point that she had known a couple of Zen Masters before Master Sesso, her official teacher.

She often cited her old geology professor as falling into this category. One day he walked into the lecture room and drew a line on the blackboard. “There will be those who say this is a straight line and there will be those who say it is not.” Then he took the blackboard ruler and laid it along the line saying, “All that is necessary is to take this ruler and do this and then see for yourselves.”

This is a lesson to be taken to heart by those of us who would rather speculate than jump in and find out for ourselves.

Ven. Myokyo-ni’s professor also taught her the importance of pacing oneself when making an effort over an extended period of time.

On geology field trips his young students would dash ahead up the mountain paths. However, they would soon tire and the old professor, having set a steady pace from the start would catch up to them and like the tortoise in Aesop’s fable overtake his hares.

After university Ven. Myokyo-ni began working with mining communities. One of these was on the Austrian-Italian border where mining has taken place since Roman times. She was immediately impressed by their methods. They had found a number of clever low-tech solutions to mining problems regularly encountered during the extraction process. When she remarked on this to the guide who was showing her around the site he said that over the years they had developed a useful method of dealing with problems.

They would take a lazy but intelligent miner and place him at just the point in the process where a particular problem had occurred. Within two weeks he would usually come up with a solution. Then it was simply a matter of recording it in the ledger and applying this solution more generally when necessary. We are often quick to judge our character traits and we seek to get rid of the ones we deem undesirable.

Yet the Buddha after converting demons would put them to work as Dharma guardians at the gates of the temple. It’s not a matter of eradicating our traits but finding a useful way of employing them for the benefit of all.

Ven. Myokyo-ni used to type with only two fingers of each hand. At some point she decided that it would be more useful to type properly using all her fingers. This was before computer programmes so she used a book with finger exercises. They proceeded from the simplest to the more complicated ones showing how to use one’s fingers in the best way over the entire keyboard.

The first time she completed the course she found that her old habits kept resurfacing. So she picked up the book and started over at the beginning. Again she found, upon completion of the exercises, that the old habits were interfering with the new skill, so she picked up the book and opened it again at the first page. Having done this three times the old habits refused to die. So she said to herself that she would give it ten more minutes and if her fingers had not switched over to the new way then it would be a matter of starting the book from scratch yet again.

She set her timer for ten minutes and before the buzzer went the transfer to the new skill had occurred.

The practice of Zen involves working with our emotional reactions.

These are known in the training as “the fires” and there are useful methods we can employ to get to grips with this precious energy.

Ven. Myokyo-ni often said that it was a good idea to keep one or two tasks at hand that one did not particularly like for those times when the fires flared.

If one was seized by a mood or some restless energy flared up that threatened to turn into thought streams and fantasies then one could take up one of these tasks and pour the heart’s energy into it instead.

In Ven. Myokyo-ni’s case she kept a pile of darning to be completed. She said that by the time she was finished the energy was not only used up but would result in a very well-done job - as one would expect. The fires have a touch of divinity about them!

Before Zen became popular in the West, Christmas Humphreys invited Professor Ogata-san to England to give a talk to the Buddhist Society.

The Society’s Zen group turned out in force. For many it was the first time they had heard a talk by someone who had gone through training in a traditional monastery.

Ven. Myokyo-ni like all the others was filled with eager anticipation.

The question on everyone’s mind was: ‘Can a Westerner train in Zen?’

“As I see it”, said Ogata-san in his broken English, “there is no reason why a Westerner cannot train in Zen. The only obstacle is your continual pranning, pranning, pranning.”

So now they knew the answer to the question. The only problem to be overcome was ‘pranning’! But what was this ‘pranning’?

In his summing up Christmas Humphreys, whose ear was more accustomed to Ogata-san’s accent, said: “And so our venerable speaker pointed out that the only real obstacle to Zen training is our continual planning, planning, planning.”

The audience was perplexed. “We didn’t think that we spent our time planning. What was this all about?” said Ven. Myokyo-ni. However, years later when she was training in Japan the memory of that day floated up and she realised just how accurate a diagnosis of our condition Ogata-san had given.

In 1960 Ven. Myokyo-ni went to Japan to start her Zen training in earnest.

Initially she attended the little training temple for foreigners set up by the First Zen Institute of America in Japan and run by Sokei-an’s widow Ruth Sasaki.

Here the hopefuls were introduced to life in a Japanese training place and had to acclimatise to the way things were done.

The Japanese custom was to sleep on a futon on the floor. Many Europeans and Americans had difficulty doing this and complained of back problems to which Mrs. Sasaki would reply, “Sooner or later something will have to give and it won’t be the floor!”

After Ven. Myokyo-ni was accepted as a sanzen student by Sesso Roshi, the Lord High Abbot of Daitoku-ji, the pace of her training stepped up considerably.

She had to rise in the middle of the night to attend the first sanzen period of the day and in the cold Japanese winter this was a real test of aspiration in itself. Ven. Myokyo-ni had always felt the cold and would hug the stove heater in her little flat until the last possible moment before dashing down the hill to the monastery gates.

She remarked however that once through the gates the concern over cold dropped away because there was simply no option any more. She said this experience taught her a lot about how we go about exacerbating our difficulties by clinging to our (‘my’) wishes.

In the southern tradition the Buddha upon his Awakening pronounces that he has seen the ‘builder of the house’ and that with the ridgepole now broken never will he build houses again. This builder of houses is the same as the picture maker.

Inevitably with things we like and dislike ‘I’ build pictures around them. Ven. Myokyo-ni often talked about her own experience of this. She had built up a most beautiful mosaic about what Zen and Buddhism was all about. Whilst training in Japan that mosaic had to be taken apart piece by piece with her own hand until it collapsed. A few tears were shed along the way but there was too little left to support it. Once our illusions are gone suddenly the seeing is clear. The fullness of life, no longer obstructed, floods in and the heart responds with an outpouring of warmth.

Venerable Myokyo-ni always stressed the importance of good form and the fact that the Zen training simply cannot be effective – “will not go” - without it. She tirelessly pointed out how the body itself contains a wisdom of which ‘I’ am simply not aware.

Ven. Myokyo-ni took a little flat near Daitoku-ji temple. In typical Japanese style it comprised two little rooms, one above the other. The space was cramped and the bathroom was also very small. She found that every time she bent over the washbasin she banged the small of her back on the doorknob behind her. This happened a number of times until she was black and blue. At one point she seriously considered giving up the place but it was so conveniently situated she was reluctant to do so.

Some time later she had some visitors who stayed with her and after a couple of days one said “How do you manage in such cramped rooms? I continually crack my back against the door knob in the bathroom.” Suddenly she remembered how she too had done this, but it hadn’t happened for quite some time. At that moment she realised that without her conscious knowledge she had adapted to the cramped circumstances and no longer suffered from them.

Ven. Myokyo-ni’s teacher Sesso Roshi died in 1966. He was succeeded by Sojun Roshi, who had a very different style of teaching.

Yet Ven. Myokyo-ni always said that the phrase she heard from both of them more than any other was, “Look at the place where your own feet stand”. Inevitably the question arises, “What am I looking for there?” The response is “Look at the place where your own feet stand”. But the questioner might retort “And then?” At which the teacher repeats “Look at the place where your own feet stand!” Finally the student begins to look down at the very place where the own feet stand and at that moment a little voice rises from the depths: “Better not!” There’s a reason why we don’t see clearly in the first place.

When Sesso Roshi died, the senior monk Soko Morinaga paid a visit to Myokyo-ni. The passing away of one’s teacher is a momentous event and he wanted to see if she was alright. When she opened the door and saw him, she knew immediately why he was there and said “With his death he is now available for everyone.” With this Soko knew she would be fine.

The Roshi is a remote figure in a training monastery. He is only seen for teisho and sanzen. He has no other relationship with his students. Discipline is maintained by the senior monks and the day to day problems of students are dealt with by them as well. However the teacher represents more than just flesh and blood to the student. He is the living embodiment of the teachings. And the teachings themselves are only expressions of a spirit that cannot be seen directly. This spirit moves through every heart that is moved to follow those teachings. Thus the spirit of the teacher and the spirit that aspires to train are one and the same. They have the same face too. When we make room in our hearts for someone, particularly when we look up to them, we form a relationship with that which they represent. With the physical death what remains is that for which their life stood. It is this that is now freely available to all. Sesso Roshi made a deep impression upon her, which showed every time she referred to him.

“Just hatch it out!” was a frequently used phrase when a student came to Ven. Myokyo-ni with some problem. This hatching process was one she herself used on several occasions to good effect. During the interregnum - the period after the death of Sesso Roshi and before the new incumbent took up his position as head of Daitoko-ji temple - Christmas Humphreys sent Myokyo-ni a plane ticket to come back to London but she was reluctant to leave.

Having recently acquired a small flat that was well placed near the monastery, and having paid a large sum as key money, she was afraid she would now lose it. She tried putting up notices to see if she could rent it out but to no avail. As the date of the flight drew nearer she had to make a decision. What to do? So she did what she tended to do in these circumstances: she locked herself away for three days. Suddenly the answer came to her: “All this time as a Buddhist and Zen student I had heard about the followers of the Buddha being referred to as ‘leavers of home’. Here I was worrying over just that and making a meal of it. So without further ado I decided to give it up and marched over to the rental agency to notify them of my intention to leave.”

Apparently they were taken aback and warned her that she would lose that valuable sum in key money but she had already made up her mind. She left the office and felt somewhat lighter once the decision had been taken.

As she drew near the entrance to her building a dark figure loomed up from the steps and introduced himself as a visiting mathematics professor from America. He was looking for somewhere to rent for a temporary period and had seen her advert on the university notice board.

She showed him around the flat. Yes, he would like to take it and so it was agreed. She took him back to the agency and announced that she had a tenant and so would not be leaving the premises after all. At this point in the story Ven. Myokyo-ni would often laugh and add that this wasn’t the only time she experienced this phenomenon: “when something has truly hatched out and whatever is being grasped is relinquished, remarkably the Dharma comes up with something quite out of the blue!”

Another time she used the “hatching out” method to good effect during a voyage back to Japan on a container ship.

She said that these ships took a small number of passengers who, generally, were all of a similar type. These were people, often retired, whose spouses had died and were often quite lonely. The trips were undertaken to alleviate the loneliness of their home lives. She was moved by their plight and wanted to say something to them.

All she had to help them with were the Buddhist teachings but they were not going to understand the technical terms and in that setting it wasn’t appropriate to ‘preach’ or appear to do so.

There was a favourite place high up on the ship looking out at the ocean where she would retreat to when wishing to be alone. In these circumstances she again retreated as she did not know what to say. Again after a period it suddenly came to her that in fact what the Buddha taught could be put into ordinary everyday language. After all what he spoke about were the typical problems people have always had whether in the past or the present. There was no need to refer to any technical language or mention any Buddhist terms. So she returned below to the other passengers and was able to talk to them about their problems using the wisdom of the Buddha.

When she was preparing to come back to London, Ven. Myokyo-ni paid a visit to Kannun (Sojun) Roshi. He asked her what she would be doing when she got back. She responded that she wanted to set up a zazen group to which Kannun Roshi said “You will do no such thing! When you get to Heathrow airport you will sit yourself down and stay there. You will go on sitting and eventually people will begin to notice you there and become curious. They will wonder what gives you the strength to go on sitting there like that and they will ask you about it. Only then will you begin to teach.”

She would say laughingly, “Fortunately Christmas Humphreys was there at the airport to meet me and take me home. However I took to heart this advice of Kannun Roshi not to be beholden to anyone!”

Upon her return from Japan Ven. Myokyo-ni became a well-known figure working first in the library at the Buddhist Society and later as a member of its council. Eventually she was given the title of Honorary Vice-President in recognition of all her work in promoting its aims.

One day a trim, well-dressed gentleman came into the library and after looking round got into conversation with Ven. Myokyo-ni. He was from South Africa and always liked to call on the Society if time permitted. He said that he would be glad to get out of London because he found it a city full of temptation. He went on to explain that he had a fondness for cream cakes and it seemed that there was a patisserie on every street corner here. As he wished to keep his trim figure he found it a constant effort to resist the desire to indulge too much.

Myokyo-ni asked if he was willing to try an experiment. She told him to just carry on as usual and when he felt himself drawn to a cake shop to stand in front of it and look at the object of his desire in the window. All desire, she explained, arises as ‘I want something’. In this case it was a cake, so just when he really felt it he should close his eyes and go right into that wanting; he could drop the cream cake part and just have ‘I want!’ and then drop the ‘I’ and just go on with ‘wanting’ but to really give himself into it for about five minutes. “Then open your eyes and see what happens,” she told him. It turned out that he was quite willing to give it a try and off he went.

About a half hour later he was back with a beaming smile: “It works!” he said “I’m cured of my craving!” “Oh no you’re not!” Myokyo-ni replied. “However now you know how to deal with it.”

Venerable Myokyo-ni was also pivotal in developing the new format for Summer School.

Called ‘Deeper into Buddhism, it arose because the numbers attending the summer school in its old format had declined to a critical low. For a number of reasons there is a tendency here in the West to mix Buddhism with other disciplines and thus risk that it will become diluted or distorted. She would recall Christmas Humphreys, or ‘Father’ as she affectionately called him, saying that Buddhism in the West was like a bird. It had Theravada for its left wing, Tibetan for its right wing and Zen for its tail and no body! It seemed that we were always looking for the differences between schools and traditions,like different makes of biscuits on a supermarket shelf, unaware that all of them are firmly based on a similar recipe.

It was these core teachings that needed to be expounded so that practitioners from all traditions could have a venue to meet and learn together.

These are a few of the stories and anecdotes from the life of Venerable Myokyo-ni; there are many more. All those who knew her will have their own favourite stories but it would be a mistake to think that the spirit of wisdom contained in them is limited to a nostalgic remembrance. If this were so, there would be no virtue in re-telling them.

Because they express the very human strengths and foibles to which we are all subject, Venerable Myokyo-ni will live on in the hearts of those who knew her. She showed a Way she herself had walked for those who wish to do likewise. She is now available to all.

Works

Gentling the Bull: The Ten Bull Pictures: A Spiritual Journey by Myokyo-ni (Irmgard Schloegl), Zen Centre, London, 1988.

Selected Sayings of Master Daie Soko [大慧宗杲 Dahui Zonggao,1089–1163] with Myokyo-ni's comments

Zen Traces, Volume 33, Number 4, September 2011DOC: The Record of Rinzai Translated by Irmgard Schloegel

PDF: The Zen Teaching of Rinzai Translated by Irmgard SchloegelA Treatise on the Ceasing of Notions > PDF

Translated by Myokyo-ni and Michelle BromleyPDF: The Zen Way

PDF: The Wisdom of the Zen Masters

Yoka Daishi's Realizing the Way

Translation and Commentary by the Venerable Myokyo-ni

London: The Buddhist Society, 2017. 288 p.PDF: The Discourse on The Inexhaustible Lamp of the Zen School

[Shūmon mujintō ron]

by Tōrei Enji; with commentary by Master Daibi* of Unkan; translated by Yoko Okuda**

Foreword by Myokyo-ni

Published in Association with The Zen Centre, London, 1989

Boston : C.E. Tuttle Co., 1996. 560 p.*Shaku Taibi 釈大眉 (1882-?); Unkan 雲關

**Okuda Yōko 奥田陽子"Based on the teachings of the great Zen Master Hakuin Zenji, The Discourse on the Inexhaustible Lamp of the Zen School is an essential guide to Rinzai Zen training. It was written by Torei Enji Zenji (1720-1792), Hakuin's dharma successor. In this book, Master Torei begins by providing a concise history of the Rinzai school and lineage. He then details all the important aspects of Zen practice, most notably great faith, great doubt, and great determination. He also provides explanations of koan study and zazen (meditation) as a means of attaining true satori (enlightenment.). This edition includes extensive commentary by Master Daibi, providing both essential background information and clarification of several Buddhist concepts unfamiliar to the general reader. The result is an invaluable record of traditional Zen training."

香嚴智閑 Xiangyan Zhixian;

Kyōgen Chikan

(?-898)

In: The Wisdom of the Zen Masters

Translated by Irmgard Schloegl

New Directions Publishing Corporation, New York, 1976

A young monk had been under a famous Master for but two years when the old Master died. When the successor was installed, all monks who wished to continue under him went to ask his permission. When it was young Kyogen's turn, the new Master who knew him well asked: " So here you are, brilliant, with outstanding capacities, knowing all the scriptures by heart! Are you sure you want and need to continue this rough and simple training?"

The young man, rather pleased that his capacities were known, indicated that he considered it a good thing to stay for a few more years. The new Master took him up: "Well, so you are pleased with yourself! You can quote the scriptures by heart - tell me then, where do you go after you have died?"

Kyogen was speechless. His immense scriptural knowledge raced through his mind, but he could not remember any relevant passage. Piqued in his pride and convinced that the answer must be in the scriptures, he asked permission to withdraw so as to look it up. But however he searched, he could not find it. The question gripped him, he was determined to find out, feeling that everything was at stake.

So he poured over the scriptures, forgot food and sleep, and within three days was worked up to such a state of tension that he could no longer bear it. Gaining an interview with the Master, he admitted that he could not find the answer in the scriptures, and could the Master please tell him.

The Master replied that it was for him to find out, for if he were told, it would rob him of his own insight. Kyogen in the urgency of his problem was beyond reasoning, and now demanded an answer. On the Master's stern refusal, he gripped him and threatened to kill him. "And do you think my dead body will give you an answer?" laughed the Master.

At that the tension in Kyogen broke; he realized what he had done. He apologized and left the monastery, convinced that he had lost all his chances in this life. He decided to spend his days humbly and harmlessly as a wandering monk, hoping that in his next life he would thus have better circumstances in which to continue his training.

After years of wandering all over the country, he came to the tomb of the Sixth Patriarch which he found derelict and uncared for. He settled down there, restoring the place, keeping the grounds, and looking after the occasional pilgrim. Thus he lived for years.

One day, he was sweeping and weeding the grounds as usual, and as he tipped out his barrowful of weeds and pebbles in the back yard, one pebble hit a bamboo trunk with a resounding clink. On hearing that sound he suddenly "awoke" and with the awakening, the answer to his old question was also clear to him.

He cleaned himself up, dressed in his full monk's robes, climbed the mountain behind the pagoda, and there prostrated himself in the direction of his monastery, thanking the Master that even under threat to his life he had not divulged an answer which would have robbed him of his own insight.