ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

大慧宗杲 Dahui Zonggao (1089–1163)

aka 妙喜 Miaoxi; posthumous title: Pujue 普覺 ”Universal Enlightenment”

(Rōmaji:) Daie Sōkō; aka Myōki; posthumous title: Fukaku

Dahui Zonggao 大慧宗杲 (1089–1163) was born in Xuancheng 宣城 in present-day Anwei; his family name was Xi 奚. He left home at the age of sixteen and entered Huiyun si 慧雲寺, a temple on Mount Dong 東, where he was ordained the following year. From early on, after reading the Yunmen guanglu 雲門廣錄 (Extensive record of Yunmen), he felt a special sense of relationship with Yunmen Wenyan 雲門文偃 (864–949). During an extensive pilgrimage Dahui studied under some of the important Caodong masters of his time, and, later, under Zhantang Wenzhun 湛堂文準 (1061–1115) of the Huanglong line of Linji Chan. Following Wenzhun's death, Dahui, on Wenzhun's deathbed advice, joined the assembly under Yuanwu Keqin at the temple Tianning Wanshou si 天寧萬壽寺 in the capital, Bianliang 汴梁, in modern Kaifeng. One day during a lecture Yuanwu said, “A monk asked Yunmen, ‘What is the place from which all Buddhas come?' Yunmen replied, ‘East Mountain walks on the water.' But if I were asked the same question I would simply say, ‘A fragrant breeze comes from the south, and in the palace a refreshing coolness stirs.” At these words Dahui was greatly enlightened. Dahui eventually became Yuanwu's dharma-heir and succeeded him as master of the monastery. His renown soon spread as far as the capital; in 1126 he was given a purple robe and an honorary name, Fori 佛日, by Lu Shun 呂舜 (n.d.), Minister of the Right.

When the Northern Song dynasty fell to the invading Jurchens in 1127, Dahui fled south and lived for a time with his teacher Yuanwu, then residing at the temple Zhenru yuan 眞如院 on Mount Yunju 雲居. Following Yuanwu's return to Sichuan in 1130, Dahui built a hermitage on the mountain where a Yunmen temple had formerly stood, and soon attracted a large following. He later moved to Yunmen an 雲門庵 in modern Fujian. In 1137, at the invitation of the prime minister, Zhang Jun 張浚 (a former student of Yuanwu), he went to Mount Jing 徑 near the city of Hangzhou 杭州. The assembly under him there is said to have numbered over two thousand. In 1141 Dahui was laicized for advocating armed resistance against the Jurchen invaders of the Northern Song. He retired to Hengyang 衡陽 in modern Hunan and there wrote his Zhengfayan zang 正法 眼藏 (Treasury of the true dharma eye). In 1150 he moved to Meiyang 梅陽 in modern Guangdong, then in the midst of a plague that eventually took the lives of half of his students. He devoted himself to helping the populace, remaining even after he was officially pardoned in 1155, until in 1158 he returned to Mount Jing on imperial command. There he soon attracted an assembly of about 1,700 students and received the patronage of Emperor Xiaozong 孝宗 (r. 1162–1189). He died in 1163, leaving ninety-four Dharma heirs. He was granted the posthumous title Chan Master Pujue 普覺禪師.

Two of the best-known aspects of Dahui's teaching are his opposition to what he called the “silent-illumination false Chan” 默照邪禪 of the Caodong school, and his promotion of “koan-introspecting Chan” 看話禪, which from his time on came to characterize the practice of the Linji school. His ongoing debate with the eminent Caodong master Hongzhi Zhengjue 宏智正覺 (1091–1157) on the subject of silent illumination versus koan work is famous in Zen circles.

The basic source for Dahui‘s life is Dahui pujue chanshi nianpu 大慧普覺禪師年谱 (Chronological biography of Dahui), compiled by his disciple, Zuyong 祖咏. There is also an inscription written by Zhang Jun 張浚, Dahui pujue chanshi taming 大慧普覺禪師塔銘 compiled by Zuyong, incl. in Dahui pujue chanshi yulu 大慧普覺禪師語錄 (T1998a = 47.811b-943a, esp 836-837).

Zen Dust 562, 408-410

The Zhengfayan zang 正法眼藏 (Treasury of the true dharma eye) is a collection of koans and dialogues compiled between 1147 and 1150 by Dahui Zonggao 大慧宗杲 (1089–1163); the sermon referred to is in fascicle 2 (x 67, no. 1309, 574b–c). The Zongmen liandeng huiyao 宗門聯燈會要 was compiled in 1183 by Huiweng Wuming 晦翁悟明 (n.d.), three generations after Dahui in the same line; the sermon is found in zh 20 (x 79: 173a).

Dahui Zonggao, the famous popularizer of koans in the Sung period of China, wrote a koan collection titled 正法眼藏 Zhengfa Yanzang (Treasury of the Correct Dharma Eye, W-G.: Cheng-fa yen-tsang, J.: Shōbōgenzō)

Dahui's Shōbōgenzō is composed of three scrolls prefaced by three short introductory pieces.

Upon arriving in China, Dogen Kigen first studied under Wuji Lepai, a disciple of Dahui, which is where he probably came into contact with Dahui's Shōbōgenzō.

Wikipedia: Writings

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dahui_ZonggaoOnly one work can be attributed to Dahui, a collection of koans entitled Cheng-fa yen-tsang 正法眼藏 [22] (The Storehouse of the True Dharma Eye, J. Shobogenzo)

Dahui also compiled the Ch'an-lin pao-hsun 禪林寶訓 (Treasured Teachings of the Ch'an Monastic Tradition), instructions of former Chan abbots about the virtues and ideals of monastic life, in collaboration with another monk, Ta-kuei. A disciple of Dahui, Tsu-yung, compiled a collection of Dahui's life and teaching called Ta-hui Pu-chueh Ch'an-shih nien-pu (Chronological Biography of Chan Master Ta-hui). The Chih-yueh lu, compiled by Chu Ju-chi of the Ming, also contains information on Dahui's teachings and is the basis of the J. C. Cleary translation Swampland Flowers, of which the majority is a collection of letters Dahui wrote to his students.

PDF: Ta-hui Tsung-kao and kung-an ch’an

by Chün-fang Yü

Journal of Chinese Philosophy, V. 6 (1979), pp. 211-235.

http://ccbs.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-JOCP/jc22069.htm

http://www.thezensite.com/ZenEssays/HistoricalZen/TaHui.htmlPDF: ‘Before the Empty Eon' versus ‘A Dog has no Buddha-nature':

Kung-an Use in the Ts'ao-tung Tradition and Ta-hui's Kung-an Introspection Ch'an

by Morten Schlütter

In: The Koan: Texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism, edited by Steven Heine and Dale S. Wright. New York, 2000, Chapter 6, pp. 168-199.

禪林寶訓 Chanlin baoxun / 禪門寶訓 Chanmen baoxun

(Rōmaji:) Zenrin hōkun / Zenmon hōkun

(English:) Precious Lessons from the Chan Schools / Treasured Instructions of the Chan Grove / Precious Admonishments from the Groves of Chan / Zen Gate Jeweled Instructions / Treasured Teachings of the Ch'an Monastic Tradition

early 12th cent.

Compiled by 妙喜 Miaoxi [Myōki] & 竹庵士珪 Zhu'an Shigui [Chikuan Shikei] of 龍翔 Longxiang [Ryūshō] (1083-1146)

Zhu'an Shigui of Longxiang (1083-1146) [Chu-an Shih-kuei of Lung-hsiang] Chikuan Shikei of Ryūshō. A Dharma heir of Foyan Qingyuan, who was a student of Wuzu Fayan. Zhu'an is also known as Kushan [Drum Mountain], where he later taught and which was a center of Buddhist studies in Dogen’s time. Zhu'an, who is praised by Dogen for his literary expression of Dharma, compiled a collection of stories, "Zen Gate Jeweled Instructions," together with Dahui.

late 12th cent. expanded by 徑山 Jingshan (d.u) [Keizan], published in 1368

first published in Japan in 1279

PDF: Zen Lessons

Translated by Thomas Cleary

This is a remarkable text. Chinese Ch'an Buddhism, better known in the West by its Japanese name of Zen, is a subtle fusion of confucianism, Daoism and early Indian Buddhism. Its recorded writings, although distinctly Buddhist in nature, are nevertheless often presented in a structure similar to that found in the Confucian book known as The Analects (Lunyu). Zen Lessons is no exception to this observation. The original Chinese text that Zen Lessons is drawn from is known as the Chanmen Baoxun (or, 'Chanlin Baoxun'). This translates as 'Precious Lessons of the Ch'an Schools', and dates from the early Song Dynasty (960-1279AD). This text was compiled in the early twelfth century by Ch'an masters Dahui and Zhu-an, bringing together in one place, a compendium of private dialogue, discussion and letters, covering a broad range of questions regardimg the political, social and philosophical issues faced by Ch'an practitioners during the early Song.

This Thomas Cleary translation offers the Chanmen Baoxun in an English language format that presents the work in 217 short chapters that range in constitution from anything between 5 or 6 lines, to 5 or 6 paragraphs. The text is comprised of material drawn from sources dated to around the early to middle Song Dynasty - the time of Dahui and Zhu-an's existence. The first Ch'an master quoted in the text is called Mingjiao, and the last Ch'an master to be featured is called Jiantang. Interestingly, one of the compilers - Dahui (1089-1163) - is mentioned in the body of the text, by the name 'Miaoxi'. Dahui has subsequently become famous for another work attributed to him, namely that of a collection of letters of Ch'an instruction, written by himself to many lay and monastic practitioners of Ch'an, thus demonstrating that an enlightened master can free the Mind with words either in person, or through the written word. JC Cleary has translated this work into English, entitled 'Swampland Flowers. JC Cleary is, of course, the brother of Thomas Cleary, and both have used their considerable translation skills to render The Blue Cliff Record (Biyan Lu) into English. This is significant, as the Ch'an master responsible for this excellent work - Yuanwu (1063-1135) - is also mentioned in Zen Lessons.

This text and translation of Zen Lessons is something of a gem and is highly recommended for study by students of both Ch'an and Zen. The song Dynasty Ch'an masters were very concerned by the lack of standards even then, and how the perceived quality of Ch'an students had diminished considerably since the time of the Tang Dynasty (618-907). There is a sense of urgency in the presented wisdom. An urgency that fits well in today's age of corruption, war and injustice.

正法眼藏 Zhengfa yanzang

(Rōmaji:) Daie Sōkō: Shōbōgenzō

(English:) The Storehouse of the True Dharma Eye / Treasury of the Correct Dharma Eye

(Magyar:) Ta-huj Cung-kao: Az igaz törvény szemefénye

A collection of 668 koans and dialogues compiled between 1147 and 1150.

PDF: Treasury of the eye of true teaching Volume 1 > PDF

translated by Thomas Cleary

2017

PDF: Treasury of the eye of true teaching Volume 2 > PDF

translated by Thomas Cleary

2017

PDF: Treasury of the eye of true teaching: classic stories, dialogues, and poems of the Chan tradition

translated by Thomas Cleary

Boulder, 2022.

大慧普覺禪師語錄 Dahui Pujue chanshi yulu

(Rōmaji:) Daie Fukaku zenji goroku

(English:) Recorded Sayings of Chan Master Dahui Pujue

大慧普覺禪師宗門武庫 Dahui Pujue chanshi zongmen wuku

(Rōmaji:) Daie Fukaku zenji shūmon muko

(English:) Chan Master Dahui Pujue's Arsenal of the Tradition

大慧普覺禪師書 Dahui Pujue chanshi shu

(Rōmaji:) Daie Fukaku zenji sho

(English:) Chan Master Dahui Pujue's Letters

PDF: Swampland Flowers: The Letters and Lectures of Zen Master Ta Hui

Tr. by J. Christopher Cleary

[Selections from 瞿汝稷 Qu Ruji's (1548-1610) 指月錄 Zhiyue lu / Records of Pointing at the Moon, Vols. 31-32.]

New York: Grove Press, 1977, Shambhala Publications, 2006, 176 p.

Ch'an master Ta Hui (1088-1163) lived during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). His name 'Ta Hui' was bestowed upon him posthumously by the emperor Hsia Tsung, and means 'Great Wisdom'. Ta Hui was the Dharma heir of Ch'an master Yuan Wu of the Lin Chi lineage of Ch'an - Yuan Wu is famous for compiling the Blue Cliff Record (Pi Yen Lu), a collection of Ch'an dialogues attributed to Ch'an masters throughout the ages. This collection is the English translation of the Chinese text entitled 'Chih Yueh Lu' (Records of Pointing at the Moon), volumes 31 and 32. As ancient China had a postal service, Ta Hui was able to keep in-touch with Ch'an students from around China.

The author-translator - JC Cleary - dedicates this book to his brother - Thomas Cleary - acknowledging that without his brothers encouragement, he would not have read or translated Ta Hui's words. The book is simple and concise. The material contained therein, carries the impression that it was written solely for the benefit of the reader, such is Ta Hui's wisdom and Cleary's ability. The book is separated into five sections:Forward.

About the Author.

Translator's Introduction.

Ta Hui's Letters.

Lineage and Names.Although Ta Hui inherited the Lin Chi Ch'an teaching, he did not discriminate between lineages. Indeed, the great Ts'ao-Tung Ch'an lineage holder - Hung Chih - a contemporary of Ta Hui, left Ta Hui in charge of his affairs when he died. Ta Hui wrote the following poem:

Birth is thus

Death is thus

Verse or no verse

What is the fuss?

He let the brush slip from his hand, and peacefully passed away. His students collected his teachings together, which are presented in this book. A delightful translation which all Ch'an and Zen students should earnestly study.

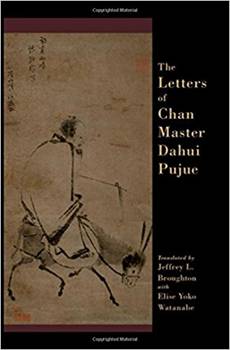

PDF: The Letters of Chan Master Dahui Pujue

Jeffrey L. Broughton, Elise Yoko Watanabe

Translator: Jeffrey L. Broughton

Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, August 2017. 408 p.

Review by Jason Protass, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Brown University

Broughton and Watanabe's The Letters of Chan Master Dahui Pujue (hereafter “Broughton” and Letters) is the first complete English rendition of a collection of Chinese letters that circulated across East Asia. The epistles by Dahui (1089-1163) are one of the world's richest religious documents, containing profound discussions on faith, the importance of doubt, paradoxes of spiritual effort, and messages of transformation. The translators' sophisticated textual apparatus, including footnotes that selectively translate from historical Korean and Japanese commentaries, makes this book indispensable for future studies of Dahui's letters.

Dahui was heralded by later traditions as the genius innovator of the kanhua meditative technique (Jap. kanna zen; K. kanhwa Sŏn) of examining the “head word” of a gong'an (“public case,” Jap. kōan). This kanhua practice as taught in the Letters is the root of modern popular understanding of “Zen koans” as riddles to disrupt discursive thought. Dahui, kanhua , and gong'an have each been frequent topics of scholarship. As Miriam Levering noted in her PhD dissertation (Harvard, 1978), Dahui's epistolary teachings have an enduring allure because they were addressed to the concerns of lay people.

Excerpts from Dahui's epistles were previously translated by Christopher Cleary in Swampland Flowers (Grove Press, 1977). Cleary worked from the text of Zhi yue lu 指月錄 (“A Record of Fingers Pointing at the Moon”), a late 16th century anthology whose compiler abridged Dahui's letters to their pith. One of the strengths of the Broughton translation was the choice to follow a complete early Gozan edition. Cleary's translation, despite the lack of a scholarly apparatus and the interesting choice of using an abridged Ming recension, is accessible, fluent, and generally accurate. By comparison, Broughton's style is terse and closely follows Chinese idioms.

The most original and likely enduring contributions of this book are its robust footnotes emphasizing historical exegeses of the epistles. The exegetical tradition is indispensable for interpreting thorny passages of epistolary Late Middle Chinese. The translators closely engage two Korean commentaries used in Sŏn seminaries since the 18th century—one by Chin'gak Hyesim (1178-1234) and an anonymous lexicon—in addition to one pre-modern Japanese commentary, two early modern Japanese commentaries, and several contemporary Japanese translations. Foremost in significance for the translators is perhaps Daie Fukaku zenji sho kōrōju 大慧普覚禅師書栲栳珠 (hereafter Kōrōju) produced by Japanese monk Mujaku Dōchū 無著道忠 (1653-1745), an erudite Zen monk and an expert on Song and Yuan era Chan. The translators present persuasive arguments when choosing to deviate from Mujaku's interpretations. Araki Kengo's authoritative 1969 annotated modern Japanese translation also relied on Kōrōju . The translators document their divergences from Araki as well. The result is an original work of interpretation that is profoundly informed by the Korean and Japanese traditions of exegesis and practice. This is a great achievement.

Broughton's emphasis on Korean and Japanese receptions situates the Letters more within the field of Zen Studies than within the study of Chinese religions. As a result, there is more work to be done to study how Chan epistles participated in the broader culture of Chinese letters. Natasha Heller has already provided a foundational essay on monastic letters during the Southern Song and Yuan dynasties, “Halves and Holes: Collections, Networks, and Epistolary Practices of Chan Monks” (in A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture , Brill, 2015). Also related is Huang Qijiang's Bei Song Huanglong Huinan Chanshi sanyao 北宋黃龍慧南禪師三鑰 (Taibei: Taiwan xuesheng shuju, 2015), which meticulously analyzes another set of Song era epistles with transnational circulation.

Dahui often crafted new ways of speaking while simultaneously engaging the expressions of earlier Chan masters. Perhaps it is fitting then that Broughton has experimented with English expressions, and at times deviated from well-tried translations. Some neologisms are clever. For example, an explanation of Dahui's idiosyncratic use of the verb guandai 管帶 is developed based on a gloss from Mujaku's Kōrōju . This yields the unusual “to continuously ‘engird mind' ” (18) as a description of wrong-headed effortful concentration of the mind. This mental girdle plays with the etymology of the second character in guandai : dai is literally to fasten or to belt on. (Rather than “engirding mind” I might have preferred “girding the mind,” which would resonate with the dated but idiomatic “gird the soul.”) Elsewhere, rendering mozhao 默照 as “silence-as-illumination,” well known to both scholarly and practitioner communities as “silent illumination,” recasts the term in the pejorative way Dahui himself treated mozhao . Other neologisms may distract. The genre of texts known as yulu is familiar as “recorded sayings.” The authors' preferred “sayings record” seems to introduce a distinction without a difference.

Letters begins with an introductory essay by Broughton that foregrounds compelling speculation about the centrality of the layman Huang Wenchang as “editor-in-chief.” (6) The authors also contend that Dahui may have taught huatou meditation practice to lay people exclusively. With negligible exceptions, they claim, there is no evidence that Dahui recommended huatou to his monastic disciples. (10-12) If correct, the implications would be that later traditions adapted a lay practice into a monastic one—contra Dahui's own praxis.

One brief correction. It is misleading to assert that Dahui was abbot of “the foremost of the official ‘Five-Mountains' Chan monasteries” (5-6) because the Five Mountains patronage system was only established in the first decades of the 13th century, after Dahui's life.

Despite such minor quibbles and stylistic preferences, this book is a wonderful resource to all who would read Dahui's epistles. The inclusion of lucid translations from multiple historical commentaries—a rich exegetical apparatus—is a great contribution. We are all indebted to the translators' work.

Dahui Zonggao (1089–1163):

PDF: The Image Created by His Stories about Himself and by His Teaching Style

by Miriam Levering

In: Zen Masters, eds. Steven Heine and Dale Wright, New York, 2010, Chapter 4

This chapter focuses on the image of Zen (Chan) Master Dahui Zonggao (1089–1163) presented in the Dahui's Letters (Dahui shu) and the Recorded Sayings of Chan Master Dahui Pujue (Dahui Pujue Chanshi yulu) . Dahui Zonggao permanently transformed Chinese Chan Buddhism. First, he was strongly influential in blending Chan with Huayan Buddhist philosophy; second and most important, Dahui devised a meditation method that has been fundamental to Chan practice ever since, the kan huatou method. Dahui Zonggao's influence has been vast, and a considerable part of his lasting attraction and popularity can be attributed to the image of his forceful, fearless and caring personality and teaching style found in his records. It is high time that we examined these texts in terms of the image of Dahui, his insights and ideas, his personality, and his teaching methods, for it is through this image that his influence has been felt.

Levering, Miriam

Ph.D. Dissertation:

PDF: Ch'an Enlightenment for Laymen: Ta-hui and the New Religious Culture of the Sung

1978, Harvard University. Prof. Masatoshi Nagatomi, adviser. Awarded "Distinction".PDF: "Ta-hui and Lay Buddhists: Ch'an Sermons on Death,"

Buddhist and Taoist Practice in Medieval Chinese Society (vol. II of Buddhist and

Taoist Studies series). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1987, pp. 181-206.

https://www.academia.edu/8902305/Chan_Enlightenment_for_Laymen_Ta-hui_Tsung-kao_Dahui_Zongao_1089-1163_and_Chan_Sermons_on_DeathDahui Zonggao (1089-1163): The Awakening and Career of a Religious Genius and the Image these Created

May 14, 2013

http://elijah-interfaith.org/sharing-wisdom/dahui-zonggao-1089-1163-the-awakening-and-career-of-a-religious-genius-and-the-image-these-createdA Monk's Literary Education: Dahui's Friendship with Juefan Huihong;

Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal, No.13.2 (May 2000) pp. 369–384

http://buddhism.lib.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-BJ001/93610.htm

PDF: "Dahui Zonggao and Zhang Shangying: The Importance of a Scholar in the Education of a Song Chan Master."

The Journal of Sung-Yuan Studies 30 (2000), pp. 115-139.

https://www.academia.edu/8570942/Dahui_Zonggao_and_Zhang_Shangying_in_the_late_Northern_Song_dynastyPDF: Was There Religious Autobiography in China before the Thirteenth Century?—The Ch'an Master Ta-hui Tsung-kao (1089–1163) as Autobiographer,

Journal of Chinese Religions, 2002, 30: 97–119."Miao-tao and her Teacher Ta-hui," Chapter 6 in Buddhism in the Sung Dynasty,

edited by Peter N. Gregory and Daniel A. Getz, Jr.

(Kuroda Institute Studies in East Asian Buddhism 13, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press), 1999, pp. 188-219.

Selected Sayings of Master Daie Soko

[大慧宗杲 Dahui Zonggao,1089–1163] with Myokyo-ni's comments

Zen Traces, Volume 33 Number 4 September 2011

THE TEXT

‘‘If people who study transcendent wisdom abandon this expedience and go

along with passions, they will certainly be controlled by the demons of

delusion. And while yielding to sense objects to impose theories, and say

that affliction is itself enlightenment, and ignorance is itself great wisdom;

acting in terms of existence with every step, while talking of emptiness with

each breath. Without admonishing oneself for being dragged along by the

power of habitual action, to go on and teach others to deny cause and effect,

the vicious poison of misguided delusion has entered the guts of people who

act like this. They want to escape from passion, but it is like trying to put

out the fire by pouring on oil – are they not to be pitied? Only having

penetrated through can you say that affliction is itself enlightenment, and

ignorance is identical to great wisdom. Within the wondrous heart of the

original, vast quiescence which is pure, clear, perfect illumination there is

not a single thing that can cause obstruction. It is like the emptiness of

space, even the word Buddha is alien to it, to say nothing of there still being

passions or afflictions as the opposite. This affair is like the bright sun in

the blue sky shining clearly, changeless and motionless, without diminishing

or increasing, it shines everywhere in the daily activities of everyone,

appearing in everything. Though you try to grasp it, you cannot get it;

though you try to abandon it, it always remains; it is vast and unobstructed,

utterly empty like a gourd floating on water, it cannot be reined in, or held

down. Since ancient times since when good people of the path have attained

this, they have appeared and disappeared in the sea of birth and death, able

to use it fully. There is no deficit or surplus, like cutting up sandalwood,

each piece is it.”VEN. MYOKYO-NI’S COMMENTS

‘If people who study transcendent wisdom’, Prajna that is, ‘abandon this

expedience’, we heard last time what these expedients are – not to give oneself

airs, not to talk greatly, not to use language that is difficult to understand, to be

quite ordinary, skilful means which fit, and this expedience within the skilful

means are the important thing. If therefore, those ‘who study transcendent wisdom

abandon these expedient means’ – one can very easily run off at the mouth, having

read a little bit, thinking one has grasped it, and talking one’s head off as if one

knew what it was all about, not even giving oneself airs, quite running away by

itself.

I remember vividly, in the mid-fifties in father’s Zen class, after the class

was over we were reading whatever book was available, and then we would go to

the nearest coffee house, or tea-room as it was then, and then we would talk and

talk of how we understood it, and how we saw it, and then we would be thrown out

because it was closing time, and we would go to the next one which was open a bit

longer. And we couldn’t contain ourselves. Well, this is out of ignorance, not

only just wanting to show what one knows.

But, ‘If people who study transcendent wisdom abandon this expedience’, at

that time nobody knew any better and it didn’t come to much anyway, but

nowadays it is a little bit different and at the time when Master Daie was talking

there were, and there have always been, those who really said, ‘this is how it is’,

and gave great examples and didn’t really know what it was all about. So, ‘If

people who study transcendent wisdom abandon this expedience and go along with

passions, they will certainly be controlled by the demons of delusion.’ If we go

along with passions, when the Fires flare up, when the volcanoes erupt, then we

certainly are controlled by the demons of delusion. Because then, whatever comes

up in that eruption, we take for real, and we believe it and we believe it with that

same fierceness with which the eruption comes.

There is an excellent gauge which might be worthwhile if you haven’t done

it, and that is to get yourself a tape recorder – everybody has one nowadays – and

either your spouse, or a very good friend, anyway someone who knows all the

weaknesses that we have. And then tell them what the thing is about, and start

talking about it, and you get a bit niggled. And you get just to the point where you

always react, and let the tape recorder run, set for quarter of an hour, and then it

has to shut itself off, you can’t do it anymore. The other, no doubt, by that time is

also a little bit high, but it clicks off. And then for a week you let it stand there.

And then you listen to that tape – you will not believe it, when you hear your own

voice suddenly rising higher and higher, and with unctuous conviction the greatest

platitudes come out. It is one of the more sobering experiences, and if you haven’t

done it yet, I strongly suggest you do it. That is when the demons of delusion run

away with us. ‘And while yielding to sense objects’, being carried away by sense

objects, and please remember that these are not just outside objects, but also

mental objects – yielding to these, being carried away by them, and yet

nevertheless in spite of them, or using them, to ‘impose theories, and say’ ‘it is

this, I know it!’, or what I know and have read and understood, that ‘affliction is

enlightenment, and ignorance is itself wisdom’, that is what it says in some of the

books, ‘I have read it myself!’ And act therefore, also, according to that with every

step, and yet ‘talking of emptiness with every breath.’ ‘Without admonishing

oneself for being dragged along by the power of habitual action’. As we are

dragged along by the power of habitual action we can’t keep the demons of

delusion down, we’ve never tried it.

And so this is where we need the practice, where we need the strength to

really hold together, rather than going on and talking to ‘others, to deny cause and

effect.’ ‘The vicious poison of misguided delusion has entered the guts of people

who act like this.’ ‘The vicious poison’, he calls it, ‘of misguided delusion.’ With

no training and no framework, the whole thing explodes. And yet, ‘They’, such

people, ‘want to escape from passion’, but how can you escape from the passions if

you allow them to carry you away again and again? ‘It is like trying to put out the

fire by pouring on oil.’ What happens if there is a fire and you pour oil on it?

‘Aren’t such people to be pitied?’ This, and Master Daie really lays it on, is a

careful warning, not only in our talking, but in our thinking that we have to keep to

the practice, to the framework and not continuously allow our own ideas, our own

passions, our own weaknesses, to obstruct and rule us. ‘Because,’ says Master

Daie, ‘only having penetrated all the way through can you say that affliction is

itself enlightenment, and ignorance is identical to great wisdom.’ ‘Only having

penetrated all the way through.’ Although it is true, if you tell it to somebody else

then it is likely to be another snare. This is why it is so important that the talk

matches and is on the right level.

If you talk to a child who is learning his multiplication tables – I don’t know

whether people still learn multiplication tables nowadays, or whether they go

straight on the computer, I don’t know – but in my time at least we had to learn

multiplication tables, and then more and more mathematics, and when we came to

integral calculus, it was a natural progression; but if you talk about integral

calculus to a child who is just learning multiplication tables, he will think you are

off your rocker, or that there is something magnificent, magical about it. And so

this matching is an important thing. ‘Only having penetrated all the way through

can you say that affliction is itself enlightenment, and ignorance is identical to

great wisdom.’ And it is not only in talking, it is also in our reading; having just

read that affliction is itself enlightenment, ignorance is identical to great wisdom,

‘Now I know! Now I’ll have no more trouble!’, and then I wonder where the

trouble and obstructions come from when, after all, I know it. I have only ensnared

myself even more.

But Master Daie tells us, ‘Within the wondrous heart of the original, vast

quiescence’, that wide, open emptiness, ‘which is pure, clear, perfect illumination,

there is not a single thing that can cause obstruction.’ You remember the sixth

Patriarch, ‘Before thinking of good and bad’, before thinking, when there is

nothing – we must not misunderstand that nothing either, it is not that there is

nothing, but there is no obstruction because there is just one, Master Daie calls it

‘pure, clear, perfect illumination,’ and being one, and having become one with it,

there is not a single thing that can cause obstruction. It is like the emptiness of

space, and even the word Buddha is something alien to this vast emptiness, like

space. The word Buddha doesn’t belong to it. That’s only made up by us. To say

nothing of there still being passions. How can there be passions or afflictions as

the opposite of that vast quietness. There is just nothing.

And Master Daie then continues, ‘This affair is like the bright sun in the

blue sky, shining clearly, changeless and motionless, without diminishing or

increasing.’ Like the bright sun in the blue sky, shining clearly. It does not

change, it does not hop about. It shines without diminishing or increasing, and it

shines everywhere. It does not shine more on this, or less on that. It doesn’t even

want to shine. Shining is its nature. And it shines everywhere in the daily

activities of everyone.

Master Daie is very careful in really trying to point the finger towards it. ‘It

shines everywhere, in the daily activities of everyone’. It cannot be hidden. The

Sixth Patriarch again said, ‘The peasant uses it all day long, but is not aware of it.’

The daily activities of everyone, whatever we are doing, it shines through it, and

appearing in everything, like the sun shining clearly. Though you try to grasp it, to

see it, to hold it, to look at it, you cannot get it. The knife that cuts but cannot cut

itself, the eye that sees but cannot see itself. And this is the delusion of I, thinking

that it can grasp it, and look at it as if it was something extra, something separate.

But that - if you want to call it the True Face, because we are mostly concerned

with that - cannot be seen, it cannot be grasped, but it works. You cannot get it.

And though you try to abandon it - this is the other side of it - it always remains.

You cannot see it, and you cannot get rid of it either. It is in the oneness, in the

total union with it, and the functioning in that union, which takes the body in as

well as the mind and the thought and the heart and the whole lot. But it has no I

with it, as observer.

You can learn typing exactly - with which finger you press which key - you

can have it perfectly in your head. And when you are then put in front of a

typewriter, will you be able to type? No, because you haven’t got that physical

skill, which needs to be trained. And when really used to it there is a oneness with

it, you don’t need to think about it any more. As long as you have to think about it,

it is not yet truly at one. And Master Daie uses the old analogy: ‘Like a gourd

floating on water, it cannot be reined in or held down. Since ancient times when

good people of the Path have attained this, they have appeared and disappeared in

the sea of birth and death, able to use it fully.’ Since ancient times when good

people of the Path have attained this, this insight, this oneness with it and acting

with it, within it in response to the situation - because there is no I that wants to do

this, that, and the other - then they have appeared and disappeared in the sea of

birth and death, able to use it fully. Able to use it fully, smoothly, in response to

the situation, in obedience to the situation, and to the benefit of all concerned.

The other day I had a letter from somebody who has been doing the practice

for quite some time. And she is in a job where the money was running out, and

there was great talk about what could be done, and how the employment could

continue, and there were very heated opinions. And she said she suddenly realised

that it was no good having her own opinion on that, that everybody was having

them, and she was talking to the manager, and suddenly saw his point so

completely that she could only nod. And at that moment, he looked at her and

said, “Yes, but it could go in a much simpler way,” and the whole situation defused

itself.

It’s very important that we realise that this unity is not a conking out, but is

the full smooth going with the situation, and it has a habit of defusing situations,

because it touches everything.

Disappearing and appearing in the sea of birth and death, able to use it fully.

There is no deficit or surplus in that use. Master Daie compares it to ‘cutting up

sandalwood, each piece is it.’ Like cutting up sandalwood. You cannot increase it,

you cannot decrease it, it just is, neither more nor less, it just is. In everything, in

every action. In cutting a piece of bread, in lifting a finger, in whatever it is, in

response to the demands of the situation. Like cutting up sandalwood, each piece

is it. And when it comes to that, then the thing works together in harmony. And

this is where the Buddha’s teaching points us, to this harmonious working

together. Can we please take this to heart and ponder it down in the zendo?

![]()

PDF: Keller Mirella: A huatou 話頭 chan buddhista meditációra vonatkozó fogalom vizsgálata X–XII. századi szövegekben

Távol-keleti Tanulmányok, 15/1 (2023): 99–116.