ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

無外 如大 Mugai Nyodai (1223-1298)

[安達 千代野 Adachi Chiyono; her dharma name: 無著/無着 如大 Mujaku Nyodai]

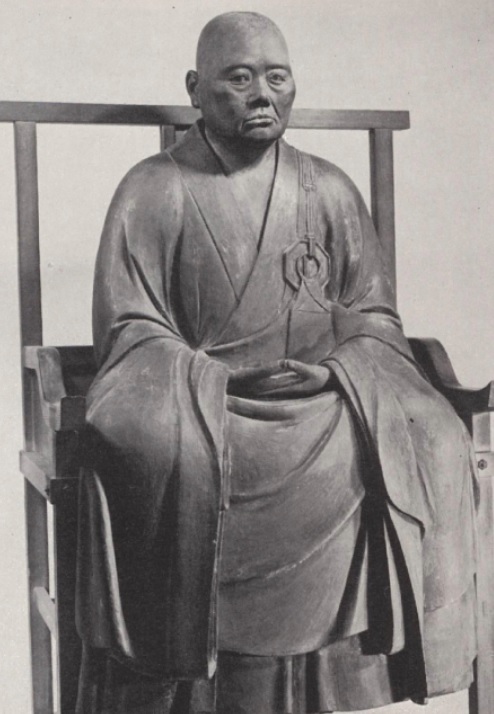

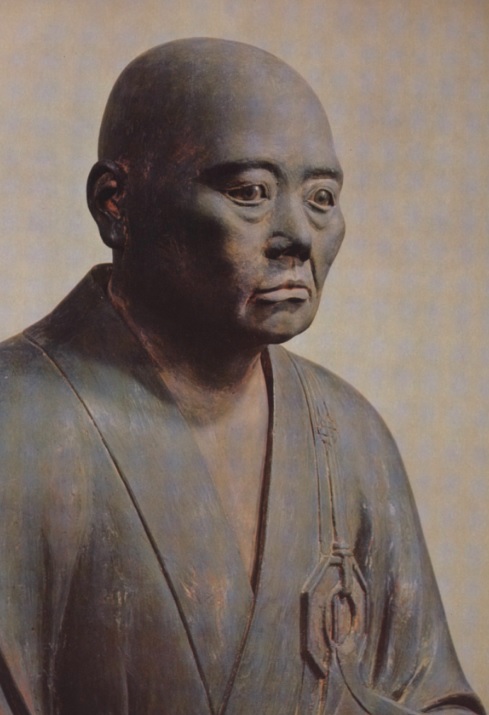

Portrait sculpture of Mugai Nyodai. 真如寺 Shinnyōji, Kyoto

In Memoriam? Rethinking the Portrait Sculptures of Princess-Abbesses Enshrined in the Dharma Hall at Shinnyoji Temple

![]()

無外如大 Mugai Nyodai (1223-1298) was the first Zen abbess and the first female Zen master in the world.

As was customary for all monastic leaders at the time, a portrait statue was made of Nyodai with shaved head and monk's robes. This statue was carved toward the end of her life, around 1298; it is now enshrined in Hojiin convent in Kyoto.

A cursory glimpse may give you the impression that it is a statue of a male; but further perusal reveals a slightly plump, gentle woman with her hands resting in proper Zen contemplative form.

Abbess Mugai Nyodai was a disciple and spiritual heir of the Chinese Rinzai Zen monk Wu-hsüeh Tsu-yüan (known in Japan as Mugaku Sogen [Bukkō Kokushi], 1226–1286); the founding Abbess of Keiaiji Convent, the head temple-complex of the Five Mountain Rinzai Zen Convent Association; and the spiritual matriarch of many of the remaining imperial convents today. The discovery of the magnificent life-size thirteenth-century chinso portrait sculpture of Abbess Mugai Nyodai was one of the initial revelatory events that drew scholarly attention to the wholly ignored female side of Buddhist institutional history and, more broadly, to the role of women in Japanese religious history. In many ways, therefore, she has been the Institute's 'patron saint'.

Dharma Lineage

大鑑慧能 Dajian Huineng (Daikan Enō 638-713)

南嶽懷讓 Nanyue Huairang (Nangaku Ej ō 677-744)

馬祖道一 Mazu Daoyi (Baso Dōitsu 709-788)

百丈懷海 Baizhang Huaihai (Hyakujō Ekai 750-814)

黃蘗希運 Huangbo Xiyun (Ōbaku Kiun ?-850)

臨濟義玄 Linji Yixuan (Rinzai Gigen ?-866)

興化存獎 Xinghua Cunjiang (Kōke Zonshō 830-888)

南院慧顒 Nanyuan Huiyong (Nan'in Egyō ?-952)

風穴延沼 Fengxue Yanzhao (Fuketsu Enshō 896-973)

首山省念 Shoushan Shengnian (Shuzan Shōnen 926-993)

汾陽善昭 Fenyang Shanzhao (Fun'yo Zenshō 947-1024)

石霜 / 慈明 楚圓 Shishuang/Ciming Chuyuan (Sekisō/Jimei Soen 986-1039)

楊岐方會 Yangqi Fanghui (Yōgi Hōe 992-1049)

白雲守端 Baiyun Shouduan (Hakuun Shutan 1025-1072)

五祖法演 Wuzu Fayan (Goso Hōen 1024-1104)

圜悟克勤 Yuanwu Keqin (Engo Kokugon 1063-1135)

虎丘紹隆 Huqiu Shaolong (Kukyū Jōryū 1077-1136)

應庵曇華 Yingan Tanhua (Ōan Donge 1103-1163)

密庵咸傑 Mian Xianjie (Mittan Kanketsu 1118-1186)

破庵祖先 Poan Zuxian (Hoan Sosen) 1136–1211)

無準師範 Wuzhun Shifan (Bujun Shipan 1177–1249)

無學祖元 Wuxue Zuyuan (Mugaku Sogen, 1226–1286), aka 佛光國師 Foguang Guoshi (Bukkō Kokushi)

無著/無着 如大 Mujaku Nyodai (1223-1298), aka 無外如大 Mugai Nyodai; 安達 千代野 Adachi Chiyono

PDF: Commemorating Life and Death: The Memorial Culture Surrounding the Rinzai Zen Nun Mugai Nyodai

by Patricia Fister

In: Women, Rites, and Ritual Objects in Premodern Japan, edited by Karen M. Gerhart, 2018, pp. 269–303.

Hakuin himself was inspired to do at least one painting of Nyodai, throwing

up her hands in surprise as the round bottom drops out of her bucket.

PDF: Of Surplices and Certificates: Tracing Mugai Nyodai’s Kesa

by Monica Bethe

In: Women, Rites, and Ritual Objects in Premodern Japan, edited by Karen M. Gerhart, 2018, pp. 304–339.

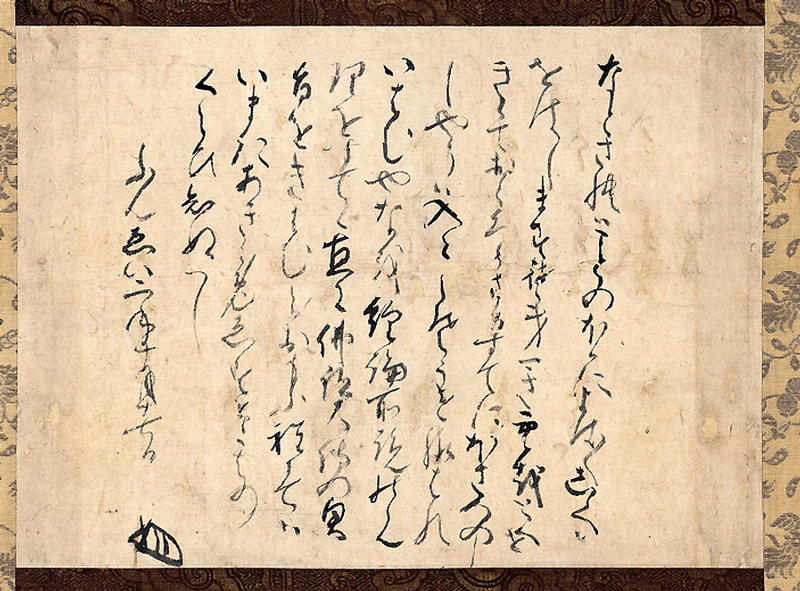

Calligraphy by Mugai Nyodai

Dated October 17th, 1265

Hanging scroll, ink on paper

Height, 26.8cm; width, 39.0cm

Miho Museum

Chiyono was the secular name of the nun Nyodai. Her father was Adachi Kagemori

(1231-1285),

a warrior of the mid-Kamakura period, a maternal relative of the Hojo regent. Chiyono went as a bride to the Kanazawa family, one of the retainers of the Hojo, but after the early death of her husband, she entered the Buddhist life. This kana text can also be called a written Buddhist discussion, and her kao (written seal) appears to be an enlarged joining of the 2 characters of her name, nyo and dai. She is said to have studied with the Chinese priest Mugaku Sogen (C: Wuxue Zuyuan, Bukko Kokushi, founder of Kamakura's Engakuji) and formally entered the Buddhist life under that teacher, but she is also known to have donated and founded a Buddhist convent (later the Rinzai sect temple Keiaiji) in Itsutsuji Omiya. In 1279 (Koan 2), she inherited the teachings of Bukko from China and arranged her temple with the cooperation of Koho Ken'nichi and others. She built Shomyakuin as the funerary monument to Bukko who died in 1286, and Keiaiji became the focal point in Kyoto for the Bukko school. In 1298 (Einin 6), Nyodai died on the 8th day of the 11th month at the age of 76. She is buried at Shomyakuin. Nyodai is known to have been active in the education of the children of Kamakura period samurai families. The Chiyono no fumi text in the Unshu meibutsucho formerly in the collections of the Fuyuki family of Fukagawa, Edo, was purchased in the Tenmei era (1781-89) by Matsudaira Fumai, and he made notations on the text. Among calligraphy works by women, Nyodai's calligraphy was prized second only to Taira-no-Masako, a matriarch of the Kamakura shogunate.

In the thirteenth century an extraordinarily realistic portrait statue (頂相 彫刻 chinsō chōkoku) was carved depicting Abbess Mugai Nyodai in her seventies. Chinsō statues are a category of remarkably realistic life-sized statues of the seated figures of historical Zen masters made as substitutes for the living person to convey the essence of the Zen master to his disciples after his death (1298). This statue, the only thirteenth-century portrait statue of a female Zen master extant, has been declared an "Important Cultural Treasure" by the Japanese government. The original

statue enshrined in

宝慈院

Hōji-in convent in Kyoto, but for protection, an exact replica was made and is kept by the Kanagawa Prefectural Kanazawa Bunko Museum.

Mugai Nyodai, First Woman to Head a Zen Order

Some details of her life are not certain, but it is generally believed that she was given the childhood name Chiyono, and her father was Adachi Yasumori (1231–1285), a samurai warrior of the mid-Kamakura period. She married and had a child (a daughter) at a young age, as was expected for warrior-class Japanese women at the time; she certainly married into the Kanezawa Hojo family, which then governed Echigo, but there is some dispute as to whether her husband was Hojo Sanetoki or Hojo Akitoki. She was highly educated in both Japanese and Chinese.

At some point, she began to visit the monastery of the Chinese Rinzai Zen monk Wu-hsueh Tsu-yuan.Although laywomen were not commonly admitted to monasteries at the time, dharma custom assured that any woman who sought Buddhist teachings would receive them. Once Mugai's husband died and her daughter was grown, she became determined to live out the rest of her life as a nun. She shaved her head, gave up all her belongings, and showed up at the doorstep of Wu-hsueh Tsu-yun's monastery, taking the name Mugai Nyodai as part of her monastic vows.

According to legend, she meditated and practiced for many years without attaining enlightenment, and became very discouraged in her practice. Then one day she was carrying a bucket of water from a river back to the monastery, in an old bucket she had worked hard to repair. She was gazing at the reflection of the moon in the water of the bucket, when the bottom suddenly fell out, spilling water everywhere, and dissolving the moon's reflection. In that moment, she realized that all of her ideas about herself and reality were nothing but false reflections like that moon, being held together like a bucket by her own delusions. She released her delusions and was awakened.

A poem she wrote about her experience has become one of the better known writings of its type. Here is a translation of her poem from the classic Zen Flesh, Zen Bones by Paul Reps and Nyogen Senzaki:In this way and that I tried to save the old pail

Since the bamboo strip was weakening and about to break

Until at last the bottom fell out.

No more water in the pail!

No more moon in the water!When Wu-hsueh Tsu-yun died, he named Mugai his successor, but this met with some resistance by the monks. Wu-hsueh Tsu-yuan's own records (Bukko Kokushi goroku, and Ju Kenchoji goroku) clearly mention Mugai Nyodai as both his disciple and spiritual heir. Over time, she prevailed and founded the Keiaiji Convent, head temple complex of the Five Mountain Rinzai Zen Convent Association.

CHIYONO [MUGAI NYODAI]

Richard Bryan McDaniel: Zen Masters of Japan. The Second Step East. Rutland, Vermont: Tuttle Publishing, 2013.

One of Bukko’s students was the first Japanese woman to receive a certificate of inka. Her Buddhist name was Mugai Nyodai, but she is remembered by her personal name, Chiyono. She was a member of the Hojo family by marriage and a well-educated woman who long had an interest in the Dharma. After her husband died and her family responsibilities had been fulfilled, she went to study with the Chinese master. After completing her studies with Bukko, she became the founding abbess of the most important Zen temple for women in Kyoto, Keiaiji.

A teaching story with no apparent basis in fact suggests that before coming to study with Bukko, Chiyono had been a servant at a small temple where three nuns practiced Buddhism and hosted evening meditation sessions for the laity. According to this story, Chiyono observed the people practicing zazen and tried to imitate their sitting in her quarters, but without any formal instruction all she acquired for her efforts were sore knees. Finally she approached the youngest of the nuns and asked how to do zazen. The nun replied that her duty was to carry out her responsibilities to the best of her abilities. “That,” she said, “is your zazen.”

Chiyono felt she was being told not to concern herself with things that were beyond her station. She continued to fulfill her daily tasks, which largely consisted of fetching firewood and hauling buckets of water. She noticed, however, that people of all classes joined the nuns during the meditation sessions; therefore, there was no reason why she, too, could not practice. This time she questioned the oldest of the nuns. This woman provided Chiyono with basic instruction, explained how to sit, place her hands, fix her eyes, and regulate her breathing.

“Then, drop body and mind,” she told Chiyono. “Looking from within, inquire ‘Where is mind?’ Observing from without, ask ‘Where is mind to be found?’ Only this. As other thoughts arise, let them pass without following them and return to searching for mind.”

Chiyono thanked the nun for her assistance, then lamented that her responsibilities were such that she had little time for formal meditation.

“All you do can be your zazen,” the nun said, echoing what the younger nun had said earlier. “In whatever activity you find yourself, continue to inquire, ‘What is mind? Where do thoughts come from?’ When you hear someone speak, don’t focus on the words but ask, instead, ‘Who is hearing?’ When you see something, don’t focus on it, but ask yourself, ‘What is that sees?’”

Chiyono committed herself to this practice day after day. Then, one evening, she was fetching water in an old pail. The bucket, held together with bamboo which had weakened over time, split as she was carrying it and the water spilled out. At that moment, Chiyono became aware.

Although the story about her time as a servant is certainly apocryphal, the part about the broken pail precipitating her enlightenment seems to be based on her actual experience. She commemorated the event with these lines:

In this way and that I tried to save the old pail

Since the bamboo strip was weakening and about to break

Until at last the bottom fell out.

No more water in the pail!

No more moon in the water!**Paul Reps, Zen Flesh, Zen Bones (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, no date), p. 31.

The Enlightenment of Chiyono

Translated by Anne Dutton

Excerpted from Zen Sourcebook Traditional Documents from China, Korea, and Japan

Edited by Stephen Addiss, 2008, pp. 175-179.

In the village of Hiromi in the Mugi district there were three nuns who built a Zen temple and devoted themselves to practicing the Buddhist way. Together with other nuns who came from all parts, and, on some occasions, with numerous lay disciples, they assembled for communal Zen meditation and practice.

At that time there was a servant woman about twenty-four or twenty-five years of age who had been employed at the convent for many years. Her name was Chiyono. She was said to be the daughter of a high-ranking family. When the aspiration to attain enlightenment developed in her, straightaway she left her parent's home and came to this convent, taking a position as a servant, cutting firewood and carrying water.

Chiyono observed the monastic women practicing Zen meditation. Without noticing it herself, she held their words and teachings in high esteem. She used to peek at the nuns through the gaps in the curtains that hung in the doorway, and then go back to her room and imitate them by sitting facing the wall-but without any benefit.

One day, Chinoyo approached a young nun. “Please tell me the essential principles of practicing zazen,” she pleaded.

The nun answered her by saying, “Your practice is simply to serve the nuns of this temple as well as possible, without giving any thought to physical hardship or uttering a word of complaint. This is your zazen.”

Chiyono thought to herself, “This is grievous! I make my way in the world as a lowly, menial person, living in pain and suffering. If I continue like this, I will suffer in the next life also. Time will pass, but when will there be a chance for me to attain salvation? What evil past has led to these karmic consequences?” Her grieving was endless.

On evening, concealed by the waning moon, she ventured near the meditation hall and looked inside. There she observed aspirants for enlightenment sitting in meditation with the nuns-laymen as well as laywomen, both old and young. Casting away utterly the concerns of the work, they were immersed in their practice of zazen. It was truly an impressive sight.

“Even girls too young to know the difference between right and wrong are in there practicing the difficult exercises of the monastic renunciant. Their desire to slip the confines of this world of delusion is very great. Admonishing themselves to try harder, they sit all night in single-minded silence without falling asleep. How can I who lack such impressive qualities ever be like them?

“These are all laypeople who amuse themselves by night and day and have no understanding of things-and yet they sit there on the mats, throwing away any thought of the world, never laying their heads down on a pillow. Their bodies are emaciated, their spirits are exhausted and yet they pay no attention to whether their lives are endangered. They possess a truly profound aspiration. How aptly they are called ‘disciples of the Buddha'” thought Chiyono to herself as she wept.

Now, one of the nuns at the convent was an elderly woman who was deeply compassionate by nature. One day Chiyono approached her and said, “I have a desire to practice zazen but I am of humble birth. I cannot read or write. I am not very smart. If I set an intention, is it possible I too might attain the way of the Buddha even though I have no skills?”

The elderly nun answered her, saying, “This is wonderful, my dear! In fact, what is there to attain? In Buddhism there is no distinction between a man and a woman, between a layperson and a renunciant. Also there is no separation between noble and humble, between old and young. There is only this—each person must hold fast to his or her aspiration and proceed along the way of the Bodhisattva. There is no higher way that this.

“You must not theorize about the words or teachings of the Buddhas and masters. According to the scriptures the goal is to attain Buddhahood yourself. These teachings say that zazen means ‘to seek the Buddha in your own heart.' According to the ancient worthies, the teachings of the sutras are a like a finger pointing to the moon. The words of the patriarch are like a key that opens a gate. If one looks directly at the moon, there is no need for a finger. If the gate has been opened, there is no use for a key. A priest who is familiar with ten million scriptures uses not a single character word in zazen. Great learning and vast knowledge are only impediments to entering the gate of the dharma. They lead to philosophizing and words. If you know your own mind, what teachings about scripture do you need? In entering the Way we must rely on our bodies alone.

“Furthermore, those who would practice zazen should cultivate a heart of great compassion with the intention of saving all sentient beings. Do not seek enlightenment for yourself alone. Go to a quiet place, sit in lotus posture, and place one hand on top of the other. Without leaning to either side, bring your ears into alignment with your shoulders. Open your eyes only halfway and fix your attention on the tip of your nose. Rest your tongue on the roof of your mouth. Throw away your body and your life. Looking from the inside, your self has no mind. Forget also about your connections with others. Looking from the outside, there is no mind anywhere to be found. If random thoughts should occur to you unexpectedly, let them go straight away. Do not follow them. This is the essential technique of zazen. Believe this and stick to it, waiting faithfully.” The kindly nun explained all this in great detail.

Chiyono received these teachings with faith and made a prostration in front of the nun to express her happiness. “When I first began to practice zazen, the various things I had seen and heard in the past kept coming up in my mind. When I tried to stop them, they only increased. This teaching that I have just heard shows me that when random thoughts occur in my mind, I should let them exhaust themselves. I should not make an effort to try to stop my thoughts.”

“Yes,” the nun responded. “Otherwise it would be like using blood to wash out blood stains. According to an ancient teacher, ‘Sudden enlightenment is the medicine that cures our endless sickness.'”

Chiyono spoke, “If I carry on with this practice, commendable results will surely appear of their own accord. Surely, I will see Buddha nature clearly and truly achieve Buddhahood in an instant.”

The nun intoned in a strong voice, “You have just now understood that all sentient beings have already attained Buddhahood. The world of life and death and the world of nirvana are like a dream.Chiyono said, “I have heard that the Buddha emits rays of light from a tuft of white hair between his eyebrows, illuminating all ten directions. Gazing at them is like looking at the palm of your hand. Can I point to my lowly self and say that I have Buddha nature or am I deluding myself?

The nun replied, “Listen carefully. The teachers of the past have said that people are complete as they are. Each one is perfected; not even the width of one eyebrow hair separates them from this perfection. All sentient beings fully possess the wisdom and virtues of the Buddha. But because they are overcome by delusive thoughts and attachments, they cannot manifest this.”

Chiyono asked, “What are these delusive thoughts?”

The nun replied, “The fact that you adhere to the thoughts that you produce conceals your essential Buddha nature. This is why we speak of ‘delusive thoughts.' It's like taking gold and making a helmet or a pair of shoes out of it, calling what you use to cover your head a ‘helmet' and what you put on your feet ‘shoes.' Even though you use different names for the products, gold is still gold. What you put on your head is not exalted. The things you put on your feet are not lowly. If you apply this metaphor to Buddhism, the gold symbolizes Buddha—that is, realizing your essential nature. Those who are misguided about their essential nature are what we call sentient beings. If we say someone is a Buddha, their essential nature does not increase. If we call someone a sentient being, their essential nature does not diminish. Buddha or sentient beings—people take the point of view that these are two different things because of delusive thoughts. If you don't fall into delusive patterns of thinking, there is no Buddha and also no sentient being. There is only one essential nature, just as there is only one complete world although we refer to the world of the ten directions.

“The Buddha once said, ‘When you get away from all conditions, then you will see the Buddha.' He also said, ‘You must throw away the dharma.' What is this so called dharma? If you really want to know your true nature you must orient yourself towards the source of delusive thoughts and get to the bottom of it. When you hear a voice, do not focus on the thing that you are hearing, but, instead, return to the source of your own hearing. If you practice in this way with all things you will definitely clarify your true nature.”

Chiyono then asked, “What is the mind that fathoms the source of things?”

The nun answered, “The question you have just now asked me—this is an instance of your thinking. Turn to the stage where that thought has not yet arisen. Encourage yourself fiercely. Not mixing in even a trace of thought—this is what we call fathoming the source.”

Chiyono then said, “Does that mean that no matter what we do, as we go about our daily life, we should not observe things but rather turn towards the source of our perceptions and unceasingly try to fathom it?”

The nun said, “Yes, this is called zazen.”

Chiyono said, “What I have heard brings me great happiness. It is not possible for me to practice seated meditation night and day since I am always fetching logs and carrying water, and my duties are many. But if it is as I have heard, there is nothing that is impossible to accomplish in those twelve hours. Encountering the source of my perceptions both to my right and to my left, according to the time and according to the circumstances, how could I neglect my duties? With this practice as my companion, I have only to go about my daily life. If I wake up practicing and go to bed practicing, what hindrance can there be?” With this she joyfully departed.

The nun called out here name as she walked away. Chiyono answered and turned around. The nun said, “Your aspiration to practice is clearly very deep and unchanging.”

Chiyono replied, “When it comes to practice, I've never been concerned about destroying my body or losing my life. I've never even questioned it. If it is as you say, I must not diverge from practicing the totality of the Buddhist teaching even for a little while. All actions are a form of practice. Why be negligent?”

The nun said, “Just now when I called out ‘Chiyono,' why did you adhere to the sound of my voice? You should have just listened to it and returned directly to the source of perception. Never forget: Birth and death are the great matter. All things pass swiftly away. Do not wait—with each in-breath, with each out-breath, rely on your practice at all times. When something is in your way, you must not grieve or linger over it, even though you may have regrets later. Hold on to this firmly.”

After receiving this lesson, Chiyono sighed and fell silent. She had not gone very far before the nun again called out here name. Chiyono turned her head slightly but did not allow her ears to become attached to the nun's voice, returning directly to the source of her perception. In this manner she continued her practice, day after day, month after month. Some days she returned home and forgot to eat. Sometimes she went to fetch water and forgot to transfer it to a bucket. Sometimes she went to collect firewood and forgot that she was in a steep valley. Sometimes she went all day without eating or speaking or went all night without lying down. Although she had eyes, she didn't see and although she had ears, she didn't hear. Her movements were like a wooden person. The assembly of nuns at the temple began to talk about her, saying that realization was near at hand.

The elderly nun heard the talk and secretly went and stood outside her bedroom. Behind a bamboo screen with her hair piled high on her head, Chiyono sat facing the wall. She looked accustomed to sitting, like a mature practitioner. She sat having called up the world of great truth in which all delusions have been abandoned. Turning her consciousness around and looking back on herself, she practiced the most important thing according to the conditions of the moment, guarding her practice without ceasing. Her body was that of a woman who truly displayed the grit of an adept. Even in ancient times such a person was rare. Those who lack such urgency of purpose are shameful.

The nun then asked her, “What place is it that you face?” Chiyono looked back at her then turned back around and sat facing the wall like a tree. The nun then asked her again, “What?! What?!” This time she did not turn her head. Like that, she lost herself in zazen.

In the eighth lunar month of the following year, on the evening of the fifteenth, the full moon was shining. Taking advantage of the cloudless night sky, she went to draw some water from the well. As she did, the bottom of her bucket suddenly gave way and the reflection of the moon vanished with the water. When she saw this she instantly attained great perfection. Carrying the bucket, she returned to the temple.

Previously, she had called the elderly nun who had been her guide and said, “My sickness is incurable and I will die during the night. I want to shave my head and die that way. Will you permit this?” The nun shaved her head.

Furthermore, the elderly nun had heard Wu-hsueh say, “Chiyono may have lowly status but her character is not that of an ordinary woman. Her aspiration is deep—it far exceeds that of others.” She decided Wu-hsueh was right.

What she went to look for herself, Chiyono made a standing bow and said, “You have taught me with great kindness and compassion. As a result, during the third watch of the night, the one moon of self has illuminated the thousand gates of the dharma.” When she finished speaking, she made three prostrations in front of her teacher and then stood as befitting her place.

The nun said, “You have attained the great death, the one, in fact, that enlivens us. From now on, you will study with Wu-hsueh—you must go and see him.”

After this Chiyono was known as Abbess Nyodai. When people came to her with their questions, she would invariably answer, “The Buddha whose face is the moon.” She met with Wu-hsueh and received transmission, becoming his dharma successor. Her dharma name was 無著/無着 如大 Mujaku Nyodai. She was the financial patron of the temple of Rokuon-ji in the Kitayama district of Kyoto in th province of Yamashiro, now called Kinkakujoi.

Chiyono's enlightenment poem:With this and that I contrived

And then the bottom fell out of the bucket.

Where water does not collect,

The moon does not dwell.

PDF: Zen Master Abbess Mugai

From: Japanese Buddhism and Women: The Lotus, Amida, and Awakening by Michiko Yusa (extracts, pp. 115-120.)

In: Dao Companions to Chinese Philosophy, Volume 8. 2019, Pages 83-133.

Female Zen Practitioners Confounded with Mugai Nyodai

by Michiko Yusa [遊佐道子, 1951-]Nyodai died in 1296, as mentioned above. Given the dates of Master Daitō (1282–

1337), the following episode associated with her cannot have been about her. It is a

risqué exchange of what is supposed to have taken place between a nun called

Mujaku 無着66 (who was confounded with Mugai) and the National Teacher Daitō

大燈国師 (SHŪHŌ Myōchō 宗峰妙超). One day Master Daitō passed by her over

the Gojō Bridge in Kyoto and recognized the nun. Thereupon he called out to her:

“Hey, I wonder why you are wearing a robe, when your name is ‘mujaku’ [meaning

“not-wearing clothes”].” Upon hearing these words, the nun undid the sash and

began to undress (Nishiyama 2009: 61*).67 This story has one point to ponder,

namely, Nyodai may have also been called “Mujaku” at some point.

Also, a popular waka is associated with Nyodai, although it was composed by

another woman whose name was Chiyono—a Chiyono of Mino province, who

practiced Zen. The poem reads:No matter how you look at it,

when the bottom of the bucket falls away,

it will not hold water nor will it keep the reflection of the moon.(tonikaku ni/ takumishi oke no/ soko nukete/

mizu tamaraneba/ tsuki mo yadorazu). (Nishiyama 2009: 56, 61*; adapted)The humor of this poem was so endearing that Master Hakuin 白隠 (1685–1768)

drew a picture of a girl holding a wooden bucket the bottom of which was falling

out, and inscribed this verse in the top left margin (see Nishiyama 2009: 56*).64 He was a ninth-generation descendent of Emperor Uda (see Musō 2010: 3). This may explain his

accepting the imperial princesses among his disciples.65 At the time of this appointment, Mugaku Sogen was designated as the temple’s honorary founder

and Musō was named as its second abbot. In 1342 Musō renamed Shōmyaku’an as Man’nenzan

Shin’nyoji, taking the “temple name” (J. sangō 山号) of “Man’nenzan” in memory of master

Mugaku (see Nishiyama 2009: 60*). “Man’nenzan” 万年山, meaning the “ten thousand years old

mountain,” was taken after the “sangō” of Mugaku’s temple in Kamakura, Man’nenzan Shōzokuin

万年山正続院, which was the name of his master Wuzhun’s “Wannienshan” 万年山 in Jingshan

China.66 YANBE Hiroki hypothesizes that this nun Mujaku was a younger relative of Mugai Nyodai, and

this possibly explains the confusion in the biographical information of these two women (Yanbe, Hiroki 山家浩樹

1998: 1–11: 1993. Mugai nyodai no sōken jiin 「無外如大の創建寺院」 [Mugai

Nyodai and the Construction of Temples]. Miura kobunka『三浦古文化』 [Ancient Culture

of Miura]. 53 (December): 1–14.).67 This seems to be the kind of Zen exchanges D. T. Suzuki referred to as “risqué mondō” (Suzuki

1974: 46: Kongōkyō no Zen 『金剛経の禅』 [Zen of the Diamond Sutra]. Tokyo: Shunjūsha.).SUZUKI Daisetz, too, quoted this waka on a postcard to NISHIDA Kitarō, which

he sent on a sultry August day with the following note: “The poet’s name is Chiyono,

of some province I used to know but now I’ve forgotten. It is a female. If my memory

is correct, she is from the Ashikaga period. I have no reference book at hand to

check the facts” (Suzuki 2003: 631: Shokan 書簡 [Letters]. Suzuki daisetsu zenshū 『鈴木大拙全集』[Collected

Works of Daisetz Suzuki]. Vol. 36. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.). The “Ashikaga” period is another name for

“Muromachi” period (1338–1573). If Suzuki’s source is correct, Chiyono of Mino

Province lived during the Muromachi period—at least a century after Abbess

Nyodai.*Nishiyama, Mika 西山美香. 2009. Keiaiji, Hōji’in Monzeki. In Amamonzeki, A Hidden Heritage:

Treasures of the Japanese Imperial Convents (Exhibition Catalogue), ed. Patricia Fister and

Monica Bethe, 54–61. Chicago: Paragon Book Gallery.

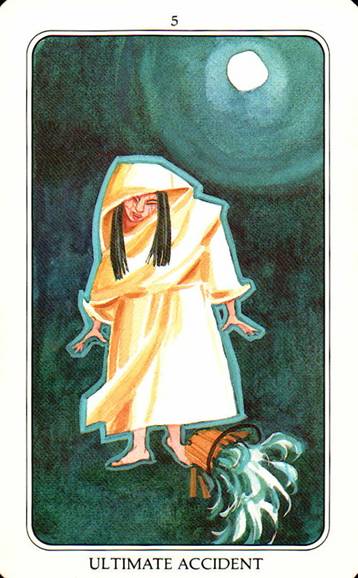

OSHO Transformation Tarot:

60 Illustrated Cards and Book for Insight and Renewal

Pujan (Illustrator)

Using the Osho Transformation Tarot can be a form of

meditation. Whether you are choosing cards for yourself or

conducting a reading for another person, taking a little time for

preparation beforehand is essential. Find a quiet space where

you will not be disturbed. Allow yourself to settle into a relaxed

and open attitude as you shuffle the cards, emptying the mind

of all preconceived ideas you might have about the answer to

your question or concern. Let go of any other preoccupations

that might distract your attention from the reading. Once you

feel settled and relaxed, then spread the deck in a fan and choose

your card or cards.

As you look at the cards you have chosen, remember that

the words are just indicators toward the larger message and

insight contained in the corresponding story or parable. Even

seemingly “negative” words point the way to a hidden potential

for transformation and greater understanding. This will become

clear as you read the stories illustrated by the cards.

Finally, remember Osho's message to remain playful and

lighthearted about all aspects of your search, both inner and

outer. He says, “Take life joyfully, take life easily, take life

relaxedly, don't create unnecessary problems. Ninety-nine

percent of your problems are created by you because you take

life seriously. Seriousness is the root cause of problems. Be

playful… be alive, be abundantly alive. Live each moment as

if this is the last moment. Live it intensely; let your torch burn

from both sides together. Even if it is only for one moment,

that is enough. One moment of intense totality is enough to

give you the taste of eternity.”

5. The Ultimate Accident

Chiyono and her Bucket of Water

It is not a certain sequence of causes that brings enlightenment.

Your search, your intense longing, your readiness to do anything –

altogether perhaps they create a certain aroma around you in which

that great accident becomes possible.

The nun Chiyono studied for years, but was unable to find

enlightenment. One night, she was carrying an old pail filled

with water. As she was walking along, she was watching the

full moon reflected in the pail of water. Suddenly, the bamboo

strips that held the pail together broke, and the pail fell apart.

The water rushed out; the moon's reflection disappeared – and

Chiyono became enlightened. She wrote this verse:This way and that way I tried to keep the pail together,

hoping the weak bamboo would never break.

Suddenly the bottom fell out.

No more water;

no more moon in the water –

emptiness in my hand.Enlightenment is always like an accident because it is

unpredictable – because you cannot manage it, you cannot

cause it to happen. But don't misunderstand me, because when

I say enlightenment is just like an accident, I am not saying

don't do anything for it. The accident happens only to those

who have been doing much for it – but it never happens because

of their doing. The doing is just a cause which creates the

situation in them so they become accident- prone, that's all.

That is the meaning of this beautiful happening.

I must tell you something about Chiyono. She was a very

beautiful woman – when she was young, even the emperor and

the princes were after her. She refused because she wanted to

be a lover only to the divine. She went from one monastery to

another to become a nun; but even great masters refused – there

were so many monks, and she was so beautiful that they would

forget God and everything. So everywhere the door was closed.

So what did Chiyono do? Finding no other way, she burned

her face, scarred her whole face. And then she went to a master;

he couldn't even recognize whether she was a woman or a man.

Then she was accepted as a nun. She studied, meditated for

thirty, forty years continuously. Then suddenly, one night… she

was looking at the moon reflected in the pail. Suddenly the pail

fell down, the water rushed out, and the moon disappeared –

and that became the trigger-point.

There is always a trigger-point from where the old

disappears and the new starts, from where you are reborn. That

became the trigger-point. Suddenly, the water rushed out and

there was no moon. So she must have looked up – and the real

moon was there. Suddenly she became awakened to this fact,

that everything was a reflection, an illusion, because it was

seen through the mind. As the pail broke, the mind inside also

broke. It was ready. All that could be done had been done. All

that could be possible, she had done it. Nothing was left, she

was ready, she had earned it. This ordinary incident became a

trigger-point.

Suddenly the bottom fell out – it was an accident.

No more water; no more moon in the water – emptiness in my hand.

And this is enlightenment: when emptiness is in your hand,

when everything is empty, when there is nobody, not even you.

You have attained to the original face of Zen.

Ukiyo-e: 月岡芳年 Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892)

One Hundred Aspects of the Moon: The bottom of the bucket, which Lady Chiyo filled has fallen out, the moon has no home in the water

(Tsuki hyakushi: Chiyodono ga, itadaku oke no, soko nukete, misu tamari tewa, tsuki mo yadorazu)

signed Yoshitoshi with artist's seal Taiso, engraver's mark Enkatsu, and published by Akiyama Buemon, ca. 1889

oban tate-e 13 7/8 by 9 1/2 in., 35.2 by 24.1 cmThe print and the poem in its cartouche depict the poetess Fukuda Chiyo-ni (1703-1775) who started composing haiku at the young age of fifteen. With guidance from the haiku master Shiko, she gained wide renown as a poet before becoming a nun in her fifties. The image of the spilling water references her most famous poem, composed after asagao (lit. morning face) tendrils grew around her water-bucket.

asagao ni tsurube torarete moraimizu

morning-glories have taken my bucket so I ask for waterHer kimono is richly decorated with chrysanthemums, which in addition to the persimmons and pampas grass growing behind her suggests that the season is autumn.

![]()

Csijono megvilágosodás-verse

Fordította: Terebess Gábor

我曾竭力使水桶保持圆满

期望脆弱的竹子永远不会断裂

然而顷刻之间,桶底塌陷

从此再也没有水

再也没有水中的明月

而我的手中是——空noha javítgattam így is, úgy is

ne essen szét elnyűtt bambuszpántja —

kiszakadt a favödör feneke

elfolyt a víz

vízzel a hold

kezem üres

Százegy zen történet: 29. NINCS VÍZ, NINCS HOLD

Fordította: Szigeti György

In: A zen kapui : Százegy zen történet : Nincs Kapu. Ford., szerk. és vál. Szigeti György, [Budapest] : Farkas Lőrinc Imre Kiadó, 1998, 37. oldal

Csijono szerzetesnő az Engaku kolostorban Bukkónál tanulmányozta a zent. Hosszú ideig

képtelen volt elérni a meditáció gyümölcseit.

Egy holdfényes éjszakán vizet cipelt egy öreg vödörben, amit bambusszal erősítettek meg.

A bambusz eltörött, és a vödör alja a földre zuhant. Csijono abban a pillanatban megszabadult.

Ennek emlékére a következő verset költötte:Próbáltam megmenteni az öreg vödröt.

De a bambusz darabka meggyengült és eltörött.

A vödör alja a földre zuhant.

Nincs többé víz a vödörben!

Nincs többé hold a víz tükrében!