ZEN IRODALOM ZEN LITERATURE

« Zen index

« Home

十牛圖 Shiniu tu

[Jūgyūzu]

The Ten Bull Pictures

General Foreword and Introductions by Ciyuan 慈遠

[Jion]

First verses by 廓庵則和尚

Kuoan Ze heshang = 廓庵師遠

Kuoan Shiyuan [Kakuan Shien]

Second verses by 石皷夷和尚

= 石鼓夷和尚

Shigu Yi heshang = 石鼓希夷

Shigu Xiyi [Sekiko Kii]

Third verses by 壞衲璉和尚

= 壊納璉和尚

Huaina Lian heshang = 壞衲大璉

Huaina Dalian [Kaidō Tairin]

Translated by Myokyo-ni (妙教尼 Myōkyō-ni, born Irmgard

Schloegl; 1921-2007)

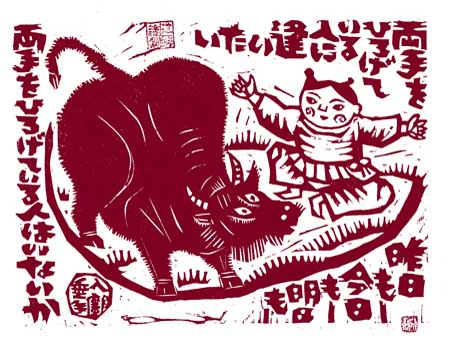

Illustrations by 森貘郎 Mori Bakurō (1942-)

Gentling

the Bull: The Ten Bull Pictures: A Spiritual Journey by Myokyo-ni (Irmgard

Schloegl), Zen Centre, London, 1988. (facsimile): Tuttle Publishing, 1996. Kindle Edition: http://www.amazon.com/kindle/dp/B005R18D38

Myokyo-ni (born Irmgard Schloegl; January 29, 1921 - March 29, 2007) was a

Rinzai Zen Buddhist nun, who directed the Zen center Shobo-an in London. The Ten

Ox-Herding Pictures, also known as the Ten Bull Pictures, are believed to have

been drawn by Kakuan, a twelfth century Chinese Zen master, but became widely

used as a means of Zen study in fifteenth-century Japan. They are used in

formal Zen training to this day to show the stages of one's realization of

enlightenment. Each of the ten pictures is presented here with a preface and

general foreword to the series by Chi-Yuan, a monk in the direct line of

Kakuan. Myokyo-ni provides a lucid introduction that sets the pictures in their

historical context and shows their relevance to modern Zen training. In her own

comments on each picture, she discusses how they are representative of our own

search for "oneness"- spiritual fulfillment.

Foreword

Chi-Yuan wrote

this Foreword to

Master Kuo-an's [Kakuan]

Ten Bull Pictures

十牛図(じゅうぎゅうず)

The real source of all the Buddhas is the original nature of sentient beings. Through delusion we fall into the Three Worlds, through awakening we suddenly leap free of the Four Modes of Being. Therefore there is something for the Buddhas to do and something for people to carry out. In compassion the old sage set up various ways to teach his disciples sometimes the complete and sometimes the partial truth, leading them suddenly or gradually from the shallow to the profound, from the coarse to the subtle. Finally one of his disciples responded with a smile. He was foremost in the practice of letting go, with eyes like blue lotus. Since then the treasure of the true Dharma Eye has spread everywhere, and has reached even our country.

One who has attained to the core of this truth soars without trace like a bird above all laws and norms. But one attached to the manifold things is caught in speech and misled by words; he is like the clever turtle that tried to wipe out its footprints with its tail – thus making them more conspicuous.

Long ago, Master Ching-chu [Seikyo], aware of the different abilities of sentient beings, adjusted his teachings to the capacities of his disciples and prescribed remedies according to their respective illnesses. To this purpose he drew pictures of gentling a bull. In these, with the bull becoming gradually white, he shows first the growing development of the disciple, and then, at the stage of the spotless purity of the bull, how the ability of the trainee has ripened. Finally, with both man and bull vanished, he illustrates the forgetting of heart and surroundings [I and things].

Though at this stage insight has already pierced through to the root, within the surrounding circumstances something remains that is not yet clear. Here those of shallow root ability tend to fall into erroneous doubt, while students whose understanding is as yet only small or medium, become bewildered and wonder whether they have fallen into empty emptiness, or conversely whether they have been snared by the view of seeming eternalism.

Kuo-an [Kakuan] also composed a poem for each picture. Like Master Ching-chu [Seikyo] before him, he put his whole heart into the execution of these drawings. The ten beautiful poems both shine into and are reflected by each other.

Kuo-an's [Kakuan] Bull Pictures start with the missing of the bull and lead to the return into the origin. These poems fit the differing abilities and needs of those in training like food and drink appease hunger and thirst. With them as guides, I, Chi-yuan, have probed into the profound meaning and extracted hidden subtleties - like a jelly-fish lends its eye to the little shrimps that shelter beneath it.

From 'Searching for the Bull to 'Entering the Market Place', like attempting to draw a square circle, my prefaces try to describe the indescribable, thus needlessly disturbing the peace of men. There is no heart to look for, even less so a bull! How strange the one who here enters the market place! Unless the heart of the ancient masters has been matched in its very depth, the resulting wrong will spread to the successors. Truly my own Foreword has come from the depth of my heart.

十牛図〈一〉尋牛(じんぎゅう)

I - SEARCHING FOR THE BULL

The search for what? The bull has never been missing. But without knowing

it the herdsman estranged himself from himself and so the bull became lost

in the dust. The home mountains recede ever further, and suddenly the herdsman

finds himself on entangled paths. Lust for gain and fear of loss flare up

like a conflagration, and views of right and wrong oppose each other like

spears on a battlefield.

POEMS

1

Alone in a vast wilderness, the herdsman searches for his bull in the tall

grass.

Wide flows the river, far range the mountains, and ever deeper into the

wilderness goes the path.

Wherever he seeks, he can find no trace, no clue. Exhausted and in despair,

As the evening darkens he hears only the crickets in the maples.

2

Looking only into the distance, the searching herdsman rushes along.

Does he know his feet are already deep in the swampy morass?

How often, in the fragrant grasses under the setting sun,

Has he hummed Hsin-feng [Shinpo], the Song of the Herdsman, in vain?

3

There are no traces in the origin. Where then to search?

Gone astray, he stumbles about in dense fog and tangled growth.

Though unwitting, grasping the nose of the bull, he already returns as a guest,

Yet under the trees by the edge of the water, how sad is his song.

十牛図〈二〉見跡(けんせき)

II - FINDING THE TRACES

Reading the Sutras and listening to the teachings, the herdsman had an inkling

of their message and meaning. He has discovered the traces. Now he knows that

however varied and manifold, yet all things are of the one gold, and that

his own nature does not differ from that of any other. But he cannot yet distinguish

between what is genuine and what fake, still less between the true and false.

He can thus not enter the gate, and only provisionally can it be said that

he has found the traces

POEMS

1

Under the trees by the water, the bull's traces run here and there.

Has the herdsman found the way through the high, scented grass?

However far the bull now may run, even up the far mountains,

With a nose reaching up to the sky, he cannot hide himself any longer.

2

wrong paths cross where the dead tree stands by the rock.

Restlessly running round and round, in his little nest of grass,

Does he know his own error? In his search, just when his feet follow the

traces,

He has passed the bull by and has let him escape.

3

Many have searched for the bull but few ever saw him.

Up north in the mountains or down in the south, did he find his bull?

The One Way of light and dark along which all come and go;

Should the herdsman find himself on that Way he need not look further.

十牛図〈三〉見牛(けんぎゅう)

III - FINDING THE BULL

The herdsman recoils startled at hearing the voice and that instant sees into

the origin. The six senses are quieted in peaceful harmony with the origin.

Revealed, the bull in his entirety now pervades all activities of the herdsman,

present as inseparably as is salt in sea water, or glue in paint. When the

herdsman opens his eyes wide and looks, he sees nothing but himself.

POEMS

1

Suddenly a bush warbler trills high in the tree top.

The sun shines warm, and in the light breeze the willows on the water's edge

show their new green.

There is no longer a place where the bull can hide himself;

No painter can capture that magnificent head with its soaring horns!

2

On seeing the bull and hearing his bellow,

Tai-sung, the painter, surpassed his craft.

Accurately he pictured the heart-bull from head to tail,

And yet, on carefully looking, he is not quite complete.

3

Having pushed his face right against the bull's nose,

He no longer needs to follow the bellowing. This bull is neither white nor

blue.

Quietly nodding, the herdsman smiles to himself.

Such landscape cannot be caught in a picture!

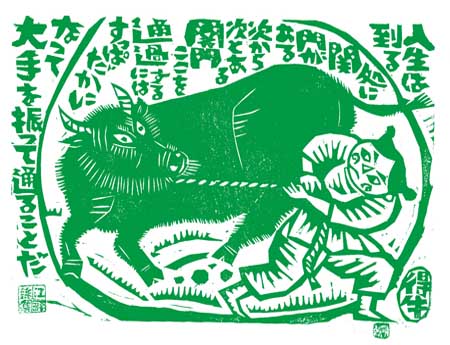

十牛図〈四〉得牛(とくぎゅう)

IV - CATCHING THE BULL

For the first time today he encountered the bull that for so long had been

hiding in the wilderness. But his pleasantly familiar wilderness still attracts

the bull strongly. He yearns for the sweet-smelling grass and is difficult

to hold. Stubborn self-will rages in him and wild animal-nature rules him.

If the herdsman wants to make the bull really gentle, he must discipline him

with the whip.

POEMS

1

With great effort the herdsman succeeded in catching the bull.

But stubborn, wilful and strong, this bull is not easily gentled!

At times he breaks out and climbs up to the high plains,

Or rushes down into foggy marshlands to hide himself there.

2

Hold the rein tight and do not let go.

Many of the subtlest faults are not yet up-rooted.

No matter how gently the herdsman pulls at the nose-rope,

The bull may still rear and try to bolt back to the wild.

3

Though caught where the sweet-scented grass reaches sky-high,

The herdsman must not let go of the rein tied to the bull's nose.

Though the way home beckons clearly already,

The herdsman must often halt with the bull, by the blue stream or on the green

mountain.

十牛図〈五〉牧牛(ぼくぎゅう)

V - GENTLING THE BULL

If but one thought arises, then another and another follows in an endless

round. Through awakening, everything becomes truth; through delusion, it becomes

error. Things do not come into being depending on circumstances but arise

from the herdsman's own heart. Hold the rein tight and do not allow any wavering.

POEMS

1

Not for a moment may the herdsman drop whip and rein,

Or the bull would break free and stampede into the dust.

But once patiently trained and made truly gentle,

He follows the herdsman without halter or chain.

2

Now the bull may saunter through the hill forests,

Or else walk the much travelled roads, covered in dust.

Never will he touch fodder from another man's meadow.

Coming or going requires no effort - the bull quietly carries the man.

3

In patient training the bull got used to the herdsman and is truly gentle.

Should he now walk right into dust, he no longer gets dirty.

Long and patient gentling! In one sudden plunge the herdsman has won his whole

fortune.

Under the trees, others encounter his mighty laugh.

十牛図〈六〉騎牛帰家(きぎゅうきか)

VI - RETURNING HOME ON THE BACK OF THE BULL

Now the struggle is over! Gain and loss, too, have fallen away. The herdsman

sings an old folk song or plays a nursery tune on his flute. Looking up into

the blue sky, he rides along on the back of the bull. If someone calls after

him, he does not look back; nor will he stop if tugged on the sleeve.

POEMS

1

Without haste or hurry, the herdsman rides home on the back of the bull.

Far through the evening mist carries the sound of his flute,

Note for note, tune for tune, all carry this boundless mood;

Hearing it, no need to ask how the herdsman feels.

2

Pointing ahead towards the dyke where his home is,

He appears out of mist and fog, playing his flute.

Then suddenly the tune changes to the song of return.

Not even Bai-ya's masterpieces can compare with this song.

3

In bamboo hat and straw coat he rides home through the evening mist,

Sitting back to front on the bull, with joy in his heart.

Step by step along in the cool, gentle breeze,

The bull no longer looks at the once irresistible grass.

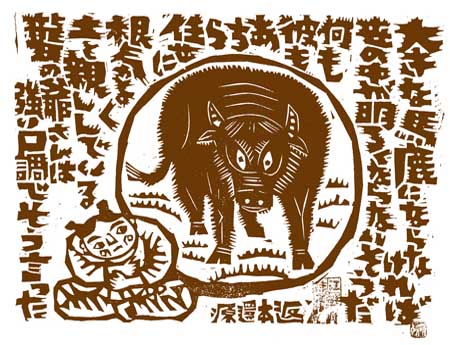

十牛図〈七〉忘牛在人(ぼうぎゅうぞんにん)

VII - BULL FORGOTTEN MAN REMAINS

There are not two Dharmas. Provisionally only has the bull been set up, somewhat

in the nature of a sign-post. He might also be likened to a snare for catching

rabbits, or to a fishing net. Now the herdsman feels as when the shining gold

has been separated out from the ore, or as when the moon appears from behind

a cloud bank. The one cool light has been shining brilliantly since the time

before the beginning.

POEMS

1

The herdsman has come home on the back of the bull.

Now the bull is forgotten and the man is at ease.

He may still sleep though the hot sun stands high in mid-heaven.

Whip and rein are now useless and thrown away under the eaves.

2

Though the herdsman has brought the bull down from the mountain, the stable is

empty.

Straw coat and bamboo hat, too, have become useless.

Not bound by anything, and at leisure, singing and dancing,

Between heaven and earth he has become his own master.

3

Now the herdsman has returned, home is everywhere.

When both things and self are wholly forgotten, peace reigns all day long.

Believe in the peak 'Entrance to the Deep Secret' -

No man can settle on this peak's summit.

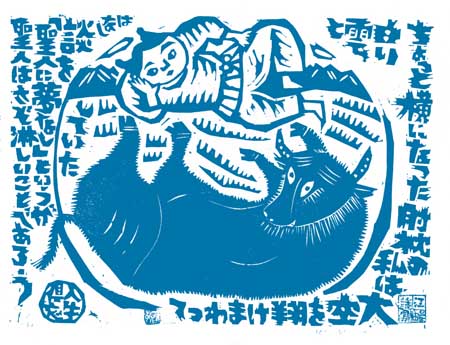

十牛図〈八〉人牛倶忘(にんぎゅうぐぼう)

VIII - BOTH BULL AND MAN FORGOTTEN

When all worldly wanting dropped away, holiness, too, lost its meaning. Do

not stay at a place where Buddha is, and pass quickly by where he is not.

If one remains unattached to either, not even a thousand eyes can spy him

out. Holiness to which birds consecrate flowers is shameful.

POEMS

1

Whip and rein, bull and man, are all gone and vanished.

No words can encompass the blue vault of the sky.

How could snow pile up on a red-hot hearth?

Only when arrived at this place can a man match the old masters.

2

Shame! Up till now I wanted to save the whole world;

Now, surprise! There is no world to be saved!

Strange! Without ancestors or successors,

Who can inherit, who pass on this truth.

3

Space shattered at one blow and holy and worldly both vanished.

In the Untreadable the path has come to an end.

The bright moon over the temple and the sound of wind in the tree,

All rivers, returning their waters, flow back again to the sea.

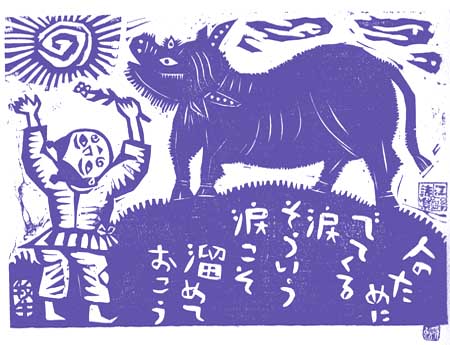

十牛図〈九〉返本還源(へんぽんかんげん)

IX - RETURN TO THE ORIGIN, BACK TO THE SOURCE

In the origin all is pure and there is no dust. Collected in the peace of non-volitional doing (Wu-Wei) he beholds the coming and going of all things. No longer deluded by shifting phantom pictures, he has nothing further to learn. Blue runs the river, green range the mountains; he sits by himself and beholds the change of all things.

POEMS

1

Returned to the origin, back at the source, all is completed.

Nothing is better than suddenly being as blind and deaf.

Inside his hermitage, he does not look out.

Boundless, the river runs as it runs. Red bloom the flowers just as they bloom.

2

The great activity does not pander to being or not being.

And so, to see and to hear he need not be as one deaf and blind.

Last night the golden bird flew down into the sea,

Yet today as of old, the red ring of dawn flares up in the sky.

3

Done is what had to be done, and all ways are completed.

Clearest awakening does not differ from being blind and deaf. T

he way he once came has ended under his straw sandals.

No bird sings. Red flowers bloom in glorious splendour.

十牛図〈十〉入鄽垂手(にってんすいしゅ)

X - ENTERING THE MARKET-PLACE WITH BLISS-BESTOWING HANDS

The brush-wood gate is firmly shut and neither sage nor Buddha can see him.

He has deeply buried his light and permits himself to differ from the well-established

ways of the old masters. Carrying a gourd, he enters the market; twirling

his staff, he returns home. He frequents wine-shops and fish-stalls to make

the drunkards open their eyes and awaken to themselves.

POEMS

1

Bare-chested and bare-footed he enters the market,

Face streaked with dust and head covered with ashes,

But a mighty laugh spreads from cheek to cheek.

Without troubling himself to work miracles, suddenly dead trees break into bloom.

2

In friendly fashion this fellow comes from a foreign race,

With features like those of a horse, or again like a donkey.

But on shaking his iron staff, all of a sudden

All gates and doors spring wide open for him.

3

From out of his sleeve the iron rod flies right into the face.

With a great laugh spread all over his face,

He talks Mongolian, or speaks in Chinese.

Wide open the palace gates to the one who on meeting himself yet remains

unknown.

Cf.

German

version by Tsujimura Koichi and Hartmut Buchner with commentary by Otsu Rekido

Der Ochs und sein Hirte: eine altchinesische Zen-Geschichte, erläutert von Meister Daizohkutsu Rekidoh Ohtsu (大象窟 大津 櫪堂 Daizōkutsu Ōtsu Rekidō, 1897-1976]; übers. von Kôichi Tsujimura (辻村 公一 Tsujimura Kōichi, 1922-2010] und Hartmut Buchner [1927-2004], Pfullingen: Neske, 1958, 132 S.

Verse

and Commentary translated by M. H. Trevor

The Ox and His Herdsman: a

Chinese Zen text with commentary and pointers by master D. R. Otsu and Japanese

illustrations of the fifteenth century. Translated from the Tsujimura-Buchner

version by M. H. Trevor. Hokuseido Press, Tokyo, 1969, 96 pages.

I – The Search for the Ox.

Why the search? The ox has never been missing from the beginning. However, it so happened that the herdsman turned away from himself. Thus his own ox became a stranger to him and eventually lost himself in the far dusty regions. The whole mountains recede further and further, the herdsman finds himself unexpectedly on entangled paths. Desire for profits and fear of loss flare up like a flaming conflagration and views of right and wrong arise in opposition to one another like spears on the battle field.

Poems

1

In an endless wilderness the lonely herdsman strides through thickets of weeds,

searching for his ox.

Wide flows the river, far rise the mountains and ever deeper into entanlement

runs the path.

Utterly exhausted and in despair; even so the searching herdsman finds no

guiding direction.

In the evening twilight he only hears the song of the cicadas in the trees.

2

Facing outwards only

the herdsman searches with all his might.

His feet are already in a deep and muddy swamp but he does not notice.

How often in the sweetly smelling grass under the setting sun

Did he sing Hsin-feng, the song of the herdsman, in vain?

3

In the origin there is no trace. Who could search there?

Confused he gets into a deep place filled with thick fog and tangled briars.

Unbeknown he is already returning home as a guest leading the ox by the nose,

And yet under the tree by the side of the water, his song sounds dispirited.

Cf.

Introduction and verse interpreted by Sonny Saul, Woodstock, Vermont

http://www.highlandengraving.com/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/Ox_Herding_Sample_Book.257144503.pdf

I - LOOKING FOR THE OX

What's the search about?

The ox has never been missing. It's the man. He's been

led astray... and become separated from his own inmost nature. That's what is

lost. The

road and its paths have become obscured. Home seems ever remote. All around,

desires

for gain; fears of loss flare up like a fire. Ideas of right and wrong line up

like opposing

sides in battle.

Alone, alongside a

swelling river, lost in a wilderness of unending mountain paths,

He is searching for an ox.

Exhausted and in despair, as evening darkens, he finds no clue.

He only hears the crickets in the maple woods.

II - SEEING THE TRACES OF THE OX

By reading the SUTRAS and

listening to the teachers he has come to understand

something. He knows now that things, however multitudinous, are of one

substance; that

the world around him and his own nature are reflections of one another. Yet, he

is unable

to distinguish what is genuine from what is fake. His mind is still confused as

to truth and

falsehood. As he has not yet entered the gate, he is provisionally said to have

'noticed the

traces.'

By the water, under the trees, scattered are the traces of the ox.

But there it is-amidst the thick and fragrant woods; the trail.

However remote, over the hills and up to the mountains, the ox may wander,

With its nose reaching up to the sky, it cannot conceal itself any longer.